Abstract

It is well established in Australian research and policy literature that children attending schools in regional, rural, and remote locations will benefit from access not only to experiences and interactions offered in their own communities but also to the sorts of experiences available to those in more populated areas of Australia as well. Virtual interactions afforded by technology are an obvious solution to achieving this access by enabling Australian classrooms to be increasingly connected. However, with the plethora on offer and little oversight of their quality, literacy educators are left to sift and sort through volumes of virtual interactions and to make decisions regarding their capacity to promote the development of oral language through play. Using a design-based research approach, this study aimed to identify in research literature key principles for the design of virtual interactions for children that can support the development of oral language through play and test them against those currently on offer. The study confirmed the value of virtual interactions as rich sources for learning that offered shared experiences built on language interactions between creators and users and giving access to new information where learning is scaffolded and understandings can be transferred from virtual to real contexts. The study also identified personal advantages that access to new physical geographies within virtual interactions can offer to those in regional, rural, and remote communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Access and opportunities in regional, rural and remote Australia

Research and policy literature testifies to rural disadvantage as a major concern within the Australian education system (Alloway & Dalley-Trim, 2009; Reid, 2017; Education Council, 2019). Most significant to this paper are the inequities that exist between the kinds of educational experiences available to students in regional, rural, and remote (RRR) locations compared with those in urban and metropolitan areas (Gregory et al., 2015). Despite decades of research and media attention and a national commitment to the promotion of equity and excellence within Australian schooling, RRR students continue to lack access to the educational resources and experiences they deserve (Education Council, 2019). Halsey (2018) argues, “the key challenge for RRR education is ensuring, regardless of location or circumstances, that every young person has access to high quality schooling and opportunities” (p. 13).

The reproduction of unequal academic outcomes is most prominent in national data that demonstrates the persistent relationship between geographic location and educational attainment (Halsey, 2018). The underperformance of RRR students compared to their metropolitan peers has endured consistently for decades because as geographical isolation increases, academic achievement declines (Elston, 2019). Furthermore, Welch (2007) observed that RRR communities are also often more vulnerable to social and economic marginalisation, higher rates of unemployment, poverty, and declining population growth. However, to assume all children living outside metropolitan locales experience life similarly would be erroneous. Such a view would oversimplify the complexity of rurality and fail to recognise the diversity that exists within and between RRR communities (Alloway & Dalley-Trim, 2009). In particular, the diversity of lived experiences and challenges faced must be recognised.

RRR schools and students face a multitude of challenges including low participation and completion rates, schooling quality, demands of travel, financial costs, high teacher turnover, and the inaccessibility of varied curricular offerings and resources (Welch, 2007). Unfortunately, these challenges are often used within education contexts to position RRR communities as deficit, something Comber and Kamler (2004) assert to be a pervasive failure within educational contexts because students in marginalised situations are presented as wanting rather than worthy. Deficit discourses related to place not only demonise “the rural” and construct RRR schools as destitute, deficient, or failing but also position students there as “empty or culturally underdeveloped” and ultimately lacking valuable social, economic, and cultural capital compared to their urban counterparts (Mills & Comber, 2013, p. 415). Educational communities, then, need to dispute “place-as-inequality” to reclaim “place-as-transformation” and value RRR locations as rich and vibrant places of learning (Sutton and Kemp (2011, p. 10). Therefore, this paper acknowledges the complexities of rurality for improving access and connectedness for RRR students. And it looks to advance educational practices for positive impacts on the educational trajectories of students growing up marginalised by location.

2 Technology as a mediator for access and outreach

Historically, correspondence schooling and distance education services including School of the Air have aimed to bridge the geographical divide and address the challenges associated with educating Australia’s “dispersed populations” (Symes, 2012, p. 504). The result is effective teaching and learning through the postal system, rail network, two-way radio broadcast, and telephone communications (Reiach et al., 2012; Stacey, 2005). This evolution and utilisation of technology demonstrates how education can be “transported and transmitted into other spaces… and can have the power to make even the remote the centre of attention” (Symes, 2012, p. 514). In recent times, the exponential growth and pervasiveness of information and communication technologies (ICT) have become a critical enabler in connecting geographically isolated children and educators with otherwise inaccessible learning experiences and resources (Halsey, 2018; Lester, 2012). Indeed, Halsey (2018) found ICT access and infrastructure affords enhanced professional development opportunities, improved experiences for students, and increased capacity to construct and share knowledge “locally, nationally and globally” (p. 70). When utilised by RRR educators, contemporary ICTs can “break open the enclosed classroom” and promote equal opportunity and access for RRR schools (Parsons et al., 2019, p. 144).

It is essential to note that neither this paper nor the promotion of educational technologies for RRR seek to devalue, undermine, or limit the knowledge, perspectives, or lifeworlds of RRR communities. This research centres on the belief that education should take all children beyond their known world and provide broader experiences and opportunities, including those in RRR communities (Downes & Roberts, 2015).

3 Technology can enable and constrain opportunities to build new knowledge

Technology has transformed the way we live, teach, and learn because our relationship with technologies is “always in a state of becoming” (Rowsell, et al., 2016, p. 121). Contemporary pedagogies offer “an imagined and expanding geography” (Leander et al., 2010, p. 330) where new contexts, experiences, and knowledge grow.

Digital experiences can introduce learners to abstract concepts (Lieberman et al., 2009) and the potential to engage with collaborative learning, reasoning, and problem-solving activities. Digital technologies enable experiences that are “real” enough to be pedagogically important (Fenwick et al., 2011, p. 139), prompting new understandings about how our lives are intertwined with technology (Fenwick et al., 2011; Parsons, et al., 2019). Indeed, technology has the potential to create “new networks, new configurations and new possibilities for learning about the world through the digital and virtual worlds we enter into” (Parsons, et al., 2019, p. 155).

While there are considerable advantages of using technology to transform knowledge as new contexts are made available, there are constraints too. The design of the digital experience can enable or constrain the experience as navigation pathways, opportunities to contribute, and the content itself are defined (Edwards, 2013). The design features of a digital experience contribute to the ways new knowledge can be developed and the forms it may take. Furthermore, digital experiences are impacted by access to appropriate technology infrastructure and support that in turn determines the success of that experience. For example, insufficient bandwidth or WiFi speed will impact the ability to live-stream video content that may be critical to the digital experience, a situation that compounds issues related to equity for learners (Edwards, 2013).

In terms of play, technology enables play experiences that children have never seen before and that are quite different from traditional forms of imaginative play (Kervin, 2016; Verenikina et al., 2016). While traditional forms are associated with self-regulation and high levels of control, play within the context of digital technology is often shaped by the affordances of the technology itself (Verenikina, et al., 2016). Digital play is variously defined as a “mode of meaning making activity for young children responding to life” (Edwards, 2019, p. 56), activities undertaken with technology (Marsh, 2010), and using digital technologies in play-based forms (Verenikina & Kervin, 2011). Since play is key to developing language, communication, collaboration, problem solving, and social interactions (Danby et al., 2018; Marsh & Hallet, 2008; Siraj-Blatchford, 2009), it is important to understand the nature and affordances of digital play. Kervin (2016) argues that technology has the capacity to develop and extend literacy proficiencies; however, the nature of the experience is critical. Just like learning with non-digital resources, passive use of technology constrains the freedom of the learner and jeopardises their literacy development, particularly for independent critical and creative thinking (Danby, et al., 2018; Fleer, 2014). Meaningful digital experiences for children should 1) encourage self-motivation and be intrinsically fun, 2) provide opportunities for acting in “as if” situations where there is no right or wrong answer, and 3) offer discovery-oriented paths of play with opportunities for making choices, problem solving, and visual transformation of images (Verenikina et al., 2016). While these criteria were developed for software and tablet apps, they are also applicable to digital experiences and virtual interactions.

4 A focus on virtual interactions

As a growing presence in the lives and education of children, virtual interactions are worthy of greater academic attention particularly as a potential mediator for RRR access and outreach. This paper adopts the term virtual interaction (VI) for digital outreach that aims to transport learners to new places and spaces through connections made in the digital environment. Examples of VIs include a virtual excursion to the National Science and Technology Centre or a virtual play date at a children’s museum. Ultimately, a virtual interaction is defined by synchronous or asynchronous interactions where participants have an immersive, explorative, and educative experience and the learning is situated in an environment and context otherwise unavailable or inaccessible. This paper explores the characteristics of the design of VIs in the ways they may support the development of oral language through play. These characteristics in this paper are described as design principles.

VIs offer a range of affordances, including the provision of a “cognitive, affective, physical, social and aesthetic curriculum experience” (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, 2016, p. 1). Most important to this study is their ability to transport learning beyond the classroom through rich educational experiences accessible to “diverse, underserved, and global audiences” (Mitchell, 2019, p. 226). Part of the richness of VIs is a sense of vitality in the learning, a sense of energy and liveliness (Boldt, 2020) achieved through affect, movement, playfulness, spontaneity, communication, and difference. For RRR settings, the novelty and vibrancy of VIs may promote feelings of energy, “buzz” and “aliveness” (Boldt, 2020, p. 5). The focus of this study, then, is to better understand the design principles of VIs in connection with opportunities for learning with a view to supporting RRR educators in their selection and utilisation of these digital experiences.

5 Methodology

This qualitative study explored how virtual interactions (VIs) may support educators and children to build new knowledge through access to new contexts (places and spaces). The participants in this study are three digital resources (virtual interactions) offering virtual access to three physical locations that geographical barriers would otherwise prevent RRR educators and their learners from attending. As publicly available non-human resources, there was no requirement for human ethics approval for the research to proceed. The design, content, and presentation of each VI formed rich data sets for analysis using iterative cycles that tested a set of principles identified from a review of relevant literature. The parameters of this research have focused on three publicly available virtual interactions, affording a depth of analysis into their design and potentialities for learning. While only three instances of VIs were examined, it should be noted that they were selected to showcase the diversity of available digital experiences. The findings presented in this paper offer pedagogic design principles for developing new knowledge through virtual interactions. There is no suggestion in the findings that VIs will resolve the educational inequities experienced by children in RRR areas. However, the findings offer a concerted effort to inquire into educational technologies that speak back to deficit.

The following research questions guide this paper:

-

How do virtual interactions incorporate play and oral language within the experience?

-

What are key design principles for virtual interactions that build oracy and play?

6 Design-based research

As a research approach, design-based research (DBR) addresses significant educational problems through innovative solutions (Kervin et al., 2006). Ultimately, the goal of DBR is to create stronger connections between educational research and real-world issues in practice (Amiel & Reeves, 2008). A typical educational application of DBR is the design, development, evaluation, and redesign of teaching and learning programs, materials, and products. In particular, DBR provides a meaningful lens through which to examine inherent complexities of researching educational technologies (Amiel & Reeves, 2008). Reeves (2006) promotes developmental research that looks to “improve, not to prove” (p. 18) the nature of individuals’ lives, which makes DBR an appropriate and powerful way to examine the place of VIs in RRR communities.

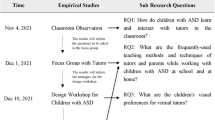

DBR comprises four phases (see Fig. 1). In phase 1, a challenge or “problem” is identified. In phase 2, a “solution” is identified and prepared for iterative testing cycles through data collection (phase 3) and analysis (phase 4). The nature of DBR is such that a researcher can revisit different phases in interactive cycles to test the phenomenon in question and to develop principles that look to resolve the problem.

Phases of design-based research (Reeves, 2006, p. 59)

The aim of DBR is twofold — to refine theory and practice (Collins et al., 2004). In this study, the phases of DBR (Reeves, 2006) afforded an examination of virtual interactions across the four core phases with the view to understanding how their design can support the development of oral language through play. Identified in phase 1 was a lack of clarity in research literature about the nature of virtual interactions as pedagogic resources. Themes identified in the literature became existing principles for developing new knowledge through virtual interactions in phase 2, which were then tested in phase 3 through data collected across three iterations using three examples of VIs. Finally, the phase 4 analysis led to the identification of a final set of design principles for developing new knowledge through virtual interactions as presented in this paper.

6.1 Phase 1: review of literature

While ever changing advances to technology have potentially improved RRR learners’ access to VIs, what remains unclear is the nature of these experiences and the quality of the learning on offer. The problem is particularly acute in the context of the recent global pandemic that sparked increased need for virtual learning. What do these virtual experiences offer? How do they enable or constrain the development of new knowledge? How does their design promote the development of oral language through play? A thematic inductive analysis of findings in the literature review related to VIs was used to identify emerging principles in preparation for the construction of a solution.

6.2 Phase 2: construction of a solution

The design principles identified in the thematic review were defined and then refined to reflect the focus on the development of oral language and play. These design principles were then utilised as a lens for analysing the nature of existing VIs in connection with what they offered for learning in RRR communities. It is these design principles that were tested in phase 3.

6.3 Phase 3: iterative cycles of testing

The emerging principles identified from inductive analysis of the identified literature in phases 1 and 2 were utilised as a deductive analysis frame for three VIs. The principles were tested against selected VIs to determine what is enabled or constrained within the experiences along with their technological affordances. Three iterative cycles afforded testing of different types of VIs. Iteration 1 examined the principles as evidenced in a virtual tour of Reef HQ Aquarium. The researchers engaged with the VI using the principles as the lens for analysis to understand the opportunities on offer. The second iteration similarly examined the principles as evident during a virtual excursion to the University of Wollongong’s Discovery Space. And the third iteration repeated the process by examining the principles in action during a VI to Sydney’s Taronga Zoo where experts shared insights about an endangered species. Observations of on-site recordings and document analysis of lessons plans and websites were used to test the VI principles in practice for each iteration.

6.4 Phase 4: a refined criteria

Analysis of the selected VIs through the lens of the principles afforded their refinement. The result is recommendations for future development of VIs focused on play and oral language for learners and their educators in RRR communities.

7 Analysis

7.1 Identifying existing design principles for virtual interactions in the literature

A thematic literature review revealed important findings related to the pedagogical use of VIs. While the term “virtual interaction” remains largely absent in the literature, it is used in this research as an overarching term that encompasses digital experiences created for learners to be accessed through digital technologies and that purport to offer educative experiences. As such, keywords and phrasings comprised rural and remote education (Alloway & Dalley-Trim, 2009; Reid, 2017), the use of digital technologies to overcome geographic isolation (Adlington, 2014), digital play (Verenikina & Kervin, 2011), iPads, digital play, and pre-schoolers (2011), virtual play (Burke, 2013), educational virtual reality tools (Pilgrim & Pilgrim, 2016), virtual museums (Mitchell, 2019), and learning worlds (Parsons et al., 2019). Given the focus on experiences accessible for all learners and educators in RRR communities, excluded from this review was research reporting digital interactions during physical visits, adult education, and special needs education (e.g. gifted education, special education, EAL/D).

While there were multiple themes evident in the body of research reported in the literature, the following pedagogical and organisational principles were selected for testing in phase 3 because of their relationship with the focus of the research questions on play and oral language.

-

1.

The experience incorporates a rich stimulus

-

2.

Interactions offer opportunities for a shared experience

-

3.

Interactions provide access to new information

-

4.

The experience scaffolds learning

-

5.

The experience promotes transfer of knowledge

These principles emerging from the review of literature are defined and discussed in Table 1.

8 Findings

In phase 3, the principles identified in the thematic literature review were tested through three iterations against three selected virtual interactions. Each VI was examined separately with the principles to identify areas of fit, but also to reveal new possibilities.

-

Iteration 1: virtual tour of Reef HQ Aquarium, National Education Centre for the Great Barrier Reef https://www.reefhq.com.au/education

-

Iteration 2: virtual excursion delivered in real time as part of the University of Wollongong’s Outreach Program https://www.uow.edu.au/the-arts-social-sciences-humanities/

-

Iteration 3: expert insights from Sydney’s Taronga Zoo about an endangered species https://taronga.org.au/education/digital-programs/legacylive

8.1 Iteration 1: virtual tour of Reef HQ Aquarium through Reef Video Conferencing

Reef Videoconferencing is one component of the Virtual Connections Program offered at the Reef HQ Aquarium, the National Education Centre for the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Developed by the Reef Education Team, Reef HQ’s video-based outreach education program extends the aquarium’s capacity to connect with and provide all students, regardless of their geographic location or access to sophisticated technology such as virtual reality goggles, the opportunity to learn in and about the World Heritage Listed Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Through a “reef video conference”, students can participate in a “virtual dive” including a virtual tour of the aquarium’s exhibits that simulate the GBR by watching the screen (as they would in any video conference) and interacting directly with those in the GBR. This experience strives to not only make the reef accessible but also inform children of its value, threats to its sustainability, and their role in protecting it.

The live and interactive video recordings of the GBR are visually stimulating, potentially evoking feelings of excitement and vitality amongst children. The virtual tour offers a novel experience that transports participants to the Reef HQ Aquarium in Townsville, Australia. Students participate in a virtual scuba dive where they adopt the role of an underwater explorer and discover the wonders of the coral reef and predator exhibits. Through access to new contexts, students build new knowledge through an “underwater fact-finding mission”. Specifically, within the coral reef exhibit, live video footage introduces participants to the corals that create the reef, discuss the relationships present between organisms such as clownfish and anemones, and explore the roles giant clams, sea cucumbers, and reef fish play within the ecosystem. Students also encounter top predators including the black tip reef shark, leopard shark, and shovelnose ray. Students investigate threatened species, impacts of humans on the marine environment, and an invitation to protect the GBR. This new information is shared through Polycom video conferencing technology that allows participants to interact with the underwater expert — a trained scuba diver and marine biologist.

The experience is scaffolded to ensure information is not merely presented but co-constructed between facilitators and participants. For example, live discussions and questioning develops domain specific knowledge and technical and academic language modelled by the facilitators within a supportive and contextualised environment. Similarly, the presenter builds field knowledge through shared demonstrations and explicit modelling of technical vocabulary. Students and educators also supplied with supporting materials prior to and upon completing the virtual tour. Lastly, Reef HQ’s Reef Video Conferencing promotes flexibility in transfer of knowledge to other contexts as students are encouraged to move their knowledge and understandings from the virtual to the physical space. Children may relay facts and information gathered from the virtual tour to peers and family members, e.g. the types and roles of predators in the GBR, or they may actively reduce their environmental impact and undertake measures to conserve the GBR within their communities.

Findings from analysis of the GBR VI in connection with the initial design principles are summarised in Table 2.

8.2 Iteration 2: virtual excursion — “Lost and Found”

Virtual excursions (VE) are 15–20 min real-time video connected interactions facilitated by early years educational researchers for children and their educators in early years settings. Serving as an outreach experience from an interactive children’s museum, The Early Start Discovery Space at the University of Wollongong, VEs offer children access to the space, and for educators, pedagogical examples of how play can be used to develop oral language. VEs follow a pedagogic sequence: connection to an experience in the Discovery Space, building field knowledge, reading a story, playfully deconstructing the story, generating new understandings, and finishing with a closing challenge for the children to complete with their educators. The VE analysed here occurs at the ship. The picture book, “Lost and Found” by Oliver Jeffers (2015), orientates the excursion and builds field knowledge, ultimately creating shared understandings amongst participants. The experience then extends on the story through play related to the themes of travel and adventure, as they adopt the roles of explorers aboard a ship en route to Antarctica.

The VE provides opportunities for new geographic and literacy learning (NSW Education Standards Authority, 2012, 2015). In the syllabus, students are required to identify places and their significance to people while responding to and composing simple texts regarding familiar aspects of their world and past experiences. This pedagogic focus is evident within the excursion when students, together with the facilitators, explore facts about parts of the ship, the nature of arctic exploration, and wildlife in and around Antarctica. This knowledge is reinforced through exposure to and development of technical language and vocabulary through play, as the facilitators discuss key terms such as helm, continent, hemisphere, and albatross. Through live video conference, students are invited to participate in and direct the play to generate new understandings.

Similarly, the experience scaffolds learning by connecting with and extending upon participants’ existing knowledge, for example, “Can you call out to us what it’s like in Antarctica?”. The facilitators also effectively build field knowledge to assist students in accessing unfamiliar and abstract concepts. Reading and deconstructing the text “Lost and Found”, utilising songs, discussion prompts, “I wonder” statements and physical objects, including a globe and “Explorer Bear” is essential in creating an engaging and supportive environment as students learn about and within contexts and spaces that may be unfamiliar. The excursion concludes with a game of Who Am I?, bringing knowledge from the excursion to this new context and inviting participants to transfer their understandings into their own settings. The facilitators wondered if the participants might play their own game or discover facts about Antarctica and the creatures that live there. “Lost and Found” provides a pedagogical model of oracy development within early childhood and primary contexts. When the educators use, consolidate, and extend language within the excursion, they promote the transfer and flexibility of knowledge, allowing students to replicate, expand, and modify experiences and language in their own settings and socio-dramatic play scenes, ultimately, developing new understandings between virtual and physical learning worlds.

Findings from analysis of the Lost and Found VI in connection with the initial design principles are summarised in Table 3.

8.3 Iteration 3: expert insights — Taronga’s LegacyLIVE

Established by the Taronga Conservation Society Australia, “Taronga’s LegacyLIVE” is one of many digital initiatives developed by Taronga’s Education Team. The team report their purpose as ensuring “all students can access the wealth of knowledge, expertise and animals found at Taronga” (Taronga Conservation Society Australia (TCSA), 2019, p. 40). In 2016, Taronga identified ten “Legacy Species” and dedicated the next decade to their conservation and protection. Five are native to Australia including the Platypus and the Southern Corroboree Frog. The remaining five are facing extinction in Sumatra such as the Sumatrun Tiger and Rhinoceros. Taronga’s education programs, including LegacyLIVE, aim to connect individuals with threatened wildlife and act as a conservation mechanism, informing and encouraging people to act “for the wild” (TCSA, 2019, p. 20).

Within this experience, children connect with a zookeeper via video conference where they are provided expert insights into one critically endangered species located at Taronga Zoo. The example of a LegacyLIVE interaction analysed for this study focused on the koala species through asynchronous and synchronous learning experiences. The koala VI takes a “flipped classroom” approach where students and educators engage with materials and activities provided by Taronga in preparation for their interaction with a Taronga Koala Expert. These resources contain stimulus videos and images related to the people and content of the upcoming webcast. They include a “meet and greet” video with Keeper Andrew and Baxter the Koala, clips from a Taronga Unit Supervisor from the Australian Fauna Team and the CEO of Taronga, Mr Cameron Kerr, photographs of koalas, and a 360-degree virtual reality image of Baxter to explore. During the VI itself, LegacyLIVE offers a shared experience as children meet and interact with the Taronga Expert in real time. They can direct the question-and-answer session and hear first-hand about koalas and Taronga’s work to conserve the species. The interactions provide access to new information including facts regarding koala habitat, diet, adaptations, physical features, and behaviours along with threats to their survival. Furthermore, students are exposed to domain specific vocabulary as the expert models and uses technical language in context, for example, eucalyptus leaves, koala joey, and marsupials.

The experience places the onus on the teacher to support and scaffold learning prior to the VI through an invitation to explore the stimulus resources and complete one of two LegacyLIVE activities applying working scientific skills within practical, real-world tasks. Here, students adopt the role of a Taronga Zoo Expert to:

-

Design a koala crossing prototype for reducing issues associated with urban development, vehicle strikes, and predation. Learners may construct a product using recycled materials or a digital 3D model using SketchUp or Tinkercad.

-

Devise a koala campaign raising awareness of the threats to koalas and integrate a call to action to prompt individuals to assist in wildlife conservation efforts.

Although these VI experiences generate shared field knowledge amongst participants that will be consolidated and extended upon during the VI, there is no evidence of the experience activating or relating to students’ prior knowledge. However, discussions about the effects of drought and bushfires on koalas and their habitats does connect with students’ lived experience, as these contexts are familiar to students living in RRR communities.

Finally, the expert insights promote transfer of knowledge by empowering children to take action to protect critical habitats and conserve wildlife within their communities. This virtual-physical migration provides a space for the expression of children’s voice and agency.

Findings from analysis of the LegacyLIVE VI in connection with the initial design principles are summarised in Table 4.

9 Discussion and conclusion

In this research, initial design principles identified within relevant literature related to pedagogies for supporting learners in rural and remote communities were analysed through three iterations of testing in connection with publicly available virtual interactions. Findings from this process are expressed as a set of refined design principles for supporting educators and children to build new knowledge through access to new contexts. In what follows, each principle is defined, explicated, and refined in response to the research questions:

-

How do virtual interactions incorporate play and oral language within the experience?

-

What are key design principles for virtual interactions that build oracy through play?

9.1 Principle 1: the experience incorporates a rich stimulus

In this study, each VI incorporated a rich stimulus ranging from live video capture, a children’s picture book, and photographs, all of which assisted participants to develop interest in the experience and evoke opportunities for talk. Evident across the iterations was the different types of participation the stimuli encouraged. However, in-the-moment action in all virtual interactions was confined to watching, speaking, and listening. For example, a call to action utilised during the VE (iteration 2) involved the participants singing “A sailor went to sea”, while participation in the Reef HQ (iteration 1) and Taronga (iteration 3) interactions was limited to opportunities for students to pose questions.

Children’s passivity during VIs restricts their capacity to construct knowledge and think critically and creatively about the information being presented (Danby, et al., 2018; Fleer, 2014). Active participation offers something quite different as children’s “whole bodies—the eyes, the ears, the feet, the hands… as well as an active mind, are involved in making sense of place, and of representing perceptions and knowledge of the world” (Mills et al., 2013, p. 25). As such, the findings point to the need for VIs that move children beyond passive engagement and positioning them as active participants through movement and sensoriality (Mills et al., 2013).

Recommendation: active participation within the design of future VIs may include:

-

Role play: students act out a scuba diver or zookeeper scenario.

-

Imitation: children imitate the modelled content (e.g. swim like a leopard shark, breach like a whale, climb like a koala).

-

Directing the experience: students navigate where they will explore next (e.g. on the ship or within the coral reef exhibit).

-

Provision of sensory materials: children and educators use tactile stimuli to supplement learning. This may be a package sent to the participating school (e.g. objects replicating the textures of coral or a sea cucumber) or as a list of materials for the educator to acquire (e.g. eucalyptus leaves).

These revisions to principle 1 offer guidance for future design of VIs to embrace rather than restrain “energy, movement, affective and embodied connections” (Boldt, 2020, p. 8).

9.2 Principle 2: interactions offer opportunities for a shared experience

Each VI provided an opportunity for participants to interact with new places and spaces, specifically in these examples, Townsville, Wollongong, and Sydney. The reality for children living in RRR communities is that they would have limited opportunities to physically visit these spaces. Thus, the ability to explore novel or inaccessible resources is vital to the quality of VIs. Clearly emerging across all iterations was the importance of connection and interaction and thus demanded a greater focus within the original criteria. Specifically, each VI created a “new social space” for literacy and learning within the classroom, where rich communication and collaboration between facilitators and participants occurred (Mills & Comber, 2013, p. 418). Through virtual means, children could connect and interact with expert community members including marine biologists (iteration 1), university academics (iteration 2), and zookeepers (iteration 3). Live exchanges via videoconference, for example, sharing ideas about what a person would see in the ocean near Antarctica during the virtual excursion demonstrated VIs’ capacity to forge connections and dialogue between urban, rural, and remote locations that are “increasingly dynamic, multimodal, social and technologically mediated” (Thibaut, 2015, p. 85). These interactions are key to the educational value of VIs, evident through the nature of the contexts and content shared in addition to how oral language was used to talk about the experience (evident in vocabulary but also the nature of the questions posed). Furthermore, it is reasonable to surmise that enhanced talk and children’s role as active contributors may then lead to an increased aptitude to transfer knowledge and generate deeper cognitive understandings (Thibaut, 2015).

While question/answer sessions within the VIs generated a shared experience, a more creative approach could be achieved through activities such as storytelling. Bromley (2019) argues that storytelling facilitates oral language and literacy development and allows students to utilise vocabulary that is quite different from conversation. Listening to and sharing stories goes beyond the speaking and listening modes to form connections amongst participants, creates a sense of belonging, and can contribute to students feeling valued within the experience (Agosto, 2016; Bromley, 2019).

Recommendation: enhancing connectedness and interaction within the design of future VIs may include:

-

Allowing students to explore unfamiliar or inaccessible contexts and talk in real time with an expert other.

-

Ensuring connections are forged between classrooms and cultural/educational institutions irrespective of geographic location.

-

Providing opportunities for children to meaningfully use storytelling in powerful ways.

9.3 Principle 3: interactions provide access to new information

The VIs all provided opportunities to explore, extend on, and enrich learning beyond the immediate context. Literacy and content knowledge identified within the iterations included information regarding marine ecosystems located within the GBR, arctic exploration, and koala conservation in addition to domain specific vocabulary related to such topics. In addition to semantics, new information was also attached to oral language development, specifically pragmatics. This was particularly evident during the VE in iteration 2, with its focus on play and oral language, which aimed to develop children’s language for interaction. It seems a strength of VI design is in its offering of access to new information, indeed, the data collected from each iteration affirmed the original criteria and did not prompt any change.

9.4 Principle 4: the experience scaffolds learning

VIs, like other educational experiences, utilise scaffolding strategies that support students to construct new knowledge. Within the interactions, each facilitator built knowledge of the field through guided demonstrations, discussions, and modelling of technical language. In addition, there were instances within the design of the VIs that demonstrated an effort to connect with or construct prior learning amongst participants. For example, in iteration 3, the Taronga Zoo experts discussed environmental dangers common to rural areas and their impact on koala populations. Furthermore, dialogic scaffolding emerged as a key consideration from these iterations as expert-novice interactions served as scaffolds to enhance learning and understanding (Rojas-Drummond et al., 2013). Here, new knowledge and language were built through extended commentary about the topic, supported by images, objects, video clips, diagrams, etc. By harnessing talk as a strategic pedagogical tool, facilitators engaged children and “stimulated and extended their thinking” (Alexander, 2008, p. 37).

Edwards-Groves (2014) argues that the creation of a dialogic learning environment is particularly significant when scaffolding diverse educational contexts because it brings “all students into the learning conversation” (p. 11). In the case of RRR classrooms, dialogic learning is powerful in its capacity to develop pragmatic, flexible, and productive use of language, and as such, needs careful consideration in VI design.

Recommendation: creating dialogic spaces and scaffolding experiences within VIs may include:

-

The incorporation of modelling, guided demonstrations, questions, discussions, and prompts from an expert other within the learning experience to facilitate dialogic inquiry.

-

Various collaboration combinations such as facilitator-group and facilitator-student (Swan et al., 2019).

-

Extended opportunities for peer interaction and talk should be provided as an additional means of supporting learning processes (Rojas-Drummond et al., 2013, p. 13).

9.5 Principle 5: the experience promotes transfer of knowledge

Each VI invited participants to transfer knowledge from the experience to other contexts. In one example, the facilitators of the virtual excursion prompted children to replicate and extend on new language within their own contexts and play scenes, demonstrating the importance of fluidly moving knowledge between virtual and physical learning worlds (Parsons, et al., 2019). While the invitation certainly aligned with the focus on transfer of knowledge, it was isolated from contexts other than the excursion itself.

Findings from data analysis revealed the power of a more contextualised experience where the VI does not stand alone but rather within a collection or sequence of resources and opportunities. A more contextualised approach was observed in Taronga LegacyLIVE, where in class activities were offered prior to the “ask an expert” videoconference in preference for the online engagement. Opportunities to engage with content prior to an experience are significant as it builds knowledge and forms a stronger link between the learning that occurs physically within the classroom and virtually within the interaction.

The duality of VIs is that they transfer information and content while simultaneously presenting a novel experience that engages children in “thought, emotion and dialogue” (Ryan & Dagostino, 2017, p. 53). Thus, when designing VIs, creators must encourage students to discuss the information and ideas presented within the VI but also the personal responses the experience evokes. Only when provided opportunities to meaningfully explore the experience can students build oral language and develop their voice in the classroom and beyond (Rosenblatt, 1978; Ryan & Dagostino, 2017).

Recommendation: contextualised experiences that promote transfer of knowledge within the design of future VIs might include:

-

The incorporation of pre and follow-up activities including discussions, further research, retellings or re-enactments of the VI, and response drawings or writing (Agosto, 2016).

-

The establishment and utilisation of socio-dramatic play scenes (Robertson et al., 2020) and Makerspaces (Marsh, et al., 2019) that use, consolidate, and extend language and learning beyond the VI.

-

Engaging students in aesthetic and efferent talk during and post the VI so that factual and imaginative language can be developed in the context of learning new things and solving novel problems

9.6 Principle 6 (a new principle): the experience provides opportunities to access resources beyond familiar contexts

Through testing the principles across three iterations, an additional principle became evident, one that particularly applies to learners and educators in RRR communities. This sixth principle relates to access that transport the learner beyond their familiar contexts and into new spaces and places for learning. Given that there is no dispute that the digital divide, including insufficient internet connectivity and outdated hardware, is a challenge for many in RRR communities, physical and personal access to VIs for all learners and educators is crucial.

A limitation of all VIs in this study and perhaps more generally is that, if students are unable to physically access or connect with VIs, the experiences offered are meaningless. While this research has demonstrated the unquestionable value of VIs and their potential to provide participants with new language, content knowledge, and places and ways of understanding, further research is required to explore possible means for VIs to engage with disconnected students located within RRR areas. In turn, when designing or determining the quality of a VI, one must acknowledge all participants’ existing knowledge and expertise so it may be accessed and valued throughout the interactions.

The ability of a VI to acknowledge different experiences and understandings that users may bring is important because the experience becomes more personally accessible. However, the ability to recognise students’ existing knowledge and lived experiences and connect to these within the VIs examined was an undervalued and misrecognised area within each iteration. Limitations could be found in the ways each experience was constructed, for example, there needs to be something within the interaction that the learners can relate to. When the whole experience is alien to the very nature of a learner’s life, it becomes extremely difficult for them to align current experiences, understandings, beliefs, and abilities to the new information being presented.

For children to access the wealth of possibilities VIs offer, facilitators must create a shared experience for connection. Aligned with Keene and Zimmerman’s (1997) concept of text-to-text, text-to-self, and text-to-world connections, young participants require opportunities to make VI-to-self, VI-to-place, and VI-to-text connections throughout the interaction. Essentially, for VIs to successfully provide access to unfamiliar contexts, the nature of the interaction must involve “difference, connection and reciprocity” (Boldt, 2020, p. 11). When a VI fails to foster a reciprocal relationship and exchange between facilitators and participants within RRR classrooms, they unwittingly view these students and their perspectives as deficit. The future development of VIs plays a significant role in challenging deficit thinking. By presenting the opportunity for even the most isolated students to share their lifeworlds and expertise, VIs can position RRR participants as “active contributors…co-creators, knowers, learners…and community members” (Edwards-Groves, 2014 p. 11).

10 Conclusion

This research demonstrates the potential of VIs in easing some inequities in educational experiences available to RRR communities. As Symes (2012) affirms, geographic location “should not comprise educational opportunity” (p. 505). The study demonstrates the importance of virtual interactions in that they offer a rich stimulus, provide shared experiences between creators and students, and enable access to new information where learning is scaffolded with the ambition that knowledge is transferred between virtual and physical learning worlds. Highlighted too are the personal advantages afforded by access to new physical geographies through virtual interactions for those in regional, rural, and remote communities. The benefits are particularly clear when the expertise of those living in regional, rural, and remote communities is acknowledged, valued, and celebrated within the virtual interaction.

Data availability

Data will be made available on reasonable request.

References

Adlington, R. (2014). Exploiting the distinctiveness of blogs to overcome geographic isolation. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 24(3), 1–13.

Agosto, D. E. (2016). Why storytelling matters: Unveiling the literacy benefits of storytelling. Children and Libraries, 14(2), 21–26.

Alexander, R. (2008). Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. Dialogos.

Alloway, N., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2009). ‘High and Dry’ in rural Australia: Obstacles to student aspirations and expectations. Rural Society, 19(1), 49–59.

Amiel, T., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Design-based research and educational technology: Rethinking technology and the research agenda. Educational Technology and Society, 11(4), 29–40.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2016). Student diversity. Retrieved September 2020, from Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority: https://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/student-diversity

Boldt, G. (2020). Theorizing vitality in the literacy classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 1- 15

Bromley, T. (2019). Enhancing children’s oral language and literacy development through storytelling in an early years classroom. Practical Literacy, 24(1), 6–8.

Burke, A. (2013). Children’s construction of identity in virtual play worlds- A classroom perspective. Language and Literacy, 15(1), 58–73.

Collins, A., Joseph, D., & Bielaczyc, K. (2004). Design research: Theoretical and methodological issues. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15–42.

Comber, B., & Kamler, B. (2004). Getting out of deficit: Pedagogies of reconnection. Teaching Education, 15(3), 293–310.

Danby, S., Evaldsson, A.-C., Melander, H., & Aarsand, P. (2018). Situated collaboration and problem solving in young children’s digital gameplay. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(5), 959–972.

Downes, N., & Roberts, P. (2015). Valuing rural meanings: The work of parent supervisors challenging dominant educational discourses. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 25(3), 80–93.

Edwards-Groves, C. (2014). Talk moves: A repertoire of practices for productive classroom dialogue. Primary English Teaching Association Australia.

Edwards, S. (2013). Digital play in the early years: A contextual response to the problem of integrating technologies and play-based pedagogies in the early childhood curriculum. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 21(2), 199–212.

Edwards, S. (2019). Digital play. In C. Donohue (Ed.), Exploring key issues in early childhood and technology: Evolving perspectives and innovative approaches (pp. 55–62). Routledge.

Elston, L. (2019). Challenges accessing high-quality professional learning in rural, regional and remote Australia. Australian Educational Leader, 41(4), 38–40.

Fenwick, T., Edwards, R., & Sawchuk, P. (2011). Emerging approaches to educational research: Tracing the socio-material. Routledge.

Fleer, M. (2014). The demands and motives afforded through digital play in early childhood activity settings. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 3(3), 202–209.

Gregory, S., Jacka, L., Hillier, M., & Grant, S. (2015). Using virtual worlds in rural and regional educational institutions. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 25(2), 73–90.

Halsey, J. (2018). Independent review into regional, rural and remote education- Final report. Sydney: Department of Education and Training

Kalmar, K. (2008). Let’s give children something to talk about: Oral language and preschool literacy. Young Children, 88–92

Keene, E. K., & Zimmerman, S. (1997). Mosaic of thought: Teaching comprehension in a reading workshop. Heinemann.

Kervin, L. (2016). Powerful and playful literacy learning with digital technologies. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 39(1), 64–73.

Kervin, L., Vialle, W., Herrington, J., & Okely, T. (2006). Research for educators. South Melbourne: Cengage Learning.

Kervin, L., Verenikina, I., & Rivera, M. C. (2015). Collaborative onscreen and offscreen play: examining meaning-making complexities. Digital Culture and Education, 7(2), 228–239.

Leander, K. M., Phillips, N. C., & Headrick Taylor, K. (2010). The changing social spaces of learning: Mapping new mobilities. Review of Research in Education, 34, 324–394.

Lester, L. (2012). Putting rural readers on the map: Strategies for rural literacy. The Reading Teacher, 65(6), 407–415.

Lieberman, D. A., Demartino, C., & So, J. (2009). Young children’s learning with digital media. Computers in Schools, 26(4), 271–283.

Marsh, J. (2010). Young children’s play in online virtual worlds. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 8(1), 23–39.

Marsh, J., & Hallet, E. (2008). Desirable literacies: Approaches to language and literacy in the early years. Sage.

Marsh, J., Wood, E., Chesworth, L., Nisha, B., Nutbrown, B., & Olney, B. (2019). Makerspaces in early childhood education: Principles of pedagogy and practice. Mind, Culture and Activity, 26(3), 221–233.

Mills, K. A., & Comber, B. (2013). Space, place and power: The spatial turn in literacy research. In K. Hall, T. Cremin, B. Comber, & L. Moll (Eds.), International handbook of research in children’s literacy, learning and culture (pp. 412–423). Wiley- Blackwell Publishing.

Mills, K., Comber, B., & Kelly, P. (2013). Sensing place: Embodiment, sensoriality, kinesis, and children behind the camera. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 12(2), 11–27.

Mitchell, A. (2019). Virtual visits: Museums beaming in live. Journal of Museum Education, 44(3), 225–228.

NSW Education Standards Authority. (2012). English K-10 syllabus. NESA.

NSW Education Standards Authority. (2015). Geography K-10 syllabus. NESA.

Parsons, D., Inkila, M., & Lynch, J. (2019). Navigating learning worlds: Using digital tools to learn in physical and virtual spaces. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(4), 144–159.

Pilgrim, J. M., & Pilgrim, J. (2016). The use of virtual reality tools in the reading-language arts classroom. Texas Journal of Literacy Education, 4(2), 90–97.

Reeves, T. (2006). Design research from a technology perspective. In J. Van den Akker, K. Gravemeijer, S. McKenney, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research (pp. 64–78). Routledge.

Reiach, S., Averbeck, C., & Cassidy, V. (2012). The evolution of distance education in Australia: Past, present, future. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 13(4), 247–252.

Reid, J.-A. (2017). Rural education practice and policy in marginalised communities: Teaching and learning on the edge. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 27(1), 88–103.

Robertson, N., Morrissey, A.-M., & Moore, D. (2020). From boats to bushes: Environmental elements supportive of children’s sociodramatic play outdoors. Children’s Geographies, 18(2), 234–246.

Rojas-Drummond, S., Torreblanca, O., Pedraza, H., Velez, M., & Guzman, K. (2013). ‘Dialogic scaffolding’: Enhancing learning and understanding in collaborative contexts. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 11–21

Rosenblatt, L. (1978). The reader, the text, and the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. Southern Illinois University Press.

Rowsell, J., Burke, A., Flewit, R., Liao, H.-T., Lin, A., Marsh, J., . . . Wohlwend, K. (2016). Humanizing digital literacies: A road trip in search of wisdom and insight. The Reading Teacher, 70(1), 121–129

Ryan, K., & Dagostino, L. (2017). The coding, scoring, and analysis of teachers’ responses following exposure to Louise Rosenblatt’s theories of reading. The New England Reading Association Journal, 52(2), 35–48.

Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2009). Conceptualising progression in the pedagogy of play and sustained shared thinking in early childhood education: A Vygotskian perspective. Education and Child Psychology, 26(2), 77–89.

Stacey, E. (2005). The history of distance education in Australia. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6(3), 253–259.

Sutton, S., & Kemp, S. (2011). The paradox of urban space: Inequality and transformation in marginalized communities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Swan, A. K., Sleeter, N. M., & Schrum, K. (2019). Teaching hidden history: A case study of dialogic scaffolding in a hybrid graduate course. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 1, 1–28.

Symes, C. (2012). Remote control: A spatial history of correspondence schooling in New South Wales. Australia. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 16(5), 503–517.

Taronga Conservation Society Australia. (2019). Our backyard: Annual report 2018–2019. Taronga Conservation Society Australia.

Thibaut, P. (2015). Social network sites with learning purposes: Exploring new spaces for literacy and learning in the primary classroom. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 38(2), 83–94.

Verenikina, I., & Kervin, L. (2011). iPads, digital play and pre-schoolers. He Kupu, 2(5), 4–16.

Verenikina, I., Kervin, L., Rivera, M., & Lidbetter, A. (2016). Digital play: Exploring young children's perspectives on applications designed for preschoolers. Global Studies of Childhood, 6(4), 1–12.

Welch, A. (2007). The city and the bush. Education, change and society, 70–93

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, E., Mantei, J. & Kervin, L. Investigating key principles for the design of virtual interactions for children that can support the development of oral language through play. AJLL 46, 105–124 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-023-00031-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44020-023-00031-9