Abstract

China’s national Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the largest ETS in terms of the amount of CO2 regulated, was launched on the trading platform operated by the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange (SEEE) on July 16th 2021, and has successfully completed its first compliance cycle on December 30th, 2021. During the operation of its first cycle, China’s national ETS differs from other international ETSs in many aspects, including trading products and participants, allowance allocation method, compliance term, and offset mechanism, leading to certain unique trading patterns. Some unique settings are worth noticing including key emitters dominated by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) who also dominate transactions, large-scale power groups’ carbon strategies, allowances for 2 years of 2019 and 2020 being processed in one compliance period and allowed inter-year banking of allowances. All these have led to trading patterns characterized by cyclical demand-driven trading, insufficient trading capabilities of regulated entities, stable allowance price and an increased price of CCER. Nonetheless, the successful running of its first compliance cycle offers invaluable experience for future ETS development in operational mechanism improvement, sector coverage expansion, allocation optimization, and introduction of different types of market players and tradable products, and provides a good reference for future international expansion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Emission trading scheme (ETS) and its development in China

1.1 Key issues in ETSs worldwide

ETS, as an important political instrument for addressing emission control, has been discussed extensively on its effectiveness on emission reduction, as well as various implementation results shaped by different policy context and practical measures. ETS-related policies on emission control have been generally considered to have a positive effect on both reducing emissions and promoting the presence of carbon sinks, while ETS, the market itself, is not only affected by merely emission-based policies, but also by other regulations, and most importantly, the design and changes of market mechanism itself [1,2,3,4,5].

Carbon pricing has dominated climate change conversations in recent years, and 25 ETSs in force have been established across the globe [6]. Among these markets, there are matured ones, such as EU ETS and California ETS, and also newly established ones, including China’s national ETS, the world’s largest carbon market now under the spotlight with huge potentials looking ahead. As ICAP mentioned in its 2022 report, ETSs play different roles in various jurisdictions in low-carbon transition, which then leads to distinct decisions on market development and reforms when adjusting it to challenges and opportunities in the near future [6].

1.1.1 The majority of studies focused on Europe despite many established markets worldwide

EU ETS, the first and most influential carbon trading system established worldwide, often benefits ETSs elsewhere with its experience in policy making and mechanism design, especially conducive for their early-stage development. Researchers and policy makers have drawn a couple of retrospective conclusions on how the market was shaped and its reflection on policy-making. Bayer and Aklin [5] found that the low carbon prices didn’t eliminate the emission reduction impact of EU ETS. Goulder [7] pointed out the interaction of regulations from all aspects being a key element for the implementation of cap-and-trade programs in the EU ETS, influencing both the environmental and economic effectiveness. Perthuis and Trotignon’s [8] analysis emphasized that the carbon price played a major role in deciding the economic efficiency of the policy, and the EU ETS regulations would modify both regulated entities’ and speculative investors’ short-term and long-term market behaviors. More specifically, Martin, Muûls, and Wagner [9] found that in the early phase of the EU ETS, regulated entities executed trades mostly for compliance purposes, without exploiting the economic opportunities of the permit market to the fullest. With regulated and non-regulated entities both participating in the market, Phase I of EU ETS (2005-2007) showed a diverted carbon price from marginal abatement cost [10] and was mainly affected by energy prices and weather conditions [11].

1.1.2 China’s national ETS has its own economic and political foundations

President Xi Jinping made the statement that “China will strive to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.” On the 75th session of the UN General Assembly in 2021 September [12]. It shows huge commitment and ambition as China is still undergoing its way as a developing country with a traditional energy consumption structure, which also means China has to bring its own solution to achieve these goals. Thus, the expectation on carbon market to both reduce emission and achieve green economic transition is high as it is considered to be a proper policy design to balance low-carbon transition promotion and economic development simultaneously [13, 14]. Several key elements affecting China’s national ETS’ effectiveness have been mentioned repeatedly, including allowance allocation benchmarks, a proper cap setting, a potential auction mechanism, emission reduction capacity of covered enterprises, and economic structure stability [15, 16].

As China’s national ETS has finished its first compliance cycle and much relevant discussion has still been heating up, and it is essential to dive deeper into the real market performance and dig key implications from its unique characteristics, its differences with EU ETS, and its operation comparing to the theoretic expectation.

1.2 Development of ETSs in China

1.2.1 The history flow of ETSs’ establishment in China went on a steady pace from pilot markets to the national market

China’s ETS has been under development since 2013 with the pilot markets [17] when the state launched seven pilot carbon markets in seven provinces and cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Shenzhen, Chongqing, Guangdong and Hubei. As pilot markets show certain differences in mechanism design and administrative measures [18], a national level unified carbon market would facilitate market transactions further and promote the economic efficiency of carbon pricing to achieve better environmental outcomes [19]. After several years of trial operation, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the former carbon market competent authority, officially announced the decision to establish a national ETS in 2017. Shanghai was designated to develop the trading system for China’s National ETS according to central government arrangements with the principle of shaping uniform standards from five aspects, including covered sectors, Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (MRV), allowance allocation, trading and market supervision.

As pioneers in China’s carbon market, the local pilot carbon markets remain parallel to the national one currently, and will gradually merge into the national carbon market, as the latter enlarges its sector coverage. Key compliance entities included in the national ETS will no longer participate in the regional markets, according to state regulations,Footnote 1 while the regional markets continue to play their roles and serve as pilots for trial policies and products [2].

Although general rules of ETS have been considered in the market design by adopting well-accepted methods in allowance allocation, compliance rules, and MRV, China’s national ETS differs in market mechanisms from pilot markets and the EU ETS, and inevitably has a few drawbacks as a new market. First, Only the power generation sector is being included. The national ETS chooses to start with the power sector for several reasons, among which the most prominent is that the power sector has relatively large emission volume and robust and available database. Second, China’s system determined its emission target based on the actual output levels and benchmarks, aiming to find a balance between industrial growth and emission reduction. Four benchmarks are determined by power set categories considering their fuel types, industry standard and the national emission target. The benchmark method is adopted in the national market since it has been proven reliable in pilot markets and optimal for power generation sector while serving regional distributional objectives at the same time [20]. The allocation process involves two steps, pre-allocation and verification. First, entities receive allowances at 70% of their 2018 output multiplied by the corresponding benchmark. Second, the allocation amount will be adjusted, in account for excess and deficiency, to reflect actual generation in 2019 and 2020. Thirdly, allowances under the national ETS are bankable for a more robust carbon price and a stable transition between compliance cycles, which is a major lesson drawn from the EU ETS. Last but not least, the trading capacity of China’s national ETS falls short of that of the EU ETS due to the lack of variety both in products and market participants, and inadequacy in market supervision as well.

As confirmed as part of the “1 + N policy” framework in October 2021, the national ETS will be an important measure to achieve China’s carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. Despite some shortcomings as a new market, China’s national ETS has been operating in a stable manner since its launch on July 16th 2021, and has completed the first compliance cycle successfully [18]. The regulated entities have shown their strong recognition of the trading mechanisms, market rules and carbon prices, and are better prepared for future participation in the scheme to help fulfill China’s carbon peaking and carbon neutrality targets.

2 The first compliance cycle of China’s national ETS

2.1 The large-scale market has shown a promising start

After 114 days of trading, China’s national market completed its first compliance cycle with a cumulative transaction volume of 178.79 million tonnes of Chinese Emission Allowances (CEAs) totaling 7.66 billion yuan (1.20 billion dollars)Footnote 2 in value, which surges quickly in the later stages (see Fig. 1), and a compliance rate of 99.5%.Footnote 3 The closing price was 54.22 yuan (8.50 dollars)/tonne, up by 13% and 5.84% compared to the opening price and closing price on the first day, respectively. The spot trading scale of carbon allowance secondary market ranks first among the international spot markets during the same period.Footnote 4 The market operates soundly with a gradual and promising expansion in scale, and has begun to show its effect on promoting emission reduction and green and low-carbon transition [21].

CEA’s Accumulative Transaction Volume and Turnover in the National ETS (Retrieved and calculated from open data on https://www.cneeex.com/)

To understand how China’s national ETS operated at its early phase and what will be the next steps, the market performance of the first compliance cycle of China’s national ETS needs to be analyzed in depth.

2.1.1 Market participants analysis

In its first compliance cycle, China’s National ETS has covered a total number of 2162 key compliance entitiesFootnote 5 from the power generation sector. Most of the regulated entities are State-owned enterprises (SOEs). Over 90% of them participated in the carbon market for the very first time, as only 186Footnote 6 of them had been regulated in the pilot carbon markets before. Even though Measures for the Administration of National Carbon Emission Trading (Trial) [22] stated that all authorized regulated entities, institutions, and individual investors are allowed to engage in trading activities in the national carbon market, trading of spot allowances was limited to the 2162 power generation companies in the first compliance cycle.

Further, all emission allowances were distributed to regulated companies by the government for free as determined by benchmarks. The first compliance period also featured an upper limit on compliance obligations, intending to ease the compliance burden for all regulated entities, especially for those who face a huge allowance deficit.

2.1.2 Distribution of covered enterprises by province

The provincial distribution of key power generation companies involved in the first compliance cycle was significantly uneven as expected, considering different industrial structures in the provinces. Shandong and Jiangsu provinces, which are highly dependent on heavy industries, have more than 200 regulated companies, accounting for 1/4 of the national total, while only seven companies are covered in Hainan Province. (see Fig. 2) [23].

2.2 Market performance analysis

2.2.1 Transaction activity

Considering only one product, the CEA spot, was being traded on the national platform, the overall market liquidity was remarkable, with a cumulative trading volume of 178.79 million tonnes, an average daily trading volume of 1.57 million tonnes, and a transaction turnover rate at around 3%. The total spot trading volume has even reached several times that of the rest of the international carbon markets over the same period. However, most trades happening in international carbon markets come from futures trading. For example, the EU ETS, with a highly developed and active carbon financial market, attributed more than 92% of its quarterly trading volume to carbon futures trading, with a turnover rate as high as 417% in the fourth quarter of 2021.Footnote 7 In contrast, China’s national carbon market is still in the early stage of development, leaving much space for improvement in market activity level.

2.2.2 Transaction distribution

Launched in the second half of the year, the national market had a relatively short first compliance cycle and a truncated trading period of 114 days. The CEA transactions showed obvious periodic patterns. Most trades happened close to the allowance surrender deadline. As Fig. 3 shows, the trading-heat gradually waned after the trading of 4.1 million tonnes on the first day, and from July to October, the total transaction amount was around 20.2 million tonnes, with the average daily turnover of less than 300,000 t. At the end of October, Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) issued a notice of allowance surrender for the first compliance cycle to further clarify the compliance requirements [24]. Since then, the national carbon market trading volume began to soar. In November, the average daily transaction volume exceeded 1 million tonnes, and the monthly transaction exceeded 23 million tonnes, more than the sum of the previous 4 months. The average daily trading volume exceeded 5.8 million tonnes in December, and the total trading volume reached 136 million tonnes, twice as much as the total of the previous 5 months.Footnote 8 These data imply that compliance could be the main driving force of trading, and the current carbon price reflects more the short-term demand-driven mentality under compliance pressure.

CEA’s transaction price and volume (Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/ )

2.2.3 The formation and trend of carbon price

The listed price trend shows a “smiling curve”: the first compliance cycle of the national carbon market experienced a high carbon price at the beginning when the market was launched, a relatively low price in the middle period, and a rising carbon price in the end. The opening price of the national carbon market was 48 yuan (7.53 dollars)/tonne on the opening day and it continued to grow during the first week, reaching over 60 yuan (9.41 dollars)/tonne. Then the price fluctuated downwards and stayed at about 42 yuan (6.59 dollars)/tonne in October until it spiked again in December, with a closing price of 54.22 yuan (8.50 dollars)/tonne on the last day of the first compliance cycle, which increased by 13% and 5.84% compared to the opening price and closing price on the first day, respectively.Footnote 9

Throughout the 114 days of trading, the price reached its highest at 62.29 yuan (9.77 dollars)/tonne on December 30, and its lowest at 38.5 yuan (6.04 dollars)/tonne on October 27. In addition, a price high as 61.07 yuan (9.58 dollars)/tonne flashed on July 23. Compared to the price in the pilot carbon markets, that of the national ETS’ first compliance period is generally higher and less volatile, as it attained average trading price of 42.85 yuan (6.72 dollars)/tonne and the closing prices remained within a reasonable fluctuation range of 40-60 yuan (6.27-9.41 dollars)/tonne.Footnote 10

The transaction price gradually rose as the demand for surrender increased. The price increments reached the daily limit for several consecutive days near the compliance deadline. The overall stable carbon price not only reflected the credibility of the system and the recognition of the carbon assets’ value by enterprises, but also helped entities avoid potential burdens from excessive prices [25].

3 Achievements and implications from the first cycle

3.1 The market ran smoothly and orderly with reasonable price fluctuations

The first compliance cycle ran smoothly as regulated enterprises gradually became familiar with the market rules, and were ready to participate in market transactions, while the local competent authorities were also constantly improving institutional arrangements. The concerted efforts of all parties in completing the first compliance cycle offered invaluable experience for the future development of the carbon market [21].

As mentioned previously, the carbon price fluctuation in the first compliance cycle has always been within a reasonable range. The stable carbon price may be attributed to the bankable allowance use and lesson learning from other markets’ experience. Throughout the compliance period, there were no drastic nor erratic movements in carbon price, and the market ran smoothly. The CEA’s closing yield fell in the range of − 2.91% to 4.08%, with an average yield of 0.02%. The stable operation of the market has been a result of past experience from pilot markets and its well-designed institutional mechanisms, which proved the feasibility of China’s carbon market framework, distribution mechanism, trading system, market expectation and risk control system. It can offer great reference to the running of the subsequent compliance cycle.

3.2 Level of market participation was high, and the compliance rate reached 99.5%, near perfect

In terms of participation, over 50% of regulated companies engaged in either CEA or Chinese Certified Emission Reduction (CCER) trades [26]. This result is quite remarkable, considering the fact that the EU ETS had only about 30% of the regulated entities actually had trading activities during its first phase [9]. The high compliance rate can be largely attributed to participants being mostly SOEs, large energy enterprises’ group asset management strategies and acceptance of CCER for compliance.

Many provinces across the country have actively fulfilled their duties and achieved emission reduction targets. On December 7, seven key emission companies in the power generation industry in Hainan Province completed the surrender of CEAs, becoming the first province in China to achieve 100% compliance [27]. As an energy-dependent province, Shandong Province has the heaviest compliance burden with more than 300 companies included in the national carbon market [28]. As of December 14th, 211 key emission companies in Shandong Province have successfully completed the surrender of CEAs, and 80 key emission companies have partially complied with the obligation [29]. On the corporation level, on December 14, China Huadian Corporation’s last of its 105 subsidiary key compliance entities completed the surrender of CEAs, making it the first corporation group to achieve group-level allowance full compliance [30].

There was a compliance gap of 0.5% of the verified allowances, or 43.4 million tonnes of CEAs equivalently in the first compliance cycle. Taking Shandong Province, which has the most emission control entities, as an example, a great majority of its regulated companies have completed compliance, as of January 10, 2022, except for 13 companies whose accounts were seized by the court and 2 companies shut down business, resulting in an overall compliance ratio of 99.82% [28]. The regulated entities that fail to complete the surrender shall be ordered to make corrections within a certain time frame and be fined between 20,000 yuan and 30,000 yuan ($3136.91 and $4705.37). If the correction deadline was again missed, the allowance of the following period shall be reduced by the same amount of the unfulfilled part, according to Measures for the Administration of National Carbon Emission Trading (Trial) [22] issued by MEE. Although the punishment of China’s ETS is relatively mild, the near to 100% compliance rate suggests that enterprises have a strong awareness and willingness to comply. The provincial departments of ecology and environment are authorized to assess the compliance and enforce the penalty. They are also in charge of regulating the non-compliance to make corrections and disclose related information. For example, in Ningxia Province, the fine for 6 non-compliance enterprises added up to 168,000 yuan ($26,350.05) and all enterprises’ compliance states have been disclosed [31].

3.3 The total transaction volume achieved a milestone

During the first compliance cycle, the CEA and CCER transaction volumes have reached 178.79 million, fully reflecting the advantage of China’s national ETS in its scale and capacity. The transaction volume stands for a one-time surrender for two-year allowances. Considering that there was no institutional investor or market maker participating in the first compliance cycle, and only CEA spot product was being traded, the trading volume was generated from real deals between power companies, reflecting their motivation and willingness to cooperate and to fulfil their own responsibilities in emission reduction. It also demonstrates their use of trading mechanism to cover a portion of their abatement costs and even obtain additional profits. Furthermore, such transactions manifest the real supply and demand in the market more accurately, and confirm the rationality of the allowance allocation method, in which the amount of allowance deficit for some regulated enterprises is substantial, triggering actual transaction needs, especially for those heavy emitters.

3.4 Offset mechanism drives demand for CCER crediting

MEE has made it clear that it is allowed to use CCER as offset, and stipulated that the proportion of CCER for compliance purpose shall not exceed 5% of the entities’ annual verified emissions. According to the annex of the issued notice, “procedures for using CCER to offset allowance settlement in the first compliance cycle of the national ETS”, in the first compliance cycle of the national carbon market, CCER would still be traded under regional ETSs [23]. After purchasing CCER that meets the requirement, the enterprise shall apply to the provincial ecology and environment authority by submitting “the application form for settlement offset using CCER in the first compliance cycle”, with the submission window opening from October 26 to December 10, 2021, and complete the write-off of CCER after approval. According to trading data released by all authorized CCER trading platforms, firms regulated by the national ETS used more than 32 million tonnes of CCER for settlement offset, totaling over 900 million yuan (141.16 million dollars) in value in the first compliance period [32].

The introduction of offset mechanism builds connections between the national ETS and the offset credit market, provides more possibilities for compliance entities to comply, and also helps promote the implementation of GHG emission reduction projects.

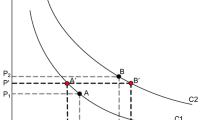

Further, considering that the pricing mechanism of CCER is guided by the cost of compliance, and is positively corelated with but lower than the allowance spot price in general, the appropriate use of emission reduction for offset can reduce the compliance cost for regulated entities, hence benefiting growth of the companies [33].

It is worth noting that the national ETS does not have any special requirements on CCER projects (except for the reduction units from projects in the industry covered by the national ETS), but the offset ceiling is set at 5% [24], which provides flexibility for regulated enterprises to comply, whilst keeping the CCER market from excessive fluctuations. Overall, the national carbon market has begun to show its significance in promoting regulated entities-level GHG emission reduction and in accelerating green and low-carbon transition.

4 Prospects for China’s ETS

In general, the first compliance cycle of China’s national ETS provides invaluable experience for its future development. Inspired by the market performance, following suggestions from five aspects may be considered as the national ETS grows.

4.1 Set the total amount of carbon allowances moderately tight, and introduce an auction mechanism

In December 2021, the Chinese government reinforced the relevance of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals, emphasizing the urge to shift from controlling both the total amount and intensity of energy to controlling the total amount and intensity of carbon emissions,Footnote 11 which points out clearer direction for the development of the carbon market.

First, the total amount of carbon allowances will be set moderately tight to maintain a reasonable supply and demand level. The allowances allocation mechanism will take into consideration the level of economic development, capacity for enterprise growth, comprehensive efficiency of the industry and other factors.

Second, the auction mechanism for allowance allocation should be further developed and promoted. Measures for the Administration of National Carbon Emission Trading (Trial) [22] clearly states that a paid allocation mechanism can be introduced orderly according to relevant national requirements. Currently, the carbon market still adopts free allocationFootnote 12 in order to help covered entities adapt to the newly-established carbon market and keep the market functional. As the carbon market develops, the national carbon market would require a gradual transition to realize the fairness of the initial allocation, and set the retention price of paid allocation to avoid a potential low carbon price, which could incentivize entities in emission reduction [34]. The national market may refer to the operation experience of the pilot markets. For example, the Shanghai pilot carbon market changed from completely free allocation to the partially paid allocation with a 1% ~ 7%Footnote 13 proportion being auctioned, depending on the compliance status.

4.2 Orderly expand the coverage and capacity of the ETS

The expansion of the sector coverage based on stable market operation is essential, as it enhances the national ETS’ relevance by maximizing the roles of the carbon price in incentivizing and supporting covered entities [35]. Carbon trading will play a more significant role in guiding the market especially after more entities with diverse emission reduction costs will be included.

According to the principle of “include once one is mature”,Footnote 14 China’s ETS plans to cover eight high-emission industries during the “14th Five-Year Plan” period. It is expected that after the complete coverage of the eight key industries, the total amount of allowances covered in the national carbon market may expand from the current 4.5 billion tonnes to nearly 7 billion tonnes, encompassing over 60% of China’s total carbon dioxide emissions. In 2021, the Department of Climate Change of MEE officially commissioned China Building Materials Federation and China Iron and Steel Industry Association to carry out the inclusion plans for building materials industry and steel industry respectively [36]. It is expected that, within 2 years, these two industries will become the second batch of sectors to be regulated in the national carbon market.

4.3 Strengthen market supervision and gradually introduce institutional investors and other entities at an appropriate time

Currently, all aspects of the market operation, including MRV, allowance allocation, trading, compliance, as well as emission reporting, allowance registry and the operation of the trading systems, are under the unified supervision of MEE. The regulations on registry, trading, settlement, activity supervision, risk tracking, early warning and emergency response, and responsibilities and penalties settings will also be amended and implemented, along with the development of the carbon market.

As the market supervision system is established and refined, more types of authorized investors would be introduced to the market. Participants with various risk preferences, market expectations, and trading strategies will help to form a carbon price that can more accurately reflect the market’s supply-demand expectations and the emission reduction cost. The access of mutual funds, hedging funds, asset management firms and other financial institutions will not only help improve the liquidity of the carbon market, but also develop cross-market strategies. One example is to purchase both spot and futures from the carbon market and another energy market to hedge market risks. Financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies could use the carbon market as an investment channel and provide financial intermediary services to carbon market participants, which may also help promote spot and derivatives transactions in the future, facilitate the circulation of allowances and other carbon assets, and further invigorate overall trading activities.

4.4 Gradually increase the product varieties and accelerate product and service innovation

In accordance with the requirements of the Interim Regulations for the Management of Carbon Emissions Trading (draft), carbon finance and relevant services shall be introduced in a timely manner [35]. Carbon market related derivatives shall be developed, such as carbon futures, carbon options and carbon swaps, to adequately increase market activity and liquidity, and provide diverse investment options and effective hedging options for investors. Other adjunct products and services, such as carbon funds, carbon trusts, carbon indices and carbon repurchase agreements, shall be explored to accurately match the financing or compliance demands of market participants and meet the needs of different types of participants [37]. Diversified carbon financial instruments and trading products can effectively help the market to discover and form carbon prices, and promote China’s national ETS to gradually develop from the current compliance-only market into a complex market with more financial attributes and investment value. CCER program was suspended 5 years ago in 2017 and there has not been any announcement on the relaunch plan. As the first compliance cycle indicated CCER being an important supplementary mechanism to the allowance market, the program is expected to further facilitate green industry development once relaunches.

4.5 Promote international cooperation in carbon markets

The development of carbon market should contribute to China’s major-country diplomacy, and the Belt and Road Initiative. In terms of market accessibility, international investors’ participation in China’s carbon markets shall be deliberately advocated, and may refer to the experience and precedents of involving foreign institutional investors in Shenzhen’s pilot market. Additionally, Hainan, Guangzhou, and Shanghai pilots are planning on standardized platforms to facilitate international trading. Regarding market globalization, cooperation with foreign markets should be strengthened by promoting international projects and harmonizing standards, to prepare domestic market for the possible future international carbon market trading, such as the Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) under the framework of Paris Agreement [38].

5 Conclusion

After years of pilot operation and continuous efforts to establish a national carbon pricing mechanism, China’s national ETS has set off to a smooth start with its first compliance cycle being a great success.

The first compliance cycle of China’s national ETS has several characteristics. First, only key compliance entities in one industry, namely power generation, were regulated in the market and engaged in trading activities. Most of the participants were SOEs, among which several large-scale energy groups. Second, only CEA spot was traded. Thirdly, the market adopted free allocation method with a relatively short and condensed trading period from allowance issuance to surrender. Fourthly, the compliance obligation covered two-year emissions and allowed for CCER offsetting. These features cultivated a unique transaction pattern of the first compliance cycle related to market behaviors.

Unique patterns were seen in transactions and price trends. The CEA transactions showed periodic patterns as most trades happened close to the allowance surrender closing date, indicating the market demand was mostly driven by compliance obligation. In terms of price trends, the first compliance cycle experienced a “smiling-curve” (high-low-high) of carbon prices. Considering only power companies were participating in trading, China’s ETS showed moderate liquidity with stable prices, but was still in its early stage of development, leaving much space for improvement in market activity.

The first compliance cycle also generated meaningful achievements and impacts. The market operated soundly with reasonable price fluctuations, and has begun to show its effectiveness and efficiency in emission reduction by a near-perfect compliance rate of 99.5%. Moreover, the total transaction volume achieved a milestone, whilst the offset mechanism drove demand for CCER crediting.

For further development, China’s ETS should continue to refine its mechanism from multiple perspectives. First, tighten the total amount of CEAs moderately to maintain a reasonable supply and demand level, and introduce an auction mechanism to realize fairness in the initial allocation. Second, orderly expand ETS’ coverage and capacity to include diverse abatement costs from different sectors, thus enhancing ETS’ influence and maximizing the effects of carbon price. Thirdly, strengthen market supervision and gradually introduce eligible investors to facilitate the circulation of carbon assets and further invigorate the trading activity. Fourthly, introduce more product types and accelerate relevant innovation to turn the current compliance-only market into a more complex market. Last but not least, promote international cooperation to prepare better for international carbon market trading.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Notes

Measures for the Administration of National Carbon Emission Trading (Trial)

All monetary values in CNY are converted to USD using the USD/CNY exchange rate at 6.3757 on December 31 2021, obtained from China Foreign Exchange Trade System (National Interbank Funding Center) https://www.chinamoney.com.cn/chinese/bkccpr/

Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202112/t20211231_965906.shtml

Compared across Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/; Intercontinental Exchange https://www.theice.com/index; European Energy Exchange https://www.eex.com/en/; Korean Emissions Market Information Platform https://ets.krx.co.kr/main/main.jsp; New Zealand platform https://www.commtrade.co.nz/; etc.

Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/

Calculated from published enterprise lists

Calculated from transaction data published on Intercontinental Exchange https://www.theice.com/index and European Energy Exchange https://www.eex.com/en/ .

Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/

Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/

Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/

The annual Central Economic Work Conference in December 2021

2019 – 2020 National Carbon Emission Trading Cap Setting and Allowance Allocation Implementation Plan (Power Generation Industry), MEE

Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange https://www.cneeex.com/

Mentioned on press briefing by MEE spokesman Youbin Liu, on July 16th 2021. https://m.weibo.cn/status/4663193894656895?wm=3333_2001&from=10C4093010&sourcetype=weixin

Abbreviations

- CCER:

-

China Certified Emission Reduction

- CEA:

-

China Emission Allowance

- ETS:

-

Emissions Trading Scheme

- EU:

-

European Union

- GHG:

-

Greenhouse gas

- ICAP:

-

International Carbon Action Partnership

- ITMO:

-

Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcome

- MEE:

-

Ministry of Ecology and Environment of People's Republic of China

- MRV:

-

Monitoring, Reporting and Verification

- NDRC:

-

National Development and Reform Commission of People's Republic of China

- SEEE:

-

Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange

- SOE:

-

State-owned enterprise

- UN:

-

United Nations

References

Bushnell JB, Chong H, Mansur E (2013) Profiting from regulation: evidence from the European carbon market. Am Econ J Econ Pol 5(4):78–106

Hua Y, Dong F (2019) China’s carbon market development and carbon market connection: a literature review. Energies 12(9):1663. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12091663

Cui J, Wang C, Zhang J, Zheng Y (2021) The effectiveness of China’s regional carbon market pilots in reducing firm emissions. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(52):e2109912118

Colmer, J., Martin, R., Muûls, M., & Wagner, U. J. (2022). Does pricing carbon mitigate climate change? Firm-level evidence from the European Union emissions trading scheme

Bayer P, Aklin M (2020) The European Union emissions trading system reduced CO 2 emissions despite low prices. Proc Natl Acad Sci 117(16):8804–8812. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918128117

ICAP (2022) Emissions trading worldwide: status report 2022. International Carbon Action Partnership, Berlin

Goulder LH (2013) Markets for tradable pollution allowances: what are the (new) lessons? J Econ Perspect, 27(1),87–102 (Winter2013)

Perthuis C de, Trotignon R (2014) Governance of CO2 markets: lessons from the EU ETS. Energy Policy, 75, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.05.033

Martin R, Muûls M, Wagner UJ (2014) Trading behavior in the EU emissions trading scheme. Available at SSRN 2362810

Balietti AC (2016) Trader types and volatility of emission allowance prices. Evidence from EU ETS phase I. Energy Policy 98(C):607–620

Mansanet-Bataller M, Pardo A, Valor E (2007) CO2 prices, energy and weather. Energy J 28(3)

UN News(2021) China headed towards carbon neutrality by 2060; President Xi Jinping vows to halt new coal plants abroad https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1100642

Zhang H, Zhang R, Li G, Li W, Choi Y (2020a) Has China’s emission trading system achieved the development of a low-carbon economy in high-emission industrial subsectors? Sustainability 12:5370

Zhang Y, Liang T, Jin Y, Shen B (2020b) The impact of carbon trading on economic output and carbon emissions reduction in China’s industrial sectors. Appl Energy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.114290

Ma R, Qian H (2022) Plant-level evaluation of China’s National Emissions Trading Scheme: benchmark matters. Climate Change Econ 13(01):Article 2240009. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2010007822400097

Wang W, Xie P, Wang W, Zhao D (2022) Overview and evaluation of the mitigation efficiency for China’s seven pilot ETS. Energy Sources Part a: Recovery Utilization Environ Effects, 44(1), 1798–1812. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567036.2019.1646352

Wang K, Li S, Lu M, Wang J, Wei Y (2022) Review and Prospect of China's carbon market (2022) (forecasting and prospects research report). CEEP-BIT

Shi Y, Nie B, Wang L, Chen Y (2021) Research on building a unified market for carbon assets and carbon trading in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Low Carbon World. https://doi.org/10.16844/j.cnki.cn10-1007/tk.2021.03.125

Li D, Sun Y (2022) To build a national unified carbon market, where will the local carbon markets go? 21st century Business, 6

Goulder LH, Long X, Lu J, Morgenstern RD (2022) China's unconventional nationwide CO2 emissions trading system: cost-effectiveness and distributional impacts. J Environ Econ Manag 111:102561

MEE (2021) The first performance cycle of the national carbon market ended smoothly. Available at https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/ydqhbh/wsqtkz/202112/t20211231_965906.shtml

MEE (2021) The National Measures for the Administration of Carbon Emission Trading (Trial). Available at https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk02/202101/t20210105_816131.html

MEE (2021) Allocation Plan for the Power Sector (2019 – 2020) and list of covered entities. Available at https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk03/202012/t20201230_815546.html

MEE (2021) Notice on the First Compliance Cycle of Emission Allowance Surrendering for the National ETS. Available at https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202110/t20211026_957871.html

Zhang W, Li J, Li G, Guo S (2020) Emission reduction effect and carbon market efficiency of carbon emissions trading policy in China. Energy 196:117117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117117

Shanghai Securities News(2022) Carbon finance innovation is ready to takeoff as national carbon market celebrates its first anniversary of its launch. https://news.cnstock.com/industry.rdjj-202207-4922870.htm

Department of Ecology and Environment of Hainan Province (2021) Hainan province took the lead in completing the carbon allowance surrender of the first performance cycle of the national carbon market. Full announcement available at http://hnsthb.hainan.gov.cn/

Department of Ecology and Environment of Shandong province (2022) Full announcement available at http://sthj.shandong.gov.cn/dtxx/hbyw/202201/t20220118_3842145.html

China Economic Network(2021) The first carbon emission compliance cycle is coming to an end, while the trading in the national carbon market has increased significantly

Zhang J (2022) Multiple measures and intensive management help achieve the "dual carbon" goal. China Power Enterprise Management 3

Department of Ecology and Environment of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (2021) Announcement of Ningxia Hui autonomous region on the allowance surrender completion of emission entities engaged in the first performance cycle of the national carbon market. Full announcement available at https://sthjt.nx.gov.cn//page/news/article/202204/20220426142450EjH4WK.html

Li X. & Zhang X. (2022). The first compliance cycle of China ETS ended smoothly and embarked on a new journey. China Environment Newspaper, 2022-01-24 (01). http://epaper.cenews.com.cn/html/2022-01/24/content_73438.htm

Huang W, Wang Q, Li H, Fan H, Qian Y, Klemeš JJ (2022) Review of recent progress of emission trading policy in China. J Clean Prod 349:131480

Verde SF, Galdi G, Alloisio I, Borghesi S (2021) The EU ETS and its companion policies: any insight for China's ETS? Environ Dev Econ 26(3):302–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X20000595

MEE (2021) Interim Regulations for the Management of Carbon Emissions Trading (draft). Available at https://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202103/t20210330_826642.html

China Building Materials Federation (2021) MEE authorizing China Building Materials Federation to carry out relevant work on the integration of building materials industry into the national carbon market. Available at http://www.cbmf.org/cbmf/yw/7076283/index.html

Zhou K, Li Y (2019) Carbon finance and carbon market in China: Progress and challenges. J Clean Prod 214:536–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.12.298

Paris Agreement (2015) Paris agreement. In report of the conference of the parties to the United Nations framework convention on climate change

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JL: Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation and Writing-original draft, Writing review & editing. YY: Investigation, Validation, Writing review & editing. XW: Investigation, Validation, Writing review & editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JL is an editorial board member for Carbon Neutrality and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Yao, Y. & Wang, X. The first compliance cycle of China’s National Emissions Trading Scheme: insights and implications. Carb Neutrality 1, 34 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43979-022-00035-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43979-022-00035-3