Abstract

Wastewater is the major source of the transmission of disease-causing organisms in developing countries. There is a strong association between diarrhoea and contaminated water worldwide. Evidence linking sanitation practices to a positive impact on health is scarce although many studies have reported a reduction of disease through improvements in waste management. This review in prospect examined the impact of wastewater management interventions in resource-poor countries of sub-Saharan Africa for the reduction of diarrhoeal outcomes in non-outbreak situations. This review of empirical literature identified and assessed the impact of effective wastewater management on public health in sub-Saharan Africa and evaluated the implications to public health practice. A systematic database search was carried out, relevant research articles were screened, and some of the articles were considered to contain relevant materials but only 5 met the inclusion criteria and were used in this study. Despite the limited number of studies meeting the inclusion criteria, there was reliable evidence of the impact of wastewater management in all the studies based on the strong positive statistical association between interventions and the reduction of diarrhoeal morbidity. Wastewater management interventions are effective for the reduction of illnesses due to diarrhoea in agreement with other previous reviews on water, hygiene, and sanitation interventions. This underlines the need for good strategies for effective wastewater management. This study contributes valuable insights to the existing body of knowledge and calls for sustained efforts in developing comprehensive wastewater management solutions in the quest for improved outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Waste management problems have always been with man from time immemorial [1]. The generation of waste is an inevitable reality in human life, and it continues to rise due to rapid population increase and consumption of resources. In the developing world, an estimated 2.5 billion people lack access to quality water treatment and about 50% of them have no access to wastewater management [2]. Developing countries are, therefore, burdened with a diversity of increasingly wastewater management problems that require serious attention [3]. This makes waste management an important issue for the preservation of life and conservation of the environment in such areas with inadequate sanitation.

Water is the major cause of the transmission of disease-causing organisms in developing countries and there is a strong association between diarrhoea and contaminated water worldwide. A recent editorial by the World Health Organisation-(WHO) proposes that over 9% of the global burden of disease can be prevented by improved water supply, sanitation, and hygiene. A key expected public health benefit of improved sanitation is the reduction of morbidity and mortality caused by diarrhoeal diseases which remain significant contributors to morbidity and mortality in resource-poor countries [4].

Wastewater refers to water that contains wastes from households, businesses, and industrial plants that are more economical to dispose of than use at the time and point of its occurrence [5]. The constituents of wastewater show diverse levels of nuisance and contamination risks to the environment due to their chemical and microbiological characteristics [6]. The composition of wastewater also varies widely based on its origin [7]. The majority of wastewater is composed of water (> 95%), which is typically used to flush and transport waste down drains. Wastewater contains pathogens that include microorganisms, viruses, bacteria and parasitic worms that can cause diseases. It contains organic particles, which include materials such as faeces, food, hairs, vomit, humus, plant materials and paper fibres. Soluble organic constituents in wastewater include soluble proteins, fruit sugars, urea, drugs and pharmaceuticals. Inorganic constituents also present include units of metal particles, sand, grit, and ceramics, among others. Soluble inorganic particles that dissolve in wastewater include cyanide, road-salt, sea-salt, and ammonia. Animals like small fish, insects, arthropods, and protozoa might be present in water, while macro-solids including larger solids that may be found in wastewater including condoms, sanitary napkins, nappies/diapers, body parts, needles, children’s toys, and dead pets, among others. Gaseous substances like methane and carbon dioxide that can# be present in wastewater. Emulsions containing mixtures that do not normally blend such as hair colourants, adhesives, paints, emulsified oils, and mayonnaise, in addition to toxic substances such as herbicides, pesticides and various poisons are also contained in wastewater [8].

Exposure to wastewater has been reported to be a risk factor for the occurrence of diarrhoea [9,10,11]. There is inadequate sanitation in most resource-poor countries with a corresponding major influence on infectious disease burden [4]. Thus, the management of wastewater is of paramount public health importance. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), wastewater management is, simply regarded as the routing of untreated sewerage to the drainage points that are, mainly, water bodies [7]. Additionally, little attention has been given to examining the level of pollution and the health risks posed by the generated wastewater. Effective wastewater management for the prevention of waterborne diseases is thus, a major concern of the World Health Organisation (WHO) for realising the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goal 7 (MDG7) of reducing by half the percentage of people without access to sustainable safe drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015 [12]. Wastewater management aims to stop the inflow of untreated sewerage by treating the source on a household, neighbourhood, or community level.

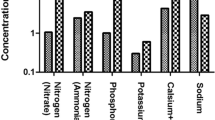

The overarching goals of wastewater management, as shown in Fig. 1, encompass safeguarding public health and the environment, addressing the growing demand, and alleviating stress on limited water resources [13]. Worldwide, there are growing concerns about water quantity and quality and the reuse of wastewater is seen as a major option to counteract the scarcity of water in dry climate regions of the world like Africa [14]. According to the WHO [15], the share of water per capita in any given watershed is rapidly dropping while the production of wastewater is significantly increasing. This is due to population explosion mostly in developing countries, climate change and other effects. The United Nations (UN) estimates that the amount of wastewater produced annually is about 1,500 km2 which is six times more than the water contained in all the rivers of the world [16].

In Africa, there seems to be rapid urbanisation without corresponding development and access to sanitation. Consequently, most water bodies are heavily polluted by wastewater in communities where rapid urbanisation overburdens the capacity to provide good sanitation and wastewater treatment [17]. Poor sanitation and the contamination of drinking water due to human activity and natural causes pose a threat to public health [7]. The major causes of water pollution include sewage and other allied waste, industrial discharges, agricultural waste matter and wastes from chemical factories, fossil fuel plants and nuclear power plants. Pollution renders water unfit for drinking, agriculture, and aquatic life. Billions of people worldwide do not have access to safe water and essential sanitation, and this has the greatest impact on public health especially in developing countries [18]. A report by WHO [19] estimated that about 40% of the global populace is short of basic sanitation and its coverage is much lesser in rural areas. The World Health Organisation and the Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council projected that 25% of urban populations in developing countries lacked sanitation access compared to 82% of rural dwellers in the same populations [20]. The inadequate access to sanitation facilities in developing countries leads to several diseases [13]. Some 3.4 million people worldwide mostly children in Africa die annually from contaminated water due to sewage disposal into their water sources according to the WHO [15].

Wastewater has also found more practical use in agriculture in many arid and semi-arid provinces of the world due to the increasing scarcity of freshwater [7]. The wide application of cheap wastewater in agriculture is impelled by rapid urbanization and an increase in wastewater volumes despite the health and environmental risks [21]. This wastewater is used both with and without treatment in agriculture. Recent research by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) in Ghana, Pakistan, Vietnam and Mexico examined the positive and negative impacts of the reuse of wastewater in agriculture. The positive effects of wastewater use in agriculture include the conservation of water, cheap methods for the disposal of wastewater, providing a reliable source of water to farmers, improving crop yield by providing natural nutrients and reducing the potential pollution of canals, rivers and other surface water resources. Negative impacts reported include risks to farmers and communities with prolonged contact with untreated wastewater, consumers of farm produce irrigated with contaminated wastewater, provision of habitat for disease vectors and soil pollution by heavy chemicals.

Significant progress has been made globally in the treatment of wastewater in most urban areas compared to rural areas which are still lagging. However, in Africa, only about 1% of generated wastewater is treated and the rest is discharged into rivers, lakes and oceans untreated [13]. Wastewater treatment plants also represent major investments because they are capital-intensive both in operations and maintenance costs. These plants are inadequately operated in many developing countries due to limited funds, inadequate local expertise, and the lack of funding support [22]. However, small and remote villages or communities with low population mass can be served by decentralized systems that are simpler and more cost-effective [23]. The costs associated with large, centralized capital-intensive sewerage facilities can therefore be greatly cut to improve the affordability of wastewater management facilities. However, inappropriate technology can be selected concerning the local climatic and physical conditions, availability of funds and appropriate manpower and social and cultural acceptability [13].

A study by the United States Environmental Protection Agency-(USEPA) in 2005 [24] suggested that decentralised systems for wastewater management are more suitable for communities with low population density, and different locations and are more cost-effective than centralized systems. This may include the use of septic tanks and other advanced systems. Moreover, the effectiveness of the decentralized wastewater management systems depends on regular inspection and maintenance.

The three main components of every wastewater management structure are collection, treatment, and disposal [13], as shown in Fig. 2. The collection of wastewater is the least important of the three components in any centralized wastewater management system but costs more. The decentralized systems limit the collection of wastewater and centre primarily on the treatment and disposal of wastewater. Decentralized wastewater management is mostly considered for resource-poor nations, especially in SSA due to its low cost and being a more ecological form of sanitation [25]. The centralized systems are publicly owned and manage waste for communities while the decentralized systems treat wastes of homes and buildings [24].

Wastewater management encompasses a comprehensive process involving the collection, treatment, and responsible disposal of wastewater components. A recent report suggests that many urban households in developing countries are not joined to central sewers while some major cities have no functional wastewater management systems even in the central districts [26]. Moreover, many people living in resource-poor countries do not have personal toilets but resort to public facilities or open defecation.

1.1 Research objectives

This piece of research work aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of wastewater management interventions in SSA. This work included all relevant studies that meet the inclusion criteria to help establish the effectiveness of reported interventions.

The two-point objectives of this desk-based research are:

-

To review empirical literature on the impact of effective wastewater management on public health in SSA.

-

To identify the implications to public health practice.

This research sought to answer the question of the availability or absence of evidence of the impacts of wastewater management in SSA. With dwindling water resources and increased generation of wastewater and subsequent pollution of water bodies in SSA, this research aims to establish the impact of management strategies on the people and the environment.

2 Framework for household wastewater management in Africa

There are inadequate formal sanitation and sewage systems in most cities in SSA [27]. About 2.4 billion people cannot afford even simple latrines leading to water pollution by human excreta. In Africa, about 30% of water sources in rural settlements are not functioning at any given time [28]. As of 2006, 28% of people in SSA or 221 million people practice open defecation [29]. Most wastewater treatment plants are not working and are often polluted due to their origin and nature. There is therefore a need for adequate collection, storage, transportation and treatment of wastewater from industries, public places and households.

Figure 3 presents the average household sanitation facilities in SSA. The figure shows that the largest group of the African population have access to the simple pit latrine (22%) while the smallest group (2%) consists of people connected to public sewers. The simple pit latrine is used by 16% of Africans, 4% use shared or public latrines while another 4% do not have access to any toilet facilities at all. The use of sanitation facilities such as the simple pit latrine has been reported to reduce the incidence of diarrhoeal diseases [30].

The collection of waste tends to be the duty of local authorities although its management can be both a public and private affair or solely private [31]. In the developed world like France and United States of America, wastewater services are usually contracted out [32]. On the other hand, the involvement of the private sector in the development has its focus on on-site techniques like cesspools, septic tanks and pit latrines. Even when there is public control of water supply and sanitation services, some essential components such as maintenance, tracking of leakages, metering and billing could still be contracted out.

The pathogens in wastewater that cause diarrhoea including dysentery are not very robust outside the human host [33]. Personal contacts, contaminated food and water are the main routes of transmission of these pathogens. The nature and transmission of diarrhoeal disease therefore have effects on the type of health, infrastructural, social and economic interventions appropriate to tackle the problem. There is also the need for a multi-sectoral strategy approach to solve the problem of wastewater in disease control. Planning and provision of water supply and sanitation infrastructure represents a central component of this integrated strategy [34]. The best approach for the management of wastewater is proper collection and treatment.

In public health, evidence-based practice permits for a well-informed, unambiguous and sufficient utilization of scientific evidence collected from science and social science research and assessment processes [35]. Recently, advancement in the field of public health has led to improvements in empirical standards for evidence concerning interventions and other activities which provide quality information on the epidemiology of disease and the safety, effectiveness and application of health interventions [36]. Evidence-based practice is considered not only the application of interventions in practice but also an evaluation of their effectiveness.

Research associated with evidence-based practice in public health is often classified [37]. Evaluative research measures the impact and efficacy of activities; illustrative ones permit clear and understandable observations; informative allows for identification and clarification from a specific point of view; investigative gives a measure of the association between variables; taxonomic research attempts to classify and compare variables in classes and descriptive that classify and allocate variables. The evaluative studies in this piece of work are used to evaluate the effectiveness of wastewater management interventions in SSA.

3 Methodology of review

3.1 The search for literature

The main aim of performing a comprehensive literature search was to have an all-inclusive collection of primary studies from published research. This entailed rephrasing the research question to have complete searches including published systematic reviews.

Various search engines like Google Scholar and PubMed were explored for relevant materials on this research topic. Journal shelves were also searched in the Anglia Ruskin University, Chelmsford library for important literature including the library website with assistance sometimes from the librarians. The Cochrane library for systematic reviews and other governmental and non-governmental sites (including the WHO) were also searched.

3.2 The use of keywords

Searches were done using keywords, subjects and their combinations. The keys applied included “wastewater”; “sewage”; “contaminated water” “management”; “treatment” and “Africa”. The “wastewater” and “sewage” keywords were used interchangeably in the search for materials.

3.3 The database selection

Databases relevant to public health, social and medical sciences were used to explore all aspects of this work. The advanced search option was used from the library website as well as Google. Databases searched included CENTRAL, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PUBMED, GATEWAY, Google Scholar, OMNI, University library collection, RCN journal database and British Nursing Index (BNI).

3.4 Search strategy for identifying studies

A comprehensive search of major databases was carried out of all relevant documented studies on wastewater management in Africa and its impact on disease. These searches were limited to studies done before May 2012 (when these searches were conducted). Author-based searches were conducted to identify previous works by primary researchers with additional information. The articles for this review were chosen by scrutinizing the titles and abstracts of available articles. The bibliographies of the articles were also used to identify further references.

3.5 Search terms

The search terms used include the following and the combination thereof: “Wastewater”; “Africa”; “sub-Saharan Africa”; “sanitation”; “wastewater management”; “Wastewater treatment”; “Sewage”; “Sewage management”; “Sewage treatment”; “Diarrhoea”.

3.6 Databases searched

Scientific databases searched included CENTRAL, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PUBMED, GATEWAY, Google Scholar, OMNI, university library, RCN journal database, British Nursing Index (BNI), bibliographies of scientific articles, current journals, manuscripts submitted by researchers, conference proceedings, published reports and ‘gray’ literature.

Resources were also retrieved from:

-

United Nations-WHO reports.

-

Government reports and websites.

-

Other international organisations such as WASH, UNESCO, UN-HABITAT, DFID, UNEP and other NGOs.

3.7 Selection of studies

Relevant studies that evaluated the impact of wastewater management on public health (diarrhoeal diseases) were taken into consideration.

3.8 Review method

The review method was adapted from the guide by the Cochrane Collaboration Group [38] and the protocols of UN report on The Guidelines on Decentralized Wastewater Management for Sustainable Infrastructure Development in Small Urban Areas (2011) for realising the World Health Organisation’s target under the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goal 7 (MDG7) of halving the proportion of people without access to sustainable safe drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015 [12].

3.9 Studies not considered for this review

Articles that were isolated from this work included:

-

Articles not written or translated into the English language.

-

Studies that did not include the impact of wastewater management on waterborne diseases (diarrhoea)

-

Articles that did not discuss any component of wastewater management.

3.10 Studies considered for this review

Articles considered for this study included:

-

Articles written in English language.

-

Articles written relevant to the topic area; Wastewater management and the prevention of waterborne diseases (diarrhoea) in SSA.

-

All relevant articles of components of wastewater management; collection; disposal and treatment of wastewater

-

Studies based on human populations.

3.11 Results of pilot search

A total of 41 articles were screened. 9 of the articles were considered to contain relevant materials for the review but only 5 of the articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Fig. 4).

3.12 Type of outcome measures

The outcome measures consisted of those effective in the prevention and or reduction of the prevalence of waterborne diseases (diarrhoeal outcomes).

3.13 Studies examined

In addition to the initial search, further searches of the databases were repeated after a period. The repeated searches did not reveal any further relevant materials that met the inclusion criteria making it the final search. The included studies are included in Table 1:

The studies excluded did not give baseline measurements of the impact of wastewater management sanitation interventions. The included primary studies were all journals published in SSA that considered a measurement of diarrhoeal outcomes to assess the impact of interventions. It included studies which calculated the relative risk, or which had data from which the relative risk could be calculated.

4 Results and discussion

The range of results obtained from the different primary studies reviewed indicated the important roles of the different interventions in reducing diarrhoeal outcomes. Most of the studies used for this review were on subjects less than 5 years old in mainly rural communities in SSA and therefore may have affected the generalizability of the results. However, it has been argued that children in any population are most prone to diarrheal illnesses [43].

4.1 Details of studies

There is observed heterogeneity in the results reported in the different studies, as summarised in Table 2. According to Blum and Feachem, [44], heterogeneity in reporting results may be due to differences in underlying risks. This could be due to differences that are site-specific owing to the occurrence of different pathogens, cultures and other pre-intervention conditions. The discrepancies in studies can be enhanced if researchers provide additional information about both pre and post-intervention study conditions and provide data about the pathogens causing diarrhoea [45].

4.2 Comparison with other literature

This publication contains some studies on interventions that have been evaluated in some earlier reviews and also justifies findings that there is evidence that proper wastewater management practices are effective for the reduction of diarrhoeal illnesses.

Results are also consistent with findings of other previous studies like Esrey et al. [46] and Curtis and Caincross [47] which reported reductions in the frequency of diarrhoeal illnesses using similar hygiene and sanitation interventions. Curtis and Caincross [47] further assessed the impact of handwashing interventions on diarrhoeal diseases in both developing and developed countries. However, the usefulness of hygiene interventions for the prevention of disease may not be a motivating factor for people to practice other than the desire to feel and smell fresh and follow set social standards of behaviour [45]. Curtis and Caincross [47] therefore suggested that a more effective strategy to encourage handwashing is to promote hand soaps as consumer products rather than embarking on health promotion campaigns.

Although most of the studies used for this review were on subjects less than 5 years old, hygiene knowledge and installation of pit latrines alone may not be sufficient to bring about behavioural changes but a practical approach to making these interventions necessary parts of their lives.

Esrey et al. [46] evaluated the use of ecological or dry sanitation on diarrhoeal morbidity where human faeces are treated on-site and made pathogen-free and further recycled for agricultural use. Dry sanitation may find a progressively significant role in facilitating future sanitation interventions particularly due to increasing water scarcity [45].

4.3 Latrine installation

Among the diverse interventions that are likely to reduce the morbidity and mortality due to diarrhoea, improved water supply and facilities for excreta disposal have long drawn special attention [48]. In this, review all the studies that evaluated the use of latrines for the reduction of diarrhoea reported strong associations between the state and use of latrines and reduction of diarrhoeal outcomes in the populations studied. This is consistent with the findings of Caincross et al. [30] that the use of the simple pit latrine can reduce the incidence of diarrhoea. The studies showed that latrine ownership arrangements were largely private while others had their latrine installed through mass installation interventions by local authorities. The ownership of latrines was also found by Daniels et al. [39] to be dependent on the location in which the families lived (P < 0.001) and were also more likely to use improved water sources. This meant that even though the pit latrines are most used for the disposal of excreta in SSA, distribution was not even and often depended on the socio-economic status.

4.4 Wastewater handling and disposal

The unsafe disposal of wastewater has been strongly associated with diarrhoeal episodes [27]. However, the handling and disposal of wastewater were found to be greatly associated with the nature of the urbanization process. The wealthier neighbourhoods were found to utilize more pits and latrines while the use of gutters or courtyards was more prevalent in the less economically advantaged neighbourhoods. The use of water for household cleaning and personal hygiene were two significant behavioural variables for the reduction of diarrhoea. The burial of children’s faeces in the soil was positively and significantly associated with recorded diarrhoeal incidence by an Odds Ratio of 3.36 while personal hygiene reduced the odds by a factor of 0.96 [27] while the unsafe disposal of children’s excreta and unsafe wastewater disposal methods increased the risk of diarrhoea by factors of 2.73 and 3.06 respectively [41] The unsafe handling and disposal of waste is always associated with contamination of food and water sources and personal contact that can lead to diarrhoea [49]. Households that practised better personal hygiene had fewer cases of diarrhoea [27]. This position is further supported by Fewtrell et al. [45] who reported that hygiene interventions are as effective as other interventions in reducing contamination of hands, food and water that may lead to diarrhoeal illnesses.

Although the studies reviewed for this piece of research work were carried out in different settings (urban and rural) in SSA, they were consistent in providing evidence for the effectiveness of the interventions. This may suggest that these interventions or a combination of these interventions have the potential to reduce diarrhoeal illnesses when applied.

The findings for this review were consistent with results from previous reviews carried out on water, hygiene and sanitation interventions for the reduction of diarrhoea in developed and less developed countries. Reliable results were reported even though there are differences in environmental settings and socio-economic status of participants in the different reviews.

This research focused on health impacts accruable to improved wastewater management practices and the interventions appraised for this review showed various levels of effectiveness in the reduction of diarrhoeal outcomes. In planning community health projects, knowledge of the susceptibility to diarrheal illnesses is vital to providing appropriate and effective schemes for strategic interventions on disease and health that can adequately tackle health determinants in the community [27]. However, it is best to always choose interventions that are appropriate, feasible and cost-effective for any location.

5 Ethical concerns

There were no ethical concerns raised in all the studies under review. There were no reports of harm (both physical and psychological) to the participants. There was no information in any of the studies that the interventions were non-beneficial; breached confidentiality; compulsive; unjust and unfair; and or cases of infidelity or distrust between researchers and participants. The authors and other contributors were all duly acknowledged.

6 Limitations

Studies were selected from peer-reviewed journals in line with evidence-based practice. No unpublished works were included in this review as they have not passed through the peer review process and are generally deemed not to be of good methodological quality. Only accessible studies written in the English language and met the inclusion criteria were included in this review. Time and resources were also limiting factors for this review. However, the evidence provided therein stresses the importance of wastewater management interventions in SSA.

7 Implications for practice

Researchers consider reviews as the best form of evidence for public health practice. Several systematic reviews like Esrey et al. [46] and Fewtrell et al. [45] have given a high level of evidence for the significant role of water, hygiene and sanitation interventions for public health. Interventions such as latrine installation, improved water supply, proper handling and disposal of waste and hygiene education can result in better disease management by increasing prevention and reducing illness.

Case–control studies evaluating the effectiveness of each intervention or combination of sanitation interventions can provide more information and evidence on which interventions to adopt in SSA where resources are scarce. Fewtrell et al. [45] in their review argued that there is also a need for an evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of the diverse hygiene and sanitation interventions to determine the appropriateness for each location. This is particularly useful for SSA where resources are scanty and have so many competing uses. Additionally, discrepancies in the prevalence of between and within communities underscore the need for qualitative studies on the role of socioeconomic status and environmental settings on health outcomes.

7.1 Political implications

Boyle and Drizo [2] argue that the provision the wastewater management facilities may not be a top priority for governments in Africa. Other political issues include the diversion of resources due to corruption and administrative bottlenecks that cause adverse protocols to the implementation of community sanitation projects. Policymakers decide what their priorities are and may not include the provision of waste management facilities as their priorities. However, there is verification that inadequate sanitation causes illnesses due to reduced prevention against risk factors. This may indirectly affect government health budgets and make funds unavailable for other pressing needs, especially in SSA where most hospital visits and child deaths are due to diarrhoea. The prevalence of disease also reduces the productivity of individuals and ultimately the country’s Gross Domestic Product-(GDP). There is therefore need for political strong will and involvement in sanitation interventions to avoid the myriad of problems accruable to inadequate sanitation. Clear government policies and adequate financing are crucial to the implementation and sustenance of good wastewater management programs [13]. Clear policies will help douse tension and anxiety about wastewater management decisions.

7.2 Technical implications

The management of waste is considered both a public and private affair [31]. But in SSA, wastewater management is largely a private affair, especially in rural areas where sanitation services are most scanty. This may be due to so many competing uses for resources including wars and conflicts, food scarcity and other pressing needs. It is common knowledge that individuals in African societies live below the poverty line and may not afford basic household sanitation facilities. The cost of providing the most basic sanitation facilities is very high compared to household incomes in most parts of SSA, requiring unaffordable technical and financial resources [29]. A Gallup poll showed that the pit latrine is the most basic form of sanitation facility used by most Africans (16%) while 4% of all Africans do not have any toilet facilities. Lessons can be drawn from the 1983 Rural Sanitation Pilot Project-(RSPP) by the government of Lesotho aimed at promoting the construction of Ventilated Improved Pit (VIP) latrines through a decentralized sanitation strategy to help poor inhabitants of rural communities reported by Daniels et al. [39]. This programme was financially supported by the World Bank; United States Agency for International Development-(USAID); the United Nations Development Programme- (UNDP) and the United Nations Children’s Fund-(UNICEF). This is an example of a successful project that can be emulated by other communities in SSA to fill the funding gap in disadvantaged communities.

Nevertheless, the pit latrine may not be the best form of sanitation disposal of human excreta. In more privileged locations, flush toilets and sewage systems are developed through both public and private arrangements. Hand washing detergents and driers could also be provided in public toilet facilities although power shortages in SSA may limit the feasibility of electronic hand driers. Paper tissue could at least be provided to reduce contamination of hands and transmission of pathogens that could cause disease.

People may not be able to provide the technologies and technical expertise required for the treatment of wastewater they generate [2]. Safety is another issue for the use of latrines especially those constructed with local materials [29]. The wooden slap might be broken or rotten and or unstable soil conditions cause a risk of collapse and discourage use. It is important to provide the necessary affordable and reliable technologies appropriate for each location to put into practice only those interventions that are effective. Proper logistics and good town planning are required for allocative efficiencies, particularly for unplanned settlements in SSA.

7.3 Socio-economic implications

Poverty, negligence, ignorance and socio-economic status and settings are factors affecting the proper disposal and handling of wastewater management in SSA. Daniels et al. [39], back the fact that parents’ employment status and levels of education are factors directly linked to the availability of sanitation facilities and hence the incidence of disease. Hence, there is for establishment of education schemes like adult literacy classes both in the formal and informal settings and stimulation of local economies to improve the standards of living so that individuals can take personal responsibility for their health through the provision of their sanitation facilities.

According to Massoud et al. [13] there is a further need to create and encourage community participation for effective sanitation programs to change negative attitudes towards. However, some Africans still consider their contribution to the provision of sanitation services as a high price to pay; they cannot comprehend living in mud houses and using concrete to build latrines thereby undermining the need for pit latrines [29]. Studies by Esrey et al. [46] and Fewtrell et al. [45] support the vital role of hygiene education for the improvement of personal and community hygiene. Yongsi [27] also reported that discrepancies in socio-economic settings and status affect the prevalence of diarrhoeal illnesses. This may be because urban areas are normally planned and have access to drainages, sewage systems and other facilities lacking in rural areas. More efforts are needed to reduce inequalities within and between African societies.

7.4 Cultural implications

There is a need to confront some ritualised cultural practices in SSA that resist the use of sanitation facilities and encourage public defecation [29]. In some communities in Burkina Faso, it is seen as shameful to go in the direction of a toilet to relieve oneself, especially by close relatives and toilet facilities are regarded as exclusively for the rich and should not be used by the poor. The smell of human excreta discourages the use of lavatories in some Igbo communities in Nigeria and the Nwahu region of North Ghana. Some Africans resist the use of latrines for fear of being possessed by evil spirits or losing their magical powers or view open defecation as an ancestral practice that must not be abandoned. These cultural practices have been recalcitrant and have major implications for good public health practices. Dittmer [29] proposes a social convention involving a moral contract that encourages and reinforces certain agreed good practices in the community to aid public hygiene. Defectors of these set norms like those engaged in public defecation could be subjected to public embarrassment. Moreover, there is a need for health education and promotion strategies to reverse negative trends and attitudes and bring about a general paradigm shift towards hygiene practices in SSA.

8 Recommendations

This review illustrates that wastewater management interventions help reduce the prevalence of diarrhoea in individuals and communities in SSA. There is, therefore, a need for particular attention to these interventions to meet the MDG goal-7 (MDG-7) target given to the developing countries of halving the proportion of people without access to sustainable safe drinking water and basic sanitation and to reduce by two-thirds all child deaths by 2015. All the UN member countries have agreed to meet this deadline. The global commitment to attain this MDG goal provided a tremendous opportunity to improve health and quality of life through the implementation of suitable interventions.

However, so many areas of concern need more attention like the role of sanitation in curbing diarrhoeal outcomes and the durability of the health-related benefits of these individual interventions [45]. Other areas that need attention include the need to include older members of populations to improve the reliability and generalizability of studies; more information is similarly needed on the study conditions and the specific pathogens responsible for reported episodes of diarrhoea. Recommendations to improve wastewater practices in SSA should include:

-

Raising awareness of the extent of wastewater management issues and the problems they constitute.

-

Encouraging local authorities to be more involved in wastewater management.

-

Raising awareness of local populations, community leaders and policymakers about the health and environmental implications of improper wastewater management and disposal practices through health education and promotion interventions.

-

Developing the necessary social infrastructure necessary to aid wastewater management.

-

Persuading the government to commit to taking greater roles in wastewater management.

-

Developing funding programs to provide household sanitation facilities in deprived communities.

-

Additional research in the field is imperative to enhance and contemporize existing studies.

9 Conclusion

Evidence on the positive impact of effective wastewater management in SSA although scarce was justified in this review. There was a positive impact on the reduction of diarrhoeal illnesses from all interventions assessed in this review. A major observed weakness in the generalization of this research is the use of only children U5 as subjects in most of the studies.

Diarrhoea is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in SSA and is responsible for about 20% of all child deaths [50]. Diarrhoeal illnesses are also responsible for about 50% of all admissions to the hospital with profound effects on victims, their families and society [33] and about 50% of the population in developing countries do not have access to wastewater sanitation [2]. The high prevalence of diarrheal illnesses in SSA amid inadequate sanitation underscores the need for better preventive interventions against diarrhoeal episodes. Therefore, the skilful implementation of effective wastewater management strategies as well as the recommendations given in this review and broad stakeholder participation would provide the needed prevention against diarrhoeal outcomes. However, the strategies chosen should be suitable, feasible and economical for each location and population.

Data and materials

All data generated and or analysed and materials used for this review are duly acknowledged in this article.

References

Clark G. The effects of old landfill sites on Vermont’s water resources. HCOL196: Sustainable Water Management. 2010;39.

Boyle J. Drizo A. Wastewater Treatment in Africa. HCOL196: Sustainable Water Management. 2010;97.

Chirisa I, Bandauko E, Matamanda A, et al. Decentralized domestic wastewater systems in developing countries: the case study of Harare (Zimbabwe). Appl Water Sci. 2017;7:1069–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-016-0377-4.

Norman G, Pedley S, Takkouche B. Effects of sewerage on diarrhoea and enteric infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(8):536–44.

Samie A, Obi CL, Igumbor JO, Momba MNB. Focus on 14 sewage treatment plants in the Mpumalanga Province, South Africa to gauge the efficiency of wastewater treatment. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8(14):3276–85.

Bohdziewicz J, Sroka E. Application of hybrid systems to the treatment of meat industry wastewater. Desalination. 2006;198(1–3):33–40.

Egun NK. Effect of channelling wastewater into water bodies: a case study of the Orogodo river in Agbor, delta state. J Hum Ecol. 2010;31(1):47–52.

Rim-Rukeh A. Environmental science: an introduction. Kraft Books, Ibadan. 2009. https://www.scirp.org/(S(lz5mqp453edsnp55rrgjct55))/reference. Accessed 18 Feb 2020.

Melloul AA, Hassani L. Salmonella infection in children from the wastewater spreading zone of Marrakesh city (Morocco). J Appl Microbiol. 1999;87(4):536–9.

Trang DT, Hien BTT, Molbak K, Cam PD, Dalsgaard A. Epidemiology and aetiology of diarrhoeal diseases in adults engaged in wastewater-fed agriculture and aquaculture in Hanoi. Vietnam Tropical Med Int Health. 2007;12:23–33.

Keraita B, Jiménez B, Drechsel P. Extent and implications of agricultural reuse of untreated, partly treated and diluted wastewater in developing countries. CAB Rev Perspect Agric Vet Sci Nutr Nat Resour. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20083058.

WHO, 2011. WHO (World Health Organization). United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, 2011. The Guidelines on Decentalised Wastewater Management for Sustainable Infrastructure Development in Small Urban Areas. Thailand: United Nations.

Massoud MA, Tarhini A, Nasr JA. Decentralized approaches to wastewater treatment and management: applicability in developing countries. J Environ Manage. 2009;90(1):652–9.

Blumenthal UJ, Mara DD, Peasey A, Riuz-Palacious G, Stott R. Guidelines for the microbiological quality of treated wastewater used in agriculture: recommendations for revising WHO guidelines. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1104–16.

WHO/DFID (Department for International Development), 2011. Millenium Development Goal Seven. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

UN WWAP, 2003. (UN WWAP-United Nations Waste Water Assessment Programme). Pacific Institute 2010. Water quality facts and statistics. http://www.pacinst.org/. Accessed 19 Feb 2020].

Drechsel P, Keraita P, Amoah P, Abaido RC, Raschid-Sally L, Bahri A. Reducing health risks from wastewater use in urban and peri-urban sub-Saharan Africa: applying the 2006 WHO Guidelines. Water Sci Technol. 2008;57(9):1461–6.

Ho G. Small water and wastewater systems: pathways to sustainable development? Water Sci Technol. 2003;48(11–12):7–14.

WHO, UNICEF. Report of the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme on Water Supply and Sanitation. New York, Geneva: United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization; 2008.

CNES. CNES-(Citizen Network on Essential Services) approaches to sanitation services. Water Policy Series A Water Domestic Policy Issues. 2003;A5(2003):12.

Scott C, Faruqui NI, Raschid L. 2004. Wastewater use in irrigated agriculture. Confronting the livelihood and environmental realities. http://www.idrc.ca/en/ev-31595-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html. Accessed 16 Feb 2020.

Paraskevas PA, Giokas DL, Lekkas TD. Wastewater management in coastal urban areas: the case of Greece. Water Sci Technol. 2002;46(8):177–86.

Wilderer PA, Schreff D. Decentralized and centralized wastewater management: a challenge for technology developers. Water Sci Technol. 2000;41(1):1–8.

USEPA, 2005. USEPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Handbook for Managing Onsite and Clustered (Decentralized) Wastewater Treatment Systems, EPA/832-B-05-001. Office of Water, Washington, DC. 2005;66.

Tchobanoglous G, Crites R. Wastewater engineering (Treatment Disposal Reuse) Metcalf Eddy, Inc. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

Hall D, Lobina E. 2008. Sewerage works: public investment in sewers saves lives. Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU). London.

Yongsi HBN. Wastewater disposal practices: an ecological risk factor for health in young children in Sub-Saharan African cities (case study of Yaoundé in Cameroon). Res J Med Med Sci. 2009;4(1):26–41.

WHO. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Water Supply and Sanitation Assessment, Global Water Supply and Sanitation Assessment. 2000.

Dittmer A. 2009. Towards total sanitation socio-cultural barriers and triggers to total sanitation in West Africa. http://www.wsscc.org. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Cairncross S, Neill DO, McCoy A, Sethi D. Health, environment and the burden of disease: a guidance note. London: Department for International Development; 2003.

Drechsel P, Kunze D. Waste composting for urban and peri-urban agriculture: closing the rural-urban nutrient cycle in sub-Saharan Africa. Wallingford: CABI; 2001.

Lewis MA, Miller TR. Public-private partnership in water supply and sanitation in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Policy Plan. 1987;2(1):70–9.

Pegram G, Rollins N, Espey Q. Estimating the costs of diarrhoea and epidemic dysentery in KwaZulu-Natal and South Africa. Water Sa-Pretoria. 1998;24:11–20.

GNU. National sanitation policy: draft white paper on sanitation. National sanitation task team. 1995. http://www.info.gov.za/whitepapers/1995/sanitation.htm. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine: what is it and what it isn’t? BMJ. 2000;32(7):1–72.

Cesar GV, Jean-Pierre H, Bryce J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):400–6.

Rychetnik L, Hawe P, Waters E, Barratt A, Frommer M. A glossary for evidence-based public health. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2004;2004(58):538–45.

Glanville J. "Stage 11. Conducting the review. Phase 3: identification of research." 2001. www.cochrane.org. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

Daniels DL, Cousens SN, Makoae LN, Feachem RG. A case-control study of the impact of improved sanitation on diarrhoea morbidity in Lesotho. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;1990(68):455–63.

Young B, Briscoe J. A case-control study of the effect of environmental sanitation on diarrhoea morbidity in Malawi. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1987;1987(42):83–8.

Tumwine JK, Thompson J, Katua-Katua M, Mujwajuzi M, Johnstone N, Wood E, Porras I. Diarrhoea and effects of different water sources, sanitation and hygiene behaviour in East Africa. Tropical Med Int Health. 2002;7(9):750–6.

Haggerty PA, Manunebo MN, Ashworth A, Muladi K, Kirkwood BR. Methodological approaches in a baseline study of diarrhoeal morbidity in weaning-age children in rural Zaire. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;1994(23):1040–9.

Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The magnitude of the global burden of diarrhoeal disease from studies published 1992–2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;2003(81):197–204.

Blum D, Faechem RG. Measuring the impact of water supply and sanitation investments on diarrhoeal diseases: problems of methodology. Int J Epidemiol. 1983;12:357–65.

Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM Jr. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(1):42–52.

Esrey SA, Potash JB, Roberts L, Shiff C. Effects of improved water supply and sanitation on Ascaris, diarrhoea, dracunculiasis, hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Bull World Health Organ. 1991;69(5):609–21.

Curtis V, Cairncross S. Effect of washing hands with soap on diarrhoea risk in the community: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;2003(3):275–81.

Faechem RG, Bradley DJ, Garelick H, Mara DD. Sanitation and Disease. Health aspects of excreta and wastewater management. Chichester. New York: John Wiley; 1983.

Prescott LM, Harley JP, Klein DA. Microbiology. 5eds ed. New York: McGraw Hill Higher Education; 2009.

Dlamini M, Nkambule S, Grimason A. First report of cryptosporidiosis in paediatric patients in Swaziland. Int J Environ Health Res. 2005;15(5):393–6.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health, Education, Medicine and Social Care, Anglia Ruskin University, Chelmsford where this work was initially submitted; and to the Department of Environmental Management, Faculty of Earth and Environmental Science, Bayero University, Kano for further reviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to this research paper immensely. The first draft of the work was written by Gujiba, U. K. during his M.Sc. study at Anglia Ruskin University, Chelmsford, UK. Ali, A. F. structured the article, updated and revised the contents and made it publishable in Discover Water.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable to this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, A.F., Gujiba, U.K. Household wastewater management in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Discov Water 4, 6 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-024-00060-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-024-00060-6