Abstract

In rural Ivorian communities, women are considered as the guardians of water, undertaking an essential role deeply rooted in local cultural values, ensuring the preservation and management of this vital resource. However, the scarcity of potable water places them under significant pressure, exposing them to heightened risks. Within this context, this study conducted in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé explores the critical link between the cultural values of Bete women and the issue of access to potable water in the region, with a specific focus on the impacts they experience. To achieve this, the study adopts a primarily qualitative approach based on documentary research, direct observations, in-depth semi-structured interviews, and focus groups. The findings reveal that the scarcity of potable water disproportionately affects women in these communities, leading to significant socio-economic consequences. Water points often become scenes of verbal and physical aggression among women, given the difficulties in accessing water in the area, thereby limiting their daily activities and economic participation. Furthermore, they face heightened health risks due to water supply hardships and the consumption of non-potable water from unimproved sources. Additionally, this study offers novel perspectives for transformative actions aimed at addressing the scarcity of potable water, promoting women's social and cultural values, and preserving the essential cultural ties within the Bete communities of Gboguhé and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The issue of access to clean water has been at the center of significant social and environmental debates for over half a century [1]. Ensuring access to clean water is vital to meet human needs while minimizing health risks for populations [2, 3]. The international community recognizes its importance due to its intersectionality with other concepts, notably gender. Water, an essential resource for life, plays a pivotal role in achieving gender equality and empowering women. In the African context, men and women do not have equal access to water resources, leading to different impacts [4]. In this context, the literature review offers a diverse body of work on the repercussions of the shortage of potable water for women, notably concerning the unequal workload. Indeed, water scarcity leads to a disproportionate burden of labour for women, particularly in rural societies where women are frequently tasked with water collection. This situation compels them to undertake arduous and time-consuming chores, thus constraining their economic prospects [5]. Many women, along with their daughters, endure long and daily journeys to fetch water, with minimal involvement from men [6]. An analysis of the time-budget relationship in water supply during scarcity concludes that this task is burdensome and affects women's activities [7]. On a health level, limited access to clean water exposes women to health risks, including waterborne diseases, placing them at the forefront as caregivers in many societies [8]. On an educational front, research by Woldemicael has demonstrated how water scarcity can hinder girls' education. She identified that girls are often tasked with water collection, which can hinder their attendance at school and thus jeopardize their future prospects [9]. The shortage of clean water also impacts the economic empowerment of women. They invest a significant amount of time in water collection, leaving them with less time to engage in income-generating activities, thereby limiting their economic opportunities and financial independence [10]. Moreover, burdened by water-related challenges, women have less time and energy to dedicate to decision-making and community participation [11]

Côte d'Ivoire, like many developing countries, has sought to improve access to clean water for its citizens through the development of policies such as the National Development Plan (PND), the National Water Strategy (SNE), and the Government's Social Program (PS-Gouv). These initiatives emphasize goals of universal access to clean water. However, their implementation varies by region. In the Haut-Sassandra region, women are tasked with water collection, exposing them to risks and limiting their opportunities.

To understand these gendered impacts of drinking water scarcity, it is crucial to explore the social and cultural values of women in rural African settings. These values, deeply rooted in their society's norms, traditions, and beliefs, shape their roles, responsibilities, and positions within the community. Anthropologists Amadiume and Caplan highlight the significance of African women as "economic pillars of rural societies, making significant contributions to food production and local economic development" [12]. Their economic role is often intertwined with subsistence agriculture, livestock rearing, and other vital economic activities. Women are often perceived as guardians of tradition, responsible for transmitting cultural knowledge to future generations. Anthropologist Jane Guyer's work emphasizes this cultural role of women in Africa [13]. Their role as custodians and transmitters of culture reinforces their status and position within their community.

In rural African settings, women play a central role in the social and cultural fabric of their communities. Their economic contributions, involvement in sustainable development, and fight for empowerment are key elements that influence their daily lives and positioning within society. Okojie highlights the crucial role of women in rural development, emphasizing their contribution to agriculture, the local economy, and environmental sustainability [14]. Their knowledge and skills are essential for ensuring food security and effective management of limited resources.

Similarly, Azad and Pritchard have demonstrated that women play a crucial role in strengthening the adaptive capacity of rural households in the face of natural disasters [15]. While often burdened by disasters, they are at the forefront of adaptation, developing capacities for disaster response and recovery. In a study on post-flood reconstruction in Assam, India, Krishnan observed their frontline roles, actively rebuilding their homes, lives, and livelihoods with little to no external agency assistance [16]. Other studies have documented how women enhance community resilience in disasters [15, 17,18,19].

Goheen and Hayes highlight the potential of women as agents of change in promoting sustainable agricultural practices and rural development [20]. Their traditional knowledge and practices preserve natural resources and contribute to food security. In the context of water supply and management in rural areas, an often overlooked yet essential aspect is the role of women. The literature emphasizes the importance of women in these domains, highlighting their crucial contribution to water collection, storage, distribution, and preservation [21,22,23]. Women in rural areas have an in-depth understanding of their environment and local water resources. Their expertise in preserving water sources, managing irrigation systems, and conserving ecosystems contributes to the sustainability of water resources [24]. Therefore, Zwarteveen and Meinzen-Dick underscore the importance of strengthening women's rights to water and water resource management, as well as their active participation in decision-making processes [25].

Considering all of these studies, it is clear that women play a crucial role in water supply and management in rural areas. Their traditional knowledge, practices, and expertise contribute to preserving water resources and ensuring the food security of communities. However, the social and cultural reality of women in rural African settings is not devoid of challenges. Mies highlights the role of social and cultural division of labor and patriarchy, which marginalize and exploit women in the inequitable global economic structures [26]. Women in rural African settings often face obstacles such as limited access to land, credit, and training opportunities. Consequently, they encounter persistent gender inequalities that hinder their autonomy and equal participation in society.

Similarly to several rural areas in Africa, Bété women in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé play a crucial role in the domestic water supply chain. However, it is evident that the localities in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé are facing situations of drinking water scarcity, hindering the well-being of women in carrying out their daily tasks.

Indeed, while numerous studies have focused on the technical aspects of water scarcity and on cultural aspects and gender roles separately, few have explored the complex links between these notions in rural contexts. Therefore, this contribution examines the crucial link between the cultural values of Bété women and the issue of access to clean water in the region, emphasizing the impacts they experience. To achieve this, the study adopts an essentially qualitative approach, utilizing methods such as documentary research, direct observation, individual semi-structured interviews, and focus groups. By identifying how beliefs and social norms influence water-related behaviors among Bété women, this research offers new perspectives to develop more inclusive and contextually relevant approaches to address the scarcity of potable water.

2 Methodology of the study

2.1 Study area

The study was conducted in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé, located in the Central-West of Côte d'Ivoire, within the Haut-Sassandra region, specifically in the Daloa Department. According to the latest General Population and Housing Census (RGPH), the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé has approximately 69,020 inhabitants spread across 36 villages [27]. Similar to the Haut-Sassandra region, the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé faces recurrent issues with access to clean water. Hand pumps constitute the predominant sources of drinking water in the villages. In 2019, a survey conducted by the Ivorian Water Distribution Company (SODECI) as part of the national program for access to clean water by the Ivorian government (PS-GouvFootnote 1) revealed the existence of 40 hand pumps throughout the territory of the Sub-Prefecture. Only 5 villages in the Sub-Prefecture are supplied by an Improved Village Hydraulics (IVH) system. Furthermore, this survey revealed that out of the 40 hand pumps in the Sub-Prefecture, only 14 were in good condition, indicating an estimated breakdown rate of 65%. These data were confirmed by a survey conducted by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) as part of the second phase of the Central and Northern Côte d'Ivoire Project (PCN-CI 2Footnote 2). Based on these data, the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé appeared to be a potentially exposed area to situations of water scarcity. Thus, for representational purposes, the following criteria were selected to determine the localities to be surveyed:

-

Geographic location: The selected localities belong to the same area of interest, namely the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé.

-

Cultural affiliation: The chosen localities belong to the same Bété ethnocultural group. This allows for a rational explanation of the research object by establishing a connection with the underlying culture.

-

Types and number of water facilities: Emphasis was placed solely on localities where there is at least one functional hand-pump water facility.

-

Population size: The selected localities have a population of at least 1000 inhabitants, allowing for the measurement of the extent of the phenomenon.

After applying these criteria, five villages within the aforementioned Sub-Prefecture were selected for the investigation. These villages include Gboguhé, Gbiéguhé, Zobéa, Koréa 2, and Kékégoza (see Fig. 1).

To confirm the situation of access to drinking water in these localities, a comparative analysis was conducted with the existing standards for water supply in Côte d'Ivoire, as presented in Table 1 below.

The analysis of these criteria within the context of the study's localities revealed that these different communities are facing situations of drinking water scarcity, which can be attributed to the mismatch between the water demand expressed by the local population's size and the existing water infrastructure, as depicted in Table 2 below.

2.2 Composition of resource persons

The study was conducted with informants selected using the purposive sampling technique. This sampling method is used when a sampling frame does not exist, and it is difficult or even impossible to establish the probability of selecting elements for the sample. Therefore, following N'Da, our resource persons were chosen based on their knowledge and experiences, which could provide valid and comprehensive data relevant to our study [28]. Two types of actors were selected:

-

Village chiefs: These individuals play a crucial role in the local culture. They ensure strict adherence to the community's cultural precepts and promote practices aligned with tradition. The village chief also holds the customary position responsible for the administrative management and proper functioning of the village. Often elderly, experienced, and considered wise, their roles include upholding traditional norms and values and consolidating peace within their locality.

-

Women: The selection of women is due to their unanimous recognition in Bété tradition as the primary actors in water supply and sanitation within the villages.

2.3 Study approach

In its implementation, this study adopts an essentially qualitative approach to gain a deeper understanding of the cultural values of Bété women and their connection to the issue of access to drinking water. The qualitative approach allows for an in-depth exploration of beliefs, social norms, and behaviors related to water within the studied community.

2.4 Data collection strategies

2.4.1 Documentary research

In-depth documentary research was conducted to gather literature, reports, and existing studies on water scarcity, cultural values, and the roles of women in rural areas. This facilitated a better understanding of the historical background and context of this study.

2.4.2 Semi-structured interviews

Five in-depth semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with the village chiefs of the five targeted villages. The aim in this context was to focus the discourse of the interviewees around predefined themes. During these exchanges, the interviewees expressed their views on the role of women in Bété traditional society, the local water resource management system, and the challenges related to water supply for women. These thematic areas were outlined in an interview guide to steer the discussions. However, it's worth noting that the interviews varied in terms of freedom of expression and the respondent's level of involvement, with an average duration ranging from 45 to 60 min. The quality of responses was therefore influenced by our goal of obtaining as much information as possible.

2.4.3 Focus groups

In addition to the individual semi-structured interviews, five focus groups were conducted, one per village, involving a total of fifty women belonging to different village associations (Table 3).

The use of focus groups as a qualitative data collection technique is well-suited for analyzing interactions between gender and natural resource governance [15]. This method has been increasingly employed by researchers in qualitative research to identify household and community recovery processes and analyze their experiences [29, 30].

Qualitative research methods mainly lead to the generation of rich data [31, 32]. Thus, the focus group is a popular and relevant qualitative tool due to its convenience, cost-effectiveness, high face validity, and quick results [33, 34]. Additionally, this makes the method suitable for our study on the challenges of water supply for women, providing a relevant insight into their experiences and the context surrounding the resource [35, 36].

The choice of this data collection technique aligned with the local context requirements. Our observations revealed that in the presence of men, women found it challenging to express themselves freely and appeared to be influenced by them. In contrast, more enthusiasm and freedom were observed among women when they gathered among themselves during association meetings. Using this technique aimed to obtain information about the expectations, opinions, attitudes, perceptions, and resistances of women regarding their water supply experiences. It also allowed capturing shared meanings and disagreements through the consideration of social interactions that manifest [37]. On average, focus groups lasted between 1 and 1 h 30 min.

2.4.4 Direct observations

Direct observations were conducted at water points to observe the behavior of women during water supply for their households and the quality of the sources used. This technique allowed for a direct understanding of their roles and practices in water management.

2.5 Data analysis

The audio data was transcribed, sorted, coded, and thematized using thematic content analysis to identify meaningful units in the actors' discourse. The data was initially analyzed from a comprehensive perspective to understand the meaning of the actors' viewpoints and reconstruct a rational explanation of their perspectives. Subsequently, the data was examined from the systemic approach of the rural water supply framework to identify the links between women and water in these localities.

2.6 Ethical consideration of the research

Ethical principles were rigorously observed, including informed consent, anonymity, and confidentiality. In presenting the results, the use of initials for the names of participants was preferred to preserve the identity of the key informants.

3 Results

3.1 Women and water in Bété culture

3.1.1 Sociocultural values of women

The study of sociocultural values of women in Bété culture helps to grasp the significance of this relationship in shaping female identity, social cohesion, and ecological balance within the community. In Bété culture, several indicators shed light on the values of women. Women play an educational role and contribute to knowledge transmission. They are entrusted with passing down knowledge, traditions, and cultural values to future generations. They fulfill a crucial educational role by teaching children’s practical skills, cultural practices, and societal norms within Bété society. In this context, particular emphasis was placed on the education of young women to understand the role of women in Bété society.

The education of young girls in Bété tradition primarily revolves around household management and conduct. From a young age, girls are initiated by their mothers into cooking and maintaining proper hygiene in the household. They learn specific recipes, hygiene practices, and feminine principles such as waking up early to maintain household cleanliness, fetching water, and understanding feminine hygiene rules. The position of women as household managers in Bété society stems from this learning context. They are responsible for household upkeep, childcare, water fetching, meal preparation, and ensuring children's education:

At home, all aspects of household management are handled by women. It is true that we say the man is the head of the family, and he makes decisions and ensures the family's protection and well-being. However, when it comes to taking care of the children and all other household activities, it is solely the responsibility of women. That's how they have been raised. B.K.A (Field Survey, 2022).

In Bété culture, women are highly valued for their economic contribution, particularly in the field of agriculture, where they play a vital role in food production and local economic development. Their expertise in agricultural practices, especially in subsistence farming, helps ensure the community's food security. Additionally, women are actively engaged in commercial activities, providing financial support to their households. In the villages of Gboguhé, Gbiéguhé, Koréa 2, Kékégoza, and Zobéa, it is not uncommon to see women involved in various commercial ventures, with a focus on the food service sector.

Furthermore, women are also associated with symbols of power and authority for men in Bété culture. Women are considered a form of wealth and are seen as a sign of maturity and responsibility for men. Having a wife is among the criteria for holding certain positions of responsibility within the local traditional organization:

In the village, there are certain positions of responsibility that cannot be given to someone who is not married. For instance, to become a village chief or a village treasurer, one must have a wife. These various positions of responsibility require the person to be honest and responsible. Therefore, in our view, having a wife signifies responsibility and indicates that the person is unlikely to behave improperly. T.S.H (Field Survey, 2022).

These various indicators highlight the significance of women in preserving the culture, social cohesion, and balance within the Bété community. They underscore their central role as keepers of knowledge and sociocultural values. Additionally, women play a crucial role in water management in rural areas.

3.1.2 Roles and responsibilities of women in water management

The participation of women in water management reflects deeply rooted sociocultural values within the Bété community. Their involvement in these activities is often seen as an indicator of their central role in preserving social order and community cohesion. In Bété culture, water is perceived as a vital and sacred resource, embodying complex symbolic meanings. Women, as custodians of life and fertility, are closely associated with this precious resource. Their active involvement in water collection, storage, distribution, and preservation is considered a manifestation of their maternal, nurturing, and protective role. Women possess valuable knowledge and specific skills in water resource management, passed down through generations. The social and cultural division of tasks designates them as responsible for water collection:

In our Bété culture, a married man is not allowed to fetch water. If he is married and goes to fetch water, people will mock him. It is an activity dedicated to women. Even myself, I have never carried a bucket to fetch water from the pump. I cannot do it. It is not my role. D.P (Field survey, 2022).

This verbatim provides insight into how the local culture defines social roles based on gender. Water supply is part of women's daily activities and contributes to their social integration and acceptance. They must go to ponds, pumps, or wells to ensure daily water supply. In this division of tasks, women are also responsible for managing the sanitation of the household and its members. Water plays a significant role in this task; hence, according to local custom, a woman who lacks water and firewood is considered a bad wife on the pretext that she does not take care of her husband, children, and her husband's guests. Therefore, water should be available for cooking, drinking, bathing, and washing dishes. This explains why women are engaged daily in the task of water supply, for which they have developed expertise in selecting reliable water sources, assessing water quality, and managing the necessary quantities to meet household needs.

In addition to collection, women also play a crucial role in water storage. They use specific and varied containers and appropriate conservation techniques to ensure a constant water supply for household needs, even during periods of drought or scarcity. The distribution of water is also a significant responsibility of women in Bété society. They ensure that every household member has access to a sufficient amount of water for their daily needs. Consequently, they apply forms of rationing water usage and its users to ensure equitable allocation of the resource.

3.1.3 Water supply practices of women in the Gboguhé Sub-Prefecture

3.1.3.1 Sources of water supply

Various sources of water supply are used by women in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé to meet their water needs. Three main types can be distinguished: ponds, traditional wells, and wells equipped with a Pump. Analyzing the history of water supply methods within the Bété communities allows for the classification of water sources utilized by women in their cultural tasks. Table 4 below provides a classification of available water sources in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé.

Ponds serve as traditional water sources for the Bété community and play a fundamental role in their livelihood. Over time, ponds have gradually been abandoned by women in favor of modern water sources like the pumps. Several factors have contributed to this progressive abandonment, including the promotion of improved water sources and episodes of drought that threatened the sustainability of ponds. The following verbatim, taken from an interview with a village chief, illustrates this analysis:

Back in the 1960s, 65 s, and 70 s, droughts were a significant challenge for us. All the ponds dried up. So, we had to wake up at 5 a.m. just to get a basin of water. Because, we did not allow any woman to have 2 or 3 basins at the pond. At least one basin was required so that all the women could be served. We experienced this situation several times here. But when we got the pump in 1980, the situation changed. The women were relieved. We no longer faced the same situation at that time. Additionally, there were many wells. There were about 3 wells. There was Zaïha, Nigué, and Kopé. So, the women fetched water from there, but not with the same effort as with the pump, you know. I.Z.J (Field survey, 2022).

3.1.3.2 Water collection and transportation strategies

In the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé, women have developed ingenious strategies for water collection and transportation. These strategies, adapted to the specific conditions of their environment, are the result of local knowledge related to a deep understanding of their territory, seasons, and available water resources. Water collection is a daily task for Bété women. In the past, they used traditional clay containers called "Kounaka Laki," which were well-suited for carrying water without wasting it. These containers were carefully designed to be lightweight and manageable, allowing women to carry them on their heads or shoulders with ease. Nowadays, these traditional containers have given way to modern tools used for water transportation (Fig. 2).

These modern containers are considered durable and easy to handle during transportation. Besides water transportation, these modern containers are also used for water storage. Water storage is an integral part of the water supply process and is intended to ensure the water security of the household in terms of both quantity and quality. It not only covers the daily needs of household members but also preserves as much water as possible, thereby safeguarding against water scarcity concerns. While the water transportation containers may also be used for storage, separate containers solely dedicated to water storage are distinguished (Fig. 3).

These different containers are characterized by their large storage capacities, ranging from 200 to 250 L, allowing for the conservation of larger quantities of water. Bété women are also skilled in the art of carrying water over long distances. They use specific techniques to balance and stabilize the containers on their heads while walking with grace and balance. This ancestral practice has been passed down through generations and is an integral part of their cultural identity. It is worth noting that water collection and transportation are not merely practical activities for Bété women; they also hold community and cultural significance. On a community level, during their journey to the water source, women meet, exchange news, share advice, and strengthen solidarity within the community. This social dimension reinforces the importance of water management as a central element of the daily lives of Bété women:

Here, not everything can be said in front of one's husband. So, it's at the marigot or the pump where we can meet and talk among women. It's easier for us to gather at these places to chat and tease each other a bit. This is what motivates us to go and fetch water. Otherwise, when you're at home, you're occupied with your chores, and you don't have the time to see your friends and catch up. Z.L.Y (Focus group Koréa 1, 2022).

At the cultural level, this framework serves as a means of knowledge transmission to future generations. During the water collection hours, several women are accompanied and assisted by their children. Typically, children aged 12 and above are most often called upon when women are unavailable for water collection or when they need to fill a large number of containers. This activity provides a learning environment for the children and is deeply rooted in cultural values. Involving children in water collection does not distinguish between genders; both girls and boys are called upon to help. Girls use buckets to carry water just like their mothers, while boys use jerry cans that they transport on bicycles or on their heads.

Furthermore, rural Bété women have developed effective strategies for water collection and transportation that are well-suited to their environment. Their knowledge of the territory, skills, and adaptability are crucial in meeting the water needs of their community. However, despite their expertise and abilities, Bété women in the Gboguhé Sub-Prefecture face challenges related to water access. The scarcity of clean water caused by insufficient or unavailable Human-Powered Water Pumps (PMH) leads women to adopt strategies that increase the difficulty of their cultural water supply tasks and have an impact on their well-being.

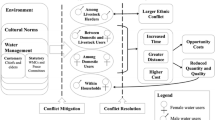

3.2 Impact of water scarcity on women

The observed inadequacies in the availability of clean water in the villages of Gboguhé Sub-Prefecture affect all social strata of this community, but not equally. Women are particularly impacted by the constraints of water scarcity as they are the primary actors in the water supply chain in Bété culture. These constraints mainly manifest at the social and sanitary levels.

3.2.1 Social impacts of water scarcity

3.2.1.1 Water use conflicts

In Gboguhé Sub-Prefecture, women are often confronted with water-related conflicts within their community. Due to the essential nature of water and its central role in daily life, tensions and disagreements frequently arise over its access and management. The limited availability of hand pump-operated wells leads to competitions among women to obtain a sufficient share of water. In the villages of Gboguhé, Gbiéguhé, Kékégoza, Koréa 2, and Zobéa, not all women have the option to turn to the traditional ponds and wells where the pressure is lower. While most women prefer these water sources to avoid long queues at the pump, others remain loyal to the village pump. During the pump's opening hours, impatience and the desire to fill a large number of containers often lead to misunderstandings among women.

Although rules are established by the water pump operators to prioritize based on arrival order, tensions among women on this matter are not uncommon. This can result in verbal and physical aggression among the women. Those who frequent the traditional ponds and wells in the lowlands seek to avoid this situation, as the time they must spend at the pump to obtain water depends on the quantity of containers they have and their position in the queue. According to them, they can save time by resorting to other water sources, as expressed in the following testimony:

At the pump, one person can have 08 or even 09 containers to fill. Imagine if you have to wait for them to fill all these containers, you will waste time, and that's what leads to disputes. I prefer to go to the traditional pond to finish quickly and avoid getting into arguments. S.G.O (Field Survey, 2022).

It is evident that access to water during periods of scarcity can lead to social problems. In the communities of Gboguhé, Gbiéguhé, Kékégoza, Koréa 2, and Zobéa, conflicts over water usage depend on the availability and functioning of water infrastructure and how it is managed. These conflicts can jeopardize social cohesion and solidarity within the community.

3.2.1.2 Impacts of water scarcity on the education of young girls

The impact of water scarcity on children's education, especially girls, is a major concern. Women, as guardians of water in many communities, often spend hours collecting this essential resource. This reality has direct repercussions on children as their mothers are inevitably less available to care for them and support their education.

Firstly, children, especially girls, may be deprived of a quality education due to their mothers' absence at home. Women dedicate a considerable amount of time to water collection, which means they are absent from home for extended periods each day. In their absence, children may lack supervision and encouragement to pursue their studies. This can result in reduced school attendance and poor academic performance.

Furthermore, children, especially girls, may be compelled to follow in their mothers' footsteps regarding water collection. Instead of going to school, they are sometimes sent to fetch water to relieve their overburdened mothers. This gender-based division of roles perpetuates the cycle of water scarcity and lack of education. Young girls can thus be trapped in a pattern where their future prospects are limited by the same constraints that affected their mothers.

Ultimately, the impact of water scarcity on children's education, particularly girls, can have long-term repercussions on society as a whole. Quality education is an essential pillar of individual and community development, and when this opportunity is hindered, the consequences can be devastating.

3.3 Economic impacts of water scarcity on women: a constraint on the productivity of rural women

Water scarcity significantly impacts the productivity of Bété women in the Sub-Prefecture de Gboguhé. As the main responsible for water collection, women rely on sufficient water supply for their daily activities, such as cooking and cleaning. When water is scarce, women have to travel long distances to find alternative water sources, leading to increased workload and considerable time loss. The Fig. 4 below presents the distribution of daily hourly rates of Bété women in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé.

The diagram provides an average representation of the types of activities that women engage in daily and the number of hours they dedicate to each activity. It was created based on information collected from women through focus groups. Each type of activity represents a portion of the 24-h day. The percentage is estimated based on the number of hours spent on each activity per day. However, these data can vary from one household to another and depending on circumstances, such as during ceremonies or funerals, where certain tasks such as field work and gathering firewood are replaced by water collection and cooking.

On average, women spend 29% of their daily time on water collection, approximately 7 h per day. Apart from water collection, domestic activities also occupy a significant portion of their daily time with 29%, equivalent to 7 h per day. This constraint of time and energy limits women's ability to engage in other productive activities such as trade and agriculture, thereby reducing their economic opportunities and empowerment.

There are days when I can't sell because I haven't fetched water from the pump. Often when I go, there are many women ahead of me. By the time it's my turn, it's already 10 am. By the time you finish filling your 4 jerrycans of water, it's already 11 am or noon. At that time, you can no longer sell. To get water, I have to fetch it at night when there are not many people. But that means I sleep very late and wake up very early. K.N.C (Excerpt from focus group 2, 2022).

In the villages of Gboguhé, Gbiéguhé, Kékégoza, Koréa 2, and Zobéa, agriculture is a primary activity, and cash crops such as coffee, cocoa, and rubber are often considered strenuous tasks reserved for men. However, women are more involved in subsistence crops. After taking care of the family's water needs, they join their spouses in the fields in the morning, usually around 10 am. Upon returning, they are occupied with other household tasks.

These findings highlight that.

The act of water provisioning can result in significant income losses for women and their households. Women dedicate several hours each day to water collection, which includes walking to water sources, waiting in queues, and carrying heavy loads. This substantial amount of time could have been allocated to income-generating activities. However, due to the water collection duties, they have less availability to engage in economic activities such as agriculture, handicrafts, or entrepreneurship. These missed opportunities directly impact their ability to generate income for their families.

The loss of income restricts women's financial independence, sometimes leading them to rely on their spouses' economic resources, making them vulnerable in challenging economic situations. Recurrent income losses related to water provisioning can contribute to keeping women and their families trapped in a cycle of poverty, as financial difficulties hinder improvements in living conditions, as well as access to education and healthcare.

3.3.1 Health impacts related to the water shortage

3.3.1.1 Emergence of waterborne diseases

The shortage of clean water has significant health consequences for women, particularly the increased risks of waterborne diseases. When the available water is insufficient or contaminated as in Fig. 5, women face challenges in maintaining adequate hygiene standards, exposing them to a higher risk of water-related infections and diseases.

The use of unsafe water sources leads to gastrointestinal infections such as diarrhea, dysentery, and other bacterial and viral infections. The Table 5 below classifies the pathologies reported in women's discourse.

These waterborne diseases can be particularly dangerous for women, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

The last time, I thought I was going to die. I had severe stomach pain. I had diarrhea for three days. Even my son was affected. It was really difficult. My husband sent us to the hospital, and the doctor said it was the water from the stream that caused this illness. So, he gave us medications, and that saved us. M.Y. (Excerpt from focus group 5, 2022).

Bété women are sometimes the primary caregivers for health within their families, and when the shortage of clean water compromises their health, they are also limited in their ability to take care of their loved ones. Women are often the primary caregivers in many societies. When they contract waterborne diseases, they may require costly medical care. Expenses related to medical consultations, medication purchases, and hospitalization can place a heavy burden on the household budgets in rural areas. Furthermore, waterborne diseases result in temporary disability, leading to income loss for women and their families. Particularly in these rural societies where women significantly contribute to household income, this loss can have a substantial financial impact. The financial and social costs associated with waterborne diseases can trap women and families in a cycle of poverty. Unforeseen healthcare expenditures and income loss can make it challenging to improve their living conditions.

These results indicate that the inaccessibility to clean water in the Sub-Prefecture de Gboguhé is a significant factor hindering the health of the population in general and women in particular. Although women are aware of the risks associated with using unsanitary water sources, they are forced to use them due to the constraints imposed by the lack of hand pumps.

3.3.1.2 The impacts of physical strain of water collection for women

The physically demanding task of water collection in the context of water scarcity results in considerable physical strain for women. They are often compelled to travel long distances, sometimes several kilometers, to fetch water from distant sources. These exhausting and repetitive journeys are made on foot, with women carrying heavy containers filled with water on their heads or backs. This excessive burden and repeated posture of water transportation can lead to muscle strains, back pain, and joint problems. Women commonly use expressions to describe the physical consequences they experience due to the hardship of water collection, such as "back pain" "foot pain" "hip pain" and "my whole-body aches".

The daily number of trips made by women to fetch water typically ranges between two and five, depending on the size of their household and their water usage. However, these characteristics can fluctuate based on events (celebrations, funerals) or seasons (rainy and dry seasons). Moreover, the paths leading to the different water sources are usually located on steep slopes, complicating the water transportation. Women are thus forced to endure these long journeys, sometimes at the expense of their health, as demonstrated by the testimonies collected below:

Often, even after finishing fetching water, you feel pain all over your body; the next day, you have to go to the stream again; it's mostly because of the uphill. Imagine carrying a large container up that hill. When you finish fetching water, you're exhausted. N.V. (Excerpt from focus group 4, 2022).

This testimony shows that the water collection route significantly impacts women's health. The situation appears to be even more challenging for elderly women, as suggested by the following statement from a housewife in Gbiéguhé: "At the stream where you left, when we leave there, it's really hard with our age. When we leave there and arrive at the uphill to climb, it's difficult. Sometimes we have to call the children to come help us" said a housewife in Gbiéguhé.

From all the above, it is evident that the scarcity of clean water is a genuine health problem for women in Gboguhé, Gbiéguhé, Kékégoza, Koréa 2, and Zobéa. Additionally, women are also exposed to an increased risk of injuries related to water transportation, such as falls or slips on difficult terrains with steep slopes (Fig. 6).

These physical strains resulting from the hardship of water collection have a significant impact on the health and well-being of Bété women in rural areas, limiting their ability to fully engage in other activities and adding additional pressure on their already taxed bodies.

3.3.1.3 Impacts of water scarcity on women's mental health

The water supply in the context of water scarcity is a major source of concern and anxiety for women in the Sub-Prefecture de Gboguhé. As water managers within their households, they are responsible for ensuring that their families have a sufficient amount of water to meet their daily needs. However, when water resources are limited, women are constantly under pressure to find alternative and secure sources of water supply. The following quote illustrates this assertion: "When I go to bed at night, I am not at peace because when I think that I have to struggle again tomorrow to fetch water from the pump, everything annoys me". T.K.R (Excerpt from focus group 3, 2022).

This verbatim translates the fact that the relentless quest for water and the conditions under which it is carried out plunge women into an exhausting reality, both physically and emotionally. This reality extends far beyond the mere collection of water; it represents a daily challenge that has profound consequences on their lives. Women bear the responsibility of ensuring that their households have a sufficient quantity of water to meet the essential needs of the family, including drinking, cooking, and hygiene. The uncertainty regarding the availability of this vital resource creates a permanent anxiety. They are constantly concerned about the possibility of not being able to meet the fundamental needs of their family and the potential repercussions on the health of their loved ones.

In addition to emotional exhaustion, the uncertainty surrounding water supply adds extra stress to their already busy daily lives. Each day, they must navigate the complex puzzle of searching for water, juggling unpredictable factors such as availability, quality, and safety of the water. This constant stress can be overwhelming, as it weighs on their minds continuously. The accumulation of these factors has negative repercussions on the mental and emotional well-being of women. They may experience a sense of powerlessness in the face of this persistent reality, which can lead to episodes of depression and anxiety. The ongoing exhaustion can also affect their ability to cope with daily stress, sometimes resulting in family conflicts and social tensions.

In order to alleviate the pressure some women admit to setting alarms at 4:30 or 5 am to have a chance to collect water in large quantities. While this anxiety is shared by all women in the community, it is amplified for those who have to fetch water every day. However, some women prefer to avoid this source of anxiety and rely on good neighbors to provide them with water. Such solidarity, however, is dependent on the friendship and good relations that exist between households. Households equipped with a traditional well are then immune to the stress associated with this scarcity. Thus, water supply in the context of water scarcity is a major concern for women, affecting their family balance and tranquility.

4 Discussion of results

4.1 Women's contribution to water supply in rural areas

This study demonstrates that women play a crucial role in the water supply chain among the Bété. This finding aligns with cultural norms and the division of labor between men and women in Bété society. These results highlight the significance of Bété women in local culture regarding water management and their essential contribution to rural water supply. This social value assigned to women in water management is also observed in other cultures, such as the Lobi in the extreme north of Côte d'Ivoire and several regions in India [38,39,40,41]. This convergence of results suggests that women's roles in rural water supply are influenced by shared sociocultural values observed in various geographic contexts.

However, it is essential to note that each culture has its unique characteristics, and specific studies on Bété culture could provide additional insights into the values and practices specific to women in water supply. Further research could also explore regional differences within Bété culture and the environmental and historical influences on women's values and roles in water management.

4.2 Gender and social inclusion in the issue of access to clean water in rural areas

The results of this study have demonstrated that water can be a source of illness, and due to their crucial involvement in water supply in rural areas, women are the first to experience the health consequences of drinking water scarcity. These findings are supported by the work of Jones et al., which establishes a link between the use of contaminated water and the increased risk of waterborne diseases among women [42]. They represent the largest number of deaths from diarrheal diseases worldwide [43, 44]. Consequently, several authors advocate for the promotion of hand-pump water systems, considered better suited to address health and social challenges related to water access [45].

Apart from the quality of water consumed, the conditions of water supply (means used, transportation methods, etc.) can render this task arduous for women and lead to physical discomfort. Such water supply conditions seem to be frequent in rural areas where women balance water containers on their heads, carry them in their arms, or use both methods of transportation simultaneously while walking, as demonstrated by Bisung et al. and Stevenson et al. [44, 46]. These water transportation methods result in head and neck pain, axial compression, lower back pain, and joint pain [47,48,49,50,51].

Furthermore, the study's results also revealed a close correlation between limited access to water and the productivity of women, hindering their engagement in other income-generating activities. A relevant comparison can be drawn with the study conducted by Hickey et al. in a rural community in Sub-Saharan Africa, which highlighted the predominant role of women in water collection and its impact on their participation in economic activities [52]. In West Africa, housewives have to travel up to 10 km to collect 60 L of water [53]. In eastern Uganda, research has shown that women spend an average of 660 h per year fetching water for their households, equivalent to two whole months of work [54]. Therefore, Sorenson et al. estimate, from an economic perspective, that the time devoted to water collection constitutes a time loss with an economic cost [55]. In this context, water collection is regarded as an exhausting and often hazardous chore, preventing women from working and engaging in other occupations [6].

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study, focusing on the impacts of water scarcity on women in the Gboguhé Sub-Prefecture, has initially revealed that in Bété tradition, women are considered the guardians of water, given their essential role in ensuring the preservation and availability of this vital resource within the household. These roles are deeply rooted in local cultural values, highlighting the significant place of women in Bété culture.

However, the scarcity of clean water exposes them to significant socio-economic and health challenges, hindering their active participation and well-being. The water scarcity addressed in this study refers to the inability of public water supply infrastructure, such as hand-operated pumps, to provide a constant and necessary quantity of water to meet the daily water needs of users. From a socio-economic perspective, the lack of access to clean water negatively impacts women's productivity, preventing them from engaging in other economic activities. The inability to access a reliable and nearby water source limits their productivity and economic opportunities. Moreover, women are often burdened with the collection and transportation of water over long distances, which exposes them to increased fatigue and reduces the time available for other productive activities. From a health standpoint, the scarcity of clean water increases the risk of waterborne diseases among women. The use of contaminated water for drinking, cooking, and personal hygiene increases vulnerability to diarrheal diseases and infections.

This study is part of a broader context of research on the gendered consequences of water scarcity in rural areas, and it aligns with other studies conducted in similar regions around the world. Its findings are consistent with previous research that has emphasized gender disparities in water access and differentiated impacts on women's lives. Furthermore, the results of this study underscore the importance of recognizing and valuing women's contribution to water management, as well as taking concrete actions to address water scarcity. They highlight the imperative to adopt a gender-responsive approach in water-related policies and interventions to meet the specific needs of women and promote equal access to this vital resource.

As a recommendation, it would be important to invest in more sustainable water supply infrastructure, such as village-level hydraulic systems, to reduce the workload of women and ensure a consistent daily supply of clean drinking water. An option could involve diversifying water sources, including adapting and improving traditional water sources to make them more efficient and reduce dependence on modern sources like hand pumps. There should be programs established to provide training for women, educating them on water management, hygiene, and preventive maintenance of hydraulic infrastructure. Regular awareness campaigns should also be organized within local communities to promote the value of clean water, hygiene, and girls' education, while encouraging active participation of women in these initiatives. Furthermore, efforts should be made to enhance women's involvement in water management committees and decision-making processes related to water at the local level, ensuring that women have a voice in the planning and implementation of water-related projects.

However, resolving water scarcity can only be achieved by considering women's cultural values, recognizing their traditional expertise in water preservation, and offering them opportunities for economic and social development. Thus, by adopting a transformative approach, this study emphasizes the need to go beyond simply addressing water scarcity and aiming to promote women's values and preserve essential cultural ties. By recognizing and valuing women's role as guardians of water, we can make significant strides towards sustainable, equitable, thriving, and more resilient rural communities.

Data availability

The data used in this study are derived from field research and are available from the corresponding author. In addition to the field research data, information on the state of hydraulic infrastructure in the Sub-Prefecture of Gboguhé can be obtained from the Ivorian Water Distribution Company (SODECI) within the framework of the Government Water Supply Program (PS-Gouv) and from the team of experts from JICA as part of the PCN-CI project.

Notes

The PS-Gouv is an initiative of the State of Côte d'Ivoire through the Ministry of Hydraulics as part of the 'Water for All' program. This project aims to ensure the proper functioning of the 21,000 pumps in the hydraulic park of Côte d'Ivoire.

The PCN-CI 2 is a capacity-building project for local government officials to provide public services in the field of access to clean water and education. This project has enabled local government authorities in the region to implement rural water supply and education projects through an assessment of the real needs of local communities.

References

Langford M, Winkler I. Muddying the Water? Assessing target-based approaches in development cooperation for water and sanitation. J Human Dev Capabil. 2014;15(2–3):247–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2014.896321.

Dos Santos S. Koom la viim : enjeux socio-sanitaires de la quête de l’eau à Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), Thèse de doctorat (Ph.D.), Université de Montréal, Canada, 2005.

S. Archana, Gestion des ressources hydriques : perspective des femmes en milieu rural en Inde, No 132, 2021/2, 2021, pp. 84–89

Howard G, Bartram J. Domestic water quantity Service Level and Health. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

Boserup E, Tan SF, Toulmin C, Woman’s role in economic development, 0 éd. Routledge, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315065892.

Gorre-Dale E. Les femmes et l’eau, en Afrique, 2006, p. 79‑92

Ofouémé-Berton Y. L’approvisionnement en eau des populations rurales au Congo-Brazzaville. Com. 2010;63(249):7–30. https://doi.org/10.4000/com.5838.

WHO/UNICEF Joint Water Supply and Sanitation Monitoring Programme, World Health Organization, et UNICEF, Éd., Meeting the MDG drinking water and sanitation target: a mid-term assessment of progress. Geneva, Switzerland: New York: World Health Organization ; United Nations Children’s Fund, 2004.

Woldemicael G. The effects of water supply and sanitation on childhood mortality in urban Eritrea. J Bioso Sci. 2000;32(2):207–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932000002078.

Doss CR, Meinzen-Dick R. Collective action within the household: insights from natural resource management. World Dev. 2015;74:171–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.001.

Muñoz Boudet AM. On norms and agency: conversations about gender equality with women and men in 20 countries. Washington: World Bank; 2013.

Amadiume I, Caplan P. Male daughters, female husbands: gender and sex in an African society. In: Critique, influence, change, no. 11. London; New York: Zed, 2015.

Guyer J. Tradition in the frame: women’s accounts of cultural life in Mali. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999.

C. Okojie C. The role of women in rural development: the nigerian experience, J Sustain Dev Afr 2007:168‑186.

Azad MJ, Pritchard B. The importance of women’s roles in adaptive capacity and resilience to flooding in rural Bangladesh. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023;90:103660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103660.

Krishnan S. Adaptive capacities for women’s mobility during displacement after floods and riverbank erosion in Assam, India. Clim Dev. 2023;15(5):404–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2022.2092052.

Janif SZ, Nunn PD, Geraghty P, Aalbersberg W, Thomas FR, Camailakeba M. Value of traditional oral narratives in building climate-change resilience: insights from rural communities in Fiji. E&S. 2016. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08100-210207.

Singh P, Tabe T, Martin T. The role of women in community resilience to climate change: a case study of an Indigenous Fijian community. Women’s Stud Int Forum. 2022;90:102550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2021.102550.

Hou C, Wu H. Rescuer, decision maker, and breadwinner: women’s predominant leadership across the post-Wenchuan earthquake efforts in rural areas, Sichuan, China. Saf Sci. 2020;125:104623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104623.

Goheen M, B. Hayes B. Women and sustainable agriculture: interviews with 14 agents of change, Gender Dev, 2001:42‑52, 2001.

Fonjong L, Mbome F. The impact of water resource management on gender relations in rural Cameroon, Gender Dev 2003: 55‑63.

Davis S. Women’s role in water management: Insights from Tanzania, Gender Dev 2008:435‑449

Njiru C, Smits S. Gendered roles in water management: a case study of rural Kenya, Water Alternat 2017:289‑311, 2017.

Rocheleau D, Thomas-Slayter B, Wangari E, Feminist Political ecology: global issues and local experience, 0 éd. Routledge, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203352205.

Zwarteveen M, Meinzen-Dick R. Gender and property rights: Rethinking access to land and water. Agric Hum Values. 2001;18(1):11–25. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007677317899.

Mies M. Patriarchy and accumulation on a world scale revisited (Keynote lecture at the Green Economics Institute, Reading, 29 October 2005). IJGE. 2007;1(3/4):268. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGE.2007.013059.

Institut National de Statistique Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat. 2021.

N’Da P. Recherche et méthodologie en sciences sociales et humaines, Réussir sa thèse, son mémoire de master ou professionnel, et son article, Paris, 2015.

Saha CK. Dynamics of disaster-induced risk in southwestern coastal Bangladesh: an analysis on tropical Cyclone Aila 2009. Nat Hazards. 2015;75(1):727–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1343-9.

Alam E, Collins AE. Cyclone disaster vulnerability and response experiences in coastal Bangladesh. Disasters. 2010;34(4):931–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01176.x.

Chamlee-Wright E, Storr VH. Social capital as collective narratives and post-disaster community recovery. Sociol Rev. 2011;59(2):266–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2011.02008.x.

Aldrich DP. The externalities of strong social capital: post-tsunami recovery in Southeast India. J Civil Soc. 2011;7(1):81–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2011.553441.

Caretta MA, Vacchelli E. Re-thinking the boundaries of the focus group: a reflexive analysis on the use and legitimacy of group methodologies in qualitative research. Sociol Res Online. 2015;20(4):58–70. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3812.

Krueger RA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994.

Zamasiya B, Nyikahadzoi K, Mukamuri BB. Factors influencing smallholder farmers’ behavioural intention towards adaptation to climate change in transitional climatic zones: a case study of Hwedza District in Zimbabwe. J Environ Manag. 2017;198:233–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.073.

Ahmed I, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Van Der Geest K, Huq S, Jordan JC. Climate change, environmental stress and loss of livelihoods can push people towards illegal activities: a case study from coastal Bangladesh. Clim Dev. 2019;11(10):907–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1586638.

Grinschpoun M-F. Construire un projet de recherche en sciences humaines et sociales, Paris, 2014.

Johnson EN, Wilson NJ, Marshall AM. Gender and water: an introduction. UK: Routledge; 2019. p. 1–18.

Hirway I, Jose S. Understanding Women’s Work Using Time-Use Statistics: The Case of India. Femin Econ. 2011;17(4):67–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2011.622289.

Soro D. Socioanthropologie de l’échec des initiatives de promotion et d’accès à l’eau dans les communautés lobi du nord-est de la Côte d’Ivoire, Thèse de doctorat en Anthropologie, Université Allassane Ouattara, Bouaké, Côte d’Ivoire, 2017.

Smith LM. Women, water and work: Valuing female contributions to water management and livelihoods », In: van Halsema G, Rietveld L, (Eds.), Water, food and poverty in river basins: defining the limits. 2017; pp. 129‑147.

Jones AQ, et al. Public health implications of water availability, accessibility and use in rural areas: a systematic review, Environ Health 2016:1‑17.

Wutich A, Ragsdale K. Water insecurity and emotional distress: coping with supply, access, and seasonal variability of water in a Bolivian squatter settlement. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(12):2116–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.042.

Stevenson EGJ, et al. Water insecurity in 3 dimensions: an anthropological perspective on water and women’s psychosocial distress in Ethiopia. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(2):392–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.022.

Dos Santos S. L’accès à l’eau en Afrique subsaharienne : la mesure est-elle cohérente avec le risque sanitaire ? 2021:11(4):282‑286.

Bisung E, Elliott SJ, Abudho B, Schuster-Wallace CJ, Karanja DM. Dreaming of toilets: Using photovoice to explore knowledge, attitudes and practices around water–health linkages in rural Kenya. Health Place. 2015;31:208–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.12.007.

Mercer N, Hanrahan M. “Straight from the heavens into your bucket”: domestic rainwater harvesting as a measure to improve water security in a subarctic indigenous community. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;76(1):1312223. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2017.1312223.

Geere J-A, et al. Carrying water may be a major contributor to disability from musculoskeletal disorders in low-income countries: a cross-sectional survey in South Africa, Ghana and Vietnam. J Glob Health. 2018;8(1):010406. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.08.010406.

Geere JL, Mokoena MM, Jagals P, Poland F, Hartley S. How do children perceive health to be affected by domestic water carrying? Qualitative findings from a mixed methods study in rural South Africa: children’s perceptions of water carrying and health. Child. 2010;36(6):818–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01098.x.

Zolnikov TR, Blodgett Salafia E. Improved relationships in eastern Kenya from water interventions and access to water. Health Psychol. 2016;35(3):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000301.

Narain V. Shifting the focus from women to gender relations: assessing the impacts of water supply interventions in the Morni-Shiwalik Hills of Northwest India. Mountain Res Dev. 2014;34(3):208–13. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-13-00104.1.

Hickey S, du Toit L, Muchiri E, King T, Njenga M, Velleman Y. Negotiating the water divide: cooperative water governance in the Okavango River Basin, Water Alternat, 2018; p. 828‑849

Femme-Eau-Developpement, Association de solidarité internationale. 2005. [En ligne]. Disponible sur : www.solidarie.org

Water and Sanitation Program, Genre dans l’eau et l’assainissement, Kenya, 2010.

Sorenson SB, Morssink C, Campos PA. Safe access to safe water in low-income countries: water fetching in current times. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(9):1522–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.010.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the Regional Directorate of Hydraulics of Haut-Sassandra, who provided us with information on the standards for drinking water supply in Côte d'Ivoire. We also extend our thanks to SODECI for granting us access to the database of hand-pump diagnostics in the Haut-Sassandra region. Lastly, we sincerely appreciate the cooperation and availability of village chiefs, women's association leaders and women who actively participated in this study.

Funding

The research leading to these results received funding from Strategic Support Program for Scientific Research (PASRES) under Grant Agreement No 236 for the 1st call for projects in 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS developed the problem, carried out the documentary research, collected the data, analysed the data and wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interest in the publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seri, J.A.E. Women: guardians of water and cultural link amid drinking water scarcity in Gboguhé Sub-Prefecture, Central-West Côte d'Ivoire. Discov Water 3, 19 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-023-00043-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43832-023-00043-z