Abstract

By using data collected from a self-administered survey, this study evaluates the variation of mental wellbeing between individuals and neighborhoods and its personal and neighborhood determinants in Fresno, California. It reveals the disparities of mental wellbeing, physical activity, and neighborhood environment between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods in Fresno. Residents in disadvantaged neighborhoods report slightly lower levels of mental wellbeing and physical activity, significantly weaker neighborhood social capital, and much lower neighborhood environment quality. Our path analysis suggests that outdoor physical activity and perceived neighborhood social capital are the only two factors that influence mental wellbeing after controlling for personal socioeconomics and personality. Neither perceived nor objectively measured neighborhood environmental factors show significant and direct impacts on mental wellbeing. Neighborhood environment, however, shows indirect associations with mental wellbeing through their correlations with outdoor physical activity and perceived neighborhood social capital.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Research interest in the neighborhood effect on human health and wellbeing has increased tremendously in the past decade. Researchers recognize that in addition to personal and behavioral factors, neighborhood and environmental variables play distinct roles in determining health outcomes of individuals and health equity in a society (The World Health Organization, n.d.). A growing number of studies have evaluated the links between neighborhood environment and human health (see Arcaya et al., 2016 for a systematic review). Most of these studies focused on whether and how neighborhood characteristics determine physical health. “Socioeconomic indicators were the most commonly analyzed neighborhood variables and body mass was the most commonly studied health outcome” (Arcaya et al., 2016). Research on the connection between neighborhood environment and mental health is relatively new and have mainly focused on mental illness rather than positive mental wellbeing (Bond et al., 2012). In addition, while many studies examined the effects of neighborhood environment on physical activity or health outcomes, few of them have evaluated the direct and indirect effects of neighborhood environment on both physical activity and mental wellbeing in one comprehensive model, despite of the obvious interconnectedness between them.

This study contributes to the literature by evaluating positive mental wellbeing and its potential determinants in Fresno, California, a city that is known for its concentrated poverty and health inequality. By collecting first-hand data via a self-administered questionnaire survey, we evaluate the disparities of mental wellbeing, physical activity, and neighborhood environment between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods in Fresno. We use a path analysis model to explore whether and how physical and social neighborhood environments (both perceived and objectively measured) directly and indirectly influence people’s mental wellbeing. Unlike previous studies that focused on mental illness, this analysis focuses on positive mental wellbeing that everyone experiences in their daily lives.

A number of studies found a significant association between neighborhood built environment and mental health. A study of 59 neighborhoods in New York City showed that persons were more likely to experience depression when they live in run-down neighborhoods with poor features such as a high percent of buildings in dilapidated and deteriorating conditions (Galea et al., 2005). Guite and colleagues examined the associations between the physical environment and mental wellbeing across many domains (Guite et al., 2006). Their study suggested that the most important neighborhood factors that operated independently on mental wellbeing were noise, sense of overcrowding, escape facilities, and fear of crime. A study of the impact of built environment on depression in older men in Australia showed that mixed land use and particularly the presence of retail stores around neighborhoods were associated with higher odds of depression (Saarloos, et al., 2011). Several studies show that urban parks play an important role in promoting both the physical and mental health of people in cities (Fernandez et al., 2022). A review of qualitative research on urban park use and physical activity suggest a number of park attributes (e.g., safety, aesthetics, amenities, and proximity) along with the perceived social environment of the park determine park use (McCormack et al., 2010). A study of park visitation in the College Station and Bryan metropolitan area shows that the presence of water bodies and playgrounds in urban parks are particularly critical in increasing park visitations (Song et al., 2022). By using social media data in the Twin Cities (Minnesota), researchers find that greater park visitations are associated with water features, better amenities, access to nearby trails and population density in nearby neighborhoods (Donahue, et al., 2018).

Neighborhood social environment, particularly neighborhood social capital, may also influence people’s mental health and wellbeing. Ehsan and De Silva (2015) reviewed 39 studies of the potential impact of social capital on mental disorder. Their review suggested that both individual and ecological social capital could protect people from mental problems. A review of 11 studies of the relationship between social capital and mental wellbeing in older people found that several elements of social capital was consistently and positively associated with better mental wellbeing (Nyqvist et al., 2013). Another review of 59 studies also found that social capital generated and mobilized at the family (e.g. positive parent–child relations and family support) and community (e.g. neighborhood quality and social network) levels had positive impacts on the mental health outcomes in children and adolescents (McPherson et al., 2014).

Neighborhood environment can indirectly influence residents’ mental wellbeing by creating more or less opportunities for social engagement within the neighborhood (Preiffer & Cloutier, 2016). A study of elder Hispanics in East Little Havana, Florida indicated that some building features such as the front entrance could reduce residents’ psychological distress because they promoted “eyes on street” and generated perceived social support within a neighborhood (Brown et al., 2009). A study based in a district of South Wales found that two key social capital components at the neighborhood level (trust and social cohesion) were positively associated with mental health after controlling for individual variables (Araya et al., 2006).

Neighborhood environment can also indirectly influence residents’ mental wellbeing by determining active travel and physical activity. There is a vast amount number of studies showing that urban form influences active travel (see Ewing & Cervero, 2010 for a comprehensive review). The links between neighborhood environment, physical activity, and mental health, however, have not been fully established (Preiffer & Cloutier, 2016). Researchers stipulate that travel behavior can affect subjective well-being through at least five channels: experiences during travel, activities during travel, travel itself as activity, engagement and activities that travel bring people to, and the feeling of freedom enabled by mobility and accessibility (De Vos et al., 2013; Mokhtarian, 2019). A number of empirical studies confirmed that walking and bicycling were positively associated with people’s life satisfaction (Morris, 2015), positive emotion (Ramanathan et al., 2014), and mental wellbeing (Ma et al., 2018; Martin, Goryakin, & Suhrcke, 2014). Physical activity could improve people’s mental health via the improvements in physical self-perception (psychosocial) and neurobiological and behavioral mechanisms (Lubans et al., 2016) and reduce anxiety, mental disorder, and depression (Have et al., 2011; Mammen & Faulkner, 2013).

In summary, an increasing number of studies examined and confirmed the positve impacts of neighborhood environment and physical activity on mental health. Few of them, however, evaluated the effects of neighborhood environment, physical activity, and mental wellbeing in one comprehensive model, despite of the obvious interconnectedness between them. Furthermore, the vast majority of previous studies focused on mental illness. This study partially fills these two gaps. First, we modeled the effects of neighborhood environment and physical activity on mental wellbeing via a path analysis model that allowed us to evaluate the connections between neighborhood environment, neighborhood social capital, physical activity, and positive mental wellbeing while accounting for the potential endogeneity caused by their inter-correlation. Second, this analysis focuses on people’s positive mental wellbeing. Only a small portion of population suffer from mental illness, but almost everyone experiences positive mental wellbeing on a daily basis (Bond et al., 2012). In addition, this study evaluated the health disparities between disadvantaged and better-off neighborhoods in Fresno and explored potential planning policies that could help to reduce health inequalities.

2 Conceptual framework, data, and methods

2.1 The conceptual framework

We consider five groups of variables that could influence mental wellbeing as suggested by the literature discussed above. We illustrate the potential connections between these five factors in Fig. 1. The first group of variables includes personal characteristics and family demographics. The second group of variables describe the perceived and objectively measured neighborhood environment. The third group represents neighborhood social environment. These three groups of variables are exogenous in our analysis. We assume the other two factors, the amount of outdoor physical activity and neighborhood social capital, to be endogenous. On the one hand, these two variables influence mental wellbeing; on the other hand, they are also determined by the exogenous personal and environmental variables in the model.

2.2 Study context: Fresno, California

The context of this study is the City of Fresno in Central California. Fresno is the fifth largest city in California with a population of 494,665 in 2010. According to the 2012–2016 American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.-a), the median household income in Fresno was $41,842, well below the state average $63,783. About 25% of families and people in Fresno lived below the poverty level, about two times higher than the state average. Fresno ranked No. 2 in the nation for cities with the highest rates of extreme poverty (Stebbins, 2018). Fresno ranks 94th among the 100 largest cities in the United States in terms of the availability and accessibility of urban parks (The Trust for Public Land, n.d.). Fresno is a car-dependent city. According to the 2012–2016 American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.-b), walk and bicycle together serve less than 2% of all commute trips in Fresno.

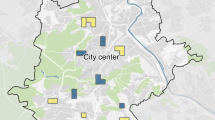

Fresno is a tale of two cities: the north part of the city is wealthy and largely White and the south part of the city is poor and largely Hispanic. Fresno has the second highest concentrated poverty rates among American metropolitan areas (Kneebone & Holmes, 2016). As Fig. 2 indicates, almost all the disadvantaged neighborhoods are concentrated in the south part of the city, particularly the downtown and surrounding areas. Residents in in disadvantaged neighborhoods, face an array of challenges posed by their poorly designed built environment and urban park system, which negatively affect their life quality and mental health. Adults in Central/Southeast/Southwest Fresno, where low-income Latino and African American neighborhoods are concentrated in, are more likely uninsured, nearly twice as likely to be obese, and much less likely to use urban parks (UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, 2011).

In this analysis, we use the Census block groups to represent neighborhoods in Fresno. We define disadvantaged neighborhoods in Fresno as the neighborhoods whose median household income is below the city median and poverty rates are above the city median. The definition thus mainly reflects the socioeconomic disadvantage that these neighborhoods experience. About 47% of Fresno population lives in disadvantaged neighborhoods (Fig. 2). In this article, we highlight the inequality between survey respondents in disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods by comparing their mental wellbeing as well as their physical and social neighborhood environment.

2.3 Data collection

We conducted a self-administered survey by mailing 3000 questionnaires to randomly selected addresses in Fresno. The questionnaire consists of questions that probe respondents’ mental wellbeing, physical activities, usage of parks, neighborhood environment (physical and social), and personal socioeconomics. The survey questionnaire took about 10–15 min to complete. Respondents received $20 gift cards if they returned their completed questionnaires early. We received 280 completed or partially completed questionnaires that are available for analysis. The post office returned 250 mails that were not delivered successfully because of vacant homes or wrong addresses. The effective survey return rate is 10.2%. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Fresno State University reviewed and approved this survey.

We also downloaded land use, parks, and street data in shapefiles from the webpage of the city of Fresno to measure the built environment of studied neighborhoods. We obtained the data of bike and pedestrian trails from the Fresno City Department of Public Works and the sidewalk data set from the Fresno Council of Government. The two data sets allowed us to develop variables to measure neighborhood walkability in an objective way. We obtained employment data at the Census block group level from Census’ Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics data set (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.-c). We relied on the 2012–2016 American Community Survey (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.-b) to obtain population and demographic data to measure neighborhood population density and social environment. We used the Census block groups to represent neighborhoods in Fresno.

3 Measurement and descriptive analysis

We explain our measurements of the outcome and explanatory variables in the next a few sections. We present their descriptive statistics in Fig. 3.

3.1 Socio-demographics of survey respondents

As noted earlier, we mailed survey questionnaires to addresses that we randomly selected from the entire city. Survey return rates, however, are lower in disadvantaged communities. About 36% (100 out of 279) of our survey respondents live in disadvantaged neighborhoods, which is lower than their share in the city’s population (47%). The survey respondents are more likely to be female (63%), White (52%) and older (45% of them above 54). Hispanic population, which accounts for 47% of Fresno population, is under-represented in our data sample (28%). In addition, our survey respondents are also more educated (47% reported to have bachelor or higher degrees) and wealthier than the city population.

3.2 Mental wellbeing

We adopt the seven-item Warwick-Edingburgh Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS) in which seven statements cover seven different feelings and thoughts related to mental wellbeing (Tennant et al., 2007). The items are all worded positively and cover both feelings and functioning aspects of mental wellbeing. The WEMWBS has been validated by studies of different segments of population in different countries and is sensitive to the changes that occur in the context of a variety of wellbeing promotion initiatives (Tennant et al., 2007).

Our survey questionnaire provided five-grade Likert response options for each of the seven statement: none of the time (1), rarely (2), some of the time (3), often (4), and all of the time (5). Figure 3a shows the average scores of the seven items for respondents in disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods. The scores of five items are within the range of 3.5 to 4.0. The statement of “I have been feeling relaxed” scores the lowest point (below 3.5) and the statement “I have been able to make up my own mind about things” scores the highest (above 4.0) in both disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods. It seems that Fresno residents are quite stressed but feel confident about making up minds. Respondents in disadvantaged neighborhoods score lower on every item than respondents in non-disadvantaged neighborhoods, suggesting that residents in disadvantaged neighborhoods experience lower mental wellbeing.

3.3 Physical activities

Survey respondents reported the amount of four types of outdoor physical activities (walking, running, riding a bicycle, and other) as well as indoor physical activities they had in the past seven days. For each type of physical activity, they reported the number of days, the total number of minutes, and the intensity (slow, moderate, and fast) of the activity. We reminded survey respondents to consider only the physical activities that lasted for at least 10 min.

Not surprisingly, walking is the dominating form of physical activities for our survey respondents. About 85% of respondents reported to have some walking activities in the past seven days. In contrast, only 22% of them did running and 21% of them rode bicycles. We sum up the total amount of physical activities that each respondent undertook in the past seven days and adjust it by the intensity of the physical activity. Low-intensity physical activities are excluded and high-intensity physical activities receive a weighting factor of two. We then categorize people who had less than 150-min physical activities as “not active”, those who had 150–300 min of physical activities as “active”, and those who had more than 300 min as “very active”. Most of our survey respondents are either very active (49%) or not active (34%). Only 17% of them are rated as active. As shown in Fig. 3b, respondents in non-disadvantaged neighborhoods are slightly more likely to be very active (51% vs. 46%) and active (20% vs. 12%) and less likely to be not active (29% vs. 42%).

3.4 Park use and perceived neighborhood environment

About 60% of our respondents visited a park at least once a month and 26% of them visited a park at least once a week. Respondents in disadvantaged neighborhoods visited parks slightly more often than their counterparts in non-disadvantaged neighborhoods. As expected, a lot more respondents in non-disadvantaged neighborhoods rated their neighborhoods as nice places to live in. Respondents evaluated the environment of their neighborhoods through seven statements. Each statement was rated on a five-grade Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Figure 3c demonstrates the average scores of the seven items in disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Non-disadvantaged neighborhoods were neater, cleaner, and safer and have more greenspace and trees than disadvantaged neighborhoods. Safety at night was rated particularly low in disadvantaged neighborhoods. The two types of neighborhoods, however, are not statistically different in terms of the perceived availability of active transportation infrastructure (sidewalk and bike lane/path).

3.5 Neighborhood social capital

Respondents in disadvantaged neighborhoods reported much lower levels of social capital. As shown in Fig. 3d, we asked survey participants to evaluate neighborhood social capital through five statements (adapted from Sampson et al., 1997). In general, neighborhood social capital was rated low. All the five items scored below 4.0 in both disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods.

3.6 Objectively measured neighborhood environment

In addition to perceived neighborhood environment, we used GIS data to measure neighborhood environment in an objective way. We calculated population and employment density to represent land use density in each neighborhood (represented by Census block groups). We categorized neighborhoods into three roughly even groups based on the level of mixed land use, which was measured by a ratio between the number of jobs and the number of residents in a neighborhood. We calculated three indictors to measure neighborhood walkability: sidewalk completeness, sidewalk density, and street intersection density. We also combined these three indicators into one walkability index through a factor analysis. We calculated the acres of parkland within a half mile of each respondent’s home to represent park accessibility. We categorized our survey respondents into two groups based on whether they lived within a half mile of pedestrian and bike trails. The t-tests showed that disadvantaged neighborhoods had statistically higher levels of population density than non-disadvantaged neighborhoods. The two types of neighborhoods, however, were not statistically different in terms of walkability, park accessibility, and the level of mixed use. A much higher proportion of respondents in non-disadvantaged neighborhoods, however, lived close to pedestrian and bike trails that are physically separated from local streets.

3.7 Principal component analysis

As noted earlier, we use multiple items to measure mental wellbeing and neighborhood environment in our survey questionnaire. We conduct principal component analyses (PCAs) to combine correlated items into a smaller number of extracted variables to reduce data redundancy. This is particularly important for further regression analyses given that our data sample is relatively small while the number of variables is large. It also helps to minimize the multicollinearity problem in regression analyses by transforming a number of highly correlated items into a small number of uncorrelated variables. We present the PCA results in Table 1.

The reliability test of the seven items that measure mental wellbeing yields a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient 0.81, suggesting internal consistency between them. The responses to the seven mental wellbeing states are uni-dimensional and points to one direction. The first extracted factor accounts for 48% of the total variance.

The PCA of the eight items that measure perceived neighborhood environment yields two extracted factors that account for 55% of the total variance. The first factor mainly represents the neatness and safety of a neighborhood. The second factor mainly represents the quality of active travel infrastructure. Hereafter we refer to the first factor as neighborhood “neatness and safety” and the second factor as neighborhoods “active travel infrastructure.” The five items that measure perceived neighborhood social capital are also uni-dimensional. The first extracted factor can explain 70% of the total variance.

4 Findings: major factors that predict mental wellbeing

4.1 Factors correlated with mental wellbeing, physical activity, and social capital

We run bivariate Pearson correlation and multiple linear regression to explore the variables that can predict mental wellbeing, outdoor physical activity, and neighborhood social capital (see Table 2 for the results).

The bivariate Pearson correlation indicates that mental wellbeing is positively correlated with the two behavioral variables: outdoor physical activity and park visit. Among the four neighborhood variables that are positively correlated with mental wellbeing, three of them describe the social environment of neighborhoods (social capital, income, and proportion of minority). A series of personal socio-demographic variables are correlated with mental wellbeing. After controlling for personal variables and outdoor physical activity in a linear regression, only one neighborhood variable is still positively associated with mental wellbeing: neighborhood social capital.

The amount of outdoor physical activity is positively correlated with park visit, which is expected. The amount of physical activity, however, is not statistically correlated with the acres of parkland within a half mile, which we use to measure park accessibility. It is positively correlated with four neighborhood variables: street intersection density that we use to measure block size, accessibility to a pedestrian and bicycle trail, neighborhood income, and the share of White population.

In the multiple linear regression, outdoor physical activity is significantly associated with only two neighborhood variables, street intersection density and proximity to a pedestrian/bicycle trail, after controlling for park visit frequency and personal variables.

Quite a number of neighborhood and personal variables are correlated with how one evaluates the social capital in his/her neighborhood. Seven of these variables remain statistically significant in the multiple linear regression. Everything else being equal, the level of perceived social capital in a neighborhood is positively associated with neighborhood neatness and safety and active travel infrastructure, but negatively associated with population density.

4.2 Path analysis

We use the path analysis to further explore the factors that predict mental wellbeing. The path analysis has a few advantages compared to the multiple linear regressions. First, it takes into account the potential endogenous relationship between some independent variables. In the path analysis, we are able to treat the predictors of mental wellbeing as endogenous variables if they are also determined by other variables in the model. As noted in our conceptual framework (Fig. 1), we consider two predictors of mental wellbeing, outdoor physical activity and perceived social capital, as endogenous variables. We include two additional regression equations to estimate explicitly how personal and neighborhood variables could influence these two endogenous variables. Second, the path analysis allows us to understand comparative strengths of direct and indirect relationships between variables. Some personal and neighborhood variables may not directly influence mental wellbeing, but they could indirectly affect mental wellbeing through the mediation of the two endogenous variables. The path analysis allows us to quantify these indirect effects.

We present the unstandardized coefficients of the path analysis model in Table 3 and the standardized coefficients in a path diagram (Fig. 4). The indices of model goodness of fit suggest that our model fit the data quite well. The chi-square test suggests that our model is correct in the population and all supporting assumptions hold. The CFI (0.994) is well above 0.90 and both RMSEA (0.014) and SRMR (0.026) are well below 0.05.

The results of the path analysis show that mental wellbeing is positively associated with the amount of outdoor physical activity. Everything being else equal, people who are more physically active tend to report higher levels of mental wellbeing. Among the many neighborhood variables that we have tested, neighborhood social capital is the only one that has a significant and direct effect on mental wellbeing. Two personal variables also show significant and direct impacts on mental wellbeing. Residents tend to report higher levels of mental wellbeing if they have bachelor or higher degrees. As will be discussed later, education also influence mental wellbeing indirectly through its positive association with perceived neighborhood social capital. Extroverts report higher levels of mental wellbeing. Neighborhood social capital seems to be the strongest predictor of mental wellbeing among the four significant variables, as suggested by the standardized coefficients in the path diagram.

Three neighborhood variables show positive but indirect effects on mental wellbeing via the mediation of outdoor physical activity. Residents tend to have better mental wellbeing if they visit parks more often. They are more physically active when they live within a half mile of a pedestrian/bike trail, or live in neighborhoods with smaller block size, ceteris paribus. Interestingly, the amount of physical activity is not statistically associated with the self-reported quality of active travel infrastructure within neighborhoods.

Three other neighborhood variables show positive but indirect impacts on mental wellbeing through the mediation of perceived neighborhood social capital. Perceived neighborhood social capital is positively associated with the two extracted variables that represent perceived neighborhood environment. Residents tend to report stronger social capital in their neighborhoods when they live in neighborhoods that are neater and safer and have better active travel infrastructure. Everything else equal, residents living in denser neighborhoods are likely to report weaker social capital in their neighborhoods.

5 Discussion

It is important to note the limitation of this study before proceeding to the discussion of our major findings and their policy implications. Though we mailed questionnaires to randomly selected addresses in Fresno, our data may not represent the city’s general population due to the self-selection bias. As noted earlier, our survey respondents are more educated, wealthier, and older than the general population in Fresno. The sample size of our survey is small due to budget constraints and low response rates (varies from 246 to 280 depending on specific variables). The sample size, however, is above the minimum sample size that is required for a path analysis (the rule of thumb is 200). We minimize the loss of degrees of freedom in regression analyses by reducing the number of variables through PCAs and removing variables that are not statistically significant.

Despite of its limitations, the study contributes to our understanding of the connections between neighborhood environment, physical activity, and mental wellbeing. Our descriptive analyses show that residents in disadvantaged neighborhoods report slightly lower levels of mental wellbeing. Stress and anxiety seem to be a prominent reason that hinders Fresno residents from reporting better mental wellbeing, no matter what types of neighborhoods they live in. The t-tests that compare mental wellbeing and physical activities of respondents in the two types of neighborhoods, however, are not statistically significant. As noted earlier, our analysis may underestimate the disparities of mental wellbeing and physical activity between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods because more educated and wealthier residents are over-represented in our data sample.

Survey respondents in disadvantaged communities report significantly weaker social capital in their neighborhoods. They also score their neighborhoods lower on five out of the seven items that represent different dimensions of neighborhood environment. Not surprisingly, non-disadvantaged neighborhoods are neater, cleaner, and safer, and have more trees and greenspace. Perceived availability of active travel infrastructure (reported by survey respondents) is not significantly different between the two types of neighborhoods and our objectively measured walkability index confirms this. This contradicts the traditional local wisdom that wealthier neighborhoods in north Fresno enjoy much better active transportation infrastructure. Our data, however, do show that residents in north Fresno have much better access to pedestrian and bicycle trails and that are physically separated from streets. Future studies should examine the disparity between objectively measured access to trails and self-report access to trails as well as how the disparity influences people’s physical activity and mental wellbeing.

Our path analysis suggests that outdoor physical activity and neighborhood social capital are the only two factors that influence mental wellbeing after controlling for personal socioeconomics and personality. Neither perceived nor objectively measured neighborhood environmental factors show significant and direct impacts on mental wellbeing. Neighborhood environment, however, shows indirect associations with mental wellbeing through their correlations with outdoor physical activity and perceived neighborhood social capital. Residents are more likely to report better mental wellbeing when they live in neighborhoods that are safer and neater and have better active transportation infrastructure because these neighborhood characteristics strengthen neighborhood social capital. Higher neighborhood population density (objectively measured) could have a negative impact on mental wellbeing via its negative correlation with neighborhood social capital. Two objectively measured variables, neighborhood block size and access to a pedestrian/bike trail, can have indirect and positive associations with mental wellbeing via their correlation with the amount of outdoor physical activities.

The results of this study highlights the key role of neighborhood social capital in determining positive mental wellbeing in Fresno. Unlike previous studies that suggested the association between social capital and the reduction of mental stress (Ehsan and De Silva, 2015; Nyqvist et al., 2013; McPherson et al., 2014), this study shows that neighborhood social capital not only has a direct impact on mental wellbeing, but also acts a mediator through which several other neighborhood characteristics influence mental wellbeing. Our analysis suggests that neighborhood environment, such as safety, neatness, and availability of active travel infrastructure, can significantly influence perceived neighborhood social capital. That means planers might be able to improve local residents’ mental wellbeing by designing and investing in better neighborhood infrastructure, particularly in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Our interview with local residents suggests that formal and informal neighborhood event and gathering (e.g. a block party) may improve their sense of safety and community, but also encourage them to undertake physical activities within their neighborhoods. In Fresno, residents are likely to have more outdoor physical activities when they live close to pedestrian and bicycle trails that are physically separated from traffic, which are concentrated in wealthier neighborhoods in north part of the city. The city could improve residents’ mental wellbeing in poorer neighborhoods by expanding the pedestrian and bicycle trails into those disadvantaged neighborhoods.

6 Conclusion: brief summary and potential implications

This pilot study conducted a self-administered survey in Fresno, California to evaluate the variation of mental wellbeing between individuals and neighborhoods and its personal and neighborhood determinants. The study reveals the disparities of mental wellbeing, physical activity, and neighborhood environment between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged neighborhoods in Fresno. Residents in disadvantaged neighborhoods report slightly lower levels of mental wellbeing and physical activity, significantly weaker neighborhood social capital, and much lower neighborhood environment quality. Unlike many previous studies that found the strong impacts of neighborhood built environment on subjective wellbeing, this analysis shows that outdoor physical activity and perceived neighborhood social capital are the only two factors that influence mental wellbeing after controlling for personal socio-demographics and personality. Neither perceived nor objectively measured neighborhood environmental factors show significant and direct impacts on mental wellbeing. Neighborhood environment, however, shows indirect associations with mental wellbeing through their correlations with outdoor physical activity and perceived neighborhood social capital. One major take-away from this study is the importance of people-oriented neighborhood design and planning in promoting subjective wellbeing. Planning for a happy neighborhood is not limited to the design of human-scale built environment, but also encompasses community development that improves social efficacy and trust among the residents in the neighborhood.

Availability of data and materials

The data were collected via mailed survey questionnaires and in-depth interviews. The original data are confidential and cannot be shared.

References

Araya, R., Dunstanb, F., Playleb, R., Thomasc, H., Palmerb, S., & Lewis, G. (2006). Perceptions of social capital and the built environment and mental health. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 3072–3083.

Arcaya, M. C., Tucker-Seeley, R. D., Kimb, R., Schnake-Mahl, A., So, M., & Subramanian, S. V. (2016). Research on neighborhood effects on health in the United States: A systematic review of study characteristics. Social Science and Medicine, 168, 16–29.

Bond, L., Kearns, A., Mason, P., Tannahill, C., Egan, M., & Whitely, E. (2012). Exploring the relationships between housing, neighborhoods and mental wellbeing for residents of deprived areas. BMC Public Health, 12, 1–14.

Brown, S. C., Mason, C. A., Lombard, J. L., Martinez, F., Plater-Zyberk, E., Spokane, A. R., et al. (2009). The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “Eyes on the Street.” Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 64(2), 234–246.

De Vos, J., Schwanen, T., Van Acker, V., & Witlox, F. (2013). Travel and Subjective Well-Being: A Focus on Findings, Methods and Future Research Needs. Transport Reviews, 33(4), 421–442.

Ehsan, A. M., Silva, De., & Mary, J. (2015). Social capital and common mental disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 69, 1021–1028.

Ewing, R., & Cevero, R. (2010). Travel and the built environment. Journal of the American Planning Association, 76, 265–294.

Fernandez, J., Song, Y., Padua, M., & Liu, P. (2022). A Framework for Urban Parks: Using Social Media Data to Assess Bryant Park, New York. Landscape Journal, 41(1), 15–29.

Galea S, Ahern J, Rudenstine S, Wallace Z, & Vlahov D. (2005). Urban built environment and depression: a multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59, 822-827.

Guite, H., Clark, C., & Ackrill, G. (2006). The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public Health, 120, 1117–1126.

Have, M., de Graaf, R., & Monshouwer, K. (2011). Physical exercise in adults and mental health status Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 71, 342–348.

Kneebone E, & Holmes N. (2016). U.S. concentrated poverty in the wake of the Great Recession. The Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/u-s-concentrated-poverty-in-the-wake-of-the-great-recession/ Retrieved on October 8th, 2018.

Lubans, D., Richards, J., Hillman, C., Faulkner, G., Beauchamp, M., Nilsson, M., et al. (2016). Physical Activity for Cognitive and Mental Health in Youth: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20161642.

Ma, L., Kent, J., & Mulley, C. (2018). Transport disadvantage, social exclusion, and subjective well-being: The role of the neighborhood environment—evidence from Sydney, Australia. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 11(1), 31–47.

Mammen, G., & Faulkner, G. (2013). Physical Activity and the Prevention of Depression: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(5), 649–657.

Marie L., Donahue Bonnie L., Keeler Spencer A., Wood David M., Fisher Zoé A., Hamstead Timon, & McPhearson. (2018). Using social media to understand drivers of urban park visitation in the Twin Cities MN. Landscape and Urban Planning, 1751-10 S0169204618300550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.02.006.

Martin, A., Goryakin, Y., & Suhrcke, M. (2014). Does active commuting improve psychological wellbeing? Longitudinal evidence from eighteen waves of the British Household Panel Survey. Preventive Medicine, 69, 296–303.

McCormack, G. R., Rock, M., Toohey, A. M., & Hignell, D. (2010). Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: A review of qualitative research. Health & Place, 16(4), 712–726.

McPherson, K. E., Kerr, S., McGee, E., Morgan, A., Cheater, F., McLean, J., & Egan, J. (2014). The association between social capital and mental health and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: An integrative systematic review. BMC Psychology, 2(7), 1–16.

Mokhtarian, P. (2019). Subjective well-being and travel: Retrospect and prospect. Transportation, 46, 493–513.

Morris, E. (2015). Should we all just stay home? Travel, out-of-home activities, and life satisfaction. Transportation Research Part A, 78, 519–536.

Nyqvist, F., Forsman, A. K., Giuntoli, G., & Cattan, M. (2013). Social capital as a resource for mental well-being in older people: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 17(4), 394–410.

Pferffer, D., & Cloutier, S. (2016). Planning for happy neighborhoods. Journal of the American Planning Association, 82(3), 267–279.

Ramanathan, S., O’Brien, C., Faulkner, G., & Stone, M. (2014). Happiness in motion: Emotions, well-being, and active school travel. The Journal of School Health, 84, 516–523.

Saarloos, D., Alfonso, H., Giles-Corti, B., Middleton, N., & Almeida, O. P. (2011). The built environment and depression in later life: The health in men study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(5), 461–470.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

Stebbins S (2018). Despite overall sustained GDP growth in US, some cities still hit hard by extreme poverty. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/economy/2018/04/23/cities-hit-hardest-extreme-poverty/528514002/ April 23, 2018. Retrieved on October 8th, 2018

Song, Y., Newman, G., Huang, X., & Ye, X. (2022). Factors influencing long-term city park visitations for mid-sized US cities: A big data study using smartphone user mobility. Sustainable Cities and Society, 80, 103815.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., et al. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(63), 1–13.

The Trust for Public Land. (n.d.). The Trust for Public Land Releases 2018 ParkScore® Index, Ranking Park Systems in the 100 Largest U.S. Cities. https://www.tpl.org/media-room/trust-public-land-releases-2018-parkscore%C2%AE-index-ranking-park-systems-100-largest-us#sm.000fpssnvp6sd3v10jm2bzvtg4aq5 Retrieved on October 8th, 2018:

The World Health Organization (n.d.). Physical activity. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity Retrieved on October 8th, 2018

UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. (2011). Building Healthy Communities: Central/Southeast/Southwest Fresno. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/chis/bhc/Documents/BHC_Fact_Sheet_Fresno.pdf Retrieved on October 8th, 2018.

U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.-a). Selected Economic Characteristics: 2012–2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=CF Retrieved on October 8th, 2018:

U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.-b). Census FactFinder. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml? Retrieved on October 8th, 2018

U.S. Census Bureau (n.d.-c). Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics. https://lehd.ces.census.gov/data/ Retrieved on October 8th, 2018

Acknowledgements

The preliminary results of this study was presented at the 2019 TRB annual conference in Washington D.C.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Foundation under grant #1737380.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: H. Dong; Data collection: H. Dong, M. Li, M. Perez, & C. Wang; Analysis and interpretation of results: H. Dong, M. Li, M. Perez, & C. Wang; draft manuscript preparation: H. Dong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There is no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, H., Li, M., Perez, M.A. et al. Plan for healthy neighborhoods to improve mental wellbeing: a pilot study in Fresno, California. Comput.Urban Sci. 2, 26 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43762-022-00057-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43762-022-00057-8