Abstract

United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal targets to make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable; as it is predicting 95% urban expansion in the next decades. Consequently, urban livability can serve as a useful conceptual and analytical framework to improve the quality of urban life by facilitating the evaluation of the person–environment relationship and leading the improvement without deteriorating the environmental conditions. This present paper aims to identify the dimensions and indicators of subjective and objective livability for Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC). The residents’ perception has been carried out using stratified random sampling technique. Samples have been collected from the residents from each core, semi-periphery and peripheral areas of SMC. Mainly, adaptation of Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model involves four livability dimensions; under which the overall model explains 65% of the total variance indicating with the high reliability (α > 0.7) and the Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) about 0.90. The result indicates that, ‘Accessibility Factor’ bears the highest impact (24.91%) among the four latent variables and ‘Socio-Economic’ factor has the lower impact (8.39%) upon the urban livability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Livability refers to an urban system that contributes to the physical, social and mental well-being and personal development of all its inhabitants (Kashef, 2016). In fact, livability is about delightful and desirable urban spaces that offer and reflect cultural and sacred enrichment (Timmer & Seymoar, 2005). In short, livability means quality of life, standard of living or general well-being of a population in some area such as a city (Okulicz-Kozaryn, 2013). The term ‘livability’ has developed as an imperative significant idea in the field of urban studies (Ghasemi et al., 2018). Generally, the term signifies as a policy approach by the efforts of all the hierarchies of urban governances (Li & Yao, 2013). This holistic paradigm of human development and community well-being can be explained as an augmentation of the twin physical-environmental and cultural dimensions of any spaces (Balsas, 2004; Paul, 2020; Paul & Sen, 2018; Saitluanga, 2014). Mostly, researchers have adopted livability concepts based on their self-perspectives and research contexts.

Livability performance is also related with the quality of life in the urban area. This performance can be explained by the environmental quality, neighborhood amenity and individual well-being (Saitluanga, 2014). Hypothetically, it can be assumed that level of livability will differ from one place to another place and also increase from periphery to city central. So, livability can serve as a useful conceptual and analytical framework to improve the quality of urban life by facilitating the evaluation of the person–environment relationship (Kovacs-Györi et al., 2019). Besides, urban livability is a multifaceted concept associated with many domains of the living environment in urban areas, involving both the physical and socio-cultural environments (Zhan et al., 2018). The concept of Sustainable urban livability consist of set of economic, social and physical attributes or characteristics of a certain urban area, which, when improved without deteriorating the environmental conditions, will have a positive impact on residents’ quality of life (Valcárcel-Aguiar et al., 2018).

Whereas, the previous research indicates that the overall sustainability of an urban entity concentrates on urban planning and implementation which also impacts on urban livability (Al-Thani et al., 2019; Sharifi, 2016). The urban sustainability also depends on environmental performance and socio-economic sustainability indicating residents quality of life (Al-Thani et al., 2019; Jenks et al., 2010). Additionally, the terminology of ‘Urban Livability’, ‘Quality of Urban Life (QUOL)’ and ‘Quality of Life (QOL)’ are interrelated to each other; though they have a huge scale difference. Urban Livability is the degree to which urban citizens’ participation in decision-making on matters meeting their well-being (Weje et al., 2018). Otherwise, urban livability is both the tangible and intangible characteristics of urban environment which makes attractive for habitation (Throsby, 2005). Urban quality of life (QUOL) refers to the urban planning whose objective is to realize the sustainability of the development with respect to an individual’s quality of life. Meanwhile, Quality of Life (QOL) indicates the outcome of the perception of existing conditions and the degree to which they meet the desire and expectations of individuals (Massam, 2002). The concept of Quality of Life (QOL) is expressed in both objective and subjective manners. Subjectively it indicates the ‘Well-being’ and objectively it assumes as ‘Quality of a place’ (Murgaš, 2016). Quality of Life as the satisfaction that a person receives from surrounding human and physical conditions, conditions that are scale-dependent and can affect the behavior of individual people, groups such as households and economic units such as firms (Mulligan & Carruthers, 2011). This work expressed Amenities are key to understanding quality of life (QOL) because they are precisely what make some places attractive for living and working, especially relative to other places that do not have them. In 1970s, Marans & Stimson, 2011, introduced the concept of Quality of Urban Life (QOUL) as a social indicator movement which illustrates the quality of life emphasizing the built-up environments such as city or its neighbourhood or dwelling (Marans & Stimson, 2011). Keul & Thomas, 2011 analyzed the Salzburg Quality of Urban life with GIS Support. He tested the correlation analysis to explore relationship between assessed QOUL and environmental and person factors such as housing, shops, greenery, leisure, neighbors and safety. The result shows housing, greenery, neighbor and safety has highly positive correlation. Moreover, reorganization of recent developed artificial intelligence-based transportation and communication system, e-services are also increasing the pace towards sustainable urban livability (Al-Thani et al., 2019; Deakin, 2015).

Urban unit-based livability assessment also plays a crucial role for inter-regional comparison of livability. The index of livability assessment mainly constructed on the basis of either on composite index, Analytical Hierarchical Process (AHP) or on Remote sensing based (Mushtaha et al., 2020; Satu & Chiu, 2017; Valcárcel-Aguiar et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2020). Zhu et al., 2020, constructed a reliable and dynamic model for livability assessment in Lyni city of Shanghai provinces in China based on Remote Sensing and Internet oriented geospatial data. Shabanzadeh Namini et al. (2019) evaluated the livability indicators of the metropolitan Tehran districts of Iran. In this study, the indicators have been determined in terms of environmental, social, and economic aspects, and the current status of Tehran. Similarly, both the objective and perceived characteristics of the urban environment may influence domain satisfactions such as commute satisfaction, neighbourhood satisfaction, and housing satisfaction, thereby influencing subjective well-being (Mouratidis, 2020). In the middle east, metropolitan unit level based spatial livability has been evaluated where indicators have been wisely chosen under social, economic and environmental dimensions (Ghasemi et al., 2018). Policy relevant urban livability index added other instances concerning daily living and social infrastructure mix such as bus stop, train station, supermarket, community, culture and leisure centres (Higgs et al., 2019). Subjectively, commuting satisfaction, neighborhood satisfaction and housing satisfaction of the respondents also proven as predictors of urban livability (Mouratidis, 2020). On the contrary, researchers also argued that urban forms in buildings and streets affects the urban livable space both positively and negatively (Martino et al., 2021).

Most of the research regarding urban livability depicts mainly on assessment of livability index, neighbourhood analysis and satisfaction survey based in both meso and micro scale. Besides Majority of the Livability concept concentrates in developed world (Badland et al., 2014; Iyanda et al., 2018; Kovacs-Györi et al., 2019; Okulicz-Kozaryn, 2013; Song, 2011; Woolcock et al., 2009; Zhan et al., 2018). In this present research the literature-based indicators have been chosen to fit for livability assessment of Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC) in both subjective and objective way. As an emerging city, Siliguri has a diversified physical and socio-economic aspects; but the city is not included under the smart city project of the government of India (The Telegraph, n.d.; Chakraborti et al., 2018; Das, 2014). First of all, Latent factors have been derived upon which further study is going to be conducted on the basis of differential groups residing in different nooks and corners of the Corporation area. So, the main research gap is first to identify or recognize various latent factors which is determining the majority of the livability aspects of the inhabitants of Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC). Here, the study has solely focused on the reorganization of the various latent factors which is contributing the livability aspects of the individual respondents. The further research is going to be conducted on the basis of the group variability of the satisfaction level. So, overall, the entire study gives a brief idea about the factors as well the emphasizing the various groups and their perceiving livability aspects. Moreover, this study is emphasizing Siliguri city adopting the indicators which is also been proven well in other urban areas; that application can help further planning towards sustainable livable city.

So, it is required to evaluate if the city itself capable for livability assessment under various dimensions. The main objectives of the present paper are to identify the dimensions and indicators of subjective and objective livability for Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC). Moreover, latent factors are also assessed based on the respondents’ perception emphasizing the most effective factor of livability.

2 Study area

Siliguri town is located in Southern part of Darjeeling District of West Bengal, India. It is a rapid grown city associated with different names such as ‘A gate-way of North-East India’, ‘A Transit Town’, etc. In 1931, Siliguri was a non-municipal town covering only 6067 population. The city got municipality status in 1949 with an area of 15.54 Sq. Km. with the rapid increase of population. (Owing to partition of Bengal as West Bengal and East Pakistan; later Bangladesh war in 1971, Siliguri became eventually a refugee centre.) Later it became an attraction point of employment, trade and transport centre. From Siliguri town it became Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC) in 1994 with 47 wards; which partly covers both Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri district of West Bengal.

Population growth of SMC is the major architect of rapid urbanization. According to the Census of India, from 1941 to 2001 the population increased from 10,487 to 472,374. But in last decade; that means from 2001 to 2011 the growth of population of SMC is 8.66%. The current population density of SMC is 12,165 persons per sq. km. (Census, 2011). Based on the nature of the urban area and characteristics of urbanization, SMC is carried out through JNNURM (Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission) scheme.

As a livability concern, this scheme tends to provide an improved quality of life and infrastructure in the cities aiming at economically productive, efficient, equitable and responsive Cities. So, the perception about livability perceived by the residents of Siliguri Municipal Corporation can point out the quality of urban life indicating the conducive urban development considering the underlying latent factors.

3 Data and methodology

Sample survey has been carried out to collect accurate, reliable and dependable primary data. Sample has been collected from the residents living in core, semi-periphery and peripheral areas of Siliguri Municipal Corporation (Fig. 1). Urban livability includes both objective and subjective measures. It is noted that, scholars have been arguing that ‘quality’ as a subjective dimension but Marans & Robert J. Stimson perceived it as an objective reality (Marans & Stimson, 2011). Both subjective and objective measures are treated to find out pattern of urban livability or quality of urban life (Milbrath, 1979).

In this present study, stratified random sampling technique has been adopted for survey in different localities of SMC. The stratification is carried out on the basis of three distinctive areas i.e., Core, Semi-Periphery and Periphery. From the CBD area (Ward No. 11) each 1.5-kilometer cumulative circular area has been designated as buffer zone. Buffer zone 1 is city core area, Buffer zone 2 is semi-periphery area and rest of the area has been marked as Buffer zone 3 (Fig. 1). However, the respondents who have been selected as the part of this study are representing any one of the mentioned buffer zones to fulfill the stratification. In this regard, the respondents under 18 years of age were not considered. A pilot survey was also carried out preceding final questionnaire was prepared. Based on the previous literatures the questionnaire was designed to measure residents’ perceptions and their evaluations about aspects of livability. The final questionnaire is comprised with 35 questions covering various attributes and dimensions of livability. Each question is formulated with five-point Likert Scale based on the respondent’s satisfaction level ranging from extremely unsatisfied to extremely satisfied level. On the basis of each individual response the master data table was constituted.

As mentioned in Table 1, the responses have been formulated with five-point Likert Scale based on the respondent’s satisfaction. The level indicating extremely unsatisfied (coded as 1), unsatisfied (coded as 2), neutral (coded as 3), satisfied (coded as 4) and extremely satisfied (coded as 5) level as follows. On the basis of each individual responses the master data table was constituted out of 47 municipal wards of SMC.

The sample size is also playing a significant role to precise interpretation of the perception study. In this present study, Cochran’s approach has been adopted to determine the required sample size. Based on the Cochran’s sample size determination, the required sample size for the present research is 385 (Paul, 2020).

4 Methods

4.1 Exploratory analysis

Factor analysis can be describes as the method for measuring the dimension of urban socio-spatial differentiation (Knox & Pinch, 2014). This is also a multivariate data reduction method that creates a precise and smaller set of variables from a larger data-set. In case of Exploratory factor analysis (EFA), each of the new set of manifest variables are grouped and categorized as a latent variable that represents a cluster of highly correlated variables. In the present study, principal component analysis (PCA) is utilized to explore the initial latent variables in Siliguri Municipal Corporation (SMC). Besides, Factor loading is representing the correlation coefficient for the manifest variables and factors. Each of the factor quality score is designated by the eigenvalues and higher eigenvalues represents the real factors of the underlying data. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) criterion and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, (indicating the adequacy of the data) have been used to determine the number of statistically significant (Baglin, 2014). The communality test has been introduced to measure the ratio of the explain variation. Varimax rotation method has been adopted as the orthogonal rotation methods, where rotation of the axis maximizes the sum of the variances of the squared loadings.

4.2 Construction of the measurement model using CFA

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is a type of structural equation modelling (SEM) that is concerned with a combination of measurement models. The use of CFA is to verify the relationships between measurement variables and their respective factors (Arifin & Yusoff, 2016). CFA has been performed in AMOS to evaluate the measurement model validity of the proposed Livability models. The validity has been evaluated through an assessment of model fit indices and other evidence of construct validity of the proposed and revised measurement models considering the regression weights analogous to factor loading. Following Brown’s (2006) recommendation, the following categories of fit indices have been considered in this study: absolute fit (chi-square goodness-of-fit [χ2], standardized root mean square residual [SRMR]), parsimony-corrected fit (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA]), (Tucker–Lewis fit index [TLI] and (comparative fit index [CFI]). The following cut-off values have been used to indicate model fit: χ2 p > .05, TLI and CFI ≥ 0.95, RMSEA and its upper 90% confidence limit ≤0.08, RMSEA’s close fit p > .05, and SRMR ≤0.08 (Arifin & Yusoff, 2016). Further assessment of construct validity involved an assessment of the main components of construct validity, namely, convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity was evaluated through an assessment of item factor loadings and their statistical significance, followed by an assessment of the factors’ average variance extracted (AVE) and construct reliabilities (CRs). Convergent validity has been indicated by an item factor loading ≥0.5 and p < .05, AVE ≥ 0.5, and CR ≥ 0.7. Next, discriminant validity has been evaluated by comparing factor AVE values with shared variances (SVs) between the factors, which are the squared correlations between any two factors. The factors are considered discriminant when the AVE values are greater than the SV values (Claes & Larcker, 1981).

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive statistics

Among the 385 sampled respondents, 65.7% are male and rest of 34.3% respondents are female. Respondents with higher secondary degree shares 35.8% of the total sampled respondents and similarly 27.3% respondents represent from graduate category.

Besides, only 8.3% has to be found as post-graduation and above category. Majority of the respondents are from self-employed (41.06%) and informal sectors (22.45%) of employment whereas most of the female respondents are engaged in household activities (63%). According to the surveyed data, 28.1%, 52.5% and 19.5% respondents are from low, medium and higher income group respectively. Among the respondents, about 53.8% lives in core area; whereas 30.1% and 16.1% people are from semi-periphery and periphery region. In terms of commuting behavior, 30.6% peoples are commuters and the rest of the people are considered as non-commuter. Figure 2 shows the stacked bar illustrating the descriptive statistics of the ordinal responses of the livability indicators from the survey in percentage.

5.2 Determination of livability factors

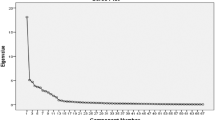

Livability Potential Factors has been determined by the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). It is generally used to reorder the 23 variables into a particular set of clusters based on the shared variance. The initial inspection of R-matrix indicates a substantial number of coefficients are above 0.40. After the initial run of EFA out of 23 indicators, some indicators have been eliminated based on specific significant criteria. From the Anti-Image Metrics the individual KMO value of each indicator can be compared. It can be reported that each of the indicators have met the sampling adequacy criteria among the 23 indicators. But the individual indicator showing KMO value less than recommended KMO value (0.60) has been eliminated. These indicators are Satisfaction on Waste Management and satisfaction on Municipality service showing KMO value of 0.553 and .567 respectively. Moreover, based on the low communality value indicator showing satisfaction on Child Recreation has been also eliminated because the value is 0.461 (recommended value > 0.50). Now the EFA has been again re-calculated among the 20 indicators after elimination of three factors (Table 2). The final EFA result exhibits that KMO value (.78) of 20 livability indicators with statistically significant result of Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ2 = 5066.95, p < .001). Here no individual KMO can be found less than .60 and the communalities of all indicators are greater than .50. Moreover, as there were no cross-loaded indicators in rotated component matrix, the final factors now can be determined.

Finally, the study reports 20 indicators of livability in four dimensions with the Eigenvalue more than 1. These indicators are explaining 65% of the total variance. From Table 2 the individual factor loadings of all the indicators can be found and this factor loadings indicate that higher the value of factor loadings is associated with higher the contribution on livability dimensions. These dimensions can be explained as follows:

-

a)

The first Livability Dimension has been reported as ‘Accessibility Factors’. The seven individual indicators under this factor indicates the comfortable distance to access the places responsible for better livability and explains 24.94% of the total variance. Among all the indicators, distance to auto stand and distance to public open space exhibits the highest factor loadings i.e., .881 and .861 respectively.

-

b)

The second Livability Dimension can be explained as ‘Social Well-being Factors’. In this cluster five indicators have been clubbed which shows 20.29% of the total variance. Moreover, satisfaction on overall safety indicator indicates high contribution (factor loading .870) and satisfaction on women safety creates low contribution (factor loading .681) in this domain.

-

c)

The third Livability Dimension has been named as ‘Transport Factors’. Under this domain three indicators have been sorted named satisfaction on road condition, satisfaction on street width and satisfaction on footpath comprising the factor loadings of .903, .869 and .792 respectively. This domain explains 11.38% of the total variance.

-

d)

The fourth and final Livability Dimension has been classified as ‘Socio-Economic Factors’. In this cluster five indicators have been identified by which only 8.39% of the total variance can be explained. Among these, job satisfaction has a higher contribution (factor loading .770) and house rent satisfaction has a low factor loading (.504) indicating low contribution under this domain.

5.3 Reliability assessment among the livability factors

Reliability of the individual indicators has been assessed under the respective Livability Dimensions to evaluate the internal consistency based on Cronbach’s alpha (α). It provides a reliability validation using all the potential ways of splitting the test items in an inter-item correlational matrix based on consistency of the data. If the Cronbach’s alpha value is > 0.7; the item can be marked as suitable for the analysis. The Table 2 shows a good agreement of Cronbach’s alpha (α) value which can be adopted as satisfactory.

5.4 Measurement model or structural equation model (SEM)

AMOS in SPSS software has been used to construct a Measurement Model adopting Maximum Likelihood (ML) Method and the goodness of the model fit was also measured. Based on the rotated component matrix created during CFA in SPSS this measurement model has been built. Initially all the 20 indicators under four factors have been selected and the model was run. The indicator named Dist_Supermarket from Accessibility Factor; crime_mgmt and Safety_Women from Social wellbeing factor; Own_ward and Houserent_sat were removed because of low factor loadings. Finally, 15 indicators have been retained with satisfactory factor loadings and good model fit. As presented in Table 3, the test of the overall model fit yielded in a χ2 = 254.933 with 82 degrees of freedom and a p-value of less than 0.000. All the fit indices were above the recommended values and for the Goodness-of-fit index (GFI) which was slightly above the 0.90 cut-off. The Double headed arrows in between the latent variables indicates the standardize covariance (i.e., correlation) likewise correspond to values shown in Fig. 3.

5.5 Dimensions and indicators of livability

Dimensions of urban livability may vary spatially and also from one person to another. Selection of the indicators depends on the socio-economic attributes and physical environment of the study area as well as objectives of the researchers (Pacione, 2010; Van Kamp et al., 2003). There is one objective dimension including Accessibility Dimension and three subjective dimensions which are Social Well-being Dimension, Transport Dimension and Socio-Economic Dimension respectively.

5.5.1 Objective dimensions of urban livability

Urban livability assessment is the way of evaluating spatial justice that concerns with the question of “who gets what, where and how” (Saitluanga, 2014). It is noted that the most geographical inquiries on livability have been based on objective measures of environmental quality (Pacione, 2010).

Accessibility dimension of urban livability

Accessibility factors intensify the level of infrastructural development and flow of movement replicating the availability of time and space on the urban lifestyle. Among the selected indicators, distance to bus stand (Dist_BUS) and distance to recreation centres (Dist_Recreation) have higher values of standard deviation since they were not located in every locality unlike other indicators (Table 4). Whereas, standard deviation is relatively lower for distance to supermarket (Dist_Supermarket). Coefficients of variation were relatively higher for distance to bus stand (Dist_BUS) and distance to recreation centres (Dist_Recreation) indicating the relatively lower density of these infrastructures in surveyed areas.

5.5.2 Subjective dimensions of urban livability

Subjective indicators are assessed from resident’s perception survey and urban living satisfaction. In his studies on quality of life in Taipei, Lee, 2008 describes quality as subjective and prosed the method of exploring quality of life by respondent perception. Though, it has been noted that subjective indicators have lower reliability but because of higher validity than objective indicators it is preferred(Tuan Seik, 2000).

Satisfaction from social well-being dimensions

Mean values in Table 4 show that on which indicator the respondents of SMC are satisfied in their perceived social well-being dimensions. Among the selected indicators of social well-being, respondents have shown highest level of satisfaction in their relationship with Satisfaction on Women Safety (Safety_Women) followed by satisfaction on Cleanliness (Clean_Satisfac) and Satisfaction on Crime Management (Crime_mgmt). Besides, they are minimum satisfied in terms of Satisfaction on Overall Safety (Safety_Overall) and Satisfaction on Open Space (Openspace_Satisfac).

Satisfaction from transport dimensions

In case of transport dimensions, the respondents are satisfied in existing road condition because SMC has a much coverage of asphalt based metaled road and the rest of the road is covered by concreate based. But they have also the strong disagreement in terms of Satisfaction on Street Width (Street_width) and Satisfaction on Footpath (Footpath_satisfac). Because, some residential areas are so congested that the street width is not permissible even on ambulance entry. On the other hand, only, the major important roads are arranged with the proper municipality defined footpaths. These roads are Hill Cart road and Sevok Road. But these footpaths are also not smoothly usable by the pedestrians as those areas are also blocked by the street vendors, illegal vehicle parking and mal management.

Satisfaction from socio-economic dimensions

Selected Socio-Economic dimensions has been selected as Satisfaction on Job Opportunity, Satisfaction on Recreation, Satisfaction on Super Market, Satisfaction on Own ward, Satisfaction on House Rent respectively. The respondents reflected their higher agreement in terms of satisfaction level on recreation (Recreation_Satisfac) and living own ward (Own_ward). But they are not satisfied in job opportunity and house rent perspective.

6 Discussion

Both the Objective and Subjective livability under the four latent factors have a remarkable impression on the overall urban livability of SMC. In continuation of that it can be mentioned that the obtained four latent factors show a good impact on the urban livability on the citizens of Siliguri Municipal Corporation. The first ‘Accessibility’ factor indicates the comfortable distance to access the places responsible for better livability (Badland et al., 2014; Salleh & Badarulzaman, 2012). It was found that the similar transportation access has the highest contribution to QOUL (Patil & Sharma, 2020). Previous research proven that greater accessibility to opportunities can have a positive impact on real estate values (Cordera et al., 2019). Some studies indicates that Cities with high population density and high GDP level obtain prominent benefits of accessibility (Cao et al., 2013). Moreover, the studies based on Indian cities still requires an extensive future work measuring the indicators and validating the links to casual network and there is a need of recognizing the difficulty in imparting Universal Mobility in old core cities in India (Jain & Tiwari, 2017; Mahapatra et al., 2021). The indicators under ‘Accessibility’ dimension basically depicts about the service accessibility within the concerned urban area. This objective livability indicator reflects the present infrastructural situation of the city varying city core to periphery or from municipal ward to ward. Each and every local unit of the city is comprised of the indicators related to auto stand, e-rickshaw stand, public open space and supermarket respectively. These objective indicators lead the basic livability criteria of an urban entity. Hence, the obtained result in this study also shows the medium to higher density of the infrastructural service indicating adequate distribution. Whereas, though the indicator related to bus stand and recreation centres intensify urban livability; since they are not situated in every municipal ward have a lower density of those services. Moreover, the result also exhibits that, both these two indicators have a significant factor loading indicating increasing density of bus stand and recreation centres the overall livability will be improved.

The ‘Social Well-being’ factors depend on general safety and clean environment also impacts on urban livability to a great extent (Martínez et al., 2015). Patil and Sharma (2020), also studied similar indicator under safety, security and environmental impact under gender role inspiring the quality of urban live in India (Patil & Sharma, 2020). It is important for Indian cities that the factors need to be further investigated to gain insights into perceived and measured components that influence environmental quality (Dutta et al., 2013). Meanwhile, the resident’s perception in this present study shows a remarkable agreement on the satisfaction on women safety followed by the others indicators like satisfaction on crime management and satisfaction on cleanliness. Besides, residents are likely to be less satisfied on Open Space condition of the present urban planning.

The ‘Transport’ factor is also important for city livability because socio economic development related with social wellbeing profile can be emerged by accessibility of an urban area which also depends upon the ‘Transport’ factor (Adriaanse, 2007; Maria-Carmen & Iordache, 2010; Paul, 2020). Public transport also holds an impactful share in several major cities in India. So, getting access to real-time information about public transport would certainly attract more users towards sustainable urban accessibility (Jairam et al., 2018). In current case, city dwellers also expressed their strong disagreement on street width satisfaction because of congestion. This congestion also leads to less satisfaction on footpath level. Because only the life line roads of Siliguri Municipal Corporation like Hill Cart Road and Sevok road is associated with proper footpath demarcated by the city administration. Otherwise, the pedestrians have to walk upon the lid covered drains beside the streets.

The ‘Socio-Economic’ factor indicates the employment opportunity and residence and leisure satisfaction of the respondents influencing the overall urban livability (Horan et al., 2001; Kundu, 2011; Maria-Carmen & Iordache, 2010). Recreation, economy and infrastructure also established as the valid indicator under QOUL domain in Indian perspective (Yadav & Gupta, 2021). It can be mentioned that provision of important services, competently well-performed infrastructure, open and green space, and well connectivity in the city may be satisfactory for a certain class of socioeconomic group to consider the place livable (Pandey et al., 2010). The interesting point to note that, in this study, the residents are not satisfied with the distance to recreation centres but they are satisfied with the availability of the recreation variations under the various ‘Socio-Economic’ dimension. The perception showed a good agreement in terms of living their own municipal wards but they expressed disagreement in terms of job opportunity and house rent respectively. The core residential areas like Hakimpara, Haiderpara, Ashrampara, Punjabipara, Babupara, Collegepara are associated with higher house rental values considering the apartments with BHK categories.

7 Conclusion

From the above result and discussion, it can be noted that only 20 indicators are assigned in broad aspect to assess the livability dimensions of SMC. However, four latent variables have been extracted after eliminating some indicators and thus the final model has been improved. In connection with that, one objective and three subjective dimensions of livability are also evaluated. The ‘Accessibility Factors’ under the objective livability dimension has the powerful contribution on livability based on the surveyed samples. Among these, as a subjective dimension, second factor (Social well-being Factors) can explain 20.29% of the total variance. The ‘Transport Factor’ and ‘Socio-Economic’ Factor can only explain 11% and 8% of the total variance respectively. So, according to the study objectives, four statistically significant factors under objective dimension and subjective dimension have been identified. Moreover, the first factor encoded with ‘Accessibility Factor’ can be report as most influencing and impactful factor because of relatively higher factor loadings which also fulfills the second study objective. The respondents are marginally satisfied with road condition but they have very dissatisfaction upon street width and footpath which have to be improved to increase the urban livability. In conclusion, it can be mentioned that, the latent factors which has been evaluated through EFA and CFA model, shows a significant impact on the overall urban livability. Based on the residents’ perception, urban planners can focus on the dimensions with all of its individual indicators for the better livability assurance. As ready to use social science data is less available in India; In the present study perception of the residents have been collected from the ground level for analysis. Hence the study recommends more and extensive further study which can be comparable to other Indian cities. Moreover, As the level of perception is dynamic and changes upon societal and temporal aspects, therefore, this study suggests a temporal assessment plan for better comparison to improve the existing livability. Apart from these, though ‘Accessibility’ factors gained the most impactful; based on the existing literature and theoretical conception it is recommended to flourish ‘Social well-being’, ‘transport’ and ‘socio-economic’ factors for smooth livability performance. Development of Urban Livability index regarding this context may help to quantify the present municipal ward-wise situation. This index will also act as indicator of comparative scenario for each ward of the Siliguri Municipal Corporation. Finally, a livability assessment framework can be established owing to the indicators both in subjective and objective manner by which the livability characteristics of SMC can be diagnosed for future urban quality of life.

Availability of data and materials

The authors confirm that the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- SMC:

-

Siliguri Municipal Corporation

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- QOUL:

-

Quality of urban life

- GIS:

-

Geographic information system

- JNNURM:

-

Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- CBD:

-

Central Business District

- KMO:

-

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

- SEM:

-

Structural equation model

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean square residual

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis fit index

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- AVE:

-

Average variance extracted

- CR:

-

Construct reliability

- SV:

-

Shared variances

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- GFI:

-

Goodness of fit index

- BHK:

-

Bathroom hall kitchen

References

Adriaanse, C. C. M. (2007). Measuring residential satisfaction: A residential environmental satisfaction scale (RESS). Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 22(3), 287–304 https://doi.org/10.1007/S10901-007-9082-9

Al-Thani, S. K., Amato, A., Koç, M., & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. (2019). Urban sustainability and livability: An analysis of Doha’s urban-form and possible mitigation strategies. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(3) https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030786

Arifin, W. N., & Yusoff, M. S. B. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Universiti Sains Malaysia emotional quotient inventory among medical students in Malaysia. SAGE Open, 6(2), 215824401665024 https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016650240

Badland, H., Whitzman, C., Lowe, M., Davern, M., Aye, L., Butterworth, I., Hes, D., & Giles-Corti, B. (2014). Urban liveability: Emerging lessons from Australia for exploring the potential for indicators to measure the social determinants of health. Social Science and Medicine, 111, 64–73 Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.003

Baglin, J. (2014). Improving your exploratory factor analysis for ordinal data: A demonstration using FACTOR. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation, 19, 5.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94

Balsas, C. J. L. (2004). Measuring the livability of an urban centre: An exploratory study of key performance indicators. Planning Practice and Research, 19(1), 101–110 https://doi.org/10.1080/0269745042000246603

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press

Brown, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Testing Structural Equation Models, 154, 136–162

Cao, J., Liu, X. C., Wang, Y., & Li, Q. (2013). Accessibility impacts of China’s high-speed rail network. Journal of Transport Geography, 28, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2012.10.008

Chakraborti, S., Das, D. N., Mondal, B., Shafizadeh-Moghadam, H., & Feng, Y. (2018). A neural network and landscape metrics to propose a flexible urban growth boundary: A case study. Ecological Indicators, 93(February), 952–965 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.05.036

Chau, P. Y. K., & Hu, P. J. H. (2001). Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A model comparison approach. Decision Sciences, 32(4), 699–719

Claes, F., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Cordera, R., Coppola, P., dell’Olio, L., & Ibeas, Á. (2019). The impact of accessibility by public transport on real estate values: A comparison between the cities of Rome and Santander. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 125, 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tra.2018.07.015

Das, C. (2011). People, Governance and development: a study of Siliguri Municipal corporation area (Doctoral dissertation, University of North Bengal)

Deakin, M. (2015). Smart cities and the internet: From mode 2 to triple helix accounts of their evolution. In Handbook of Research on Social, Economic, and Environmental Sustainability in the Development of Smart Cities https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-4666-8282-5.ch002

Dutta, S., Bardhan, S., & Bhaduri, S. (2013). Patterns of urbanization and environmental quality in the context of Indian cities. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 4(2), 287–299.

Ghasemi, K., Hamzenejad, M., & Meshkini, A. (2018). The spatial analysis of the livability of 22 districts of Tehran Metropolis using multi-criteria decision making approaches. Sustainable Cities and Society, 38(January), 382–404 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.01.018

Higgs, C., Badland, H., Simons, K., Knibbs, L. D., & Giles-Corti, B. (2019). The Urban Liveability Index: Developing a policy-relevant urban liveability composite measure and evaluating associations with transport mode choice. International Journal of Health Geographics, 18(1), 1–25 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-019-0178-8

Horan, T. A., Serrano, K. J., & Mcmurran, G. (2001). GIS for livable communities: Examination of community perceptions of assets, liabilities and transportation improvements. http://transweb.sjsu.edu.

Iyanda, S. A., Ismail, O., Fabunmi, F. O., Adeogun, A. S., & Mohit, M. A. (2018). Evaluating neighborhoods livability in Nigeria: A structural equation modelling (SEM) approach. International Journal of Built Environment and Sustainability, 5(1), 47–55 https://doi.org/10.11113/ijbes.v5.n1.245

Jain, D., & Tiwari, G. (2017). Sustainable mobility indicators for Indian cities: Selection methodology and application. Ecological Indicators, 79, 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.03.059

Jairam, R., Kumar, B. A., Arkatkar, S. S., & Vanajakshi, L. (2018). Performance comparison of bus travel time prediction models across Indian cities.

Jenks, M., Burton, E., & Williams, K. (2010). Compact cities and sustainability: An introduction. In The Compact City (1st ed.). E & EN Spon Press https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203362372_compact_cities_and_sustainability:_an_introduction

Kashef, M. (2016). Urban livability across disciplinary and professional boundaries. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 5(2), 239–253 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2016.03.003

Keul, A. G., & Thomas, P. (2011). The Salzburg quality of urban life study with GIS support. Investigating Quality of Urban Life, 45, 273–294 http://www.springer.com/series/6548

Knox, P., & Pinch, S. (2014). Urban social geography: An introduction. Urban Social Geography: An Introduction https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315847238

Kovacs-Györi, A., Cabrera-Barona, P., Resch, B., Mehaffy, M., & Blaschke, T. (2019). Assessing and representing livability through the analysis of residential preference. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(18) https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184934

Kundu, A. (2011). Trends and processes of urbanisation in India Human Settlements Group, IIED Population and Development Branch, UNFPA Urbanization and Emerging Population Issues-6 ii. http://pubs.iied.org/10597IIED.html.A

Lee, Y. J. (2008). Subjective quality of life measurement in Taipei. Building and Environment, 43(7), 1205–1215 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.11.023

Li, W. Y., & Yao, C. C. (2013). Trends of livability in the capital region of Taiwan. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 12(2), 293–300 https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.12.293

Mahapatra, G. D., Mori, S., & Nomura, R. (2021). Universal mobility in old core cities of India: people’s perception. Sustainability, 13(8), 4391. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084391

Marans, R. W., & Stimson, R. J. (2011). Investigating QOUL R.Maran book (Vol. 45).

Maria-Carmen, I., & Iordache, C. (2010). Clusters-tourism activity increase competitiveness support. Theoretical and Applied Economics, XVII, (5), 99–112.

Martínez, L., Short, J., & Ortíz, M. (2015). Citizen satisfaction with public goods and government services in the global urban south: A case study of Cali, Colombia. Habitat International, 49, 84–91 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.05.015

Martino, N., Girling, C., & Lu, Y. (2021). Urban form and livability: Socioeconomic and built environment indicators. Buildings and Cities, 2(1), 220–243 https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.82

Massam, B. H. (2002). Quality of life: Public planning and private living. Progress in Planning, 58(3), 141–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-9006(02)00023-5

Milbrath, L. W. (1979). Policy relevant quality of life research. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 444(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271627944400104

Mouratidis, K. (2020). Commute satisfaction, neighborhood satisfaction, and housing satisfaction as predictors of subjective well-being and indicators of urban livability. Travel Behaviour and Society, 21(June), 265–278 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2020.07.006

Mulligan, G. F., & Carruthers, J. I. (2011). Amenities, quality of life and regional development. Investigating Quality of Urban Life, 45, 107–134 http://www.springer.com/series/6548

Murgaš, F. (2016). Geographical conceptualization of quality of life. Ekologia Bratislava, 35(4), 309–319 https://doi.org/10.1515/eko-2016-0025

Mushtaha, E., Alsyouf, I., Al Labadi, L., Hamad, R., Khatib, N., & Al Mutawa, M. (2020). Application of AHP and a mathematical index to estimate livability in tourist districts: The case of Al Qasba in Sharjah. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 9(4), 872–889 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2020.04.001

Okulicz-Kozaryn, A. (2013). City life: Rankings (livability) versus perceptions (satisfaction). Social Indicators Research, 110(2), 433–451 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9939-x

Pacione, M. (2010). Urban liveability: A review. Urban Geography https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.11.1.1

Pandey, R. U., Garg, Y. G., & Bharat, A. (2010). A framework for evaluating residential built environment performance for livability. ITPI Journal, 7(4), 12–20.

Patil, G. R., & Sharma, G. (2020). Urban quality of life: An assessment and ranking for Indian cities. Transport Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.11.009

Paul, A. (2020). Developing a methodology for assessing livability potential: An evidence from a metropolitan urban agglomeration (MUA) in Kolkata, India. Habitat International, 105(September), 102263 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102263

Paul, A., & Sen, J. (2018). Livability assessment within a metropolis based on the impact of integrated urban geographic factors (IUGFs) on clustering urban centers of Kolkata. Cities, 74(June 2017), 142–150 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.11.015

Ramayah, T., Ahmad, N. H., & Hong, T. S. (2012). An assessment of e-training effectiveness in multinational companies in Malaysia. Educational Technology & Society, 15(2), 125–137.

Saitluanga, B. L. (2014). Spatial pattern of urban livability in Himalayan region: A case of Aizawl City, India. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 541–559 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0362-3

Salleh, A. G., & Badarulzaman, N. (2012). Quality of life of residents in urban neighbourhoods of Pulau Pinang, Malaysia. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 17(2), 117–123.

Satu, S. A., & Chiu, R. L. H. (2017). Livability in dense residential neighbourhoods of Dhaka. Housing Studies, 34(3), 538–559 https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1364711

Shabanzadeh Namini, R., Loda, M., Meshkini, A., & Roknedineftekhari, A. (2019). Comparative evaluation of livability indicators of the metropolitan Tehran’s districts. International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development, 11(1), 48–67 https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2019.1572611

Sharifi, A. (2016). From Garden City to eco-urbanism: The quest for sustainable neighborhood development. Sustainable Cities and Society, 20, 1–16 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2015.09.002

Song, Y. (2011). A livable city study in China using structural equation models. Most, June. http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:422188.

The Telegraph. https://www.telegraphindia.com/india/bengal-has-4-locations-in-list-of-98-named-for-smart-city-project/cid/1480901. Accessed 17 July 2021

Throsby, D. (2005). Cultural heritage as financial asset in strategies for urban development and poverty alleviation. Paper for International Conference for Integrating Urban Knowledge & Practice, Gothenburg, Sweden, 29 May–3 June, 2005

Timmer, V., & Seymoar, N.-K. (2005). International centre for sustainable cities.

Tuan Seik, F. (2000). Subjective assessment of urban quality of life in Singapore (1997-1998). Habitat International, 24(1), 31–49 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(99)00026-0

Valcárcel-Aguiar, B., Murias, P., & Rodríguez-González, D. (2018). Sustainable urban liveability: A practical proposal based on a composite indicator. Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(1) https://doi.org/10.3390/su11010086

Van Kamp, I., Leidelmeijer, K., Marsman, G., & De Hollander, A. (2003). Urban environmental quality and human well-being towards a conceptual framework and demarcation of concepts; a literature study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 65(1–2), 5–18 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(02)00232-3

Weje, I., Worahu, I., & Ndukueze, F. (2018). Quality of life and livability in selected neighborhoods in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications (IJSRP), 8(12). https://doi.org/10.29322/ijsrp.8.12.2018.p8451

Woolcock, G., Maginn, P., & Jones, R. (2009). Measuring up?: Assessing the liveability of Australian cities. State of Australian Cities: National Conference. http://soac.fbe.unsw.edu.au/2009/PDF/Woolcock%5CnGeoffrey.pdf.

Yadav, J., & Gupta, N. (2021). Urban quality of life: Domains, dimensions and indicators for Indian cities. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 796(1), 012032 IOP Publishing.

Zhan, D., Kwan, M. P., Zhang, W., Fan, J., Yu, J., & Dang, Y. (2018). Assessment and determinants of satisfaction with urban livability in China. Cities, 79(February), 92–101 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.02.025

Zhu, L., Guo, Y., Zhang, C., Meng, J., Ju, L., Zhang, Y., & Tang, W. (2020). Assessing community-level livability using combined remote sensing and internet-based big geospatial data. Remote Sensing, 12(24), 1–25 https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12244026

Code availability

Not applicable for this article.

Funding

The authors confirm that they did not received any grant or fund to prepare the above-mentioned research article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contribution of the First Author: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data Collection, Formal analysis, Original draft preparation, Contribution of the Second Author: Investigation, Methodology, Critical review and editing, Supervision. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for this article.

Consent for publication

The authors confirm the consent to the appropriate authority for the publication of the findings, which can include figures, tables within the text to be published in their respective Journal where the article has been submitted.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adhikari, A.K., Roy, T.B. Latent factor analysis and measurement on sustainable urban livability in Siliguri Municipal Corporation, West Bengal through EFA and CFA model. Comput.Urban Sci. 1, 23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43762-021-00023-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43762-021-00023-w