Abstract

As society increasingly integrates artificial intelligence (AI) into its fabric, AI ethics education in primary schools becomes necessary. Drawing parallels between the integration of foundational subjects such as languages and mathematics and the pressing need for AI literacy, we argue for mandatory, age-appropriate AI education focusing on technical proficiency and ethical implications. Analogous to how sex and drug education prepare youth for real-world challenges and decisions, AI education is crucial for equipping students to navigate an AI-driven future responsibly. Our study delineates the ethical pillars, such as data privacy and unbiased algorithms, essential for students to grasp, and presents a framework for AI literacy integration in elementary schools. What is needed is a comprehensive, dynamic, and evidence-based approach to AI education, to prepare students for an AI-driven future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

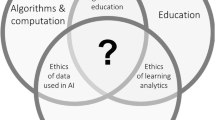

As society steers towards an age dominated by artificial intelligence (AI), there is a growing need for a revamped curriculum in schools [5]. AI literacy is quickly becoming as fundamental as traditional literacy and numeracy for informed participation in society. But AI literacy, if not fully integrated with AI ethics, is incomplete. Just as foundational topics like English, mathematics, and science prepare students with essential knowledge and skills, AI ethics education must be integrated into the educational infrastructure from the earliest stages of formal teaching and learning.

AI ethics education goes beyond mere awareness of AI technologies; it involves equipping students with the ethical frameworks necessary to navigate the complexities of a digital world. This education should start at an early age, laying the foundation for responsible and informed interactions with AI systems throughout students’ lives. By introducing AI ethics in primary school curricula, society can cultivate a generation that is not only technologically proficient but also ethically conscious. This dual, intertwined focus is essential for preparing students to make informed decisions and act responsibly in an AI-driven future.

In this paper, we argue that age-appropriate AI education, including both technical skills and ethical considerations, should be a mandatory part of primary schooling. In this, we go beyond the bulk of existing work which calls for AI education in the later years (i.e., secondary school and beyond). Our approach outlines strategies for integrating AI ethics into the primary school curriculum, providing educators with some practical tools and frameworks to bring this vital subject into classrooms. We propose a curriculum that integrates AI ethics with existing subjects, such as discussing ethical considerations in data use during math lessons or exploring the impact of AI on society in social studies classes. This integrated approach ensures that AI ethics is not an isolated topic, but a thread woven throughout the educational experience.

2 Informing policy: the case for mandatory AI ethics education

AI education can provide students with the background to navigate technologies that are permeating all aspects of life. Science education is mandatory in elementary and secondary schools in part because it equips students with the knowledge and tools to understand and make informed decisions in the society they will enter. Similarly, AI education provides a technical and philosophical foundation to grasp the risks, ethical considerations, and societal implications involved, equipping students with an awareness and understanding that will be essential for meaningful future work opportunities, social interactions, and informed participation in society [11, 16].

AI education is vital to equip students with the knowledge and skills to navigate an increasingly technology-driven world. One of the most important functions of schooling is preparing youth for participation in society, higher education, and work. AI is already transforming these realms and will likely continue to do so. AI literacy fosters informed agency in navigating new technologies and human–machine relationships. It promotes the judicious use of AI tools to augment human capabilities.

In modern education, parallels can also be drawn between sexual health and drug education and the emergent need for AI ethics education. Historically, both sex and drug education have been integrated into school curricula to address emergent societal concerns, emphasising informed decision-making and responsible behaviour among students. For instance, effective sex education programs have been designed to not only impart knowledge about human biology but also to discuss the complexities of relationships and personal responsibility. Comprehensive sex education extends beyond mere technicalities of human reproduction to cover broader aspects such as relationship dynamics [2]. Similarly, AI ethics education could transcend technical proficiency to include an understanding of the risks and ethical considerations involved in human–machine interactions. Both sex and AI education underscore the importance of managing intricate relationships, be they human-to-human or human-to-machine, in a complex and rapidly changing world. Since students will have experiences with both types of relationships, at least in a rudimentary way, during or prior to enrolment in secondary school, it is necessary that age-appropriate instruction on these complexities is introduced to the curriculum earlier on.

Likewise, age-appropriate drug education has evolved to offer more than just information about substances; it also focuses on critical thinking, understanding consequences, and making healthy choices. Drug education seeks to provide individuals with the information necessary to avoid harmful misuse, such as masking or escaping pain, which can lead to addiction and consequent loss of autonomy [12]. One aim of AI ethics education might similarly be to prevent over-dependence and its potential to curtail critical thinking and curiosity and thereby erode skills fundamental to informed agency. Both drug and AI ethics education emphasize judicious use: certain drugs (e.g., as medicine) can heal when used appropriately, and AI can augment human capabilities when applied responsibly. Just as drug education teaches students to understand the context and consequences of their choices, AI ethics education should guide students to comprehend the broader implications of AI technologies on privacy, fairness, and social dynamics. The challenge lies in delivering this complex subject matter in an age-appropriate and engaging manner. In a primary school setting realistic aims might be related to raising awareness among the students, for example, that privacy exists as a right and that it applies to oneself and to others. Likewise, students can be sensitized towards distinguishing between pictures, texts etc. that come from the “real world” (e.g. humans) and products that were generated by AI. Building on such an educational basis AI ethics education can effectively convey its principles, fostering a generation that is not only aware of AI's potential and limitations but also capable of using this knowledge to make ethical decisions in an increasingly digital world.

The introduction of AI ethics education in schools can draw valuable lessons from the implementation of sex and drug education. All three realms aim at fostering informed agency and responsible conduct. To the extent that this analogy holds, one can argue that an early introduction to AI should be mandatory for the same reasons that sex and drug education are. However, there are further compelling reasons in the case of AI. Understanding AI and applying it responsibly will be critical for children’s futures. Numerous schools already mandate instruction in topics like first aid, critical thinking, work experience, and physical education to furnish students with important life skills. AI ethics proficiency belongs in this category, if not exceeding these topics in usefulness. Beyond specific applications, AI shapes the contemporary world in ways that students must comprehend. Equipping youth with AI literacy should thus be considered as essential as teaching foundational subjects like math, science, and language.

The success of sex and drug education initiatives can be largely attributed to their practical, real-world approach, making the content both accessible and relevant to students. Similarly, AI ethics education can benefit from a holistic educational approach that extends beyond mere technicalities. This form of education should focus on developing students' critical thinking skills, particularly in understanding and assessing the ethical implications and societal impacts of AI. Such an approach would foster a responsible use of AI technologies.

3 Curricular integration: practical frameworks and challenges

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child [22] emphasises the critical need for digital literacy to be integrated from pre-school and sustained throughout the educational journey. According to their General Comment, a comprehensive curriculum should not merely focus on teaching students the technical aspects of using digital technologies. It should equip them with the skills on how to discern credible information sources and identify false or biased content. Students should grasp the underlying infrastructure, the business practices that drive it, strategies for persuasion, the implications of automated processes, as well as issues surrounding personal data and surveillance. There should be an exploration of the broader societal ramifications of an increasingly digitalised world. The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights [21] underlines that one of the core obligations is to ensure individuals—including children—receive a foundational education and skill set for scientific knowledge and application, including an understanding of new scientific applications such as AI. From a human rights perspective, all decisions related to children, including their education, should be taken with the best interests of children in mind [22].

From the moral point of view, mandating AI education is also a matter of fairness, justice, and equality. In its recent Recommendation on the Ethics of AI, UNESCO recommends that its Member States “provide adequate AI literacy education to the public on all levels in all countries in order to empower people and reduce the digital divides and digital access inequalities resulting from the wide adoption of AI systems” [23]. Given the ongoing automation of work, children now in school may face increasingly significant difficulties in accessing careers without some understanding of, and skill in operating, AI systems. If these skills and this understanding are not provided in public schools, children who are not taught these at home or otherwise exposed to them will not attain them. It is likely that these children will disproportionately come from generally disadvantaged backgrounds. Mandating AI education may thus be necessary to prevent widening the already substantial disparity in digital literacy and skills sometimes known as the ‘digital divide.’ It may also be necessary to ensure that future AI developers can be drawn from talent pools that are representative of society [19].

It is also desirable that all children learn the fundamentals of AI and thus share in the benefits of its progress from scientific, societal, political, and pragmatic perspectives [3, 8]. Rapid developments in generative AI, especially in large-language models such as GPT, Claude, LlaMA, and Bard, are already affecting education at all levels [4]. Thus, teaching children how to effectively and ethically use or abstain from these programs may be necessary simply to allow the rest of the educational mission to succeed. It may also be necessary to facilitate future scientific progress. AI models such as AlphaFold, which excel in predicting the 3D structures of proteins from their sequence, have already deeply transformed whole areas of science [9]. On the international stage, the countries that invest the most in AI-relevant education are also the ones that have the greatest number of AI-related patents and publications [10]. Robust investment in AI education may thus be prudent for countries hoping to draw their future scientists from a pool of AI literate students.

Integrating AI ethics into school curricula goes beyond rule-making; it's about creating an environment where ethical technology use is the norm. Instead of merely providing rules, this approach empowers students to critically consider AI's ethical implications. For instance, rather than simply instructing students to avoid certain apps due to privacy issues, encouraging them to question the importance of privacy in the digital realm is more impactful. This not only fosters responsibility and informed judgment but also aligns with the goal of developing individuals capable of ethical decision-making in a complex digital world. By prioritising ethical reasoning over rote compliance, AI ethics education seeks to produce not just rule-following students, but thoughtful, informed citizens who can navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by AI technology with discernment. As a practical case, in an initiative led by the MIT Media Lab, a curriculum focusing on the integration of AI ethics for middle school students has been developed. This curriculum highlights the need for students to understand both the technical aspects and ethical implications of artificial intelligence, including topics like algorithmic bias. It emphasizes thinking of algorithms as opinions and engages students in design activities to reimagine familiar AI systems, like YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, with ethics in mind. This approach empowers students to think critically about the ethical implications of AI, rather than just instructing them what to think [14, 24].

At the level of politics, the use of generative AI to manipulate the public’s access to information for political or sectarian interests implies the need for a public able to critically evaluate and question the authenticity and provenance of would-be information [17]. Conversely, societies that do not spread the benefits of AI progress throughout their population run the risk of fanning support for populist political parties [8]. As in the case of participation in medical research, reasonably informed consent is crucial for the legitimacy of voting and ultimately for democratic government. From the perspective of society more generally, making the most of the social and economic potential of AI will require a workforce able to understand and make judicious use of this general-purpose technology. Similarly, the effect of AI on the attainment of many societal goals, such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, is likely to be either positive or negative depending in large part on skills and awareness of likely impacts [13].

While forward-thinking, the inclusion of AI ethics education in elementary school curricula is fraught with practical and normative challenges. One pertinent issue is the accommodation of this expansive topic without compromising other essential subjects. To this end, a potential solution is the integration of AI education within existing subjects, in addition to treating it as a separate entity. For example, students can explore case studies of AI applications in medical diagnostics, creative arts, environmental solutions, or even the implications of deepfakes as an example of how digital media can manipulate reality as part of their science or social studies curriculum. This not only demystifies AI but also enables a more holistic understanding of its ethical and practical dimensions. Just as the recently updated science curriculum in Norway emphasises the social values of science, an AI-inclusive curriculum would foster discussions on ethical AI, data privacy, the challenges of discerning deepfake content, and the societal implications of automation [18].

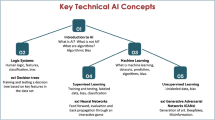

Other issues pertain to teacher preparedness for conveying the complexities of AI and to the cognitive readiness of elementary students to grasp these. One strategy relevant to both issues, emphasized in the UNESCO Recommendation on the Ethics of AI, is to begin by teaching “prerequisite skills” for AI education, “such as basic literacy, numeracy, coding and digital skills, and media and information literacy, as well as critical and creative thinking, teamwork, communication, socio-emotional and AI ethics skills” [23]. They could be further mitigated by continuing professional development programs and age- and culture-appropriate pedagogical approaches [6, 15]. For instance, fundamental principles such as data privacy and unbiased algorithms can be introduced in a manner akin to how specific facets of sex and drug education are adapted to suit different age groups. Students in science are taught to respect evidence and scientific method. Students in sex and relationship education are taught to respect each other and the ethics of relationships. In a similar way, students of AI must learn ethics. Ethics of AI is as important as the science and use of AI. Two foundational pillars are data privacy and unbiased algorithms [1]. Students must understand the concepts of justice, discrimination, bias and prejudice, and apply these to training and operation. However, perhaps most importantly, AI is a tool. It must be used ethically.

One common feature of AI ethics is the place of explanation or interpretability. Students should be taught the utility and principles of these. But more important than explanation is justification. Not only should the input (and training data), algorithms and operations of AI be able to be ethically justified, more importantly the outcome of AI must be capable of ethical justification. Is the outcome fair and just? Does it respect persons’ autonomy? Does it promote well-being? Students must be taught these concepts and related principles and how to apply them. This becomes most important in black box algorithms, particularly LLMs, where the operation and training set are largely obscure. The human use of AI, and its constant evolution, mean outcomes are constantly changing, necessitating new methods and standards of evaluation beyond those traditionally used (such as randomized trials in medicine).

If AI is not to be hijacked by large multinational companies with corporate interests (like the internet and social media), ethics education must be a pillar of AI education. It is the sine qua non because AI is perhaps the most powerful tool humans will ever have used. Students can engage in group projects to analyse AI-driven suggestions, mirroring the peer-review processes in scientific communities. AI principles can be woven into teaching methodologies. For instance, students can use simple AI-driven tools to analyse data in science experiments, understand patterns in literature, or even predict economic trends based on historical data. They can also draw on their personal experiences, e.g. with chatbots, to inquire about problems of interaction with non-humans in various facets (technical, cognitive, emotional etc.). Such integrations not only familiarise students with AI but also enrich their learning experience across subjects.

Drawing on lessons learned from the teaching of sex and drug education may help address many of these issues. For decades, moral and political opposition as well as lack of rigorous evaluations have led to drug and sex education programs which are in many instances ineffective [2, 7, 20]. While there is a strong case for early education on these subjects, the argument for early AI and ethics education is even more compelling and should not be a political issue. It is crucial that AI education avoid these traps, for example by engaging multiple stakeholders, including parents, educators, and policy-makers, in the development and implementation of the curriculum. Just as sex and drug education have undergone periodic revisions to address evolving societal norms and emerging research, AI education must be designed as a dynamic, evolving construct to adapt to technological advancements. Given the fundamental importance of the topic and the significant economic and opportunity costs involved in changing school curricula, AI education should, as far as possible, use evidence-based teaching methods and be subjected to ongoing scientific evaluation.

To effectively adapt primary education to the challenges and opportunities of an AI-driven era, specific and actionable proposals are necessary. Firstly, curriculum changes are imperative; this includes integrating modules that introduce basic AI concepts and ethical considerations, tailored to the cognitive levels of young learners. For instance, introducing storytelling with AI, simple coding exercises, or discussions on the impact of AI in everyday life can make the subject accessible and engaging. Secondly, teacher training programs must be revamped to equip educators with the necessary skills and knowledge to teach AI-related content. This could involve partnerships with tech companies or academic institutions specialising in AI. Additionally, the development of specialised training modules and continuous professional development courses will ensure that educators stay abreast of rapid advancements in the field. Lastly, student assessment methods need to evolve to reflect the integration of AI education. This might involve project-based assessments that allow students to demonstrate their understanding of AI in practical and creative ways, rather than relying solely on traditional testing methods. By implementing these changes, primary education can better prepare students for a future where AI is a fundamental aspect of both higher education and the professional landscape.

Though our focus is on education at the primary level, the point generalizes not only to older schoolchildren but also to the adult population. While education on AI should, if ever, only be mandatory for adults in special cases, it should nevertheless be offered for many of the same reasons. Just as adult education programs often include modules on financial literacy, health, and civic responsibilities, AI literacy courses can serve to bridge the knowledge gap for those who have already transitioned from formal schooling into the workforce or other life paths. This is particularly relevant given the accelerating pace of automation and the consequent reskilling and upskilling needs. Employers, community organizations, and educational institutions have a role to play in facilitating this extended learning, thereby fostering a society that is adept at both utilizing and critiquing AI technologies. Furthermore, lifelong learning opportunities in AI can help to ensure that the adult population remains engaged in democratic processes, capable of informed consent in political, research, and various ethical scenarios, and adaptable to labor market shifts influenced by AI and automation.

The world has been transitioning to advanced technology-based societies, a long-term trend in which AI represents a quantum leap. It is reshaping how we work, socialize, participate in civic life, and simply exist as humans. Just as teaching basic computer skills has become vital in today’s economic system, AI represents an even deeper layer of essential knowledge. In this context, AI literacy is arguably as important as foundational skills like literacy and numeracy. It is essential for young people to comprehend this new reality taking shape and contribute as informed citizens. Perhaps more important. If we are not to become slaves to AI, we must know how to use this new tool, ethically.

To the extent that we aspire to maintain human flourishing and democratic societies in an age of algorithms, AI education must be prioritized. Students need robust instruction on the technical dimensions of AI systems as well as the profound ethical considerations involved. We must have urgent debate on AI education and dedicate resources to integrating it throughout school curricula. Our children’s future depends on laying this strong foundation. The alternative is a world where the many are increasingly subject to the whims of the few who wield AI capabilities they little comprehend.

4 Conclusion

The goal of introducing AI ethics in schools should be seen not as an enforcement of rigid rules, but as a continuous, dynamic educational process that enriches students’ understanding and responsible use of AI technology. While establishing ethical guidelines is necessary, the greater emphasis should be on nurturing an ongoing learning journey that adapts to the evolving landscape of AI. This approach involves integrating AI ethics as a core component of continuous technology education, where students are encouraged to engage with, question, and critically analyse AI systems. Such an educational model fosters a deep understanding of how AI works, its societal impacts, and ethical considerations, thereby enabling students to apply this knowledge in real-world contexts. By doing so, AI ethics education becomes a tool for empowerment, equipping students not just with the knowledge of what constitutes ethical AI use, but also with the skills to actively contribute to a community that responsibly harnesses AI technology. This holistic approach ensures that AI ethics education is not about imposing restrictions, but about fostering an informed, ethically-aware, and technologically-competent generation.

Data and materials availability

All data are available in the main text.

References

Ali, S., Payne, B.H., Williams, R., Park, H.W., Breazeal, C.: Constructionism, ethics, and creativity: Developing primary and middle school artificial intelligence education. In: International Workshop on Education in Artificial Intelligence k-12 (EDUAI’19), vol. 2, pp. 1–4 (2019)

Braeken, D., Cardinal, M.: Comprehensive sexuality education as a means of promoting sexual health. Int. J. Sex. Health 20(1–2), 50–62 (2008)

Buccella, A.: “AI for all” is a matter of social justice. AI Ethics 3, 1143–1152 (2023)

Chiu, T.K.F.: The impact of generative AI (GenAI) on practices, policies and research direction in education: a case of ChatGPT and Midjourney. Interact. Learn. Environ. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2253861

Department for Education, UK: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-drive-to-better-understand-the-role-of-ai-in-education (2023)

Eguchi, A., Okada, H., Muto, Y.: Contextualizing AI education for K-12 students to enhance their learning of AI literacy through culturally responsive approaches. Künstl. Intell. 35, 153–161 (2021)

Faggiano, F., Minozzi, S., Versino, E., Buscemi, D.: Universal school-based prevention for illicit drug use. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, CD003020 (2014)

Gallego, A., Kurer, T.: Automation, digitalization, and artificial intelligence in the workplace: implications for political behavior. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 25(1), 463–484 (2022)

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., et al.: Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021)

Kitsara, I.: Artificial intelligence and the digital divide: from an innovation perspective. In: Bounfour, A. (ed.) Platforms and Artificial Intelligence. Progress in IS. Springer, Cham (2022)

Khogali, H.O., Mekid, S.: The blended future of automation and AI: examining some long-term societal and ethical impact features. Technol. Soc. 73, 102232 (2023)

Lowden, K., Powney, J.: An Evaluation Scotland Against Drugs Primary School Initiative Training. Scottish Council for Research in Education, Edinburgh (2021)

Miailhe, N., Hodes, C., Jain, A., Iliadis, N., Alanoca, S., Png, J.: AI for Sustainable Development Goals. 2 Delphi 207 (2019)

MIT Media Lab: Blakeley H. Payne, AI + ethics curriculum for middle school. https://thecenter.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/MIT-AI-Ethics-Education-Curriculum.pdf (2019)

Ng, D.T.K., Leung, J.K.L., Su, M.J., Yim, I.H.Y., Qiao, M.S., Chu, S.K.W.: AI literacy education in primary schools. In: AI Literacy in K-16 Classrooms. Springer, Cham (2022)

Danaher, J., Nyholm, S.: Automation, work and the achievement gap. AI Ethics 1, 227–237 (2021)

Porsdam Mann, S., Earp, B.D., Nyholm, S., et al.: Generative AI entails a credit–blame asymmetry. Nat. Mach. Intell 5, 472–547 (2023)

Mork, S.M., Haug, B.S., Sørborg, Ø., Ruben, S.P., Erduran, S.: Humanising the nature of science: an analysis of the science curriculum in Norway. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 44(10), 1601–1618 (2022)

Touretzky, D., Gardner-McCune, C., Breazeal, C., Martin, F., Seehorn, D.: A year in K–12 AI education. AI Mag. 40, 88–90 (2019)

Tupper, K.: Sex, drugs and the honour roll: the perennial challenges of addressing moral purity issues in schools. Crit. Public Health 24, 115–131 (2014)

UN CESCR: General Comment No. 25 on Science and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. E/C.12/GC/25 (2020)

UN CRC: General Comment No. 25 on children’s rights in relation to the digital environment. CRC/C/GC/25 (2021)

UNESCO: Recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence. SHS/BIO/REC-AIETHICS/2021 (2021)

Williams, R., Ali, S., Devasia, N., et al.: AI + ethics curricula for middle school youth: lessons learned from three project-based curricula. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 33, 325–383 (2023)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dabbagh, H., Earp, B.D., Mann, S.P. et al. AI ethics should be mandatory for schoolchildren. AI Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00462-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00462-1