Abstract

This paper studies how researchers who work in the field of basic research of artificial intelligence (AI) perceive their responsibility. A case study is conducted on an inter-university and interdisciplinary research cluster in Germany that specializes in basic artificial intelligence research. The reason for studying responsibility through the lens of such researchers is that working in basic research of AI involves a lot of uncertainty about potential consequences, more so than in other domains of AI development. After conducting focus groups with 21 respondents followed by a thematic analysis, results show that respondents restrict the boundaries of their sociotechnical visions, regard time as an influencing factor in their responsibility, and refer to many other players in the field. These themes indicate that respondents had difficulties explaining what they consider themselves responsible for, and referred to many factors beyond their own control. The only type of responsibility that was explicitly acknowledged by respondents is ex ante responsibility. Respondents define their responsibility in terms of things that are in their immediate control, i.e., responsibilities relating to their role and duties as researchers. According to the respondents, working in the field of basic research makes it difficult to make claims about ex post responsibility. Findings of this case study suggest the need to raise questions about how technological maturity is related to AI ethics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI), calls for ethical AI have been on the rise [1, 2]. One of the open questions to address in the field of AI ethics is the question of who is responsible for the impact of AI systems on society. Besides the attention that the question receives in the scholarly context, it is also of paramount importance in practice. Addressing it is essential for establishing frameworks for accountability and liability and for enabling involved actors (such as researchers, developers, operators, and users) to assess what expectations can reasonably be placed on their actions.

For several reasons, assigning responsibility for the impact of the use of AI systems is all but trivial. As the decision models of (ML-based) AI systems are not directly or explicitly coded by developers, they are often considered black boxes capable of “powerful predictions” which, however, “cannot be directly explained” [3]. Furthermore, many components of AI systems (such as machine learning models) can be utilized in various application contexts. Thus, researchers and developers working on such multi- (or general)purpose technical components cannot fully foresee all possible application contexts and the role their research findings would have here. This might be especially the case for researchers conducting basic research in the field of AI, as the level of technological maturity and thereby its foreseen application context is limited. Because the technologies these researchers are researching and developing are considered “elusive” [4], the question is if the researchers perceive their responsibility to be similarly elusive.

Acknowledging the difficulty in understanding who or what is responsible when creating new technologies and specifically AI, this present paper looks at the perceived responsibility of AI researchers working on understanding fundamental principles of intelligence and using this to develop and create machines. In doing so, the article contributes to a strand of research that approaches the issue empirically by examining the perspectives of developers and other creators of AI technologies on the issue of responsibility (see e.g., [5,6,7,8]). AI researchers working on basic principles in the field are chosen for this study as typically people working in research contexts on so-called emerging technologies deal with uncertainty [9], in part due to their low levels of technological maturity. Bearing this in mind, the guiding research question reads: how do AI researchers doing basic research on AI perceive their responsibility? This research question is answered by conducting a case study on an inter-university and interdisciplinary research cluster in Germany that specializes in basic artificial intelligence research. Focus groups are conducted to understand the perspectives of the researchers employed at this research cluster. This paper thereby builds on work that already acknowledges the importance of understanding AI ethics with AI developers and researchers (bottom-up) instead of talking to or about them about AI ethics (top-down) [5,6,7,8]. What follows is a theoretical framework that explains the conceptualizations of responsibility.

2 Theoretical foundations

Increased attention to the potential negative consequences of the use of AI has sparked debates about the responsibilities associated with developing and operating AI systems. On the one hand, this discourse raises the question of how isolated principles such as safety, security, non-discrimination or explainability [2] can be integrated into a “holistic understanding of […] responsible AI” [10]. On the other hand, the discourse addresses the role of actors involved in developing, deploying, operating, and using AI systems and asks who is responsible for (avoiding) adverse outcomes of the use of AI systems (see e.g., [11]). In accordance with its research question, this article focuses on this second dimension of the discourse on AI and responsibility. To address its research question, the following paragraphs clarify what responsibility is (or: what notions of the concept exist).

In the discourse on the nature of responsibility, varying meanings and concepts are discussed, some of them overlapping with adjacent concepts such as “accountability, liability, blameworthiness, […] and causality” [12]. However, while there is no generally accepted definition of responsibility, there are several features found in most conceptualizations. These include that responsibility is a relational term that contains (at least) a subject that bears the responsibility and an object that the subject is responsible for (cf. [13,14,15]). However, which conditions a subject needs to meet (or: which capabilities a subject needs to have) to be considered a (potential) bearer of responsibility and what objects one can be responsible for (or, in other words, what the scope of responsibility is) is a matter of extensive debate.

The remainder of this section explains various conceptualizations of responsibility in the context of research concerning and development of AI systems. In doing so, scholarly positions are outlined from philosophy and the field Science and Technology Studies (STS). It first addresses conceptual issues regarding subjects of responsibility, (i.e., who or what can bear responsibility), and second questions regarding objects of responsibility (i.e., what one can be responsible for). These two dimensions function as sensitizing concepts for the construction of the interview guide and the analysis.

2.1 Subjects of responsibility, or: who is responsible?

To qualify as a subject that can bear responsibility, an actor has to meet certain criteria. Criteria frequently discussed in this context include having agency, having the possibility to achieve alternative outcomes, and being aware of one’s actions consequences as well as being able to evaluate them [16,17,18]. As outlined in the following, in the context of the research question of this paper, especially the allocation of agency to the individual, group or network is a central issue.

Researches concerning AI systems and the development of AI systems are endeavors that are not driven by single individuals but by a multitude of actors. From basic research, to applied research, development, deployment, and use of AI systems, a great number of actors can be considered potentially responsible for problematic outcomes. For instance, Dignum [11] raises the question of who is responsible if a self-driving car hits a pedestrian and lists several candidates such as the producers of the hardware (such as sensors), the developers of the software, the authorities that allowed the car on the road, or the owner of the car. Moreover, referring specifically to the software development aspect, Coeckelbergh [15] emphasizes that “there may be a lot of people involved” in some of these processes.

This circumstance is often conceptualized as the ‘problem of the many hands’ which poses difficulties for the traditional view that individual human actors can be held responsible for the outcome of their actions [19]. As Nissenbaum [19] notes in the context of computer systems more generally, in many cases, there “may be no single individual who grasps the whole system, or keeps track of all the individuals who have contributed to its various components.” Referring to AI systems specifically, Floridi and Sanders [20] argue that such circumstances “pose insurmountable difficulties for the traditional and now rather outdated view that a human can be found accountable for certain kinds of software and even hardware.” This raises the question if responsibility in such cases can be assigned to institutions or entities constituted by a multitude of actors (such as a collectives or organizations), or whether, contrary to Floridi’s and Sander’s view, responsibility can always be assigned solely to singular individuals.

Various types of entities constituted by more than one actor can be considered as being involved in the development of technology such as AI systems: organizations such as corporations, universities, or other institutions, goal-oriented collectives (cf. [21]). However, scholars rejecting the notion of collective responsibility (for actions) argue that in cases in which several individuals act in concert, the responsibility can or should be assigned to the individuals that constitute the collective entity based on their individual actions or contributions instead of the collective entity itself (see e.g., [22, 23]). As such positions suggest that collective responsibility can be reduced to individual responsibility, they are described as reductionist or individualistic [14].

Relating these aforementioned theories to this present research, questions about individual and shared responsibility will be asked to see if respondents of this study might concept diminish their personal responsibility and refer to collectives or networks that share responsibility, since basic research is typically situated in a larger system: co-authors, citations after publications, results that are in many ways usable (i.e., dual use) etc.

2.2 Objects of responsibility or: being responsible for what?

Every concept of responsibility requires an object of responsibility, i.e., there needs to be something (or somebody) that the responsible actor is responsible for. This object that an actor is responsible for can be of various types, such as actions, events, persons, objects, and others [14]. In the context of research concerning and development of AI systems, especially the responsibility for the expected future outcomes, i.e., research findings and potential uses of these findings in the design of AI systems, is relevant.

With increasing complexity and possibilities of modern emerging technologies, contemporary science and engineering become characterized by growing uncertainties regarding expected future outcomes that are of the scientists’ and societies’ concern [24]. As the outcomes of research and engineering do not “substantially pre-exist” [24], their existence is rather reduced to expectations and visions regarding their future shape and consequences they may cause once they are developed and deployed. Hence, when dealing with objects of responsibility regarding development of science and technology, and basic AI research in particular, it is often referred to in prospective terms [25].

To elaborate, sociology of expectations is a branch of literature that examines the role of prospective claims and expectations of the future in scientific and engineering practices [24, 26]. Prospective claims can have the form of expectations, i.e., “real-time representations of future technological situations and capabilities” [24], and visions, i.e., a “fuller portrait of an alternative world” [26]. Alternatively they may also take the form of promises that refer to the benefits which may follow from science and technology development or concerns that, in contrast, stress likely risks [27]. Furthermore, sociology of expectations stresses that claims about the future are the basis for negotiation and taking decisions about further directions of technology’s development, engaging in the research activities, supporting the innovation process, and even developing the policy frameworks [24, 28,29,30]. As prospective claims can concern both, the shape and features of future technological artifacts, as well as the wider picture of technological and—relatedly—societal development, future claims can be also a base for the ethical assessment of the technology [31, 32].

Regarding the question of how responsibility can be assigned based on future claims, philosophical literature discusses two possible perspectives. On the one hand, there is the question to what degree responsibilities can be assigned ex ante to researchers and engineers to ensure that rather desirable outcomes than (morally) problematic outcomes are achieved. This type of ex ante responsibility is often discussed in terms of obligations, which are “tied to specific roles” [33]. In the context of research and technological development (of AI), roles can be defined, for instance, by profession, highlighting the role of professional ethics and profession-specific codes of conduct. Furthermore, obligations can be assigned by regulatory authorities. For instance, the proposal for the AI Act by the European Commission [34] assigns the providers of AI systems, that is, the actors that place the system on the market [35, 36].

On the other hand, there is the question if responsibilities can be assigned ex post to researchers and engineers, in case a given problematic (or desirable) outcome should manifest in the future. This type of ex post responsibility is often discussed in terms of blameworthiness (or praiseworthiness) and—in the legal realm—liability. In the case of the attribution of ex post responsibilities for outcomes that relate to actions of AI systems, there needs to be a causal link between the actions of the person that responsibility is attributed to and the outcome of the action of the AI system. As Coeckelbergh [15] notes, “in the case of technology use and development, there is often a long causal chain of human agency [and] in the case of AI this is especially so since complex software often has a long history with many developers involved at various stages for various parts of the software.” While AI researchers contribute to how AI systems “will behave and what kind of capabilities they will exhibit” [11], the ‘causal link’ to outcomes of actions of AI systems is more indirect than is the case with some other involved actors such as developers of end-user applications or users.

It should be noted that ex ante responsibility and ex post responsibility are often intertwined. For instance, blame for the occurrence of problematic events is often assigned based on that actors have insufficiently fulfilled their obligations. Thus, in many cases, ex post responsibility is conditioned by the degree of fulfillment of the existing ex ante responsibility, e.g., in the form of obligations [14].

Lastly, claims about the future are associated with uncertainty. Especially in basic research, most practical and societal impacts with ethical import are going to become visible only in the distant future. Indeed, as Brey [9] mentions, technologies that are in the early stages of development are characterized by high degrees of uncertainty concerning their deployment and societal effects. Therefore, in basic research, making predictions about the impacts of future technology are difficult to make and steering research in a direction that leads to desirable outcomes is difficult to do (cf. [37]). In research on AI, an often discussed issue relating to this uncertainty is that many AI systems (or underlying ML models) are applicable in various contexts. Therefore, research on or the development of a system or model in one context may be used in a different context by other actors later on. For instance, Coeckelbergh [15] argues that facial recognition systems developed in the medical sector could be used for surveillance purposes later. Thus, especially in research on AI, there is a high degree of uncertainty relating to the impacts of future technology that is already discussed in AI ethics.

2.3 Field work on AI responsibility

As mentioned in the introduction, there are already some empirical studies describing how developers and practitioners involved in the development and use of AI systems negotiate their responsibility and attempt to act responsibly in practice. For instance, Orr and Davis [5] conducted interviews with AI practitioners to analyze how these practitioners attribute responsibility across actors. Their study shows that AI practitioners do not have any trouble understanding the potential negative social effects of their work and more generally within their sector. However, determining the subject of responsibility was seemingly difficult. This latter observation is also shared by Shklovski and Némethy [8], as the authors mention how the AI practitioners they interviewed during a hackathon had many open questions regarding “who or what should be held accountable if unwanted outcomes were to emerge and how this ought to be accomplished”. The authors mention how much of the work of AI practitioners is marked by uncertainty, and therefore need spaces for dialog and discussion, in combination with so-called “nodes of certainty” where certain elements of AI ethics could be seen as semi-stable reference points (such as certification and documentation). Both studies [5, 8] indicate that AI practitioners face uncertainties about issues of responsibility.

In another empirical study on AI responsibility, Griffin et al. [7] show that responses of AI developers in terms of their agency are rather diverse, thereby calling them ethical chameleons: “highly skilled practitioners whose ethics are largely adapted from whatever industry employs them, and a moral bright line that shifts from practitioner to practitioner”. This, however, might be also due to their sampling strategy, as they studied a rather heterogeneous sample without much overlap in socio-demographic characteristics or work-related content (such as sectors). Bearing this in mind, the present study samples research projects within the same organization, all with the aim of trying to create AI with basic research on intelligence, as is explained next.

3 Method

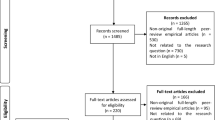

To understand how researchers in the field of basic artificial intelligence perceive their responsibility, focus groups are conducted. Focus groups as a qualitative research method is chosen because it allows for the study of perceptions of several respondents. Compared with individual interviews, focus groups have the added advantage that respondents can elaborate on each other’s opinions, which in this case is essential since projects are sampled that consist of several members. Thereby, the respondents share work-related experiences in their teams, and are able to elaborate on them during the interviews.

The sample consists of researchers working in an interdisciplinary and inter-university research cluster in Germany that specializes in basic artificial intelligence research. This particular research site was chosen for the relative ease of access due to the network of the authors of this paper. In other words, a convenience sampling strategy was chosen. This means that the authors of this paper have a dual role: they are both interviewer (i.e., researcher) and coworker. While this enables building rapport more easily than in other interviewing contexts, it, however, also means that the roles of coworker/interviewer needed at times to be more pronounced by, for instance, cutting banter and other off-topic remarks short during the interviews. Furthermore, within that same institutional setting, the results are used for internal feedback. While this might suggest potential friction between research interests and organizational interests, to foster proper scientific conduct and a solid reflection on ethics for the organization, the content of the results is not modified or censored in favor of its institutional context.

This study discusses one institutional case where people conduct basic research, and findings are not generalizable beyond the context of this institution. Rather, the results could signify a starting point for future research to expand on. Within this research cluster, a total of 8 projects are sampled (out of approximately 40 projects that were running at the time of sampling). Each focus group represents one project, with the exception of the pilot which included members of two different projects, resulting in a total of seven focus groups in total. The pilot was conducted first to define the scope of interview questions. Insights from the pilot are also used in the results because similar questions about responsibility with respondents from the same institution are used. The projects are chosen based on the different aspects of intelligence research they cover, which is mostly computer vision and robotics in combination with expertise from other fields about human and animal intelligence, thereby consisting of interdisciplinary teams of researchers. The specific AI-related fields these projects are situated in are summarized in Table 1.

In total, n = 21 respondents are included in this study, with 9 female and 12 male participants. The group composition reflects all members of a specific research project. Following this logic, the composition represents a mixture of academic seniority: doctoral researchers, postdoctoral researchers, and professors. This sampling strategy is chosen, since all members work toward the same goal, and thereby could reflect on their sociotechnical expectations and visions of their shared project. In discussing responsibility, shared experiences could then be easily brought up. Nonetheless, this sampling strategy has a drawback, as the level of seniority is able to influence the responses. A Ph.D. candidate for instance might not speak as freely when their supervisor is around, as compared with an interview among peers of the same academic level. The group composition is shown in Table 2 and consists of 2–4 interviewees per focus group. To anonymize responses of the interviewees, pseudonyms are used. Also, the gender composition per focus group is not revealed since certain focus groups are female dominated and it therefore within the organization would not guarantee anonymity in an otherwise male-dominated environment. Most pseudonyms given are, therefore, gender neutral.

The focus group interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide, that is constructed based on the theoretical framework. The focus groups were held and recorded via the video conferencing platform Zoom due to logistical constraints that emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic. The interviews lasted approximately 90 min and were conducted in English. The answers of the respondents were transcribed and thereafter analyzed. The transcripts and results do not show pauses, intonations, or non-verbal information. The exact data used, therefore, are the transcripts, where the verbal responses are documented. After cleaning the data, a thematic analysis, which is a method of analysis in qualitative research that refers to understanding the general patterns of the researched phenomenon inductively [38], was conducted. The analysis served the purpose to establish themes related to the concept of responsibility, and therefore the content of the answers was analyzed on a descriptive level and not for instance on a semantic or discourse level. Also, group dynamics is not the unit of analysis for the results, but rather the themes that emerged that refer to issues and definitions of responsibility.

Reflecting on the positionality of the authors/researchers of this paper, all three authors, consisting of one philosopher and two sociologists, were involved in creating the interview guide to foster precision between translating the sensitizing concepts into interview questions. Thereafter, the two authors with a sociological background handled the data. One of them oversaw the data cleaning by first having the data transcribed and checked by an external organization, and then double proofreading to ensure accuracy. The other sociologist on the team of authors with a more senior position conducted the analysis. MS Excel was used to manage and analyze the data. The analysis is a three-stage process of open, axial, and selective coding [39, 40], as is explained next.

The first round of coding involved marking text in the transcripts that refer to issues of responsibility. Thereafter, all these marked texts were put into an Excel sheet dedicated to a specific focus group. Once all relevant pieces of information concerning responsibility were established and placed into an Excel sheet, tentative descriptive open codes were created. These codes were not final in their description, nor were they fine grained. Instead, they represented the first step in organizing the data according to open codes. Examples of such codes are ‘duty/proper science and researcher’ with the text from the transcript “You just need to work” or “I sometimes find myself struggling in our project, and I then find it very helpful [sic] when I read more”. In total, 18 descriptive open codes were established. After placing all pieces of text in the cells of the respective focus group sheet and labeling them with an open code, the second phase of the thematic analysis started, i.e., axial coding. In this phase of coding, all the descriptive open codes were put into a new Excel file, and color coded to indicate how specific codes overlap and what they have in common. In total, six axial codes were identified. To give an example, the open codes established in the first round of coding: “doing more research”, “duty/proper science and researcher”, and “self-interest”, all relate to the individual role of the researcher, similar to enacting (or disassociating) with certain virtues. Therefore, these three open codes were assigned a particular color and given the axial code “virtues”. In the final step, broader patterns were identified by comparing all the axial codes, thereby creating selective codes. In this step, the six axial codes were reduced to three themes: time, limiting sociotechnical visions, and many players in the field. To give an example, the theme “many players in the field” consists of axial codes that refer to people and other subjects of responsibility, such as the codes “constellation of actors”, “not us”, and “virtues” where issues of agency (and the lack thereof) are discussed in relation to the different players in the field.

4 Findings

When respondents were asked about responsibility in fundamental AI research, three different themes were found: the restricted aspects of sociotechnical visions, time and responsibility, and the many players in the field. The theme “restricted aspects of sociotechnical visions” refers to the object of responsibility and how, for the respondents, it is difficult to define what they are responsible for. The “time and responsibility” theme refers to how time shapes responsibility according to the respondents. Last, the “many players in the field” theme refers to how respondents articulate the problem of the many hands when determining who or what is responsible for potential consequences of their work. All strands of thought are explained next. It should be noted that all names attributed to the respondents are pseudonyms, and italics are used for emphasis.

4.1 Restricting the boundaries of sociotechnical visions

When asked about future consequences of their AI systems, respondents had a hard time imagining how their work could make an impact in the real world. Most respondents see their work as basic research, in which they try to investigate principles of intelligence and apply these principles to create supposedly intelligent technology. When asking what that means in terms of contributions, such as best- and worst-case scenarios in their field and in applied societal contexts, the answers to their visions had boundaries that would restrict their sociotechnical understanding of responsibility of their scientific work. To elaborate, respondents specified how their work could contribute to changes, either incremental or foundational, that would improve a model, method, or AI system, but typically did not specify what effect this might have on a societal level. When asked what the best-case scenario is in relation to their project, Lee answered:

“I’m an empiricist, so I do empirical work and experiments, and we do a lot of trials, and waste a lot of time, often on conditions that aren’t super informative. And finding conditions that are most informative, while using the time that you have in the lab, because it’s also limited working with people, working in conditions where we might want to put them in the dark, maybe push their eye muscles passively or something like that, which is really unpleasant. So, all of these things limit the time that we have. And so, ideally, we would have an integration of predictions from a model and empirical work. That would be a nice outcome. But that is not society. I don’t know if we’re just talking about society” [Lee, Professor].

The respondent in this example mentions how the best thing that could happen with the project is to have a better integration of experimental work and model predictions, and also to reduce the hassle of experiments. The respondent does not consider this to be necessarily a societal benefit. This example illustrates that defining how their work translates into society is not a straightforward activity for the respondents. In their sociotechnical visions, they rather stick to incremental changes within their field to better their scientific discipline or technological artifact. Even in cases where sociotechnical visions are more clearly defined, e.g., a project where respondents envisioned their robots to be applied in care contexts, “success” was defined in terms of small iterative steps that do not necessarily immediately lead to successful real-world applications:

“Yeah, I think we’re really far away from it [application]. So, we have to start really with the basics. So, I think even a few successful steps, I will deem already like a really big success of our project, it will be definitely a continuous project from my perspective, to an iterative process to keep improving the robot and keep seeing how it affects interactions before we can ever get to introducing the robot to patients” [Alex, Postdoc].

So, although the researchers already defined that their project on social robotics should have a specific future scenario in a care-related context (the word “patient” was used), still success is defined in terms of an ongoing process that involves incremental changes.

In addition to mentioning incremental changes as the best outcome that could follow from their work, respondents found it difficult to define what they are responsible for because they see their research far from practical use, as their academic research does not concern end-user applications. The effects are seen as delayed as they view their work only having societal implications when picked up by others. When asked about the best-case scenario that could unfold as a result of their work, Madison replied:

“We’re not building the self-driving Tesla here. And this is not my ambition. Like, that’s not what I want to do. I mean, I’m happy with doing this basic research here that we are contributing our part to something that in 10, 20, 30, 50 years, you know, that’d be fruitful, but not within my PhD. And my wildest dream is just to gain some interesting insights into human cognition, also how to adapt to neural networks. That’s my wildest dream, even if it’s like really small” [Madison, PhD candidate].

To give another example, MacKenzie mentioned:

“I want to comment on the, like technological impact, that the impact after the project immediately, is probably not going to be that strong, because also we are on the research level. So I think it depends on like how something impacts society, if it’s actually widespread by industry like if someone is actually using these results. It’s hypothetically possible that it would impact like maybe in five years, but it doesn’t depend on our project entirely” [MacKenzie, PhD candidate].

In other words, researchers doing basic research to create AI limit their ambitions by not focusing much on the societal implications of their work. When articulating effects of their work, respondents mentioned it is typically manifested with a delay. This temporal aspect of responsibility is elaborated on next.

4.2 The “when” of responsibility

Not only did the respondents describe how they are just one small piece of a bigger field and community, responsibility was conceptualized in terms of time: the when of responsibility. Time was seen as a subject in itself influencing the outcomes of their work as well as the work process. The latter could be seen in terms of a timeline (i.e., their work and subsequently their form of responsibility has a temporal relevance).

Respondents view time as a factor that shapes the eventual design and end use of the technology. There is a sense of inevitability: at some point, something unethical is going to happen anyway, so they might as well do the work themselves instead of letting others do it. Typically however, the “inevitable” non-ethical outcomes are ascribed to external others. This is best illustrated with the following quote from Sam:

“Maybe, do you know the drama, ‘The Physicists’ by Dürrenmatt? So I had to read this early on in high school and not sure if that caused something or it just resonated with me. So it’s a satiric drama about the nuclear bomb and so on. And I think if I'm not wrong, Charles [pseudonym of interviewer] correct me, but the essence of it is like what is thought or what can be thought will be thought and there is no way of taking it back. And it's a very dark perspective, like many of these Swiss writers had at least back then. But I think there is a truth to that right? I mean, okay now I'm drifting completely away here. But you can also think of it as a game theoretic problem where just anyone can cheat right? So if you have 100 scientists or engineers, and 99 are fine and try to avoid doing the wrong thing, it's enough if there is one who does the opposite right? And then the others have to react. That's my very dark perspective.”

Interviewer: “So it's inevitable?”.

“Yes, I'm not saying it's a complete laissez-faire, and then you now work with the military if you want. I'm just saying, okay if we can prevent it for us, you know, so I look at me and I talk to you and we agree let's not do this, there will always be someone who does it, right? So that's my point. I'm not sure, like, what that means ethically now on a higher level, but my perspective is a bit dark there. So I'm not saying you should not care. I'm just saying it’s unavoidable’’ [Sam, Professor].

Similarly, when asked about how to mitigate or prevent negative uses of their work, Adrian answered that it is “only a matter of time” before others outside of academia make use of their work:

“You could try to limit. I mean, no one would do that, no real researcher would do that, I mean, purposefully limit the scope of your findings, in a way. I mean, you could say, okay, this is a very, very specific system, and it exclusively works under these and those circumstances, so to make it harder to actually transfer it. You might still contribute to, like, a small portion of the academia that you’re part of. So, like vision science, it might bring that field forward, but I guess, it's only a matter of time, even if you actively try to keep people from reusing your stuff, or transferring your stuff, that people will do. I mean, because in the end, there are also a lot of smart people, outside of academia, who constantly think of applications, or how to make money out of knowledge. And we can’t blame them” [Adrian, Postdoc].

To give another example, George mentioned that once their work is openly communicated, it is a “natural outcome” that others would make use of their work once it is openly accessible, albeit in a non-beneficial way.

“Yeah. I guess, I also am a bit pessimistic on that side as well. So, yeah. Again, I guess, if we publish something, if we make something open, then we should accept the outcome, right? So anyone can use it. So if we are okay with that, then we need to publish. If we are also concerned about, okay, what if a military person read our paper, or I don't know, anyone's paper, and then make use of it in a dark, I don't know, as a dark usage. So that’s the price we need to, I don't know, it's not that we need to pay, but it's the natural outcome of it, to have an open publishing” [George, PhD candidate].

Time was repeatedly mentioned as a factor that influences the work of the respondents. Not only in terms of inevitable unethical outcomes that are picked up by others, but they also described the process of their work in relation to responsibility as being influenced by time. Respondents mentioned how responsibility depends on the timeline and life cycle of their work, and consequently their (lack of) agency in shaping AI technologies. The discussants answered how at first, there is little information on how beneficial their work is, or at least assume nothing too bad will come out of it, ultimately making it difficult to judge ethics and responsibility. As stated by Bob:

“Often in science, lots of results are produced where it's not visible what could be benefits, and some of them never any benefits arise, I guess. But that's part of the process and doing that is still beneficial, because at some point there is a beneficial application. So, when is AI research beneficial? Only really in the end, but to get to the end then lots of non really beneficial steps have to be made” [Bob, PhD candidate].

Furthermore, when asking about their individual role in shaping beneficial outcomes to the AI, Stephanie said:

“Well, speaking for myself, I would say none, absolutely none. I'm thinking about these things typically alone, or you know, when I talk with friends about what I'm currently doing. No role at the moment. But I think and that also relates to what we all just said that we are just in the beginning of trying to understand what we need for successful human robot interactions and so on. But at some point, there will, probably those people who do that and who try to build such a robot should think about that some more. But at the moment, I for myself to say I have no role in that whatsoever” [Stephanie, Professor].

Interestingly, when their work is more mature, responsibility is shifted toward users and other external actors. In other words, whereas in the beginning, respondents find it difficult to define their specific role that leads to (un)desirable outcomes or at least do not assume terrible consequences, once their work is published, their perception of responsibility relates to other people who shape the ethics of their work. For instance, the theme of dual use came up during the interviews in which non-intended effects of the respondents’ work became clear. Jaime mentioned:

“I mean, at the beginning, I think everybody, all researchers think that their project contributes to a beneficial thing. Later on, I mean, at this stage, no one knows [pause] Sorry. No one knows who will use our data in the future or what research question. So, there's always the possibility that it may be somehow abused for something we would not like to support. So, I find it really hard, this question” [Jaime, Postdoc].

In other words, when asking about responsibility, respondents differentiated between early project work, and consequences of finished work. During the early phases of basic research, it is unclear what respondents are responsible for, whereas after publication respondents mention how others have the agency to mold their work into something that does not always align with their values. Not only does this refer to an element of time: i.e., responsibility is seen from the lens of when it happens in the timeline of their work, it also shifts responsibility from researchers to users as is elaborated on in the next paragraphs.

4.3 The many players in the field

The idea of dual use was earlier discussed in relation to the timeline of responsibility (i.e., researchers claimed it is difficult to estimate their responsibility in the beginning phase of their research, as it could only be assessed once it is more mature), but it also has to do with who is responsible. Dual use implies that some responsibility lies with other actors interpreting and using the work of the AI researchers in different ways than initially intended. In the following example, Daniel not only refers to other people misusing scientific findings for their own (unethical) benefit, but also implies that it has to do inherently with sharing information:

“I mean, people have made ethical issues all over science, by publishing results that other people could use to make arguments that we would consider unethical, right? So is the act of sharing an insight that could cause problems in a societal debate, is that already an unethical act to share that information?” [Daniel, Professor].

Similarly, Noah talks about the consequences of sharing their results openly:

“And, yeah, definitely, many companies use this kind of research we’re doing without us even knowing that they use that. Because more or less, we provide our results very open. And so yeah, I could imagine that many people use parts of all the things we discuss here to make their products working or better or improve them. It’s not just researchers that, yeah, can use our work to facilitate their own research, push their questions farther, but I couldn’t imagine all the companies doing so” [Noah, Postdoc].

These quotes illustrate a perceived lack of agency: the participants know they are contributing to a field but ultimately, others are able to mold their findings according to their liking. Furthermore, the latter quotation shows that respondents were pinpointing specific actors that they think hold responsibility as a subject, in this case companies. However, the list of actors mentioned in relation to being responsible for sociotechnical outcomes is rather eclectic, for instance but not limited to: the media and public discourse, governments and politicians, project team members, individual researchers, and companies. The following example shows how respondents not only name players who can (mis)use their work, but also how it is interconnected to their agency. When Spencer stated how their work on facial and emotion recognition eventually could be used by governments and companies, Jessica replied mentioning how it, therefore, is all the more relevant to do their own research:

“(…) Of course, a PhD thesis doesn't necessarily change the whole game. On the other hand, a single group does not because it's the other group that's more powerful and does the important things and your research is never really cited and that's why it doesn't have a big impact. But that's a small excuse. It is rather that all these things contribute to the state of the art in the domain of artificial intelligence, and systems become more capable. And these little components in the end contribute to the overall systems, that those systems contain surveillance cameras in all the street intersections in big cities in China, and then people can be recognized, their feelings can be interpreted smartly. They can be matched with personal database, and then the individuals are under full control of a government, not necessarily the German government, but maybe it’s the German government in five years from now, you'll never know. And if you are skeptical, then there is reason to be skeptical because these things, we see, it happens all over the world all the time. And well, depending on how you look at it, some among us are already horrified by ever more young people using social media and allowing those companies to track their data to collect data, and hardly anybody is able to do to have an overview of what these data collections are, and how you could individually step out of the system and not send your data to the companies any longer. And inside of that one is such a little research output as well. And it makes the system more perfect” [Spencer, Professor].

To which Jessica responded:

“On the other hand, it's maybe also not a good idea to leave it up to these private companies or social media companies to maybe just develop similar things themselves. And yeah, because they might, and then if it's at least like researchers like us, then we can make like legislation aware of responsibilities… Yeah, to increase awareness of what could happen to people's data. And because Facebook already has then the full profile, the full knowledge of a person, and they, if they, if they heard this with the facial recognition, it's extremely powerful I imagine but this shouldn't be only in the hands of these huge private companies” [Jessica, Postdoc].

The later statement by Jessica illustrates the perceived agency that researchers do have and recognize, as opposed to the so far discussed findings that refer to the lack of perceived agency in the field of basic AI research (e.g., with time influencing their work, and others misusing their work). In addition, results show that respondents do have some form of awareness of their personal responsibility in relation to their work. They typically refer to particular obligations and duties that researchers should enact such as good work ethic, communicating science openly, and conducting experiments ethically. For instance, George stated that to steer their work for beneficial future applications, it simply boils down to work ethic:

“You just need to work. (…) So I sometimes find myself struggling in our project, and I then find it very helpful when I do it, is to read more. So sometimes I find myself not knowing the things that I need to know. Then it takes me some time to, I don’t know, to learn to read more and to I don’t know, explore more. So that’s something that I usually go back and forth from doing something, then reading and learning and going back” [George, PhD candidate].

To give another example, when asked how they see their personal responsibility in relation to their work, Kim who conducts experiments with humans and robots mentions the importance of conducting experiments properly, and also anticipates such procedures such as regulations to be helpful for deployment:

“I assume at some point, people will discuss these points and come up with some regulation on how to do this kind of research and how to apply this research. So, as we do research with humans, there was a lot of discussion on what is the best way and transparent way to do research with humans. And to adhere to like ethics and moral principles. And we have a lot of regulation that we need to follow in doing human studies, there will be also regulation in how we can deploy robots into society. And what kind of robots we can build or not” [Kim, Postdoc].

To summarize the theme of the many players in the field: though there is an emphasis on doing “good” research on one hand, and on the other, there is a recognition there are external forces, companies or people that intervene with the implications of their work. The identity of the researcher as a bearer of responsibility thereby gets fuzzy and unstable: while there is the acknowledgment of some form of autonomy, there is also a lack of agency and sense of helplessness simultaneously. To quote Spencer:

“(…) It’s not the little contribution in one research project that really makes a difference. We are all contributors and victims and witnesses of this overall large development. And still, the individual behavior can make a difference. And I believe, if we are turning into vegetarians or don’t drive cars anymore, that makes a difference. After all, it makes a difference” [Spencer, Professor].

5 Discussion

The results of this case study show that respondents have a difficult time to explain what they are responsible for, and who exactly is responsible for such (undefined) outcomes of their work. In part, according to the respondents, this has to do with the nature of the field they are working in: it is difficult to imagine how their work travels outside of academia when they are trying to understand basic principles in intelligence research, and who exactly is responsible for potential outcomes when many different actors are involved in this process of the creation, dissemination, and deployment (including the elusive factor of time). Indeed, uncertainty seems to be the main thread when asked to reflect on different aspects (i.e., subject/object relations) of responsibility. This chapter discusses the theoretical and practical implications of these results as well as the paper’s limitations.

5.1 Theoretical implications

In terms of the question of who is responsible for the impact of AI systems on society, the results highlight that participants recognize that there is a multitude of actors involved in the development, governance, and use of AI systems. Because of the various ways that other actors can use the research results after they are published, the participants articulated a lack of control they can exert as basic researchers. However, while highlighting the involvement of other actors clearly served to reject responsibility away from themselves, there was no clear pattern regarding who they considered responsible instead: individual actors responsible for problematic uses of their research results, all actors involved in research, development, use of AI systems jointly, or society at large. Thus, the participants (as a whole) did not position themselves clearly in the discourse about whether responsibility can be distributed among the many actors involved in AI systems, or whether it can always be assigned to individual actors for their individual actions. The participants merely emphasized the importance of the actions of others for their own responsibility. According to the participants, their responsibility is diminished or negated by the actions of other actors, over which they do not have any control over as basic researchers (especially after publishing their research results).

Yet, while the participants do not indicate if and how responsibility can be distributed among the actors involved in the development and use of AI systems, their references to the development timeline allows conclusions to be drawn about how their agency relates to that of other actors and what this means for the allocation of responsibility. The participants considered their work in basic research to be at the very beginning of the development timeline. At this stage, the participants had difficulties envisioning how their work could make an impact in the real world. In their view, the impact on the real world—including problematic outcomes—only manifests due to activities which happen later in the development timeline based on their research findings. For the most part, the possibility of controlling this impact as basic researchers, which could justify assigning responsibility for it to the participants, was rejected. Following this line of reasoning, most of the responsibility for problematic outcomes would have to be attributed to actors further down the development timeline (or even to actors involved with AI systems after development is complete, such as users). This view aligns with recent European policy proposals. For instance, as mentioned in the Theoretical Foundations, the proposal for the AI Act by the European Commission [34] assigns the majority of obligations to providers of AI systems, that is, the actors that place the system on the market (see also [35, 36]).

While some participants emphasized the role of other actors who use the research results to—consciously or unconsciously—bring about such outcomes, other participants expressed a more deterministic view, according to which problematic outcomes happen necessarily in the future. This view on the control of other actors over bringing about or preventing problematic outcomes has an impact on whether these (other) actors can be held responsible for them. If these actors have control over outcomes, there is (under certain circumstances) the possibility of assigning responsibility for these outcomes to them. If the outcomes occur necessarily, there is no basis for assigning responsibility for the outcomes to any actor. However, both views emphasize the “othering” of responsibility: there are other human and non-human (i.e., time) elements that influence outcomes, i.e., diminishing their own agency.

Although the participants recognize little ex post responsibility for themselves, the picture is different with respect to acknowledging ex ante responsibility in the form of duties and obligations. Since taking such responsibility does not require control over outcomes, but only over one’s own actions, this form of responsibility was more readily accepted by the respondents. Indeed, as outlined in the results, the respondents are aware of their personal responsibility in relation to their work and highlight particular duties and obligations that researchers in basic research should fulfill. This can be understood as an acknowledgment of ex ante responsibility, which is associated with their role as researchers.

Furthermore, in the case of ex post responsibility, the results of this case study show how respondents of the studied institutional context are uncertain about both the subject and the object of responsibility. When reflecting on previous field work on responsibility in the field of AI ethics, Shklovski and Némethy [8] would argue that such uncertainty and not knowing is inherent to AI ethics: doubt is part of the process of making ethical decisions and thereby ethical AI. Nonetheless, what is different from previous field work is that specific to basic researchers of this institutional context is the lack of sociotechnical visions or imaginaries. Whereas Orr and Davis [5] mentioned that it is easy for AI practitioners to understand what they are responsible for, this study showed that this is not the case for the interviewed basic researchers of AI systems. The respondents in this study mentioned repeatedly throughout the interviews that they are in the phase where they try to uncover general principles and try to implement them into technologies. Thereby, the level of technological maturity, which in the case of foundational research is practically proverbially equivalent to genesis, makes it difficult to understand what they are responsible for.

This shows that, in this particular case, technological maturity and readiness levels matter when discussing AI ethics. Different from developers who engage in applied and deployed AI [5], the basic AI researchers approached for this research face difficulties when confronted with questions about possible future outcomes of research projects in a broader social context. While the results of this study are not generalizable due to its methodological constraints, moving forward one could study how readiness levels and technological maturity are factors that should be accounted for when discussing responsibility. For it is common practice in the social sciences and AI ethics as fields to acknowledge that one should be sensitive to the contextual nature of the artifact and the people who make it.

5.2 Practical implications

While it should be questioned whether these results are found in other institutional contexts where researchers conduct fundamental research on AI, the implications of the results for this institutional context reads as follows, and could be discussed in future studies. To enable basic researchers to fulfill the ex ante responsibilities that are recognized by the participants, tools can be made available to them. A key aspect of taking responsibility for basic research is that information about the research process and the research results is systematically communicated to the actors who will be able to exercise control over later stages of the development process. This applies to other researchers building on the research results, as well as to developers and users of end-user applications and regulatory authorities. The information can help these actors to ensure the development and use of AI systems in accordance with ethical values. Depending on the nature of the research, these outreach efforts may take different forms. To give an example, to provide information on datasets generated in basic research, researchers could build on the work of Gebru et al. [37], who developed standardized forms for providing information about the genesis and properties of datasets. Developing such tools is what Shklovski and Némethy [7] refer to as “nodes of certainty”, in which AI ethics is in part being translated into particular practices that engineers and computer scientists are familiar with. To make an analogy, in the sea of uncertainty of doing basic research, such tools enhancing ex ante responsibility could function as islands with beacons where they can orient themselves to if needed.

Specifically in this study, one can think of expanding on the ethics toolkit that is available to the researchers with, e.g., the example given earlier of Gebru et al. [41] in relation to ex ante responsibility, and the so-called “modes of certainty” that Shklovski and Némethy [8] refer to. However, one could also see the lack of sociotechnical visions as a sign for more intervention. As STS literature stresses, reflections on possible outcomes of the research appear to be a critical issue when developing emerging science and technological fields [24]. The assessment of visions and possible negative outcomes help to address potential risks at an early stage [27]. Going one step further, according to Konrad et al. [26] expectations and visions when articulated at the early development stage act are not mere descriptors of anticipated future events but act performatively, i.e., thereby may help to steer the technology in the socially desirable directions [42,43,44]. Future studies thereby could more closely examine how basic AI researchers could benefit from anticipatory ethics [9] and technology assessment approaches that provide frameworks and methods to address multifaceted aspects and ambiguities connected with future developments of technology, such as Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) and Anticipatory Governance [44,45,46].

5.3 Limitations

It should be noted that there are a couple of limitations to this study. First of all, the most notable limitation is linked to the sampling and resulting methodological bias in this study. The focus groups composition reflects all the members of a research project, regardless of academic level/seniority. While this was a deliberate and theoretically informed choice, the different levels of seniority most likely have influenced group dynamics as professors and their postdocs and PhD students were sharing their opinion in a shared space. In other words, the hierarchical nature of people’s position in the organization might have influenced if, when, and how people spoke during the discussion. Furthermore, this study did not exhaust all topics relevant to responsibility such as legal liability or the relevance of technological determinism and non-human actors when constructing new technologies. Finally, occasionally (but rarely) there were technical difficulties, resulting from having to conduct the focus groups on Zoom. These were typically resolved quickly, but nonetheless disrupted the flow of conversation, and affected the recordings and transcripts.

6 Conclusion

This paper raises the research question of how AI researchers doing basic research on AI perceive their responsibility, as especially basic research of AI in particular is characterized by much uncertainty about effects and consequences. After conducting a case study with 7 focus groups consisting of 21 respondents, results show that responsibility is an elusive concept to grasp for the respondents as the sociotechnical visions the respondents mentioned were stuck in a form of abstraction that does not necessarily refer to social or societal consequences. Furthermore, time was mentioned as a factor that informs their view of responsibility. In that regard, time was seen as a factor that shapes the outcomes of their work, thereby diminishing their own agency. Finally, in addition to time, other players in the field were mentioned that were seen as influencing their work and its outcome and thereby also carrying responsibility. These difficulties in defining ex post responsibilities signify the importance of being aware of how readiness levels and technological maturities matter for understanding responsibility specifically and AI ethics generally. Currently, fostering responsible research of basic AI could entail expanding tools typically related to ex ante responsibility, such as guidelines for documentation practices. Further research could examine how RRI and anticipatory ethics and governance could help in developing measures for ex post responsibility. Also, due to the nature of qualitative research employed in this case study, it should be further studied how generalizable the findings are across other institutional contexts where researchers perform basic research.

Data availability

Data not available due to ethical restrictions.

References

Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 1, 389–399 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2

Fjeld, J., Achten, N., Hilligoss, H., Nagy, A., Srikumar, M.: Principled artificial intelligence: Mapping consensus in ethical and rights-based approaches to principles for AI. Berkman Klein Cent. Res. Publ. (2020). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3518482

Adadi, A., Berrada, M.: Peeking inside the black-box: a survey on explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access. 6, 52138–52160 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2870052

Lucivero, F., Swierstra, T., Boenink, M.: Assessing expectations: towards a toolbox for an ethics of emerging technologies. NanoEthics 5, 129–141 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-011-0119-x

Orr, W., Davis, J.L.: Attributions of ethical responsibility by Artificial Intelligence practitioners. Inf. Commun. Soc. 23, 719–735 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1713842

Di, D.: Ethical ambiguity and complexity: tech workers’ perceptions of big data ethics in China and the US. Inf. Commun. Soc.Commun. Soc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2023.2166357

Griffin, T.A., Green, B.P., Welie, J.V.M.: The ethical agency of AI developers. AI Ethics. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00256-3

Shklovski, I., Némethy, C.: Nodes of certainty and spaces for doubt in AI ethics for engineers. Inf. Commun. Soc. 26, 37–53 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2014547

Brey, P.A.E.: Anticipatory ethics for emerging technologies. NanoEthics 6, 1–13 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-012-0141-7

Mikalef, P., Conboy, K., Lundström, J.E., Popovič, A.: Thinking responsibly about responsible AI and ‘the dark side’ of AI. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 31, 257–268 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2022.2026621

Dignum, V.: Responsibility and artificial intelligence. In: Dubber, M.D., Pasquale, F., Das, S. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Ethics of AI, pp. 213–231. Oxford University Press (2020)

Noorman, M.: Computing and moral responsibility. In: Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U. (eds.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University (2023)

Duff, R.A.: Who is responsible, for what, to whom. Ohio St J Crim L. 2, 441 (2004)

Sombetzki, J.: Verantwortung als Begriff, Fähigkeit, Aufgabe: Eine Drei-Ebenen-Analyse. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden (2014)

Coeckelbergh, M.: Artificial intelligence, responsibility attribution, and a relational justification of explainability. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26, 2051–2068 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00146-8

Frankfurt, H.: Alternate possibilities and moral responsibility. J. Philos. 66, 829–839 (1969)

Sher, G.: Who Knew? Responsibility Without Awareness. Oxford University Press, New York (2009)

Clarke, R.: Dispositions, abilities to act, and free will: the new dispositionalism. Mind 118, 323–351 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzp034

Nissenbaum, H.: Computing and accountability. Commun. ACM 37, 72–80 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1145/175222.175228

Floridi, L., Sanders, J.W.: On the morality of artificial agents. Minds Mach. 14, 349–379 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MIND.0000035461.63578.9d

Isaacs, T.: Moral Responsibility in Collective Contexts. Oxford University Press (2011)

Lewis, H.D.: Collective responsibility. Philosophy 23, 3–18 (1948). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031819100065943

Sverdlik, S.: Collective responsibility. Philos. Stud. 51, 61–76 (1987)

Borup, M., Brown, N., Konrad, K., Van Lente, H.: The sociology of expectations in science and technology. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 18, 285–298 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320600777002

Arnaldi, S., Bianchi, L.: Responsibility in Science and Technology: Elements of a Social Theory. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Imprint: Springer VS, Wiesbaden (2016)

Konrad, K., van Lente, H., Groves, C., Cynthia, S.: Performing an governing the future in science and technology. In: The Handbook of Science and Technology Studies. The MIT Press, Cambridge (2017)

te Kulve, H., Konrad, K., Alvial Palavicino, C., Walhout, B.: Context matters: promises and concerns regarding nanotechnologies for water and food applications. NanoEthics 7, 17–27 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-013-0168-4

van Lente, H.: Promising Technology: the Dynamics of Expectations in Technological Developments. Eburon Publ, Delft (1993)

Schulz-Schaeffer, I., Meister, M.: Laboratory settings as built anticipations—prototype scenarios as negotiation arenas between the present and imagined futures. J. Responsible Innov. 4, 197–216 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2017.1326260

Budde, B., Konrad, K.: Tentative governing of fuel cell innovation in a dynamic network of expectations. Res. Policy 48, 1098–1112 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.01.007

Grin, J.: Vision assessment to support shaping 21st century society? Technology assessment as a tool for political judgement. In: Grin, J., Grunwald, A. (eds.) Vision Assessment: Shaping Technology in 21st Century Society, pp. 9–30. Springer, Berlin (2000)

Frey, P., Dobroć, P., Hausstein, A., Heil, R., Lösch, A., Roßmann, M., Schneider, C.: Vision Assessment: Theoretische Reflexionen zur Erforschung soziotechnischer Zukünfte. KIT Scientific Publishing (2022)

Duff, R.A.: Responsibility. In: Craig, E. (ed.) Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge, London (1998)

European Commission: Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain union legislative acts. (2021)

Veale, M., Zuiderveen Borgesius, F.: Demystifying the Draft EU Artificial Intelligence Act—analysing the good, the bad, and the unclear elements of the proposed approach. Comput. Law Rev. Int. 22, 97–112 (2021). https://doi.org/10.9785/cri-2021-220402

Jacobs, M., Simon, J.: Assigning obligations in AI regulation. A discussion of two frameworks proposed by the European Commission. Digit. Soc. 1, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44206-022-00009-z

Collingridge, D.: The Social Control of Technology. St. Martin’s Press, New York (1980)

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

Strauss, A.L., Corbin, J.M.: Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (1998)

Williams, M., Moser, T.: The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. Int. Manag. Rev. 15, 45–55 (2019)

Gebru, T., Morgenstern, J., Vecchione, B., Vaughan, J.W., Wallach, H., Iii, H.D., Crawford, K.: Datasheets for datasets. Commun. ACM 64, 86–92 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3458723

Ozdemir, V., Faraj, S.A., Knoppers, B.M.: Steering vaccinomics innovations with anticipatory governance and participatory foresight. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 15, 637–646 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1089/omi.2011.0087

Te Kulve, H., Rip, A.: Constructing productive engagement: pre-engagement tools for emerging technologies. Sci. Eng. Ethics 17, 699–714 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-011-9304-0

Stilgoe, J., Owen, R., Macnaghten, P.: Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 42, 1568–1580 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

Fuerth, L.S.: Foresight and anticipatory governance. Foresight 11, 14–32 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1108/14636680910982412

Kolliarakis, G., Hermann, I.: Towards European Anticipatory Governance for Artificial Intelligence. Forschungsinstitut der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik e.V, Berlin (2020)

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy—EXC 2002/1 “Science of Intelligence”—project number 390523135.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors conducted field work at the research cluster they are affiliated with at the time of writing.

Ethical standards

Data are anonymized using pseudonyms and by removing identifiable information from the participants. This research complies with the code of conduct “Guidelines for safeguarding good research practices” as outlined by the German Research Foundation DFG (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burema, D., Jacobs, M. & Rozborski, F. Elusive technologies, elusive responsibilities: on the perceived responsibility of basic AI researchers. AI Ethics (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00358-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00358-6