Abstract

The high demand for the fashion industry currently results in the emergence of the fast fashion phenomenon, prompting consumers to spend more money on unnecessary clothing. This leads to excessive clothing production, which impacts pollution, waste, and emissions. The phenomenon of excessive fashion consumption and production can be mitigated by utilizing second-hand clothing products. Purchasing second-hand clothing products can be classified as part of mindful consumption behavior. The aim of this study is to examine the direct and indirect effects of Electronic Word of Mouth on mindful consumption behavior in the context of local second-hand clothing purchases. Additionally, this study also tests the mediating effects of consumer engagement and environmental attitudes. This research is quantitative in nature, employing data collection through questionnaires from local second-hand clothing consumers within the active workforce demographic (aged 18–59) in Indonesia, yielding 205 respondents. The data analysis technique used is structural equation modeling-partial least square (SEM-PLS). The research findings indicate a significant positive direct influence of Electronic Word of Mouth on environmental attitudes, consumer engagement, and mindful consumption behavior. Moreover, there is a notable positive direct influence between consumer engagement and mindful consumption behavior, while no significant influence is found in the relationship between environmental attitudes and mindful consumption behavior. Furthermore, the study confirms the mediating effect of consumer engagement between Electronic Word of Mouth and mindful consumption behavior but does not support a significant mediating effect of environmental attitudes on local second-hand clothing mindful consumption behavior.

Article Highlights

-

This study explores the effects of electronic word-of-mouth on mindful consumption behavior in the context of Indonesian local second-hand clothing purchases.

-

This research uses quantitative methodology through questionnaires filled by 205 local second-hand clothing consumers in Indonesia.

-

The result shows that consumer engagement has effect on electronic word-of-mouth and mindful consumption behavior but does not affect environmental attitudes of the Indonesian second-hand clothing consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The fashion industry is currently moving swiftly. The global clothing market shows growth from $610.12 billion in 2022 to $652.94 billion in 2023 with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.0% [1]. In Indonesia, a survey conducted by UMN Consulting on 1047 Generation Z respondents in Indonesia, showed that on average, the fashion consumption rate per year reached 62%, with respondents making purchases of 1 to 5 pieces of clothing per year. Even 11% of them make purchases of more than 10 pieces of clothing each year. This indicates a high demand for the fashion industry, which has led to the emergence of the fast fashion phenomenon, encouraging consumers to spend more money on purchasing unnecessary clothing [2].

Fast fashion, which focuses on the latest trends and low prices, leads to excessive clothing production, resulting in pollution, waste, and emissions [3]. For example, in 2017, H&M once burned 9 tons of unsold products. Additionally, data from Our Reworked World found that out of the total of 200 billion finished garments produced annually, 85% of them end up in landfills [4]. It is even recorded that 92 million tons of clothing end up in landfills every year. Additionally, the fashion industry is also considered the second-largest environmental polluter in the world after the oil industry, responsible for 2% to 8% of the global carbon emission volume [5]. The phenomenon leads to liquid waste, which causes excessive exploitation of natural resources and has a negative impact on the environment [6]. In Indonesia, textile waste contributes 3% (1 million tons) out of the total of 33 million tons of clothing produced annually [7]. The fast fashion trend is in direct conflict with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which consist of 17 goals focusing on global crisis issues [8]. The impact of fast fashion on achieving the SDGs, particularly SDG 6 concerning clean water and sanitation, and SDG 12 emphasizing the importance of responsible consumption and production, highlights the need for sustainable consumption and production patterns [9].

According to [10], although the fashion industry has long been a source of pollution and waste, there are signs that consumers are beginning to take action. Consumers are becoming more aware of the impacts of their consumption choices and decisions, and they are starting to seek more sustainable alternatives. Recycling is one solution to address the accumulation of waste in the world, including fashion industry waste. However, recycling alone is not sufficient to address this problem. Therefore, new efforts have emerged to reuse items, also known as “thrifting” [11]. The second-hand clothing market has experienced rapid growth over the past decade. According to ThredUp (2019), the second-hand clothing or thrifting industry is expected to become one of the most profitable sectors in the fashion industry over the next five years, with the market projected to reach $648 billion. ThredUp’s 2020 report reveals that an increasing number of consumers are shifting towards thrift shopping by using second-hand clothing [12]. The thrifting trend in Indonesia is becoming increasingly popular, especially among the younger generation [4]. Thrifting has now become the new fashion lifestyle among Indonesian youth. According to a survey by [13], as many as 49.9% of Indonesians admitted to buying second-hand fashion items from thrifting. In 2019, the second-hand clothing market, commonly known as thrifting, grew 21 times faster than the retail market over the past three years, and is estimated to double its global value to $51 billion by 2023 [14].

However, in Indonesia itself, there is a ban on the importation of second-hand clothing through thrifting activities, as it may disrupt the domestic textile industry [15]. What needs to be clarified here is the perception of this thrifting ban, as stated by the Minister of Cooperatives and SMEs (MenKopUKM) who declared that thrifting is legal, buying second-hand items is fine, selling second-hand items is allowed, but illegally importing second-hand items from abroad is prohibited [16]. In response to the ban on the importation of second-hand clothing business, the government and other stakeholders have suggested various solutions such as shifting to sell new local products, reselling local second-hand products, and selling personal pre-loved collections [17]. One solution that can be implemented is selling personal pre-loved collections, which is commonly known as pre-loved, and has been widely adopted by social media influencers. Platforms such as Carousell, Pasar Santa Jakarta, Second (event pre-loved), and coffee shops like Tradisi, Kisah Manis, and Kozi Malaka Bandung are examples of legal thrifting industries in Indonesia. In fact, some coffee shops in Bandung are currently popularizing pop-up stores selling local second-hand clothing to attract more consumers [4]. The growing trend of thrifting/pre-loved is seen as a positive activity as it offers various benefits, such as saving money, supporting sustainable fashion, and reducing clothing waste. The phenomenon of excessive fashion consumption and production can be mitigated by utilizing second-hand clothing products [18]. His has been validated by [19], which confirms that second-hand clothing effectively reduces the excess production of new clothing.

Given this phenomenon, eWOM (electronic word-of-mouth) can serve as a stimulus to influence consumer perception and attention towards local second-hand clothing. Through eWOM, consumers can obtain comprehensive data sources [20]. eWOM can now be conducted through various social media platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and even TikTok [21]. Unfortunately, in Indonesia, discussions and educational content on social media about the negative impacts of fast fashion are still limited. This is highlighted by a study from [22], which shows that fast fashion has a significant environmental impact, but awareness about this issue remains limited in many countries, including Indonesia. Additionally, research by [23] reveals that topics related to fast fashion contribute to less than 5% of the overall educational content on environmental issues on Indonesian social media, indicating a lack of attention to this issue.

With eWOM being accepted as a stimulus for second-hand clothing, individuals will internally process (organism) information into emotions, motivations, engagement, and attitudes. In Indonesia, a survey conducted by [24] with 2303 respondents (millennials and Gen Z) found that attitudes towards environmental conservation through recycling old clothes ranked last, with only 32.5% of respondents showing this attitude compared to other environmental concerns. This indicates a general lack of environmental awareness in Indonesia. With environmental concern and direct consumer engagement with local second-hand clothing, this results in an organismic response, referring to the condition when receiving a stimulus that then produces an output in the form of a response.

The response generated in this study is mindful consumption behavior by purchasing local second-hand clothing. Mindful consumption behavior is a function of mindfulness that cares about oneself, the environment, and society, originating from awareness in the mind that then becomes sustainable behavior. A brief interview with active consumers of local second-hand clothing conducted by the researcher revealed that "I prefer buying local second-hand clothes because they are cheaper and allow me to be more mindful in purchasing non-excessive clothing"—Steva (27 years old). Consistent with the research by [18], eWOM positively impacts mindful consumption behavior in second-hand clothing consumption with the stimulus-organism-response (S–O-R) theory. Consumers engaged in second-hand clothing consumption are more likely to exhibit sustainable consumption behavior [25]. This indicates that when consumers develop an emotional connection to second-hand clothing products, they are likely to be more cautious in their purchases with the principle of "simplicity" and pay more attention to environmental attitudes. Therefore, this study aims to extend previous research using the S–O-R theory, as it is seen as a significant solution for the fashion industry in Indonesia.

1.1 Literature review and hypotheses development

1.1.1 Conceptual fundation

S–O-R stands for Stimulus-Organism-Response, which is a theory to explain the relationship between external stimuli, behavioral responses, and internal processes that occur within individuals as organisms [28]. This theory assumes that stimuli (S) influence individual organisms (O), resulting in positive or negative responses (R) [29]. Stimulus is an external element or stimulus from the environment that affects the organism. In the context of marketing, stimuli can include advertisements, promotions, pricing, product packaging, and other elements that can influence consumer perception and attention. On the other hand, the organism refers to the individual or consumer who receives the stimulus. This part encompasses internal processes and psychological characteristics, such as emotions, motivations, and attitudes, which mediate between the stimulus and the response. The response then results in an action or behaviour produced by the organism as a reaction to the stimulus. In marketing, this response can take the form of a purchase decision, customer loyalty, or a change in attitude towards a product or brand [24]. The research conducted by [18] used eWOM as a stimulus variable, consumer engagement as the organism, and purchasing behavior as the response to second-hand clothing.

In the context of sustainable behavior, environmental factors and eco-friendliness can motivate customers to seek more information about products on the internet or other reliable sources, significantly influencing subsequent behavior [30]. Therefore, in this study, the researcher considers eWOM to be an important stimulus that can influence consumer attitudes and engagement towards second-hand clothing, ultimately resulting in mindful consumption behavior.

1.1.2 Electronic word of mouth (eWOM)

With the advancement of technology in today’s era, the internet has changed the way consumers communicate and share opinions and reviews. Consumer opinions can be quickly read by other consumers with the potential for a large reach worldwide [31]. This communication process is commonly referred to as Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM). eWOM refers to positive or negative statements about a product or company made by potential, actual, or former customers through the internet [18]. Based on research of [31], 90% of online buyers consult consumer opinions online before making a purchase, and another 70% trust eWOM in their purchasing decisions. This can be interpreted as this type of communication having significant persuasive power through higher credibility and trust.

In the fashion sector itself, marketing users make many efforts to enhance eWOM in order to boost their sales [32]. Based on research of [18], this study argues that the use of eWOM in purchasing second-hand clothing is a new strategy that can be employed to preserve and protect the environment and its natural resources, increase individuals' interest in obtaining fashionable items at affordable prices, and promote social well-being by reducing excessive production of new clothing that could potentially harm the environment, thus making consumers more inclined to buy second-hand clothing, and finally, to enhance satisfaction and motivate consumers to exhibit wise behavior by purchasing second-hand clothing.

1.1.3 Environmental attitudes

In an environmental context, environmental attitudes are psychological tendencies expressed in the evaluation of perceptions about the natural environment, including factors affecting its quality, with certain levels of preference or dislike [33]. According to Gifford (2016), environmental attitudes are described as a collection of beliefs, influences, and behavioural intentions held by an individual concerning environmental activities or issues. According to Amyx et al. (as cited in [34]), the goal of individuals with environmental attitudes is to express respect for the environment as a way to demonstrate concern for environmental issues. In the context of the fashion industry, Butler and Francis in [35] state that an individual's environmental attitudes positively influence purchasing behaviour and several environmentally oriented clothing disposal methods, such as donations to charity and reuse. In the context of second-hand clothing, attitudes are defined as psychological aspects that affect an individual’s selection, use, and disposal of clothing. This includes behaviours towards second-hand clothing that can influence consumer preferences and decisions regarding the purchase and use of second-hand items. The higher an individual’s environmental attitudes, the more reluctant they are to purchase fast fashion products [36]. Additionally, research by [37] shows that as consumer attitudes towards second-hand clothing improve, their intention to consume such products also increases. Another study by [38] on second-hand clothing also reveals that a positive attitude towards second-hand clothing strongly predicts consumers' intention to buy it, while consumers with a negative attitude are more likely to reject consuming second-hand items.

Based on the findings discussed above, it can be interpreted that when consumers decide to engage in a particular behavior, they tend to evaluate the benefits and costs associated with that behavior [39]. In line with the discussion on eWOM and attitudes, it is clear that eWOM influences consumer attitudes towards products [40]. Referring to the research by [18], this study assumes that the information available online about second-hand clothing (thrifting) can positively influence consumers' perceptions of second-hand clothing, leading to more mindful purchasing behavior towards such items.

1.1.4 Consumer engagement

In the context of marketing, consumer engagement is an innovative concept originating from the social sciences, particularly organizational behavior, psychology, sociology, and political science [50]. According to [51], consumer engagement is defined as the emotional bond between consumers and brands, resulting from the accumulation of consumer experiences that assume favorable and proactive psychological conditions. More specifically, consumer engagement refers to the psychological state or attitude that drives behavior toward a particular product recommendation, service, or brand [52]. In this study, consumer engagement refers to the effective communication between the brand and consumers in the second-hand clothing product on social media. With consumer engagement in responding to promotions and providing feedback, this can help companies achieve better performance [32]. Furthermore, in the research by consumer engagement is a multidimensional construct reflected in three dimensions: conscious attention, enthused participation, and social connection.

1.1.5 Mindful consumption behavior

The high level of excessive consumption also has an impact on environmental and human damage. Currently, consumers are more inclined to consume based on desires rather than needs, for example, purchasing new necessities even when previously bought clothes have not been worn [41]. According to [42], mindful consumption is defined as the application of awareness to inform choices made by consumers. The implementation of mindful consumption is an approach advocated to change society, markets, and individual well-being [43]. This consumption attitude also involves behaviors, mindsets, and decision-making related to concerns about the future and consequences on oneself, communities, or the environment [44]. Overall, mindful consumption is based on the idea of ‘‘simplicity’’ aimed at optimizing consumption according to the needs and values of everyone [18].

1.1.6 Electronic word of mouth (eWOM) and environmental attitude

Environmental attitudes are defined as attitudes that show a positive influence on purchasing behavior and various environmentally-oriented clothing disposal methods, such as donations to charity and reuse [35]. When deciding to engage in certain behaviors, individuals tend to evaluate the benefits and costs that may arise from those behaviors [39].

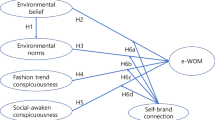

Based on several previous studies, variables that have been shown to have a positive impact on consumer attitudes and behavior are eWOM [18]. eWOM influences consumer attitudes toward products, both online and offline purchases in the fashion industry [40]. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 1, this study assumes that online information about second-hand clothing can positively influence consumers’ perceptions of second-hand clothing, resulting in mindful purchasing behavior, assuming it is based on the S-O-R theory.

1.2 H1: eWOM has a positive and significant influence on environmental attitudes

1.2.1 Electronic word of mouth (eWOM) and consumer engagement

Consumer engagement is defined as the attachment and emotional bond of consumers to a particular context [53]. In this study, consumer engagement refers to the intensity of interaction, participation, and connection of consumers with second-hand clothing [54]. Digital platforms that shape eWOM such as social media, seller pages, and online review sites are crucial for the clothing industry, as they serve as new ways to facilitate consumer engagement and build brand loyalty [55]. Therefore, this study assumes that eWOM can have a positive effect on consumer engagement in purchasing second-hand clothing, an assumption based on the S-O-R theory.

1.3 H2: eWOM has a positive and significant influence on consumer engagement

1.3.1 Electronic word of mouth (eWOM) and mindful consumption behavior

Mindful consumption behavior is considered significant as it can make consumers more aware of their consumption patterns and their impact on society and the environment [56]. Although various studies have investigated the role of mindful consumption behavior and mindfulness in promoting sustainable behavior [57], little is known about marketing strategies that lead to mindful consumption behavior. Previous research has shown that eWOM communication influences consumer attitudes and ultimately leads to their purchasing behavior [58].

Theoretically, the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior is explained as follows: the greater the relevance of the message and the greater attention paid by individuals to the received message, the greater the likelihood that they will react positively to the message [18]. This model has been widely adopted in previous research to explain consumer purchasing behavior on social networking sites through the influence of eWOM [59]. Based on the previous discussion, this study assumes that eWOM can positively influence consumers' mindful consumption behavior.

1.4 H3: eWOM has a positive and significant influence on mindful consumption behavior

1.4.1 Environmental attitudes and mindful consumption behavior

The relationship between attitude and behavior explains that if consumers have positive or negative feelings towards a particular object, there is a tendency to behave in two ways: avoidance or approach [18]. According to the research by [60] and [61], they confirm a positive relationship between attitude and behavior, acknowledging that environmental attitudes positively influence consumer fashion purchasing behavior. Similarly, according to [18], attitudes have a positive impact on consumers' intention to purchase environmentally friendly products. This study also assumes a positive relationship between environmental attitudes and mindful consumption behavior.

1.5 H4: Environmental attitudes have a positive and significant influence on mindful consumption behavior

1.5.1 Consumer engagement and mindful consumption behavior

The importance of consumer engagement has been recognized as a influential factor in driving behavioral change in environmental contexts [62]. Consumer engagement has also been acknowledged as a driver of behavior in various fields such as psychology, sociology, marketing, and organizational behavior [18]. Although previous research has confirmed the positive relationship between engagement and various types of behavior, the relationship between consumer engagement and mindful consumption behavior has been less explored. To address this gap, this study considers the positive relationship between consumer engagement and mindful consumption behavior.

1.6 H5: Consumer engagement has a positive and significant influence on mindful consumption behavior

1.6.1 Environmental attitudes as a mediator between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior

According to [63], environmental attitudes play a crucial role as a mediator in the relationship between physiological factors and purchasing behavior in the context of virtual stores and wireless finance. Marketing strategies such as eWOM can influence their positive attitudes towards second-hand clothing, which in turn leads to mindful consumption behavior, as the purchase of second-hand clothing is driven by consumers' environmental awareness [64].

The mediating role of environmental attitudes between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior can be supported by the S-O-R theory. Specifically, eWOM serves as an external factor (stimulus) that influences consumers' internal beliefs about second-hand clothing positively or negatively (organism), which is expected to subsequently influence consumers' mindful consumption behavior.

1.7 H6: Environmental attitudes have a positive and significant influence in mediating the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior

1.7.1 Consumer engagement as a mediator between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior

Based on previous research by [65], it is shown that consumer engagement mediates the relationship between social network marketing and consumers' purchase intentions and/or behaviors. This study considers the S-O-R as the theoretical foundation supporting the idea of considering consumer engagement as a mediator in the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior. More specifically, eWOM is depicted as a stimulus that can motivate consumers to engage in second-hand clothing (organism), which ultimately drives mindful consumption behavior (response) [18]. However, due to the lack of understanding regarding the mediating role of consumer engagement in second-hand clothing between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior, it can be assumed that consumer engagement may serve as a mediator between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior in the second-hand clothing industry.

1.8 H7: Consumer engagement has a positive and significant influence in mediating the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior

2 The research methodology

This research employed a quantitative method using questionnaire distribution for data collection, utilizing a Likert scale with five possible responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). All scales for measuring the study’s variables were adapted from previous studies by Mohammad et al. (2020) and Mason et al. (2022). eWOM was measured as a multidimensional construct with three dimensions according to [18]: general persuasiveness (two items), general credibility (two items), and susceptibility to online reviews (four items). Environmental attitudes were assessed using two items adapted from [35]. The consumer engagement variable, adapted from [18], was measured as a multidimensional construct with three dimensions: conscious attention (six items), enthused participation (six items), and social connection (three items). Mindful consumption behavior, as a multidimensional construct, included three dimensions: acquisitive consumption (one item), repetitive consumption (one item), and aspirational consumption (one item), adapted from [18].

2.1 Non-response bias

The questionnaire was distributed to local second-hand clothing consumers who are active members of the workforce (aged 18–59) in Indonesia, assuming that this age group possesses sufficient knowledge about financial decision-making and can provide a clear picture of mindful consumption behavior regarding local second-hand clothing products. The questionnaire was distributed to 18,255 local second-hand clothing consumers via social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram, resulting in a response rate of 1.1%, equivalent to 209 respondents. About 4 respondents were excluded for not meeting the research criteria, resulting in 205 respondents for this study. In this research, the data collection technique used was non-probability sampling method. The selection of the non-probability sampling method employed purposive sampling with the aim of obtaining a representative sample according to the specified criteria. The determination of the sample size in this study was calculated using G-Power, with a minimum sample size of 119 respondents. Therefore, the sample of 205 respondents obtained was considered appropriate for conducting the analysis. These numbers were represented by 150 respondents residing in Java, the biggest and most populated island of Indonesia, and the rest come from the other Indonesian big islands (Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi).

This research was conducted based on the S-O-R model by [18] and [35], which is considered suitable for interpreting customer responses or behaviors influenced by environmental stimuli. The researchers utilized the S-O-R model to analyze the influence of eWOM on customer consumption behavior towards local second-hand clothing products.

3 The analysis and findings

The characteristics of respondents in this study can be classified based on age group, gender, level of education, occupational group, and income or pocket money, as shown in Table 1. The majority of respondents are aged 18–26 years (86.8%) with the highest percentage of female respondents (54%). About 59% of respondents have a bachelor’s degree as their highest level of education. Some respondents are already employed (73.2%) with an income or pocket money ranging from Rp1,000,001 to Rp3,000,000, accounting for 28.8%.

This study employs the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) method with Partial Least Square (PLS) analysis processed using SmartPLS v.3.2.9 software. According to [66], SEM combines regression models, factor analysis, and path analysis. This research utilizes PLS with the aim of predicting the relationships among constructs and assisting researchers in obtaining latent variable values for prediction purposes [67].

As [18] suggest, due to the multidimensionality of the eWOM and consumer engagement variables in this study, the outer model measurement test is conducted in two stages (embedded two stage). In the embedded two-stage method, validity and reliability values need to be measured for lower-order components first and then for higher-order components [68].

3.1 The result of the measurement model (first order)

The evaluation of the measurement model in the outer model stage (first order) is conducted to test the validity and reliability representing each construct with the aim of determining the validity and reliability of each item in the eWOM and consumer engagement dimensions in this study [68]. This test is based on three types of measurements: convergent validity (comprising factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE), discriminant validity (comprising cross-loading, Fornell-Larcker, heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT), and reliability test (comprising composite reliability) [69]. The research model to be tested is presented as shown in Fig. 2:

In this stage, indicator testing is conducted by examining the values of factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). According to [69], an item can be considered acceptable if the factor loading value is between 0.5 to 0.6, which is generally considered sufficient, and if > 0.7, it is considered high. Average variance extracted (AVE) can be said to have sufficient convergent validity if it has an AVE > 0.5 [70].

From Table 2, the factor loading values are greater than 0.5, so all items can be accepted. Similarly, the AVE values for each dimension in the eWOM and consumer engagement variables are > 0.5, which means they meet the criteria for convergent validity, indicating that the variance of each indicator in these dimensions can be explained by each construct. Additionally, the composite reliability values for all dimensions in the eWOM and consumer engagement variables have scores > 0.7, meaning the data is reliable.

The next stage is the calculation of discriminant validity, which is used to measure the measurement results indicating that the variables are not highly correlated [71]. From the calculation results of the square root of AVE as shown in Table 3, it can be determined that all variables in this study have met discriminant validity because the Fornell-Larcker values or the square root of AVE (bold numbers) have high values compared to the AVE of other constructs. The HTMT values should be < 0.9 to detect differences between two factors [72]. All related factors produce HTMT values < 0.9. This can be interpreted as meeting discriminant validity.

3.2 The result of the measurement model (second order)

At this stage, the outer model test is still conducted for the second-order stage. The research model to be tested will be presented as shown in Fig. 3. The validity and reliability tests aim to determine the level of validity and reliability of each item in each variable in this study.

From Table 4, the calculation results of the square root of AVE, it can be determined that all variables in this study have met discriminant validity because the Fornell-Larcker values or the square root of AVE (bold numbers) have high values compared to the AVE of other constructs. As shown in Table 5, The HTMT values should be < 0.9 to detect differences between two factors [72]. All related factors produce HTMT values < 0.9. This can be interpreted as meeting discriminant validity.

3.3 The result of the inner model

Assumptions or conditions in the analysis of the inner model using Partial Least Squares show no multicollinearity issues [70]. The inner VIF values can be considered to have no multicollinearity between variables if they are < 5. Based on the table above, it shows that the estimated inner VIF is < 5, indicating a low level of multicollinearity between variables. These results indicate that the parameter estimation is robust (unbiased). The results of the structural inner model testing are as shown in Fig. 4:

The larger the value of R Square, the stronger the endogenous variables are explained by the exogenous variables. According to [73] the criteria for the limitation of the R square value are divided into three classifications: 0.67 (high), 0.33 (moderate), and 0.19 (weak). If the value of Q square > 0, then the model can be said to have predictive relevance. Based on Table 6, this means that the model can be used to measure the suitability of the model's predictions in predicting the original data values.

3.4 Results of the structural model

To measure the significance of the model's influence of each variable, it is necessary to look at the values of path coefficient, t-value, and p-value [71]. This study uses a significance level of 5% with one-tailed testing, where the t-value must be greater than 1.64 and the p-value must be less than 0.05. If both values are met, then it can be said that there is a significant relationship between independent and dependent variables, or in other words, the hypothesis can be accepted. For the interpretation of values in direct effect, they are 0.02 (low), 0.15 (moderate), and 0.35 (high) [70]. Table 7 summarizes the results of the structural model for direct and indirect relationships.

The results from Table 7 indicate that eWOM significantly and positively influences environmental attitudes (path coefficient = 0.469, t-value = 5.475, p-value = 0.000), consumer engagement (path coefficient = 0.377, t-value = 6.798, p-value = 0.000), and mindful consumption behavior (path coefficient = 0.157, t-value = 1.757, p-value = 0.037), providing support for H1, H2, and H3. Contrary to expectations, environmental attitudes are not associated with mindful consumption behavior (path coefficient = 0.050, t-value = 0.577, p-value = 0.286). Thus, H4 is not supported. Additionally, consumer engagement significantly and positively influences mindful consumption behavior (path coefficient = 0.255, t-value = 3.989, p-value = 0.000), meaning H5 is accepted.

Mediation testing was conducted using the bootstrapping method by considering the values of path coefficient, t statistic, and p-value [71]. Contrary to expectations, the mediating effect of environmental attitude between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior is not supported (path coefficient = 0.096, t-value = 0.538, p-value = 0.295). Bootstrapping results show that H7 is accepted with a value of (path coefficient = 0.024, t-value = 3.688, p-value = 0.000), indicating consumer engagement have a positive and significant influence in mediating the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior. In this study, the consumer engagement variable is able to have a direct impact with a larger direct effect value compared to its indirect effect on mindful consumption behavior, and the consumer engagement variable also significantly mediates. Therefore, the role of consumer engagement is partial mediation, meaning eWOM can increase mindful consumption behavior with or without consumer engagement.

4 Discussion

This study aims to analyse the direct and indirect effects of eWOM on consumer engagement, environmental attitudes, and mindful consumption in the context of local second-hand clothing in Indonesia. Additionally, this research also examines the importance of environmental attitudes and consumer engagement in mediating the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior. To achieve this goal, a theoretical model based on the S–O-R theory was constructed and and was tested using the PLS technique. The results of this study confirm the significant positive direct effects of eWOM on environmental attitudes, consumer engagement, and mindful consumption behavior. The exchange of information through eWOM has been shown to help alter or reshape attitudes toward specific objects [74]. More specifically, the dissemination of eWOM in the environmental context has been examined by Filieri et al. (2021), whose findings indicate that consumers are increasingly interested in understanding the environmental impact of products, accompanied by attitude formation after reading online consumer reviews. This result suggests that eWOM can enhance positive evaluations of consumer attitudes toward the environment, leading them to make more considered purchases to avoid excessive consumption and environmental pollution. In the context of consumer engagement, this is relevant to the research by [75], which found that eWOM enhances consumer engagement by encouraging social contact, message dissemination, and expressions and opinions related to a brand or product. eWOM is considered to have a significant influence on consumers because they tend to trust eWOM before purchasing a product [18]. Consequently, eWOM increases consumers' positive perceptions of local second-hand clothing, leading to higher consumer involvement in this sector [76]. Additionally, reliable consumer reviews can enhance awareness of mindful behavior. Thus, reviews can lead to deep interpersonal considerations and influence customers' decision-making processes regarding product reviews, product selection, and wise purchasing decisions [77].

The study found no significant direct effect of environmental attitudes on mindful consumption behavior. Contrary to expectations explained in the research [29], sustainable consumption behavior (green consumption and pro-environmental behavior) was anticipated to have a positive effect on mindful consumption behavior due to the need for sacrifice and/or self-restraint, but this was not supported. This also contrasts with the study by [25], which found that consumers who care about sustainability issues, understand their own responsibilities, and believe that individual actions can make a difference are more willing to engage in sustainable consumption. The discrepancy may occur when individual attitudes do not correlate with their actions. Generally, many consumers show environmental concern, yet their purchasing decisions do not reflect mindful consumption that leads to environmental care [18]. For the relationship between consumer engagement and mindful consumption behavior, this study found a significant positive relationship. Consumers who develop an emotional connection to local second-hand clothing tend to be more cautious in their purchases, driven by the principle of "simplicity." Engagement in all types of sustainable behavior leads to a sense of responsibility and reinforces actual sustainable behavior practices [78].

In the mediating relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior, there was a significant positive influence through consumer engagement, but no significant effect was found through environmental attitudes.. These results align with the S-O-R theory, indicating that environmental stimuli (eWOM) positively or negatively affect internal mental states (consumer engagement), resulting in consumer responses (mindful consumption behavior). Meanwhile, the role of consumer engagement in this relationship is considered a partial mediation effect. Thus, each purchase of local second-hand clothing may result from eWOM experiences, contributing to environmental conservation efforts for those products [32]. In this regard, [78] suggest that when individuals engage with a brand and have environmental concerns, they are more likely to be motivated to address environmental issues unless there is cognitive dissonance. Therefore, the findings of this study indicate that marketers need to enhance interactions with customers, such as through promotions that evoke positive feelings and emotional attachment to local second-hand clothing. Regarding environmental attitudes, the small mediating effect of environmental attitudes on the relationship between eWOM and mindful consumption behavior indicates that the direct effect of eWOM on mindful consumption behavior is greater than the indirect effect through environmental attitudes. This implies that changes in consumers' environmental attitudes due to eWOM do not necessarily influence mindful behavior in frugal consumers. This contradictory finding may be due to a gap between attitudes and behaviors, related to personal and psychological factors. Such a gap occurs when there is a discrepancy between what customers say and what they actually do [64]. For example, a survey conducted by the United Nations Environmental Programme found that 40% of respondents claimed they were willing to purchase environmentally friendly products and services, but only 4% actually did so [81]. To understand the factors contributing to this issue, several possible reasons include: (1) Indonesian consumers still tend to prefer buying new clothes due to considerations of cleanliness and affordability; (2) Social expectations about luxury items such as fashionable clothes, big houses, and expensive cars often make people hesitant to accept second-hand clothing due to negative perceptions associated with it; (3) A lack of awareness among Indonesian consumers about sustainable consumption [18].

5 Theoretical contribution and managerial implications

5.1 Theoretical contribution

This study illustrates how responses from consumers of local second-hand clothing provide deep insights into mindful consumption behavior. Positive electronic word of mouth (eWOM) about local second-hand clothing on social media has been shown to influence engagement with fast fashion issues and increase awareness. This indicates that consumer engagement has a positive and significant mediating effect. Although environmental attitudes did not show a significant mediating effect, future research could explore how to effectively enhance engagement to mediate the impact of eWOM on consumption behavior, such as perceived value, brand trust, or other variables. The relatively low R-Square values for consumer engagement, environmental attitudes, and mindful consumption behavior suggest that there is room for improvement in the research model. Future research is recommended to include additional variables that might affect these endogenous variables, such as personal motivation, social awareness, or subjective norms. These variables have the potential to provide new and relevant insights into the factors influencing mindful consumption behavior. Additionally, considering the impact of demographic variables, such as age, gender, income, and education, on mindful consumption behavior could be an interesting area of research. Further studies in this area could help identify different market segments and develop more focused and effective marketing strategies.

5.2 Practical and social implications

This study offers several implications for marketers and practitioners related to local second-hand clothing in Indonesia. Positive word of mouth about local second-hand clothing on social media influences engagement with fast fashion issues and raises awareness. Sellers and marketers of local second-hand clothing can encourage consumers to adopt this new consumption model (mindful consumption behavior) by promoting reuse and recycling based on environmental benefits to society. A message of responsibility and commitment to purchasing local second-hand clothing can serve as a key focus for marketing communications. Creative promotional strategies, such as offering discounts, can spark interest and emotional attachment to local second-hand clothing, enhancing consumer engagement. Local second-hand clothing businesses can also boost eWOM by encouraging customers to leave reviews and testimonials online through a "Referral Program" that highlights the benefits of purchasing local second-hand clothing. Campaigns promoting these reviews can strengthen positive perceptions and build consumer trust in the products. Despite the already high environmental attitudes observed in this study, deeper education on the importance of environmental issues is needed to translate attitudes into concrete actions.

To enhance consumer engagement, companies can use interactive content such as quizzes, webinars, or online discussions that involve customers in environmental issues and sustainable consumption. Campaigns emphasizing the benefits of buying local second-hand clothing and its impact on the environment can also promote mindful consumption behavior. Additionally, loyalty programs offering points or discounts for purchasing local second-hand clothing and participating in recycling programs can be implemented as additional strategies. These steps can not only increase consumer engagement and awareness but also support more sustainable and environmentally friendly consumption practices.

6 Limitations and future research directions

This study has several limitations that could provide opportunities for future research. The findings are primarily based on the responses of active working consumers aged 18–59 years regarding local second-hand clothing products in Indonesia. Future researchers might explore other fashion categories, such as organic clothing, or examine other industries like cosmetics and fast-moving fashion lines in various countries and regions to gain broader insights from different cultural perspectives. This study concludes that environmental attitudes do not significantly influence an individual’s purchase of local second-hand clothing products in the context of mindful consumption behavior.

Overall, a critical debate should take into account the breadth and depth of research, even if the study probably offers insightful information on the connection between mindful consumption and used clothes in Indonesia. Future research ought to challenge these claims: Can the results be applied to other customer segments? Does the research sufficiently tackle the intricacies of cultural and economic elements in molding conscientious consumption? By providing answers to these queries, we may develop a more sophisticated comprehension of the advantages and disadvantages of the research. Future research could incorporate additional variables that might encourage mindful consumption behavior, such as brand, price, or other factors. Additionally, future studies might consider the impact of demographic variables (such as age, gender, income, and education) on mindful consumption behavior.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Apparel Global Market. Apparel global market report 2023. 25 April 2023. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/clothing.

Kompas.com. Mengenal Fenomena Fast Fashion, Ciri-ciri, dan Dampaknya, 15 Sept 2022. https://www.kompas.com/tren/read/2022/09/15/113000165/mengenal-fenomena-fast-fashion-ciri-ciri-dan-dampaknya?page=all.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The united nations environment programme, 24 Nov 2022. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/environmental-costs-fast-fashion.

Hur E. Rebirth fashion: secondhand clothing consumption values and perceived risks. J Clean Product. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122951.

Zahid NM, Khan J, Tao M. Exploring mindful consumption, ego involvement, and social norms influencing second-hand clothing purchase. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(16):13960–74.

Rahman O, Koszewska M. A study of consumer choice between sustainable and non- sustainable apparel cues in Poland. J Fash Mark Manag. 2020;24(2):213–34.

CnbcIndonesia.com. Tak Terduga! Jutaan Limbah Tekstil Ternyata Berasal Dari Sini 19 Oct 2022. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20221019164842-4-381003/tak-terduga-jutaan-limbah-tekstil-ternyata-berasal-dari-sini.

United Nations. Sustainable development goals. 25 Sept. 2015. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

Kompasiana.com. Fast fashion dan sustainable development goals: Bagaimana Kaitan antara Keduanya?," 10 Jun 2022. https://www.kompasiana.com/reginaene7543/62a36992bb448677d74bbe32/fast-fashion-dan-sustainable-development-goals-bagaimana-kaitan-antara-keduanya?page=all#section1.

Martenson R. When is green a purchase motive? Different answers from different selves. Int J Retail Distribution Manag. 2018;46(1):21–33.

Kumparan.com. Fenomena Thrifting, Kok Bisa Trending? 30 Oct 2022. https://kumparan.com/patricia-lorena/fenomena-thrifting-kok-bisa-trending-1z99ZjXiGh3/full.

Kompas.com. Citayam Fashion Week, Generasi Z, dan Limbah Fashion yang Tak Disadari. 19 July 2022. https://jeo.kompas.com/citayam-fashion-week-generasi-z-dan-limbah-fashion-yang-tak-disadari.

GoodStats. Menilik Preferensi Fesyen Anak Muda Indonesia. 2 Aug 2022. https://goodstats.id/article/menilik-preferensi-fesyen-anak-muda-2022-sqOFi.

ThredUp, thredUP Releases 7th Annual Resale Report 19 Mar 2019. https://newsroom.thredup.com/news/2019/03/19/thredup-releases-7th-annual-resale-report.

Detik.com. Pro Kontra Larangan Impor Baju Bekas di Tengah Tren Thrifting Baca artikel detiknews. Pro Kontra Larangan Impor Baju Bekas di Tengah Tren Thrifting" selengkapnya https://news.detik.com/berita/d-6625190/pro-kontra-larangan-impor-baju-bekas-di-tengah-tren. 17 Maret 2023. https://news.detik.com/berita/d-6625190/pro-kontra-larangan-impor-baju-bekas-di-tengah-tren-thrifting.

Antaranews.com, "MenKopUKM cari solusi terbaik terkait impor barang bekas illegal. 30 Maret 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.antaranews.com/berita/3464316/menkopukm-cari-solusi-terbaik-terkait-impor-barang-bekas-ilegal.

Ukmindonesia.id. Impor Pakaian Bekas Dilarang, Berikut Solusi Kreatif untuk Bisnis Thrifting Agar Bisa Bertahan 30 Maret 2023. https://ukmindonesia.id/baca-deskripsi-posts/impor-pakaian-bekas-dilarang-berikut-solusi-kreatif-untuk-bisnis-thrifting-agar-bisa-bertahan.

Mohammad J, Quoquab F, Sadom NZM. Mindful consumption of second- hand clothing: the role of eWOM, attitude and consumer engagement. J Fashion Market Manage. 2020;1:1–29.

Rausch TM, Kopplin CS. Bridge the gap: consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. J Clean Product. 2021;278:1–16.

Fang J, Zhao Z, Wen C, Wang R. Design and performance attributes driving mobile travel application engagement. Int J Inf Manage. 2017;37(4):269–83.

Lestari ED, Gunawan C. Pengaruh E-Wom Pada Media Sosial Tiktok Terhadap Brand Image Serta Dampaknya Pada Minat Beli. EMBISS Jurnal Ekonomi, Manajemen, Bisnis Dan Sosial. 2021;1(2):1–16.

Earth.org. Fast fashion and its environmental impact. Earth.org, 5 Jan 2024. earth.org: https://earth.org/fast-fashions-detrimental-effect-on-the-environment/. [Accessed 3 May 2024].

Cayaban C, Prasetyo YT, Persada S, Borres RD. The influence of social media and sustainability advocacy on the purchase intention of Filipino consumers in fast fashion. MDPI Sustain. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15118502.

Databoks, Survei: Banyak Anak Muda Semakin Peduli Terhadap Lingkungan. 16 Aug 2022. https://databoks.katadata.co.id/datapublish/2022/09/16/survei-banyak-anak-muda-semakin-peduli-terhadap-lingkungan.

Piligrimiene Z, Zukauskaite A, Korzilius H, Banyte J, Dovaliene A. Internal and external determinants of consumer engagement in sustainable consumption. Sustainability. 2020;12(4):1349.

TribunJabar, Minat Pembeli Tinggi, Tren Belanja Preloved Milik Publik Figur & Influencer Kembali Hadir di Bandung. 2 Sep 2023. https://jabar.tribunnews.com/2023/09/02/minat-pembeli-tinggi-tren-belanja-preloved-milik-publik-figur-influencer-kembali-hadir-di-bandung.

P. N. R. Ramadani. Fast Fashion Waste, Limbah yang Terlupakan. 2 Nov 2022. https://www.its.ac.id/news/2022/11/02/fast-fashion-waste-limbah-yang-terlupakan/.

R DiClemente RA Crosby S-O-R Theory 2019. Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine 12 1 3

Quoquab F, Sadom NM, Mohammad J. Driving customer loyalty in the Malaysian fast food industry: the role of halal logo, trust and perceived reputation. J Islamic Market. 2019;11(6):1367–87.

Luzio J, Lemke F. Exploring green consumers’ product demands and consumption processes. Eur Bus Rev. 2013;25(3):281–300.

López M, Sicilia M. Determinants of E-WOM influence: the role of consumers’ internet experience. J Theor Appl Electron Commerce Res. 2014;9:28–43.

Kristia K. Mediating effect of customer engagement on the relations between eWOM environmental concern and intention to purchase second-hand clothing among college students in Yogyakarta. J Manajemen Bisnis. 2021;12(2):162–75.

Duarte R. The influence of the family, the school, and the group on the environmental attitudes of European students. Environ Educ Res. 2015;23:1469–5871.

Junaedi M. Pengaruh Kesadaran Lingkungan Pada Niat Beli Produk Hijau: Studi Perilaku Konsumen Berwawasan Lingkungan. Benefit. 2015;9(2):1–13.

Mason M, Pauluzzo R, Umar R. Recycling habits and environmental responses to fast-fashion consumption: enhancing the theory of planned behavior to predict Generation Y consumers’ purchase decisions. Waste Manage. 2022;2(16):146–57.

Joung H-M. Ast-fashion consumers’ post-purchase behaviors. Int J Retail Distrib Manag. 2014;42(8):688–97.

Acquaye R, Seidu R, Eghan B, Fobiri GK. Consumer attitude and disposal behaviour to second-hand clothing in Ghana. Scientific African. 2023;21(1):1–12.

Seo M, Kim M. Understanding the purchasing behaviour of second-hand fashion shoppers in a non-profit thrift store context. Int J Fashion Design. 2019;12(3):301–12.

Quoquab F, Pahlevan S, Mohammad J, Thurasamy R. Factors affecting consumers’ intention to purchase prodfeit product: empirical study in the Malaysian market. Asia Pac J Mark Logist. 2017;29(4):837–53.

Reichelt J, Sievert J, Jacob F. How credibility affects eWOM reading: the influences of expertise, trustworthiness, and similarity on utilitarian and social functions. J Mark Commun. 2014;20(1–2):65–81.

Gupta S, Lim W, Verma HV, Polonsky M. How can we encourage mindful consumption? Insights from mindfulness and religious faith. J Consum Mark. 2023;40:344–58.

Milne G, Ordenes F, Kaplan B. Mindful consumption: three consumer segment views. Australas Mark J. 2020;28(1):2–10.

Bahl S, Milne G, Ross S, Mick D, Grier S, Chugani S, Chan S. Mindfulness: its transformative potential for consumer, societal, and environmental well-being. J Public Policy Mark. 2016;35(2):198–210.

-T. Pusaksrikit, S.Pongsakornrungsilp and P.Pongsakornrungsilp. The development of the mindful consumption process through the sufficiency economy. 13 Oct 2023. http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/v41/acr_v41_14843.pdf.

Hogg MA. Vaughan social psychology. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited; 2020.

Koay KY, Cheah CW, Lom HS. An integrated model of consumers’ intention to buy second-hand clothing. Int J Retail Distr Manage. 2022;50:1–20.

Yadav R, Pathak G. Determinants of consumers’ green purchase behavior in a developing nation: applying and extending the theory of planned behavior. Ecol Econ. 2017;134:114–22.

Razzaq A, Ansari N, Razzaq Z, Awan H. The impact of fashion involvement and pro-environmental attitude on sustainable clothing consumption: the moderating role of Islamic religiosity. SAGE Open. 2018;8(2):1–13.

Mason MC, Pauluzzo R, Umar RM. Recycling habits and environmental responses to fast-fashion consumption: enhancing the theory of planned behavior to predict generation Y consumers’ purchase decisions. Waste Manage. 2022;139:146–57.

Kuvykaite R, Tarute A. A critical analysis of consumer engagement dimensionality 20th international scientific conference economics and management. Proc Soc Behav Sci. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.468.

Rather RA. Consequences of consumer engagement in service marketing: an empirical exploration. J Global Market. 2018;32:1–20.

Brodie RJ, Ilic A, Juric B, Hollebeek L. Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: an exploratory analysis. J Business Res. 2013;32:105–14.

Taheri B, Jafari A, O’Gorman K. Keeping your audience: presenting a visitor engagement scale. Tour Manage. 2014;42:321–9.

Vivek S, Beatty SE, Dalela V, Morgan R. A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. J Market Theor Pract. 2014;22(4):401–20.

Kozlowski A, Searcy C, Bardecki M. Innovation for a sustainable fashion industry: a design focused approach toward the development of new business models. In: Gardetti M, editor. Green Fashion Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes. Singapore: Springer; 2016.

Lim W. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. J Bus Res. 2017;78:69–80.

Helm S, Subramaniam B. Exploring socio-cognitive mindfulness in the context of sustainable consumption. Sustainability. 2019;11(13):3692.

Rossmann A, Ranjan K, Sugathan P. Drivers of user engagement in eWoM communication. J Services Market. 2016;30(5):541–53.

Yan S, Wu L, Wang P, Wu HC, Wei G. E-WOM from e-commerce websites and social media: which will consumers adopt? Electron Commerce Res Appl. 2016;17:62–73.

Chekima B, Chekima S, Wafa S, Igau O, Sondoh S. Sustainable consumption: the effects of knowledge, cultural values, environmental advertising, and demographics. Int J Sust Dev World. 2016;23(2):210–20.

Chetioui Y, Benlafqih H, Lebdaoui H. How fashion influencers contribute to consumers’ purchase intention. J Fash Mark Manag. 2020;24(3):361–80.

Kadic-Maglajlic S, Arslanagic-Kalajdzic M, Micevski M, Dlacic J, Zabkar V. Being engaged is a good thing: understanding sustainable consumption behavior among young adults. J Bus Res. 2019;104:644–54.

Amin H, Rahman AA, Razak DA, Rizal H. Consumer attitude and preference in the Islamic mortgage sector: a study of Malaysian consumers. Manag Res Rev. 2017;40(1):95–115.

Zaman M, Park H, Kimand Y, Park S. Consumer orientations of second-hand clothing shoppers. J Glob Fash Market. 2019;10(2):163–76.

Husnain M, Toor A. The impact of social Network marketing on consumer purchase intention in Pakistan: consumer engagement as a mediator. Asian J Business Accounting. 2017;10(1):167–99.

-U. Narimawati, J. Sarwono, D. Munawar and M. Budhiningtias, Metode Penelitian dalam Implementasi ragam Analisis, Yogyakarta: Andi, 2020.

-J. Hair and B. Babin, Multivariate data analysis, Cengage: Cengage, 2018.

Sarstedt M, Hair JF, Cheah HJ, Becker MJ, Ringle CM. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas Mark J. 2019;27(3):197–211.

Ghozali I. Aplikasi Analisis Multivariete Dengan Program IBM SPSS 23 (Edisi 8). Semarang: Badan Penerbit Universitas Diponegoro; 2016.

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. United States of America: SAGE Publications Inc; 2021.

-Indrawati, Metode Penelitian Manajemen dan Bisnis Konvergensi Teknologi Komunikasi dan Informasi, Bandung: Refika Aditama, 2015.

Henseler J, Ringle CMCM, Sarstedt M. Testing measurement in variances of composites using partial least squares. Int Mark Rev. 2016;33(3):405–30.

-Sarwono, Membuat Skripsi, Tesis, dan Disertasi dengan Partial Least Square SEM (PLS-SEM), Yogyakarta: Andi, 2015.

Shang S, Wu Y, Sie Y. Generating consumer resonance for purchase intention on social network sites. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;69(1):18–28.

Gvili Y, Levy S. Consumer engagement with eWOM on social media: the role of social capital. Online Inf Rev. 2018;42(4):482–505.

Gabriella DR. Mindful consumption behavior on second-hand fashion products: intervariable influence analysis of stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) Model. Asean Marketing J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.2002/amj.v13i1.13229.

Raj A, Goswami MP. Is fake news spreading more rapidly than Covid-19 in India? J Content Commun Commun. 2020;11:208–20.

Joshi Y, Srivastava A. Examining the effects of CE and BE on consumers’ purchase intention toward green apparels. Young Consumers. 2019;21(2):255–72.

Filieri R, Javornik A, Hang H, Niceta A. Environmentally framed eWOM messages of different valence: the role of environmental concerns, moral norms, and product environmental impact. Psychol Mark. 2021;38(3):431–54.

Sudbury-Rileya L, Kohlbacher F. Ethically minded consumer behavior: scale review, development, and validation. J Bus Res. 2016;69(8):2697–710.

Prothero AD. Sustainable consumption: opportunities for consumer research and public policy. J Public Policy Mark. 2011;30(1):31–8.

-Apparel Global Market. The Business Research Company. 20 Apr 2023. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/clothing#:~:text=The%20Global%20Apparel%20Market%20was,at%20%24652.94%20billion%20in%202023..

-G. Jones and S. Yu. Professor Ronald W. Jones and his influence on Asia Pacific economics," 21 Jun 2021.https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/clothing#:~:text=The%20Global%20Apparel%20Market%20was,at%20%24652.94%20billion%20in%202023..

Mulet-Forteza C, Lunn E, Merigo J, Horrach P. research progress in tourism, leisure and hospitality in Europe (1969–2018). Int J Contemp Hosp Manag. 2021;33(1):48–74.

-Bisnis.com, BPS Catat Nilai Impor Pakaian Bekas Capai Rp4,21 Miliar pada 2022 Artikel ini telah tayang di Bisnis.com dengan judul "BPS Catat Nilai Impor Pakaian Bekas Capai Rp4,21 Miliar pada 2022, Klik selengkapnya di sini: https://ekonomi.bisnis.com/read/20230312," 12 Maret 2023. https://ekonomi.bisnis.com/read/20230312/257/1636405/bps-catat-nilai-impor-pakaian-bekas-capai-rp421-miliar-pada-2022.

Andersen N. Mapping the expatriate literature: a bibliometric review of the field from 1998 to 2017 and identification of current research fronts. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2019;32:4687–724.

Van Eck N, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Sciencetometrics. 2010;84(2):523–38.

A. I. Susanty, S. Artadita, M. Pradana, T.-K. Neo, M. Neo and A. Amphawan. Twenty Years of Cooperative Learning: A Data Analytic with Bibliometric Approach. International Conference Advancement in Data, 2022. pp. 1–5,

Gaviria-Marin M, Merigo JM, Popa S. Twenty years of the journal of knowledge management: a bibliometric analysis. J Knowledge Manag. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2017-0497.

Pradana M, Elisa HP, Utami DG. Mental health and entrepreneurship: a bibliometric study and literature review. Cogent Business Manag. 2023;10(2):222.

Ruiz-Real JL, Uribe-Toril J, Valenciano JDPV, Manso JRP. Ibero-American research on local development. an analysis of its evolution and new trends. Multidiscipl Digital Publ Instit (MDPI). 2019;1:1–16.

-RakyarMerdeka, Keberlanjutan Produksi dan Konsumsi sebagai Solusi dari 3 Krisis Dunia," 27 Dec 2022. https://rm.id/baca-berita/nasional/154708/keberlanjutan-produksi-dan-konsumsi-sebagai-solusi-dari-3-krisis-dunia.

-Detik.com, "10 Negara Penghasil Sampah Plastik Terbanyak di Dunia, Indonesia Nomor Berapa? Baca artikel detikedu, 10 Negara Penghasil Sampah Plastik Terbanyak di Dunia, Indonesia Nomor Berapa?25 Aug 2022. https://www.detik.com/edu/detikpedia/d-6253565/10-negara-penghasil-sampah-plastik-terbanyak-di-dunia-indonesia-nomor-berapa#:~:text=Jakarta%20%2D%20Sampah%20plastik%20masih%20menjadi,untuk%20lingkungan%20maupun%20makhluk%20hidup..

United Nations Environment Programme. Sustainable consumption and production: a handbook for policymakers 4 May 2015. https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/9660.

Akenji L, Bengtsson M, Chiu A, Fedeeva Z, Tabucanon M. Sustainable consumption and production a handbook for policymakers. United Nations Environ Program. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1340/2.1.4203.8569.

Ari I, Yikmaz RF. Chapter 4—Greening of industry in a resource- and environment-constrained world,’’ in Handbook of Green Economics. Turkey: Academic Press; 2019. p. 53–68.

-World Economic Forum. Why responsible consumption is everyone’s business. 17 Sept 2019. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/why-responsible-consumption-is-everyone-s-business/.

Vermeir I, Verbeke W. Sustainable food consumption: exploring the consumer “attitude-behavioral intention” gap. J Agric Environ Ethics. 2006;19(2):169–94.

Carrington MJ, Neville B, Whitwell GJ. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behavior of ethically minded consumers. J Bus Ethics. 2010;97(1):139–58.

Vermeir I, Verbeke W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol Econ. 2008;64(3):542–53.

Eck NJV, Waltman L. VOSviewer manual. Netherlands: Universitiet Leiden; 2022.

Luchs M, Naylor RW, Irwin JR, Raghunathan R. The sustainability liability: potential negative effects of ethicality on product preference. J Mark. 2010;74(5):18–31.

Belz FM, Peattie K. Sustainability marketing: a global perspective. New York: Wiley; 2012.

Kotler P, Kartajaya H, Setiawan I. Marketing 3.0: from products to customers to the human spirit. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

Liu X, Zhu D. Bibliometric analysis of sustainable supply chain management literature: a research overview. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2018;134:169–78.

Forbes. Who Are The 100 most sustainable companies Of 2020?," 21 Jan 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/samanthatodd/2020/01/21/who-are-the-100-most-sustainable-companies-of-2020/?sh=6307fe0414a4.

Yan Q, Wu S, Wang L, Wu P, Chen H. E-WOM from e-commerce websites and social media: which will consumers adopt? Electron Commerce Res Appl. 2016;17:62–73.

Chen T, Chai L. Attitude toward the environment and green product. Manag Sci Eng. 2010;4(2):27–39.

Haryono S. Mengenal Metode structural equation modelling (SEM) Untuk Penelitian Manajemen Menggunakan AMOS. Jurnal Ekonomi dan Bisnis STIE YPN. 2014;7(1):23.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Telkom University for supporting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Arina Ilmalhaq wrote the initial article and analyzed the data. Mahir Pradana arranged the initial concept, and wrote the final article. Nurafni Rubiyanti conducted the software and visualized the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

An ethics approval was not required for this study as the data is not considered to be sensitive or confidential in nature. Vulnerable or dependent groups were not included. The subject matter was limited to topics that are strictly within the professional competence of the participants. Participants gave their informed consent by conducting the study, i.e., by starting (completing) the online questionnaire.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ilmalhaq, A., Pradana, M. & Rubiyanti, N. Indonesian local second-hand clothing: mindful consumption with stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. Discov Sustain 5, 251 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00481-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00481-2