Abstract

Since the late twentieth century, the global fashion industry has been increasingly embracing the business model known as fast fashion. Characterised by rapid production cycles, fleeting trends, low-cost garments and large-scale production, fast fashion seems to meet consumer demand for affordable and trendy clothing. However, its environmental impact as a major polluter poses significant challenges to sustainability and circularity initiatives. This article presents the results of a systematic literature review, exploring the unsustainable consequences of fast fashion, focusing on both demand and supply side, from a geographical perspective. Using a Global North–Global South framework, it explores differences in socio-economic structures, consumption and production patterns, access to resources and environmental impacts. The analysis suggests that a fair and equitable transition towards a sustainable and circular fashion industry will require the links between business, society and nature to be reconsidered, to avoid perpetuating the inequalities associated with the global linear capitalist economy. The findings highlight the importance of both markets and institutions in sustainable growth. In the Global North, the most frequently discussed topics relate to investment and research and development with respect to new technologies or system innovations often with the support of well-structured political guidance. Conversely, in the Global sustainable initiatives tend to be scattered, country-specific and intricately tied to particular socio-economic and cultural contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As Payne outlines [1], fashion is both an industrial and a cultural phenomenon that is deeply intertwined with the converging environmental, social and economic challenges of the twenty-first century. Following World War II, when production shifted from the home or small workshops to factories orientated towards mass production, fashion became one of the world’s largest industries. Today, it is a major global and globalised industry, characterised by ‘low predictability, high impulse purchase, shorter life cycle, and high volatility of market demand’ [2].

The term ‘fast fashion’ was coined in the 1990s, when the Spanish brand Zara first opened a store in New York and quickly emerged as a standout and highly imitable model of efficiency and speed.

The rise of fast fashion was primarily driven by changes in consumer behaviour and increased fashion consciousness, coupled with the transition of mass-production globalised retailers from a production—to a market-centric approach [3]. Direct engagement between retailers and consumers was essential for maintaining the industry pace. In particular, the late 1990s saw a surge in demand for fashion, fuelled by the popularity of fashion shows and the shift to shopping as a form of entertainment [4]. Mass-production retailers such as Zara, H&M, UNIQLO, GAP and Primark Forever 21 and Topshop expanded rapidly, due to globalisation, and met growing demand by swiftly delivering ‘high fashion at a low price’, within a ‘throw-away market’ paradigm [3, 5]. Vertical integration was adopted to reduce production times and promote flexibility, collaboration and communication in accordance with more complex global supply chains [6]. The late 1990s also marked the advent of e-commerce, with fast fashion retailers such as H&M entering the digital arena [4]. E-commerce furthered the globalisation and democratisation of fast fashion, making products and services more accessible across diverse and international markets [7]. Retailers leveraged e-commerce to reduce purchasing and supply management costs, improve communication strategies and enhance competitiveness through innovation. For consumers, e-commerce simplified purchasing decisions, leading to time and cost savings [8]. The 2020 pandemic, resulting in a significant economic downturn for fashion companies [9], accelerated the adoption of e-commerce as a crucial business solution and primary source of market innovation [10]. Chinese fashion retailers such as Temu and Shein pushed this model a step further, with nearly exclusive online sales.

Notwithstanding the advantages of this new business model, it also presented significant disadvantages. In particular, the technological innovations, GDP growth, globalisation and shifts in retail markets that have arisen as a result of fast fashion have introduced several adverse environmental and ecological impacts [11]. Considering climate change, the fashion industry is accountable for 8–10% of global greenhouse gas emissions –a figure projected to increase by 60% by 2030, according to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change [12]. The UNEP has also blamed fast fashion for triggering the ‘triple planetary crisis’ [6]. In more detail, it is responsible for the consumption of vast quantities of raw materials, including farmland and fossil fuels (especially oil), and the conversion of plastic fibres [13]. Other impacts relate to water depletion and pollution. For instance, the extensive use of chemical compounds and the incineration of synthetic plastic fibres (i.e., polyester, nylon, acrylic), make fashion the second-largest contributor to water pollution after agriculture [14].

Fast fashion’s linear model of production shows a contrasting dynamic when viewed from a Global North–Global South perspective. Derived from the ‘Third World’ model introduced by the United Nations in the 1940s, the terms ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’ describe regions that are socio-economically and politically opposed [15]. The Global South encompasses economically unstable and underdeveloped countries characterised by a low average per capita income, high disparity in living standards and limited access to resources (leading to a heavy reliance on primary product exports). Conversely, the Global North encompasses countries with a high average per capita income, advanced technology and infrastructure, and macroeconomic and political stability [15,16,17].Footnote 1 These differences stem from a global capitalist economy that relies on the ‘economy-first model of development’. The integration of the Global South (formerly referred to as the Third World) into this model began in the 1950s, with the emergence of decolonisation movements. However, the enduring social and economic effects of colonialism, coupled with continuous dependency on former colonial ties and development strategies emulating the virtuous model of developed countries according to the path-dependency principle, have led to the perpetuation and sharpening of inequalities in global governance, economic development and international relations [18,19,20,21]. As highlighted by Hurrell and Kingsbury (1992) [22], this imbalance has become a significant source of conflict between the Global North and the Global South, especially concerning the environment. The COP27 (2022) stands as a stark example of the concerns expressed by the Global South regarding the unequal distribution of responsibilities and burdens in climate change mitigation efforts. Such political and socio-ecological inequalities also contribute to shaping production-consumption patterns [23].

These considerations extend to the global fashion industry, representing a crucial player in the global economy whose hazardous make-take-waste paradigm yields cumulative negative effects that are unevenly distributed across world regions.

Fast fashion’s high pace of overproduction and ‘purchase-discard’ consumption model result in an abundance of unwanted clothes, contributing to a significant mass of textile waste [24]. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, the average American consumer generates 82 pounds of textile waste each year [25].

To address the issue of overproduction, efforts have been made to implement circular economic principles, resulting in a proliferation of global exports of second-hand clothing from the Global North to the Global South [24, 26]. However, this practice of reuse, known as the ‘international second-hand clothing trade’ [27], represents the human tendency to merely ‘export or displace ecological problems, rather than truly solve them’ [28]. In fact, the flow of international second-hand clothing from the affluent Global North to the developing Global South constitutes a form of pollution shifting or waste dumping, potentially inflicting damage on the receiving nations. Evidence of this phenomenon lies in the qualitative difference in donated garments between international markets: high-quality garments are acquired by charities or companies in the Global North and resold locally, while medium-quality garments are exported to Eastern European retail shops and low-quality items find their way to Africa, Asia and South America [29, 30]. Indeed, much of the used clothing that is exported from the Global North to the Global South lacks market value and ends up as waste in water streams, landfills, oceans or incinerators. This troubling issue was reported by ‘Trashion’ [31], which discovered that approximately 50% of the 600,000 kg of used clothing exported by Belgium to Kenya in 2021 was waste that could be neither resold or recycled.

Furthermore, challenges may arise even when high-quality clothes are traded in Global South markets. The volume and low prices of exported clothing, facilitated by political agreements on the trade of used clothing (i.e., the new post-Cotonou agreement, the ‘Everything but Arms’ initiative), hinder the growth of local textile industries. Rather than promoting employment opportunities, local product consumption and economic development, this fosters a heavy reliance on the Global North and contributes to the marginalisation of residents in the poorest countries [32, 33].

The extensive asymmetries in the fast fashion industry between the Global North and the Global South, particularly in terms of sourcing and the generation and disposal of waste, hinder sustainable environmental and economic development and the transition towards a circular economic model [34]. Therefore, to prevent the perpetuation of colonialist-like power dynamics (as evident in the global waste trade often referred to as ‘ecological imperialism’ [35]), discussions of sustainable development and circularity must prioritise justice and address inequalities, to meet diverse needs and visions across the globe [34, 36]. Echoing Boenhhert’s (2015) [37] perspective on the circular economy as a comprehensive approach to redesigning economic and social relations, a rebalancing of relations between the Global North and the Global South cannot overlook power dynamics. These dynamics are evident in not only the economic imperative to reduce and improve the quality of production and consumption, but also the circular economy's endeavour to ‘close the loop’, merging economic growth with sustainability [38].

The present analysis delves into the unequally distributed environmental impacts associated with the fast fashion industry, considering market interactions between consumers (i.e., demand side) and producers (i.e., supply side). Furthermore, it situates these interactions within the broader context of Global North–Global South power dynamics, as reflected in the economy-first model of development. The analysis not only uncovers the unsustainable and geographically diverse impacts of fast fashion, but it also sheds light on emerging strategies and initiatives in the discourse on fashion and sustainability. Within this context, the Global North and the Global South are considered two poles in which exchanges (or a lack thereof) of initiatives, knowledge and strategies may occur among consumers and producers.

In the following section (Sect. 2), we present our research questions and explain our methodological choice of a systematic literature review (SLR). We also outline the protocol used to answer our research questions, which resulted in the creation of analytical clusters. Section 3 delves into the qualitative findings of the SLR, dedicating specific subsections to the key narratives that emerged from the cluster analysis. Section 4 provides a thorough discussion of the results obtained, drawing insights for the multilevel gap between the Global North and the Global South. Finally, Sect. 5 presents concluding remarks regarding the shaping of a future discourse aimed at achieving a globally equitable and sustainable fashion industry, encompassing both production and consumption.

2 Research question

In the present study, we analysed the phenomenon of fast fashion through two distinct yet complementary lenses: (i) consumer and producer perspectives, rooted in (ii) a macro geographical focus distinguishing between the Global North and the Global South. Starting with a review of the literature, our exploration mainly centred on the environmental impact and unsustainability of the growing fast fashion industry, emphasising regional disparities. The research question explored both production and consumption, addressing the widening gap between the Global North and the Global South fostered by the fast fashion industry. Specifically, the literature review aimed at answering the following questions:

-

How does the empirical divide between the Global North and the Global South manifest in the economic literature on fast fashion, particularly in analyses of consumers and producers?

-

Are producers from the Global North and the Global South concerned about the unsustainable environmental impacts of fast fashion? Are they making efforts to transition their businesses towards more circular models? What factors influence consumer awareness, intentions and behaviours towards fast fashion? Are there notable differences or similarities between the Global North and the Global South regarding these aspects? Are there ongoing initiatives promoting sustainable consumption patterns?

-

What does the revised literature reveal about the role of globally adopting circular consumption and production practices in the fashion industry in bridging the Global North–Global South divide?

2.1 Methodology

The core of the qualitative-quantitative analysis was an SLR. The SLR methodology, as outlined by Moher et al. [39], relies on a ‘clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review’ [39]. This method is particularly useful for revealing the current state of the art on a topic and identifying gaps and areas requiring further research [40]. Given the complexity and novelty of the selected topic, we deemed an SLR most suitable for addressing our research questions, as it would allow us to determine a literary and bibliographic framework within which to identify relevant emerging narratives. Papers were identified following the PRISMA protocol, which outlines a specific flow of information across four research stages.

The flow diagram depicted in Fig. 1 outlines the methodological steps (i.e., identification, screening, eligibility, inclusion) [20] of the SLR. These steps, starting with identification, enabled us to select relevant publications to address our research questions.

2.2 Identification

The identification process relied on the electronic database of scholarly publications Scopus, which allowed us to search across titles, abstracts and keywords in the literature. After deeming search terms such as ‘fast fashion AND Global North AND Global South’ too narrow in scope, and terms such as ‘fast fashion AND global value chain’ too broad, we ultimately selected the keyword search ‘fast fashion AND sustainability’.

The research spanned the years 2009–2023, with 2023 chosen as the end date in order to include the most recent studies. However, due to the temporal limitations of the 2023 dataset, for which collection ceased in March of that year, its representativeness in the graph is inherently limited. The year 2009 was chosen as the starting point as it marked the onset of the effects of the first globalisation crisis (beginning in October 2008), bringing to light the uneven development of the economy, the consequences of sourcing goods and services globally and the flow of capital [41]. Figure 2 depicts the annual growth in fast fashion and sustainability publications over the study period.

Ultimately, our search resulted in a set of 293 publications, which we transferred to a Microsoft Excel file for the purposes of manual screening.

2.3 Screening

Screening and selection were performed manually, through a title and abstract review of the 293 papers. Eighty-one papers were excluded on the basis of their irrelevance to the subject matter. Specifically, to answer our research question and narrow the scope of the review our focus was on economic publications, addressing the impact of the fast fashion linear versus circular production and consumption model, and centred on: consumer awareness and/or behaviour and/or preferences, producer/retailer/brand marketing strategies and/or circular business models, and the interaction between consumers and producers. Systematic reviews were also included, as these offered an overview of the publishing landscape [42, 43].

2.4 Eligibility

Each of the remaining 212 papers were assessed for eligibility, with the aim of rooting the SLR within Global North–South dynamics. Only those publications that had a clear geographical focus, i.e., context set in either Global South or Global North countries, or in a comparative approach were included. Papers that addressed mere consumers’/producers’ trends or advancement patterns and strategies towards sustainability, without discerning differences between the Global North and the Global South, or without rooting their analysis in a certain geographical context were excluded.

A set of 117 eligible papers was identified, comprised of publications focused on: (i) consumers, producers, or consumers and producers; and (ii) the Global North, the Global South or a Global North–Global South comparison.

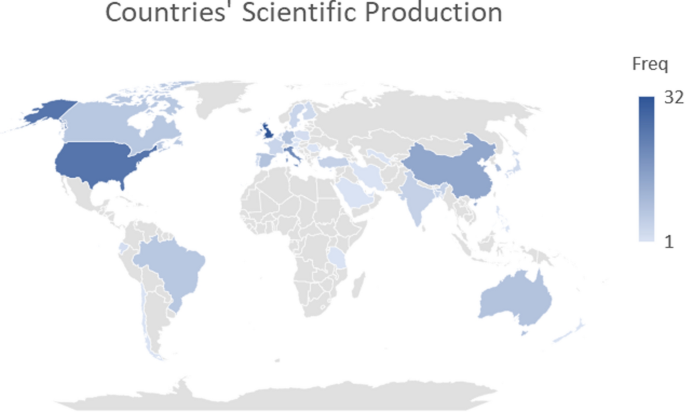

The dataset was further sorted according to countries’ unique contributions to the scientific literature on fast fashion and sustainability, providing an overview of the distribution of geographical areas present in our identified publication set. The 117 research articles originated from 37 countries, representing both the Global North and the Global South. However, as Fig. 3 shows, certain countries contributed more significantly, as indicated by the dark blue colour (e.g., the UK with 32 articles; the US with 25; China with 14; South Korea with 9; Australia with 8; Brazil with 7), while the contribution of other countries was less significant (e.g., Japan with 3 articles, Ecuador with 2; Chile, Saudi Arabia, Tanzania, the Philippines, Croatia, Ireland and the Czech Republic with 1).

2.5 Inclusion

The 117 papers were categorised into four clusters, according to their focus: (i) consumers in the Global North, (ii) producers in the Global North, (iii) consumers in the Global South and (iv) producers in the Global South. These analytical clusters were not created using algorithms or inferential methods, but established qualitatively, with the results interpreted at two levels: (i) market dynamics and interactions (consumers and/or producers; (ii) geographical dynamics and interactions (i.e., Global North and/or Global South). Some papers were assigned to more than one of the abovementioned clusters.

Subsequently, the abstract of each paper was read in order to identify emerging narrative for each cluster of articles.

The following section reports the findings from the qualitative analysis of the 117 identified papers, organised according to each conceptual cluster. The first subsection reports the narratives of papers concerning the Global North and consumers (n = 28 publications from 2014–2023). The second subsection describes the narratives of papers discussing the Global North and producers (n = 24 publications from 2009–2023). Subsections 3 and 4 analyse Global South narratives. Section 3 focuses on consumers (n = 11 publications from 2017–2022) and Sect. 4 focuses on producers (n = 11 publications from 2017–2021).

The final subsection explores the narratives of papers pertaining to more than one of the abovementioned clusters. The content of these papers determined five further clusters of analysis: (i) the Global North and producers and consumers (n = 15 from 2016–2023); (ii) the Global South and producers and consumers (n = 5 publications from 2016–2022); (iii) the Global North versus the Global South and consumers (n = 3 from 2011–2022; (iv) the Global North versus the Global South and producers (n = 14 publications from 2016–2022); and (v) the Global North versus the Global South and consumers and producers (n = 6 from 2018–2022).

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of articles among the conceptual clusters, showing the frequency of articles per cluster.

3 Findings

Figure 5 provides a visually concise summary of the SLR findings that shall be reported and discussed in the following sections. The vertical axis depicts upstream and downstream issues, while the horizontal axis represents the Global North and the Global South. Within each quadrant, the identified narratives are displayed. The upper left quadrant focuses on Global North consumer narratives, while the upper right quadrant represents the Global South consumer cluster. The lower left quadrant reflects Global North producer narratives, and the lower right quadrant pertains to Global South producers. The axes delineate overlapping narratives. The vertical axis (i.e., upstream and downstream) contains cross-cutting narratives for consumers (i.e., upstream) and producers (i.e., downstream), for both the Global North (up) and Global South (down). The horizontal axis (Global North and Global South) represents narratives cross-cutting the producer and consumer categories in the Global North (left) and Global South (right). The circle in the centre regroups the narratives encompassing all four quadrants: the Global North, the Global South, consumers and producers.

3.1 Global North and consumers

The most frequent narrative in this category explored socio-cognitive aspects of consumer behaviour within the framework of the rational economic agent. Terms such as 'consciousness’, ‘knowledge’, ‘cognition’, ‘intentions’, ‘attitude’ and ‘behaviour’ frequently underscored the significance of the socio-cognitive sphere in matters of consumer preference. The central question usually revolved around how ‘consumers’ level of environmental consciousness impacts their purchase decisions and consumption behaviour’ [44], investigating potential value-action gaps or intention-behaviour gaps.

Papers [45,46,47,48,49,50] often analysed empirical data obtained through interviews, surveys and consumer questionnaires. These methods were applied not only to determine consumer preferences, but also explored existing knowledge and attitudes, providing empirical evidence to support initiatives to promote more environmentally friendly purchasing behaviors. Specifically, considering the environmental risks associated with the fast fashion industry, the focus on raising consumer consciousness was found to align with the theme of responsible consumption within a circular bioeconomy perspective. However, external factors (e.g., stressful events such as COVID-19) can impact consumer behaviour, encouraging impulsive buying [49]. The data indicated a consumer preference for sustainable fashion items, while revealing a lack of accurate and transparent knowledge among consumers about all stages of the supply chain [51]. Additionally, some papers found that consumer preferences did not automatically translate into purchasing behaviour, as consumer willingness to pay also played a key role in determining such decisions, alongside with cognitive and behavioural factors [45, 52]. Despite this complexity, consumers were found to exhibit a willingness to pay higher prices for sustainable products, suggesting a potential for sustained market volume [50].

The studies in this group also explored consumers’ demographic characteristics, focusing particularly on generational cohort and gender. Concerning generational cohort, the papers primarily centred on Generation X, whose members (i.e., millennials) are most exposed to the intention-behaviour gap: while overconsuming fast fashion, they are also increasingly sensitive to sustainability issues [53]. Thus, education about sustainable production and responsible consumerism in the clothing industry was identified as a key factor for this cohort, as highlighted by a case study about an educational project conducted in Germany [54]. With respect to gender, women were identified as more ‘careful’ about their responsible consumption, showing a preference for slow fashion apparel and garments [45, 51], or at least appearing ‘more knowledgeable about this topic than men’ [55].

Within the analysis of consumer purchasing choices, slow fashion also emerged as an intriguing research trend [52]. Some papers presented interesting case studies. For instance, Holgar [56] used wardrobe research to empirically test consumers’ everyday clothing practices, and Polajnar and Šrimpf Vendramin explored textile waste management among Ljubljana residents and the waste-management network in Slovenia [57].

3.2 Global North and producers

The most explored narrative in this cluster pertained to the identification of solutions and alternatives concerning circular business models, sustainability, transparent global value chains, and waste and emission reductions, aimed at a paradigm shift in the fashion industry towards more conscientious and circular business practices. For instance, rethinking production modes and supply chains could occur by embracing a multi-echelon closed-loop supply chain (CLSC) [58]. Such an approach would aim at maintaining market competitiveness while promoting sustainable development [58]. Studies analysed major global fashion companies, in—both the luxury and mass market sectors. Transformation was recognised as necessary for meeting evolving consumer demands (characterised by a growing sensitivity to environmentally friendly products), to comply with supranational and international strategies (e.g., the UN Fashion Charter and the Fashion Pact, the EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles) and to participate in sustainability initiatives (e.g., European Textile Network) [59,60,61,62].

In contrast, practices such as ‘greenwashing’ and ‘greenhushing’ were recognised as limiting fashion firms' sustainable production opportunities and market competitiveness, as well as positive consumers perception towards them. Therefore, to achieve a truly circular approach, these practices must be replaced by genuine green marketing strategies [63,64,65]. Strategies such as waste management, recycling, by-products reduction, the use of green technologies, and rental platforms were recommended. For instance, rental platforms in Canada were found to be positively linked to sustainable fashion [66]. To reverse the make-take-waste paradigm, the Swedish fashion industry adopted circular economy principles in its supply chain [67]. Additionally, the German second-hand clothing industry used digitalisation to establish a competitive business model [68]. Given the need to close the loop of the linear fashion scheme, new processes and transaction schemes were also explored. The transition towards a slow-fashion production paradigm was recognized to entail a radical redefinition of value propositions, emphasising craftsmanship, nature and localism [60, 69], guided by transparent business practices and commercial sustainability [70], following the 3Rs (i.e., reduce, reuse, recycle) [71]. This aligns with the approach developed by the French national program for managing post-consumer textiles and clothing, which, promoted innovation in recycling practices through extended producer responsibility policies [72].

Other papers focused on specific business trends, such as those observed in the luxury fashion sector, which has embraced ethical and sustainable measures prioritizing distinction and recycling [73, 74]. Moreover, the emerging ‘eco-chic’ trend highlights that long-lasting and environmentally friendly garments are not restricted to luxury brands, but may also be produced by mass retailers [75].

3.3 Global South and consumers

The environmental challenges and repercussions of the fast fashion industry are located and widespread throughout the Global South. It is in this region that Western companies typically concentrate their fast fashion production processes and discard their used clothing. These issues were addressed from the perspective of consumers in this region, analysing their concerns and engagement. One effective strategy highlighted for mitigating the negative impacts of excessive clothing production and disposal was the establishment of a new sustainable consumption model to prolong product life cycles. Such models might be achieved through the promotion of reuse, recycling and resale activities among consumers, which have already gained traction within the second-hand clothing market. In Africa, for instance, many individuals were found to wear second-hand garments exported from the Global North [76]. Additionally, in the Global South, the embrace of authentic elements inherent to small village settings and local communities (i.e., nature, history, culture, traditions) was recognised as a viable approach to combatting consumerism and fostering sustainable practices [77, 78], highlighting a key difference from the narratives focused on the Global North. In the context of the Global North and consumers, the acknowledgment of sustainability practices influenced by cultural collectivist values was observed within a specific community with ties to the Global South: African Americans, whose heritage is marked by specific cultural values contributing to these practices [79].

Another avenue for minimising the environmental impact of the clothing industry while extending garment lifetimes was identified as the promotion of sustainable purchasing behaviours and intentions [80,81,82]. In this regard, slow fashion and eco-fashion emerged as promising approaches. These trends encourage environmentally conscious and responsible consumers by promoting greater product knowledge, active involvement in the clothing creation and design process, and the adoption of circular textile products [80,81,82]. Ultimately, the adoption of these paradigms may also enhance consumer well-being.

3.4 Global South and producers

The first key narrative in this category surrounded the unethical working conditions and sourcing practices within the fast fashion industry. Countries in this region bear the most significant socio-economic consequences of the fashion value chain, as they not only receive the majority of global textile waste, but they also host the most resource-intensive manufacturing processes, as a result of outsourcing [83]. Thus, economic and environmental factors assume greater significance.

The transition towards sustainable business models in the Global South may be hindered by information deficiency. While enterprises in the Global South were found to make significant effort to comply with corporate social responsibility (CSR) models [84], a comparative analysis among young designers based in China, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan showed that producers in the Global South often lack information about sustainability practices and how to implement them [85]. Interestingly, a significant disparity between the Global North and the Global South emerged in the papers, showing that Generation X individuals in the Global North tend to be notably concerned about sustainability issues, while the same is not true for their counterparts in the Global South.

As outlined in the preceding subsection, culture and perceptions play important roles, also among producers. For instance, Remu Apparel, a slow fashion company in Ecuador, promoted the adoption of slow fashion by reconceptualising traditional masculinity [86]. Filipino ukay-ukay culture (i.e., ‘digging up of piles of used clothes until finding a desirable item’ [87]) provides another intriguing example of the importance of the cultural factor.

To foster sustainable growth, producers must focus on the developing circular economic practices in Global South markets. Given the immense scale of some of these markets, (e.g., the textile and garment industry in Brazil [88, 89] and China [90]) businesses must develop a strategic vision for sustainable economic growth.

3.5 Overlapping narratives

Various factors intersect with the categories of consumers and producers in the fashion industry. Through their primary activities of (over)consumption and (over)production, both contribute significantly to environmental degradation, via the generation of waste and the depletion of raw materials, respectively.

In papers examining consumer–producer dynamics in the Global North, a central narrative revolved around the development of a holistic circular business model for fashion, to allow both producers and consumers to embrace the benefits of a circular economy within the fashion industry [91]. Initiatives such as the Dutch circular textile mission and the European Union-funded Horizon 2020 project TCBL (Textile and Clothing Business Labs) were recognised as an example of system innovations in this direction [92, 93]. The simultaneous engagement of producers and consumers was stated to occur through bottom-up and top-down processes [94]. With respect to top-down processes, producers must prioritise the provision of transparent and easily understandable information to consumers [95], while developing products with clear sustainable attributes, in order to demonstrate their commitment to socio-environmental responsibility. Such an approach would not only enhance consumer loyalty and satisfaction, but it would also increase willingness to pay for sustainable product [96, 97]. The brand ECOALF is exemplar in this regard, with a focus on sustainable fashion and effective communication strategies aimed at consumers [98]. Regarding bottom-up processes, papers described that local consumers should actively propose sustainable initiatives for local and/or global implementation [1, 99]. In particular, social manufacturing, which involves consumers directly in the production process through do-it-yourself (DIY) and do-it-together (DIT) practices, was recognised as facilitating the transfer of environmental knowledge and promoting green innovations [100]. Additionally, unsuccessful aspects of consumer–producer interaction were considered, particularly with respect to textile waste management strategies and recycling technology. A case study comparing the UK and Korean recycling systems revealed the latter’s lesser preparedness to address textile waste streams [101]. Moreover, geographical location was found to play a relevant role, as Portugal produces more textile waste than Croatia, leading to a higher environmental impact [102].

Narratives considering consumer–producer interactions in the Global South underscored how the rise of fast fashion in emerging economies has created both sustainability concerns and opportunities. Economic agents in these regions were found to be positively supporting the concept of sustainable fashion and the idea of transformable garments; attitudes, subjective norms and perceptions, and again cultural factors, were considered influential factors in the adoption of sustainable behaviours, such as recycling activities or secondhand [103,104,105], even among distinct sectors, like secondhand luxury fashion [105]. Transparent and informative communication about sustainable practices was found to enhance consumer trust, foster positive feelings and mitigate perceptions of producer hypocrisy [106, 107]. Despite acknowledging the room for improvement in sustainability practices, studies focused on producers and consumers in the Global South highlighted the substantial work required to effectively transform aspirations into feasible solutions. For example, a study in Brazil revealed consumer reluctance, even among those claiming environmental consciousness, to pay a premium for eco-friendly products [107]. Similarly, concerns about production costs, practicality, adaptability, and marketability were found on the production side [103].

Among the papers adopting a comparative geographical perspective (i.e., Global North vs. Global South) with respect to consumers, the analysis aimed at bridging the gap in consumer perceptions and behaviours across the different global regions. On the one hand, consumers from both the Global North and the Global South were found to be positively influenced by eco-fashion in their decision-making and behaviour [108]. However, a notable disparity persists between consumers in the Global North and those in the Global South regarding purchasing intentions, perceptions, and adoption of circular apparel behaviour, with consumers in the Global South facing more significant challenges in this regard [109]. However, similarities were also detected between consumers in different geographical regions, irrespective of their affiliation to the Global North or the Global South. Specifically, individuals residing in certain natural geographies (e.g., islands) tend to be more nature-friendly in comparison to residents in corresponding continental areas, as shown in a study comparing the residents of an island regions in the US and in Ecuador [110].

Papers comparing producers in the Global North with those in the Global South considered the uneven distribution of environmental, ecological and social consequences, recognising the greater impacts suffered by the weaker region (i.e., the Global South), due to the extensive use of petroleum-based fibres and the offshoring of production by fast fashion companies in the Global North. The papers showed that recent business strategies have begun to integrate social and sustainability aspects, emphasising the importance of transparent, circular business practices [111, 112]. This shift was also recognised in Global North firms that have adopted social and environmental sustainability as a selection criterion for their sourcing locations [113] or relocating specific stages of the supply chain [114]. Transnational and multilevel perspectives and localized, cross-border initiatives aimed at tackling unequal ecological consequences (worldwide) are necessary [115]. These initiatives were thought to emerge when supply chains would cease to be organised solely around large retailers and brand-name firms in the Global North, and extend into the Global South. In this regard, the media could play a prominent role in the provision of transparent information aimed at establishing a sustainable global supply chain [116]. Feasible strategies were identified, including: (i) reusing and remanufacturing unwanted second-hand clothing by incorporating local craft and design, as seen among retailers and artisans in Tanzania and fashion remanufacturers and retailers in the UK [117]; and (ii) implementing effective sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) through investments in decarbonisation and energy infrastructure, engagement with suppliers and consumers, and the revaluation of product design standards [118].

In papers taking an all-encompassing approach, initial considerations regarding the fashion industry’s polluting production model, in terms of environmental degradation, are followed by more specific differences concerning ‘onshoring’ versus ‘offshoring’ dynamics: from textile waste to working conditions. These dynamics were investigated by using different research methods: LCA methods to compare global impacts [119], and systematic literature reviews [120, 121] to highlight gaps and themes in the academic literature on global fashion. More advanced areas of research development have also been explored: immersive technologies aimed at educating and sensitizing global audiences about traditional textile companies and responsible consumption of goods, also in countries such China where Generation Z consumers are showing a growing willingness to purchase sustainable clothes [122]. Finally, studies directed attention to all three sustainability pillars (i.e., environmental, social, economic) as important areas for future research and action. In summary, the papers emphasize the need for joint action involving industry, policymakers, consumers and scientists to promote sustainable production and ethical consumption practices, aimed at achieving equity and the UN Sustainable Development Goals [119,120,121,122,123,124].

4 Discussion

This paper has explored the different dynamics of fast fashion in two major regions of the world, based on an SLR. The findings reveal a gap at various levels, in terms of both bibliographic attributes and content. This aspect suggests the existence of differing scholarly attentions and framings in covering the topic.

First, there is a time-lag in the research. Figure 2 illustrates a significant scarcity of relevant research during the years 2009–2015. However, from 2015 onwards, a gradual increase in publications is evident, with a modest peak in 2017. The period 2017–2022 demonstrates exponential growth in the number of annual publications, with a high peak in 2022. These turning points coincide with significant shifts and transformations in the fashion industry, as echoed in the literature. For instance, 2016 was labelled as one of the most ‘disruptive’ years for the fashion market, characterised by shocks, challenges and uncertainty [125]. Moreover, the year 2017 marked a significant shift in the fashion industry, characterised by organic growth and digitalisation, signalling the end of the West's dominance, particularly in European and North American countries, and the emergence of Asia–Pacific and Latin American regions as new leading players in the industry [125, 126]. Interestingly, our dataset reveals that Global South narratives focusing on consumers, producers and consumer–producer interactions began to emerge in the years 2016–2017, whereas narratives focusing on the Global North emerged as early as 2009. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021–2022, there was a notable increase in awareness and action against the impacts of climate change and resource overconsumption [127]. This shift also influenced the discourse around fast fashion, resulting in a specific scholarly focus on sustainable business models, overconsumption, overproduction, unsustainable practices and sustainable consumption behaviours [128, 129]. Notably, each cluster within this specified timeframe spanned 2021 or 2022.

A skewed trend was evident in the distribution of research contributions, whereby the majority of contributions centred on the Global North, with 28 out of 117 focusing on consumers and 24 out of 117 focusing on producers. In contrast, a smaller number of contributions explored the Global South, with 11 out of 117 focusing on consumers and 11 out of 117 focusing on producers. A dual focus on consumers and producers within the same region was more frequently observed than Global North versus Global South comparisons. In fact, the most fruitful space for comparison was that of the Global North, particularly regarding consumer–producer interactions (15 out of 117 papers vs. 5 out of 117 for the Global South). Moreover, only 6 out of 117 papers were comprehensively comparative.

This trend is corroborated by Fig. 3, which illustrates the scientific production by country. In the figure, there is a notable disparity in academic publishing between countries, particularly in the Global South. Unsurprisingly, Brazil and China appear among the top contributors. Both countries are experiencing a demographic megatrend characterised by an expanding middle class [130, 131], leading to increased purchasing power. This megatrend is also likely to impact trends in production and consumption, including demand for apparel [131, 132]. Perhaps for this reason, in the narratives, these two countries were the only ones mentioned as ‘big markets’ where attention was being given to strategic business strategies [88,89,90]. Conversely, more extensive contributions stemmed from countries in the Global North, encompassing countries from Europe, America, Oceania and Asia.

Considering the identified narratives and themes, our findings show that consumers and producers, both in the Global North and the Global South, are identified in literature as sharing concerns about the present and future condition of the fast fashion industry. The narratives explored solutions at various stages of the fashion supply chain, aimed at enhancing environmental awareness; pro-environmental behaviours; and green, circular and transparent economic principles. Notwithstanding the significant challenges required to effectively translate these efforts into viable solutions (due to information asymmetries between the Global North and the Global South; intra-regional and inter-regional interactions between economic actors; differing levels of awareness; and economic, environmental and social interventions in ‘onshoring’ versus ‘offshoring’ dynamics), literature addressing a commitment to achieving a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable fashion industry is evident in the analysis of the literature of both regions, with respect to both consumers and producers. However, the extent of the identified efforts appears to vary.

The development of sustainable production and consumption systems occurs within social and ecological frameworks, and is affected by technological change, information technologies, market and business strategies, and behavioural change [23, 133, 134]. A common trend may be observed in this regard, with slow fashion and eco-fashion (emphasising social responsibility and sustainability) valued in both the Global North and the Global South. These alternatives prioritise the use of local resources, distributed economies, transparent production systems connecting producers directly with consumers, and sustainable products [135, 136], and they have been identified as important avenues for current and future sustainability in both regions [52, 60, 69, 70, 72, 75, 80,81,82, 86].

However, in this eco-humanistic perspective,Footnote 2 different levels of importance are attributed to the two dominating systems [134]—that of values (used here as a proxy for social, environmental, traditional and historical elements) and that of economics (used here as a proxy for business strategies, economic principles, digitalization, behavioral and cognitive characteristics).

In the Global South, waste management initiatives (e.g., those aimed at reuse, recycling and resale), the development of green technologies and circular principles, the adoption of contemporary models of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to address the growing second-hand clothing market, and the exploration of certain behavioural and cognitive characteristic informing environmentally conscious and responsible consumers with strong product knowledge who receive transparent and informative information from producers, may be investigated as economic patterns. Notably, these considerations are embedded in discussions of social and ecological factors, highlighting locality, culture, traditional values and nature. Significantly, change is proposed to stem from local values and social structures, reflecting a bottom-up approach. Such initiatives, originating in local communities, may pertain to producers—as highlighted in the case studies from Ecuador and the Philippines [86, 87]—and/or consumers—as seen in the practice of hand-me-down clothing and sharing [76,77,78], with the aim of promoting green economic development with respect to the environment (social and natural).

Conversely, in the Global North, circular and sustainable initiatives are more strictly aligned with economic considerations, with market strategies informing a circular transition driven by competitiveness and profitability [1, 58, 70]. Thus, efforts are directed towards the abandonment of communicative, business and marketing practices such as greenwashing or greenhushing, in favour of circular economy principles in the supply chain [58, 67], digitalization [68], transparent business practices, the development of commercial sustainability, and the 3Rs principle [71], even when the goal is to promote new values and a localist, collectivistic attitude [60, 69]. Similarly, consumer preferences are explored using cognitive and behavioural components and social characteristics, alongside market considerations (e.g., willingness to pay) [45, 50, 52]. While, only when analysing a specific community interestingly rooted in the cultural heritage of the Global South, the potential and effective role of traditional community values is mentioned [79]. Interactions between producers and consumers with respect to the adoption of sustainability are explored through examples of transparent business models that are openly committed to social and environmental responsibility [96, 98] (i.e., systemic innovations [92, 93]), and consumers' active involvement in production processes [1, 99], rather than attitudes, subjective norms, and perceptions [104, 107]. Even when explored at a national policy level [72], these transformations find their rationale in the necessity to comply with supranational and international strategies (e.g., the UN Fashion Charter and the Fashion Pact, EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles) and sustainability initiatives (e.g., European Textile Network) [59,60,61,62].

Existing inequalities in global governance and economic relations among the Global North and the Global South relations [18,19,20,21,22] are mirrored in the analysis of the approaches each region is taking to achieve sustainability in the fashion industry.

In 2018 Wu et al. [137] observed that the decoupling of developing countries from unsustainable practices was fluctuating and lacking in regularity—a trend echoed in our discussion. In fact, the shift in the fashion industry towards sustainable development predominantly occurs within the developed and politically active Global North. Conversely, in the Global South, this transition is contingent upon country-specific factors, including socio-economic and cultural contexts. In the Global North, structured, innovative and transparent market strategies for sustainable consumption and production patterns are implemented under political guidance. It is imperative that these strategies be adopted globally, extending to the Global South. This may be achieved, for instance, through an active commitment to corporate social and environmental responsibility in sourcing decisions and the integration of the Global South into sustainable supply chain management through investment in decarbonisation and energy infrastructure [111,112,113,114, 118]. Furthermore, there is a need for joint action between the Global South and the Global North at a governmental level, within an inclusive framework [115, 119,120,121,122,123,124]. This is due to the differing capacities of developed and developing countries to address the challenges of unsustainable consumption and production. In the Global North, sustainable development is already reliant on structural systemic innovations and policy guidance [137, 138].

5 Conclusions

If, on the one hand, the present SLR acknowledges that the analysed existing literature on the topic underlines a genuine commitment to the long-term development of a sustainable fashion industry, with attention given to Global North–Global South dynamics (as particularly evident with respect to, e.g., waste and outsourcing), it is notable that this landscape remains fragmented, as highlighted by the discussed temporal and geographical distribution of research.

Emphasising the need to achieve all three pillars of sustainability, and broadening the scope of the investigation to encompass the Global South, future research should employ comparative approaches centred on the creation of a common good (i.e., common interests and solutions) between developed and developing countries [139]. This may involve recognising the unequal consequences of global trends and combining green digitalisation and new technologies with the preservation of local and cultural values to encourage mindful consumption and production (as emphasised, for instance, in the concepts of slow fashion and eco-fashion). Envisioning a comprehensive eco-humanistic vision, the integration of growth and development with the social and natural environment, alongside advancements in science and technology (including ICT and immersive technologies), may result in a sustainable development system worldwide [134].

While our analysis adopted an economic perspective, focusing on the disparity between the Global North and the Global South, we recognise the importance of directing scholars’ attention in challenging existing power dynamics within the traditional economic paradigm, starting with acknowledging the literature gap evident in the differing bibliographic attributes and content narratives according to world region. To strengthen the development of a sustainable and circular fashion industry, while fostering sustainable and socio-ecologically equitable production and consumption patterns, future research must address the gap in environmental responsibility, global governance and economic relations between the Global North and the Global South [21, 23, 138, 140]. Although our research questions did not explicitly address governance, this topic emerged as an interesting analytical thread. Thus, future research could explore the role played by governance in consumer–producer interactions, and its impact on the imbalanced Global North–Global South dynamic. Reflecting on this aspect could yield valuable insights for empirical applications to further progress towards global sustainability targets, emphasising social and ecological considerations alongside economic dynamics of production and consumption. This, in turn, may actively support collaborative initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and the United Nations Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, while also contributing to the creation of new ones.

Data availability

Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Notes

Between the 1960s and 1990s, some Global South countries became developed economies, following industrialisation, technological innovation and a rise in living standards. These countries include South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong—the so-called ‘Asian Tigers’ [15].

According to Michnowski [134] eco-humanism is ‘a partnership-based co-operation for the common good of all people (rich and poor, from countries highly developed and behind in development), their descendants, and natural environment—commonly supported by science and high technology’.

References

Payne A. The life-cycle of the fashion garment and the role of Australian mass market designers. Int J Environ Cult Econ Soc Sustain. 2011;7(3):237–46. https://doi.org/10.18848/1832-2077/CGP/v07i03/54938.

Fernie J, Sparks L. Logistics and retail management, insights into current practice and trends from leading experts. London: Kogan Page; 1998.

Bhardwaj V, Fairhust A. Fast Fashion: response to changes in the fashion industry. Int Rev Retail Distrib Consum Res. 2010;1(20):165–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593960903498300.

Turban E, Whiteside J, King D, Outland J. Introduction to electronic commerce and social commerce. 4th ed. Springer: Springer Texts in Business and Economics; 2017.

Barnes L, Lea-Greenwood G. Pre-loved? Analysing the Dubai Luxe Resale Market. In: Athwal KN, Henninger EC, editors. Palgrave advances in luxury. London: Springer Nature; 2018. p. 63–78.

United Nations Environment Programme. The Triple Planetary Crisis: Forging a new relationship between people and the earth. 2020. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/speech/triple-planetary-crisis-forging-new-relationship-between-people-and-earth. Accessed 22 Aug 2023.

Blázquez M. Fashion shopping in multichannel retail: the role of technology in enhancing the customer experience. Int J Electron Commerce. 2014;18(4):97–116.

Wei Z, Zhou L. E-Commerce case study of fast fashion industry. In: Du Z, editor. Intelligence computation and evolutionary computation: results of 2012 international conference of intelligence computation and evolutionary computation ICEC 2012 Held July 7, 2012 in Wuhan, China. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2013. p. 261–70.

The Business of Fashion & McKinsey & Company. The State of Fashion 2020, Coronavirus Update. 2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Retail/Our%20Insights/Its%20time%20to%20rewire%20the%20fashion%20system%20State%20of%20Fashion%20coronavirus%20update/The-State-of-Fashion-2020-Coronavirus-Update-final.ashx. Accessed 29 Mar 2023.

Bilińska-Reformat K, Dewalska-Opitek A. E-commerce as the predominant business model of fast fashion retailers in the era of global COVID 19 pandemics. Proc Comput Sci. 2021;192:2479–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.09.017.

Anguelov N. The dirty side of the garment industry. Fast fashion and its negative impact on environment and society. New York: CRC Press; 2016.

United Nations Climate Change. UN helps fashion industry shift to low carbon. 2018. https://unfccc.int/news/un-helps-fashion-industry-shift-to-low-carbon. Accessed 27 Aug 2023.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A new textiles economy: redesigning fashion’s future. 2017. https://emf.thirdlight.com/file/24/IwnEDbfI5JTFoAIw_2QI2Yg-6y/A-New-Textiles-Economy_Summary-of-Findings_Updated_1-12-17.pdf. Accessed 23 July 2023.

Quantis International. Measuring Fashion. Environmental Impact of the Global Apparel and Footwear Industries Study. 2018. https://quantis.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/measuringfashion_globalimpactstudy_full-report_quantis_cwf_2018a.pdf. Accessed 29 Aug 2023.

Kowalski AM. Global south-global north differences. In: Leal Filho W, Azul AM, Luciana Brandli L, Lange Salvia A, Gökçin Özuyar P, Wall T, editors. No poverty (encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals). Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 389–400.

Lancaster C. Developing countries: winners or losers. In: Kugler RL, Frost EL, editors. The global century: Globalization and national security. 2nd ed. Washington DC: National Defense University; 2001. p. 653–64.

Odeh LE. A comparative analysis of global north and global south economies. J Sustain Dev Afr. 2010;12(3):338–48.

Hamilton GG, Gereffi G. Global commodity chains, market makers, and the rise of demand-responsive economies. In: Bair J, editor. Frontiers of commodity chain research. Standford University Press; 2009. p. 136–61. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804779760-009.

Gereffi G, Humphrey J, Kaplinsky R, Sturgeon TJ. Introduction: globalisation, value chains and development. In: Gereffi G, Kaplinsky R, editors. IDS bulletin: the value of value chains, vol. 31. 3rd ed. Brighton: Sussex University Institute of Development Studies; 2001. p. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32003001.

Cox RW. A perspective on globalization. In: Mittelman JH, editor. Globalization: critical reflections. Boulder: Lynne Rienner; 1996. p. 21–30.

Mittelman JH. Globalization: critical reflections. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 1996.

Tukker A, Emmert S, Charter M, Vezzoli C, Sto E, Andersen MM, Geerken T, Tischner U, Lahlou S. Fostering change to sustainable consumption and production: an evidence based view. J Clean Prod. 2008;16(11):1218–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.08.015.

Hurrell A, Kingsbury B. An introduction. In: Hurrell A, Kingsbury B, editors. The international politics of the environment. Oxford University Press; 1992. p. 39.

Mathai MV, Isenhour C, Stevis D, Vergragt P, Bengtsson M, Lorek S, Forgh Mortensen L, Coscieme L, Scott D, Waheed A, Alfredsson E. The Political economy of (un)sustainable production and consumption: a multidisciplinary synthesis for research and action. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105265.

Marcello Falcone P, Yılan G, Morone P. Transitioning towards circularity in the fashion industry: some answers from science and future implications. In: Ren J, Zhang L, editors. Circular economy and waste valorization. Industrial ecology and environmental management. Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04725-1_4.

USEPA. Facts and figures about materials, waste and recycling: textiles: material-specific data. 2021. https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data. Accessed 17 May 2022. Accessed 28 ch 2024.

Brooks A. The hidden world of fast fashion and second-hand clothes. London: CPI Group; 2015.

Dryzek J. Rational ecology: environment and political economy. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1987.

Ljungkvist H, Watson D, Elander M. Developments in global markets for used textiles and implications for reuse and recycling. Mistra Future Fashion, IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute PO Box.2018;210(60). http://mistrafuturefashion.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Mistra-Future-Fashion-2018.04-M-Elander-D.3.3.4.1.pdf. Acccessed 3 Apr 2024.

Cobbing M, Daaji S, Kopp M, Wohlgemut V. Poisoned Gifts. From donations to the dumpsite: textiles waste disguised as second-hand clothes exported to East Africa. Hamburg: Greenpeace v.E; 2022. https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-international-stateless/2022/04/9f50d3de-greenpeace-germany-poisoned-fast-fashion-briefing-factsheet-april-2022.pdf. Accessed 17 Aug 2023.

Changing Markets Foundation. Trashion. https://changingmarkets.org/. Accessed 28 Aug 2023.

Frazer G. Used clothing donations and apparel production in Africa. Econ J. 2008;118:1764–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02190.x.

Haggblade S. The flip side of fashion: used clothing exports to the third world. J Dev Stud. 1990;26(3):505–21.

Ashton WS, Farne Fratini C, Isenhour C, Krueger R. Justice, equity and the circular economy: introduction to the special double issue. Local Environm. 2022;27:1173–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2118247.

Cotta B. What goes around, comes around? Access and allocation problems in Global North-South waste trade. Int Environ Agreements: Polit Law Econ. 2020;20(2):255–69.

Corvellec H, Böhm S, Stowell A, Valenzuela F. Introduction to the special issue on the contested realities of the circular economy. Cult Organ. 2020;26(2):97–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2020.1717733.

Boehnert J. Ecological literacy in design education-A theoretical introduction. FormAkademisk. 2015. https://doi.org/10.7577/formakademisk.1405.

Ghisellini P, Cialani C, Ulgiati S. A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J Clean Prod. 2016;114:11–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman JD. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Feak CB, Swales SM. Telling a research story: writing a literature review. English in Today’s Research World; 2009.

Brown G. Beyond the crash: overcoming the first crisis of globalization. 1st ed. Simon and Schuster; 2010.

Salleh S, Thokala P, Brennan A, Hughes R, Booth A. Simulation modelling in healthcare: an umbrella review of systematic literature reviews. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:937–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-017-0523-3.

Jamali D, Karam C. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. Int J Manag Rev. 2018;20(1):32–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12112.

Long X, Nasiry J. Sustainability in the fast fashion industry. Electron J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3486502.

Zhang B, Zhang Y, Zhou P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041646.

Colasante A, D’Adamo I. The circular economy and bioeconomy in the fashion sector: emergence of a sustainability bias. J Clean Prod. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129774.

Cesarina Mason M, Pauluzzo R, Muhammad UR. Recycling habits and environmental responses to fast-fashion consumption: enhancing the theory of planned behavior to predict Generation Y consumers’ purchase decisions. Waste Manag. 2022;139:146–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.12.012.

Palomo-Lovinski N, Hahn K. American consumer perceptions of sustainable fashion, fast fashion, and mass fashion practices. Int J Environ Cult Econ Soc Sustain. 2020;16(1):15–27. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1115/CGP/v16i01/15-27.

Gawior B, Polasik M, Del Olmo JL. Credit card use, hedonic motivations, and impulse buying behavior in fast fashion physical stores during COVID-19: the sustainability paradox. Sustainability. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074133.

Friedrich D. Comparative analysis of sustainability measures in the apparel industry: an empirical consumer and market study in Germany. J Environ Manage. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112536.

Blazquez M, Henninger CE, Alexander B, Franquesa C. Consumers’ knowledge and intentions towards sustainability: a Spanish fashion perspective. Fash Pract. 2020;12(1):34–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2019.1669326.

Chi T, Gerard J, Yu Y, Wang Y. A study of U.S. consumers’ intention to purchase slow fashion apparel: understanding the key determinants. Int J Fash Des Technol Educ. 2021;14(1):101–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2021.1872714.

Cairns MC, Ritch LE, Bereziat C. Think eco, be eco? The tension between attitudes and behaviours of millennial fashion consumers. Int J Consum Stud. 2022;46(4):1262–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12756.

Tama D, Cüreklibatir Encan B, Öndoǧan Z. University students’ attitude towards clothes in terms of environmental sustainability and slow fashion. Tekstil ve Konfeksiyon. 2017;27(2):191–7.

Papasolomou I, Melanthiou Y, Tsamouridis A. The fast fashion vs environment debate: consumers’ level of awareness, feelings, and behaviour towards sustainability within the fast-fashion sector. J Mark Commun. 2023;29(2):191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2022.2154059.

Holgar M. Systemic fashion change and wardrobe research-related tools for supporting consumers. Int J Crime Justice Soc Democr. 2022;11(2):129–42.

Polajnar Horvat K, Šrimpf VK. Issues surrounding behavior towards discarded textiles and garments in Ljubljana. Sustain (Switzerland). 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116491.

Roudbari ES, Fatemi Ghomi SMT, Eicker U. Designing a multi-objective closed-loop supply chain: a two-stage stochastic programming, method applied to the garment industry in Montréal, Canada. Environ Dev Sustain. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-023-02953-3.

Centobelli P, Abbate S, Nadeem PS, Garza-Reyes AJ. Slowing the fast fashion industry: an all-round perspective. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2022.100684.

Abbate S, Centobelli P, Cerchione R. From fast to slow: an exploratory analysis of circular business models in the Italian apparel industry. Int J Prod Econ. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2023.108824.

Martínez-Martínez A, Cegarra-Navarro JG, Garcia-Perez A, De Valon T. Active listening to customers: eco-innovation through value co-creation in the textile industry. J Knowl Manag. 2022;27(7):1810–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2022-0309.

Pérez-Bou S, Cantista I. Politics, sustainability and innovation in fast fashion and luxury fashion groups. Int J Fashion Des Technol Educ. 2022;16(1):46–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2022.2113153.

Adamkiewicz J, Kochańska E, Adamkiewicz I, Łukasik RM. Greenwashing and sustainable fashion industry. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogsc.2022.100710.

Market Research Report Fast track. “Greenhushing”—why are some apparel brands under-reporting or hiding their sustainability credentials? Performance Apparel Markets. 2022;75:4–12.

Bilsel H, Gezgin M. The use of the green marketing concept in brand communications: the case of the H&M fashion brand. In: Sezgin B, Tetik T, Vatanartıran Ö, editors. Transformation of the industry in a brand new normal: media, music, and performing arts. Peter Lang; 2022. p. 79–102.

Amasawa E, Brydges T, Henninger CE, Kimita K. Can rental platforms contribute to more sustainable fashion consumption? Evidence from a mixed-method study. Clean Responsible Consumption. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clrc.2023.100103.

Brydges T. Closing the loop on take, make, waste: Investigating circular economy practices in the Swedish fashion industry. J Clean Prod. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126245.

Derwanz H. Digitalizing local markets: The secondhand market for pre-owned clothing in Hamburg, Germany. Res Econ Anthropol. 2021;41:135–61. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0190-128120210000041007.

Hong J, Chun J. Analysis of designer brands aiming for the value of slow fashion -focused on john alexander skelton and geoffrey B. Small J Korean Soc Cloth Text. 2021;45(1):136–54.

Bray A. Creating a slow fashion collection—a designer–maker’s process. Scope. 2017;15:29–35.

Fitzsimmons S, Ma L, Ulku AM. Incentivizing sustainability: price optimization for a closed-loop apparel supply chain. IEOM Society International; 2019.

Bukhari M, Carrasco-Gallego R, Ponce-Cueto E. Developing a national programme for textiles and clothing recovery. Waste Manag Res. 2018;36(4):321–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X18759190.

Calefato P. In: Muthu SS, editor. Sustainable Luxury and fashion: from global standardisation to critical customisation. environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes. New York: Springer; 2017. p. 107–23.

Cimatti B, Campana G, Carluccio L. Eco design and sustainable manufacturing in fashion: a case study in the luxury personal accessories industry. Procedia Manuf. 2017;8:393–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2017.02.050.

Bruzzi S, Gibson PC. Introduction: the changed fashion landscape of the new millennium. In: Bruzzi S, Gibson PC, editors. Fashion cultures revisited: theories, explorations and analysis. London: Routledge; 2013. p. 1–8.

Sumo PD, Ji X, Cai L. SWOT framework based on fuzzy logic, AHP, and fuzzy TOPSIS for sustainable retail second-hand clothing in Liberia. Fibres Text East Eur. 2022;30(6):27–44. https://doi.org/10.2478/ftee-2022-0050.

Al-Naggar N. Consumable ideologies: designing sustainable behaviours in Kuwait. In: Eluwawalage D, Esseghaier M, Nurse J, Petican L, editors. Trending now: new developments in fashion studies. Leiden: Brill; 2019. p. 343–9.

Febrianti RAM, Tambalean M, Pandhami G. The influence of brand image, shopping lifestyle, and fashion involvement to the impulse buying. Rev Int Geogr Educ Online. 2021;11(5):2041–51.

Collins L, Min S, Yurchisin J. Exploring the practice of african americans’ hand-me-down clothing from the perspective of sustainability”. Int J Soc Sustain Econ Soc Cult Context. 2019;15(1):11–24. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1115/CGP/v15i01/11-24.

Liu A, Baines E, Ku L. Slow fashion is positively linked to consumers’ well-being: evidence from an online questionnaire study in China. Sustain (Switzerland). 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142113990.

Chiu FT. A study in elderly fashion and zero waste clothing design. In: Kuroso M, editor. Human-computer interaction. Perspectives on design. HCI; 2019. p. 427–38.

Shamsi MA, Chaudhary A, Anwar I, Dasgupta R, Sharma S. Nexus between environmental consciousness and consumers’ purchase intention toward circular textile products in India: a moderated-mediation approach. Sustain (Switzerland). 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142012953.

Kuhrana K, Mutu SS. Are low- and middle-income countries profiting from fast fashion? J Fash Mark Manag. 2022;26(2):289–306. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-12-2020-0260.

Nguyen HT, Le Doan MD, Minh Ho TT, Nguyen P-M. Enhancing sustainability in the contemporary model of CSR: a case of fast fashion industry in developing countries. Soc Responsib J. 2020;17(4):578–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-03-2019-0108.

Shen L, Sethi MH. Sustainable fashion and young fashion designers: are fashion schools teaching sustainability? Fibres Text East Eur. 2021;29(5):9–13.

Pohlmann A, Muñoz-Valencia R. Stumbling into sustainability: the effectual marketing approach of Ecuadorian entrepreneurs to reframe masculinity and accelerate the adoption of slow fashion. Crit Stud Men’s Fash. 2021;8(1–2):223–43. https://doi.org/10.1386/csmf_00042_1.

Biana HT. The Philippine Ukay-Ukay culture as sustainable fashion. DLSU B&E Rev. 2020;30(1):154–64.

Anicet A, Dias E. Fashion business oriented for sustainability. In: Almeida HA, Almendra R, Bartolo MH, Bartolo P, da Silva F, Lemos AN, Roseta F, editors. Challenges for technology innovation: an agenda for the future. 1st ed. CRC PRESS; 2017. p. 77–82.

Galatti LG, Baruque-Ramos J. Brazilian potential for circular fashion through strengthening local production. SN Appl Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1487-z.

Zhuang L. The changing landscape for Chinese small business: the case of “Bags of Luck.” EEMCS. 2011;1(1):1–12.

Papamichael I, Voukkali I, Loizia P, Rodrıguez-Espinosa T, Navarro-Pedreño J, Zorpas AA. Textile waste in the concept of circularity. Sustain Chem Pharm. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scp.2023.100993.

Reike D, Hekkert MP, Negro SO. Understanding circular economy transitions: the case of circular textiles. Bus Strat Env. 2023;32(3):1032–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3114.

Marsh J, Boszhard I, Contargyris A, Cullen J, Junge K, Molinari F, Osella M, Raspanti C. A value-driven business ecosystem for industrial transformation: the case of the EU’s H2020 “Textile and Clothing Business Labs.” Sustain Sci Pract Policy. 2022;8(1):263–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2022.2039491.

Jung S, Jin B. Sustainable development of slow fashion businesses: customer value approach. Sustain. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8060540.

Costantini J, Costantini K. Communications on sustainability in the apparel industry: readability of information on sustainability on apparel brands’ web sites in the United Kingdom. Sustain. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013257.

Dabija DC, Câmpian V, Pop RA, Băbuț R. Generating loyalty towards fast fashion stores: a cross-generational approach based on store attributes and socio-environmental responsibility. Oecon Copernic. 2022;13(3):891–934. https://doi.org/10.24136/oc.2022.026.

Moon H, Lee HH. Environmentally friendly apparel products: the effects of value perceptions. Soc Behav Pers Int J. 2018;46(8):1373–84. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6392.

Núñez-Barriopedro E, Llombart Tárrega MD. New Trends in marketing aimed at the fourth sector in the fashion industry. In: Sánchez-Hernández MI, Carvalho L, Rego C, Lucas MR, Noronha A, editors. Entrepreneurship in the fourth sector. Studies on entrepreneurship, structural change and industrial dynamics. Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 245–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68390-0_12.

Durrani M. “People gather for stranger things, so why not this?” Learning sustainable sensibilities through communal garment-mending practices. Sustain. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072218.

Karnad V, Udavier V. Social manufacturing in the fashion industry to generate sustainable fashion value creation. Dig Manuf Technol Sustain Anthropometr Apparel. 2022;9(4):555–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823969-8.00010-1.

Kim CS, Kim KR. A case study comparing textile recycling systems of Korea and the UK to promote sustainability. J Text Apparel Tech Manag. 2016;10(1).

Kalambura S, Pedro S, Paixão S. Fast fashion—sustainability and climate change: a comparative study of Portugal and Croatia. Socijalna Ekologija. 2020;29(2):269–91.

Rahman O, Gong M. Sustainable practices and transformable fashion design–Chinese professional and consumer perspectives. Int J Fashion Des Technol Educ. 2016;9(3):233–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2016.1167256.

O’Reilly S, Kumar A. Closing the loop: An exploratory study of reverse ready-made garment supply chains in Delhi NCR. Int J Logist Manag. 2016;27(2):486–510. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-03-2015-0050.

Barnes L, Lea-Greenwood G. Pre-loved? Analysing the Dubai Luxe resale market. In: Ryding D, Henninger C, Blazquez Cano M, editors. Vintage Luxury Fashion. Palgrave advances in luxury. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2018. p. 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71985-6_5.

Wei X, Jung S. Benefit appeals and perceived corporate hypocrisy: implications for the CSR performance of fast fashion brands. J Prod Brand Manag. 2022;31(2):206–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-04-2020-2850.

Gomes de Oliveira L, Miranda FG, de Paula Dias MA. Sustainable practices in slow and fast fashion stores: what does the customer perceive? Clean Eng Technol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clet.2022.100413.

Ryding D, Caratù M, Vignali G. Eco fashion brands and consumption: is the attitude-behaviour gap narrowing for the millennial generation? Int J Bus Global. 2022;30(2):131–54. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBG.2022.122672.

Gomes GM, Moreira N, Bouman T, Ometto AR, van der Weff E. Towards circular economy for more sustainable apparel consumption: testing the value-belief-norm theory in Brazil and in The Netherlands. Sustain (Switzerland). 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020618.

Pohlman A. The sustainability awareness effect of geography on hedonic fashion consumption and connection with nature—evidence from Galápagos and Hawaii. Crit Stud Men’s Fash. 2021;8(1–2):205–21. https://doi.org/10.1386/csmf_00041_1.

Arrigo E. Offshore outsourcing in fast fashion companies: a dual strategy of global and local sourcing? In: Bilgin MH, Danis H, Demir E, García-Gómez CD, editors. Eurasian business and economics perspectives. Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77438-7_5.