Abstract

The present study investigates the influence of green human resource management (GHRM) on green ambidexterity innovation (GAI) within Spanish wineries, examining the mediating effect of Green Intellectual Capital (GIC) and the moderating role of Top Management Environmental Awareness (TMEA). Building on existing literature, a conceptual model was developed and tested using structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with data collected from 196 Spanish wineries between September 2022 and January 2023. The findings reveal a significant positive relationship between GHRM and GAI, with GIC partially mediating and TMEA positively moderating this relationship. The originality of this study lies in its empirical testing of the proposed model, addressing a previously unexplored area in the field. These results provide valuable insights for both academia and industry, highlighting the importance of integrating environmental considerations into human resource practices to foster innovation and sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In today's ever-evolving commercial landscape, firms are consistently grappling with the imperative to develop and maintain distinct strategic advantages to secure their continuity [1]. This imperative is intensified by the rapid rate of change within industries, which precipitates increasingly ephemeral product lifespans [2]. Concurrently, there is a mounting imperative for businesses to enhance their environmental stewardship [3].

The wine industry, as the context of this study, underscores the crucial relevance of effective environmental management practices due to their significant importance. First, this sector faces numerous climate challenges that threaten its long-term sustainability, such as the impact of climate change and concerns about water and energy scarcity, thus underscoring the need for wineries to adopt sound environmental management strategies to mitigate risks and ensure the long-term viability of the sector [4]. Second, the adoption of good environmental management practices can provide wineries with a competitive advantage, which can be manifested through differentiation of the winery's products, such as offering a diverse range of organic, natural and biodynamic wines [5].

In response to increasing environmental pressures and the strategic importance of environmental management for companies, firms need to broaden their knowledge base on green practices among their employees, this broadening being crucial for developing organizational assets and capabilities related to environmental protection [6]. In this context, green human resource management (GHRM) plays a key strategic role in increasing the ecological knowledge base of employees, which ultimately favors the development of eco-innovations to meet environmental challenges while improving business performance [7]. In particular, this typology of human management refers to the integration of environmental practices and policies into the human resource management functions and processes of an organization, involving consideration of environmental aspects in the hiring, training, performance evaluation and compensation of employees, as well as in internal communication and organizational culture [8].

GHRM involves the integration of environmentally responsible practices into traditional human resource management functions, from recruitment to retirement, with each aspect designed to promote sustainability. In this regard, as Choudhary and Datta [9] highlight, in the recruitment process, companies can prioritize candidates who have demonstrated a commitment to environmental issues and also have experience in sustainability initiatives. In addition, training programs can be developed to educate employees on environmental practices and encourage sustainable behaviors both inside and outside the workplace [10]. Similarly, as Shah et al. [11] point out, performance appraisals can include criteria related to the employee's contribution to the company's environmental goals, compensation schemes can be designed to incentivize green practices, and internal communication strategies can be put in place to foster a culture of environmental awareness, ensuring that all employees understand and are committed to the firm's sustainability goals.

Thus, improving the GHRM can lead to an increase in the ecological stock of workers (Green Human Capital), the improvement of corporate resources and capabilities to meet environmental challenges (Green Structural Capital) and the promotion of the company's relations with its stakeholders to improve environmental performance (Green Relational Capital), thus allowing to promote the set of green intangibles of the organization aimed at protecting the environment, i.e., encouraging Green Intellectual Capital (GIC) [12]. This refers to the knowledge, skills and experiences of employees that contribute to environmental management within the organization, including the development of innovative solutions to environmental challenges and the integration of sustainable practices into daily operations [13]. Strengthening GIC enables fostering an organizational culture of environmental responsibility, which is crucial to achieving long-term sustainability goals and promoting the exchange of green knowledge [14].

In turn, this set of intangibles can subsequently enable companies to improve their ability to develop green innovations based on exploration and exploration together, thus leading to an improved green ambidexterity innovation (GAI) [15]. This refers to an organization's ability to balance and combine the search for new opportunities and experimentation (exploratory innovation) with the improvement and efficiency of existing practices (exploitative innovation) [16]. This dual capability enables companies to innovate in a sustainable manner, simultaneously seeking novel solutions and optimizing current processes [17]. GAI is therefore critical to gaining a green competitive advantage in the marketplace, since by developing both the exploration and exploitation of green innovations, enterprises can respond more effectively to environmental challenges and seize new opportunities for sustainable growth [18].

Notwithstanding the growing academic focus on GHRM, there remains a dichotomy in the extant research concerning this concept. Initially, the scholarly discourse presents a lack of consensus on the nexus between GHRM practices and GAI, as highlighted by Úbeda‐García et al. [19], which calls for more rigorous scholarly inquiry to elucidate this relationship. Thus, although the importance of GHRM in the development of exploratory and exploitative green innovations has been investigated, there are significant discrepancies in the findings of various studies, indicating the need for further clarification on how these practices influence the GAI. Furthermore, to the best of the author’s knowledge, there are no previous studies that have examined this linkage in the wine context, which represents a research opportunity to advance scientific understanding of the catalytic role of GHRM. Additionally, there is a scarcity of research delving into the intermediary and conditional factors that may affect the interplay between GIC and GAI [20], suggesting a significant opportunity for academic advancement in this field.

The current investigation seeks to bridge these knowledge gaps by scrutinizing the influence of GHRM on GAI, considering the potential mediating function of GIC and the possible moderating influence of Top Management Environmental Awareness (TMEA) within this dynamic. In fact, studies that analyze the role of the GIC as a mediator in the GHRM-GAI relationship are limited, being nonexistent for the case of how TMEA can moderate this dynamic, thus allowing the study to generate new knowledge around the GHRM field by offering a more comprehensive view of how GHRM practices impact on the companies' capacity for eco-innovation through GIC and TMEA. It is worth noting that such awareness can play a crucial role as a moderator in the relationship between GHRM and GAI due to its ability to influence the effectiveness of environmental management practices, as senior managers with a high environmental awareness are better able to integrate sustainability objectives into corporate strategy and ensure that the necessary natural resources are allocated appropriately [21]. In addition, this typology of awareness can also foster an organizational culture that promotes green innovation [22], which is essential to balance the exploration of new opportunities and the exploitation of existing practices, thus enhancing the positive effect of GHRM practices on GAI.

This research is structured around three pivotal Research Questions (RQs): (RQ1) What is the effect of GHRM on GAI? (RQ2) Can GIC be identified as a mediator in the GHRM-GAI equation? (RQ3) How does TMEA alter the GHRM-GAI dynamic? To address these questions, a detailed theoretical framework has been developed and is examined through the lens of structural equation modeling. The empirical data underpinning this study was garnered via a primary survey spanning from September 2022 to January 2023.

The present investigation holds significant implications for several reasons. First, it represents a pioneering effort, as no previous research has delved into the role of TMEA as a moderator in the relationship between GHRM and GAI, so this study breaks new ground by exploring this novel interaction. Second, by focusing on the wine industry, this research offers a new perspective on the GHRM-GAI relationship, as this relationship has not previously been examined in the specific context of the wine sector, thus shedding light on the dynamics of the GHRM-GAI relationship in a sector traditionally perceived as low knowledge-intensive. Third, this study makes a valuable academic contribution by advancing the understanding of the antecedent variables that influence GAI within the wine context. By shedding light on these antecedent variables, the research expands and enriches the existing knowledge base in this specific area of study. Fourth, the formulation of the theoretical model used in this study represents a novel contribution, given that it has not been previously contrasted. Fifth, the research makes a valuable contribution to the literature by bridging the gap between human resource management, environmental management and intellectual capital through investigating the interaction between these three distinct fields of study.

This study is organized to meet its research goals as described below. After this introduction, Sect. 2 details the theoretical framework that the study will empirically test. Section 3 describes the methodology used to carry out the research. Section 4 discusses the key results obtained from the analysis. The study concludes with Sect. 5, which offers a thorough critique of the results, states the principal conclusions, acknowledges the study's limitations, and proposes avenues for further research.

2 Theoretical underpinning: resource-based view and the ability, motivation, and opportunity theory

The present research is underpinned by a theoretical framework that integrates two prominent perspectives: the Resource-Based View (RBV) and the Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity (AMO) theory. The RBV paradigm explores how an organization's capacity to effectively utilize its valuable, rare, and difficult-to-replicate strategic resources contributes to the attainment of competitive advantage [23]. In this context, GHRM can be considered a deeply strategic capability that encompasses proactive measures aimed at identifying, nurturing, motivating and improving employees' green behavior, with GHRM thus playing a key role in stimulating the development of innovative practices, which can be classified as exploratory or exploitative [7].

On the one hand, when strategically integrated within the intricate social fabric of an organization, human capital often fulfills the criteria set forth by RBV, as it exhibits the potential to yield superior performance through the cultivation of green innovation [24]. Huma resources can be effectively leveraged to optimize the benefits derived from management strategies designed to promote sustainability and pursue environmentally friendly goals [25], thus valuing human resources goes beyond improving organizational performance and encompasses greater recognition by the general public and the surrounding environment, along with fostering green innovations [26]. On the other hand, on the alternative perspective, the influence of GHRM on GAI can also be comprehended within the framework of the Ability, Motivation, and Opportunity (AMO) theory. Following this theoretical lens, GHRM is assessed through the integration of three key components: green sourcing, green training and development, and green compensation [27]. GHRM contributes substantially to the GAI of companies by increasing the “Capacity” (A) of green employees through attracting/selecting and training high-performing staff, along with enhancing their skills, fostering the “Motivation” (M) of green workers by actively promoting their engagement through various green initiatives, and providing ample “Opportunities” (O) for employees to actively participate in environmental management efforts [28]. In this regard, the AMO theory serves as a theoretical framework that enables the GHRM-GIC-GAI sequence to be predicted. The subsequent section will expound upon the underlying rationale and detailed argumentation that underpins the formulation of hypotheses in the present study.

2.1 Green human resource management and green innovation ambidexterity

A multitude of research endeavors have investigated the catalysts of green innovation, identifying a variety of influencing elements including ecological consciousness [29], eco-centric purchasing tendencies [30], environmental advocacy [7], eco-efficient supply chain practices [31], the volatility of environmental factors [32], and the awareness of temporal factors [33]. In the context of recent studies examining the nexus between GHRM and green innovation, it is crucial to note the insights of Muisyo and Qin [34], who highlighted the spectrum of GHRM practices, including eco-friendly recruitment, training, development, performance evaluation, remuneration, and leadership, as instrumental in spurring green innovation.

Although the importance of GHRM and its potential implications for organizational performance is on the rise, the literature reveals a paucity of research exploring the relationship between GHRM and the organization's capability to cultivate both exploitative and exploratory green innovations, denoted as GAI. This gap in the research highlights the need for further investigations to comprehensively understand the interplay between GHRM practices and their influence on fostering GAI within organizations. Limited studies have explored this relationship, with only two notable attempts identified. In the context of the Spanish hotel sector, Úbeda-García et al. [19] conducted an empirical investigation, revealing that GAI plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between GHRM and environmental performance. Furthermore, Ahmad et al. [35] recently conducted a study focusing on manufacturing firms in Pakistan, highlighting the mediating effect of green competitive advantage in the link between GHRM and GAI. Nevertheless, despite these initial contributions, further research is warranted to gain a comprehensive understanding of the intricate interplay between GHRM and GAI, encompassing diverse organizational contexts and industries.

The literature review reveals several gaps in scientific research on the subject. First, no prior academic investigations have explored the link between GHRM and GAI within the wine industry. Therefore, conducting a study in this domain becomes imperative to advance scientific knowledge concerning the examined constructs. Second, the academic literature on the topic analyzed is very scarce, since most research has analyzed green innovation as a consequent variable of GHRM, leaving the study of GAI in the background. Third, previous studies on the subject have yielded mixed results on the relationship between GHRM and GAI, so further analysis of the relationships is needed to deepen the meaning of the relationship. Based on the RBV and AMO theoretical frameworks, it is envisioned that wineries that value and leverage the inherent potential of their human talent will systematically adopt GHRM practices, with this strategic implementation intended to attract and inspire a workforce that prioritizes environmental sustainability and provide them with conducive circumstances to leverage their capabilities in fostering the development of green innovations, encompassing both exploratory and operational efforts. Therefore, the ensuing hypothesis is postulated for examination:

-

H1. GHRM has a positive effect on GAI.

2.2 Green human resource management, green intellectual capital and green innovation ambidexterity

The examination of the relationship between GHRM and GAI encompasses a bidirectional analysis to comprehend their interconnectedness and reciprocal impact within the organizational realm [36]. On the one hand, various research analyzes how GAI can influence GHRM, given that organizations that cultivate a culture of experimentation and knowledge acquisition in the field of green innovation are more likely to be open to implementing GHRM policies and practices [37]. On the other hand, attention has also been focused on understanding how GHRM can foster and facilitate GAI within an organization, as GHRM involves the adoption of human resource practices and policies that foster employees' environmental awareness, commitment and competencies in sustainability, leading to companies being able to harness the creative and innovative capacity of their workforce to generate environmentally sustainable solutions [15]. The current research specifically emphasizes the latter causal relationship, accentuating the significant role of green practices in recruitment, training, and employee development as potent catalysts for fostering green organizational innovation.

An effective GHRM policy has the potential to foster environmentally conscious attitudes and behaviors among employees both within and outside the organization [38]. As a response to external environmental pressures, companies employ GHRM practices to cultivate a GIC that is capable of effectively addressing environmental concerns [39]. Moreover, the GHRM policy plays a crucial role in prioritizing sustainability within the realm of people management, thereby facilitating the attainment of organizational reputation, enhanced effectiveness, and the establishment of favorable working conditions for employees [40].

Organizations with a strong GSC have characteristics such as an advanced pro-environmental infrastructure, the use of contemporary environmental technologies and the adoption of strategic approaches [41]. These organizations are therefore more likely to excel in achieving GAI, whereby the application of GSC enables managers to effectively address environmental pollution by reconfiguring production processes and enhancing green productivity [20]. In addition, several previous have widely recognized that stakeholders' concerns and attitudes towards the natural environment exert a significant influence on companies' greening efforts, including eco-innovation, within an organization, so GRC can drive both exploratory and exploitative eco-innovation processes [42].

Yet, while there are scholarly precedents examining the interconnections among GHRM, GIC, and GAI, research in this triad is notably sparse and requires further maturation and contemplation, particularly within economic sectors that remain under-researched. To date, there appears to be a lacuna in scholarly inquiry into the sequential impact of GHRM-GIC-GAI within the viticulture sector, marking a novel area for academic exploration that promises to enhance our comprehension of the topic. This gap is especially pertinent given the potential influence of GHRM on the viticulture industry’s prosperity, not only in terms of ecological biodiversity but also in improving labor conditions and enological techniques, thereby fostering the development of a sustainable wine industry over the long term. To bridge these identified lacunae in the academic literature, the study posits the following three hypotheses for investigation:

-

H2. GHRM yields a favorable impact on GIC.

-

H3. GIC yields a favorable impact on GAI.

-

H4. GIC serves as a positive mediator between GHRM and GAI.

2.3 Green human resource management, top management environmental awareness and green innovation ambidexterity

In the field of environmental sustainability, top management assumes a critical role as a stakeholder influencing the implementation of environmental practices within an organization [39]. In this sense, to foster ecological excellence, top management should show an unwavering commitment to achieving success in environmental projects, thus engendering employee dedication [43]. This commitment is related to TMEA, which denotes the recognition and prioritization of environmental concerns by top executives based on their experience, playing a key role in driving the initiation and advancement of environmentally friendly innovation within organizations [44].

The RBV theory suggests that organizational resources are essential for achieving a competitive edge in sustainability [45]. Specifically, within environmental management, the commitment of top management is considered vital for the effective deployment of environmental management systems [46]. Additionally, a strong commitment from top executives to environmental management promotes a culture of sustainability within the organization and ensures the allocation of resources necessary for implementing GHRM practices.

TMEA can shape organizational culture towards sustainability, as when senior executives are environmentally conscious, they are more likely to support and invest in green practices, thereby enhancing GHRM's overall impact on green innovation [47]. This support manifests itself in a variety of ways, such as prioritizing the allocation of budgets for environmental initiatives, supporting green training programs and rewarding eco-friendly behaviors among employees [48]. In addition, TMEA fosters an environment where staff feel empowered to contribute to the organization’s sustainability goals, leading to a more cohesive workforce committed to environmental excellence [49].

Such senior management awareness can mitigate potential obstacles that often accompany the implementation of new green initiatives, as executives with a strong environmental focus are better equipped to deal with different environmental regulations, anticipate market changes and effectively address stakeholder concerns [50]. This proactive approach thus facilitates both a smoother implementation of green practices and a leading sustainability positioning in the market, attracting like-minded partners and customers [51]. Thus, TMEA can act as a catalyst that amplifies the effectiveness of GHRM by ensuring that environmental strategies are aligned with broader organizational objectives and supported at the highest levels [52].

Enhancing the environmental consciousness of top management at the strategic level holds significant potential for fostering an environmentally sustainable business environment and mitigating resistance to the implementation of green innovation initiatives, which are critical for the overall success of the green innovation strategy [53]. Several key aspects highlight the importance of heightened environmental awareness among top executives. First, it enables the identification of potential market opportunities within the business landscape, facilitating the efficient allocation of internal resources and capabilities towards green innovation endeavors and cultivating an environmentally friendly corporate culture [54]. Second, top managers with a strong environmental consciousness demonstrate foresight by anticipating the detrimental consequences of inappropriate environmental practices [55]. Third, an elevated level of environmental protection awareness among top management leads to a greater recognition of the benefits associated with environmental preservation, thus alleviating concerns regarding the significant resource investment required for green innovation practices [56].

Despite the acknowledged efficacy of TMEA in enhancing both GHRM and GAI, the current study identifies a research gap, as no prior investigations have examined its role as a potential enhancer of the GHRM-GAI relationship (see Fig. 1). Accordingly, drawing upon the conducted literature review and focusing on the specific sector under scrutiny, the following hypothesis is posited:

Graphical representation of proposed theoretical model. H1 = a1: Green human resource management → Green ambidexterity innovation. H2 = a2: Green human resource management → Green intellectual capital. H3 = b1: Green intellectual capital → Green ambidexterity innovation. H4 = a2 × b1: Green human resource management → Green intellectual capital → Green ambidexterity innovation. H5 = c1: Top management environmental awareness.

-

H5: TMEA positively moderates the relationship between GHRM and GAI.

3 Methodology

The present study adopts a methodological framework comprising four delineated sections: (1) research context, (2) population and sample, (3) variables, and (4) analysis technique. These subsections collectively aim to furnish a comprehensive overview of the research design and are elaborated upon in the subsequent sections.

3.1 Research context

The choice of the Spanish wine sector as a research context is supported by several significant justifications. First, the Spanish wine sector has played a substantial role in contributing to the country's economic growth, as evidenced by the addition of approximately €23.7 billion to the Gross Value Added (GVA) in 2022, which constitutes 2.2% of the national GVA [57]. Second, given the current social and environmental expectations of consumers and the imperative to adhere to stringent environmental standards, research into the prospects offered by green agricultural innovation can help the wine industry to meet these requirements, making it a relevant area of research [58]. Third, the Spanish wine sector has significant social, environmental and heritage value [59], so understanding the drivers of GAI is crucial to advance the environmental sustainability of the sector. Fourth, green innovations have emerged as a critical competitive factor in today's volatile wine industry environment, enabling wineries to differentiate themselves and reduce costs [60, 61]. Fifth, TMEA plays a key role in promoting the proactive adoption of sustainable practices in wineries [60].

3.2 Population and sample

The study centered on winemaking companies categorized under code 1102 in the Spanish National Code of Economic Activities (CNAE, by its Spanish acronym). The Iberian System of Balance Sheet Analysis (SABI, by its Spanish acronym) database served as the source to identify a total of 4373 businesses falling within this category. For data collection, a comprehensive questionnaire was devised, drawing insights from an extensive review of pertinent literature. To ensure the questionnaire's precision and validity, it underwent rigorous pre-testing involving environmental and quality managers of wineries, as well as winemakers, prior to its implementation in the study. The pretest was carried out at the premises of the University of Alicante on 7 December 2021 and involved a total of 7 winemakers and 8 environmental managers from 15 different wineries in the province of Alicante, using non-probability sampling by geographic convenience for the selection of participants. In particular, the three criteria followed for the selection of the sample were: (1) winemakers or environmental managers of the wineries, (2) more than 5 years of experience in the sector and (3) cellars belonging to the province of Alicante. Respondents completed the questionnaire and provided detailed feedback on ease/difficulty of understanding, ambiguities and confusing technical terms. This information was compiled to identify problem areas and, subsequently, modifications were made as necessary by rephrasing confusing questions, simplifying language and adjusting the format of the questionnaire. Ultimately, the revised version was validated with pretest participants, ensuring that the modifications adequately addressed the problems identified, which contributed to the validity and reliability of the final questionnaire. The online survey was conducted using the Qualtrics application from September 2022 to January 2023. To ensure the inclusion of knowledgeable and experienced respondents, a stringent screening process was implemented, resulting in a total of 196 valid responses from winery CEOs. The participation of CEOs was sought to capture ideas and perspectives regarding the overall strategic operations of their organizations, with the final sample consisting of 196 responses obtained from different winery CEOs.

3.3 Variables

To maintain methodological rigor, this research utilized scales that have been previously established for their robustness and accuracy in measuring the constructs of interest (see Appendix 1). The GHRM construct was quantified using the instrument formulated by Mousa and Othman [62], which is divided into three primary dimensions: green recruitment (6 indicators), green training and engagement (8 indicators), and green evaluation and reward systems (8 indicators). For the assessment of the GAI construct, this study adopted the multidimensional scale from Wang et al. [63], which is bifurcated into two dimensions: explorative green innovation (4 indicators) and exploitative green innovation (4 indicators). The GIC construct was gauged using the 7-item scale from Zaragoza-Sáez et al. [64], which respondents rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The TMEA construct was measured with an 8-item scale developed by Cao et al. [65]. Additionally, control variables were incorporated to discern their effect on GAI, including the winery's age, size, and affiliation with a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).

3.4 Analysis technique

In this investigation, the data was scrutinized using the partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) method, with the SmartPLS v. 4.0.0 software serving as the analytical tool. PLS-SEM is a robust statistical approach that is particularly adept at exploring complex interrelations among theoretical constructs, many of which represent latent variables not directly measurable [66]. The rationale for selecting PLS-SEM was threefold: (1) the intricate nature of the GHRM and GAI constructs required a sophisticated methodological tool capable of managing the intricacies of multivariate datasets [67]; (2) the model's need to elucidate both direct and mediated linkages among the constructs, for which PLS-SEM is particularly well-suited due to its ability to estimate multiple paths simultaneously [68]; and (3) the sample size of the research, which was well above the threshold of 100 participants, a number posited by Reinartz et al. [69] as the minimum for effectively applying PLS-SEM.

4 Results

This research employs a two-stage approach to address the complexities of GHRM and GAI constructs as posited by Hu and Bentler [70]. To address the multidimensional aspects of these constructs, latent variable scores were used as a crucial component of the model. In the initial phase, composite scores were computed and employed as indicators of the higher-order constructs, adhering to the methodological guidelines proposed by Hair et al. [68] to ensure validity. The ensuing results are presented in two distinct sections: (1) an assessment of the measurement model and (2) an evaluation of the structural model.

The evaluation process began with a preliminary check of the model's overall suitability. Findings indicate a robust model alignment, highlighted by an SRMSR score of 0.049, significantly under the accepted limit of 0.08 [61]. This implies that the model demonstrates an adequate fit as outlined in Table 1. Additionally, it is important to highlight that the metrics for unweighted least squares discrepancy and geodesic discrepancy are consistently within the established confidence intervals, notably below the upper 95% and 99% confidence levels, after employing bootstrapping techniques. These results robustly confirm the model's credibility and its effectiveness in capturing the intricate aspects of the studied constructs.

The measurement model was analyzed following the guidelines provided by Hair et al. [54], which encompassed evaluating indicator reliability, assessing internal consistency reliability, examining convergent validity, and exploring discriminant validity. First, as shown in Table 2, the reliability criterion at the individual item level was met by all indicators for the variables under investigation, with loadings exceeding the commonly cited threshold of 0.707 established in academic literature [71]. Moreover, through bootstrapping analysis, it was confirmed that all loadings were statistically significant, indicating satisfactory levels of individual reliability for the respective indicators. It is important to highlight that all individual items of the first-order constructs also surpassed this threshold (0.70) and, therefore, could be included in the final model, as shown in Appendix 2, without compromising the validity or reliability of the overall model. Second, regarding the analysis of internal consistency, it can be concluded that all the constructs met the criteria prescribed for this indicator, which is supported by obtaining values above 0.7 for Cronbach’s alpha and the Dijkstra-Henseler criterion (Pa). Third, regarding discriminant validity, Table 3 presents the results obtained from the Heterotrait-Monotrait criterion (HTMT). The observed values are notably lower than 0.85, indicating the distinctiveness of each construct and its ability to encompass various aspects within the proposed model, which reinforces the notion that the designated constructs capture real. Therefore, the relationships established do not overlap, but rather explore interdependencies between separate variables.

After establishing the reliability and validity of the constructs, the focus shifted to evaluating the effectiveness of the structural model. A preliminary step in this evaluation was checking for potential collinearity among the predictor variables of each endogenous construct, which is critical to preventing multicollinearity issues. Following the recommendations by Hair et al. [54], a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) above 5 signals possible collinearity concerns. In this case, all VIF values were below this threshold, confirming that collinearity was not a problem. The assessment of the measurement model then proceeded, focusing on its predictive abilities and the interrelationships between the constructs. This evaluation adhered to the methodology suggested by Hair et al. [68], involving an analysis of path coefficients and R-squared values. Results were derived from a bootstrap analysis with 5000 subsamples, providing robust insights into the model’s performance.

Table 4 reveals that GHRM positively influences the GAI of wineries, showing both direct and indirect significant effects. Specifically, the direct effect is quantified at 0.142 and the indirect at 0.143, combining for a total effect of 0.285 (p ≤ 0.001). Additionally, the impact of GHRM on GAI is notably affected by the level of total market environmental activities (TMEA), as indicated by a significant 95% confidence level for the TMEA interaction term. Consequently, all five hypotheses proposed in this study are supported. Regarding other variables, Fig. 2 shows that while membership in a PDO and age do not significantly impact GAI (β = 0.081, p < 0.082 for PDO; β = 0.031, p < 0.304 for age), the size of the winery positively correlates with GAI (β = 0.112, p < 0.033), indicating significant influence.

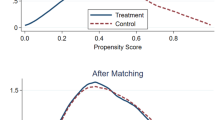

Moreover, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of TMEA's impact on the GHRM-GAI relationship, a simple slope analysis with an interaction effect is presented in Fig. 3. The graph illustrates the relationships between GHRM (X-axis) and GAI (Y-axis) through three lines. The middle line represents the relationship when the moderator variable, TMEA, is at its midpoint, indicating a moderate TMEA level. The other two lines represent the same relationship with high and low TMEA levels, respectively. Upon analysis, it becomes evident that as TMEA intensity increases, the association between GAI and GHRM strengthens significantly. Conversely, at lower TMEA levels, the relationship weakens, highlighting the influence of varying TMEA levels on the dynamics of the GHRM-GAI relationship.

Lastly, the model’s quality is assessed using the Gesisser test (Q2), with expected estimated values greater than 0 (Q2 > 0). Analysis of Table 5 reveals that the model exhibits moderate levels of substantive significance, as denoted by Q2 values exceeding 0.25 [66].

5 Discussion and conclusions

The outcomes of this study underscore the significant role of GHRM in fostering GAI within the Spanish wine sector. Moreover, the research reveals the mediating impact of GIC and the moderating influence of TMEA on this association. These findings offer valuable insights to wine industry professionals and academics, enhancing their comprehension of how a winery’s ecological knowledge stock fundamentally shapes its competitive positioning in the marketplace.

The findings of this study corroborate with contemporary scholarly work on the subject, such as the studies by Úbeda-García et al. [19] and Ahmad et al. [35], which have empirically substantiated the positive correlation between GHRM and GAI within the hospitality industry of Spain and the manufacturing sector of Pakistan, respectively. Nonetheless, there has been a gap in the literature regarding a combined examination of the mediating influence of GHRM and the moderating impact of TMEA on the nexus between GHRM and GAI. By integrating insights from the RBV and AMO theory, this research has empirically validated the beneficial roles of these effects, thereby enriching the academic comprehension of the determinants that can bolster both exploratory and exploitative green innovation.

The study, therefore, yields several theoretical and practical implications. In terms of theoretical implications, first, this study represents a pioneering effort in examining the moderating role of TMEA in the relationship between GHRM and GAI, as by integrating RBV and AMO theory, this research provides a novel theoretical lens for understanding these interactions. Second, the focus on the wine industry offers a unique perspective, as this sector has traditionally been overlooked in studies related to knowledge-intensive practices and eco-innovation. Therefore, this context-specific research allows both to show the dynamics of GHRM and GAI within the said industry, and to challenge the conventional perception of the sector, suggesting that it can indeed benefit from advanced environmental and innovation strategies. Third, this study contributes to the academic discourse by broadening the knowledge base on the antecedent variables influencing GAI in the wine sector, offering new insights into this model, previously untested in the existing academic literature, and laying the groundwork for future research. Fourth, the study allows to expand the frontiers of knowledge in the field of human resources management, environmental stewardship and innovation management within the wine sector. Fifth, the results fill several gaps in the academic literature in answering the three RQs posed: (RQ1) GHRM positively and significantly affects GAI; (RQ2) GIC partially mediates the relationship between GHRM and GAI; and (RQ3) TMEA positively moderates this primary link.

In terms of practical implications, the study highlights the importance for managers to adopt to promote GHRM practices in their wineries, as well as their environmental awareness. First of all, green sourcing by wine managers can enhance wineries’ GAI by fostering a corporate culture that values both the exploration of new sustainable practices and technologies and the effective exploitation of established initiatives. In this regard, by seeking out and selecting suppliers and partners that share green values, managers can introduce new ideas, processes and approaches that drive sustainability at all levels of the company. Adopting green practices in sourcing can also stimulate collaboration and knowledge sharing between wineries and their suppliers, which promotes continuous learning and adaptation, since by interacting with suppliers that focus their efforts on sustainability, wineries can acquire new skills and knowledge that drive green innovation within the organization. In addition, green sourcing can help wineries enhance their reputation and market position, giving them a competitive advantage and access to new markets, which may ultimately lead to a more proactive approach to adopting environmentally friendly practices and processes.

Offering sustainability training and green practices to employees by managers can lead to increased awareness and knowledge about the importance of sustainability, fostering a corporate culture oriented towards green innovation. Participation in green activities and programs, such as sustainability workshops, conferences and events, gives employees the opportunity to meet and connect with experts and leaders in the field, facilitating the exchange of ideas, best practices and inspiration for implementing innovative initiatives in the winery. Green training and involvement can also motivate employees and managers to take active roles in identifying environmental issues and generating creative and sustainable solutions, which can lead to the creation of an environment conducive to exploration and experimentation with new ideas and approaches to improve current practices. Moreover, by promoting green training and involvement, managers encourage the integration of sustainability at all levels of the organization, which can lead to greater agility and adaptability in responding to emerging environmental challenges and opportunities.

Green performance management and compensation by wine managers can enhance wineries' GAI, since by incorporating sustainability and environmental performance criteria into employee evaluation and compensation systems, managers incentivize all staff to actively participate in the pursuit and implementation of sustainable practices. In this sense, linking environmental performance and compensation can provide additional motivation for employees and managers to continually seek green solutions, as their contribution to the winery's sustainability is recognized and rewarded. Similarly, green performance management and compensation can drive collaboration and team brainstorming, as employees will work together to find sustainable solutions and achieve shared environmental goals, which can result in increased investment in research and development of green practices and innovative technologies.

Similarly, the study highlights the importance of TMEA in improving both GHRM and GAI of wineries, since being aware of environmental challenges and the importance of sustainability, they set a strategic vision that prioritizes improving the green knowledge stock of workers and developing green innovations in all winery operations. TMEA should be reflected in the corporate culture, promoting a sustainable mindset at all levels of the winery, thus encouraging employees to become more actively involved in the search for green solutions and the adoption of sustainable practices in their daily roles, ultimately driving GAI. Likewise, wine managers, being aware of environmental challenges, could encourage collaboration between different departments of the winery, since cooperation between areas such as production, winemaking, marketing and environmental management would allow better identification and exploitation of opportunities to improve sustainability and green innovation. Furthermore, top management, by being aware of environmental trends and regulations, could anticipate changes in the market and adapt proactively, enabling the winery to remain competitive and respond effectively to increasing demands for sustainable products and practices.

While this research has made significant strides, it is not without its constraints. For a more comprehensive understanding of the GHRM contributions to GAI, it is imperative to broaden the research canvas to include viticultural regions from the New World, such as the United States. Moreover, subsequent inquiries should delve into identifying optimal practices that vineyards can implement to refine their GHRM strategies, potentially through qualitative methodologies like benchmarking studies. Consequently, an emergent avenue for research is to undertake a mixed-methods approach. This would serve a dual purpose: firstly, to validate the theoretical model posited in this study against the backdrop of the Californian wine industry, and secondly, to execute comprehensive interviews with vintners from both Spain and the United States to unearth strategies that could bolster GHRM within the winery sector. Such an approach would not only facilitate a comparative analysis of the model within the Californian context but would also uncover actionable strategies to enhance the efficacy and impact of GHRM practices. Likewise, examining other industries significantly affected by environmental challenges, such as agriculture, tourism and energy, would provide a broader perspective on the versatility of GHRM practices, allowing these efforts to develop industry-specific recommendations and facilitating the implementation of effective GHRM strategies in different business contexts. Therefore, as a future line of research, it is proposed to contextualize the proposed model in three sectors other than wine so as to, on the one hand, establish sectoral similarities and differences and, on the other hand, offer customized recommendations for each industry.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gilal F, Ashraf Z, Gilal N, Gilal R, Channa N. Promoting environmental performance through green human resource management practices in higher education institutions: a moderated mediation model. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2019;26(6):1579–90.

Qiu L, Jie X, Wang Y, Zhao M. Green product innovation, green dynamic capability, and competitive advantage: evidence from Chinese manufacturing enterprises. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2020;27(1):146–65.

Awan U, Arnold M, Gölgeci I. Enhancing green product and process innovation: towards an integrative framework of knowledge acquisition and environmental investment. Bus Strategy Environ. 2021;30(2):1283–95.

Knight H, Megicks P, Agarwal S, Leenders M. Firm resources and the development of environmental sustainability among small and medium-sized enterprises: evidence from the Australian wine industry. Bus Strategy Environ. 2019;28(1):25–39.

Ouvrard S, Jasimuddin S, Spiga A. Does sustainability push to reshape business models? Evidence from the European wine industry. Sustainability. 2020;12(6):2561.

Pham N, Hoang H, Phan Q. Green human resource management: a comprehensive review and future research agenda. Int J Manpow. 2020;41(7):845–78.

Singh S, Del Giudice M, Chierici R, Graziano D. Green innovation and environmental performance: the role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technol Forecast Soc Ch. 2020;150:119762.

Amrutha V, Geetha S. A systematic review on green human resource management: implications for social sustainability. J Clean Prod. 2020;247:119131.

Choudhary P, Datta A. Bibliometric analysis and systematic review of green human resource management and hospitality employees’ green creativity. TQM J. 2024;36(2):546–71.

Liu Z, Guo Y, Zhang M, Ma G. Can green human resource management promote employee green advocacy? The mediating role of green passion and the moderating role of supervisory support for the environment. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2024;35(1):121–53.

Shah P, Singh Dubey R, Rai S, Renwick D, Misra S. Green human resource management: a comprehensive investigation using bibliometric analysis. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2024;31(1):31–53.

Haldorai K, Kim W, Garcia R. Top management green commitment and green intellectual capital as enablers of hotel environmental performance: the mediating role of green human resource management. Tour Manage. 2022;88:104431.

Hina K, Khalique M, Shaari J, Mansor S, Kashmeeri S, Yaacob M. Nexus between green intellectual capital and the sustainability business performance of manufacturing SMEs in Malaysia. J Intell Cap. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2022-0226.

Riaz A, Cepel M, Ferraris A, Ashfaq K, Rehman U. Nexus among green intellectual capital, green information systems, green management initiatives and sustainable performance: a mediated-moderated perspective. J Intell Cap. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-03-2023-0063.

Xi M, Fang W, Feng T, Liu Y. Configuring green intellectual capital to achieve ambidextrous environmental strategy: based on resource orchestration theory. J Intell Cap. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-07-2022-0154.

Chen Y, Gao L, Zhang Y. The impact of green organizational identity on green competitive advantage: the role of green ambidexterity innovation and organizational flexibility. Math Probl Eng. 2022;2022:1–19.

Baquero A. Linking green entrepreneurial orientation and ambidextrous green innovation to stimulate green performance: a moderated mediation approach. Bus Process Manag J. 2024;30(8):71–98.

Hafeez M, Yasin I, Zawawi D, Odilova S, Bataineh H. Unleashing the power of green innovations: the role of organizational ambidexterity and green culture in achieving corporate sustainability. Eur J Innov Manag. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-04-2023-0274.

Úbeda-García M, Marco-Lajara B, Zaragoza-Sáez P, Manresa-Marhuenda E, Poveda-Pareja E. Green ambidexterity and environmental performance: the role of green human resources. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag. 2022;29(1):32–45.

Ali M, Puah C, Ali A, Raza S, Ayob N. Green intellectual capital, green HRM and green social identity toward sustainable environment: a new integrated framework for Islamic banks. Int J Manpow. 2022;43(3):614–38.

Tang J, Liu A, Gu J, Liu H. Can CEO environmental awareness promote new product development performance? Empirical research on Chinese manufacturing firms. Bus Strategy Environ. 2024;33(2):985–1003.

Xie J, Abbass K, Li D. Advancing eco-excellence: integrating stakeholders’ pressures, environmental awareness, and ethics for green innovation and performance. J Environ Manag. 2024;352:120027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120027.

Wernerfelt B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strategy Manag J. 1984;5(2):171–80.

Yong J, Yusliza M, Ramayah T, ChiappettaJabbour C, Sehnem S, Mani V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus Strategy Environ. 2020;29(1):212–28.

Yong J, Yusliza M, Ramayah T, Fawehinmi O. Nexus between green intellectual capital and green human resource management. J Clean Prod. 2019;215:364–74.

Yusoff Y, Nejati M, Kee D, Amran A. Linking green human resource management practices to environmental performance in hotel industry. Glob Bus Rev. 2020;21(3):663–80.

Iftikar T, Hussain S, Malik M, Hyder S, Kaleem M, Saqib A. Green human resource management and pro-environmental behaviour nexus with the lens of AMO theory. Cogent Bus Manag. 2022;9(1):2124603.

Hooi L, Liu M, Lin J. Green human resource management and green organizational citizenship behavior: do green culture and green values matter? Int J Manpow. 2022;43(3):763–85.

Su X, Xu A, Lin W, Chen Y, Liu S, Xu W. Environmental leadership, green innovation practices, environmental knowledge learning, and firm performance. SAGE Open. 2020;10(2):2158244020922909.

Zameer H, Yasmeen H. Green innovation and environmental awareness driven green purchase intentions. Mark Intell Plan. 2022;40(5):624–38.

Seman N, Govindan K, Mardani A, Zakuan N, Saman M, Hooker R, Ozkul S. The mediating effect of green innovation on the relationship between green supply chain management and environmental performance. J Clean Prod. 2019;229:115–27.

Yu D, Tao S, Hanan A, Ong S, Latif B, Ali M. Fostering green innovation adoption through green dynamic capability: the moderating role of environmental dynamism and big data analytic capability. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):10336.

Wang J, Xue Y, Yang J. Boundary-spanning search and firms’ green innovation: the moderating role of resource orchestration capability. Bus Strategy Environ. 2020;29(2):361–74.

Muisyo P, Qin S. Enhancing the FIRM’S green performance through green HRM: the moderating role of green innovation culture. J Clean Prod. 2021;289:125720.

Ahmad J, Al Mamun A, Masukujjaman M, Makhbul Z, Ali M. Modeling the workplace pro-environmental behavior through green human resource management and organizational culture: evidence from an emerging economy. Heliyon. 2023;9(9):1–19.

Zhao F, Wang L, Chen Y, Hu W, Zhu H. Green human resource management and sustainable development performance: organizational ambidexterity and the role of responsible leadership. Asia Pac J Hum Resour. 2024;62(1): e12391.

Labella-Fernández A. Archetypes of green-growth strategies and the role of green human resource management in their implementation. Sustainability. 2021;13(2):836.

Shoaib M, Abbas Z, Yousaf M, Zámečník R, Ahmed J, Saqib S. The role of GHRM practices towards organizational commitment: a mediation analysis of green human capital. Cogent Bus Manag. 2021;8(1):1870798.

Yong J, Yusliza M, Ramayah T, Farooq K, Tanveer M. Accentuating the interconnection between green intellectual capital, green human resource management and sustainability. Benchmark Int J. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-11-2021-0641.

Malik S, Cao Y, Mughal Y, Kundi G, Mughal M, Ramayah T. Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability. 2020;12(8):3228.

Rehman S, Kraus S, Shah S, Khanin D, Mahto R. Analyzing the relationship between green innovation and environmental performance in large manufacturing firms. Technol Forecast Soc Ch. 2021;163:120481.

Shah S, Lai F, Shad M, Konečná Z, Goni F, Chofreh A, Klemeš J. The inclusion of intellectual capital into the green board committee to enhance firm performance. Sustainability. 2021;13(19):10849.

Zhang Y, Khan U, Lee S. Salik MThe influence of management innovation and technological innovation on organization performance: a mediating role of sustainability. Sustainability. 2019;11(2):495.

Dubey R, Gunasekaran A, Childe S, Papadopoulos T, Helo P. Supplier relationship management for circular economy: influence of external pressures and top management commitment. Manag Decis. 2019;57(4):767–90.

Makhloufi L, Laghouag A, Meirun T, Belaid F. Impact of green entrepreneurship orientation on environmental performance: the natural resource-based view and environmental policy perspective. Bus Strategy Environ. 2022;31(1):425–44.

Hamdoun M. The antecedents and outcomes of environmental management based on the resource-based view: a systematic literature review. Manag Environ Qual Int J. 2020;31(2):451–69.

Zihan W, Makhbul Z, Alam S. Green human resource management in practice: assessing the impact of readiness and corporate social responsibility on organizational change. Sustainability. 2024;16(3):1153.

Anin E, Etse D, Okyere G, Adanfo D. Driving green procurement in a developing country: the roles of corporate environmental ethics, environmental training, and top management commitment. Afr J Manag. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2024.2313963.

Hasan S, Waghule S, Hasan M. Linking environmental management accounting to environmental performance: the role of top management support and institutional pressures. Cogent Bus Manag. 2024;11(1):2296700.

Aftab J, Veneziani M. How does green human resource management contribute to saving the environment? Evidence of emerging market manufacturing firms. Bus Strategy Environ. 2024;33(2):529–45.

Aftab J, Abid N, Cucari N, Savastano M. Green human resource management and environmental performance: the role of green innovation and environmental strategy in a developing country. Bus Strategy Environ. 2023;32(4):1782–98.

Ali S, Hossain M, Islam K, Alam S. Weaving a greener future: the impact of green human resources management and green supply chain management on sustainable performance in Bangladesh’s textile industry. Clean Logist Supply Chain. 2024;10:100143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clscn.2024.100143.

El-Kassar A, Singh S. Green innovation and organizational performance: the influence of big data and the moderating role of management commitment and HR practices. Technol Forecast Soc Chang. 2019;144:483–98.

Yang Z, Lin Y. The effects of supply chain collaboration on green innovation performance: an interpretive structural modeling analysis. Sustain Prod Consum. 2020;23:1–10.

Wang H, Khan M, Anwar F, Shahzad F, Adu D, Murad M. Green innovation practices and its impacts on environmental and organizational performance. Front Psychol. 2021;11:553625.

Huang S, Chau K, Chien F, Shen H. The impact of startups’ dual learning on their green innovation capability: the effects of business executives’ environmental awareness and environmental regulations. Sustainability. 2020;12(16):6526.

Marco-Lajara B, Zaragoza-Sáez P, Martínez-Falcó J, Sánchez-García E. Does green intellectual capital affect green innovation performance? Evidence from the Spanish wine industry. Br Food J. 2023;125(4):1469–87.

Sánchez-García E, Martínez-Falcó J, Alcon-Vila A, Marco-Lajara B. Developing green innovations in the wine industry: an applied analysis. Foods. 2023;12(6):1157.

Marco-Lajara B, Zaragoza-Sáez P, Martínez-Falcó J, Ruiz-Fernández L. The effect of green intellectual capital on green performance in the Spanish wine industry: a structural equation modeling approach. Complexity. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6024077.

Martínez-Falcó J, Marco-Lajara B, Zaragoza-Sáez P, Sánchez-García E. The effect of knowledge management on sustainable performance: evidence from the Spanish wine industry. Knowl Manag Res Pract. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2023.2218045.

Martínez-Falcó J, Sánchez-García E, Marco-Lajara B, Visser G. Green ambidexterity innovation as the cornerstone of sustainable performance: evidence from the Spanish wine industry. J Clean Prod. 2024;452:142186.

Mousa S, Othman M. The impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance in healthcare organisations: a conceptual framework. J Clean Prod. 2020;243:118595.

Wang J, Xue Y, Sun X, Yang J. Green learning orientation, green knowledge acquisition and ambidextrous green innovation. J Clean Prod. 2020;250:119475.

Zaragoza-Sáez P, Claver-Cortés E, Marco-Lajara B, Úbeda-García M. Corporate social responsibility and strategic knowledge management as mediators between sustainable intangible capital and hotel performance. J Sustain Tour. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1811289.

Cao C, Tong X, Chen Y, Zhang Y. How top management’s environmental awareness affect corporate green competitive advantage: evidence from China. Kybernetes. 2022;51(3):1250–79.

Zeng N, Liu Y, Gong P, Hertogh M, König M. Do right PLS and do PLS right: a critical review of the application of PLS-SEM in construction management research. Front Eng Manag. 2021;8:356–69.

Hair J, Hult G, Ringle C, Sarstedt M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2016.

Hair J, Sarstedt M, Ringle C. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur J Mark. 2019;53(4):566–84.

Reinartz W, Haenlein M, Henseler J. An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. Int J Res Mark. 2009;26(4):332–44.

Hu L, Bentler P. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods. 1998;3(4):424.

Carmines E, Zeller R. Reliability and validity assessment. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications; 1979.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors declare that they contributed equally to each part of the manuscript. J.M.F; E.S.G; B.M.L; and P.Z.S: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, writing original, draft, writing review and editing.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All authors agree to publish the article in the journal Discover Sustainability.

Consent to participate

Informed consents have been obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

There has no competing interests for this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Composition of the constructs

Construct | Items | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

Control Variables (CV) | CV 1. Is the winery adhered to at least one Protected Designation of Origin | Martínez-Falcó et al. [61] | |

CV 2. When was the winery founded? | |||

CV 3. How many employees does the winery have? | |||

Green Intellectual Capital (GIC) | GIC 1. Our employees care about the environment | Zaragoza-Sáez et al. [64] | |

GIC 2. Our employees have the knowledge and skills to protect the environment | |||

GIC 3. Our employees cooperate in working groups to address environmental issues | |||

GIC 4. Our employees cooperate with our suppliers to protect the environment | |||

GIC 5. Our employees cooperate with our customers/distributors to protect the environment | |||

GIC 6. Our company implements innovations to protect the environment | |||

GIC 7. Our company invests in facilities to protect the environment | |||

Top Management Environmental Awareness (TMEA) | TMEA 1. Executives attach great importance to the negative influence of the natural environment | Cao et al. [65] | |

TMEA 2. Corporate executives are well aware of the impact of environmental regulations on their companies | |||

TMEA 3. Corporate executives are clear about the best environmental practices in their industry | |||

TMEA 4. Corporate executives attach great importance to environmental protection | |||

TMEA 5. Corporate executives know the benefits of environmental initiative | |||

TMEA 6. Corporate executives believe that the production of environmental protection products will increase sales revenue | |||

TMEA 7. Corporate executives believe that environmental protection measures will reduce costs | |||

TMEA 8. Corporate executives believe that environmental protection measures will improve production efficiency | |||

Green human resource management (GHRM) | Green Recruitment (GR) | GR 1. The organization prefers to recruit employees that have knowledge about environment | Mousa and Othman [62] |

GR 2. Applicants for jobs in the organization are subject to interviews to test their knowledge about environment | |||

GR 3. In addition to other criteria, employees are selected based on environmental standards | |||

GR 4. Job seekers are attracted by the environmental image and policies of the organization | |||

GR 5. The job description includes the job’s environmental aspects | |||

GR 6. The recruitment message includes organizations’ environmental values in job advertisement | |||

Green Training and Engagement (GTE) | GTE 1. Training programs about environment are provided to large-scale individuals in the organization | ||

GTE 2. In general, staff are satisfied with the organization’s green training | |||

GTE 3. Topics offered through green training are modern and suitable for the institution’s activities | |||

GTE 4. The organization provides formal environmental training programs for employees to increase their ability to promote them | |||

GTE 5. Environmental training is a priority and an important investment | |||

GTE 6. The need assessment for green training helps to familiarize employees with environmental practices | |||

GTE 7. Evaluation of green training and development helps to measure the employees’ level of green knowledge and awareness | |||

GTE 8. Environmental objectives contain green training and development aspects | |||

Green Evaluation and Reward System (GERS) | GERS 1. Specific environmental goals are adopted by every manager and employee in the organization | ||

GERS 2. When environmental programs are improved, employees are rewarded for their remarkable ideas | |||

GERS 3. Employees who have achieved or exceeded the objectives of the environmental institution are rewarded with non-cash equivalents or other cash prizes | |||

GERS 4. Section managers reward staff in their departments when they improve environmental programs | |||

GERS 5. Environmental performance is recognized in public | |||

GERS 6. One of the criteria employee performance assessment is the achievement of environmental objectives | |||

GERS 7. There are adequate assessments of staff performance after attending courses on environmental topics | |||

GERS 8. Employees are punished for non-compliance with environmental standards in the organization | |||

Green ambidexterity innovation (GAI) | Green Exploitative Innovation (GETI) | GETI 1. Our firm improves cur-ent green products, processes, and services | Wang et al. [63] |

GETI 2. Our firm adjusts current green products, processes, and services | |||

GETI 3. Our firm extends current green market | |||

GETI 4. Our firm strengthens current green technology | |||

Green Exploratory Innovation (GERI) | GERI 1. Our firm adopts new green products, processes, and services; our firm enters new green technology | ||

GERI 2. Our firm exploit new green products, processes, and services | |||

GERI 3. Our firm discovers new green market | |||

GERI 4. Our firm enters new green technology | |||

Appendix 2

Loadings of the constructs with the first order variables

GR | GTE | GERS | GERI | GETI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

GHRM 1 | 0.841 | ||||

GHRM 2 | 0.865 | ||||

GHRM 3 | 0.809 | ||||

GHRM 4 | 0.857 | ||||

GHRM 5 | 0.896 | ||||

GHRM 6 | 0.882 | ||||

GHRM 7 | 0.765 | ||||

GHRM 8 | 0.719 | ||||

GHRM 9 | 0.806 | ||||

GHRM 10 | 0.822 | ||||

GHRM 11 | 0.817 | ||||

GHRM 12 | 0.789 | ||||

GHRM 13 | 0.785 | ||||

GHRM 14 | 0.791 | ||||

GHRM 15 | 0.889 | ||||

GHRM 16 | 0.867 | ||||

GHRM 17 | 0.854 | ||||

GHRM 18 | 0.892 | ||||

GHRM 19 | 0.893 | ||||

GHRM 20 | 0.876 | ||||

GHRM 21 | 0.891 | ||||

GHRM 22 | 0.867 | ||||

GAI 1 | 0.805 | ||||

GAI 2 | 0.817 | ||||

GAI 3 | 0.806 | ||||

GAI 4 | 0.814 | ||||

GAI 5 | 0.852 | ||||

GAI 6 | 0.849 | ||||

GAI 7 | 0.891 | ||||

GAI 8 | 0.895 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martínez-Falcó, J., Sánchez-García, E., Marco-Lajara, B. et al. Green human resource management and green ambidexterity innovation in the wine industry: exploring the role of green intellectual capital and top management environmental awareness. Discov Sustain 5, 135 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00333-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00333-z