Abstract

Savings play a significant role in any country’s economic development. Notably, because farmers tend to have seasonal income from their farming activities, they also tend to be highly vulnerable to poor saving habbit than other occupations, such as those in formal jobs. However, farmers who save part of their income for subsequent production can purchase farm inputs in time as they wait for the onset of rain. Reportedly, there has been poor saving behavior among farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, this study aims to determine the factors responsible for farmers’ saving behavior. Descriptive and econometric (binary logistic model) analyses were employed to achieve the objectives of the study. The results indicate that the majority of farmers saved on a monthly and weekly basis. The results of the binary logistic regression model analysis showed that age, marital status, gender, experience, group membership, distance to the markets and markets, farm income, and farmers’ sub-counties of residence had a significant influence on farmers’ saving behavior. From the results, policy measures to increase the rate of savings include the employment of more extension personnel to reach as many farmers as possible. Government and extension agents should target female and less experienced farmers through adult-based education programs because they are vulnerable to poor saving behavior. Farmers should join farmer—based groups and cooperative societies, in which saving information is disseminated. The government, non-governmental organizations and financial institutions should offer financial literacy training on savings to smallholder farmers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the last few years, Sub-Saharan African agriculture has faced many shortcomings. The challenges associated with SSA have led to food insecurity, poor living standards, and poverty, among others [1]. To highlight some of these challenges, most smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa rely on rainfall for their crops [2,3,4]. This is because farmers do not have adequate finances to purchase resources for irrigating their crops. Moreover, there are inadequate water sources to support all farming activities. Thus, concentrating on rain is the only option available. Reportedly, rain is seasonal and unpredictable and requires proper farm planning [5, 6]. However, farm planning involves assembling all the required resources, such as farm inputs, land preparation, and planting, early enough as they wait for unpredictable rains. Strikingly, most farmers are caught off guard between allocating their finances to their needs and crop production because of financial constraints [7]. In addition, there have been reports of fall army worm attacks on crops, especially cereals, such as maize [8]. Farmers who are financially constrained report heavy losses owing to crop destruction. This is because they could not afford to purchase pesticides to reduce pest and disease infestation. Notably, the majority of agricultural land in SSA is infertile; hence, farmers require sufficient fertilizer to boost crop yields [9, 10]. However, farmers have reported low adoption of both organic and inorganic fertilizers, attributed to financial resource constraints.

It has been reported that these challenges can be reduced by saving for incoming production. Saving for incoming production is, therefore, one of the highly recommended solutions to farmers in SSA to increase their farm efficiency and productivity. When farmers save, they are assured of early planting, thereby harvesting the maximum achievable farm yield [11]. Saving not only helps farmers purchase farm inputs in time but also adopts agricultural technologies that boost farm productivity. However, despite the reported benefits of saving for production, existing studies have reported poor saving behavior among smallholder farmers in SSA. Lidi et al. [12] reported that 29% of smallholder farmers in Ethiopia did not save at all, thus making them highly vulnerable to delayed planting. Similarly, Aidoo-Mensah [11] reported poor saving behavior among rural farmers in Ghana, which also led to poor farm planning. This is consistent with the findings of [13], who observed moderate savings among SSA farmers. In a study conducted by [14], it is evident that the majority of smallholder farmers do not save money for continuous production. Nagawa et al. [15] noted that farming households in Uganda, a country that depends entirely on agriculture for both food production and economic development, fail to allocate their income to savings.

To increase the level of savings among farmers, relevant policies should be implemented by the governments of the SSA countries. However, such policies require empirical research to determine the current state of saving behavior among smallholder farmers. In Uganda, the drivers of savings have not been well documented. Similarly, there is a knowledge gap regarding the determinants of saving behavior among smallholder farmers, especially in Uganda, a country characterized by low farm productivity. Taking central Uganda as a case study due to its intensive investment in agriculture as well as being an underdeveloped country, and hence requiring policies [16], the study aims to fill the above research gap. Similarly, the study was motivated by inadequate literature on saving behavior among farmers in the Ugandan context. The main objective of this study is therefore to determine the factors affecting farmers’ saving behavior. This is supported by the research question: What are the determinants of saving behavior among smallholder farmers? With the above objective, the main contribution and novelty of the study is that it fills the research gap on saving behavior, as well as bridging the policy implications to increase savings among rural farmers.

2 Literature review

2.1 Literature gaps

Mazengiya et al. [17] conducted a study in Ethiopia to assess the determinants of saving participation among smallholder farmers. However, their study relied on a relatively small sample size of 157, which may not provide a true representation of the population. This may lead to unreliable results on the determinants of saving participation, calling for more empirical studies on the state of farmers’ saving. Similarly [12], study on the determinants of saving behaviour in Ethiopia omitted other significant predictors of saving such as farming experience, marital status and institutional factors such as access to credit, extension and group membership. This results into incomplete results on saving behaviour among the farmers. Nwibo and Mbam [18] studied the drivers of saving in Nigeria and reported that the main predictor variables of saving include age, gender, education, family size, experience and income. However, their study relied on a small sample size which may not provide accurate and reliable results.

While there are many studies on the determinants of farmers’ saving behaviour globally, there are limited studies on the state of farmers’ saving in East Africa, especially in Uganda. The determinants of saving behaviour in Uganda are not well documented yet saving play a significant role among the smallholder farmers. This study therefore fills the above research gap by assessing the determinants of saving behaviour among the farming households in Central Uganda, and provides policy recommendations on how to improve farmers’ saving in order to reduce poverty in Uganda.

2.2 Determinants of saving behaviour

Several studies have been conducted on the saving behavior of smallholder farmers. However, such studies tend to produce varied results based on the methodological approaches applied, as well as the location of the study. Mazengiya et al. [17] conducted a study in Ethiopia using a Binary Logit model to determine the factors affecting farmers’ saving behavior. They reported that distance to markets had a positive effect on farmers’ saving behavior. Strikingly, the results from the probit model of [12] reported contradictory results, showing that distance to the market has an inverse effect on farmers’ decision to save. This implies that the nearer the farmer is to the markets, the higher the probability of saving due to the availability of financial institutions in the markets.

Tukela [19] applied multiple regression analysis to assess the drivers of saving behavior in Southern Ethiopia. Family size has been reported to have a significantly positive influence on farmers’ saving behavior. This implies that as land acreage increases, farmers tend to save more money. However, a study by [17] in the same country reported that farmers with large portions of land had a 41% lower chance of saving. Based on the results from the two authors, there are conflicting results on how farm size influences farmers saving behavior, as one author reports a positive effect while another reports a negative effect of farm size on farmers’ saving behavior.

Other conflicting results on the determinants are evident in the studies conducted by [18] in Nigeria and [20] in Ethiopia. In Nigeria, the results from [18] using multiple regression analysis showed that as the age of farmers increases, their saving behavior declines. They further explained that younger farmers save more than their older counterparts do. In Ethiopia [20], report a positive but insignificant effect of age on farmers’ saving behavior. Their findings showed that older farmers had a 4.4% higher chance of saving, but the results were statistically insignificant. Again, the two authors presented varied results on the age effect of saving behavior.

Household size has been reported to have conflicting effects on farmers’ savings behavior. Household size is closely related to the dependency ratio. As the number of family members increases, the dependency ratio also increases, which may impact saving behavior. Bhat et al. [21] clearly indicate that, as the size of the family increases, their decision to save declines by 43%. However, the results of study conducted by [14] indicate that family size has a positive but statistically insignificant influence on farmers’ saving behavior. From these two results, there is no consensus on how family size influences saving behavior.

Education creates awareness about the benefits of saving among farmers. Thus, education may theoretically have a positive effect on saving behavior. However [22], reported that education has a negative effect on farmers’ saving behavior. This implies that educated farmers tend to have a lower probability of saving than uneducated farmers do. In a study conducted by [21], it was reported that education increased farmers’ savings decisions by 82%. Therefore, the education variable also poses no consensus on how it influences farmers saving behavior.

In African tradition, females are always left behind in terms of land rights, family decisions, and access to family privileges. This also reflects the difference in saving behavior between male and female farmers. As female farmers do not dictate the types of crops to be produced or the use of revenues from farming activities, they tend to have less income than their male counterparts. As such, male farmers would save more than female farmers. Notably, males are mostly family decision makers who are tasked with ensuring that the family saves enough money for continuous production. Tesfamariam [23] report a 17% higher chance of saving among male farmers than among female farmers. However [24], present conflicting results on how gender influences saving behavior. Specifically [24], reported no significant difference in saving between males and females, implying that gender does not affect saving behavior.

Theoretically, it is hypothesized that farmers with many years of experience have vast knowledge about the benefits of saving to their households. Such farmers have also created and benefited from social-saving platforms. Therefore, experience is expected to be a positive determinant of savings. Obayelu [25] revealed that farming experience negatively affects farmers’ saving behavior. Their results imply that, as the years of experience increase, farmers tend to leave behind in terms of saving. However [26], reported that farming experience increased farmers’ decisions to save. From these two studies, farming experience is viewed as having a positive and negative effect on farmers’ saving behavior.

The varied results on the determinants of saving behavior have called for more empirical region-based studies. For instance [17], argued that the effects of socioeconomic, institutional, and demographic factors on saving behavior vary across regions, calling for regional studies on the determinants of saving behavior. In Uganda, studies on the determinants of saving behavior are scarce. This study aims to assess the determinants of farmers’ saving behavior using primary data collected in Uganda.

2.3 Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework presented in Fig. 1 is based on the research objective (determinants of saving behavior). The framework shows that the determinants of saving behavior among farmers can be categorized into three major categories. These include farmers’, farm, and institutional factors [27]. Regarding farm factors, the study considered farm location, market distance, income, output, and size. Institutional factors considered include access to extension, credit, membership in farmer groups, market information, and access to financial literacy programs. Based on a literature review, these variables have the potential to increase the level of savings among farmers (see Table 1). Finally, the farmers’ factors included farming experience, education level, marital status, gender, family size, and sub-county of residence. These three categories of determinants have the potential to either increase or reduce the level of savings among farmers [17, 18, 28, 29]. There are three major saving platforms that can be utilized by farmers. These include formal (commercial banks, microfinance institutions) [17], informal (home saving, asset saving, livestock saving) [12] and semi-formal (Village Saving and Loans Association, Table Banking, farmer groups) [13]. A rational smallholder farmer chooses to save if he/she perceives saving as important to his/her household. Once a farmer decides to save, he then chooses a suitable saving platform based on his location, cost, and preferences [15, 30]. Thus, the saving behavior takes a binary form.

2.4 Theories of saving behavior

Several theories on saving exist in the literature. These include the Keynesian Absolute Income Hypothesis, Friedman’s Permanent Income Hypothesis, and Modigliani Life Cycle Hypothesis. The Keynesian Absolute Income Hypothesis describes how consumers apportion their income to savings as well as consumption [31]. It is based on the level of income that consumers can save, since consumption is given the first priority over saving. Savings also increase as income increases [32]. However, Keynesian Absolute Income theory only works for shorter time periods; hence, it is not effective. Developed by [33], Permanent Income theory distinguishes between transitory and permanent income in terms of how savings are determined. When considering the current value of wealth, permanent income is defined as the expected long-term income during a planning period and a constant rate of consumption is maintained throughout life. Since it is anticipated that people would not spend money outside their income category, the marginal propensity to save on transitory income will be unity. Transitory income is the gap between actual and permanent income. Finally, introduced by [34], the Modigliani Life Cycle Hypothesis is more relevant to smallholder farmers. Just like farmers’ income behavior, which tends to be unpredictable and seasonal, the theory indicates that saving is only possible when income is high. Most farmers tend to have unpredictable income patterns because they depend on farming activities. Farming activities are highly vulnerable to climate change, pests, diseases, and drought among others [35, 36]. As such, their saving behavior does not follow a straight line but rather depends on the season when the income is high. As such, the Modigliani Life Cycle Hypothesis provides a true picture to farmers' saving habbit.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Study area

The study was conducted in Masaka district (Fig. 2). The district is located in central Uganda [37]. Its coordinates are 00 30 S, 31 45 E, and it lies at an average altitude of 1,115 m (3,658 ft) above sea level, covering an area of 1,295.6 Km2. The district has 9 sub-counties, 37 parishes, and 436 villages [38]. The Buwunga, Kyesiiga, and Kyanamukaka sub-counties were selected for this study, as shown in Fig. 2. Agriculture is the main economic activity for the majority of the Masaka population [39]. The major cash crops produced include coffee and cotton, whereas the major food crops include bananas, pineapples, maize, potatoes, cassava, tomatoes, and onions [39]. Most farmers in Masaka depend on the rain for their crops. The rainfall pattern in this region is bimodal, with two seasons. On average, Masaka recorded 244 annual rainy days. July and August are always dry in this region, while heavy rainfall is evident in March, April, and May. Farmers produce food and cash crops during these months. In terms of topography, the district is composed of hills and ridges at an altitude of 1150 m above sea level. Despite the favorable climate in Masaka, the majority of the population still experiences food insecurity. This is attributed to the dense population of this region [40]. Thus, conducting a study on how to improve agricultural productivity through the timely purchase of farm inputs, adoption of modern agricultural technologies, and access to both input and output markets as a result of saving is highly desirable in this region. Thus, it was one of the best regions for studies on the determinants of farmers’ saving behavior. Moreover, existing studies have shown that the income earned from farming and non-farming activities in Masaka is adequate to support both consumption and savings [41]. In addition, there are many financial institutions in Masaka, such as the Bank of Uganda, Centenary Bank, Letshego, and Post Bank, where farmers can save their income. However, poor saving behavior is still evident in this region [41].

3.2 Sampling and sample size

This study adopted random and convenient sampling procedures to collect data from the farmers. Farmers present during the data collection were randomly selected to participate in the study to avoid participation bias [42]. Convenience sampling method has been proven as one of the sampling methods used to reduce the non-response rate among the farmers. In this study, all the farmers present were considered for the study to reduce the non-response rate. Convenience sampling has been widely applied in agricultural research, for example [43], applied it in their study on adoption of agricultural technologies; [44] used convenience sampling in their study on mobile phones usage while [45] used it to collect data among the farmers in Sri Lanka. As shown in Fig. 2, we considered three sub-counties for the data collection. These include the Kyesiiga, Kyanamukaka, and Buwunga sub-counties. These were selected because they have many food and cash crop farmers [39]. It was also advantageous to select the three sub-counties because they border each other, making it easier to collect the data. The study adopted simple random sampling to select farmers, starting from Kyesiiga sub-county, followed by Kyanamukaka, and ended with data collection in Buwunga sub-counties. Priority was given to the number of farmers obtained from the list provided by sub-county agricultural officers. This study sampled 396 farmers, based on the sample size formula developed by [46].

\(n\) = sampled farmers, \(P\) = Population proportion of farmers in Masaka district (0.48) [38], Z = Z scores from the tables, \(e\) = error term. Piloting was performed on 13 farmers, which were then added to 383 farmers to make a total sample size of 396 for the study.

3.3 Research design

The study adopted a cross-sectional research design to collect data from the farmers. A cross-sectional research design involves data collection at a given point in time. It was relevant to this study since it gives reliable results which can be used by policy makers to implement relevant policies in a given area under consideration.

3.4 Data collection methods and instruments

Prior to data collection, we sought ethical clearance from Makerere University, Department of Agribusiness and Natural Resource Economics Research Ethics Committee to collect data from the farmers. The Department verbally cleared us to collect data from the farmers. There was no well-structured ethical committee at the time of the study and thus, the study was cleared by the Department of Agribusiness and Natural Resource Economics. The data collection tool was developed based on the aim of the study, pretested (piloted), and verified as valid and reliable for collecting data on farmers’ saving behavior. The results from the pretest were included in the analysis. The tool was designed to not only answer the research questions but also provide additional information on farmers’ saving behavior. Prior to data collection, enumerators were hired and trained to deeply understand the tool to avoid errors in the data. The farmers were briefed on the objectives of the study and how they would benefit from it. They verbally consented to participate in the study. Verbal consent was appropriate due to the fact that majority of the farmers in the study area were illiterate, with difficulties in reading and writing. We then collected primary data using a data collection tool. Face to face interviews between the enumerators and the farmers was adopted for data collection. The enumerators asked the questions and recorded farmers’ responses accordingly. Ethical considerations, such as consent seeking, privacy, and confidentiality, were followed during data collection. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected through face to face interviews with enumerators and farmers. During data collection, we encountered cases in which some farmers were unable to read or write properly. In such cases, enumerators asked questions in their local languages and recorded their responses correctly. Data collection took 3 weeks (from 2nd to 21st April, 2023).

3.5 Econometric analysis

3.5.1 Binary logistic model

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the socio-demographic characteristics of the farmers. T-test and Chi-square test were then used to determine if there were socio-demographic difference between farmers who save and their counterparts who did not save their income. The results are presented in Figures and Tables. In line with the literature and the nature of the dependent variable, this study considers two major methods to determine the factors affecting farmers’ decisions to save their income. These were Binary Logistic and Probit regression models, respectively. These two econometric techniques can explain the relationship between a binary dependent variable and hypothesized independent variables [47, 48]. A farmer can either save or fail to save; hence, it is a binary (also known as dichotomous) outcome. Saving behavior was measured by a dichotomous response, where a farmer saves. The binary logit and probit models are similar in many ways, and provide similar results. However, Binary logit was preferred in this study because it is computationally easier to use [49]. Binary logit has been widely used in agriculture for binary independent variables in studies by [47, 50,51,52,53,54]. The probability of saving is represented in Eq. 1, whereas the probability of not saving is represented by Eq. 2 [55]. The two Equations are combined to form Eq. 3, which is a simple binary logistic equation [56]. Equation 2 was then differentiated with respect to \({X}_{k}\) to obtain the marginal effects of the binary logit, as shown in Eq. 4.

where \(Pi\) is the probability of saving, \(1-Pi\) is the probability of not saving, \(\beta\) is the coefficient to be estimated, and \({e}_{i}\) is the error term. \({X}_{i}\) represents the explanatory variable in Table 1.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Socio – demographic characteristics of the farmers

While many studies have determined the socio-demographic characteristics of farmers in Uganda, there is still a need to analyze farmers’ demographic characteristics, since there are many changes in government policies and climatic and cultural changes that keep changing farmers’ socio-demographic characteristics. The farmers’ sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 2 (savers and non-savers). The table shows that savers were slightly younger than non-savers. However, this difference was not statistically significant. At the 10% level of significance, farmers who saved their income were more educated than their counterparts who did not save. Although the difference was statistically insignificant, the results showed that savers were more experienced in farming than their non-savers counterparts. The distance between farmers’ homes and trading centers was approximately 5.4 km. The results further depicted that the average farm size was 5.5 acres of land, from which farmers allocated their cropping enterprises. There were no significant differences in distance or farm size between savers and non-savers.

Based on the categorical socio-demographics, the results showed that there was a significant (P < 0.01) difference between farmers who saved and their counterparts in terms of access to credit. 80% of the farmers who saved had access to credit, whereas only 23% of the farmers who did not save had access to credit. A similar pattern was observed for access to extensions, market information, and group membership. Most farmers had access to roads. However, 91% of the farmers who had saved had access to roads, while only 81% of the farmers who had never saved had access to roads. This implies that infrastructure such as roads plays a significant role in saving. The results further showed that there was a significant difference in internet access among the farmers who saved and their counterparts who did not save their income (P < 0.10). 24% of the farmers who save their income had access to internet while only 12% of the farmers who did not save their income had access to internet services.

4.2 Saving frequency

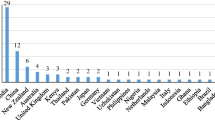

Figure 3 presents the frequency of farmer savings based on four major frequencies: daily, weekly, monthly, and quarterly saving frequencies. The majority of the farmers saved monthly, which was attributed to the fact that, apart from farming, farmers engage in other non-farm income earning activities such as formal jobs and businesses where they earned a monthly salary, this led to increase in their monthly saving, for example a farmer who is also employed as a teacher would save form both their farming income as well as the income from their teaching job, leading to higher frequency of monthly saving than daily, weekly, and quarterly. Weekly savings were achieved by 38% of the farmers. This mainly comes from their farm businesses, such as selling cereals and vegetables. Since there are weekly market days, farmers would save weekly from their weekly sales from the markets. Daily and quarterly savings were 23% and 14%, respectively (Fig. 3).However, studies have reported that farmers save mostly when their income is high, leading to seasonal saving behaviour, for example, [11] noted that the majority of farmers save seasonally in Ghana save. This is because their sources of income are unpredictable; thus, they save only when they have an excess income.

4.3 Determinants of saving behaviour

4.3.1 Binary logistic model summary

It is important to discuss the summary of the model fitness for any analytical method prior to explaining the signs and coefficients of the independent variables. In this study, binary logistic regression was used to explain the relationship between the hypothesized independent variables and farmers’ saving behavior. The results (Table 3) on model fit indicate that the P – value of the model was highly significant at 1%, hence meeting the minimum threshold for presenting the results. We also considered pseudo R-squared values. Normally, a pseudo R-squared value ranging from 20 to 40% falls under the extremely good category [62, 63]. The log-likelihood value was −117.459, which is acceptable. Based on these results, we were convinced that the model was adequate to present the results.

The study hypothesized a negative association between savings and the age of farmers. This was confirmed by the results, as older farmers had a 3% significantly lower chance of saving, based on the results from the margin effects (Table 3). This is as a result of them being less active in saving because of their old age. As farmers age, they tend to be less active in farming. This, in the long run, reduces their income and, hence, has a negative effect on saving. Similarly, older farmers are unable to attend financial literacy programmes that encourage savings. Age had a negative influence on savings among farmers, implying that increase in age reduces saving among the farmers This was observed in a study by [64], who observed a declining saving level among aged farmers, attributed to being less active in the economic activities, leading to less income for saving. Similarly [57], reported that older people have low-income sources, resulting in less savings than their younger counterparts who are actively engaged in economic activities. In contrast [12], reported a positive effect of age on savings among farmers in Ethiopia. They argued that older farmers have invested in many income earning activities, leading to increased income which can be used for saving.

Married farmers tend to share developmental ideas as families, which may include savings. They are also more concerned with their family economic status, such as food security, education, and family welfare. To achieve such goals, they tend to save more than unmarried people do. This study hypothesized that marital status would have a positive effect on saving behavior. This is confirmed by the results, which show a positive and significant influence of marital status on savings among farmers. Married farmers had 8.3% significantly higher probability of saving than their unmarried counterparts, implying that marital status increases farmers’ saving. In a study conducted by [28], married farmers saved more money than unmarried farmers did. These results are also in line with the findings reported by [58] in Washington, which aimed at assessing saving behaviour among the married and unmarried farmers. They reported higher savings among married than unmarried farmers, attributed to the responsibilities which are associated with marriage such as food purchase, among others.

The results further showed that gender significantly influenced farmers’ decisions to save. Sex was categorized into males and females, and the study considered males as binary variables. The results show that male farmers had a 4.2% significantly higher probability of saving than their female counterparts did. This can be explained by the fact that males are decision-makers in their families; they oversee the family’s progress, which involves saving. In African tradition, females are always left behind in terms of land rights, family decisions, and access to family privileges. This also reflects the difference in saving behavior between male and female farmers. As female farmers do not dictate the types of crops to be produced or the use of revenues from farming activities, they tend to have less income than their male counterparts. As such, male farmers would save more than female farmers. Notably, males are mostly family decision makers who are tasked with ensuring that the family saves enough money for continuous production. The findings of this study agree with the results reported by [23], who reported a 17% higher chance of saving among male farmers than among female farmers. However [24], reported no significant difference in saving between males and females, implying that gender does not affect saving behavior. In this study, we concluded that gender (male) increases saving among the farmers.

Farming experience is a significant determinant of farm productivity. Farmers who have stayed in farming for a long time make better decisions than younger farmers do. This is also reflected in savings. As presented in Table 3, farmers with more years of farming had a 5% higher probability of saving than their counterparts with fewer years of farming. This is because they are aware of the benefits of saving and how their can use their savings to boost their farm productivity, especially during the planting seasons. Farmers who have wealth of experience in farming are able t optimally balance and allocate their income to savings, household needs and other responsibilities, leading to higher saving amongst them. This result is consistent with the findings of [65]. He noted that farmers with more than 10 years of farming experience had higher savings rates than their fellows with no experience in Nigeria, attributed to proper decision making and income allocation among the experienced farmers. Wieliczko et al. [13] also reported increased savings among experienced farmers than among their inexperienced counterparts. They attributed this to the fact that experienced farmers are aware of the better saving institutions available to them. The study therefore concluded that farming experience increases farmers saving.

As argued by [34] in his Modigliani Life Cycle Hypothesis, which explains that consumers tend to save when their income is high, farm income positively influences farmers’ decisions to save based on the results in this study. An increase in income by a unit, would result into a 20.3% significantly (P < 0.01) higher probability of saving among the smallholder farmers. As income increases, farmers tend to save income after apportioning income to consumption. Shin and Kim [30] also reported that savings are highly influenced by farmers’ income levels. Moreover, the findings from a study conducted by [12] revealed that farmers with higher incomes had significantly higher rates of saving than their counterparts with little income in Ethiopia. This suggests that income is a positive dominant factor in saving among farmers. Olowoyeye et al. [66] also reported a positive and significant effect of income on smallholder farmers’ savings rates in Nigeria. Their results showed that a unit increase in income would increase the savings rate by 78%. Thus, income increases savings among the farmers.

The results further show that group membership increases farmers’ decisions to save. Farmer groups and associations have emerged as training platforms for farmers to share their development ideas. This involves how to save effectively and the various savings platforms available to them. In the long run, farmers who join such groups are far better than non-group members in terms of savings. From the groups, farmers can come together to save their income while also registering their associations in financial institutions. This not only increases their saving but also the ability to access financial services such as loans. This is consistent with the findings of [59, 67,68,69]. From the results presented in their studies, it is shown that group membership increases farm productivity, which in the long run increases farm income. With increased farm income, smallholder farmers can meet their consumption needs and savings. As such, joining farmer-based groups and associations helps increase the rate of saving among farmers.

It was expected that farmers located near trading centers would have a higher probability of saving than their counterparts located far away. This is because these trading centers have formal and informal saving platforms where farmers can easily save part of their income. Contrary to this hypothesis, the results showed that farmers located far away from trading centers had a significantly higher probability of saving than their counterparts. Our findings contradict those reported by [70], who explained that shorter market distance reduces transportation costs, which, in the long run, encourages farmers to save. Brei and peter [71] also pointed out the role of distance in accessing banking services, such as saving, noting that longer distances discourage farmers from saving due to the increase in transportation costs. However [72], reported a positive and insignificant effect of distance from financial institutions on farmers’ saving behavior in Ethiopia. This study therefore concluded that distance to markets reduces farmers’ saving.

4.4 Limitation of the study

The study aimed at assessing the determinants of saving behaviour among the farmers in Uganda. However, the study did not determine the extent or amount of saving by the farmers, yet the two are highly important for policy makers. Thus, the main limitation arising from this is study is failure to determine the extent or amount of saving by the farmers. The study was done in a small area, yet there are other districts with which needs policies on farmers saving behaviour. As such, the second limitation of the study is the small geographic coverage of the study.

4.5 Areas for further research

There is need for further studies on the same topic but in other districts in Uganda such as Gulu, Lira, Nwoya, Oyam, among others. There is also need for a study to determine the extent of saving by applying a double hurdle model. This will result into a robust results on farmers’ saving behaviour.

5 Conclusion and policy implications

This study aims to assess the determinants of farmers’ saving behavior. This study was motivated by varied results on the determinants of farmers’ saving behavior across regions, calling for region-based studies. Similarly, farmers tend to exhibit poor saving behavior, which makes them highly vulnerable to poverty and food insecurity. They are not able to prepare their lands, purchase farm inputs on time, or continue with their normal production. Based on the results of this study, most farmers were saved on a monthly basis. The study concluded that the main factors affecting savings among farmers include marital status, gender, farm income, age, farming experience, group membership, distance to markets, and farm location.

Based on these results, government and extension workers should target older, less experienced, and female farmers and enlighten them on the benefits of savings and available saving platforms. Farmers' efficiency levels can be increased by improving their educational status through the adult-based education programs offered by the government. Policy interventions should concentrate on boosting the availability and accessibility of markets and financial institutions in rural areas to encourage rural households to save, as distance to markets and financial institutions had a statistically significant impact on rural households’ savings decisions and amount of savings. Farmers should also be encouraged to join and attend groups and associations, including cooperative societies. The groups are meeting points where information on farmer—based development, such as saving, is shared. Similarly, revolving funds are a more effective and efficient way to mobilize rural savings, and can be used to provide collateral and guarantor-based loans with low default rates. Therefore, it is important to support economically feasible cooperative societies among the rural households in this region. As a result, they will be able to increase their savings and production output, which will stimulate the rural economy. In addition, the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and financial institutions should offer financial literacy training targeting savings among smallholder farmers. Thus, farmers' attitudes about saving will improve if this information is disseminated, leading to greater savings and a reduction in poverty.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [Dick Chune Midamba, midambadick@gmail.com] upon reasonable request.

References

World Bank. Climate-smart Agriculture in developing countries. Clim Agric Kenya. 2015; 1–16. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2019-06/CSAKENYANOV182015.pdf.

Ghimire R, Huang WC, Shrestha RB. Factors affecting adoption of improved rice varieties among rural farm households in Central Nepal. Rice Sci. 2015;22(1):35–43.

IFAD. Rainfed Food Crops in West and Central Africa. 2013; (July):186. file:///C:/Users/USER/Downloads/06-VA-A-Savoir.pdf.

Van Ittersum MK, Cassman KG, Grassini P, Wolf J, Tittonell P, Hochman Z. Yield gap analysis with local to global relevance-a review. F Crop Res. 2013;143:4–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2012.09.009.

Ndip FE, Molua EL, Shu G, Mbiafeu MF. Farm planning for short-term optimal food crop combination in the Southwest Region of Cameroon. J Food Secur. 2019;7(3):72–9.

Atukunda G, Atekyereza P, Walakira J, State AE. Increasing farmers’ access to aquaculture extension services: lessons from Central and Northern Uganda. Uganda J Agric Sci. 2022;20(2):49–68.

Dong F, Lu J, Featherstone AM. Effects of credit constraints on productivity and rural household income in China. CARD Work Pap 10-WP 516. 2010; (October). https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/.

Murray K, Jepson P, Huesing J. Fall armyworm for maize smallholders in Kenya : an integrated pest management. CYMMIYT. 2019; (November 2019). https://repository.cimmyt.org/bitstream/handle/10883/21259/63345.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Acheampong EO, Sayer J, Macgregor CJ, Sloan S. Factors influencing the adoption of agricultural practices in Ghana’s forest-fringe communities. Land. 2021;10(3):10–31.

Arora NK. Impact of climate change on agriculture production and its sustainable solutions. Environ Sustain. 2019;2(2):95–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-019-00078-w.

Aidoo-Mensah D. Determinants of savings frequency among tomato farmers in Ghana. Cogent Econ Financ. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2196862.

Lidi BY, Bedemo A, Melikamu B. Determinants of saving behavior of farm households in Rural Ethiopia: the double hurdle approach. Dev Ctry Stud. 2017;7(12):17–26.

Wieliczko B, Kurdyś-Kujawska A, Sompolska-Rzechuła A. Savings of small farms: their magnitude, determinants and role in sustainable development example of poland. Agric. 2020;10(11):1–18.

Obalola TO, Audu RO, Danilola ST. Determinants of savings among smallholder farmers in Sokoto South Local Government Area, Sokoto State, Nigeria. Acta Agric Slov. 2018;111(2):341–7.

Nagawa V, Wasswa F, Bbaale E. Determinants of gross domestic savings in Uganda: an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach to cointegration. J Econ Struct. 2020;9(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40008-020-00209-1.

MAAIF. The Republic of Uganda Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries Uganda Climate Smart Agricultural Transformation (UCSAT) Project-P173296 Process Framework-PF. 2022; (May).

Mazengiya MN, Seraw G, Melesse B, Belete T. Determinants of rural household saving participation: a case study of Libokemkem District, North-west Ethiopia. Cogent Econ Financ. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2127219.

Nwibo SU, Mbam BN. Determinants of savings and investment capacities of farming households in Udi local government area of Enugu State. Res J Financ Account. 2013;4(15):59–69.

Tukela B. Determinants of savings behavior among rural households in case of Boricha Woreda, Sidama Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Res Agric Appl Econ. 2016. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/.

Deksisa K, Bayissa M. Determinants of rural household savings behavior: the case of Ambo District, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. Sci Pap Ser Manag Econ Eng Agric Rural Dev. 2020;20(3):2020.

Bhat MA, Gomero GD, Khan ST. Antecedents of savings behaviour among rural households: a holistic approach. FIIB Bus Rev. 2024;13(1):56–71.

Tesfamariam SK. Saving behaviour and determinants of saving mobilization by rural financial co-operators in Tigrai Region, Ethiopia. J Agribus Rural Dev. 2012;4(26):129–46.

Asfaw DM, Belete AA, Nigatu AG, Habtie GM. Status and determinants of saving behavior and intensity in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities of Afar regional state, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2023;18:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281629.

Sereetrakul W, Wongveeravuti S, Likitapiwat T. Gender differences in saving and spending behaviours of Thai students. Res Educ. 2013;90(1):68–81.

Obayelu OA. Saving behavior of rural households in Kwara State, Nigeria. SSRN Electron J. 2012;4(4):115–23.

Akpoviri R, Campus A. Farmers ’ attitude and behavior toward saving In Ika South local government area of Delta State, Nigeria. Asian J Agric Rural Dev. 2020;10(1):406–19.

Nwibo SU, Mbam BN. Determinants of savings and investment capacities of farming households in Udi local government area of Enugu State, Nigeria. Res J Financ Account. 2013;4(13):59–69.

Love DA. The effects of marital status and children on savings and portfolio choice. Rev Financial Stud. 2010;23:385–432.

Uddin MA. Impact of financial literacy on individual saving: a study in the Omani context. Res World Econ. 2020;11(5):123.

Shin SH, Kim KT. Perceived income changes, saving motives, and household savings. J Financ Couns Plan. 2018;29(2):396–409.

Shahbaz M, Nawaz K, Arouri M, Teulon F, Uddin GS. On the validity of the Keynesian Absolute Income hypothesis in Pakistan: an ARDL bounds testing approach. Econ Model. 2013;35:290–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2013.07.018.

Alimi S. Keynes’ Absolute income hypothesis and Kuznets Paradox. Munich Pers RePEc Arch Keynes’ Absol. 2013; (49310):16. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/49310/.

Friedman M. Parmenent income hypothesis. Princeton: Princet Univ Press; 1957. p. 20–37.

Ando A, Modigliani F. The, “life cycle” hypothesis of saving: aggregate implications and tests. Am Econ Rev. 1963;53(1):55–84.

Thornton PK, Ericksen PJ, Herrero M, Challinor AJ. Climate variability and vulnerability to climate change: a review. Glob Chang Biol. 2014;20(11):3313–28.

Elahi E, Khalid Z, Tauni MZ, Zhang H, Lirong X. Extreme weather events risk to crop-production and the adaptation of innovative management strategies to mitigate the risk: a retrospective survey of rural Punjab, Pakistan. Technovation. 2022;117:102255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102255.

UBOS. Uganda National Household Survey Report 2016/2017. 2018. 2018; 3. http://www.ubos.org.

UBOS. Uganda bureau of statistics 2020 statistical abstract. Ubos. 2020. https://www.ubos.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/11_2020STATISTICAL__ABSTRACT_2020.pdf.

MAAIF. The Republic of Uganda Ministry of Agriculture, animal industry and fisheries, draft anual report. 2020; 1–150(October): 150. https://www.agriculture.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/MAAIF-Annual-Performance-Report-FY-2019-2020-Draft-D.pdf.

Apanovich N, Mazur RE. Determinants of seasonal food security among smallholder farmers in south-central Uganda. Agric Food Secur. 2018;7(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-018-0237-6.

Kabatalya O. savings habits, needs and priorities in rural this text is to represent savings habits, needs and. rural speed. 2005. https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADF654.pdf.

Arnab R. Simple random sampling. Survey sampling theory and applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 51–88.

Ruzzante S, Labarta R, Bilton A. Adoption of agricultural technology in the developing world: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. World Dev. 2021;146:105599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2021.105599.

Al-Jabri brahim M, Sohail MS. Mobile banking adoption: application of diffusion of innovation theory. J Electron Commer Res. 2012;13(4):379–91.

Burchfield EK, de la Poterie AT. Determinants of crop diversification in rice-dominated Sri Lankan agricultural systems. J Rural Stud. 2018;61:206–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.05.010.

Cochran WG. Sampling techniques. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 1963.

Sekele LA, Mokhaukhau JP, Cholo MS, Mayekiso A. A binary logistic analysis on factors affecting the participation of smallholder farmers in the market of Indigenous Chickens (ICs). J Agribus Rural Dev. 2020;58(4):415.

Jose A, Philip M, Prasanna LT, Manjula M. Comparison of probit and logistic regression models in the analysis of dichotomous outcomes. Curr Res Biostat. 2020;10(1):1–19.

Midamba DC, Kizito O. Determinants of access to trainings on post–harvest loss management among maize farmers in Uganda: a binary logistic regression approach. Cogent Econ Financ. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2148359.

Atube F, Malinga GM, Nyeko M, Okello DM, Alarakol SP, Okello-Uma I. Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adaptation strategies to the effects of climate change: Evidence from northern Uganda. Agric Food Secur. 2021;10(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-020-00279-1.

Gatheru M, Njarui DMG, Gichangi EM, Ndubi JM, Murage AW, Gichangi AW. Status and factors influencing access of extension and advisory services on forage production in Kenya. Asian J Agric Extension, Econ Sociol. 2021;39(3):99–113.

Ssonko GW, Nakayaga M. Credit demand amongst farmers in Mukono District, Uganda George Wilson Ssonko 1 and Marris Nakayaga. Botswana J Econ. 2014; 33–50. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/boje/article/view/113105.

Alemu A. Determinants of participation in farmers training centre based extension training in Ethiopia. J Agric Ext. 2021;25(2):86–95.

Rubhara TT. Impact of cash cropping on smallholder farming households’ food security in Shamva District, Zimbabwe. 2017; (December). http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/22646/thesis_Jansenvan rensburg_sk.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Aryal JP, Sapkota TB, Rahut DB, Krupnik TJ, Shahrin S, Jat ML, et al. Major climate risks and adaptation strategies of smallholder farmers in coastal Bangladesh. Environ Manage. 2020;66(1):105–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01291-8.

Jegede OO. Node between firm’s knowledge-intensive activities and their propensity to innovate: Insights from Nigeria’s mining industry. African J Sci Technol Innov Dev. 2020;12(7):873–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2020.1746043.

He H, Ning L, Zhu D. The impact of rapid aging and pension reform on savings and labor supply : the case of China. Int Monet Fund. 2016; 1–50. https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/WP/2019/WPIEA2019061.ashx.

Grinstein-weiss M, Zhan M, Sherraden M. Saving performance in individual development accounts: does marital status matter? J Marriage Fam. 2004;68(04):192–204.

Adekunle A. Effect of membership of group-farming cooperatives on farmers food production and poverty status in Nigeria. 30th Int Conf Agric Econ. 2018; 1–19. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/277420

Menza SK, Kebede TT. The impact of microfinance on household saving: the case of Amhara credit the impact of microfinance on household saving : the case of Amhara credit and saving institution Feres bet sub-branch, Degadamot Woreda. J Poverty, Invest Dev. 2016;2018(27):64–82.

UBOS. Uganda Bureau of Statistics. The 2018 Statistical report. 2018; 345.

Mbachu HI, Nduka EC, Nja ME. Designing a pseudo R-squared goodness-of-fit measure in generalized linear models. J Math Res. 2012. https://doi.org/10.5539/jmr.v4n2p148.

Regassa MD, Degnet MB, Melesse MB. Access to credit and heterogeneous effects on agricultural technology adoption: evidence from large rural surveys in Ethiopia. Can J Agric Econ. 2023;71(2):231–53.

Hsu Y-H, Lo H-C. The impacts of population aging on saving, capital formation, and economic growth. Am J Ind Bus Manag. 2019;09(12):2231–49.

Obayelu OA. Determinants of savings rate in Rural Nigeria: a micro study of Kwara State. J Adv Dev Econ. 2018. https://doi.org/10.13014/K2QZ2843.

Olowoyeye T, Osundare F, Ajiboye A. Analysis of Determinants and Savings Propensity of Women Cassava Processors in Ekiti State Nigeria. Glob J Human-Social Sci. 2018; 18(3). https://globaljournals.org/GJHSS_Volume18/5-Analysis-of-Determinants.pdf.

Banik N, Koesoemadinata A, Wagner C, Inyang C, Bui H. The impact of group based training approaches on crop yield, household income and adoption of pest management practices in the smallholder horticultural subsector of Kenya. J Sustain Dev Africa. 2013;15(1):117–40.

Mwaura F. Effect of farmer group membership on agricultural technology adoption and crop productivity in Uganda. African Crop Sci J. 2014;22:917–27.

Omotesho K. Determinants of level of participation of farmers in group activities in Kwara S. J Agric Fac Gaziosmanpasa Univ. 2016;33(2016–3):21–21.

Van Der LJ, Oosting S, Klerkx L, Opinya F, Omedo B. Effects of proximity to markets on dairy farming intensity and market participation in Kenya and Ethiopia. Agric Syst. 2020;184:102891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102891.

Brei M, Peter GV. The distance effect in banking and trade- working paper 658. Bank Int Settlements. 2017; (658). https://www.bis.org/publ/work658.pdf.

Zeleke AT, Endris AK. Household saving behavior and determinants of savings in financial institutions: the case of Derra District, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. Res J Financ Account. 2019; (January).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, DCM and AJ; methodology, KOO and AJ; software, DCM, KOO; validation, DCM and AJ; formal analysis, DCM and KOO; investigation, DCM and KOO; resources, AJ; data curation, DCM and KOO; writing— DCM and KOO; writing—review and editing, DCM; visualization, DCM; supervision, DCM. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Midamba, D.C., Jjengo, A. & Ouko, K.O. Assessing the determinants of saving behaviour: evidence from rural farming households in Central Uganda. Discov Sustain 5, 119 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00305-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00305-3