Abstract

Land degradation is one of the major challenges causing food insecurity and instability in Ethiopia. A comprehensive study on trends and drivers of land degradation and, socioeconomic and ecological impact of land degradation is necessary for an effective and sustainable mitigation measures. This study reviewed the drivers, trends and impacts of land degradation, existing sustainable land management (SLM) practices, and policies for land use and resources management. We employed the keyword research acquisition approach to review 122 scientific papers, reports, and other documents. The scientific literatures in the study were accessed through as the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar search engines, while reports and other additional materials were sourced from a variety of repositories and governmental offices. There has been a substantial increase in soil erosion since the 1980s in the highlands of Ethiopia. Illegal logging, poor land management system, overgrazing of pasturelands, population growth, insecure land tenure, war and conflict, poverty, ineffective government policies and programs, institutional issues, poor rural markets, and low agricultural inputs remained the major drivers for land degradation in Ethiopia causing huge loss of agricultural production and environmental unsustainability. Biological and physical soil and water conservation measures, exclosure establishment, afforestation, and reforestation programs are the most common intervention measures of preventing and restoring degraded lands. SLM practices such as intercropping systems, composting, crop rotation, zero grazing, minimum tillage, agroforestry and rotational grazing has been implemented across the country. However, land security and the absence of clearly defined property rights are the major factors that influence farmers’ decisions for a long-term investment on land resources. Thus the SLM practices and various restoration interventions remain a critical requirement to address the growing concerns of land degradation in Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Land degradation, a pervasive global issue, has significantly reduced the ability of land to provide vital ecosystem services to human beings. As we approach the third anniversary of the launch of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN), encapsulated in Target 15.3, remains a key global challenge [1]. Ethiopia has been particularly affected by land degradation contributing to rural food insecurity and aggravating local conflicts over land utilization. Approximately 50% of the rural highland areas are classified as degraded, resulting in the loss of numerous ecosystem services to the local community [2].

Land degradation has an impact on both rural livelihoods and food security and environment in Ethiopia. For instance, the agriculture in the country is under a threat because of the escalating land degradation issues. This impact is broad, affecting not only subsistence agriculture but also the nation’s economic development. The primary consequence is a direct reduction in agricultural productivity due to the loss of fertile soils, which exacerbates food insecurity [3]. The environmental issues associated with land degradation are extensive including amongst others significant soil erosion, reduced water quality, loss of biodiversity [4], diminished vegetation cover and growth [5], and reduction in ecosystem services [6].

Since the devastating famine of 1984–1985, various remedial interventions have been implemented across the country. Concurrently, numerous studies on land degradation and sustainable land management (SLM) have been undertaken in the highlands of Ethiopia [5, 7,8,9]. However, these efforts have been disjointed and inadequately documented, necessitating a comprehensive review. Furthermore, these studies have largely been confined to the Ethiopian highlands, creating a knowledge gap that requires a thorough literature review of the current government policy documents, reports, and peer-reviewed studies.

This paper, therefore, aims to fill this gap by providing an up-to-date analysis of land use, including trends in land degradation/desertification, and the drivers and impacts of land degradation. It also aims to evaluate existing SLM practices and current policies. For this study, land degradation indicators including soil erosion, depletion of soil fertility, and vegetation deforestation were used to assess the extent and severity of land degradation in the highlands of Ethiopia.

2 Methods

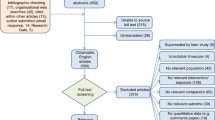

The goal of this paper is to review the drivers and trends of land degradation, impact of land degradation, existing SLM practices and policies on sustainable land use and resources in Ethiopia (Fig. 1). The information required for this study was acquired by collecting, assessing, and synthesizing data from different sources, including, among others, a review of peer-reviewed articles, government documents and reports on trends, hotspots, drivers and impacts of land degradation, existing SLM practices, land use policies in Ethiopia. Articles and book searches were done in the Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar search engines. Moreover, reports and other documents were sourced from various websites spanning from 2000 to 2023. Search phrases and keywords used in the academic databases and Google search included: “Land use in Ethiopia”, “Land degradation”, “trends of land degradation”, “hotspots of land degradation”, “drivers and impacts of land degradation”, “sustainable land management”, “land use policy of Ethiopia” and “political processes and key initiatives”. As a result, more than 410 papers were retrieved from the search engines. A total of 122 papers, after avoiding duplications, were finally selected for the review and synthesis. These include research articles (n = 72), books and book chapters (n = 15), conference proceedings (5), and reports, theses, and websites (n = 22). The materials attained from the different searches were read, assessed, and synthesized in the review process.

3 Land use, land degradation and SLM practices in Ethiopia

3.1 Land use

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [10] defines 'land' to encompass renewable natural resources such as soils, water, vegetation, and wildlife within terrestrial ecosystems. It was also defined by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) as a global bio-productive system that involves flora, soil, other biota, and the hydrological and ecological processes that function inside the system. Each ecosystem service that we use is directly or indirectly traced ultimately to land. Land provides a wide range of services that are essential for human well-being and economic development. These services include food production, water supply, climate regulation, biodiversity support, soil formation and fertility, recreation and cultural services, and raw materials and energy resources. Our lives on earth would be inconceivable without it. Land resources can be considered as land units that have direct economic usage or intrinsic value for society.

According to the FAO Database [11], the total area coverage of Ethiopia is around 1.10 million km2, of which about 90.56% is land and the remaining 9.44% is inland water bodies. The agricultural land accounts for 30.5% of the total area of the country [11]. Agricultural land includes arable land (10%), permanent cropland (0.5%), and permanent meadows and pastureland (20%) [11]. The same report also showed that, the forest area accounted for only 14.7% of the total surface area of Ethiopia of which 14.2% was naturally regenerated forest, and the remaining 0.5% was plantation forests. In total, agricultural and forest lands accounted for about 45% of the total area of the country in 1993 (Fig. 2).

The trend in the land use change since 1993 indicated that agricultural land increased while forest land decreased (Fig. 2). During this period, the portion of cropland increased from 30.5% in 1993 to 36.2% in 2015, whereas the forest land decreased from 14.7 to 12.5% [11].

3.2 Land use per capita

It has been widely argued that population pressure is among the drivers of land degradation. Moreover, land is a finite resource and cannot be expanded to increase agricultural production. Thus, with a growing population the scarcity of land increases. Ethiopia’s population in 2007 was 73.8 million and it has increased to 106.98 million in 2022 [12]. The population is also projected to reach about 130.87 million in 2032 (Fig. 3).

Ethiopia's historical, current and projected population [12]

Despite the predicted decline in the rural population from 82% in 2012 to 70.2% by 2032, the total rural population is estimated to be 95.38 million by 2032 [12]. These imply that there will be a decline in per capita land area in all the land use types than has been ever observed to these days. The trends in land per capita over the period from 1993 to 2015 indicated that the total land area per capita was 1.87 ha in1993 and this declined to almost 1 ha in 2015 [11]. In terms of the different land uses, the agricultural land per capita in 1993 was 0.57 ha and declined to 0.36 ha in 2015. Similarly, forest land per capita decreased from 0.27 ha in 1993 to 0.12 ha in 2015 (Fig. 4). Similar trends of declining land use per capita have been observed for arable land, permanent croplands, meadow and pasturelands, natural forest, and planted forest [11].

In developing countries, land is an essential asset that governs political and socio-economic activities. It also provides different ecosystem services and is used as a source of income in rural areas [13, 14]. Close to 80% of the Ethiopian population resides in rural areas where the most productive and expansive land of the country occurs [15] and an estimated 70% of the total population in the country is predicted to live in rural areas by 2032 (Fig. 3), occupying one of the largest sectors of the economy in a country where agriculture accounts for 46.3% of the GDP, about 84% of the commodities for export and 80% of the labor force [16].

3.3 Land degradation

Land degradation has become an international issue of the twenty-first century because of its wide-ranging impacts on development and the environment. More specifically, it affects agricultural production, food security, and human well-being [17].

Land degradation is a process that reduces the capability of the land to carry out functions of vital importance and provision of ecosystem services. UNCCD defines land degradation as “any reduction or loss in the biological or economic productive capacity of the land resource base”. The major causes of land degradation are related to anthropogenic activities and aggravated by natural phenomena. Furthermore, other interlinked factors such as climate change and biodiversity loss also tend to amplify land degradation. This definition implies that land degradation is contextual and there has been no accurate measurement of the extent of degradation [18].

Land degradation can be initiated by different natural and man-made processes that reduce the production capacity of the land and ultimately cause long-standing and often irreversible harm to the land. Soil erosion by wind and water, fertility loss, accumulation of acid and salts in the soil, reduction in cation retention capacity, hard soil layer formation by crusting and compaction, and decrease in total biomass carbon and biodiversity are among the primary processes of land degradation [19].

Land degradation is a process gaining strong focus for its impact on food security and economic well-being of countries, and the living conditions of individual people on the planet [20]. According to Hurni et al. [5], in Ethiopia, land degradation can be traced back to the time of the Axumite kingdom, where forests were cleared for agricultural expansion [21], dating back as far as 3000 years ago [22]. Moreover, as Berry [23] indicated, declining land productivity in Ethiopia is an issue that requires urgent attention considering the recent surge of the population in the country and projected trends to increase in the future.

With an estimated 85% of degraded land in Ethiopia [24], land degradation, is one of the principal environmental challenges of the country. Previous studies reported that land degradation is affecting about 70% of the inhabitants in the Ethiopian highlands and an area of more than 40 million hectares [25]. According to the remote sensing-based estimates, the degraded land for the last thirty years alone constitutes about 23% of the total area in the country [24]. The extent of the annual soil erosion reported varies from 16 to 300 tons ha−1 yr−1, depending on the surface slope, land cover, and rainfall intensities [26, 27]. These losses could have contributed to about 1–1.5 million tons increase in the crop production of the country [7].

Water-induced soil erosion is the most common form of land degradation in Ethiopia and this has rapidly increased over the last few decades mainly due to unsustainable land use/cover practices [24]. Soil erosion is regarded as one of the main factors that prompt land degradation and is liable for environmental challenges constraining the efforts made to achieve food security and future development possibilities by the country [28]. Due to the prevalence of higher soil erosion rates compared to many other countries in the continent, Ethiopia is regarded as one of the most susceptible countries to land degradation [29].

Despite a plethora of studies indicating considerable information about soil erosion in Ethiopia since the mid-1980s, the reliability and consistency of data related to the rate and extent of soil loss remains anecdotal [24, 30]. This is due to various factors, including, inter alia, the lack of basic data for erosion assessment, the use of different methodologies and models, and the complexity of the erosion processes and controlling factors it [30, 31]. Previous studies for estimating total soil loss are limited and differ in aerial extent (either at a regional or national scale) mapped, and methodology used, and consequently, the results obtained [32]. For example, Sonneveld et al. [33] developed a provisional soil loss map of Ethiopia by fusing the estimates of different models and accordingly, they obtained a soil loss ranging from 0 t ha−1y−1 in the east and southeastern parts and exceeding 100 ton ha−1 year−1 in the north-west parts of the country. Obtaining estimates of soil loss involves analyzing complex patterns of spatio-temporal variability, and conceptual and methodological challenges [24]. There is also significant variability in estimating the rate of soil erosion arising from variations in agro-ecology and soil types. Moreover, the soil degradation process varies significantly spatially [32, 34, 35]. Soil erosion occurs at varying rates and with varying degrees in different parts of the country. Haregeweyn et al. [32], in their review on soil erosion and conservation in Ethiopia, indicated that the national scale estimates of soil loss are both tentative and inconsistent.

3.4 Trends of land degradation

Land degradation is a significant issue in Ethiopia, with evidence of increasing trends reported currently [8]. The extent of land degradation in Ethiopia is significant, with more than 85% of the land estimated to be moderately to severely degraded [8]. Few site-specific studies also showed that land degradation is increasing. For instance, according to a study conducted in the north-western parts of the country (around Lake Tana), low to moderate levels of soil erosion were observed in 68% of the watershed, 31% faces high to extremely high levels of soil erosion and the remaining 1% exhibited exceptionally high (more than 100 ton ha−1 year−1) erosion rates in the watershed [36]. Haregeweyn et al. [37] conducted a study in the Gilgel-tekeze catchment of northern Ethiopia to investigate the effects of land use and land cover changes on hydrologic responses. They found there was a rise in yearly surface runoff generated of up to 101 mm and a decline in recharge of groundwater aquifers of 39 mm from 1976 to 2003. These changes were attributed to the increase in agricultural land, which increased by 15% at the expense of shrubland, which decreased by 19%. Gessesse et al. [38] also found an increase of 14.2% and 37% in surface runoff and sediment yield, respectively, in the Modjo watershed, Ethiopia. Le et al. [39], estimated the areal coverage of land degradation in Ethiopia increased by about 228,160 km2 (or 23% of the total area) from 1982 to 2006. On the contrary, Nyssen et al. [40] claimed that there has been a positive change in the last 140 years in vegetation cover and better soil protection in Northern Ethiopia. Similarly, Belay et al. [41] found an improved vegetation cover in Eastern Tigray, Ethiopia since 1994, compared to the period between 1965 and 1994. Land degradation is a site-specific issue that varies depending on the location, with some areas showing an increasing trend of land degradation, while others show efforts to reverse land degradation. However, on a country-wide scale, land degradation is increasing at an alarming rate.

3.5 Hotspots of land degradation

There have been repeated endeavors to detect the extent and severity of land degradation worldwide. Both the extent and seriousness of the issue show spatial differences depending on the variations in elevation, ecology, precipitation, land use/cover, and soil types. There were no studies that showed a comprehensive analysis of hotspots of land degradation in Ethiopia at a national scale. Most of the studies focused on the landscape level.

However, according to the existing literature, land degradation in Ethiopian highlands is more severe than in other parts of the country with an estimated net soil loss ranging from 0.4 to 88 tons ha−1 year−1 and an average rate of 12 tons ha−1 year−1 [42, 43]. Hermans-Neumann et al. [44] identified, the hotspot location of land degradation to be the northern highlands, parts of the Awash Valley, regions surrounding Lake Tana, the mountainous areas splitting Addis Ababa, Bedele, and Jima, and central parts of the Great Rift Valley as land degradation hotspot areas. Mekonnen and Melesse [36] also identified the Northwest Ethiopian highlands as an erosion-prone area with a soil loss, ranging between 0.0046 and 192 tons ha−1 yr−1.

The regions with low soil fertility in Ethiopia, particularly the densely populated highlands like Tigray, face challenges of nitrogen and phosphorus deficiencies, leading to decreased crop yields and diminishing soil quality [45]. Inappropriate land use systems, mono-cropping, and inadequate nutrient supply are among the contributing factors to the decline in soil physical, chemical, and biological properties in these areas. Similarly, the central highlands of Ethiopia, characterized by Vertisols, also face with poor soil fertility due to erosion, intensive farming practices, and nutrient depletion [46]. Higher nutrient losses due to a lack of soil management practices, crop rotation, and planting of leguminous plants were also observed in the Northwestern of Ethiopia [47].

Moreover, the increasing demand for agricultural land, fuelwood, and building materials due to population growth has intensified pressure on forests in Ethiopia, resulting in deforestation and degradation [8]. Areas with high vegetation degradation and deforestation are concentrated in densely populated highlands like Tigray, where significant soil loss, deforestation, and reduced vegetation coverage are of critical concerns [8]. Similarly, the Afromontane forests in southern Ethiopia, are at risk due to agricultural expansion and deforestation, threatening the biodiversity and ecosystems of the region [48]. The Kaffa Biosphere Reserve in the southwestern part of Ethiopia is experiencing significant forest loss primarily due to a substantial increase in agricultural land by 87.9% and settlement areas by 157%, leading to a notable decrease in the area of natural habitats [49]. Studies have also highlighted the Northern part of Ethiopia as heavily degraded due to various interlinked environmental pressures [50,51,52,53].

3.6 Drivers of land degradation

3.6.1 Population growth

Population growth in Ethiopia has a profound impact on land degradation, leading to various environmental challenges and affecting the sustainability of agricultural practices. According to the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA) projection, Ethiopia’s population is expected to reach 143 million by 2037 [12]. The rapid increase in population exerts pressure on natural resources, resulting in soil degradation, vegetation loss, and water degradation across the country. A study by Bard et al. [54] on the environmental history of Tigray (northern Ethiopia) with a special focus on the Aksumite kingdom (from 400 BC to 800 AD) revealed that demographic pressures were among the major contributors to soil erosion in the region. Grepperud [55] explicitly stated that human and livestock population pressures have an identifiable impact on land degradation only when the population is more than the threshold carrying capacity of the land. Similarly, various authors stated that fast-increasing population growth is among the major causes of land degradation in Ethiopia [56,57,58].

Studies have underscored the adverse impacts of population growth on land resources, highlighting the connection between rising population numbers and the deterioration of arable land in Ethiopia [59]. As the population expands, the demand for vital resources like fuel, construction materials, and agricultural land increases, fostering unsustainable land use practices and contributing to soil erosion and degradation [7]. The process of extensification, propelled by population growth, results in forest clearance, cultivation on marginal lands, and overgrazing, further worsening land degradation in the country [8]. This unsustainable expansion of agricultural activities into upland and marginal areas, along with deforestation, significantly impacts land resources in Ethiopia, leading to a decline in soil quality and agricultural productivity [60].

3.6.2 Land use/ land cover dynamics

Land use/ land cover change is regarded as one of the main drivers of land degradation in Ethiopia [61,62,63]. For instance, Meshesha et al. [62] asserted that the eastern Ethiopian highlands are susceptible to adverse water-based soil erosion processes mainly due to land use/ land cover changes, amongst others. Similarly, WoldeYohannes et al. [63] studied land cover land use dynamics in the Abaya-Chamo Basin, south Ethiopia, and found higher soil erosion, increased runoff, and sediment transport thereby affecting the amount and quality of water in the lakes. Other scholars also stated that land use land cover dynamics are among the drivers of land degradation [24, 57, 64].

3.6.3 Climate change

Climate change significantly impacts land degradation, affecting the environment, ecosystems, and human livelihoods. Land degradation, characterized by a negative trend in land conditions due to human-induced processes, is exacerbated by climate change [65]. The intricate relationship between climate change and land degradation is influenced by various factors. Climate change directly and indirectly affects soil processes, sometimes leading to catastrophic events like severe floods and their aftermath, contributing to land degradation [54, 66, 67].

In Ethiopia, climate change has a profound impact on land degradation, exacerbating environmental challenges and impacting community livelihoods. Studies by Hurni et al. [66] and Nyssen et al. [67] highlighted that climate change, along with rapid population growth and ineffective land and water management practices, largely drives land degradation in Ethiopia. The country’s susceptibility to climate change is evident in the increasing variability and shifts in climate patterns, leading to significant effects on agricultural practices and land management approaches [68, 69]. Research emphasizes that climate change can escalate soil erosion, crop damage, and waterlogging, making land cultivation challenging or impossible, particularly in regions like the Agewmariam watershed in Northern Ethiopia [70]. Additionally, Bard et al. [54] emphasized in their study on the environmental history of Tigray that a combination of a drier climate and human activity played a significant role in contributing to soil erosion in the region during that historical period.

3.6.4 Poor agricultural land and water management

Poor agricultural land and water management are significant factors contributing to land degradation in Ethiopia [58, 62, 66]. This issue has led to the degradation of more than 85% of the country’s land to various degrees [24]. The most common form of land degradation in Ethiopia is soil erosion by water, which is exacerbated by factors such as deforestation, overgrazing, cultivation on steep slopes, and unsustainable farming practices [71]. Rain-fed agriculture, which employs 80% of the population, is particularly vulnerable to land degradation, as it relies on the sustainable management of land and water resources [72].

3.6.5 Insecure land tenure system

Land degradation in Ethiopia is a complex issue shaped by a multitude of factors. The insecure land tenure system in Ethiopia has a significant impact on land degradation, leading to soil erosion, low incomes, and environmental challenges. Studies highlight that the lack of secure land tenure contributes to soil erosion and degradation, exacerbating food insecurity issues in the country [73, 74]. Lanckriet et al. [56] conducted an insightful study into how land tenure policies during three distinct political eras influenced this issue. These eras comprised the Feudal period (1940–1974), the Dergue regime (1974–1991), and the EPRDF government (1991–2018). The analysis revealed that land degradation was most severe during the Feudal period due to a stark imbalance in land rights. Essentially, poor farmers were compelled to cultivate on marginal and steep slope lands, exacerbating the problem.

The relationship between land tenure security and land degradation is crucial, as insecure land tenure systems can result in unsustainable land use practices, reduced investments in sustainable land management, and overall environmental decline [75, 76]. In Ethiopia, where land degradation is a pressing issue, the insecure land tenure system hinders sustainable land use practices and contributes to soil erosion, which further leads to decreased agricultural productivity and livelihood challenges for local communities [73]. The absence of secure land rights can also discourage farmers from investing in soil conservation measures or adopting sustainable agricultural practices, perpetuating a cycle of environmental degradation and poverty. Studies by Legesse et al. [76], Mengesha et al. [77], and Teshome et al. [78] all suggest that farmers are more likely to invest long-term in land they own outright, rather than shared or leased land.

Interestingly, a counterpoint to this narrative is offered by Moreda [74]. In a study conducted in two sites within the Amhara region, it was discovered that farmers with insecure land rights were making significant efforts to mitigate the damaging effects of land degradation. This finding contradicts the common belief that there is an inverse relationship between land security and degradation.

3.6.6 War and conflict

The impact of war and armed conflict on land degradation in Ethiopia is profound, exacerbating existing environmental challenges and leading to further deterioration of the nation's land resources. The study by Hishe et al. [79], highlights that armed conflict has resulted in the abandonment of farmland and villages, causing a decline in vegetation density. Furthermore, Negash et al. [80] demonstrated that the overuse of woody vegetation for firewood and charcoal has intensified due to the absence of alternative energy sources, contributing to land degradation. Another consequence of these conflicts is the loss of wildlife populations, significantly impacting the overall ecosystem [80]. Moreover, the destruction of forests and conservation structures caused by military activities has further worsened environmental degradation [81].

The displacement of approximately 2.1 million people due to the November 2020 Tigray conflict has added to the environmental challenges. Displaced individuals often resort to using firewood for cooking and timber for temporary shelters, leading to increased pressure on the already dwindling vegetation resources [81]. Unsustainable agricultural practices, changes in land cover, and inadequate regulatory frameworks have also contributed to soil erosion and pollution in the region [24].

As we distill the information from these studies, it becomes clear that land degradation in Ethiopia is not the result of a single driving factor but rather a suit of interlinked complex factors. Key drivers of land degradation include rapid population growth, land use changes leading to over-grazing and deforestation, poor agricultural practices and land management systems, and climate change-related natural phenomena. The land tenure system, with its issues of security and rights, also plays a pivotal role. Therefore, it is essential to understand these complexities when seeking solutions to mitigate land degradation in Ethiopia.

3.7 Impacts of land degradation

Land degradation significantly impacts both socioeconomic and ecological aspects worldwide. It manifests in myriad ways—once lush vegetation dwindles, rivers run dry, fields formerly rich are now overrun with thorny weeds, trails morph into gorges, and soils become thin and stony. These signs pose grave implications for the environment, for those who utilize the land, and for people whose livelihoods hinge on a healthy landscape [23]. Land degradation plays a crucial role in perpetuating poverty, diminishing ecosystem resilience, and the provision of environmental services [82]. Moreover, the ripple effects of land degradation and environmental decay reach far and wide, influencing human health [83].

In Ethiopia, despite the lack of comprehensive national data on land degradation, it is clear that the phenomenon has detrimental effects on household food security and directly undermines the livelihoods of rural inhabitants [24]. In the short term, land degradation leads to reduced crop yields, which in turn escalate poverty levels among farming households. Teketay [84] estimated that soil erosion in just 1 year (1991) caused a significant reduction in grain yield, ranging from 57,000 tons at a soil depth of 3.5 mm to 128,000 tons with a soil depth of 8 mm. Similarly, Berry [23] estimated a 3% decline (equivalent to $106 million in 1994) in Ethiopia's agricultural GDP due to land degradation and associated poor land management practices. Sonneveld [85] used a model to predict a food production loss of 10–30% by 2030 due to soil erosion. An estimated 1.5 billion tons of topsoil is washed away every year in Ethiopia, and this significantly affects the income and food security of smallholder farmers. The annual cost of land degradation in the country was estimated to be $4.3 billion [24]. Its impacts on smallholder-based maize and wheat production were also about $162 million—representing 2% of the country's national GDP in 2007 [24].

The environmental repercussions of land degradation are vast and complex, particularly in arid and developing countries. It affects a broad array of ecosystem functions and services through both direct and indirect processes [86]. For instance, Tolessa et al. [87] found a loss of $3.69 million in ecosystem services over 38 years (1973–2015) due to changes in forest cover in Ethiopia’s central highlands. They reported that nutrient recycling, raw material supply, and erosion control are among the ecosystem functions showing a declining trend.

Similarly, Kassa et al. [64] reported a decrease in biodiversity in Southwest Ethiopia due to the extensive cultivation of tea, soapberry, coffee, and other cereals. Likewise, changes in land use and land cover in forests, cultivated areas, and grasslands have led to a considerable reduction in key soil quality indicators such as organic carbon, total nitrogen, phosphorus, and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) spore density in the northern Ethiopian highlands [88].

3.8 Land degradation prevention and methods of restoring degraded lands

Land degradation, a serious environmental issue, can be effectively mitigated through various targeted strategies, the choice of which is largely contingent on the specific type and extent of degradation. For instance, soil degradation can be mitigated by supplementing nutrient-poor soil, enhancing the topsoil quality through amendments, afforestation and reforestation, and managing soil acidity to maintain it at non-toxic levels [89]. In line with this, Coxhead and Oygard [90] have underscored the importance of increasing vegetation cover, replenishing nutrients, and constructing soil and water conservation structures as core environmental principles to curb land degradation.

In the rural landscapes of Ethiopia, the compounded challenges of land degradation, climate change, and food insecurity can be sustainably resolved through forest establishment and restoration practices [91]. Indeed, the country has seen the widespread implementation of soil and water conservation structures as principal methods for soil restoration and preservation [92]. Over a span of 30 years, noticeable improvements in vegetation cover and positive impacts on soil physicochemical properties have been reported, owing to the integration of soil and water conservation measures [93, 94].

Since the 1970s, Ethiopia has been actively engaging in land degradation control measures, such as landscape restoration and water-harvesting practices [95, 96]. Biological amendments, such as Pennisetum purpureum and Sesbania sesban, have demonstrated significant beneficial impacts on the soil properties of degraded lands [96]. Community labour mobilization for conservation practices and cover management resulted in a 42% decrease in relative soil loss [97].

Area exclosure for forest regeneration has been identified as a potent measure against land degradation, leading to an increase in tree species richness with the age of land abandonment in degraded grazing lands of Northern Ethiopia [98, 99]. The conversion of degraded communal grazing lands into exclosures has been proposed as a viable option for soil rehabilitation [51]. Reforestation and afforestation interventions have also been implemented to reverse land degradation trends [71, 98, 100].

Overall, a multi-pronged approach to land degradation, which includes afforestation, reforestation, soil and water conservation, and the application of biological amendments, has proven effective in mitigating land degradation in Ethiopia. The success of these efforts is a testament to the potential of sustainable land management strategies in preserving our natural resources for future generations. The challenge moving forward is to ensure the continuity and scale-up of these efforts, strengthen the integration of scientific research into policy and practice, and enhance community involvement in land management activities.

3.9 Existing SLM practices

Land degradation significantly impacts human well-being, both directly and indirectly. Solving land degradation problems could, therefore, contribute comprehensively to the achievement of many of the remaining SDGs. Addressing land degradation involves the development and application of various technologies, policies, and strategies leading to SLM. In Ethiopia, the government, in collaboration with other stakeholder institutions, has implemented SLM programs to manage land degradation for the last decades [101].

SLM aims at the implementation of various strategies and technologies to manage land, water, biodiversity, and other environmental resources. This integrated approach meets the needs of humans while preserving the future use of these natural resources and their environmental services [102]. SLM interventions include agronomic actions (like inter-cropping and contour cultivation), vegetation efforts (such as tree plantation and hedge barriers), structural measures (like the formation of bench-terrace and bunds), and management strategies (like land cover/use dynamics and area-closures).

Given the widespread land degradation in Ethiopia, the socioeconomic, environmental, and ecological setup of the country is significantly impacted. Since 1991, the people and the government of Ethiopia have implemented various programs to combat, reclaim, and protect natural resources, including the SLM program. The SLM practices being implemented encompass a variety of techniques such as intercropping, composting, crop rotation, fallowing, contour cultivation, mulching, tree planting, soil and water conservation structures, area exclosure, reforestation and afforestation, zero grazing, minimum tillage, agroforestry, and rotational grazing [103,104,105,106].

In the Eastern Tigray’s semi-arid area of northern Ethiopia, measures taken to resolve land degradation problems included improved tillage, formation of terraces, crop rotation, application of crop residues and barnyard manures, and incorporation of weeds [107, 108]. In some areas of Tigray and neighboring regions, the development of sloping terraces is a longstanding practice by farmers without external support [109]. Over the last 29 years, the Tigray region has made significant achievements in soil and water conservation, adding 1.2 million hectares of land for crop production. As a result, the region was internationally recognized with a gold medal for its greening programs in drylands and its achievements [110].

Minimum tillage has been used as a mechanism for improving crop yields in the Ethiopian highlands [111]. Similarly, grazing management on communal lands has been implemented in Northern Ethiopia to enhance the sustainable utilization of resources and overcome feed scarcities [112].

Schmidt and Tadesse [113], used panel survey data from 4 years (2010–2014) to investigate the impact of SLM on agricultural productivity. The results suggested that continuous maintenance is required to gain substantial benefits from SLM programs. Another study by Schmidt et al. [114] investigated the impact of investments in SLM and other complementary measures on the livelihood of subsistence farmers. The authors concluded that SLM program investments should be maintained for at least 7 years to observe a noticeable increase in produce value. They also found that terraces constructed on medium to steep slopes are more productive.

Gebreselassie et al. [24] investigated the adoption level of farmers for six main SLM interventions in Ethiopia. These practices include crop rotation, intercropping, improved seeds, use of manuring, application of chemical fertilizers, and soil erosion control. The analysis indicated that the leading determinant factors for the success of SLM in Ethiopia fall under biophysical, demographic, regional, and socio-economic determinants. Meanwhile, the availability of agricultural extension, land-tenure security, and market accessibility are the necessary motivators that control the type and number of SLM technologies to implement.

4 Land policies in Ethiopia and its implications for land degradation

Land use policy plays a pivotal role in agricultural production. However, it is difficult to establish a universally applicable land policy due to the considerable variability in geographical, social, and cultural variables across different nations [115].

Ethiopia's current land policy is grounded in the Land Reform Proclamation of 1975, which saw all rural land nationalized and private land ownership abolished. The goal of this policy was to rectify historical inequalities in land distribution and foster agricultural development. The policy posits that the state owns the land, with farmers only having the right to use it [15, 116, 117]. As per the Proclamation No. 1/1995 constitution in Article 40, the land policy of the country stipulates that “The right to ownership of rural and urban land, as well as of all natural resources, is exclusively vested in the state and the peoples of Ethiopia. Land is a common property of the Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples of Ethiopia and shall not be subject to sale or other means of exchange [118].” In addition, Sub Article 7 regarding property rights asserts that "Every Ethiopian shall have the full right to the immovable property he builds and to the permanent improvements he brings about on the land by his labor or capital. This right shall include the right to alienate, to bequeath, and, where the right of use expires, to remove his property, transfer his title, or claim compensation for it [118]."

The land policy in Ethiopia, a significant source of power, is often the subject of heated debates. Two opposing perspectives dominate the discourse. The Ethiopian government champions state land ownership, with landholders only granted usufruct rights, excluding the right to sell or mortgage the land. The intention is to safeguard rural peasants from selling their land to wealthier individuals, risking landlessness and loss of livelihood.

Conversely, there are proponents for individual land ownership, arguing that individuals should possess the right to own and transfer land. They argue that state land ownership hampers the development of a land market, deters farmers from investing in land, suppresses land productivity, and promotes unsustainable land use practices leading to land degradation. Critics also point out the policy’s lackluster implementation and its questionable efficacy in addressing issues of household farmland access.

Land security and ill-defined property rights significantly impact farmers' decisions to invest in land [13, 76, 119, 120]. Land tenure insecurity has been identified as a considerable impediment to agricultural growth and natural resource management. To mitigate this, the government has initiated measures like land certification and registration reforms in various regions, serving as a guarantee for the right to use farmland [121, 122].

Despite these efforts, challenges persist in enforcing the land policy. Instances of land grabs, where large-scale investors acquire land for commercial purposes, often displacing local communities, have been reported. This has sparked conflicts over land rights and raised questions about the fairness and transparency of land allocation processes.

5 Conclusion

The study demonstrated that land degradation has increased over the recent decades, especially in the highlands of Ethiopia. Land degradation is triggered by different factors including, but not limited to, land use land cover change, climate change, war, poor land management system, and population growth. Construction of soil and water conservation structures, exclosure establishment, and afforestation/reforestation are the most common methods of preventing land degradation while restoring degraded areas in Ethiopia. Sustainable land management (SLM) practices such as intercropping, composting, crop rotation, fallowing, contour cultivation, mulching, tree planting, grass strips, zero grazing, minimum tillage, Agroforestry, and rotational grazing have been implemented across Ethiopia. Various strategies, sectoral policies, and plans were designed, which are in line with the sustainable development goals, and implemented to achieve sustainable development in the country. However, land security and the absence of clearly defined property rights are considered crucial factors that affect farmers’ decision to long-term investment in land. Engaging high-level policymakers to combat land degradation and its future restoration actions is crucial. We envisage that the findings of this review could be used by all concerned stakeholders for their decision-making process on the restoration of degraded lands across the country.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

United Nations. Revised list of global Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. 2017.

Tongul H, Hobson M, editors. Scaling up an integrated watershed management approach through social protection programmes in Ethiopia: the MERET and PSNP schemes. Conference Papers Hunger, Nutrition, Climate Justice Conference; 2013.

Gebrehiwet KB. Land use and land cover changes in the central highlands of Ethiopia: the case of Yerer Mountain and its surroundings. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2004.

Pacheco FAL, Sanches Fernandes LF, Valle Junior RF, Valera CA, Pissarra TCT. Land degradation: multiple environmental consequences and routes to neutrality. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2018;5:79–86.

Hurni H, Abate S, Bantider A, Debele B, Ludi E, Portner B, et al. Land degradation and sustainable land management in the highlands of Ethiopia. In: Hurni H, Wiesmann U, editors., et al., Global change and sustainable development: a synthesis of regional experiences from research partnerships. 5th ed. Bern: Geographica Bernensia; 2010. p. 187–207.

Muleta TT, Kidane M, Bezie A. The effect of land use/land cover change on ecosystem services values of Jibat forest landscape Ethiopia. GeoJournal. 2021;86(5):2209–25.

Taddese G. Land degradation: a challenge to Ethiopia. Environ Manage. 2001;27(6):815–24.

Wassie SB. Natural resource degradation tendencies in Ethiopia: a review. Environm Syst Res. 2020;9(1):33.

Deche A. Land degradation and its management in the highlands Ethiopia a review. J Waste Manag Xenobiot. 2023;6(3):1–10.

MA. Ecosystems and human well-being—Synthesis: A Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Washington, D.C; 2005.

FAOSTAT. 2018. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data. Accessed 18 May 2020

CSA. Population projections for Ethiopia 2007–2037. Addis Ababa: Population Census Commission; 2013.

Bogale A, Taeb M, Endo M. Land ownership and conflicts over the use of resources: implication for household vulnerability in eastern Ethiopia. Ecol Econ. 2006;58(1):134–45.

Toulmin C. Securing land and property rights in sub-Saharan Africa: the role of local institutions. Land Use Policy. 2009;26(1):10–9.

Nalepa RA, Short Gianotti AG, Bauer DM. Marginal land and the global land rush: a spatial exploration of contested lands and state-directed development in contemporary Ethiopia. Geoforum. 2017;82:237–51.

IMF. The federal democratic Republic of Ethiopia: selected issues. Washington: International Monetary Fund; 2008.

Eswaran H, Lal R, Reich P, editors. Land degradation: An overview In: Bridges, EM, ID Hannam, LR Oldeman, FWT Pening de Vries, SJ Scherr, and S. Sompatpanit (eds). Responses to Land Degradation. In: Proc 2nd International Conference on Land Degradation and Desertification, Khon Kaen, Thailand Oxford Press, New Delhi, India; 2001.

Reynolds J, Grainger A, Smith DS, Bastin G, Garcia-Barrios L, Fernández R, et al. Scientific concepts for an integrated analysis of desertification. Land Degrad Dev. 2011;22(2):166–83.

Sivakumar MVK, Ndiangui N. Climate and Land Degradation. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg; 2007.

Tefera B. Nature and causes of land degradation in the Oromiya Region: a review. Addis Ababa: ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD); 2002.

Nyssen J, Frankl A, Zenebe A, Deckers J, Poesen J. Land management in the Northern Ethiopian highlands: local and global perspectives; past, present and future. Land Degrad Dev. 2015;26(7):759–64.

Darbyshire I, Lamb H, Umer M. Forest clearance and regrowth in northern Ethiopia during the last 3000 years. Holocene. 2003;13(4):537–46.

Berry L. Land degradation in Ethiopia: its impact and extent Commissioned by global mechanism with support from the World Bank; 2003.

Gebreselassie S, Kirui OK, Mirzabaev A. Economics of land degradation and improvement in Ethiopia. In: Nkonya E, Mirzabaev A, von Braun J, editors. Economics of land degradation and improvement—a global assessment for sustainable development. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 401–30.

Tadesse M. Sustainable land management program in Ethiopia: Linking Local REDD+projects to national REDD+ strategies and initiatives. 2013.

Nkonya E, Mirzabaev A, Von Braun J. Economics of land degradation and improvement: a global assessment for sustainable development. Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London: Springer; 2016.

Woldemariam GW, Iguala AD, Tekalign S, Reddy RU. Spatial modeling of soil erosion risk and its implication for conservation planning: the case of the Gobele Watershed, East Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia. Land. 2018;7(1):25.

Wagayehu B. Economics of soil and water conservation: theory and empirical application to subsistence farming in the eastern Ethiopian highlands. Doctoral thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences: Uppsala. 2003.

Jolejole-Foreman MC, Baylis KR, Lipper L. Land Degradation’s Implications on Agricultural Value of Production in Ethiopia: A look inside the bowl. 2012.

Tamene L, Abera W, Demissie B, Gessesse GD, Woldearegay K, Mekonnen K. Soil erosion assessment in Ethiopia: a review. J Soil Water Conserv. 2022;77(2):144–57.

Esa E, Assen M, Legass A. Implications of land use/cover dynamics on soil erosion potential of agricultural watershed, northwestern highlands of Ethiopia. Environ Syst Res. 2018;7(1):21.

Haregeweyn N, Tsunekawa A, Nyssen J, Poesen J, Tsubo M, Tsegaye Meshesha D, et al. Soil erosion and conservation in Ethiopia: a review. Prog Phys Geogr. 2015;39(6):750–74.

Sonneveld B, Keyzer M, Stroosnijder L. Evaluating quantitative and qualitative models: an application for nationwide water erosion assessment in Ethiopia. Environ Model Softw. 2011;26(10):1161–70.

Hadgu KM, Rossing WAH, Kooistra L, van Bruggen AHC. Spatial variation in biodiversity, soil degradation and productivity in agricultural landscapes in the highlands of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2009;1(1):83–97.

Othmani O, Khanchoul K, Boubehziz S, Bouguerra H, Benslama A, Navarro-Pedreño J. Spatial variability of soil erodibility at the Rhirane catchment using geostatistical analysis. Soil Systems. 2023;7(2):32.

Mekonnen M, Melesse AM. Soil Erosion mapping and hotspot area identification using GIS and remote sensing in northwest ethiopian highlands, near Lake Tana. In: Melesse AM, editor. Nile River Basin: hydrology, climate and water use. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands; 2011. p. 207–24.

Haregeweyn N, Tesfaye S, Tsunekawa A, Tsubo M, Meshesha DT, Adgo E, et al. Dynamics of land use and land cover and its effects on hydrologic responses: case study of the Gilgel Tekeze catchment in the highlands of Northern Ethiopia. Environ Monit Assess. 2014;187(1):4090.

Gessesse B, Bewket W, Bräuning A. Model-based characterization and monitoring of runoff and soil erosion in response to land use/land cover changes in the modjo watershed Ethiopia. Land Degrad Dev. 2015;26(7):711–24.

Le QB, Nkonya E, Mirzabaev A. Biomass Productivity-based mapping of global land degradation hotspots. In: Nkonya E, Mirzabaev A, von Braun J, editors. Economics of land degradation and improvement – a global assessment for sustainable development. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 55–84.

Nyssen J, Haile M, Naudts J, Munro N, Poesen J, Moeyersons J, et al. Desertification? Northern Ethiopia re-photographed after 140 years. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407(8):2749–55.

Belay KT, Van Rompaey A, Poesen J, Van Bruyssel S, Deckers J, Amare K. Spatial analysis of land cover changes in eastern tigray (Ethiopia) from 1965 to 2007: are there signs of a forest transition? Land Degrad Dev. 2015;26(7):680–9.

Tamene L, Adimassu Z, Ellison J, Yaekob T, Woldearegay K, Mekonnen K, et al. Mapping soil erosion hotspots and assessing the potential impacts of land management practices in the highlands of Ethiopia. Geomorphology. 2017;292:153–63.

FDRE. Ethiopia—land degradation neutrality national report. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia; 2015.

Hermans-Neumann K, Priess J, Herold M. Human migration, climate variability, and land degradation: hotspots of socio-ecological pressure in Ethiopia. Reg Environ Change. 2017;17(5):1479–92.

Abebe T, Shitu K, Mekonnon H. To review studies conducted on soil fertility management measures and their role in improving soil fertility. Ann Earth Sci Geophys. 2022;1(1):1–7.

Hailu H, Mamo T, Keskinen R, Karltun E, Gebrekidan H, Bekele T. Soil fertility status and wheat nutrient content in vertisol cropping systems of central highlands of Ethiopia. Agric Food Secur. 2015;4(1):19.

Lewoyehu M, Alemu Z, Adgo E. The effects of land management on soil fertility and nutrient balance in Kecha and Laguna micro watersheds, Amhara Region, Northwestern, Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020;6(1):1853996.

Tekle T, Maryo M. Ecological assessment of woody plant diversity and the associated threats in afromontane forest of Ambericho, Southern Ethiopia. J Landsc Ecol. 2022;15(2):102–26.

Mengist W, Soromessa T, Feyisa GL. Monitoring Afromontane forest cover loss and the associated socio-ecological drivers in Kaffa biosphere reserve, Ethiopia. Trees, Forests People. 2021;6:100161.

Girmay G, Singh BR, Dick Ø. Land-use changes and their impacts on soil degradation and surface runoff of two catchments of Northern Ethiopia. Acta Agric Scand, Sect B—Soil Plant Sci. 2010;60(3):211–26.

Mekuria W, Aynekulu E. Exclosure land management for restoration of the soils in degraded communal grazing lands in Northern Ethiopia. Land Degrad Dev. 2013;24(6):528–38.

Taye G, Poesen J, Wesemael BV, Vanmaercke M, Teka D, Deckers J, et al. Effects of land use, slope gradient, and soil and water conservation structures on runoff and soil loss in semi-arid Northern Ethiopia. Phys Geogr. 2013;34(3):236–59.

Girmay G, Singh BR, Nyssen J, Borrosen T. Runoff and sediment-associated nutrient losses under different land uses in Tigray Northern Ethiopia. J Hydrol. 2009;376(1):70–80.

Bard KA, Coltorti M, DiBlasi MC, Dramis F, Fattovich R. The environmental history of tigray (Northern Ethiopia) in the middle and late holocene: a preliminary outline. Afr Archaeol Rev. 2000;17(2):65–86.

Grepperud S. Population pressure and land degradation: the case of Ethiopia. J Environ Econ Manag. 1996;30(1):18–33.

Lanckriet S, Derudder B, Naudts J, Bauer H, Deckers J, Haile M, et al. A political ecology perspective of land degradation in the North Ethiopian Highlands. Land Degrad Dev. 2015;26(5):521–30.

Miheretu BA, Yimer AA. Land use/land cover changes and their environmental implications in the Gelana sub-watershed of Northern highlands of Ethiopia. Environ Syst Res. 2017;6(1):7.

Meshesha DT, Tsunekawa A, Tsubo M. Continuing land degradation: cause–effect in Ethiopia’s central rift valley. Land Degrad Dev. 2012;23(2):130–43.

Gashaw TGT, Behaylu ABA, Tilahun ATA, Fentahun TFT. Population growth nexus land degradation in Ethiopia. J Environ Earth Sci. 2014;4(11):54–7.

Yesuph AY, Dagnew AB. Land use/cover spatiotemporal dynamics, driving forces and implications at the Beshillo catchment of the Blue Nile Basin, North Eastern Highlands of Ethiopia. Environ Syst Res. 2019;8(1):21.

Tesfahunegn GB. Farmers’ perception on land degradation in northern Ethiopia: implication for developing sustainable land management. Soc Sci J. 2019;56(2):268–87.

Meshesha DT, Tsunekawa A, Tsubo M, Ali SA, Haregeweyn N. Land-use change and its socio-environmental impact in Eastern Ethiopia’s highland. Reg Environ Change. 2014;14(2):757–68.

WoldeYohannes A, Cotter M, Kelboro G, Dessalegn W. Land use and land cover changes and their effects on the landscape of Abaya-Chamo Basin, Southern Ethiopia. Land. 2018;7(1):2.

Kassa H, Dondeyne S, Poesen J, Frankl A, Nyssen J. Transition from forest-based to cereal-based agricultural systems: a review of the drivers of land use change and degradation in Southwest Ethiopia. Land Degrad Dev. 2017;28(2):431–49.

Jia G, Shevliakova E, Artaxo P, Noblet-Ducoudré D, Houghton R, House J, et al. Land-climate interactions. Climate Change and Land. 2019. p. 131–247.

Hurni H, Tato K, Zeleke G. The implications of changes in population, land use, and land management for surface runoff in the upper Nile Basin Area of Ethiopia. Mt Res Dev. 2005;25(2):147-54 8.

Nyssen J, Poesen J, Gebremichael D, Vancampenhout K, D’aes M, Yihdego G, et al. Interdisciplinary on-site evaluation of stone bunds to control soil erosion on cropland in Northern Ethiopia. Soil Till Res. 2007;94(1):151–63.

Moges DM, Bhat HG. Climate change and its implications for rainfed agriculture in Ethiopia. J Water Clim Chang. 2020;12(4):1229–44.

Wubie AA. Review on the impact of climate change on crop production in Ethiopia. J Biol, Agric Healthc. 2015;5(13):103–11.

Girmay G, Moges A, Muluneh A. Assessment of current and future climate change impact on soil loss rate of Agewmariam Watershed Northern Ethiopia. Air Soil Water Res. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178622121995847.

Bishaw B. Deforestation and land degradation in the Ethiopian highlands: a strategy for physical recovery. Northeast Afr Stud. 2001;8(1):7–25.

Gashu K, Muchie Y. Rethink the interlink between land degradation and livelihood of rural communities in Chilga district, Northwest Ethiopia. J Ecol Environ. 2018;42(1):17.

Azadi H, Movahhed Moghaddam S, Mahmoudi H, Burkart S, Dadi Debela D, Teklemariam D, et al. Impacts of the land tenure system on sustainable land use in Ethiopia. 978-3-03897-878-7. 2021.

Moreda T. Contesting conventional wisdom on the links between land tenure security and land degradation: evidence from Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2018;77:75–83.

Abab SA, Senbeta F, Negash TT. The effect of land tenure institutional factors on small landholders’ sustainable land management investment: evidence from the highlands of Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2023;15(12):9150.

Legesse BA, Jefferson-Moore K, Thomas T. Impacts of land tenure and property rights on reforestation intervention in Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2018;70:494–9.

Mengesha AK, Mansberger R, Damyanovic D, Stoeglehner G. Impact of land certification on sustainable land use practices: case of Gozamin District, Ethiopia. Sustainability. 2019;11(20):5551.

Teshome A, de Graaff J, Ritsema C, Kassie M. Farmers’ perceptions about the influence of land quality, land fragmentation and tenure systems on sustainable land management in the North Western Ethiopian highlands. Land Degrad Dev. 2016;27(4):884–98.

Hishe S, Gidey E, Zenebe A, Bewket W, Lyimo J, Knight J, et al. The impacts of armed conflict on vegetation cover degradation in Tigray, northern Ethiopia. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2023.11.003.

Negash E, Birhane E, Gebrekirstos A, Gebremedhin MA, Annys S, Rannestad MM, et al. Remote sensing reveals how armed conflict regressed woody vegetation cover and ecosystem restoration efforts in Tigray (Ethiopia). Sci Remote Sens. 2023;8:100108.

Gebrekirstos A, Birhane E. The war on Tigray wiped out decades of environmental progress: how to start again: The conversation; 2023

Bossio D, Noble A, Pretty J, Penning de Vries F. Reversing land and water degradation: Trends and ‘‘bright spot’’opportunities. Stockholm International Water Institute/Comprehensive Assessment on Water Management in Agriculture Seminar, Stockholm; 2004.

Hagos F, Pender J, Gebreselassie N. Land degradation in the highlands of Tigray and strategies for sustainable land management. Socio-economics and policy research working paper. 1999.

Teketay D. Deforestation, wood famine, and environmental degradation in Ethiopia’s highland ecosystems: urgent need for action. Northeast Afr Stud. 2001;8(1):53–76.

Sonneveld BGJS. Land under pressure: the impact of water erosion on food production in Ethiopia. Netherlands: Shaker Publishing; 2002.

Cerretelli S, Poggio L, Gimona A, Yakob G, Boke S, Habte M, et al. Spatial assessment of land degradation through key ecosystem services: the role of globally available data. Sci Total Environ. 2018;628–629:539–55.

Tolessa T, Senbeta F, Kidane M. The impact of land use/land cover change on ecosystem services in the central highlands of Ethiopia. Ecosyst Serv. 2017;23:47–54.

Delelegn YT, Purahong W, Blazevic A, Yitaferu B, Wubet T, Göransson H, et al. Changes in land use alter soil quality and aggregate stability in the highlands of northern Ethiopia. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13602.

Scherr SJ, Yadav S. Land degradation in the developing world: Implications for food, agriculture, and the environment to 2020. 1996.

Coxhead I, Oygard R. Land degradation. Copenhagen Consensus. 2008.

Pistorius T, Carodenuto S, Wathum G. Implementing forest landscape restoration in Ethiopia. Forests. 2017;8(3):61.

Nyssen J, Poesen J, Lanckriet S, Jacob M, Moeyersons J, Haile M, et al. Land degradation in the Ethiopian highlands. In: Billi P, editor., et al., Landscapes and landforms of Ethiopia. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands; 2015. p. 369–85.

Hishe S, Lyimo J, Bewket W. Soil and water conservation effects on soil properties in the Middle Silluh Valley, northern Ethiopia. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2017;5(3):231–40.

Hishe S, Lyimo J, Bewket W. Effects of soil and water conservation on vegetation cover: a remote sensing based study in the Middle Suluh River Basin, northern Ethiopia. Environ Syst Res. 2017;6(1):26.

Woldearegay K, Tamene L, Mekonnen K, Kizito F, Bossio D. Fostering food security and climate resilience through integrated landscape restoration practices and rainwater harvesting/management in arid and semi-arid areas of Ethiopia. In: Leal Filho W, de Trincheria GJ, editors. Rainwater-smart agriculture in arid and semi-arid areas: fostering the use of rainwater for food security, poverty alleviation, landscape restoration and climate resilience. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 37–57.

Sinore T, Kissi E, Aticho A. The effects of biological soil conservation practices and community perception toward these practices in the Lemo District of Southern Ethiopia. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2018;6(2):123–30.

Kassawmar T, Gessesse GD, Zeleke G, Subhatu A. Assessing the soil erosion control efficiency of land management practices implemented through free community labor mobilization in Ethiopia. Int Soil Water Conserv Res. 2018;6(2):87–98.

Teketay D, Lemenih M, Bekele T, Yemshaw Y, Feleke S, Tadesse W, et al. Forest resources and challenges of sustainable forest management and conservation in Ethiopia. In: Degraded Forests in Eastern Africa. Milton Park: Routledge; 2010. p. 19–63.

Asefa DT, Oba G, Weladji RB, Colman JE. An assessment of restoration of biodiversity in degraded high mountain grazing lands in northern Ethiopia. Land Degrad Dev. 2003;14(1):25–38.

Alemayehu B, Bogale A, Wollny C, Tesfahun G. Determinants of choice of market-oriented indigenous Horo cattle production in Dano district of western Showa Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2010;42(8):1723–9.

Schmidt E. Will sustainable land management mitigate Ethiopia’s land degradation challenges? : International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2017. http://www.ifpri.org/blog/will-sustainable-land-management-mitigate-ethiopias-land-degradation-challenges. Accessed 15 June 2022

Hurni H. Concepts of sustainable land management. ITC J. 1997:210–5.

Wolka K, Sterk G, Biazin B, Negash M. Benefits, limitations and sustainability of soil and water conservation structures in Omo-Gibe basin Southwest Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2018;73:1–10.

Alemayehu T, Fisseha G. Effects of soil and water conservation practices on selected soil physico-chemical properties in Debre-Yakob Micro-Watershed, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Sci Technol. 2018;11(1):29–38.

Rossiter J, Wondie Minale M, Andarge W, Twomlow S. A communities Eden—grazing Exclosure success in Ethiopia. Int J Agric Sustain. 2017;15(5):514–26.

Sida TS, Baudron F, Kim H, Giller KE. Climate-smart agroforestry: faidherbia albida trees buffer wheat against climatic extremes in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Agric For Meteorol. 2018;248:339–47.

Alemayehu F, Taha N, Nyssen J, Girma A, Zenebe A, Behailu M, et al. The impacts of watershed management on land use and land cover dynamics in Eastern Tigray (Ethiopia). Resour Conserv Recycl. 2009;53(4):192–8.

Corbeels M, Shiferaw A, Haile M. Farmers' knowledge of soil fertility and local management strategies in Tigray, Ethiopia: IIED-Drylands Programme; 2000.

Esser K, Vågen T-G, Haile M. Soil conservation in Tigray. Ås, Norway: Agricultural University of Norway; 2002.

Alex W. Ethiopia’s Tigray Region bags gold award for greening its drylands. Toronto: Thomson Reuters Foundation; 2017.

Kassie M, Zikhali P, Pender J, Köhlin G. The economics of sustainable land management practices in the Ethiopian highlands. J Agric Econ. 2010;61(3):605–27.

Gebremedhin B, Pender J, Tesfay G. Collective action for grazing land management in crop–livestock mixed systems in the highlands of northern Ethiopia. Agric Syst. 2004;82(3):273–90.

Schmidt E, Tadesse F. The sustainable land management program in the Ethiopian highlands: an evaluation of its impact on crop production. Washington: Intl Food Policy Res Inst; 2017.

Schmidt E, Chinowsky P, Robinson S, Strzepek K. Determinants and impact of sustainable land management (SLM) investments: a systems evaluation in the Blue Nile Basin Ethiopia. Agricl Econ. 2017;48(5):613–27.

Nega B, Adenew B, Gebre SS. Current land policy issues in Ethiopia. Land Reform, Land Settl Coop. 2003;11(3):103–24.

Holden ST, Bezu S. Preferences for land sales legalization and land values in Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2016;52:410–21.

Crewett W, Korf B. Ethiopia: reforming land tenure. Rev Afr Polit Econ. 2008;35(116):203–20.

FDRE. Constitution of the federal democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Proclamation No. 1/1995. Addis Ababa: Federal Negarit Gazette; 1995.

Tura HA. Land rights and land grabbing in Oromia Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2018;70:247–55.

Tefera B, Sterk G. Land management, erosion problems and soil and water conservation in Fincha’a watershed, western Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2010;27(4):1027–37.

Ege S. Land tenure insecurity in post-certification Amhara Ethiopia. Land Use Policy. 2017;64:56–63.

Bezu S, Holden S. Demand for second-stage land certification in Ethiopia: evidence from household panel data. Land Use Policy. 2014;41:193–205.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the financial support from the Development Cooperation Instrument of the European Commission (EC), CRIS: ENV/2016/39183 and the German Federal Ministry for Development and Economic Cooperation (BMZ) for funding this study under the Project “Reversing Land Degradation in Africa through Scaling-up EverGreen Agriculture Project – component 1 (Economics of land degradation), (PN 17.2010.1-003.00)” hosted and carried out by The Economics of Land Degradation Initiative. We would also like to thank the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) for the administrative and organizational support. We acknowledge the Institute of International Education-Scholars Rescue Fund (IIE-SRF), Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management (MINA), and NORGLOBAL 2 project “Towards a climate-smart policy and management framework for conservation and use of dry forest ecosystem services and resources in Ethiopia [grant number: 303600]” for supporting the research stay of Emiru Birhane at NMBU. Moreover, we acknowledged the Rufford Foundation (grant numbers: 21680-1, 26273-2, 31671-B and 40760-D), the People’s Trust for Endangered Species and the Foundation Franklinia (grant number, 2020-15) for their financial support to Tesfay Gidey to participate in the write-up of the review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: NS, EB; Methodology: NS, EB; Literature review and analysis: NS and EB; Writing—original draft preparation: NS and EB; Writing—review and editing: NS, EB, MT, MS, MA, FT, TG, and S W. N. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors gave their informed consent to this publication and its content.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Solomon, N., Birhane, E., Tilahun, M. et al. Revitalizing Ethiopia’s highland soil degradation: a comprehensive review on land degradation and effective management interventions. Discov Sustain 5, 106 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00282-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-024-00282-7