Abstract

Underdevelopment and poverty are causes for concern, towards the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in the Global South. In most developing countries donor-funded projects through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) accompany governments’ quest to achieve development through poverty reduction initiatives. However, the sustainability of these donor-funded projects in developing minority communities remains questionable. As such, this research evaluates the sustainability of donor-funded projects in developing remote-minority Tonga communities of Zimbabwe in pursuit of the SDGs. The research adopted a descriptive survey design triangulating quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques. Ten percent (805) of the total households (8053) in four wards of Binga District (Siabuwa Ward 23, Pashu Ward 19, Kabuba Ward 17, and Kani Ward 24) were selected to participate in this study. Findings indicated that there are various projects (food aid, water and sanitation, monetary aid, and climate change resilience) undertaken by NGOs in Binga District. There was a slight change in household socio-economic development since the operation of NGOs in the district and challenges were witnessed after donor-assistance withdrawal. This resulted in the stagnancy or collapse of some projects which affected the development of the Tonga minority community. There is an inadequate understanding of the livelihoods of the poor in Binga District due to a lack of adequate needs assessments, hence the need for participatory grassroots development approaches. Lack of development in Binga District, despite the various donor-funded projects operating in the area, is an indicator that the projects are insufficient and ineffective to deal with underdevelopment in this district. The paper recommends a shift in approaches used by both NGOs and the government to ensure sustainability in donor-funded projects to develop minority communities and help the government in its efforts to attain Vision 2030 and the SDGs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Soon after independence, many African countries depended on material, financial, institutional, and technical support from the developed world to map their route towards development. The growing concern to assist in the process of rural development for Global South nations resulted in the mushrooming of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), international development agencies (IDAs), and numerous donor-funded project interventions [13, 24, 31, 36]. This NGO movement saw an intense flow in the 1990s, as a plethora of global donors supported rural development inventiveness within the African continent [5, 8]. Despite the varying statements and vision of intent, these donors commonly united on the need to reduce poverty levels, particularly for the poor, susceptible, and rural communities. International donors channelled resources either directly through local NGOs or in most cases, through government-specialised agencies by way of programs and projects [5, 14, 31, 36]. Thus, donor funding played an imperative role in this respect as it was considered as an effective channel for development in Africa.

For more than three decades, African nations have been targeted for donor-funded projects in many sectors comprising agriculture, community and social development, public health, infrastructural development and education [2, 3]. However, a lot of concerns have been noted in policy and scientific spheres despite the importance associated with donor-funded projects. For example, issues of project sustainability and impact have always been concerning [13, 27, 28, 31] as there are substantial restrictions to the capability of national governments to prolong community development. Globally, there have been various modifications in the socio-economic environment of countries, with immense increases in the degree to which national policies are embracing the system of sustainability. In 2015 world leaders agreed to combat extreme poverty, hunger, and disease through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [43]. Sustainable development strives to achieve a balance between the environment, society, and the economy. It presumes that developmental endeavours (projects in this situation) must be executed in a way that the benefits are realised by future generations [23, 44]. Restrictions on revenue-raising have appeared as an obstruction to community development and sustainability, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, international development organisations arose as vital actors specifically in interim sectorial and infrastructure project lending, with emphasis on the application of sustainability principles in community development projects and programs [5,6,7, 17].

In pursuit of measures for developmental hitches affecting the African continent, the donor community has regarded NGOs as an essential agency for empowering people thereby leading more sustainable and effective local development services than those endorsed by the state [7]. This comes from the fact that the government has been futile in catering for the well-being of its people [8, 21]. The prompt growth of NGOs in the preceding decades has been known as ‘an imperative occurrence which has impacts on the development prospects of poor people [6]. The term NGOs has been extensively debated. Some define NGOs as part of the ‘aid industry’, others as vehicles for transferring external aid, others as part of grassroots community organising, and yet others as service contractors [12, 17, 25]. However, there is substantial uncertainty on how these intentions can be accomplished practically [19]. One of the aims of NGOs as agents of change is development and it has gained a lot of attention from both the developing and developed nations. A lot of money is donated each year to alleviate poverty to achieve development, however, very little is achieved. Many Global South nations have encompassed the intervention of NGOs as an option for poverty alleviation [7]. However, the approaches used are encountering sustainability challenges hence there is a need to direct attention to what must be done to attain sustainability.

NGOs in Zimbabwe can be observed as agents to enhance the means of combatting poverty, especially in development discourse and service provision leaning towards developing tools and skills for strengthening society [7, 11, 15, 25]. In Zimbabwe, NGOs have been extensively considered as drivers of socio-economic change in several poor rural communities. However, the sustainability of donor-funded projects remains questionable considering that most communities, particularly the minority communities, remain underdeveloped even after participating in the projects. Their impact has long been interrogated by the government, as they were blamed for being ‘agents’ of Western colonialism masquerading under the ‘mask’ of development aid [27].

Zimbabwe introduced a new long-term development blueprint (Vision 2030) in a bid to achieve an Upper Middle Income Economy by 2030 [28]. To achieve this, it also introduced National Development Strategy 1 which is a 5-year medium-term plan meant to realise the country’s Vision 2030 while concurrently addressing the global ambitions of the SDGs. It is crucial to find out whether minority communities are also on the path to achieving these set goals and the country’s vision, particularly through donor-funded projects since they have been marginalised in many development sectors. Non-governmental rural development organisations have been operating in Zimbabwe for several decades [34]. However, their operation was reduced during the fast-track land reform programme in the 1990s and Economic Structural Adjustment Programs that exacerbated the economic crisis and repelled donor funding [27, 34]. The creation of the Government of National Unity in 2009 ensured economic and political stability, halting inflation and economic growth, which then attracted donor funding and the implementation of many donor-funded projects [27]. This research, therefore, considers these two periods, that is, before the operation of NGOs (1990 to 2008) and after the operation of NGOs (2009 to 2022).

Binga District is well recognised for its adverse climatic conditions making it a poverty-prone area [26, 25]. Although Binga is considered one of the poorest areas in Zimbabwe, it is endowed with natural resources like the hot springs, wild animals, water of the Zambezi River, and timber [25]. Efforts by donor organisations to empower and develop Binga rural communities are proving to be unfruitful as people’s livelihoods are showing slight or no progress despite the efforts put in place. There seems to be a missing link between the formulation and implementation of these projects and the concept of community empowerment since the projects would, from time to time, display signs of lacking sustainability, which hampers communities in their fight against poverty. As a result, there is perpetuation of poverty, starvation, and the persistence of high unemployment levels, which go unchanged and send people crossing over to neighbouring countries for better fortunes. Considering this, it will be very difficult to achieve the country’s Vision 2030 and the SDGs by 2030, particularly SDG 1 of poverty eradication, SDG 2 of ending hunger, and SDG 11 of sustainable cities and communities. It is vital to conduct a comprehensive analysis of NGO donor-funded projects in Binga District and their sustainability needs so that NGOs in this district will be in a position to support national efforts to attain the country’s Vision of becoming an Upper Middle-Income Economy as well as achieving the SDGs by 2030.

Sustainability denotes the capacity of a project to remain in operation achieving its goal for the longest time possible after withdrawal of support by the donors [37]. Project sustainability is defined as a project's sustained existence and service delivery to recipients when outside support has ended [9, 10]. From the perspective of this research, it denotes the ability of project recipients to continue operating their projects and obtaining livelihoods after the end of the financial support period from donors. The anticipation is that any intervention must yield sustainable benefits for and impacts on the people [9, 12]. Given that there are many donor-funded projects in Binga, but that poverty continues, it appears that these projects are not having a lasting effect. Thus, the researchers have questioned whether NGOs in Binga District are progressive partners in the quest for sustainable development or simply retrogressive agents masquerading as development partners. More so, if the lack of sustainability is to do with how the projects are implemented, then how best can they be implemented to ensure sustainability? To try and answer these questions, the following objectives guided the research (1) examine the operational thrust of NGOs and donor-funded projects in Binga District, (2) assess the level of socio-economic development by households before and after the operation of NGO projects in Binga District, and (3) evaluate the sustainability of donor-funded projects in achieving socio-economic development by households in Binga District.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study area

Binga District is situated 445 km from Bulawayo, the second largest city of Zimbabwe as shown in Fig. 1. Its outlying areas further stretch a maximum of 250 km from Tyuunga to Kabuba ward in Lusulu [26, 33]. Binga District is located in the western Zambezi Valley. To the west, it is bound by Lake Kariba, with Zambia on the other side of the lake [33, 40]. The district borders Hurungwe District to the north, Gokwe North and South to the east, Lupane to the south-east, and Hwange to the south. According to the Zimbabwe Population Census of 2022, the district is made up of twenty-five wards with a total population of 159,982 (87,589 females and 72,393 males). Binga forms the border of Zimbabwe and Zambia in the Northern part of the country. In terms of human development, Binga is ranked the third least developed of all districts in Zimbabwe and this makes it a targeted district by many NGOs. Several NGOs operate in the district which includes Save the Children (UK) carrying out emergency food aid and water projects and Caritas provides supplementary feeding in Binga. The district suffers from two major constraints to development. Firstly, most of the land falls under regions 4 and 5 with low rainfall meaning that it is more suited to extensive livestock rearing, and agriculture production is typically quite low. Secondly, the area is physically remote and far from major markets hence the exchange of livestock for grain has been a coping strategy used by an increasing number of households in Binga District [38]. This physical remoteness has been a major obstacle to reaching the poorest wards for assistance by both government agencies and NGOs.

2.2 Methods and materials

The research employed the descriptive survey design, triangulating both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. This design was chosen because it aims to precisely describe a research problem and this assisted in investigating the background of the research problem. More so, this design allowed the researchers to utilise varied techniques that aided the research procedure and helped to explore the research problem in-depth, past the surface level to provide a comprehensive description of the research subject. Considering that this research was more concerned with achieving sustainability in minority communities and synchronising this with the national development agenda, which is a real-life situation, this design was the appropriate one to employ.

The research targeted all 21 wards in Binga District. The wards were divided into 4 clusters (Binga North, Binga South, Binga East and Binga West), and from each cluster, one ward was purposively selected to participate in the study. Purposive sampling was used in selecting the wards targeting those that had many donor-funded projects operating in them. As a result, Siabuwa Ward 23, Pashu Ward 19, Kabuba Ward 17 and Kani Ward 24 were purposively selected to participate in the research. In these 4 selected wards, household heads were then targeted as questionnaire respondents. The target population for the households was 8053 (1844 for Ward 23, 1338 for Ward 19, 2934 for Ward 17, and 1937 for Ward 24). From this, 10% of the total households (805) were selected to participate in the study. Simple random sampling was used to select the 10% sample size of household heads per ward, which resulted in 805 households being selected to participate in the research (Table 1).

The research also targeted key informants for interviews who were purposively selected and these included Monitoring and Evaluating Officers of the NGOs operating in the selected wards, Community Development Officer for Binga Rural District Council and ARDAS (Agricultural and Rural Development Advisory Services) Officers of each ward. Purposive or judgemental sampling was then adopted to select interviewees. This sampling was used to deliberately select individuals that were best suited to provide information to address the research objectives by virtue of their positions in the study area.

Data were assembled from household heads using questionnaires which were personally administered by the researchers for 2 weeks in the field. This was done to clearly explain the requirements of the questions to the respondents since the research was conducted in a marginalised rural setup with high rates of illiteracy. First, the researchers sought approval to conduct the research from the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Binga RDC. After the permission was granted the researchers then visited the selected wards to seek permission to administer questionnaires from the councillors of the wards. Verbal consent was also sought from the household heads who were randomly sampled to participate in the study. In-depth interviews were then conducted with the key informants who first gave their consent by signing informed consent forms as evidence that they had accepted to participate.

Quantitative data was analysed and presented using Microsoft Excel 2013 and SPSS 16.0 analytical tools. Qualitative data was analysed and presented using thematic analysis following the objectives of the study.

2.3 Limitations of the study

The research solely depended on recall information of participants about the level of socio-economic development of the participants before and after the operation of NGO donor-funded projects in the community to measure sustainability. This had limitations in that there was no method of assessment to tell if the information provided by participants was true or false. However, this limitation was countered by conducting in-depth interviews with officials who had access to records on households’ status of development.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 The operational thrust of NGOs and donor-funded projects in Binga District

Many NGOs have operated and are still operating in Binga District. The Community Development Officer (CDO) from Binga RDC indicated that more than 10 NGOs have implemented their projects in all the wards of Binga District. Amongst these, the ones which were identified included the ADRA, Mvuramanzi, Caritas, Action Aid, World Vision, UNICEF, Gayka Japan, Dabane Trust, Christian Care, and Campaign for Female Education (CAMFED), Basilizwi Trust, Kulima Mbobumi Training Centre (KMTC) and Save the Children. Operating periods of some of the NGOs like Caritas and Gayka Japan had lapsed soon after they implemented the projects in the community. These results resonate well with what was revealed [32] that Save the Children, Caritas, and CAMFED were the popularly known NGOs in Binga District due to their long presence, followed by, KMTC, Mvuramanzi, Basilwizi, LEAD, MAC, Christian Care, UNICEF, SNV, and Capernaum Trust. This indicates that there is a large influx of donor-funded projects in the district. With this concentration of NGOs in Binga District, one would expect to perceive a change in terms of community development considering both at the national and global levels, that there are efforts to try and meet targets of Vision 2030 and SDG respectively.

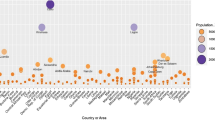

The questionnaire respondents indicated that they were beneficiaries of the projects that were implemented by one or more NGOs in Binga District. They were then asked to mention the type of projects that were implemented by NGOs and the findings are shown in Fig. 2.

Food-related projects were the ones that were largely implemented by NGOs in the sampled wards as shown by 100% of respondents (Fig. 2). There were no fish or campfire-related projects that were being funded by NGOs in all the sampled wards. Fish and Campfire projects were being run by the local government. Cash income transfer projects (Monetary) were only being implemented in one ward (Ward 24-Binga Centre) as indicated by a few respondents (21%) in Fig. 2. The findings presented in Fig. 2 show that the majority of projects were mainly food, water and sanitation/hygiene, and climate change resilience projects.

NGOs that dealt with water and sanitation were Mvuramanzi, United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), and Caritas. Basilwizi Trust and CAMFED participated in the health sector. UNICEF and Save the Children provided social amenities. Civic protection issues were dealt with by Basilwizi and CAMFED, particularly in child protection. NGOs such as Christian Care, Caritas, Kulima Mbobumi Training Centre, Save the Children and Action Aid were involved in food security. NGOs that were involved in the education sector include Save the Children, CAMFED, UNICEF, Capernaum Trust, and Basilwizi Trust.

The CDO supported by the ARDAS officers in all the sampled wards revealed that almost all the donor-funded projects were initiated soon after 2009. They explained that due to the effects of the Land Reform Programme in the 2000s, foreign investors and donor funders withdrew their assistance in the country and this was followed by a period of economic recession which did not favour any donor funding projects. When Unity Government came into power in 2009 there was an economic boost in the country which created an economic environment that favoured foreign investors and donor funders. As a result, there was a resurgence of donor-funded projects mushrooming in the country with most of them targeting specifically minority communities where development was still very low. This was also the period when donor-funded projects in Binga District were initiated and the periods that followed later. Considering micro and macro-economic and environmental policies one would expect to see a change in the operation of donor-funded projects for them to remain relevant to society. Hence, in this case, the donor-funded projects are supposed to function in line with the targets of the country’s national Vision 2030 and the SDGs.

3.2 Level of socio-economic development by households before and after the commencement of NGOs projects

3.2.1 Occupation of households before and after engaging in donor-funded projects

Figure 3 shows that the respondents (100%) depended on farming for survival before the operation of donor-funded projects and this scenario did not change after the implementation of donor-funded projects. However, there was a slight increase in proportion amongst those who were occupied as fishermen, informal cross-border traders, and those in formal employment. Cross-border activity is also relatively high due to the closeness of the district to neighbouring Zambia.

The high dependence on farming as an occupation for survival remains a challenge which indicates that there is no innovation in coming up with strategies to harness the natural resources for the benefit or development of the community. This is because the district is found in region 4 and 5 of the natural agro-ecological regions of Zimbabwe that receives low rainfall which makes it very difficult for yields harvest to sustain the community members throughout the year. Mutale [32] argues that the greater part of the district suffers a lot from food deficit as a result of low rainfall, compounded by partial arable land and patch arable soils. These climatic conditions of high temperatures and little rainfall coupled with poor soils make cropping a precarious venture [10] hence the difficulties of prolonged food shortages. A study undertaken by [45] revealed a higher percentage of food-insecure households in Binga compared to other districts in Matabeleland North province. This means donor-funded projects being implemented are not addressing the root cause of food insecurity and poverty and some are not relevant to the community given its environmental constraints. If this is not addressed, the hope of achieving the Vision 2030 goal of reducing the poverty rate to under 25% of the population will remain elusive.

NGOs did not implement any projects related to fishing and the increase in the proportion of those practising it in Fig. 3 was only attributed to households getting income from donor-funded projects which they then used to join the cooperatives for fishing. Respondents explained that fishing is mainly done in Lake Kariba and only those with permits were allowed to fish. The fishing permits were not provided to individuals but to cooperatives formed by the residents in the community and the majority to companies. The cooperative is expected to purchase a permit for USD$300, which is renewed quarterly, and pay USD$36 subscriptions to the Binga District Council. The majority of the community members could not afford this requirement to join cooperatives hence only a few were practising farming. The respondents in the cooperatives group pointed out that the income from fishing is not much considering that they had many expenses such as subscriptions, purchasing of nets, salt for drying fish, manpower and security at fishing points. More so, they have to share the few profits in the cooperative group.

3.2.2 Type of livestock owned before and after engaging in donor-funded projects

Figure 4 shows an increase in the proportion of respondents who owned cattle (85–92%), goats (68–87%) and chickens (92–98%) after the operation of donor-funded projects. The major reason for this improvement is that there is an NGO named Action Aid which has boosted and increased livestock production in the district. It started operating in the district in 2016 centred on disaster risk reduction focusing on crop and livestock production. Action Aid provides sub-aqua training, livestock feed preparation or formulation training from locally available inputs.

Action Aid has two projects (African Breeders Society and Afro-soft) on the ground which assist the community in livestock production. African Breeders Society trains the community members on competence in livestock breeding, especially cattle, and goats. This is important as it focuses on capacity building so that after the withdrawal of the donor assistance the community members will still be able to continue practising livestock production using the knowledge from training sessions. Afro-soft is a project for monitoring cases of diseases, hazards, and the number of dry spells in the district. It aggregates all the information that affects the farmer for the whole district and submits it to the Zimbabwe Resilience Building Fund (ZRBF) and the Government of Zimbabwe for response purposes. This is quite critical for the district considering that [1, 18] reports revealed that droughts in the province resulted in the death of livestock; prevalent livestock illnesses, predominantly foot and mouth; tick-borne diseases; anthrax; and lumpy skin. However, it is also vital for the locals to be trained in monitoring these cases and gathering information on their own so that when the NGOs withdraw their assistance, this practice will not end but continue long after the NGOs are gone. This will contribute positively to the country’s efforts of meeting the Vision 2030 targets of ensuring a stable macro-economic environment sustained by productivity levels and reducing the rate of poverty to below 25% given that a study by [45] revealed that livestock production contributes greatly to food security for Binga District.

The ARDAS Officer explained that Action Aid also established two Crop and Livestock Improvement Centres (CLIC) which are strategically positioned, one in Binga North at Siabuwa and the other one in Binga South at Lusulu. These are centres of excellence with feedlots in fenced areas for goats and they are also learning centres where farmers go and learn new techniques for implementation at their farms. At these centres, they do trials, horticulture, and seed banks for traditional small grains. For livestock, they have incubators for chickens and goats, and farmers take their does (or nannies) there for cross-insemination with the improved bucks at the centres. Cows are also taken for mating with improved bull breeds. Both cows and does are left at the centres for 21 days to guarantee successful cross-insemination.

The respondents indicated that they witnessed an increase in livestock production through these donor-funded projects under Action Aid. Considering that Binga District lies in an area that receives little and unreliable rainfall the community has largely depended on livestock production to meet some of its needs. Respondents indicated that they would sell one to four cattle to cater for clinic fees, household food security, transport cost to distant health facilities, and school fees. Interviews with key informants discovered that cattle are an important asset and they sell them during times of shocks and stress for household support. The interviewees explained that there is one existing alternative for making a living throughout the drought periods, which is livestock sales. Trading livestock with the grain is a coping approach used by many households in Binga during difficult agricultural years. A study by [45] argues that in Binga District the ownership of livestock, mainly cattle, is measured as a pointer of kept wealth and so a status emblem; and goats and chicken are pointers of available cash. It should be stressed, however, that this is not a sustainable method of acquiring food for households with small livestock herds because the resources and time required to re-build small herds are not calculated in months but years. Hence, this calls for NGOs to extend their funding to other projects like fishing since Binga is naturally endowed with fishery resources, to diversify the livelihood survival options of the community. This will enhance the standards of living of Binga residents while at the same time helping the nation in meeting its Vision 2030 target of high-quality life for all people with fewer inequalities.

3.2.3 Main source of energy for cooking before and after engaging in donor-funded projects

Figure 5 shows a very slight improvement in the sources of energy used by the households after the operation of donor-funded projects. Unfortunately, there are no donor-funded projects under sources of energy in the district and for those few respondents who indicated that they were now using electricity (5%), paraffin (5%) and gas (5%) they were among those residing in Binga Town (ward 24) who were receiving assistance in the form of money from World Vision. Through this money, they managed to purchase gas, paraffin and buy electricity for cooking. Firewood has been the major source of energy for cooking before and after the operation of NGOs. This is against the country’s policies and plans such as the National Climate Response Strategy and the National Renewable Energy Policy, which are meant to lessen carbon emissions and reduce the adverse effects of climate change. Zimbabwe is a signatory to the Paris Agreement and has assured to decrease its greenhouse emissions by 33% by 2030 but this target can be difficult to meet with heavy dependence on firewood. This may hinder the country’s Vision 2030 goal of accelerating the number of households with access to electricity from 52.2% (2017) to over 72% by 2030. Consequently, it will affect the achievement of SDG 11 and 13 of sustainable cities and communities; and climate action respectively.

3.2.4 Main source of water before and after engaging in donor-funded projects

The majority of respondents (36%) had unprotected wells as their main source of water before engaging in donor-funded projects, 24% used river/lake water, 15% used rainwater and boreholes and only 10% had protected wells as their main source of water (Fig. 5). This shows that the situation in Binga District on sources of water before the operation of donor-funded projects was quite dire as very few respondents had access to safe/clean water sources. The participants in Kabuba ward highlighted that their serious threat to development was the lack of clean water. In 2015 the entire ward had two boreholes only that were 14 km to and from other homesteads [25]. Throughout the dry season, the livestock would only have access to drinking water thrice a week. More so, the residents would make timetables for bathing and sometimes utensils would rarely get cleaned after utilising them, which posed grave health hazards [25]. In Pashu Ward 19, respondents revealed that although they had adequate water, it was unclean since they depended on unprotected wells.

After the engagement of NGOs in the district there was an improvement in the percentage of respondents who depended on borehole water as their main source of water from 15 to 75% (Fig. 6). The reason for this could be that many NGOs (Gayka Japan, Dabane Trust, ADRA, Save the Children and Mvuramanzi) that operated in Binga District had drilled boreholes. However, there was no change in the proportion of those who depended on protected wells meaning that the NGOs did not implement any project on protected wells. On a positive note, the proportion of those who depended on unsafe water sources decreased from 10 to 36% for unprotected wells and from 15 to 24% for rivers/lakes (Fig. 5). Those who solely depended on rainwater as their main source reduced to zero per cent because of unreliable rainfall as a result of seasonal changes and climate change.

Despite the increase in the proportion of those who indicated they depended on borehole water after the operation of donor-funded projects, some respondents (56%) together with the CDO explained that the Water and Sanitation programme, which was initiated by Save the Children, was not executed to projected stages because the well pumps and boreholes broke down and were not mended. This calls for training and capacity building of community members by NGOs on borehole rehabilitation for the borehole projects to continue functioning after donor assistance withdrawal. Women and children continue to travel long distances, of more than a km, in search of water or, as an alternative, end up using contaminated sources near their homes. It was also revealed that some boreholes were not perennial due to low water tables. One of the Vision 2030 goals is to achieve universal access to clean sources of water to 81% of the population and this corresponds with the SDG 6 of clean water and sanitation. This calls for the NGOs to ensure sustainability and efficacy in their projects towards these goals.

3.2.5 Type of toilets mainly used before and after engaging in donor-funded projects

Figure 7 shows a general improvement in the types of toilets mainly used after the operation of donor-funded projects in Binga District. The proportion of respondents who used covered pit latrines greatly increased from 20 to 51%. There was a reduction in the proportion of those who relied mainly on public latrines and bush type of toilets from 42 to 30% and 38% to 14% respectively (Fig. 7). The small proportion (5%) that were using the flush toilet after the operation of donor-funded projects were respondents from Binga town Centre (Ward 24).

The CDO concurred with these findings from the questionnaire survey and was quoted saying:

They were various programmes under NGOs like Save the Children and Mvuramanzi that constructed latrines for vulnerable communities; at the same time, communities were capacitated on behavioural change to create demand for self-funded latrine construction.

It was also mentioned that the NGOs supported the training of builders who were given start-up kits and helped in the building of self-funded latrines. This explains why the proportion of the respondents who used privately covered pit latrines did not increase to above 50% since the majority of people could not afford to self-fund the construction of pit latrines in their households. Interviews and observations revealed that toilet construction projects were successfully implemented in schools but several unfinished toilets were left in the communities as residents failed to source funds to complete the toilets left at slab level through NGO support. These findings resonate with those revealed by [18] that in 2018, Matabeleland North province, where Binga District is located, had the highest percentage of households that exercised open defecation in Zimbabwe. This shows that there is a lack of sustainability in the donor-funded projects to develop the communities as there is a lack of continuity of projects after funding withdrawal.

3.3 Sustainability of donor-funded projects in achieving socio-economic development in Binga District in line with the country’s Vision 2030

3.3.1 Community involvement in implemented projects

Only 3% of the respondents indicated that they were part of the decision-making of the projects implemented by NGOs in Binga (Fig. 8). However, when asked further they explained that they only participated in decision-making in terms of where in the district can the projects be implemented and not necessarily on the type of projects to implement. 20% of the respondents indicated that they took part in the management of the projects. These respondents were members of the committees that were established to govern the running of the projects. Many respondents (77%) indicated that they were only involved by being informed of the projects implemented by the NGOs. The CDO explained that the major challenge to the active involvement of locals in donor-funded projects is that occasionally these programmes are determined by the funders. When the NGOs get financial aid the donor stipulates what the NGO must do with the money and because the donors do not mingle with the service users, sometimes there is a misunderstanding on what precisely the needs of the poor are. The ARDAS Officer added that the funders assume that poverty is similar all over Zimbabwe. Although involvement can be an empowering process where recipients can contribute to managerial processes of the development route, NGOs appear to embrace the debate on involvement and empowerment but flop in practice to walk the talk [6, 17, 28]. This contradicts the target of the National Development Strategy 1 under Vision 2030 of decentralisation and devolution of government services with increased involvement of citizens when developing their places of residence.

In most cases the challenge of not acting together with the beneficiaries, before executing a programme, is a contributor to the unsustainability of donor-funded projects; the issue of poverty and underdevelopment in Binga District. Similarly, a study undertaken in India attested that there was a prominent lack of public involvement in NGO programmes [41]. Excluding the community members at the initiation of projects may mean that their challenges and problems in terms of development remain unclear and unsolved to some degree. Thus, active participation of the poor rural communities is pertinent and must be prioritised to avoid the unsustainability of donor-funded projects. For instance, when they advocated for the self-funded construction of toilets there was an element that people were forced to comply even though they did not have a reliable source of funds to complete the toilets hence their problems remained unsolved and the project remained uncompleted. Another criticism is that their projects lack sustainability [4, 17]. Sustainability is considered project ownership way after the end of the project funding. Denoting that donor-funded projects must have the capability to sustain themselves and last long after the end of the programme. Hence, the robust involvement of beneficiaries in the decision-making processes of donor-funded projects is pertinent. Banks et al. [6] and Dube [17] stipulates that there must be an exchange of power where NGOs seize to be service providers, doing things for people, but become facilitators which is more sustainable. NGOs can achieve this by revamping themselves, prioritising communities, and giving power to the community over project design, planning and implementation. This will contribute towards sustainable structural change that does not deal with symptoms but with root causes of poverty. Participation results in development that is more demand–driven, bottom–up, rather than top–down [17, 20].

3.3.2 Challenges faced by community members from projects handed over for community ownership

The majority of respondents (82%) indicated lack of finance as the major challenge they faced after the withdrawal of donor assistance in some implemented projects (Fig. 9). Leadership challenges were pointed out by 74% of respondents, 67% indicated equipment challenges and only 15% mentioned participation challenges in running projects after handover by NGOs. The respondents explained that it was difficult to run a project which used to gain funding from external sources when you do not have the capacity to raise your own funds as a community. These findings are similar to what was discovered by Martens [26] in a study conducted in Binga that although NGOs can be honoured in bringing projects, like chicken projects, community gardens, cattle fattening and borehole drilling, that cater for the welfare of communities they only function during the presence of funder organisations and benefactors. Soon after the involved NGOs left, these projects crumbled. The CDO supported this by explaining that this was the major reason why many community members in Binga District were not participating in fisheries projects. Many fishing cooperatives failed to operate due to challenges of finance and this was also experienced in donor-funded projects after their withdrawal. The financial challenges led to challenges in accessing equipment to run or continue with the projects. Those who indicated leadership as a challenge explained that the leadership training provided to them was not enough and was done in a short period when the NGOs were already mapping their way out. In most cases when they encounter challenges, they have nowhere to turn to for assistance which ends up affecting the smooth running of the projects.

3.3.3 Sustenance of implemented projects without complete reliance on donor funding

Many participants (48%) indicated that the projects implemented by NGOs are not sustainable, 44% of the participants pointed out that they are partially sustainable and only 8% expressed their satisfaction about the projects saying they are sustainable (Fig. 10). The major explanation provided by those who perceived projects by NGOs as unsustainable was that the majority of the projects were not addressing their needs. They indicated that there is a need for developmental strategies that are sustainable and that can empower the locals in running the projects in order to do away with the dependency syndrome on donor aid. These findings resonate with what was revealed by Mago et al. [25] that NGOs execute some of their projects without seeking the opinions of community members, thus the needs of the poor remain not addressed Some of the wards in the district were not part of the sample surveys meaning NGOs depended on survey findings from other areas a ‘one size fits all’ method not looking at the variances in community needs. This suggests that NGOs carry out the projects to safeguard their contracts and to impress the benefactor to attract more aid without necessarily focusing on the sustainability of the projects in developing the rural communities.

Respondents mentioned that sometimes donor-funded projects benefit the community but they only function under the supervision of NGOs and their continuity is affected by NGO withdrawal. The participants in Kabuba ward highlighted that the distribution programme of farm inputs under KMTC (Kulima Mbobumi Training Center), was a good project, however, the challenge was that it only benefitted a small proportion of people and was not sustainable. More so, they argued that if poverty and community development were being dealt with by NGOs in Binga, considering when they started operating in the district, communities could long have developed and become independent by now. They described a scenario of the fertiliser distribution programme which they say does not address their needs. They explained that KMTC, Action Aid and ADRA have a programme for fertiliser distribution in the district every year including in the most arid wards like Siachilaba Ward. People consider fertiliser to be of less importance to them because of the perpetual disappointment of poor harvests worsened by climate change and variability, and hence most community members sell fertiliser in neighbouring Zambia.

The participants (92%) indicated that there is a relationship between dependency syndrome and NGO approaches in the district. Food distributions that are continuous result in them being reluctant and waiting for handouts from NGOs every time which continues to derail them in developing their community. The Community Development Officer of Binga District believes that the intensifying and spreading of poverty in Binga together with the lack of development is a result of the approaches used by NGOs. He explained that NGOs utilised the same approach to alleviate poverty and these are not greatly improving the lives of people in a sustainable manner. The community of Binga, although underdeveloped, are able to contribute to their own development if their strengths are identified, exploited and sharpened. A study conducted by Mutale [32] revealed that food aid in Binga District failed to contribute to sustainable food security although it was vital in dealing with urgent food needs. This scenario prompts the policymakers, government and NGOs to rethink if it will be possible to meet the national Vision 2030 goal of reducing the poverty rate to under 25% of the population and consequently achieve the SDGs 1 and 2 of reducing poverty, ending hunger and achieving food security respectively.

Studies carried out by [4, 17] describe case studies of how NGOs are undergoing sustainability problems in Latin America and Ghana as a result of dependence on donor aid, fluctuating donor primacies causing donors to pull out and premature ending of projects. Questionnaire surveys and interviews revealed that there was no prior assessment that was done during allocations of free handouts (food and seed) to evade the promotion of dependency. The exercise weakened the coping capabilities of the community and its skills to manage the prevalent hazards and develop their community. These results are consistent with investigations by [25, 32, 33] that both the nature and distribution of aid are linked to particular policies hindering significant development. For instance, the International Monetary Fund policy on the Economic Structural Adjustment Programme in Zimbabwe of 1990, has always been blamed as the major contributor to hardships experienced by Zimbabwean rural communities.

Binga is rich in natural resources like the great Lake Kariba on the mighty Zambezi River hot springs, Binga sand beach, Chizarira and Chete forests among others, however, the community members do not have knowledge on how to use these resources for them to be independent as a result they continue to be reliant on NGOs. The other challenge is that some of the natural resources, like the Zambezi River, forest reserves and wildlife are governed by government policy, and not utilised for local but national interests [25]. This lack of self-governance by the community poses a challenge for the community members to deal with other problems, affecting their way of living and building resilience. This explains why the district continues to lack development despite the implementation of various donor-funded projects.

All the key informants (100%) explained that the reason why there is no notable development in Binga District since the engagement of various NGOs in the district is that the NGOs are addressing the symptoms and not the root causes of poverty. Furthermore, it was postulated that NGOs must comprehend the history and root causes of poverty in Binga for them to be able to come up with sustainable projects that can develop the district. Most NGOs operating in Binga District fail to stretch out to the poorest in the community because of the inaccessibility of some villages where the poor reside, failure to do home visits to the households with special needs and having their offices centralised far from the service users. Based on the findings of this research, the authors developed an approach (Fig. 11) which can be utilised by NGOs operating in minority communities like Binga District in Zimbabwe.

Figure 11 provides an approach that can be utilised by NGOs in coming up with projects for developing rural minority communities. The framework is informed by the fact that most of the donor-funded projects implemented in rural communities of Zimbabwe have not addressed the root causes of underdevelopment hence the continued unsustainability of such projects. Before bringing in projects to any community NGOs must first use the grassroots approach whereby they work hand in hand with community members and district representatives, such as the Agriculture Extension Officer, Community Development Officer and chiefs or traditional leaders to do a needs assessment. This will help to collect relevant information that portrays the status of each community and its needs which better informs capacity-building techniques based on the resources, and capital available in the community. This will enable NGOs to come up with projects that are relevant in addressing each community’s needs to ensure development and sustainability are achieved and also foster community ownership of the proposed projects. This will also facilitate decentralisation and devolution of government services through improved involvement of community members in the development of their places of residence which is an aim of the National Vision 2030.

Some parts of the Binga District communities are inaccessible which makes NGOs avoid them although they are in dire need of development. A study by Guzura et al. [19] argue that the mapping survey to discover the need of the community is the omitted tie with several NGOs working in Binga. So by using this grassroots approach, it will be possible for those areas to be included in the development projects. This will also help to solve the limitation discovered by Mpofu et al. [30] in Zimbabwe that NGOs come to Zimbabwe with prearranged programmes and provide conditions in the delivery of aid and their commendations on development can easily be prejudiced towards false anticipations, their limited understanding of their home countries, or adopted from the practices of few countries.

Community acceptance through volunteerism and participation is a fundamental aspect that pushes donor-funded projects to achieve sustainability. This is because community engagement approaches are employed when the project is initiated using a grassroots design that assists in minimising dependency on the funding agencies at the community level and creating a sense of ownership [42]. For instance, Binga District is naturally endowed with fishing resources and it was revealed that the community is interested in fishing for survival but the procedure to get access to fishing permits was not favourable to the community members hence many private companies had access to the permits at the expense of the local members. If these community members were involved in needs assessment and project design, they will have the opportunity to air their views so that a way forward can be made to ensure their maximum inclusion and benefit in the natural resources in their district.

The community members will have adequate knowledge of the projects to be implemented and their role in ensuring their continuity through this grassroots approach. The uncertainties of the responsibilities and roles of community stakeholders, in the implementation of projects that are donor funded, result in poor performance of the assigned intervention [22, 35, 39]. Working with the community at the grassroots level makes it easy to execute the project within the available community resources and also paves the way for capacity-building training in areas where the community members and local stakeholders will be lacking. The human, intellectual, and material resources of the community will be tapped into with the recognition that these resources are vital for the success of the project through the grassroots approach. Recipients are anticipated to remain operating after initial support (sustainability) and feedback is expected to be provided in the plan of impending donor-funded projects which operate within demarcated institutional and socio-economic contexts. This will counter the challenge indicated by [30] and [16] that NGO innovation is a rare phenomenon due to the highest levels of tight funding control thrown by donors upon NGOs and as a result NGO performance is not measured in terms of their responsiveness to the needs of the beneficiaries but compliance with donor priorities. A study by Chepkemoi et al. [9] argues that community ownership of donor-funded projects through the involvement of district representatives and the commitment of beneficiaries is a consistent approach towards attaining sustainability of the projects.

The NGOs in this grassroots approach process are expected to play the role of a facilitator and when there is a need provide training to the community members so that they are equipped with knowledge on how to run the projects after the withdrawal of donor funders. NGOs need to engage the unskilled local workers and equip them with the knowledge thus offsetting extra funds to remunerate newly engaged staff. More so, the local workers can motivate community-wide acceptance of the project nurturing community ownership in the process. More so the local government must ensure that its policies are operation-friendly so that the funded projects do not lose priority before the community members who are originally intended to benefit from them. Broader socio-political factors are external inhibitors that can obstruct the sustainability of donor-funded projects beyond their funding life cycle. If the beneficiaries of a donor-funded project, consider that the project is of no benefit to them it can be difficult to ensure its success and continuity. Since the government of Zimbabwe already implemented the National Development Strategy 1 towards Vision 2030 where one of its aims is devolution and decentralisation of government services, the local government of Binga District and other rural areas must create operation-friendly policies that advocate for the participation of people in the development of their communities. This is because the failure of socio-political factors to provide context-based support can influence a lack of financial mentoring, leadership, training, and accountability.

4 Conclusion

Different types of projects have been implemented in Binga District to assist in developing and alleviating poverty in the community. Some projects have yielded impactful results, especially those that focused on livestock feeding, breeding, and production. This has contributed positively towards the achievement of the SDGs 1 and 2 of alleviating poverty and ending hunger. However, other projects were not completed successfully such that their contribution in terms of development and sustainability were not positively felt. It was also noted that there remains a challenge in running the projects after the withdrawal of donor funding and this affects the sustainability of the donor-funded projects and the achievement of the SDGs 1 and 2 respectively. NGOs that operate in Binga concentrate much on implementing relief aid projects which propagate dependency syndrome amongst the community members and this has resulted in a continued lack of development and poverty in the area which has negative implications for the achievement of the SDGs. This scenario has made the NGOs continue to be relevant operating in this rural community in the name of trying to address rural poverty and developmental issues. Poverty alleviation and its ultimate elimination is an important development aspect that can help communities to become self-sufficient and resilient against shocks and stressors. Since the SDGs are intertwined, the achievement of SDG1 of poverty alleviation will result in the achievement of almost all the SDGs. This calls for community capacitation and empowerment in running projects after donor funders are gone.

Though they attempt to fight against poverty, NGOs’ approaches appear to lack the concept of sustainability in many rural minority communities since they encourage a dependency syndrome. The widespread and expanding poverty in these areas currently being assisted by NGOs makes the approaches to be problematic. After an inquiry into NGOs’ development attempts in Binga, this research commends a change in strategy by NGOs in order to progress in their poverty reduction approaches by concentrating on the sustainability of their interventions through capacity building, training, and empowerment of community members in project implementation. The government of Zimbabwe can provide a favourable environment for NGOs to provide them with sufficient political economy space to plan and execute effective poverty alleviation and developmental approaches that are sustainable. This will greatly help in achieving the SDGs 1 and 2 of alleviating poverty and ending hunger since it is in these minority communities where poverty is rampant.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Agricultural Sector Survey. The state of Zimbabwe’s agricultural sector survey 2019. Harare; 2019.

Agba AM, Akpanudoedehe JJ, Stephen O. Financing poverty reduction programmes in rural areas of Nigeria: the role of non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Int J Democrat Develop Stud (IJDDS). 2014;2(1):1–16.

Amofah S, Agyare L. Poverty alleviation approaches of development NGOs in Ghana: application of the basic needs approach. Cogent Soc Sci. 2022;8(1):2063472.

Appe S. Reflections on sustainability and resilience in the NGO Sector. Adm Theory Praxis. 2019;41(3):307–17.

Ayoo C. Poverty reduction strategies in developing countries. Rural Develop-Edu, Sustain, Multifunction. 2022. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.101472

Banks N, Hulme D, Edwards M. NGOs, states, and donors revisited: still too close for comfort? World Dev. 2015;66:707–18.

Bassey N. Contribution by the NGOs Major Group Sector on Africa and Sustainable Development. United Nations, New York Working Paper No 3. 2008.

Bratton M. Non-Governmental Organizations in Africa: can they influence public policy?". Dev Chang. 1994;21:87–118.

Chepkemoi YE, Kisimbii JM. Determinants of the sustainability of donor-funded poverty reduction programs in non-governmental organizations in Mombasa County, Kenya. Int Acad J Inf Sci Project Manag. 2021;3(7):18–42.

Chiduzha C. On farm evaluation of sorghum (BiColor L.) Varieties in the Sebungwe Region of Zimbabwe. Harare: University of Zimbabwe; 1987.

Chirisa I, Maphosa E, Matamanda AR, Mandaza-Tsoriyo WW, Chatiza K. Constitutional knowledge, rights-based development, and citizenship in Zimbabwe, research anthology on citizen engagement and activism for social change. 2022, 1039–1055.https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-3706-3.

Chizimba M. The sustainability of donor funded projects in Malawi. Rome: MCSER-CEMAS-Sapienza University of Rome; 2013. p. 86.

Chowdhooree I. External interventions for enhancing community resilience: an overview of planning paradigms, external interventions for disaster risk reduction. 2020, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4948-9.

Davis JM, Swiss L. Need, merit, self-interest or convenience? Exploring aid allocation motives of grassroots international NGOs. J Int Dev. 2020;32(8):1324–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3505.

Devereux S, Kapingidza S. External donors and social protection in Africa: a case study of Zimbabwe. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex; 2020.

DOCHAS. A wave of change: how Irish NGOs will sink or swim, a discussion paper on the future roles and relevance of Ireland’s Development NGOs. 2008. http://www.dochas.ie. Accessed 3 Sep 2022.

Dube K. A review of the strategies used by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) use to reduce vulnerability to poverty in Zimbabwe. Afr J Soc Work. 2021;11(6):371–8.

FEWS NET. Zimbabwe food security outlook, June 2019 to January 2020. Harare. 2019.

Guzura T, Tshuma V. The rural development false start in Zimbabwe: a dichotomous composition of theory and practice informing community based planning in Binga District. Afr Asian J Soc Sci. 2016;7(1):1–9.

Hunt A, Samman E. Women’s economic empowerment: navigating enablers and constraints. Overseas Development Institute Research Report. London; 2016.

Ibrahim U, Wan-Puteh SE. An overview of civil society organizations’ roles in health project sustainability in Bauchi State, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;2018:30.

Kilewo EG, Frumence G. Factors that hinder community participation in developing and implementing comprehensive council health plans in Manyoni District, Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:26461.

Krantz L. The sustainable livelihood approach to poverty reduction. SIDA. 2001;44:1–38.

Lewis D, Schuller M. Engagements with a productively unstable category: anthropologists and non-governmental organizations. Curr Anthropol. 2017;58(5):634–51. https://doi.org/10.1086/693897.

Mago S, Nyathi D, Hofisi C. Non-governmental organisations and rural poverty reduction strategies in Zimbabwe: a case of Binga Rural District. J Gov Regul. 2015;4(4):59–68.

Martens J. Complexities of rural development in globalised environment: lessons from Binga District Zimbabwe. Johannesburg: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation; 2010.

Matsa M, Dzawanda B. Dependency syndrome by communities or insufficient ingestion period by benefactor organizations? The Chirumanz Caritas Community Gardening Project experience I Zimbabwe. J Geogr Earth Sci. 2014;2(1):127–48.

Ministry of Finance and Economic Development. National Development Strategy 1: towards a prosperous & empowered upper middle income society. Harare: Print flow; 2020.

Moucheraud C, Schwitters A, Boudreaux C, et al. Sustainability of health information systems: a three-country qualitative study in Southern Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;2017:17.

Mpofu P. The dearth of culture in sustainable development: the impact of NGOs’ agenda and conditionalities on cultural sustainability in Zimbabwe. J Sustain Dev Afr. 2012;14(4):191–205.

Muluh GN, Kimengsi JN, Azibo NK. Challenges and prospects of sustaining donor-funded projects in rural Cameroon. Sustainability. 2019;11(24):6990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246990.

Mutale Q. Factors affecting the success of NGO interventions in social service provision for the rural poor communities in zimbabwe: Case of Luunga ward 1 in Binga District. A dissertation submitted to the Midlands State University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bachelor of Science in Local Governance studies honours degree. 2016.

Mutale W, Ayles H, Bond V, et al. Application of systems thinking: 12-month postintervention evaluation of a complex health system intervention in Zambia: the case of the BHOMA. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;2017(23):439–52.

Ndhlovu E. Relevance of sustainable livelihood approach in Zimbabwe’s land reform programme. Africa Insight. 2018;47(4):83–98.

Onwujekwe O, Obi F, Ichoku H, et al. Assessment of a free maternal and child health program and the prospects for program re-activation and scale-up using a new health fund in Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2019;22:1516–29.

Ronalds P. Reconceptualising international aid and development NGOs, critical reflections on development. 2013, 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230389052

Sally Z, Gaskin SJ, Folifac F, Kometa SS. The effect of urbanization on community-managed water supply: case study of Buea, Cameroon. Community Dev J. 2013;2013(49):524–40.

Sarupinda D. Market and supply chain assessment report for Binga: SCF, Zimbabwe; 2010.

Speizer IS, Guilkey DK, Escamilla V, Lance PM, Calhoun LM, Ojogun OT, Fasiku D. On the sustainability of a family planning program in Nigeria when funding ends. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0222790.

Trammel M. The Tonga people of the great river. Gweru: Mambo press; 1994.

Prabhakar KL, Latha K. Non-government organizations: problems and remedies in India. Serb J Manag. 2011;6(1):109–21.

Wickremasinghe D, Hamza YA, Umar N, et al. A seamless transition': how to sustain a community health worker scheme within the health system of Gombe state, northeast Nigeria. Health Policy. 2021

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.sustainabledevelopment/goals. 2017.

World Bank. Poverty and shared prosperity 2020: Reversals of fortune. Washington: World Bank; 2020.

Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC). 2019 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Report. Zimbabwe: Harare; 2019.

Funding

This article was not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMM invented the idea. All authors (MMM, BD, OM and JH) collected data, BD wrote the main manuscript and all authors (MMM, BD, OM and JH) reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Midlands State University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsa, M.M., Dzawanda, B., Mupepi, O. et al. Sustainability of donor-funded projects in developing remote minority Tonga communities of Zimbabwe. Discov Sustain 4, 34 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-023-00152-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-023-00152-8