Abstract

In the United States, the transition from unchecked hunting, habitat loss, and species endangerment to an ongoing environmental awakening has been examined through various lenses. Despite this gradual perspective shift, recent reports continue to warn of global declines in species and habitat diversity. As the need for biodiversity conservation grows, nations lag behind in their conservation obligations, creating a funding gap. This paper addresses an untapped potential for funding available from stamp revenue as generated in the United States. We begin with an historical summary of wildlife philatelics and end with specialized stamps providing for biodiversity revenue generation. After the publication of Silent Spring, stamp diversification increased due to the recognition of additional environmental and conservation needs, leading to stamp-based revenue as one means to mitigate funding gaps. Having introduced this term, we provide evidence of its potential to fund biodiversity and animal conservation. Historically, stamp-based revenues began with Migratory Bird Hunting license stamps, followed by the semi-postal Amur tiger cub stamp, and eventually local and state stamps whose purchase provides funding for local conservation needs. Specific successful philatelic funding mechanisms are discussed from the United State, with an eye to future development and expansion intentionally in support of conservation and biodiversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Historical review of philatelic conservation: 1916–2020

Despite international agreements and global concern focused on the loss of biodiversity, declines continue at what many consider alarming rates [3]. While sufficient funding may indicate a shortfall globally, nevertheless, the desire to protect animal species and habitats has led to conservation programs at the global, national, or local level, with each having its own stakeholders and support. However, before this plurality of conservation responses came to be, it was preceded by a decades-long struggle to move from a public acceptance of the inevitability of species’ extinction. Those just now becoming interested in this topic might reasonably assume that species protection was always a reality and that the importance of ensuring the Earth’s natural heritage was never more than conventional wisdom. But, this could not be further from the truth.

In reality, effecting this transition towards conservation was neither rapid nor facile. When President U.S. Grant created the first national park in 1872, the American bison were nearly extinct. Yet the National Park Service was not established until 44 years later and it was not until 1993 that a National Biological Survey was created to identify species and habitats at risk [1]. While many individual and legislative efforts were to follow the National Biological Survey, the next germane federal effort was the conservation and protection of migratory waterfowl and their wetland habitats [4,5,6].

The need for additional conservation legislation arose from the fact that from the 1880s to the 1930s, colonial Americans (i.e. not Native Americans) hunted several species of wildlife to extinction. Declines from hunting were so extensive during this period that the decade of the 1900s has been termed “The Age of Extinction,” [24]. Remediating the near-complete loss of waterfowl was the impetus behind of the 1916 Migratory Bird Convention between the United States and Canada and passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 that codified the Convention in U.S. Federal law (Table 1, row 1.1) [13]. But this legislation did not include a funding mechanism to fiscally support migratory waterfowl habitat protection. Owing much to the efforts of Thomas Beck, of what became Ducks Unlimited, together with Jay “Ding Darling, and Aldo Leopold, authorization of funding was eventually obtained [24].

It was at this time that philatelic issuesFootnote 1 were created specifically to fund conservation. For example, in 1934 Congress authorized creation of a license to hunt waterfowl, resulting in the issuance of Migratory Bird Hunting Permit Stamps (colloquially referred to as “Duck Stamps’), to be carried by hunters as proof of license. This became the chief funding mechanism for rescuing waterfowl and habitats, with the stamps leading the way “to a constructive conservation program at a time when other funds were practically unavailable,” [13], (Table 1, row 1.2). The annual production and sales of the Duck Stamps is overseen by the Fish and Wildlife Service, which reports that some 1.5 million stamps are sold annually, totaling to over $1 billion as of 2019 [12].

Largely resulting from publication of Silent Spring [2], environmental legislation was passed, culminating in the first celebration of Earth Day in 1970 (Table 1, row 1.4) and the Wilderness Act in 1964. These were followed by the National Environmental Protection Act, establishing the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, and protecting wildlife through the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Following these inter-related actions, Americans eventually came to what has been called by Meine [26] a “period of environmental awakening” (Table 1, row 1.5).

The “Dawn of Ecology” [24] was the name given to the 1950s, as the deleterious environmental impact of organochlorine pesticides became apparent. During this era and preceding the ban on DDT, the U.S. stamp issuance program changed again, with concerted efforts made to address and reverse the lack of wildlife and conservation themed stamps. As a result, the first four true wildlife conservation postage stamps did not appear until 1956–57 created from the artwork of Robert W. (Bob) Hines [4, 5] (Table 1; row 1.3).

This breakthrough was the beginning of the ongoing issuance of conservation and environment-themed postage stamps, providing an essential tool for raising awareness, enabling commemoration of Earth Day, and educating the public. These stamps also fulfilled a public education and awareness mission, which is an often overlooked role of the US Postal Service [29]. The USPS fulfills this mission largely through issuance of conservation and environmental-themed postage stamps and related publicity materials, and from them, a funding mechanism for conservation often follows, as will be explained.

The advent of biodiversity, occurring as it did through a scientific forum in 1986 and the Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992 marked the most recent environmental concern brought to the nation’s attention. It was after this conference, and discussions of global declines in species diversity, that biodiversity’s inclusion in education and research really got underway, as noted in the conference proceedings [31]. It was not until ten years later that the term “biodiversity” was first used by the USPS.

However, it has not been featured on a postage stamp but rather was used inside a USPS publication on endangered species [21]. However, other countries, following the United Nations declaring 2010 as the year of biodiversity, issued numerous postage stamps and related philatelic materials (Table 1; row 1.8) [6, 28]. These are shown to emphasize the absence of similar stamps from the USPS.

2 United States data collection and analysis for stamp-based revenue generation for conservation

Having reviewed the historical background, it is now possible to present and analyze the data needed to substantiate United States historical trends and chronology. Taken together, this data (comprising 335 individual stamps grouped into four themes), forms the foundation of a still-increasing array of conservation and environmental agendas. Data was collected and entered into an Excel spreadsheet, and then cross-checked with published stamp descriptions and pricing [15, 20] to assure accuracy in interpretation and grouping before analysis (see Additional file 1). Examples of how stamps helped address prioritized conservation objectives and met some of the related financial needs through postage stamp revenue will be presented.

First, a baseline ending at 1950 enabled measurement of stamp issuance before and after the US Post Office Dept. first issued wildlife conservation themed stamps; 1950 also being most similar to the baseline originally proposed by Kalmbach [19]. From these stamps, four themes were identified to further organize and classify this philatelic material: conservation awareness; endangered species and wildlife conservation; environmental protection, and habitat awareness/parks (Table 2). The three time periods examined are 1900 to 1950; 1950 to 1962; and 1963 to 2020, specifically to consider the impact of the publication of Silent Spring [2].

Kalmbach determined that prior to the 1950s, America’s postal authorities, unlike those in many other countries, chose not to celebrate or portray its wildlife on postage stamps. Nor did the USPOD introduce the notion of conservation as a counter-point to extinction. Our data substantiates these findings, agreeing that the 1932 Arbor Day stamp is the first conservation-themed US postage stamp (Table 1; row 1.2).

Such omission underplayed the importance of the unique ability of stamps to educate and raise awareness of important issues of national concern [29]. Following Kalmbach’s publication, five years of public and political pressure, including personal intervention of several high level officials and a direct appeal to President Eisenhower, were required to overcome the USPOD inclination to commemorate past presidents and finally enable American wildlife to appear on a set US postage stamps (Table 1; row 1.3) (Fig. 1).

Table 2, row 1.1 reflects Kalmbach’s global estimate with the United States just now approaching that post-1950 total (row 1.3). As noted above, 1962 was selected to account for the impact of Silent Spring, which can be extrapolated, as show in Fig. 3, where the paucity of wildlife/conservation oriented stamps can be seen as the baseline in blue. Post-1962, the greatest percent increase was in environmental protection (up 11.5%) and endangered species/wildlife (up 3200%). General themes of conservation awareness, while present, are given less emphasis than the more specific stamps. Also, major and on-going trends stabilized following Carson’s Silent Spring.

These USPS stamps, like all others, fulfill the historically important role of providing an evidentiary demonstration that fees imposed to convey written materials between locations were paid by the sender. Secondarily, they serve as a medium of propaganda, an educational tool describing “the great epochs of America,” [9], and are a means of focusing public attention on matters of current or historical importance. More recently, however, stamps have also functioned as a funding mechanism for special causes, moving from the national postal system to local targeting, production and sales.

The term “stamp-based revenue generation,” or SbRG, is introduced in this paper to describe stamps with or without postal services, and a means of funding an agreed-upon public good. SbRG is commonly used to benefit traditionally under-funded conservation efforts. One example of such would be wetlands, where the duck stamp revenue was essential for their preservation as other national funding would not be forthcoming. Because stamps have a recorded first day of issue, their timelines document how SbRG enables wildlife conservation and establishes conservation education and awareness.

Despite the potential for building public awareness of conservation and environmental concerns, bringing wildlife conservation and habitat preservation to the attention of the USPS proved exceedingly difficult. For example, Duck Stamp sales, waterfowl conservation efforts, and wetlands preservation programs were administered by the Department of the Interior. It was not until much later that SbRG was embraced as a conservation funding mechanism by the United States Post Office Department (USPOD)Footnote 2 and by state Natural Resources Departments.

For example, as stated earlier, efforts to establish the Migratory Bird Hunting License Permit Stamp program to protect migratory birds got underway in 1919 when George Lawyer, a Conservation Commissioner for New York, called for wildlife to appear on US postage stamps [27]. A second appeal was undertaken by Raymond Holland, editor of Field and Stream magazine and convicted pond baiter. In the July 1920 issue of the periodical, Holland argued that provisions of both the Canada-US Migratory Bird Treaty of 1916–1918 and a similar convention of 1936 between the United States and Mexico clearly established a mandate to collect financial assets for conservation. Unfortunately, such funding was neither mandated nor established.

Finally, on March 16, 1934 the bill authorizing sales of the first Duck Stamp was signed into law (Table 1; rows 1.1 and 1.2) [13]. Most recently, Department of the Interior announced that $160 million was approved for conservation, all funds coming from “our great conservationists – the hunters and anglers who purchase migratory bird stamps,” [10]. Each of these stamps is a hunting license, with funds going to conservation, with no amount available for US postage.

3 The U.S. semipostal, Amur tiger cub “Save the Species” stamp supporting animal conservation

A second SbRG example is a semi-postal stamp linked to the Multinational Species Conservation Fund (MSCF). Unlike hunting permit Duck Stamps, a semi-postal stamp or semipostal, also known as a charity stamp, is issued to raise money for a charitable purpose and sold at a premium over the postal value [25]. Typically the stamp shows two denominations separated by a plus sign, but in many cases the only denomination shown is for the postage rare, and the postal customer simply pays the higher price when buying the stamps.

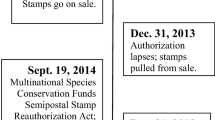

The only US semi-postal stamp issued for conservation features an image of an Amur tiger cub stamp and was first released in 2011 (Table 1; row 1.9). For this stamp, as an example, in addition to the 44¢ cent first class mailing fee, this “Save the Species” Amur Tiger stamp bears an 11¢ surcharge added as a contribution to the MSCF.

Enactment of the Semipostal Authorization Act on July 28, 2000 was necessary before the USPS could design and sell such stamps and to grant authority to establish the Multinational Species Conservation Funds grants to projects benefiting elephants, rhinos, great apes and marine turtles in their natural habitats (Table 1; row 1.8; Fig. 2). This law ensured that the advance of such funds for conservation were in, “the national public interest and appropriate.”Footnote 3 Between 1988 and 2004, various species conservation acts were authorized as part of the Multinational Species Conservation Fund (MSCF).

4 Outreach and education regarding the semipostal Amur tiger cub stamp

The success of the “Save the Species” stamp can be seen in the public’s demand for its continuing authorization by Congress, up to the present year of 2021. As early as 2009, the public interest in support of these programs was recognized and increasing. MSCF supporting organizations include the African Elephant Conservation Fund, the Asian Elephant Conservation Fund, the Great Ape Conservation Fund, the Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Fund, and the Marine Turtle Conservation Fund [11] (Fig. 2; Table 3). A recent impact statement on reporting of expenditures saw 50,784,806 million stamps purchased, with Americans raising $5,740,478 for conservation efforts to preserve some of the most iconic and charismatic animals on Earth [8].

4.1 Educational setting

In addition to these figures, attesting to the move towards an “environmental awakening,” the “Save the Species” stamp was brought into an educational setting where secondary students were given the opportunity to determine whether they would invest in such stamps themselves. Their choices were recorded through a “willingness to pay” analysis, with a majority of students opting to participate in either full sheet (20 stamps) or in partial sheet purchases [7]. This study will lead to expanded work in secondary schools once students are allowed to return.

5 State-Issued philatelic funding mechanisms to meet local conservation priorities

The following examples derive from stamps authorized by states to earn revenue for localized wildlife conservation, but again, these stamps carry no postal value. As noted by Wilkinson [30], state government and institutions have significant advantages in understanding and setting local biodiversity priorities. Examples of such “localized wildlife conservation” are illustrated in Fig. 3, showing how seven states targeted an array of local causes supported through SbRG mechanisms. Some states offer only an electronic “stamp” receipt, while others offer a variety of stamps addressing diverse state conservation priorities (See Fig. 3a; Table 4). In addition, from Table 3, it can be seen that Canada and one non-governmental organization (Fig. 5) also produced stamps earning conservation funding.

Potential for raising funds from these localized conservation efforts can be demonstrated by the Black Bear reimbursement fund stamp (Fig. 3a), which began in 1996. It was authorized by the Maryland General Assembly, allowing the stamp to generate funds that to compensate farmers reporting damage to agricultural crops caused by black bears. Funds are generated through sales of these stamps which also contribute to the bear’s conservation and management. Figure 4 illustrates the significant funding raised by the sales of these stamps for farmer reimbursement purposes. Here, it can be seen that support to farmers remained stable from the first year data was available until 2020, indicating continuity from philatelic resources in all but one year, during which stamps were not sold. In total, for the 12 years, over $28,000 was earned to meet local needs as related to Maryland’s conservation and management of Black Bear populations.

States can also augment the stamp-based funds through annual art competitions. Entrance fees, subsequent merchandise sales, and other means of income generation provide prize money for winners but also significantly increase funds available for the designated conservation cause.

6 SbRG from state-issued philatelic stamps: complementarity not competition

While potential for overlap or competition between locally-oriented philatelic wildlife stamps exists theoretically, no such problems were reported to the authors during collection of stamps and data. The senior author personally subscribes to all localized stamps featured in this article, with no comment received as per competitive measures taken as a result of hostile intentions. At the present time, conservation and preservation needs are so vast, due to loss of habitat and fragmentation that conflicts have not arisen among the local providers.

7 Examples of national revenue stamps for animal conservation from other countries

While the primary purpose of this article has been an examination of SbRG from American philatelic mechanisms, a natural addition would be a brief expose of international examples of SbRG, as for example, those coming from the World Wildlife FundFootnote 4 (WWF). It partners with specific countries for the production of stamps addressing biodiversity needs, as illustrated in Fig. 5 by Palestine and Guinea. These also support “localized wildlife conservation” from sales of the stamps supports local conservation efforts [14]. This stamp partnership between an international NGO and one nation have become an effective collaboration for conservation. The United States has such bilateral arrangements as well; however, they have not been for revenue generation. Given the range of philatelic “partnerships,” it would seem worthwhile to consider them together, in a review and planning meeting with eyes towards helping to meet global conservation costs.

As of a recent report, the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) had printed over 1 billion stamps covering 400 separate issues. Total sales from these stamps amounted to 20 million Swiss francs ($18.5 million), becoming a major asset in funding for conservation activities [32]. This collection of stamps has since become the “largest thematic collection in the world. Since 1983, some 1,500 different stamps have been issued in 211 countries.”

8 Conclusion

Funding levels required for animal conservation can be expected to rise with increasing numbers of species endangered and therefore relying on humanity’s sense of purpose to serve as providers and conservators. But these costs can be staggering, as the projected $1 billion to secure Africa’s lions [23]. In addition, revenues from hunting licenses seem on the decline [22]. As demonstrated in this paper, SbRG is one, perhaps undervalued, mechanism for generating such funding for global, national, or local-scale conservation.

Wildlife conservation and preservation will continue to take place at local, national and international levels. However, local-minded individuals want to see resources available to secure natural places within their own locale. This is evidenced by the increasing efforts to secure wildlife or conservation corridors in many states, such as Florida. For this reason, locally-focused philatelic options such as those shown here will be of considerable value. The costs to conservationists for securing landscape fragments will rise, which can be met by increasing sales and costs of related stamps.

Conservation stamps issued by states provide more versatility in the type, cause and locality represented than the USPS offerings (Fig. 3). For example, over time, the pioneering Migratory Bird hunting stamps began to inspire similar national and state programs as the initial federal effort was found insufficient to meet the funding needs of nationally established reserves and those a state or county would nominate. Presently, local conservation stamps also have the potential to counter habitat fragmentation by providing funds to purchase property that would help build or solidify “local” conservation corridors.

Once such a corridor is connected, it then offers further financial potential from sources such as ecotourism. Another important philatelic option came from the various conservation approaches Maryland funds through black bear stamps. Together, these stamps show that a philatelic approach is able to support multiple programmatic efforts even for the same species. Another “plus” for a philatelic approach to conservation funding is that once the target species and habitat are selected, artistic competition can occur, with the winner’s work used as the final stamp design. The artistic element of these stamps offers another way to obtain community involvement and education. This artistic aspect could also increase the profile of naturalists and artists, who may ordinarily have overlooked such opportunities in the past.

International or global organizations can also advance philatelic funding options among their local or nationally affiliated branches, thus targeting species that migrate or live where they are in harm’s way. Examples of such endeavors were shown in Fig. 5. Clearly, there would be much to learn from one another in terms of SbRG, and a body such as IUCN could help advance strategic thinking and encourage exchange of shared experiences on animal conservation using philatelic approaches described in this paper [17].

For example, individuals responsible for programs mentioned herein could develop case studies, while others estimate future demands and funding shortfalls. Of course, philatelic mechanisms would never make up for all shortfalls itemized in the Global Biodiversity Outlook 5, but identifying strategic approaches for philatelic mechanisms would help ensure efficiency and efficacious applications. Identifying such approaches to SbRG for conservation, determining value of respective stamps, pursuing their use in outreach and education, are initially touched on in this article. However, it should be clear that the authors encourage subsequent analysis and this paper be viewed as foundational; an illustrative rather than exhaustive study; but one that by its reflection, calls attention to demonstrated philatelic options for meeting ongoing and future conservation needs.

Availability of data and materials

A full philatelic-conservation data base is available if needed.

Code availability

None applicable

Notes

According to Juell et al. (2016), philatelics pertains to, “the hobby of collecting stamps, postal stationary, postal history, and related materials,” which is taken to mean those items affixed as stamps but do not carry actual postage valuation, as well as regular United States Postal Service (USPS) stamps which are valued for mail and delivery. Each stamp released is an “issue, or issuance,” done according to a postal calendar showing the first day ceremony date for every official stamp.

Please note that from 1872 to 1971 the United States Post Office Department (USPOD) was an official Executive Branch Cabinet Department headed by the Postmaster General. The Postal Reorganization Act signed by President Richard Nixon on August 12, 1970 replaced the cabinet-level Post Office Department with a new federal agency, the United States Postal Service, and took effect on July 1, 1971.

These Acts differ from those for breast cancer awareness, as each semi-postal has its own funding mechanism, making it different from standard postal stamps and therefore requiring independent legislation.

WWF represents the World Wildlife Fund, as known in the United States and Canada, or the World Wide Fund for Nature, an international NGO headquartered in Switzerland, or WWF International. The stamps are all printed in Switzerland, so in this case, the organizational name would be WWF for Nature.

References

Brown R. A conservation timeline. The Wildlife Professional, Fall 2010: 28-32

Carson RL. Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin Co. The Riverside Press, Cambridge, MA; 1962. 366 pp.

CBD Secretariat (Convention on Biological Diversity). Global Biodiversity 5. Montreal; 2020.

Cohen JI, Altman S. America's Conservation Saga. From the philatelic and narrative art of Kalmbach, Darling, Hines, Carson to considerations of biodiversity. Segment I. The United States Specialist, March; 2020a. pp. 116–129.

Cohen JI, Altman S. America's Conservation Saga. From the Philatelic and narrative art of Kalmbach, Darling, Hines, Carson to considerations of biodiversity. Segment II. 1940 to 1970: Bob Hines, Rachel Carson and Earth Day. United States Specialist May; 2020b. pp. 202–223.

Cohen JI, Altman S. America's Conservation Saga. From the Philatelic and narrative art of Kalmbach, Darling, Hines, Carson to considerations of biodiversity. Segment III. 1970 to 2020: From Earth Day to Biodiversity. The United States Specialist, July; 2020c. pp. 303–325.

Cohen JI, Mark H. Managing biodiversity—providing “real world” experience and consequences of biodiversity decline and Anthropocene extinctions. Am Biol Teach. 2021;83(6):172–8.

CRS (Congressional Research Service). Multinational species conservation fund semipostal stamp. CRS #R44809, Washington D.C.; 2017. 7 pp.

Davidson C, Diamant L. stamping our history—the story of the United States portrayed on its postage stamps. Carol Publishing Group, New York; 1990. 250 pp.

DOI (United States Department of the Interior). $160 million in funding for wetland conservation; 2020. https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-bernhardt-announces-160-million-funding-wetland-conservation-projects-and

Fish and Wildlife Service. International affairs: multinational species conservation acts. 2009. https://www.fws.gov/international/laws-treaties-agreements/us-conservation-laws/multinational-species-conservation-acts.html

Friends of the Migratory Bird/Duck Stamp. 2020. Duck Stamps Conserve Wildlife Habitat. http://www.friendsofthestamp.org/duck-stamps-conserve-wildlife-habitat/.

Gilmore JC. Art for conservation, The federal duck stamps. Barre Publishing Co., Inc; 1971. 95 pp.

Groth H. WWF stamp collection helps conservation. World Wide Fund for Nature International. 2006. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?86920/wwf-stamp-collection-helps-conservation.

Harris and Company. 2019 Edition Price Guide - Postage Stamp Catalog. Whitman Publishing, LLC. Pelham, Alabama; 2019. 400 pp.

IEF (International Elephant Foundation). Multinational Species Conservation Fund. 2012. https://elephantconservation.org/multinational-species-conservation-fund/

IUCN. Closing the gap. The financing and resourcing of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa. Nairobi, Kenya: IUCN, ESARO; BIOPAMA; 2020. 80 pp.

Juell RA, Batdorf LR, Rod SJ editors. Encyclopedia of United States stamps and stamp collecting, 2nd edition. Ohio: Minuteman Press; 2016. 769 pp.

Kalmbach ER. Wildlife in the mail. Nature Magazine, June-July 1950: 317–32

Kloetzel JE. Scott stamp and coin company specialized catalog of united states stamps and covers. Sidney Ohio: Scott Publishing Company; 2002.

Kurie W. Endangered species—a collection of U.S. postage stamps. United States Postal Service, Washington D.C.; 1996. 40 pp.

Larson L. As hunting declines, efforts grow to broaden the funding base for wildlife conservation. The Conversation. 2018. https://theconversation.com/as-hunting-declines-efforts-grow-to-broaden-the-funding-base-for-wildlife-conservation-105792

Lindsey PA, Miller JRB, Petracca LS, Dickman LCJ, Fitzgerald KH, Flyman MV, Funston PJ, Henschel P, Kasiki S, Knights K, Loveridge AJ, Macdonald DW, Mandisodza-Chikerema RL, Nazerali S, Plumptre AJ, Stevens R, Van Zyl HW, Hunter LTB. More than $1 billion needed annually to secure Africa’s protected areas with lions. ProcNatlAcadSci. 2018;115(45):E10788–96. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805048115.

Line L, editor. The National Audubon Society. Speaking for nature: a century of conservation. New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, Inc; 1999.

Mackay J. The world encyclopedia of stamps and stamp collecting. United Kingdom : Anness Publishing; 2011. 256 pp.

Meine C. Conservation movement, historical. encyclopedia of biodiversity, vol 2. Elsevier; 2013. p. 278–88.

Posner C. 1950s. Cataloging U.S. Stamps: Pronghorn antelope (Scott 1078). The American Philatelist. October; 2017. p. 944–954.

U.N. (United Nations). International year of biodiversity. J UN Philat. 2010;34(3):5.

Walczak S, Switzer AE. Raising social awareness through philately and its effect on philanthropy. PhilanthrEduc. 2019;31(1):73–102.

Wilkinson JB. The state role in biodiversity conservation. Issues SciTechnol. 1999;15(3):71–7.

Wilson EO, editor. Peter FA, Assoc. editor. Biodiversity. Washington D.C.: National Academy Press; 1988. 500 pp.

World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Guide to conservation finance—sustainable financing for the planet. Washington, DC: WWF; 2009. 54 pp.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank a number of individuals in preparation of this manuscript. We begin with Nancy Doran of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources in the Wildlife and Heritage Service. Then, thanks to Cory Brown, Suzanne Fellows, Matt Muir, and Don Morgan of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; Martin Miller, Editor of The Specialist, Mr. Rodney Juell, for comments on philatelic matters, and two anonymous reviewers for Animal Conservation.

Funding

No external funding received; author’s own time.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors contributed to and understand conditions of, those stated in the guidelines.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

None at all.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Data categorizing stamps issued by the United States into four groupings of environmentally themed images and topics, covering past decades, and aggregated by their particular theme.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, J.I., Altman, S. An historical analysis of united states experiences using stamp-based revenues for wildlife conservation and habitat protection. Discov Sustain 2, 24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-021-00031-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-021-00031-0