Abstract

Offering products as a service is a way to implement circular economy principles in business models and promote sustainability. However, in many markets, the model is still in its infancy in terms of market maturity and lacks customer acceptance. More understanding is needed of how product-as-a-service companies can enhance and reconfigure their competitive position by proposing meaningful customer value. For this purpose, this study focuses on customer value propositions (CVPs) as a strategic management concept in the circular economy. The aim of the study is to outline a deconstruction framework for systematically identifying the strategically manageable components of CVPs in circular product-as-a-service business models. The framework establishes a link between the elements of circular product-as-a-service business models and competitive CVPs. The framework is developed and validated with seven product-as-a-service business cases in the textile and clothing industry context. The results of the study provide insights into how product-as-a-service companies in the textile field aim to differentiate, how they structure customer value by identifying customer benefits and sacrifices, and what kind of resources and capabilities are needed for competing in the circular economy context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Offering products as a service instead of product ownership is a way to implement circularity, prolong product lifecycles, and support efficient resource use [1, 2]. Product-as-a-service business models are typically based on renting or leasing products and sharing them with a group of customers [2, 3]. Ideally, in the product-as-a-service business model, the product is made as material- and cost-efficient as possible while creating environmentally and socially sustainable service offerings [2]. Recent evidence suggests that the product-as-a-service model is still in its infancy in terms of market maturity, and linear business models remain dominant in most markets [4]. Several barriers exist to customer adoption of the product-as-a-service model, such as a lack of awareness and the dominance of ownership-based culture [4].

To drive customer acceptance and gain space in the markets, product-as-a-service companies need to understand how to compete by proposing meaningful customer value [5, 6]. For this purpose, this study focuses on customer value propositions (CVPs) that are considered managerial concepts at the core of a company`s business model [7, 8]. CVPs are tools for strategically guiding a company on how it creates value for its customers and achieves differentiation from competing offerings [6, 8,9,10]. Despite the widely acknowledged importance of a company’s ability to manage how customer value is proposed in a competitive way [10], CVPs as strategic management concepts in the circular economy have not been widely studied. While prior studies have provided insights into articulating and designing value propositions in the circular economy [11,12,13,14], a detailed view of how companies can manage differentiation and the structure of customer value while offering products as a service is missing. Moreover, the current literature has acknowledged the need for a strategic and customer-oriented perspective on circular economy value propositions [11, 13] and on frameworks and tools for developing circular economy business models [15].

To address this critical gap, the purpose of this study is to outline a deconstruction framework for strategic CVP management in product-as-a-service business models. The deconstruction approach aims to explicitly identify CVP elements by systematically taking them apart [16]. The study contributes to the existing literature by offering an approach for systematically analysing CVPs for the circular product-as-a-service model and dissecting them into manageable components that can guide strategic managerial decision-making. The research question is: How are CVPs strategically managed in circular product-as-a-service models?

Circular business models are innovated and exist in a malleable and complex market that is continuously changing [17]. Therefore, the deconstruction framework is based on the notion that the strategic management of circular business models needs to adapt continuously to the changing market logics during the ongoing circular economy transformation. The purpose of the framework is to enable this kind of reconfiguration of CVPs for product-as-a-service business models. As a concept, deconstruction enables rethinking key parts of strategy and how customer value is proposed [16, 18]. Therefore, in this study, we argue and demonstrate that applying the deconstruction approach to product-as-a-service CVPs enables a rigorous structure for identifying which elements of the CVPs accelerate differentiation and how product-as-a-service models are positioned in the market, which customer benefits are aimed to be increased, which customer sacrifices are aimed to be decreased, and what kinds of resources and capabilities are required from companies to create customer value competitively in the circular economy.

The proposed framework is developed and validated with seven product-as-a-service business cases in the textile industry context. The textile and clothing industry is a crucial empirical setting for investigating the topic, as the industry is identified as one of the most pollutant-releasing industries in the world and a circular economy transition is critically needed [19, 20]. From an environmental perspective, the challenge is that the prevailing operating models of the textile and clothing industry are based on linear economy principles with the mass production of textiles and wasteful fast fashion [19]. The textile and clothing field in general is characterized by frequent consumption, quickly changing demands and trends, and short-lived product use [19, 20]. It is estimated that globally, customers discard annually up to USD 460 billion by throwing away usable clothing [21]. In the fashion field, new service-based business models such as “clothing as a service” are seen as promising models for shifting the fast-fashion mindset towards a more durable perception of clothing [22].

This paper is structured as follows: First, we provide theoretical background on the circular product-as-a-service models and CVPs. Second, a framework for deconstructing product-as-a-service CVPs is presented. Third, the methodology section describes the case study in the textile industry context. Fourth, the results section presents the findings from the deconstruction of product-as-a-service CVPs in the textile industry. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion, implications, and future research directions.

Theoretical Background

Circular Product-as-a-Service Business Models

Substituting product ownership with services and incorporating service elements such as logistics or maintenance are one of the mechanisms for realizing circular economy principles in business models [23]. The circular product-as-a-service model enables slowing resource loops as the lifecycle or usage period of the product is extended [24]. The model aims to reduce the total number of products needed, as the products are reused, consequently lowering the material and energy input required for production [3, 25]. Additionally, these models are suggested to enable a second life for products that can be achieved through recovery activities such as repair [26].

Product-as-a-service models have especially been discussed in the literature streams for Product Service Systems (PSS) [2, 3] and servitization [27]. The basic idea of a product-as-a-service business model is that the product ownership remains with the service provider and the products do not stay in the possession of customers after usage. The focus is shifted to services and delivering functionality and product use [28]. Therefore, customers are not seen as owners but instead as users, and the value of products is represented by the number of functional units that they can provide in the lifecycle [29]. Overall, the product-as-a-service concept is an integration or mix of products and services [2]. The model typically engages intermediate actors of the value chain to facilitate the product-service mix, for example to execute product delivery, reverse logistics, take-back processes, or product validation [30,31,32]. Therefore, the value propositions of product-as-a-service models aim for shared and mutual value creation among actors and joint fulfilment of customer needs [2, 32].

The product-as-a-service model is categorized as a use-oriented PSS, which is based on product leasing, renting, sharing, and pooling. In these contexts, the repetitive process of companies providing and customers sequentially using products is considered pivotal [2, 3, 33]. The payment system in use-oriented services is based on pay-per-unit of the used service, which creates an economic incentive for producers to decrease the amount of processed resources [34]. In use-oriented services the items can be shared by several users [3]. Thus, the product-as-a-service model applies the principles of sharing and collaborative economy, in which the usage level of products is increased as the products are shared among a group of actors [35]. Moreover, the model offers access to products for customers; therefore, the term access-based consumption is used in prior literature to refer to these models [36, 37].

The share of product-as-a-service models in many markets is currently low [4]. For example, in the textile industry, fashion rental models are currently considered a niche market, whereas traditional, linear models such as fast fashion are considered mainstream [4, 38, 39]. While product-as-a-service models are generally perceived as having potential for increasing circularity and improving environmental sustainability, prior literature acknowledges that these impacts can only be achieved by increasing consumer adoption and, thus, acquiring a bigger market share [38, 40, 41]. A deeper understanding of the strategic marketing management of these models is needed for this purpose [14, 17, 42]. Moreover, recent research has identified several issues that affect the management of product-as-a-service models as attempts are made to optimize their environmental sustainability impacts. For example, product-as-a-service models must substitute, not just complement, other more resource-intensive models that are based on ownership [1, 43]. Logistics need to be optimized and low-emission transport modes used, particularly related to use-oriented services [44]. Furthermore, PSS models may even reinforce consumerism and increase consumption [44, 45]. Therefore, to reduce environmental sustainability risks it is important that the models are local and encourage sufficiency [44].

Customer Value Propositions

Customer value propositions (CVPs) are strategic managerial concepts that reflect what a company believes the customers value the most [6, 8, 10]. CVPs rely on identifying the resonation of the offering with the customers’ specific needs and problems and the company`s resources and competences to deliver value to customers in a competitive way [6, 8,9,10]. CVPs are often placed at the core of the company`s business model [7, 8], along with other business model components such as value creation, value delivery, and value capture [28].

To date, only a few studies have investigated CVPs in the circular economy, and they have focused primarily on the process of designing CVPs in the context of circular economy innovations [14], product longevity [12], and the environmental impacts of circular business models [42, 46]. Even though prior literature highlights the critical role of CVPs at the core of a circular business model, the strategic management dimension of CVPs in the circular economy is currently unexplored.

In this paper, we focus on this dimension and specifically address two complementary perspectives. First, the strategic management of CVPs aims for company positioning and competitive advantage [6, 9]. To gain a competitive advantage, CVPs should highlight the uniqueness of the offering and be recognizably different from competing actors [10]. CVPs are composed of value elements that refer to points of difference or points of parity [47]. The points of parity are similar features to other offerings in the market and should be included in the CVP to communicate the value that is taken for granted by the customers [10, 47]. The points of difference demonstrate the unique elements of the CVP and accelerate the differentiation of the offering compared to other market actors [10, 47]. CVPs can also address the resonating focus [47]. This means that the CVP value elements focus on delivering value that is most important to the target customers instead of highlighting solely points of parity or points of difference.

Second, the strategic management of CVPs aims at structuring customer value by identifying the trade-offs between the benefits and sacrifices that the customer is assumed to perceive of the company`s offering [6, 48]. For creating competitive CVPs, companies need to understand the positive and negative consequences for customers of experiencing the offering [10]. Trade-offs between benefits and sacrifices refer to the suggestion that customer value is created when customers perceive greater positive consequences than negative [48]. Therefore, effective CVPs should aim to increase the perceived benefits and simultaneously decrease the perceived sacrifices [10].

Framework for Deconstructing Customer Value Propositions for the Circular Product-as-a-Service Model

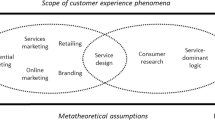

Several frameworks and tools have been created to facilitate the development and evaluation of circular business models [15]. For example, Bocken et al. [5] have developed a value mapping tool that can be used to identify different forms of value (i.e., value captured, missed/destroyed or wasted, and opportunity) of a business model with relevance to key stakeholder groups (i.e., environment, society, customer, and network of actors). More recently, Manninen et al. [46] presented a framework for evaluating the environmental value propositions of circular business models. These previous frameworks focused on how diverse forms of value are adapted to the circular economy context. However, these studies do not explore circular value propositions from the strategic management perspective, and a granular view of customer value management is missing. Moreover, there is a need for further investigation of the key components of CVPs, particularly in the context of the circular product-as-a-service model. Therefore, this section presents the framework for deconstructing the CVPs of the circular product-as-a-service business model (Fig. 1).

The Deconstruction Concept

The framework adopts the deconstruction approach, which in the context of value propositions involves critically and systematically decomposing socially constructed concepts [16]. Deconstruction as a mechanism can guide managerial decision-making as value propositions are broken down into manageable components [49]. Furthermore, key segments of business strategy and understanding what customers value are rethought in the deconstruction process [16, 49]. This can increase understanding of the elements of a superior offering [16], which is hugely important in the context of circular product-as-a-service models, as their superiority needs to be more thoroughly argued and articulated in relation to the traditional offerings that are aimed to be substituted [1, 43].

Previous studies have considered the deconstruction concept in the management context mainly from the value-chain perspective [e.g. 18, 50]. Studies considering the deconstruction of value propositions include Payne and Frow`s [16] single-case study, which focused on the deconstruction of value propositions using the business system framework. Lindič and Marques da Silva [49] correlated value propositions and innovation through a deconstruction process. In this study, we apply the deconstruction approach to the context of circular economy and focus on the strategic management of circular CVPs. This kind of analysis is missing in the literature on circular business models.

The Deconstruction Framework

Exploitation of the benefits of the circular product-as-a-service model requires rigorous and proactive strategic management decisions that are designed to preserve the value of the product-service mix across and after multiple use cycles [2, 3, 25, 26]. This requires rethinking value propositions for customers through the lens of circular economy principles [24, 32, 51]. Therefore, the current deconstruction framework integrates theoretical frameworks from the circular product-as-a-service model and CVP literature for a systematic and structured analysis of strategic customer value management. The framework focuses on describing the flow of a focal product within a single cycle, including stages before, during, and after usage and between use cycles — for example one rental cycle of a single product to a single customer. The aim of the deconstruction framework is to describe the service and value elements and customer value trade-offs that occur in each stage of a cycle.

Deriving from the circular product-as-a-service business model literature [e.g. 2, 3], the framework emphasizes two key approaches: the product-service integration and the use-orientation of the model. Concerning the former, the product-as-a-service model is decomposed into focal products and service elements that are then offered to the customer. In prior literature, products and services are considered as the main components of product-as-a-service models and are stated as critical to fulfilling customer needs [33].

Further, the framework aims to describe the use orientation of product-as-a-service models. In product-as-a-service models, fulfilling customer needs focuses on the use phase. The framework therefore decomposes the process of a customer using and a company providing a focal product. Previous studies have described this process in the PSS context. For example, Lim et al. [33] identified nine general PSS process steps based on diverse types of PSS cases and prior studies. The limitation with these process descriptions is that they do not consider the reusability of the products, by which we mean the repetitive nature of the process, in which the focal product is offered to and used by the next customer after each use cycle. In the PSS literature on use-oriented services, this is referred to as sequential use of products by different users [2, 3]. In the current framework, we follow the suggestion by prior studies and distinctively include a beginning, middle, and end of product use into the framework [33], and additionally broaden the existing frameworks by adding an intermediate stage to the process to take sequential use into account. Thus, the current deconstruction framework dissects the use orientation into stages that describe 1) the intermediate stage, i.e. the factors between use cycles; 2) the factors before usage, which incorporate preparative components prior to the actual use of products; 3) usage, which highlights the value in use facets; and 4) factors that carry on after usage of products. Additionally, second life of the product and material recycling [26] are included as complementary elements in the framework. Here, these elements are referred to as the product being detached from the use cycle to either another use function (e.g. second-hand product retail) or material recycling, if the product’s end-of-life is reached.

Based on the literature on strategic management of CVPs, the framework focuses on company positioning and structuring customer value [6, 9, 48]. First, company positioning is addressed, as the CVP is deconstructed by determining the locus of the value elements that include points of parity and points of differentiation [47]. In the framework, the value elements are determined by defining the key aspects that are either similar to competing actors or accelerate differentiation in each stage of a single product cycle. Previous studies have shown that CVPs in the circular economy tend to incorporate comparisons to linear models. Ranta et al. [14] state that circular economy CVPs highlight the contrast to linear models by communicating the value that is created when customers adopt novel circular innovations and solutions. This notion is demonstrated in the context of textiles by Fisher et al. [52], which suggests that customers tend to assess circular offerings using conventional criteria based on traditional, linear models. This statement derives from the suggestion that circular offerings such as the product-as-a-service model are relatively new and currently have a minor role in the markets, compared to the established linear offerings that dominate e.g. the textile industry [4, 19, 20]. Therefore, the framework includes an assumption that product-as-a-service CVPs tend to include value elements that compare circular models to traditional, linear models rather than drawing comparisons between competing circular product-as-a-service actors.

Finally, structuring customer value for strategic management is addressed in the framework, as the CVP is deconstructed from the trade-off perspective to customer value [6, 10, 48]. This includes identifying the company`s view of the customer`s perceived benefits that should be increased and the sacrifices that should be decreased at each stage of a single product cycle. Identifying and understanding these benefit-sacrifice trade-offs is particularly important for company competitiveness in the context product-as-a-service models, as they are substituting ownership-based models and can include novel types of customer value facets [1, 14, 43].

Methodology

We adopted a qualitative, multiple-case study approach to examine CVPs for the product-as-a-service model and to develop and validate the CVP deconstruction framework. A case study was chosen as a suitable research approach for studying CVPs in the circular economy, because the approach focuses on the characteristics of real-life events in a holistic way and takes the context of the events into consideration [53]. The textile and clothing industry was considered a relevant empirical setting for the case study from the perspective of the industry`s negative environmental impacts [20] and the evident need for industry transformation. Additionally, several product-as-a-service models have emerged in the textile market in recent years, enabling the investigation of existing cases.

Case Selection

We investigated seven cases involving Finnish companies from the textile industry (Table 1). The textile industry includes versatile products such as garments, household textiles, and furniture, most of which are applicable to offer as a service [19, 20]. The business cases included diverse settings of the textiles as a service, such as casual wear, workwear, and interior textiles. The case companies operate in either product-brand-owner or retailer roles. The case selection was limited to include use-oriented circular service business models which are mainly based on renting or leasing textile products. The case study approach was preferred, as the selected cases represent diverse contexts of the addressed phenomenon [53, 54]. We followed purposive sampling in the case selection, which allows analytical generalization of the case study [53], and selected both business-to-consumer (B2C) and business-to-business (B2B) cases to build a comprehensive view of deconstructing CVPs in the product-as-a-service model. In line with the purposive sampling approach, the cases were selected based on predetermined criteria: 1) companies with an established product-as-a-service business model in the selected domain, and 2) positive expectations about the data richness and content [55]. The cases were identified and the relevant contact persons contacted within four research projects, all of which included the aim of studying the strategic management of product-as-a-service models.

Data Collection

To investigate the CVPs of the case companies’ product-as-a-service models, we collected research data from multiple sources, including company interviews and workshops. Using several data sources allowed us to strengthen the case study evidence [53]. The data was collected from a continuum of four research projects, which allowed us to apply multiple data collection methods and organize follow-up conversations in certain cases to gain a more detailed view. This included a total of four company workshops and nine company interviews. In all, 10 case company representatives participated in the study. The data was collected in Finland during 2020–2022. All the workshops and interviews were recorded and transcribed.

The aim of the workshops was to collectively identify factors of product-as-a-service CVPs that were not initially obvious to either the participants or the researchers [56]. The workshops therefore followed a pre-prepared structure based on the themes identified in the product-as-a-service and CVP literature, but the process left room for redefining and moderating the logic of CVP deconstruction. Appendix 1 outlines the structure and themes of the workshops. In the workshops, company representatives actively participated in data production [56]; two of the authors participated as facilitators. The participants were first asked to deconstruct and describe the product use cycles and service elements. Second, they were asked to describe the benefits and sacrifices for the customer in each deconstructed element. This theme was further elaborated in a discussion between the participants and facilitators concerning the locus of CVP value elements and the required capabilities and resources. The workshop themes were visualized and documented during the workshops using the Miro online whiteboard tool.

The second data collection method included semi-structured interviews with one or two company representatives as interviewees. One or two researchers participated as interviewers. The interviews were semi-structured and followed a protocol [57] that encouraged flexible and open conversation, allowing the researchers to address specific details or themes raised by the interviewees. The aim of the interviews was to gain an understanding of the case companies` business model, product use cycles, service elements, and elements of the CVPs. Appendix 2 outlines the themes that guided the interviews.

Data Analysis

The data analysis was based on a qualitative content analysis method and thematic coding [57, 58]. We conducted several rounds of analysis, starting from recognizing patterns within the cases and continuing with a cross-case analysis [54]. We applied a directed approach to the content analysis [59], allowing us to use the existing research on product-as-a-service models and CVPs to guide our initial, thematic coding scheme. Directed content analysis was chosen for developing and validating the CVP deconstruction framework, as the aim of this approach is to validate or extend frameworks that are based on existing theories [59]. In the initial round of coding, the first author examined the transcribed data by writing memos about observations and categorizing data into tables and on the Miro whiteboard. The initial coding was then discussed and checked with other authors. In the next iterative rounds of coding, the first author continued analysing the data using the Nvivo qualitative data analysis software and returned to joint discussions with other authors to understand and agree on the categorizations. The directed content analysis offered both supporting and extending evidence to existing theoretical concepts concerning product-as-a-service CVPs, as stated by Hsieh and Shannon [59]. This is why during the analysis process, the researchers continuously discussed the nuances of the CVP deconstruction framework and iteratively elaborated, developed, and validated the framework. Additionally, the analysis provided a descriptive set of evidence of CVP deconstruction in the context of the textile industry.

Results

This section presents the results of the multiple-case study in the textile industry context. The findings are summarized in Table 2, which follows a similar structure to that suggested in the current CVP deconstruction framework for circular product-as-a-service models (see Fig. 1). Deconstruction of the product-as-a-service model CVPs is shown through the four stages of customers using and companies providing textiles: the stage between use cycles, the stage before usage, the stage of usage, and the stage after usage. Further, according to the current deconstruction framework, the locus of value elements, service elements, and key benefits and sacrifices are described for each of these stages.

Between Use Cycles

In the stage between the use cycles of the product-as-a-service model, accessibility to products was identified as one of the benefits and key points of difference compared to the linear models. Further, the perspective of temporality was described as integral, as the customer gains temporal access to the products instead of permanent ownership. The temporality aspect was specifically described to enable preserving the value of the products across multiple use cycles. Especially the B2C case companies described temporal access as a sustainable solution to quickly changing trends of fashion. B2B case companies focused more on highlighting enabling access to suitable products for specific customer needs at a specific moment – for example offering workwear that meets diverse seasonal requirements. Many respondents described that they incorporate a “no commitment required” statement to the product-as-a-service CVP and highlight moving away from ownership. Accordingly, the trade-off between accessibility and ownership emerged as a recurring theme in our data. A case company D respondent commented that the model is based on “making the products accessible to customers” and “offering an option for ownership.” The companies referred to the cultural barriers concerning ownership. According to a Case company B respondent, the “change in the mindset concerning what should be owned” is one of the key barriers to comparing the model with linear ones, which should be tackled in the CVP. Overall, sharing the products with other customers was discussed as a service element that enables temporal access.

Besides sharing, a service element of maintenance and refurbishing was identified as crucial in the stage between use cycles, as the textiles need to be washed, repaired, or remodelled in-between uses and when transferring the products from one customer to another. Here, reducing customers’ risks related to the condition of the products was highlighted as a core benefit. Many companies in our case study stated that the risks and responsibilities related to the condition of the product has shifted from the customer to the company in relation to traditional models, as in the product-as-a-service model the customer does not gain ownership of the product. On the other hand, distrust in the quality of the maintenance and refurbishing process was described as a sacrifice intended to be decreased. This distrust facet tends to embed especially concerns about the hygiene of textiles, deriving from the initial idea of sharing products with other customers. Many companies in our case study aim to decrease this sacrifice through communicating partnerships with professional cleaning and washing companies. For example, casual wear as a service model of Case company A includes service elements that are executed by an antibacterial processing treatment company and laundry operator to tackle the hygiene concerns of customers.

Before Usage

This stage highlights the preparation for the actual usage of products. At this stage, products (i.e., textiles) and the product selection offered to customers were identified as points of parity in the case companies’ CVPs. Points of parity were identified because the product selection of case companies in the textile industry does not significantly differ from the linear offerings in the market.

Here, the service elements include consultancy and delivery. Consultancy enables optimization of the selected products to the specific needs of the customer. What is specific to the product-as-a-service model is that these customer needs are likely to be temporal, and the product optimization process is aimed to fulfil short-term needs. For example, B2C case companies in the fashion field highlighted the enabled flexibility in varying styles or clothing sizes. For some case companies, consultancy was offered as a personalized service, for example by creating personal contacts with the customer during the fitting of clothing. For some case companies, the service was offered in a standardized manner, such as by offering pre-selected product recommendations or bundling product packages for various usage situations. For companies in a retailer role, the product selection itself includes consultancy elements related to the sustainability of product offerings. For example, Case company C has defined sustainability-related criteria for choosing fashion brands that are included in their product selection. Another respondent in a retailer role (Case company D) commented on this aspect as “the curated product sustainability” that seeks to optimize the suitability of product selection to the needs of the sustainability-oriented customer segment.

The incompatibility of product selection with customer needs emerged here as the sacrifice. For example, according to a Case company C respondent from the B2C field, the product selection is limited to a certain style of fashion, and this can lead to limited compatibility in terms of style preferences among certain customer groups. The case companies also described a specific shortage of the product-as-a-service model compared to ownership-based models: for the products to be efficiently circulated across multiple users and use cycles, they cannot be highly customized. For example, in the B2B context, Case company F described that some customers ask for highly customized workwear, which is very challenging to offer as a rent or lease. This is because once the textiles are, for example, highly modified to fit the visual requirements of a certain brand, they cannot be offered for other B2B customers without being heavily modified again. As this would be neither economically profitable nor environmentally sustainable, this scenario would prevent value from being preserved across use cycles and passed on to multiple customers. However, our results show that the case companies aim to compensate this shortage in product-related factors by offering and highlighting the service elements instead. The services are argued to be customizable, differentiate the product-as-a-service model from the linear models, and to be flexible enough to meet the specific needs of target customers.

The service element of delivery was described to include product pick-ups from a service point or logistics service, and these services are typically implemented by an intermediate actor. The case companies highlighted the benefits related to convenience. In addition to the benefits embedded in the utilitarian ease of delivery, also social convenience is linked to delivery. Communality is an example of social convenience, especially in the pick-up model in the B2C setting, in which social interaction takes place. The respondents of case companies that operate in a retailer role commented that the interaction that occurs between the company`s employees and customers in the product pick-up phase in the physical store forms a prerequisite to one of the key social benefits of the CVP. Overall, the case companies described the level of participation and engagement of customers as one of the key differences between product-as-a-service models and traditional models based on ownership. In product-as-a-service models, active customer participation is needed at multiple points along the use process. Compared to traditional models based on buying products and ownership, the product-as-a-service model requires more instances of delivery, as product leasing or renting is generally repetitive. Thus, the model requires more anticipation and planning from customers than do traditional, linear models.

Usage

Product usage was identified as a point of parity in relation to linear offerings, as the textile use per se is similarly associated in both models. Overall, enabling product use for customers was highlighted as a prerequisite for the existence of the model. The case companies described emotional, symbolic, and utilitarian forms of value in use. In the context of textiles, the usage of products incorporates benefits as means of self- or brand expression. In the consumer context, this was exemplified by a Case company C respondent: “[…] identifying oneself as the user of these clothes, expressing what kind of person I am […] Sharing with others that, for example, I used this piece at a wedding and this is how I looked.” Additionally, the utilitarian aspects of using textiles were highlighted. For example, in the cases of workwear as a service (Case company F) and children`s wear as a service (Case company E), technical product functionalities like product material durability are considered one of the key aspects. In contrast, the facet of insecurity was identified as a sacrifice. Related to the initial idea of not owning the products and sharing them with others, this facet manifests e.g. in uncertainties about the condition or quality of the products in use or worries over damaging the products.

Guidance on product use or assistance with problems occurring during product usage were identified as the supporting service elements. Offering guidance can give assurance to customers on the correct use of products and thus increase the benefits of the CVP. This was highlighted especially in cases where customers independently maintain (i.e., clean or repair) the products during the usage phase. Fluent handling of customers’ problems or requests for guidance, on the other hand, was seen to minimize the effort of seeking support and thus reduce the sacrifices involved.

After Usage

This stage portrays the elements that occur after actual usage of the products. The process-related aspects – more specifically the circularity of the product-as-a-service model – were highlighted as points of difference in contrast to linear models. The take-back logistics service as part of this stage is a corresponding element to the delivery service in the stage before actual usage. As with the delivery service, in take-back the convenience of the service was emphasized. Here, typically an intermediate actor handles the take-back logistics. Contrary to convenience benefits, temporality was described as a sacrifice, as take-back requires a customer to detach from the product. Some case companies aimed to decrease this sacrifice by promoting and enabling the claiming of rented products for ownership after cycles of use. For example, a Case company B respondent commented that “the customers can test and try the products by renting, and after that make a decision on buying.”

Product validation was identified as a service element that includes the inspection of product condition and documenting product- and use-related data. Product validation is a critical part of improving circularity and developing and validating environmental value propositions. This service element can include data gathering, e.g. on instances of use and length of the product lifecycle, necessary for verifying the sustainability of the model, and articulating (environmental) CVP. For example, Case company G communicates life-cycle assessment (LCA) calculations and related environmental data to their B2B customers for verification purposes. Additionally, product validation acts as a prerequisite for the product maintenance and refurbishing, as the product condition and need for repair and maintenance is defined here. Moreover, product validation can generate product narratives in the CVP, as the history of the product use and users can be narrated in the CVP. The verification of product narratives can emerge as a benefit, especially in the B2C setting. For example, Case company C communicates product-use-related narratives of casual wear rentals, which relates to “relationship-building and a sense of community among the same-minded customers,” as pointed out by a respondent. On the other hand, the data generated in product validation can interfere with the customer`s sense of privacy, which is identified as a sacrifice here. This was described as a sacrifice that is not necessarily applicable in ownership-based models and that might potentially be a barrier to some customers choosing the product-as-a-service model over traditional models.

Finally, lifecycle optimization was included in this stage. It ensures environmentally optimal arrangements for the model. Enabling product second life or material recycling are identified as the service elements that close the use cycle and potentially address another use function or end-of-life of a product. In a wider view, lifecycle optimization enables the product to circulate in the use-oriented loop in an environmentally friendly manner. A Case company G respondent commented on this from the perspective of material resources: “Minimizing textile and other waste throughout the process is highlighted.” A Case company C respondent stated that as a service element, the company ensures that “the textile is used up, with maximal instances of use.” For the customer, this service element offers convenience-related benefits in terms of enabling the environmental sustainability of the model. For example, Case company F, which operates in the B2B field, “takes care of the textile waste for the customer” as part of the service. According to a respondent, this is communicated by “making environmental sustainability easy for the customer.” The sacrifices tend to include questioning and distrust of the positive environmental impact and optimization of e.g. recycling practices, especially in comparison to ownership-based models.

Discussion and Conclusions

Product-as-a-Service Customer Value Propositions in the Textile Industry

In this section, we discuss the key observations and insights which emerged from the empirical results of our study. The qualitative case study provided a descriptive set of evidence of product-as-a-service CVPs in the context of the textile industry.

In disassembling the value elements of product-as-a-service CVPs in the textile industry, the findings showed that the CVPs include both points of difference (access and process) and points of parity (product and usage). These results indicate that product-as-a-service companies in the textile field seem to aim for a resonating focus type of CVP, which combines both recognizably different and similar value elements to alternative offerings in the market, with the aim of delivering value that is the most important to the customers [47]. Consistent with the frameworks drawn from the circular economy business model literature, another finding was that the resonating focus seems to be driven by the key underlying concepts of the product-as-a-service model. The CVP elements resonate with the principles of access-based consumption [e.g. 36, 37], sharing and collaborative economy [e.g. 35], and the use-oriented product-service systems, i.e., the product-service integration and the process of product usage [e.g. 2, 3]. Overall, the findings support the notion of value in use and shared value that are acknowledged in both the marketing and circular economy value proposition literature [e.g. 5, 14, 60].

The research question of this study was: How are CVPs strategically managed in circular product-as-a-service models? The strategic level of decision-making was addressed to which the company’s ability to deliver competitive customer value is central [6, 10]. For this purpose, the case study showed in detail how company competencies and resources connect to the benefits that the companies aim to increase and the sacrifices that are aimed to be decreased. From the circular economy perspective, two particularly interesting company resources emerged from the findings: the company`s capability to include intermediate actors in the circular value chain and the company`s capability to address sustainability factors. Overall, these resources are linked to the interdependencies in proposing value in the circular economy that includes the environment, society, customers, and stakeholders [31]. The findings suggest that intermediate actors that are included in e.g. the maintenance, delivery, and take-back service elements facilitate and take part in shared and co-created value propositions, and ultimately have an effect on the proposed benefits and sacrifices. This is what makes it critical for the focal company to have the ability to choose and integrate relevant intermediate actors into the process of proposing customer value.

Similarly, the company`s competence and resources in developing and validating environmental value propositions in the product validation and lifecycle optimization service elements were identified as relevant from the CVP point of view. In consideration of sustainability-related resources, it is important to acknowledge that in contrast to solely creating value, delivering circular value propositions may also destroy value in the sustainability context [5]. The idea of destroyed sustainability-related value was corroborated in the current empirical study in the identified benefit-sacrifice trade-offs. The resonation with sustainability was especially observed at the after-usage stage. In product validation, damaging customers’ sense of privacy as a sacrifice resonates with the social harm that the product-as-a-service model may cause in contrast to traditional, linear models.

While the use of circular PSS is suggested as a means of reducing environmental impacts compared to linear models, environmental benefits were not strongly present in our data. The environmental impacts of the product-as-a-service model compared to linear models were described to be unclear. While in an ideal product-as-a-service model the product is made as material- and cost-efficient as possible [2], in reality, many models are still in their infancy, and understanding actual environmental benefits may be limited [44]. The companies may choose to prioritize economic and business perspectives at the cost of environmental value creation at early stages of market entry, as shown in earlier research on use-oriented product-as-a-service models [61]. Circular CVPs emphasizing environmental value would benefit from more profound efforts on life-cycle optimization and environmental assessments, particularly as proposing unclear or unsubstantiated environmental claims may not only destroy customer trust but also lead to financial penalties for companies due to the strengthening of anti-greenwashing regulation [62]. On the other hand, successful utilization of sustainability-related capabilities can result in differentiation in comparison to linear offerings, which in the textile industry are often based on unsustainable options such as fast fashion.

The Customer Value Proposition Deconstruction Framework

In this paper, we introduced a framework for deconstructing CVPs of circular product-as-a-service business models. This section elaborates the theoretical implications of the framework.

The purpose of the CVP deconstruction framework is to offer an approach for systematically supporting the strategic managerial decision-making process of the circular product-as-a-service model. The framework addresses the strategic dimension of managing CVPs, which is acknowledged in prior CVP literature [6]. This study takes the existing CVP elements into the context of a circular product-as-a-service business, as frameworks from the CVP and circular product-as-a-service business model literature are integrated. Our empirical data indicates that the deconstruction process generates systematically arranged information and a granular view of the manageable components of CVPs of the product-as-a-service model. The proposed CVP deconstruction framework explores how the contextual characteristics of the circular economy are reflected in the strategic management of CVPs. In this way, the CVP deconstruction framework captures the contextual nature of CVPs [6, 8].

In this study, we adopted a normative stance initially suggested by Payne and Frow [16], according to which companies can change and enhance their competitive position by systematically examining their value propositions. The outlined framework is based on the deconstruction concept, which enables strategically redefining what the customers value [16]. In addition to dissecting the product-as-a-service CVPs, we suggest that the framework can support the redefinition when the CVP is reconstructed after deconstructing. Corroborating the hierarchical CVP model presented by Rintamäki et al. [10], we suggest that the core of reconstruction after deconstruction may be the selected primary focus of a competitive CVP. The framework can support companies in evaluating which elements of the CVP are most important in terms of competitive advantage and customer acceptance, i.e., which elements the competitive CVP is built upon, and which elements should be highlighted the most.

The aim of the outlined framework is to enable the reconfiguration of CVPs in a circular economy transition context. The market maturity and customer awareness of circular product-as-a-service models are currently low, and the position of these models is expected to change over time [4]. Changes in market dynamics are expected especially in markets that are undergoing drastic circularity transitions, such as the textile industry [19, 20]. For companies, these kinds of changes are likely to require enhancing the existing CVPs or developing new value propositions. In the textile industry, the position of the product-as-a-service models might change, for example, if the number of clothing rental retailers or platforms were to increase significantly in the market or many established textile brands were to expand their business models to offering products as a service as a secondary model. Similarly, for example, a significant increase in offering products that are exclusively offered via renting or leasing might potentially result in market position changes in the textile field.

In the circular economy, the CVP reconfiguration process should be continuous, as customers are being motivated to adopt the product-as-a-service offerings and move from linear to circular models. In line with this notion, the CVP deconstruction framework includes an assumption implying that in the circular economy, companies tend to include linear offerings as the comparison points in their differentiation strategies, instead of significantly comparing their offerings with other circular models. The findings of the current empirical study support this assumption. Overall, the assumption is based on the associated novelty of circular offerings in the markets. Furthermore, this assumption is in line with a recent study by Ranta et al. [14], which indicates that circular economy CVPs underline value creation opportunities that result from changing use practices from linear to circular, detaching from linear solutions, and adopting novel circular innovations. The underlying purpose of the CVP deconstruction framework is based on the consideration that market tendencies might change over time as the circular economy transition progresses, which could create incentives for changing the logic of building and articulating CVPs.

Managerial Implications

The prior literature has identified that CVPs often form the premises for re-inventing business models [7]. Thus, from a managerial perspective, the CVP deconstruction framework can be used as a tool for innovating product-as-a-service business models in the circular economy. Moreover, the framework can provide practical support for companies in improving or formulating new CVPs. One of the potential approaches to applying the CVP deconstruction framework could be circular business model experimentation. The framework could be integrated into the process of developing and testing circular value propositions in a real-life context [63]. Another application area for the CVP deconstruction framework could be circular service design. The framework could provide an integrated tool to investigate e.g. customer touchpoints within product use cycles in relation to CVP elements.

The CVP deconstruction framework could also be used as a supplementary tool with other established circular business model frameworks, such as the value mapping tool [5] or the environmental value proposition evaluation framework [46]. The CVP deconstruction framework can offer a more granulated view of these frameworks. For example, integration of the value mapping tool and the CVP deconstruction framework can offer an understanding of the value perspectives while shedding light on which use-orientation phase of the circularity value is being constructed.

Limitations and Future Research

The generalizability of the results of this study is subject to certain limitations. The empirical setting of the study was limited to certain applications of the textile industry. However, overall, the textile and clothing industry includes very diverse products, ranging from apparel to applications for medical or construction purposes [19], with potentially different structure and content of value propositions. Future research could explore the topic for a wider range of textile products or broaden the investigation to other domains and examine the similarities and differences of diverse settings. Further, the study focused on use-oriented product-as-a-service models. More research is needed to expand the investigation to other types of circular business models, such as product- and result-oriented models.

The CVP deconstruction framework could potentially be used as a practical tool for managers. However, it should be acknowledged that the presented framework can serve a different purpose — as a managerial business model tool for an individual company — from the one it serves for a multiple-case study. In this study, developing and validating the framework was executed as an iterative and parallel process. More research is required to validate the effectiveness and suitability of the tool in innovating and determining circular CVPs in managerial contexts. Future research could be executed by e.g. testing the framework as a practical business model tool in workshops with company representatives.

Finally, it should be acknowledged that the CVP deconstruction framework should be developed further in the future, as the circular product-as-a-service business models develop and understanding of CVPs in the circular economy is deepened. For example, changes in the product-as-a-service model positioning in the market could require alterations in the framework. Moreover, for example, a more profound integration of the ecosystem perspective in the circular economy could be included in the framework in future work. Furthermore, the integration and analysis of environmental aspects in the CVP deconstruction framework is still very limited and would benefit from further efforts. It should also be acknowledged that the deconstruction framework does not provide an integrated view of all the components of circular business models, which along with CVPs include e.g. value creation, value delivery, and value capture [e.g. 28]. Future research could broaden the framework by considering these business model components aside from circular CVPs.

Data Availability

The data collected for this study cannot be made available for wider use.

References

Kjaer L, Pigosso D, Niero M, Bech N, McAloone T (2019) Product/service-systems for a circular economy: the route to decoupling economic growth from resource consumption? J Ind Ecol 23(1):22–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12747

Tukker A (2015) Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy - A review. J Clean Prod 97:76–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.049

Tukker A, Tischner U (2006) Product-services as a research field: past, present and future. Reflections from a decade of research. J Clean Prod 14(17):1552–1556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.01.022

Egebæk K, Børglum Ploug Olsen A, Secher Kristensen I, Bauer B, Vanacore E, Diener D, Baxter J, Danielsen R, Sundqvist-Andberg H, Petänen P, Gíslason S (2022) Business models and product groups for Product Service Systems (PSS) in the Nordics: Final report. https://c814130a-8a73-4c55-8738-1795329751fd.filesusr.com/ugd/7b9149_9d810c9b8a1c4b00be34e62f12b1b31e.pdf. Accessed 8 December 2022

Bocken N, Short S, Rana P, Evans S (2013) A value mapping tool for sustainable business modelling. Corp Gov 13(5):482–497. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-06-2013-0078

Rintamäki T, Saarijärvi H (2021) An integrative framework for managing customer value propositions. J Bus Res 134:754–764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.05.030

Johnson M, Christensen C, Kagermann H (2008) Reinventing Your Business Model. Harv Bus Rev 86(12):50–59

Payne A, Frow P, Eggert A (2017) The customer value proposition: evolution, development, and application in marketing. J Acad Mark Sci 45(4):467–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0523-z

Anderson J, Kumar N, Narus J (2007) Value merchants: Demonstrating and documenting superior value in business markets. Harvard Business School Press, Boston

Rintamäki T, Kuusela H, Mitronen L (2007) Identifying competitive customer value propositions in retailing. Manag Serv Qual 17(6):621–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520710834975

Fernandes S, Pigosso D, McAloone T, Rozenfeld H (2020) Towards product-service system oriented to circular economy: A systematic review of value proposition design approaches. J Clean Prod 257:120507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120507

Haase L, Lythje L, Jensen P (2023) Designed to last: reframing strategies for designing value propositions that support product longevity in 17 best practice companies. Circ Econ Sust. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-022-00244-z

Müller M (2012) Design-driven innovation for sustainability: A new method for developing a sustainable value proposition. Int J of Innov Sci 4(1):11–24. https://doi.org/10.1260/1757-2223.4.1.11

Ranta V, Keränen J, Aarikka-Stenroos L (2020) How B2B suppliers articulate customer value propositions in the circular economy: Four innovation-driven value creation logics. Ind Mark Manag 87:291–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.10.007

Santa-Maria T, Vermeulen W, Baumgartner R (2021) Framing and assessing the emergent field of business model innovation for the circular economy: A combined literature review and multiple case study approach. Sustain Prod Consum 26:872–891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2020.12.037

Payne A, Frow P (2014) Deconstructing the value proposition of an innovation exemplar. Eur J Mark 48(1/2):237–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2011-0504

Hopkinson P, Zils M, Hawkins P, Roper S (2018) Managing a complex global circular economy business model: Opportunities and challenges. Calif Manage Rev 60(3):71–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125618764692

Bresser R, Heuskei D, Nixon R (2000) The deconstruction of integrated value chains: practical and conceptual challenges. In: Bresser R, Hitt M, Nixon R, Heuskei D (eds) Winning Strategies in a Deconstructing World. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp 1–22

European Commission (2022) EU Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0141#footnote5. Accessed 1 September 2022

Niinimäki K, Peters G, Dahlbo H, Perry P, Rissanen T, Gwilt A (2020) The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat Rev Earth Environ 1:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9

Ellen Mac Arthur Foundation (2022) Fashion and the circular economy. Deep Dive. https://archive.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/explore/fashion-and-the-circular-economy. Accessed 24 January 2022

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/publications/a-new-textiles-economy-redesigning-fashions-future. Accessed 30 September 2022

Geissdoerfer M, Pieroni M, Pigosso D, Soufani K (2020) Circular business models: A review. J Clean Prod 277:123741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123741

Bocken N, De Pauw I, Bakker C, Van Der Grinten B (2016) Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J Ind Prod Eng 33(5):308–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681015.2016.1172124

Geissdoerfer M, Morioka S, de Carvalho M, Evans S (2018) Business models and supply chains for the circular economy. J Clean Prod 190:712–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.159

Nußholz J (2017) Circular business models: defining a concept and framing an emerging research field. Sustainability 9:1810. https://doi.org/10.3390/su910181

Grönroos C (2001) The perceived service quality concept–a mistake? Manag Serv Qual 11(3):150–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520110393386

Bocken N, Short S, Rana P, Evans S (2014) A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. J Clean Prod 65(2):42–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.039

Urbinati A, Chiaroni D, Chiesa V (2017) Towards a new taxonomy of circular economy business models. J Clean Prod 168:487–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.047

Yrjölä M, Hokkanen H, Saarijärvi H (2021) A typology of second-hand business models. J Mark Manag 37(7–8):761–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2021.1880465

Antikainen M, Valkokari K (2016) A Framework for Sustainable Circular Business Model Innovation. Technol Innov Manag Rev 6(7):5–12. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1000

Lüdeke-Freund F, Gold S, Bocken N (2019) A review and typology of circular economy business model patterns. J Ind Ecol 23(1):36–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.12763

Lim C-H, Kim K-J, Hong Y-S, Park K (2012) PSS Board: a structured tool for product–service system process visualization. J Clean Prod 37:42–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.06.006

Van Der Zwan F, Bhamra T (2003) Services marketing: taking up the sustainable development challenge. J Serv Mark 17:341–356. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040310482766

Belk R (2014) You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J Bus Res 67(8):1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

Edbring E, Lehner M, Mont O (2016) Exploring consumer attitudes to alternative models of consumption: motivations and barriers. J Clean Prod 123:5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.107

Mont O, Plepys A (2008) Sustainable consumption progress: should we be proud or alarmed? J Clean Prod 16(4):531–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.01.009

Becker-Leifhold C, Iran S (2018) Collaborative fashion consumption – drivers, barriers and future pathways. J Fash Mark Manag 22(2):189–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-10-2017-0109

Mukendi A, Davies I, Glozer S, McDonagh P (2020) Sustainable fashion: current and future research directions. Eur J Mark 54(11):2873–2909. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0132

Armstrong C, Niinimäki K, Kujala S, Karell E, Lang C (2015) Sustainable product-service systems for clothing: exploring consumer perceptions of consumption alternatives in Finland. J Clean Prod 97:30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.01.046

Zamani B, Sandin G, Peters GM (2017) Life cycle assessment of clothing libraries: can collaborative consumption reduce the environmental impact of fast fashion? J Clean Prod 162:1368–1375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.128

Patala S, Jalkala A, Keranen J, Vaisanen S, Tuominen V, Soukka R (2016) Sustainable value propositions: Framework and implications for technology suppliers. Ind Mark Manag 59:144–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2016.03.001

Matschewsky J (2019) Unintended circularity?—assessing a product-service system for its potential contribution to a circular economy. Sustainability 11(10):2725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11102725

Roman P, Thiry G, Muylaert C, Ruwet C, Maréchal K (2023) Defining and identifying strongly sustainable product-service systems (SSPSS). J Clean Prod 391:136295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136295

Kjaer L, Pigosso D, McAloone T, Birkved M (2018) Guidelines for evaluating the environmental performance of Product/Service-Systems through life cycle assessment. J Clean Prod 190:666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.108

Manninen K, Koskela S, Antikainen R, Bocken N, Dahlbo H, Aminoff A (2018) Do circular economy business models capture intended environmental value propositions? J Clean Prod 171:413–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2017.10.003

Anderson J, Narus J, van Rossum W (2006) Customer value propositions in business markets. Harv Bus Rev 84(3):1–11

Zeithaml V (1988) Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J Mark 52(3):2–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/1251446

Lindič J, Marques da Silva C (2011) Value proposition as a catalyst for a customer focused innovation. Manag Decis 49(10):1694–1708. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741111183834

Feng L, Whalley J (2002) Deconstruction of the telecommunications industry: from value chains to value networks. Telecomm Policy 26(9/10):451–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-5961(02)00056-3

Centobelli P, Cerchione R, Chiaroni D, Del Vecchio P, Urbinati A (2020) Designing business models in circular economy: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Bus Strat Env 29:1734–1749. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2466

Fisher T, Cooper T, Woodward S, Hiller A, Goworek H (2008) Public Understanding of Sustainable Clothing: Report to the Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs. DEFRA, London. http://www.defra.gov.uk/environment/business/products/roadmaps/clothing/documents/clothing-action-plan-feb10.pdf. Accessed 11 March 2022

Yin R (2018) Case study research and applications: design and methods. Sage Publications, Los Angeles

Eisenhardt K, Graebner M (2007) Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad Manag J 50(1):25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.24160888

Flyvbjerg B (2006) Five misunderstandings about case study research. Qual Inq 12(2):219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Ørngreen R, Levinsen K (2017) Workshops as a Research Methodology. Electron J e-Learn 15(1):70–81

Saldaña J (2011) Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. Oxford University Press, New York

Flick U (ed.) 2017 The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications, London

Hsieh H-F, Shannon S (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Eggert A, Ulaga W, Frow P, Payne A (2018) Conceptualizing and communicating value in business markets: From value in exchange to value in use. Ind Mark Manag 69:80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2018.01.018

Sundqvist-Andberg H, Tuominen A, Auvinen H, Tapio P (2021) Sustainability and the contribution of electric scooter sharing business models to urban mobility. Built Environ 47(4):541–558(18). https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.47.4.541

European Commission (2023) Proposal for a directive of the european parliament and of the council on substantiation and communication of explicit environmental claims (Green Claims Directive). COM/2023/166 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2023%3A0166%3AFIN. Accessed 23 March 2023

Bocken N, Weissbrod I, Antikainen M (2021) business model experimentation for the circular economy: definition and approaches. Circ Econ Sust 1:49–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-021-00026-z

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the project research partners, companies who were willing to open up their cases to research. An early, work-in-progress version of this paper was presented at the Spring Servitization Conference 2022. The authors would like to thank research scientist Jouko Heikkilä for his work and comments on the early stages of conducting this study.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Technical Research Centre of Finland. The study was carried out as part of the PaaS Pilots research project, funded by the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra; the Telaketju2 research project, funded by Business Finland; the PSS in the Nordics research project, funded by the Nordic Council of Ministers; and the FUTEX research project, funded by a government grant received by VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author planned the study concept and design, collected the data, performed data analysis, and wrote the article manuscript. The second and third authors contributed to the data collection, provided feedback for the research process, and contributed to the article manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

No ethics approval is required for this study.

Consent to Participate and Publish

Consent to participate and publish was obtained from the participants in this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Themed structure for company workshops

Figure 2

Appendix 2 Theme guide for company interviews

Background Information

-

What is the business idea of the company?

-

What is your (i.e., the interviewee) role in the company?

-

Is offering products as a service a primary or secondary model for the company?

-

What are the main drivers for the company to offer products as a service?

Products, Services and Use Cycles

-

What is included in your product-as-a-service offering; what are the products and the services?

-

Is there a service package: are some of the services always included in the package, or are some optional to be chosen by customers?

-

-

How are the services organized?

-

Do you involve intermediate actors?

-

-

How do the products circulate and how are they used?

-

What happens to products after use cycles?

Customers, Benefits and Sacrifices

-

What are the customer segments that you are targeting? Why?

-

What are the benefits for customers related to your offering?

-

What drives and motivates customers?

-

-

What are the sacrifices for customers related to your offering?

-

What are the barriers for customers?

-

-

How do you persuade customers to choose your offering?

-

How do you aim to increase the benefits and decrease the sacrifices?

-

-

Which service elements are critical for the customers in relation to key benefits to be increased and key sacrifices to be decreased?

Differentiation and Positioning

-

Who do you consider to be your competitors in the market?

-

How do you differ from your competitors?

-

What is similar in your offering compared to other actors in the market?

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Petänen, P., Sundqvist, H. & Antikainen, M. Deconstructing Customer Value Propositions for the Circular Product-as-a-Service Business Model: A Case Study from the Textile Industry. Circ.Econ.Sust. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-024-00351-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43615-024-00351-z