Abstract

Circular economy (CE) discourse primarily focuses on business-as-usual and resource-related economic processes whilst overlooking relational-spatial aspects, especially networking for local development. There are, however, many mission-driven social enterprises (SEs) engaging in short-loop activities at the neighbourhood and city scales (e.g., reuse, upcycling, refurbishing or repair). Such localised activities are often overlooked by mainstream policies, yet they could be vital to the local development of the CE into a more socio-environmentally integrated set of localised social structures and relations. This paper examines the role of SEs, their networks and structures in building a more socially integrated CE in the City of Hull (UK). Drawing upon the Social Network Analysis approach and semi-structured interviews with 31 case study SEs representing variegated sectors (e.g., food, wood/furniture, textiles, arts and crafts, hygiene, construction/housing, women, elderly, ethnic minorities, homeless, prisoners, mentally struggling), it maps SEs’ cross-sector relationships with private, public and social sector organizations. It then considers how these network constellations could be ‘woven’ into symbiotic relationships between SEs whilst fostering knowledge spillovers and resource flows for the local development of a more socially integrative CE. We contend that integrating considerations of SEs’ organizational attributes and their socio-spatial positioning within networks and social structures offers new insights into the underlying power-relations and variegated levels of trust within the emergent social-circular enterprise ecosystem. These aspects are presented in the form of a comprehensive heuristic framework, which reveals how respective organizational and network characteristics may impact SEs’ performance outcomes and, ultimately, a more integrated approach to local CE development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rooted in concepts of resource efficiency and cleaner production, the circular economy (CE) concept primarily focuses on business-as-usual and resource-related economic processes whilst overlooking the important role of relational-spatial elements, including the construction of social networks in situ, in the local development of the CE [1,2,3,4]. The latter is understood here in terms of local regenerative practices that minimise resource inputs, waste, emissions and energy leakage, thereby ‘slowing, closing, and narrowing material and energy loops through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling’ (p.6) [5]. Many CE practices, especially those that ‘shorten loops’ (i.e., extend product, as opposed to material, life, e.g., re-use/sharing), are run by a broad range of social enterprises (SEs), which provide both symptomatic support to aid vulnerable individuals (satisfying basic social needs), and/or systemic support to address individual and social/environmental challenges (e.g., they may run inclusive work integration schemes, and improve human health by promoting environmental stewardship). In this paper, SEs are regarded as alternatives to conventional enterprises in that they reinvest profits to fulfil a social and/or environmental mission rather than distributing them among shareholders [6]. Although SEs often have limited resources (thus their development is often constrained) [7], resource scarcities foster socially innovative and inclusive networking alongside circular ways doing and procuring materials and resources (e.g., by using second-hand materials). As such, SEs can perform a vital role in the social and systemic integration [8] of material, environmental and social elements of the CE at the local scale. This is even more important as they help to ‘restore community solidarity’ (p.1427) [9], as well as form, capitalize on and act as conduits for, social capital. SEs can thus enrich the CE concept with a social dimension, which remains underrepresented in the existing CE literature [2, 10].

Despite growing research on inter-/intra-organizational networks in the context of the CE [11,12,13,14], very few studies have investigated SE networks in local CE development. And yet, SEs form both formal (i.e., supported by legal agreements and contracts) and informal (i.e., concerning friends and relatives) networks of interdependent and interconnected actors across social, public and private sectors in order to access necessary materials and serve local communities. SE networks constitute important transmission channels for lubricating flows of (in)tangible resources across mainstream (i.e., formal/regulated) and alternative (i.e., informal/unregulated) spaces of the local CE [10]. This article regards SEs as important actors for building a socio-environmentally integrative CE at the local scale whereby disadvantaged groups of people are both directly and indirectly empowered and/or aided through engagement in the production and/or consumption of products and services that embody CE thinking and practice. In this sense, such an integrative approach de facto also constitutes a socially inclusive approach to local CE development [10].

Empirically, the paper examines the emergent SE-driven CE network in an urban setting—the City of Hull, UK. Drawing upon the Social Network Analysis approach and semi-structured interviews with 31 Hull-based SEs spanning variegated sectors (i.e., food, wood/furniture, clothing and other textiles, arts and crafts, hygiene, construction/housing, electronics and mixed/other in terms of materials), including those distinguished on the basis of client/social beneficiary (i.e., women, elderly, ethnic minorities, homeless, prisoners, ex-offenders, mentally struggling, vulnerable youth, children, refugees and asylum seekers, unemployed, women, alcohol addicts), it maps cross-sector and locality-based network relationships with private, public and social sector organizations. In doing so, the paper seeks to uncover hitherto under-investigated social-spatial and relational aspects of the CE, including localised social structures and power relations underlying (collaborative) generation of distributional benefits associated with CE practices [1,2,3, 9, 14, 15]. It aims to answer the following research question: what network constellations and organizational characteristics underpin the CE and how could they be (re)constructed in order to promote local development of the socially and environmentally integrative CE? Notably, this study seeks to uncover ‘ego-networks’ [16], i.e., (in)formal ties of each enterprise forming the broader SE landscape in a particular city whilst also scrutinizing and conceptualizing the diversity of factors underpinning the broader network interactions in the CE. It further investigates how SEs could build what Baker (2014) defined as ‘new pipes’ (i.e., connections facilitating or constraining resource flows), and use those new or already existing pipes to develop and/or diffuse circular practices across the city [17]. The research not only examines locally emergent SE networks but considers how existing network constellations embody—and could be potentially reconstructed to embody—symbiotic relationships between environmentally, CE-, socially and/or commercially oriented enterprises to build a more integrative CE at the local scale. It then makes claims on how the use of new pipelines (actor-networks) could create novel local impact pathways and community infrastructure comprising shared values, resources, capabilities, interests, identity and needs in a geographically bounded space.

The article is organized as follows: first, it introduces and conjoins some of the key aspects from the literature on (social) entrepreneurship and network theory with the concept of the CE. Next, it provides contextual information on the City of Hull—an industrial port city in northern England with high levels of socio-economic deprivation—and describes the methods used. The third section presents and interrogates research findings in the light of relevant concepts and theories whilst visually unveiling the broader social circular enterprise ecosystem in a given spatial–temporal context. This section further offers a comprehensive heuristic framework illustrating how interlinkages between respective aspects may impact SEs’ performance outcomes and ultimately the local development of an integrative CE wherein local social and environmental benefits are disseminated and realized throughout the emergent CE ecosystem. Finally, we conclude by reflecting on how the adopted relational-spatial approach uncovers the underlying social structures and power relations crucial for a socially and systemically integrated approach to local and SE-led CE development.

Social Enterprise Networks and the Local Development of Integrative CE

SEs differ from traditional non-profits by having a trading arm and being, at least to some extent, financially independent from external funds. SEs generally seek to maximize social impacts by reinvesting profits to fulfil a social and/or environmental mission [6]. In this study, SEs primarily encompass charities with on mission trading arm and commercial enterprises (these can be ‘solo-entrepreneurs/sole-traders’) [18]. Although sole-traders are entitled to keep all profits after tax has been paid, in this study their businesses are referred to as SEs because they produce and sell items that embody social and/or environmental value. When using the term integrative CE we generally indicate the integration of production and consumption processes of products and services that embody CE-thinking with those that support participation of disadvantaged, socially excluded and vulnerable groups of people who are facing unequal access to housing and other physical or financial resources and opportunities (e.g., handicapped, elderly, or those seeking to escape abuse). Such activities may not only empower those individuals and improve their livelihoods, but also extract the highest possible value from resources through their recirculation, including upcycling and generation of performance-oriented products and services.

Crucially, the potential for SE-driven CE activity to contribute to the development of an integrative CE at the local scale remains unexplored, notwithstanding an emerging body of research in territorial aspects/factors underpinning the CE. Those territorial aspects condition how CE development is operationalized at multiple scales (e.g., local, city, regional) through multi-scalar interactions and coordination efforts [cf.19, 20, 21, 22]. And yet, adopting such an approach may further empower local authorities to use the CE as a means of conjoining hitherto separate policy interventions relating to decentralization reforms, local economic development and social sustainability. Such a combination of policy interventions around the SE-driven CE could allow to obtain socially advantageous circular development outcomes.

Since there is a deficit of studies investigating SE networks’ role in local CE development, this paper emphasizes the role and potential of such networks in driving a transition towards a more integrative CE that embodies a social dimension in a local development context. This is even more important given that SEs form networks that may span diverse geographies and sectors, and come into play as an organizing principle enabling SEs to work across many sectors and spatial scales [23, 24]. By establishing connections (ties) with other entities, SEs can obtain not only (in)tangible resources at a lower cost than they could be obtained on markets (e.g., production inputs and advice), but also those resources that are contingent upon social interactions (e.g., reputation and referrals) [7]. Since many studies focus on individual entrepreneurs’ networks rather than the broader ecosystem in which they are embedded [25], this study positions respective SEs within a broader network and its constituent geographical scales. This is in line with Salancik’s (1995) call to acknowledge the way organizations’ actions are organized: ‘There is a danger in network analysis of not seeing the trees for the forest. Interactions, the building blocks of networks, are too easily taken as given’ (p.355) [26]. Such a broader perspective is consistent with Giddens’ (1984) notion of structuration wherein social and system integration depends on the reciprocal interplay of agency (in this case, SE networking) and structure (e.g., the citywide CE ecosystem) in a localized setting [8]. Demonstrating the collaborative efforts of those SEs that rely on financial grants is also increasingly appreciated among donors who become more specific in their funding conditions [27].

Prior research on networks has been influenced by a range of disciplines and theories [28]. Certain aspects of social network analysis, which are usually researched in the context of entrepreneurship, concern network heterogeneity, centrality and positionality. Some of these structural aspects are explored in this study through the lens of the local CE development. Since they are to some extent interlinked and mutually reinforcing, some structural aspects of networks can help to explain the power dynamics underpinning structural network configurations. We now briefly explain the significance of the selected network constructs for the entrepreneurial processes and their novel implications for investigating the local development of the CE in a socially deprived urban setting.

Network Heterogeneity, Tie Content and Organizational Attributes

A heterogenous network has a diversity of nodes that differ in terms of their functions and utility [28]. This has implications for the diversity of behaviours and activities within a given entrepreneurial network. In this study, we assume that high network heterogeneity can lead to more circularity depending on the network content and the broader socio-spatial context in which it is embedded. Whilst the content of ties (i.e., (in)tangible resources subject to flows between nodes) and the content of nodes (i.e., attributes of network actors, including their capabilities and key assets) are not structural network characteristics per se, they influence, and are influenced by, network heterogeneity. In other words, some of the endogenous variables that may determine, to varying degrees, network heterogeneity concern intra-organizational differences relating to size, antecedents, age, development stage (which is in turn often correlated to size), demographics, capabilities, mission or motivations of organizations under scrutiny [29, 30]. These variables may translate into differential organizational needs and forms, which determine and guide formation of particular ties and hence resource flows (e.g., financial capital, emotional support, reputation). They also help to challenge the assumption that organizations with larger and more diverse networks are not necessarily more successful than those with less diverse connections [25]. This is because particular organizations may have different intentions, aspirations and capabilities, among other factors. At the same time, we show that the more heterogeneous network structure is, the more heterogeneous knowledge it possesses. Heterogeneous network content may be thus associated with greater innovative potential [31], including capacity to implement CE practices.

An important attribute of ties that may have implications for the diffusion of CE thinking and practice concerns their strength. Drawing upon Granovetter (1973) [32], Aldrich and Zimmer (1986) highlighted that ties can be either strong or weak ties depending on the ‘level, frequency and reciprocity of relationships between persons’ (p.11) and, more broadly, social capital reflecting social proximity [33]. Strong ties are characterized by high time and energy investments to build and maintain them. This is contrary to weak ties that may be the result of resource scarcity (e.g., time to build profound connections) and, more broadly, limited relational capabilities. Weak ties may be, however, a valuable source of new and diverse (rather than in-depth) information [32], thus potentially stimulating diffusion of CE ideas.

Positionality

Positionality of actors in a particular social network configuration is an important network characteristic that has an impact on resource flows, which, in turn, affect entrepreneurial outcomes and organizational performance [32, 34]. In other words, positionality can either facilitate or constrain access to necessary resources, hence influencing organizations’ ability to generate social-circular innovations. Linked to this, positionality is associated with particular levels of power. For example, there may be a correlation between the strongly central position of a given actor in a network and its level of power in that network [35]. Positionality is associated with network heterogeneity because having ties to, or the potential to establish ties with, a wide range of actors may facilitate access to vital resources, including those that are necessary for the local development of the CE. Crucially, it may be understood in terms of social and geographical proximity that tend to mutually reinforce one another.

Spatial proximity

Spatial location is rarely incorporated into the studies of networks [36]. And yet, considerations of geographical proximity are important from the perspective of the CE because circular activities are often deemed sustainable when they occur at the local level such that spatial distances between economic spaces of procurement, production, exchange and consumption are significantly reduced, and hence negative environmental externalities lessened [37]. In a similar vein, adoption of the systemic properties of, for example, a wider societal system such as the CE, often depends on the nature of social interactions between co-located social actors within a specific geographical locale—place, city or region [8, 38]. In addition to environmental advantages, co-location may facilitate information and knowledge spill overs [39]. Adopting such perspectives when analysing social circular enterprise ecosystem can enable to better evaluate the impact of spatial aspects on the performance of SEs and ultimately local development of the CE.

Network Centrality and Brokerage

Network centrality is defined as the total distance of a central actor to others in the network and the total number of other nodes a central individual can reach [33]. It hence indicates the power to access (or control) vital resources through direct and indirect ties [32]. Degree centrality involves the ability of network actors to connect with others through intermediaries. Actors with high degree of centrality (i.e., extensive links to other parts of a network) can be therefore vital communication channels between disconnected actors. The case where particular network members can quickly and (in)directly reach one another without relying on intermediate people is termed centrality closeness by social network analysts [33]. The case where central actors are located on the information paths between other network actors is called centrality betweenness and enables to detect bridging organizations that link, and could link, one part of the network with another, i.e., bridge structural holes [25]. Such bridging organizations can be referred to as brokers, i.e., as ‘organisations (or persons) that assist firms in the eco-innovation process by providing external impulse, motivation, advice and other specific support often by acting as an agent or broker between two or more parties’ (p.3) [40]. Positionality-related aspects of such brokers need to be acknowledged as the ties they form/connect may enable to foster and/or diffuse innovations when brokers maintain ties to many diverse and loosely linked actors [41]. It may be, however, costly to maintain bridging ties due to limited resources such as time, or lack of geographical proximity and external shocks. As brokers can control information flow, they need to be also regarded as trustworthy and impartial to be able to forge new connections and try to bring innovative (circular) ideas forward [34]. Crucially, some of the brokered connections may be also conducive to the rise of the so-called network spreaders, i.e., those agents that ensure efficient spread of knowledge and information whilst optimizing the use of available resources [42], hence impacting diffusion and adoption of innovations. In this research they are referred to as circular irrigators that (have the potential to) irrigate the broader social-circular enterprise ecosystem with circular thinking and practice.

Methods and Case Study

This research investigates the SE ecosystem in Hull—an industrial port city in the England with a metro area population of 323,000 and bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire [43]. After suffering heavy damage in the Second World War and going through a period of post-industrial decline that involved collapse of fishing and shipping industries [44], the city is presently characterized as ‘structurally disadvantaged’ [45] in that the local fabric of organizations and institutions contains an embedded bias whereby some members have a relative advantage whilst others are marginalized. Investigating SEs in the context of the local development of the CE in this structurally disadvantaged city thus provides a novel opportunity to address complex socio-environmental issues that are not sufficiently addressed in mainstream approaches to the CE led by public and private sector organizations. This is further evidenced by the fact that in 2019 the city ranked as the 4th most deprived local authority (out of 326) in England and as the 5th local authority in the UK with the highest proportions of children and older people in income deprivation [46]. According to the Index of Multiple Deprivation the city ranked nationally as the 4th most deprived city under the ‘Education, Skills & Training’ domain; 6th under the ‘Income’ domain; 6th under the ‘Crime’ domain and 7th under the ‘Employment’ domain [47]. The city’s low rates of employment are unparalleled in comparison to its neighbouring local authorities. See Map 1 below to view large concentration of Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs) Footnote 1 with high levels of deprivation across 21 wards in Hull.

Lower Layer Super Output Areas (LSOA) deprivation in Hull by national decile and according to The Index of Multiple Deprivation (2019) [47]

The locality also has high levels of deprivation in the eastern part of the city (e.g., Marfleet ward) as reflected in the presence of the UK’s most severe ‘food desert’, i.e., an area that lacks access to fresh and healthy food products [48]; 9,3% of the Hull’s population also receives Employment and Support Allowance/Incapacity Benefits, the latter being for mental and behavioural disorders [49]. Such highly deprived areas of the city are further characterized by poor environmental quality [50]. In terms of local economic development policies, Hull City Council (HCC) has developed innovative carbon offset projects to inward investment [51] and is also in the process of promoting the local development of renewable energy and formulating a strategy for the CE in the city [52]. Exploring the SE ecosystem in the city through the lens of the CE is thus highly relevant; especially given that future strategies for the CE are likely to prioritize mainstream industry sectors, potentially overlooking the causal significance of the city’s SE sector, which strives to improve the quality of life of Hull’s most deprived residents [cf.52].

This research combines qualitative and quantitative social research methods. It adopts the Social Network Analysis (SNA) approach [16] to analyse, both qualitatively and quantitatively, ego-networks of 31 selected enterprises (i.e., nodes), which constitute a putative social circular enterprise ecosystem in Hull. Since 31 out of 40 SEs, which agreed to participate in the study (out of approximately 74 contacted SEs that were identified using snowball sampling and online search), were mapped, the resulting map (Fig. 1 presented in Results and Discussion section) is not exhaustive, but strongly indicative. The data was obtained through semi-structured interviews with 31 SEs (see Table 1 below), 6 Hull-based support infrastructure organizations, 1 support infrastructure organization based in London (i.e., Charity Retail Association) and 3 policy makers from the HCC. Following Table 1, SEs were categorized into the following key 8 material resource-based clusters/categories: (1) food, (2) furniture, (3) clothing and other textiles, (4) arts and crafts (wooden/textile/cardboard/other), (5) construction/housing, (6) hygiene, (7) electronics and (8) mixed/other (in terms of materials). Some categories were, however, distinguished on the basis of client/social beneficiary (e.g., elderly, disabled). Other less dominant categories represented by the same SEs, and which were likewise distinguished on the basis of client/social beneficiary, are as follows: mentally struggling; ethnic minorities; homeless; ex-offenders; prisoners; vulnerable youth; children; refugees and asylum seekers; unemployed; women and alcohol addicts. Such an overview of categories highlights the importance of cross-cluster linkages for the local development of an integrative CE.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted either in person (a total of 17 interviews with SEs and 2 with SIOs) or online via Zoom or Microsoft Teams (a total of 14 interviews and 2 with SIOs), between November 2019 and May 2021. Interviews lasted approximately 60 min each and were transcribed and coded. Interviews explored the following key themes: (1) SEs’ historic background, motivations, mission, experiences and activities; (2) their embeddedness within the city and local community; (3) organizational/legal forms; (4) their knowledge of CE practices and policies; (5) their links to social, private and public sector organizations; (6) opportunities and challenges associated with existing activities, networks and alliances; (7) SE mission and vision of the future; and (8) the broader regulatory, socio-economic and environmental contexts in which SEs are embedded. The interviews provided a detailed understanding of the functioning of selected SEs in terms of mobilization of human and financial capital as well as material resources. Overall, semi-structured interviewing helped to uncover and understand what lies behind any phenomenon about which there is not much knowledge [53] by obtaining in-depth qualitative data, which have high explanatory potential (e.g., regarding underlying beliefs and subjective perceptions of respective ties; power relations and levels of trust between respective interacting/transacting entities; and other underlying causal relationships surrounding respective organizations) [54, 55].

The interviews were complemented with secondary resources such as social media websites of respective enterprises that enabled to further identify ties. Identified ties were then transferred into a matrix in Excel spreadsheets and converted into a graph using online kumu.io software, which additionally enabled to calculate degree centrality, centrality closeness and betweenness. Nonetheless, in using ‘organization’ as a unit of analysis, this research did not account for individuals that may be recipients and/or suppliers of particular (secondary) resources (e.g., individual food donors). Some of the SE managers were also unwilling to share all the names of their connections due to confidentiality reasons and time constraints. Overall, the network map generated (Fig. 1) is not representative of the entire social-circular enterprise ecosystem in Hull. Instead, it provides a snapshot in a given spatial–temporal context. Moreover, since SNA is data-intensive, the lack of data over a specific period of time implies that the generated map of ties does not reveal how size and shape of inherently dynamic networks have been evolving over time. Some of the mapped ties are thus temporary (though they may occur periodically over an extended period of time), especially when it comes to SE engagement with funding bodies. In any case, although such ties are to some extent incoherent, they serve to show the broader picture and delineate key patterns. Besides, whilst the most important collaborations were presumably identified by the interviewees, it cannot be ignored that some of the weaker, unidentified ties could, in fact, lead to CE innovations and diffusion of CE thinking across the wider network. As far as past connections are concerned, such information is especially difficult to retrieve from ‘mental archives’ of research participants [56], some of whom did not necessarily work for a given SE since its conception. Lastly, another SNA-related issue concerns legacy meaning that the co-created social network map requires maintenance and updates to render further benefits in the future.

Results and Discussion

This section is organized around some of the key themes emerging from the network analysis and coding of the interviews. It examines the main network characteristics that impact the actual and potential diffusion of CE thinking and practice across the local development context (i.e., social-circular enterprise ecosystem) in Hull. We first outline broader network characteristics and then examine specific case study enterprises (outlined in Table 1) to explore cause and effect between emerging themes and factors for local CE development. Figure 1 depicts ego-networks of 31 selected SEs—the building blocks of the broader SE ecosystem in Hull existing at the time of study (November 2019–May 2021). Case study enterprises have numerical values attached, which correspond to numbering of respective SE names in Table 1.

Social circular enterprise ecosystem in Hull, UK (results from July 2020 to May 2021). The numbers indicate SEs participating in the study. Dots indicate other organizations (‘nodes’) that were not part of the study (Every node represents a different organization, yet not all the names of organizations were identified due to limited data or confidentiality issues. The nodes may be thus more interconnected), and which are associated with ego-networks of SEs under study—illustrated as lines (‘ties’) (See Legend for guide to the types of organisations and the type of secondary resource or knowledge in the CE being circulated). The map is not representative of the entire social-circular enterprise ecosystem in Hull. Instead, it provides a snapshot in a given spatial–temporal context. Since SNA is data-intensive, there is a lack of data over a specific period of time. Thus, the generated map of ties does not reveal how size and shape of inherently dynamic networks have been evolving over time

An Overview of Key SE Network Characteristics in Hull

Figure 1 illustrates a total of 932 ties of SEs to social, private and public sector organizations (see Legend), some of which span the city’s jurisdictional boundaries. Many of the SEs that emerged during the mapping (n = 130) concern (1) charities with a trading arm and social and/or environmental mission (‘SE/charity’ sub-category in Legend), and (2) charities without any trading arm. Entities under the ‘Solo-entrepreneur/sole trader’ category are likewise referred to as SEs due to their social and/or environmental mission (e.g., SE16 uses fabric scraps to make bags). Some of the identified SEs also provide support infrastructure to other SEs alongside their mission to generate social and environmental benefits (fourth category in Legend) Footnote 2. Figure 1 additionally highlights some of the cross-sectoral flows of secondary material resources (e.g., surplus wood/food/space) and knowledge associated with CE practices that may involve the use of secondary materials (e.g., planters made from reclaimed wood for composting workshops) (see Legend). Non-highlighted flows of other resources that indirectly stimulate resource recirculation concern financial flows (many of which underpin material flows), referrals and reputation, or knowledge, which is vital to the functioning of a given SE. The summary of all these flows of tangible and intangible resources, which influence to varying degrees network structure, and hence opportunities for scaling of the CE across the city, is outlined in Table 2 below.

Apart from the cross-sectoral interlinkages indicated in Table 2, there is also a number of sub-sectoral classifications (i.e., food; clothing and other textiles; furniture; arts and crafts; hygiene; electronics; construction/housing; women; disabled; elderly; ethnic minorities; homeless; prisoners and ex-offenders; vulnerable youth; refugees and asylum seekers; unemployed; alcohol addicts; mentally struggling; and mixed/other), which are likewise interlinked and therefore impact the development of a socially integrative CE in the city. As indicated in Table 1, some of such cross-sectoral interlinkages concern SEs’ ties to children’s education sector, mental health sector and prison. For example, a charity providing support for disabled children welcomes workshops from SEs using second-hand materials. KIDS also hosts workshops run by the charity for autistic people (SE30). Whilst workshops run by SE30 do not necessarily involve circular practices such as upcycling, its CEO expressed interest in employing CE practices as part of its workshops across the city. In addition, some SEs engaged in wood upcycling (e.g., SE7 and SE8) provide mental health support through their inclusive projects (i.e., by engaging vulnerable people in their activities) and benefit from referrals of vulnerable individuals from mental health charities such as MIND (and vice versa). Despite the relative lack of interest among doctors to prescribe activities such as community woodworking as part of the (green) social prescribing schemes [57], such SEs struggle to cope with the rising demand for the mental health services. This potentially opens up a window of opportunity to capitalize on existing community assets in order to run more of such ‘healing’ circular initiatives that could be organized in collaboration with local artists and nonconventional entrepreneurs that are not so oversubscribed (see extra bold ties in Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the viability of such initiatives is contingent on financial support from external institutions due to staff shortages and limited financial capacity of SEs. Another emerging theme concerns collaboration with the prison service. For example, SE15 runs furniture upcycling activities in a local prison together with SE8 (those two entities form a merger). Any profits from sales in shops run by SE15 can be reinvested into SE15’s and SE8’s missions (i.e., running a local hospice and providing mental health support to vulnerable individuals). From a network dynamic perspective, the frequency of the content being transferred and/or exchanged is organization-specific and depends on organizational mission and managerial and operational capacity (e.g., SEs addressing food aid to those in need are going to have frequent interactions with food retailers). Crucially, the high volume of surplus or second-hand materials from private companies (e.g., textiles, wood/pellets, food) surpasses the capacity of SEs to reprocess it, thus highlighting the scale of the waste problem in the economic system and limited capacity of SEs to expand operations in order to reutilize resources more efficiently.

Social Positioning and Organizational Attributes of Ties vs. Local CE Development

In this section we argue that social positioning, understood as occupying an advantageous/disadvantageous position in a given network, is linked to, and influenced by, organizational attributes such as organizational mission and size, organizational and entrepreneurs’ age, organizational antecedents and (relational) capabilities, all of which may, in turn, impact the local adoption and diffusion of (socially inclusive) CE thinking and practice.

Consistent with Lin [58], social positioning is often contingent upon SEs’ relational capabilities coupled with financial resources to form and maintain weak/strong (trust-based) ties with reputable and/or large organizations in higher positions (including well-known big brands) because such ties may increase their competitive advantage and financial autonomy. For example, connections to private companies can result in transfers of secondary materials (e.g., food, wood or textile surplus) to SEs [10]. In this way, whilst private companies can lower their waste management fees and enhance their corporate image, SEs can receive saleable secondary materials/production inputs free of charge. Most of such interactions are underpinned by informal agreements, which may be facilitated by strong ties that potentially impact upon the quality of procured resources and, consistent with Hoang and Antoncic (2003) [28], exemplify how social capital may act as a governance mechanism that creates cost advantage. For example, a manager of a SE upcycling wooden pallets (SE7) noted that ‘one of our volunteers is a director at a company that gives us pellets so they are quite useful. We sometimes get end of product stuff and things that we can sell’ (Interview, July 2020). The formation of quasi-mergers (joint ventures) between a less established SEs and a well-established SE is another way of boosting the former’s social positioning, which impacts the way SEs realize their missions and promote circularity. In such a merger between a well-established charity in the city (SE15) and SE upcycling wooden pallets (SE8), the latter SE (SE8) has benefitted from improved reputation, marketing and financial sustainability. As the manager of SE15 noted: ‘it [SE 8] has got to be self-sustaining but they do benefit from our HR, our finance, our support services, our brand, and it has got its own brand which it trades under, but it is connected to us’ (Interview, July 2020). Crucially, improved financial conditions have led SE upcycling wooden pallets (SE8) to provide its volunteers/trainees with a training course that includes an environmental module. This is in contrast to another SE upcycling wood (SE7), which has limited relational capacity, experiences financial precariousness and, partially linked to this, does not strive to expose their circularity. As the manager of SE7 stated: ‘We don’t actively highlight environmental side. If it is noticed—fine. We are here to help people with mental health issues. I know we could do a lot, but we do struggle for time and volunteers to do, for example, marketing’ (Interview, July 2020). It can be, however, argued that another SE upcycling wooden pallets (SE8), to some extent, chose to trade its autonomy for improved financial sustainability. In any case, findings reveal that SEs’ motivations behind partnerships and associated resource flows are rarely purely environmentally driven and CE has not been, in fact, mentioned by any of the interviewees at all. This implies that CE in a deprived community context is not driven by CE per se but occurs largely accidentally when responding to socio-economic challenges.

Further referring to organizational reputation that impacts social positioning, such reputation can be shaped by organizational antecedents. For example, SEs that emerge from the ‘bottom-up’ and build trust with potential collaborators and the local community from the very beginning of their existence tend to induce more trust and desire to collaborate with in the local community than those that have ‘top-down’ origins (e.g., those funded by the public sector, which is often perceived as ‘incumbent’). As a manager of a community-oriented SE that received endowment from the HCC noted, local organizations and community groups in the area ‘felt as if we [that SE] were looking to swallow them up’ (Interview, September 2020). Compared to the perceived inflexibility of ‘top-down’ organizations, ‘bottom-up’ organizations have the advantage of being able to capitalize on local knowledge and to recognize the needs of local people, and hence to come up with better solutions to local challenges [59].

The research findings reveal variegated power dynamics among, and hence social positioning of, respective SEs, associated with competition for funding in a deprived city where many SEs are resource constrained, and thus grant dependent. Such competition for funds is one of the key reasons behind lower trust and reluctance among SEs to collaborate with one another. For example, the CEO of a SE working with crafts (SE18) noted that: ‘Locally, the infrastructure is very disjointed, and I think they [funders] would rather have us competing for funding with each other than bringing us together to work together’ (Interview, September 2020). Once again, some of the more established SEs/charities tend to be better in writing winning bids, thus contributing to power asymmetries within the network whereby smaller SEs facing liability of newness and smallness are placed at a disadvantage unless they receive support. Such circumstances are additionally exacerbated by the fact that, despite the diversity of funders at the national level, SEs that rely on grants tend to apply for the same pots of money, and often through SIOs at the local level. A local councillor from the HCC additionally noted that there is a need to distribute money from central organizations/funders more equitably between SEs across the city (Interview, June 2020). Linked to this, a manager of one SIO noted that there may be an opportunity to ensure that those more established and successful charities, which usually win funding, can put in a bid to a national grant fund as part of their bulk contribution in support of charities less capable of bidding, i.e., those facing liability of newness and smallness. He further noted that there are, in fact, grant makers who would like to support all charities, regardless of size or capacity, yet they do not have enough resources to achieve that. There are, however, several occasions whereby SEs join forces to co-write bids for, or propose, specific joint projects. In the literature, this is referred to as a ‘choice homophily’ whereby SEs, which are usually homophilous (i.e., similar) by organizational age and mission/aspirations, choose to work with one another, and in so doing they develop strong relationships underpinned by trust [60]. Under such circumstances some less experienced SEs may join more established ones. In addition to exchanging knowledge and skills, such partnerships may also potentially help to win higher bids, and hence result in better outcomes for the population SEs are trying to support. This is because ‘[f]unders, particularly the [UK] Lottery, are now encouraging applications to come forward and say, ‘you can apply for more if there is a partnership structure in place’ (Manager of one SIO, Interview, April 2021). Whilst many SEs used to be subject to ‘survive or flight sort of environment’ (Manager of one SIO, Interview, April 2021), such new funding requirements coupled with declining funds from the government have only further propelled SEs to build more on their strengths and work in partnerships—two aspects that ultimately improve their social positioning.

Age of a given organization is another organizational attribute that may impact local adoption/diffusion of CE thinking and practice as it is associated with network diversity innovative capacity. Consistent with studies demonstrating that network diversity is shown to be negatively correlated with ventures under 3 years old as it takes a lot of time and energy to forge new links [25], many of the SEs under study that are less than 3 years old have less heterogeneous ties (e.g., SE14 using fabric scraps to make textile items and SE16, which is a charity shop primarily selling second-hand clothes and furniture) and can be hence associated with lower innovative capacity. Moreover, young charity shops, for example SE16, which belong to a larger national chain and is hence subordinated to higher management structures, display lower degrees of flexibility when it comes to decision making at the local level and, linked to this, rarely collaborate with other SEs in the city. Other SEs also simply do not have an interest in forging new collaborations out of personal reasons. Some representatives of SEs also complained about the lack of collaborative spirit in the city, which may be amplified in particular spatial locations.

Spatial Positioning vs. Circular Ties

This section examines the spatial dimension and contingencies of SE networks, including the neighbourhood and citywide contexts in which SEs are embedded, thus reinforcing the idea that networks are socio-spatial [61]. Crucially, yet in the light of research findings, although the influence of geographic location and geometric distances are a highly relevant and important consideration, this is not to underestimate the influence of other types of (dis)proximity (e.g., relational/social proximity stemming from trust-based relations that develop over time in particular places) in the forming of circular ties. Map 2 below indicates geographical positioning and spatial dispersion at the city-scale of respective SEs (including SIOs) that participated in the study. However, given that some of the organizations have their premises based in one location, yet they deliver their goods/services to different parts of the city, the map does not fully showcase how (potential and existing) CE benefits are spatially distributed across the city Footnote 3. Numbers of SEs that deliver services and/or products throughout the city are shown in red.

Social enterprises and support infrastructure organizations versus levels of deprivation according to The Index of Multiple Deprivation (2019) [see Map 1] in Hull. Graph made in: ArcGIS

McPherson et al. (2001) recognized that geographic proximity creates contexts for the development of homophilous relations whereby collaborating actors are broadly similar to one another (e.g., when it comes to representing similar sectors or running similar activities) [62]. Nonetheless, interviewees conducted for this research clearly indicated that many SEs are less willing to collaborate with those SEs representing the same sector and mission (e.g., delivering educational workshops on food growing—SE6) that are located in a close geographical proximity due to competitive pressures and the risk of inadvertent knowledge spillovers. Such negative externalities occur regardless of SEs’ social positioning/development stage. Younger SEs facing liability of newness and smallness are, however, even more likely to experience such negative externalities as they try to establish themselves in the market. Many SEs are hence required to find strategic ways to act as satellites across the city, outside their catchment area Footnote 4. Crucially, the location of such ‘satellites’ is contingent upon the broader characteristics of particular neighbourhoods where prospective customers/beneficiaries reside. For instance, food aid charities tend to offer food aid (including food fridges hosted in community centres) throughout the city, especially in neighbourhoods where the most deprived residents cannot afford public transport to food banks (see green icons associated with SE1 and SE3 on Map 2). Since such high levels of deprivation usually go hand-in-hand with high levels of crime, SEs (and their services) promoting resource sharing/renting in such highly deprived neighbourhoods tend to avoid operating in such areas. For example, the CEO of SE11 located in a crime-filled neighbourhood in West Hull rejected the idea of running a rental service due to experiencing break-ins.

Charity shops are often located in close proximity, yet they do not tend to compete with one another over customers. As the manager of a large local charity retail (SE15) noted, customers, in fact, often ‘do charity shop rounds (…) so some of our more successful shops are actually in a parade of shops where there are three different charity shops because generally shoppers are not shopping to support the hospice, they are shopping because there is a t-shirt that they like’ (Interview, July 2020). Findings reveal that the failure/closure of charity shops is, instead, largely attributed to their internal organization’s difficulties exacerbated by external factors, for instance pandemics. Such difficulties usually concern financial issues, for example, when managing volunteers who then wish to be remunerated. There are also some spatially contingent power imbalances whereby well-established and larger SEs tend to dominate in particular locations. For example, the manager of a large local charity retail stated that: ‘We can’t keep opening shops anymore because we are running out of spaces where they are busy enough to have shops. We can’t step outside of Hull and East Riding catchment area because there are other hospices and so you can only have kind of like one charity shop in that village or on that high street’ (Interview, July 2020). Nonetheless, the same retail charity SE managed to form a merger with a SE upcycling wood (with which it shares revenues) and set up a lottery to source more financial capital from outside its catchment area. Inability to find geographically attractive spaces for expansion thus does not necessarily imply diminished SE performance.

SEs are more likely going to form homophilic ties (i.e., collaborate with SEs that are more similar to themselves), including those in close proximity, in case they complement each other’s activities. For instance, findings reveal that one SE capturing food surplus from supermarkets to transform it into meals for impoverished communities (SE1) works closely with a neighbouring SE that likewise provides food to a local community, yet offers the former SE (SE1) free space for cooking and food storage. Whilst studies reveal that geographical proximity alongside relationship longevity in place can positively impact the quality of relationships due to the time required to foster trust [63], in this case such close geographical proximity coupled with frequent interactions does not indicate that there are high levels of trust and reciprocity between two organizations. For example, efforts of SE1 to transform vacant urban land owned by the neighbouring SE ended up in failure after the latter SE decided to hand the land over to private companies for transformation into social housing infrastructure. This showcases the complexity of power relations underlying many network ties.

SEs may also complement each other’s activities whilst being co-located within the same premises so that their overhead costs are reduced. Moreover, the manager of one SIO noted that there is a potential to utilize the so-called ‘meanwhile spaces’, i.e., empty office spaces/units/segments, which could be, at least partially, donated to charities for shared use at low rates. The outbreak of COVID especially prompted many people to work from home and ultimately left many businesses paying business rates for underutilized spaces. Under such circumstances finding asset-specific synergies between two SEs is of key importance to ensure that they have some elements in common notwithstanding geographic location.

In the local food sector in Hull, there are also three SEs acting as ‘food hubs’, which form homophilic ties by mission attribute and coordinate efforts to provide food aid across the city. Facilitated by a SE, which redistributes food surplus from large retailers to social and public sector organizations across the city (SE2), strategic spatial positioning of these food hubs (i.e., in the northern, central and eastern parts of the city) (see SE25, SE26 and SE1 [cf.64], in green circles on Map 2) helps them to effectively realize their shared mission through coopetition. An alternative to such food aid initiatives constitute SEs such as SE4—an urban agriculture project in central Hull near the city centre. SE4 is co-located with a private company after the SE became the tenant of the company’s vacant land. Such geographical proximity fostered relations of trust and reciprocity between the two partners. For example, in return for free rent, the SE not only enhances the private company’s corporate image, but also offers an attractive outdoor space for corporate (socially distanced) events. Such collaboration is in line with Witt (2004) who noted that ties based on contributions perceived to be equivalent are more successful than those that are unequal and opportunistic [25]. SE4 also hosts a variety of social events, welcomes volunteers from the adjacent prison and provides a marketspace space for local artists and food growers. Despite having strong ties to several organizations, the temporal nature of the tenancy agreement suggests, on the one hand, that the longevity of this mini-SE-ecosystem is contingent upon the private company’s future growth strategies. On the other hand, other food hubs such as SE25 and SE26 are autonomous and perhaps more resilient in that they own their properties. Whilst those hubs tend to be more interested in providing symptomatic food aid, they have the potential to disseminate CE thinking and practice in their neighbourhoods. For example, food hub—SE25—is in the process of developing a community hub, which will host an array of inclusive training schemes, and which is surrounded by entrepreneurs, some of whom could contribute to the CE in the city. By forging more links with community-based organizations and SEs that are, for example, engaged in activities such as tailoring (SE13 and SE14), it would be possible to expand the circular curriculum of such ‘hubs’. In addition, agglomeration or clustering of diverse SEs in one place can generate a range of untraded interdependencies, i.e. intangible benefits that cannot be costed [65]. These may include enhanced community spirit and networking that may result in mutually beneficial work partnerships. Overall, whilst co-location may enable information and knowledge spillovers [39], gains from co-location may also come with costs [66]. For example, entrepreneurs clustered around such hubs may need to travel across the city to reach their workplace. One could, however, argue that such costs may be offset by environmentally friendly activities within such hubs.

Core vs. Periphery: Network Structure vs. Geographic Location

Occupying a core position within a network (Fig. 1) does not necessarily equate to being centrally located within the city (Map 2). Whilst findings suggest that there is a high network density, i.e., high concentration of actors, including large SEs, in the central part of Hull, these actors are not necessarily more connected to other entities within the network than, say, SEs located in western, northern or eastern parts of the city. For example, SE1 located in East Hull has a large, well-established network with the highest degree centrality (n = 96Footnote 5) and centrality closeness in the whole network (n = 0.48Footnote 6). Nonetheless, some circular SEs located on the periphery of the city appear to be negatively affected by their geographic location. An example concerns SE7 located on the Western margins of the city. It does, however, struggle with the low number of volunteers, which affects upscaling of SE’s activities and could be attributed to the lack of easy access by public transport.

Irrespective of geographic positioning, SEs located in the ‘periphery’ of the structural network map (Fig. 1) concern ‘solo-traders and small entrepreneurs’ many of whom tend to work only on a part-time basis and/or treat their activities as hobby. They rarely consider upscaling their circular activities. Many of these organizations are rather new to the broader SE ecosystem and differ from SEs commonly known as charities in that they are not necessarily embedded in, or serving, local communities and vulnerable social groups (e.g., mentally disabled), but they instead usually target customers with high purchasing power. It can be argued that such peripheral SEs offer new, innovative ideas and information, which could be exchanged with SEs that occupy the ‘core’, i.e., a more central position in the network, and tend to be more established [67]. Forging such links does, however, require a certain degree of trust, especially considering that some less established SEs in the network periphery may be less willing to interact with more established SEs for fear of competition.

Circular Brokerage

There is potential to foster more collaboration within and across sectors, and across geographic scales, through brokers—important bridges that help to weave networks, especially those that embody circular practices. Whilst the highest betweenness centrality in the generated network (Fig. 1) is represented by SE1 (capturing food surplus from supermarkets to transform it into meals for impoverished communities) (n = 0.194), SE18 (working with crafts and artists) (n = 0.201)Footnote 7 or HCC (0.136), interviews with SE1 and SE18 revealed that these SEs do not have enough capacity to proactively foster new linkages/broker for the purpose of promoting circularity within a given urban setting due to issues such as low financial capital and time constraints. Besides, whilst some SEs such as SE5 (collecting food surplus and organizing food growing activities in local communities) or SE31 (offering support to elderly people) expressed interest in raising environmental awareness, their ties are less extensive than those of SEs indicated above and SIOs. SIOs and non-profit initiatives could jointly facilitate CE-related flows of knowledge and information across the network due to their ‘gatekeeping’ behaviour, expansive contacts (including to regional or national authorities granting funding) and reported interest in promoting CE. The local university could also act as an important boundary-spanner and knowledge/circular spreaders/irrigators that has the potential to incentivize and mediate interactions between relevant stakeholders (especially those on the social and spatial periphery) by irrigating the broader social circular enterprise ecosystem with valuable knowledge (e.g., by offering training and consultancy). A broker may also act as a coordinator in that a given organization belongs to the same group/cluster and act as a broker within that group/cluster. For example, by providing a market space for other entrepreneurs, SE making crafts and offering upcycled crafts from other entrepreneurs (SE9) connects SEs representing the same ‘cluster’ (e.g., textiles). Although those entrepreneurs do not seem to proactively collaborate, such brokering SEs could foster knowledge sharing/exchange and joint projects.

One of the propositions of this research is that some members of an emerging CE network (e.g., local community SEs) could strive to appoint an internal/external ‘representative’ and visionary broker with leadership skills for each member ‘cluster’/sub-classification. For example, a SIO engaged in the food sector—Hull Food Partnership—already acts as a ‘representative broker’ of the food sector by forging strategic partnerships and communicating information to relevant actors. Crucially, such brokers could bridge different clusters and collaboratively govern CE networks in a systematic and systemic manner. This is even more important given that different organizational forms and attributes, including variegated management structures, are likely to be reflected in different networking logics, which would require a more ‘unified’ approach to CE networking across sectors. Such roles would, however, require financial support and hence recognition of CE among potential funding bodies.

Following Ciulli et al.’s (2019) concept of ‘circularity holes’ [68], it can be noted that SEs, such as those generating income by running second-hand shops, act as liaison brokers [69] who indirectly connect donors of certain products (e.g., large retailers donating unsold clothes) with receivers/customers. In a similar fashion, brokering digital platforms, such as SE23 fostering reuse by linking individuals to charities or OLIO mobile app, connecting donors of ‘food waste’ with receivers. The latter case suggests that brokers should be sensitive to the broader contexts and protect the reputation of economic actors, such as large corporations that seek to donate large amounts of waste/surplus materials to SEs (e.g., food ‘surplus’). In any case, as CE practices are increasingly being digitally enabled [70], it can be also expected that such digital technologies and social media will play an important role in fortifying circular SE ecosystem regardless social or geographic positioning of brokers.

A more detailed discussion of circular brokerage in the context of Hull is examined in Pusz [71].

The Role of Network Collaborative Ties in Local CE Development: Towards a Heuristic Framework

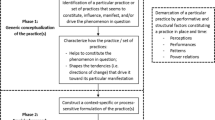

Drawing upon the research findings, Fig. 2 below represents an overview of a broad array of cause-effect relationships between interdependent variables that underpin SEs’ performance and innovative capacity to foster development of integrative CE. It shows that the development of integrative CE can occur provided that SEs working with/for disadvantaged people already engage in or are willing to engage in circularity, and/or any ties (potentially) forged between SEs and other organizations help to boost/employ circularity and/or add a social element to existing circular activities. Respective variables (or causal mechanisms/contingencies) influence (either alone or altogether with other variables), and are influenced by (to varying extents), the broader institutional context/structural factors, including regulatory environments, in which they are embedded (although the latter are not examined in this paper due to limited space), as well as the overall network structure.

In line with the social capital theory, findings reveal that organizational performance, or productive benefits, are greatly determined by, or enmeshed within, an organization’s external networks, aka corporate social capital [72]. Consistent with Lee et al. [73], those external networks/entities interact with, and are influenced by, organizational attributes that encompass internal organizational capabilities and networks (among other variables such as availability of time and money to co-create new projects with other SEs). Inter-organizational collaboration is also influenced/shaped by mutually affecting aspects such as social and spatial positioning, which also impact and are impacted by particular organizational attributes. Crucially, spatial positioning may impact, and be impacted by, the SEs’ social positioning. Inter-organizational linkages may result in increased network heterogeneity (i.e., diversity of functions and utility of nodes, including diverse knowledge), which, according to some fields of study (e.g., industrial symbiosis and industrial ecology), can lead to better results in resource management [74]. Linked to this, network heterogeneity and associated resiliency to external shocks can arguably result in more circularity, yet provided that relevant actors have relevant capabilities to capitalize on those functions, i.e., financial resources and existing knowledge and skills (including relevant organizational management skills) that are necessary for the development of CE practices, especially those which conjoin social and environmental missions. This is where SIOs may help by acting as brokers between disconnected organizations and offering business support.

Concerning the content of network ties, the ability of a given resource flowing through such ties to fulfil customers’ or community needs (and usually upon being reprocessed at the SE level) in practice impacts the performance of a procuring organization and has implications for the survival and growth/development of a given SE, and ultimately for local CE development. Crucially, respective variables are underpinned by power relations that should be accounted for when investigating the broader socio-spatial dynamics that are shaped by economic logics for exchange and interaction, and which impact the formation of collaborative CE relationships. It is also important to recognize any potential external shocks (e.g., pandemics) that can cause significant socio-economic disruptions, which can significantly impact formation of collaborative inter-organizational ties, and ultimately the upscaling of CE thinking and practice from the very local to the regional, national and international scales.

Conclusions

In investigating the role of networks in stimulating the local development of a socially and environmentally integrative CE in a particular locale (in this case, the City of Hull in the UK), this article makes a novel contribution to existing research on the CE, network theory and (social) entrepreneurship. It examined the under-investigated socio-spatial-relational aspects of the CE such as (supra- and infra-)local networking for entrepreneurship and community development at the local level, along with an analysis of the power relations underlying (collaborative) generation of distributional socio-environmental benefits associated with CE practices in a given territory. Doing so, it found that mission-driven social enterprises (SEs) tend to engage in localized short-loop activities at the neighbourhood and city scales (e.g., reuse, upcycling, refurbishing or repair), which are often overlooked by mainstream CE policies and require change in consumer behaviour (rather than, for example, investment in new waste separation technology). Those CE activities are vital for the local development of the CE into a more socio-environmentally integrated set of localized social structures and relations. By way of conclusion, we highlight five findings, which revolve around the proposed heuristic framework (Fig. 2) illustrating how interlinkages between respective aspects may impact SEs’ performance outcomes and ultimately the local development of an integrative CE. We also identify some areas for further research.

First, we contend that mapping and knowing SE networks, including their socio-spatial structural characteristics and key actors, are vital for knowing how to design strategies aimed at improving connectivity between respective organizations for local CE development. System-wide adoption and diffusion of CE practices will not, in fact, take place unless place-based cross-sectoral collaborations enabling social actors (in this case, SEs) to ‘plumb’/’fortify’ the ecosystem are forged. Crucially, whilst the generated SE ecosystem map only provides a snapshot of the broader social (circular) enterprise ecosystem in Hull in a given temporal context, some of the key network patterns that underlie formation of collaborative ties for the CE could be discerned. Linked to this, we argue that integrating considerations of SEs’ organizational attributes (e.g., relational capabilities, reputation, age, organizational antecedents and management structures), as well as investigating motivations behind partnerships and their social and spatial positioning, which, in turn, impact the content of SEs’ ties and network heterogeneity, offers new insights into the underlying imbalances (such as those liked to competition over funds) and associated variegated levels of trust within the social circular enterprise ecosystem. All these aspects need to be scrutinized due to their impact on SEs’ performance outcomes and, ultimately, on the development of a socially and environmentally integrative CE in particular urban settings, such as the structurally disadvantaged city examined here.

Second, and in relation to the above-mentioned SEs’ organizational attributes such as trust and reputation, whilst SEs in relatively socially disadvantaged cities like Hull are generally familiar with one another (and engage in many (in)formal and cross-sectoral collaborative ties), many potential collaborative relations are impeded due to competition-driven low trust and potential reputational risks between interacting organizations. Collaborative relations may be also obstructed by limited resources such as time and skills that are necessary to form new relations. As Sennett (2012) noted, effective collaboration is a craft that requires skills enabling to foster mutual understanding [75]. Moreover, employment of CE practices will not increase attractiveness of the overall ecosystem to external and internal stakeholders unless relevant institutional support is in place (locally).

Third, diffusion of CE thinking and practice may be facilitated through relevant circular brokers and spreaders who deserve more recognition in sustainability transitions towards the CE, especially with regard to governance at the city or regional scales [76,77,78]. Such brokerage may be facilitated by digital technologies and social media platforms that improve reachability and will continue to play an important role in assisting SEs and their networks in networking, transacting, maintaining and reconfiguring connections whilst enabling and accelerating diffusion of CE thinking and practice across diverse (urban) spaces within a given locale or place. This can ultimately fortify social and system integration and build the basis of a circular SE ecosystem regardless of the social or physical geographic positioning of brokers. A more detailed discussion of circular brokerage in the context of Hull is examined in Pusz [71].

Fourth, we propose the need to develop the chain of loosely interconnected entrepreneurial hubs (aka mini-ecosystems) that emerge in different parts of a city, yet around well-established SEs that often offer support to a diverse array of social entrepreneurs, including those engaged in the CE and struggling to increase financial autonomy. Understood as ‘inter-connected collections of actors, institutions, social structures, and cultural values’ (p.1252) [79], such entrepreneurial ecosystems could be infused with more circular practices, ultimately helping to regenerate areas of economic stagnation with a corresponding lack of supporting social capital whilst strengthening communities and neighbourhoods across the city. It is also important to support SEs in acting as satellites across the city in order to facilitate recirculation of material and knowledge resources within the city boundaries. Besides, given that SNA can help to discover collaborative common ground and connectivity within the broader complex ecosystem, the results are expected to encourage decision-makers to invest in social infrastructure in such a fashion that it is possible to unlock the potential for more local and community-driven circularity in the city.

Finally, SEs, many of which run circular activities, are likely to experience significant development over the next years due to widening socio-economic inequalities, growing environmental crisis and new opportunities created by the development of CE practices. And yet, this research revealed that SE-led CE practices have evolved in the local context primarily by drawing upon, rather than ameliorating, socio-spatial inequalities in a structurally disadvantaged city. Whilst this may be true in other places and localities (be those deprived, middle-class or wealthy), it is important to go beyond identifying stakeholders and relationships when exploring the potential to scale up for the local development of the CE (e.g., by taking into account spatial proximity or organizational characteristics). Whilst this article investigated network patterns and organizational characteristics of SEs in the context of a structurally disadvantaged city wherein many SEs intend to offer cut-price circular products and services for the socially excluded and/or financially struggling individuals (ironically implying that deprivation, to some extent, creates a market for the CE), future research could interrogate network development for the CE in more socially and economically prosperous cities where an integrative CE might be used as a tool to empower disabled/mentally struggling individuals engaged in CE practices more than those who find themselves in a financially precarious situation. Such research would ideally call for more regional and/or national collaboration between less and more developed cities around the world to better simulate CE development, thereby promoting socio-systemic integration of the CE at progressively larger geographical scales. Further research could explore in more depth organizational and network variables in other locales that may likewise impact the formation of circular ties and, ultimately, the trans-local development of the CE.

Data Availability

Anonymised metadata (summary data) upon which this paper is based are available on request from the corresponding author.

Notes

LSOAs have an average population of 1500 people or 650 households.

Ego-networks of some of such SEs were not mapped due to lack of data.

SE23 is an online platform connecting charities and individuals hence is not depicted in Map 2; its staff works remotely but their registered address is in Hull.

This goes beyond the prevailing perception of the existence of an East-West socio-cultural divide in the city.

These values are only provisory as the data for each SE vary depending on the amount of information shared with the researcher. SE1 (EMS Ltd.) being a Cresting.

As above.

These numbers are not highly representative as it is very likely that other more established SEs have many more connections and high betweenness centrality.

References

Hobson K (2016) Closing the loop or squaring the circle? Locating generative spaces for the circular economy. Progr Human Geo 40(1):88–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514566342

Murray A, Skene K, Haynes K (2017) The circular economy: an interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J Bus Eth 140(3):369–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2693-2

Ranta V, Aarikka-Stenroos L, Ritala P, Mäkinen SJ (2018) Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: a cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour Conserv Recycl 135:70–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.08.017

Schulz C, Hjaltadottir RE, Hild P (2019) Practising circles: studying institutional change and circular economy practices. J Clean Prod 237:117749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117749

Geissdoerfer M, Savaget P, Bocken NM, Hultink EJ (2017) The circular economy—a new sustainability paradigm? J Cleaner Prod 143(1):757–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048

Longhurst N, Avelino F, Wittmayer J, Weaver P, Dumitru A, Hielscher S, Cipolla C, Afonso R, Kunze I, Elle M (2016) Experimenting with alternative economies: four emergent counter-narratives of urban economic development. Curr Opin in Env Sust 22:69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2017.04.006

Daniele D, Johnson T, Zandonai F (2009) Networks as support structures for social enterprises. In: Noya A (ed) The changing boundaries of social enterprises. OECD Publishing, Paris

Giddens A (1984) The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Polity Press, Cambridge

Kim D, Lim U (2017) Social enterprise as a catalyst for sustainable local and regional development. Sustainability 9(8):1427. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081427

Lekan M, Jonas AEG, Deutz P (2021) Circularity as alterity? Untangling circuits of value in the social enterprise-led local development of the circular economy. Ec Geog 87(3):257–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1931109

Aminoff A, Valkokari K, Kettunen O (2016) Mapping multidimensional value(s) for co-creation networks in a circular economy. In: Afsarmanesh H, Camarinha-Matos L, Lucas Soares A (eds) Collaboration in a hyperconnected world PRO-VE 2016 IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology, vol 480. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45390-3_54

Domenech T, Bleischwitz R, Doranova A, Panayotopoulos D, Roman L (2019) Mapping industrial symbiosis development in Europe_typologies of networks, characteristics, performance and contribution to the circular economy. Resour Conserv Recycl 141:76–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.09.016

Walker AM, Vermeulen WJV, Simboli A, Raggi A (2021) Sustainability assessment in circular inter-firm networks: an integrated framework of industrial ecology and circular supply chain management approaches. J Cleaner Prod 286:125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125457

Deutz P (2014) A class-based analysis of sustainable development: developing a radical perspective on environmental justice. Sust Dev 22(4):243–252. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1528

Hubmann G (2022) The socio-spatial effects of Circular Urban Systems. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 1078:012010. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/1078/1/012010

Wasserman S, Faust K (1994) Social network analysis: methods and applications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Baker W (2014) Making pipes, using pipes: how tie initiation, reciprocity, positive emotions, and reputation create new organizational social capital. In: Brass GL, Mehra A, Halgin DS, Borgatti SP (eds) Contemporary perspectives on organizational social networks. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingey, pp 57–71

Bolton M, Kingston J, Ludlow J (2007) The Venturesome model: reflecting on our approach and learning 2001–6. Charities Aid Foundation, London

Bourdin S, Galliano D, Gonçalves A (2022) Circularities in territories: opportunities & challenges. Eur Planning Stud 30(7):1183–1191

Tapia C, Bianchi M, Pallaske G, Bassi AM (2021) Towards a territorial definition of a circular economy: exploring the role of territorial factors in closed-loop systems. Eur Planning Stud 29(8):1438–1457. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1867511

Taddeo R (2022) Bringing the local back in The role of territories in the “biological” transition process toward circular economy: a perspective of analysis. Front Sustain 3:967938. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2022.967938

Delgadillo E, Reyes T, Baumgartner RJ (2021) Towards territorial product-service systems: a framework linking resources, networks and value creation. Sust Prod Cons 28:1297–1313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.08.003

Brudel J, Preisendorfer P (1998) Network support and the success of newly founded businesses. Small Bus Econ 10(3):213–225

Hervieux C, Turcotte MFB (2010) Social entrepreneurs’ actions in networks. In: Fayolle A, Matlay H (eds) Handbook of research on social entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, Cheltenham, p 182

Witt P (2004) Entrepreneurs’ networks and the success of start-ups. Entrepren Region Dev 16(5):391–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/0898562042000188423