Abstract

This paper estimates the long-run impact of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP in South Africa and whether it changed after the 2008 global financial crisis. The paper further determines whether certain channels amplified or dampened the transmission of exchange rate deprecation to GDP after the crisis. The long-run relationship estimated using fully modified ordinary least squares, dynamic ordinary least squares, and ordinary least squares indicates a one percent exchange rate depreciation raises GDP by less than 1.4 percent. Evidence from the model with the interactive global financial crisis dummy and exchange rate shows that the impact of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP was diminished after the crisis. The counterfactual analysis reveals that the exchange rate volatility, foreign demand, investment, imported intermediate inputs, consumption, consumer price level, and export volume channels dampened the stimulative effects of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP post-2008. This evidence indicates a disconnect between the exchange rate depreciation and the GDP relationship. This implies that policymakers cannot rely on the exchange rate depreciation as a potent macroeconomic stabilization policy tool and may not achieve the National Development Plan growth objective via an export-led growth strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The exchange rate is one of the key macroeconomic policy tools that can significantly affect a country’s external competitiveness and economic growth through the aggregate demand and aggregate supply channels. From the aggregate demand channel, the exchange rate changes affect the export competitiveness and in turn output growth. Whereas, from the supply side, the exchange rate changes affect the cost of imports of consumption, intermediate, and capital goods, which will impact the cost of production and investment decisions. The producers will pass the changes in the cost of production to consumers and this change in prices will have a ripple effect on the overall economy—i.e., the price levels and output. The relationship between the exchange rate and GDP growth is among the highly debated macroeconomic stabilization policies in the literature and remains the central economic goal in the macroeconomic policy agenda across the globe (Iqbal et al 2022a, b; Easterly and Levine 1997; Fischer 1992; Knight et al. 1993; Most and De Berg 1996). Depending on the relative strength of the impact on the aggregate demand and supply channel, empirical literature provides for the possibilities of expansionary or contractionary or neutral net effects of the exchange rate on real output growth.

Dornbusch (1988) postulates that the real exchange rate devaluation would have expansionary effects by raising the value of tradable goods. The expansionary effects happen when the depreciation of the domestic currency makes exports internationally more competitive, thereby raising aggregate demand (Iqbal et al. 2022a, b; Bahmani-Oskooee et al. 2017a, b, c; Dornbusch et al. 1976). However, the empirical evidence often presents mixed results of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP growth. In the elasticities approach, the exchange rate devaluation will improve the trade balance if the Marshall Lerner condition is satisfied—i.e., the sum of the export elasticity and import elasticity is greater than one. From the absorption approach, the exchange rate devaluation will have a positive effect on output through its expenditure-switching and expenditure-reducing effects. In the Keynesian approach, the exchange rate devaluation enhances the international competitiveness of domestic industries, and this leads to a switch of spending from foreign goods to domestic goods, which increases domestic output. In this case, the demand side effects of the exchange rate devaluation are stronger than its effects on the supply side.

There are ongoing debates in the literature which remain inconclusive regarding whether the exchange rate depreciation can be viewed as a shock absorber or a source of macroeconomic shocks and a channel that transmits and propagates financial shocks to the real economy. Consequently, this paper focuses on the latter aspects and examines the long-run impacts of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP in South Africa and how the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) impacted the long-run effects. In addition, we adopt and modify the Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) approach to perform a counterfactual analysis to determine the extent to which the effects of the exchange rate depreciation changed post-2008 by showing the role of different channels of transmission. The findings on the exchange rate depreciation effects on GDP post-2008 have serious implications for the expected role of exports-led growth, which is envisaged in the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 as a growth strategy in South Africa. The NDP envisages the exports-led strategy as essential in raising economic growth to 5 percent per annum and this has not happened post-2008 GFC.

This study is motivated by various recent economic developments. First, the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) business cycle dating indicates a prolonged downward phase of the business cycle which began in 2013 and has lasted more than 58 months and is the longest since 1945. As shown in Fig. 1, the nominal rand per US dollar (R/US) exchange rate depreciated over this period. This concurrence of the prolonged downward business cycle and the continuous exchange rate depreciation is indicative of the disconnect between the expected effects of the depreciation on economic growth, ceteris paribus. The conventional theory links improved competitiveness, which boosts exports while inducing a switch in demand from imported goods towards domestically produced goods.

Second, the South African nominal bilateral rand per US dollar exchange rate has depreciated for a prolonged period post-2008. The reference to the bilateral exchange rate follows indications in Boz et al (2020) that the US dollar remains a globally dominant invoicing currency despite the comparatively smaller role of the US in global trade. The exchange rate was R7.48/US$ at the end of 2009 and reached R14.44/US$ at the end of 2019. Exports and economic growth have remained weak as shown in Fig. 1. Real GDP growth averaged 1.73 percent from 2010Q1 to 2019Q4 compared to 4.08 percent from 2000Q1 to 2008Q4.

The third motivation is related to the objective of the NDP 2030 which envisages an investment-GDP ratio of 30 percent to boost economic and productivity growth. Raising the investment-GDP ratio also implies that import growth and the exchange rate dynamics will play a significant role in the evolution of GDP growth. It is, therefore, important to establish the channels through which the exchange rate depreciation shocks dominate GDP growth rate and the implications of these channels for the exchange rate policy. The exchange rate depreciation effects have very distinct implications for export-led and investment-led growth policies.

Fourth, the government’s economic policy has relied on the expansionary effects of the exchange rate depreciation as a potent macroeconomic stabilization policy tool. Hence, the findings in this paper will indicate if this has or has not materialized post-2008. South Africa achieved annual growth rates of more than 4 percent between 2003 and 2007 but the economy failed to return to these average growth rates after 2008.

The analytical focus on the post-2008 period is not driven by structural break tests but is due to the lagged effects of the GFC that led to the 2009 recession in South Africa. Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) suggest that there is no consensus about the dating of the GFC since the Lehman Brothers’ failure occurred several months after the speculative pressures surged in the US subprime market. In addition, the post-2008 global recession period encompasses the recession in South Africa, periods of economic instability, and heightened policy uncertainty, which include events of successive sovereign credit downgrades, monetary policy easing and tightening, and episodes of quantitative easing and tightening in advanced economies, as well as disruptions in trade and global value supply chains. A simultaneous occurrence of such events has never happened in the past, including after the adoption of the inflation-targeting framework in South Africa.

This paper does not examine the determinants of the exchange rate as in Chenet et al. (1997), Clarida et al. (1994), and Tian and Pentecost (2019). However, the focus is on the exchange rate depreciation effects on GDP as done in Semosa and Aphane (2017), Mujahid and Zeb (2014), Kalyoncu et al. (2008a; b), Lubis and Karim (2017), and Christopoulos (2004). The link between the real exchange rate changes and domestic production or economic growth has been investigated by Iqbal et al. (2022a, b), Bahmani-Oskooee (1998), Kamal (2015), Kalyoncu et al. (2008a; b), Bahmani-Oskooee and Mohammadian (2018), Upadhyaya and Upadhyay (1999), Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza (2006), Semosa and Aphane (2017), Sharaf and Shahen (2022, 2023), Nusair (2021), Bahmani‐Oskooee and Mohammadian (2017), Ndou et al (2017), Bahmani‐Oskooee and Arize (2020), An et al. (2014), Lubis and Karim (2017), Christopoulos (2004), and Habib et al. (2016).

The exchange rate depreciation effects on output have been examined using different econometric methodologies in different economies. Christopoulos (2004) used panel data unit root tests and panel cointegration tests including the Johansen maximum likelihood cointegration tests and Fully Modified OLS. Lubis and Karim (2017) applied the pooled ordinary least squares estimation approach on the founding member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Kamal (2015) estimated an error correction model for Bangladesh. Nusair (2021) studied selected Asian countries and utilized the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL). Studies that apply the NARDL include Bahmani-Oskooee and Mohammadian (2016) for Australia, Bahmani-Oskooee and Mohammadian (2017) for Japan, Bahmani-Oskooee and Mohammadian (2018) for Turkey, Bahmani-Oskooee and Arize (2020) for selected African countries, Nusair (2021) for a group of Asian countries, Sharaf and Shahen (2022, 2023) for Egypt. An et al. (2014) estimated the sign-restricted Vector Autoregression (VAR) model. Ndou et al. (2019) estimated VAR models to determine the short-run effects of the exchange rate depreciation in South Africa. Semosa and Aphane (2017) estimated a VECM and applied the Johansen cointegration approach in South Africa.

We estimate three models, (i) a parsimonious long-run linear regression model based on Christopoulos (2004), Kalyoncu et al (2008a, b), Mujahid and Zeb (2014), Lubis and Karim (2017), Kamal (2015), and Christopoulos (2004), (ii) a linear model which includes crisis dummy variable interacted with the exchange rate to determine the impact of the GFC on the exchange rate deprecation effects on GDP, and (iii) a counterfactual model to determine the important channels transmitting the deprecation effects to GDP post-2008. The parsimonious long-run relationship between the exchange rate and GDP examines the extent to which this model captures this relationship in South Africa. However, we differ from these authors’ specifications by including the interaction term between the exchange rate and the post-2008 GFC period in the model, to capture the impact of the crisis on the stimulatory effects of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP. The inclusion of the interaction term aims to determine whether the post-2008 GFC period impacted the relationship between the exchange rate depreciation and GDP in South Africa. Lastly, we estimate a counterfactual model to determine the important channels that transmit the exchange rate depreciation effects into GDP post-2008 GFC.

To the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of any studies that have used the interaction terms when determining the long-run exchange rate impact on GDP to isolate the effects of the post-2008 GFC, including in South Africa. The analysis in this paper also improves the specifications of models in Mujahid and Zeb (2014), Kalyoncu et al. (2008a; b), Lubis and Karim (2017), Kamal (2015), Asif (2011), and Christopoulos (2004), by testing the robustness of the results from the parsimonious model to changes in the specification and sample size. We include foreign GDP, domestic consumer prices, the policy rate, and adjust the sample to 2004Q4 to 2019Q4 and isolate the effects of the post-2008 GFC period. Furthermore, this research contributes to the discussions that guide policymakers in finding the appropriate exchange rate policy to stabilize the economy in the long-run. The analysis also contributes to the literature by determining the most important channels that transmitted the exchange rate depreciation shocks to GDP after the GFC, this has not been explored before. This will assist in explaining why South African GDP growth remained low post-2008, impacting the ability to attain the NDP 2030 objectives of raising economic growth through raising exports and investment growth.

Our findings indicate that the parsimonious model can be used to capture the impact of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP in South Africa. The long-run relationship is estimated using the Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS), Dynamic Ordinary Least Squares (DOLS), and the Ordinary Least Squares Methods (OLS). The results show that in the long-run, a one percent exchange rate depreciation raises GDP by less than 1.26 percent in the parsimonious model. Evidence from the linear model which includes the interactive crisis dummy, reveals that the impact of the exchange rate depreciation to stimulate GDP growth was diminished post-2008 GFC. The diminished effects of the exchange rate depreciation in stimulating GDP post-2008 imply South African policymakers cannot rely on the exchange rate depreciation as a potent macroeconomic stabilization policy tool. Evidence from the counterfactual analysis reveals that the exchange rate volatility, foreign demand, investment, imported intermediate inputs, consumption, consumer price level, and export volume channels dampened the stimulative effects of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP post-2008. Thus, the NDP growth objectives of export-led growth and the investment-to-GDP ratio of 30 percent by 2030 may not be reached. Therefore, the current policy orientation and settings must be recalibrated to reflect that the large and persistent exchange rate depreciations post-2008 did not stimulate GDP but instead had contractionary effects. This implies that the current exchange rate policy orientation needs recalibration so that it achieves export-led and higher investment contributions to GDP. This requires concerted efforts to establish the appropriate exchange rate policy to stabilize the economy in the short and long run.

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. “Theory” discusses the theory. Sect. “Methodology” describes the data and shows the unit root test results, Sect. “Data and stylized facts” discusses the methodology. Sect. “Unit root tests and cointegration tests” presents the empirical section and shows the important channels of transmission of the exchange rate depreciation shocks to GDP. Sect. “Results and discussion” concludes that paper and offers policy implications.

Theory

The Keynesian theory postulates that the depreciation of the currency has an expansionary effect on output. The improvement in GDP is shown in Fig. 2 by the shift in the aggregate demand (AD) curve AD0 to AD1 along the aggregate supply curve (SAS).

This occurs when the exchange rate depreciation improves the trade balance and the external sector of the economy, which raises output from Yo to Y1. This also raises prices from P0 to P1. The positive prediction arises in the traditional theories that focus on the role of the elasticities and the absorption approach. However, there are various channels through which the exchange rate depreciation effects are passed onto GDP as depicted in Fig. 3. The exchange rate deprecation can raise the exchange rate volatility, which in turn impacts GDP. In addition, the exchange rate depreciation will raise the domestic prices. In the case where a central bank has a price stability mandate, the authorities of the bank in point will raise the policy rate. Both the exchange rate depreciation and the monetary policy tightening will impact GDP. The other two channels deal with the external sector. The conventional view is that a weaker exchange rate should raise exports, ceteris paribus and the cost of imported materials.

Empirical evidence often presents mixed results of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP. Habib et al (2016), using data from a panel of over 150 countries in the post-Bretton Woods period, concluded that the exchange rates do matter for growth in developing economies, but substantially less so in advanced ones. Kalyoncu et al. (2008a; b) studied the effect of currency devaluation on the output level of 23 OECD countries and found that, in the long run, output growth is affected by currency devaluations in 9 out of 23 countries. Upadhyaya et al (2004) studied the effect of currency depreciation in Greece and Cyprus using panel data. They found that the exchange rate depreciation is expansionary in the short run, but it is neutral in the medium and long run. The Kamal (2015) study for Bangladesh reports mixed results; in the short run, the low exchange rate has a positive significant effect while in the long run output growth is positively affected by the high exchange rate pass-through. In Asian countries, Nusair (2021) found evidence of short-run and long-run asymmetries in the effects of the real exchange rate changes on the domestic output of all the countries.

Sharaf and Shahen (2022, 2023) investigated the asymmetric impact of the real effective exchange rate (REER) depreciation on Egypt’s real domestic output and found that they have a contractionary impact on output in the long run and no impact on output in the short run. Bahmani-Oskooee (1998) investigated the impact of the nominal effective exchange rate devaluation on the output of selected least-developed countries that involved Egypt and found that devaluations have no long-run effects on output in most countries. Upadhyaya and Upadhyay (1999) examined the impact of the exchange rate devaluation on the output of six developing Asian countries and found that it has no impact on output over the short-run, intermediate-run, or long-run. Bahmani-Oskooee and Mohammadian (2017) found that changes in Japan’s exchange rate have asymmetric effects on domestic production. Nusair (2021) investigated the asymmetric impacts of real exchange rates on domestic output in Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand and found evidence of asymmetries in the effects of real exchange changes on the domestic output of all the examined countries in both the short-run and long run.

Bahmani‐Oskooee and Arize (2020) examined the effects of real effective exchange rate changes on the domestic production of 13 African nations. They find that in some countries, depreciation is expansionary, but appreciation has no effect on output. An et al. (2014) examined the impact of real exchange rate changes on the output of 16 countries in Latin American countries, Asian countries, and non-G3 developed countries. They found that contractionary devaluation could happen in developed countries as well as in developing countries.

The impact of the exchange rate volatility on GDP growth has been found to lead to mixed results in Ahmad et al. (2012), Akhtar and Malik (2000), Ali and Anwar (2016), Baron (1976), Bini-Smaghi (1991), Cushman (1983), De Grauwe and Verfaille (1988), Gros (1987), Hasan and Khan (1994), Hassan et al. (2016), Kandil (2008), Kappler et al. (2013), Khan (1995), Masih et al. (2018), Nawaz and Ghani (2018), and Yang 1997. There is compelling evidence indicating that exchange rate volatility impacts GDP growth in developing economies as found in Algaeed and Algethami (2022) in Saudi Arabia by Khan (2021), for Bangladesh in An et al. (2020), and ASEAN by Matthew et al. (2021).

Methodology

The methodology used in the paper focuses on two main aspects to answer the question the question posed. The first step determines the long-run relationship between GDP and the exchange rate using a parsimonious model specification in Mujahid and Zeb (2014), Kalyoncu et al. (2008a; b), Lubis and Karim (2017), Kamal (2015), Asif and Rashid (2010), and Christopoulos (2004). The parsimonious specification is given by Eq. (1) with GDP and the exchange rate. Where \({GDP}_{t}\) denotes the real gross domestic product, and exchange rate is measured by the real effective exchange rate (REER). The exchange rate is inverted so that an increase implies a depreciation. These variables are transformed using the logarithms. In Eq. (1), \({e}_{t}\) is the error term while the coefficient \({\mathrm{\varphi }}^{{\text{LR}}}\) is expected to be positive, which suggests that the exchange rate depreciation raises real GDP when domestic exports become cheaper.

The main focus of the analysis is to determine the long-run impact of the exchange rate on GDP. Hence, we start by determining whether the variables are cointegrated. We use the Johansen cointegration approaches and establish the number of cointegration relationships. We supplement the cointegration approaches with the Engle–Granger test for the short run as given by Eq. (2). We include an inflation targeting dummy variable (IT_dum) in Eq. (2) which takes the value of one from 2000Q1 to the end of the sample and zero otherwise to cater for the impact of the adoption of the inflation targeting framework. We apply the general to a specific approach to determine the number of lags in the models as we drop the insignificant values.

where,

The short-run impact \({\varphi }_{t-i}^{SR}\) in Eq. (2) should be positive, indicating that the exchange rate depreciation raises real GDP in the short run. The coefficient \(\mu\) is expected to be positive which suggests that under inflation-targeting policy framework, the enforcement of price stability should make price setting more transparent enabling investment planning by firms. Hence, some studies find that the adoption of the inflation-targeting policy framework through ensuring macroeconomic price stability leads to improved GDP growth. In Eq. (2), the speed of adjustment (the error correction) \(\gamma\) should lie between 0 and − 1. This indicates that in the long run, the GDP reverts to equilibrium and the disequilibrium corrects at a speed of \(\gamma\) percent per quarter.

Second, we determine the presence of a disconnect between GDP and the exchange rate depreciation effects post-2008 by examining whether the GFC changed the long-run impact of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP. We create a GFC dummy (CRIS) which takes a value of one beginning 2009Q1 to the end of the sample and zero otherwise. The effects of the exchange rate depreciation n GDP post-2008 are captured by the interaction term between the crisis dummy and the exchange rate in Eq. (4). The coefficient \(\theta\) is expected to be negative, implying that the GFC resulted in lower GDP. This happens when workers are laid off which reduces wage income and lowers the consumption expenditure and GDP. The coefficient \({\pi }^{LR}\) captures the impact of the GFC on the long-run elasticity of real GDP to the exchange rate in Eq. (4). A positive \({\pi }^{LR}\) implies that the GFC and the associated economic instabilities amplified the impact of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP. However, a negative \({\pi }^{LR}\) implies that the effect of the exchange depreciation on GDP was dampened by the GFC post-2008, indicating that the exchange rate depreciation effect on real GDP was reduced in the long run.

We further determine the robustness of the GFC effects on the long-run impact of the exchange depreciation by augmenting Eq. (4) with the log G7 GDP (\(\mathrm{log G}7\)) to capture foreign demand, log consumer price \(({\text{log}} {\text{CPI}}\)) to capture the domestic price effects and the policy rate (\(\mathrm{repo rate}\)) to capture the domestic monetary policy effects as given by Eq. (5). The coefficient \(\updelta\) is expected to be negative suggesting that a tightening in the policy rate will make credit expensive, which may lead to cancellations or postponement of investment projects thereby lowering GDP. In addition, raising the policy rate impacts both interest rate sensitive consumption and investment components. When \(\beta <0,\) this suggests that an increase in consumer prices reduces real GDP because rising inflation expectations and inflation uncertainty leads to the misallocation of resources and discourage investment. The coefficient \(\gamma >0,\) indicates that an increase in foreign GDP will lead to high demand for South African goods abroad through increased export growth thereby uplifting the South African GDP.

Third, we determine the important transmission channels for the effects of the GFC post-2008 on the exchange depreciation effects on GDP. We modify the Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) approach to examine the channels that transmitted the exchange rate depreciation effects to GDP post-2008. The focus on the post-2008 period is consistent with Silva (2022) determining the post-GFC effects on the Brazilian municipalities. The channels explored are the exchange rate volatility, foreign demand, investment, imported intermediate inputs, consumer price level, consumption, and export volumes. There are many techniques used in literature to disentangle the role of the transmission channels and these include the counterfactual methods such as those in Pesaran and Smith (2016), Ndou et al (2017), Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015), and Doan (2015). We adopt the Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) estimation technique which consists of two steps in determining the role of the transmission channels. The first step is to estimate a univariate autoregressive GDP equation and, thereafter, derive the relative impulse response functions as in Cerra and Saxena (2008) and Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015). Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) showed the effects of a negative demand shock and the simulated effects of the GFC shocks with the trade and without the trade channels using linear regressions. Similarly, we explicitly account for a possible exchange rate depreciation transmission channel through the GDP. This indirect effect is captured through the terms \(\vartheta\) in Eq. (6). The shape of the impulse response functions depends on the set of the estimated \({\beta }_{i}\), \(\theta\) and \({\vartheta }_{i}\) coefficients in Eq. (6). These are the coefficients for the lagged values of GDP, and those of the financial crisis dummy and channel in question, respectively.

The impulse–response functions to a 1-percentage exchange rate depreciation shock are simulated according to two scenarios. In the first scenario, the transmission channel effects are disregarded so that the \(\vartheta\) parameter does not appear in Eq. (6). In other terms, all the parameters \(\vartheta\) are set to zero suggesting that there are no transmission effects through the indicated channel. This corresponds to the baseline or benchmark case like those considered by Cerra and Saxena (2008) and Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) without transmission channels. In the second scenario, we account explicitly for the exchange rate depreciation transmission channel effects through the \(\vartheta\) parameters in Eq. (6). Thus, the impulse response functions to the exchange rate depreciation are simulated (i) without the transmission channels indicated in Fig. 3, and (ii) with these transmission channels active in the model so that the impulse response functions consider the reaction of GDP through the transmission channel. We run 10,000 bootstrap draws under each scenario and construct the 16th and 84th percentile confidence bands. These confidence bands are indicated by the shaded band around the impulse response function.

Data and stylized facts

We use quarterly (Q) data spanning 1985Q1 to 2019Q3 obtained from the South Africa Reserve Bank and OECD databases. The real GDP is expressed in 2015 constant prices. The real effective exchange rate (REER) is the trade-weighted exchange rate including the relative prices of trading partners. The monetary policy effects are captured by the repo rate which is expressed in percent. The price effects are captured by the consumer price index and foreign demand is measured by the G7 GDP obtained from OECD measured in 2015 constant prices.

We begin by examining the link between the exchange rate and GDP. Figure 4 shows the trends of real GDP, and the real effective exchange rate (REER). The increase in the exchange rate (REER) denotes an appreciation. The downward slopes in Fig. 4b show a negative relationship between the real GDP and the REER. This preliminary analysis suggests that there is a negative relationship between real GDP and the REER.

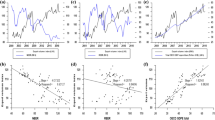

The slope of the bilateral association between the rand per US dollar (R/US$) exchange rate changes and GDP growth has changed during the period 2000Q1 to 2019Q4 as shown in Fig. 5b. It was positive between 2000Q1 and 2007Q4, indicating the expansionary effects of the exchange rate depreciation. The relationship turned negative for the period 2008Q1 to 2019Q4, suggesting that the exchange rate depreciation had contractionary effects.

At the same time, on a bilateral basis in Fig. 6b, import growth explains about 55 percent of the variation in GDP, whereas export growth explains 42 percent in Fig. 6d.

The investment-to-GDP ratio declined post-2008 as shown in Fig. 7 and remains well below the 30 percent target of the NDP by 2030.

Unit root tests and cointegration tests

The stationarity tests in Table 1 reveal that real GDP and the REER are I (1) and become stationary after differencing once.

We apply the Johansen cointegration tests to determine if there are any cointegrated relationships between real GDP and the REER. The cointegration relationships are estimated by a VAR which includes real GDP and the REER and two lags as determined by the HQ criteria. The Johansen cointegration test in Table 2 indicates that there is one cointegrating relationship. The long-run relationship is estimated in levels form using the FMOLS, OLS, and DOLS. The three methods are used to determine the robustness of this long-run relationship.

Results and discussion

Table 3 shows the long-run and short-run effects of the REER depreciation on real GDP estimated using OLS, FMOLS, and DOLS. The elasticity of GDP to the REER is 1.2 percent, suggesting that a 1 percent REER depreciation raises GDP by 1.2 percent in the long run. In the short run, a 1 percent REER depreciation raises real GDP by less than 0.03 percent. This implies that the exchange rate depreciation has a bigger impact on GDP in the long run compared to the short run. In addition, the size of the error correction mechanism shows that less than 0.5 percent of the disequilibrium is eliminated within each quarter in the short run. The results are robust to the three estimation techniques.

The impact of the global financial crises on the link between the exchange rate and GDP

We examine the impact of the GFC by assessing the impact of the \(CRIS\) dummy on the REER depreciation effects on GDP. We estimate Eqs. (4) and (5). Table 4 shows the estimated coefficients including the interactions of (CRIS* logREERt) for the REER. In Table 4, the coefficient of the \(CRIS\) dummy is negative in all columns. The negative sign implies that the GFC (\(CRIS\)) reduced the mean level of real GDP. This happens through channels explained in Kouki and Belhadj (2017) linked to losses from a decline in capital stock, an increase in unemployment, deterioration of economic conditions, a weakening of supply and demand, diminished investment and credit capacity, a decline in consumption, a decline in demand for goods and services. The decline in income weakens the solvency of banks through declining savings, which leads to tighter lending criteria. In addition, a financial crisis accompanied by elevated exchange rate volatility reduces the volume of trade by raising risk-adjusted expected profits on future deliveries which then impacts the firms’ profits and trade volume (Arize 1996; Ndou et al 2017). The adverse effects of the crisis have been reported by Hutchison (2001), in which the currency crisis reduced production by 5 to 8 percent during the first 3 years. In addition, Hutchison (2001) and Barro (2001) found that the currency crisis led to a loss of 1.3 percent in real GDP growth and 0.4 percent in investment. While the banking crisis reduces GDP growth per capita by 0.6 percent per year and investment by 0.9 percentFootnote 1 Boyd et al. (2005) showed that banking crises reduce real GDP per capita by 63 percent.

The coefficient of CRIS* logREERt is negative and significant at 5 percent, which suggests the diminished or weak impact of the REER depreciation effects on GDP. The results suggest that the GFC dampened the effects of the REER depreciation on GDP. The findings are robust to different model specifications and using the sample period spanning 2004Q1 to 2019Q4.Footnote 2 Ndou et al (2017) found that the contractionary effects of the exchange rate depreciation on investment result from the balance sheet effects dominating the competitiveness effects in South Africa. This dominance arises from firms having liabilities in foreign currency which induce a currency mismatch in the balance sheet during periods of financial stress in a crisis following a severe exchange rate depreciation shock. The depreciation weakens the firm’s net worth and creditworthiness and limits firms in accessing credit markets as fundraising becomes expensive deterring investment accumulation which impedes real GDP growth (Ndou et al 2017).

These adverse effects due to the crisis on the long-run impact of the REER depreciation on GDP may also be linked to increased risk premiums during periods of elevated economic distress. The economic crisis erodes creditworthiness which raises the bond premia, and the cost of capital, triggering a prolonged decline in investment activity (Gilchrist et al. 2010). Furthermore, the elevated macroeconomic uncertainties during the economic crisis affect the decisions of lending institutions, the likelihood of borrower defaults, strategies for lending decisions, screening customers, deciding on the best value to allocate credit, difficulties for lending institutions to allocate credit, and increased information asymmetry which increase credit risks (Chi and Wi 2017). As indicated by Ndou et al (2017), the heightened credit risk affects lending decisions, financial conditions, cost of debt, credit supply, and increases operational risk which in turn increases the fluctuations in firms’ operations, making the financial situation unstable and impact on capital for investment and declining output.

We show the robustness testing of the effects of the GFC on the exchange rate depreciation impact on GDP in Table 4 columns 3 and 4. In both columns, an increase in foreign GDP raises SA GDP as postulated by theoretical expectations. A one percent increase in CPI significantly lowers GDP by 0.458 percent in column 2. Rising CPI lowers GDP because of elevated inflation uncertainty which reduces the information function of price movements and hinders long-term contracting which reduces real economic growth (Friedman 1977). Increased inflation uncertainty distorts the effectiveness of the price mechanism in allocating resources leading to lower output. Ndou et al. (2017) found evidence that high inflation lowers real GDP, and the decline is accentuated by rising inflation uncertainty and economic policy uncertainty in South Africa. Furthermore, the adverse effects arise as pointed out in Lelland (1968) and Kimball (1990) that rising inflation triggers inflation uncertainty and uncertainty about the future streams of labour income and dividends making households raise their precautionary savings, lowering consumption expenditure and aggregate demand.

An increase in the policy rate lowers GDP as monetary policy tightening leads to tighter financial conditions and lending standards which restrain credit extension. The reduced credit extension constrains the financing of new and existing capital investment projects and real GDP growth. In addition, higher interest rates lower house prices but raise the burden of variable interest rates, leaving consumers with less income for consumption leading to reduced output.

The channels of transmission of the exchange rate depreciation shocks to GDP

Our focus on the post-2008 period is due to the Rajan and Shen (2006) postulation that some currency crises characterised by huge depreciation or devaluations are followed by economic contractions while others are not. Their evidence indicates the different output effects of the exchange rate devaluation or depreciation between periods of tranquillity (non-crisis) and crisis. Such distinction between crisis and non-crisis periods showed that contractionary devaluations and depreciations are more prevalent during the crisis period, especially following banking crises and periods of elevated short-term debt. Rajan and Shen (2006) pointed out that during non-crisis periods real exchange rate depreciations are seen as an important policy option for promoting export growth and output growth. Based on the predictions of conventional theory, Bahmani-Oskooee and Miteza (2006) pointed out that the IMF adjustment programs have used the exchange rate depreciation policy as a stabilization device in emerging economies. This follows indications in Domac (1997) that exchange rate depreciation is believed to be the primary policy option for the stabilization of the balance of payments. However, these authors argue that the proposition that exchange rate depreciation is stimulatory has met challenges from theoretical studies and historical facts that indicate that depreciations are contractionary.

We apply the Pentecôte and Rondeau (2015) approach to examine the channels that transmit the exchange rate depreciation shocks to real GDP using the models given by Eq. (6).

The role of the investment channel

The role of the investment channel is captured by the gross fixed capital formation. Figure 8c shows the response of GDP and the role of the investment channel in transmitting the REER depreciation shocks.

The results show that GDP rises less when the investment channel is included in the model compared to the counterfactual. In Fig. 6b, the GDP increase insignificantly throughout all horizons when including capital formation. This may be due to exchange rate deprecation adversely impacting on investment via the foreign debt channel as found in Ndou et al (2017). Figure 6d shows the gap due to the investment channel which dampens the increase in GDP due to the exchange rate depreciation shock. This happens as a high degree of the firms’ liabilities are denominated in foreign currency and the currency mismatch in the balance sheet during a financial crisis dominates the competitiveness channel in the aftermath of severe currency depreciation Ndou et al (2017). The deteriorations in the firm’s net worth and creditworthiness during periods of elevated financial stress, limit the firm’s access to credit markets as raising funding becomes expensive which lowers investment and aggregate demand.

The imported intermediate inputs channel

In Fig. 9b, the GDP increase insignificantly throughout all horizons when including imported intermediate inputs. This may be due to exchange rate deprecation raising costs of intermediate inputs which weigh down on GDP as found in Ndou et al. (2017). Figure 9c shows that imported intermediate inputs channel dampen the increase in GDP due to the exchange rate depreciation shock.

The contractionary effects of large real exchange rate depreciation on imported intermediate inputs are linked to the rising cost of inputs following the depreciation. According to Montiel (1996) and Reif (2001) when a large fraction of imports is highly inelastic to changes in relative prices as is the case with imported inputs and capital goods, the high costs of inputs and capital goods can offset the positive gains in the export or tradable sector leading to lower real GDP. In addition, Harchaoui et al. (2005) indicate that the severity of the exchange rate depreciation and its volatility harms intermediate goods and investment, which in turn increases the variable cost of production, and the user cost of capital thereby reducing the marginal profit of the investment.

The consumption channel

We examine the role of the consumption channel in transmitting exchange rate depreciation shocks to GDP. Alexander (1952) postulates that the exchange rate devaluation or depreciation can reduce the consumption component of aggregate demand thus offsetting the impact of the increase in net exports in GDP. In Fig. 10b, the GDP increase insignificantly throughout all horizons when including household consumption expenditure. This may be due to exchange rate deprecation raising the costs of fuel or energy which reduces consumption expenditure as found in Ndou et al. (2017). Figure 10c shows that the rise in GDP due to the exchange rate depreciation shock was dampened by the consumption channel. Furthermore, Alexander (1952) indicates the income is redistributed from the workers with a high marginal propensity to consume (MPC) to producers with low MPC, which lowers consumption. Hence the overall effect of the exchange rate depreciation is a decline in consumption and lower economic growth. Kose and Terrones (2012) indicate that the adverse effects of uncertainty tend to be transmitted through financial market imperfections and frictions including debt costs. The increase in market frictions due to a crisis may reduce credit demand and approvals which lowers credit-driven consumption and aggregate demand.

The dampening effect of the consumption channel happens when wages do not fully adjust to inflation due to the exchange rate depreciation leading to a decline in the workers’ MPC.

The inflation channel

Fourth, we examine the role of the consumer price inflation channel in transmitting the exchange rate depreciation. Figure 11b shows that GDP rises insignificantly when consumer price inflation is included in the model than when it is shutoff. The impulse response of GDP is higher when consumer price inflation is excluded from the model than when it is active in the model. Figure 11d shows that consumer price inflation dampens the increase in GDP growth due to the exchange rate depreciation shock. These adverse effects arise when inflation increases uncertainty which reduces investment due to the irreversibility of investment and this leads to reduced output growth. This irreversibility hinges on the theoretical model assumptions embedding the role of physical adjustment frictions (Bernanke 1983; Dixit and Pindyck 1994). The interaction between high uncertainty and non-smooth adjustment frictions leads firms to behave cautiously via a “wait and see” approach, which pauses hiring and investment. The attrition, during the “wait and see” period triggers a decline in investment and real economic activity. Apart from the “wait and see” effects, heightened inflation uncertainty due to high inflation leads to an increase in debt service costs. According to Golob (1994) and Ndou et al (2017), inflation uncertainty affects financial markets by raising long-term interest rates and the inflation risk premium. Thus, the elevated uncertainty about future prices and interest rates encourages the use of fixed long-term rates which are typically higher than short-term interest rates thereby lowering real GDP. Furthermore, Haddow et al. (2013) show increased inflation uncertainty brings risks to future demand prospects, impacting on the spending patterns, investment growth, consumption changes, credit, consumer confidence, costs of servicing debt, and disposable income.

The foreign output channel

The foreign output channel is captured by the G7 GDP and the results in Fig. 12b show that the GDP rises insignificantly when foreign output is included in the model than when it is shutoff. The impulse responses of GDP in Fig. 12c are higher when foreign output is excluded from the model compared to when it is active in the model. Figure 12d shows that the foreign output channel dampens the increase in GDP growth due to the exchange rate depreciation shock. This suggests that weaker foreign demand dampened the response of domestic output due to the exchange rate depreciation.

The exchange rate volatility channel

The exchange rate volatility is measured by the two-quarter moving standard deviation of the REER. Figure 13a indicates that GDP rises insignificantly when the exchange rate volatility is included in the model compared to when it is shutoff. In Fig. 13b, the GDP increase insignificantly throughout all horizons when including exchange rate volatility. This may be due to exchange rate deprecation raising volatility which makes it difficult for companies to plan properly, such that high volatility lowers investment as found in Ndou and Gumata (2017). The impulse responses of GDP in Fig. 13c are higher when the exchange rate volatility channel is shutoff in the model than when it is active. Figure 13d shows that the exchange rate volatility dampens the increase in GDP growth due to the exchange rate depreciation shock as the increase in the exchange rate volatility reduces the volume of trade by inducing risk in profits on future deliveries as well as inability to diversify the exchange rate risk or those who see hedging as expensive or impossible (Arize 1996). Caldara et al. (2016) show that the increase in uncertainty is associated with financial shocks, linked to widening of credit spreads which affect insurance premiums for export contracts deterring exports and real GDP growth.

The export channel

Figure 14 shows that GDP rises significantly when the export channel is included compared to when it is shutoff in the model. The increase in GDP is bigger when the export channel is shutoff. The results suggest that the trade channel dampened the increase in GDP following exchange rate depreciation as the crisis dampened foreign demand for exports.

Conclusion and policy implications

This paper estimated the long-run impact of the REER depreciation on GDP in South Africa and whether it changed after the GFC. The paper further determines whether certain channels amplified or dampened the transmission of the REER deprecation effects on GDP post-2008. Our findings indicate that the parsimonious model can be used to capture the impact of exchange rate depreciation on GDP in South Africa. The long-run relationship indicates that a one percent exchange rate depreciation raises GDP by less than 0.5 percent. Whereas evidence from the linear model which includes the interactive dummy, reveals that the impact of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP was diminished post-2008. Evidence from the counterfactual analysis shows that the exchange rate volatility, foreign demand, investment, imported intermediate inputs, consumption, consumer price level, and export volume channels dampened the stimulative effects of the exchange rate depreciation on GDP post-2008. This evidence indicates a disconnect and a very weak relationship between the REER depreciation and GDP growth and implies that policymakers cannot rely on the exchange rate depreciation as a potent macroeconomic stabilization policy tool and may not achieve the NDP growth objective via export-led and investment growth strategy. The current policy orientation and settings must be recalibrated to reflect that the large and persistent exchange rate depreciation resulted in contractionary effects and did not stimulate GDP growth. This implies that the current exchange rate policy orientation needs recalibration so that it achieves export-led and higher investment contributions to GDP growth. This requires concerted efforts to establish the appropriate exchange rate policy to stabilize the economy in the short and long run.

The paper focused on the long-run effects of the REER depreciation on GDP in South Africa. However, policy debates are also grappling with the distinct asymmetric effects of the exchange rate appreciations and depreciations on GDP due to mixed empirical evidence. Current studies have not examined whether the asymmetric exchange rate effects exist during periods of crisis. Our future studies will focus on the nonlinear and asymmetric responses of GDP growth due to the exchange rate appreciation and depreciations, and whether there are differences during crisis and non-crisis periods.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author, upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from the author, upon reasonable request.

Notes

Gupta, Mishra and Sahay (2007) found that 60 percent of the detected 195 currency crisis episodes lead to recessions and the level of foreign debt is likely to amplify the consequences of crises following strong devaluations.

The results are in Appendix A.

References

Ahmad N, Hayat MF, Luqman M, Ullah S (2012) The causal links between foreign direct investment and economic growth in Pakistan. Eur J Bus Econ 6:20–211. https://doi.org/10.12955/ejbe.v6i0.137

Akhtar S, Malik F (2000) Pakistan’s trade performance vis-a-vis its major trading partners. Pak Dev Rev 39(1):37–50. https://doi.org/10.30541/v39i1pp.37-50

Alexander SS (1952) Effects of a devaluation on a trade balance. IMF Staff Pap 2(2):263–278

Algaeed AH, Algethami BS (2022) Monetary volatility and the dynamics of economic growth: an empirical analysis of an oil-based economy, 1970–2018. OPEC Energy Review

Ali SZ, Anwar S (2016) Can exchange rate pass-through explain the price puzzle? Econ Lett 145:56–59

An L, Kim G, Ren X (2014) Is devaluation expansionary or contractionary: evidence based on vector autoregression with sign restrictions. J Asian Econ 34:27–41

An PTH, Binh NT, Cam HLN (2020) The impact of exchange rate on economic growth case studies of countries in the ASEAN region. Global J Manag Bus Res 9(7):965–970

Arize AC (1996) Real exchange-rate volatility and trade flows: the experience of eight European economies. Int Rev Econ Financ 5:187–205

Asif A, Rashid K (2010) Time series analysis of real effective exchange rates on trade balance in Pakistan. J Yasar Univ 5(18):3038–3044

Bahmani-Oskooee M (1998) Are devaluations contractionary in LDCs? J Econ Dev 23(1):131–144

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Arize AC (2020) Asymmetric response of domestic production to exchange rate changes: evidence from Africa. Econ Chang Restruct 53(1):1–24

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Miteza I (2006) Are devaluations contractionary? Evidence from panel cointegration. Economic Issues 11(1):49–64

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Mohammadian A (2016) Asymmetry effects of exchange rate changes on domestic production: evidence from nonlinear ARDL approach. Aust Econ Pap 55(3):181–191

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Mohammadian A (2017) Asymmetry effects of exchange rate changes on domestic production in Japan. Int Rev Appl Econ 31(6):774–790

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Mohammadian A (2018) Asymmetry effects of exchange rate changes on domestic production in emerging countries. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 54(6):1442–1459

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Iqbal J, Khan SU (2017a) Impact of exchange rate volatility on the commodity trade between Pakistan and the US. Econ Chang Restruct 50(2):161–187

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Iqbal J, Muzammil M (2017b) Pakistan-EU commodity trade: Is there evidence of J-curve effect? Glob Econ J 17(2):20160067

Bahmani-Oskooee M, Nosheen M, Iqbal J (2017c) Third-country exchange rate volatility and Pakistan-US trade at commodity level. Int Trade J 31(2):105–129

Baron DP (1976) Fluctuating exchange rates and the pricing of exports. Econ Inq 14(3):425–438

Barro R (2001) Economic Growth in East Asia Before and After the Financial Crisis. NBER Working Paper. 8330

Bernanke (1983) Irreversibility, uncertainty and cyclical investment. Q J Econ 98(1):85–106

Boyd JH, Kwak S, Smith B (2005) The real output losses associated with modern banking crises. J Money, Credit, Bank 37(6):977–966

Boz E, Casas C, Georgiadis G, Gopinath G, Le Mezo H, Mehl A Nguyen T (2020) Patterns in Invoicing Currency in Global Trade. IMF Working Paper WP/20/126

Caldara D, Fuentes-Albero C, Gilchrist S, Zakrajšek E (2016) The macroeconomic impact of financial and uncertainty shocks. Eur Econ Rev 88:185–207

Cerra V, Saxena S (2008) Growth dynamics: the myth of economic recovery. Am Econ Rev 98:439–457

Chi Q, Wi W (2017) Economic policy uncertainty, credit risks and banks’ lending decisions evidence from Chinese commercial banks. China J Account Res 10:33–50

Christopoulos DK (2004) Currency devaluation and output growth: new evidence from panel data analysis. Appl Econ Lett 11:809–813

Clarida R, Gali J (1994) Sources of real exchange-rate fluctuations: how important are nominal shocks? Carn-Roch Conf Ser Public Policy 41:1–56

Cushman DO (1983) The effects of real exchange rate risk on international trade. J Int Econ 15(1–2):45–63

Dixit A, Pindcky R (1994) Investment under uncertainty. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Doan T (2015) RATS Handbook for Vector Autoregressions, Estima 2nd Edition April 7, 2015

Domac I (1997) Are devaluations contractionary? Evidence from Turkey. J Econ Dev 22(2):145–163

Dornbusch R (1988) Open economy macroeconomics, 2nd edn. Basic Books, New York

Dornbusch R, Krugman P, Cooper RN (1976) Flexible exchange rates in the short run (Brookings Papers on Economic Activity No. 3

Easterly W, Levine R (1997) Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Quart J Econ 112(4):1203–1250

Fischer S (1992) Macroeconomic stability and growth. Cuadernos De Economía 29(87):171–186

Gilchrist S, Sim J, Zakrajsek E (2010) Uncertainty, financial frictions and investment dynamics (2010 Meetings Papers No. 1285). Society for Economic Dynamics

Golob JE (1994) Does inflation uncertainty increase with inflation, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review

De Grauwe P, Verfaille G (1988) Exchange rate variability. In Misalignment of exchange rates: Effects on trade and industry (pp. 77–104). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8055.pdf

Gros D (1987) Exchange rate variability and foreign trade in the presence of adjustment costs (Working paper Département des Sciences Economiques No. 2619075–8). Exchange rate variability and foreign trade in the presence of adjustment costs

Gupta P, Mishra D, Sahay R (2007) Behavior of output during currency crisis. J Int Econ 72(2):428–450

Habib MM, Mileva E, Stracca L (2016) The real exchange rate and economic growth: revisiting the case using external instruments, Working paper, No 1921

Haddow A, Hare C, Hooley J, Shakir T (2013) Macroeconomic uncertainty; what is it, how can we measure it and why does it matter? Bank Engl Quart Bull 53:100–109

Harchaoui TM, Tarkhani F, Yuen T (2005) The effects of the exchange rate on investment: evidence from canadian manufacturing industries. Staff Working Papers 05-22, Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/wp05-22.pdf

Hasan MA, Khan AH (1994) Impact of devaluation on Pakistan’s external trade: an econometric approach. Pak Dev Rev 33(4):1205–1215

Hassan BD, Fausat AF, Baba YA (2016) Impact of monetary policy in Nigeria on inflation, exchange rate and economic growth. Int J Econ Bus Manag 2(5):67–82

Hutchison MA (2001) Cure Worse than the Disease? Currency Crises and the Output Costs of IMF-Supported Stabilization Programs. NBER Working Paper, No. W8305

Iqbal A, Nosheen M, Wohar M (2022a) Revisiting the asymmetry between the exchange rate and domestic production in South Asian economies: evidence from nonlinear ARDL approach. Econ J Emerg Markets 14(2):162–175

Iqbal J, Aziz S, Nosheen M (2022b) The asymmetric effects of exchange rate volatility on US–Pakistan trade flows: new evidence from nonlinear ARDL approach. Econ Chang Restruct 55(1):225–255

Kalyoncu H, Artan S, Tezekici S, Ozturk I (2008a) Currency devaluation and output growth: an empirical evidence from OECD countries. Int Res J Finance Econ 14:232–238

Kalyoncu H, Artan S, Tezekici S, Ozturk I (2008) Currency devaluation and output growth: empirical evidence from OECD countries. Int Res J Finance Econ 14

Kamal KM (2015) An ECM approach for long run relationship between real exchange rate and output growth: evidence from Bangladesh. Dhaka Univ J Sci 63(2):105–110

Kandil M (2008) The asymmetric effects of exchange rate fluctuations on output and prices: evidence from developing countries. J Int Trade Econ Dev 17(2):257–296

Kappler M, Reisen H, Schularick M, Turkisch E (2013) The macroeconomic effects of large exchange rate appreciations. Open Econ Rev 24(3):471–494

Khan SR (1995) Devaluation and balance of trade in Pakistan: A policy analysis (Research Report Series No. 7). April: Paper presented at the Eleventh Annual General Meeting and Conference of Pakistan Society of Development Economists

Khan MFH (2021) Impact of exchange rate on economic growth of Bangladesh. Eur J Bus Manag Res 6(3):173–175

Kimball MS (1990) Precautionary saving in the small and in the large. Econometrica 58(1):53–73

Knight M, Loayza N, Villanueva D (1993) Testing the neoclassical theory of economic growth: a panel data approach. Staff Papers (international Monetary Fund) 40(3):512–541

Kose A, Terrones M (2012) How does uncertainty affect economic performance? World Economic Outlook, pp. 49–53

Kouki M, Belhadj R, Chikhaoui M (2017) Impact of financial crisis on GDP growth: the case of developed and emerging countries. Int J Econ Financ 7(6):212–221

Lelland H (1968) Savings and uncertainty: the precautionary demand for saving. Q J Econ 82:465–473

Lubis MRG, Karim NAA (2017) Exchange rate effect on gross domestic product in the five founding members of ASEAN. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 7(11):1284–93

Masih J, Liu D, Pervaiz J (2018) The relationship between RMB exchange rate and Chinese trade balance: evidence from a bootstrap rolling window approach. Int J Econ Financ 10(2):35–47

Montiel PJ (1996) Financial policies and economic growth: theory, evidence and country-specific experience from Sub-Saharan Africa. J Afr Econ 5(3):65–98

Most SJ, De Berg HV (1996) Growth in Africa: does the source of investment financing matter? Appl Econ 28(11):1427–1433

Mujahid N, Zeb A (2014) Impact of devaluation on GDP of Pakistan. Int J Econ Empir Res 2(8):345–349

Ndou E, Gumata N, Ncube M (2017) Global economic uncertainties and exchange rate shocks: transmission channels to the South African economy, Palgrave Macmillan

Ndou E, Gumata N, Ncube M (2019) Global Economic Uncertainties And Exchange Rate Shocks Transmission Channels to the South African Economy, Palgrave Macmillan

Nusair SA (2021) The asymmetric effects of exchange rate changes on output: evidence from Asian countries. Th

Pentecôte J, Rondeau F (2015) Trade spillovers on output growth during the 2008 financial crisis. Int Econ 143:36–47

Pesaran MH, Smith RP (2016) Counterfactual analysis in macroeconometrics: an empirical investigation into the effects of quantitative easing. Res Econ 70(2):262–280

Rajan RS, Shen C-H (2006) Why are crisis-induced devaluations contractionary? Exploring alternative hypothesis. J Econ Integr 21:526–550

Reif T (2001) The real side of currency crises. Mimeo. Columbia University

Semosa PD, Aphane MI (2017) The Impact of Exchange Rate and Exports on Economic Growth of South Africa, The 2nd Annual International Conference on Public Administration and Development Alternatives 26–28 July 2017, Tlotlo Hotel, Gaborone, Botswana

Sharaf M, Shahen A (2022) Asymmetric impact of real effective exchange rate changes on domestic output revisited: evidence from Egypt, Working Paper No. 2022-06, University of Alberta, Department of Economics

Sharaf M, Shahen A (2023) Asymmetric impact of real effective exchange rate changes on domestic output revisited: evidence from Egypt. Int Trade Polit Dev 7(1):2–15

Tian Y, Pentecost EJ (2019) The changing sources of real exchange rate fluctuations in China, 1995–2017: twinning the western industrial economies? Chin Econ 52(4):358–376

Upadhyaya KP, Upadhyay MP (1999) Output effects of devaluation: evidence from Asia. J Dev Stud 35(6):89–103

Upadhyaya KP, Mixon FG, Bhandari R (2004) Exchange rate adjustment and output in Greece and Cyprus: evidence from panel data. Appl Financ Econ 14:1181–1185

Yang J (1997) Exchange rate pass-through in US manufacturing industries. Rev Econ Stat 79(1):95–104

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of South Africa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ndou, E., Gumata, N. & Moletsane, T. Exchange rate and GDP nexus in South Africa: the disconnect after the 2008 global recession. SN Bus Econ 4, 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00613-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00613-2