Abstract

The world of audiovisual online markets is rapidly changing. Not long ago, it was dominated by linear television, transmitted terrestrially, through cable networks or via satellite. Recently, streaming services such as Netflix, YouTube, Amazon Prime and others have emerged as new suppliers of audiovisual content. In this quickly changing industry, competition interrelations between such different formats such as traditional TV, videos on YouTube, and streaming via Netflix are subject to controversy. In particular, doubt is cast on services such as YouTube exerting competitive pressure on services such as Netflix and traditional TV. Based upon a survey with 2920 participants, we provide an empirical analysis of consumption behavior of audiovisual contents. Using descriptive and analytical statistics, including multiple equation models, we show that there are specific areas within audiovisual content markets, where YouTube exerts considerable competitive pressure on both Netflix and classic TV, for instance, through prime time video entertainment. However, our analysis yields differentiated results as we also identify areas, where competition intensity between different service types appear to be low, for instance, through daytime and regarding the intention to shorten waiting time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The consumption of audiovisual content is rapidly changing. While traditional television (TV) still dominates the consumption of audiovisual contents of an older age audience, the younger ages already devote more time to consuming audiovisual contents via online streaming services and video portals, such as Netflix or YouTube (also referred to as video-on-demand; VoD). This development is also driven by an increased use of mobile devices, such as smartphones and tablets, allowing for considerably enhanced options of consuming audiovisual contents in not only the living room at home but also virtually everywhere and every time. User figures and viewing numbers from various countries show that particularly younger generations extensively use portals such as YouTube and watch online streaming services such as Netflix, whereas older age groups (50 + years) significantly less switch on these services (see, inter alia, for Germany Lindstädt-Dreusicke & Budzinski 2020, for Scandinavia Audience Project 2019, for the UK Fisher 2019, and for the US Richter 2019). At the same time, traditional TV is not only relatively stronger with the older population (e.g., due to a lack of mobile consumption of non-TV contents, such as YouTube videos) but also in absolute terms. In 2019, the average daily viewing time of TV in the 50 + age groups amounted to 318 min per day, whereas the 30–49 years watched 176 min per day and the 14–29 years only 82 min per day. In addition, consumption time in the older age group slightly increased, whereas it decreased in the younger age clusters, particularly within the 30–49 years (− 18 min per day compared to previous year) (Statista 2020). Thus, the figures do not allow disentangling how much of the dynamics results from complementary services in the mobile online world and how much from viewers abandoning traditional TV and switching to various VoD formats.

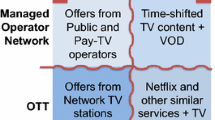

The currently relevant online services differ in terms of business models from both traditional TV and from each other. In terms of business models, advertised-financed streaming services (AVoD; e.g., YouTube) can be distinguished from paid-for (by users) streaming services (PVoD; e.g., Netflix) (Lindstädt-Dreusicke & Budzinski 2020). While it is possible that streaming services mix these models (i.e., hybrid models, such as Spotify is doing in respect to audio streaming services), at the time of our empirical analysis (winter 2018/19), the relevant suppliers in the German market were predominantly devoted to one of the two models.Footnote 1 Obviously, business models will develop and change along with the high dynamics of the markets in question. Therefore, for the purpose of our analysis, we decided to directly pick two of the most prominent online services for the consumption of audiovisual contents, namely YouTube and Netflix, and compare them to traditional TV (the latter with almost no dynamics regarding the main providers; Budzinski & Lindstädt-Dreusicke 2020). While YouTube was and remains an obvious choice in the AVoD arena, choice is not that obvious regarding PVoD-services. According to the Audience Project (2019), Netflix is taking the leading position among the most used streaming and downloading services for the US, UK, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. For the US and Germany, Netflix is followed by Amazon Prime Video, whereas in the UK the BBC iPlayer takes the second position from Amazon Prime Video. In the Scandinavian countries, by contrast, Amazon Prime Video plays a smaller role. Virtually all available market share figures assume separate markets for services, such as YouTube and PVoD streaming services (thus, ignoring YouTube when calculating shares for Netflix and co). As of October 2019, market shares according to subscription figures in Germany display Amazon Prime Video (47%) leading from Netflix (36%) with other providers clearly lacking behind (e.g., Sky with 5.9%) (Herrmann 2019). However, Amazon ties its Prime subscription to a bundle of different services (e.g., free shipping, next day delivery, music streaming, video streaming), thus, it is not clear how many people exactly use Amazons VoD offer (El Khaoudi 2018). Based on daily usage figures, Netflix is leading the market in Germany, followed by Amazon Prime Video (Herrmann 2019).

Despite the differences in content, business models and treatment by available empirical studies, at the end of the day, all of TV, AVoD and PVoD are offering audiovisual contents to the consumers. In the light of the increasing importance of online streaming services vis-à-vis traditional TV, therefore, the questions arise whether relevant competitive pressure between the services (in our study represented by YouTube, Netflix, TV) exists. There are some empirical studies that take a closer look at the comparison of traditional audiovisual content (i.e., TV) and audiovisual on-demand services. While previous studies researched the relationship between PVoD and traditional TV (Shelton et al. 2016; Prince & Greenstein 2017; McKenzie et al. 2019), AVoD services à la YouTube were not considered. By contrast, some of them distinguish different types of traditional TV (by transmission (free-to-air, cable, satellite) and/or by payment model) or include cinemas—something we are not doing due to our focus on VOD types. In Chen (2019) and Fudurić et al. (2020), AVoD such as Hulu (partially including advertising) or YouTube is included in the OTT reflection; however, AVoD and PVoD platforms are not explicitly differentiated. Furthermore, Fudurić et al. (2020) use household level data, thus, do not explicitly consider individual consumption of audiovisual content when examining the effects of OTT on cable TV cord shaving behavior. Spilker et al. (2020), by contrast, focus on a comparison of Twitch and traditional TV, thus, AVoD is considered; however, PVoD services are not included in the analysis. In sum, none of the studies mentioned above, thus, differentiate specifically between TV, PVOD and AVoD elaborating the relationship between these three different forms of audiovisual content provision for audiences. Our research article contributes to tackling this research gap. For doing so, we specify the following research questions: Does the intensity of competitive pressure between services depend on specific characteristics of demand, i.e., (1) for whom (e.g., age groups), (2) for what purposes (e.g., genre, motivation/intention), and (3) during what time of the day (e.g., prime time)? To tackle our research questions, we empirically analyze the audiovisual viewing patters by employing an econometric analysis based on a quantitative online survey in Germany. With a unique data set of 2920 participants, we are able to provide differentiated results on age groups, choices through different times of day and consumption differences regarding genres and intentions. The rich data set provides wide information on stated and pseudo-revealed preferencesFootnote 2 of respondents, i.e., direct answers stating the respondent’s opinion and preferences in agreement with self-perception vs. indirect questions revealing preferences and ideas the respondent might not directly be aware of. We are able to show that those preferences diverge. While consumers state that YouTube-style AVoD does not represent an alternative to Netflix-style PVoD for them, the consumption habits described by the respondents indicate the opposite for prime-time consumption. In general, the results support the notion that consumers with limited time capacities need to decide between competing ways to get entertained. Especially the decision of evening and prime-time entertainment is not trivial and shows that consumers do not clearly prefer one distinctive medium, displaying a strong competitive relation. In contrast, consumption of specific genres, for instance, sports or news hints at less competitive relations.

The paper is organized as follows: “Theory: competition among different channels of audiovisual content” summarizes the theoretical background. Then, “Empirical analysis: methodology and data” explains the methodology of sampling and analysis and “Empirical analysis: results and discussion” presents the empirical analysis. Based upon the results, “Summary and limitations” discusses implications and “Conclusion and implications” concludes.

Theory: competition among different channels of audiovisual content

The ongoing process of digitization and the spread of broadband internet technology considerably increased the option for consumers to watch moving audiovisual contents. That traditional TV—irrespective of its transmission media (terrestrial, cable, satellite, online, etc.)—is now facing video-on-demand services changes the competitive landscape. This may be good news, since in many national television markets (including Germany), concentration and (a lack of) competition have been continuous concerns (Budzinski & Wacker 2007; Bundeskartellamt 2011a, 2011b, 2015; OFCOM 2018). However, the competitive interrelations between TV and VoD as well as among different types of VoD services are subject to controversial discussionFootnote 3 (and as mentioned in “Introduction”, most empirical studies ignore YouTube when they discuss VoD markets). Thus, what are the theoretical reasonings about factors influencing the competitive interrelation of different channels transmitting audiovisual contents (TV, different types of VoD)?

Fundamental differences in content

Fundamental differences in the type of content that is broadcasted may limit the intensity of competition between Netflix, YouTube, and TV. An often-raised objection claims a service such as YouTube (AVoD) does not compete with the likes of traditional TV and PVoDs, such as Netflix, because its content is predominantly non-professional and/or non-commercial (inter alia, Bruns 2008; Ritzer & Jurgenson 2010; Bundeskartellamt 2011a, 2015; Dennhardt 2014; Fuchs 2014). According to this view, YouTube mainly represents a social media platform, where users upload content for other users (cat videos, fail videos, etc.), i.e., a sort of user-exchange of contents, and professional contents from business companies are in the clear minority. The nature of YouTube’s early ‘user generated content’ (from users for users) has changed a lot and initial ‘private’ uploaders professionalized towards being active content providers, offering regular video uploads regarding specific topics according to the channel’s media concept (Döring 2014; Budzinski and Gaenssle 2020). Notwithstanding the still existing type of non-professional content, this trend of professionalization points towards the significant turnovers and revenues that content providers such as so-called social media starsFootnote 4 earn through participation on YouTube’s advertisement revenues as well as through product placements—with the latter further emphasizing the commercial nature of the content supply (Budzinski and Gaenssle 2020; Gaenssle and Budzinski 2021). Nowadays, a significant share, if not most of the views on YouTube, fall on commercial content, most of which is professionally produced; the most popular 20% receive 97% of views (Ding et al. 2011) and 10–30% of videos have fewer than ten views (Chowdhury & Makaroff 2013).

A related aspect refers to content differences in terms of the extent of exclusive and/or original content. While this used to be a domain of traditional television, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video for instance, as well as new players, such as Disney + and Apple TV + , aim at attracting their audience especially with original (own produced) or exclusive content (e.g., Netflix with House of Cards or Orange is the New Black) (inter alia, Aguiar and Waldfogel 2018; Benes 2019).

Content differences corresponding to different purposes of usage

Content differences between the different types of services that relate to different consumption purposes represent a second aspect. While YouTube is known to predominantly provide shorter videos (e.g., short clips, music videos & social media star entertainment), both Netflix and TV focus on longer pieces, such as movies, series, and shows. These content differences may go along with different ways of consumption. For quick information (specific tutorials/help, etc.) or social network elements (i.e., follow stars or friends, sharing content), YouTube meets the consumers’ preferences, whereas for full-length video content the choice falls on the other types of services. Therefore, YouTube may be more relevant for purposes, such as bypassing waiting or travelling times, covering smaller breaks and shorter entertainment spaces, etc., whereas PVoDs, such as Netflix and TV, are preferred for filling an evening of entertainment or a free Sunday afternoon, for instance. As such, the two service types would rather complement each other than compete with each other. These differences in contents and consumption could reflect in service usages different times of day: Netflix and TV should be the prime-time competitors according to this view, whereas YouTube is more a media for “in-between” moments throughout the rest of the day. However, with the professionalization of AVoD content, average video length is developing towards traditional video formats. A study conducted by the search engine Pex (Turek 2019) shows that average YouTube videos are 11.7 min long (December 2018), with popular categories reaching up to 25 min on average (gaming 24.7 min; film & animation 19.2 min). Moreover, serial consumption of videos and so-called binge watching (Rubenking et al. 2018; Gaenssle & Kunz-Kaltenhäuser 2020) allows consumers to watch hours of video content without interruption—a phenomenon that is further fueled by individualized recommendation systems and auto-play modes (for instance, for music videos).Footnote 5 Independent of the single video length, this may result in hours of successive consumption; accumulating to a total consumption length, which is easily comparable to full-length movies. These developments show converging trends and increasing comparability of services.

Linearity, devices, and social network elements

VoD, in general, differs from TV in that there is no fixed program schedule as a take-it-or-leave offer for consumers. Instead, VoD consumers can watch all available contents whenever they want and compile their “program” by themselves. The media literature calls the schedule-bound service linear and the on-demand type non-linear (inter alia, Berman et al. 2009; Kazakova & Cauberghe 2013; Steemers 2014; van den Bulck & Enli 2014; Simons 2015; Enli & Syvertsen 2016). A further difference may relate to the device of usage. One expects consumers of traditional television programs or Netflix (PVoD) to prefer large television screens, while YouTube-style AVoD services are mostly watched on mobile devices (laptops, tablets and, particularly, smartphones). However, due to the possibility of downloading content to mobile devices and watching it ‘on the road’, consumers may start to watch their favorite shows—regardless of the original service (AVoD, PVoD or TV)—while, e.g., traveling to work. Eventually, social networking elements, such as commenting, sharing or liking content, may represent a differentiator. This social media function is usually not possible for linear TV, although broadcasters recently started to increase audience engagement, e.g., in live shows with audience questions or the possibility of writing (WhatsApp) messages. Nevertheless, due to the nature of the non-linear availability of content, audience ratings, comments, and shares are possible on AVoD and PVoD. Especially AVoD services such as YouTube or Twitch entail networking elements and active ‘below video commenting behavior’. However, former non-digital players in the market also adapt to new possibilities and try to increase audience engagement.

The economics of attention

Overall, the different services seem to converge and try to use all possible ways to increase the time recipients spent consuming their content. Attention may be a scarce resource and, in the face of information overflow due to omnipresent mobile access to the internet, a relevant one for online content consumption (Falkinger 2008; Anderson and da Palma 2012; Evans 2013; Boik et al. 2017; Gaenssle 2021). According to the economics of attention, all content providers compete for the scarce attention of the users who can spend every minute of their attention only once. Therefore, if a user opts for watching YouTube videos, she cannot spend this attention to a Netflix serial anymore and vice versa (opportunity costs). Given that many users spend a relevant time of any day for working, sleeping, and other activities (childcare, sports, etc.), competition for the remaining time for watching audiovisual online content may be intense. Furthermore, even though there are differences in detail, a large part of content and consumption regarding all three types of services is about entertainment and, thus, referring to the same underlying intention or want of the consumer.

From this theoretical perspective, the case for TV and Netflix-style services being in competition with each other appears to be straightforward. In a way, services such as Netflix may be viewed to take the place of TV, entailing the advantages of traditional TV and adding the luxury to be non-linear, so that users do not depend on a given program schedule anymore, but can cherry pick their times and contents (Tefertiller 2018; Budzinski and Lindstädt-Dreusicke 2020; Fudurić et al. 2020). Therefore, it may mainly be a generation effect separating the two types of services with older generations just being slower to adapt to a superior new good (Lindstädt-Dreusicke and Budzinski 2020).

However, while enhanced choice options will mostly benefit consumers’ preferences, there can be exceptions to that. Choosing does require investing cognitive capacity and in some situations in life—like the end of an exhausting day, where someone just looks for some relaxing entertainment before going to sleep or background entertainment without active engagement (like radio consumption is often done)—users may not want to spend cognitive resources on low-involvement routine consumption (Vanberg 2002; Budzinski 2003). Then, a linear service such as TV may be superior, since it demands less cognitive engagement and decision effort.Footnote 6 Moreover, regular television consumers might enjoy the feeling of being connected to society, watching what other people nationwide are also watching, i.e., networking and commonality effects as well as cultural inclusion by, e.g., national popular TV shows. Finally, the bundling of information and entertainment, e.g., news and prime-time movie as a bundle, may be valued by consumers, and be very tiresome to self-compile (or even impossible due to lack of supply) on PVoD and AVoD.

Notwithstanding, the newer services entail a tool that may serve a similar purpose. The algorithm-based recommendation service of Netflix, YouTube and co. may substitute for the linear program schedule in cases of routine and low-involvement consumption. Based on individual data, recommender systems provide content suggestions for (indecisive) consumers. To simplify the demand-process and lower the cost of active consumption decisions, services use auto-play modes (immediately starting the next video), content suggestions, trailers, etc. (see for a detailed analysis Budzinski et al. 2021).

Altogether, the theoretical reasoning does not yield a clear picture and, therefore, emphasizes the relevance of an empirical analysis. This empirical analysis must consider that the intensity of competition may vary with factors, such as age, intention, genre, or time of day.

Empirical analysis: methodology and data

Sampling and data

The data used for the empirical analysis originates from an online survey conducted from November 2018 until February 2019 in Germany (by Ilmenau University of Technology and the Business School at Pforzheim University). It is an academically motivated study, independent of external funding or other heteronomous interests. The standardized quantitative online questionnaire was specifically designed to match the research questions mentioned above. We attracted 3882 registered visits, of whom 3277 started the questionnaire, to eventually reach N = 2920 valid finishers. The students, who were responsible for the sampling, executed the recruitment and invitations to the questionnaire, i.e., spreading it mainly among their peers (young people and older relatives). The survey participation was predominantly voluntarily, although driven by social obligations towards the students conducting it. At Pforzheim University ‘StudiQUEST’ a panel of students and alumni was involved. Moreover, the invitation to the questionnaire was placed at the landing page of ‘serienjunkies.de’ for a week in January 2019. All parts of Germany are represented within the sample; however, the states of origin are over-represented (with 650 from Ilmenau and surrounding, and 661 from Pforzheim and surrounding). The average age of respondents is 31.55 years (min: 10; max: 83); with 48.15% male, 50.65% female, 1.2% ‘other’. Since the survey was conducted in a university environment, the sample is biased towards a young, highly educated, low-income group; 56.4% have an income lower than EUR 1,500.Footnote 7 The educational level is displayed in Table 1 and shows that 29.62% have a university entrance qualification and 42.5% a university degree.

The representativeness of the sample cannot be guaranteed for all relevant aspects of the analysis and cannot be compared to well-structured cluster sampling. Notwithstanding, given the sample size, we find both variance and randomness to meet statistical requirements. It provides information on stated and pseudo-revealed preferences of the participants and if/how, they diverge. Moreover, the over-sampling within young age groups can be used in favor of the analysis, as especially young adults use VoD offers.Footnote 8 For the analysis of competition between online services more information on consumers, who know and actually use all services, is very valuable. These trends will intensify over time with growing numbers of young generations and changing consumption habits.

Data analysis and variables

The questionnaire comprises of 13 content-related separate questions (excluding demographic questions, such as age, gender, etc.). We use direct questions to show stated preferences in descriptive statistics (see 4.1). Two questions in the survey feature item batteries (six items each) of attitude measurement with five-point Likert scales (1 = disagree to 5 = agree; 6 = no response). In accordance with findings of Revilla et al. (2014), who found that five-point scales are statistically equivalent (in terms of validity and efficiency) to seven-point or larger scales, we find five-points scales intuitive for respondents and analysis.

One questions asks for the frequency of media usage and another one for the duration of usage. To answer our research questions, the consumption of video content via the different services is crucial. Which service is used at what time and how much content is consumed? The frequency (i.e., how often consumers use the service) and the duration (i.e., how much time they spend consuming video content) are relevant to analyze the extent of usage and importance of the respective service. Therefore, we are interested in the consumption intensity depending on the respective type of media service i = {AVoD; PVoD; TV} and construct a pseudo-metric dependent variable for the analytical analysis:

If services compete for the consumer’s attention, it is a question of time allocation. The intensity of usage represents the time spend on consumption, as pictured in Fig. 1, the consumer can either spent more time within one sitting (B) or shorter sittings with higher frequency (A). The exposure to content and time allocated to consumption is the same in both cases.

The frequency of usage is measured on a seven-point scale from high to low frequency (6 = several times daily; 0 = never) for each service, supplemented by the option ‘no response’. The duration of video consumption in one sitting, i.e., how long without taking a break or switching activity, was also measured for each service separately. By moving a regulator on a scale from ‘0’ to ‘ > 3 h’ (in seven steps), the respondents could state the length of one average sitting. The multiplication of the variables gives us a range of 25 points (0 = never, 24 = several times daily, more than three hours). The intensity of the usage can thus be expressed by the new dependent variable on a range from non-users (never), over medium-users (e.g., monthly, on average one hour) to heavy-users (several times daily, more than three hours).

Four independent variables are used for the analysis: (1) intention of usage [entertainment, shorten waiting time, stimulate knowledge, and personal motivation (i.e., career/health)]; (2) genre (feature film, documentary, series, tutorial, sports, news, comedy, and music videos); (3) time of day (of service i; noon, afternoon, and eveningFootnote 9); and (4) information on individuals j (age category, gender, and education).

Since we are not only interested in the factors explaining the intensity of consumption, but the interaction between the different services, i.e., competitive relations between YouTube, Netflix and TV, we decide to perform a seemingly unrelated regression estimation (SURE) (Zellner 1962, 1963; Zellner and Huang 1962). This method is commonly used for supply and demand models. Our model consists of three regression estimations, each with its own dependent variable (for the respective services i). While every equation can be seen as an independent linear regression and can be estimated separately, error terms are expected to be correlated across equations. As such, it is a system of linear equations with error terms that are correlated across equations for a given individual but not across individuals. When the models do not have the same set of independent variables and error terms are correlated, SURE can lead to more efficient results than separate OLS (ordinary least square) estimations. Moreover, it is suitable to perform joint tests.

The model consists of i = {AVoD; PVoD; TV} linear regression equations for \(j=1,\ldots, N\) individuals. The ith equation for individual j is

Stacking all observations, the model for the ith equation is

Here, the error terms u are allowed to be correlated to estimate a full variance–covariance matrix of coefficients.

Empirical analysis: results and discussion

Descriptive statistics and results

For whom (RQ-i)?

To understand the motives of consumers and their personal perception, we directly ask them on their agreement on a five-point Likert scale. Among the questions of (dis-)agreement, we asked if respondents agreed that (a) YouTube (AVoD) is an alternative to Netflix (PVoD), (b) Netflix (PVoD) is an alternative to TV, and (c) YouTube (AVoD) is an alternative to Netflix (PVoD). In doing so, consumers are directly asked for their opinion and state their preferences for video consumption. Moreover, a detailed presentation of answers within the different age groups reveals interesting results on the sub-question (i) of our research question “for whom”.

-

a)

The answers to the question whether YouTube-style AVoD is an alternative for TV are rather dichotomous. In total 38.59% tend to disagree, 12.71% are neutral, and 48.05% tend to agree (0.65% ‘no response’). Looking at the age groups the difference is apparent with 38.89% of people older than 60 years strongly disagreeing and 49.04% younger than 19 years strongly agreeing (Fig. 2). The results show deep differences between far end age groups and their consumption behavior.

-

b)

When it comes to Netflix-style PVoD vs. TV, the answers are much more homogenous, since most consumers in our sample tend to perceive them as close alternatives and strongly agree (Fig. 3). Again, only those older than 60 years express a strong opinion against PVoD being an alternative to TV.

-

c)

Lastly, the relationship between YouTube-style AVoD and Netflix-style PVoD is shown in Fig. 4. There is no considerable difference between age groups and the results are comparatively heterogeneous. In total more respondents seem to disagree with AVoD and PVoD serving a similar purpose; 58% disagreement, 15.55% neutral, 22.91% agreement (7.74% of which strongly), and 3.46% ‘no response’. Thus, in our sample, considerably fewer people think of YouTube as an alternative to watching Netflix (about 23%) than to watching TV (about 48%). Still, it is quite surprising that almost 23% of respondents within the sample agree to AVoD and PVoD being alternatives for one another.

In addition to the Figs. 2, 3, 4, we performed mean comparison tests to check significant differences between the statements. The strongest agreement (mean 4.40) is PVoD-TV, i.e., according to the participants perception, PVoD is the best alternative to TV. Moreover, on a five-point scale 4.40 means that most people agree to this statement. This is followed by AVoD-TV alternative with a mean at 3.22—still more than neutral. Whereas, AVoD-PVoD, with a mean of 2.48, is overall rated as least good alternatives. The T tests (mean comparison) show that all means are significantly different from one another. It seems that the relatively young sample tends to substitute AVoD and PVoD for TV. Rather than PVoD for AVoD.

For which purposes (RQ-ii)?

The second sub-question (ii) “for which purposes” can be analyzed by looking at the genres which are consumed. It can be expected that competition is higher for genres which are intensely used on all services. Figure 5 shows the total number of answers per service and genre, i.e., participants stated if they use the respective service to watch for example feature films. 2242 participants stated that they watch feature films on PVoD, only 216 on AVoD and 1562 on TV. Series are strongly preferred on PVoD. Expectedly, tutorials and music are mostly watched on AVoD, such as YouTube. Overall, feature films are most popular (in total 4020) followed by series (in total 3895). Not as popular, but watched on all three services, are documentaries. A more in-depth analysis, using regression estimations, shows further insights on consumer intentions and genre (see Sect. 4.2).

During what time of the day (RQ-iii)

Most consumers spend their evening time to consume video content, apparently actively choosing between the respective services. Figure 5 displays daytimes and total number of respondents using the service at that time (multiple answers possible). Note that n = 2,920. In other words, more than 70% of the respondents in our sample indicate that they use all three services (YouTube, Netflix, TV) for evening video consumption. Therefore, while consumers consider the services to be different, they still choose between them as alternatives to consume audiovisual contents in the evening. Consequently, AVoD, PVoD and TV seem to compete for the consumers’ attention during peak times of consumption and standard leisure time (prime-time entertainment), whereas things look different at other times of day (Fig. 6).

Summing up, the descriptive results show that there is no strict line between the different services, although most consumers agree to PVoD being an alternative for TV. Among younger generations AVoD seems to be a better alternative to TV than for older generations. The results for PVoD and AVoD are mixed. Consumers state to use the services for different reasons, yet, when it comes to the time they spend on consumption, the services seem to be in close competition for the consumers attention during prime time in the evening (but not at other times during the day). Altogether, the descriptive results are not fully conclusive. A detailed analysis with more sophisticated methods is necessary to verify the results.

Econometric analysis and results

By the means of seemingly unrelated regression estimations (SURE model), we analyze the influence of different intentions, genres, times of day, and individual characteristics (age, education, gender) on consumption intensity of (1) AVoD, (2) PVoD, and (3) TV. Table 2 displays the results for one model, the three different dependent variables (1–3) in the columns next to each other.Footnote 10 Due to filter questions, only N = 2333 observations are taken into account. R-squared shows the proportion of variance explained by the independent variables. It is highest for model 1, which shows that the explanatory power is best for AVoD.

Results intention: We asked for the different intentions that consumers have for watching video content. While getting entertained is one of the main intentions, the results are not significant in our model, approximately due to lack of variance in the answers. However, other results show significant coefficients. At the first glance surprisingly, ‘shorten waiting time’ is significantly positive for Netflix-style PVoD, while it is not for YouTube-style AVoD. This appears to be counterintuitive, because based on the theoretical reasoning (see Sect. 2), one would expect a lot of mobile and ‘on the road’ usage of YouTube-style services. Yet, an explanation could be that many users download videos from Netflix or Amazon and watch them while traveling on the bus/train etc. Mobile internet connection in Germany is often limited (Briglauer et al. 2019), so traveling to work or long distances might lead through “dead spots” without sufficient signal strength. Regarding ‘stimulating knowledge’, research and learning are closely connected to YouTube usage, which can explain the positive results for ‘stimulating knowledge’ on AVoD. In that regard, PVoD and TV do not seem to compete with YouTube & Co, as the results for those services are significantly negative. The same is true for ‘motivation’ and TV. Consumers who seek motivation (e.g., health or career) use YouTube-like services, whereas the coefficient for TV is negative regarding this aspect.

Results genre: ‘feature films’ are significantly positive for the intensity of usage of both Netflix and TV. Therefore, it can be expected that the services compete for consumer attention when they are choosing full-length feature films. However, the preferences for ‘series’ on Netflix-style PVoD are obvious. ‘Sports’ are significantly negative on AVoD, whereas significantly positive on TV, which could be due to lack of supply on YouTube & Co rather than lack of demand. This is similar to ‘news’ and the opposite direction to ‘music videos’. ‘Comedy’ is positive for YouTube-style AVoD consumption intensity. While comedy can also be found in traditional television and on PVoD, participants in our study seem to prefer AVoD channels.

Time of day: Interestingly, and in accordance with descriptive results, there seems to be intensive competition for prime-time consumption. When asking the participants about the time of consumption during the day, multiple answers for the different services were possible. There are no significant results for the time around noon. On one hand, the preference to watch PVoD in the afternoon increases the probability of AVoD consumption intensity. On the other hand, in the evening the PVoD consumption has negative impact on AVoD consumption. The other way around, AVoD evening preferences negatively influence PVoD consumption. Moreover, prime-time television choices negatively affect both AVoD and PVoD. These analytical results confirm the descriptive results and show that services compete for the consumers’ attention—despite differing contents. If consumers simply want to get entertained, they seem to choose among all of the three services in their free time (primarily prime time in the evening).

Results age categories: the base group for age is 10–19 years. The negative coefficients show that all older age groups use relatively less YouTube-style AVoD, which thus is the “youngest” service among the three. There are no statistically significant results for Netflix-style PVoD, except for the group older than 60 years, who generally do not prefer to watch VoD services. TV shows opposing effects, since expectably older age groups tend to watch more television than younger ones. Thus, our results match other, more representative studies (summarized in Sect. 1) with respect to generation effects, increasing confidence in the results of our study which is not that representative but digs deeper into the topic.

In summary, the results of the empirical analysis show that (1) services compete for prime-time attention of consumers, supporting the descriptive findings (see 4.1); (2) show that ‘intention’ and preferred ‘genre’ mostly vary between services, yet, consumers like to get entertained by all of them,Footnote 11 and (3) concerning age groups, younger people actively choose AVoD channels, supporting the results of more representative studies. In the light of the ongoing dynamic development of online VoD service-offerings, competition between services seems likely to increase in the course of time.

Summary and limitations

Theoretical reasoning suggests that types of services that are more similar to each other should stand in closer competition than more dissimilar services (see Sect. 2). Closely connected research on PVoD streaming vs. TV shows substitutive characteristics between the two services (McKenzie et al. 2019; Fudurić et al. 2020). Given the state of the German market at the time of the survey, this implies that contentwise TV and PVoD à la Netflix are close competitors. While YouTube as the main AVoD outlet should be less of an alternative to TV, the AVoD–PVoD interrelation may be expected somewhere in-between as they share the non-linear character despite of content differences. In line with previously published studies (see above), our respondents state their views, when asked directly, in roughly that manner (see Sect. 4.1.1). Since previous studies did not include all three types (AVoD, PVoD, TV) but usually analyzed ‘only’ two of them, our analysis adds the important insight that the result ‘Netflix-style VoD is a closer competitor to TV than YouTube-style AVoD’ rests on middle-age generations, whereas for the younger generation YouTube is a substitute for TV. However, the design of our study allows to look beyond the pure statements, which yields more differentiated results.

Some results of the econometric analysis in fact support the notion of limited competition between YouTube and TV, e.g., the intention to stimulate knowledge, or finding personal motivation in video content. In both cases respondents favor AVoD and not TV. Confirming insights of studies by Chen (2019) and Fuduric et al. (2020), genres such as sports and news favor TV. There is also a strong preference for Netflix-style PVoD when it comes to serial content (in line with McKenzie et al. 2019), thus, competitive relations seem rather weak in this case in our sample. Therefore, we cannot confirm results from Shelton et al. (2016) and Prince & Greenstein (2017) in the U.S. market, showing little influence of content categories.

The analytical analysis further shows that the intensity of competition between the three types of services is not so clear at daytime. Here, consumers appear to use them not so much as alternatives. This is further supported by the results for the intention to bypass “waiting time”, where our respondents clearly prefer one type of service—and not the one that theory would suggest: instead of YouTube they prefer Netflix here. Different times of day and intentions are, to the best of our knowledge, not analyzed in previous studies. Not surprisingly, older generations strongly stick to traditional television, which merely points to a time-lag in the competition of newer technology-based services and is in line with previous studies (Prince and Greenstein 2017).

However, our empirical analysis shows that roughly 48% of the respondents view YouTube to be an alternative for TV (ranging from almost 20% among the over 60 years to almost 70% from the below 20 years; see Sect. 4.1)—despite the strong differences in content. Notably, a strong minority of approx. 39% disagrees (ranging from more than 65% in the oldest to less than 20% in the youngest age group). Since our sample is biased towards younger and well-educated respondents, it can be expected that the disagreement figure may be higher in a more representative sample—for now, as in the course of time, the development will trend towards our results (emphasizing the now younger generations). Notwithstanding, the results make it hard to argue that YouTube is not exerting competitive pressure on traditional TV—and as such goes beyond much of the existing literature (see Sects. 1 and 2). Our results expectably indicate to Netflix-type VoD services and TV being close competitors, whereas the picture for YouTube vs. Netflix is not so clear with 58% stating the view that they do not represent alternatives and almost 23% stating they do (without significant difference among the age groups; see Sect. 4.1). However, at the same time, asked what medium they consume at prime-time, for each type of service 70.6% or more of the respondents confirmed consumption.Footnote 12 The consequent indication that all three services compete for prime-time attention is confirmed by analytical econometrics (see Sect. 4.2). Thus, actual behavior (pseudo-revealed preferences through indirect questions) appears to show closer competition among the service types than (more directly) stated preferences. Both results—strong competition for prime-time attention and notable differences between stated and revealed preferences—are unique to our study and are not analyzed in previous studies.

Altogether, competitive pressure among Netflix, traditional TV and YouTube cannot be ignored when considering the development of markets for audiovisual contents—be it for competition policy or other purposes. Particularly, excluding YouTube from (analyses of) TV and/or VoD markets appears to inappropriate in this respect as it exerts considerable competition on the other two (types of) services. Especially for younger generations the competition for attention appears to be already strong today and will, furthermore, intensify in the course of time.

However, there are some limitations and caveats we need to consider. Some contents are not present on some type of services, for instance, hardly any contemporary music videos are nowadays broadcasted on TV and Netflix-style PVoD in Germany.Footnote 13 The same is true for news on Netflix and co. This raises the questions: (i) does available content drive the answer in our survey or (ii) does the consumption behavior/preferences we measure explain why there is virtually no content offering? Unfortunately, we cannot discriminate between these two possible explanations with our data. Still, this limitation is only relevant for some genre categories. Furthermore, anecdotic evidence for contemporary music videos shows that there was a considerable offer on TV (MTV, VIVA, etc.) until YouTube came up and only then the offer in TV started to vanish. This indicates that the non-offer may be a result of competition and, thus, towards explanation (ii). If this was valid, our results tend to underestimate the competitive pressure among the service types.

With respect to news-style content, the results may reflect a dependence on the (perceived) quality of this type of content, about which information are not available in our data set. Alternatively, the large-scale public service broadcaster landscape in Germany may already provide the overall market volume for audiovisual news contents, thus leaving no space for competition from newly emerging VoD-services, in particular given the fact that public service broadcasters (PSB) in Germany can subsidize their news coverage by revenues from a tax-like fee. Here, the demographic bias towards high educated respondents in our sample may influence the results, since highly educated people are said to be more likely to value high-level (PSB-) news contents.

Our results relate to the market offerings as they were in Germany at the time of the survey. For instance, the PVoD-style YouTube Premium was not relevant in Germany at the time of the survey (and still does not rack up considerable market shares at the time of writing) but may change competitive interrelations in the market in the future—as may other further dynamics. In particular, the entry of an advertising-financed Netflix-like service (contents such as Netflix and revenue structure such as free commercial TV) would represent a very different AVoD from YouTube and, thus, might lead to different results. In general, the high market dynamics are likely to continue and may bring about a convergence of services with some players attempting to provide a one-stop shop for audiovisual consumption (e.g., Alphabet adding YouTube stories à la Instagram, video rental à la Amazon and premium subscription à la Netflix to its core AVoD business). These dynamics may further change competitive interrelations as well. Based on our analysis, we predict that further dynamics further increase the intensity of competition among services.

Finally, our results can only be seen as ‘indication’, since the sample is not representative in size, nature and scope. We have no data on ‘real’ consumption behavior, but personal statements about and estimations of consumption habits. It would be interesting to compare these results with data from YouTube or Netflix to see if actual consumption behavior and self-reporting match. However, since data is of major importance in that market and represents a relevant business secret, a publication by the companies cannot be expected. Future and complementary research might still find ways to track actual consumer behavior and analyze the (changing) dynamics in the field. Naturally, since it is the first empirical study on competition in VoD markets, follow-up research and re-sampling are necessary to verify results.

Conclusion and implications

Based upon our theoretical reasoning and our empirical analysis, we are able to provide answers for and insights into our research questions. With respect to our general research question whether relevant competitive pressure between the services (in our study represented by YouTube, Netflix, TV) exists, our analysis demonstrates that all three (types of) services stand in competition with each other. Moreover, our rich data set allows us to look deeper into the matter and specify the general research question by, more precisely, inquiring whether the intensity of competitive pressure depends on specific characteristics of demand, i.e., (i) for whom (e.g., age groups); (ii) during what time of the day (e.g., prime-time); and (iii) for what purposes (e.g., genre, motivation/intention).

Regarding age groups, the battle between YouTube, Netflix and traditional TV mainly takes place regarding the younger generations for whom these services represent close alternatives, whereas older generations remain more focused on TV. This also hints at further increasing competitive pressure among the services in the course of time. While these results confirm less detailed but samplewise more representative studies, our result regarding different times of day represent novel insights. Our analysis shows that all three services strongly compete for prime-time consumption, i.e., the vast majority of consumers actively chooses between all three types when it comes to watch video content in the evening. However, our results for other times of day are mixed and insignificant. With respect to consumer intentions, the respondents in our sample prefer Netflix over the other two when it comes to “shortening waiting time”, which represents a counterintuitive result to the expectation that YouTube would dominate this intention category.

Our analysis yields important implications for the effects of cooperations, alliances, mergers and acquisitions in audiovisual content markets. It is not sufficient to point to differences in content or an alleged (and, however, defined) professionalism of content producers to assume a lack of competitive pressure. In addition, features and characteristics of consumption behavior and competition from traditional TV markets cannot readily be applied to more—offline and online—audiovisual content markets. Eventually, a general “they all compete because they all provide audiovisual content” would also be too superficial. Instead, our analysis demonstrates that audiovisual content providers act in a heterogeneous market, where some suppliers may be closer competitors to each than to others (thus, markets, where unilateral oligopoly effects matter; Kaplow and Shapiro 2007; Froeb and Werden 2008; Kerber and Schwalbe 2008; Keating & Willig 2015). Furthermore, consumption behavior is so differentiated that these interrelations may differ across, inter alia, daytimes, consumer intentions, and genres. Thus, a careful analysis of the actual competitive effects is necessary when assessing joint venture projects or mergers and acquisitions among these players, including vertical effects (which are not part of our analysis; but see, e.g., Stöhr et al. 2020). Moreover, unilateral business strategies need to be observed and considered as well, in particular, if these strategies aim at or result in a walled garden type of offering, i.e., proceed in the direction of a closed ecosystem protected against outside (maverick) competition. This is necessary to sustain dynamic competition among audiovisual content providers and maintain a diverse, pluralistic, and preference-conformal landscape.

Moreover, our analysis yields strategy implications for companies in the audiovisual sector. The separation of the three types of audiovisual media is likely to further disappear in the future when the now youngest generations—who already view all three as close competitors—incrementally replace the older generations who stick more to traditional viewing habits. Thus, ignoring YouTube consumption as being too different may be riskier in the long run than embracing the YouTube kids as consumers. This also entails the underlying business models: relying on subscription-based services (PVoD) looks likely to be inferior strategywise to mix payment models and allow for both AVoD- and PVoD-style consumption. This requires moving away from a silo mentality and to interconnect the different channels to transmit audiovisual contents into an integrated offering.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

YouTube started its paid-for service only in mid-2018, just before our data was collected, but it was hardly known or used at the time (YouTube Official Blog 2018). Moreover, until today, YouTube is predominantly known for its AVoD service. In addition to this, it had been announced in September 2019 that a lot of own productions that had been set behind the Premium Paywall will be moved to the advertising-financed section of YouTube, leading to speculations about the success and performance of the paid-for service offer (Meedia 2019). Joyn, a VoD service by ProSiebenSat.1. and Discovery started in June 2019 with an AVoD model only and just switched to a hybrid model of both advertising and user financing at the end of 2019, both after our data had been collected. TV Now, a hybrid service by the RTL Group had been existent before, however, had little meaning in the German VoD market compared to the market leaders Netflix and Amazon Prime Video and just in 2019 announced massive investments in its video streaming activities for the next 3 years (Krei 2019, WV 2019).

Please note, since these answers are not revealed preferences of actual consumption behavior, but descriptions on their behavior by the respondents, we consider them as pseudo-revealed. For a discussion of stated and revealed preferences in online media from an economic perspective, see Budzinski and Kuchinke (2020).

Social media stars (so-called: influencers, creators, micro-celebrities, online stars, etc.) are successful content providers on social media platforms like YouTube or Instagram (for a detailed analysis see Gaenssle and Budzinski 2021).

The platform Twitch (twitch.tv), for instance, allows content providers 24 h streaming.

Netflix seems also aware of such challenges with indecisive consumers and started a test for a linear channel called “Netflix Direct” in France in November and December 2020 for existing Netflix subscribers (Etherington 2020; Pauker 2021). According to the COO and Chief Product Officer of Netflix this linear channel should start internationally, though the exact countries are not yet announced (Pauker 2021). See also Spilker et al. (2020) on linear broadcasting on Twitch.

See Appendix 1 and 2 for detailed information on income and age groups.

Multiple answers were possible. We excluded “morning” and “night” due to multi-collinearity. Moreover, these periods do not add more information on competitive relations from a theoretical point of view (see Fig. 5 for an overview between daytimes).

We performed regression specification tests on separate OLS regressions (each dependent variable separately) to check the applicability. Especially multi-collinearity was of concern, but the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the independent variables show values below five for each linear regression. Moreover, we checked if all equations together are statistically significant. The Breusch–Pagan test of independence shows that, for the same individuals, the correlation of the residuals is significant and we can reject the hypothesis that this correlation is zero.

2,893 out of 2,920 participants choose at least one of the services to get entertained.

We included a question on second screen usage (i.e. parallel use of two screens) in our questionnaire. Although, younger consumers tend to engage in second screen usage like e.g. Instagram on the smartphone and Netflix on television at the same time, we consider the parallel usage of two videos to be a rare exception (mostly, due to overlapping audio tracks). Yet, future research is needed to investigate the phenomenon and better estimate the possibility of parallel usage.

For instance, MTV still broadcasts but its program does not primarily contend of music videos anymore. A channel like Deluxe Music does still broadcast music videos (mostly for older generations) but is of little relevance.

References

Aguiar L, Waldfogel J (2018) Netflix: global hegemon or facilitator of frictionless digital trade? J Cult Econ 42(3):419–445

Anderson SP, de Palma A (2012) Competition for attention in the information (overload) age. Rand J Econ 43(1):1–25

Audience Project (2019) Insights 2019, Traditional TV, online video & streaming, a study by the Audience Project, ed. by Rune Werliin, 1–55. https://www.audienceproject.com/wp-content/uploads/audienceproject_study_tv_video_streaming.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2020

Benes R (2019) Users still demand licensed content from OTT platforms, on eMarketer, 10.05.2019, https://www.emarketer.com/content/users-still-demand-licensed-content-from-ott-platforms (accessed 03 March 2020).

Berman SJ, Battino B, Shipnuck L, Neus A (2009) The end of advertising as we know it. In: Gerbarg D (ed) Television goes digital. Springer, New York, pp 29–56

Boik A, Greenstein SM, Prince J (2017) The empirical economics of online attention. Kelley School of Business Research Paper No. 22427.

Briglauer W, Dürr N, Falck O, Hüschelrath K (2019) Does state aid for broadband deployment in rural areas close the digital and economic divide? Inf Econ Policy 46(3):68–85

Bruns A (2008) Blogs, wikipedia, second life, and beyond: from production to produsage. Peter Lang, New York

Budzinski O (2003) Cognitive rules, institutions, and competition. Const Polit Econ 14(3):215–235

Budzinski O, Gaenssle S (2020) The economics of social media (super-)stars: an empirical investigation of stardom and success on YouTube. J Media Econ 31(3–4):75–95

Budzinski O, Kuchinke B (2020) Industrial organization of media markets and competition policy. In: von Rimscha B (ed) Economics and management of communication. DeGruyter, Berlin, pp 21–45

Budzinski O, Lindstädt-Dreusicke N (2020) Antitrust policy in video-on-demand markets: the case of Germany. J Antitrust Enforc 8(3):606–626

Budzinski O, Wacker K (2007) The prohibition of the proposed springer-ProSiebenSat.1-merger: how much economics in German merger control? J Compet Law Econ 3(2):281–306

Budzinski O, Gaenssle S, Lindstädt-Dreusicke N (2021) Data (R)evolution—the economics of algorithmic search & recommender services. In: Sabine B (ed) Handbook of digital business ecosystems. Elgar, Cheltenham

Bundeskartellamt (2011b) Bundeskartellamt Institutes Cartel Proceedings to Examine Video-on-demand Platform of Public Service Broadcasters, press release 2011–11–28, http://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Meldung/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2011/28_11_2011_Germanys-Gold.html;jsessionid=6D9A2CC003444E5ECBEDEAC771F19CE8.1_cid371?nn=3591568 (accessed 28 Oct 2019).

Bundeskartellamt (2011a) Beschluss in dem Verwaltungsverfahren ProSiebenSat.1 Media AG / RTL interactive GmbH, Aktenzeichen B6–94/10, http://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Entscheidung/DE/Entscheidungen/Fusionskontrolle/2011/B6-94-10.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 (accessed 28 Oct 2019).

Bundeskartellamt (2015) Case summary: ARD and ZDF online platform “Germany’s Gold”, B6–81/11–2, https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Entscheidung/EN/Fallberichte/Kartellverbot/2015/B6-81-11.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed 26 Dec 2019).

Chen Y-NK (2019) Competitions between OTT TV platforms and traditional television in Taiwan: a Niche analysis. Telecommunications Policy 43(9):1–10

Chowdhury SA, Makaroff D (2013) Popularity growth patterns of YouTube videos: a category-based study. In: Krempels KH, Stocker A (eds) Proceedings of WEBIST 2013: 8th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies, 233–242.

Dennhardt S (2014) User-generated content and its impact on branding, how user and communities create and manage brands in social media. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Ding Y, Du Y, Hu Y, Liu Z, Wang L, Ross K, Ghose A (2011) Broadcast Yourself: understanding youtube uploaders. In: Patrick T, Walter WW (eds) IMC 2011, Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM on Internet Measurement Conference, New York: ACM, pp 361–370

Döring N (2014) Professionalisierung und Kommerzialisierung auf YouTube. Merz Medien + Erziehung 58(4):24–31

Enli G, Syvertsen T (2016) The end of television—again! How TV is still influenced by cultural factors in the age of digital intermediaries. Media Commun 4(3):142–153

Etherington D (2020) Netflix tests a programmed linear TV and movie channel in France, Techcrunch, 06.11.2020, https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/06/netflix-tests-a-programmed-linear-tv-and-movie-channel-in-france/ (accessed 18 June 2021).

Evans DS (2013) Attention rivalry among online platforms. J Compet Law Econ 9(2):313–357

Falkinger J (2008) Limited attention as a scarce resource in information-rich economies. Econ J 118:1596–1620

Fisher B (2019) UK digital video 2019, A rich provider landscape drives up digital viewership, on eMarketer, 19.09.2019, https://www.emarketer.com/content/uk-digital-video-2019 (accessed 13 Feb 2020).

Froeb LM, Werden GJ (2008) Unilateral competitive effects of horizontal mergers. In: Buccirossi P (ed) Handbook of antitrust economics. The MIT Press, Boston, pp 43–104

Fuchs C (2014) Digital prosumption labour on social media in the context of the capitalist regime of time. Time Soc 23(1):97–123

Fudurić M, Malthouse EC, Lee MH (2020) Understanding the drivers of cable TV cord shaving with big data. J Media Bus Stud 17(2):172–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1701363

Gaenssle S, Kunz-Kaltenhäuser P (2020) What drives binge-watching? An economic theory and analysis of impact factors. Ilmenau Economics Discussion Papers 26 (138).

Gaenssle S, Budzinski O (2021) Stars in social media: new light through old windows? J Media Bus Stud 18(2):79–105

Gaenssle S (2021) Attention economics of instagram stars: #Instafame and sex sells? Ilmenau Discussion Papers, Vol. 27(150)

Herrmann S (2019) Goldmedia studie. Pay-VoD-Markt in Deutschland klar verteilt. W&V Online, 30.10.2019, https://www.wuv.de/medien/pay_vod_markt_in_deutschland_klar_verteilt (accessed 14 Feb 2020).

Kaplow L, Shapiro C (2007) Antitrust. In: Polinsky AM, Shavell S (eds) Handbook of law and economics. Elsevier, North Holland, pp 1073–1225

Kazakova S, Cauberghe V (2013) Media convergence and media multitasking. In: Diehl S, Karmasin M (eds) Media convergence management. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 177–188

Keating B, Willig RD (2015) Unilateral effects. In: Blair RD, Daniel Sokol D (eds) The oxford handbook of international antitrust economics, vol 1. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 466–508

Kerber W, Schwalbe U (2008) Economic principles of competition law. In: Säcker FJ et al (eds) Competition law: European community practice and procedure. Sweet & Maxwell, London, pp 202–393

El Khaoudi Y (2018) Deutscher Streaming-Markt: Netflix überholt Sky – Amazon thront auf Platz 1. Chip Online, 21.10.2018, https://www.chip.de/news/Deutscher-Streaming-Markt-Netflix-ueberholt-Sky-Amazon-thront-auf-Platz-1_150896945.html (accessed 16 Feb 2020).

Krei A (2019) Geschäftszahlen 2018 vorgelegt, RTL Group will 350 Mio. Euro in Streaming investieren. DWDL, 13.03.2019, https://www.dwdl.de/nachrichten/71413/rtl_group_will_350_mio_euro_in_streaming_investieren/?utm_source=&utm_medium=&utm_campaign=&utm_term= (accessed 06 Feb 2020)

Kupferschmitt T (2018) Onlinevideo-Reichweite und Nutzungsfrequenz wachsen, Altersgefälle bleibt, Ergebnisse der ARD/ZDF-Onlinestudie 2018. Media Perspektiven 9(2018):427–437

Lindstädt-Dreusicke N, Budzinski O (2020) The video-on-demand market in Germany—dynamics, market structure and the (special) role of YouTube. J Media Manag Entrepren 2(1):108–123

McKenzie J, Crosby P, Cox J, Collins A (2019) “Experimental evidence on demand for “on-demand” entertainment. J Econ Behav Organ 161:98–113

Ofcom (2018) Public service broadcasting in the digital age, https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0026/111896/Public-service-broadcasting-in-the-digital-age.pdf (accessed 26 Dec 2019).

Pauker M (2021) Netflix startet linearen Sender international, W&V Online, 25.01.2021, https://www.wuv.de/medien/netflix_startet_linearen_sender_international (accessed 18 June 2021).

Prince J, Greenstein S (2017) Measuring consumer preferences for video content provision via cord-cutting behavior. J Econ Manag Strateg 26(2):293–317

Revilla MA, Saris WE, Krosnick JA (2014) Choosing the number of categories in agree-disagree scales. Sociol Methods Res 43(1):73–97

Richter F (2019) The generation gap in TV Consumption, https://www.statista.com/chart/15224/daily-tv-consumption-by-us-adults/ (accessed 13 Feb 2020)

Ritzer G, Jurgenson N (2010) Production, consumption, prosumption: the nature of capitalism in the age of the digital prosumer. J Consum Cult 10(1):13–36

Rubenking B, Bracken C, Sandoval J, Rister A (2018) Defining new viewing behaviours: what makes and motivates TV binge-watching? Int J Dig Televis 9(1):69–85

Shelton S, McKaig N, Mendez CG (2016) Television viewership among millennials: an analysis of millennials usage and preferences of on-demand & broadcast television services. Association of Marketing Theory and Practice Proceedings 2016. 7. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/amtp-proceedings_2016/7 (accessed 05 June 2021).

Simons N (2015) TV drama as a social experience: an empirical investigation of the social dimensions of watching TV drama in the age of non-linear television. Communications 40(2):219–236

Spilker HS, Ask K, Hansen M (2020) The new practices and infrastructures of participation: how the popularity of Twitchtv challenges old and new ideas about television viewing. Inf Commun Soc 23(4):605–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1529193

Statista (2018) Netflix Is Americans' Platform of Choice for TV Content, https://www.statista.com/chart/14559/americans-favorite-tv-platforms/, accessed 9th October 2019.

Statista (2020) Durchschnittliche tägliche Fernsehdauer in Deutschland nach Altersgruppen in den Jahren 2018 und 2019, based on AGF, GfK https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/152389/umfrage/durchschnittliche-fernsehdauer-pro-tag/ (accessed 13 Feb 2020).

Steemers J (2014) Selling television: addressing transformations in the international distribution of television content. Media Ind J 2:44–49

Stöhr A, Noskova V, Kunz-Kaltenhäuser P, Gaenssle S, Budzinski O (2020) Happily ever after? Vertical and horizontal mergers in the US media industry. World Compet 43(1):135–161

Tefertiller A (2018) Media substitution in cable cord-cutting: the adoption of web-streaming television. J Broadcast Electron Media 62(3):390–407

Turek R (2019) What content dominates on YouTube?, https://blog.pex.com/what-content-dominates-on-youtube-390811c0932d, (accessed 28 Oct 2019).

Van den Bulck H, Enli GS (2014) Flow under pressure: television scheduling and continuity techniques as victims of media convergence? Televis New Media 15(5):449–452

Vanberg V (2002) rational choice vs. program-based behaviour—alternative theoretical approaches and their relevance for the study of institutions. Ration Soc 14(1):7–54

WV (2019) Bilanz für 2018 und Ausblick, RTL Group verliert im TV – und investiert nun ins Streaming, in W&V online, 14.03.2019, https://www.wuv.de/medien/rtl_group_verliert_im_tv_und_investiert_nun_ins_streaming (accessed 06 Feb 2020).

YouTube Official Blog (2018) Introducing YouTube Premium, https://youtube.googleblog.com/2018/05/introducing-youtube-premium.html, (accessed 2019–10–28).

Zellner A (1962) An efficient method of estimating seemingly unrelated regressions and tests for aggregation bias. J Am Stat Assoc 57:348–368

Zellner A (1963) Estimators for seemingly unrelated regression equations: some exact finite sample results. J Am Stat Assoc 58:977–992

Zellner A, Huang DS (1962) Further properties of efficient estimators for seemingly unrelated regression equations. Int Econ Rev 3(3):300–313

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Apolte, Thomas Grebel, Stefan Heyder and the participants of the European Media Management Conference (Limassol, June 2019) and of Radein Reseach Seminar (Radein, February 2020) for valuable comments on an earlier version of the paper. Special thanks to the Office for Gender Equity (TU Ilmenau) for supporting the conference attendance of Sophia Gaenssle. Furthermore, we thank Valentina Wenzel, Charlotte Volk, Julia Diana Adschalow and Janine Dietz for valuable assistance

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Budzinski, O., Gaenssle, S. & Lindstädt-Dreusicke, N. The battle of YouTube, TV and Netflix: an empirical analysis of competition in audiovisual media markets. SN Bus Econ 1, 116 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00122-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-021-00122-0