Abstract

Despite significant progress in gender equality, pervasive gender stereotypes and discrimination persist worldwide. These ingrained perceptions, based on gender, contribute to the disadvantage experienced by women in multiple areas of their lives. This is especially evident in female professionals studying and working within male-dominated fields like Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine (STEMM), where the representation of women collectively amounts to less than 17% in Australia. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate how female undergraduate students in STEMM fields conceptualised gender-based stereotypes within their academic programs, and how these experiences shaped their outlook on being women in a field that defies traditional gender norms. Employing an exploratory qualitative approach grounded in the social constructionist, and feminist, perspectives, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were carried out with 13 female undergraduates in STEMM disciplines, aged between 19 and 43, from Australian universities. An inductive reflexive thematic analysis of the data led to the construction of four themes that contribute to the comprehension of how female undergraduates recognise and manage prevalent gender-based stereotypes during the early stages of their professional journeys. Participants recognised their gender and its related traits as a drawback to their presence in STEMM, and felt that these attributes did not align, leading to a sense of academic disadvantage. The prevalence of male supremacy within STEMM was acknowledged as originating from the embedded patriarchal system within these fields, granting undeserved advantages to male undergraduates, enabling them to perpetuate a narrative that solely favours them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite significant advancements in promoting gender equality in recent decades, gender stereotypes and discrimination continue to be pervasive issues on a global scale (Heilman and Caleo 2018). These deeply ingrained stereotypes often associate femininity with inferiority and incompetence, leading to various disadvantages for women in different aspects of their lives. These disadvantages include receiving subpar education and mentorship, as well as having fewer job opportunities (Hentschel et al. 2019; Hoskin 2020). This issue becomes particularly pronounced in the context of women’s professional careers, especially in male-dominated fields (Heilman and Caleo 2018). Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine (STEMM) fields are commonly perceived as ‘masculine’, with women accounting for less than 17% of the workforce in these areas in Australia (Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources 2019). Despite various interventions, this gender imbalance persists, primarily due to the perpetuation of implicit gendered stereotypes (Bloodhart et al. 2020).

Challenges and progress in advancing gender equity in Australian academia: Focusing on STEMM fields

One of the central issues in the ongoing gender equity debate revolves around women’s progression within organisational hierarchies, notably within academia (Winchester and Browning 2015). Catalyst (2021) reported that women comprise 28% of board directors, 18% of managers, and 3% of chief executive officers (CEOs). Breaking this down further, when exploring particular STEMM fields (where women have been suggested to face significant underrepresentation; SAGE 2016), representation is just as minimal. Representation of women within Engineering worldwide sits at 16% (Women’s Engineering Society 2022), 19% within Mathematics, and 22% within Technology (World Economic Forum 2022), but sits progressively higher at 46% within the Sciences (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO] Institute for Statistics 2021). Overall, in 2022, the global gender gap has been closed at 68.1%, and with the current rate of progress, will take 132 years to reach parity (World Economic Forum 2022). While women are gradually becoming more represented, the data suggests that there is a significant gap between the genders when considering their representation in STEMM.

When compared to their male counterparts, female academics are consistently confronted with disparities: they are less likely to hold senior positions, receive fewer scholarships and grants, earn lower annual salaries, and are less frequently considered for promotions and tenure (Lee and Won 2014). Moreover, Heijstra et al. (2014) discovered that women academics often experience heightened expectations to shoulder more responsibilities, such as additional student mentoring, increased service hours, and a greater volume of research output, in an effort to overcome perceived subordination in the academic setting.

Various explanations have been proposed to account for the underrepresentation of women in senior positions, with one of the most frequently cited factors being the interplay of structural, organisational, and personal barriers (Johns 2013; Yousaf and Schmiede 2017). Structural barriers revolve around positions of power traditionally associated with competence and authority; characteristics often linked to masculinity. Women may face a double bind, where they can be perceived as being too assertive (violating gender norms surrounding femininity), or not assertive enough (which violates norms of leadership and masculinity; Nash and Moore 2019). Such stereotypes about women’s competence and leadership abilities can contribute to biased evaluations, making it more difficult for women to ascend to leadership positions (McCullough 2011). This association finds support in Berger and Wagner’s (2007) expectation states theory, which posits that broader societal beliefs about gender-related attributes influence assumptions about an individual’s capabilities. For instance, when a woman assumes a leadership role, the expectation states theory predicts that she may encounter professional criticism rooted in perceptions of her illegitimacy, thus shedding light on the relationship between gender and senior positions (Berger and Wagner 2007). This highlights the impact of macro-level beliefs on individual experiences.

Organisational barriers encompass the societal norms that dictate traditional gender roles, where men are typically seen as providers, reinforcing the expectation that they should occupy senior positions. This ingrained perspective leads to a bias favouring men during the recruitment process (Yousaf and Schmiede 2017). In alignment with these societal norms, women are often expected to adhere to gendered stereotypes, which may lead to them prioritising domestic and familial responsibilities over their careers. This, in turn, contributes to the lower desirability of women for senior positions, as it is assumed that they may struggle to balance multiple roles and responsibilities (Weisshaar 2017). Feminist leadership advocates for the implementation of gender-inclusive policies within organisations to address such systemic barriers and promote equal opportunities (Cole and Hassel 2017). Recognising and addressing challenges related to work-life balance is a key aspect of feminist leadership, as women can face additional expectations and responsibilities outside of the workplace (Weisshaar 2017).

Personal barriers encompass a range of factors, including the belief that women may lack the time, interest, or skills required to excel and attain senior positions in academia, which leads to their underrepresentation when compared to male academics (Yousaf and Schmiede 2017). These beliefs result from a combination of societal expectations regarding women’s roles, gender-based stereotypes, and an internal deficit in self-efficacy beliefs and self-confidence (Greguletz et al. 2018). These personal attributes, often considered crucial for the perseverance and resilience of women in counter-stereotypic fields, play a significant role in the perpetuation of this issue.

Efforts to increase the representation of women in the workplace and academia in Australia have been notable, in part due to the implementation of various government legislations, such as the Sex Discrimination Act (1984) and the Workplace Gender Equality Act (2012), along with institutional policies (Liu et al. 2019; Voorspoels and Bleijenbergh 2019). As a result of these measures, the representation of women in Australian academia has more than doubled from 20 to 47% between 1980 and 2019, and senior positions held by women have increased from 6 to 31% (Winchester and Browning 2015). Despite these improvements, and the legal condemnation of gender-based discrimination in organisations, women continue to face significant underrepresentation in higher academia. This issue becomes particularly pronounced when considering STEMM fields, where gendered stereotypes still persist.

The impact of early experiences and academic environments on gender disparities in STEMM education and careers

According to Science in Australia Gender Equity (SAGE 2016), female representation within STEMM fields stands at 40% at the undergraduate level, but drops to less than 20% at senior positions. This phenomenon is commonly referred to in the literature as the ‘leaky pipeline’, where the retention rates of women decline as they transition from STEMM undergraduate programs to academic careers (Resmini 2016). Several factors have been attributed to this ‘leaking’, including the lack of female role models in STEMM, male favouritism in science and math education, and inadequate support for women in university settings (Blickenstaff 2005).

The underrepresentation of professional women in STEMM not only constitutes a contemporary issue, but also serves as a significant predictor of female students’ likelihood to pursue and persist in STEMM fields (Kim et al. 2018). Gonzalez-Perez et al. (2020) investigated the impact of interventions featuring female STEMM role models on school-aged girls, and their preferences for pursuing tertiary STEMM studies. They found that these interventions not only had a positive and significant effect on girls’ aspirations and expectations of success in STEMM, but also had an additional, beneficial effect of diminishing gendered stereotypes. In other words, exposure to successful women in STEMM fields significantly reduced internalised gendered stereotypes associated with female competence in male-dominated domains. These findings illustrate a self-perpetuating cycle of gender imbalance where the lack of women in STEMM roles discourages young women from pursuing STEMM careers, thus perpetuating the underrepresentation of females in these fields. To counter this, it is important that efforts to empower women in STEMM involve mentorship and support to connect aspiring academics and leaders with experienced mentors that can provide guidance (Beck et al. 2022). Feminist scholarship encourages efforts to build the confidence of women in academia, to address imposter syndrome and other confidence-related challenges (Nash and Moore 2019).

Experiences during an individual’s formative years have a profound impact on their self-concept and decision making, especially when we consider pedagogy in STEMM fields (Reinking and Martin 2018). Gender-biased perceptions that science and mathematics are inherently ‘boys’ subjects still persist among educators, diminishing the importance of early STEMM engagement for girls (Dorph et al. 2018). Moreover, research reveals that both female school-aged children and undergraduates receive less attention from educators, despite being more actively engaged during lessons, such as asking questions and participating in discussions. Paradoxically, they often achieve higher grades than their male peers (Dorph et al. 2018; Aguillon et al. 2020). This persistent disengagement from the STEMM learning environment negatively impacts female students’ self-efficacy and perceived competence in these subjects, significantly reducing their likelihood of pursuing further studies.

Traditionally, universities prioritise the recruitment of female undergraduates in STEMM, but often overlook strategies to support their retention once they are part of the academic setting (Blackburn 2017). Additionally O’Connor et al. (2019) found that male undergraduate STEMM students possess an invisible advantage in the form of mentoring and sponsorship favouritism. Male students are significantly more likely to receive guidance from senior academics throughout their degree, more sponsorships from internal and external organisations, and have more accessible student support groups than their female counterparts. This can lead to female students feeling marginalised in STEMM fields, ultimately resulting in a lack of diversity and inclusion.

The influence of gendered stereotypes on societal evaluations, perceptions, and roles

While the underrepresentation of women in STEMM fields is the result of a complex interplay of factors, the most frequently cited contributing factor is the perpetuation of gendered stereotypes (Blackburn 2017). Gendered stereotypes are characterised as internalised generalisations made about individuals based on oversimplified perceptions of their gender, rather than their actual abilities or characteristics. These stereotypes often take root in childhood, and persist into adolescence (McKinnon and O’Connell 2020). When a particular group is negatively stereotyped, an individual’s membership in that group can significantly influence their experiences and interactions (McKinnon and O’Connell 2020).

Smeding (2020) highlights the most prominent gendered stereotype affecting STEMM fields, namely the belief that, biologically, women possess lesser cognitive abilities in areas deemed crucial within STEMM (e.g., spatial awareness, logical reasoning). This perception can be best understood through the lens of implicit theories of intelligence, which posits that intelligence is viewed as an innately malleable trait in men, but as a fixed trait requiring external effort in women (Todor 2014). As STEMM disciplines are perceived to demand an innate aptitude for raw intellectual talent, this stereotype contributes to the underrepresentation of women in STEMM by implying that women’s intellectual capabilities are insufficient for these fields (Leslie et al. 2015). Conversely, social sciences and humanities disciplines are considered to require an inherent aptitude for communication and empathy, traits often viewed as centrally feminine (Leslie et al. 2015). These stereotypes significantly predict STEMM self-efficacy and career motivation, shedding light on female attrition rates and the initial reluctance of women to pursue STEMM fields (McGuire et al. 2020).

A second theory shedding light on this phenomenon is Eagly’s social role theory (Eagly and Wood 2012). According to this theory, gendered stereotypes form as we observe male and female behaviours during socialisation, leading us to unconsciously infer that each gender possesses certain concrete dispositions. Hentschel et al. (2019) acknowledge that in both industrialised societies (e.g., Australia) and developing ones (e.g., Pakistan), women traditionally tend to occupy caregiving roles. This has given rise to corresponding generalisations that women are more emotionally attuned, nurturing, and communal. In contrast, men traditionally lean towards provider roles, leading to generalisations that they are more dominant, independent, and agentic (Hentschel et al. 2019). These inferences, in turn, translate into negative societal evaluations of individuals who exist outside their societally prescribed roles. For instance, when a woman is found in traditionally masculine domains, she may face societal biases and stereotypes (Hentschel et al. 2019).

Implicit gendered stereotyping and its consequences for female undergraduates in STEMM fields

Goldman (2012) found that female STEMM undergraduates are often aware of the existence of gendered stereotypes within their field. However, they frequently encounter difficulties in connecting their own experiences to instances of gendered stereotypes and discrimination, despite openly describing academic and social experiences directly influenced by these stereotypes (Goldman 2012). This phenomenon can be seen as a potential coping mechanism, where female students dissociate their negative interactions and experiences as a means of self-preservation within an environment they perceive as hostile (Mahoney and Benight 2019). These findings reveal a concerning disconnect in which female STEMM students may not be immediately conscious of potential mistreatment or sexism within their academic journey. As a result, female students may not attribute gender as a factor contributing to disparities in opportunities, experiences, and support in comparison to their male counterparts (Goldman 2012).

Pitman et al. (2017) found that gender disparities are reflected in the experiences of female students who graduate from non-traditional areas of study, particularly in STEMM. These female graduates not only face challenges in obtaining paid work during their final year of study but also encounter difficulties in securing post-graduate employment relevant to their degrees, especially when compared to other disadvantaged groups, such as those from low socio-economic backgrounds or Indigenous Australians. In instances where these female STEMM graduates do secure post-graduate employment, they are more likely to be in casual or temporary positions, with full-time positions being predominantly occupied by male graduates (Pitman et al. 2017). These findings underscore the profound impact of implicit gendered stereotypes, and their far-reaching consequences, for undergraduate women at all stages of their STEMM journey.

Research rationale

Gendered stereotypes create significant barriers for women pursuing careers (Hentschel et al. 2019). It is particularly intriguing to investigate how these internalised gender evaluations affect women in careers that defy traditional stereotypes (Lorz et al. 2011; van der Vleuten et al. 2016). Current research on gendered stereotypes within STEMM fields predominantly centres on established professionals (Fagan and Teasdale 2021), overlooking the nuanced experiences of female undergraduate students embarking on their STEMM journeys. This gap in the literature is significant, as it neglects a critical stage in the academic and professional development of women in STEMM. The significance of understanding gendered stereotypes, and how they manifest during these formative years to impact on women’s career trajectories in STEMM (Brownhill and Oates 2017; Aidy et al. 2021), need further exploration, as the early stages represent a pivotal period where individuals shape their identities, aspirations, and career trajectories (Lorz et al. 2011; Cohen et al. 2021). The omission of this demographic in existing literature can limit the comprehension of how gendered stereotypes impact career choices and hinder the development of a diverse and inclusive STEMM community. Highlighting the significance of exploring gendered stereotypes during the formative years of STEMM education emphasises the long-term potential consequences on career trajectories (Lorz et al. 2011; Brownhill and Oates 2017; Aidy et al. 2021; Cohen et al. 2021). Investigating these stereotypes at this stage can provide insights into the factors that may influence women’s decisions to persist or deviate from STEMM pathways. By recognising and addressing challenges early in the academic journey, interventions could be developed to foster a supportive and equitable environment, ultimately contributing to increased diversity in STEMM professions (Fagan and Teasdale 2021). The proactive approach is essential for cultivating an environment that encourages the retention and success of women in STEMM disciplines (Blaique et al. 2023).

This study aims to explore how female undergraduate students currently studying in STEMM conceptualise gendered stereotypes during the formative years of their careers. I employed an exploratory qualitative methodology to gather in-depth data that fosters a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon. The choice of an exploratory qualitative methodology stems from the nature of the research, seeking to delve into the nuanced and lived experiences of female undergraduate students in STEMM regarding gendered stereotypes. This approach is deemed fitting as it allows for a holistic exploration of the complexities inherent in these experiences (Peshkin 1988). Much of the research conducted thus far in this area has primarily used quantitative methodologies to identify specific categories of gendered stereotypes prevalent in STEMM fields. Quantitative methodologies, while valuable for establishing patterns and general trends, may fall short in capturing the intricate nuances associated with gendered stereotypes (Christiaensen 2001; Poudel 2014). The inherent complexity of these stereotypes, intertwined with personal narratives and subjective experiences, can be inadequately addressed by numerical data alone. Quantitative research may overlook the richness of individual stories, and the contextual factors shaping the perceptions of female undergraduate students in STEMM (Rendle et al. 2019).

The adoption of qualitative methods is motivated by their capacity to provide a richer, more in-depth and holistic understanding of the complex ways in which gendered stereotypes manifest in the lives of female STEMM undergraduate students (Christiaensen 2001; Poudel 2014; Rendle et al. 2019). These methods enable us to uncover the subtle nuances, contradictions, and contextual variations that quantitative measures may overlook. Through semi-structured open-ended interviews, and reflexive thematic analysis, I aimed to capture the multifaceted nature of these experiences, allowing participants to express their narratives authentically. Qualitative methods enabled the exploration of the emotional and subjective dimensions of gendered stereotypes, offering a more comprehensive portrayal of the lived reality of women in STEMM. The research question guiding this study is: “How do female undergraduate STEMM students conceptualise gendered stereotypes and discrimination within their field of study?”

Method

Research design

I employed an exploratory qualitative design to capture in-depth participant experiences among undergraduate women in STEMM fields, aiming to gain a deeper understanding of how they conceptualised gendered stereotypes and discrimination within their academic domain (Rendle et al. 2019). I adopted a social constructionist epistemology, acknowledging the existence of multiple realities, and enabling the construction of a shared reality through various perspectives (Ultanir 2012; Phillips 2023). Anchored in a social constructionist epistemology, the investigation recognised how individual experiences can be crafted through dynamic interactions within social and cultural milieus (Ultanir 2012; Phillips 2023). A rich foundation for understanding was provided through the dynamic and contextual nature of the study, supplemented by the acknowledgement of the influence of social and cultural contexts on individual experiences. This epistemological lens presented a strong foundation for a thorough exploration of female undergraduate students STEMM experiences, unveiling a spectrum of gendered stereotypes that shaped their experiences. The epistemological approach aligned with the feminist theoretical perspective, essential for critically examining gendered systems, unveiling inequities, and interrogating societal expectations placed on women within STEMM fields (Radtke 2017; Phillips et al. 2022, 2023). Drawing from both social constructionism and feminist theory, I aimed to move beyond recognising gendered disparities to consider a nuanced exploration of the underlying power structures influencing the experiences of undergraduate STEMM women. These perspectives allowed for me to identify and dismantle subtle forms of discrimination, explore the impact of societal norms on women’s roles, and empower women in challenging gendered stereotypes.

Feminist theory facilitated a critical examination of gendered systems inherent in academic environments, with the acknowledgement of the patriarchal structures prompting an exploration of how these systems influenced the lived experiences of STEMM undergraduate women, their education, and their future careers (Sarseke 2018; Dekelaita-Mullet et al. 2021). There was also a commitment through adopting such a lens to unveil and dismantle inequalities that were rooted in gender, identifying, and understanding, the particular challenges and disparities faced by undergraduate women in STEMM, shedding light on both overt and subtle forms of discrimination that shape their academic journeys (Hooks 2000). Feminist theory also allowed for me to interrogate the traditional gender roles and societal expectations placed on women (Phillips et al. 2022), exploring how societal norms and expectations influenced the perceptions and treatment of undergraduate women in STEMM. Finally, I was also able to consider empowerment and agency from a feminist perspective, considering how undergraduate STEMM women engage in strategies to assert their agency, fostering a more nuanced understanding of their experiences. Overall, by integrating feminist theory into the social constructionist epistemological approach, I could foster a deeper understanding of the complex and intersectional dynamics shaping the academic journeys of women in STEMM (Sarseke 2018; Dekelaita-Mullet et al. 2021; Phillips 2023).

Researcher positionality

I recognise that my background and personal experiences within the Australian public higher education system have significantly shaped the approach, and design, of this research project. Therefore, it was crucial for me to consistently maintain a reflexive stance, and consciously position myself within the research process. This reflexive positioning has been an ongoing, continuous aspect of my work. I personally identify as an Anglo-Australian, cisgender male, belonging to the LGBTIQA+ community, and serving in an early-career tenured academic role that encompasses both teaching and research responsibilities. I am aware that my position embodies certain elements of diversity, yet it also mirrors some of the most common identities prevalent in academia, particularly those related to being white, cisgender, and male. Consequently, it was essential for me to acknowledge the specific privileges associated with my identities and actively address their impact while conducting this research. Throughout the research process, I adopted a pragmatic approach to navigate these inherent tensions. Engaging in reflexive practices has been a fundamental strategy to ensure the rigour and authenticity of the findings. I deeply value the importance of reflexive practice in comprehensively exploring and being cognisant of how my personal positioning might influence both the research process and the interpretation of the findings.

Participants

The sample for this study comprised 13 female undergraduate students currently pursuing STEMM degrees at various Australian universities. These students were enrolled in years one, through four, of their respective programs. To capture the insights related to the study’s focal points, face-to-face semi-structured interviews were conducted. Participants were recruited through purposive and convenience sampling methods. These methods of sampling are particularly appropriate for qualitative research as they involve purposeful and strategic participant selection, which corresponds to the aim of exploring specific phenomena, contexts, and experiences within the selected group (Andrade 2021). This approach helped guarantee that the gathered data was significant, comprehensive, and closely connected to the study’s goals. Additionally, the research, being situated within university settings, allowed access to a readily available population that met the inclusion criteria (Jager et al. 2017). Recruitment efforts were carried out through multiple channels, including advertising on social media platforms (e.g., university group pages on Facebook), distributing flyers within STEMM cohort buildings across university campuses, and through a student participant pool.

The choice of the sampling method and the sample size was guided by the principle of information power, where the relevance of the information held by the sample in relation to the research question informs the necessary sample size (Malterud et al. 2015). In accordance with Malterud et al. (2015), this study achieved adequate information power by considering the study’s specific aim, use of established theory, the sample’s specificity, the quality of the dialogue during the interviews (evident in the researchers’ conversational fluency, evidence of prompting and elaborating on the dialogue provided by participants, and the participants’ expertise on their experiences), and the analysis strategy. Comprehensive demographic information for all participants is provided in Table 1.

Materials

A semi-structured interview guide was developed to facilitate conversational structure while allowing room for additional probing if needed for clarification or further elaboration from participants (Jamshed 2014; Korstjens and Moser 2017). This approach aimed to build rapport, ensuring a comfortable and in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences within the STEMM domains (Jamshed 2014; Korstjens and Moser 2017). The development of the interview guide was an iterative process, involving reflexive engagement to ensure questions aligned with the research focus (Korstjens and Moser 2017). Fourteen questions were formulated which aimed to explore participants’ perceptions of gendered stereotypes in STEMM, ranging from broad to detailed inquiries. The guide was designed to allow for an interview of approximately 60 minutes in duration. Additionally, a demographic questionnaire was created that inquired about participants’ age, academic year, and specific STEMM field. The questionnaire did not request any personally identifiable information or link directly to the interview data. Participants were asked to complete the demographic questionnaire before the interview. Participants were informed that they could leave this questionnaire blank if they preferred not to disclose such information. All collected information was de-identified.

Procedure

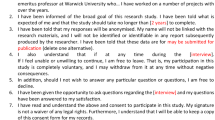

Following approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC2021-0243), recruitment efforts began. Participants were encouraged to contact me using the provided email on recruitment flyers. Eligible participants received information sheets and consent forms to review and sign before the interview, which was then conducted either on the university campus (in settings such as the cafe, meeting room, or library) or via electronic platforms (e.g., Zoom or Skype).

Prior to the interviews, the study’s purpose and the session’s agenda were explained to the participants. They were asked to provide their signed consent forms and given the opportunity to ask any questions. The interviews typically lasted between 20 and 45 minutes (M = 35 minutes). Towards the end of the session, participants were invited to add any further points relevant to the research topic. All audio recordings were transcribed, ensuring the removal of any identifying information, and subsequently, these records were securely disposed of. The transcriptions were printed and subjected to analysis using a paper and pen approach, employing reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006, 2019, 2021). The interviews, transcription, and analysis phases were conducted iteratively, allowing for repeated movement through the stages as required, gradually progressing towards their conclusion through ongoing engagement. Participants were given the change to opt-in for member checking, allowing them to provide feedback on the preliminary data analysis. The feedback received from the participants was integrated into the research findings.

Data analysis and quality procedures

An inductive, reflexive, thematic analysis approach was employed, following the guidelines by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2019, 2021). Instead of being rooted in any pre-existing framework, this analysis aimed to capture the firsthand experiences of female undergraduate STEMM students regarding gendered stereotypes and discrimination within their academic domain. It delved into the contextual aspects that influenced and underpinned their academic experiences. Immersion into the data involved listening to audio recordings and conducting transcriptions. Initial coding, capturing both explicit and underlying content, was constructed inductively. Subsequent coding involved the organisation of these codes into broader categories based on their relationships, leading to the construction of distinctive themes. These themes were continuously reviewed, refined, named, and defined. The final findings, detailed in the following section, incorporate comprehensive descriptions and pertinent quotes to encapsulate their essence.

To ensure the study’s quality and trustworthiness, various quality assurance measures were implemented. The semi-structured interview guide underwent scrutiny and pilot testing before data collection to refine it for addressing the overarching research question, and to identify any areas necessitating revisions in the interview framework (Abdul Majid et al. 2017). Additionally, a reflexive journal was maintained to facilitate ongoing reflection on, and processing of, the interviews, serving as a record and audit trail for pertinent information influencing the analysis (Morrow 2005; Yardley 2017). Subsequently, following the collection and analysis of all interviews, participants were offered the opportunity to voluntarily participate in member checking. This involved presenting a summary of the key research messages to the participants, enabling them to offer feedback on the accuracy and impartiality of the interpretations, and allowing for additional insights to be incorporated into the research (Locke and Velamuri 2009).

Findings

Four overarching themes exploring the experiences of female undergraduate STEMM students regarding gendered stereotypes and discrimination within their academic domain were constructed. Whilst each of the students’ experiences were unique, there were also commonalities across experiences. These constructed understandings are presented in the following themes: (1) Tradition’s Shackles and Subconscious Survival: Navigating Gender Roles in STEMM Academia, (2) Constrained Pathways: The Impact of Femininity on Academic Pursuits in STEMM, (3) Challenging the Boys Club: Perils of Masculinity in the STEMM Gender Battleground, and (4) Bearing the Weight: Female Undergraduate Students’ Sisyphean Struggle in STEMM. Identifying information has been removed and replaced with [descriptor].

Tradition’s shackles and subconscious survival: Navigating gender roles in STEMM academia

This thematic exploration delves into how participants perceived and grappled with traditional gendered roles, which have persisted across generations, significantly influencing their experiences as women in a field that goes against stereotypical norms. Such experiences revealed how undergraduate women navigated, and sometimes rationalised, their encounters with gender-based stereotyping.

When examining their comprehension of gendered stereotypes, participants frequently attributed these perceptions to traditional societal norms, recognising historical gender-based roles as the established societal standard: “…back in the old days when it was ‘women are supposed to be at home, in the kitchen, raising babies and men were the head of the house’, men got the jobs and the money”. This sentiment illustrates an acknowledgement of ‘traditional masculinity’ and ‘traditional femininity’, where men were expected to be providers and protectors, and women were expected to assume nurturing roles. Such entrenched beliefs might contribute to the diminished desirability of women in STEMM fields, as their designated societal roles are considered incongruent with these traditions.

Acknowledgement of these traditional gendered roles also involved recognising their perpetuation across generations: “…it’s so ingrained in society and our culture I suppose… it’s still just from traditional ways of thinking that are leftover”. Here, the participant indicated that these stereotypes, deeply rooted in history, persist in modern society, continuing to shape societal expectations, particularly in academia. Participants reflected on this perpetuation, hinting that it subconsciously reinforces different priorities in academia between men and women. For instance, a participant contemplated the future, recognising the potential impact of family planning on their career:

I don’t feel pressured, I feel like ‘oh my god if me and my girlfriend get married in XYZ years, and then we have kids here, I’m going to have to have a job by then, which means I can’t do some cushy little undergrad that’s going to take years, I’m going to need something that will get me money.

The above sentiment elucidates the profound influence of traditional gender roles and stereotypes on participants, indicating a perceived pressure to pursue higher education and job opportunities aligned with historically defined roles. From a female perspective, one participant reveals that considerations about future family planning significantly affected her choice of university course:

…when I was deciding what course I wanted to do at university, I can’t just think, oh what do I want to be when I grow up, I had to think about if I ever want to have kids and get married. I know some people say when you go to a job interview don’t tell them that you’re like engaged or recently married cause then they think she’s going to have to have maternity leave… and then they just go with the man cause he’s not going to have those like gender commitments a woman would.

Here, the fear of disclosing marital status or plans during job interviews to avoid assumptions regarding maternity leave suggests the impact of reinforced gender roles in decision-making. These traditional roles and stereotypes shaped participants’ views on what was feasible, while conforming to societal expectations and personal growth.

When discussing gendered stereotypes within STEMM, participants demonstrated a tendency to rationalise and defend those inadvertently perpetuating these stereotypes, perceiving them as subconscious, rather than active stereotyping: “…it’s not like they’re actively stereotyping me…but it’s very subconscious”. This inclination suggests a level of acceptance and forgiveness among female students, serving as a survival strategy within a potentially hostile environment. Further, the idea of subconscious sexism was repeated across participants, with many of them passing blame to the concept of ‘innate desires’: “…the leaderships roles is what they naturally gravitate towards, and they just leave us to fill the other roles”. Here, the idea of ‘innate desires’ and the phrasing of ‘naturally gravitate towards’ insinuate biological determinism, emphasising that men are inclined to fulfill dominant roles, while women are left with lesser roles, such as administration.

Moreover, participants portrayed their experiences of gendered stereotyping as passive, suggesting that men were mostly unaware of their actions and bore minimal responsibility for perpetuating these stereotypes: “…it’s one of those things that you kind of just do without consciously thinking about it, like I don’t think they do it purposefully”. Throughout the interviews, the profound influence of traditional gendered expectations on women in an environment where they are perceived as outsiders is evident. The rationalisation of this sentiment suggests an innate survival mechanism adopted by undergraduate women, aiming to navigate and assimilate into this environment without stirring conflict.

The discussions within this theme underscore the pervasive impact of traditional gender roles and stereotypes on the academic experiences of female students in STEMM. These ingrained societal expectations dictate both the decision-making process, and the rationalisations made by participants, influencing their perceptions and interactions within the male-dominated fields. Participants revealed a nuanced perspective, acknowledging the subconscious nature of gendered stereotypes, but also displaying a degree of acceptance as a survival strategy in navigating this environment. Additionally, the attributions to ‘innate desires’ and unconscious actions hint at a belief in inherent gender roles, further reinforcing a biased social structure that disfavours women in certain roles within STEMM. This theme collectively demonstrates the enduring influence of societal stereotypes on the academic journey of undergraduate women in counter-stereotypical fields, revealing their strategic adaptations to survive and thrive in a challenging environment.

Constrained pathways: The impact of femininity on academic pursuits in STEMM

This theme delves into the intricate ways that femininity influences societal expectations, and subsequently, constrains the opportunities for individuals identifying with female gender roles. Participants unanimously expressed a notable gender-based division within STEMM fields. They observed women being channelled into the ‘softer’ or more people-focused roles, while men were predominantly favoured in the ‘harder’ or more prestigious technical positions. This categorisation perpetuates the cultural bias where high-status roles are typically seen as masculine domains, as one participant reflected:

…really a lot of the softer roles, I’m going to say that are more people focused, people tend to think are going to be reserved for women, and all of the more technical roles…I almost want to say more prestigious types of roles end up being reserved for men.

Here, this gendered distribution of prestige is often rooted in stereotypical assumptions, where men are ideated as possessing inherent intelligence suited for high-level positions, while women are more commonly typecase as nurturers suited for caring roles. One participant emphasised this societal view, stating: “I guess it’s the assumption that men are smarter than women purely because they’re men…and I feel like that’s reinforced the gender stereotype that women are carers rather than thinkers, or knower, or doers”. Consequently, this mindset perpetuates a perception that women in counter-stereotypical careers, such as in STEMM fields, are uncommon:

…it’s not thought of as a thing for them [women], it may not have even crossed their minds to go into these fields because they don’t think it’s the field they should be in. I guess just exposure is definitely important and having that background knowing that that’s an option.

This sentiment reveals the prevailing societal belief that women are incompatible with STEMM. Participants highlighted the lack of representation of women in these fields as stemming from a limited exposure to the possibility, and a lack of awareness that such careers are viable options for them. They indicated the necessity of early exposure and awareness to expand women’s understanding and confidence in considering these non-traditional career paths.

Participants expressed their apprehensions regarding this deeply ingrained attitude surrounding who was compatible working in STEMM, highlighting how this perspective not only confines women to fields considered ‘more suitable’ due to stereotypical traits, but also, dissuades them from venturing beyond these predetermined boundaries. One participant aptly captured this issue, reflecting: “I guess it’s probably like a power structure, like you normally see women working under men, like under the authority of men…”. This perception essentially equates femininity with inferiority, resulting in an academic disadvantage for those who identify with it.

Another aspect underscored by the participants was the underlying sense of belonging, or more aptly, the lack thereof, particularly as women in male-dominated spaces. One participant shared a subtle, yet impactful, experience:

I haven’t really felt it explicitly, it’s more in the way that I walk into the class, and I’m immediately seen as the thing that is different. You know? It like I walk in and it’s like ‘oh it’s the girl!’

This suggests that in such environments, gender becomes the defining characteristic for these women, overshadowing their skills and competence. Consequently, this intrinsic sense of not fitting in leads to feelings of self-doubt, self-awareness, and a sense of inadequacy. Even when women perform at the expected standard in their field, their gender becomes a perceived impediment. One participant expressed this challenge:

…you can’t view yourself as the ideal candidate there because that’s what you think they’re typically looking for [men]. Like…almost creating imposter syndrome…It’s probably where it stems from because women feel like they don’t meet that expectation or that stereotype, they feel like they shouldn’t be there.

This sentiment illustrates the self-consciousness among undergraduate women, who are acutely aware of their differences, and perceive their incompatibility within the STEMM stereotype. Furthermore, participants exhibited an acute awareness of both biologically, and socially imposed, responsibilities, such as motherhood, and how these responsibilities significantly affect their careers. As one participant articulated:

…it’s not necessarily that women get paid less for the same roles, it’s that women are being stay at home mums which delays their career, so men progress in their career and end up getting paid more. And you know, there’s a whole argument of like well that’s the woman’s choice but it’s actually like, well society’s ingrained into women that they should be the ones doing that.

This sentiment illuminates the challenging dichotomy women face—either focusing on their personal development and career growth, or succumbing to the societal pressures of fulfilling familial duties. Moreover, participants revealed the daunting challenge of balancing motherhood with career progression in a field typically regarded as masculine. The issue of women feeling compelled to choose between fulfilling their traditional responsibilities, and maintaining a successful career, emerged as a recurring concern. One participant expressed this struggle:

…while we’re trying to promote science degrees and science jobs, a lot of those on offer aren’t flexible. So for women who do want kids and know that when they have kids they’ll want time off, there aren’t those jobs available so therefore they’re going to steer away from them… because even if the degree is available and they can do it, they don’t see the job prospects that line up in the way that they want or need in order to fulfil the childbearing and familial responsibilities expected of them. It’s very much seen as you pick one or the other.

STEMM fields, long associated with masculinity, have created a perception of incompatibility with femininity. As a result, women who pursue careers in these disciplines often feel marginalised, particularly if they choose roles that do not align with traditional gender norms. This intensified sense of disconnection is further compounded by the weight of societal expectations attached to feminine roles.

This theme underscores the complex interplay between gender, societal expectations, and academic pursuits in STEMM fields. It illuminates how traditional perceptions of femininity and masculinity impede the progression of female undergraduates in these domains. Unveiling the societal assumptions, the narratives divulge the challenges of self-doubt, implicit biases, and the disparity between familial responsibilities and career advancement faced by these women. It also unveils a disheartening reality where gender stereotypes influence academic choices, and the difficult trade-offs that women feel forced to make between career aspirations and societal expectations. Ultimately, it highlights the persistent, multifaceted challenges faced by female undergraduate students navigating the STEMM landscape within higher education, where their identities and opportunities are significantly constrained by gender-based roles and expectations.

Challenging the boys club: Perils of masculinity in the STEMM gender battleground

This theme explores the oppressive aspects of the STEMM environment, focusing on the presence of a hyper-masculine culture. Participants extensively discussed the concept of masculinity, often characterising it as intrinsically powerful within the domain:

I guess it’s probably like a power structure, it’s like, you normally see women working under men like under the authority of men…I still think like men do see women as second-class citizens in STEMM, they probably perceive women as their assistants rather than like equal counterparts.

Such a sentiment suggests how the power structure, where men are typically positioned above women in authority, acts to then position women as secondary in the STEMM fields. This perception directly relates to gender inequity, and a hierarchical system that sustains men’s authority over women. The normalisation of this masculine culture further perpetuates unfair advantages, such as women feeling the need to exceed male performance levels to be considered for similar roles: “…to get the same job (as a man), as a woman I feel like sometimes you have to be twice as good as them to even be considered”. However, interestingly, participants in fields conventionally categorised as ‘soft sciences’, like health sciences and psychology, revealed that their femininity often acted as an advantage, creating a positive bias towards female professionals in these disciplines:

I don’t think the stereotypes will impact me in psych to be honest, because I think that there is a lot of women psychologists out there, I think a lot of people seek out female contacts to talk to… maybe if those stereotypes were weighed up against me, then yeah, but they are in my favour in this circumstance.

This finding indicates that in certain disciplines of the STEMM landscape, traditional feminine traits might be perceived favourably, potentially influencing how individuals view gender stereotypes, particularly when it benefits them.

A poignant aspect bought up by the participants was the prevalent perception of STEMM as a ‘boys club’, shaped by the striking gender imbalance in these fields: “I was the only one in my class… so it was 26 males [students], a male teacher, two male lab assistants and me”. The experiences shared by participants emphasise the profound isolation felt by women in this environment, vividly expressed through stark contrasts like being the sole female in a predominantly male cohort. This scenario solidifies the perception that women are incongruous in such fields, reinforcing the belief that they do not belong.

Participants added to this sentiment, revealing a coping strategy in such situations by forming alliances with close male classmates to shield themselves from biases and discriminatory remarks: “When I had them [close male classmates] with me, I felt really good, and you know there were things said to me and biases, but those boys protected me a bit from it you know? They defended me”. Here, reliance on male peers for protection highlights the distinct power differential in STEMM disciplines, indicating that women feel safer or more respected when supported, or defended, by male colleagues, underscoring the prevalent gender-based hierarchy within these fields. Moreover, participants described an arrogant and intimidating culture within this ‘boys club’, emphasising the presence of a self-assuredness bordering on narcissism among male counterparts:

…they’ve all just got this like really narcissistic self-belief that they’re better than everyone else…they just look at you, they look at you up and down from the moment you walk in like you are the dumbest person there.

Such an aura of superiority and the behaviour exhibited by male peers adds to the challenging atmosphere for participants, which also further perpetuates the ‘boys club’ mentality, creating an environment where women feel marginalised and undervalued. The perpetuation of exclusionary practices within STEMM fields significantly impacted the confidence and sense of belonging among undergraduate women, ultimately leading to their disengagement:

I’ve been tempted so many times to stop the degree because of the subtle way the culture is in STEMM, I can feel it wearing on me…you actually have to be quite strong to be able to realise that’s what it is and that it’s not you.

Here, the participant expresses their internal struggles, citing the pressure, and negative impact, of the cultural norms that have permeated these academic domains. The internal conflict experienced by female students reveals the taxing nature of these environments, forcing them to navigate a landscape fraught with subtle but persistent biases. This often results in an overwhelming feeling of self-doubt, and the temptation to abandon their educational pursuits. The impact of the culture of the ‘boys club’ was evident as participants acknowledged how male peers expressed resentment towards them challenging the traditional male-dominated space: “…back when I was doing [degree], it was ‘this is a men’s degree’ ‘why are you here?’ ‘don’t waste your time’”. Here, the participant shares an experience of facing disdainful comments and overt hostility, often being told they do not belong, or are wasting their time by pursuing a STEMM degree. Such verbal aggression and exclusion contribute to an environment where women feel unwanted and underappreciated, making it increasingly challenging for them to thrive in these spaces.

In addition to this, gender quotas introduced by various STEMM employers aimed at improving gender equity have inadvertently led to further concerns and apprehension among female undergraduates. Participants expressed their unease, anticipating being unfairly labelled as beneficiaries of gender quotas, rather than recognised for their capabilities and qualifications:

…the men that are in the job are like ‘oh you’re just here because you have to be, they had to hire you’. I don’t like assumptions being made that a woman is less capable and was hired out of pity because the company has a gender quota, it just means that their application gets seen and not immediately discarded because of her gender.

Such stigma casts a shadow on undergraduate female students’ achievements and engenders a sense of anxiety about their acceptance in these fields, despite their genuine passion and aptitude. Moreover, the structure and culture within these fields have established an unspoken hierarchy where men consistently wield their gender-based power and privilege, perpetuating their academic and professional advantages. This effectively reinforces the ‘boys club’ culture, intimidating female undergraduate students, and fostering a sense of bitterness among those who continue to strive in such unwelcoming environments. The challenges faced by these students in such exclusive settings underscore the deeply entrenched biases and hurdles women encounter in STEMM fields, posing significant barriers to their academic and professional growth.

The challenges faced by female undergraduate students within STEMM fields are inherently tied to the pervasive gender-based exclusivity and hostile culture they encounter. The theme illuminates the unwelcoming environment characterised by an entrenched ‘boys club’ culture, fostering a deeply ingrained sense of male superiority and exclusivity. The stories shared by participants emphasise the struggle and self-doubt experienced by women navigating these academic domains. The hostility and resentment displayed by male peers further compound the difficulties faced by women seeking to establish themselves in these fields. The attempts to address gender equity through quotas have led to unintended apprehension among female students, exacerbating their sense of being devalued and misunderstood within these academic spaces. Overall, this theme underscores the complex challenges and barriers that female undergraduate students confront in these fields, perpetuating a daunting atmosphere that significantly hampers their academic and professional advancement.

Bearing the weight: Female undergraduate students’ Sisyphean struggle in STEMM

This theme explores the plight of women, and their challenges within the STEMM environment, articulating the arduous journey they face in a traditionally male domain. The shared experiences revealed the heightened pressure that women feel to perform exceptionally, considering the necessity to prove themselves beyond any doubt. The burden described by the participants illustrated the need to continuously excel, maintaining higher standards to affirm their competence in an environment where they feel their very presence is questioned, based on their gender. A participant’s perspective here effectively captures this weight, as the obligation to appear competent and driven, is often met with scepticism or judgement:

…because I’m going to be the only woman, I’m going to have to make myself look really good, and I have to show that women can really do it kind of thing you know? I have to look like I know what I’m doing…I feel like sometimes I have to do it because it’s like ‘oh you’re a female you can’t fail in your industry’…I don’t want to give the guys a reason to judge me.

Here, the sentiment underscores the immense emotional and intellectual labour that female undergraduate students endure to dispel preconceived biases and perceptions about their abilities. Moreover, the discussion unveiled the discrepancy in effort exerted by female undergraduate students to be recognised and valued within STEMM fields. The emphasis on having to work disproportionately harder to earn equal regard elucidates the barriers that female undergraduate students encounter, as well as the challenging journey of dispelling perceptions of inadequacy, despite meeting academic standards:

I just feel like I had to work five times as hard to even be considered the same. I guess…I don’t know if it’s because I’m a woman or if it’s because of my personality, but everyone thought I was dumb, and so I had to fight to be like ‘no I’m just as smart as everyone else and I’m getting the marks’.

The sentiment effectively portrays the shared experiences of participants, and their ongoing struggle to counter biased assumptions rooted in gendered stereotypes that cast doubt on their abilities. The distinct pressure and rigorous efforts that undergraduate female students in STEMM fields endure to counter biased assumptions and prove their capabilities is noted, highlighting the discrepancies in perceptions, and the need to continually validate their intelligence and competence, despite possessing equal qualifications.

Participants consistently described their unsettling experiences, emphasising the pervasive stereotyping and the resulting sense of being undermined and undervalued. Such experiences vividly depicted the systematic overlooking and disregard faced by women when their contributions, opinions, and expertise are equivalent to or even exceed those of their male counterparts:

I remember saying something and putting my hand up in class and saying a comment about something we were talking about, and then I heard a man put up his hand and say pretty much the exact same thing as I did and the teacher was like “yeah!”, so he got praised and I was like… I literally just said that! But it was because it was coming from a man’s mouth.

Such recounting of this instance illustrates the reinforcing of bias and discrimination experienced by female undergraduate students. The experiences exemplify a disturbing trend where their contributions are sidelined or devalued when expressed by them, while the same comments made by men received positive affirmation. Another participant shared this sentiment, stating: “…why is my opinion different to his? Like we are both saying the same thing. And sometimes I am more experienced, so why are you looking at me like I don’t know anything”. These excerpts display how the contributions of undergraduate female students in STEMM are ignored and overlooked despite their comparable capabilities, and potentially superior expertise. This appears to stem from a perceived subordination experienced by undergraduate women when comparing themselves to their male classmates. Such an emotional toll is emphasised with female undergraduate students’ struggles to be recognised and respected for their skills and expertise. Another participant adds to this, and states:

…women are inferior to men, when it comes to [STEMM]… it will definitely affect my postgrad life, it’ll definitely affect my career if I go into the STEMM field, and I don’t think it will stop affecting it until I die.

This sentiment regarding the participant being perceived as inferior to the men in their field, as well as the anticipated longevity of this challenge in their postgraduate life and career, underscores the substantial and long-lasting impact of such gender-based biases. Such a portrayal articulates the psychological implications of gendered stereotyping, illustrating the distress and frustration experienced by undergraduate female students in STEMM who are continually required to perform to an extremely high standard. Simultaneously, their competence and intelligence are constantly questioned and often disregarded. These observations underscore the psychological toll of the imposed sense of subordination and ineptitude, despite the female students often excelling in their academic pursuits.

This theme delved into the ongoing struggles of female undergraduate students within the male-dominated STEMM environment. It emphasised the constant pressure that these women faced to validate their competence, describing their relentless efforts to counter gender biases and stereotypes that undermined their intelligence. The shared experiences vividly depicted how their contributions were overlooked and devalued, despite possessing comparable qualifications, reinforcing feelings of subordination and inadequacy. The female undergraduate students worked diligently to dispel stereotypes, fighting to be recognised for their skills, but encountered systemic challenges where their expertise was disregarded. The theme encapsulates the psychological toll of confronting such biases, revealing the taxing journey that female undergraduate students endure to establish their credibility in the STEMM domain.

Discussion

This study captured the experiences of female undergraduate STEMM students regarding gendered stereotypes and discrimination within their academic domain. Reflexive thematic analysis allowed for the identification of four themes that described their experiences. Female undergraduate students experienced an arduous battle in establishing their competence and credibility within male-dominated academic landscapes. This struggle was intensified by the need to continually prove their abilities, as their contributions were often dismissed, undervalued, or outright ignored, despite their equivalent or superior expertise. Female undergraduate students felt the amplified pressure to excel, requiring them to work exceptionally hard to gain respect and recognition compared to their male peers. Moreover, the psychological toll was substantial, as gender-based biases created feelings of inadequacy, and perpetual efforts to counter these stereotypes. Such challenges did not only impact their academic journey, but had far-reaching implications, affecting their future career prospects and fostering a continuous fight for validation within STEMM fields.

Gendered stereotypes are simplified notions about the traits, skills, and societal roles expected from both men and women (Hentschel et al. 2019). Whether openly antagonistic or deceptively harmless, these stereotypes can hinder a person’s development and the pursuit of specific careers. This effect is especially pronounced for women in fields like STEMM, which are contrary to stereotypical expectations (Johns 2013). It is vital to explore how female undergraduate students in STEMM perceive these stereotypes, and how these notions shape their understanding of being a woman in a predominantly male environment.

The participants’ reflections on gendered stereotypes within STEMM highlight the perpetuation of traditional gender ideologies across generations, particularly concerning the gendered division between professional and familial roles. Echoing Eagly’s social role theory (2012), participants recognised society’s disproportionate allocation of positions of authority to men based on perceived strength and intelligence, while assigning women to nurturing roles due to their reproductive capabilities. Such assignment perpetuates gendered stereotypes and discrimination within STEMM, as women are not conventionally linked to the field or its associated tasks (Smeding 2020).

The participants, although displaying a profound understanding of gendered stereotypes and their historical context, often struggled to link these broader concepts directly to their personal experiences regarding gender implications. When they did identify such connections, they tended to rationalise these occurrences, sometimes excusing those perpetuating the stereotypes. This discovery is particularly significant as it aligns with existing literature, indicating that women in male-dominated academic fields tend to downplay and rationalise these experiences as a method of self-preservation and coping (Goldman 2012; Mahoney and Benight 2019). Such tendency to rationalise these encounters represents a secondary coping mechanism for these women, enabling them to indirectly associate the implications of their gender with these experiences.

Participants frequently contemplated the nuanced concepts of femininity and masculinity within the STEMM context, associating femininity with detriment and masculinity with power and superiority. Viewed through the lens of feminist theory and gender stratification, these reflections highlight the socially constructed hierarchy that places masculinity at the apex (Heijstra et al. 2014; Hoskin 2020). Within STEMM, this hierarchy tends to favour male undergraduates at the expense of their female counterparts (Heijstra et al. 2014; Hoskin 2020). Participants recognised this imbalance as an outcome of the patriarchal structure embedded within STEMM, perpetuating male dominance and undervaluing female contributions, thereby silencing and marginalising female undergraduates. This system grants unearned supremacy to male STEMM undergraduates, enabling them to reinforce the narratives that serve their interests (Fagan and Teasdale 2021). Conversely, participants in predominantly female-dominated STEMM fields, such as health sciences and psychology, exhibited an entirely different perspective. They often emphasised, and glorified, the advantages of their gender and associated traits, indicating a significant benefit in their domains. This discrepancy reveals that those benefiting from perpetuating particular stereotypes tend to overlook the implications for others who do not share the same benefits. This dichotomy introduces a contemporary issue challenging the traditional feminist perspective, particularly in framing femininity as completely subordinate.

Throughout their university experiences, participants described an inherent pressure to consistently perform at exceptionally high levels to earn recognition and respect from male peers, resulting in what they perceive as an unequal learning environment. Corresponding with expectations state theory (Berger and Wagner 2007), participants viewed their gender as a significant obstacle in how their capabilities and intelligence are evaluated within STEMM disciplines, which historically have not been inclusive of women. This perception was evident in participants’ distinctions between the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ sciences, associating traits like nurturing and empathy with the soft sciences, where they are deemed more advantageous. Such distinctions align with existing literature, indicating that negative evaluations from peers towards female undergraduates’ stem from implicit assumptions about their character traits and perceived incompatibility with STEMM fields. This tendency further reinforces the belief in male superiority within these domains (Blackburn 2017; Bloodhart et al. 2020; Kim et al. 2018; McGuire et al. 2020). While acknowledging these gender-based judgements, participants may not fully recognise the role of their anticipatory anxieties of judgement, and the coping mechanisms they employ, particularly self-imposed overachievement, as strategies for avoidance and self-preservation (Mahoney and Benight 2019).

Implications and strengths

The study’s findings carry significant theoretical implications, substantiating Eagly’s (2012) social role theory, and Berger and Wagner’s (2007) expectation state theory. They shed light on how gendered stereotypes materialise through observed behaviour, and the implicit association of social roles with specific genders. Additionally, the study reveals how gender-based assumptions regarding capabilities and intelligence reinforce role segregation, intensifying the criticism faced by women in atypical roles, such as those within STEMM. The findings align with feminist theory, offering a framework to comprehend the inequality between sexes in counter-stereotypic domains (Radtke 2017; Hoskin 2020). This study is pioneering in its integration of social role, expectation state, and feminist theories, contributing fresh perspectives to this field. By employing a qualitative methodology, the study provides rich, in-depth insights into the experiences of undergraduate women in STEMM, filling a gap often overlooked by quantitative approaches. Such a methodological choice enriches the existing quantitative literature by providing depth and context to the findings.

The practical implications of this study are substantial. A deeper understanding of gendered stereotyping and gender discrimination could inform organisational support structures for undergraduate women in STEMM, aiming to nurture and empower their journey through the academic pipeline, potentially reducing attrition rates. Furthermore, the exploration of these experiences could form the basis for more effective sensitivity training for faculty and male students, addressing the prevailing culture that female undergraduates encounter. The findings are potentially transferable not only to undergraduate STEMM women in Australia, but could also be applicable to similar cultures globally, sharing traditional gender roles and values as identified in the study.

Limitations

While rigour was a priority within my study, certain limitations warrant consideration. The recruitment phase was challenged by significant gatekeeping encountered when attempting to advertise through university students STEMM Facebook groups, many of which were managed by male undergraduate students. As such, I was met with significant hesitancy and reluctance in cooperating to advertising the study, which subsequently affected the outreach of undergraduate women, and ultimately constrained the samples representation. The final sample primarily consisted of Caucasian women, lacking diversity in culturally diverse perspectives. Notably, it failed to include undergraduate Indigenous Australian women and women of colour, signifying a lack of diverse perspectives on gendered stereotypes in STEMM. Additionally, technology-specific fields’ perspectives were underrepresented due to recruitment gatekeeping, highlighting the absence of insights from this sector. Based on the above factors, this restricted a comprehensive exploration of diversity and intersectionality within the sample’s experiences.

Future research and conclusions

The current study offers reliable findings that enrich the existing literature on gendered stereotypes within STEMM fields. Future research directions could explore the influence of intersectionality and diverse identities on perceptions of gendered stereotypes in STEMM. Additionally, investigating male undergraduates’ perceptions of gendered stereotypes in these fields may offer valuable insights. Examining how gendered stereotypes vary across distinct STEMM disciplines, particularly in female-dominated (e.g., psychology) and male-dominated (e.g., engineering) fields, could shed light on their manifestation and impact. The persistent challenges faced by female undergraduate students in STEMM due to gendered stereotypes and discrimination highlight the urgency for comprehensive understanding and proactive measures. By delving into these stereotypes’ impact on those directly affected, this study illuminates the need for broader exploration, widespread knowledge dissemination, and educational campaigns within the STEMM community. Engaging in these initiatives becomes pivotal in reshaping the prevailing power structures that hinder women in these fields. Through informed awareness, educational strategies, and collective action, the STEMM community can work toward dismantling the barriers and inequities rooted in gendered stereotyping, thereby fostering an environment where all aspiring professionals can thrive based on merit, rather than gender-based biases.

Data availability

The author reports that the data is stored on a password protected institutional research drive, only accessed by him and the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee.

References

Abdul Majid MA, Othman M, Mohamad SF, Lim S, Yusof A (2017) Piloting for interviews in qualitative research: operationalization and lessons learnt. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 7(4):1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i4/2916

Aguillon SM, Siegmund G, Petipas RH, Drake AG, Cotner S, Ballen CJ (2020) Gender differences in student participation in an active-learning classroom. Life Sci Educ 19(2):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-03-0048

Aidy CL, Steele JR, Williams A, Lipman C, Wong O, Mastragostino E (2021) Examining adolescent daughters’ and their parents’ academic-gender stereotypes: predicting academic attitudes, ability, and STEM intentions. J Adolesc 93:90–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.09.010

Andrade C (2021) The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian J Psychol Med 43(1):86–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620977000

Beck M, Cadwell J, Kern A, Wu K, Dickerson M, Howard M (2022) Critical feminist analysis of STEM mentoring programs: a meta-synthesis of the existing literature. Gend Work Organ 29:167–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12729

Berger J, Wagner DG (2007) Expectation states theory.. In: Ritzer G (ed) Blackwell encyclopaedia of sociology. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405165518.wbeose084.pub2

Blackburn H (2017) The status of women in STEM in higher education: a review of literature 2007-2017. Sci Technol Libr 36(3):235–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2017.1371658

Blaique L, Pinnington A, Aldabbas H (2023) Mentoring and coping self-efficacy as predictors of affective occupational commitment for women in STEM. Pers Rev 52(3):592–615. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2020-0729

Blickenstaff JC (2005) Women and science careers: leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gend Educ 17(4):369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250500145072

Bloodhart B, Balgopal M, Casper AA, McMeeking LB, Fischer EV, DaBaets AM (2020) Outperforming yet undervalued: undergraduate women in STEM. PLoS One 15(6):e0234685. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234685

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun V, Clarke V (2019) Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 11(4):589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns Psychother Res 21(1):37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

Brownhill S, Oates R (2017) Who do you want me to be? An exploration of female and male perceptions of ‘imposed’ gender roles in the early years. Education 3–13 Int J Early Years Educ 45(5):658–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1164215

Catalyst (2021) Women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) (quick take). https://www.catalyst.org/research/women-in-science-technology-engineering-and-mathematics-stem/

Christiaensen L (2001) The qual-quant debate within its epistemological context: some practical implications. In: A workshop held at Cornell University March 15–16, 2001, p 70. http://publications.dyson.cornell.edu/research/researchpdf/wp/2001/Cornell_Dyson_wp0105.pdf#page=77

Cohen SM, Hazari Z, Mahadeo J, Sonnert G, Sadler PM (2021) Examining the effect of early STEM experiences as a form of STEM capital and identity capital on STEM identity: a gender study. Sci Educ 105:1126–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21670

Cole K, Hassel H (2017) Surviving sexism in academia: strategies for feminist leadership. Taylor & Francis

Dekelaita-Mullet DR, Rinn AN, Kettler T (2021) Catalysts of women’s success in academic STEM: a feminist poststructural discourse analysis. J Int Women’s Stud 22(1):83–103. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol22/iss1/5

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (2019) Advancing women in STEM strategy: women in STEM at a glance. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/advancing-women-in-stem-strategy/snapshot-of-disparity-in-stem/women-in-stem-at-a-glance

Dorph R, Bathgate ME, Schunn CD, Cannady MA (2018) When I grow up: the relationship of science learning activation to STEM career preferences. Int J Sci Educ 40(9):1034–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2017.1360532

Eagly AH, Wood W (2012) Social role theory. In: Van Lange P, Kruglanski A, Higgins ET (eds) Handbook of theories of social psychology. Sage Publications Ltd, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp 458–476. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n49