Abstract

Racism has been a central element in the history of Major League Baseball. And yet, there is an incredibly rich history of African American baseball in the United States encompassing the Negro Leagues and the celebrated era when rigid racial exclusions from Major League Baseball finally fell giving way in quick succession to the transformative arrival of Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays and Henry Aaron. African American participation on Major League Baseball rosters grew steadily in the decades after Jackie Robinson’s debut, but African American representation in Major League Baseball has precipitously declined in recent years. Within that context, this study explores whether African Americans have been subject to disparate treatment in the Major League Baseball draft. An analysis of more than 9000 selections in the Major League Baseball draft from 1965 to 2001 reveals a significant disparity based on race. Relative to White players, African American players were undervalued in the draft. This disparity is not rooted in the drafts of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Instead, major league teams began significantly undervaluing African American prospects in the 1990s. The implications of this pattern are particularly notable given baseball’s recent decision to shrink the draft to 20 rounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The history of Major League Baseball in the United States cannot be told without reference to racism. Major League Baseball enforced a rigid, though unwritten, rule against African American players that persisted from 1885 through Jackie Robinson’s debut in 1947 (Hylton 1997).

And yet, there is an incredibly rich history of African American baseball in the United States that includes a period when some of the greatest to ever play the game—the likes of Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige, and James “Cool Papa” Bell—competed in the Negro Leagues (Bobick 2019) and a dramatic roughly five-year span when total exclusion of African Americans from Major League Baseball gave way to the celebrated era where African Americans including Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, and Henry Aaron revolutionized the game.

In the decades that followed, African American participation on Major League Baseball rosters expanded, reaching a high of almost 19 percent in 1981 (Armour and Levitt 2017). Since then, however, the number of African American players in Major League Baseball shrank to less than 7 percent of Major League rosters (Svrluga 2022). These numbers pale in comparison to the representation of African Americans in other professional sports in the United States.Footnote 1 Major League Baseball’s 2022 World Series featured zero African American players, an absence not seen since 1950 (Svrluga 2022).Footnote 2

Various theories have been advanced to explain the declining representation of African American players in the major leagues, pointing the finger at societal inclinations (declining interest in the game), economic exclusion (the high cost of playing youth baseball), and racial bias (stereotypes in the player evaluation process). Here I use data from Major League Baseball drafts occurring between 1965 and 2001 to analyze whether there is a racial disparity in how players are selected. Analysis of draft results, in which the precise value organizations place on a player and the precise output that player produces are known, provide particularly compelling evidence in the ongoing debate that spans the sports industry (Goddard and Wilson 2009) as well as business in general (McKay et al. 2008) regarding whether bias and stereotypes can be toppled by a bottom-line, results-oriented mentality.

The major league baseball draft

While major league baseball teams are certainly more likely to draft players who will go on to success in the big leagues in the early rounds of the baseball draft than in the later rounds (Crotin, et al. 2022), the baseball draft, more than other professional sports drafts, is nonetheless defined by inefficiency.Footnote 3 That is, despite the best efforts of general managers and scouts, the relationship between when a player is selected and their overall career success is relatively small (Koz et al. 2012). Moreover, while particular organizations may have an unusually productive draft from time to time, research fails to find evidence of sustained drafting superiority by any organization (Spurr 2000).

Fueled in part by how hard it is to analyze baseball prospects and the sizable proportion of drafted players who never progress through the minor leagues and into the major leagues, the Major League Baseball draft has always been far longer than drafts in other professional leagues. The modern NBA draft is two rounds long. The modern NFL draft lasts for seven rounds. Major League Baseball, until both the draft and the organization of baseball’s minor leagues were revised in 2020, had a draft that lasted 40 rounds. Beginning in 2021, the Major League Baseball draft became 20 rounds long, still almost three times longer than the NFL draft despite NFL rosters being twice the size of MLB rosters.

Player selection is not only a matter of talent evaluation, of course, but also of strategy. Should a team select a player they are confident will make a modest contribution in the major leagues or a player a team believes has a small chance to be a great player and considerable chance to not to make it at all? Barden and Choi (2021) find that the best and worst teams are more likely to accept the high risk/high reward scenario, while mediocre teams tend toward safer picks.

Moreover, the scouting and evaluation of talent is subject to an array of rather arbitrary forces. Whitaker (2013), for example, noted that the teammates of star amateur players are more likely to be drafted because the presence of a star attracts more scouts, and thus provides all players on an amateur team more opportunity to impress major league evaluators. Herring et al. (2021), meanwhile, document scouts’ preference for players born in certain months of the year.

Today, the typical player drafted by a major league team has college playing experience (McCue et al. 2019). The draft has grown increasingly oriented around college players (Staudohar et al. 2006; Burger and Walters 2009; Spurr 2000) for a variety of reasons including teams’ interest in acquiring players who might advance to the major leagues faster and teams’ belief that they can more successfully evaluate prospective players with college experience because of their additional years of playing against higher level competition (Roach 2022). Nonetheless, about 1 in 4 players sign their first contract straight out of high school. Some critics contend the increasing tendency toward drafting college players has become a source of inefficiency, with teams undervaluing high school talent (Sims and Addona 2016; Caporale and Collier 2013).

While sports drafts are superficially a means to fairly distribute incoming talent, scholars point out that the chief effect of a draft is to restrain employer costs because a drafted player has no ability to offer his services to a higher bidder (Deming 2011). In fact, a Major League Baseball team’s contract offer is rooted in explicit league guidelines meant to constrain leaguewide spending on prospects (Deming 2011).

The decision whether to sign a contract is a fraught one for high school prospects, as players must consider the value and opportunity costs of signing to play in the minor leagues versus playing college baseball. Pifer et al.’ (2020) analysis suggests high school players drafted after roughly the fourth round are better off refusing the typically paltry contracts they are offered and instead playing in college (See also, Winfree and Molitor 2007). Further complicating the matter, NCAA rules effectively prohibit current or future college players from hiring an agent or lawyer to help them negotiate or evaluate their draft situation without voiding their college eligibility (Karcher 2004). Players and their families are thus left without the benefit of an experienced advocate as they evaluate, project, and decide their economic and educational future.

Baseball and race

By the time the draft was instituted in 1965, baseball’s total exclusion of African Americans was nearly two decades in the past. African American prospects were among the star attractions of early drafts, including the future Hall of Famer and renowned “Mr. October” Reggie Jackson, who was selected in 1966 with the second pick of the second draft.

But the past history of baseball was powerfully shaped by the unwritten rule that kept luminaries like Josh Gibson and countless others from claiming their rightful place in the major leagues. Until Jackie Robinson made his debut in 1947, Major League Baseball had gone six decades without a single African American player. Even as the presence of African American players was associated with team success (Hanssen 1998), many major league owners continued to practice racial exclusion in subsequent seasons, with the Boston Red Sox remaining all-White until 1959 (Weir 2014). And, as the game integrated, discriminatory behavior remained pervasive. In the first ten seasons Robinson played, Kanago and Surdam (2020) found Robinson and his African American peers were hit by 86% more pitches than the average White player.

As outright exclusion fell by the wayside, disparities and irregularities continued to arise. Disproportionately few African Americans played the position of catcher, for example, a disparity that persisted for decades (Phillips 1983).

Studies considering the effect of race on baseball careers in the modern era come to mixed conclusions. Bellemore (2001) finds evidence of racial bias in the decision to promote players to the major leagues, with African American players progressing to the majors from the minor leagues at a slower rate than White players with comparable statistics. On the other hand, Groothuis and Hill (2008) do not find evidence of exit discrimination—that is, major league careers end on comparable levels of offensive productivity regardless of race.

Studies have found some evidence of bias in Hall of Fame voting such that African American players have received less support than their statistics would otherwise suggest (Desser et al. 1999; Jewell et al. 2002). While these effects have not represented the margin by which anyone has been kept from induction, it is nonetheless troubling that any player would lose the support of even one Hall of Fame voter on account of race.Footnote 4

Race and the path to baseball

To the extent researchers have considered how race affects the path to professional baseball, their focus has been on structural effects rather than social factors. Bailey and Shepherd (2011) note that international players are not subject to the draft and thus able to bargain as free agents with the team(s) of their choice. International players are also able to sign at age 16, allowing major league teams to subsidize their development at an age when their American equivalents would be expending significant resources to play high level amateur baseball.Footnote 5 Bailey and Shepherd (2011) argue this disparity is particularly detrimental to prospective African American players, who would have greater opportunity to develop their game and be rewarded for their success if they were from San Pedro De Macoris rather than San Diego. Similarly, Ross and James (2015) call for Major League Baseball to invest in low-income baseball prosects to address the racially discriminatory effects of the draft. Others have similarly concluded that barriers to monetizing talent have reduced the supply of prospective African American ballplayers. Standen (2014) contrasts the treatment of top-level prospective golfers, who can effectively sell shares in their future professional earnings to finance their development, with top level prospective baseball players, who must endure ongoing participation costs without subsidy.

Baseball scouts also assert that the economics of youth baseball is a major factor in the dearth of African Americans in baseball (Spearman et al. 2017). With the entry costs to participate in basketball considerably lower, baseball suffers by comparison from a certain level of economic exclusion.

Indeed, the path to baseball has been profoundly shaped by privatization and suburbanization. Youth sports have shifted from local, accessible, public leagues common decades ago to regional, exclusive, private endeavors, with so called “travel” baseball teams the modern norm for young developing baseball players (Hyman 2012) and travel participation rates well over-representing whites (Mirehie et al. 2019). Meanwhile, predominantly African American neighborhoods in a bygone era of urban prosperity were much better situated to support budding athletic talent (Hunter et al. 2016) than is the case today following the deindustrialization of cities and disinvestment in public programming (see, for example, Bryant’s [2022] discussion of baseball in Oakland). Consequently, youth baseball has become a game increasingly centered in white, suburban and rural outposts (Ogden and Hilt 2003).

Beyond economics, Ogden and Rose (2005) point to a cultural deficit in which young African Americans identify more with the game of basketball and famous basketball players than they do with the game of baseball and famous baseball players. Gallup data reveals that baseball was the favorite sport of Americans through the mid-1960s before falling to second behind football. Baseball continues to rank second to football among white and Hispanic Americans—but is a distant third behind football and basketball among African Americans.Footnote 6

Some scouts nevertheless believe there is considerable young African American baseball talent that is going undiscovered, and believe their own peers have contributed to the underrepresentation of African Americans in professional baseball (Spearman et al. 2017). They criticize not the intent of their colleagues but the ingrained habits that narrow the attention of their peers and leave them uninformed regarding potential African American prospects.

Research on bias in hiring—not only in sports but in any industry—is informed by two core premises. One, when selecting talent, people have a tendency to follow subconscious preferences for those who look like themselves (ingroup bias) or look like those who predominate in the profession (distribution effect), resulting in persistent racial bias across industries (Quillian and Midtboen 2021). Two, when a person expects to be held accountable for the outcomes of their hiring decisions, they have a motivation to overcome obstacles, even their own biases, in pursuit of successful candidates who will reflect positively on themselves (Ford, et al. 2004). Research in the first tradition implies that a baseball evaluation structure largely made up of White men, evaluating prospective talent in an occupation largely made up of White men, will likely perpetuate biased decisions. Research in the second tradition, however, implies that the desire to succeed will effectively stifle biased impulses.

Data and methods

To examine the effect of race on player selection, data from a stratified sample of Major League Baseball drafts between the years 1965 and 2001 was collected.Footnote 7 The year 1965 represents the first major league draft and 2001 serves as a cutoff date to provide an opportunity to assess each player’s full career results.Footnote 8

For each draft under study, research assistants accessed baseball-reference.com and then recorded data on each pick, including the name, the round and pick number, the position, and various playing statistics including the highest level of baseball reached, number of games played in the majors, and each player’s career major league WAR value.

The WAR metric estimates each individual player’s contribution to his team’s success relative to the expected production of an average replacement level player at the same position. It can be applied to any position and is calculated against league productivity at the time. Through the 2023 season, among players with the ten highest all-time WAR career value scores are baseball luminaries Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, Willie Mays, Ty Cobb, and Henry Aaron. Players can accumulate a negative score for WAR for playing at a level below the average expected replacement. This is most typically achieved in short major league careers. However, some players, have compiled negative WAR over the long haul, including former Reds and Mets second baseman Doug Flynn who was able to achieve a -6.9 WAR (because of his offensive limitations, including a career 0.266 on base percentage and 20 caught stealing outcomes out of 40 stolen base attempts) over a career that endured for more than 1,300 games. Players who did not reach the majors have a WAR of zero.

Determining the race of each player selected followed a multi-step process. Research assistants began by scouring player profiles, team biographies and team photos from professional and collegiate teams, as well as news coverage. If none of those sources yielded a photo of the player, social media sites were consulted. In the minority of cases in which research assistants were unable to find a photo of the player using any of these sources, race was imputed by applying U.S. Census data to the player’s name (using the portal available through www.namsor.com).

Results

If race is unrelated to the way baseball evaluates players, we would expect to find no distinction based on race in when players are selected or how successful they become. This proves not to be the case.

Table 1 shows the average WAR career score for all White players drafted was 1.05. The average WAR for all African American players was 1.74. This difference is statistically significant (p > 0.01, T-test). Notably, those White players were selected, on average, about two rounds earlier than the average African American player. That is, the average White player was drafted higher and went on to less career success than the average African American player.

Of course, WAR is hardly the only way to measure the success of a player’s career. However, alternate ways of measuring draft pick success all point to a higher level of collective success for the African American players drafted than the White players. With regard to reaching the majors, a higher percentage of African American players picked (23%) than White players (18.5%) played in the majors (p < 0.01, Chi-Square). Expanding our criteria to those at least reaching the highest level of minor league baseball (Triple A), 42% of African American players selected went on to at least reach Triple A. Among White players, 30.9% reached Triple A (p < 0.01, Chi-Square). Among position players, the African Americans drafted played in an average of 151 major league games while their White counterparts played in 55 (p < 0.01, T-test). Among pitchers, the African Americans drafted pitched in an average of 18 major league games, while their White counterparts pitched in 10 (p < 0.01, T-test).

An ongoing imbalance in the ability to evaluate and select African American prospects would not account for an evolving decline in African American major leaguers of course. Separating out the data by time periods, however, reveals a considerable distinction that suggests disparities in the draft may have contributed to the decline of African Americans in the majors.

Table 2 provides the data on draft results by race for the 1965–1989 drafts. Here, we see the relationship between race and career success evaporates, and the difference between the average overall pick narrows. Counterintuitive though it may be, the data clearly suggest that any imbalance in the ability to fairly evaluate talent without racial bias derives not from the earlier years under study here but from the later ones.

Indeed, Table 3 shows the average WAR for White players selected between 1990 and 2001 was 0.88. The average WAR for African American players selected in those years was 2.05 (p < 0.01, T-test). This gap in career success occurs despite there being no difference based on race in the overall pick number.

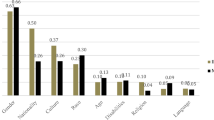

Figure 1 depicts the difference in career WAR between the early period drafts relative to the more recent drafts. While the disparity highlighted in Fig. 1 is by no means the difference between drafting Henry Aaron and Doug Flynn, the emerging imbalance in the post-1990 drafts is nonetheless meaningful. Carl Everett (African American) and Jeromy Burnitz (White), two outfielders drafted in the same round in 1990, both went on to major league careers with a WAR score of about 20. Given the mean career WAR by race, the data suggests that for every player of Everett-level success, major league teams drafted 9 African American players who did not make the majors. For every player of Burnitz-level success, however, baseball drafted 21 White players who did not make the majors.

In a sport where a four to five-year minor league apprenticeship is typical, it is notable that four seasons after the 1990 draft, a sizable drop in African American participation in the major leagues began. From 17.2 percent in 1994, African American participation continued dropping until a new, lower participation plateau of approximately 7 % developed.

One compelling potential explanation for this pattern has less to do with race and more to do with the nature of college baseball. College baseball has a lower rate of African American participation than would be representative of the overall American population or even representative of the population of Major League Baseball players (Butts et al. 2007). Industry observers clearly see this as a potential source of racial disparities in the big leagues. As one American League scout said in 2020, “The percentage of minorities playing college baseball is miniscule, and it’s embarrassing. At a college baseball game, half the time it feels like you’re watching a baseball game in the 1930s” (quoted in Speier 2020).

If major league teams shifted their attention toward college players in recent decades for various strategic reasons, it could have implications for racial representation even if the tactic had nothing to do with race. If college baseball explains the racial draft pattern, we should expect to see that the racial disparity seen in Tables 1 and 3 does not apply to players drafted out of high school.

What we see instead in the high school data (Tables 4, 5, 6), is largely a repeat of the pattern observed among all draft picks. Examining all years under study, there is again a disparity in career success (White players WAR = 1.08; African American players WAR = 1.88; p < 0.01, T-test). Examining 1965–1989, we see once again no collective under-valuing of African American players. Examining 1990–2001, we once again find a sizable disparity that suggests African American players were undervalued (Whites WAR = 1.08; African American WAR = 2.63; p < 0.01, T-test). The presence of this racial disparity in the selection of high school players suggests that whatever accounts for bias and inefficiency in the drafting process, it is not rooted in the shifting tendency toward prioritizing college playing experience.

Research documents a tendency to see those with characteristics that are more typical in an occupation as more suitable for that occupation (He et al. 2019; Grappendorf et al. 2011; Dupree et al. 2021). Dupree et al. (2021) find such occupational patterns productive of bias, hierarchy-maintaining practices, and meritocracy beliefs. In other words, people believe in the dominance of a dominant group, and see that belief not as bias but as a sound judgment rooted in merit.

A review of more than 70,000 scouting reports filed with the Cincinnati Reds organization between 1991 and 2003 indeed found evidence of racial bias in player evaluation (Speier 2020). White players were more apt to be lauded as being leaders and competitive. African American and other players of color were more often described as “raw” and “unpolished.”

One American League team conducted an internal study on how race influenced the organization’s evaluation of talent (Speier 2020). It found the vast majority of players lauded for intangible qualities were White. Meanwhile, African American players were more than 5 times more likely to be called “careless” in scouting reports than White players. An executive with the team explained the dynamic: “We’re talking through a player, a White kid at Duke, and no one says a peep. When there’s a Black high school kid, someone asks, ‘What do we know about the makeup of this guy?’ Just the mere assumption that that’s a question is an inherent bias in my mind.”

While not an explanation for how African Americans began to lose their place in the majors, this distribution bias effect provides a strong theoretical basis for understanding how bias can take hold and strengthen its grip as the African American participation rate falls.

In a larger sense, the data suggest the effects of structural racism (for example, Bonilla-Silva 2006). People in a position of unchallenged power, in circumstances beset by racial imbalance tend to be quite effective perpetuators of that imbalance. Baseball is a sport where ownership is overwhelmingly white. Front office staff is overwhelmingly white. Feinstein (2021) details a long history of barriers to African Americans taking positions of authority as general managers and field managers that persist to the present day, for example.

The premise that the will to win would squeeze bias out of the evaluation process (Ford, et al. 2004) is obviously not in evidence here. Of course, such a scenario depends on evaluators being able to identify bias in the evaluation process and wanting to counteract it. The data here offer chilling evidence that even in a field where hiring success is quantifiable and hiring failures are consequential, hiring bias nonetheless appears endemic.

Shortening the draft

The undervaluing of African American players has significant implications for African American participation in the Major Leagues. If African Americans are systematically being drafted in later rounds than their talent warrants, it reduces their compensation, their likelihood of signing, and hampers the progress through the minor leagues of those who do sign (Bellemore 2001). Perhaps even more notable are the implications given the recent decision by Major League Baseball to shorten the draft to 20 rounds. (Before the change, recent drafts were typically about 40 rounds long).

In the drafts studied here, 10.8 percent of White players who made the major leagues had been drafted after the 20th round. Consistent with the disparity in valuing African American players, however, 17.3 percent of African American players who made the major leagues were drafted after the 20th round. Given those proportions, shrinking the draft will likely further reduce African American participation in Major League Baseball. Indeed, removing players from the major league pipeline in those proportions would alter the racial ratio of Major League Baseball from 9 White players for every 1 African American to 10 White players for every 1 African American.

Conclusion

This study explores whether African American players were treated equitably in Major League Baseball drafts from 1965 to 2001. The answer, in short, is no.

Overall, African American players were drafted in later rounds and went on to more career success than White players. Dividing the time under study into pre- and post-1990 drafts reveals that this racial disparity is a product of the later time period. From 1965 to 1989, White and African American players were treated equitably. From 1990 to 2001, however, a pronounced difference appears, such that African American players were being undervalued relative to White players when their career success is considered.

This pattern has important implications for our understanding of hiring bias. Some research has found that motivated entities can reduce or eliminate bias from their processes (Ford, et al. 2004). Here, despite the presumed motivation to win, Major League teams nonetheless perpetuated racial disparities in talent evaluation. Moreover, racial disparities in the draft developed in tandem with the diminishing role of African Americans on major league rosters.

Ultimately, it is only through recognizing biased processes that the roots of bias can be recognized and addressed. Former Pittsburgh Pirates general manager Neal Huntington saw racial bias in his organization and lamented his own vulnerability to bias. “I probably have said some of those things over the years, defaulting to the ‘little White gamer,’ the ‘grinder,’ the ‘overachiever.’ It’s easy to fall into positive and negative stereotypes and it’s easy to perpetuate those if you’re not conscious of it and aware of it," Huntington said (quoted in Speier 2020). “The archaic, racist stereotype does not have a place,” Huntington declared. “We need to work to be better than that.” Indeed, the data suggest there is much work to be done.

Data availability

The data will be accessible in the Harvard Dataverse upon publication of the article (searchable by article title).

Code availability

The data was analyzed with SPSS. Information on the variables will be attached to the downloadable data.

Notes

On the opening day of the 2023 Major League Baseball season, African Americans comprised 6.1% of roster spots (Nightengale 2023). That was the lowest percentage since 1955, when Jackie Robinson was still playing. While shrinking as a percentage of MLB players, African Americans have consistently held the majority of roster slots in the National Football League and National Basketball Association in recent decades. Currently, 56% of NFL players and 72% of NBA players are African American (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1154691/nfl-racial-diversity/).

There were a total of 12 African Americans in Major League Baseball in 1950. The majority played for one of two teams (Brooklyn Dodgers and Cleveland Indians).

Niven (2022), for example, finds the correlation between pick number and career value in professional football to be r = .44 over a wide sample of drafts. In the data analyzed here, the correlation between pick number and career value in baseball is only r = .12.

Whether fans discriminate has also been investigated. Various studies of baseball card values, for example, come to divergent conclusions on whether cards of White players are worth more than cards for African American players who had comparable success (Burge and Zillante 2017; Andersen and La Croix 1991; Primm, et al. 2011; Hewitt, et al. 2005).

To be clear, Major League Baseball’s investment in the development of Latin American talent is ultimately grounded in a self-interest (Wasch 2009; Spagnuolo 2003; Marcano and Fidler 2004). By expending often very small sums on individual teenage players, major league teams are able to acquire the future services of those players who continue to develop while casting aside the many more who do not pan out (Regalado 2000). In the process, diverting young men in impoverished circumstances away from continuing their education and toward spending every moment on preparation for baseball (Wasch 2009). Hanlon (2013) raises the specter that Major League Baseball’s exploitative position amounts to a human rights violation. If such a player reaches the major leagues, they would be paid no more than the league minimum salary and have no ability to offer their services to another club for the first several years of their major league career, thus offering teams a potential windfall in salary expenses compared to what they might pay such a player in an open market (Ottenson 2014). Critics have characterized Major League Baseball’s orientation toward Latin America as colonial, exploiting resource disparities and any meaningful local regulation (Ottenson 2014; Gentile 2022). Future work comparing the drafting of Latino players from the U.S. and the signing of Latino players internationally would be invaluable.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/4735/sports.aspx (accessed June 1, 2023).

Drafts from the following years were included in the analysis: 1965, 1966, 1970, 1971, 1975, 1976, 1979, 1981, 1985, 1989, 1990, 1991, 1995, 1996, 1999, 2000, and 2001. All players drafted in the first 20 rounds are included as well as a stratified sample of rounds after the 20th round.

Nonetheless, three players drafted during this period remained active in Major League Baseball at the time of the analysis: Adam Wainwright, Rich Hill and Jesse Chavez. Statistics for these players are complete through the 2023 season.

References

Andersen T, La Croix S (1991) Customer racial discrimination in major league baseball. Econ Inq 29(4):665–677

Armour M, Levitt D (2017) Baseball Demographics. Society for American Baseball Research. https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/baseball-demographics-1947-2016/

Bailey JS, Shepherd G (2011) Baseball’s accidental racism: the draft, African-American players, and the law. Conn l Rev 44:197

Barden J, Choi Y (2021) Swinging for the Fences? Payroll, performance, and risk behavior in the Major League Baseball draft. J Sport Manag 35(6):499–510

Bellemore F (2001) Racial and ethnic employment discrimination: promotion in major league baseball. J Sports Econ 2(4):356–368

Bobick B (2019) Whites, blacks, and the homestead grays. NINE: J Baseball Hist Culture 28(1):153–157

Bonilla-Silva E (2006) Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham

Bryant H (2022) Rickey: the Life and Legend of an American Original. Mariner, Boston

Burge G, Zillante A (2017) Racial discrimination and statistical discrimination: MLB rookie card values and performance uncertainty. Soc Sci Q 98(5):1435–1455

Burger J, Walters S (2009) Uncertain prospects: Rates of return in the baseball draft. J Sports Econ 10(5):485–501

Butts F, Hatfield L, Hatfield L (2007) African-Americans in college baseball. The Sport Journal 10(2) http://www.thesportjournal.org/article/african-americans-in-college-baseball/

Caporale T, Collier T (2013) Scouts versus Stats: the impact of Moneyball on the Major League Baseball draft. Appl Econ 45(15):1983–1990

Crotin R, Conforti C, Szymanski D, Oseguera J (2022) Anthropometric evaluation of first round draft selections in major league baseball. J Strength Cond Res 37(8):1609–1615

Deming N (2011) Drafting a solution: impact of the new salary system on the first-year major league baseball amateur draft. Hastings Comm & Ent LJ 34:427

Desser A, Monks J, Robinson M (1999) Baseball hall of fame voting: a test of the customer discrimination hypothesis. Soc Sci Q 80(3):591–603

Dupree C, Torrez B, Obioha O, Fiske S (2021) Race–status associations: distinct effects of three novel measures among White and Black perceivers. J Pers Soc Psychol 120(3):601–625

Feinstein J (2021) Raise a first, take a knee. Little, Brown, New York

Ford T, Gambino F, Lee H, Mayo E, Ferguson M (2004) The role of accountability in suppressing managers’ preinterview bias against African-American sales job applicants. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 24(2):113–124

Gentile PC (2022) MLB’s Neocolonial Practices in the Dominican Republic Academy System. J Sport Soc Issues 46(3):269–292

Goddard J, Wilson J (2009) Racial discrimination in English professional football: evidence from an empirical analysis of players’ career progression. Camb J Econ 33(2):295–316

Grappendorf H, Henderson A, Burton L, Boyles P (2011) Utilizing role congruity theory to examine the hiring of blacks for entry level sports management. J Study Sports Athl Educ 5(2):201–218

Groothuis P, Hill J (2008) Exit discrimination in major league baseball: 1990–2004. South Econ J 2008:574–590

Hanlon R (2013) School's out forever: The applicability of international human rights law to major league baseball academies in the Dominican Republic. Pac. McGeorge Global Bus. & Dev. LJ 26: 235.

Hanssen A (1998) The cost of discrimination: a study of major league baseball. South Econ J 64(3):603–627

He J, Kang S, Tse K, Toh SM (2019) Stereotypes at work: Occupational stereotypes predict race and gender segregation in the workforce. J Vocat Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103318

Herring C, Beyer K, Fukuda D (2021) Relative age effects as evidence of selection bias in major league baseball draftees (2013–2018). J Strength Cond Res 35(3):644–651

Hewitt J, Muñoz R, Oliver W, Regoli R (2005) Race, performance, and baseball card values. J Sport Soc Issues 29(4):411–425

Hunter MA, Pattillo M, Robinson Z, Taylor KY (2016) Black placemaking: celebration, play, and poetry. Theory Cult Soc 33(7–8):31–56

Hylton JG (1997) American civil rights laws and the legacy of Jackie Robinson. Marq Sports LJ 8:387

Hyman M (2012) The most expensive game in town: the rising cost of youth sports and the toll on today’s families. Beacon Press, Boston

Jewell RT, Brown R, Miles S (2002) Measuring discrimination in major league baseball: evidence from the baseball hall of fame. Appl Econ 34(2):167–177

Kanago B, Surdam DG (2020) Intimidation, discrimination, and retaliation: Hit-by-pitches during the integration of Major League Baseball. Atl Econ J 48(1):67–85

Karcher R (2004) The NCAA’s regulations related to the use of agents in the sport of baseball: are the rules detrimental to the best Interest of the Amateur Athlete. Vand J Ent l & Prac 7:215

Koz D, Fraser-Thomas J, Baker J (2012) Accuracy of professional sports drafts in predicting career potential. Scand J Med Sci Sports 22(4):64–69

Marcano A, Fidler D (2004) Baseball’s Exploitation Of Latin Talent. NACLA Rep Am 37(5):14–18

McCue M, Baker J, Lemez S, Wattie N (2019) Getting to first base: developmental trajectories of major league baseball players. Front Psychol 10:2563

McKay P, Avery D, Morris M (2008) Mean racial-ethnic differences in employee sales performance: the moderating role of diversity climate. Pers Psychol 61(2):349–374

Mirehie M, Gibson H, Kang S, Bell H (2019) Parental insights from three elite-level youth sports: implications for family life. World Leisure Journal 61(2):98–112

Nightengale B (2023) MLB’s Percent of Black Players is the Lowest since 1955. USA TODAY, April 14.

Niven D (2022) Stereotypes versus self-interest: race and the NFL draft. SN Soc Sci 2(97):1–13

Ogden D, Hilt M (2003) Collective identity and basketball: An explanation for the decreasing number of African-Americans on America’s baseball diamonds. J Leis Res 35(2):213–227

Ogden D, Rose R (2005) Using Giddens’s structuration theory to examine the waning participation of African Americans in baseball. J Black Stud 35(4):225–245

Ottenson E (2014) The social cost of baseball: addressing the effects of major league baseball recruitment in Latin America and the Caribbean. Wash u Global Stud l Rev 13:767

Phillips J (1983) Race and career opportunities in major league baseball: 1960–1980. J Sport Soc Issues 7(2):1–17

Pifer ND, McLeod C, Travis W, Castleberry C (2020) Who should sign a professional baseball contract? Quantifying the financial opportunity costs of major league draftees. J Sports Econ 21(7):746–780

Primm E, Piquero NL, Piquero A, Regoli R (2011) Investigating customer racial discrimination in the secondary baseball card market. Sociol Inq 81(1):110–132

Quillian L, Midtbøen A (2021) Comparative perspectives on racial discrimination in hiring: the rise of field experiments. Ann Rev Sociol 47:391–415

Regalado S (2000) Latin players on the cheap: professional baseball recruitment in Latin America and the neocolonialist tradition. Ind J Global Legal Stud 8(1):9–20

Roach M (2022) Career concerns and personnel investment in the major league baseball player draft. Econ Inq 60(1):413–426

Ross S, James M (2015) A strategic legal challenge to the unforeseen anticompetitive and racially discriminatory effects of Baseball’s North American draft. Colum l Rev Sidebar 115:127

Sims J, Addona V (2016) Hurdle models and age effects in the major league baseball draft. J Sports Econ 17(7):672–687

Spagnuolo D (2003) Swinging for the fence: a call for institutional reform as Dominican boys risk their futures for a chance in Major League Baseball. U Pa J Int’l Econ l 24:263

Spearman L, Norwood D, Amos M (2017) The thrill is gone: scouts’ perspectives on The Decline of African Americans in major league baseball. J Sport Behav 40(2):204

Speier A (2020) How racial bias can seep into baseball scouting reports. Boston Globe, June 10.

Spurr S (2000) The baseball draft: A study of the ability to find talent. J Sports Econ 1(1):66–85

Standen J (2014) The Demise of the African American Baseball Player. Lewis & Clark l Rev 18:421

Staudohar P, Lowenthal F, Lima A (2006) The evolution of baseball’s amateur draft. NINE: J Baseball Hist Cult 15(1):27–44

Svrluga B. (2022) At this World Series, the National Pastime Doesn’t Look like the Nation. Washington Post, November 1.

Wasch A (2009) Children left behind: the effect of major league baseball on education in the Dominican republic. Tex Rev Ent & Sports l 11:99

Weir R (2014) Constructing Legends: pumpsie green, race, and the Boston red sox. Hist J Mass 42(2):48

Whitaker K (2013) Does a ‘coattail effect’ influence the valuation of players in the Major League Baseball draft? https://www.whitakk.com/551a3f18ee846ef94682cb5d61e4cee5/Kevin_Whitaker_SSAC_2013.pdf

Winfree J, Molitor C (2007) The value of college: drafted high school baseball players. J Sports Econ 8(4):378–393

Acknowledgements

My thanks to David Berri for feedback on the research, and to Ann Bennett and Jason Murray for their research assistance. Student research assistants were funded by the Discover Program of the University of Cincinnati Honors Program.

Funding

Student research assistants were funded by the Discover Program of the University of Cincinnati Honors Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This is a work of one author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was not necessary because the data utilized here are publicly available.

Consent to participate

The findings here derive from publicly available data on prominent individuals. Consent is therefore not applicable.

Consent for publication

The findings here derive from publicly available data on prominent individuals. Consent is therefore not applicable.

Commitment to publication

The author is committed to publish in SN Social Sciences if the paper is accepted.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niven, D. The racial disparity in the Major League Baseball draft, 1965–2001. SN Soc Sci 4, 14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00825-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00825-1