Abstract

Intimate partner violence is a pervasive global human rights issue that has prompted the establishment of various international charters and national-level comprehensive legislative measures to combat this problem effectively. To attain success, it is also imperative to contextualize intimate partner violence within its underlying precursors and address them systematically and methodically. In this article, we focus on two obstacles hindering the effort of policymakers to eradicate intimate partner violence in Ghana: wife beating justification and restricted access to permanent or temporary shelters for victims. The aim is to investigate the correlation between these two indicators to determine if empowerment in property ownership can influence and unseat the belief that wife beating is justified. Leveraging data from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, we utilized a comprehensive theoretical approach by integrating normalization, social learning, resource, and gendered resource theories. Subsequently, we estimated a stepwise logistic regression, which revealed that while a higher proportion of women justified wife beating than men, empowering women with landed properties (arable or otherwise) significantly reduced the odds of justifying wife beating. However, among the men, a different pattern was observed. The findings presented in this article emphasize the protective nature of property ownership and stress the significance of improving women’s access to property. This enhancement aims not only to support livelihoods but also to diminish the inclination to justify wife beating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women, which have led to domination over and discrimination against women by men and to the prevention of the total advancement of women (Sohini 2016). IPV is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon deeply intertwined with gender-based power relations, sexuality, self-identity, and social institute. It remains a significant global concern, gaining recognition within international policy initiatives, the most recent being its integration into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (WHO 2021). Like other countries, Ghana grapples with the widespread problem of IPV despite her commitment to various initiatives to create a violence-free environment. Approximately 28% of women (1 in 3) and 20% of men in Ghana have experienced partnered violence (Institute of Development Studies et al. 2016). Intimate partner violence has several unintended consequences, including depression, gynecological problems, substance abuse, chronic mental illness, and physical injuries (Scoglio et al. 2023). In response to the adverse effects and violation of fundamental human rights caused by IPV, Ghana’s parliament sanctioned the Domestic Violence Act (Act 732) in 2007. This legislation was part of a broader initiative to combat IPV, prohibit sex-based discrimination, and criminalize some harmful cultural practices.

While significant legislative efforts have been made to combat IPV, there are documented barriers that hinder victims’ exit from abusive relationships, impeding further progress in these initiatives. Two primary hurdles stand out in Ghanaian literature. The first is the prevailing individual/societal attitudes towards wife beating justification, and the second is the scarcity of permanent and temporary shelters for victims (Adu-Gyamfi 2014; Dickson et al. 2020; Institute of Development Studies et al. 2016). These two barriers are significant indicators of diminished empowerment, prompting policy initiatives to establish diverse avenues to empower victims (Gahramanov et al. 2022; Oduro et al. 2015; Peterman et al. 2017). The concept of social acceptability highlights the influence of others on an individual’s perception of their behavior. When an individual resides in a community with strong acceptance of IPV, they are more likely to adopt and define such behavior for themselves. According to the theory of social justification of IPV, if a higher proportion of the general population in a community believes that IPV is justifiable, potential perpetrators are more inclined to think they have the right to engage in violence if circumstances warrant it (Waltermaurer 2012; Waltermaurer et al. 2013). Gender norms are learned through socialization as individuals transition from childhood to adulthood (Vu et al. 2017).

Consequently, the development of inequitable gender attitudes, including the justification of wife beating, can be traced to early adolescence. Individuals with such exposures subsequently become victims or perpetrators of IPV (Kadengye et al. 2023; Kemigisha et al. 2018; Vu et al. 2017). Despite the intergenerational transmission of IPV, individuals exposed to abuse exhibit variations in their interpersonal relationships, so not everyone exposed to violence experiences later abuse or becomes abusive. Nonetheless, addressing this barrier necessitates a comprehensive shift in societal/individual attitudes that justify physical violence, considering its significant role as a primary predictor of IPV perpetration and victimization (Dickson et al. 2020; Kadengye et al. 2023; Krause et al. 2016).

Extant literature has consistently advocated for economic empowerment due to its ability to improve outcomes, reduce domestic violence, and improve socio-economic status (Gahramanov et al. 2021; Jose and Younas 2022; Koppelman 2022). In response to making higher bargaining power available to victims of IPV, researchers have examined how women’s access to economic resources through employment and cash transfers addresses their exit options (Hidrobo et al. 2016). However, there has been a lack of studies investigating the impact of property ownership on IPV justification and perpetuation, given that it presents a visible indicator of a woman’s fallback position and a tangible exit strategy from unfavorable situations. According to Seedat and Rondon (2021), most working women are involved in unpaid work, and their earnings often fall short of suitable housing. Even if they can find a rental property, they face social barriers as property owners in many developing countries hesitate to lease to single women (Hulley et al. 2023). Owning a house offers immediate and secure shelter. Similarly, owning agricultural land provides various opportunities for women’s livelihood, such as establishing microenterprises, cultivating the land, renting it out, or constructing shelters for themselves (Boudreaux 2018; Oduro et al. 2015). Unlike most shock-specific safety nets, which are mostly short-term and temporary, providing women access to long-term assets empowers them to challenge cultural and social norms associated with gender roles.

In this paper, we explore whether empowerment in landed property (arable or otherwise) can unseat and challenge attitudes that justify physical violence, utilizing nationally representative data from the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS). Essentially, we seek to understand whether the justification of wife beating is deeply ingrained or is influenced by the lack of empowerment in landed properties. While we acknowledge that attitudinal measures may have limitations due to their dynamic nature, they offer valuable insights into the prevalence of IPV in Ghana and warrant an investigation.

Literature review

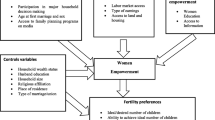

To offer a sound and scholarly account, our study presents a comprehensive framework that harmonizes the normalization, social learning, resource, and gendered resource theories to explain wife beating justification and its associated factors. The enduring prevalence of wife beating can be attributed to its gradual assimilation into everyday life, resulting in its normalization. The normalization theory offers insights into the misconception by describing the gradual shifts in boundaries, a reinterpretation of what constitutes IPV, and the victim’s acceptance of the abuse inflicted as deserved (Lundgren et al. 2001). Defining violence among women takes on a different meaning when considering their experiences. This process continues until it becomes systematic, validating and reinforcing the newly assumed meaning through normalization. The normalization of wife beating is further enforced as it is passed down from generation to generation. Eventually, it becomes a learned behavior. This phenomenon is explained by Bandura’s Social Learning theory, which suggests that individuals acquire behaviors by observing and imitating their role models (Bandura 1977). The learning process involves self-discovery through observing, retaining, and reproducing beliefs and instructions on living. It integrates cognitive and behavioral aspects, where the individual’s environment, behavior, and cognitive processes interact synergistically (Smith 2012). Consequently, exposing children to violence as victims or witnesses predisposes them to imitate violent acts, considered "normal" and socially acceptable behavior.

Wife beating occurs within the confines of the home/family, where power dynamics are often established through force or threat of force. This gave rise to the resource theory proposed by Goode (1971), which argues that when there is a perceived imbalance or scarcity of crucial economic or material resources, violence becomes a means for men (with violent predispositions) to assert power, control, or express their frustration. (Linos et al. 2013; Waltermaurer 2012). Furthermore, the theory suggests that women’s access to economic resources can alter their level of dependency in a relationship, thereby reducing men's dominance over women within the domestic space. The power imbalance suggested by the resource theory finds its roots in specific gender roles prevalent in societies. The resource theory, which provides structural explanations, assumes that all men are traditional. The gendered resource theory addresses this limitation by incorporating gender ideologies into its predictions (Atkinson et al. 2005). These gender ideologies encompass a spectrum ranging from traditional roles, where husbands are seen as breadwinners and women as housewives, to more egalitarian roles. Essentially, the impact of resources on spousal violence is influenced by the man’s gender ideologies. This implies that if the wife’s resources challenge his desired role as the family’s breadwinner, he may resort to violence to regain dominance. The gendered resource theory demonstrates how the interplay between culture and structure shapes the social environment, which, in turn, facilitates the construction of alternative forms of masculinity (Atkinson et al. 2005).

Drawing from economic theories of intrahousehold bargaining, the hypothesized association between women’s property ownership and IPV lacks a definite conclusion (Peterman et al. 2017). On the one hand, women’s asset ownership indicates economic independence or a credible deterrent that empowers them to resist IPV or escape abusive situations. Conversely, in societies where men’s dominance is characterized by ownership of assets, women’s property ownership can challenge established gender norms and prompt partners with violent predispositions to assert control through perpetrating acts of violence. In their seminal study on IPV, human development, and property ownership, Panda and Agarwal (2005) highlighted the violence-reducing capacity of property ownership and how it enhances one’s well-being and agency among Indian women. Bhattacharyya et al. (2011) confirmed the protective nature of home ownership against lifetime physical spousal violence for women in Uttar Pradesh, India. A subsequent study by Kelkar et al. (2020) in three Indian states concluded that women’s sole land ownership was associated with decreased partnered violence, contributing to their economic empowerment and increased agency. Oduro et al. (2015) observed that a woman’s share in financial and physical assets was associated with lower emotional IPV in Ghana and lower physical violence in Ecuador. Gahramanov et al. (2022) disaggregated the forms of ownership and concluded no association exists between single property ownership and partnered violence. However, they confirmed the violence-mitigating effect of joint property ownership for married women living in rural areas in Latin America.

Peterman et al. (2017), in a 28-country international survey, concluded that the effect of asset ownership on IPV is contextual and highly variable. They confirmed a negative association in 3 countries, a positive association in 5 countries, and no significant association in 20 countries. Further disaggregation by asset types showed no conclusive patterns. Heise (2011) contributes to this discourse by asserting that securing land rights for women may trigger partner resentment and inadvertently contribute to episodes of partnered violence. Sano and Sedziafa (2017) came to a similar conclusion in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where independent asset ownership was associated with increased physical and sexual IPV. Narayan (2000), suggests that these effects are short-term and only present themselves in instances where women “go against the grain” by challenging existing male authority, which will eventually subside when a new egalitarian regime emerges. In a theoretical note, Gahramanov et al. (2021) proposed that joint property ownership serves as compensation, encouraging women to willingly contribute more to household tasks and reducing the likelihood of men resorting to violence. Grabe et al. (2015) found evidence supporting the assertion that structural changes in women’s land ownership related to greater power and decreased psychological and physical violence in Nicaragua and Tanzania, despite traditional norms prohibiting married women’s land access. Bhatla et al. (2006) extend the argument by calling attention to the timing of the asset acquisition. They argue that if the property was acquired before the union, the “patterns of behavior, control, and family dynamics have been set” (Bhatla et al. 2006, p. 76). In Kerala, it was observed that women who came into the union with properties either through their dowry or inheritance were at lower odds of being abused. These grounds for a more gender-equitable power dynamic in the union.These diverse findings underscore the nuanced and multifaceted nature of the relationship between asset ownership and IPV, emphasizing the importance of context-specific considerations in understanding and addressing this complex dynamic.

Although these findings are encouraging, there is a notable absence of studies in Ghana that provide valuable insights into how economic empowerment through property ownership impacts physical violence endorsement. We contribute to the scarce literature on the topic by focusing on the two main identified barriers to eliminating IPV in Ghana, where women’s rights to own and inherit land are protected under the law. However, their customary land rights are insecure, and they cannot, in practice, own land.

Methods

Data

We sourced data from the sixth round of the Ghana Demographic and Health Survey (GDHS), conducted in 2014. The Demographic and Health Survey collects data on men's and women’s health and well-being, including physical IPV. The survey is nationwide, with a sample of 9,396 women in their reproductive age (15–49) and 4,388 men between 15 and 59 years. However, due to non-responses, the final sample for the study was 5229 women and 1746 men. The 2014 GDHS was conducted using the two-stage sample design from the 2000 Population and Housing Census (PHC) to produce estimates for key indicators at the national level. In the first phase, clusters were selected, including enumeration areas. Four hundred and twenty-seven clusters were designated, with 211 in rural and 216 in urban areas. A systematic sampling method was employed in the subsequent stage to select households from a list randomly. The IPV module was administered to randomly selected ever-partnered women and men aged 15 to 59 years in every second sampled household via an adapted Conflict Tactics Scale.

Outcomes

The dependent variable in our study was formulated from five questionnaire items that consider differing views and facets of physical violence in Ghana. The respondents were asked, “In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations? If (i) she went out without telling the husband, (ii) she neglected the children, (iii) she argued with the husband, (iv) she refused to have sex with him, and (v) she burnt the food”. The responses “yes” and “no” were used to create an additive scale to tap into instances where wife abuse is considered acceptable in any of the five instances. This was then transformed and dummy-coded “1” if the wife-beating is justified in at least one of the five instances and “0” if not justified in any scenario.

Among the women (see Table 1), the scenarios that were most likely to exact a positive response were “neglects the children” (25.03%), followed by “if she goes out without telling him” (20.27%) and “if she argues with him” (19.32%). Similarly, among the men, the scenarios that most likely elicit a positive response were “neglect the children” (6.76%), followed by “going out without telling him” (4.93%), and arguing with him” (4.64%).

More than four-fifths of the men (90.09%) believed that wife beating is never justified compared to 67.36% of women in the same category. A more significant proportion of women (32.64%) than men (9.91%) believed that wife beating is justified in at least one of the scenarios.

The primary explanatory variable in the study, property ownership, is land and house ownership. Respondents were asked the following questions: “Do you own this or any other house either alone or jointly with someone else?” and “Do you own any land either alone or jointly with someone else?” to which the responses were Alone, Jointly, both alone and jointly, and do not own.

In Fig. 1, observing the distribution of property ownership among women reveals a significant majority without land (69.98%) or residential property/ies (72.30%). When disaggregated by the type of ownership, we find that women who own land (16.05%) or a house (17.71%) jointly are more prevalent than other categories.

Figure 2 describes the sample profile of property ownership among men, revealing a notable contrast with that of women. Men exhibit a relatively higher proportion of ownership, with 56.36% owning land and 44.06% owning houses, surpassing the corresponding figures for women in this category. Furthermore, most men preferred the sole right to either land or a house. These findings reinforce the disparities in property ownership in Ghana, where men own more landed properties than women (USAID 2010).

Empirical strategy

We estimated a multivariate logistic regression model, adjusted for demographic attributes, and reported odds ratio with clustered standard errors. An odds ratio greater than “1” means the explanatory variable positively affects the dependent variable, and an odds ratio less than “1” means the association is negative. We started with a model specified as follows.

We estimated Eq. (1) separately for partnered women by their place of residence. This was followed with a stepwise regression that successively added more predictor variables to account for potential endogeneity issues that may arise from omitted variables (see Eq. 2).

where \(i\) indexes the respondent, \(\alpha\) is the intercept, \(\beta\) is the slope parameter for property ownership, \(\gamma\) is a vector of slope parameters for the control variables, and \(\varepsilon\) is the error term. We controlled for underlying structural determinants of wife beating justification, including autonomy, access to information, employment, age, education, religion, ethnicity, and union type.

Our analysis examines how property ownership affects wife beating justification, all else equal. However, there exists the possibility of unobserved confounders that could be associated with property ownership, economic status, and the likelihood of justifying physical violence. For instance, individuals from wealthier households may have a higher probability of owning assets, but this may not necessarily offer the same protection as property ownership for poorer families, and vice versa. The household wealth index, computed by the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), incorporates physical assets. Consequently, it is anticipated that household wealth could be correlated with property ownership, and wife beating justification may also be associated with household wealth. This association was supported by preliminary analysis, which indicated the presence of multicollinearity between the two variables. So, we could not incorporate the wealth index in our estimation. Similarly, we recognize that the justification of physical violence may impact household property allocation decisions, raising concerns about reverse causality. However, the available DHS data do not provide information on the timing of asset acquisition (which could mediate as an instrumental variable), making it challenging to address this issue adequately. As a result, we could not establish a causal relationship, and it is essential to interpret our findings with this limitation in mind.

Table 2 summarizes the explanatory variables and how they were introduced in the empirical models.

Results and discussion

Table 3 shows the cross-tabulation using weighted frequencies and Pearson Chi-square to test the independence of the distribution between the independent variables and wife beating justification. Among the women observed, 36.29% of those who did not own any landed property, more than any other category, believed wife beating is justified. In contrast, 34.83% of women who solely owned a house justified wife beating. For the men, 13.64% of those who owned land jointly and 12.61% who owned a home jointly were more accepting of attitudes that justified wife beating. Thirty-nine percent of women justify wife beating when their partner decides on large household purchases. Approximately 13% of men who made household purchase decisions alone justified wife beating.

A higher proportion of men (26.09%) and women (42.26%) in non-waged jobs were more inclined to justify wife beating. Among the respondents, women (39.76%) and men (11.92%) in rural areas justified wife beating compared to their urban counterparts. Additionally, nearly half of the women and 17.54% of men in polygamous unions justified wife beating. Women and men who identified as traditionalists reported higher levels of wife beating justification. The association was also significant for women (44.49%) and men (16.02%) who belonged to the Northern tribes, compared to other ethnic groups. These relationships show significant associations.

Multivariate analysis

Table 4 presents the results of the unadjusted logistic regression model, investigating the direct association between property ownership and wife beating justification. The preliminary results reveal the presence of multicollinearity when both land and house ownership are included simultaneously in the multivariate analysis. To address this issue and provide valuable insights for policy decisions, separate estimations were conducted for these two variables, with further aggregation based on the place of residence. Compared to women who did not own any land, rural women who owned land alone (OR 0.597) had a lower likelihood of justifying wife beating. Similarly, rural women who owned land jointly (OR 0.622) or alone and jointly (OR 0.292) also exhibited a reduced likelihood of justifying wife beating. Similar patterns are observed for urban women, except the association was statistically insignificant when a woman owned the land alone. These findings suggest a minimal disparity between rural and urban areas in terms of the effect of land ownership on physical violence justification in Ghana. In the total sample model, the results show that when a woman owns land alone (OR 0.665), jointly (OR 0.574), or both alone and jointly (OR 0.388), there is a significant reduction in the odds of justifying physical violence. These findings support the arguments put forth by the resource theory. The resource theory asserts that access to and owning tangible assets is a fallback position for women, which reduces their vulnerability and empowers them to break free from and relinquish patriarchal beliefs that justify wife beating.

The independent effect of owning a house, jointly or both alone and jointly, significantly reduced the odds that a woman will justify wife beating in the rural (OR 0.624 and OR 0.368 respectively) and full sample (OR 0.773 and OR 0.542 respectively). When the residence is jointly owned, the presence of the potential costs of house dissolution is likely to deter violent partners, thereby reducing their tolerance for physical violence. This suggests that home ownership by women cushions and provides security instead of creating dependency on an abusive partner for shelter. This confirms the protective nature of homeownership for women, as previously observed in studies by Kelkar et al. (2020) and Peterman et al. (2017).

In examining the independent effect of wife beating justification among men (see Table 5), we could not test the rural–urban variation because disaggregating the sample made some observations too small to make meaningful statistical inferences, and some variables were also omitted due to missing data. Analyzing the total sample, the odds of justifying wife beating were significantly reduced among men who owned land alone (OR 0.987). This finding aligns with the resource theory, which argues that individuals with more significant resources are less likely to use force to retain dominance. On the other hand, men who owned land jointly (OR 1.490) had higher odds of justifying physical violence, indicative of a different pattern observed for the women.

In model 2, owning a house alone (OR 1.387) or jointly (OR 1.550) significantly increased the likelihood of men justifying wife beating. A priori, it was expected that the potential costs and the risks associated with the dissolution of a house or land would deter the use of IPV to assert control and dominance. This result finds meaning in patriarchal norms, which may be reinforced further by the belief that men possess superiority through property ownership (Sano and Sedziafa 2017) and challenges the arguments put forth by the resource and relative resource theory. A significant deviation is observed when comparing Tables 4 and 5, particularly when land is jointly owned, and a house is owned alone or jointly. Unlike women, men with these forms of ownership had higher odds of justifying physical violence. This discrepancy highlights the disadvantage that women face in land and house ownership. A small proportion of the sampled women owned any landed property, but it significantly impacted their attitudes toward justifying physical violence. Equal access to essential properties underscores the importance of these unique circumstances in empowering women and promoting overall development.

Table 6 presents the adjusted models that incorporate additional socio-demographic and cultural factors. The discussion focuses on models 1 and 3, as the estimates of the control variables in both models do not exhibit any significant differences. We fail to accept the null hypothesis in the Hosmer–Lemeshow test (chi2 (98) = 113.54), indicating that our model fits reasonably well. When other predictors are introduced, the association between women’s land ownership and physical violence justification remains consistent with the findings from Table 4. However, there is a notable difference: women who own a house alone were found to be 1.297 times more likely to justify wife beating. This paradox may be explained by the idea that women who own a house alone will justify physical violence to preserve their marital status rather than face the social stigma of being unmarried (Haj-Yahia 2000). This highlights the role of other variables in explaining women’s attitudes toward justifying wife beating.

The protective nature of homeownership for women has been confirmed by other studies (Jose and Younas 2022; Koppelman 2022; Oduro et al. 2015). One consistent finding across these studies is that the economic vulnerability resulting from barriers to property access compels women to remain in abusive relationships. It is crucial to note that the type of ownership and the proportion of ownership introduce diverse dimensions in the relationship between property ownership and justification of wife beating in intimate relationships. The ownership of land by women not only bridges and narrows the gender inequality gap but also increases their bargaining power within the household in terms of decisions that bother around household production and consumption that impact the overall well-being of the same.

We observed statistically significant effects of some variables that we controlled for. Our findings indicate that the likelihood of justifying physical violence significantly increases when decisions on household purchases are made by either the woman (OR 1.487) or her partner (OR 1.321). Conversely, men tend to justify physical violence more when they have sole decision-making authority (OR 1.496) over such purchases. These results aligned with the arguments of the gendered resource theory, which suggests that the defined gender roles within society play a role in shaping these dynamics. Compared to women in non-waged positions, unemployed women (OR 0.823) exhibit significantly lower likelihoods of justifying physical violence. Additionally, our study reveals that men (OR 0.420) and women (OR 0.743) in waged jobs exhibit a decreased propensity to justify physical violence. This observation lends support to the premise of the resource theory.

Education proved a pivotal factor in shaping perspectives on the acceptability of physical violence. Both men (OR 0.899) and women (OR 0.934) show decreasing odds of endorsing violence as their level of education increased. The influence education exerts varies based on whether it adopts a modifying or transformational approach and how it is employed to uphold conventional gender norms or challenge gender bias. Transformative education is pivotal in challenging deeply ingrained patriarchal norms that have become normalized in society. It provides a platform for actively confronting and dismantling harmful beliefs and attitudes that have historically contributed to the socialization and conditioning of individuals to accept wife beating as normal. Our results indicate a decrease in wife beating justification with increasing age among men (OR 0.989) and women (OR 0.982). The arguments of the social learning theory suggest that norms, such as the social acceptability of physical violence, are typically transmitted from older generations to the young. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that while more aged men and women may act as custodians of these traditions and pass them on to younger generations, they may not necessarily endorse them. According to Krause et al. (2016), older men who have accumulated communal and financial resources and hold significant authority within the household/community may not feel the need to assert dominance by justifying physical violence.

Furthermore, we observed that the location of residence did not have a notable impact on wife beating justification among men. However, rural women (OR 1.292) were more likely than urban women to report an increased justification of wife beating. The normalization of IPV and preserving traditional norms are often more pronounced and entrenched in rural areas. While we recognize that not all rural areas are the same, the lack of legal protection, conservative beliefs, and limited access to support services in some rural areas create an environment where IPV is normalized. Moreover, women in polygamous marriages (OR 1.247) tended to be more inclined toward justifying wife beating. Polygamous unions breed competition for their partner’s attention, leading some women to justify and tolerate abuse to sustain that attention. Additionally, women belonging to the Islamic (OR 1.442) and traditional (OR 1.358) religious sects were more likely to justify abuse, regardless of whether they faced difficulties in their domestic roles or challenged patriarchal control. This does not discount religion as a regulatory influence but highlights the different shared values among followers. We also found evidence suggesting that, compared to individuals in the Akan ethnic category, Ewe men (OR 0.329) and Ga/Dangme women (OR 0.680) were less likely to justify wife beating. Conversely, Northern women (OR 1.157) had higher odds of justifying partnered abuse. Mann and Takyi (2009) argue that patrilineal tribes, where men are given priority in inheritance, are more likely to support abuse. While this may hold for patrilineal tribes, societal evolution can shape attitudes that justify wife beating, as evidenced by the case of Ewe men. Increasing access to print or electronic information significantly reduced the likelihood of wife beating justification among men (OR 0.554) and women (OR 0.770). However, Okenwa-Emegwa et al. (2016) question the empowering effectiveness of television and radio programs focused on “campaigns against violence” in curbing wife beating justification among women.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the need to unpack the factors and underlying reasons for gender variation in justifying physical violence. We found that property ownership among women plays a significant role in discouraging the justification of wife beating, while the opposite was observed among men. These findings underscore the necessity of enhancing women’s access to landed properties to improve their living conditions and empowerment and reduce the inclination to endorse and remain in abusive relationships. This aligns with the United Nations Refugee Agency’s campaign to establish the “right to land and housing” as an essential human right. A notable example from the 1970s in Europe was the advocacy for housing legislation that provided dedicated support and permanent shelters (beyond temporary relief offered by women’s shelters) for women who experienced domestic violence, enabling them to separate from their abusive unions.

Owning a property can complement the efforts of social support groups in providing refuge for such women, particularly in Ghana, where there is a shortage of shelters to accommodate them. Therefore, policy interventions should remove barriers that hinder women’s access to residential and land ownership. This can serve as an effective strategy to combat attitudes that perpetuate IPV and contribute to creating a safer environment for women. Reforms to empower women must be accompanied by substantial, cultural, and educational changes to end the culture of abuse, foster cooperation among individuals, and promote zero tolerance of violence. This also adds to the Sustainable Development Goal’s specific targets 11.1 and 11.3, which seek to ensure “access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums” and “to enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries.” This goal caters to permanent or temporary housing for victims of abuse who may not have any shelter outside the abusive union.

Despite the importance of this study, it is without its limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits establishing causal relationships. Longitudinal research is necessary to fully grasp the potential reciprocal association between property ownership and physical violence. This will allow us to examine how these factors interact over time and determine if the relationships hold in diverse contexts. For instance, it is plausible that the correlation between property ownership and IPV justification is non-linear, as societal acceptance and behavioral responses may evolve. Capturing this process requires observing over an extended period rather than at a single point. In addition, the indicators of asset ownership used in the GDHS have certain limitations. It fails to capture factors such as the duration of ownership or the value of the assets. These additional aspects could provide further insights into the relationship between property ownership and IPV justification.

Notes

This section provides further information on how the independent variables were measured and how they were introduced in the estimations.

-

1.

Autonomy The autonomy of respondents was evaluated by asking about the individual responsible for making decisions regarding significant household purchases. The response options provided included “husband,” “wife,” or “both husband and wife.” The degree of autonomy and whose authority is at stake will influence whether a man or woman justifies physical violence.

-

2.

Employment The survey participants were asked about their employment status and the nature of their income. The authors created a new variable that matched employed individuals with their respective payment methods and recorded them into four categories: “not working,” “Waged job,” “Paid in-kind job,” and “non-waged job.” This variable aimed to reflect the source of livelihood for each respondent.

-

3.

Education in years The variable “education” quantifies the number of years of schooling completed by the respondents, making it a continuous variable. Based on prior expectations, we anticipate that as the respondents' education level increases, there will be a diminishing tendency to endorse attitudes that justify physical violence. Therefore, we expect a negative correlation between higher education levels and justifications for wife beating. This correlation is contingent, to some extent, on whether education is primarily transformative or reformative.

-

4.

Age in years This variable represents the respondent's age and is continuous. Including age as a control variable accounts for variations in attitudes about violence over different periods and life stages. However, it's important to note that the anticipated effect of age on attitudes is inconclusive, meaning it could be either positive or negative, as the direction of this influence remains to be determined.

-

5.

Place of residence This is a dummy variable that reflects the geographical location of the respondent's home. This variable accounts for stable, unmeasured contextual factors that influence their attitudes regarding the justification of wife beating. It is categorized into two groups: rural and urban. We anticipate that individuals living in rural areas, where traditional cultural values may still sway, are more inclined to endorse attitudes justifying wife beating than their urban counterparts. This discrepancy could also be influenced by variations in women's empowerment and educational campaigns between rural and urban areas.

-

6.

Type of marriage This variable makes inquiries about the presence of additional wives within a marriage or union, extending beyond the simple distinction of whether an individual is married. Based on the responses, the variable was recorded into two categories: monogamous and polygamous marriages. Based on prior expectations, we anticipate that women in polygamous marriages may be more prone to justifying physical violence. This could be attributed to perceived competition for their husband or partner's attention, thus suggesting a positive relationship between polygamous marriages and justifications for physical violence.

-

7.

Religion The religious affiliation of a respondent represents a cultural variable that encompasses a belief system contributing to the preservation of the prevailing societal norms. This variable was categorized into the three primary religious sects in Ghana: “Christianity,” “Islam,” and “Traditional” belief systems. The expected sign of influence on physical violence justification could be positive or negative, contingent on the specific religious sect and their interpretation of socially acceptable conduct.

-

8.

Ethnicity The respondents were asked what ethnic group they belonged to, and the responses were categorized into Akan, Ga/Dangme, Ewe/Guan, the Northern (including Mole-Dagbani, Mande, Gurma, and Grusi), and others. The Ewe and Northern ethnicities tend to have patriarchal traditions, whereas the Akan culture is predominantly matriarchal. This variable is expected to provide valuable insights into the cultural disparities surrounding accepting physical violence across different ethnic groups.

-

9.

Access to information This variable encompasses the frequency and possession of mass media devices, which serve as sources of information. It includes inquiries about “household ownership of television, radio, and telephone” and the “frequency of radio listening, television watching, and newspaper reading.” The study grouped responses into two categories to facilitate meaningful statistical analysis: “at least once a week” and t “not at all.” These groups were then utilized to create an information access index constructed through factor analysis, explicitly employing the principal component factor (PCF) method as the factor extraction technique.

Data availability

The report and dataset are freely available to the public at www.measuredhs.com upon request and submission of a consent paper.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Adu-Gyamfi E (2014) Challenges undermining domestic violence victims’ access to justice in Mampong municipality of Ghana. JL Pol’y Glob 27:75

Atkinson MP, Greenstein TN, Lang MM (2005) For women, breadwinning can be dangerous: Gendered resource theory and wife abuse. J Marriage Fam 67(5):1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00206.x

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Bhatla N, Chakraborty S, Duvvury N (2006) Property ownership and inheritance rights of women as social protection from domestic violence: cross site analysis. ICRW, Washington

Bhattacharyya M, Bedi AS, Amrita C (2011) Marital violence and women’s employment and property status: evidence from North Indian villages. World Dev 39(9):1676–1689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.02.001

Boudreaux K (2018) Intimate partner violence and land tenure: what do we know and what can we do?. United States Agency for International Development (USAID). AIDOAA-TO-13-00019

Dickson KS, Ameyaw EK, Darteh EKM (2020) Understanding the endorsement of wife beating in Ghana: evidence of the 2014 Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Women’s Health 20(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-00897-8

Gahramanov E, Gaibulloev K, Younas J (2021) Women’s type of property ownership and domestic violence: a theoretical note. Rev Econ Household 19:223–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-021-09544-z

Gahramanov E, Gaibulloev K, Younas J (2022) Does property ownership by women reduce domestic violence? A case of Latin America. Int Rev Appl Econ 36(4):548–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2021.1965551

Goode WJ (1971) Force and violence in the family. J Marriage Fam 33(4):624–636. https://doi.org/10.2307/349435

Grabe S, Grose R, Dutt A (2015) Women’s land ownership and relationship power: a mixed methods approach to understanding structural inequalities and violence against women. Psychol Women Q 38(1):7–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314533485

Haj-Yahia MM (2000) Wife abuse and battering in the sociocultural context of Arab society. Fam Process 39(2):237–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39207.x

Heise LL (2011) What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London

Hidrobo M, Peterman A, Heise L (2016) The effect of cash, vouchers, and food transfers on intimate partner violence: evidence from a randomized experiment in Northern Ecuador. Am Econ J Appl Econ 8(3):284–303. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150048

Hulley J, Bailey L, Kirkman G, Gibbs GR, Gomersall T, Latif A, Jones A (2023) Intimate partner violence and barriers to help-seeking among Black, Asian, minority ethnic and immigrant women: a qualitative meta-synthesis of global research. Trauma Violence Abuse 24(2):1001–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211050590

Institute of Development Studies (IDS), Ghana Statistical Services (GSS) and Associates (2016) Domestic Violence in Ghana: Incidence, Attitudes, Determinants, and Consequences. IDS, Brighton

Jose J, Younas J (2022) inclusion and women’s bargaining power: evidence from India. Int Rev Appl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2022.2044459

Kadengye DT, Izudi J, Kemigisha E, Kiwuwa-Muyingo S (2023) Effect of justification of wife-beating on experiences of intimate partner violence among men and women in Uganda: a propensity-score matched analysis of the 2016 Demographic Health Survey data. PLoS ONE 18(4):e0276025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276025

Kelkar GOVIND, Gaikwad S, Mandal S (2020) Women’s land ownership and its ramifications for gender-based violence. Working paper 4. GenDev: Centre for Research and Innovation, Gurgaon

Kemigisha E, Nyakato VN, Bruce K, Ndaruhutse Ruzaaza G, Mlahagwa W, Ninsiima AB, Michielsen K (2018) Adolescents’ sexual wellbeing in southwestern Uganda: a cross-sectional assessment of body image, self-esteem, and gender equitable norms. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(2):372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020372

Koppelman CM (2022) Empowered homeowners, responsible mothers: promises and pitfalls of maternalist housing provision in Brazil’s Minha Casa Minha Vida Program. Soc Polit Int Stud Gend State Soc 29(4):1449–1473. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxac026

Krause KH, Gordon-Roberts R, VanderEnde K, Schuler SR, Yount KM (2016) Why do women justify violence against wives more often than men in Vietnam? J Interpers Violence 31(19):3150–3173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515584343

Linos N, Slopen N, Subramanian SV, Berkman L, Kawachi I (2013) Influence of community social norms on spousal violence: a population-based multilevel study of Nigerian women. Am J Public Health 103(1):148–155. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300829

Lundgren E, Heimer G, Westerstrand J, Kalliokoski AM (2001) Men’s violence against women unequal in Sweden—a prevalence study. Brottsoffermyndigheten and Uppsala Universitet, Stockholm

Mann JR, Takyi BK (2009) Autonomy, dependence, or culture: examining the impact of resources and socio-cultural processes on attitudes towards intimate partner violence in Ghana, Africa. J Fam Violence 24(5):323–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9232-9

Narayan D (2000) Voices of the poor: can anyone hear us? World Bank, Washington

Oduro AD, Deere CD, Catanzarite ZB (2015) Women’s wealth and intimate partner violence: insights from Ecuador and Ghana. Fem Econ 21(2):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2014.997774

Okenwa-Emegwa L, Lawoko S, Jansson B (2016) Attitudes toward physical intimate partner violence against women in Nigeria. SAGE Open 6(4):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016667993

Panda P, Agarwal B (2005) Marital violence, human development, and women’s property status in India. World Dev 33(5):823–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.01.009

Peterman A, Pereira A, Bleck J, Palermo TM, Yount KM (2017) Women’s individual asset ownership and experience of intimate partner violence: evidence from 28 international surveys. Am J Public Health 107(5):747–755. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.303694

Sano Y, Sedziafa AP (2017) Women’s land ownership and intimate partner violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In: PAA 2017 Annual Meeting. PAA.

Scoglio AA, Zhu Y, Lawn RB, Murchland AR, Sampson L, Rich-Edwards JW, Koenen KC (2023) Intimate partner violence, mental health symptoms, and modifiable health factors in women during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open 6(3):e232977. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.2977

Seedat S, Rondon M (2021) Women’s well-being and the burden of unpaid work. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1972

Smith MK (2012) What is pedagogy? http://infed.org/mobi/what-is-Pedagogy. Accessed 28 June 2023

Sohini P (2016) Women’s labour force participation and domestic violence. J South Asian Dev 11(2):224–250

USAID (2010) USAID country profile. Property rights and resource governance, Ghana. http://usaidlandtenure.net/ghana

Vu L, Pulerwitz J, Burnett-Zieman B, Banura C, Okal J, Yam E (2017) Inequitable gender norms from early adolescence to young adulthood in Uganda: tool validation and differences across age groups. J Adolesc Health 60(2):S15–S21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.027

Waltermaurer E (2012) Public justification of intimate partner violence: a review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 13(3):167–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838012447699

Waltermaurer E, Butsashvili M, Avaliani N, Samuels S, McNutt LA (2013) An examination of domestic partner violence and its justification in the Republic of Georgia. BMC Women’s Health 13(1):44–52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-13-44

World Health Organization (2021) Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional, and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. World Health Organization, Geneva

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER) for their visiting Ph.D. fellowship program and their engagement with the University of Ghana’s Ph.D. program in development economics under which this study was conducted.

Funding

The authors did not receive financial support from any organization for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Drafting of the original manuscript, analysis, and interpretation of data: BO-B. Supervision and critical review of the manuscript for intellectual content: BO-B and EN-A. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Owusu-Brown, B., Nketiah-Amponsah, E. Property status and wife beating justification in Ghana: an integrated theoretical approach. SN Soc Sci 4, 63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00812-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00812-6