Abstract

Bangladesh is exposed to frequent natural disasters such as floods, cyclones, tidal surges, and earthquakes. To improve resilience, the country has implemented multisectoral and muti-level national interventions based on international guidelines over the past few years. As a result, local people have become more knowledgeable about and adept at coping with disasters. While previous studies have focused on the causes and consequences of this development, this study examines the trend of successful disaster risk reduction (DRR) interventions through qualitative research in the southwest coastal area of Bangladesh. The authors performed 10 in-depth interviews, four focus group discussions, non-participatory observatory notes, and gathered 36 photographs of the surrounding landscapes in two selected villages of Dacope Upazila and Mongla Upazila, Khulna Division of Bangladesh. This study has suggested that coastal residents have changed their actions through DRR due to a range of awareness programs led by governmental and non-governmental organizations. While a top-down approach has improved early warning, disaster preparedness, and safer environments, a bottom-up approach should be considered to incorporate effective local DRR activities such as kinship network support. These findings suggest that both new and traditional disaster-coping activities should be integrated into more effective DRR strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In order to lessen vulnerabilities and improve community resilience in the event of a disaster, disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies, a post-modern concept, has emerged as a critical development approach. DRR is described as “the concept and practice of reducing disaster risk through reduced exposure to hazards, lessened vulnerability of people and property, wise management of land and the environment, and improved preparedness for adverse events” in the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR 2009). Since the 1990s, after the change in basic assumptions in global disaster management philosophy-from disaster prevention to disaster risk reduction- the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA 2005–2015) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR 2015–2030) have become the core guiding principle for disaster management for all member states (Kelman and Glantz 2015). Following the aim of DRR strategies, each of the nations is now working with multisectoral stakeholders both in policy and practice for building resilience by reducing vulnerabilities. The success story of DRR interventions can be seen in different scholarly works (e.g., Sutton et al. 2020a, b; Walch 2019; Zulfadrim et al. 2019) in different place of the world such as Australia, Indonesia, India and so on.

Since Bangladesh is one of the disaster risk hotspot countries and a ratified member state of HFA and SFDRR, over the past couple of decades, there has been a shift from “reactive humanitarian relief” based country to a “proactive risk management” country (Biswas and Mallick 2021; Roy et al. 2023). Disaster losses have therefore lessened in recent years. For instance, whereas roughly 500 thousand people perished from the 1970 Bhola Cyclone, the fatality rate dropped to several hundred in the events of Cyclones Aila (2009) and Sidr (2007), while only a few individuals died indirectly from the cyclones Fani (2019), Amphan (2020), and Mocha (2023) (Ahmed et al. 2020; Sammonds et al. 2021). Bangladesh’s development can be attributed to both a well-structured organizational framework and the effectiveness of DRR interventions carried out by the Ministry of Disaster Management and Relief, which was established in 2012 as a separate ministry following extensive transformation and reshaping (Habib et al. 2012; Roy et al. 2023). This administrative structure and the delegation of responsibilities to several committees, ministries, and organizations were formed by the Standing Orders on Disaster (SOD) (Habib et al. 2012). In addition to the preceding legal structure, the National Disaster Management Council (NDMC), National Disaster Management Advisory Committee (NDMAC), and Inter-ministerial Disaster Management Coordination Committee (IMDMCC) collaborate to coordinate DRR actions in Bangladesh (Habib et al. 2012; Roy et al. 2023).

Further, the implementation of DRR and climate change-related activities in Bangladesh depends heavily on international and/or national non-governmental organizations (NGOs), together with other governmental agencies at the lower levels of the public administration, such as the district or sub-district level offices (Roy et al. 2023; Suttonet al. 2020a, b). Bangladesh has a Disaster Management Act (2012), which came after the National Disaster Management Policy (2008) in terms of the legislative framework (Habiba et al. 2013a, b). The community has been positioned at the very end of the mainstreaming strategies for these legislative tools, where a complete package of capacity building comes by maintaining a hierarchical channel (Habiba et al. 2013a, b; Roy et al. 2023; Shaw 2012). At the early beginning of this channel, which consisted of national and district-level plans, policy planning, and the advocacy of awareness-raising used to take place. Bangladesh also has a number of connected agencies to handle catastrophes that may address each of the different threats such as cyclone preparedness program (CPP) for coastal community management (Habiba et al. 2013a, b; Habiba et al. 2013a, b; Roy et al. 2023; Shaw 2012).

Due to such legal and structural actions, like infrastructural development, raising awareness through workshops and training, managing emergency funds, and so forth, several researchers (e.g., Islam 2018; Mallick et al. 2017; Parvin et al. 2023; Roy et al. 2023; Shaw et al. 2013) have listed a significant change in disaster coping mechanisms at the local level over the past couple of years. Repairing roads and dams, growing trees that are resilient to disasters, disseminating information about impending disasters, and other activities have also been included in these strategies (Choudhury and Haque 2016; Garai 2014, 2017; Ghani 2020; Rahman and Rahman 2015; Sahin et al. 2021; Scolobig et al. 2015). Thereafter, community-led traditional disaster management initiatives, which used to create and reproduce by locals, and whose transmission and adaption came up generation after generation, have consequently been losing value and being replaced by modernized risk reduction measures (Sanyal and Routray 2016). In terms of risk reductions to cyclones, tidal surges, and salinity, in the southwest coast areas of Bangladesh, significant government interventions have been visible over the past few years (Ahsan and Khatun 2020; Roy 2019; Scott and Few 2016). As a result, change in local coping mechanisms has also been visible here, but this scenario was only partially depicted in earlier literature, which will be described below.

Given this context, some questions have arisen, such as ‘what is the changing pattern of DRR activities?’ and ‘how are the coping mechanisms are forming and reforming in the southwestern coastal districts of Bangladesh?’. Targeting a wider audience from academia and policymakers, the researchers further structured this study to investigate the consideration of community engagement in DRR interventions, known as the bottom-up approach, highlighted by the SFDRR. This study’s significance may result from the presentation of various aspects of changes in the built environment and physical environment, new social support systems and migration patterns, use of technology, increased reliance on both conventional and government-built infrastructures, and occupational change. Such understanding can help to appreciate the significance of the inclusion of local coping mechanisms when planning DRR and climate change adaptation plans.

Local DRR activities in southwest coastal areas of Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a shining example of successfully implementing various disaster management programs. Indeed, over centuries, people accumulated knowledge about and have lived with disasters, and thus developed various DRR strategies based on their lived experiences with disasters (Garai 2014). For the purpose of this paper, these activities have been referred to as local DRR activities. In this section, the authors have articulated some of the local DRR activities in the light of the latest disaster management literature under five major sub-themes which will be further used in data presentation and drawing conclusions.

Local early warning system and disaster preparedness (EWSDP)

To understand the status of the local EWSDP in the southwest coastal areas of Bangladesh several researchers (e.g., Azad et al. 2019; Garai 2017; Habiba et al. 2013a, b; Mallick et al. 2017; Sultana and Mallick 2015) have observed a traditional disaster management, which consisted of local knowledge and conventional mechanisms, have been practicing over period of time. For instance, Garai (2017), Habiba et al. (2013a, b) have found that by observing the change in weather and other natural objects’ behavior the elderly people in coastal areas of Bangladesh can predict an extreme natural event. The dissemination of such information was also found usual from person to person. However, to articulate traditional coping mechanisms several researchers have observed that different modern equipment has been used by local people and considered as conventional equipment. For example, Garai (2017) stated that,

…The wind blowing from the east corner is the indicator of imminent natural hazards. Moreover, drizzling lasting for several days and winds blowing from the east side bring the message of cyclone or tidal surge according to them…, by staying at the high brick-built house/cyclone center, they can save their lives… to disseminate the knowledge for… the village community forms a committee… This committee member wears especial dress and announces with loud speaker… There is also a hoisted black color flag in the special point of the village to inform people about the upcoming hazards. Union parishad office as well as mosques authority also announces disaster news by hand mike or other loud speakers. (p. 429)

How did such a development happen? Instead of giving this question’s answer most of the recent literature (e.g., Ahsan and Khatun 2020; Ahsan et al. 2020; Habib et al. 2012; Lumbroso et al. 2016; Roy et al. 2015) have given emphasized “who did such a development in the coastal areas?” and in answering they have credited to the CPP of Bangladesh. For instance, Habib et al. (2012) stated, “Central to the Bangladesh Early Warning System is the Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP), developed and improved through the efforts of the Government of Bangladesh (GoB), United Nations, International Red Cross, and the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society” (p. 29). Similarly, Roy et al. (2015), Ahsan and Khatun (2020) and Ahsan et al. (2020) have found a vital role of the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) and the broadcasting system in EWSDP. Though most of these works have highlighted the improved EWSDP in Bangladesh, many of them have advocated modern disaster management strategies without adequately addressing the way of the local people’s adaptation.

Local built environment in local DRR

According to past studies, to build resilience against coastal hazards the southwest coastal people have had some short of knowledge like EWSDP which helped them to shape up their neighborhood, infrastructure and the architectures. Researchers use the term “local built environment” to refer to the social ecosystem, infrastructure, architecture, and neighborhood that impact coastal residents’ vulnerabilities (Nagel et al. 2008). The local built environment is crucial for disaster management, as it initiates local government actions (Malalgoda and Amaratunga 2015) and promotes resilient community management (Haigh and Amaratunga 2010). For instance, in Bangladesh’s coastal regions, large clay pots are regularly used to store rainwater for use as a source of fresh drinking water, improving disaster preparedness and management (Garai 2017; Roy et al. 2020, 2023). In a similar vein, most roofs on houses in coastal areas have been found to be built closer to the earth so that wind can blow over them and can survive even in a cyclone. Storing dry food for future was another common culture that has also integrated in local DRR (Sony 2018; Sultana and Mallick 2015).

However, after the cyclone, Aila in 2009, several researchers have observed that the local coastal people now largely rely on modern knowledge with little emphasis on their traditional knowledge and are more likely to improve their neighborhoods with modern architects (Garai 2017). For example, building brick houses instead of traditional wooden houses, taking shelter in a cyclone shelter, and preparing emergency food, water, and medicine (Parvin et al. 2023; Roy and Sony 2019). Researchers from the past have reported that coastal populations were motivated to adopt contemporary disaster management techniques as part of improved national DRR interventions by the lessons learned from earlier disasters, such as the ineffectiveness of a conventional built environment against a massive disaster (Nowreen et al. 2013; Parvin et al. 2023). Most of the disaster literature has not, however, identified the trend of them changing local DRR patterns.

Social capital and local DRR

Social capital refers to resources that are formed through an amalgamation of moral obligations, trust and social and kinship networks and these resources are utilized in social struggles (Bourdieu 1986). To reduce vulnerability social capital plays a vital role in local DRR strategies until an outsider’s assistance reaches a disaster-affected area (Sanyal and Routray 2016). Social capital is a type of social network that develops through relationships between individuals and through pro-social activities like inclusion, cohesiveness, cooperation, and trust (Behera 2023; Roy et al. 2022). Most of the earlier scholar have stressed out on presenting the effectiveness of social capital at different stages of disaster management (Bankoff 2015; Panday et al. 2021; Sanyal and Routray 2016; Shoji and Murata 2021). For instance, in the context of post-disaster southwest coastal area of Bangladesh, Khalil et al. (2021) have observed that,

…over the long run, bonding relationships were strengthened as men frequently assisted their wives’ entrepreneurship. … at household level within the networks among family members; for example, women and children were involved in household activities and water resource management. … Bridging relationships work in between networks; for example, women working with other neighborhood women in producing handicrafts. (p. 10)

Alongside, kinship network scholars have also found a close link between local people and NGOs collaboration which played a significant role in post-disaster reconstruction and disaster preparedness (Islam and Walkerden 2014; Khalil et al. 2021; Shoji and Murata 2021). For instance, Khalil et al. (2020) found that Bangladesh women contributed to local innovation for climate change adaptation in the absence of male members. Despite this, sometimes strong social networks and local power elites possess a challenge to successful policy implications that have been evident by Islam and Walkerden (2017) and Choudhury and Haque (2016). Considering these perceptions, the researchers of this study also raised the question if there is any change in social capital that can impact local DRR in the study area.

Disaster-related training and awareness

Despite knowing the consequences of national actions and their efficacy, it can be difficult to understand how DRR is changing. In Bangladesh’s coastal areas, there have been successful efforts to enhance soft skills and increase knowledge through training and awareness campaigns (Parven et al. 2020; Roy et al. 2023; Roy and Sony 2019). As a result, society has become more inclusive (Hasan et al. 2019) and social inequalities have decreased (Nasreen et al. 2023). For instance, by policy and practice women participation in EWSDP have found frequent in coastal areas of Bangladesh (Hasan et al. 2019; Nasreen et al. 2023). Here, husbands’ migration to the city works as a key driving wheel to push women to be independent (Khalil et al. 2020).

The modern adaptive mechanisms, especially in agriculture (Mazumder and Kabir 2022), are another consequence of policies and practices that have contributed to the change in DRR of Bangladesh. Overall, a growing body of disaster literature shows (e.g., Choudhury and Haque 2016; Hasan et al. 2019; Lee 2019; Mallick et al. 2017; Parven et al. 2020, 2023; Roy et al. 2022; Roy and Sony 2019) how resilience has been increasing in the coastal community over the past ten years in Bangladesh without much emphasis on the trend of such development and the relationship between conventional and national DRR interventions.

Migration and occupational change

Migration has become a common occurrence in the twenty-first century due to urbanization, and it is expected to increase even more with the impact of climate change (Adger et al. 2020; Lincke and Hinkel 2021). According to experts, there could be a loss of land ranging from 60,000 to 415,000 km2 in the coastal areas due to rising sea levels. This could potentially result in the migration of anywhere from 17 to 72 million people to nearby cities (Lincke and Hinkel 2021). Both in the aftermath of a disaster and before one, migration as well as searching for alternate sources of living have become significant DRR strategies. The migration situation in coastal Bangladesh has been studied in various ways, such as permanent migration, seasonal migration, forced migration, and so on (Biswas and Mallick 2021; Islam and Hasan 2016; Mallick 2014; Roy 2017; Subhani and Ahmad 2019). Each researcher has found that the main driving force behind such migrations persists as the effects of climate change (Islam and Hasan 2016). For instance, a permanent migration has observed in southwest coastal areas of Bangladesh by Call et al. (2017), Mallick et al. (2017), Ahsan et al. (2016) and Islam (2021).

Similarly, as a coping mechanism from salinity intrusion a seasonal migration has been seen by Roy (2017), Roy et al. (2020), Chen and Mueller (2018), and Call et al. (2017). Change in demographic stratus and upland urbanization have been considered as initial impact of such migration (Ahsan et al. 2016). Howsoever, while the majority of earlier researchers classified migration as a contemporary DRR strategy and emphasized the need to investigate its basis and visuals, the researcher of this study would prefer to emphasize the current scenario in light of their adoption mechanism.

Methods and materials

Study context and location

The present study was conducted in two most disaster-affected coastal villages including village A of Dacope Upazila (sub-district) and village B of Mongla Upazila located in the Khulna Division of Bangladesh. Due to ethical considerations and the author’s commitment to the respondents, the village name has not been revealed. Howsoever, Dacope Upazila is located between 22° 24ʹ and 22° 40ʹ north latitudes, and between 89° 24ʹ and 89° 35ʹ east longitudes (Fig. 1). Mongla Upazila is located between 21° 49ʹ and 22° 33ʹ north latitudes, and between 89° 32ʹ and 89° 44ʹ east longitudes (Fig. 1). The villages A and B are located, respectively, 63 km. and 42.63 km. north from the coast of the Bay of Bengal; and 33 km. and 55 km. south from the Khulna city, respectively. The populations of village A and B were respectively 30, 430 and 12, 097 with 43.24% and 62.19% literacy rates (Rahman 2021). Besides, both villages are about half a kilometer away from the Sundarbans, a mangrove forest that stretches parts of both Bangladesh and India, and has an area of about 6060 square km. These selected areas are highly susceptible to cyclones and floods due to their geographical location.

Over successive generations, the local people in the study locations have been engaged mainly in prawn seed collection, shrimp farming, agriculture, woodcutting, and honey collection from the Sundarbans as a means of living. Due to the proximity to the coast of the Bay of Bengal and several rivers such as the Poshur flowing towards it, these villages are frequently struck by cyclones and are inundated by flash floods almost every year. Cyclone Aila caused massive destruction in these areas and after Aila, government organizations (GOs) and NGOs implemented different types of DRR programs such as polder reconstructions program in these areas (Roy and Sony 2019). Over centuries, people inhabiting this region have developed their own localized disaster-coping techniques. Therefore, it was useful to choose these villages to understand whether any change in disaster coping activities has been occurring.

Study tools and techniques

The investigation of the evolving DDR activity patterns in southwest coastal areas was conducted using a qualitative approach. This method covers research issues like understanding respondents’ perceptions and contrasting them with previous literature. Three qualitative research techniques were used by the researcher to gather relevant data: in-depth interviews (IDI), focus groups discussion (FGD), and non-participatory field observations. The researchers utilized purposive sampling to select IDI respondents in order to avoid data saturation, while FGD participants were selected through random sampling. Primary data were collected from the people who were above 25 years old, living in the study area for more than 20 years, and experienced at least two cyclones in their lives. These criteria for sample selection were applied to elicit rich accounts from the participants because they were better informed about DRR activities in the region than their younger and less experienced age groups. The application of several methods and techniques allowed for triangulation enhanced the quality of the data.

The researchers conducted interviews and FGDs during two separate periods to capture more of the latest information. The first took place between November and December of 2018, while the second occurred from May to June of 2023. Due to the lack of sufficient female participant’s opinions in the first cycle of data collection, the researcher conducted a second cycle of data collection where two more FGDs have conducted particularly with the female members of the study area. Prior to data collection, each of the respondents was informed about the objectives of this study. Following informed consent, a total of 10 IDIs were conducted to record participants’ in-depth narratives about DRR activities in each of villages. Each IDI was composed of five men and five women, including local political representatives, educators, religious leaders, business leaders, and elders of the village community. For collecting the IDI data, the first and third authors visited participants’ houses with a non-structured interview guide and a voice recorder. Each IDI lasted for about half an hour to one hour. The interview guide included a list of topics relating to DRR activities in the area.

To gain insight into the community-level activities for DRR, the authors conducted four FGDs in two study sites, with two discussions taking place in each of the selected villages—two for males and two for females. There was a total of 32 FGD participants, consisting of 15 males and 18 females. The average age of the FGD respondents was 45 years, and they were primarily farmers, fishermen, honey collectors, woodcutters, housewives, and day laborers. An FGD guide, which listed key topic areas relating to DRR interventions, was used to structure the FGD sessions. The first and third authors served as moderators for both FGDs at study locations chosen by both groups as convenient, such as local tea stalls for men and home yards for women. Each FGD lasted for about one hour to discuss their disaster preparedness and responses, and how disaster-related training and awareness have brought a change in their disaster coping activities.

Concurrently, extensive field notes were taken by the researchers (first and third authors) from the study sites in the period between November 2018 to December 2018. In order to boost the study’s validity and reliability the authors also observed the local physical, natural, ecological, built, and socio-cultural environment in both the study villages. They recorded their observations and captured 35 photographs that relate to the environment and DRR activities that people engaged in or knew about. Of these, 16 pictures were documented as traditional and 19 pictures as modern DRR activities. For instance, pictures of houses, water reserves and food storing patterns both for humans and cattle were captured. All data from IDIs, FGDs and photographs were pulled together to reach a saturation point.

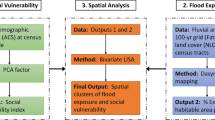

Analysis and ethical consideration

Since all the interviews were conducted in the local (Bengali) language, prior to coding, transcripts were translated into English. The researchers then read through and coded all the transcripts based on predetermined themes derived from a literature review of the study problem. The researchers used a deductive approach to create these themes which have helped researchers to understand the existing scenario and it’s changing pattern. The themes focus on changes in five major areas: (1) local warning systems and disaster preparedness; (2) local built environment; (3) social capital formation during disasters; (4) disaster-related training and awareness; and finally, (5) migration and occupation. The ‘Results’ section provides further exploration and elaboration on these themes. To understand the participants’ DRR activities, data from all sources, including interview transcripts and photographs, were triangulated.

In line with research ethics, the authors ensured confidentiality and the anonymity of the research participants as well as the study villages by using pseudonyms throughout the paper. Apart from this, before data collection, each respondent was informed about the research objective, the identity of the researchers, the participants’ roles and ability to withdraw from the study. They were also informed about how the data would be used and for what purposes, and the process of publishing results. Oral consent was obtained from each participant.

Results

The findings of the present study revealed that notable changes in local DRR activities have occurred over the past decades. Traditionally, coastal people predicted any future disaster by observing variations in local weather patterns. This knowledge was transmitted across successive generations. According to participants, traditional knowledge was only somewhat effective in dealing with Aila that struck southwestern Bangladesh including the study locations in 2009. Details about the changes in disaster-related coping activities are presented in the following sub-sections.

Change in local EWSDP

Traditionally, local people speculated about natural hazards by observing variations in local weather conditions, abnormal animal behaviors, waves of rivers, and certain months of the year. They relied on their lived experiences of disasters, informal knowledge and wisdom transmitted across social generations. An FGD respondent reported:

In 1988, my grandfather predicted a disaster by observing the weather without any modern technology. He warned us to be alert if we saw pitch-black clouds, felt cold winds from the northwest, and observed abnormal animal behaviors like barking dogs, flying egrets, and ants moving upwards. His prediction came true a few hours later. (Das,Footnote 1 56 years, Farmer, Dacope)

Another participant echoed:

If drizzling continued for seven to 12 days, we could understand it as a sign of [imminent] disaster. (Nath, 37 years, fisherman, Dacope)

In contrast to their reliance on somewhat traditional sources of warning for disaster, some participants reported that they nowadays depend more on information technology and other means of gathering information about probable natural calamities. For example, instead of the traditional modes of communication such as word-of-mouth, they depended on modern technologies such as television, radio, mobile phones and the Internet which provide a more authentic weather forecast. For instance, a respondent reported:

I used to ask elders for weather predictions before going to the Sundarbans Forest. But extreme events like Aila couldn’t be predicted. Now, I have a radio from an NGO and I listen to it before going to the forest. (Kha, 37 years, seasonal woodman, Mongla)

Thus, the findings of this study show that modern technologies such as radio have recently replaced some of the traditional means of knowing about weather forecasts. Furthermore, the traditional word-of-mouth warning system was replaced by trained volunteers who have received training both from the government and NGOs. Trained volunteers now play a crucial role in disseminating information about the early warning system, whereas messages about weather forecasts were sent through word-of-mouth in the past. Generally, these volunteers use life jackets, hand mikes, horns/whistles, and red flags to warn people about natural calamities such as cyclones and floods. The research participants added that they are more likely to go to cyclone centers after hearing about warnings now than they did in the past. Traditionally, they would take shelters wherever they could such as inside their own fishing boats or on embankments. A participant narrated:

Once we used boats, climbed trees, took shelter on embankments, religious institutions, and some local elites’ houses made of bricks. Now we go to take shelter in government cyclone shelters. (Sharder, 55 years, Fisherman, Mongla)

Similarly, another respondent recalled:

During Aila [a cyclone that stuck in the study location in 2009], in the afternoon, I visited the school embankment but found it risky. I went home and told my wife, who stored food and packed our clothes. Water started entering our room, and we were unable to take shelter on the nearby embankment due to a lack. (Das, 37 years, Primary School teacher, Dacope)

In addition, some interviewees informed that they knew what to do after knowing about any disaster warning. They learned how to protect their stored food and water for the future, as Das’s quotation above indicates. The findings suggest that the traditional means of communication gave way to more modern communication systems. At present, local people are more likely to use motorbikes instead of boats as a means of local transportation. However, this does not mean that they completely avoid boats. Instead, they have more recently upgraded their traditional boats by inserting motors and wheels. They called this kind of boat “trawler”. During disasters, they use these devices to communicate with each other. In addition, the use of electronic communication technology like cell phone has assisted them to receive early warnings about disasters. A respondent narrated:

My nephew alerted me about Cyclone Mahasen from Khulna in 2013. We took our cattle to a nearby shelter and stored rice in plastic pots. Then, my husband and I checked the seals of our water tank from an NGO before heading to the shelter. (Sonali, 32 years, housewife, Mongla)

Such findings indicate that the local people’s early warning and disaster preparedness have become more resilient due to the increased use of modern IT and associated technologies.

Changes in local built environment

The study findings indicate that there were some changes in local physical structures that people built to address some of the challenges associated with local natural hazards. An analysis of the photographs captured for the purpose of this study shows that changes have occurred in some of the physical features of the local landscapes including houses, embankments, dams, walls, cyclone shelter, roads and transport, food storage facilities, and so on.

Firstly, there was a built environmental change with regard to housing. Many coastal people built cyclone-resistant houses there. Previously, they had built their houses by using bamboos, straws, and Golpata (Nipa Fruticans) (Fig. 2) found in the Sundarbans (Garai 2014). In contrast, more recently most of them have built tin-shed houses (Fig. 2) and some of them have built cyclone-resistant concrete houses, as Fig. 2 below shows. Many study participants said that they had taken microcredit loans from NGOs for building their tin-shed houses which are more disaster-resistant than houses made of straw or leaves. In addition, participants recounted that they sometimes tied their house’s tins to strong rope and/or iron cables to a nearby tree (especially coconut tree). A respondent explained this:

Tin roofs are more sustainable and cost-effective than straw or Golpata. Some NGOs provide free tins, while others offer microcredit. Tin roofs can withstand strong winds and disasters, eliminating the need for yearly repairs. (Rigina, 43 years, housewife, Dacope)

During field observation, it was found that many local people lived in traditional houses, which were more vulnerable to damage during disasters such as cyclones. People from the lower-income and socio-economic groups could not build houses made of tin, brick and concrete, which have a higher chance of withstanding strong winds or floods (Fig. 2), compared to the traditional houses made of straw, mud, leaves and so on.

Secondly, there was a noticeable change in energy consumption patterns. In the past, local people had to depend on kerosene oil to light their houses, but now they are using solar energy for electricity. According to respondents, the Government provided solar panels to them free of cost. Solar energy brought significant change among them in the sense that they now can use mobile phones, radio, and television with satellite connections which assist them to receive information about disasters, as well as the weather forecasts. A few respondents complained that although the Government had taken a good initiative by providing solar panels free of cost, it failed to cover all areas. As a result, many people lacked access to solar panels and electricity. A participant expressed anger and frustration by saying:

The Government [of Bangladesh] launched this program for poor people and all, but due to the lack of good political connections, some people like us don’t get this; whereas some people who have political connections and money got these solar panels and electricity. So, we have to buy these with loans from NGOs. (Hari, 39 years, day laborer, Mongla)

However, at the same time, it was also evident that access to solar panels and electricity increased local people’s ability to learn about early warnings about any imminent disasters, which in turn assisted them in preparing for upcoming disasters. This indicates that because of electricity, people’s reliance on the traditional wisdom and experience-based early warning system changed to a modern technology-based early warning system.

Thirdly, this study revealed that in the coastal areas, salinity intrusion was a major problem. The participants informed that rainwater was a primary source of fresh drinking water during disasters and they stored rainwater during one rainy season for use during a disaster. As was seen, traditionally, people used clay pots (Fig. 3) to store water, but now modern water tanks are used to store drinking water for use during an emergency. According to informants, after Aila in 2009, government organizations and NGOs provided water tanks (Fig. 3) to them for free. Despite this, some villagers still used clay water pots. A participant explained:

We used to own around 10 to 12 clay pots which we kept outside our house to collect rainwater. Currently, we only have four of them, but they are still in use. I prefer drinking water from these pots compared to plastic ones as I find that the plastic ones sometimes emit an unpleasant odor. (Das, 37 years, primary school teacher, Dacope)

In a similar vein, some participants mentioned that if they kept the water in the plastic tank (shown in Fig. 3) for a long time, it would develop a bad smell and taste. When their stored water ran out, they would purchase water from nearby water purifying companies, which cost 1.5 BDT or 0.018 USDFootnote 2 per liter. Others, particularly women, would travel long distances to collect water from deep tube wells. Local NGOs also provided a few concrete tanks in the study areas.

The study reveals that the use of plastic pots (as seen in Fig. 3) distributed by GOs and NGOs after the Aila cyclone has not only improved water storage, but also enabled people to store food for future disasters. Before the Aila cyclone in 2009, traditional food storage structures made of bamboo and tin called “Gola” were commonly used for storing food. However, these structures often failed to withstand severe cyclones like Aila. The people in the study area have been using Gola, jute sacks, and clay pots for generations to store a large amount of unprocessed rice, as well as small tins to store dried foods such as pulse and wheat. Now, the most popular and effective food storage technique reported by some participants is the use of plastic barrels provided by NGOs and GOs. A respondent made it clear by narrating:

During a natural disaster, my neighbor’s 500 kg of rice in Gola was ruined by salty water. My 100 kg in jute sacks survived after I moved them to higher ground, but the rice in clay pots didn’t make it. A few years back, an NGO provided me with two plastic barrels, which I now use to store my essential food items. I hope in the future I can save my all food from any natural calamities. (Kader Gazi, 41 years, fisherman and farmer, Mongla)

During summer, people dry cow-dung and store these for future rainy seasons. Furthermore, they also used to use sticks and wood for fuel. However, a few participants mentioned that the upper-class people have been increasingly using Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) for cooking.

Social capital formation during disasters

In order to mitigate some of the effects of disasters, people in the study villages have historically relied on social connections and family support. Some participants in the coastal region stated that they relied on their family members, friends and relatives for support during disasters. A significant finding from this study was that people formed strong kinship bonds and connections with political party leaders to cope with natural hazards. For instance, according to Obaidur, a 34-year-old bike driver of Dacope, after Aila in 2009, his uncle, who lived in Khulna, came to visit them and the uncle brought groceries for one month and also some clothes for his children. He also gave some financial support.

The participants reported that there is a strong sense of community among the people. During disaster, people are willing to help each other without considering their own interests, which is a sign of a strong community spirit. During focus group discussions, some participants used “we” instead of “I” which is another indication of collectivism. They shared stories of how neighbors came together during cyclone Aila to warn, care for, and support each other both emotionally and financially. On this point a FGD respondent stated:

During a difficult time for our neighbor, Umma, who had lost her mother, we offered our support by visiting her home and spending time with her. I stayed at their house for two days to offer further help. Our family provided them with food for the following three days. Additionally, my husband covered all expenses related to the funeral. (Hasina, 47 years, housewife, Dacope)

Having access to money and power was crucially important during natural hazards. Local economic and power elites play an important role in the study areas during disasters, as well as at other times. Disaster-affected poor people rely on these elites for financial assistance in the form of loans. However, the terms and conditions of loans for them appear unfavorable. One respondent elaborated:

Mahajan [traditional money lenders] help us to buy tools like fishing nets, boats and so on. But they take two-thirds of our shares. We know they’re taking too much, but what we can do? Banks are not willing to give money [to us] and microcredit institutions take installments on daily basis. So, we have to get money [loan] from them [Mahajan]. (Nath, 37 years, fisherman, Dacope)

Interestingly, making strong connections with the local political elites was a coping activity for some participants. The people who had connections with the local political elites comparatively got more assistance after any disaster. However, over the past few years, several NGOs such as Shushilan, Grameen Bank, BRAC, and banks such as Uttara Bank Limited and Janata Bank Limited offered loans on simple interests. As a result, the influence of local elites has decreased. As was noticed from the findings of the study area, women were more likely to take microcredit from the NGOs rather than local elites. A respondent stated:

We [ women] get loan from the NGOs easily whereas Mahajans are not willing to give us any loan. It helps us to buy cattle and start a small business to support our families. In addition, NGOs provide us with different types of training like tailoring, cattle rearing and so on. They also teach us how to support family and decision-making. Once we didn’t have the ability to contribute to the family, but now I’m contributing to family income even when my husband has no job. (Bowri Biswash, 41years, tailor, Mongla)

On the other hand, male members of the study area claimed that the NGOs were not willing to give loans to them. For this reason, they had to take a loan from the local elites (Mahajans) at a higher interest rate. Participants added that they used the loan to construct cyclone-resistant houses which assisted them to combat disasters in the future. Generally, the local power structure is determined by the ownership of more than one bozra (a large boat that is used to collect wood, honey from the forest, and to catch fish), multiple businesses, large areas of land, and money. But after Aila, the local power structure had been shifted. One respondent indicated:

Now those who are supporters of the ruling party are considered more powerful. They get more relief and facilities [during disasters]. (Das, 37 years, primary school teacher, Dacope)

This quotation indicates that people without connections with local political parties would miss out on relief and government support. Thus, the findings hint at resilience built among the respondents due to the availability of microcredits facilities, bank loans with simple interest, and NGO support.

Consequences of disaster-related training and awareness

According to the informants, after Aila several intervention measures have been taken including the early warning system and preparation for disasters. Subsequently, awareness about disasters was growing rapidly in community people. For example, during any extreme natural event in the past, they were habituated to untie their cattle and set them free to protect themselves; but now they put them at cyclone shelters built by the Government. Many NGOs, with the assistance from local governments, arrange training and workshops on disaster management. Consequently, people learned what to do during, pre-and post-disaster. A respondent explained:

Generally, going to the Sundarbans for a long time to collect honey and Golpata were men’s main occupations in this area. That time women and children stayed home alone. In the past in this situation, women didn’t know what to do during a disaster, so they depended on local knowledge. Now they attend training and so they know what to do about disasters. (Shopon, 50 years, honey collector, Mongla)

Thus, the previous ‘act of God’ doctrine seems to be withering away now as a result of greater social awareness and training. This indicates that the influence of religion in shaping peoples’ disaster-related beliefs is also changing. Young people now believe that disaster is a natural process, and proper preparation is one of the most effective ways to minimize losses, deaths and damages.

Despite this significant change, it does not necessarily mean that people have lost their faith in religion. It appears that their religious beliefs have slightly been altered as a result of training and education. It was observed that local community clinics created a change in the local health care system. According to the respondents, through training and workshop, people have now learned about modern first aid. Several respondents reported that they have antiseptic cream and liquid in their homes. Unlike in the past, now people are less dependent on grass, herbs and local knowledge as first aid during a disaster. The respondents reported increased awareness of health and hygiene due to training and awareness programs launched by GOs and NGOs compared to the pre-Aila period. To make this point clear, a respondent stated:

Though I never used a sanitary latrine before Aila, after Aila I’ve attended a workshop and came to know about the process of germ and worm contamination. Now, I’ve built a new sanitary toilet with adequate facilities of soap and water, and I’ve encouraged my family members to use separate slippers and wash their hands with soap after using washrooms. (Pothik Miya, 50 years, businessman, Mongla)

As the above quotation indicates, NGOs such as BRAC provide training in the area and this seems to benefit many people. Such modern initiative has replaced open defecation by sanitary latrines and changed the traditional hygiene practices associated with DRR activities among the respondents.

Migration and occupational change due to disasters

Disasters often lead to dislocation and produce livelihood vulnerabilities. Out-migration from the disaster-affected areas was described as a coping activity by the study participants. Over the past few years, some of the respondents were involved in seasonal migration. For example, Jahan Molla, a 45 years old honey collector, during the harvesting season (from early December to early April) migrated to nearby districts. Due to increasing salinity, he failed to grow crops in his land, and worked as contractual labor for five months. This type of coping activity was less preferred, but often they had no other options but to migrate and take up a different occupation after disasters had occurred. The study findings showed that traditionally men were involved in collecting honey, chopping wood and Golpata from the Sundarbans from (January to AprilFootnote 3). In addition, fishing in rivers and the Bay of Bengal was another common traditional occupation of this area. A respondent recalled:

From an adolescent age, I’ve been involved in honey collection. My father and great grandfather were also involved in this occupation. Like me, my children would also be involved in this occupation. (Jahan Molla, 45 years, honey collector, Mongla)

However, for others, this was not a suitable option; they had to make hard choices such as migration out of their own villages and to towns. Many other people considered seasonal migration out of the Khulna region. Besides this, women were previously involved in handicraft activities which was viewed as a source of additional income. According to the participants, they could make some savings after meeting their daily expenses which may assist them in the future to cope with any crisis including disasters. A respondent said:

By catching prawn, I can easily pay my weekly installments of the microcredit to NGOs and also run two DPSs [Deposit Pension Schemes]. The Grameen Bank is one of them. They gave me a housing loan to build a house. (Hurri, 39 years, day laborer, Mongla)

After the cyclone Aila, because of the tidal surge, the cultivable land of these areas suffered degradation.

During harvesting season, men migrated to other districts for two or three months and worked as contractual laborers. After completing their contract, they returned back to their villages with cash which assisted them to support their families. As some of the participants mentioned, migration was the primary earning source from 2010 till the time of interviews. Thus, migration has been considered as a more modern DRR activity because urbanization is an element of modernity. This helped them to earn money when there were not enough jobs available in the study areas.

Discussion

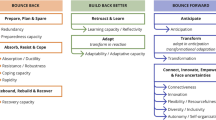

The objective of this research was to better understand how local coping mechanisms have changed in Bangladesh’s southwestern region, which is particularly vulnerable to disasters. This study showed significant changes in people’s DRR actions in relation to local EWSDP, local built environment, social capital formation during disasters, disaster-related training and awareness building, migration, and occupation, while prior studies did not appear to distinguish between conventional and contemporary strategies for coping or recognize recent changes in DRR behaviors. However, in term of EWSDP, supporting earlier studies (e.g., Azad et al. 2019; Garai 2017; Habiba et al. 2013a, b; Mallick et al. 2017; Sultana and Mallick 2015), this study also found that the coastal people of Bangladesh have some survival strategies which they characterized as indigenous coping mechanisms.

In contrast, this study demonstrated that a number of conventional coping strategies were combined with a variety of contemporary coping activities following Cyclone Aila, which seem to be more successful in dealing with calamities. For example, historically, local people made predictions about disasters based on changes in the weather in the area, unusual animal behavior, and river waves (Garai 2017). On the other hand, people currently get more trustworthy weather reports through mobile phones, the Internet, radio, and television (Ahsan and Khatun 2020; Ahsan et al. 2020; Roy et al. 2015).

Another important conclusion of this study was the progress of transportation. For instance, the upgrading of traditional boats with more modern equipment and the rise in popularity of motorcycles as a result of infrastructural development have both accelerated local people’s movement. Consistent with other research (e.g., Parven et al. 2020; Roy et al. 2023; Roy and Sony 2019), this study concludes that the conventional word-of-mouth warning mechanism has been supplanted by trained volunteers. This study also looked at how extensive training and awareness campaigns made locals more inclined to adopt modern DRR strategies, which decreased their reliance on traditional DRR activities.

In the context of the local building environment, this study reveals a significant shift towards the use of plastic pots for storing food and water during both normal and crisis situations. This finding is in contrast to earlier studies by Garai (2017), Roy et al. (2020), and Roy et al. (2023), which reported greater reliance on clay pots. It is worth noting that the use of plastic pots is seen as a form of DRR by those who employ them another positive development that has contributed to building resilience in the local community is the shift towards constructing brick houses instead of traditional earthen houses. Additionally, a change in the source of energy consumption has driven locals to adopt modern devices such as mobile phones and other electronics devices (Ahsan et al. 2020). In a line with Parvin et al. (2023) and Roy and Sony (2019), this study also shows that to stay safe during natural catastrophes like cyclones and floods, an increasing number of people are willing to take refuge in cyclone shelters constructed by the government. In contrast to the 1990s or earlier, when cyclones claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, these DRR initiatives have significantly decreased the number of fatalities and property damage in recent years. Nonetheless, some of the findings of the present study support the previous research about traditional DRR activities like planting coconut trees, areca, and fishtail palm trees as windbreaks and building their houses on elevated floors (Garai 2017; Rahman and Rahman 2015). The study underlines that the primary factor influencing these changes after Cyclone Aila’s effect was the supports provided by stakeholders from GO and NGOs.

As demonstrated by Bankoff (2015), Panday et al. (2021), Sanyal and Routray (2016), and Shoji and Murata (2021), this study confirms earlier studies on the function of social capital in DRR activities. The study found that in the study area, neighbors, kinship networks, and connections with local elites all made significant contributions during the three phases of disaster response. Emotional support from neighbors and kinship networks was particularly important. However, permanent migration weakened these networks, although sometimes migration had positive effects on local kin. For example, monetary and material support from solvent relatives outside the disaster-affected area had a significant impact on social capital outcomes.

In relation to the role of social capital during disasters, this study further highlights those women in the study area was more inclined to acquire loans from microcredit organizations (Nasreen et al. 2023), while male members tended to obtain credits from traditional money lenders known as Mahajan. These changes occurred in the area following the cyclone Aila. Based on this research, a majority of those interviewed have utilized these credits to build or renovate their homes, promote new income-generating activities, empower women, purchase eco-friendly energy equipment, and more. These actions have not only reduced their susceptibility to natural disasters but have also led to a shift away from traditional approaches to DRR. Notwithstanding, in a direction with Islam and Walkerden (2017) and Choudhury and Haque (2016), the findings also revealed that those with close links to local political elites had better access to facilities than those who did not have such connections.

This study indicates that the people who live near Bangladesh’s coast today have better knowledge and abilities when it comes to disaster preparedness. They are no longer only depending on conventional treatments because they now know about primary health care facilities and first aid. According to the study, new, scientifically grounded policies and programs have been introduced by both governmental and non-governmental groups (Islam 2018; Mallick et al. 2017; Parven et al. 2020, 2023; Roy et al. 2023; Roy and Sony 2019). The government has built cyclone shelters, embankments, and polders, while NGOs provide financial services, replacing traditional money lenders (Roy et al. 2023). Additionally, the government has implemented the CPP to reduce socioeconomic vulnerability in the coastal community (Habib et al. 2012). The construction of embankments has also improved food security in southwest coastal Bangladesh by replacing traditional cultivation techniques with modern ones (Mazumder and Kabir 2022). Coastal inhabitants have recently implemented additional modern DRR strategies, such as seasonal and permanent migration to nearby cities and districts (Biswas and Mallick 2021; Mallick 2014; Roy 2017; Roy et al. 2020; Subhani and Ahmad 2019). These interventions have led to the implementation of modern DRR strategies in the country which replaced the conventional ones.

The study’s findings are important because they shed light on how local disaster risk reduction efforts are evolving, which can help guide such programs. In fact, community involvement and the integration of local knowledge and needs into DRR have been emphasized by the SFDRR (2015–2030) (Kelman and Glantz 2015). Previous research revealed that reducing vulnerabilities in coastal areas would require outside interventions, like constructing cyclone shelters and homes resistant to cyclones (Habib et al. 2012; Ghani 2020). Scolobig et al. (2015) asserted, however, that these communities have adaptive qualities that lessen their vulnerability in the event of a calamity. According to the study’s findings, which corroborate these opinions, the locals in the study region used to participate in knowledge-driven and training programs offered by NGOs and the government, which lessened their vulnerabilities. Nevertheless, it’s critical to comprehend how local coping mechanisms change in order to effectively combine them with macro-level coping techniques. All the same, it is crucial to acknowledge that small village communities in Bangladesh were the subjects of this study. Thus, additional research involving a wide variety of socioeconomic groups is necessary.

Conclusion

This study examines the evolving disaster coping mechanisms and DRR strategies in the southwest coastal areas of Bangladesh. The research reveals that, following cyclone Aila in 2009, external stakeholders such as GOs and NGOs provided training and awareness programs, resulting in a fusion of modern disaster coping techniques with traditional DRR strategies. These changes have been observed not only in the built environment but also in local knowledge and wisdom. As a result, gender relations, social support networks, and local power dynamics have shifted, reducing the vulnerabilities of coastal communities. The study also highlights the existence of unethical social responsibilities in the local coastal areas, which requires further investigation to ensure sustainable and ethical relief management.

Additionally, the study’s researchers conclude that the study area’s growing local DRR policies mostly followed a contemporary systematic approach with apparent cohesiveness between policy and practice. These changes, in the opinion of SFDRR, are the result of a top-down strategy where community members’ local perceptions and wisdom have been given less importance. The authors of this study, therefore, want to draw the attention of policymakers to the need for ensuring that community members are included in substantial choices. This is due to the fact that barely any disaster management and preparedness strategies can be successful or sustainable without active participation from locals and without considering the local circumstances. The SFDRR advocates that since disaster coping strategies cannot be imposed from the top, professionals need to appreciate local coping mechanisms, as well as the recent changes that have occurred in DRR activities. The researchers would like to argue that both local and expert knowledge and strategies can be combined in more effectively dealing with natural and human-made disasters in settings such as southwestern Bangladesh.

This study suggests organizing consultations with local people to share expertise about DRR activities before establishing a DRR strategy. This can be one of the many strategies for combining both conventional and contemporary DRR operations. Disaster management would be unsuccessful without local involvement and awareness of local coping mechanisms that have developed in response to coping with disasters over generations. The likelihood that disaster coping techniques might shift in the future is exceptionally significant. In order to investigate the efficacy of utilizing both local efforts and external actions, the authors further suggest that future research of this kind be carried out on a greater geographic scale. Overall, the present study’s lack of quantitative measurements emphasizes the need for a follow-up cross-sectional, cross-generational, and longitudinal study to track changes in DRR activities in Bangladesh and globally more thoroughly.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

All names used in this paper are pseudonyms.

Although regular bottled mineral water costs about 0.24 USD per-liter in Bangladesh, the company supplied the water at a much lower cost in the context of disaster.

It can vary depending on the Government’s permission.

References

Adger WN, Crépin AS, Folke C, Ospina D, Chapin FS, Segerson K, Seto KC, Anderies JM, Barrett S, Bennett EM, Daily G, Elmqvist T, Fischer J, Kautsky N, Levin SA, Shogren JF, van den Bergh J, Walker B, Wilen J (2020) Urbanization, migration, and adaptation to climate change. One Earth 3(4):396–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2020.09.016

Ahmed B, Rahman MS, Sammonds P, Islam R, Uddin K (2020) Application of geospatial technologies in developing a dynamic landslide early warning system in a humanitarian context: the Rohingya refugee crisis in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Geomat Nat Haz Risk 11(1):446–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/19475705.2020.1730988

Ahsan MN, Khatun A (2020) Fostering disaster preparedness through community radio in cyclone-prone coastal Bangladesh. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 49:101752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101752

Ahsan R, Kellett J, Karuppannan S (2016) Climate migration and urban changes in Bangladesh. In: Shaw R, Attaur R, Surjan A, Parvin GA (eds) Urban disasters and resilience in Asia. Butterworth-Heinemann, Amsterdam, pp 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-802169-9.00019-7

Ahsan MN, Khatun A et al (2020) Preferences for improved early warning services among coastal communities at risk in cyclone prone south-west region of Bangladesh. Prog Disaster Sci 5:100065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100065

Azad MAK, Uddin MS, Zaman S, Ashraf MA (2019) Community-based disaster management and its salient features: a policy approach to people-centred risk reduction in Bangladesh. Asia-Pac J Rural Dev 29(2):135–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1018529119898036

Banglapedia (2021a) Map of Dakope Upazila [Map] https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Dacope_Upazila#/media/File:DakopeUpazila.jpg

Banglapedia (2021b) Map of Mongla Upazila. [Map]. https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Mongla_Upazila#/media/File:MonglaUpazila.jpg

Bankoff G (2015) “Lahat para sa lahat” (everything to everybody). Disaster Prev Manag 24(4):430–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-04-2014-0063

Behera JK (2023) Role of social capital in disaster risk management: a theoretical perspective in special reference to Odisha, India. Int J Environ Sci Technol 20(3):3385–3394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03735-y

Biswas B, Mallick B (2021) Livelihood diversification as key to long-term non-migration: evidence from coastal Bangladesh. Environ Dev Sustain 23(6):8924–8948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-01005-4

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG (ed) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press, California, pp 241–258

Call MA, Gray C, Yunus M, Emch M (2017) Disruption, not displacement: environmental variability and temporary migration in Bangladesh. Glob Environ Chang 46:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.08.008

Chen J, Mueller V (2018) Coastal climate change, soil salinity and human migration in Bangladesh. Nat Clim Chang 8(11):981–985. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0313-8

Choudhury MUI, Haque CE (2016) “We are more scared of the power elites than the floods”: adaptive capacity and resilience of wetland community to flash flood disasters in Bangladesh. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 19:145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.004

Garai J (2014) The impacts of climate change on the livelihoods of coastal people in Bangladesh: a sociological study. In: Filho WL, Alves F, Caeiro S, Azeiteiro UM (eds) International perspectives on climate change: Latin America and beyond. Springer, Cham, pp 151–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04489-7_11

Garai J (2017) Qualitative analysis of coping strategies of cyclone disaster in coastal area of Bangladesh. Nat Hazards 85(1):425–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2574-8

Ghani SM (2020) Traditional practices, communities’ aspirations, and reconstructed end products: analyzing the post-sidr reconstruction in the coastal region of Bangladesh. In: Chowdhooree I, Ghani SM (eds) External interventions for disaster risk reduction: impacts on local communities. Springer, Singapore, pp 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4948-9_5

Habib A, Shahidullah M, Ahmed D (2012) The Bangladesh cyclone preparedness program. A vital component of the nation’s multi-hazard early warning system. In: Golnaraghi M (ed) Institutional partnerships in multi-hazard early warning systems: a compilation of seven national good practices and guiding principles. Springer, Berlin, pp 29–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25373-7_3

Habiba U, Abedin MA, Shaw R (2013a) Disaster education in Bangladesh: opportunities and challenges. In: Shaw R, Mallick F, Islam A (eds) Disaster risk reduction approaches in Bangladesh. Springer, Tokyo, pp 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54252-0_14

Habiba U, Shaw R, Abedin MA (2013b) Community-based disaster risk reduction approaches in Bangladesh. In: Shaw R, Mallick F, Islam A (eds) Disaster risk reduction approaches in Bangladesh. Springer, Tokyo, pp 259–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54252-0_12

Haigh R, Amaratunga D (2010) An integrative review of the built environment discipline’s role in the development of society’s resilience to disasters. Int J Disaster Resil Built Environ 1(1):11–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17595901011026454

Hasan MR, Nasreen M, Chowdhury MA (2019) Gender-inclusive disaster management policy in Bangladesh: a content analysis of national and international regulatory frameworks. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 41:101324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101324

Islam MN (2018) Community-based responses to flood and river erosion hazards in the active Ganges floodplain of Bangladesh. In: Shaw R, Shiwaku K, Izumi T (eds) Science and technology in disaster risk reduction in Asia. Academic Press, pp 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812711-7.00018-3

Islam MR (2021) Climate change-induced migration in Bangladesh: existing research and research gap. In: Luetz JM, Ayal D (eds) Handbook of climate change management: research, leadership, transformation. Springer, Cham, pp 1793–1814. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57281-5_9

Islam MR, Hasan M (2016) Climate-induced human displacement: a case study of Cyclone Aila in the south-west coastal region of Bangladesh. Nat Hazards 81(2):1051–1071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-015-2119-6

Islam R, Walkerden G (2014) How bonding and bridging networks contribute to disaster resilience and recovery on the Bangladeshi coast. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 10:281–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.09.016

Islam R, Walkerden G (2017) Social networks and challenges in government disaster policies: a case study from Bangladesh. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 22:325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.011

Kelman I, Glantz MH (2015) Analyzing the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction. Int J Disaster Risk Sci 6(2):105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-015-0056-3

Khalil MB, Jacobs BC, McKenna K, Kuruppu N (2020) Female contribution to grassroots innovation for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Climate Dev 12(7):664–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1676188

Khalil MB, Jacobs BC, McKenna K (2021) Linking social capital and gender relationships in adaptation to a post-cyclone recovery context. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 66:102601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102601

Lee DW (2019) Local government’s disaster management capacity and disaster resilience. Local Gov Stud 45(6):803–826. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2019.1653284

Lincke D, Hinkel J (2021) Coastal migration due to 21st century sea-level rise. Earth’s Fut 9(5):e2020EF001965. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020EF001965

Lumbroso D, Brown E, Ranger N (2016) Stakeholders’ perceptions of the overall effectiveness of early warning systems and risk assessments for weather-related hazards in Africa, the Caribbean and South Asia. Nat Hazards 84(3):2121–2144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2537-0

Malalgoda C, Amaratunga D (2015) A disaster resilient built environment in urban cities. Int J Disaster Resil Built Environ 6(1):102–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDRBE-10-2014-0071

Mallick B (2014) Cyclone-induced migration in southwest coastal Bangladesh. ASIEN 130:60–81

MallickB AB, Vogt J (2017) Living with the risks of cyclone disasters in the south-western coastal region of Bangladesh. Environments 4(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments4010013

Maps of the World (2016) Maps of Bangladesh. [Map]. Small administrative map of Bangladesh. http://www.maps-of-the-world.net/maps-of-asia/maps-of-bangladesh/

Mazumder MSU, Kabir MH (2022) Farmers’ adaptations strategies towards soil salinity effects in agriculture: the interior coast of Bangladesh. Clim Policy 22(4):464–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.2024126

Nagel CL, Carlson NE, Bosworth M, Michael YL (2008) The relation between neighborhood built environment and walking activity among older adults. Am J Epidemiol 168(4):461–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn158

Nasreen M, Mallick D, Neelormi S (2023) Empowering women to enhance social equity and disaster resilience in coastal Bangladesh through climate change adaptation knowledge and technologies. In: Nasreen M, Hossain KM, Khan MM (eds) Coastal disaster risk management in Bangladesh: vulnerability resilience, 1st edn. Routledge, London, p 540. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003253495-14

Nowreen S, Jalal MR, Shah AKM (2013) Historical analysis of rationalizing South West coastal polders of Bangladesh. Water Policy 16(2):264–279. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2013.172

Panday S, Rushton S, Karki J, Balen J, Barnes A (2021) The role of social capital in disaster resilience in remote communities after the 2015 Nepal earthquake. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 55:102112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102112

Parven A, Pal I, Wuthisakkaroon C (2020) Climate smart disaster risk management for a resilient community in Satkhira, Bangladesh. In: Pal I, von Meding J, Shrestha S, Ahmed I, Gajendran T (eds) An interdisciplinary approach for disaster resilience and sustainability. Springer, Singapore, pp 477–496

Parvin GA, Dasgupta R, Abedin MA et al (2023) Disaster experiences, associated problems and lessons in southwestern coastal Bangladesh: exploring through participatory rural appraisal to enhance resilience. Sustain Resilient Infrastruct 8:223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/23789689.2022.2138165

Rahman M (2021, 18 June 2021) Mongla Upazila. Banglapedia. https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Mongla_Upazila. Accessed 16 Sept

Rahman MA, Rahman S (2015) Natural and traditional defense mechanisms to reduce climate risks in coastal zones of Bangladesh. Weather Clim Extrem 7:84–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wace.2014.12.004

Roy AKD (2017) An investigation into the major environment and climate change policy issues in southwest coastal Bangladesh. Int J Clim Change Strateg Manag 9(1):123–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-03-2016-0028

Roy T (2019) Disaster risk reduction interventions in Bangladesh: a case study of selected villages of southwest region. J Asiat Soc Bangladesh 64(1):43–69

Roy T, Sony MMAAM (2019) Social structural changes in post-disaster area from marxist point of view: reflections from Dacope, Khulna, Bangladesh. NIU Int J Hum Rights 6(1):3–13

Roy C, Sarkar SK, Åberg J, Kovordanyi R (2015) The current cyclone early warning system in Bangladesh: providers’ and receivers’ views. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 12:285–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.02.004

Roy T, Chandra D, Sony MAAM, Rahman MS (2020) Impact of salinity intrusion on health of coastal people: reflections from Dacope upazila of Khulna district, Bangladesh. Khulna Univ Stud 17(1 and 2):57–66

Roy T, Hasan MK, Sony MMAAM (2022) Climate change, conflict, and prosocial behavior in Southwestern Bangladesh: implications for environmental justice. In: Madhanagopal D, Beer CT, Nikku BR, Pelser AJ (eds) Environment, climate, and social justice: perspectives and practices from the Global South. Springer, Singapore, pp 349–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1987-9_17

Roy T, Nasreen M, Hasan MK, Sony MMAAM (2023) Community priorities in disaster risk reduction interventions: a critical perspective from Bangladesh. In: Nasreen M, Hossain KM, Khan MM (eds) Coastal disaster risk management in Bangladesh, vol 1. Routledge, London, pp 335–355. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003253495-21

Sahin G, Cabuk SN, Cetin M (2021) The change detection in coastal settlements using image processing techniques: a case study of Korfez. Environ Sci Pollut Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16660-x

Sammonds P, Shamsudduha M, Ahmed B (2021) Climate change driven disaster risks in Bangladesh and its journey towards resilience. J Br Acad 9(s8):55–77. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/009s8.055

Sanyal S, Routray JK (2016) Social capital for disaster risk reduction and management with empirical evidences from Sundarbans of India. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 19:101–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.08.010

Scolobig A, Prior T, Schröter D, Jörin J, Patt A (2015) Towards people-centred approaches for effective disaster risk management: Balancing rhetoric with reality. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 12:202–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.01.006

Scott Z, Few R (2016) Strengthening capacities for disaster risk management I: insights from existing research and practice. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 20:145–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.04.010

Shaw R (2012) Chapter 1 Overview of community-based disaster risk reduction. In: Shaw R (ed) Community-based disaster risk reduction, vol 10. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2040-7262(2012)0000010007

Shaw R, Islam A, Mallick F (2013) National perspectives of disaster risk reduction in Bangladesh. In: Shaw R, Mallick F, Islam A (eds) Disaster risk reduction approaches in Bangladesh. Springer, Tokyo, pp 45–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54252-0_3

Shoji M, Murata A (2021) Social capital encourages disaster evacuation: evidence from a cyclone in Bangladesh. J Dev Stud 57(5):790–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1806245

Sony MMAAM (2018) Indigenous coping mechanism and role of religion in disaster management: an evidence from dacope (Publication Number 141642) Khulna University, Khulna

Subhani R, Ahmad MM (2019) Socio-economic impacts of cyclone Aila on migrant and non-migrant households in the Southwestern coastal areas of Bangladesh. Geosciences 9(11):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9110482

Sultana Z, Mallick B (2015) Adaptation strategies after cyclone in Southwest Coastal Bangladesh—pro poor policy choices. Am J Rural Dev 3(2):24–33. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajrd-3-2-2

Sutton SA, Paton D, Buergelt P, Meilianda E, Sagala S (2020a) What’s in a name? “Smong” and the sustaining of risk communication and DRR behaviours as evocation fades. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 44:101408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101408

Sutton SA, Paton D, Buergelt P, Sagala S, Meilianda E (2020b) Sustaining a transformative disaster risk reduction strategy: grandmothers’ telling and singing tsunami stories for over 100 years saving lives on Simeulue Island. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(21):1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17217764

United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) (2009) Terminology on disaster risk reduction. UNISDR. https://www.unisdr.org/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf

Walch C (2019) Adaptive governance in the developing world: disaster risk reduction in the State of Odisha, India. Clim Dev 11(3):238–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2018.1442794

Zulfadrim Z, Toyoda Y, Kanegae H (2019) The integration of indigenous knowledge for disaster risk reduction practices through scientific knowledge: cases from Mentawai islands, Indonesia. Int J Disaster Manag 2(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.24815/ijdm.v2i1.13503

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to sincerely thank all participants.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Debrecen. No funds, grants, or other support were received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and formal analysis were performed by the first author. Third author performed key Supervision and data collection. All authors have contributed to manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest with any person or financial institutions.

Ethical approval

The researcher has followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and no Human participant have involved in clinical trials.

Informed consent

An informed oral consent has taken each of respondents involved in this research.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sony, M.M.A.A.M., Hasan, M.K. & Roy, T. Coping with disasters: changing patterns of disaster risk reduction activities in the southwestern coastal areas of Bangladesh. SN Soc Sci 3, 202 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00791-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published: