Abstract

The vulnerability of smallholder farmers to multidimensional poverty in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa was assessed, using the Alkire Foster multidimensional poverty index developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative and aligned to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The findings show that the deprivation indicator ranges from 5 to 90%, revealing that access to a flush toilet facility is an imperative factor towards the households’ standard of living (SDG11). Also, 66% and 55% were deprived of food security (SDG2) and education (SDG4), respectively. The probit analysis result revealed that gender, remittances, crop diversification (CDV), education, seasonal farming and market outlets significantly influence the multidimensional poverty and vulnerability poverty of rural households in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. For instance, factors such as household size showed that an additional unit increase in the size of a household would result in a 5% increase in the chances of the household’s vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. Likewise the extension contact, a unit increase resulted in 49% in the households’ vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. The study suggests that policies related to improving education, increasing CDV, promoting farmer groups and the effectiveness of extension contact, and increasing market stability for sales of farm products could contribute to reducing the multidimensional poverty level and the vulnerability of households.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Poverty reduction remains a primary goal for policy development in developing countries around the world, and it is consistent with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to eliminate global poverty in all forms by 2030 (UN 2014). According to the World Bank reports (2020), the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in massive reversals to previous advances in poverty alleviation, with additional 150 million people projected to be living in poverty by the end of 2021, globally. This is a growing concern for many developed and developing countries, as the goal of alleviating global poverty by 3% now seems harder, with the number of people worldwide living below the international poverty line falling from 741 to 689 million (OPHI and UNDP 2020). The alleviation of poverty has increasingly been investigated through a multidimensional approach to establishing poverty alleviation policies, strategies and programs (Gebrekidan et al. 2021). Even though poverty is a global social issue, it is the most difficult and pressing public concern in many developing countries, particularly countries in Sub-Saharan Africa where a significant proportion of residents live in poverty, precisely around 36% of the population is considered to be poor (Bicaba et al. 2017; Alkire and Robles 2017; Motuna et al. 2020).

In South Africa, about 39.8% of the population lives under intense multidimensional poverty, with 12.2% of the population reported to be vulnerable to multidimensional poverty, and 39.5%, 13.1%, 47.4% contributing to deprivations related to health, education and standard of living, respectively (OPHI and UNDP 2020). To reduce the poverty levels in South Africa, a National Development Plan (NDP) was developed to enhance the development of the country through a holistic approach linked to the SDGs to achieve synergies across multiple development goals (National Planning Commission 2013; Cumming et al. 2017). This aim is to address issues such as job creation, inequality, water security, food security, climate change, disaster risk reduction, infrastructure development, human settlements, and health challenges, as well as the sustainable use of natural resources (Cumming et al. 2017). Relative to the NDP, the SDGs highlighted the need to end hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture (FAO 2016). Poverty in terms of food security indicates that around 26% of South Africans are food insecure and 28% are at the edge of facing food insecurity (Tibesigwa and Visser 2016). While poverty assessments have been carried out vastly at the country level, a more rigorous assessment at the multidimensional level has been reported to force provincial policy development necessary to enhance poverty alleviation and improve rural livelihoods (Mushongera et al. 2017).

The Eastern Cape Province remained consistently ranked in the top two positions of poverty-stricken (67.3%) provinces after Limpopo, in South Africa (Statistics South Africa 2017). According to the findings of Mthethwa and Wale (2021), the Eastern Cape province represent one of the two provinces facing chronic poverty and severe food insecurity which affects the livelihood standards of rural households. Among the causes of the rising level of poverty in the Eastern Cape province is the high rate of unemployment (Ngumbela et al. 2019). The report from World Bank (2018), highlights that the Eastern Cape alone has 20 poorest municipalities, indicating the post-effect of the apartheid era which caused a decline in developments in homelands. Despite the high rate of poverty in the province, the efforts of the government are committed to promoting anti-poverty measures towards improving the welfare of the people and also achieving the SDGs through various means such as improvement in skills and education and increasing social transfers. The social transfers contributed to improved health and increased education levels of the people thereby reducing the poverty headcount rate and declining the poverty gap by 7.9% and 29.5% in South Africa (World Bank Group 2018). To address the dimensional poverty of the people, an innovative approach that separates different types of deprivation is required, hence a multidimensional poverty approach was considered for this study.

A significant shift in the measurement of poverty is the vulnerability to multidimensional poverty, which describes the increased tendency of a household to become poor (Feeny and McDonald 2016). Several studies have also measured the vulnerability to multidimensional poverty using various approaches in the literature (Azeem et al. 2018). While the approach has been used extensively in other countries, there is an existing gap in the body of knowledge where traditional poverty analysis has mostly been adopted rather than using the multidimensional poverty approach to investigate the multiple deprivations in rural areas that are facing abject poverty such as the selected study area, Eastern Cape. The other important research gap identified was that previous studies carried out in South Africa have relied on the national data which only provides the overall overview of the country, thereby excluding the possibility of examining the grassroots cause of the growing poverty level of the households, particularly in the rural areas. The fact that the understanding of a grassroots cause is the most instrumental strategy for generating and arriving at a sustainable solution creates the need to examine the multidimensional poverty of rural households at the provincial level in South Africa (Mkhize and Mutereko 2022). Against these backdrops, this current study investigates the multidimensional poverty of households in the Eastern Cape province, with many linkages to the SDGs’ poverty goals. The results of this research will contribute to the body of literature by presenting the determinant factors of the multidimensional poverty and vulnerability levels of the households, as well as to help understand the important policy recommendations that are necessary to improve the livelihood of the rural households in the study area.

Empirical literature

Multidimensional poverty approach

A multidimensional approach has been developed to analyse a wide range of multiple poverty levels involving severe deprivation of basic human needs, such as health, education and living standards, which are not captured by the monetary poverty approach (Alkire et al. 2017) Previous studies in the literature have employed the multidimensional poverty approach proposed by Alkire-Foster in various countries, regions and sectors (Alkire and Seth 2015; Dehury and Mohanty 2015; Alkire et al. 2017; Megbowon 2018; Santos and Villatoro 2018; Dagunga et al. 2021). Similarly, other studies in the literature also employed multidimensional poverty with much focus on inequality, health, education, vulnerability, and rural poverty in developing and developed countries (Leisher et al. 2013; Kuntz et al. 2016; Krishnamurthy et al. 2014; Mert and Kadioglu 2016; Vukojevic et al. 2017). It is important to note that most of these definitions of poverty involve different dimensions. The above studies highlight the importance of the multidimensionality of poverty as it combines the entirety and relative poverty. While poverty is assessed on a broader dimension consisting of some indicators, previous studies on poverty in developing countries like South Africa mostly focus more on the uni-dimensional monetary poverty using income or consumption levels, thereby excluding other important aspects such as child poverty.

Anti-poverty measures in South Africa

In South Africa, there is increasing recognition of government policies initiated as anti-poverty measures to tackle the rising poverty levels of several households across the nation. Given the strategy of reducing poverty in South Africa which was estimated to be between 40 and 56% of the total population in 2015 (Hirschl et al. 2023), anti-poverty measures such as social capital, employment creation, strengthening food security, Basic Income Grant, Family Poverty Grant, Social Auxiliary Workers scheme, Scale-up of social welfare, Massive Food Production Programme (MFPP) (Hebinck 2014) and other development programmes have been established to reduce poverty in the country (some of which are targets set for 2030). Another anti-poverty policy that exists to combat poverty is the ‘South African land expropriation without compensation, found in Section 25 of the South African Constitution’, to reduce the number of people living below the poverty line as lack of access to land was identified as one of the factors contributing to multidimensional poverty (Mubecua and Mlambo 2021). While significant anti-poverty mechanisms play a role in poverty reduction and in improving the welfare of vulnerable rural households, there is still inadequate information and evidence on how these strategies reduce multidimensional poverty as well as the vulnerability of the households to multidimensional poverty in South Africa. Therefore, the significance of this study is to contribute a novel insight into the determinants of multidimensional poverty and how this direct impact the vulnerability of rural households to multidimensional poverty. This analysis provides critical policy recommendations that help to evaluate the existing antipoverty measures against the continental and global poverty eradication targets such as the Agenda 2063 and the SDG goals.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area and data collection

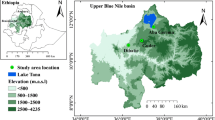

This study was conducted in the King Sabata Dalindyebo and Nyandeni local municipalities which fall under the OR Tambo District Municipality, representing the local municipalities in the Mthatha River basin in Eastern Cape province (Fig. 1). The district is functionally rural, characterized by low educational levels and predominantly an agricultural-producing area (Socio 2017). Demographically, it has been documented in the literature that the dominant age group is 10–14, representing 11.5% of the total provincial population of 6667 million people. The majority of the population are females (52.8%), whilst males represent 47.8% (Statistics South Africa 2022). The Eastern Cape’s official unemployment rate was 47.4% in the third quarter of the 2020/2021 fiscal year. Considering that the study area is ranked the highest official and expanded unemployment rates in the nation, the Eastern Cape has been dubbed the poorest province in South Africa. This, directly and indirectly, reflects the standard of livelihood in the study area and therefore proves that it is essential to investigate and assess the multidimensional poverty and vulnerability to poverty of rural households.

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed for data collection. A purposive sampling technique was used to separate the catchment into four regions, within the Mthatha River. These are the upper region, the peri-township region, the lower region and the coastal region. In each of the areas, ten villages were chosen at random, of which 11 respondents were randomly chosen in each village based on the consent of the interviewees. In total, 440 households were interviewed but only 402 were considered credible for analysis due to some uncompleted questionnaires. The sample size was determined following Slovin’s procedure (Tejada and Punzalan 2012), expressed as:

where n = sample size, N represent the total population and e is the margin of error. The sample size was determined using a 95% confidence level, with a margin error of 5%.

For this study, N = 6,712,276, e = 0.05

where n = 400. This indicates that the study’s minimum sample size should 400.

Unlike the data from the 2001 population census, which most studies have used to analyze the multidimensional poverty in South Africa (for example Megbowon 2018), this study employed more recent primary data in order to closely assess the multidimensional poverty situations of rural households at a provincial level. The study employed a quantitative method for the collection of data using a survey questionnaire. The survey questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated to a local language (isiXhosa), as it is assumed that people feel more at ease speaking to others in their language, which improves the accuracy of information obtained and the survey’s dependability. The important sections of the questionnaire focus on respondents’ use of irrigation, farm activities, source of finance, water access and challenges associated with household food security. The questionnaire’s other major component was designed to find out about households’ demographic profiles and consumption patterns.

Empirical technique

Alkire–Foster multidimensional poverty index (MPI)

The MPI was generated by using the Alkire–Foster multidimensional poverty approach to investigate the various deprivations that subject people to different poverty levels. While there has been extensive use of a monetary measure methodology as an official poverty indicator (Roelen et al. 2012), many researchers as well as some policymakers consider poverty as a complex phenomenon that cannot be entirely measured by income or consumption expenditures but are better analyzed using the multidimensional poverty indicators (Tran et al. 2015; Roelen 2017). The application of multidimensional poverty was supported by the findings of Kim (2019) who emphasized the need to go beyond the traditional monetary poverty measure not only to understand the dynamics of child poverty and well-being but also to better inform policy. For this study, the multidimensional poverty indicator was preferred to capture the SDGs targets which align with the objectives of this study and the non-monetary indicators that were analyzed in this study.

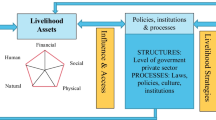

The MPI framework as shown in Fig. 2, is useful for presenting the magnitude and details of poverty situations of households and was applied to measure household poverty levels which are directly linked to the first goal of the SDGs, that is, putting an end to all forms of poverty everywhere around the world. The MPI framework consists of nine indicators (d) (9 indicators were preferred as they better suit the South African case study as explained by Mushongera et al. (2017) and grouped into four dimensions (T), which were equally weighted, with the indicators also assigned equal weights based on the weight of the dimensions which is attached to the indicator j (j equals 1, 2, …, d), as showing in Eq. (3).

Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (OPHI) (Alkire et al. 2020)

In Table 2, the study links each indicator from the MPI framework to each related goal of the SDGs. For example, goal number 4 of the SDGs was linked to the education dimension. The deprivation cut-offs for the nine indicators are presented in Table 2. We determine the poverty incidence (multi-dimensional Headcount ratio [H]) and intensity (A), which is the average deprivation score of multi-dimensionally poor persons, using Alkire and Foster’s (2007, 2011) methodology. According to OPHI (2021), a household is considered multidimensionally poor if the household is found to be deprived of at least 1/3 of the weighted indicators, meaning the household poverty cut-off (k) is equal to 33.33%. The incidence of poverty, often known as the headcount ratio (H), is the fraction of the population that is multidimensionally poor. This is calculated as;

where n represents the number of poor households and t denotes the total number of households.

The intensity of poverty, on the other hand, is defined as the average proportion of indicators in which poor individuals are deprived (A). The intensity of poverty was calculated as;

where c denotes the overall weighted deprivations experienced by the poor household.

The MPI is calculated by multiplying incidence and intensity:

The probit model analysis

This study employed the probit model to estimate the determinants of multidimensional poverty in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa. As described earlier, a poor household is considered to be deprived of at least 33% of the weighted indicators and therefore takes the value of 1 and 0 if otherwise. We first take \(\hat{\dot{y}}\) to be an underlying continuous latent variable that causes a household to be poor, as the dependent variable is dichotomous and a household is either poor or not. The latent variable could be described as;

where \(x\) represent the vector of the household socio-economic and institutional variables assumed to influence households’ multidimensional poverty. Therefore,

The probit model is then expressed as;

where F represent the standard normal cumulative distribution function which can be written as;

For the poverty vulnerability estimates, we followed the OPHI approach (OPHI 2021). For every person with a score c between 0.2 and 0.3, such a person is identified as part of a group of people who are still vulnerable to multidimensional poverty. Also, every individual with a score of 0.5 or more is classified as (both MPI poor) living in severe multidimensional poverty. The MPI statistics for a final cutoff of 40% are also reported. Subsequently, the determinant factors influencing the vulnerability of the grouped individuals were performed, following a similar process in Eqs. (7–9).

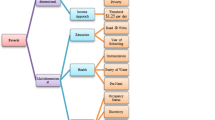

Description of variables and a priori expectations of the determinants of multidimensional poverty and drivers of household vulnerability to poverty

This study followed the approach of Dagunga et al. (2021) to determine the socio-economic and institutional variables that have the probability to influence the multidimensional poverty level of households in the study area. In Table 1, the socio-economic variables that were generated included, household age, household size, household gender, non-farm activity, remittances and engagement in seasonal farming. For the institutional variables, extension contact, market outlet, and government credit support were considered.

As shown in Table 1, the age of respondents which was measured in years showed a mean value of 45 years for the total population sample. The respondent’s age could have a mixed effect on multidimensional poverty in South Africa. This could be due to the fact that an individual’s age does not necessarily translate to poverty but instead the number of assets owned by the household and the kind of income-generating activities they are involved in. Therefore, a negative or positive sign could be reported. For household size, an average of three individuals per household was reported, indicating an expected decrease in multidimensional poverty, depending on the household characteristics in terms of employed vs unemployed, as opined by Dagunga et al. (2021). In addition, a household with more individuals could translate to faster usage of household facilities (such as electricity, and water), and cause overcrowded dwellings. The gender of the household head could also have a negative or positive effect on the probability of multidimensional poverty. Given that 63% were male, there is a higher possibility that a negative influence could be revealed because the household with more manpower could have more labourers to work and generate more resources thereby improving the livelihood standards of the households.

There is an expected positive or negative result from the non-farm activity variable as the magnitude of the influence could be based on the characteristics of the activity in question. Regardless of the influence, a marginal level of non-farm activity is expected to significantly improve household livelihoods. Households who receive remittances are expected to experience a decline in their multidimensional poverty level, indicating that a negative effect is expected. Likewise, engaging in crop diversification (CDV) is expected to yield a negative influence on household multidimensional poverty. Seasonal farming and market outlet were other variables included in the poverty model. These variables are expected to influence the probability of being poor, either positively or negatively. This is because seasonal farming helps farmers to grow climate-specific crops, with some crops requiring more water while some less water, to avoid issues related to crop loss and a decrease in yields. Also, market availability for sales of farm products is expected to negatively influence the likelihood of households being poor. Credit access was postulated to negatively affect households’ tendency of becoming poor as credit allows households to invest in several income-generating businesses. This aligns with the study of Olarinde et al. (2020) who also found that credit access, whether formal or informal significantly decreases the probability of households becoming poor in Nigeria.

Lastly, the consumption per capita expenditure of the respondents could reveal a negative or positive outcome, as household consumption status varies based on several factors such as employment, household size and so on.

Multidimensional poverty and SDGs

Table 2 shows a list of the indicators, the respective weights based on equal weighting of dimensions as well as the related SDGs. For example, the housing indicator directly fits into SDG11 which reflects the importance of providing adequate, safe, and affordable housing, which serves as a means to end poverty of all forms.

Other indicators such as the sanitation under the standard of living dimension directly fit into SDG6, which explains the need to achieve adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all by 2030. Similarly, the water MPI indicator also fits into SDG6, highlighting the need to achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water. Aligning the indicators to the SDGs is important for understanding the progress achieved in the delivery of these services which is key for improving livelihoods from a policy perspective especially given that wide gaps still exist in the provisions of housing and basic services in South Africa (Mushongera et al. 2017).

Results and discussion

The results in Table 3 present the estimated percentage of people facing deprivation in each of the nine indicators.

Table 3 revealed that the deprivation percentages are quite similar among some of the indicators although varies for other indicators. The result shows that the households in the study areas experience substantial deprivation in access to flush toilets. Access to the flush toilet which is generally used to measure the living standard of people has been used as an indicator to measure concerns related to water and sanitation (Alkire and Santos 2014). Overall, the standard of living is the largest contributor to the MPI in the study area which varies between different indicators. This is consistent with the study of Megbowon (2018) who found that the standard of living of households in Eastern Cape province contributed massively to the MPI and was significantly influenced by access to electricity and education attainments.

The households also suffer huge deprivation in dwellings in terms of people per room, estimated to be over 63%. The households are better off in deprivations associated with electricity, as result shows a deprivation as low as 33.75%. Similar to the findings of this study, high deprivations were also found in the study of Espinoza-Delgado and Klasen (2018) although found low deprivations for electricity and water. The results also show a large deprivation in the area of access to water resources in the study area, with results estimated to be 60.25%. This is not surprising as water is generally a scarce commodity in South Africa, given the country’s semi-arid land characteristics (Adetoro et al. 2021). A very minimal percentage of households (5%) suffer deprivation in assets in terms of access to mobile phones, televisions and radio. Access to communication tools like phones and TV has experienced some growth in the last few years owing to the social wage implemented by the South African government, with expanded public works programs forming a section of the social wage (Stats 2017).

Deprivations from the perspective of household food and nutrition security showed that around 66.25% of the respondents were deprived of food at some specific point in time. In order words, the percentage of households who skipped a meal was 66.25% (in a month), indicating that they could be living below the poverty threshold as set by the World Bank (2009). Similar to the study of Rogan (2016), the food nutrition indicator contributes nearly the highest to the multidimensional poverty in South Africa. According to Dagunga et al. (2021), when at least a household skips a meal, it could translate to not having enough capacity to provide food in terms of the financial status of the household. This, in turn, also affects the capacity of such a household to participate effectively in society. In addition, this indicates the propensity of households to be susceptible to violence, and it could as be translated to “living in marginal or fragile environments” (Dagunga et al. 2021).

The rate of unemployment and low enrolment in educational institutions also contribute a significant amount to multidimensional poverty, by 15% and 55%, respectively. The increase in unemployment could be associated with the increase in population, which has been found to have a positive influence on household poverty. This is consistent with the study of Aloosh et al. (2019) who found that an increase in population caused an increase in unemployment and household poverty levels in Iran. The findings of this study agree with that of Fransman and Yu (2019) who found that unemployment and years of schooling were the indicators that contributed the most to the multidimensional poverty in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces of South Africa.

Determinants of multi-dimensional poverty

The results in Table 4 present the factors that drive the MPI of rural households. Factors that significantly influence households to experience multidimensional poverty or not include gender, non-farm income, remittances, CDV, seasonal farming and market outlet.

The result shows that gender is an important variable in explaining the multidimensional poverty of households in the study area. Gender is negative and statistically significant in influencing the MPI, which indicates that male-headed households are more likely to experience less multidimensional poverty than female-headed households. The study of Cheteni et al. (2019) emphasized that gender plays a significant role in household decision-making and consequently can affect the level of multidimensional poverty in rural households. The marginal effect of the gender variable implies that a 1% increase in male-headed households among the population could decrease multidimensional poverty by 3%.

The marginal effect of non-farm income reasonably reduces household poverty. A unit increase in non-farm income is estimated to reduce multidimensional poverty by around 0.06. As depicted by Danso-Abbeam et al. (2020), non-farm income significantly improves smallholder farmers’ welfare through poverty reduction. Thus, increasing off-farm employment opportunities could serve as a feasible way for alleviating poverty in rural areas.

Remittances which are a form of financial support from relatives of various households showed a negative and significant effect on household multidimensional poverty. This implies that households that receive financial support from relatives are more likely to reduce deprivation to multidimensional poverty. Several studies have reported the significance of remittances in contributing to household poverty reductions, through an increase in household spending, especially in rural areas (Awuse et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2019). The marginal effect of remittances shows that a unit increase in foreign monetary inflow reduces households’ multidimensional poverty.

Crop diversification offers several benefits to rural households such as improved income from agricultural activities, with results showing a negative association with household multidimensional poverty. This indicates that households who practice crop diversification are more likely to reduce their poverty level and minimize deprivations of various basic amenities. Engagement in crop diversification has been reported to generate more farm income for farmers and improves household resilience against climate change for smallholder farmers who are in poverty (Ponce 2020), thereby can be considered a key factor for improving the livelihoods of rural households. From a marginal effect perspective, the result shows that increasing crop diversification could further contribute to declining multidimensional poverty. This is consistent with the study of Tesfaye and Tirivayi (2020) who found that increased crop diversity in Uganda increased household welfare through increased productivity and farm income.

Seasonal farming is a climate-smart agricultural system that allows farmers to adapt to climate changes which in turn produces high yields and increase productivity. Our empirical findings show that seasonal farming practices tend to reduce household multidimensional poverty in the study area. Climate change causes variability in precipitation and temperature which may affect crop growth and decrease yields if not planted during the right season. Some crops are more tolerant than others to certain types of stresses, and at each phenological stage, different types of stresses affect each crop species in different ways, which is the reason for choosing a suitable season for farming (Eshetu et al. 2021). Likewise, the marginal effect of seasonal farming produced a negative influence on poverty reduction, indicating that increasing the period of practising seasonal farming would result in a reduction in multidimensional poverty and an improvement in household livelihoods. Thus, seasonal farming can be considered as a means for increasing yield, farm income and reducing multidimensional poverty of rural households.

The empirical result shows that market outlet contributes to the reduction in multidimensional poverty, with a negative and significant of 1%. There is a strong correlation between market access and farm household income, which implies that farmers who can channel their products to markets could significantly reduce their multidimensional poverty and improve their livelihoods. Similar to findings from the literature, Nandi et al. (2021) found that market access contributes to poverty reduction for rural households, owing to an increase in farm income generated as a result of reliable market access. An increase in the market outlet by a unit would lead to around a 0.06 decrease in multidimensional poverty of the households.

Determinants of vulnerability to multidimensional poverty

The results in Table 5 presents the factors that determine the vulnerability of rural household to multidimensional poverty. The estimated results also include the marginal effect of the significant factors on vulnerability to multidimensional poverty of the rural households in the study area.

Household size was statistically significant and positively contributes to household vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. This implies that a larger household size would lead to a more vulnerable household to multidimensional poverty. This is most likely because larger homes require more foods to feed all of the household members, putting a strain on household income. The result of this study is consistent with that of Gebrekidan et al. (2020) who found that the size of a household positively correlates with vulnerability to poverty, implying that the larger the household the more vulnerable such household would be to multidimensional poverty. This is also reflected in the marginal effect of household size on vulnerability to multidimensional poverty, with results showing that a unit increase in household size would result in a 0.05 increase in the chances of the household being vulnerable to multidimensional poverty.

Consistent contact with extension agents shows a negative and significant association with vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. Contact with extension agents provides real-time information necessary for improving farm productivity and increasing farm income. Similar to our findings, Ambaye et al. (2021) revealed that household contact with extension agents was statistically significant and negatively associated with the household’s vulnerability to multidimensional poverty in Ethiopia. The marginal effect indicates that as contact with extension agents increases by one unit, the vulnerability to multidimensional poverty decreases by 0.49. Remittance shows a negative and significant relationship with household vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. This indicates that foreign incomes received by farm households as remittances directly contribute to a reduction in the vulnerability of households to poverty. This is possible because household that receives constant remittances from relatives abroad often invest in businesses that generate a sustainable income flow for the rural household. Similar to the study of Ekanayake and Moslares (2020), the remittances variable was found to have a negative influence, suggesting that workers’ remittances seem to reduce the poverty rates in Latin America. Likewise, the marginal impact may increase the multidimensional poverty of rural households if not used to improve livelihoods. Findings from the literature show that remittance has a negative association with poverty vulnerability and poses the possibility of reducing multidimensional poverty (Hagen-Zanker and Himmelstine 2016).

CDV is an important variable in the mitigation of multidimensional poverty in a rural household. The results show that CDV may contribute to a reduction in household vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. The negative association could be ascribed to multiple incomes that can be obtained from growing various crops which provides households with improved consumption expenditure and enhanced livelihood standards. In line with the study of Feliciano (2019), diversification in crop production aligns well with the SDGs, particularly in the aspect of poverty alleviation for farm households. Similarly, the marginal effect of involvement in CDV reveals that farmers who plant diverse crops are more likely to further reduce their vulnerability to multidimensional poverty by 24%.

The farm-based association is statistically significant and poses a negative association with vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. This implies that participating in the farm-based organization could provide farm households with important information necessary for improving farm productivity and subsequently improving farm income, hence reducing household vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. Empirical evidence available in the literature such as Ojo et al. (2021) posits that involvement in farm organization provides farmers with some important information that helps farmers’ innovations, production and marketing, through social and farmer-to-farmer networks. This information can also enhance farmers’ decision-making and thus eliminate potential vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. Other aspects of belonging to a farm-based organization could be linked to the opportunity to be exposed to a saving group (such as a farmers’ cooperative organization) which has been reported to contribute to a lower probability of being poor compared to those who do not belong to any organization or a saving group. This is because savings serve as a cushioning mechanism that encourages farmers to invest in other activities as well as respond to unexpected events that could threaten the financial stability of rural households (Dagunga et al. 2021).

The years of education of the household head had negative coefficients supporting the hypothesis that increased years of education decrease the probability that a household will be vulnerable to multidimensional poverty. Similarly, the marginal effect result revealed that a unit increase in years of education in the rural household would lead to a 0.48 reduction in vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. This points to the direction of a need for an increase in education training for farm households which could allow an enhanced application of new technologies to improve farm income and livelihoods. This corroborates the findings of Padda and Hameed (2018) who found that education reduces multidimensional poverty in Pakistan.

Conclusions

This study investigated the multidimensional poverty of rural household dwellers in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Using cross-section data collected from 402 households in ten villages in Eastern Cape Province, in South Africa, the study used the Alkire Foster multidimensional poverty index developed by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) to examine the multidimensional poverty situation in South Africa. We also employed the probit model to analyze the factors that could determine multidimensional poverty as well as those that could influence household vulnerability to multidimensional poverty in South Africa. The result of the findings shows that the deprivation indicator ranges from 5 to 90%, revealing that access to a flush toilet facility is an imperative factor towards the standard of living (SDG11) of the households. Also, 66% and 55% were deprived of food security (SDG2) and education (SDG4), respectively. The findings of the probit analysis revealed that factors such as gender, remittances, crop diversification, seasonal farming and market outlets significantly influence the multidimensional poverty of households in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. For instance, factors such as household size showed that an additional unit increase in the size of a household would result in a 5% increase in the chances of the household’s vulnerability to multidimensional poverty. Likewise the extension contact, findings revealed that as contact with extension agents increases by one unit, the vulnerability to multidimensional poverty decreases by 49%. The study also suggests that policies related to increasing crop diversification, promoting farmer groups and enhancing the effectiveness of extension contact as well as increasing market stability for sales of farm products could contribute to reducing the multidimensional poverty level and the vulnerability of households to susceptible to multidimensional poverty. In addition, given the importance of education in the reduction of poverty to SGDs and Agenda 2063 goals, this study suggests that policies that will motivate the rural community to embrace education should be implemented as this could empower local populations to develop innovative solutions to reduce or eliminate poverty vulnerability challenges in South Africa.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be obtained from the authors upon request.

References

Adetoro AA, Ngidi M, Nyam YS, Orimoloye IR (2021) Temporal evaluation of global trends in water footprint, water sustainability and water productivity research. Sci Afr 12:e00732

Alkire S, Foster J (2007) Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement, ‖ Oxford poverty and human development initiative. OPHI Working Paper (7)

Alkire S, Foster J (2011) Understandings and misunderstandings of multidimensional poverty measurement. J Econ Inequal 9(2):289–314

Alkire S, Robles G (2017) Multidimensional Poverty Index summer 2017: brief methodological note and results. OPHI Methodological Note 44, University of Oxford. https://ophi.org.uk/multidimensional-poverty-index/global-mpi-2017/. Accessed 31 Aug 2021

Alkire S, Santos ME (2014) Measuring acute poverty in the developing world: robustness and scope of the multidimensional poverty index. World Dev 59:251–274

Alkire S, Seth S (2015) Multidimensional poverty reduction in India between 1999 and 2006: where and how? World Dev 72:93–108

Alkire S, Roche JM, Vaz A (2017) Changes over time in multidimensional poverty: methodology and results for 34 countries. World Dev 94:232–249

Alkire S, Kanagaratnam U, Suppa N (2020) The global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI): 2020 revision. OPHI MPI Methodological Note 49, Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford

Aloosh M, Salavati A, Aloosh A (2019) Economic sanctions threaten population health: the case of Iran. Public Health 169:10–13

Ambaye TK, Tsehay AS, Hailu AG (2021) Application of ordered logit model to analyze determinants of rural households multidimensional poverty in Western Ethiopia. Int J Dev Econ Sustain. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3819745

Awuse N, Offi PT, Acakpovi A (2020) Internal migration and poverty reduction in Ghana. Int J Technol Manag Res 5(1):72–90

Azeem MM, Mugera AW, Schilizzi S (2018) Vulnerability to multi-dimensional poverty: an empirical comparison of alternative measurement approaches. J Dev Stud 54(9):1612–1636

Bicaba Z, Brixiová Z, Ncube M (2017) Can extreme poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa be eliminated by 2030? J Afr Develop 19(2):93–110

Cheteni P, Khamfula Y, Mah G, Casadevall SR (2019) Gender and poverty in South African rural areas. Cogent Soc Sci 5(1):1586080

Cumming TL, Shackleton RT, Förster J, Dini J, Khan A, Gumula M, Kubiszewski I (2017) Achieving the national development agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through investment in ecological infrastructure: a case study of South Africa. Ecosyst Serv 27:253–260

Dagunga G, Ayamaga M, Danso-Abbeam G (2021) A re-look at poverty through the lens of the Sustainable Development Goals in Ghana: drivers and policy implications. J Poverty. https://doi.org/10.1080/10875549.2020.1869661

Danso-Abbeam G, Dagunga G, Ehiakpor DS (2020) Rural non-farm income diversification: implications on smallholder farmers’ welfare and agricultural technology adoption in Ghana. Heliyon 6(11):e05393

Dehury B, Mohanty SK (2015) Regional estimates of multidimensional poverty in India. Economics 9(2015–36):1–35

Ekanayake EM, Moslares C (2020) Do remittances promote economic growth and reduce poverty? Evidence from Latin American countries. Economies 8(2):35

Eshetu G, Johansson T, Garedew W, Yisahak T (2021) Determinants of smallholder farmers’ adaptation options to climate change in a coffee-based farming system of Southwest Ethiopia. Clim Dev 13(4):318–325

Espinoza-Delgado J, Klasen S (2018) Gender and multidimensional poverty in Nicaragua: an individual-based approach. World Dev 110:466–491

FAO (2016) Agriculture: key to achieving the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

Feeny S, McDonald L (2016) Vulnerability to multidimensional poverty: findings from households in Melanesia. J Dev Stud 52(3):447–464

Feliciano D (2019) A review on the contribution of crop diversification to Sustainable Development Goal 1 “No poverty” in different world regions. Sustain Dev 27(4):795–808

Fransman T, Yu D (2019) Multidimensional poverty in South Africa in 2001–16. Dev S Afr 36(1):50–79

Gebrekidan DK, Mekuriaw A, Cameron J (2020) Rural household vulnerability to multidimensional poverty in Ethiopia’s Degu’a Tembien District, Tigray. Asian Dev Perspect 11(1):33–55

Gebrekidan DK, Bizuneh AM, Cameron J (2021) Determinants of multidimensional poverty among rural households in Northern Ethiopia. J Rural Community Dev 16(1):133–151

Hagen-Zanker J, Himmelstine CL (2016) How effective are cash transfers in reducing poverty, compared to remittances? Soc Policy Soc 15(1):29–42

Hebinck P (ed) (2014) In the shadow of policy: everyday practices in South Africa’s land and agrarian reform. Wits University Press, Johannesburg, p 217

Hirschl TA, Mohammed A, Fagan A, Houssock C, Bergh L (2023) International comparisons in fighting poverty: the poverty stoplight program in South Africa, the UK, and the US. J Poverty 27:82–97

Kim H (2019) Beyond monetary poverty analysis: the dynamics of multidimensional child poverty in developing countries. Soc Indic Res 141(3):1107–1136

Krishnamurthy PK, Lewis K, Choularton RJ (2014) A methodological framework for rapidly assessing the impacts of climate risk on national-level food security through a vulnerability index. Glob Environ Change 25:121–132

Kuntz B, Zeiher J, Hoebel J, Lampert T (2016) Social inequality, smoking, and health. Suchttherapie 17(3):115–123

Leisher C, Samberg LH, Van Buekering P, Sanjayan M (2013) Focal areas for measuring the human well-being impacts of a conservation initiative. Sustainability 5(3):997–1010

Megbowon ET (2018) Multidimensional poverty analysis of urban and rural households in South Africa. Stud Univ Babes-Bolyai Oecon 63(1):3–19

Mert K, Kadioglu HASİBE (2016) Nursing interventions to help prevent children from working on the streets. Int Nurs Rev 63(3):429–436

Mkhize TG, Mutereko S (2022) Grassroot engagement in local economic development: a case study of eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality. Afr J Dev Stud 12(1):189–208

Motuna FY, Rajan DS, Ameda TT (2020) Determinants of rural multidimensional poverty: the case from Kuyu District, Central Ethiopia. J Humanit Soc Sci 25(2):46–54

Mthethwa S, Wale E (2021) Household vulnerability to food insecurity in rural South Africa: evidence from a nationally representative survey data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(4):1917

Mubecua M, Mlambo VH (2021) The expropriation of land without compensation in South Africa: a strategy for alleviating or worsening poverty? In: The new political economy of land reform in South Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp 55–77

Mushongera D, Zikhali P, Ngwenya P (2017) A multidimensional poverty index for Gauteng province, South Africa: evidence from Quality of Life Survey data. Soc Indic Res 130(1):277–303

Nandi R, Nedumaran S, Ravula P (2021) The interplay between food market access and farm household dietary diversity in low and middle income countries: a systematic review of literature. Glob Food Sec 28:100484

National Planning Commission (2013) National Planning Commission National Development Plan 2030: our future—make it work. National Planning Commission, The Presidency, Republic of South Africa, p 66

Ngumbela XG, Khalema EN, Nzimakwe TI (2019) Food insecurity conundrum: a case study of Amathole district in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. Int NGO J 14(3):13–21

Ojo TO, Ogundeji AA, Belle JA (2021) Climate change perception and impact of on-farm demonstration on intensity of adoption of adaptation strategies among smallholder farmers in South Africa. Technol Forecast Soc Change 172:121031

Olarinde LO, Abass AB, Abdoulaye T, Adepoju AA, Fanifosi EG, Adio MO, Wasiu A (2020) Estimating multidimensional poverty among cassava producers in Nigeria: patterns and socioeconomic determinants. Sustainability 12(13):5366

OPHI and UNDP (2020) Charting pathways out of multidimensional poverty: achieving the SDGs. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2020_mpi_report_en.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2021

Padda IUH, Hameed A (2018) Estimating multidimensional poverty levels in rural Pakistan: a contribution to sustainable development policies. J Clean Prod 197:435–442

Ponce C (2020) Intra-seasonal climate variability and crop diversification strategies in the Peruvian Andes: a word of caution on the sustainability of adaptation to climate change. World Dev 127:104740

Poverty O, Human Development Initiative (2021) Policy–a multidimensional approach. https://ophi.org.uk/policy/multidimensional-poverty-index. Accessed 25 Feb 2022

Roelen K (2017) Monetary and multidimensional child poverty: a contradiction in terms? Dev Change 48(3):502–533

Roelen K, Gassmann F, de Neubourg C (2012) False positives or hidden dimensions: what can monetary and multidimensional measurement tell us about child poverty in Vietnam? Int J Soc Welf 21(4):393–407

Rogan M (2016) Gender and multidimensional poverty in South Africa: applying the global multidimensional poverty index (MPI). Soc Indic Res 126(3):987–1006

Santos ME, Villatoro P (2018) A multidimensional poverty index for Latin America. Rev Income Wealth 64(1):52–82

Socio LM (2017) King Sabata Dalindyebo local municipailty Socio economic review and outlook, 2017. Socio Economic Consultative Council, Eastern Cape. https://www.ecsecc.org.za/documentrepository/informationcentre/king-sabatadalindyebo-local-municipality_52786.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2022

Statistics South Africa (2017) Poverty trends in South Africa, No. 03-10–06. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/Report-03-10-062015.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2021

Statistics South Africa (2022) Assessing state capacity to respond to the needs of communities. https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2022/3-march/22-03-2022_National_Council_of_Provinces_Provincial_Week/General_Resource_Documents/PRU_Bulletin_NCOP_Provincial_Week_2022_Final.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2023

Stats SA (2017) Poverty Trends in South Africa: an examination of absolute poverty between 2006 and 2015. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/Report-03-10-06/Report-03-10-062015.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2021

Tejada JJ, Punzalan JRB (2012) On the misuse of Slovin’s formula. Philipp Stat 61(1):129–136

Tesfaye W, Tirivayi N (2020) Crop diversity, household welfare and consumption smoothing under risk: evidence from rural Uganda. World Dev 125:104686

Tibesigwa B, Visser M (2016) Assessing gender inequality in food security among small-holder farm households in urban and rural South Africa. World Dev 88:33–49

Tran VQ, Alkire S, Klasen S (2015) Static and dynamic disparities between monetary and multidimensional poverty measurement: evidence from Vietnam. OPHI working paper no. 97. University of Oxford

United Nations (2014) The road to dignity by 2030: ending poverty, transforming all lives and protecting the planet. Synthesis Report of the Secretary-General on the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda. https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/reports/SG_Synthesis_Report_Road_to_Dignity_by_2030. Accessed 15 June 2021

Vukojevic M, Zovko A, Talic I, Tanovic M, Resic B, Vrdoljak I, Splavski B (2017) Parental socioeconomic status as a predictor of physical and mental health outcomes in children—literature review. Acta Clin Croat 56(4):742–748

Wang D, Hagedorn A, Chi G (2019) Remittances and household spending strategies: evidence from the Life in Kyrgyzstan Study, 2011–2013. J Ethn Migr Stud 47:3015–3036

World Bank (2009) Accelerating catch-up: tertiary education for growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Directions in development; human development. World Bank. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/2589. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO. Accessed 23 Sept 2021

World Bank (2018) Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: an assessment of Drivers, Constraints and Opportunities. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/pdf/124521-rev-ouo-south-africa-povertyand-inequality-assessment-report-2018-final-web.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2021

World Bank (2020) Poverty and shared prosperity (2020): reversals of fortune. https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity. Accessed 31 Aug 2021

World Bank Group (2018) Overcoming poverty and inequality in South Africa: an assessment of drivers, constraints and opportunities. World Bank. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/530481521735906534/pdf/124521-REV-OUO-South-Africa-Poverty-and-Inequality-Assessment-Report-2018-FINAL-WEB.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2021

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the University of KwaZulu-Natal for providing an enabling environment to conduct this study. We also express our gratitude to Dr Yiseyon Sunday Hosu for helping with the data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of KwaZulu-Natal. This study did not receive any financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAA: writing and preparation of the paper, modelling and analysis. MSCN: supervision and editing. GD-A: editing, modelling, and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

The study’s ethical clearance was exempted as there was no risk associated with the study.

Informed consent

The purpose of the study was made aware to all individual participants and verbal consent was obtained from the respondents.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adetoro, A.A., Ngidi, M.S.C. & Danso-Abbeam, G. Towards the global zero poverty agenda: examining the multidimensional poverty situation in South Africa. SN Soc Sci 3, 148 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00735-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00735-2