Abstract

The purpose of this study is to find out how women negotiate their path to leadership; the barriers and facilitators and how they navigated them to reach the top. An inductive, qualitative approach has been used to systematically analyze the in-depth open-ended responses of female leaders in public higher education institutions and note emergent themes. Women face various endogenous and exogenous challenges in their journey to the top. The major emergent themes turned out to be personal cognizance, individual development, breaking gender stereotypes, and embracing and translating gynandrous leadership by women leaders. Familial support and women-friendly organizational policies were regarded as the most significant enablers. The major barriers turned out to be a lack of institutional support and grit among women. The metaphor of the labyrinth turned out to be an apt metaphor for studying the journeys of women. This research is limited by survivor bias as it only studies women who successfully navigated the labyrinth to the top but not those who got lost in the labyrinth. This study examines the leadership journeys of women leaders in public higher education in Pakistan by extending the metaphor of a labyrinth in the public sector in academia. It also proposes a conceptual model of how women navigate the labyrinth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globally women are making remarkable progress across diverse professions and organizations (Lyness and Grotto 2018) This trend can be credited to numerous influences ranging from socio-economic changes to perceptual shifts in the mindset of societies and changing demographic trends (Abalkhail 2017). Women are becoming more prominent and appreciated in a wide range of professions and organizations around the world (Abalkhail 2017). This trend is attributable to several factors, including government policy initiatives, international pressure for equitable participation, and changes in how people view female leadership (Powell 2012; Richardsen et al. 2016). Yet, they are still underrepresented in leadership roles (Chesters and Watson 2012). Less engagement of women, particularly in academics, is confirmed by research on higher education leadership (Benschop and Brouns 2003; Kjeldal et al. 2005; Fletcher 2007; Hopkins et al. 2008; Maranto and Griffin 2011; Mulcahy and Linehan 2014). Despite these significant advancements women still lag in elite leadership positions across various professions around the globe (Eagly and Carli 2007; Acker 2009).

Exclusive culture in various regions presents a unique set of challenges for women (Hodges et al. 2017). Notwithstanding having to navigate different paths than men in achieving leadership roles women are presenting novel ways of dealing with the opportunities and challenges of the twenty first century’ (Latchem et al. 2013). Research shows that the exclusive culture in various regions presents a unique set of challenges for women. The existing inquiry on gender discrepancies in leadership is crushingly based on Western data and there is a requirement to incorporate studies in non-Western cultures (Eagly et al. 2003; Eagly et al. 2007; Cook 2007; Stead and Elliott 2009; Gupta and van Wart 2015). To develop an integrated comprehension of gender issues in South Asia, it is imperative to contextualize it in the prevailing socioeconomic, religious, and geopolitical situations.

This study extends the theory of role congruity theory of prejudice by identifying micro and macro factors that enable the leadership journeys of these female educational leaders. At the individual level, this study offers insights into how female educational leaders make sense of their leadership journeys. What leadership behaviors and tactics do they consider most significant to navigate this labyrinth successfully? At the organizational level, academic leadership paths of women Vice-Chancellors can offer understandings useful for the growth and improvement of systems that train and prepare women to thrive in the role. Additional comprehensions collected from this research can offer approaches for development to ambitious women deans and advise on the implementation of resources and platforms that endorse those accomplishments. Lastly, this study will also provide insight into how large-scale factors trickle down to the managerial level to influence organizational practices thus influencing women gaining access to leadership positions.

Pakistan is a South Asian country with gender segregation and strong patriarchal culture (Roomi and Parrott 2008) where the norm of systemic subordination of females’ honor (Izzat) strongly persists. Pakistan has been a signatory to major international agreements promoting gender equality and yet women face dependency and subordination due to their low social, economic, and political status in Pakistani society (Amir-ud-din et al. 2021). Exploring the academic leadership journeys of women Vice-Chancellors can offer interesting insights useful not only for women to succeed in the role but also for understanding and overcoming the tricky issues which hinder the implementation of international agreements signed by Pakistan for women's empowerment.

In Pakistan, there are 15 female Vice-Chancellors and 108 male Vice-Chancellors in public universities (Yousaf 2020). In this study 12 of these female Vice-Chancellors have been interviewed extensively to understand how these women broke the code and made it to the top.

Objective of the study

The objective of this research is to study the experience of women leaders in higher education in Pakistan investigating the socio-cultural barriers and facilitators faced by women in their upward career progression and how they navigate them.

Significance of the study

Exploring the academic leadership journeys of women Vice-Chancellors offers interesting insights useful not only for the navigation of the leadership labyrinth and preparing women to succeed in the role but also for the tricky issues which hinder the implementation of international agreements signed by Pakistan for women's empowerment. This study offers a novel and insightful analysis of the challenges faced by Pakistani women seeking leadership positions in public higher education institutions. The study is important because it highlights the challenges that ambitious women face in their conservative societies and contributes to the development of strategies and policies that will benefit other ambitious and aspiring women.

Research question

This study examines the intersection of gender and leadership in higher education institutions, in Pakistan by interviewing the topmost female leaders in higher education, Pakistan i.e., Vice Chancellors. This study is guided by the research question: How do female educational leaders navigate their path to leadership in Pakistan?

Theoretical background

The emphasis of most research theories on leadership and gender literature has been on the parallels and discrepancies of leadership style among genders and how leaders are viewed by followers (Schatzki 2001; Whittington and Litt 2002; Zaccaro et al. 2008). Women are associated with transformational leadership styles that involve inspiring followers to commit to a shared vision for the organization/unit challenging them to be innovative problem-solvers and developing followers via coaching and mentoring whereas men are transactional leaders who emphasize the transaction between the leaders and followers based on leaders discussing with others what is required and specifying the conditions and rewards they will receive when they fulfill those requirements (Burns 2003; Bass 1985). However, lately, research has also established that leadership enactment varies according to the context (Schedlitzki et al. 2017). Particularly social contexts determine gendered leadership and non-leadership, and the way vital organizational stakeholders comprehend such leadership ultimately determines its translation to organizational policies (Hearn and Piekkari 2005).

Gynandrous leadership (gyne = female, andro = male) is a concept put forward by Athanasopoulou et al. (2018) where they studied the experiences and career trajectories of 12 global female CEOs. Simply put gynandrous leadership states forming a distinctive leadership style that merges vision and strategy (typically considered to be male characteristics) with what are deemed to be more stereotypically female attributes, such as a more nurturing and dialoguing style (Athanasopoulou 2018). It is defined in conscious distinction with stereotypical perceptions of androgynous leadership style (Korabik 1990) in which male characteristics take precedence. According to Athanasopoulou et al. (2018), the female CEOs reported that they bring together female leadership skills and behaviors to transcend gender stereotypes and present male skills in addition to their existing leadership base thus embracing the gynandrous leadership.

Gender role congruity theory suggests that women may not be perceived to be as effective leaders as men, due to the need for them to exhibit roles in their leadership position that are not congruent with the communal goals that are assumed to be part of their gender role (Murray and Chua 2014). In contrast, the male gender role, being agentic, legitimizes the role of the male leader (Murray and Chua 2014). This situation fosters the selection of different jobs by men and women, thereby producing sex-segregated employment (Jacobs 1996; Cejka and Eagly 1999). It also predicts that women will be less likely than men to emerge as leaders when expectations for the leader role are incongruent with gender stereotypes (Ritter and Yoder 2004).

Women and the leadership labyrinth

Metaphors have been devised to explain impediments to women’s progress, comprising the glass ceiling, glass cliff, maternal wall, glass escalator, and the sticky floor (Smith et al. 2012; Khan 2017; Jauhar and Lau 2018; Surangi 2020; Al-Qahtani et al. 2021). Eagly and Carli (2008), introduced a new style to the research involving the glass ceiling for women in professional spaces by discarding the occurrence of the glass ceiling as the lone obstacle in the career trajectory of capable and qualified women. As stated by them, women are not barred due to a glass ceiling rather there are diverse and multifaceted complications along the twisting path that women essentially must navigate. They proclaim that the labyrinth is a better metaphor to establish what meets the women in their professional efforts (Eagly and Carli 2008). The labyrinth metaphor implies that progress is tricky but not unfeasible (Gloor 2016). If the route taken by men is interpreted as a road (imaginably with few mountains and fissures along the path), the labyrinth that women confront offers a more challenging route that requires more time to steer and involves a better probability of collapse (Johnson and Fournillier 2021).

As individual-level explanations, researchers have identified various factors for why women start shaping their perceptions about their access to careers early on (Castellano and Rocca 2014). Another major barrier to women's progress is their distorted perception of the self. When they are continuously raised to believe that men are more deserving and capable then they internalize such perceptions thus resulting in poor self-confidence (Kolb 1999). Jackson (1989) refers to this phenomenon as relative deprivation theory stating that due to poor self-confidence women show satisfaction with less. De Vries (2005) has described it as “neurotic imposter syndrome” where the person does not consider himself/herself to be worthy of the success they have achieved. The traditional division of labor among women and men also contributes to the work–life balance because family and caregiving are still primarily a woman's responsibility (Bianchi et al. 2012; Eagli and Carli 2007). Women are expected to be more transformative, nurturing, and democratic and are punished for acting aggressively at times because they violate the existing gender stereotypes (Bray 2013). Similarly, women always try to gain more experience and develop more skills to stay in the pipeline long enough to be considered worthy enough to apply for a senior position when the opportunity presents itself whereas men do so with relative ease (Applebaum 2003).

As organizational level explanations, researchers have identified various barriers faced by women such as lack of sponsorship, opportunities for self-promotion, and limited access to networks (Fitzsimmons et al. 2014). They also face structural barriers such as minimal appointments to senior leadership positions (McDonald and Westphal 2013). Another major barrier faced by women is the “glass cliff” (Ryan and Haslam 2007; Mulcahy and Linehan 2014; Glass and Cook 2016) which means women are consciously put in risky positions in organizations, setting them up for fall (Sabharwal 2015). It is also referred to as “think crisis-think female” (Koenig et al. 2011). The structure of an organization protects masculine authority due to implicit masculine gender bias as well (Braun et al. 2017) where the leader is wordlessly assumed to be a male. Women also experience the double bind where the men get rewarded for enacting aggressive behavior whereas women are punished because women are expected to exhibit communal traits while men are supposed to be agentic (Rudman and Glick 2001; Heilman and Okimoto 2007; Bowles et al. 2007). In conjunction with expectation states theory, superior positions, and job competence are assigned to men as compared to women and these values produce expectations that then impinge on the social dealings through which leadership is realized and utilized (Berger 1992; Ridgeway 2007).

At the societal level, researchers have identified the gendered division of labor, gender-role perceptions, and gender stereotypes offering obstacles for women (Kark 2007). Women and men are socialized into their expected gender roles from a very early age which shapes their future behavioral and aspirational tendencies (Hines 2004; Lippa 2005). Later as they join the mainstream society the differential treatment of both genders further internalizes gender role expectations thus shaping the self-confidence of women and men regarding various roles and professions (Hoffman 1972; Sahlstein and Allen 2002). Women are expected to be communal, and men are expected to be agentic (Rudman and Phelan 2008; Vinkenburg et al. 2011). Groysberg and Abrahams (2014) reported in a study of leadership experience across genders that male executives lauded their spouses for making positive contributions to their careers, whereas female executives lauded their spouses for not impeding their progression to executive positions in organizations. The traditional division of gender roles (work–family divide) also causes a barrier for women to make continuous trade-offs between work and family life (Wheatley 2012). Women often suffer from negative psychosocial and economic consequences to achieve the appropriate work–life balance (Hopkins et al. 2007).

Most of the literature on women in leadership has been conducted in rich, Western democracies (Lerner et al. 1997; Roomi and Parrot 2008). These studies critically neglect the social lives, structures, and context of developing economies (Wees and Romijn 1987; Aldrich 1989; Allen and Truman 1993).

The Pakistani context

This study, therefore, aims to provide “native” knowledge for the interpretation of the findings of this study in the specific cultural context of Pakistan. Pakistan is an Islamic South Asian developing country where the status of women is low as depicted by indicators such as literacy rate, fertility rate, sex ratio, and labor-force participation (Moghadam 1992). The patriarchal system of controls over women constitutes the institutionalization of a limiting code of conduct for women, gender segregation, male guardianship of women, and the interdependence of family honor upon female virtue (Kabeer 1988). Most traditions and practices guide women to the norms of society by confining them to the charivari (four walls of the house) (Ambreen 2015).

According to the Gender Gap Report of the World Economic Forum (2021), Pakistan ranks at 153rd position (out of 156 countries surveyed) in terms of the gender gap index which is dismal (Sharma et al. 2021). The Gender Inequality Index (2019) by the United Nations Development Program (Gutiérrez-Martínez et al. 2021) which measures gender inequalities in three important aspects of human development—reproductive health; empowerment; and economic status, ranks Pakistan in 135th position which is also considerably low. Pakistan is a rapidly evolving country in terms of female leadership. In recent decades, more women have held prominent positions in government and non-profit organizations (Ferdoos 2005). This research is substantial in realizing the present academic leadership narrative that reinforces male supremacy in higher educational institutes in Pakistan. Furthermore, it will assist social scientists in investigating the effect of cultural and social dynamics on female empowerment and widen their outlook to recognize and acknowledge women’s leadership skills and abilities.

Research methodology

This study explores the journey of female educational leaders namely, Vice Chancellors at public universities in Pakistan. The Vice-Chancellor is the chief executive officer of the university and is responsible for all administrative and academic functions of the University and for ensuring that the provisions of the Ordinance, Statutes, Regulations, and Rules are faithfully observed to promote the general efficiency and good order of the University. The Vice-Chancellor in Pakistan is equivalent to a President at Western European Universities (Table 1).

According to The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021), 8% of women dominate the senior-most position of Vice-Chancellor in Pakistani Universities. Our sample of a mere 10% is indicative of this certainty. This study is unique in terms of the high-ranking respondents and the rich data provided by them. To achieve this unparalleled magnitude of high-profile interviewees the researcher had to draw assistance from the chairman higher education commission, Pakistan. This study’s case was personally forwarded by the Chairman, Higher Education Commission, Pakistan, and the Director of Research and Development, Higher Education Commission, Pakistan to all the respective female Vice-Chancellors of the public sector universities of Pakistan and thus made possible. The Higher Education Commission Pakistan shared the data and contact information of all the Vice-Chancellors in Pakistan with the researcher making the research process extremely smooth and feasible. The Vice Chancellors were initially contacted via emails where they were informed about the research objectives and requested participation in the study. After the rigorous exchange of emails appointments were made for interviews in the respective offices of Vice-Chancellors as per their availabilities. All interviews were conducted in a relaxed environment free from any sort of interruptions or time limitations.

The sample selected for this study represents the extreme case. The reason for the selection of this small yet significant research sample is to study the breakthrough journey to the top by these numerically small and successful female leaders. Extreme cases are welcomed as they can disclose understandings that may be tricky to separate in more common situations (Eisenhardt 1989; Athanasopoulou et al. 2017). As the sample size is also small in this extreme case analysis, this also rests well in accomplishing the main goal of qualitative research i.e., analytical generalization rather than statistical generalization. The focus of this research is on the participant's views regarding the unfolding of events in their leadership journeys. How have they navigated through the path to leadership? Analytical insights are drawn from the analysis of “their” perspective (Cresswell 2003; Pratt 2009). Some women began their journeys from international schools and went to top-notch institutes whereas some of them began from “taat-school” (rural schools without roofs and basic infrastructure such as furniture). In terms of marital status, seven of these Vice-Chancellors were married, three were divorced, and two were single and chose not to marry. All these women earned a Ph.D. degree from abroad except one who secured it from the University of Punjab, Pakistan.

Data analysis

The data were obtained through face-to-face in-depth interviews, to get a thoughtful insight into the lived experiences of women leaders. For this purpose, an interview guide was developed that covered a range of topics, identified through an extensive review of the literature, to remain close to the research questions. Moreover, a pilot study was also undertaken for testing the interview guide and enhancing the quality of the research. Its results and reflections highlighted the valid and reliable questions in the interview protocol and gave further directions in the study. All interviews were audio recorded after obtaining informed consent; however, field notes were also taken during the discussion with the participants to keep a record of the important codes and themes identified by participants. The interviews were conducted in office settings, where the participants felt more comfortable. Each interview took approximately 70 to 80 min.

I used MAXQDA software employing the open-ended grounded theory approach for the qualitative data analysis. This qualitative analysis began with the verbatim transcription of the interviews. The interviews were read and re-read multiple times and all the important and relevant text descriptions were highlighted which can also be referred to as open coding. This resulted in the creation of initial codes or first-order concepts. As these transcripts were read multiple times, notes were also made about the first impressions separately. All the relevant words, phrases, and sections were highlighted, and color-coded. In the initial indexing phase (Gibbs 2009). In the second phase, also termed the axial coding phase, all the important and recurring codes were compared, and similar codes were brought together to create second-order concepts, also referred to as categories. In the next phase, the categories were labelled, and the most relevant categories were grouped to achieve a higher level of abstraction. These categories were connected to generate third-order concepts. These are also referred to as themes. In the final level of abstraction, these themes were connected to create theory dimensions by defining the scope of the facilitators and barriers as having personal, organizational, or societal dimensions for these women leaders. This is also referred to as selective coding. The main purpose of selective coding also is to cumulate all the categories together to achieve further abstraction of concepts (Strauss and Corbin 2008).

Findings

The interviewers were asked to make sense of their leadership journeys and how they navigated the barriers and twists along the way. The themes that emerged along their journeys were their cognizance, focus on individual development, breaking gender stereotypes, and translation of gynandrous leadership that enabled them to finally locate the center of the labyrinth.

Personal cognizance

A recurring theme that was found among all the interviews was that the leadership journey only began for these women when they accepted the drive for leadership inside them and they came to terms with the fact that they have what it takes to become a leader. They also stressed that many of their colleagues with far more potential and capabilities got lost in twists and turns very early in their journeys because they themselves did not realize their potential and never considered themselves worthy enough to develop any further capabilities. They also made a recommendation for young aspiring women to realize their own potential very early on and start capitalizing upon it.

Women must be able to recognize and wield their personal and organizational influence. These women leaders owed their success greatly to these qualities.

I am gritty, and I never give up. I once had to fight with a male vice chancellor for straight 5 years for getting a grant for a daycare center for women. By the time I won this, my son was already going to school, but it surely helped other women. I never give up no matter how long it takes.

The lack of self-efficacy that young women managers demonstrate was regarded as one of the major reasons why some women could not navigate their journey to the top.

At times women also do not try enough or believe in themselves. In other instances, society drags them down as well and they believe naysayers instead of believing themselves. Challenges come in life all the time. If you believe in yourself then you can easily navigate through them then.

I have observed one thing that many times women give up. Men will not. We quit for our families sometimes and sometimes just for our own integrity. I would just say the only way for women to succeed is to be brave and never give up. That is the key.

The position of women in management, cannot be seen in isolation from the general status of women in society and the general goals of economic, social, and educational growth (Hammoud 1993). When a woman surpasses men in superiority then it threatens them too.

Men feel threatened by intelligent women. If a woman asks for some rights, then men feel threatened to share that pie. The key is to stay mentally strong, keep improving at your job and not let the behavior of others affect your progress.

Women also realized the significance of the support of human resource management at organizational level to be indispensable to their success.

We require institutional support. Our journeys become more difficult when we get married and then pregnant.

If companies wish to recruit, retain, and develop women professionals, they must actively address the effects of parenthood on women's personal life and careers (Ladge et al. 2018).

Individual development

When we began the interview process all women stressed on a simple linear journey with no barriers or obstacles. But whenever they were probed further, they would share detailed accounts of various obstacles and how they navigated them. The initial reluctance to share the setbacks and twists in their journey can be attributed to the fact that they had come a long way and do not want to look back at weak moments in their life. Women are socialized from a very young age to be “strong” (Brown 2017; Edmonson-Bell and Nkomo 1998) the reason being that strength will provide psychological resistance to the different forms of coercion. There are some female stereotypes that are frequently used in everyday language, particularly in Pakistan such as “Sinf-e-Nazuk” which presents the female as a weak, fragile, and feminine gender (Channa and Tahir 2020). Thus, it could be a natural response by women in top leadership positions to hide their struggles initially to appear strong.

A second major and significant theme that emerged through these discussions is the development of personal strengths and capabilities as well as a strategic vision for the organization. Once women let that awakening sink in that they have the potential to become great leaders they started investing in themselves. These women focussed on learning the right skill set as well as networking with people who further helped them broaden their skillset portfolio and leadership capabilities. They mentioned their role models from whom they learned dos and don’ts and tried to set better examples for the upcoming aspiring young women.

One very interesting finding of this study was the identification of “turning 30” as a major juncture in the lives of these professional women. They stated that if women are mentally strong enough to stand their ground from the age of 27 to 35 then they can aspire to become leaders. Although they did confirm that it affected their prospects for marriage.

Unfortunately, in Pakistan, if you are not married by thirty chances are that you won't be able to find any good marriage proposals. When I was turning thirty, I decided to go for a Ph.D. I was unable to find a good match after finishing my Ph.D. I accepted it as my destiny.

When I got my Ph.D. scholarship abroad my parents told me to get married first otherwise, they won’t let me go as I was already turning 30. I was rushed into marriage and later it ended in divorce.

All my age fellows were getting married before turning 30. My family also had the pressure, but I wanted to pursue further education. My brother became my support and let me finish my education. Later I could not get married as I was past 30 years of age and too “overqualified” to be a good wife anymore. But my brother never deserted me. I still live at his house.

Our respondents did confirm that women do face a double bind i.e., the social backlash associated with women showing assertiveness. They also accepted that family is primarily a woman’s responsibility and thus women must navigate through the double shift of work as well.

The criterion of judgment is still the same that women must work full time also and face the same pressures but manage the household as well. A male member can rest after going home but a female might have to work so it becomes even more distressing for her.

If a male leader is assertive then he is considered confident and macho but if a woman does the same, she is considered aggressive and rude. I was quite notorious during my tenure as loud, rude, noisy, and aggressive just because I was assertive like any man.

Our respondents claimed to have developed a thick skin over the course of their journey. They also termed it as a must-have for progressing in one’s career.

I do not get offended easily. I am aware that as you grow in your career you attract a lot of jealousy. And I attracted my share just as well. But I never let anyone get to me.

Another interesting strength was depicted by single women who seemed to be a soft target of gossip at the workplace.

When people know you are single, and you have achieved this much then there are two kinds of responses. People either become offensive or do not take you seriously at all.

The character of a single woman is very easy to sabotage. You just casually gossip about her without any evidence and that would be it. However, the key is to not get affected and keep excelling at your work.

Breaking gender stereotypes

The existence of gender-based stereotypes was confirmed by our sample. As research shows, men are often perceived as more agentic and competent than women research (e.g., Diekman and Eagly 2000; Williams and Best 1990), whereas women are perceived as more expressive and communal. People believe stereotypes and integrate them in their own behavior (Bennett and Gaines 2010; Thomas et al. 2004).

At the time of my first appointment as a lecturer, the selection panel raised concerns that I have just completed my master’s and that I am a very soft-spoken woman, so I won’t be able to control the class. It felt much discriminated against. My credentials were better than any guy in the room and one civil servant on the panel rigorously supported my case. Forty years later, when I was getting appointed as the first female vice chancellor at the largest university in this country, I was again asked the exact same question. It was disheartening. I did prove them wrong through my hard work.

A woman is not competent till she proves herself; man is competent till he proves otherwise. So, we have to work twice as much to prove our worth.

Translating gynandrous leadership

Last but not the least, another major and very interesting theme was how these women navigated through the transformational and communal leadership styles and only added the agentic aspects, when necessary, putting the communal aspects first thus embracing and translating gynandrous leadership as proposed by Anthanasopoulou et al. (2017). They were mindful of the backlash that might come with the display of tough and stereotypically male leadership styles. They were also cognizant of the weakness associated with the too-communal approach toward leadership. Thus, they translated their own gynandrous leadership style where they put communal style first and added masculine displays of behavior where and when necessary.

I don’t act like a man. And women don’t have to. I think that is the key.

These women also confirmed that women do not need to show assertiveness to establish their authority. They can act like a lady and still get the job done.

If something can be done with polite order then why become assertive unnecessarily? You must choose your battles wisely.

One very interesting aspect that was shared by all but one of these female leaders was that they would not only learn what to do to become successful leaders but also learn what not to do. One of the thought-provoking discoveries that von Alberti-Alhtaybat and Aazam (2018) have offered is that most of the women forces, or leaders employed in higher education have experienced the indifference and lack of backing from the parallel female colleagues and leaders, which can be a new avenue of research that women must learn to navigate towards achieving leadership positions.

I learned don’ts from a lot of people. I have come across many women in my professional life that became bitter due to their professional setbacks. And thus, they could not become successful. The key is not to become bitter and too assertive.

Almost all the women stressed the importance of having female role models and complained that there is a serious lack of female role models. They also suggested that successful women should be recognized and celebrated by other women to get inspiration from them. They also managed to get inspired by some female role models in their lives. Role models are vital in the formation of social identities, and the lack of female role models in leadership positions contributes significantly to the continuation of the gender-stereotyped construction of leadership (Sealy and Singh 2006).

I have many female role models. My first teacher who taught me the subject of social work basically inspired me to study. I was heartbroken after performing poorly in high school. I could not become a doctor. She literally uplifted me and made me believe in myself. My economics teacher in Australia has been a true inspiration. I was so afraid of any subject with numerals. But she made me fall in love with economics. She had such a way to communicate her message to students.

Finally, women tended to make social capital on their own terms. They explained that no same social rules apply to men and women and keeping the religious and cultural aspects in view women cannot capitalize upon all opportunities for socialization and rightly so.

In Pakistani culture, it is easier for men to build social capital. They would spend time at home rather than social networking. Due to our religious and cultural norms, it is not considered very acceptable for women to join the opposite gender in conversations other than work as well as to stay late in the organization. Males have more opportunities as well as more time for networking and it helps in career growth. These connections are necessary and pay off.

The slightest rumour about a female at the organization can very easily hamper her career. And it is very easy to talk about a woman’s character. If you can find nothing else, you can just gossip without any evidence and that would be it.

These women also lauded the use of technology for women to show their active presence at most forums and to utilize it to their advantage (Table 2).

Discussion

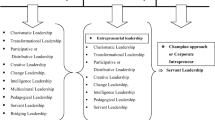

Firstly, we highlight the significant drive of personal cognizance among women which is a must-have to begin the leadership journey. Second, we identify the theme of conscious individual development conducted by these women themselves throughout their journey. Lastly, our study confirms that these women navigated their journeys by overcoming and breaking gender stereotypes while embracing and translating gynandrous leadership (model proposed by Anthanasopoulou et al. 2017) where they simply add masculine leadership traits to their own leadership style by putting their own female leadership style first.

Women generally tend to give themselves a lower rating than other male co-workers, and they're having a hard time when it comes to taking compliments from others (Rudman 1998). This low self-esteem among women is a serious problem. They suffer from ‘Impostor syndrome,’ in which women are afraid of being judged (Laux 2018). They'll be exposed or unmasked as they are unworthy of their success ambitions or the places they've won (Harvey and Katz 1983). The same issue has been highlighted in our sample. According to self-determination theory, when people's requirements for competence, connection, and autonomy are addressed, their motivation and mental health improve (Ryan and Deci 2000). Individuals sometimes reject progress and responsibility when these demands are not addressed (Henneberger et al. 2013).

Another important aspect of this study is the role of religion. Our respondents owed their success to the right and fair interpretation of their religion by themselves and their family members. Muslim women consciously question stereotypes and establish a more inclusive identity to feel legitimized in the face of discriminatory and oppressive social institutions that stifle their academic and professional ambitions (Ahmad 2007; Khosrojerdi 2015). Religious leaders' misinterpretations of the Qur'an and feminism, according to Mernissi (1995) and Wadud (2009), support gender inequality and the replication of misconceptions about Islam and Muslim women. According to Effendi et al. (2019), patriarchal societies interpret Islam to justify their viewpoints on what is and is not acceptable behavior for women, rather than Islam itself. The ‘protection of femininity,’ according to Archer (2002), is a major aspect of Muslim masculinity, with the reasoning being used to justify control and vigilance over women and maintaining men's position of privilege over women. Justification theory asserts that people believe the system is just and fair, causing them to use a variety of tactics to justify their beliefs (Jost and Banaji 1994; Jost et al. 2004). The old boys' network continues to reject individuals who are different simply because they are classified as ‘other’ than the norm (Vinnicombe and Singh 2002). Many respondents blamed misinterpretation of the religion Islam to be the reason for women to lag.

Our respondents owed their success majorly to their familial support despite the societal backlash. Many times, their family members received sweeping comments from their neighbours and relatives to refrain from sending their daughters abroad alone for higher education. All these women received immense support from their families to study, do a job, and focus on their careers in the long term. Given the non-traditional jobs of male members and women's involvement in traditional roles, family support is especially vital for female adjustment (Coleman 2020). All these women also navigated the junction of “dreadful thirties”. Women face a phenomenon called cultural aging (Gullette 2004). If they have not managed to find a husband along career by then, it would be considered unsuccessful aging. The participants of this study termed the period of 27 to 35 years of age to be the scariest and most life changing. Even though women's employment rates are highest in their late twenties, the overall employment rate has reduced due to the rapidly declining employment rate in their thirties, resulting in many women with career interruptions (Shin 2016). However, women who managed to stay strong during this junction eventually succeeded in reaching leadership positions.

The double bind phenomenon (Boone et al. 2013; Pizam 2004) illustrates how stereotypical beliefs within the organization reduce people to secondary responsibilities. Women must manage double shifts as well as double bind (Campos-Soria et al. 2009; Santero-Sanchez et al. 2015). They must balance agentic and communal aspects of leadership as well as manage both career and household. These women overcame these challenges by embracing gynandrous leadership which not only avoids social backlash but is very effective. Our respondents stressed that HR policymakers should make customized HR interventions keeping in view that the challenges and journeys of women are different from men.

Following is the conceptual model of women’s navigation through the labyrinth based on this research (Fig. 1).

Conclusion and limitations

In this research, we have conducted in-depth interviews with 12 female leaders in higher education institutions in Pakistan and extracted several theoretical contributions and practical implications for young aspiring women. It was confirmed that women face and navigate through various endogenous and exogenous challenges to leadership (Alsubaihi 2016). We make an important theoretical contribution through this study by putting gender and leadership study in discourse with human resource management and screening the following three literature contributions of women's leadership behaviour. Resonating with the rich data from these interviews, it canters on three major themes personal cognizance, individual development, and gynandrous leadership. Collectively it explains how women successfully navigate their leadership journeys by overcoming barriers, capitalizing on the facilitators, and accomplishing their role as a leader. There is scope for future research to study the appropriate interventions that can be applied to make this journey more feasible for young aspiring women. This study can serve as an elementary segment for further research. We recognize the limitations of this research and discuss how these can function as prospects for future research.

It is a recognizable fact that the sample size of 12 interviews seems moderately very small, but it accurately represents the insignificant number of females in top leadership positions. Corresponding to the viewpoint of qualitative research we refrain from making any statistical assertions that could have been possible through hypothesis testing on huge data collected across the globe. As an alternative, we use the thick descriptions of this data to draw efficacious tactics at a personal level and HR interventions at the policy level to pave the way for aspiring and talented young females. Once more we acknowledge the limitations of this study and suggest possibilities for future research as a solution.

A major limitation of this study was a cultural limitation and survivor bias as we were able to interview only those women leaders who were able to break the glass ceiling and navigate their way to the top. We however missed out on those women who were not able to navigate their journeys successfully and got lost in the twists and turns along their way. There is thus scope for future researchers to fill this gap by interviewing female directors and professors who either had to quit or were unable to make it to the top. There is also scope for further research into possible practical HR interventions and practices that can convert this labyrinth into a comparatively straighter path for women (Pichler 2008; Liu and Ruths 2013; Biswas et al. 2020).

There is scope for future research on conducting a comparative narrative analysis of leadership across both genders to find how their journeys differ from each other and what interesting insights they can offer for both genders. We specially make a call for comparative leadership studies across industries, cultures, and countries with large data sets to make statistical claims. Another interesting aspect to cover is the private sector sample as well. Due to the limited size of our data from one country, we could not dig into the role played by cultural or socioeconomic factors. Future researchers can delve into these varying contexts with comparisons across the large dataset and offer interesting insights.

The impending HR studies should be conducted with a focus on further digging deeper into the major themes identified in this study i.e. personal cognizance, individual development, breaking stereotypes, and gynandrous leadership. Our research showed that personal cognizance comes early in aspiring females and makes ground for individual development paving the way for further career success. Focussing on personal cognizance and thus individual development HR should focus on creating customized HR interventions rather than generic ones (Anthanasopoulou et al. 2017) According to Antahansopolou et al. (2017), there should be certain HR career interventions for mid-level women and similarly for senior level depending on their requirements. There should be a departure from one size fits. There is thus again scope for future HR researchers to work in close consideration with human resource management professionals to design personalized interventions for women at various stages of their careers.

Last but not least one important aspect highlighted in this study which distinguishes it from western research is the significance of the religion Islam and family values in Pakistan (Varley 2012; Bradley and Saigol 2012). Women cannot achieve a similar proportion as men in top leadership positions unless attempts are made for social change which requires correct interpretations of religious values and cultural norms concerning women. This qualitative change primarily builds the groundwork for women to aspire for leadership journeys which can later be cemented with appropriate and customized HR interventions.

Data availability

As my study is based on in-depth qualitative interviews with Vice-Chancellors in Pakistan, I cannot publish the transcript of the interviews due to confidentiality reasons; the persons could be easily identified and experience repercussions for what they shared with me. However, I am willing to share the transcripts of the interviewers with you and potential reviewers for transparency reasons during the review process.

Single author I am a single author of this article.

References

Abalkhail JM (2017) Women and leadership: challenges and opportunities in Saudi higher education. Career Dev Int. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-03-2016-0029

Ahmad F (2007) Muslim women’s experiences of higher education in Britain. Am J Islam Soc 24(3):46–69

Aldrich J (1989) Autonomy. Oxf Econ Pap 41(1):15–34

Allen S, Truman C (1993) Women and men entrepreneurs: life strategies, business strategies

Al-Qahtani AM, Ibrahim HA, Elgzar WT, El Sayed HAE, Abdelghaffar T, Moussa RI, Alenzy AR (2021) Perceived and real barriers to workplace empowerment among women at Saudi universities: a cross-sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health 25(1):26–35

Alsubaihi S (2016) Challenges for women academic leaders to obtain senior leadership positions in higher education in Saudi Arabia

Ambreen M (2015) Female participation in higher education management in Pakistan: an analytical study of possible barriers. Int J Gend Stud Dev Soc 1(2):119–134

Amir-ud-Din R, Fatima S, Aziz S (2021) Is attitudinal acceptance of violence a risk factor? An analysis of domestic violence against women in Pakistan. J Interpers Violence 36(7–8):NP4514–NP4541

Antonopoulos R (2009) The current economic and financial crisis: a gender perspective. Levy Economics Institute, Working Papers Series, 562

Applebaum B (2003) Social justice, democratic education and the silencing of words that wound. J Moral Educ 32(2):151–162

Archer J (2002) Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Aggress Violent Behav 7(4):313–351

Athanasopoulou A, Moss-Cowan A, Smets M, Morris T (2018) Claiming the corner office: female CEO careers and implications for leadership development. Hum Resour Manag 57(2):617–639

Barrett-Landau S, Henle S (2014) Men in nursing: their influence in a female dominated career. J Leadersh Inst 13(2):10–13

Bass BM (1985) Leadership: good, better, best. Organ Dyn 13(3):26–40

Benschop Y, Brouns M (2003) Crumbling ivory towers: academic organizing and its gender effects. Gend Work Organ 10(2):194–212

Bennett T, Gaines J (2010) Believing what you hear: the impact of aging stereotypes upon the old. Educ Gerontol 36(5):435–445

Berger I (1992) Threads of solidarity: women in South African industry, 1900–1980. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Bianchi SM, Sayer LC, Milkie MA, Robinson JP (2012) Housework: who did, does or will do it, and how much does it matter? Soc Forces 91(1):55–63

Biswas K, Boyle B, Bhardwaj S (2020) Impacts of supportive HR practices and organisational climate on the attitudes of HR managers towards gender diversity—a mediated model approach. Evid Based HRM Glob Forum Empir Scholarsh 9(1):18–33

Boone J, Veller T, Nikolaeva K, Keith M, Kefgen K, Houran J (2013) Rethinking a glass ceiling in the hospitality industry. Cornell Hosp Qy 54(3):230–239

Bowles HR, Babcock L, Lai L (2007) Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 103(1):84–103

Bradley T, Saigol R (2012) Religious values and beliefs and education for women in Pakistan. Dev Pract 22(5–6):675–688

Braun S, Stegmann S, Hernandez Bark AS, Junker NM, van Dick R (2017) Think manager—think male, think follower—think female: gender bias in implicit followership theories. J Appl Soc Psychol 47(7):377–388

Bray F (2013) Technology, gender and history in imperial China: great transformations reconsidered. Routledge, London

Brown SE (2017) Gender and the genocide in Rwanda: women as rescuers and perpetrators. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Burns JM (2003) Transforming leadership: a new pursuit of happiness. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York

Campos-Soria JA, Ortega-Aguaza B, Ropero-Garcia MA (2009) Gender segregation and wage difference in the hospitality industry. Tour Econ 15(4):847–866

Castellano R, Rocca A (2014) Gender gap and labour market participation: a composite indicator for the ranking of European countries. Int J Manpow 35(3):345–367

Cejka MA, Eagly AH (1999) Gender-stereotypic images of occupations correspond to the sex segregation of employment. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 25(4):413–423

Channa AR, Tahir TB (2020) Be a man, do not cry like a woman: analyzing gender dynamics in Pakistan. Lib Arts Soc Sci Int J 4(2):361–371

Coleman R (2020) COVID-19 gender-based health worries, depressive symptoms, and extreme anxiety. J Res Gend Stud 10(2):106–116

Cook N (2007) Gender, identity, and imperialism: women development workers in Pakistan. Springer, Berlin

Cresswell A (2003) Sex/Gender: which is which? a rejoinder to mary riege laner. Sociol Inq 73(1):138–151

De Vries MFRK (2005) The dangers of feeling like a fake. Harv Bus Rev 83(9):108

Diekman AB, Eagly AH (2000) Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: women and men of the past, present, and future. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 26(10):1171–1188

Eagly AH, Eagly LLCAH, Carli LL, Carli LL (2007) Through the labyrinth: the truth about how women become leaders. Harvard Business Press, Brighton

Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC, Van Engen ML (2003) Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull 129(4):569

Edmonson-Bell ELJ, Nkomo S (1998) Armoring: learning to withstand racial oppression. J Comp Fam Stud 29:285–295

Effendi NI, Murni Y, Gusteti Y, Roni KA (2019) Educational mismatch and non-cognitive skills of woman on board in the creative industry: a literature review. Int J Mod Trends Soc Sci 2(8):32–41

Eisenhardt KM (1989) Building theories from case study research. Acad Manag Rev 14(4):532–550

Ferdoos A (2005) Social status of urban and non-urban working women in Pakistan: a comparative study. PhD Thesis, University of Osnabruck

Fitzsimmons TW, Callan VJ, Paulsen N (2014) Gender disparity in the C-suite: do male and female CEOs differ in how they reached the top? Leadersh Q 25(2):245–266

Fletcher JK (2007) Leadership, power, and positive relationships

Gibbs J (2009) Dialectics in a global software team: negotiating tensions across time, space, and culture. Hum Relat 62(6):905–935

Glass C, Cook A (2016) Leading at the top: understanding women’s challenges above the glass ceiling. Leadersh Q 27(1):51–63

Gloor JL (2016) The labyrinth of leadership: female, family, and career considerations. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Zurich

Groysberg B, Abrahams R (2010) Five ways to bungle a job change. Harv Bus Rev 88(1–2):137–140

Gullette MM (2004) Aged by culture. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Gupta V, Van Wart M (2015) Leadership across the globe. Routledge, London

Gutiérrez-Martínez I, Saifuddin SM, Haq R (2021). The United Nations gender inequality index. In: Handbook on diversity and inclusion indices. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Hammoud RS (1993) Bahrain: the role of women in higher education management in the Arab region. In: Women in higher education management. UNESCO, pp 31–52

Harquail CV (2008) Alice H. Eagly and Linda L. Carli: through the labyrinth: the truth about how women become leaders

Hearn J, Piekkari R (2005) Gendered leaderships and leaderships on gender policy: national context, corporate structures, and chief Human Resources managers in transnational corporations. Leadership 1(4):429–454

Heilman ME, Okimoto TG (2007) Why are women penalized for success at male tasks? The implied communality deficit. J Appl Psychol 92(1):81

Henneberger AK, Deutsch NL, Lawrence EC, Sovik-Johnston A (2013) The Young Women Leaders Program: a mentoring program targeted toward adolescent girls. Sch Ment Health 5(3):132–143

Hines M (2004) Androgen, estrogen, and gender: contributions of the early hormone environment to gender-related behavior. In: The psychology of gender. Guilford Press, New York

Hodges EA, Rowsey PJ, Gray TF, Kneipp SM, Giscombe CW, Foster BB, Alexander GR, Kowlowitz V (2017) Bridging the gender divide: Facilitating the educational path for men in nursing. J Nurs Educ 56(5):295–299

Hoffman LW (1972) Early childhood experiences and women’s achievement motives. J Soc Issues 28(2):129–155

Hopkins MM, O’Neil DA, Williams HW (2007) Emotional intelligence and board governance: leadership lessons from the public sector. J Manag Psychol 22(7):683–700

Hopkins MM, O’Neil DA, Passarelli A, Bilimoria D (2008) Women’s leadership development strategic practices for women and organizations. Consult Psychol J Pract Res 60(4):348

Jackson LA (1989) Relative deprivation and the gender wage gap. J Soc Issues 45(4):117–134

Jacobs JA (1996) Gender inequality and higher education. Annu Rev Sociol 22(1):153–185

Jauhar J, Lau V (2018) The ‘glass ceiling’ and women’s career advancement to top management: the moderating effect of social support. Glob Bus Manag Res 10(1):163–178

Johnson NN, Fournillier JB (2021) Intersectionality and leadership in context: examining the intricate paths of four black women in educational leadership in the United States. Int J Leadersh Educ. https://doi.org/10.21428/cb6ab371.c86f3428

Jost JT, Banaji MR (1994) The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. Br J Soc Psychol 33(1):1–27

Jost JT, Banaji MR, Nosek BA (2004) A decade of system justification theory: accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Polit Psychol 25(6):881–919

Kabeer N (1988) Subordination and struggle: women in Bangladesh. N Left Rev 168(1):95–121

Kark R (2007) Re-thinking organizational theory from a feminist perspective. In: Unpacking globalization: markets, gender and work. Lexington Books, Lanham, pp 191–204

Khan AA (2013) How gender affects women entrepreneurship: experience from Pakistan. In: Short research papers on knowledge, innovation and enterprise, 2013, p 107

Khan H (2017) On escalation metaphors and scenarios. Routledge, London

Khan WA, Vieito JP (2013) CEO gender and firm performance. J Econ Bus 67:55–66

Khosrojerdi F (2015) Muslim female students and their experiences of higher education in Canada. The University of Western Ontario (Canada)

Kjeldal SE, Rindfleish J, Sheridan A (2005) Deal-making and rule-breaking: behind the façade of equity in academia. Gend Educ 17(4):431–447

Koenig AM, Eagly AH, Mitchell AA, Ristikari T (2011) Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol Bull 137(4):616

Kolb JA (1999) The effect of gender role, attitude toward leadership, and self-confidence on leader emergence: implications for leadership development. Hum Resour Dev Q 10(4):305–320

Korabik K (1990) Androgyny and leadership style. J Bus Ethics 9(4):283–292

Ladge JJ, Humberd BK, Eddleston KA (2018) Retaining professionally employed new mothers: the importance of maternal confidence and workplace support to their intent to stay. Hum Resour Manag 57(4):883–900

Landau MJ, Meier BP, Keefer LA (2010) A metaphor-enriched social cognition. Psychol Bull 136(6):1045

Latchem C, Kanwar A, Ferreira F (2013) Conclusion: women are making a difference. In: Women and leadership. Commonwealth of Learning, p 157

Laux SE (2018) Experiencing the imposter syndrome in academia: women faculty members' perception of the tenure and promotion process. Doctoral Dissertation, Saint Louis University

Lerner M, Brush C, Hisrich R (1997) Israeli women entrepreneurs: an examination of factors affecting performance. J Bus Ventur 12(4):315–339

Lippa RA (2005) Gender, nature, and nurture. Routledge, London

Liu W, Ruths D (2013) What’s in a name? Using first names as features for gender inference in Twitter. In: 2013 AAAI spring symposium series, March 2006

Lyness KS, Grotto AR (2018) Women and leadership in the United States: are we closing the gender gap? Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 5:227–265

Maranto CL, Griffin AE (2011) The antecedents of a ‘chilly climate’ for women faculty in higher education. Hum Relat 64(2):139–159

McDonald ML, Westphal JD (2013) Access denied: low mentoring of women and minority first-time directors and its negative effects on appointments to additional boards. Acad Manag J 56(4):1169–1198

Mernissi F (1995) Dreams of trespass: tales of a Harem girlhood. Perseus Books, New York

Moghadam VM (1992) Patriarchy and the politics of gender in modernising societies: Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Int Sociol 7(1):35–53

Mulcahy M, Linehan C (2014) Females and precarious board positions: further evidence of the glass cliff. Br J Manag 25(3):425–438

Murray D, Chua S (2014) Differences in leadership styles and motives in men and women: how generational theory informs gender role congruity. In: European conference on management, leadership and governance, November 2014. Academic Conferences International Limited, p 192

Pichler P (2008) Gender, ethnicity and religion in spontaneous talk and ethnographic-style interviews: balancing perspectives of researcher and researched. In: Language and gender research methodologies. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills

Pizam A (2004) Are hospitality employees equipped to hide their feelings? Int J Hosp Manag 23(4):315–316

Powell GN (2012) Six ways of seeing the elephant: the intersection of sex, gender, and leadership. Gend Manag Int J 27(2):119–141

Pratt MG (2009) From the editors: for the lack of a boilerplate: tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Acad Manag J 52(5):856–862

Richardsen AM, Traavik LE, Burke RJ (2016) Women and work stress: more and different? In: Handbook on well-being of working women. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 123–140

Ridgeway CL (2007) Gender as a group process: implications for the persistence of inequality. In: Social psychology of gender. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley

Ritter BA, Yoder JD (2004) Gender differences in leader emergence persist even for dominant women: an updated confirmation of role congruity theory. Psychol Women Q 28(3):187–193

Roomi MA, Parrott G (2008) Barriers to development and progression of women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. J Entrep 17(1):59–72

Rudman LA (1998) Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: the costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. J Personal Soc Psychol 74(3):629

Rudman LA, Glick P (2001) Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. J Soc Issues 57(4):743–762

Rudman LA, Phelan JE (2008) Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Res Organ Behav 28:61–79

Ryan MK, Haslam SA (2007) The glass cliff: exploring the dynamics surrounding the appointment of women to precarious leadership positions. Acad Manag Rev 32(2):549–572

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol 25(1):54–67

Sabharwal M (2015) From glass ceiling to glass cliff: women in senior executive service. J Public Adm Res Theory 25(2):399–426

Sahlstein E, Allen M (2002) Sex differences in self-esteem: a meta-analytic assessment. In: Interpersonal communication research: advances through meta-analysis. Routledge, London, pp 59–72

Sajjad M, Kaleem N, Chani MI, Ahmed M (2020) Worldwide role of women entrepreneurs in economic development. Asia–Pac J Innov Entrep 14(2):151–160

Santero-Sanchez R, Segovia-Pérez M, Castro-Nuñez B, Figueroa-Domecq C, Talón-Ballestero P (2015) Gender differences in the hospitality industry: a job quality index. Tour Manag 51:234–246

Schatzki TR (2001) On sociocultural evolution by social selection. J Theory Soc Behav 31(4):341–364

Schedlitzki D, Ahonen P, Wankhade P, Edwards G, Gaggiotti H (2017) Working with language: a refocused research agenda for cultural leadership studies. Int J Manag Rev 19(2):237–257

Sealy R, Singh V (2006) Role models, work identity and senior women’s career progression-why are role models important? Acad Manag Proc 2006(1):E1–E6

Sharma RR, Chawla S, Karam CM (2021) Global gender gap index: World Economic Forum perspective. In: Handbook on diversity and inclusion indices. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Shin R (2016) Gangnam style and global visual culture. Stud Art Educ 57(3):252–264

Smith P, Caputi P, Crittenden N (2012) A maze of metaphors around glass ceilings. Gend Manag Int J 27(7):436–448

Stead V, Elliott C (2009) Women’s leadership. Springer, Berlin

Surangi HAKNS (2020) Systematic literature review on female entrepreneurship: citation and thematic analysis. Kelaniya J Manag 9(2):40

Thomas AJ, Witherspoon KM, Speight SL (2004) Toward the development of the stereotypic roles for Black women scale. J Black Psychol 30(3):426–442

Unit EI (2021) Universities and entrepreneurship: meeting the educational and social challenges. Context 200:201

Varley E (2012) Islamic logics, reproductive rationalities: family planning in northern Pakistan. Anthropol Med 19(2):189–206

Vinkenburg CJ, Van Engen ML, Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC (2011) An exploration of stereotypical beliefs about leadership styles: is transformational leadership a route to women’s promotion? Leadersh Q 22(1):10–21

Vinnicombe S, Singh V (2002) Sex role stereotyping and requisites of successful top managers. Women Manag Rev 17(3/4):120–130

Wadud A (2009) Islam beyond patriarchy through gender inclusive Qur’anic analysis. In: Wanted: equality and justice in the Muslim family. Musawah, pp 95–112

Wheatley D (2012) Work–life balance, travel-to-work, and the dual career household. Pers Rev 41(6):813–831

Whittington S, Litt M (2002) Peace-keeping operations and gender equality in post-conflict reconstruction. In: EU-LAC conference on the role of women in peace-keeping operations, November 2002, pp 4–5

Williams JE, Best DL (1990) Measuring sex stereotypes: a multination study, Revised. SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks

Yousaf P (2020) Contact public sector universities. Higher Education Commission

Zaccaro SJ, Gulick LM, Khare VP (2008) Personality and leadership. Leadersh Crossroads 1:13–29

Acknowledgements

I would like to express immense gratitude to a number of people who have inspired, encouraged and assisted me through this journey. First and foremost I thank my respectable mentor Professor Dr. Lena Hipp for being a constant source of motivation and guidance throughout this accomplishment. I would also like to thank Professor Dr. Maja Apelt for her valuable guidance and insights. I would like to thank Chairman Higher Education Commission Pakistan without whose assistance I would never have been able to collect my data. Last but not the least I am extremely grateful to my family for supporting me throughout this journey.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study is self-funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The research institution to which I am affiliated, University of Potsdam, does not require ethical approval for research based on qualitative interviews that do not involve sensitive questions.

In my research, I closely followed the principles outlined in the Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research 1978) and explicitly asked study participants about their consent and provided them with the opportunity to stop the interview and nullify anything that they said in case they no longer were happy with it. For your information, I also include the link of the Ethics Committee of the University of Potsdam (https://www.uni-potsdam.de/de/senat/kommissionen-des-senats/ek) as well as the consent form, I used for my study.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lashari, M.N. Through the labyrinth: women in the public universities of Pakistan. SN Soc Sci 3, 79 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00663-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00663-1