Abstract

Coordinating services for people with disabilities requires the expertise of professionals who promote the employment and work ability of their clients. This study evaluated the effects of work ability coordinators’ educational program on behavior of professionals who support work ability of people with disabilities. The participants were 394 professionals aged from 27 to 63 (mean age 46), who attended 21 educational programs in different parts of Finland during 2016–2019. As evaluation methods we used questionnaires and content analysis. The participants’ knowledge and skills, as their capabilities to provide work ability support to people with disabilities increased statistically significantly during the educational program. Motivation meant that the participants expected to gain knowledge on the broad structure of the service system and legislation. Networking opportunities led to new, individual-based contacts and co-operation at the national as well as the regional level. Behavior change meant that the use of the solution-focused approach to work and the full range of measures to support work ability and employment of persons with disabilities in the service system had been successful. The results will guide future educational programs and policy decisions on the proficiency needs of professionals working in the service system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As populations are aging, extending working careers is globally becoming a common and essential goal to guarantee the adequate supply of labor and prevent the excessive rise of social expenditures (Vornholt et al. 2018). Actions, policies and services to support the work ability of employed and unemployed people serve this end. However, the integration and coordination of various services need improvement in many countries (Blomgren and Waks 2015).

Finland is a case in point. A variety of services, means and benefits are available to people with disabilities to support their work ability or participation in the labor market and society (Nevala et al. 2015a, b; Ratti et al. 2016). However, at the same time, this service system is fragmented and difficult to master for both people with disabilities and professionals (Liukko and Kuuva 2017). This may result in inefficient use of services and benefits, which in turn can lead to lower than optimal levels of employment among people with disabilities. Further, this decreases the inclusiveness of the labor market and the service system (Huang 2002).

Work ability support services have transformed from a system-centered approach to a person-centered approach that tailors services around the individual, rather than enforcing one size to fit all (Liukko and Kuuva 2017; Vornholt et al. 2018). Work ability coordinators work in different contexts in the service system and at workplaces. However, their work involves similar competencies, such as applying laws, policies and regulations related to social insurance, contacting the worker, and planning individually tailored work ability support services (Durand et al. 2017).

The clients of work ability coordinators are unemployed individuals or employees who have health problems or permanent disabilities, struggle to gain employment or maintain their work ability or are at risk of long-term work disability (Durand et al. 2017; Kausto et al. 2021). In most cases, work ability coordinators also guide managers and the whole organization to support work ability and well-being at work. Cooperation across different jurisdictions is an essential element of their work (Durand et al. 2017; Kausto et al. 2021).

Coordinating the various services available to people with disabilities requires the expertise of professionals who promote the employment and work ability of their clients. These professionals must have good interaction skills and a solution-focused work style, and must be able to treat the client with respect (Liukko and Kuuva 2017; Noordegraaf 2015). The professionals’ task is to guide and advise the client and to build bridges between different operating practices, client groups and service providers (Blomgren and Waks 2015; Noordegraaf 2015). According to Durand et al. (2017), a background in nursing or occupational health and safety training significantly influenced return-to-work coordinators’ practices.

Evidence of the effectiveness of the coordinator model is mixed and inconclusive. Some research suggests that the coordinator model might reduce the duration of work disability (Franche et al. 2005; Nevala et al. 2015a, b) but other studies argue that offering coordination has no benefits over usual practice (Skarpaas et al. 2019; Vogel et al. 2017). A return-to-work coordinator model may increase employee sickness absence, but decrease the risk of disability retirement, i.e., permanent exclusion from the labor market in the public sector (Kausto et al. 2021).

The Finnish Government’s key project “Career opportunities for people with disabilities (OTE)” aimed to increase the employment rate of persons with disabilities, promote positive attitudes toward their access to employment, improve their access to rehabilitation, and provide information concerning the means, benefits and services that help people find employment or continue working (Mattila-Wiro and Tiainen 2019). One main task of this project was to improve the know-how of professionals in the service system who help the general working-age population, but especially those who help people with disabilities. The project launched a new educational program and educated nearly 700 work ability coordinators working in different parts of the service system in the public, private and third sector (Mattila-Wiro and Tiainen 2019).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of the work ability coordinators’ educational program carried out during the OTE project. The evaluation concentrated on the capabilities, motivation, opportunities, and behavior of the professionals attending the educational program and working actively with people with disabilities. It was anticipated that the educational program would directly affect the success of the trained professionals in their work in promoting work ability and increase the employment rate of people with disabilities.

Materials and methods

Participants

The participants consisted of 394 professionals (29 men, 365 women), aged between 27 and 63 (mean age 46 years), whose work involved supporting work ability and employment and who took part in 21 work ability coordinators’ educational programs organized in various parts of Finland (Table 1). The participants had diverse educational and professional backgrounds and worked under different job titles in public, private or third sector organizations.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of this study was the COM-B model (Michie et al. 2011) (Fig. 1). The COM-B model of behavior has been widely used to identify the factors that need to change in order for a behavior change intervention to be effective. In our study, it identified three factors – capability, opportunity and motivation – which need to be present for any behavior to occur. In this study, the capability factor consisted of the knowledge and skills of the participants, the opportunity factor consisted of networks, barriers or facilitators, and the motivation factor consisted of benefits, satisfaction and expectations.

COM-B framework in this study (Michie et al. 2011)

Educational program of work ability coordinators

The concept and the educational program of work ability coordinators were developed in several programs and projects together with Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland, Rehabilitation Foundation, University of Tampere and Lapland, Sano Ky, and Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (Mattila-Wiro and Tiainen 2019; Nevala et al. 2015a, b). The education offered occupational refresher training and advanced training for people with varying educational and professional backgrounds.

The aim of the educational program was to increase the competence of the experts in providing specific services, means and benefits for people with disabilities, to promote a solution-focused work style, and to develop working skills in occupational networks. It was anticipated that this would contribute to the goal of the OTE project, namely to increase the employment rate of persons with disabilities.

The educational program was based on the constructive concept of learning, which considers the learner an active agent in the process of knowledge acquisition (Bada and Olusegun 2015; Huang 2002). Learning happens when learners construct meaning by interpreting information in the context of their own experiences in different parts of the service system. The work ability coordinators’ educational program lasted approximately nine months and comprised ten contact learning days, independent studies, a book summary, a network meeting, and a developmental task. This amounted to around 270 h of intensive work (Table 2).

Methods

As evaluation and data collection methods, we used questionnaires and content analysis of the participants’ written developmental tasks. Other sources of data, including long-term follow-up data, were not available.

We gathered the quantitative data using the Webropol 2.0 online questionnaires that evaluated the capability, motivation and opportunity of the participants before and after the educational program. The questionnaire was sent to 579 people, of whom 394 answered both before and after the questionnaires. The response rate was 68%. Several actions were taken to increase and guarantee a good response rate. As an example, the participants were informed by e-mail of the process of the evaluation already at the time they first signed up to the education. The questionnaires were planned to be short, accessible and easy to understand. It was also possible to fill the questionnaire in single parts which increased the easy-to-fill properties. The main concepts were also clarified for the respondents. Further, three professionals piloted the questionnaires, and the questionnaires were improved according to the feedback. In practice, the participants of the educational program were sent an e-mail that included a weblink to the questionnaire and an information letter about the basic background information of the study. The participants were also reminded twice if they had not responded within the predetermined time slot.

The statistical analyses was carried out using the SAS Statistical Programming Package. Means, standard deviations, and distributions were calculated to describe the data. The Paired Student’s t-test was used to analyze the statistical significance of the differences between the means. The differences between the paired data of the classified variables was analyzed using McNemar’s test.

The qualitative data consisted of the open answers in the questionnaires and the content of the developmental tasks. The data were analyzed using the qualitative content analysis. The conceptual analysis determined the existence and frequency of the concepts in a text (Morse 1991).

Results

The professionals’ knowledge of work ability support in terms of services, means and benefits increased statistically significantly during the educational program (Table 3). At the beginning of the education, the participants felt that they needed more knowledge especially regarding the existing wide and complex service system with various means and benefits to improve work ability and support employment of people with disabilities.

After the educational program, the professionals felt that they had better skills in the service process of work ability support than before the educational program (Table 3). The process included detecting service needs, planning suitable measures and benefits, co-operation with the client and network, the use of tools and data, and evaluation of the process. At their workplaces, the work ability coordinators advised supervisors to utilize different means to support the work ability of workers with disabilities through work arrangements, workplace accommodations, work trials, or relocations.

Motivation was analyzed through expectations, perceived benefits and satisfaction with the education. Before the educational program, the participants answered the questionnaire on the expectations they had of the educational program and how they saw their own contribution to that. The participants expected to gain knowledge of the “big picture” of the service system and support measures of work ability and employment. They also expected to gain detailed knowledge of the roles and responsibilities of different service providers and of essential legislation.

The professionals expected to participate and contribute actively, be able to critically analyze their own work habits, learn the use of the solution-focused approach to work, take the opportunity to become acquainted with other service providers, and to have opportunities to build new networks. After the educational program, the participants claimed that the educational program had benefitted themselves, their clients, their workplaces, and their networks (Table 4).

The participants were mostly very or somewhat satisfied with the educational program. Over 90% were very or somewhat satisfied with the content of the educational program, the occupational skills of the educators, and the practical arrangements of the education. The participants suggested that the educational program could be improved by offering more opportunities to partly carry out the education through networks, increasing the use of active techniques such as experiments and real-world problem-solving as teaching methods, and offering better guidance in the developmental tasks. The participants also requested more knowledge concerning the customer-oriented approach.

Opportunity consisted of networking, and barriers or facilitators. During the educational program, the participants built new networks with work ability coordinators and other service providers at both the national and regional level. All the participants also organized a network meeting with some “new” service provider to draw up a concrete network plan for work ability support. The participants claimed to have learned about each other’s expertise, services and responsibilities, the glossary specific for professionals, various tools they can use in their work, and low threshold for contacting networks.

During the educational program, the networks that mostly increased were those with workplaces, the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, and employment offices. However, established networks and common development of the networks were only partly realized. In most cases, the target of the network was a single customer and their need for work ability support. The second most common target of the network was to develop the services and common work habits of work ability support. The participants described how:

“The main principle is that the network is built on the basis of the customers’ need for the service. So that the network is a resource for the customer.”

“We have organized regular meetings with our network and worked on our common tasks.”

The barriers to and facilitators of learning included their own workplace’s work ability support strategy, resources for coordination and networking, and the service system. The opportunity to complete a developmental task related to their own work was an important facilitator. This helped the whole workplace learn together and improve the organizations’ operations as part of the service system. In addition, the developmental task helped in implementing new work habits as part of their organization. In some cases, the fragmented service system prevented the tailoring of optimal services for clients with disabilities. In addition, the employer was not always able to use the new knowledge and skills of the work ability coordinators in the best possible way in their organization.

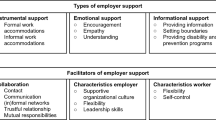

Behavior change was based on the open answers of the questionnaires and the themes of the developmental tasks. The change meant using the solution-focused approach to work, the full range of work ability support measures, and networking (Fig. 2).

The participants began to use solution-focused work styles in their daily work with their customers. After the educational program, 94% of the participants used a solution-focused approach in their work. Before the training program, the same proportion had been 66%, which meant a statistically significant increase (p < 0.0001).

The answers to the question “How do you use a solution-focused approach in your work?” were based on four themes: (1) interest in a solution-focused approach, (2) certainty in ones’ own work, (3) listening to the customer, and (4) finding more diverse solutions with a customer and a network. The participants described their solution-oriented work below:

“I consider the customers’ issues and situations from many different perspectives and I don’t accept the first solution right away.”

“I remember that everyone has a treasure chest of skills inside them.”

The participants began to use a wider range of the means and benefits of work ability support, in cooperation with wider professional networks. Special attention was also paid to the customer's capabilities, hopes and dreams. According to the participants, the networks supported both the customers and the professionals:

“I understand the need for and importance of networking.”

“Networks are a resource for the customer as well as for the professionals’ own work.”

“I can analyze the customer’s situation more broadly and guide him towards suitable services. I can also contact the professionals in my network.”

Networking led to new, individual-based contacts and cooperation between the individual participants who represented different service providers at the national as well as the regional level. The participants learnt to know and communicate with each other, and began to plan new cooperation to support customers’ work ability and opportunities to gain employment.

Discussion

The work ability coordinators’ educational program improved their knowledge regarding means and support, a solution-focused work style, and professional networks. This improved ability of the participants to guide and advise their clients and build networks with different service providers to promote employment or continuing at work.

We used both quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate the educational program. The quantitative data were based on questionnaires that were sent to the participants before and after the educational program. The total response rate was good (68%), which means that the results give a reliable picture of the educational program from the perspective of the participants. It has been documented (Converse et al. 2008; Truell et al. 2002) that response rates in surveys sent via e-mail can be lower than those sent via traditional mail. However, the time span to receive response to a questionnaire is shorter in e-mail surveys compared to the surveys that use traditional mail (Truell et al. 2002). In this study, the actions taken to ensure good response rate were considered sufficient. In addition, the participants were motivated to fill in the surveys as an integral part of the educational program.

The chain effect included the assumption that the education of professionals would increase the quality of work ability support services, and that this would increase the possibility of people with disabilities to be employed or to continue at work. This assumption requires a behavior change among the professionals, which the COM-B framework identified as requiring three factors: capability, opportunity and motivation. This framework has been used in several contexts; for example, in a qualitative study of occupational doctors in a return-to-work context (Horppu et al. 2018). Coordinating the various services available for people with disabilities requires the expertise of professionals. Capability comprised relevant knowledge and skills related to work ability support and its process.

During the educational program, the professionals learned by interpreting new information in the context of their own experiences in different parts of the service system. Most of the professionals were satisfied with the educational program, but wished that the education could be partly carried out via networks. They also wished that the teaching practices could include more solving of typical case examples and real-world problem-solving, to create more knowledge and ability to adapt the knowledge when tailoring services around the individual (Durand et al. 2017; Liukko and Kuuva 2017). This is also in accordance with the constructive concept of learning that was used (Bada and olusegun 2015; Huang 2002).

In the future, the inclusiveness should be taken more seriously into account in constructive learning approach both in traditional classroom and in online learning environments (Huang 2002). The elements like relationships, advocacy, sense of identity, commonly shared experiences, and transparency, will increase and develop inclusiveness both in working life and in service system for people with disabilities (Saunders and Nedelec 2014). More real-world cases and problem-solving exercises should be included in the education as was also suggested by the participants. The multidisciplinary networks help the professionals actively share their experiences and develop better work ability support for their customers.

Opportunity comprised networking: individual-based contacts and cooperation between participants who represented different service providers at the national as well as the regional level. The participants learnt to know and communicate with each other, and to plan new kinds of cooperation to support the work ability and employment of people with disabilities. Behavior change meant the use of a solution-focused approach to work and of the full range of measures to support work ability, networking, and clarifying the role of the work ability coordinator in the different tasks of the service system.

As the training program was an integral part of the Finnish Government’s OTE project, it also importantly contributed to the results of the larger project. One key aspect of the project was that the education of the work ability coordinators was carried out throughout the country. During the OTE project, the number of unemployed persons with disabilities decreased by 30.2%. The number of long-term unemployed people with disabilities also decreased (Mattila-Wiro and Tiainen 2019). The educational program shifted the focus away from a culture of sending away to a culture of inviting to participate. As a result of this shift, the client received work ability support to become employed or to continue at work.

Conclusions

The work ability coordinators’ behavior was influenced by the educational program via several factors related to personal capability, motivation and opportunities provided by networks. After the educational program, the participants were better able to guide and advise their clients and to build active networks with different service providers to promote employment or continuing at work. These results can guide future educational programs as well as policy decisions on the proficiency needs of professionals working in the service system. The success of the training program played an important part in the overall positive results of the “Career opportunities for people with disabilities” program.

References

Bada SO, Olusegun S (2015) Constructivism learning theory: a paradigm for teaching and learning. J Res Method Education 5(6):66–70

Blomgren M, Waks C (2015) Coping with contradictions: hybrid professionals managing institutional complexity. J Prof Organ 2(1):78–102

Converse PD, Wolfe EW, Huang X, Oswald FL (2008) Response Rates for Mixed-Mode Surveys Using Mail and E-mail/Web. Am J Eval 29(1):99–107

Durand MJ, Nastasia I, Coutu MF, Bernier M (2017) Practices of return-to-work coordinators working in large organizations. J Occup Rehabil 7(1):137–147

Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J et al (2005) Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil 15(4):607–631

Horppu R, Martimo KP, MacEachen E, Lallukka T, Viikari-Juntura E (2018) Application of the theoretical domains framework and the behaviour change wheel to understand physicians’ behaviors and behavior change in using temporary work modifications for return to work: a qualitative study. J Occup Rehabil 28:135–146

Huang H-M (2002) Toward constructivism for adult learners in online learning environments. Br J Edu Technol 33(1):27–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.00236

Kausto J, Oksanen T, Koskinen A, Pentti J, Mattila-Holappa P, Kaila-Kangas L, Nevala N, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, Ervasti J (2021) ‘Return to work’ coordinator model and work participation of employees: a natural intervention study in Finland. J Occup Rehabil 31(4):831–839

Liukko J, Kuuva N (2017) Cooperation of return-to-work professionals: the challenges of multi-actor work disability management. Disabil Rehabil 39(15):1466–1473

Mattila-Wiro P, Tiainen R (2019) Involving all in working life; Results and recommendations from the OTE key project Career opportunities for people with partial work ability. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The Behaviour Change Wheel: a new method for characterizing and designing behavior change interventions. Implement Sci. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

Morse JM (1991) Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation. Nurs Res 40:120–123

Nevala N, Pehkonen I, Koskela I, Ruusuvuori J, Anttila H (2015b) Workplace accommodation among persons with disabilities: a systematic review of its effectiveness and barriers or facilitators. J Occup Rehabil 25(2):432–448

Nevala N, Turunen J, Tiainen R, Mattila-Wiro P (2015a) Persons of partial work ability at work. A study of the feasibility and benefits of the Osku-concept in different contexts. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Helsinki.

Noordegraaf M (2015) Hybrid professionalism and beyond: (new) forms of public professionalism in changing organizational and societal contexts. J Prof Organ 25:1–20

Ratti V, Hassiotis A, Crabtree J, Deb S, Gallagher P, Unwin G (2016) The effectiveness of person-centred planning for people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Res Dev Disabil 57:63–84

Saunders SL, Nedelec B (2014) What work means to people with work disability: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil 24:100–110

Skarpaas LS, Haveraaen LA, Smastuen MC, Shaw WS, Aas RW (2019) The association between having a coordinator and return to work: the rapid-return-to-work cohort study. BMJ Open 9(2):e024597

Truell AD, Bartlett JE, Alexander MW (2002) Response rate, speed, and completeness: a comparison of Internet-based and mail surveys. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 34(1):46–49

Vogel N, Schandelmaier S, Zumbrunn T, Ebrahim S, de Boer WE, Busse JW et al (2017) Return-to-work coordination programmes for improving return to work in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011618.pub2

Vornholt K, Villotti P, Muschalla B, Bauer J, Colella A, Zijlstra F (2018) Disability and employment – overview and highlights. Eur J Work Organ Psy 27(1):40–55

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health for funding this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Development and implementation of the education was made by RT, PM-W, RM, JA, and ST. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by NN, MH, and HCH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by NN and PM-W and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. PM-W was the leader of the Finnish Government’s key project “Career opportunities for people with disabilities (OTE)”.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Riitta Malkamäki is an independent entrepreneur, who teaches about the solution-focused work style, and businesses through her consultancy, Sano KY. The other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

This research was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Informed Consent was obtained from all the individual participants of the study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from all the individual participants of the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nevala, N., Mattila-Wiro, P., Clottes Heikkilä, H. et al. Effects of work ability coordinators’ educational program on behavior of professionals. SN Soc Sci 2, 229 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00542-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00542-1