Abstract

In the context of increasingly dynamic global threats to security, which exceed current institutional capabilities to address them, this paper examines the influence of actors with insular interests who seek to leverage anxieties, grievances and disinformation for their own advantage at the expense of the public. Such actors have a common interest in political dysfunction as a means of reducing institutional controls and oversite and use combinations of divisive messaging and disinformation to advance societally suboptimal goals. We first examine the emergence of a security deficit arising from globalization, climate change, and society’s failure to develop the institutions and norms necessary to address the threats produced by these combined phenomena. We then analyze how the politics of division and disinformation have undermined the ability of political and social systems to adapt to the new global threat landscape, employing a conceptual framework that integrates perspectives from sociology and political studies with advances in the cognitive sciences and psychology. Included in the analysis is an examination of the psychological and cognitive foundations of divisive politics and disinformation strategies employed by opportunistic actors to manipulate existing cultural biases and disinform the public of the genuine threats to their well-being. Finally, we provide examples of the interaction of the aforementioned dynamics and concomitant societal opportunity costs resulting from politically fueled division and disinformation. The paper intends to integrate insights from distinct disciplines (sociology, political science, political economy, psychology and cognitive science) to construct a new conceptual framework for understanding obstacles to addressing twenty-first century global threats, and identify gaps in the capacity of dominant security paradigms to fully recognize and assess such threats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Contemporary society faces a new security threat landscape that requires global cooperation and planning on an unprecedented scale. To better assess the level of risk presented by emerging global security threats and contextualize the subsequent analysis, we begin by examining temporal changes and interactions of three separate dynamics: (1) the dramatically changing nature of threats facing the world, (2) the historical evolution of societal institutions designed to address threats and promote societal well-being, and (3) human cognitive predispositions that influence our perceptions and actions.

The changing nature of threat?

Since the middle of the twentieth century, new external threats to society have emerged that, in important respects, are qualitatively different from those of the past. These threats (e.g., climate change, environmental degradation, pandemics) are unique today insofar as they occur globally in real-time, unfolding at a dynamic pace that generally surpasses society’s current capacity to fully comprehend their causes and consequences and mobilize effective responses (Pierce et al. 2018).

Evidence documenting the nature of emerging climate related threats is vast and continuously increasing. Scientists have established with a fair degree of certainty that changes in climate and land-system uses are shifting to levels considered not reliably “safe” by climatologists to sustain human societies. If we continue at pace with current policies, the planet is on course to experience an increase in average global temperature between 2.0 and 3.6 °C—a scale of warming that could prove catastrophic to the sustainability of modern social systems. The best case scenario, according to the World Economic Forum, is a warming of only 1.5 °C, which can only be achieved by a full implementation of a global net zero carbon emissions target by 2050 (WEF 2022, p. 31). In addition, although the complexity and global nature of emerging threats complicate their measurement, recent reporting indicates that we have underestimated both the speed and magnitude of these threats (IPCC 2018; Resplandy et al. 2018; Ripple 2019). Studies continue to document newly discovered climate feedback loops that are likely to further accelerate climate change (Lai et al. 2020), suggesting that there is much the scientific community does not yet know due to the rapid pace of change. A report produced by the Grantham Research Institute, Earth Institute and Potsdam Institute on current studies of the economic impact of climate change concludes “assessments of the potential future risks of climate change have been omitting or grossly underestimating many of the most serious consequences for lives and livelihoods because these risks are difficult to quantify precisely and lie outside of human experience” (DeFries et al. 2019, p. 3). Nonetheless, others suggest that, despite some limitations of the evidence in these respects, the “overwhelming weight of scientific analysis points to environmental adjustments and cataclysmic feedback loops that will push ecosystems beyond tipping points,” and render “decarbonization efforts… mute” if not addressed quickly and comprehensively by world powers (WEF 2022, 31; see also, Kemp et al. 2022).

Certainly, past civilizations have experienced and impacted changes in climate, and suffered devastating pandemics. Pongratz et al. (2011) estimate that Genghis Khan killed so many people, that the reforestation that occurred in the wake of his conquests contributed to a moderate degree of global cooling. The Black Death, conquest of the Americas and the fall of the Ming Dynasty also impacted atmospheric cooling, but none of these events “would have affected the atmospheric CO2 concentration by more than 1 ppm” (Pongratz et al. 2011, p. 843). The Mongol invasions led to re-growth of forests in depopulated lands to such an extent that “nearly 700 million tons of carbon [was] absorbed from the atmosphere… which is equivalent to the world’s total annual demand for gasoline today” (Carnegie Science 2011). Yet, this impact on climate is dwarfed in comparison to changes currently underway, wherein the climate consequences of population growth and unprecedented energy demand are exacerbated by rapid deforestation (WEF 2022, p. 18). Since the beginning of the industrial era (1850), “human activities have raised atmospheric concentrations of CO2 by nearly 49%”—"more than what had happened naturally” over the previous 20,000 years. Between 2007 and 2022 alone, carbon concentration increased from about 380 to 415 parts per million (NASA 2022). The Mongol invasions, in comparison, had “a very minor effect” (i.e., about 1%) according to Julia Pongratz (interviewed in Pappas 2011; see also, Pongratz et al. 2011).

Climate is also accompanied by other rapidly emerging environmental threats. The planetary boundary (PB) framework, introduced in 2009 (Rockström et al. 2009) aimed to define the environmental limits within which humanity can safely operate, and an updated assessment (Steffen et al. 2015) found that four earth system processes/features (climate change, biosphere integrity, biogeochemical flows, and land-system change) are at risk of exceeding environmental limits critical to human security. Since 2015, and for the first time, researchers have filled an important gap in assessing the impact of human activity on earth systems by examining the potential impact of releasing new chemical and other “novel entities” into the environment that have the potential to cause severe ecosystem and human health problems. The researchers note that the “Production of novel entities is rapidly increasing. The chemical industry is the second largest manufacturing industry globally. Global production increased 50-fold since 1950 and is projected to triple again by 2050 compared to 2010” (Persson et al. 2022, p. 1512). The research found there are an estimated 350,000 different types of manufactured chemicals on the global market with largely unknown effects on humans and ecological systems. Critically the authors note that the rate at which these pollutants are appearing in the environment currently exceeds the capacity of governments to assess global and regional risks and control potential problems.

In addition, although pandemics have occurred for millennia, research indicates that the number and range of different pandemic diseases have grown significantly since the mid-twentieth century (Smith et al. 2014) and are likely to become worse due to a combination of increased global travel, urbanization, climate change, increased human-animal contact and public health shortages (Vaccine Alliance 2020; Settele et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2016b). What especially makes these “new” risks difficult to quantify and understand precisely is their dynamic pace. Certainly, past societies have developed sociological, political and scientific technologies to overcome pandemic diseases and other threats posed by nature (Huremović 2019). The dynamism of the new threat landscape, however, is creating non-negotiable conditions that society must address within a limited time frame to ensure societal security.Footnote 1 If we know that the potential scale of a global problem (i.e., climate change, environmental stress) is rapidly getting worse, but do not know just how much worse, or the exact speed of its intensification, an aggressively preventative approach is optimal, coupled with a much greater investment in science to enable fuller understanding (Taleb et al. 2014). Under current conditions of global environmental change competition among human actors or groups (such as, through geopolitical contests between nation-states) is irrelevant to the degree it does not address the new threat landscape sufficiently enough to sustain society.

Importantly, these environmental threats are occurring simultaneous to a rise in other forms of perceived threat linked to economic and cultural globalization, and emotive political reactions to them. Analysts argue, for example, that forces of globalization such as, deindustrialization and the rise of a “precariat” workforce have fostered mentalities of being “left behind,” or displaced in many segments of Western developed nations (Standing 2011; Silver et al. 2020). Such sentiments appear further heightened by fears of increased immigration. In Europe, rising anti-immigrant attitudes associated with the 2008 Eurozone crisis (Isaksen 2019); fringe populist political opportunists’ successful campaigns on anti-EU and nationalist discourses purporting to revive democracy (Bieber 2018); and the United Kingdom’s exit from the EU represent fissures in European supra-national identity and an insular turn through right-leaning identity politics. More recently, the “State of Hate Report” (Mulhall and Khan-Ruf 2021) found an increase in far-right extremism in Europe (see also, Wodak 2015).Footnote 2 Although the upswing in nationalist fervent is not a “new” phenomenon, the impact of such phenomena in delaying international cooperation on environmental and public health initiatives—even if only temporarily—may be enough to exacerbate environmental tipping points to an irreversible degree, given the rapid contemporary pace of climate change and environmental degradation. Such effects, moreover, are likely to interact with and compound other social, economic and political problems rooted in rising levels of inequality and uncertainty. For example, “Growing insecurity resulting from economic hardship, intensifying impacts of climate change and political instability are already forcing millions to leave their homes in search of a better future abroad” (WEF 2022, p. 9), resulting in additional problems, such as, heightened levels of xenophobia and nationalism in host societies.

The second dynamic of the new threat landscape concerns the overtime changes in the capacity of institutions and norms to promote society’s security and well-being. Significantly, scholars have documented that, in the centuries since the Renaissance, societal institutional and normative development has advanced significantly and laid the foundation for massive increases in the world’s economic and physical well-being and significant reductions in many forms of intergroup and interpersonal violence. Pinker (2011) most notably argues that the emergence of Hobbesian states that possessed independent judiciaries and monopolies on the legitimate use of force functioned to defuse inter-familial and inter-community conflicts before they escalated into lethal violence. Additional factors contributing to declines in violence over this period included the worldwide spread of inter-societal trade that incentivized greater cooperation with outsiders for mutual gain and the global rise in cosmopolitanism through literacy, mobility and mass media that facilitated a greater capacity for social empathy. Homicide rates declined from upwards of 100 per 100,000 in Medieval Europe and pre-state societies (Eisner 2003) to under 10 per 100,000 worldwide in the twenty-first century (Krug et al. 2002). Following World War II, progress continued with the creation of international governance bodies such as the United Nations (UN) and multilateral agreements on peace and trade, developments that helped establish a shared concern for mutual economic development, human rights and a collective commitment to prevent future conflict (including nuclear war) (Hough 2018). Although far from perfect—and notwithstanding the dangers of nationalism and the industrialization of mass killing witnessed in the age of modernity (Malesevic 2013)—such trends helped promote the cessation of violence throughout modern history (at least in many world regions).Footnote 3 However, societal institutions and norms designed to address security threats have stagnated more recently. Although conventional nation-state centered economic and military approaches to security remain integral to combating traditional threats, they are simply not designed to address new global threats (e. g., climate change, decreasing biodiversity, rising global inequality), or their cross-border consequences (e.g., displaced populations, global pandemics, etc.) which may escalate various forms of social conflict and unrest.

The final overtime dynamic constituting the new threat landscape refers to human cognitive capabilities, which have remained relatively constant throughout human history, with the most recent major changes occurring approximately 100,000 years ago (Shultz et al. 2012).Footnote 4

The combination of the extraordinary pace and global scale of the new external threats to human society, the historical leveling-off in the development of the institutional means and ambition to manage threats, and human cognitive limitations as old as time, is creating an ever-widening security deficit. Critically, under the stresses associated with emerging threats, human cognitive and psychological predispositions may be especially vulnerable to manipulation by actors interested in insular short-term interests rather than the collective interests of society at large. Given rising global threats and public anxieties, it is essential for society to draw on the most complete and accurate information and the best evidence-based science available to guide public policy. While never flawless, such information provides our best opportunity to understand and respond to global crises (Taleb et al. 2014). However, for particular political and economic actors in high positions of status, reliance on scientific evidenced-based political discourse may not be welcome, especially when the evidence constrains their actions or indicates that major changes in resource allocations are required. As we explain further below, without new institutional and normative practices, ongoing political manipulation of human psychological predispositions will make closing the security deficit far more difficult.

Analytic framework of the study

Cutting-edge research has begun to examine the neurological processes involved when a person evaluates socio-political information, and why “some people fall into traps of polarization more easily than others” (Zmigrod and Tsakiris 2021, p. 1). There is also emerging interdisciplinary work on neurocognitive processes and psychological dispositions which make individuals more vulnerable to misinformation (Ecker et al. 2021). The focus of this work has been primarily at the micro/individual level, however. Our analysis offers a multidisciplinary framework that connects macro-level and micro-level processes, incorporating insights from the cognitive sciences, psychology, political sociology and political economy perspectives to examine how human neurological and psychological dispositions shape human susceptibility to political manipulation in contexts of societal-level change and threats. In doing so, we undertake a literature reviewFootnote 5 to build on theories and concepts that have already been developed and tested through empirical research and construct a theoretical framework that identifies relationships between concepts (i.e., the “model” type of conceptual paper), “delineating… an entity” or problem without necessarily testing the relationships empirically using quantitative data (Jaakkola 2020, p. 19; see also, Gilson and Goldberg 2015). According to MacInnis (2011), the goal in such a paper is to “detail, chart, describe, or depict an entity and its relationship to other entities,” which is a central objective of the present analysis vis-à-vis interlinked processes of opportunism and manipulation, the facilitating role of cognitive biases in such processes, and concomitant threats to security posed by globalization and environmental crisis.

According to Whetten (1989), moreover, a strong conceptual paper should be evaluated in accordance with the extent to which it answers the question “why now”? With respect to this question, we highlight how the pressures arising from growing ecological threats and the corresponding need for rapid institutional change create powerful incentives to discredit evidence-based policies and programs by actors who wish to resist changes required for societal security. In addition, the potential impact of division and disinformation strategies is significantly strengthened by our current, and largely unrestricted social media technologies (Bakir and McStay 2018; Van Bavel et al. 2021). Manipulation has always been a threat to societal-level risk mitigation; but both the pace and scale of the evolving threat landscape creates increased incentives for political manipulation and disinformation.

The subsequent analysis examines three major questions regarding society’s suboptimal ability to be guided by evidence and science: First, what is the nature of the more impulsive and provocative strategies used by opportunistic political actors, and how do their strategies entwine with those of established “status-quo” elites to divide and disinform the public and undermine effective government adaptations to a changing threat landscape in pursuit of their goals? Second, what are the psychological and cognitive predispositions of humans that make divisive and disinformation tactics powerful strategies for opportunistic politicians and status-quo elites, particularly in communications with populations under psychosocial stress? Finally, using two case examples, how have divisive politics and disinformation tactics produced devastating opportunity costs for society as a whole, and what policy lessons can we learn from these cases moving forward?

The limits of conventional security paradigms in the context of the rising global security deficit

Though scientific research continues to document the increasing danger of global, externally generated threats to society, much of the international security literature focuses mainly on conventional intergroup threats through traditional or “realist” nation-state-centered frameworks. For example, Mearsheimer (2019, p. 46) essentially advocates for a return to the past, arguing that “the [international security] orders that will matter for the foreseeable future are realist orders that must be fashioned to serve the United States’ interest” over those of China, Russia, and other US geopolitical adversaries. As Glaser (2019, p. 51) notes, the focus in the international security literature “has shifted sharply to the return of major power competition.” However, such security paradigms are not fully equipped to guide policy and research to address the twenty-first century threat landscape due to their implicit acceptance of nation-state competition a priori as the process through which problems are (and should be) addressed.

The sub-fields of “environmental security” and “environmental conflict” have increased scholarly focus on the relationship between environmental degradation at the state or regional levels and the dynamics of armed conflict, peace building (Floyd 2010; Dalby 2002) and transnational crime (Jasparro and Taylor 2008). Other security frameworks incorporate environmental threats such as the impact of unequal land distribution and conflict over access to declining natural resources (Homer-Dixon 1994; Hough 2019; Diamond 2004). Generally, however, these frameworks align with the conventional realist, nation-state-centric approaches to security governance,Footnote 6 and as a result, they fail to recognize, or underestimate, the magnitude of the qualitative transformation of the global threat landscape and how domestic socio-political processes have helped produce it, and equally important, limit our ability to respond effectively.

Similar to the realist security literature much of the analyses of domestic leadership and politics strongly leans on a priori assumptions that domestic political systems are naturally based in competition between parties which serve constituencies with divergent interests. In effect, politics is typically framed as inherently partisan, and it is implied that socio-political communities are tribal because of such divergent interests. In this regard, many prominent authors of political leadership frame politics through rational choice and public choice perspectives, which posit the behaviors of political actors (elites and the masses alike) as based upon “strategic, instrumentally rational behavior” that primarily serves the interests of their nation, party or constituent base (Friedman 1996; Frohlich and Oppenheimer 1978; Riker and Ordeschook 1973). Even at the international level, the actions of opportunistic public actors may simply represent extensions of efforts to consolidate a niche in the domestic socio-political landscape rather than genuine responses to a foreign threat or competition. Although often overlooked in security studies, scholars have documented how political elites’ domestic interests often shape the international policies of their regimes (see, Gagnon 1994/1995). In such instances, “foreign policy” is an extension of domestically targeted goals held by political leaders to increase or shore-up their power and privilege.

Overall, the security literature does not adequately address the extent to which political opportunists and elites often pursue courses of action to advance their own insular interests at the cost to the security of the larger society and even their own constituents. To accomplish these types of political stratagems political and status-quo opportunists must manipulate pre-existing cultural constructions, such as national or racial identities, within their own societies to advance their individual interests rather than those of their declared constituent base(s). Sociological perspectives reveal how leaders are apt to manipulate social constructions such as nationalism, race and other ascribed identities which are culturally contingent and develop largely at the domestic level (see, Brubaker 2002; Fearon and Laitin 2000; Tilly 2003; Guess 2006). Opportunistic leaders, we argue, also promulgate significant and ongoing disinformation campaigns to distract the public from actual emerging threats they are facing, and from the potential strategies required to address such threats The key here is that most strategies to address threats will require greater global collaboration and regulation that can impact, at least, the short-term interests of elite status-quo stakeholders. Although the dominant security perspectives are relevant to understanding some global security threats, we argue that such perspectives are not fully equipped to identify some of the key sources of resistance to policies needed to address the global threats emerging today linked concomitantly to environmental degradation, globalization, and political opportunism and manipulation.

Opportunism and the politics of division and disinformation

Opportunism is a term used frequently by political economists whose analyses are, like their counterparts in security studies, predominantly rooted in a rational or public choice epistemology.Footnote 7 Yet, the term “opportunism” has also been employed with reference to patterns of corruption in newly democratizing societies of the global south, wherein leaders exploit the greed of lower-level politicians to form alliances (Takougang 2003) and expand their private accumulation of wealth (Tellez 2022); or enact policies which consolidate ethnic party loyalties (Ancietos 2021; Nkrumah 2021), often at the expense of broader public interests (Laurie 2016). Studies have demonstrated that political opportunism can “limit democratization and new urban governance initiatives” in Europe as well (Yanez 2004, p. 819) and further polarize parties and their supporters on issues of immigration and citizenship (Messina 2001). Notable examples from the United States are also instructive in regards to the inclination of local leaders to employ divisive campaign messaging in the interests of political expediency (with varying success) (Sullivan 1999; Rabrenovic 2007). The literature on ethnopolitical opportunism (Wilkinson 2002; Holland and Rabrenovic 2017) and peace spoiling (Stedman 1997; Kydd and Walter 2002)—wherein political strategies that are predictably suboptimal at a societal level are pursued in the interests of particular individuals or organizations—informs our use of the term in an effort to transcend narrow disciplinary boundaries, and situate analysis of transactional political opportunism within broader contexts of ecological and international security.

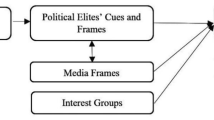

In the context of the “new” global threats, the two sets of actors most likely to pursue insular interests and resist evidence and data-based policies are political opportunists, whose primary goal is to achieve or maintain political power; and status-quo elites, whose primary interest is in maintaining or increasing their existing financial and social positions (see Fig. 1). For political opportunists, reliance on information and science as a basis of debate inherently limits the extent to which politically expedient tactics of emotional manipulation and disinformation can be used to garner support from a constituency. For status-quo elites, greater reliance on science and data almost certainly means increased government regulation and shifts in the distribution of resources from private to public goods or at a minimum away from their particular industries. Both status-quo elites and political opportunists seek to establish or maintain privileged positions through disinforming the general public and their own supporters about their genuine interests and needs. Yet, the opportunists will also engage in “divisive” strategies, attempting to manipulate and leverage the grievances and fears of their constituencies to rally support for themselves. They will also often seek to devalue the groups they have identified as a source of threat and grievance. Status-quo elites do not need to engage in explicit divisive strategies, which can be left to the work of opportunists. Rather they simply need to provide support for opportunists’ political ambitions.

Disinformation and division strategies, we ague, become more prevalent and perhaps powerful during times of rapid change and threatening circumstances when collaborative strategies to deal with common (possibly existential) threats are required but may be difficult to implement. These are strategies that operate at both subnational and transnational levels but have little to do with addressing competing national interests. Nation states, and in particular democracies, are generally weakened by such strategies (e.g., failure to address climate change and its long-term consequences).

We do not argue that all, or even most political actors are opportunistic and transactionally self-serving, or that most do not hold genuine ideological convictions. However, during periods of rising threats and growing public anxiety many actors may increasingly adopt opportunistic tactics as their dominant strategies versus the more difficult task of articulating complex policies to address genuine threats and concerns that would require some public sacrifice and increased tolerance for others. To the extent that actors believe such transactional tactics represent their best dominant strategy (in game theory parlance) some will pursue them irrespective of what other major actors do and, more importantly, whether they are beneficial to society.Footnote 8 In this way their tactics are similar to “spoilers” in conflict societies who have interest in prolonging a conflict in which they occupy higher status positions than would likely be the case in a post-conflict society.Footnote 9 Kydd and Walter (2002) concluded in their research on the Israeli and Palestinian conflict that terrorist attacks committed by extremists or fringe groups are successful at disrupting peace settlements if the attacks foster mistrust between the moderate groups on each side. Moreover, Stedman (1997, p. 5) argues that the greatest source of risk to peace settlements “comes from spoilers—leaders and parties who believe that peace emerging from negotiations threatens their power, worldview, and interests, and use violence to undermine attempts to achieve it.” In the model we are advancing the threats to security are broader and to some extent less immediate. Nevertheless, the strategies of political opportunists and status-quo elites arise because they may believe that the need to address emerging common security threats will jeopardize their insular interests, power, and worldview, or that the disruption caused by emerging threats gives them an opportunity to manipulate and leverage popular fears and grievances. For such actors partisanship is not a problem; it is an actual objective pursued to undermine the societal oversite and cooperation needed to address common threats. In such circumstances framing partisanship as a cause of political processes hides the underlying motives of the actors promoting it.

The political opportunists

Strategies employed by political opportunists and status-quo elites to advance their respective interests often differ in some major respects. For political opportunists, the first option is usually some version of divisiveness, including less obvious forms such as dog-whistling (Lopez 2014). As Heppell (2011, p. 244) argues, manipulative opportunists typically employ the tactics of “toxic leadership,” including “playing to basest fears and needs…; misleading followers through lies…; setting one group against another…; [and] identifying scapegoats.”Footnote 10 From a societal perspective, significant negative consequences can arise for those being manipulated “when the recipients are unable to understand the real intentions or to see the full consequences of the beliefs or actions advocated by the manipulator. This may be the case especially when the recipients lack the specific knowledge that might be used to resist manipulation” (Van Dijk 2006, p. 361; see also, Wodak 1987). The potential dangers of such manipulation are especially grave today when many in the public fail to recognize the gravity of unyielding global threats (e.g., pandemics and climate change). Crippling and dismantling institutional oversite and accountability systems through disinformation gives opportunists and status-quo elites much greater freedom to blind the public to a more accurate picture of the problems facing them (see Table 1). It also provides greater latitude to push divisive socio-political messaging and blame shifting. In line with this type of activity, for example, the Trump Administration gutted the “scientific expertise and administrative capacity in the executive branch, most notably failing to fill hundreds of vacancies in the Centers for Disease Control… and disbanding the National Security Council’s taskforce on pandemics” (Hetherington and Ladd 2020). Trump also fired a long line of intelligence officials and government “watchdogs” who refused to base their analyses on his political interests (Morell et al. 2020; Desiderio and Levine 2020). These actions by the Trump Administration were not exceptional; rather, they were the “apotheosis of a political approach that has animated much of the [American] conservative movement for a half century or more: undermining trust in the media, science, and government” (Hetherington and Ladd 2020).

To the extent that divisive strategies capture public attention and followers, they can become a low-cost way of advancing political careers (Bump 2017). As a result, political opportunists often attempt to accomplish their goals by appealing to the fears and grievances of some segments of the public while at the same time demonizing other segments of the public. As Gaffney et al. (2013) argue, charismatic, authoritarian-style leadersFootnote 11 use rhetoric like “we’re losing who we are” to capitalize on people’s identity insecurity, implicitly invoking national, racial, ethnic, or other outgroup biases. Thus, in the case of Brexit, leading pro-Brexit campaigners recognized the appeal of such rhetoric and advised their colleagues to focus on immigration as an alleged cause of native Britons’ social and economic problems when speaking to the public (BBC 2016). Similarly, Donald Trump’s successful 2016 presidential campaign employed divisive tactics to leverage feelings of “cultural displacement” among white working-class voters (Cox et al. 2017).

More broadly, as the need for international systems to address global threats grows, new emboldened forms of such divisive politics are emerging in nations once considered models of liberal democracy (Jenne 2018; Scheppele 2019). A PEW Research Center survey of 27 nations (PEW 2019, p. 5) found that “Anger at political elites, economic dissatisfaction and anxiety about rapid social changes have fueled political upheaval in regions around the world in recent years.” In addition to dissatisfaction and anxiety, actual levels of violence among aggrieved groups is also on the rise. The Global Terrorism Index 2020 report found that far-right attacks in North America, Western Europe, and Oceania increased by 250% since 2014 (Institute for Economics & Peace 2020). Various forms of nationalist, nativist or xenophobic trends are also emerging in other countries, including Turkey, Brazil, India, the Philippines, Poland and Hungary (Bieber 2018; Scheppele 2019).

Under conditions of stress and threat, social identities such as race, ethnicity, religion or nation often become central to people’s political attitudes and behaviors as a means of psychosocially preserving their sense of security, control, or status (Bieber 2018). However, this process does not necessarily occur automatically or naturally, but must be fostered and even manufactured to some extent (Brubaker 2002; Brubaker and Laitin 1998; Wimmer 2008).Footnote 12 Political opportunists recognize and often attempt to leverage the manipulative potential of particular cultural or social representations to support their divisive political strategies.Footnote 13 Identifying particular cultural or social representations to manipulate may result from close deliberations with advisers, but may also follow a more intuitive or trial and error process whereby an opportunistic leader may employ different narratives, identify which resonate most with targeted constituencies, and double-down on the most potent divisive messages that seem to garner maximum support. George Wallace, former governor of Alabama, presents an archetypical example of changing political positions for political expediency. In his first campaign for governor of Alabama in 1958, he stated, “I advocate hatred of no man, because hate will only compound the problems facing the South.” African American attorney J. L. Chestnut remembered George Wallace as “the most liberal judge that I had ever practiced law in front of” (WGBH n.d.). Of course, this is not the George Wallace familiar to most Americans, for immediately following his unsuccessful run for governor in 1958, he said in private to Seymore Trammell (Wallace's finance director), that “I was out-‘n-worded,’ and I will never be out-‘n-worded’ again” (WGBH, n.d.).Footnote 14 George Wallace’s moral and political U-turn and Trump’s success in the American 2016 presidential race—following the now infamous “elevator speech” about the danger of “illegal immigration” that put him on track to the White House—(Kruse 2019) are only two examples of the potential political efficacy of divisive and disinformation messaging tactics.

What leaders and other high visibility actors articulate can influence polarization and pollical violence. A study drawing on terrorism and hate speech data from 135 to 163 countries for the period 2000 to 2017 found that “politicians’ hate speech increases political polarization and that this, in turn, makes domestic terrorism more likely” (Piazza 2020, p. 431). Other research found that elites’ prejudiced speech, particularly when it is tacitly condoned by other elites, emboldened already prejudiced persons to both express and act upon their prejudices (Newman et al. 2021). The key relevance of this research for the present analysis is that elite actors can amplify the fears and prejudices of base supporters with the unspoken aim of mobilizing support for themselves, and still be able to maintain that they are not supporting violence.

In most instances, divisiveness and disinformation strategies will be used in conjunction with other tactics by political opportunists who are careful to balance their appeal to targeted segments of the public. For example, Donald Trump not only fueled white working and lower-middle class feelings of “cultural displacement” (Cox et al. 2017) through manipulation; he has also won support from evangelical Christians—a core group of supporters—via more transactional means, by promising to fill the federal courts with ultra-conservative judges sympathetic to their cultural concerns (Tackett 2019). Manipulation by opportunists is thus likely to be fused with appeal to selective incentives to build political coalitions.

Of course, left-wing opportunism exists, demonstrated recently in the Chavez/Maduro regime in Venezuela and Correa in Ecuador (Scheppele 2019, p. 314). Leftist regimes in Latin America specifically may undermine movement toward addressing the climate crisis insofar as they rely on fossil fuel production to continue provision of public services (Koop 2021).Footnote 15 And although left-wing leaders may obstruct collaborative (moderating) efforts in addressing social issues when demanding that more decisive legislation be taken on behalf of their particular constituents, progressive regimes in most societies, including the US, are more likely than their far-right counterparts to support comprehensive legislation to address the climate crisis (Korte 2021). In contrast, the exclusionary nature of contemporary right-wing politics poses an overall greater obstacle to social and political change than left-wing actors (see, Klare 2016).Footnote 16 Logically, part of right-wing resistance to legislation targeting climate change and many other global threats is rooted in the interests they share with economic elites.

The status-quo elites

In contrast to political opportunists, status-quo elites represent a range of institutional actors who gain wealth, prestige or power from currently dominant institutional arrangements. Such elites often avoid openly divisive strategies and typically seek to exert their influence through more covert methods (Page et al. 2019; Herman and Chomsky 2002). These actors include billionaires, multimillionaires and top-level executives in private-sector industries that have dominated the US and global economy throughout much of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries (e.g., fossil fuel, financial services, automotive and aerospace, chemical and industrial agriculture, media, technology and retail conglomerates). They also include media personalities and others (e.g., think-tank pundits) who see their career interests as dependent on maintaining status-quo power arrangements.

When global systems must adapt to new security realities, as is the case today, excessive concentrations of wealth and power (such as in media conglomerates) can translate into significant resistance to institutional change and adaptation (Campbell 2017; Hacker and Pierson 2016). Such resistance arises because dominant elites, who wish to maintain privileged positions, are typically tightly connected to established economic, financial and political institutions. During times with little social, economic or environmental change, such status-quo arrangements may be benign for most segments of the public (even if they are inequitable). However, during times of rapid change requiring equally rapid societal adaptation, elites with vested interests in status-quo institutions and policies will often vigorously oppose society’s need to adapt to new security challenges. Increased inequality further exacerbates this form of institutional paralysis by increasing the power of status-quo elites to resist change that would adversely affect their position.

The ability of status-quo elites to influence public opinion and resist change also has been strengthened by the increased monopolization of corporate news media enterprises. As of 2017, just six transnational corporations—Comcast/NBC Universal, 21st Century Fox/News Corp, The Walt Disney Company, CBS Corporation/Viacom, Time Warner, and Sony Corporation of America—provide most US news reporting and commentary, with more revenue than the next 20 private media companies combined (Campbell 2017, pp. 87–88). These massive corporations “are largely interested in selling their specific agenda and self-interest (free market ideology)” (Campbell 2017, p. 88) and generally avoid covering issues in ways which might signal the need to rein in the power of private enterprise and its significant role in the climate crisis. It is unlikely coincidental that ABC, CBS, NBC and FOX allocated only a combined 142 min of reporting to climate change in 2018 (Holden 2019).

Of course, not all actors who occupy such positions resist change. However, research on the top 100 billionaires in the United States (Page et al. 2019) found the great majority of the ultra-wealthy are very conservative, focused on tax cuts, opposed to environmental and financial regulation, and desirous of cutting social programs. The financial influence of these actors on political campaigns has grown exponentially in recent years. Between 1980 and 2012, “the share of campaign contributions coming from the richest 0.01% of donors rose from 15 to 40%,” and this does not account for the funds that became much easier to raise following the 2010 Supreme Court Citizens United decision (Hacker and Pierson 2016, p. 228).

Although the favored methods of political opportunists and status-quo elites may differ, they typically have at least some complementary goals, in particular, the general goal of undermining systems of institutional oversite and accountability and the capacity of political institutions to govern effectively (see, Fig. 1 and Table 1). A corollary benefit for opportunists is that divisiveness often helps paralyze governing institutions’ ability to unify communities around common goals and challenges. Although such paralysis is damaging to their society, it can help perpetuate a socio-political atmosphere of “culture wars” and other divisions, which provides further opportunities for divisive or demonizing messaging. Ironically, institutional stagnation can allow opportunists (even as they help create it) to claim they are the solution to what ails society. In this way, partisanship, tribalism and government dysfunction are largely the product of divisive manipulation (rather than a result of ‘natural’ distinctions between different segments of society) that serves the interests of opportunists and status-quo elites by helping such actors avoid oversite, accountability and the requirements of change.

Moreover, these different actors (political, corporate, etc.) do not need to conspire together to produce the intended outcome, as Mills (1956) recognized; in fact, they may pursue their objectives without any direct communication whatsoever. For example, in the UK, pro-Brexit political opportunists displaced blame for social problems onto migrants (BBC 2016; King 2015) and also fed their constituency’s anger at “the establishment” by promises to reject EU regulatory powers (Klare 2016; Evans 2015). Efforts to fuel anger against EU bureaucrats aligned with status-quo elites’ interests in avoiding the costs of government regulation. Status-quo elites can distance themselves from highly divisive political messaging but still benefit from the political paralysis that may result from such tactics. At the same time, political opportunists can align with disinformation narratives deployed by status-quo elites (without fully believing them) even when they run counter to the interests of their constituents. In addition, opportunists often receive added benefits from status quo elite disinformation strategies insofar as such strategies blind the public to actual threats they are facing and provide cover for the lack of any genuine policies to address those threats.

Importantly, with or without direct coordination, the disinformation and division strategies of status-quo elites and political opportunists, respectively, symbiotically reinforce each other’s respective efforts, which are designed to ensure that the public or segments of the public are “unable to understand the real intentions or to see the full consequences of the beliefs or actions advocated by the manipulator” (Van Dijk 2006, p. 361).

For our analysis, and as a general proposition, disinformation is a type of information that is intentionally false or presented out of context to deceive or mislead some other actor. Divisiveness is often a form of disinformation that attaches false or out-of-context narratives to “outside” groups (racial, ethnic, religious, migrant, etc.) or institutions (own government, international organization, other nations, etc.) as a source of an in-group’s grievance or threat. Divisiveness may take other forms as well, of course, apart from intentional efforts to disinform. For example, some divisive information may simply be a matter of what topics an actor focuses on or chooses to discuss. Nonetheless, the forms of disinformation and divisiveness, for the purposes of this analysis, can be aligned with five general strategies, specifically:

-

1.

Disinform the general public concerning the nature of common problems they face;

-

2.

Disinform the general public concerning the potential solutions to common problems they face;

-

3.

Divide the public and galvanize their base, often by leveraging false narratives regarding targeted groups as a source of their constituents’ grievances to advance their position;

-

4.

Divide the public and galvanize their base, often by leveraging false narratives regarding targeted groups as a source of their constituents’ fears to advance their position;

-

5.

Generate false narratives designed to diminish the perceived value of a targeted outgroup.

These five disinformation and divisive messaging strategies aligning the goals of political opportunists and status-quo elites are presented in Table 1. To be an “opportunist” or “status-quo elite” actors must use one or more of these the messaging strategies for their own advancement and at the expense the greater good or common security. The next section examines how human psychological and cognitive predispositions make us vulnerable to these strategies.

The psychological and cognitive roots of divisive politics and disinformation strategies

The strength of political divisive and disinformation strategies arises, in part, because they draw on and manipulate human cognitive, psychological and social psychological predispositions that work through the most basic functioning of neurobiology traceable to human evolutionary development (Sapolsky 2017). Much of human decision-making occurs at a subconscious level. Such subconscious processes arise because while the human brain continually absorbs tremendous amounts of information, the conscious brain can only focus on one item at a time (Miller and Buschman 2015; Wu et al. 2016a). To deal with our cognitive limitations, the human mind developed unconscious information processing shortcuts designed to facilitate rapid decision-making (Kahneman 2013). Evolution has also provided humans with cognitive emotional responses to various situations we encounter (e.g., fear, disgust and even evaluations of justice) to support the rapid appraisal of situations that might be dangerous, unhealthy or unjust.Footnote 17 For most everyday situations, our mental shortcuts and emotional responses work reasonably well. Unfortunately, our cognitive emotive shortcuts do not always produce correct assessments and can result in biased and counterproductive judgments—especially when we have incomplete or faulty information and are on the receiving end of discursive manipulation. Importantly, cognitive biases become more active and problematic when individuals or populations are threatened or stressed (Sapolsky 2017). For our purposes, the question becomes, to what extent do human cognitive and psychological limitations, especially when groups are stressed, threatened and/or manipulated, constrain our individual and collective ability to understand and address today’s increasingly complex global threats?

Nussbaum (2018) argues that fear of perceived external threats serves as the fundamental political emotion. Others contend that humans’ unconscious preference and need for the familiar is fundamental to our feelings of security (Bonn 2015). Both assessments receive support from cognitive research, which finds, for instance, that the human hormone oxytocin “makes people generous, trusting, empathetic, and expressive” toward in-group members but “aggressive and xenophobic” toward outsiders (Sapolsky 2019, p. 44). Parts of the brain involved in generating subjective fear—most notably, the amygdala (Feinstein et al. 2011; Price 2005)—are also active when we are unable to predict or control our social environments (Berns 2006).Footnote 18

Because we are predisposed to observe outgroup members with suspicion, the activation of these brain regions makes us prone to projecting negative attributions when evaluating their behavior, and potentially falsely assume that they hold deviant motivations (for examples, see Sapolsky 2017, pp. 398–402). Attributional biases are further compounded by the human tendency to distinguish “Thems” from “Us-es” and assume the worst about outsiders’ motivations. According to Jones and Davis (1965) humans are prone to attribute the behavior of strangers to their personal motives, while we assign situational causes for the same actions by ourselves or those close to us (see also, Kahneman 2013). Additionally, the tendency toward blind spot bias (in which individuals believe they are less biased than others) mitigates our capacity to acknowledge our potential ignorance about other people’s motives or social issues (Pronin et al. 2002).

Thagard (2018) argues that different emotions connect through “patterns of neural firing of semantic pointers that bind together multiple representations” of phenomena or groups, along with the language used to characterize them, which in turn may invoke overlapping emotions, such as fear and anger. For example, some of the “negative words such as ‘illegal’ used to describe immigrants in ways that make people afraid of them may also serve to prompt people to be angry that the immigrants have come to their country” (Thagard 2018, p. 1). Political opportunists can take advantage of such emotional connectivity to solidify support. Fostering fear of an outgroup makes people angry at the group, and also at parties that support or advocate for it (i.e., opportunists’ political opponents). Further anger among the opportunist’s political base can lead to increased electoral support and funding. Importantly, the ability of opportunists to make such connections is likely greatest during times of social stress and uncertainty (Thagard 2019).

Research has found that using racial, ethnic or other outgroup categories to manipulate constituencies can be politically expedient (Van Dijk 2006, pp. 368–369). However, whether threats are framed in nationalist, racial, ethnic, religious, gender, or other terms depends in part on the potential of an identity category in a given society to be linked to populist fears, grievances and anger. Central to the manufacture of socially constructed threats is the priming and linking of negative attributions to scapegoated groups by political opportunists and media elites. Significantly, even trivial or minor group differences can become prejudicially salient under effective psychological conditioning (Sapolsky 2017, p. 402).Footnote 19 When facilitated by mass and social media and situated in contexts of fear and insecurity, such priming can be executed on a massive scale, with significant political ramifications. For example, a study from Europe found strong connections between individuals’ exposure to “right-wing populist communication” and negative emotions toward immigrants (Wirz et al. 2018, p. 496; see also, Utych 2017). In the US, De Zuniga et al. (2012, p. 597) found that even “liberals who get exposed to Fox News… show less support for Mexican immigration” than non-Fox News viewers. Such messaging also has tangible effects on election outcomes. Martin and Yurukoglu (2017, p. 2565) estimate that “Fox News increases Republican vote shares by 0.3 points among viewers induced into watching 2.5 additional minutes per week by variation in position,” which translates into a 3% shift for every 25 additional minutes of viewing.

Social media communication is another significant contributor to partisanship. A 2018 review of empirical evidence on the relationship between social media and political polarization concluded that “social media shapes polarization through the… social, cognitive, and technological processes [of] partisan selection, message content, and platform design and algorithms’ (Van Bavel et al. 2021, p. 913). Moreover, a 2020 review of research on political sectarianism in America by a team of 15 scholars published in Science (Finkel et al. 2020) concluded that social media companies have played an influential role in political discourse and intensified political sectarianism. They found that social media’s impact on political discourse arises. at least in part, because “social-media technology employs popularity-based algorithms that tailor content to maximize user engagement that can increase polarization within homogeneous networks” (Finkel et al. 2020, p. 534). In addition, research that reviewed the empirical evidence on the relationship between social media and polarization concluded that social media is often a key facilitator of political polarization (Van Bavel et al. 2021).

The nature of the social environment is also pertinent to the relative efficacy of communicative manipulation by elites and opportunists; “the same recipients may be more or less manipulatable in different circumstances, states of mind, and so on” (Van Dijk 2006, p. 361). Under conditions of stress and uncertainty, many people are prone (mostly unconsciously) to gravitate toward more extreme groups and positions and simplistic but “strong” values as a way to define themselves in opposition to the “true” outsiders (Gaffney et al. 2013). To the extent such strategies capture media attention, they can become a low-cost way of advancing political interests (Bump 2017).

Perhaps not surprisingly, cognitive biases also play an integral role in the political behavior of status-quo elites. Privileged and powerful individuals may be prone to cognitive errors that arise due to a lack of external obstacles or constraints on their behavior that most other people encounter on a regular basis. Such errors may be strengthened due to a lack of interaction with the people (workers, consumers, etc.) on whom their wealth and privilege depend (Piff et al. 2012). In addition to a lack of interaction with less well-off segments of society, wealthy individuals also tend to judge their position in life relative to other individuals in their position, effectively further distancing themselves from the circumstances of the less fortunate. One study (Donnelly et al. 2018) found that most millionaires evaluated their lot in life by comparing measurable indicators of success with those of their wealthy peers, and where success was defined by consumption and accumulation that must be greater than that of their peers. Moreover, Piff and colleagues present substantial evidence to suggest that wealthier and more privileged people tend to feel the most entitled, attributing their favorable circumstances to their own abilities while failing to acknowledge the rigged nature of the systems and institutions from which they benefit (Kraus et al. 2012; Piff et al. 2012). This phenomenon is not restricted to the wealthy and may be characteristic of people more generally. Research by Molina et al. (2019, p. 1) found that just winning a game can confer a sense of entitlement. Their study found that the winners of an experimental game “were generally more likely to believe that the game was fair, even when the playing field was most heavily tilted in their favor.”

Nevertheless, the privileged positions and associated cognitive biases of wealthy persons can have significant consequences on the political process. Research suggests that such socio-psychological perceptions among the wealthy underscore their efforts to compound their privilege by financially influencing the political process in their own favor (i.e., lobbying, campaign contributions, think tanks, etc.) (Piff et al. 2018). Thus, the cognitive distortions and sense of privilege accrued by powerful actors may lead many to reject regulation and oversight. They view their success as a reflection of their own efforts, and see existing inequalities as reflecting a just social order.

Helping to propagate disinformation concerning genuine threats and solutions facing the public is a primary method of status quo elites to forestall or stop any changes that might negatively affect their activities. Likewise, promoting discord among less advantaged groups is another way to stave off demands for institutional changes, and here opportunistic political leaders, beholden in many cases to economic elites, can be of great service in protecting the status quo by fostering discord between societal sub-groups versus attempting to unite societal groups to meet common threats. This has the added benefit for economic elites of letting them distance themselves from direct engagement in divisive messaging, leaving it to the work of political opportunists. In certain respects, a similar phenomenon was identified nearly a century ago by DuBois (1999 [1935]), who ascribed the importance of racial antagonisms between poor blacks and poor whites in the post-civil war American South to the interests of “Southern economic elites” in preventing a unified working-class politics.

The opportunity costs of the politics of divisiveness and disinformation: the case of immigration

Strategies of divisiveness and disinformation have huge and often immediate negative impacts on targeted groups. However, these same actions also pose very dangerous long-term society-wide costs. The politics of threat vis-à-vis immigration is a divisive tactic that illustrates how processes of political manipulation distract large segments of the public from emerging global or national threats while serving the short-term interests of both political opportunists and status-quo elites.

The forced migration of displaced populations generated by factors such as climate change, economic inequalities, and civil conflict is projected to grow substantially over the next decades. Although forced migration predictions vary widely, virtually all are very large and troubling. Recently due to the increasing scale and rate of global warming now predicted (IPCC 2018), estimations of population displacement have increased substantially, with the total number of climate refugees now projected to rise to one billion persons by 2050 (Kamal 2017; UNFCCC 2017; Missirian and Schlenker 2017).

Opportunistic leaders consistently avoid addressing the growing economic and environmental causes of migration crises by shifting the focus onto (usually false) allegations of migrant groups’ deviance and away from the conditions they are fleeing. Misdirecting blame and demonizing such groups animates populist anger and generates support for the political opportunists who claim to be protecting their nativist constituency, and at the same time, shields them from having to advance genuine solutions to the problem of displaced persons. In the case of the United States, President Trump conflated immigrants and refugees “with the Central American MS-13 criminal gang, calling them ‘animals’ and laying the groundwork for more radical policies on the US southern border” (Jenne 2018, p. 550), including separating families and detaining children in prison-like facilities. Trump advanced this narrative even though many of the immigrants he demonized were fleeing criminal drug gang violence or seeking refuge in the US because of the impact of climate change on their agricultural livelihoods (Blitzer 2019)—both phenomena to which the US is a major contributor. The US also has been a major supplier of illicit firearms to the region, benefitting gun manufacturers and dealers substantially while further destabilizing Mexican and Central American communities (Linthicum 2018; McDougal et al. 2015). Importantly, human cognitive characteristics may make immigrants from different racial or ethnic groups easier targets for political opportunists, and this lesson is not lost on some politicians or their advisors.Footnote 20 Top Trump adviser and anti-immigrant hardliner Stephen Miller, for example, learned from conservative think-tanker David Horowitz that appealing to the public’s basest, negative emotions is a more optimal political tactic than appealing to the better angels of their nature. This is a lesson Miller operationalized in his role at the White House (Guerrero 2020).

Equally important, the vilifying narratives attached to immigrants are directly at odds with their experience and contributions to the United States or European nations. Although it is generally known that immigrants to America make up a disproportionate number of US science and medicine Nobel Prize recipients (Greshko 2018), less well-circulated are other aspects of immigrant contributions to the nation. According to most economists, immigrants generally do not take the jobs of native-born citizens, but rather complement native-born workers (Frazee 2018) and contribute positively to host economies (Fiscal Policy Institute 2012; Eitzen et al. 2017, pp. 298–299). In addition, immigrant communities (legal or undocumented) have relatively low rates of public assistance enrollment (Frazee 2018) and violent crime (Sampson 2007).

Despite the contributions immigrants make to society, it is far more politically expedient for the opportunist to blame and demonize migrants rather than accept responsibility and some of the burden needed to develop comprehensive regional solutions to migration crises. In addition, the division and distraction produced through the political denigration of immigrants indirectly serves the financial interests of status quo elites, whose disproportionate role in contributing to climate change and even violence (in the case of US gun manufacturers) is kept mostly hidden from the public, preventing increased pressure for costly regulations (to status-quo elites). As a result of divisive and disinformation strategies, as a society, we avoid addressing the actual causes of population displacement and further shield status quo elites from accountability. Political avoidance of the growing problem of population displacement by the United States and other nations will likely create intolerable conditions for millions of persons in the future while precluding widespread recognition of the role in climate change in exacerbating this problem.

The opportunity costs of the politics of division and disinformation: the case of US energy policy

Like immigration, United States energy policy over the last 40 years presents an example of an epic societal security risk management failure. Over this period, different leaders, security analysts, scientists and activists have regularly argued that a comprehensive national energy strategy is critical to the nation’s economy, security and environment. Despite these warnings, the US federal government consistently turned away from opportunities to develop a sustainable national energy strategy. The nation’s failure in this regard has meant that the US lost the opportunity to lead in developing a sustainable world energy economy. More importantly it helped set the world on a path to some of the worst predicted climate change outcomes. How these opportunities were squandered is, at least in part attributable to the interests of a narrow set of status quo elites and political opportunists and the successful disinformation and division strategies they employed to distract the public from the consequences of their policies.

Sustainable energy policy in the US got off to a positive start in 1977. Under the Carter Administration, funding of energy research and development increased substantially, reaching a high of 0.5% of all federal spending by the end of Carter’s term (Gruber and Johnson 2019, p. 80). Carter’s National Energy Plan (NEP) proposed expanding the federal role in energy policy and requiring the use of energy sources other than natural gas or petroleum (Parker et al. 1981, p. 6).

However, in 1981, the Reagan Administration derailed Carter’s renewable and sustainable energy initiatives. Control of energy decision-making went back to the private sector, federal budgets for solar R&D and conservation were cut by 85% and 97%, respectively (Grossman 2013, p. 257), and wind energy tax incentives were eliminated (Romm 2011). The dismantling of Carter’s renewable energy initiatives also aligned with broader Republican Party political strategies. Reagan promised to re-ignite the economy by getting the government out of the way (Romm 2011). However, contrary to neoliberal economic expectations, the decrease in public spending on energy-related R&D under Reagan was quickly followed by a concomitant decrease in private investment in this area (Kammen and Nemet 2005; see Fig. 2). Consequently, even today, “private industry is not sufficiently investing in the research that will create the technologies of the future—as well as the millions of jobs that would emerge from these new technologies” (Gruber and Johnson 2019, p. 107).

Declining energy R&D investment by both public and private sectors [this figure was originally published in the following article Kammen and Nemet (2005)]

At the same time, Reagan’s campaign tactics of racially coded messaging about “law and order” (Schwartz 2015), the war on drugs (Tonry 1994), and “welfare cheats” (Nadasen 2007) amplified manufactured racial threat messaging to the American white working and lower-middle classes who were beginning to experience increased economic insecurity (Coste 2012; Gomer and Petrella 2017). Republican threat constructions helped provide cover for status-quo elites’ political strategies aimed at reducing taxes on the wealthy, slashing government programs, undermining society’s safety net, and subsidizing fossil fuel industry profits.

The likely opportunity costs are obvious. If Carter’s energy investment strategies had continued and even increased, the United States would likely have become the preeminent leader of renewable energy technology systems, would have reduced the world’s dependence on Middle East fossil fuels, and most important, would have given the world an enormous head start on addressing climate change. Under this not too difficult to imagine scenario, the failure to continue Carter’s program was a monumentally suboptimal risk management security strategy.

A subsequent squandered opportunity to alter US energy policies was the Bush Administration’s response to the September 11th terrorist attacks in 2001. Following 9/11, President Bush’s presidential approval rating reached an unprecedented 90+ percent (Gallup n.d.). Although, the initial Bush administration actions against the perpetrators of 9/11 were generally viewed as successful the next major step taken by the Bush Administration, the invasion of Iraq, is now widely accepted as a historically disastrous strategic error, but whose impetus was at least partially aligned with major fossil fuel industry interests. Not coincidentally, Bush’s political career was tied intimately with Texas big oil (Faber 2010).

The shorter-term costs of the war were substantial and are well documented.Footnote 21 Less obvious but of significant consequence were the longer-term opportunity costs. Critically the invasion of Iraq precluded the possibility of the United States leading the world to a sustainable renewable energy economy and becoming a leader in the renewable energy technologies and industries of the twenty-first century. The Iraq invasion set “the world back 15 years in their attempts to rein in the climate crisis” (Roberts and Downey 2016). In retrospect, given the shock of the 9/11 attacks it is not hard to imagine the nation rallying behind an aggressive renewable energy program, much as the nation did with the space race Apollo Moon project.

Another opportunity to transform our nation’s energy systems, was again squandered following the Great Recession of 2008. The Obama Administration included substantial investments in clean energy R&D as part of the initial 2009 stimulus proposal, but this effort was short lived because the Republican-controlled House of Representatives following the 2010 mid-term elections shut down this initiative. In 2011, overall public R&D financing was cut by $1.2 trillion over ten years as part of the Budget Control Act (Gruber and Johnson 2019, pp. 81–82).

Obama’s leadership in the success of the Paris Climate Accords in 2016 yet again created another opportunity for the planet. Obama played a pivotal role in convincing China—the largest emitter of greenhouse gases—to sign the accord despite ongoing political disputes over other issues between US and Chinese leadership (Klare 2016). Although the Accords did not fully address climate change, establishing an agreement among 175 Parties (174 states and the European Union) represented an extraordinary diplomatic achievement and laid the necessary foundation for future international cooperation on this issue. Just a year later, the Trump Administration began the process of withdrawing from the Paris Agreement and gutting Obama’s Clean Power Plan (Kaufman 2019). Since then a New York Times analysis, based on research from Harvard Law School, Columbia Law School and other sources, has found that nearly 70 environmental rules and regulations were officially reversed, revoked or otherwise rolled back, significantly increasing greenhouse gas emissions and likely contributing to “thousands of extra deaths from poor air quality each year” (Popovich et al. 2020). Like his opportunistic counterparts in Europe, moreover, Trump justified these policies by stoking populist anger against an international “liberal elite” who he charged with obstructing America from realizing its national interests (Klare 2016). The withdrawal of US commitment to international treaties on environmental sustainability, among other issues during the Trump era set back positive developments toward international efforts in addressing such global problems. And, although the Biden Administration is reinstating US commitments to international treaties, a new report on national contributions to achieving the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement by the United Nations warns that government efforts are nowhere near ambitious enough to adequately tackle climate change and meet the goals of the Agreement (i.e., limit global warming to 1.5 °C) (United Nations Framework 2021).

At the same time, since the 1970s, the fossil fuel industry conducted highly successful disinformation campaigns to mislead the public about climate change (Mulvey et al. 2015; Hall 2015), making political action on this environmental challenge much more difficult. Lewandowsky et al. (2019) documented the effectiveness and success of fossil fuel industry campaigns to create public confusion about scientifically established threats such as climate change. Disinformation campaigns were pursued in spite of the knowledge fossil fuel industry scientists had about the warming effects of CO2 on the climate as early as the 1950s. Exxon’s own scientists were explicitly aware of the climate related dangers of human-caused CO2 emissions (Supran and Oreskes 2017).

The case of US energy policy thus exemplifies the complex operation and hidden but potentially very severe opportunity costs of the politics of division, distraction and disinformation. Private corporate actors, such as Exxon, engaged in carefully orchestrated disinformation campaigns to create skepticism about the dangers of global warming. The penetration of government by actors loyal to corporate interests and the fossil fuels industry further compounded the regressive influence of status quo economic elites over public policy.Footnote 22 Basically, disinformation and division strategies helped set back the nation’s and the world’s response to climate change, consigned the US, at least for the present, to an economy of the 20th, not the twenty-first century, and in doing so made the world significantly less secure in ways that cannot be readily measured.

Conclusion

A new security landscape confronts society with emerging global and, in some cases, potentially existential threats. Today’s global threats present non-negotiable, externally imposed conditions that society must address or suffer severe and possibly irreversible harm. These conditions do not bend to political positions or economic interests. Failure to address the conditions imposed by externalities such as climate change or pandemic disease means that most society members will lose. The accelerating complexity of modern society today also means that initial threats or crises can produce a cascade of unanticipated additional harmful effects (Elhefnawy 2004) and spread to places previously insulated from them (Taleb et al. 2014). Critically, it is apparent that most of these global threats are beyond the scope of our current institutional systems to control and mitigate them.

The reality of a globally interconnected world and new, rapidly emerging forms of security threats calls for corresponding increases in global cooperation and coordination versus the more standard approaches to security that focus on deterrence, intergroup aggression and competition. As Taleb et al. (2014) argue, meticulously validated scientific analysis and evidence establishes a foundation for greater cooperation among international and domestic actors by providing a clearer understanding of risk and greater confidence in what is required of them. Yet, careful vetting of evidence may be delayed or ignored because a minority of influential actors and opportunists gain from societal paralysis. As science historian Naomi Oreskes (2020) notes, governments are increasingly populated by elected officials who see “science as something that stands in the way of their political goals, and therefore must be pushed out of the way.”

At the same time, to gain or maintain power, political opportunists attempt to manipulate humans’ cognitive predispositions to create a false sense of shared identity with selected aggrieved groups while at the same time denigrating others. The divisiveness that emerges serves to divert public attention from actual threats to society and helps create the political paralysis we observe today that stifles reform.Footnote 23 Divisive strategies are also accompanied by sophisticated disinformation campaigns that disseminate fallacious narratives and distract the public from societal hazards, creating a deepening chasm between emerging global threats, and the inadequacy of global society's current institutional and normative systems to address these threats. Political opportunists and status quo elites are essentially playing a short-term game of self-interest where they win (at least in the short-term) and society loses (possibly irreversibly, given the pace and scale of developing environmental threats).

Political discourse that accepts divisive and disinformation strategies will likely lead to epic security failures. The strategies of political opportunists do not represent a “zero-sum” politics, where they and their constituencies gain at the expense of opponents. Rather, they ultimately amount to a negative-sum situation, where only the opportunists and a small number of other elites gain, while the broader society (including their constituents) lose. Finally, although negative-sum strategies can be difficult to identify precisely, they rely on divisiveness, disinformation strategies and the concomitant rejection of evidence-based public discourse that diverts society from addressing complex security threats.