Abstract

Adolescent fertility levels have shown considerable improvements globally over the past decades. However, adolescent childbearing remains high in developing countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. This study, thus, examines the levels and socioeconomic factors associated with adolescent fertility in Ghana. The study drew on data from the 2003, 2008, to the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys to perform a logistic regression analysis of socioeconomic factors associated with adolescent fertility. The results show that adolescent childbearing levels have not shown any considerable improvements over the study periods (10%, 10%, and 11% for 2003, 2008, and 2014, respectively). Socioeconomic factors such as household wealth status, working status, employer status, and employment period were associated with adolescent fertility. Female adolescents from poor households, employed and self-employed adolescents, as well as regular workers, were linked to higher adolescent fertility risks. Older adolescents, and ever married adolescents also show significantly higher childbearing risks while the risk levels steadily increased over time. Promoting economic empowerment among female adolescents and targeting employed female adolescents in fertility control measures may have considerable positive implications for adolescent fertility levels in Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescent fertility—childbearing during adolescence—remains a topic of global concern. It is noteworthy that the global adolescent fertility rates have been declining steadily for the past few decades, reducing from 65 per 1000 women aged 15–19 in 1990–1995 to 46 per 1000 women aged 15–19 in 2010–2015 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [DESA] 2017). Despite this ongoing global success, adolescent fertility still appears to be more prevalent in the developing world, where about 10% of female adolescents give birth annually, as against below 2% in the developed world (Population Reference Bureau 2013).

In sub-Saharan Africa, the adolescent fertility rate remains the highest, at 104 births per 1000 women aged 15–19 (DESA 2019). Hence, out of an estimated 62 million babies that were born to female adolescents from 2015 to 2020 globally, 46% is said to be in sub-Saharan Africa (DESA 2019). In Ghana as well, the rate remains high, estimated at 62 births per 1000 women aged 15–19 (Population Reference Bureau 2013, DESA 2017), which is considerably higher than the global average of 46 per 1000 female adolescents. Meanwhile, about half of the pregnancies leading to these births in developing countries were said to be unintended, and more than half of these were also said to end in abortion, particularly unsafe abortion (Darroch et al. 2016).

Manifold underlying causes of adolescent childbearing that have been observed in developing countries include child marriage, gender inequality, poverty, sexual violence and coercion, and inaccessibility to education and reproductive health services among several others (Williamson 2013). Unfortunately, adolescent pregnancy and childbearing have several adverse physical and, mental health, and social wellbeing consequences for both the mothers and their children, notably including limited educational attainment and income-earning potential (Williamson 2013). Besides, there is well-documented evidence on the innumerable negative health challenges associated with adolescent motherhood, that include increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as infant and maternal mortality, low birth weight, and preterm labor as well many postpartum challenges among others (World Health Organization 2004; Gronvik and Sandoy 2018).

Furthermore, in Ghana specifically, there is in-depth evidence of severe socioeconomic, psychological, and emotional challenges faced by young mothers (Gbogbo 2020). Meanwhile, studies examining adolescent fertility—a great global concern—have been inadequate in sub-Saharan Africa. Likewise, in Ghana, limited extant research appears to address this important phenomenon (Nyarko 2012; Bingenheimer and Stoebenau 2016). Thus, studies have hardly focused on estimating adolescent fertility levels in Ghana over time and their associated socioeconomic and demographic factors. Consequently, the current study examines the levels and socioeconomic predictors of adolescent fertility in Ghana for the period 2003–2014. The study, therefore, sought to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the levels of adolescent fertility in Ghana from 2003 to 2014? (2) Are socioeconomic characteristics associated with adolescent fertility levels? The findings provide a better understanding of the role of socioeconomic disparities in adolescent childbearing levels and help to appropriately shape policy directions in adolescent fertility regulation in Ghana.

Data and methods

Data source

The data for this study were obtained from the 2003, 2008, and 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Surveys (GDHS). These are three consecutive waves of the survey that were conducted as part of the global demographic and health surveys program series. The GDHS is a nationally representative survey with the primary purpose of generating current and dependable data on fertility, family planning, infant and child mortality, maternal and child health, and nutrition (Ghana Statistical Service [GSS] et al. 2015). It offers information on the full birth history of women ages 15–49 and, for that matter, is the best source of data for this study. The data were requested online from the DHS Program and approval was given to download and use the data for the analysis.

The sampling procedure used in the survey is a two-stage multistage sampling technique that used the sampling frame of Ghana’s 2000 and 2010 decennial Population and Housing Censuses. This entails the initial random selection of survey clusters in each of the regions and residential types and then systematically selecting individual households from the selected clusters in the final stage (GSS et al. 2004, 2009, 2015). The 2003 GDHS comprises 5691 women and 5015 men (ages 15–59) selected from 6251 households in 412 clusters across the country while the 2008 GDHS includes 4916 women and 4568 men selected from 6141 households in 412 clusters nationally. The 2014 GDHS also consists of 9,396 women and 4,388 men selected from 11,835 households in 427 selected clusters. The unit of analysis is sexually active female adolescents aged 15–19 regardless of their marital status. These women were in their teenage—a critical transitional period in life—and, therefore, any childbearing occurring during this period is considered as adolescent fertility whether they were legally married or not. As such, the three waves generated a total sample size of 3906 female adolescents (1113, 1037, and 1756 for 2003, 2008, and 2014, respectively) for the analysis.

Variables and measurements

The outcome variable of interest—adolescent fertility—was created from the number of children ever born (a count variable) to female adolescents in the sample and measured as a binary outcome. Respondents who had given birth to one or more children were measured as adolescent fertility (coded 1), whereas those who had no children were considered to have no adolescent fertility (coded 0). In this study, we used adolescent fertility and adolescent childbearing interchangeably to refer to childbirths during adolescence. Myriads of previous studies have strongly linked adolescent childbearing and motherhood to disparities in socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of respondents (Alemayehu et al. 2010; Rutaremwa 2013; Magadi 2017; Islam et al. 2017; Wado et al. 2019). Drawing on the existing literature, the study examines socio-economic factors such as educational attainment (no education, primary, secondary/higher), wealth status (poor, middle, rich), work status (working, not working), employer status (self-employed, someone else) and employment period (all year, seasonal) as the main independent variables of interest. Also, the study adjusted for predominantly demographic characteristics of the respondents included as the control variables of the analysis. These variables included age group (15–17, 18–19), marital status (never married, married/cohabiting, separated/divorced/widowed), religious affiliation (Christianity, Islam, Traditional/Spiritual, Others), the desired number of children (0–2, 3–4, 5 +), unmet family planning need (No unmet need, Unmet need), condom use (Yes, No), place (urban, rural) and region of residence as well as survey year (2003, 2008, 2014).

Analytic approach

The data processing and analysis were performed with the R programming language (version 3.5.2) (R Core Team 2018). Descriptive analyses were first conducted on the background characteristics of the sample together with a bivariate analysis of adolescent childbearing using a Chi-Square test of equality. Furthermore, at the multivariate analytical level, logistic regression models were used to estimate the population parameters. The logistic regression model is mathematically specified as:

where i refers to the adolescent fertility status of individual female adolescents, and β0 refers to the intercept term and the βxi term indicates the fixed effects of the predictors, whereas u refers to the error term. Three models were estimated to attain the aims of the study. Model 1 estimated the effect of socio-economic factors while Model 2 controlled for demographic characteristics of the sample. In Model 3, a full model was estimated taking into consideration place and regional residential factors. A complex survey design was also incorporated in the analyses to produce accurate results that are nationally representative. The estimated model parameters were then used to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the results.

Results

Descriptive results

This section presents the descriptive results of the background characteristics of the sample (Table 1). The majority (61.2%) of the female adolescents were younger adolescents ages 15–17 while about 39% were older adolescents ages 18–19. Also, the majority (70.0%) of the respondents had attained secondary school education or higher whereas 7.4% had not attained formal education. About 44% of the total sample resided in rich households while more than one-third (36.4%) resided in poor households. Quite expectedly, the sample was made up of predominantly never-married adolescents (92.2%) while only a few were separated, divorced, or widowed (1.2%). Similarly, the majority of the sample were expectedly unemployed (67.1%) with just about one-third (32.9%) being employed. As expected, adolescents affiliated with Christianity (85.3%) predominated the sample while the least (2.7%) were adolescents affiliated with traditionalism, spiritualism, and other miscellaneous religious denominations. The majority of the adolescents (79.4%) had not used a condom during their recent sexual intercourse with just about a fifth using a condom (20.6%). Slightly more than half of the adolescents resided in urban settings (50.5%) compared to those residing in rural settings.

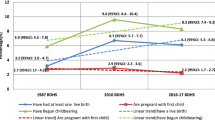

Further descriptive results were presented for the proportion of adolescent fertility in the sample by survey year (Fig. 1) and the background characteristics of the respondents (Table 2). The average proportion of adolescent fertility in the sample was 10.6% for the study period. It appeared that the level of adolescent fertility fluctuated marginally through the study period from 11.1% in 2003 to 10.5% in 2014, even though this still indicates a slight improvement from the previous years.

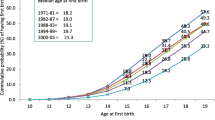

Regarding childbearing by background characteristics (Table 2), adolescent childbearing was considerably higher among older female adolescents (20.5%) than younger adolescents (4.3%). Similarly, adolescent fertility was most prevalent among adolescents without formal education (20.4%) but least prevalent among adolescents who attained secondary school education or higher (7.7%). Adolescents from poor households (15.3%) also had a considerably higher proportion of adolescent fertility than their counterparts from rich households (5.7%).

Adolescent childbearing was predominantly found among adolescents who were married or cohabiting (63.3%) as well as those who were previously in union (61.8%) than adolescents who never married or formed any union (4.9%). Employed adolescents (17.1%) also had a considerably higher level of adolescent fertility than their unemployed counterparts. For religious affiliation, adolescents affiliated with traditional, spiritual, and other miscellaneous denominations (68.4%) and (19.4%) had a higher proportion of adolescent fertility than their counterparts such as Christian and Muslim adolescents. Adolescents who had not used a condom (29.2%) in their previous sexual activities had a considerably higher fertility level than their counterparts who used a condom (9.3%). The adolescent fertility level was also higher among rural residents (13.4%) than urban residents (7.8%). Lastly, the adolescent childbearing level was higher in the Ashanti (50.3%), Brong Ahafo (44.2%), and the Volta (41.2%) Regions whereas the lowest proportion was found in the Upper West Region (13.1%).

Multivariate analysis of adolescent fertility determinants

Table 3 shows a summary of the results of the multivariate analysis. The results of the likelihood ratio test indicate that Model 2 was best fitted for adolescent childbearing since Model 3 did not add any significant improvement to the model fit. The model estimates show that a few socioeconomic characteristics were associated with adolescent fertility risk levels. In Model 1, household wealth status had an association with adolescent fertility, but the significance attenuated after controlling for demographic and residential characteristics in Models 2 and 3, respectively. Female adolescents residing in rich households had about 47% lower odds of childbearing compared to adolescents living in poor households.

Unlike Model 1, work or employment status was associated with adolescent fertility in Model 2 after adjusting for demographic characteristics of the respondents. Unemployed respondents had considerably lower odds (OR 0.35) of childbearing. Among employed adolescents, employer status also consistently had a significant association with adolescent childbearing across all the models, where self-employed female adolescents had significantly higher odds (OR 2.12) of having a child compared to adolescents employed by someone else. Employment period was significantly associated with adolescent childbearing only in Model 1, but this was attenuated after adjusting for demographic and residential characteristics in Models 2 and 3. Seasonally employed adolescents, thus, had considerably lower odds (OR 0.68) of childbearing compared to those employed all year round or regularly. Educational attainment, on the contrary, was not associated with adolescent fertility across all the models.

Some demographic factors were as well associated with adolescent childbearing as control factors in Models 2 and 3. The age of respondents showed a significant association with childbearing after controlling for residential characteristics in Model 3. Older adolescents aged 18–19 had significantly higher odds (OR 1.92) of childbearing compared to younger adolescents aged 15–17. Marital status was also associated with adolescent childbearing, in which married (OR 9.59) and formerly married (OR 9.60) adolescents had disproportionately higher odds of childbearing compared to those who never married. Demographic factors such as religious affiliation, the ideal number of children, condom use, and unmet need for family planning, on the other hand, were not associated with adolescent childbearing. Further, the results indicate a significant temporal association with adolescent childbearing. Thus, the odds of adolescent childbearing were significantly higher in 2008 (OR 2.34), and 2014 (OR 4.66) compared to 2003. Regarding residential characteristics, the place, and region of residence, on the other hand, appeared not to be associated with adolescent fertility risks.

Discussion

The descriptive findings show that female adolescent fertility levels have seen only a small change over the past one and half decades without any evidence of abating. This trend may reflect the lower modern contraceptive use (Nyarko 2020) and higher unmet need for family planning odds (Nyarko et al. 2019) among women aged 15–19 in Ghana which, in turn, may be due to a lack of effective and committed adolescent sexual and reproductive health programs over time. The lack of improvement in adolescent fertility levels over time may well have numerous dire implications for the wellbeing of young mothers and their children (World Health Organization 2004; Gronvik and Sandoy 2018; Gbogbo 2020).

Findings from the multivariate analysis have shown that a few socioeconomic characteristics were associated with adolescent fertility risk. Adolescent childbearing is associated with household wealth status and adolescents from poor households appear to be more likely to experience childbearing than their counterparts from wealthier households albeit this significance appear to attenuate after adjusting for demographic and residential characteristics. Previous studies in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing countries have consistently linked a higher risk of adolescent fertility to the poor household wealth status of adolescent mothers (Kamal 2012; Nyarko 2012; Magadi 2017; Islam et al. 2017; Wado et al. 2019). This association between adolescent fertility and household wealth status is likely mediated by contraceptive use as female residents of rich households may easily access and use contraceptives to significantly reduce pregnancy risks than their counterparts from poor households. Also, in some parts of Ghana, female adolescents from poor households may likely be given out for marriage by their parents as a means of poverty alleviation or female adolescents may get themselves pregnant because they were compelled to engage in a romantic relationship with men for their livelihood.

Moreover, the significance of female adolescent employment status has also emerged in this analysis. Non-working female adolescents were, thus, associated with significantly reduced risk for childbearing, unlike their working counterparts who were more likely to experience childbirth. Conversely, in Ethiopia, it was earlier found that unemployed teenage women were rather more likely to experience childbearing compared to those employed (Alemayehu et al. 2010), in an association that has been subsequently found to be attenuated (Kassa et al. 2019). Among employed female adolescents, self-employed adolescents were more likely to have a child than adolescents employed by someone else. This may reflect the less restrictive work-life of the self-employed female adolescent compared to their counterparts employed by someone else. On the other hand, self-employment, and adolescent childbearing may as well have a reverse association, where pregnant female adolescents may have difficulties in finding jobs for several reasons including lack of employable skills and labor market discrimination, which may induce them to opt for self-employment. In a similar vein, the period of employment may also be linked to adolescent childbearing in Ghana. Female adolescents who were employed regularly appear more likely to have a child than seasonal workers. In effect, regular employment may likely provide adequate and sustainable livelihood conducive for catering for children than seasonal employment.

Furthermore, the significance of some demographic control factors in adolescent childbearing in Ghana has emerged in the current study. The current age of female adolescents appeared positively associated with childbearing. As a corollary, older female adolescents (ages 18 and 19) were more likely than their younger counterparts to experience childbearing (Alemayehu et al. 2010; Kamal 2012; Ruteramwa 2013; Wado et al. 2019). This is quite understandable since, unlike the younger female adolescents, the older ones are legally qualified to marry and have their children in Ghana.

Also, the findings provide evidence of the positive association of marriage with adolescent fertility in the study sample. Both married or in-union female adolescents and formerly married adolescents appeared to have a disproportionately higher odds of childbearing than their never-married counterparts. Manifold studies in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing countries have indicated that marriage is a strong predictor of adolescent childbearing, and that marriage is linked to substantially higher likelihood of childbearing among female adolescents (Ruteramwa 2013; Mekonnen et al. 2018; Yakubu and Salisu 2018; Chung et al. 2018; Kassa et al. 2019). The current finding implies that most of the adolescent childbearing in Ghana, and for that matter, sub-Saharan Africa likely occurred within marital unions. This situation may happen for many reasons. For instance, sometimes, men may be compelled to marry female adolescents because they made them pregnant. Besides, in many communities particularly in Northern Ghana, younger female adolescents may be betrothed into marriage for socio-cultural reasons. These underscore the considerable adolescent fertility risks within marital unions observed in the study sample.

Temporally, even though the proportions of adolescent fertility have not seen considerable changes over time, fertility odds appeared to have soared considerably and steadily in 2008 and 2014 compared to 2003. This implies that adolescent childbearing likelihoods were worsening over time, and this highlights the urgency of devising germane social policies to tackle the phenomenon. Lastly, the significant regional disparities in adolescent childbearing levels observed in this research show the need for explorative research to unearth the potential contextual level factors underlying these disparities. It is noteworthy that this study came with a few limitations. The study drew on data from cross-sectional surveys that took a snapshot of cumulative fertility among female adolescents at certain periods, which may only assume association but not causation. As well, the study could not capture potential childbearing among female adolescents aged 13–14 owing to data limitation. However, preliminary exploratory analysis (not shown) on the outcome variable indicates that levels of childbearing to 15-year-old female adolescents and probably the younger ones were considerably lower than those of older adolescents and, therefore, may not affect the findings considerably.

Conclusions

Adolescent fertility levels have not shown any evidence of a decline in Ghana and childbearing odds appear to increase significantly over time among women aged 15–19. As a corollary, socioeconomic disparities in household wealth status and employment characteristics were strongly linked to adolescent fertility risk levels in the country. Adolescents residing in poor households, employed and self-employed adolescents, and regular workers show substantial childbearing risk levels relative to their counterparts.

Specific policies should focus on promoting socio-economic empowerment for female adolescents while focusing on residents of poor households, employed, self-employed, and regular adolescent workers as well as older female adolescents in fertility control interventions in the country. Also, to considerably reduce adolescent fertility, specially tailored policies and regulations should be devised and enforced to discourage early marriage among female adolescents in Ghana.

References

Alemayehu T, Haider J, Habte D (2010) Determinants of adolescent fertility in Ethiopia. Ethio J Health Dev 24(1):30–38

Bingenheimer JB, Stoebenau K (2016) The relationship context of adolescent fertility in Southeastern Ghana. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 42(1):1–12

Chung HW, Kim EM, Lee JE (2018) Comprehensive understanding of risk and protective factors related to adolescent pregnancy in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Adolesc 69:180–188

Darroch JE, Woog V, Bankole A (2016) Adding it up: costs and benefits of meeting the contraceptive needs of adolescents. Guttmacher Institute, New York

Gbogbo S (2020) Early motherhood: voices from female adolescents in the Hohoe Municipality, Ghana—a qualitative study utilizing Schlossberg’s transition theory. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-Being 15(1):1716620

Grønvik T, Sandøy IF (2018) Complications associated with adolescent childbearing in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 13(9):e0204327

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR), ORC Macro (2004) Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2003. GSS, NMIMR, and ICF International

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health (GHS), ICF Micro (2009) Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2008. GSS, GHS, and ICF Macro

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), Ghana Health Service (GHS), IFC International (2015) Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 2014. GSS, GHS, and ICF International

Islam MM, Islam MK, Hasan MS, Hossain MB (2017) Adolescent motherhood in Bangladesh: Trends and determinants. PLoS ONE 12(11):e0188294

Kamal SMM (2012) Adolescent motherhood in Bangladesh: evidence from 2007 BDHS data. Can Stud Popul 39(1–2):63–82

Kassa GM, Arowojolu AO, Odukogbe A-TA et al (2019) Trends and determinants of teenage childbearing in Ethiopia: evidence from the 2000 to 2016 demographic and health surveys. Ital J Pediatr 45:153

Magadi MA (2017) Multilevel determinants of teenage childbearing in sub-Saharan Africa in the context of HIV/AIDS. Health Place 46:37–48

Mekonnen Y, Telake DS, Wolde E (2018) Adolescent childbearing trends and sub-national variations in Ethiopia: a pooled analysis of data from six surveys. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18(1):276

Nyarko SH (2012) Determinants of adolescent fertility in Ghana. Int J Sci: Basic Appl Res 5(1):21–32

Nyarko SH (2020) Spatial variations and socioeconomic determinants of modern contraceptive use in Ghana: a Bayesian multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE 15(3):e0230139

Nyarko SH, Sparks CS, Bitew F (2019) Spatio-temporal variations in unmet need for family planning in Ghana: 2003–2014. Genus 75:22

Population Reference Bureau (2013) The world’s youth: 2013 data sheet. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

R Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.r-project.org/

Rutaremwa G (2013) Factors associated with adolescent pregnancy and fertility in Uganda: analysis of the 2011 demographic and health survey data. Am J Sociol Res 3(2):30–35

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [DESA] (2017) World population prospects 2017—data booklet. United Nations, New York

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division [DESA] (2019) World population prospects 2019. United Nations, New York

Wado YD, Sully EA, Mumah JN (2019) Pregnancy and early motherhood among adolescents in five East African countries: a multi-level analysis of risk and protective factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19:59

Williamson N (2013) Motherhood in childhood: facing the challenges of adolescent pregnancy. UNFPA. http://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/EN-SWOP2013-final.pdf. Accessed 22 Dec 2019

World Health Organization (2004) Adolescent pregnancy: issues in adolescent health and development. WHO. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232010000700002

Yakubu I, Salisu WJ (2018) Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health 15(1):15

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nyarko, S.H., Potter, L. Young motherhood: levels and socioeconomic determinants of adolescent fertility in Ghana. SN Soc Sci 1, 256 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00259-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00259-7