Abstract

Check-In/Check-Out (CICO) and the Daily Report Card intervention (DRC) are well-researched interventions designed to reduce challenging student behavior and improve academic and behavioral functioning. Yet each intervention has been studied within siloed literatures and their similarities and differences are not well understood by many educators. The goals of this commentary are to (1) highlight the similarities and differences between these interventions; (2) help educators and researchers understand the value of both interventions; and (3) stimulate conversation, innovative thinking, and new research that serves to reduce rather than reinforce the existing silos.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Given the high rates of social, emotional, and behavioral problems among school-aged youth (Danielson et al., 2020), general education teachers face the demanding task of educating students while working to prevent and manage challenging student behavior. The Positive Behavioral Intervention and Supports (PBIS) framework offers guidelines for providing social, emotional, and behavioral supports matched to student need (Sugai et al., 2000). In this framework, universal strategies are implemented with all students (e.g., teaching, monitoring, and reinforcing expectations for prosocial behaviors; referred to as Tier 1 level services), and targeted and individualized interventions are implemented with students who have greater need (referred to as Tier 2 and Tier 3 levels of service, respectively; Center on PBIS, 2023). To implement targeted interventions, educators must select from wide array of options and consider not only student needs, but also what is feasible given available resources, the fit within the school-wide system of support, and the evidence for the effectiveness of the intervention for the targeted outcome. The challenge of this task is exacerbated when there is overlap across similar intervention options, leaving educators unsure which intervention to implement.

Two well-researched interventions aimed at improving student functioning are Check-In/Check-Out (CICO; also called the Behavior Education Program [BEP]; Hawken et al., 2020) and the Daily Report Card intervention (DRC; also called the Daily Behavior Report Card [DBRC]; see Owens et al., 2020b, for review). Both involve identification of goals for the student, provision of feedback to the student from a caring adult, and provision of positive reinforcement strategies at school and home to motivate the student (Hawken et al., 2020; Owens et al., 2012; Volpe & Fabiano, 2013).

Both interventions are extensions of the home-school note (Dougherty & Dougherty, 1977), designed to serve as efficient, targeted interventions for students needing support beyond Tier 1 strategies, and both have been shown to be acceptable to teachers (Girio-Herrera et al., 2021; Hawken et al., 2014). However, each intervention emerged from, and exists within, siloed research literatures. CICO was developed within the positive behavior support framework and was designed as a Tier 2 intervention to target behaviors aligned with schoolwide expectations (Hawken & Horner, 2003). The initial CICO handbook was published in 1995 (Warberg et al., 1995) and its earliest evaluations were published in the special education literature (e.g., Filter et al., 2007; Hawken & Horner, 2003) with later publications in the school psychology literature (e.g., Miller et al., 2015). In contrast, the DRC was developed within the behavior therapy literature to address the challenging classroom behaviors demonstrated by students with, or at risk for, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The earliest evaluations of DRC were published in the clinical psychology literature (e.g., Ayllon, et al., 1975; Blechman et al., 1981; Lahey et al., 1977), with later publications appearing in the school psychology literature (e.g., Fabiano et al., 2010; Holdaway et al., 2020). It is interesting that in articles focused on either intervention, authors have rarely acknowledged the other intervention, leaving the relative nuances, advantages, and disadvantages of each intervention unspecified. Given that educators may focus on familiar sources of information in their search for interventions (Farley-Ripple et al., 2018), they may select one intervention over another without having accessed critical information that may best inform their intervention selection decision.

In this commentary, we integrate the literatures of these two commonly used interventions for behavioral concerns to highlight the similarities and differences between them, help educators and researchers understand the value of both interventions, and develop a future research agenda that builds upon strengths of these two historically disparate literatures. We begin by reviewing the similarities and differences across the two interventions. Next, we review the current evidence bases for each intervention. Finally, we summarize how these siloed literature bases can be combined to inform next steps for practice and research.

Similarities

Guiding Theory and Mechanisms of Behavior Change

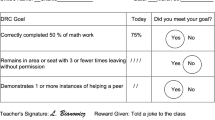

There is considerable overlap between the key features of CICO and DRC. In conceptual terms, both interventions are grounded in behavioral theory and rely on the principles of operant conditioning. Behavior change is thought to occur through the mechanisms of antecedent cues, precorrection, clear expectations, contingent reinforcement, specific praise, and consistent and effective responding to rule violations (Hawken et al., 2020; Owens et al., 2020a). In particular, when applying each, an educator reviews the student’s goal at the start of the day or period (clear expectation, antecedent cue, and precorrection). When the student demonstrates the desired target behavior, teachers offer contingent behavior specific praise, and when the student demonstrates an undesirable target behavior, the student receives corrective feedback (i.e., a tally or a lower score on their card). In short, a reward is either provided or withheld contingent upon their overall performance toward their daily goal. Finally, a supportive relationship with a caring adult in the school is thought to facilitate motivation for behavior change and maximize the value and saliency of the feedback provided (Hawken et al., 2020; Owens et al., 2020a). Both interventions use goal-setting and operant procedures to reduce disruptive behavior and/or to increase or maintain prosocial behavior, both of which contribute to enhanced academic outcomes (Horner et al., 2010). Student progress toward their goals is tracked throughout the day and online resources can be used to aid in data tracking (CICO: www.pbisapps.org/products/cico-swis; DRC: www.dailyreportcardonline.com). Each intervention emphasizes the need for a morning check-in, feedback throughout the day, an afternoon check-out, home–school communication, and data-based decision making (Filter et al., 2022; Owens et al., 2020a).

Fit within the School-Wide Systems of Support

The definition of Tier 2 services is variable across school districts and can include a broad range of interventions. Within PBIS, Tier 2 practices are defined as “targeted support for students who are not successful with Tier 1 supports alone. The focus is on supporting students who are at risk for developing serious behavior problems before they start. In essence, the support at this level is more focused than Tier 1 and less intensive than Tier 3 (Center on PBIS, 2023). Tier 2 level services align closely with school-wide expectations, are continuously available, require low effort by teachers, are flexible to match individual student needs, and are based on assessment procedures. In addition, the PBIS website recommends that Tier 2 level services include one or more of the following: increased practice with self-regulation or social skills, increased adult supervision, increased precorrectin, increased opportunity for positive reinforcement, and increased focus on the possible function of the behavior problem. In contrast, Tier 3 level interventions are more individualized and intensive than Tier 2, are often implemented by multidiscinplinary teams, developed based on a comprehensive understanding of the student’s history, and often involve wrap-around services (OSEP Technical Assistance Center on PBIS, 2020).

Although the DRC was developed within the clinical psychology literature and may be thought of by some as a Tier 3 level of service, we argue that both the CICO and DRC can be implemented in a manner consistent with Tier 2 levels of support. Namely, they both build directly from Tier 1 classroom management strategies (e.g., praise, use of rules, and feedback about the rules) and focus on increasing precorrection (e.g., goal review at the start of the or period), practice with self-regulation or social skills, and opportunities for positive reinforcement. Both involve increasing adult supervision of the student but can be feasibly implemented by general education teachers over several months (e.g., Holdaway et al., 2020; Karhu et al., 2019; Owens et al., 2012). Further, both the DRC and CICO can be developed using a brief baseline assessment of child behavior and both involve simple home–school communication rather than formal wrap-around services or services provided by a multidisciplinary team.

Targeted Behaviors

A primary goal within a multitiered system of support is matching an intervention to the student’s specific needs. Both CICO and the DRC target behaviors that align with school-wide expectations (e.g., being responsible, respectful, on task) and that match student needs. Within the psychology literature, the DRC has been primarily studied with students with or at risk for ADHD (Pyle & Fabiano, 2017) and/or with externalizing problems (Vannest et al., 2010; Waschbusch et al., 2016). Common target behaviors include staying on task, staying in the assigned area, raising hand before speaking, following instructions, working quietly, and work completion or accuracy. Within the positive behavioral support and school psychology literature, CICO has typically been studied with students with externalizing problems broadly (Hawken et al., 2014; McIntosh et al., 2009). Given the connection of CICO to PBIS school wide expectations, target behaviors in some studies are broad, such as be safe, be respectful, be responsible (Eklund et al., 2019), whereas others are more specific to the student (e.g., blurting out, talking back, out of seat, threatening gestures, not following teacher directions, throwing objects; Dart et al., 2015). An expert panel claimed that CICO can be especially helpful in targeting “attention-maintained behavior and performance deficits” (Filter et al., 2022, p. 8). Determining an appropriate Tier 2 intervention for a student should ultimately be informed by the ability of the intervention to disrupt the factors that are maintaining problematic behaviors, rather than prescribing interventions based on descriptive or diagnostic categories. Thus, despite the siloed literatures, DRC and CICO have been studied with students with similar disruptive behaviors and are broadly applicable to students with or at risk for problems in attention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, noncompliance, and conduct problems.

In addition to externalizing difficulties, researchers have advocated for the use and adaptation of both CICO and the DRC for addressing student internalizing difficulties (e.g., anxiety, depression). Internalizing difficulties may be less readily detected, particularly in the classroom setting, yet pose risk for difficulties engaging in academic tasks, learning problems, peer challenges, and academic impairment (e.g., Jones et al., 2019). Despite the need to address these concerns, less guidance is available for addressing internalizing concerns in school settings compared to externalizing concerns (Weist et al., 2018). For the DRC, recommendations for its use with internalizing concerns include combining the DRC with other behavioral intervention strategies, such as a fear hierarchy and exposures, and creation of specific goals related to approach behaviors and use of coping strategies (see Conroy et al., 2022). Likewise, in recent years, several studies utilizing single-case designs have demonstrated the preliminary effectiveness of CICO for internalizing problems (e.g., Kladis et al., 2023).

In summary, CICO and DRC are relatively aligned in their purpose, hypothesized mechanisms of action, targeted behaviors, and core procedures, and both have been studied and used as a Tier 2 level of service. However, nuanced differences between CICO and DRC may be present in the specificity of target behaviors and goals, the nature of feedback provided, and implementation personnel and resources. It is worth discussing these nuances because they offer insights for improving the utility of each intervention and serve to stimulate ideas for future research.

Differences

Specificity of Target Behavior and Goals

Consistent with the CICO manual (Crone et al., 2010), the behavior contract (i.e., referred to as the Daily Progress Report) outlines school- or classroom-wide behavioral expectations that are often consistent across all students (e.g., Be safe, be respectful, be responsible). These behaviors are typically rated on a 3-point scale (e.g., 0 = Try again, 1 = OK, 2 = Great!) representing the degree to which the student followed the expectation. During the morning check-in, the mentor and student set a daily goal for the percentage of points to earn (e.g., 80% of points across all periods; Hawken et al., 2015, 2020). However, in a review of adaptations to the CICO protocol, it was reported that about 30% of reviewed studies made alterations to the goals to individualize them to student need, such as modifying the percentage of points for the goal or adding a social skill goal (Majeika et al., 2020). Thus, the goals on the CICO card are often similar across students but can be individualized.

In contrast to the Daily Progress Report, goals on a DRC have been individualized to the student’s areas of impairment (Pyle & Fabiano, 2017) rather than based on school-wide expectations. DRC goals are often specific to (1) the child’s unique challenges (e.g., completes at least 3 steps in a morning routine); (2) a time of day (e.g., keeps hands to self during transitions with 4 or fewer mistakes), or (3) academic productivity (e.g., completes 50% of math work). In some cases, DRC goals are tracked as frequency counts (e.g., number of interruptions) or percent of work completed (e.g., Fabiano et al., 2010; Owens et al., 2012). It is recommended that teachers gather baseline data for 3 to 5 days before starting the intervention to inform the initial goal criteria, which should be set at a level that ensures student success more days than not (Owens et al., 2012; Vujnovic et al., 2014). As students achieve their goal, the criterion for success is adjusted to a higher standard to gradually shape student behavior into the typical range. However, there is variability across DRC studies, with some using a 3-point rating for each target (similar to CICO) and some using specific counts or percentages (e.g., Jurbergs et al., 2010; Holdaway et al., 2020).

Nature of Feedback

Given the differential specificity of the goals, the nature of feedback provided to students may also differ. With CICO, emphasis is placed on teachers providing positive and corrective feedback during transition periods, such as at the end of lessons or end of the school day (Filter et al., 2022). However, in some publications, it is recommended that teachers provide feedback more than once per hour (Hawken et al., 2020). In contrast, when implementing a DRC, teachers are encouraged to provide performance feedback throughout the day when each instance of the target behavior occurs (i.e., at the point of performance), including both labeled praise for working toward their goal (“Thank you for waiting to be called on before speaking”) and corrective feedback for the undesirable behavior (“Oops! That’s an interruption. I’ll make a mark on your card”). This recommendation likely emerged as a result of the DRC being studied primarily with students with ADHD (Fabiano et al., 2010; Owens et al., 2012) because students with ADHD benefit from specificity and immediacy of feedback given challenges with self-evaluation and regulation (Sagvolden et al., 1998; Neef et al., 2013). In addition to providing praise for desired behavior; creating a goal that limits the amount of disruptive behavior (with contingent reinforcement for doing so) is also important for shaping behavior of children who struggle with self-regulation (Rosen et al., 1984). In addition, teachers are encouraged to check-in with the student and offer encouragement about performance on goals during transition times and at the end of the day. Thus, the DRC may result in more targeted feedback to the student relative to CICO, in part due to the targeted behaviors for which the DRC was originally developed.

Personnel and Resources

The typical models of implementation for CICO and the DRC differ with regard to school personnel involved, the time requirements for personnel, and the associated costs and resources for implementation. The prototypical implementation model of the CICO intervention includes an identified CICO coordinator (e.g., school counselor) who oversees the school’s CICO program (Hawken et al., 2020). This coordinator is responsible for checking students in and out (or assigning mentors to do this), awarding points, providing reinforcement, and coordinating home–school communication (Hawken et al., 2020). The classroom teacher(s) is involved by providing ratings throughout the day and feedback to the student at the end of lessons, with an estimated daily time commitment of 5–10 min each day (25–50 min/week; Schaper, 2023). A district-level coach may facilitate scaling-up the intervention across the district (Hawken et al., 2015). The CICO manual estimates the CICO coordinator should spend 10–15 h per week on CICO-related duties, which would support 15–20 students in elementary or 20–30 students in secondary settings (Crone et al., 2010). There is no definitive timeline for the CICO intervention or benchmarks for progress monitoring, yet implementation experts estimate that CICO should be implemented for 6 weeks per student (Hawken et al., 2015).

With the DRC intervention, the classroom teacher is typically responsible for all aspects of implementation, including the morning check-in, providing feedback throughout the day, reviewing the DRC at the end of the day, and ensuring communication with caregivers. A consultant (e.g., school counselor, school psychologist) may be available to assist with the initial development of the intervention, implementation supports, and to assist with communication with caregivers (see Owens et al., 2020a). An economic evaluation of different models of DRC implementation (i.e., with face-to-face implementation supports versus online implementation support) tracked consultant and teacher time spent in DRC development and implementation tasks. In the face-to-face consultation models, teachers spent 3 h in the initial workshop to learn about the DRC, followed by a 1-h target behavior identification and analysis interview, and a 1-h DRC development meeting (i.e., including reviewing baseline data, finalizing the DRC, and launching the intervention with the student). Once the intervention was launched, the intervention implementation and data tracking required about 15 min per week and meeting with the consultant required about 5 min per week for 8 weeks. These times were cut in half when using an interactive guided online platform (Owens et al., 2020a). With regard to benchmarks for success, evidence suggests that for elementary school students, large changes in student behavior can occur within 1 month of implementation, with incremental small gains continuing into the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th months (Holdaway et al., 2020; Owens et al., 2012).

At first glance, CICO may require greater weekly time of the CICO coordinator than that required by DRC consultant (if one is used), and similar time commitments may be expected from teachers. However, if a school psychologist or PBIS team is supporting all teachers with a DRC, the personnel resources required to support the Tier 2 interventions is likely similar. The use of an online component to support teachers’ use and tracking of the DRC can reduce the time burden for consultants and teachers (Owens et al., 2020c; DRCO; Mixon et al., 2019). The time- and economic-savings of the CICO online data tracking system (CICO-SWIS; May et al., 2003) have not been investigated. Further, there are research-based benchmarks for the magnitude of behavior change that can be expected over time given the resources needed for implementation and progress monitoring (Holdaway et al., 2020; Owens et al., 2012), whereas such benchmarks are not available for CICO, leaving their differences in resource inputs per student over time unclear.

In summary, at their core, CICO and the DRC are similar interventions, with similar goals, based on similar theoretical underpinnings. There may be nuanced differences (e.g., goal specificity, personnel and resources involved) that are perhaps more salient in their written manuals and recommendations than in actual practice, as modifications of both interventions in practice may be common. Given the similarities and differences of the interventions, as well as their siloed existence across bodies of literature, it is important to consider the effectiveness of each intervention.

Evidence of Effectiveness

CICO

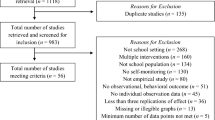

In 2014, it was reported that CICO was being used in over 3,000 schools, yet no review had systematically examined the effectiveness of the intervention (Hawken et al., 2014). Since then, five systematic reviews (Hawken et al., 2014; Klingbeil et al., 2019; Maggin et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2017; Wolfe et al., 2016) and two meta-analyses (Drevon et al., 2019; Park & Blair, 2020) on CICO have been conducted. Klingbeil et al.’s (2019) review will not be discussed here given its exclusive focus on modified versions of CICO. The remaining four systematic reviews varied in their criteria for evaluating methodological rigor and reached different conclusions. In the earliest review, Hawken et al. (2014) established their own methodological inclusion criteria, resulting in 28 included studies (eight group designs, 20 single-case designs; SCDs). They concluded that group design studies supported small to large effects of CICO whereas SCDs supported “questionable” effectiveness (Hawken et al., 2014). Maggin et al. (2015) implemented more stringent methodological inclusion criteria following What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) standards. They found that (1) no studies met methodological rigor and contributed strong evidence without reservations based on WWC standards; (2) eight SCDs contributed to the evidence with reservations; and (3) no group-based studies contributed any evidence for CICO (Maggin et al., 2015). In contrast to these reviews describing mixed evidence, Wolfe et al. (2016) used alternative methodological inclusion criteria (i.e., Horner et al., 2005) and concluded that 16 studies (15 SCDs) supported CICO as an evidence-based practice for addressing attention-maintained behavior. Finally, in their review of five studies (4 SCDs), Mitchell et al. (2017) also concluded that CICO was an evidence-based practice based on the 2014 Council for Exceptional Children Standards, given that there was a proportionately greater number of studies with positive effects than those with neutral or mixed effects.

In an attempt to clarify the level of evidence for CICO, Drevon et al. (2019) pooled the effects from 32 (31 SCDs) of the articles in the aforementioned systematic reviews and concluded that 43% of studies met WWC Standards Without Reservations, 19% met With Reservations, and 38% did not meet the standards. CICO had a large effect on behavioral outcomes (g = 1.22), with no significant moderation by grade level (i.e., secondary vs. elementary). In Park and Blair’s (2020) meta-analysis of group design studies, just one of the six included studies met WWC Standards Without Reservations (i.e., Simonsen et al., 2011), and the remaining five studies did not meet the criteria. Across the 146 students included in the meta-analysis, there was a moderate effect of CICO (g = 0.42), with a significant moderation effect such that outcomes were significantly stronger (g = 0.70) for elementary school students relative to middle school students (g = 0.27). Thus, meta-analytic studies demonstrate moderate to large effects of the CICO, that may be moderated by grade level, from studies of variable quality.

DRC

At least three reviews (Barth, 1979; Chafouleas et al., 2002; Riden et al., 2018) and three meta-analyses (Iznardo et al., 2017; Pyle & Fabiano, 2017; Vannest et al., 2010) summarize the group design and SCD studies for the DRC. In its earliest review, 24 studies supported the effectiveness of the home-based reinforcement of school behavior system (Barth, 1979), although it is unclear if the interventions across the studies were consistent with current models and definitions of the DRC. An updated review by Chafouleas et al. (2002) concluded “widespread endorsement [of the DRC] cannot be made without caution” (p. 166) given limited research, serving as a call for additional research in applied settings. Between 2007 and 2017, Riden et al. (2018) identified 11 such studies (3 SCD) examining the effects of DRCs in academic settings. They concluded that the DRC was associated with small to moderate impact for students with a variety of academic and behavioral concerns (Riden et al., 2018). None of these reviews implemented stringent methodological review criteria.

Meta-analyses of SCD studies have generally supported positive effects of the DRC. Vannest et al. (2010) conducted the first meta-analysis of SCD studies examining the effectiveness of the DRC for children with a variety of presenting problems. They identified 17 studies and evaluated the methodological rigor using criteria recommended by Horner et al., (2005), classifying 5 studies as having “strong” to “very strong” methodological rigor. The meta-analysis revealed an improvement rate difference (IRD) effect size of 0.61. Intervention effects were not moderated by grade level (i.e., secondary vs. elementary) or target type, but effects were moderated by the degree of home–school collaboration and daily time using the DRC (i.e., 1 h vs. > 1 h daily). Pyle and Fabiano (2017) focused their meta-analysis on SCD studies that used the DRC as a stand-alone intervention for children with ADHD. Fourteen studies contributed to large and consistent IRD ESs (ranging from 0.59 to 1.00; with one exception). Student age (ages 4–14) and gender and the degree of home–school communication did not moderate outcomes. The authors coded the methodological rigor of the 14 studies for adherence to WWC standards, treatment integrity, and observer awareness of treatment condition. Stronger outcomes were found among studies with higher methodological rigor compared to those with lower rigor. These findings highlight the potential undesirable impact of combining higher and lower quality studies when summarizing the effectiveness literature.

In the only group design meta-analysis of the DRC, Iznardo et al. (2017) identified seven group studies of the DRC for children with ADHD, focusing specifically on the outcomes of on/off task behavior and rule violations. The authors did not implement stringent methodological quality coding or inclusion criteria. Across studies, the average Hedge’s g ES was 0.59, with stronger effects found for studies using direct observation of outcomes. The authors concluded that the DRC is an effective intervention for youth with externalizing difficulties (Iznardo et al., 2017).

In summary, the evidence for both interventions is relatively strong, showing via both single-case design studies and randomized control trials that these interventions produce moderate to large change in observed disruptive, on-task, and classroom rule following behaviors, and teacher-rated symptoms and functioning. Change in academic outcomes is mixed, but promising. Such changes have been found across elementary and secondary school students for both interventions, with mixed evidence regarding the equivalence of CICO across grade levels (Drevon et al., 2019; Park & Blair, 2020) whereas the DRC has been found to be equally efficacious across grade level (Pyle & Fabiano, 2017; Vannest et al., 2010). Although replication is required, the DRC has evidence for facilitating student progress toward goals on student’s Individual Education Plan (Fabiano et al., 2010). In addition, the methodological rigor varied greatly across studies, which can further exacerbate the challenges faced when making an informed decision about what constitutes an “evidence-based” intervention. To facilitate such decision making, we leveraged this brief review and literature synthesis to offer guidelines to help educators and researchers make decisions about when to use each intervention.

Considerations and Guidelines

A primary lesson from our brief review is that both interventions have evidence of effectiveness, and we argue that there are more similarities than differences between these two interventions. Indeed, some of the perceived differences between the two interventions may be more a function of the siloed disciplines in which they were developed and semantic in nature rather than reflecting actual differences in the interventions. Thus, both interventions have sufficient support to be recommended as front-line interventions for students demonstrating challenging classroom behavior that are not otherwise addressed with Tier 1 level supports. We note that studies evaluating the DRC started in the 1970s well before the PBIS framework moved into conventional practice. Thus, historically the DRC has typically not been characterized as a Tier 2 or Tier 3 intervention and has not been acknowledged much within the PBIS framework. Given the definitions of Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions (Center on PBIS, 2023), we argue that both DRC and CICO can be used at both Tiers. For example, both CICO and DRC can be effective when applied in the general education classrooms (e.g., Holdaway et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2015; Owens et al., 2012; Simonsen et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2012) and when employed with students receiving special education services in integrated and self-contained classrooms (Fabiano et al., 2010; Hawken & Horner, 2003). Once developed and launched, both require low effort by teachers, are flexible and assessment-based, and allow for increased opportunity for positive feedback. In addition, following behavioral principles, both can be intensified (e.g., feedback and/or rewards could be provided at more frequent intervals) and/or provided alongside a more intensive package of Tier 3 supports for students who need more individualized and intensive supports than that provided at the Tier 2 level. PBIS teams can integrate either intervention into their already available systems for identifying students who are candidates for Tier 2 interventions. Both provide methods of assessing student improvement (increased points earned for CICO and decrease in instance of challenging behavior or increase in positive behavior for DRC), which a PBIS team can utilize for data-based decision making.

Further, with clear similarities and limited differences, these two interventions have the potential to be combined within a continuum of service. Within tiers, interventions and supports can be intensified. For example, there is an opportunity to begin Tier 2 services with a CICO Daily Progress Report that includes general school behavior expectations as the target behaviors (e.g., be safe, be respectful, be responsible). If the student’s behavior does not improve within an acceptable time period on a particular goal (e.g., be respectful), educators could shift from a general rating (e.g., 0 = Try again, 1 = OK, 2 = Great!) to a more specific goal that limits the number of disruptive behaviors (Respects peers with 5 of fewer instances of teasing) that more closely represents a DRC. This type of intervention modification could occur within Tier 2 level of service, before proceeding to more intensive Tier 3 level services. However, additional research is needed to evaluate the utility of this conceptualization.

Given the similarities across these interventions, the decisions about when to use CICO and/or DRC may be guided by school-, student- and teacher-level factors that can guide decision making. We discuss some guidance related to these decisions below; however, the current siloed nature of the disciplines from which these interventions were derived inhibits our understanding of what conditions may be better suited for each intervention, or for combining them. Thus, we conclude by highlighting future research efforts that may illuminate decision criteria for intervention selection among educators.

School-, Student-, and Teacher-Level Factors

Several considerations can guide educators’ decisions about when to use CICO and/or DRC. First, at the school level, if educators have developed school-wide expectations for appropriate behavior and they consistently apply these expectations (i.e., frequently review, practice, and reinforce them), then they are likely in a good position to build from this foundation and use CICO as a primary Tier 2 intervention. Likewise, if there are sufficient resources to identify a CICO coordinator and multiple personnel are available to serve as CICO mentors, using CICO may allow school personnel to reach many students in need. In contrast, in some schools there is a lack of emphasis on school-wide expectations, application of Tier 1 behavioral support is inconsistent or still in development (Pas & Bradshaw, 2012), and /or there is a lack of resources for a coordinator position. Given that these conditions may compromise the effectiveness of CICO, teachers and students in such settings may be best served via the use of DRCs as the primary Tier 2 intervention.

Second, student characteristics may influence the decision of whether to use CICO or DRC. Namely, given that the DRC was designed for and studied primarily with students demonstrating hyperactive, impulsive and/or inattentive behaviors that affect classroom performance, if these are the primary concerns, then a teachers can have confidence that a DRC is well matched to these student characteristics. However, given that diagnoses are not a primary driver within education (e.g., relative to within mental health fields) and that many problems can manifest as hyperactivity/impulsivity and/or inattention, if the previously described school conditions are present, then a CICO Daily Progress Report is likely to be a reasonable first line Tier 2 intervention. As with any Tier 2 intervention, educators should use progress monitoring data to guide subsequent response-to-intervention and modification decisions, such as further individualization of goals or provision of more frequent and specific behavior feedback as in a DRC. Regarding student age or gender, special versus general education classroom setting, internalizing problems, or opportunities for home–school communication, the literature is currently too limited to inform strong recommendations regarding how such characteristics may affect the effectiveness of either CICO or the DRC for a specific child.

Third, teacher characteristics may guide the decision of whether to use CICO and/or DRC. For example, teachers who exhibit strong classroom management skills and data-based decision making, are confident they can implement a DRC, and appreciate autonomy may be excellent candidates for implementing a DRC (Mixon et al., 2019; Owens et al., 2017; Owens et al., 2020a). In contrast, research has demonstrated that teachers low in knowledge of behavioral principles and who have limited behavior management skills may struggle to adopt and implement the DRC with high effectiveness (Owens et al., 2020a). Teachers possessing such characteristics may be better suited to implement CICO in their classrooms with the support of a CICO coordinator and well-defined school-wide expectations. However, the support of a behavioral consultant, if available, may help such teachers excel in their implementation of a DRC (DeFouw et al., 2024).

Finally, given the rising prevalence of disorders that manifest as disruptive behaviors in the classroom, it may be that some classrooms have high rates of challenging behaviors, even with consistent implementation of best practice Tier 1 strategies. In such cases, CICO may be a preferred intervention over DRC given that several students may have similar behaviors targeted on the CICO (i.e., general class-wide expectations), with more individualization of target behavior for students who do not respond.

In situations with high demand for interventions aimed at reducing disruptive behavior, educators could also consider employing students as peer mentors for CICO (Sanchez et al., 2015); however, there are peer relationship and confidentiality issues that need to be considered. The strengths and weaknesses of the classroom teacher and the number of students in need of Tier 2 interventions need to be considered when selecting an intervention.

In summary, school, child, and teacher characteristics should all be considered when selecting among available interventions. If schools have established school-wide expectations, are implementing them with consistency, and have resources to serve as CICO mentors, then CICO is a valuable option to provide effective Tier 2 support. In addition, within this context, DRCs could also be used for students who need greater specificity related to target behaviors and/or feedback at the point of performance, especially among classrooms whose teacher possesses strong behavior management knowledge and skills at baseline. However, much more research is needed to identify the characteristics of the child, classroom, and school that influence the effectiveness of these interventions and how they can be addressed. Further, we acknowledge that both interventions are flexible and can be modified to include individualized goals and feedback systems, reducing the differences between the two interventions. Although it may be beneficial for schools to be prepared with both interventions to match student needs, it may not be feasible to support the training and personnel required for both interventions. However, for both interventions, there are publicly available resources and materials for training and useFootnote 1 that may help facilitate personnel familiarity and preparedness in either intervention.

Future Research

This commentary sheds light on the additional research that is needed to better facilitate intervention decision making among educators. Although both interventions are widely recommended and widely used, the number of group studies that meet the highest level of rigor (i.e., What Works Clearinghouse Criteria without Reservations) is strikingly limited. We are aware of only one group design study for CICO and two group design studies for DRC. Although each intervention has several rigorous single-case design studies documenting the impact of the intervention, these studies by the nature of small samples, are limited with regard to generalizability and informing what works for whom and under what conditions (i.e., examination of moderating student characteristics or contextual factors). Thus, studies that directly compare the effectiveness of each intervention and include an evaluation of the potential moderating effects (e.g., school climate, child and family cultural background, complexity of the child’s problems, family supports, teacher characteristics) would provide important information that could help practitioners know when and with whom to provide one intervention over the other, or perhaps when to combine the interventions along a continuum of service. If there are no differences in outcome between the two interventions, then decisions about which intervention to use is less of a concern and the choice can be guided by contextual factors, school resources, and teacher preference.

Within such a comparative study, additional questions could be assessed such as: Is one intervention more effective than the other in changing student behavior or academic performance? What is the relative acceptability and feasibly of each intervention? Is one intervention associated with stronger implementation fidelity? The answers to such questions could also inform intervention decisions. Likewise, a SMART design comparing the relative sequencing of the two interventions could also indicate if it is better for educators to start with one intervention first and/or if there is incremental benefit of the other if the first is insufficient. However, deciding what elements are included in a DRC versus CICO would need to be highly specified to highlight their differences.

Another approach that could yield critically important information is to disregard the names of the interventions and focus the analyses on testing the extent to which various components purported to be mechanisms of change predict intervention outcome. Critical components include the strength of the student-mentor or student–teacher relationship, the type of feedback given to the student (i.e., rated on a 3-point scale versus frequency counts of behavior); whether a limit or goal is set on the number of undesirable behaviors the student can exhibit (e.g., respects others with three or fewer mistakes versus respects others), the timing of feedback given to the student (e.g., end of the day or period or at the point of performance), the fidelity or consistency of feedback given, and type of rewards given (e.g., home-based, school-based, none, functionally equivalent). The relative predictive utility of these components could highlight the most important mechanisms of change and the topics and skills to focus on in training and fidelity monitoring.

Future research should also explore strategies for enhancing the cultural sensitivity of these interventions for use with children of diverse cultural backgrounds. On one hand, high specificity and objectivity in the definition of the target behaviors and in the tracking of behavioral frequencies may reduce the impact of teacher bias on perceptions of disruptive student behavior (Kunesh & Noltemeyer, 2019). Yet, there is much to be learned about specific ways teachers could modify the goals and/or feedback to match student characteristics (e.g., language, cultural customs; Sugai et al., 2012).

Finally, it will be prudent to determine the training required for each and how training protocols contribute to the cost-effectiveness of these interventions. Current recommendations reflect greater time resources required for the CICO relative to the DRC, but the lack of comparative studies leaves the questions regarding relative cost-effectiveness of the interventions unanswered. Further, the relative cost-effectiveness of either intervention may be enhanced through additional research and development. There is emerging research documenting both the potential cost-effectiveness of technology-driven supports for some teachers as well as the cost-effectiveness of consultation individualized to teacher needs when there are barriers to implementation (e.g., Owens et al., 2020c; Owens et al., 2019).

Conclusions

This commentary integrates information from two literatures that have historically been siloed, making it difficult for educators and researchers to understand the similarities and differences between CICO and DRC interventions, and offers information to make informed decisions about when to use each intervention. Our synthesis reveals that both interventions have evidence of effectiveness and that both can be used as front-line interventions for Tier 2 or Tier 3 levels of service. In addition, this integration across CICO and DRC literature bases reveals that there are more similarities than differences between the core components and procedures of the interventions, particularly given that both are highly flexible; that is, both can be individualized to specific student needs while maintaining the core mechanisms of change. Thus, if schools are applying school-wide expectations with consistency and have the resources for a CICO coordinator and mentors, then CICO is a viable and recommended option for many students. In the absence of such coordinated resources, educators should consider using a DRC for students with behavioral challenges who need support beyond Tier 1. As an alternative, it may be prudent to combine these interventions along a continuum of service.

We argue that additional research is needed in three areas. The first is a large scale, group design study that directly compare the effectiveness of each intervention and includes an evaluation of the moderating school, child, and teacher-level factors that would help practitioners know when and with whom to provide one intervention over the other. The second is to disregard the names of the interventions and focus the analyses on testing the extent to which various components purported to be mechanisms of change predict intervention outcome. Indeed, given the importance of having systematic school wide procedures for assessing the need for and delivering multitiered supports to students, this latter option has appeal. We argue that we should be less tied to the nuanced differences of the interventions and more focused on the critical practice components that best serve students. The third is to examine the time, training, and costs required to help preservice and in-service professionals to gain competence in those evidence-based practice components. Given that practice needs typically outpace the speed of scientific discoveries, in the meantime, we encourage educators to (1) apply interventions that align with the core similarities across these interventions (i.e., strong relationships, goal setting, principles of operant conditioning), because these components are connected to effectiveness for both interventions; and (2) use data from the interventions to guide decisions related to individualization, response to intervention, and intervention modification.

Notes

For CICO, see https://www.guilford.com for books and videos and many state education websites for PBIS resources. For DRC, see Volpe and Fabiano (2013); www.oucirs.org/daily-report-card-preview, and https://ccf.fiu.edu/about/resources/index.html.

References

Ayllon, T., Garber, S., & Pisor, K. (1975). The elimination of discipline problems through a combined school-home motivational system. Behavior Therapy, 6(5), 616–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80183-3

Barth, R. (1979). Home-based reinforcement of school behavior: A review and analysis. Review of Educational Research, 49(3), 436–458. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543049003436

Blechman, E. A., Taylor, C. J., & Schrader, S. M. (1981). Family problem solving versus home notes as early intervention with high-risk children. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 49(6), 919–926. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.49.6.919

Center on PBIS. (2023). Positive behavioral interventions & supports. https://www.pbis.org/pbis/tier-2

Chafouleas, S. M., Riley-Tillman, T. C., & McDougal, J. L. (2002). Good, bad, or in-between: How does the daily behavior report card rate? Psychology in the Schools, 39(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10027

Conroy, K., Hong, N., Poznanski, B., Hart, K. C., Ginsburg, G. S., Fabiano, G. A., & Comer, J. S. (2022). Harnessing home-school partnerships and school consultation to support youth with anxiety. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice, 29(2), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.02.007

Crone, D. A., Hawken, L. S., & Horner, R. H. (2010). Responding to problem behavior in schools: The behavior education program (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Danielson, M. L., Bitsko, R. H., Holbrook, J. R., Charania, S. N., Claussen, A. H., McKeown, R. E., Cuffe, S. P., Owens, J. S., Evans, S. W., Kubicek, L., & Flory, K. (2020). Community-based prevalence of externalizing and internalizing disorders among school-aged children and adolescents in four geographically dispersed school districts in the United States. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52, 500–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-01027-z

Dart, E. H., Furlow, C. M., Collins, T. A., Brewer, E., Gresham, F. M., & Chenier, K. H. (2015). Peer-mediated check-in/check-out for students at-risk for internalizing disorders. School Psychology Quarterly, 30(2), 229.

DeFouw, E. R., Owens, J. S., Margherio, S. M., & Evans, S. (2024). Supporting Teachers’ Use of Classroom Management Strategies via Different School-Based Consultation Models: Which Is More Cost-Effective for Whom?. School Psychology Review, 53(2), 151–166.

Dougherty, E. H., & Dougherty, A. (1977). The daily report card: A simplified and flexible package for classroom behavior management. Psychology in the Schools, 14(2), 191–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(197704)14:2%3c191::AID-PITS2310140213%3e3.0.CO;2-J

Drevon, D. D., Hixson, M. D., Wyse, R. D., & Rigney, A. M. (2019). A meta-analytic review of the evidence for check-in check-out. Psychology in the Schools, 56(3), 393–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22195

Eklund, K., Kilgus, S. P., Taylor, C., Allen, A., Meyer, L., Izumi, J., ... & Kilpatrick, K. (2019). Efficacy of a combined approach to Tier 2 social-emotional and behavioral intervention and the moderating effects of function. School Mental Health, 11, 678-691.

Fabiano, G. A., Vujnovic, R. K., Pelham, W. E., Waschbusch, D. A., Massetti, G. M., Pariseau, M. E., Naylor, J., Jihnhee, Yu., Yu, J., Robins, M., Carnefix, T., Greiner, A. R., & Volker, M. (2010). Enhancing the effectiveness of special education programming for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder using a daily report card. School Psychology Review, 39(2), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2010.12087775

Farley-Ripple, E., May, H., Karpyn, A., Tilley, K., & McDonough, K. (2018). Rethinking connections between research and practice in education: A conceptual framework. Educational Researcher, 47(4), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X18761042

Filter, K. J., Ford, A. L., Bullard, S. J., Cook, C. R., Sowle, C. A., Johnson, L. D., Kloos, E., & Dupuis, D. (2022). Distilling Check-in/check-out into its core practice elements through an expert consensus process. School Mental Health, 14, 695–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09495-x

Filter, K. J., McKenna, M. K., Benedict, E. A., Horner, R. H., Todd, A., & Watson, J. (2007). Check in/check out: A post-hoc evaluation of an efficient, secondary-level targeted intervention for reducing problem behaviors in schools. Education & Treatment of Children, 30(1), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2007.0000

Girio-Herrera, E., Egan, T. E., Owens, J. S., Evans, S. W., Coles, E. K., Holdaway, A. S., Mixon, C. S., & Kassab, H. D. (2021). Teacher ratings of acceptability of a daily report card intervention prior to and during implementation: Relations to implementation integrity and student outcomes. School Mental Health, 13, 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09400-y

Hawken, L. S., Bundock, K., Barrett, C. A., Eber, L., Breen, K., & Phillips, D. (2015). Large-scale implementation of check-in, check-out: A descriptive study. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 30(4), 304–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573515601005

Hawken, L. S., Bundock, K., Kladis, K., O’Keeffe, B., & Barrett, C. A. (2014). Systematic review of the check-in, check-out intervention for students at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders. Education & Treatment of Children, 37(4), 635–658. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0030

Hawken, L. S., Crone, D. A., Bundock, K., & Horner, R. H. (2020). Responding to problem behavior in schools. Guilford Press.

Hawken, L. S., & Horner, R. H. (2003). Evaluation of a targeted intervention within a schoolwide system of behavior support. Journal of Behavioral Education, 12, 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025512411930

Holdaway, A. S., Hustus, C., Owens, J. S., Evans, S. W., Coles, E. K., Egan, T. E., Himawan, L., Zoromski, A., Dawson, A., & Mixon, C. S. (2020). Incremental benefits of a daily report card over time for youth with disruptive behavior: Replication and extension. School Mental Health, 12, 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-020-09375-w

Horner, R. H., Carr, E., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2005). The use of single subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100203

Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Anderson, C. M. (2010). Examining the evidence base for school wide positive behavior support. Focus on Exceptional Children, 42(8), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.17161/foec.v42i8.6906

Iznardo, M., Rogers, M. A., Volpe, R. J., Labelle, P. R., & Robaey, P. (2017). The effectiveness of daily behavior report cards for children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(12), 1623–1636. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054717734646

Jones, A. M., West, K. B., & Suveg, C. (2019). Anxiety in the school setting: A framework for evidence-based practice. School Mental Health, 11, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-017-9235-2

Jurbergs, N., Palcic, J. L., & Kelley, M. L. (2010). Daily behavior report cards with and without home-based consequences: Improving classroom behavior in low income, African American children with ADHD. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 32(3), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2010.500501

Karhu, A., Närhi, V., & Savolainen, H. (2019). Check in–check out intervention for supporting pupils’ behaviour: Effectiveness and feasibility in Finnish schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(1), 136–146.

Kladis, K., Hawken, L. S., O’Neill, R. E., Fischer, A. J., Fuoco, K. S., O’Keeffe, B. V., & Kiuhara, S. A. (2023). Effects of check-in check-out on engagement of students demonstrating internalizing behaviors in an elementary school setting. Behavioral Disorders, 48(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0198742920972107

Klingbeil, D. A., Dart, E. H., & Schramm, A. L. (2019). A systematic review of function-modified check-in/check-out. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 21(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300718778032

Kunesh, C. E., & Noltemeyer, A. (2019). Understanding disciplinary disproportionality: Stereotypes shape pre-service teachers’ beliefs about black boys’ behavior. Urban Education, 54(4), 471–498.

Lahey, B. B., Gendrich, J. G., Gendrich, S. I., Schnelle, J. F., Gant, D. S., & McNees, M. P. (1977). An evaluation of daily report cards with minimal teacher and parent contacts as an efficient method of classroom intervention. Behavior Modification, 1(3), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/014544557713006

Maggin, D. M., Zurheide, J., Pickett, K. C., & Baillie, S. J. (2015). A systematic evidence review of the check-in/check-out program for reducing student challenging behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(4), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715573630

Majeika, C. E., Van Camp, A. M., Wehby, J. H., Kern, L., Commisso, C. E., & Gaier, K. (2020). An evaluation of adaptations made to check-in check-out. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 22(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300719860131

May, S., Ard, W., III, Todd, A. W., Horner, R. H., Glasgow, A., Sugai, G., & Sprague, J. R. (2003). School-wide information system. Educational and Community Supports, University of Oregon. http://www.swis.org

McIntosh, K., Campbell, A. L., Carter, D. R., & Rossetto Dickey, C. (2009). Differential effects of a tier two behavior intervention based on function of problem behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 11(2), 82–93. ://doi.org./https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300708319127

Miller, L. M., Dufrene, B. A., Olmi, D. J., Tingstrom, D., & Filce, H. (2015). Self-monitoring as a viable fading option in check-in/check-out. Journal of School Psychology, 53(2), 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2014.12.004

Mitchell, B. S., Adamson, R., & McKenna, J. W. (2017). Curbing our enthusiasm: An analysis of the check-in/check-out literature using the Council for Exceptional Children’s evidence-based practice standards. Behavior Modification, 41(3), 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445516675273

Mixon, C. S., Owens, J. S., Hustus, C., Serrano, V. J., & Holdaway, A. S. (2019). Evaluating the impact of online professional development on teachers’ use of a targeted behavioral classroom intervention. School Mental Health, 11(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9284-1

Neef, N. A., Perrin, C. J., & Madden, G. J. (2013). Understanding and treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In G. J. Madden, W. V. Dube, T. D. Hackenberg, G. P. Hanley, & K. A. Lattal (Eds.), APA handbook of behavior analysis, Vol. 2. Translating principles into practice (pp. 387–404). American Psychological Association.

Owens, J. S., Coles, E. K., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Girio-Herrera, E., Holdaway, A. S., ... & Schulte, A. C. (2017). Using multi-component consultation to increase the integrity with which teachers implement behavioral classroom interventions: A pilot study. School Mental Health, 9, 218–234.

Owens, J. S., Evans, S. W., Coles, E. K., Himawan, L. K., Holdaway, A. S., Mixon, C., & Egan, T. (2020a). Consultation for classroom management and targeted interventions: Examining benchmarks for teacher practices that produce desired change in student behavior. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 28(1), 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426618795440

Owens, J. S., Holdaway, A. S., Zoromski, A. K., Evans, S. W., Himawan, L. K., Girio-Herrera, E., & Murphy, C. E. (2012). Incremental benefits of a daily report card intervention over time for youth with disruptive behavior. Behavior Therapy, 43(4), 848–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2012.02.002

Owens, J. S., Hustus, C. L., & Evans, S. W. (2020b). The daily report card intervention: Summary of the science and factors affecting implementation. In T. Farmer, M. Conroy, B. Farmer, & K. Sutherland (Eds.), Handbook of research on emotional & behavioral disabilities: Interdisciplinary developmental perspectives on children and youth (pp. 371–385). Routledge.

Owens, J. S., Margherio, S. M., Lee, M., Evans, S. W., Crowley, D. M., Coles, E. K., & Mixon, C. S. (2020c). Cost-effectiveness of consultation for a daily report card intervention: Comparing in-person and online implementation strategies. Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation, 31, 382–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2020.1759428

Owens, J. S., McLennan, J. D., Hustus, C. L., Haines-Saah, R., Mitchell, S., Mixon, C. S., & Troutman, A. (2019). Leveraging technology to facilitate teachers’ use of a targeted classroom intervention: Evaluation of the Daily Report Card. Online (DRC.O) System. School Mental Health, 11, 665–677.

Park, E. Y., & Blair, K. S. C. (2020). Check-in/check-out implementation in schools: A meta-analysis of group design studies. Education & Treatment of Children, 43, 361–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-020-00030-2

Pas, E. T., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2012). Examining the association between implementation and outcomes: State-wide scale-up of school-wide Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 39, 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-012-9290-2

Pyle, K., & Fabiano, G. A. (2017). Daily report card intervention and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of single-case studies. Exceptional Children, 83(4), 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402917706370

Riden, B. S., Taylor, J. C., Lee, D. L., & Scheeler, M. C. (2018). A synthesis of the daily behavior report card literature from 2007 to 2017. Journal of Special Education Apprenticeship, 7(1). https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/josea/vol7/iss1/3/

Rosen, L. A., O’Leary, S. G., Joyce, S. A., Conway, G., & Pfiffner, L. J. (1984). The importance of prudent negative consequences for maintaining the appropriate behavior of hyperactive children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 12, 581–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00916852

Sagvolden, T., Aase, H., Zeiner, P., & Berger, D. (1998). Altered reinforcement mechanisms in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Behavioural Brain Research, 94(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4328(97)00170-8

Sanchez, S., Miltenberger, R. G., Kincaid, D., & Blair, K. S. C. (2015). Evaluating check-in check-out with peer tutors for children with attention maintained problem behaviors. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 37(4), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2015.1104769

Schaper, A. (2023). Check-in/check-out (CICO): Intervention tips and guidance. Panorama Education. https://www.panoramaed.com/blog/check-in-check-out-cico-intervention

Simonsen, B., Myers, D., Briere, D. E., & III. (2011). Comparing a behavioral check-in/check-out (CICO) intervention to standard practice in an urban middle school setting using an experimental group design. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300709359026

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., Scott, T., Liaupsin, C., Sailor, W., Turnbull, A. P., Turnbull, H. R., Wickham, D., Wilcox, B., & Ruef, M. (2000). Applying positive behavioral support and functional behavioral assessment in schools. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions & Support, 2(3), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070000200302

Sugai, G., O’Keeffe, B. V., & Fallon, L. M. (2012). A contextual consideration of culture and school-wide positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14(4), 197–208.

Vannest, K. J., Davis, J. L., Davis, C. R., Mason, B. A., & Burke, M. D. (2010). Effective intervention for behavior with a daily behavior report card: A meta-analysis. School Psychology Review, 39, 654–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2010.12087748

Volpe, R. J., & Fabiano, G. A. (2013). Daily behavior report cards: An evidence-based system of assessment and intervention. Guilford Press.

Vujnovic, R., K., Holdaway, A. S., Owens, J. S., & Fabiano, G. A. (2014). Response to Intervention for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Incorporating an evidence-based intervention within a multi-tiered framework. In M. S. Weist, N. A. Lever, C. P. Bradshaw, & J. S. Owens (Eds.), Handbook of school mental health: Research, training, practice, and policy (2nd ed.; pp. 399–412). Springer.

Warberg, A., George, N., Brown, D., Churan, K., & Taylor-Greene, S. (1995). Behavior education plan handbook. Fern Ridge (Eugene, OR) Middle School.

Waschbusch, D. A., Bernstein, M. D., Robb Mazzant, J., Willoughby, M. T., Haas, S. M., Coles, E. K., & Pelham, W. E., Jr. (2016). A case study examining fixed versus randomized criteria for treating a child with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Evidence-Based Practice in Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 1(2–3), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2016.1227946

Weist, M. D., Eber, L., Horner, R., Splett, J., Putnam, R., Barrett, S., Perales, K., Fairchild, A. J., & Hoover, S. (2018). Improving multitiered systems of support for students with “internalizing” emotional/behavioral problems. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20(3), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300717753832

Williams, K. L., Noell, G. H., Jones, B. A., & Gansle, K. A. (2012). Modifying students’ classroom behaviors using an electronic daily behavior report card. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 34(4), 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2012.732844

Wolfe, K., Pyle, D., Charlton, C. T., Sabey, C. V., Lund, E. M., & Ross, S. W. (2016). A systematic review of the empirical support for check-in check-out. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18, 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715595957

Funding

While writing the commentary, the first author was funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grants R350A210224, R305A200423, R324A190154 to Ohio University. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the U.S. Department of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The first author and her team are developers of the www.dailyreportcardonline.com. None of the authors receive financial benefit from this site.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Human subjects were not involved in this research, thus informed consent procedures were not needed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Owens, J.S., Margherio, S., Dillon, C. et al. The Daily Report Card and Check-in/Check-out: A Commentary About Two Siloed Interventions. Educ. Treat. Child. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-024-00126-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43494-024-00126-z