Abstract

Evidence-based interventions have the potential to improve health and well-being, but their effectiveness depends, among other things, on the challenging act of balancing between fidelity and adaptation, referred to as the fidelity-adaptation dilemma. After initial implementation, it is primarily professionals delivering evidence-based interventions to end users that face the dilemma, but research about how professionals relate to and perceive it is limited. This study aims to describe professionals’ attitudes towards the dilemma and investigate the associations between professional attitudes and individual and organisational implementation determinants, individual characteristics, and work-life consequences for the professionals. Using a cross-sectional design, 103 professionals working with an evidence-based parental support programme ABC (All Children in Focus) were surveyed on attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma, implementation determinants, and work-life consequences. Data were analysed using two-step cluster analysis. Three profile groups summarize professionals’ attitudes: one preferring fidelity (the adherers, n = 31), one preferring adaptations (the adapters, n = 50), and one with a dual view on fidelity and adaptation (the double-minded, n = 18). The adherers, the ones preferring fidelity, reported higher levels of skills, knowledge, openness, work-related self-efficacy, meaning of work, and possibilities for development, and a lower level of role conflict and unreasonable tasks compared to the adapters. Professionals with a positive attitude towards fidelity reports experiencing more job resources and a lower level of job demands compared to professionals who are more positive towards adaptation. The study shows that the fidelity-adaptation dilemma is at play during the sustainment phase of implementation and suggest that it has consequences for professionals working life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Evidence-based interventions (EBI) have the potential to improve individuals’ health and well-being, but their impact depends on how they are used. One vital aspect of how EBIs are used concerns the extent to which delivery of an EBI must adhere to its original plan and to what degree adaptations based on restraints and possibilities in the context are acceptable or desirable. This challenge is commonly referred to as the fidelity-adaptation dilemma (Castro et al., 2010; Chambers et al., 2013; Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Moore et al., 2013; Stirman et al., 2013).

High-fidelity delivery of EBIs is related to better outcomes compared to low-fidelity delivery (Elliot & Mihalic, 2004) and adaptations can increase the risk of making the EBI ineffective or unsafe (Aschbrenner et al., 2021; Chambers et al., 2013; Kumpfer et al., 2018). However, high-fidelity delivery of EBIs within many fields, such as health care, social work and school settings is uncommon (Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2012) while studies show that adaptations is common within these field, for example health care (Kakeeto et al., 2017), public health (Escoffery et al., 2018) and social work (Strehlenert et al., 2023). These adaptations are commonly motivated by differences between the context the EBI was designed for and the context in which the EBI is being used, and the adaptations are often done in order to improve the acceptability, feasibility, and/or appropriateness of the intervention (Arora et al., 2021; Chambers et al., 2013; Glasgow et al., 2012; Lange et al., 2022; Kroll-Desrosiers et al., 2023; Strehlenert et al., 2023). Thus, adaptations of EBIs can sometimes be preferable and even make an EBI more effective than non-adapted EBIs (Barrera et al. Jr, 2013; Sundell et al., 2016; Olsson et al., 2023). This underlines the vital role that the fidelity-adaptation dilemma plays in the implementation of EBIs.

To a large extent, research has addressed the fidelity-adaptation dilemma early in the implementation process (Aarons et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2008), whereas less attention has been paid to the dilemma when the EBIs are fully implemented in organizations, the sustainment phase of implementation. However, since context continuously changes over time (Chambers et al., 2013), the need for adaptations is likely to resurface also when programs have been institutionalized and considered in the sustainment phase of implementation, pointing to a need of understanding and doing research on the dilemma in this phase. At this time point, researchers and implementation experts are unlikely to still be engaged, and thus, the ones facing the fidelity-adaptation dilemma are the professionals using the EBIs. A qualitative study confirmed that professionals indeed perceived management of fidelity and adaptation as a dilemma – a difficult situation – in the sustainment phase and that it was both affected by and had consequences for their perception of their work (Zetterlund et al., 2022). Thus, even though the professionals reported having different predispositions regarding the dilemma, they regardless struggled and met difficulties when trying to follow their beliefs, which also made them act in a certain way (Zetterlund et al., 2022). Yet despite frequent calls for increased focus on the sustainment phase of implementation (Durlak & DuPre, 2008; Glasgow & Chambers, 2012) and particularly on the professionals’ views, attitudes, and practices in relation to EBIs (Scurlock-Evans & Upton, 2015), such studies are lacking.

Previous studies have shown that professionals’ predisposition towards EBIs, that is their attitudes (Dawson, 2006) have implications for how professionals work with EBIs, e.g., EBI adoption (Beidas et al., 2015; Aarons, 2004) and fidelity levels (Francke et al., 2008; Fuller et al., 2007). In addition to individual characteristics such as field of work (Beidas et al., 2013; Stahmer & Aarons, 2009) and education and experience level (Smith, 2013), attitudes towards EBIs are affected by factors related to the individual as well as the organization. Individual factors include, for example, skills (Beidas et al., 2015), knowledge about the EBI (Aarons, 2004; Francke et al., 2008), openness to EBIs (Beidas et al., 2013, 2015; Francke et al., 2008), divergence between EBIs and own experience (Stahmer & Aarons, 2009), and work-related self-efficacy (Francke et al., 2008). Organizational factors include implementation climate (Beidas et al., 2013), organizational support (Beidas et al., 2013; Fuller et al., 2007), and social support from colleagues (Fuller et al., 2007). Furthermore, there is a relationship between professionals’ attitudes about EBIs and their experiences of working with EBIs, where experiences can be the meaning of work, role conflict, unreasonable tasks (Francke et al., 2008), possibilities for development (Fuller et al., 2007), and quantitative demands (Beidas et al., 2013; Fuller et al., 2007).

However, these studies focus on the early implementation phase and attitudes to EBIs in general. The relationship between professionals’ attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma and individual characteristics, implementation determinants, and work-life consequences remains to be investigated.

Consequently, this study aims to describe the fidelity-adaptation dilemma from the professional’s perspective with the following research questions:

-

a.

What attitudes do professionals have towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma?

-

b.

How do the attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma relate to individual characteristics, implementation determinants (individual and organisational), and consequences of working with an EBI?

Methods

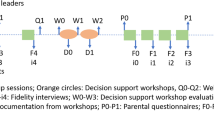

This study uses baseline survey data from a larger project (von Thiele Schwarz et al., 2021) involving group leaders of an evidence-based parental programme (All Children in Focus, the ABC program) (Lindberg et al., 2013). Thus, it has a cross-sectional design where a person-oriented method (cluster analysis) is used to describe the professionals’ attitudes toward the fidelity-adaptation dilemma and to investigate the association of attitude profiles with individual characteristics, implementation determinants, and work-life consequences for the professionals. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies was used to guide the reporting of this study.

Case-Setting

Data was collected from group leaders who were trained to deliver the ABC program in Sweden. ABC focuses on teaching parents strategies to handle challenging situations in their parenthood with the goal of improving the parent-child relationship. It is widely offered in community services in Sweden and has been shown to be efficacious in improving children’s and parents’ health (Ulfsdotter et al., 2014) and cost-effective (Ulfsdotter et al., 2015). ABC is designed to include up to 14 parents of children aged 3–12 years in one group and consists of five group sessions (four sessions + one booster) that are manual-based and 2.5 h long. The sessions present four different themes (showing love, being there, showing the way, and picking your battles + one out of three optional booster themes) and consist of lectures, group discussions, roleplay, movies, parent manuals, and homework. They are led by two group leaders (for further details, see Lindberg et al. (2013). ABC is often delivered in school settings and in the field of social work, by teachers, preschool teachers, sociologists, curators, etc. No specific criteria are needed to be admitted to ABC training and thereby become an ABC group leader, but having a post-high school education, working with children and/or parents, and being able to deliver ABC to parents while under training is advantageous.

Participants and Recruitment

Eligible participants were professionals who had participated in the ABC group leader training (ABC training) and used ABC in their daily work in organisations where the program was continuously offered, i.e. the program was used in the sustainment phase of implementation. The recruitment was primarily conducted through the intermediary organization that has been responsible for ABC training since 2010. Information about the study was included in the emails that are routinely sent to the ABC training alumni (n = 418). The first author also provided verbal information about the study to new cohorts of group leaders during their ABC training (n = 38). How many of the 456 ABC alumni who actively worked with ABC and were eligible to participate in the study (the actual target group) is unknown. The recruitment phase started in May 2020, paused due to the coronavirus pandemic for about seven months, and lasted until spring 2022.

In total, 134 people responded that they wanted to participate in the study and were provided access to the survey, which 103 people answered. Four people were excluded due to missing data essential for this study. The mean age of the included participants was 50.4 years (SD 9.2), and 89% were women. The professionals mostly worked in the area of pedagogics (55.7%) or social work (39.4%), the mean number of working years within their occupation was 20 years (SD 17) and the mean number of years since they had become an ABC group leader was four years (SD 6). All participants had delivered ABC to parents at least once and all were expected to continue to deliver the program without further implementation support. There are no available data on the non-responders.

The planning and reporting of this study are in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, as revised in 2013. The project has received ethical approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref no. 2019–06276). All potential participants were given written information about the study and what participation entailed, how data was safeguarded, and how the participants could later access the results. It was also emphasized that participation was voluntary, and that participation could be withdrawn at any time without giving a reason. If a participant wanted to participate in the study, she or he was either given a web-based link to the survey (applied for the professionals recruited online) or a paper survey (those recruited in person). Before filling out the survey all participants were asked to sign an informed consent. This was done electronically by checking a box (those recruited through the email list) or in writing (those recruited in person). Reminders were sent out after one, seven, and 12 months, after that the participants who had not replied were considered non-responders.

Measurements

Data was collected through a survey designed to capture the participants’ attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma (specifically developed for this study), individual characteristics, individual and organisational implementation determinants to work with an ABC, and consequences of working with ABC. Previously validated questionnaires from the implementation field (Aarons, 2004; Hujig et al., 2014; Jacobs et al., 2014; Roaldsen & Halvarsson, 2019; Santesson et al., 2020) and work-life science (Anskär et al., 2019; Berthelsen et al., 2020; Jacobshagen, 2006; Rigotti et al., 2008; Semmer et al., 2010) were used (See Table 1).

Fidelity-Adaptation Attitudes

To measure the professionals’ attitudes toward the fidelity-adaptation dilemma five statements were developed that aimed to reflect the duality of the dilemma: that (a) high fidelity is related to better outcomes compared to low fidelity (Barrera et al. Jr, 2013; Sundell et al., 2016), but at the same time that (b) adapted EBIs may be more effective than non-adapted EBIs (Elliott & Mihalic, 2004), and finally (c) regardless the predisposition about fidelity and adaptation, you may feel obligated or forced to act in a certain way (Zetterlund et al., 2022). Each item was designed to measure attitudes toward the dilemma specifically in relation to ABC. The five items were: 1: High fidelity to ABC leads to more effective actions 2. Adaptations of ABC lead to more effective actions, 3. It is important to use ABC with high fidelity, 4. It is always possible to use ABC with high fidelity, and 5. It happens that ABC needs to be adapted. Response options were on a five-point scale from 1 (disagree) to 5 (totally agree).

Implementation Determinants and Work-Life Consequences

In line with the recommendations in the literature (Hujig et al., 2014), items from the used questionnaires were reformulated to refer specifically to ABC (except EBPAS, (Aarons, 2004). The response scales of the original scales were retained with a five-point response scale with endpoints such as “not at all”, “never”, “to a low degree” to “totally agree”, “always” or “to a very high degree” (except Work-Related Self-Efficacy (OSS-6) (Rigotti et al., 2008), which used a seven- point scale).

The internal consistency of the items was calculated with Cronbach’s alpha (Table 1). Since the value of α is affected by the number of items in the specific scale (Cortina, 1993) and the scales used in this study have few items, a Cronbach’s alpha of.61 was deemed acceptable, although it is lower than the commonly used 0.70 (Kline, 1999). The internal construct validity of the questionnaires with more than one domain was tested with Confirmatory factor analysis, showing good validity.

Data Analysis

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS version 28.0.1.0. The Laavan- and Tidyverse packages in R, version 4.1.3 were used for the Confirmatory factor analysis and illustration.

Cluster Analysis

A cluster analysis was performed to identify homogenous profiles among respondents using the five items for attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptations dilemma. A two-step cluster analysis (TSCA) (Bacher et al., 2004) was used where the data first was pre-clustered into dense regions within the analysed attribute space and later merged into clusters. The TSCA determines the optimal number of clusters based on a measure of fit (i.e. the Bayesian Information Criterion). The Silhouette score was used to identify the goodness of the clustering (range between − 1 and 1), where a higher number indicates that the subgroups were located closer to their cluster centre (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 1990). A Kruskal Wallis test was conducted to confirm that items differed significantly between the clusters.

Differences in individual characteristics, individual and organisational implementation determinants to work with an ABC, and consequences of working with ABC were investigated using the Kruskal Wallis test or Chi2-test (Pearson or two-tailed Fisher Exact test). Exact p-values are presented, and due to the large number of comparisons, the significance level was set to 1% to minimize type 1 errors; hence, a p-value lower than 0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Cluster Analysis

The TSCA resulted in three clusters (silhouette coefficient value 0.55) (Fig. 1). The first cluster labelled “adapters” comprised 50 (50.5%) participants who, on average, had a predisposition for making adaptations and who felt most strongly that fidelity does not guarantee effective actions. The second cluster, the “double-minded”, represented 18 participants (18.2%) who had strong beliefs that both fidelity and adaptation lead to effective actions but also that it is not always possible to retain high fidelity. The third cluster labelled the “adherers” contained 31 (31.3%) participants who, on average, had a preconception that fidelity was preferable. This cluster groupdid also not report believing, to a high degree, that adaptations helped to obtain effective actions of ABC. The Kruskal Wallis tests confirmed that the five items differed significantly between clusters (p < .001 for each item) (Table 2). Notably, the found attitude profiles were not the total opposite of each other; instead, the main difference between the profiles was in whether the professionals were absolutely sure about their standpoint or not.

Cluster Comparisons

There was no statistically significant difference between the clusters regarding organisational determinants and individual characteristics. Instead, statistically significant differences were found between the clusters in individual determinants and the consequences of working with ABC (Table 2). The difference was found mostly between the adapters and the adherers (see Table 3 for pairwise comparisons) where the adapters reported lower Skills (H(15.98) = 2, p = < 0.001)), Knowledge (H(19.91) = 2, p = < 0.001), Openness H(23.12) = 2, p = < 0.001) and Work-related self-efficacy (H(24.71) = 2, p = < 0.001) compared to the adherers. Furthermore, the adapters also perceived lower Meaning of work (H(24.51) = 2, p = < 0.001) compared to both the adherers and the double-minded as well as lower Possibilities for development (H(26.60) = 2, p = < 0.001), Role conflict (H(16.22) = 2, p = < 0.001), and more Unreasonable tasks (H(18.91) = 2, p = < 0.001) compared to the adherers. In sum, adapters reported less favourable individual determinants, and more negative consequences when working with ABC, primarily compared to the adherers.

Discussion

The results from this study indicate that professionals’ attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma can be summarised in three profiles: one that prefers fidelity, one that prefers adaptations, and one with a dual and somewhat contradictory view on fidelity and adaptation. The results also show that there is a difference in individual determinants and consequences of working with ABC between the three profile groups. Professionals who report a predisposition for fidelity reported perceiving a higher level of skills, knowledge, openness, work-related self-efficacy, meaning of work, and possibilities for development, and a lower level of role conflict and fewer unreasonable tasks compared to the professionals who reported a predisposition for adaptation.

The differences between the groups occurred even though the study sample was homogenous in that all worked with the same EBI in Sweden and had received the same training in the EBI. Moreover, individual characteristics or organizational determinants did not differ between the groups. This result is noteworthy because these are factors that have been shown to have an impact on fidelity in previous studies (Francke et al., 2008) and have been identified as facilitators of implementation (Aarons, 2004; Aarons et al., 2011; Beidas et al., 2015; Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011). The results are however in line with previous research highlighting the importance of individual determinants for implementation outcomes (Aarons, 2004; Beidas et al., 2013, 2015; Francke et al., 2008; Stahmer & Aarons, 2009), extending these findings by showing that individual determinants are also related to attitudes towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma among professionals in the sustainment phase.

The professionals are clustered into three distinct profiles (adapters, double-minded, and adherers), which had different standpoints in the matter of fidelity and adaptations. Indeed, the profiles differ in whether high fidelity or adaptations are believed to lead to better results and whether it is important and always possible to use ABC with high fidelity or if it happens that ABC needs to be adapted. This information can be used when tailoring implementation strategies for professionals with different key characteristics, sometimes referred to as audience segmentation (Leeman et al., 2017). However, the results do not indicate that the profiles are the total opposite of each other; instead, the results indicate that the main difference between the profiles is in whether the professionals are absolutely sure about their standpoint or not. Thus, the adapters were not all for adaptation; instead, they did not have as strong beliefs about fidelity as the adherers did and the adherers were not totally against adaptation, they only had stronger opinions against it compared to the adapters.

Overall, the professionals found it satisfying to work with ABC as indicated by the overall high outcome rates of each measured variable (Table 2). However, in line with the job demand and resource model (Demerouti et al., 2001), the findings suggest that working with an EBI can serve both as a resource and a demand for professionals. The adapters experience more job demands and fewer resources compared to the adherers. Thus, for the adapters, working with the EBI is related to role conflicts and unreasonable tasks, and they report fewer resources to meet those demands, such as fewer skills, less knowledge, openness, etc. Such a combination of high demands and low resources in working life has been consistently linked to adverse health and performance outcomes (Lesener et al., 2019). Thus, it reflects a less favourable working condition.

There are at least two ways to interpret the relationship between the professionals’ attitude towards the fidelity-adaptation dilemma and their working conditions from a job demand/resources perspective. On the one hand, having high resources when using an EBI may reflect a situation where the professionals have sufficient resources to use the EBI with high fidelity, thereby mitigating the dilemma. Thus, the adherers may not have been exposed to situations where the demands of working with the EBI exceeded their resources, prompting them to consider adaptations. On the other hand, perceiving that working with EBI is associated with high job demands (e.g., role conflict) may indicate that the EBI does not fit fully with the professional’s other commitments and tasks. In this scenario, the experience of high job demands/low resources may prompt more accepting attitudes and/or less strict statements about the possibilities to retain high fidelity, as in the adaptation cluster profile. Thus, the attitude may have followed from the experience of working with the EBI rather than the opposite, that having a more forgiving attitude to adaptations leads to less favourable working conditions. Yet this remains speculative at this point, as the cross-sectional and explorative design of this study does not allow the direction of the relationship to be disentangled. Previous research indicates that the direction can be both ways, with professionals’ characteristics affecting attitudes towards EBIs (Stahmer & Aarons, 2009) as well as the other way around (Aarons, 2004; Smith, 2013). We propose that future studies should analyse the potential causal effect.

Methodological Discussion

The cross-sectional design does not make causal inferences concerning the attitudes and the other studied variables possible. The study is based on self-ratings, which is suitable for studying attitudes. It is however beyond the scope of the study to investigate to what extent the professionals also differ in how they practically manage fidelity and adaptation, e.g., if they differ in the number and type of adaptations, but also how the results associate with different implementation-, service-., and client outcomes of ABC. Thus, these questions are yet to be investigated.

There can be a risk of selection bias as the professionals who choose to participate in the study may have been those particularly interested in fidelity and/or adaptation. There is no data available on the non-responders, and it is unknown how many of the ABC alumni were eligible to participate in the study, thus we only know the response rate of all alumni and not for the specific target group (alumni that currently worked with ABC). The diversity in participants’ characteristics and views on fidelity and adaptation indicates there was sufficient variation in the sample. Also, although the sample size is within the recommended range for cluster analysis and the silhouette value indicates a clear separation between clusters, which supports that power was sufficient to detect meaningful clusters (Dalmaijer et al., 2022), it may not be possible to detect clusters that are rare in the population. However, such profiles would nevertheless be of limited practical importance.

As we found no validated measure for professionals’ attitudes towards the dilemma, items were developed specifically for this study, based on research regarding the dilemma (Barrera Jr et al., 2013; Elliot & Mihalic, 2004; Sundell et al., 2016; Zetterlund et l., 2022). Yet only already existing questionnaires were used to measure the professionals’ work-life situation, which have all undergone validity testing with satisfactory results. To safeguard the internal consistency reliability and the internal construct validity after the modifications were made, Cronbach’s alpha tests and Confirmatory factor analysis were performed with satisfactory results.

Conclusions

During the sustainment phase, three types of attitudes towards fidelity and adaptations among professionals can be distinguished: one leaning towards fidelity, one leaning towards adaptations, and one with a dual and somewhat contradictory view on fidelity and adaptation. There are differences between profiles in terms of individual determinants and work-life consequences. Professionals who report a predisposition for adapting EBIs are more prone to report experiencing an imbalance between job demands and job resources. This information offers a work-life perspective on some of the challenges that professionals face when using an EBI and points to a need for further exploration of the fidelity-adaptation dilemma during the sustainment phase of implementation when the dilemma risks landing at the feet of professionals.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

All Children in Focus (Swedish: Alla Barn i Centrum)

- BITS:

-

Bern Illegitimate Tasks Scale

- COPSOQ II:

-

The Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II

- DIBQ:

-

Determinants of Implementation Behaviour Questionnaire

- EBI:

-

Evidence-Based Intervention

- EBPAS:

-

Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale

- ICM:

-

Implementation Climate Measure

- OSS-6:

-

Short version of the Occupational Self-Efficacy Scale

- TSCA:

-

Two-Step Custer Analysis

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental Health Provider attitudes toward Adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65.

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(1), 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7.

Aarons, G. A., Green, A., Palinkas, L., Self-Brown, S., Whitaker, D., Lutzker, J., Silovsky, J., Hecht, D., & Chaffin, M. (2012). Dynamic adaptation process to implement evidence-based child maltreatment intervention. Implementation Science, 7, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-32.

Anskär, E., Lindberg, M., Falk, M., & Andersson, A. (2019). Legitimacy of work tasks, psychosocial work environment, and time utilization among primary care staff in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 37(4), 476–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813432.2019.1684014.

Arora, P. G., Parr, K. M., Khoo, O., Lim, K., Coriano, V., & Baker, C. N. (2021). Cultural adaptations to Youth Mental Health Interventions: A systematic review. J Child Fam Stud, 30, 2539–2562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02058-3.

Aschbrenner, K. A., Mueller, N. M., Banerjee, S., & Bartels, S. J. (2021). Applying an equity lens to characterizing the process and reasons for an adaptation to an evidenced-based practice. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 26334895211017252. https://doi.org/10.1177/26334895211017252.

Bacher, J., Wenzig, K., & Vogler, M. (2004). SPSS TwoStep Cluster – a first evaluation. Work and discussion paper. Erlangen-Nuremberg.

BarreraJr, M., Castro, F. G., Strycker, L. A., & Toobert, D. J. (2013). Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Vol, 81, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027085. American Psychological Association.

Beidas, R., Edmunds, J., Ditty, M., Watkins, J., Walsh, L., Marcus, S., & Kendall, P. (2013). Are inner context factors related to implementation outcomes in cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety? Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0529-x.

Beidas, R. S., Marcus, S., Aarons, G. A., Hoagwood, K. E., Schoenwald, S., Evans, A. C., Hurford, M. O., Hadley, T., Barg, F. K., Walsh, L. M., Adams, D. R., & Mandell, D. S. (2015). Predictors of community therapists’ Use of Therapy techniques in a large public Mental Health System. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(4), 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3736.

Berthelsen, H., Westerlund, H., Bergström, G., & Burr, H. (2020). Validation of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire Version III and establishment of Benchmarks for Psychosocial Risk Management in Sweden. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093179.

Castro, F. G., Barrera Jr, M., & Holleran Steiker, L. K. (2010). Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 213–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032.

Chambers, D., Glasgow, R., & Stange, K. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8, 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-117.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98.

DalmaijerES, NordCL., & AstleDE. (2022). Statistical power for cluster analysis. Bmc Bioinformatics, 23(205). http://doi.org10.1186/s12859-022-04675-1.

Damschroder, L. J., & Hagedorn, H. J. (2011). A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 194–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022284.

Dawson, K. P. (2006). Attitude and assessment in nurse education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17, 473–479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01932.x.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Elliott, D. S., & Mihalic, S. (2004). Issues in disseminating and replicating effective Prevention Programs. Prevention Science, 5(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PREV.0000013981.28071.52.

Escoffery, C., Lebow-Skelley, E., Haardoerfer, R., Boing, E., Udelson, H., Harmna, W. R. M., Perdnandez. M. E., & Mullen, P. D. (2018). A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implementation Sci, 13, 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0815-9.

Francke, A. L., Smit, M. C., de Veer, A. J. E., & Mistiaen, P. (2008). Factors influencing the implementation of clinical guidelines for health care professionals: A systematic meta-review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 8(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-8-38.

Fuller, B., Rieckmann, T., Nunes, E., Miller, M., Arfken, C., Edmundson, E., & Mccarty, D. (2007). Organizational readiness for change and opinions toward treatment innovations. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 33, 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.026.

Glasgow, R. E., & Chambers, D. (2012). Developing robust, sustainable, implementation systems using rigorous, rapid and relevant science. Clinical and Translational Science, 5(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00383.x.

Glasgow, R. E., Vinson, C., Chambers, D., Khoury, M. J., Kaplan, R. M., & Hunter, C. (2012). National Institutes of Health Approaches to dissemination and implementation science: Current and future directions. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1274–1281. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300755.

Huijg, J. M., Gebhardt, W. A., Dusseldorp, E., Verheijden, M. W., van der Zouwe, N., Middelkoop, B. J. C., & Crone, M. R. (2014). Measuring determinants of implementation behavior: Psychometric properties of a questionnaire based on the theoretical domains framework. Implementation Science, 9(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-33.

Jacobs, S. R., Weiner, B. J., & Bunger, A. C. (2014). Context matters: Measuring implementation climate among individuals and groups. Implementation Science, 9(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-9-46.

Jacobshagen, N. (2006). Illegitimate tasks, illegitimate stressors: Testing a new stressor-strain concept. Selbst.

Kakeeto, M., Lundmark, R., Hasson, H., & von Schwarz, T., U (2017). Meeting patient needs trumps adherence. A cross-sectional study of adherence and adaptations when national guidelines are used in practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 23(4), 830–838.

Kaufman, L., & Rousseeuw, P. (1990). Finding groups in data: An introduction to cluster analysis. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532178.

Kline, P. (1999). The handbook of psychological testing (2.ed.). Routledge.

Kroll-Desrosiers, A., Finley, E. P., Hamilton, A. B., & Cabassa, L. J. (2023). Evidence-based Intervention Adaptations within the Veterans Health Administration: A scoping review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 38, 2383–2395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08218-z.

Kumpfer, K. L., Scheier, L. M., & Brown, J. (2018). Strategies to avoid replication failure with evidence-based Prevention interventions: Case examples from the strengthening families Program. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 43(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278718772886.

Lange, B. C. L., Nelson, A., Lang, J. M., & Striman, W., S (2022). Adaptations of evidence-based trauma-focused interventions for children and adolescents: A systematic review. Implement Sci Commun, 3, 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-022-00348-5.

Lee, S., Altschul, I., & Mowbray, C. (2008). Using Planned Adaptation to implement evidence-based programs with new populations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9160-5.

Leeman, J., Birken, S., Powell, B. J., Rohweder, C., & Shea, C. M. (2017). Beyond implementation strategies: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and pracie. Implementation Science, 12, 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x.

Lesener, T., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 33(1), 76–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1529065.

Lindberg, L., Ulfsdotter, M., Jalling, C., Skärstrand, E., Lalouni, M., Lönn Rhodin, K., Månsdotter, A., & Enebrink, P. (2013). The effects and costs of the universal parent group program – all children in focus: A study protocol for a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Bmc Public Health, 13(1), 688. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-688.

Moore, J. E., Bumbarger, B. K., & Cooper, B. R. (2013). Examining adaptations of evidence-based programs in natural contexts. Journal of Primary Prevention, 34(3), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0303-6.

Olsson, T. M., von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., Vira, E. G., & Sundell, K. (2023). Adapted, Adopted, and Novel Interventions: A Whole-Population Meta-Analytic Replication of Intervention Effects. Research on social work practice. http://doi.org/10497315231218646.

Rigotti, T., Schyns, B., & Mohr, G. (2008). A short version of the Occupational Self-Efficacy Scale: Structural and Construct Validity Across Five Countries. Journal of Career Assessment, 16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072707305763.

Roaldsen, K. S., & Halvarsson, A. (2019). Reliability of the Swedish version of the evidence-based practice attitude scale assessing physiotherapist’s attitudes to implementation of evidence-based practice. Plos One, 14(11), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225467.

Santesson, A., Bäckström, M., Holmberg, R., Perrin, S., & Jarbin, H. (2020). Confirmatory factor analysis of the evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS) in a large and representative Swedish sample: Is the use of the total scale and subscale scores justified? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01126-4.

Scurlock-Evans, L., & Upton, D. (2015). The role and nature of evidence: A systematic review of Social workers’ evidence-based practice orientation, attitudes, and implementation. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 12(4), 369–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.853014.

Semmer, N. K., Tschan, F., Meier, L. L., Facchin, S., & Jacobshagen, N. (2010). Illegitimate tasks and counterproductive work behavior. Applied Psychology, 59(1), 70–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00416.x.

Smith, B. D. (2013). Substance use treatment counselors’ attitudes toward evidence-based practice: The importance of Organizational Context. Substance Use & Misuse, 48(5), 379–390. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2013.765480.

Stahmer, A., & Aarons, G. (2009). Attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practices: A comparison of Autism early intervention providers and children’s Mental Health providers. Psychological Services, 6, 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0010738.

Stirman, S. W., Miller, C. J., Toder, K., & Calloway, A. (2013). Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 8(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-65.

Strehlenert, H., Hedberg Rundgren, E., Sjunnestrand, M., & Hasson, H. (2023). Fidelity to and adaptation of evidence-based interventions in the Social Work Literature: A scoping review. The British Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad170.

Sundell, K., Beelmann, A., Hasson, H., & von Schwarz, T., U (2016). Novel Programs, International adoptions, or contextual adaptations? Meta-Analytical results from German and Swedish Intervention Research. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(6), 784–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1020540.

Ulfsdotter, M., Enebrink, P., & Lindberg, L. (2014). Effectivenss of a universal health-promoting parenting program: A ranomized wailitst-controlled trial of all children in Focus. Bmc Public Health, 14(1), 1083. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1083.

Ulfsdotter, M., Lindberg, L., & Månsdotter, A. (2015). A cost-effectivness analysis of the Swedish Universal Parenting Program All Children in Focus. PLoS One, 10(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/jounral.prone.0145201.

von Schwarz, T., Giannotta, U., Neher, F., Zetterlund, M., J., & Hasson, H. (2021). Professionals’ management of the fidelity–adaptation dilemma in the use of evidence-based interventions—an intervention study. Implementation Science Communications, 2(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00131-y.

Wiltsey Stirman, S., Kimberly, J., Cook, N., Calloway, A., Castro, F., & Charns, M. (2012). The sustainability of new programs and innovations: A review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-17.

Zetterlund, J., Von Thiele Schwarz, U., Hasson, H., & Neher, M. (2022). A Slippery Slope when using an evidence-based intervention out of Context. How professionals Perceive and navigate the Fidelity-Adaptation Dilemma—A qualitative study. Frontiers in Health Services, 2, 883072. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2022.883072.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to City of Stockholm and PLUS parenting support for their collaboration and welcoming approach when letting us get involved in ABC, but also for their invaluable help when recruiting participants. Furthermore, we give warm thanks to Emma Hedberg Rundgren for her invaluable assistance during the start up of the data collection. Last, but not least, we thank all the participants in this research, without whom there would be no study.

Funding

This study has received research grant funding from the Swedish Research Council (Ref No 2016-01261) after a competitive peer-review process. The council is Sweden’s largest governmental research funder. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, including the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data or the writing of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Swedish Research Council. Open Access funding was provided by Mälardalen University.

Open access funding provided by Mälardalen University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JZ, HH, MN, and UvTS designed the study. UvTS secured funding for the study and was responsible for the ethical application supported by JZ and MN. JZ recruited the participants, collected the data, and conducted statistical analyses. The results were discussed among all authors. JZ drafted the first version of the study. All authors discussed the draft, revised it, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Ref No. 2019-06276). The planning and reporting of this study are in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, as revised in 2013.

Consent to Participate

All participants in the study gave their informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Standards of Reporting

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cross-sectional studies was used to guide the reporting of this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zetterlund, J., Hasson, H., Neher, M. et al. Professionals’ Fidelity-Adaptation Attitudes: Relation to Implementation Determinants and Work-Life Consequences – A Cluster Analysis. Glob Implement Res Appl 4, 167–178 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43477-024-00120-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43477-024-00120-y