Abstract

The sizeable body of evidence indicating that parenting programs have a positive impact on children and families highlights the potential public health benefits of their implementation on a large scale. Despite evidence and global attention, beyond the highly controlled delivery of parenting programs via randomized trials, little is known about program effectiveness or how to explain the poorer results commonly observed when implemented in community settings. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers must work together to identify what is needed to spur adoption and sustainment of evidence-based parenting programs in real-world service systems and how to enhance program effectiveness when delivered via these systems. Collecting, analyzing, and using facilitator fidelity data is an important frontier through which researchers and practitioners can contribute. In this commentary, we outline the value of assessing facilitator fidelity and utilizing the data generated from these assessments; describe gaps in research, knowledge, and practice; and recommend directions for research and practice. In making recommendations, we describe a collaborative process to develop a preliminary guideline—the Fidelity of Implementation in Parenting Programs Guideline or FIPP—to use when reporting on facilitator fidelity. Readers are invited to complete an online survey to provide comments and feedback on the first draft of the guideline.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parenting programs empower parents/caregivers (“parents”) to acquire the knowledge and/or skills to support them to improve the health and well-being of their children (Barlow & Coren, 2018). There are hundreds of randomized trials and numerous meta-analyses indicating that parenting programs are effective in improving child and family outcomes, including reducing child behavior problems and violence against children and improving positive parenting and child mental health (Barlow & Coren, 2018; Barlow et al., 2006; Chen & Chan, 2016; Furlong, 2013). For instance, a meta-analysis of 37 trials of parenting programs aiming to reduce child maltreatment had an effect size of 0.30 (Chen & Chan, 2016) and a meta-analysis of 45 trials of parenting programs aiming to treat child disruptive behaviors had an effect size of 0.69 (Leijten et al., 2019). Several ‘reviews of reviews’ have drawn similar conclusions (Barlow & Coren, 2018; Coore Desai et al., 2017; Mikton & Butchart, 2009; Sandler et al., 2011, 2015). Finally, there is meta-analytic evidence to suggest that parenting programs are effective when transported to new delivery systems and cultural contexts (Gardner et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2020).

The sizeable body of evidence indicating that parenting programs have a positive impact on children and families highlights the importance of their implementation on a large scale. Several influential organizations recommend that parenting programs be delivered at scale to empower parents in enhancing child development, strengthening families, and promoting the safety and well-being of children (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2014; National Academies of Sciences, 2022; World Health Organization, 2022). For instance, the World Health Organization recommends parenting programs as one of seven strategies for reducing violence against children (WHO, 2016). If implemented broadly, parenting programs could be a key means through which to attain several of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (e.g., Goals 3 and 16) and actualize the Convention on the Rights of the Child (e.g., Articles 5 and 19) (Eisner et al., 2016).

Science to Service

Despite the evidence and global attention, there is a gap between what is known about the effectiveness of parenting programs when delivered via randomized trials and the extent to which they are delivered in practice via community settings. This “science to service gap” (Fixsen et al., 2009) is commonly acknowledged in the literature, particularly at scale (Gottfredson et al., 2015) and in low- and middle-income contexts where violence against children is prevalent (Hillis et al., 2016; Knerr et al., 2013; Shenderovich, 2021; Stoltenborgh et al., 2013). Among the few studies that examine scale-up, there has been mixed evidence of program effectiveness (e.g., Gray et al., 2018; Marryat et al., 2017; Shapiro et al., 2010). Evidence on scaling from similar interventions, such as on early childhood development programs, suggest effects at scale may be smaller including due to lower quality of delivery and problems with staff retention (Araujo et al., 2021)—a phenomenon described as the “scale-up penalty” (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2014). In the parenting program literature, an evaluation of the Triple P program in Scotland found that the intervention did not impact child mental health when delivered at the population level (Marryat et al., 2017), whereas a study of the Incredible Years and Triple P programs in England found that the interventions had a similarly positive impact on child behavior, parenting behavior, and parental mental health when delivered in both research and community settings (Gray et al., 2018). Another example of successful delivery at scale is the Parent Management Training-Oregon Model program, which has demonstrated the ability to be transported to new cultural contexts (Ogden & Hagen, 2008) and delivered at scale in Norway with implementation fidelity supports and monitoring (Askeland et al., 2019). Overall, beyond the highly controlled delivery of parenting programs via randomized trials, little is known about program effectiveness or how to explain the poorer results commonly observed when implemented in community settings. Although we currently do not know how to account for these gaps, parenting programs have tremendous potential to be a positive force for children and families. As a result, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers must work together to identify what is needed to spur adoption and sustainment of parenting programs in real-world service systems and how to enhance program effectiveness when delivered via these systems (Smith et al., 2020).

Bridging the Gap

One of several avenues to bridge the gap in our knowledge is the use of implementation fidelity monitoring (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2011). Implementation fidelity refers to the extent to which an intervention is implemented as intended (Bumbarger & Perkins, 2008; Dane & Schneider, 1998; Dusenbury et al., 2003). There are four commonly acknowledged components of implementation fidelity—adherence, quality of delivery (or competence), dosage, and participant responsiveness (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Dusenbury et al., 2003; Mihalic, 2004; Proctor et al., 2011). Herein, we focus on two aspects of implementation fidelity directly related to the delivery of parenting programs by facilitators (i.e., delivery agents, purveyors, therapists, group leaders)—adherence (the strictness with which a facilitator implements program components as intended) and competence (the skill and style with which a facilitator delivers program components) (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Dusenbury et al., 2003; Fixsen et al., 2005). As Berkel et al. (2019) highlight, competence and adherence, also referred to as ‘competent adherence’, ‘facilitator fidelity’, and ‘facilitator delivery’ (Breitenstein et al., 2010a, 2010b; Forgatch et al., 2005), tend to suffer when programs are delivered via routine service delivery due in part to a lack of a formal implementation support mechanisms.

Facilitator Fidelity

The competent adherence with which facilitators implement parenting programs is a particularly important aspect of implementation fidelity to examine as facilitators are the vehicle through which participants receive an intervention (Petersilia, 1990). Many studies indicate that higher quality delivery of parenting programs by facilitators is associated with improved parent and child outcomes (e.g., Chiapa et al., 2015; Eames et al., 2008; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2011; Forgatch et al., 2005; Martin et al., 2023; Scott et al., 2008) and is associated with critical process variables for prevention programs, such as motivation and engagement (Berkel et al., 2021; Smith et al., 2013). Despite a large body of evidence on parenting programs, relatively little is known about the quality with which facilitators implement parenting programs in practice and when delivered at scale (Smith et al., 2019). This gap in knowledge is in part due to few studies on the subject and the lack of consistency of reporting among studies that examine facilitator delivery (Martin et al., 2021, 2023). Closing the facilitator fidelity knowledge gap would go a long way toward generating understanding and concerning the differences in effectiveness found between parenting programs delivered in randomized trials and parenting programs delivered in real-world settings, particularly at scale.

To support the argument that parenting program research and practice should devote greater attention to assessing facilitator fidelity, we outline the value of assessing facilitator fidelity and using the data generated from these assessments; describe gaps in research, knowledge, and practice related to assessing facilitator fidelity; and recommend directions for research and practice. In making these recommendations, we describe a collaborative process to develop a preliminary guideline for parenting program researchers—the Fidelity of Implementation in Parenting Programs Guideline—to use when reporting on facilitator fidelity. As part of this process, readers are invited to complete an online survey to provide comments and feedback on the first draft of the guideline.

Assessing and Reporting Facilitator Fidelity

The systematic assessment and comprehensive reporting of facilitator fidelity would be of substantial value to the parenting program field by contributing to knowledge in five key areas related to research on both the efficacy of such programs and their implementation in practice. Data on facilitator fidelity provides critical information about:

-

1.

the extent to which program theory is implemented in practice (Breitenstein et al., 2010a, 2010b). Even though a program may have a strong theoretical foundation or is efficacious in randomized trials, it does not necessarily mean that it will be delivered as planned in practice or that it will be used as expected by the intended stakeholders (Petersilia, 1990). Thus, fidelity data support a determination of the magnitude of Type III error (Carroll et al., 2007; Dobson & Cook, 1980).

-

2.

the potential mechanisms through which an intervention affects its outcomes (Astbury & Leeuw, 2010; Berkel et al., 2019; Fixsen et al., 2005; Scriven, 1999). Uncovering such mechanisms may illuminate what program components are and are not contributing to the achievement of the outcomes found so that participant outcomes can be maximized by delivering essential components and shedding unessential components (Van Ryzin et al., 2016).

-

3.

how interventions and implementation can be improved (Breitenstein et al., 2010a, 2010b). For instance, fidelity data can help establish what components facilitators struggle to deliver, which can inform ongoing and future training and coaching processes.

-

4.

whether implementation fidelity is associated with participant outcomes. Higher program implementation quality—such as participant attendance, participant engagement in sessions, and delivery by facilitators—is theorized and commonly found to be associated with enhanced participant outcomes in the broader behavioral intervention literature (Carroll et al., 2007; Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Similar findings have emerged in the parenting program literature (Leitão et al., 2020; Martin et al., 2023).

-

5.

what types of supervision models and related implementation supports are needed to dependably deliver a high-quality intervention in various contexts during intervention dissemination and scale-up (Glasgow et al., 2003). This is especially the case as intervention effectiveness is often weakened at scale due to poor implementation or drift, which can occur once interventions become widely used (Bond et al., 2000; Botvin, 2004). ‘Drift’ is distinct from ‘adaptation’; the latter occurs when planned or unplanned changes are made to a program or its delivery to suit the context (Campbell et al., 2020). While adaptations are often conceptualized as detracting from an intervention, there is a growing recognition that varying degrees of adaptation may be necessary to maintain functional fidelity, such as in a new context (Moore et al., 2021).

The value that facilitator fidelity provides points toward collecting this data via facilitator assessments as a next frontier through which researchers and practitioners can advance parenting intervention science. However, there are several gaps and challenges associated with assessing facilitator fidelity in both research and practice that should be considered and addressed.

Gaps and Challenges

Related to research, there are gaps in knowledge as well as in reporting. First, there is scant literature on the reliability and validity of facilitator fidelity measures—as is evidenced by few studies examining the psychometric properties of measures used to assess facilitator fidelity (Martin et al., 2021). Although a lack of psychometric evidence may only seem like a concern to researchers, it is also problematic for practitioners as they too use assessment results to inform decision-making and the allocation of often scarce resources for training and supervision. Without reliable and valid measures, decisions using fidelity data cannot be made with a great deal of confidence. In sum, reliable and valid measures are essential to their use (Ruud et al., 2020).

Second, rigorous measures designed and used in the context of efficacy trials are often impractical for use in community settings and at scale. For facilitator fidelity assessments to be used in practice, considerable trade-offs are necessary to balance research rigor and real-world practicality. Although observational measures are considered most rigorous, these methods pose significant practical challenges especially at scale (Eames et al., 2008). In addition to being time and resource intensive, observational assessments may be impacted by reactivity bias (Girard & Cohn, 2016). Although non-observational methods do not use as many human resources (i.e., time and money), they may miss important aspects of delivery (e.g., body language, participation reactions, participant engagement) and their reliability may be limited by social desirability (Stone et al., 1999). The tension between rigor and practicality appears most apparent as programs transition from delivery via efficacy and effectiveness trials to implementation via routine service delivery and at scale.

Third, few studies report on facilitator fidelity in detail. In research papers, details on the reporting of how assessments are conducted is particularly lacking, such as information about the characteristics of the facilitators delivering programs; the educational background and measure-specific training for those who conduct facilitator assessments (assessors or coders); and the amount of time and money necessary to complete fidelity assessments (Martin et al., 2021). These details regarding assessments are most relevant beyond efficacy trials in the context of real-world implementation when resource limitations are even more poignant. Further, describing the real-world logistics (e.g., audio/video recording, observation) of conducting fidelity assessments is important as compiling a body of literature may allow for the advancement of knowledge on how to make fidelity assessments easier and less costly, particularly at scale (Lewis et al., 2021). Similarly, few studies examine or report on the association between facilitator fidelity and outcomes (Martin et al., 2021, 2023). Among the studies that do report on facilitator fidelity in general, the reporting of key information about facilitator fidelity is inconsistent. For instance, many studies do not provide details regarding facilitator sample sizes and average level of delivery fidelity achieved (Martin et al., 2021)—information necessary for meta-analyzing the literature, assessing the strength of study findings, and determining the extent to which programs are delivered in practice. Additionally, without evidence that facilitator fidelity predicts program outcomes, the value proposition of investing resources in the measurement and use of fidelity data is undetermined.

As it relates to practice, while insufficient attention is paid to facilitator delivery in research, there is even less focus on fidelity monitoring once interventions are implemented in community settings. This is understandable as fidelity monitoring is typically an extremely time and resource intensive process with current methods (Anis et al., 2021). Fidelity monitoring is complicated as it involves many steps, including developing an appropriate measure, testing the measure, training individuals to use the measure (assessors), having assessors use the measure in practice, providing ongoing supervision to facilitators being assessed using the measure, tabulating assessment data, and then using the assessment data collected to inform program improvements (e.g., Sanders et al., 2020). These steps not only take time and energy but are costly thereby requiring substantial budgets. A particular challenge with facilitator assessments is that measures are often quite detailed and lengthy. However, little is known regarding how best to develop and implement fidelity assessments. For instance, there is insufficient understanding of how measures should capture the tension between fidelity and adaptation, which is important as both planned and unplanned adaptations are typically made in practice and at scale (Axford et al., 2017; Kemp, 2016; Lize et al., 2014).

Thus, there are many challenges and gaps in research and practice related to assessing facilitator fidelity that need to be addressed. Although some of the challenges in assessing facilitator fidelity overlap between controlled evaluations and implementation in practice, some aspects are unique to specific stages of the research to practice pipeline.

Recommendation for Future Research and Practice

We recommend several approaches to advance future research and practice in parenting program implementation overall and at three points on the research translation pipeline.

Overall

For parenting programs at a community level, we recommend creating a ‘fidelity culture’ among researchers, implementing organizations, assessors, and facilitators. Such a culture appears essential as fidelity monitoring requires substantial organizational commitment (Axford et al., 2017). Various actions could be taken to support a fidelity culture including designing measures with practicality in mind (Lewis et al., 2021). Relatedly, facilitating such a supportive environment is important as there is understandably some resistance and anxiety among many implementing staff regarding being evaluated. This resistance and anxiety stems from the potentially critical and punitive nature of assessments rather than a lack of agreement on the value of assessments. As a result, implementing staff conducting evaluations and being evaluated need to be assured and feel that the process is supportive and collaborative.

Pre-intervention

Before parenting programs are delivered, we recommend

-

(1)

Documenting the program theory of change (logic model) and highlighting the core components and mechanisms of the program that should be followed to retain fidelity (Moore et al., 2021).

-

(2)

Designing fidelity measures and assessment processes that will provide valuable information to various stakeholders, not just researchers. To do so, measures might be designed by engaging stakeholders in a content validity exercise (e.g., Martin et al., 2022).

-

(3)

Establishing procedures to collect fidelity assessment data as well as relevant information associated with the fidelity assessment process (e.g., documenting time required per assessor and per trainer to complete assessor training).

-

(4)

Preparing to collect data that can be used to establish the reliability and validity of the measure designed or chosen to assess facilitator fidelity (e.g., determining intra- and inter-rater reliability during assessor training).

-

(5)

Reporting how facilitator fidelity assessment data will be collected and sharing such information via study protocols.

Efficacy and Effectiveness Trials

When parenting programs are tested via efficacy and effectiveness trials, we recommend

-

(1)

Reporting the results of fidelity assessments to advance the literature on the extent and quality with which parenting programs are delivered under ideal circumstances.

-

(2)

Conducting and reporting on analyses of measure reliability and validity (Stirman, 2020). Gathering and synthesizing psychometric evidence is critical to ensuring measures and assessments using these measures are of good quality so that subsequent critical decision-making about both future trials and program delivery in practice is based on solid data.

-

(3)

Conducting and reporting on analyses of the relationship between facilitator fidelity and program outcomes. A better understanding of this relationship could lend insight into the mechanisms through which parenting programs work, which can then inform decision-making about how to best dedicate scarce resources to maximize participant outcomes.

-

(4)

Investigating what constitutes a sufficient facilitator delivery monitoring process to inform how fidelity assessments can be made easier to conduct in practice. Further recommendations to this end include:

-

i.

testing different assessment procedures to determine whether simplified methodologies are sufficient (e.g., Suhrheinrich et al. (2020) compared a three- or five-point Likert scale in an attempt to create a measure that was both useable and rigorous);

-

ii.

establishing whether simpler data collection processes—particularly self-report tools—are reliable (e.g., Tiwari et al. (2021) compared audio assessments with video assessments and found 72% agreement; Breitenstein et al., (2010a, 2010b) compared in-person observations with self-reports and found 85% agreement);

-

iii.

examining whether assessments conducted at one timepoint are representative of overall delivery (e.g., Caron et al. (2018) examined the impact of facilitators’ average delivery across cases, as well as case-specific delivery; Shenderovich et al. (2019) examined how facilitator delivery fluctuated over 14 sessions);

-

iv.

studying how facilitator delivery varies over time, particularly drift over longer periods of time and over many years, such as has been examined in the Parent Management Training-Oregon Model (Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2011) and Family Check-Up® programs (Chiapa et al., 2015) and

-

v.

exploring and evaluating novel methods of assessing facilitator delivery, such as qualitative or automated methods (e.g., Berkel, Smith, et al. [under review] explore the potential of a machine learning approach based on natural language processing to capture facilitator fidelity).

-

i.

-

(5)

In collaboration with relevant stakeholders, establishing processes for translating information on fidelity assessments into practice by delineating the explicit feedback loops through which knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of facilitator delivery can improve practice via program manuals, facilitator training, and ongoing supervision (Fixsen et al., 2005).

Dissemination and Implementation in Real-World Delivery Systems

When parenting programs are disseminated and scaled within real-world delivery systems, we recommend:

-

(1)

Implementing the knowledge gained on fidelity monitoring from efficacy and effectiveness trials (e.g., using the results of fidelity assessments to modify facilitator training materials).

-

(2)

Establishing tools and processes to monitor facilitator fidelity and then using the processes and procedures to monitor facilitator fidelity throughout delivery.

-

(3)

Evaluating whether fidelity continues to be associated with program outcomes in community settings.

-

(4)

Investigating whether fidelity assessment tools and processes are practical to implement, such as using the Psychometric and Pragmatic Evidence Rating Scale (PAPERS), which specifies criteria to evaluate implementation measures (Lewis et al., 2021). Information about measure practicality may also be captured via qualitative methods to ascertain facilitator and assessor experiences of fidelity assessments.

-

(5)

Collaborating with stakeholders to analyze the facilitator fidelity data collection procedure and then apply the findings to inform future evaluations and modifications to fidelity monitoring processes.

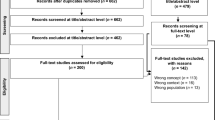

Reporting Guidelines: The FIPP Guideline

The implementation of many of the above recommendations would be supported by rigorous reporting of fidelity monitoring at all stages in the research translation pipeline. As a result, the authors are in the process of creating a reporting guideline on facilitator fidelity assessment and reporting practices, the FIPP guideline, for use by researchers and practitioners studying and implementing parenting programs aiming to strengthen parenting practices and reduce child behavior problems and violence against children. We draw on the recommendations published by Moher et al. (2010) on the development of reporting guidelines. In sum, a multi-part online Delphi exercise is being employed. First, relevant literature has been reviewed to develop a preliminary draft of the FIPP (see Table 1). The draft reflects the types of information that were articulated as important in a range of articles published in the parenting and broader behavioral intervention literature (Bellg et al., 2004; Breitenstein et al., 2010a, 2010b; Breitenstein et al., 2010a, 2010b; Martin et al., 2021, 2023). The guideline was also created based on the expertise and experience of the co-authors, who are involved in fidelity assessment in the research and practice of parenting programs around the world, including Parenting for Lifelong Health, the Chicago Parent Program, Family Check-Up®/Family Check-Up® 4 Health, Parenting for Respectability, and Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up. Based on the literature and the experience of the authors, the draft guideline includes six sections recommending that those reporting on facilitator fidelity provide details on intervention characteristics, facilitator characteristics, assessor characteristics, measure characteristics, fidelity results, and potential biases. Second, the draft guideline will be shared with parenting experts and practitioners to gather their input via an online survey, including via the publication of this article. The authors invite readers to provide input on the draft guideline by completing an anonymous online survey. Third, the draft guideline included in this commentary will be revised based on the results of the online survey. Fourth, a consensus meeting will be held with invited researchers and practitioners to discuss, edit, and vote on each item included in the guideline. Fifth, a reporting guideline will be created and published for researchers and practitioners in the parenting field to consider, use, and further revise. As the guideline does not include items on program adaptations, it is envisaged that the guideline developed herein could be used in conjunction with frameworks and reporting guidelines specific to adaptations (e.g., FRAME-IS) (Miller et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Evidence indicates that parenting programs have great potential to improve the health and well-being of children and families around the world. However, further implementation research is needed regarding how parenting programs might be effectively delivered as part of routine service delivery and at scale. Monitoring, analyzing, and reporting facilitator fidelity data will be a key driver of the parenting program community’s continuing and further success to ensure the efficient use of resources to achieve maximal public health benefit from parenting programs. This commentary describes the advantages of assessing and using data on facilitator delivery, outlines gaps in current knowledge, recommends future avenues for research and practice with parenting program fidelity, and sets out the process being used to create the FIPP—a reporting guideline for the parenting program community to use to ensure consistency in reporting facilitator assessment data.

Readers are encouraged to contribute to the FIPP reporting guideline by offering their feedback here: https://osu.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_29Nftj6wkrnVbwi (see Supplementary File 2 for QR code).

References

Anis, L., Benzies, K. M., Ewashen, C., Hart, M. J., & Letourneau, N. (2021). Fidelity assessment checklist development for community nursing research in early childhood. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 582950–582950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.582950

Araujo, M. C., Rubio-Codina, M., & Schady, N. (2021). 70 to 700 to 70,000: Lessons from the Jamaica experiment. The scale-up effect in early childhood and public policy (pp. 211–232). Routledge.

Askeland, E., Forgatch, M. S., Apeland, A., Reer, M., & Grønlie, A. A. (2019). Scaling up an empirically supported intervention with long-term outcomes: The Nationwide Implementation of GenerationPMTO in Norway. Prevention Science, 20(8), 1189–1199.

Astbury, B., & Leeuw, F. L. (2010). Unpacking black boxes: Mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(3), 363–381.

Axford, N., Bywater, T., Blower, S., Berry, V., Baker, V., & Morpeth, L. (2017). Implementation of evidence-based parenting programmes. The Wiley handbook of what works in child maltreatment: An evidence-based approach to assessment and intervention in child protection (pp. 349–366).

Barlow, J., & Coren, E. (2018). The effectiveness of parenting programs: A review of Campbell reviews. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(1), 99–102.

Barlow, J., Johnston, I., Kendrick, D., Polnay, L., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2006). Individual and group-based parenting programmes for the treatment of physical child abuse and neglect. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005463.pub2

Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., Ogedegbe, G., Orwig, D., Ernst, D., & Czajkowski, S. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443

Berkel, C., Gallo, C. G., Sandler, I. N., Mauricio, A. M., Smith, J. D., & Brown, C. H. (2019). Redesigning implementation measurement for monitoring and quality improvement in community delivery settings. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 40(1), 111–127.

Berkel, C., Mauricio, A. M., Rudo-Stern, J., Dishion, T. J., & Smith, J. D. (2021). Motivational interviewing and caregiver engagement in the Family Check-Up 4 Health. Prevention Science, 22(6), 737–746.

Bond, G. R., Evans, L., Salyers, M. P., Williams, J., & Kim, H.-W. (2000). Measurement of fidelity in psychiatric rehabilitation. Mental Health Services Research, 2(2), 75–87.

Botvin, G. J. (2004). Advancing prevention science and practice: Challenges, critical issues, and future directions. Prevention Science, 5(1), 69–72.

Breitenstein, S. M., Fogg, L., Garvey, C., Hill, C., Resnick, B., & Gross, D. (2010a). Measuring implementation fidelity in a community-based parenting intervention. Nursing Research, 59(3), 158.

Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Garvey, C. A., Hill, C., Fogg, L., & Resnick, B. (2010b). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(2), 164–173.

Bumbarger, B., & Perkins, D. F. (2008). After randomised trials: Issues related to dissemination of evidence-based interventions. Journal of Children’s Services, 3(2), 55–64.

Campbell, M., Moore, G., Evans, R. E., Khodyakov, D., & Craig, P. (2020). ADAPT study: Adaptation of evidence-informed complex population health interventions for implementation and/or re-evaluation in new contexts: Protocol for a Delphi consensus exercise to develop guidance. British Medical Journal Open, 10(7), e038965.

Caron, E., Bernard, K., & Dozier, M. (2018). In vivo feedback predicts parent behavior change in the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up intervention. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S35–S46.

Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2(1), 40.

Chen, M., & Chan, K. (2016). Effects of parenting programs on child maltreatment prevention: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(1), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014566

Chiapa, A., Smith, J. D., Kim, H., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D. S., & Wilson, M. N. (2015). The trajectory of fidelity in a multiyear trial of the family check-up predicts change in child problem behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 1006.

Coore Desai, C., Reece, J.-A., & Shakespeare-Pellington, S. (2017). The prevention of violence in childhood through parenting programmes: A global review. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(sup1), 166–186.

Dane, A. V., & Schneider, B. H. (1998). Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review, 18(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(97)00043-3

Dobson, D., & Cook, T. J. (1980). Avoiding type III error in program evaluation: Results from a field experiment. Evaluation and Program Planning, 3(4), 269–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(80)90042-7

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350.

Dusenbury, L., Brannigan, R., Falco, M., & Hansen, W. B. (2003). A review of research on fidelity of implementation: Implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Education Research, 18(2), 237–256.

Eames, C., Daley, D., Hutchings, J., Hughes, J., Jones, K., Martin, P., & Bywater, T. (2008). The leader observ: ation tool: A process skills treatment fidelity measure for the Incredible Years parenting programme. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34(3), 391–400.

Eisner, M., Nivette, A., Murray, A. L., & Krisch, M. (2016). Achieving population-level violence declines: Implications of the international crime drop for prevention programming. Journal of Public Health Policy, 37(1), 66–80.

Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Naoom, S. F., & Wallace, F. (2009). Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(5), 531–540.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., Wallace, F., Burns, B., Carter, W., Paulson, R., Schoenwald, S., & Barwick, M. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature.

Forgatch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2011). Sustaining fidelity following the nationwide PMTO™ implementation in Norway. Prevention Science, 12(3), 235–246.

Forgatch, M. S., Patterson, G. R., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2005). Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training. Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 3–13.

Furlong, M. (2013). Implementing the Incredible Years Parenting Programme in disadvantaged settings in Ireland: A process evaluation National University of Ireland Maynooth].

Gardner, F., Montgomery, P., & Knerr, W. (2016). Transporting evidence-based parenting programs for child problem behavior (age 3–10) between countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(6), 749–762.

Girard, J. M., & Cohn, J. F. (2016). A primer on observational measurement. Assessment, 23(4), 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116635807

Glasgow, R. E., Lichtenstein, E., & Marcus, A. C. (2003). Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1261–1267.

Gottfredson, D. C., Cook, T. D., Gardner, F. E., Gorman-Smith, D., Howe, G. W., Sandler, I. N., & Zafft, K. M. (2015). Standards of evidence for efficacy, effectiveness, and scale-up research in prevention science: Next generation. Prevention Science, 16(7), 893–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0555-x

Gray, G. R., Totsika, V., & Lindsay, G. (2018). Sustained effectiveness of evidence-based parenting programs after the research trial ends. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2035–2035. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02035

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079.

Institute of Medicine & National Research Council. (2014). Strategies for scaling effective family-focused preventive interventions to promote children's cognitive, affective, and behavioral health: Workshop summary.

Kemp, L. (2016). Adaptation and fidelity: A recipe analogy for achieving both in population scale implementation. Prevention Science, 17(4), 429–438.

Knerr, W., Gardner, F., & Cluver, L. (2013). Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 14(4), 352–363.

Leijten, P., Gardner, F., Melendez-Torres, G., Van Aar, J., Hutchings, J., Schulz, S., Knerr, W., & Overbeek, G. (2019). Meta-analyses: Key parenting program components for disruptive child behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(2), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.07.900

Leitão, S. M., Seabra‐Santos, M. J., & Gaspar, M. F. (2020). Therapist Factors Matter: A Systematic Review of Parent Interventions Directed at Children’s Behavior Problems. Family Process.

Lewis, C. C., Mettert, K. D., Stanick, C. F., Halko, H. M., Nolen, E. A., Powell, B. J., & Weiner, B. J. (2021). The psychometric and pragmatic evidence rating scale (PAPERS) for measure development and evaluation. Implementation Research and Practice, 2, 26334895211037390.

Lize, S. E., Andrews, A. B., Whitaker, P., Shapiro, C., & Nelson, N. (2014). Exploring adaptation and fidelity in parenting program implementation: Implications for practice with families. Journal of Family Strengths, 14(1), 8.

Marryat, L., Thompson, L., & Wilson, P. (2017). No evidence of whole population mental health impact of the Triple P parenting programme: Findings from a routine dataset. BMC Pediatrics, 17(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0800-5

Martin, M., Lachman, J. M., Murphy, H., Gardner, F., & Foran, H. (2022). The development, reliability, and validity of the Facilitator Assessment Tool: An implementation fidelity measure used in Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children. Child: Care, Health and Development. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.13075

Martin, M., Steele, B., Lachman, J. M., & Gardner, F. (2021). Measures of facilitator competent adherence used in parenting programs and their psychometric properties: a systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1–20.

Martin, M., Steele, B., Spreckelsen, T. F., Lachman, J. M., Gardner, F., & Shenderovich, Y. (2023). The association between facilitator competent adherence and outcomes in parenting programs: A systematic review and SWiM analysis. Prevention Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-023-01515-3

Mihalic, S. (2004). The importance of implementation fidelity. Emotional and Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 4(4), 83–105.

Mikton, C., & Butchart, A. (2009). Child maltreatment prevention: A systematic review of reviews. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87, 353–361.

Miller, C. J., Barnett, M. L., Baumann, A. A., Gutner, C. A., & Wiltsey-Stirman, S. (2021). The FRAME-IS: a framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Implementation Science, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01105-3

Moher, D., Schulz, K. F., Simera, I., & Altman, D. G. (2010). Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Medicine, 7(2), e1000217.

Moore, G., Campbell, M., Copeland, L., Craig, P., Movsisyan, A., Hoddinott, P., Littlecott, H., O’Cathain, A., Pfadenhauer, L., & Rehfuess, E. (2021). Adapting interventions to new contexts—THE ADAPT guidance. BMJ, 374, 1679.

National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine. (2022). Family-focused interventions to prevent substance use disorders in adolescence: Proceedings of a workshop. https://doi.org/10.17226/26662.

Ogden, T., & Hagen, K. A. (2008). Treatment effectiveness of Parent Management Training in Norway: A randomized controlled trial of children with conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 607.

Petersilia, J. (1990). Conditions that permit intensive supervision programs to survive. Crime & Delinquency, 36(1), 126–145.

Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

Ruud, T., Drake, R., & Bond, G. R. (2020). Measuring fidelity to evidence-based practices: Psychometrics. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(6), 871–873.

Sanders, M. R., Spry, C. S., Tellegen, C. L., Kirby, J. N., Metzler, C. M., & Prinz, R. J. (2020). Development and validation of fidelity monitoring and enhancement in an evidence-based parenting program. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 47, 569–580.

Sandler, I., Ingram, A., Wolchik, S., Tein, J. Y., & Winslow, E. (2015). Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 9(3), 164–171.

Sandler, I. N., Schoenfelder, E. N., Wolchik, S. A., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 299–329.

Scott, S., Carby, A., & Rendu, A. (2008). Impact of therapists’ skill on effectiveness of parenting groups for child antisocial behavior. Institute of Psychiatry, Kings College.

Scriven, M. (1999). The fine line between evaluation and explanation. Research on Social Work Practice, 9(4), 521–524.

Shapiro, C. J., Prinz, R. J., & Sanders, M. R. (2010). Population-based provider engagement in delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions: Challenges and solutions. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(4), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0210-z

Shenderovich, Y., Eisner, M., Cluver, L., Doubt, J., Berezin, M., Majokweni, S., & Murray, A. L. (2019). Delivering a parenting program in South Africa: The impact of implementation on outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(4), 1005–1017.

Shenderovich, Y., Lachman, J. M., Ward, C. L., Wessels, I., Gardner, F., Tomlinson, M., Oliver, D., Janowski, R., Martin, M., Okop, K., Sacolo-Gwebu, H., Ngcobo, L. L., Fang, Z., Alampay, L., Baban, A., Baumann, A. A., Benevides de Barros, R., Bojo, S., Butchart, A., & Cluver, L. (2021). The science of scale for violence prevention: A new agenda for family strengthening in low- and middle-income countries. Frontiers in Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.202

Smith, J. D., Cruden, G. H., Rojas, L. M., Van Ryzin, M., Fu, E., Davis, M. M., Landsverk, J., & Brown, C. H. (2020). Parenting interventions in pediatric primary care: a systematic review. Pediatrics, 146(1).

Smith, J. D., Dishion, T. J., Shaw, D. S., & Wilson, M. N. (2013). Indirect effects of fidelity to the family check-up on changes in parenting and early childhood problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 962.

Smith, J. D., Rudo-Stern, J., Dishion, T. J., Stormshak, E. A., Montag, S., Brown, K., Ramos, K., Shaw, D. S., & Wilson, M. N. (2019). Effectiveness and efficiency of observationally assessing fidelity to a family-centered child intervention: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(1), 16–28.

Stirman, S. W. (2020). Commentary: Challenges and opportunites in the assessment of fidelity and related constructs. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(6), 932–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01069-4

Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 345–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y

Stone, A. A., Bachrach, C. A., Jobe, J. B., Kurtzman, H. S., & Cain, V. S. (1999). The science of self-report: Implications for research and practice. Psychology Press.

Suhrheinrich, J., Dickson, K. S., Chan, N., Chan, J. C., Wang, T., & Stahmer, A. C. (2020). Fidelity assessment in community programs: An approach to validating simplified methodology. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(1), 29–39.

Tiwari, A., Whitaker, D., & Self-Brown, S. (2021). Comparing fidelity monitoring methods in an evidence-based parenting intervention. Journal of Children's Services.

Van Ryzin, M. J., Roseth, C. J., Fosco, G. M., Lee, Y.-K., & Chen, I.-C. (2016). A component-centered meta-analysis of family-based prevention programs for adolescent substance use. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 72–80.

WHO. (2016). INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/inspire-seven-strategies-for-ending-violence-against-children

World Health Organization. (2022). WHO guidelines on parenting interventions to prevent maltreatment and enhance parent–child relationships with children aged 0–17 years. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/violence-prevention/parenting-guidelines

Funding

MM was supported by a doctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Rhodes Trust, and an Alain Locke Studentship from Hertford College. YS was supported by DECIPHer and the Wolfson Centre for Young People’s Mental Health. DECIPHer is funded by Welsh Government through Health and Care Research Wales. The Wolfson Centre for Young People’s Mental Health has been established with support from the Wolfson Foundation. JDS received funding from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U18 DP006255) and the United States Department of Agriculture (2018-68001-27550) for research on the Family Check-Up® 4 Health parenting program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are involved in the evaluation and/or implementation of parenting programs around the world. SB is a co-developer of the second and third editions of the Chicago Parent Program, lead developer for web delivery of the Chicago Parent Program (ezParent), and is on the editorial board of Global Implementation Research and Applications. MM receives occasional fees for providing training and supervision to facilitators and coaches delivering Parenting for Lifelong Health. YS has been involved in evaluations of Parenting for Lifelong Health. JDS is co-developer of the Family Check-Up® 4 Health, an adaptation of the Family Check-Up® parenting program. GS is leader of the Uganda Parenting for Respectability Program, Co-Leader in the Global Parenting Initiative, and has a manuscript under review on experiences of lay facilitators of a community-based parenting program. The remaining authors have no competing interests to report.

Ethical Approval

The plans to share the FIPP survey was shared with The Ohio State University’s institutional ethics committee and was determined to be exempt.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, M., Shenderovich, Y., Caron, E.B. et al. The Case for Assessing and Reporting on Facilitator Fidelity: Introducing the Fidelity of Implementation in Parenting Programs Guideline. Glob Implement Res Appl 4, 1–10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43477-023-00092-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43477-023-00092-5