Abstract

The global prevalence of overweight and obesity is a significant public health concern that also largely affects women of childbearing age. Human epidemiological studies indicate that prenatal exposure to excessive maternal weight or excessive gestational weight gain is linked to various neurodevelopmental disorders in children, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, internalizing and externalizing problems, schizophrenia, and cognitive/intellectual impairment. Considering that inadequate maternal body mass can induce serious disorders in offspring, it is important to increase efforts to prevent such outcomes. In this paper, we review human studies linking excessive maternal weight and the occurrence of mental disorders in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last few decades, obesity has become one of the most pressing social and health complications globally. According to the World Health Organization’s Obesity and Overweight report, 1.9 billion people worldwide were overweight in 2016, of which 650 million were obese [1]. The main causes include improper diet, limited physical activity, and a sedentary lifestyle. The problem of excessive body weight also affects pregnant women and young mothers. In 2014, the number of overweight pregnant women was estimated at 38.9 million, including 14.6 million who were obese [2]. Being overweight is classified based on the body mass index (BMI) of 25 to 30, obesity with a BMI between 30 and 35, and severe obesity with a BMI above 35. The Institute of Medicine and National Research Council recommends the range of weight gain during pregnancy depending on the pre-pregnancy BMI.

Owing to extensive research over past years, it has become clear that excessive maternal body weight also has negative health consequences for the next generation. It is considered one of the components of the phenomenon called Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) or fetal programming [3], in which prenatal and early postnatal exposure of the organism to environmental factors, like maternal obesity, unbalanced diet, stress, and infections leading to maternal immune activation, results in permanent changes in children, predisposing them to various diseases in adulthood. Epidemiological studies showed that, for children, maternal obesity before and during pregnancy is a significant risk factor for the development of obesity [4], asthma, stroke [5], hypertension, and insulin resistance [6]. In addition to typically metabolic diseases, maternal obesity has also been linked to behavioural, cognitive, and psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence [7].

Maternal obesity has also been reported to impact child eating disorders (food addiction, anorexia, or bulimia), substance addiction [8, 9], intellectual disability or cognitive deficits, sleep problems, aggressive behaviour, and many other psychiatric disorders [9, 10]. The neurobiological processes underlying those abnormalities are diverse [11], thus maternal obesity or other metabolic conditions during pregnancy and gestation could be recognized as a potential, rather than a specific, factor increasing the risk of the mentioned psychiatric disorders in children. Further studies are required to determine whether some disorders are more likely to occur than the others [12].

This review aims to discuss whether the mother’s obesity or being overweight before and during pregnancy has an impact on the neuropsychiatric development of her offspring. We reviewed clinical trials linking excessive maternal body weight with neuropsychiatric disorders in children (autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), internalizing and externalizing problems, schizophrenia, and cognitive/intellectual impairment). The results of cohort studies, case–control studies, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews were summarized separately. Given the large amount of published data, the present study gives a broad insight into the association between excessive maternal body weight and the development of various neuropsychiatric disorders in children.

Data sources

The PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases were searched to identify the applicable studies. The purpose of this review was to summarize the currently-available data derived from human studies and associate the impact of maternal risk factors, such as obesity, BMI, and Gestational Weight Gain (GWG), on child neurodevelopmental disorders (ASD, ADHD, schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression, etc.) using keywords from 3 principal groups and a search combining groups: (1) ADHD or ASD or schizophrenia or anxiety or depression or neurodevelopmental or internalizing/externalizing problems; (2) pregnancy or offspring or maternal; (3) obesity or overweight or BMI or GWG. Relevant articles, including experimental research, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and cohort studies published after 2010, were reviewed and synthesized to form the basis of this narrative review, however, for systematic purposes, some older publications have also been included.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

ASD is one of the neurobiological dysfunctions with an unexplored influence of prenatal environmental factors. ASD is typically diagnosed in early childhood, a lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent deficits in the ability to initiate and sustain reciprocal social interaction and social communication with the additional presence of several restricted, repetitive, and inflexible patterns of behaviour, interests, or activities [13]. Large cohort studies from Finland [14], USA (California) [15, 16], and Sweden [17] reported a significant association between maternal weight during pregnancy and the risk of ASD in children (Table 1). The results showed that the occurrence of ASD in children of obese mothers was 25–28%, 60%, or even 94% higher, respectively, compared to children of mothers with a normal BMI. The Kong et al. (2018) cohort study revealed that pre-pregnancy (PP) maternal obesity (MOb) was associated with a slightly increased risk of psychiatric disorders and mild risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in children. These risks were significantly higher in the offspring of severely obese mothers and when comorbid with gestational or pre-gestational diabetes [14]. The follow-up time in this study was not the same for the entire cohort, so this data may be underestimated. BMI was examined only at 1 point, therefore GWG was not assessed. Maternal PP BMI > 30 was reported to be associated with a 37% higher likelihood of ASD and gastrointestinal disturbances comorbidity in children [16]. The authors point out the importance of maternal immune activation as a factor predisposing the occurrence of ASD in children. Excessive adipose tissue triggering immune activation in pregnant women is a suggested mechanism involved in the impairment of brain maturation in children [16, 18, 19]. In a multisite case–control study in the USA, severe obesity (BMI > 35) in mothers led to an almost 87% higher risk of ASD [20], while the prospective birth cohort study showed that each 5-point increase in maternal PP BMI was related to a 38% increase in ASD risk occurrence in children [21]. This study used parents’ reports regarding ASD diagnosed by a doctor based on special questionnaires, but the consistency of the information with medical records was not confirmed. Although Matias et al. (2021) did not find a significant association between pregnancy maternal overweight (PP MOv) and ASD risk, the meta-analysis, which included 36 cohorts, demonstrated that the children of overweight mothers are 10% more likely to be diagnosed with ASD [22]. Furthermore, when a mother’s BMI was higher than 30, the risk of ASD occurrence increased to 36%. Moreover, a large retrospective cohort study in Sweden showed that increasing the mother’s pre-pregnancy BMI value above 21 was associated with a higher risk of ASD. Surprisingly, the results from the fathers’ BMI analysis and the sibling analysis suggest that these results are influenced by residual confounding factors and that the mothers’ BMI may be a proxy for other risk factors shared by members of the same family, such as genetics [17].

Independently, GWG is also considered a critical factor for a higher ASD risk. Three cohort studies suggest that its role is even more crucial than that of PP MOb [17, 23, 24]. The data also showed that, even in matched-siblings analysis, the association with GWG is still present while the link with PP MOb is attenuated [17]. Other studies indicate that the association between GWG and ASD in children is further strengthened by MOv/MOb [23, 25]. In turn, research by Dodds et al. (2011) indicates that, in genetically ASD-susceptible children, factors such as high maternal BMI or GWG play a minor role [26]. In another study, the exact association between GWG and the risk of ASD was estimated: each 5-pound (~ 2.26 kg) rise in GWG increased the odds of ASD by 10–17% [24]. Windham et al. (2019) also obtained comparable results, where the risk of ASD was estimated at 6% for each 5-pound increase in GWG [25]. Interestingly, an elevated risk of ASD was observed for excessively low GWG, providing evidence that maternal undernutrition during pregnancy may also contribute to ASD risk [17].

The link between GWG and ASD risk in children is supported by meta-analysis (based on 5 cohort studies and 4 case–control studies), which showed that excessive GWG increased ASD risk by 10% (for cohort studies) and 38% (for case–control studies) [27]. However, this meta-analysis did not confirm the significant correlation between the risk of ASD in children and inadequate maternal GWG (including both higher and lower rates than recommended).

Summarizing, numerous studies confirm a positive correlation between high BMI before pregnancy and the occurrence of ASD in children, however, excessive GWG seems to be a more critical factor, additionally reinforced by MOv and MOb. The literature reports a significant impact of other factors predisposing the development of ASD in children, such as pre-eclampsia, pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes [17], cholesterol level, or dyslipidemia [14]. However, it should be noted that elevated BMI is a core feature defining the metabolic syndrome and is strongly associated with the development of the metabolic pregnancy complications listed above.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder typically diagnosed in childhood, and its features may also be observed in adulthood. Axial symptoms of ADHD include inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity, which has a direct negative impact on the academic/occupational or social functioning of a person [28].

The exact aetiology of ADHD remains unclear. Research results indicate complex determinants of ADHD, including genetic predispositions and the influence of environmental factors. The data on the influence of the mother’s BMI and GWG on the risk of ADHD symptoms in the child is not as clear as in the case of ASD. Recent studies suggest that environmental factors, such as PP and pregnancy MOv and/or MOb, contribute to an increased risk of ADHD in children (Table 2). Analysis of the results of the first large prospective cohort study showed that children of women who were overweight and gained significant weight during pregnancy were twice as likely to develop ADHD symptoms compared to women with normal body weight [29]. These results persisted after adjustment for various confounding factors, such as smoking during pregnancy, gestational age, weight gain, birth weight, infant sex, mother’s age, mother’s education, and family structure. There was also an increased risk of ADHD symptoms among the children of slim mothers who lost weight, suggesting that complications rather than weight are an important factor. It should be noted that, in this study, the assessment of the presence of ADHD symptoms was made by teachers working with children, which was not synonymous with diagnosis. All symptoms were significantly more common in boys than in girls, consistent with the known sex-dependent distribution of ADHD [29]. Subsequent cohort studies confirmed that PP MOv and PP MOb (but not underweight) were dose-dependently associated with an increased risk of ADHD in children [30,31,32]. However, after taking into account comparisons with siblings, these relationships were weakened. Therefore, the authors attributed the relationship between overweight/obesity in the mother before pregnancy and ADHD in children to unmeasured family complications, e.g., genetics [31]. Although increased PP maternal BMI was shown to be a significant factor, no significant relationship for GWG was found [29, 30, 33]. The results of recent research have shown that the risk of ADHD is dependent on the trimester of gestation in which excessive weight gain occurs. Thus, they indicated that slow weight gain in the second trimester followed by rapid weight gain in the third trimester most significantly increases this risk [34]. According to the results of two conducted independent meta-analyses, the risk of ADHD occurrence in the children of overweight mothers is 30% higher compared to those of normal weight [22, 35]. MOb, in turn, increased the risk of ADHD by up to 62% [22], or 59% after adjustment for known risk factors, such as smoking, maternal age, birth weight, prematurity, and Caesarean section, in the long-term prospective study (17.7 years) by Perea et al. (2022). This risk increased to 66% with a diagnosis of gestational diabetes [33], and when the combined contributions of maternal weight and excessive weight gain (EWG) were assessed, these two factors together were associated with the highest risk of ADHD (2.13 times the risk when compared to normal weight without EWG). When the influence of measured confounding factors (i.e., maternal age, maternal education, smoking, year and country of birth, and sex of the child, etc.) was taken into consideration, the data showed a lower impact of obesity and being overweight on the risk of ADHD occurrence (21 and 60%, respectively). Li et al. (2021) suggested that the impact of unmeasured familial confounding factors could further attenuate the link between MOb and ADHD [36], while a recent cohort study showed that PP MOb, but not MOv, is associated with a higher risk of ADHD symptoms [37].

An umbrella review also confirmed the positive correlation between MOb and ADHD in children. The authors define MOb as a convincing factor for the higher risk of ADHD occurrence in children and place it amongst four other factors most associated with the risk of ADHD (i.e., childhood eczema, hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, preeclampsia, and exposure to acetaminophen during pregnancy). They suggest that the impact of MOb may be more significant than maternal smoking during pregnancy. Although these associations remain robust, the authors note that other confounding factors should be taken into consideration [38].

The above data indicates a strong relationship between PP MOb and ADHD symptoms in children. Moreover, numerous studies indicate that MOv may also contribute to the development of this disorder. It seems to be valuable to assess this relationship in the context of the child’s sex. Frazier et al. (2023) found that both MOv and MOb affect child development differently depending on sex, but research specifically on ADHD in this area is very limited [7].

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder characterized by the presence of several disturbances in the areas of thinking, perception and self-perception, cognition, volition, affect, and behaviour [13]. It is most often diagnosed in early adulthood and, despite treatment progress, it is a significant cause of disability. Only a limited number of studies have examined the impact of MOb on the higher risk of schizophrenia in children (Table 3). Existing data shows an increased risk of schizophrenia in children for excessive, but also deficient, maternal BMI rates.

A 28-year follow-up study conducted on the Finnish birth cohort suggests a two-fold increased risk of schizophrenia for children of obese mothers (BMI > 29) compared to those of mothers with a BMI of 19.1–29.0 [39, 40]. However, when adjusted for confounders (sex, social class, age of mother), these findings were no longer statistically significant [39]. A study conducted on the American cohort born between 1959 and 1967 reports an almost three-fold increased risk of schizophrenia and spectrum disorders due to maternal PP BMI > 30 compared to the average BMI (20.0–26.9). Unlike the Finnish experiment, these findings were significant even after adjusting for confounders, such as maternal age, parity, race, education, and cigarette smoking during pregnancy, but no such relationship was found when the mother’s BMI was lower than 19.9 [41]. Furthermore, Kawai et al. (2004) investigated the relationship between the risk of schizophrenia in children and BMI, including BMI during early and late pregnancy [42]. They found a significant association between the increased risk of schizophrenia for each unit of maternal BMI in both early (24% higher risk) and late (19% higher risk) pregnancy. It should also be mentioned that a low mother’s BMI may predispose the development of schizophrenia in the child.

On the other hand, the study based on cohort births from 1924 to 1933 in Finland reported that the risk of schizophrenia in children was related to low maternal BMI (< 24) rather than to BMI > 30. The authors consider their findings to be different from more recent observations due to the dissimilar economic situation in the 1930s. They link their observations with the lack of welfare structures, illness, and malnutrition at that time. These results are also confirmed by observations from a cohort of children in China, conceived during the 1959–1961 famine, which showed a twofold increased risk of schizophrenia [43]. Currently, in Western populations, where nutritional status is good, a higher maternal BMI is more likely to be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders than malnutrition [44].

Internalizing and externalizing problems

The terms internalizing and externalizing problems are an alternative to the classic diagnostic criteria way of grouping mental disorders and emotional problems that appear in childhood and adolescence. Internalizing problems usually include depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal. Externalizing problems include aggression, lack of cooperation with adults, violations of rules, and impulsivity. These descriptions are supplemented by nosological criteria including major depressive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD, and conduct disorders. Together, in a broader sense, they constitute two groups of disorders with certain common features, but having different severity and clinical pictures, often including symptoms from both groups. However, in research on mental disorders of children and adolescents, these terms are often used in both a broader and narrower sense [45].

Epidemiological studies show that internalization and externalization problems diagnosed in children could also be linked to maternal BMI (Table 4). The cohort study on an Australian sample of 2785 offspring-mother pairs has examined internalizing (anxious/depressed) and externalizing (behavioural) problems. During the study, mothers were asked to fill in the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) when their children were 5, 8, 10, 14, and 17 years old. The results confirmed that increased maternal BMI was associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems. Although the intensity of both types of problems diminished with age (as it should have done), in children of mothers with high BMI, a less rapid decrease in anxious/depressed symptoms was reported. These findings were statistically significant even after adjusting for confounders [46]. Robinson et al. (2013), using the same data (same cohort and method), estimated that the risk of affective problems (including depression) for children of obese and overweight mothers was 72 and 51% higher, respectively, compared to the children of mothers with normal PP BMI [47]. Those findings are consistent with the cohort study conducted on the Finnish population of children born between 2004 and 2014, which reported that severely obese mothers (BMI > 35) had a 67% higher risk of having a child with psychosis, mood, and anxiety disorders, compared to children of mothers with normal weight [14]. Similarly, anxiety-related problems have been observed when a mother’s PP BMI was higher than 40 (very severe obesity), but no consistent impact on internalizing problems in children has been revealed [10]. MOb has also been associated with increased emotional dysregulation (sadness and fear) [48], which can be a risk factor for future psychological difficulties, including anxiety and depression [49].

Very interesting and unexpected results were provided by a cohort study described by Tanda & Salsberry (2014) which compared the effect of BMI of White and African American women on the development of internalizing and externalizing disorders in children [50]. PP MOb in White women was associated with an average increase in BPI total score of 4.3 units in the Behavioral Problems Index (BPI) compared with mothers who were of normal weight before pregnancy, with other factors held constant. PP MOv was marginally associated with BPI total scores, holding other factors constant (p = 0.062). Moreover, maternal underweight was also associated with a greater risk of behavioural problems in children, however, after taking into account maternal age and prenatal smoking, it reduced the size and strength of the association to a non-significant level. On the other hand, among African American children, not only was PP MOb a non-significant contributor to the BPI total score, but the direction of the coefficient was also opposite to that among Whites. Neither PP MOv nor being underweight was associated with children’s total BPI scores. Most of the data came from mothers’ self-reports, including the mother’s pre-pregnancy weight, so weight may be underestimated in obese and overestimated in underweight individuals [50]. The lack of consistency in the association between a child’s behavioural problem scores and maternal pre-pregnancy obesity in both racial groups sheds new light on risk factors. These results indicate that the association between pre-pregnancy maternal obesity and child behaviour problems may be largely driven by unfavourable social characteristics.

Cognitive impairment and intellectual disability

Data from studies examining intellectual abilities in children further confirms the detrimental impact of excessive maternal BMI, however, there is not full agreement on this matter (Table 5). Most cohort and observational studies connect MOb with the decrease in child IQ points [51, 52] and poor cognitive performance, including motor, spatial, and verbal skills [53, 54]. In a study conducted by Pugh et al. (2015), lower IQ and worse executive function test results were reported in children of obese mothers, however, excessive GWG does not affect the child’s IQ [55]. In turn, another study reported that there are no solid associations between maternal BMI and cognition in children [56]. In addition, U-shaped associations have been determined, suggesting that inadequately low maternal PP weight is significantly associated with lower IQ rates in children [57,58,59].

Summary

The number of papers investigating the issue of inadequate maternal BMI and its consequences in children clearly indicates that this topic has gained interest. The issue of parental obesity may be of even greater public health concern as there are animal studies [12, 60] and epidemiological studies [61] reporting multi-generational adverse effects of excess body weight. Most of the data confirms significant adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in children caused by MOv/MOb and/or excessive GWG. However, epidemiological studies do not provide explanations of the mechanisms involved in the development of the observed disorders. Certainly, all these diseases have multifactorial aetiology and heterogeneous presentation, and the factors discussed in this article are just some of many. Nevertheless, the acquired observations serve as guidance in planning animal studies, which in turn aim at understanding those mechanisms.

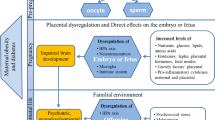

The mother’s weight may influence the child’s mental condition through various mechanisms. The first and most obvious of these may be related to the common genetic risk of obesity and mental disorders. Co-occurring obesity and mental disorders in mothers may also affect the quality of nutrition, bonding with the child, and the child’s emotional self-regulation. The occurrence of obesity is also associated with the presence of several other risk factors for mental disorders, such as physical activity level, alcohol consumption, and socio-economic status [62]. Each of the above-mentioned individual risk factors may have consequences in the occurrence of further phenomena increasing the risk of mental disorders [63]. Maternal obesity may affect the course of pregnancy itself—the mother’s health during pregnancy, the length of pregnancy, and the birth weight of the child [64]. A relatively large amount of clinical data refers to the epigenetic impact of maternal obesity on the child’s development, including the development of the central nervous system, through the negative consequences of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis deregulation, early-onset intensification of inflammatory processes, and oxidative stress. The transition of microbiota between the mother and the child may also be important. All these phenomena can co-occur and influence each other [64, 65].

The research has many limitations. The most important of them is related to the use of different diagnostic criteria for disorders and diagnostic strategies in different studies. This especially limits conclusions regarding anxiety and depressive disorders, which were based on both clinical diagnoses and self-report tools or descriptions of the child’s behaviour. Moreover, paternal data and parental genetic information were unavailable in the study, so paternal factors and genetic contributions to the likelihood of disease were not controlled. There may be other potential confounding factors, such as environmental exposures and postnatal risk factors, like childhood diet and household exposures, that could not be controlled in the studies. Research on maternal obesity and its impact on the risk of mental disorders should also differentiate the nature of maternal obesity and the dynamics of its increase. Did obesity occur in adolescence or did it appear later in life? How much weight was gained during pregnancy? Is obesity associated with the failure to follow the rules of a healthy diet? These are some of the questions that would allow for a more thorough examination of the analysed relationships.

Since there are no effective measures to counteract harmful effects in children once they have occurred, prevention appears to be the best strategy. Body weight is controlled during pregnancy, and its gain is a potentially modifiable factor. It seems very important to control proper weight gain, taking into account PP BMI, by the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council, and likewise aim to maintain a healthy BMI when planning a pregnancy. The above data should help implement early interventions for mothers of high-risk infants.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ASD:

-

Autism spectrum disorder

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DOHaD:

-

Developmental origins of health and disease

- EWG:

-

Excessive weight gain

- GWG:

-

Gestational weight gain

- PP:

-

Pre-pregnancy

- MOv:

-

Maternal overweight

- MOb:

-

Maternal obesity

References

WHO. Obesity and Overweight Fact Sheet. World Health Organization. 2020.

Chen C, Xu X, Yan Y. Estimated global overweight and obesity burden in pregnant women based on panel data model. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202183 (Painter R, editor).

Gluckman PD, Buklijas T, Hanson MA. Chapter 1–the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) concept: past, Present, and Future. In: Rosenfeld CS, editor. The Epigenome and Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Boston: Academic Press; 2016. p. 1–15 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128013830000013).

Dai R-X, He XJ, Hu CL. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and the risk of macrosomia: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297(1):139–45.

Godfrey KM, Reynolds RM, Prescott SL, Nyirenda M, Jaddoe VWV, Eriksson JG, et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:53–64.

Dong M, Zheng Q, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW, Ren J. Maternal obesity, lipotoxicity and cardiovascular diseases in offspring. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;55:111–6.

Frazier JA, Li X, Kong X, Hooper SR, Joseph RM, Cochran DM, et al. Perinatal factors and emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dysregulation in childhood and adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62:1351–62.

Rivera HM, Christiansen KJ, Sullivan EL. The role of maternal obesity in the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Neurosci. 2015;9(MAY):194.

Edlow AG. Maternal obesity and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in offspring. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(1):95–110.

Mina TH, Lahti M, Drake AJ, Räikkönen K, Minnis H, Denison FC, et al. Prenatal exposure to very severe maternal obesity is associated with adverse neuropsychiatric outcomes in children. Psychol Med. 2017;47(2):353–62.

De Berardis D, De Filippis S, Masi G, Vicari S, Zuddas A. A neurodevelopment approach for a transitional model of early onset schizophrenia. Brain Sci. 2021;11(2):275.

Urbonaite G, Knyzeliene A, Bunn FS, Smalskys A, Neniskyte U. The impact of maternal high-fat diet on offspring neurodevelopment. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:1148.

World Health Organization (WHO). ICD-11: International classification of diseases. 2022;2020:1–23.

Kong L, Norstedt G, Schalling M, Gissler M, Lavebratt C. The risk of offspring psychiatric disorders in the setting of maternal obesity and diabetes. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20180776.

Krakowiak P, Walker CK, Bremer AA, Baker AS, Ozonoff S, Hansen RL, et al. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1121–8.

Carter SA, Lin JC, Chow T, Yu X, Rahman MM, Martinez MP, et al. Maternal obesity, diabetes, preeclampsia, and asthma during pregnancy and likelihood of autism spectrum disorder with gastrointestinal disturbances in offspring. Autism. 2023;27(4):916–26.

Gardner RM, Lee BK, Magnusson C, Rai D, Frisell T, Karlsson H, et al. Maternal body mass index during early pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and risk of autism spectrum disorders: results from a Swedish total population and discordant sibling study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):870–83.

de Kaminski VL, Michita RT, Ellwanger JH, Veit TD, Schuch JB, Riesgo RDS, et al. Exploring potential impacts of pregnancy-related maternal immune activation and extracellular vesicles on immune alterations observed in autism spectrum disorder. Heliyon. 2023;9(5):e15593.

Paysour MJ, Bolte AC, Lukens JR. Crosstalk between the microbiome and gestational immunity in autism-related disorders. DNA Cell Biol. 2019;38(5):405–9.

Matias SL, Pearl M, Lyall K, Croen LA, Kral TVE, Fallin D, et al. Maternal prepregnancy weight and gestational weight gain in association with autism and developmental disorders in offspring. Obesity. 2021;29(9):1554–64.

Joung KE, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Mantzoros CS. Maternal midpregnancy leptin and adiponectin levels as predictors of autism spectrum disorders: a prenatal cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(10):E4118–27.

Sanchez CE, Barry C, Sabhlok A, Russell K, Majors A, Kollins SH, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and child neurodevelopmental outcomes: a meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2018;19(4):464–84.

Shen Y, Dong H, Lu X, Lian N, Xun G, Shi L, et al. Associations among maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain and risk of autism in the han chinese population. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1593-2.

Bilder DA, Bakian AV, Viskochil J, Clark EAS, Botts EL, Smith KR, et al. Maternal prenatal weight gain and autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1276-1283.

Windham GC, Anderson M, Lyall K, Daniels JL, Kral TVE, Croen LA, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain in relation to autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disorders in offspring. Autism Res. 2019;12(2):316–27.

Dodds L, Fell DB, Shea S, Armson BA, Allen AC, Bryson S. The role of prenatal, obstetric and neonatal factors in the development of autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2011;41(7):891–902.

Su L, Chen C, Lu L, Xiang AH, Dodds L, He K. Association between gestational weight gain and autism spectrum disorder in offspring: a meta-analysis. Obesity. 2020;28(11):2224–31.

Doernberg E, Hollander E. Neurodevelopmental disorders (ASD and ADHD): DSM-5, ICD-10, and ICD-11. CNS Spectr. 2016;21(4):295–9.

Rodriguez A, Miettunen J, Henriksen TB, Olsen J, Obel C, Taanila A, et al. Maternal adiposity prior to pregnancy is associated with ADHD symptoms in offspring: evidence from three prospective pregnancy cohorts. Int J Obes. 2008;32(3):550–7.

Buss C, Entringer S, Davis EP, Hobel CJ, Swanson JM, Wadhwa PD, et al. Impaired executive function mediates the association between maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and child ADHD symptoms. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e37758.

Chen Q, Sjölander A, Långström N, Rodriguez A, Serlachius E, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and offspring attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study using a sibling-comparison design. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):83–90.

Daraki V, Roumeliotaki T, Koutra K, Georgiou V, Kampouri M, Kyriklaki A, et al. Effect of parental obesity and gestational diabetes on child neuropsychological and behavioral development at 4 years of age: the Rhea mother-child cohort, Crete. Greece Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;26(6):703–14.

Perea V, Simó-Servat A, Quirós C, Alonso-Carril N, Valverde M, Urquizu X, et al. Role of excessive weight gain during gestation in the risk of adhd in offspring of women with gestational diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(10):e4203–11.

Chen S, Fan M, Lee BK, Dalman C, Karlsson H, Gardner RM. Rates of maternal weight gain over the course of pregnancy and offspring risk of neurodevelopmental disorders. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):108.

Jenabi E, Bashirian S, Khazaei S, Basiri Z. The maternal prepregnancy body mass index and the risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Pediatr. 2019;62(10):374–9.

Li L, Lagerberg T, Chang Z, Cortese S, Rosenqvist MA, Almqvist C, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity and the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: A systematic review, metaanalysis and quasi-experimental family-based study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;49(3):857–75 (https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/49/3/857/5825422).

Dow C, Galera C, Charles MA, Heude B. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and offspring hyperactivity–inattention trajectories from 3 to 8 years in the EDEN birth cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;32:2057–65.

Kim JH, Kim JY, Lee J, Jeong GH, Lee E, Lee S, et al. Environmental risk factors, protective factors, and peripheral biomarkers for ADHD: an umbrella review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(11):955–70.

Jones PB, Rantakallio P, Hartikainen AL, Isohanni M, Sipila P. Schizophrenia as a long-term outcome of pregnancy, delivery, and perinatal complications: a 28-year follow-up of the 1966 North Finland general population birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(3):355–64.

Khandaker GM, Dibben CRM, Jones PB. Does maternal body mass index during pregnancy influence risk of schizophrenia in the adult offspring? Obes Rev. 2012;13(6):518–27.

Schaefer CA, Brown AS, Wyatt RJ, Kline J, Begg MD, Bresnahan MA, et al. Maternal prepregnant body mass and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26(2):275–86.

Kawai M, Minabe Y, Takagai S, Ogai M, Matsumoto H, Mori N, et al. Poor maternal care and high maternal body mass index in pregnancy as a risk factor for schizophrenia in offspring. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110(4):257–63.

St Clair D, Xu M, Wang P, Yu Y, Fang Y, Zhang F, et al. Rates of adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to the Chinese famine of 1959–1961. JAMA. 2005;294(5):557–62.

Wahlbeck K, Forsén T, Osmond C, Barker DJP, Eriksson JG. Association of schizophrenia with low maternal body mass index, small size at birth, and thinness during childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):48–52.

Sallis H, Szekely E, Neumann A, Jolicoeur-Martineau A, van IJzendoorn M, Hillegers M, et al. General psychopathology, internalising and externalising in children and functional outcomes in late adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60(11):1183–90.

Van Lieshout RJ, Robinson M, Boyle MH. Maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index and internalizing and externalizing problems in offspring. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(3):151–9.

Robinson M, Zubrick SR, Pennell CE, Van Lieshout RJ, Jacoby P, Beilin LJ, et al. Pre-pregnancy maternal overweight and obesity increase the risk for affective disorders in offspring. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2013;4(1):42–8.

Rodriguez A. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and risk for inattention and negative emotionality in children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2010;51(2):134–43.

Gustafsson HC, Kuzava SE, Werner EA, Monk C. Maternal dietary fat intake during pregnancy is associated with infant temperament. Dev Psychobiol. 2016;58(4):528–35.

Tanda R, Salsberry PJ. Racial differences in the association between maternal prepregnancy obesity and children’s behavior problems. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(2):118–27.

Coo H, Fabrigar L, Davies G, Fitzpatrick R, Flavin M. Are observed associations between a high maternal prepregnancy body mass index and offspring IQ likely to be causal? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(10):920–8.

Bliddal M, Olsen J, Støvring H, Eriksen HLF, Kesmodel US, Sørensen TIA, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and intelligence quotient (IQ) in 5-year-old children: A cohort based study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94498. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094498.

Basatemur E, Gardiner J, Williams C, Melhuish E, Barnes J, Sutcliffe A. Maternal prepregnancy BMI aNd child cognition: a longitudinal cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):56–63.

Casas M, Chatzi L, Carsin AE, Amiano P, Guxens M, Kogevinas M, et al. Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity, and child neuropsychological development: two southern european birth cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(2):506–17.

Pugh SJ, Richardson GA, Hutcheon JA, Himes KP, Brooks MM, Day NL, et al. Maternal obesity and excessive gestational weight gain are associated with components of child cognition. J Nutr. 2015;145(11):2562–9.

Brion MJ, Zeegers M, Jaddoe V, Verhulst F, Tiemeier H, Lawlor DA, et al. Intrauterine effects of maternal prepregnancy overweight on child cognition and behavior in 2 cohorts. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e202–11.

Hinkle SN, Schieve LA, Stein AD, Swan DW, Ramakrishnan U, Sharma AJ. Associations between maternal prepregnancy body mass index and child neurodevelopment at 2 years of age. Int J Obes. 2012;36(10):1312–9.

Huang L, Yu X, Keim S, Li L, Zhang L, Zhang J. Maternal prepregnancy obesity and child neurodevelopment in the Collaborative Perinatal Project. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):783–92.

Neggers YH, Goldenberg RL, Ramey SL, Cliver SP. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and psychomotor development in children. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(3):235–40.

Anwer H, Morris MJ, Noble DWA, Nakagawa S, Lagisz M. Transgenerational effects of obesogenic diets in rodents: A meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2022;23(1):e13342.

Kanmiki EW, Fatima Y, Mamun AA. Multigenerational transmission of obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2022;23(3):e13405.

Flores-Dorantes MT, Díaz-López YE, Gutiérrez-Aguilar R. Environment and gene association with obesity and their impact on neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental diseases. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:863.

Batko B, Szwajca M, Śmierciak N, Krzyściak W, Turek A, Pilecki M. Risk factors for weight gain in patients with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Pol. 2023;57(1):51–64.

Cattane N, Räikkönen K, Anniverno R, Mencacci C, Riva MA, Pariante CM, et al. Depression, obesity and their comorbidity during pregnancy: effects on the offspring’s mental and physical health. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(2):462–81.

Cirulli F, Musillo C, Berry A. Maternal obesity as a risk factor for brain development and mental health in the offspring. Neuroscience. 2020;447:122–35.

Kheirouri S, Alizadeh M. Maternal excessive gestational weight gain as a risk factor for autism spectrum disorder in offspring: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-03324-w.

Zhang S, Lin T, Zhang Y, Liu X, Huang H. Effects of parental overweight and obesity on offspring’s mental health: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(12): e0276469.

Funding

Narodowe Centrum Nauki, 2015/19/D/NZ7/00082, Lucyna Pomierny-Chamiolo, Uniwersytet Jagielloński Collegium Medicum, N42/DBS/000315, Lucyna Pomierny-Chamiolo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. Kacperska: Investigation, Software, Writing—Original Draft J. Mizera: Investigation, Software, Writing—Original Draft M. Pilecki: Investigation, Writing—Original Draft L. Pomierny–Chamiolo: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing—Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sources of support

The manuscript was supported by Statutory Funds of the Department of Toxicology, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Poland, number: N42/DBS/000315, and grant 2015/19/D/NZ7/00082, National Science Centre, Poland.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kacperska, M., Mizera, J., Pilecki, M. et al. The impact of excessive maternal weight on the risk of neuropsychiatric disorders in offspring—a narrative review of clinical studies. Pharmacol. Rep 76, 452–462 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-024-00598-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43440-024-00598-1