Abstract

The global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 has triggered profound changes in the macro-financial regulatory architecture. Ever since, the interplay between political, institutional, and macroeconomic developments has received increasing attention in political economy, as in the evolutionary macro-financial approach of institutional super-cycles with its concept of thwarting mechanisms. While these institutional structures aim to stabilise the macro-financial system, they may also contradict each other due to unintended side effects. This paper argues that the understanding of thwarting mechanisms can be enriched by further integrating it with political economy literature on finance within the post-GFC institutional setup. It conceptualises unconventional monetary policy as a novel thwarting mechanism and analyses the contradictory implications for overall macro-financial stability with a particular focus on aggregate demand. It suggests three reasons why this thwarting mechanism failed to restore sustained economic growth in the post-crisis decade: First, sustained large-scale asset purchases perpetuate the structural drivers of financial dominance in political power relations, entrenching the role of the shadow banking system within the macro-financial order and impairing the development of other thwarting mechanisms. Second, unconventional monetary policy maintains the tenets of the inflation targeting regime and thereby sustains neoliberal macroeconomic governance with restrained fiscal policy. Third, it exacerbates preexisting wealth and income inequality by redistributing wealth towards asset owners, undermines consumer demand, and thus contributes to stagnation tendencies. Thus, this paper suggests that the contradictions of this novel post-GFC thwarting mechanism contribute to weaken economic growth and thus fail to restore macro-financial stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 changed the financial system fundamentally and permanently. It also marked the beginning of a new era of hitherto unconventional monetary policy (UMP) of balance sheet expansions that was further entrenched during the Covid-19 financial crisis (Wullweber 2020b). However, these measures could only achieve temporal stabilisation (IMF 2019) because the principal working mechanisms and destabilising contradictions of the shadow banking system remained largely untouched (Tooze 2018). Sporadic outbreaks of market turmoil such as the repo-market crash in September 2019 or more recently the UK gilt crisis (Pinter 2023) remind of the inherent fragility of a financial system permanently ‘operating in crisis mode’ (Wullweber 2021b, 12). More importantly though, central banks’ unprecedented balance sheet expansions were unexpectedly unable to restore sustained economic growth, with Euro area real GDP remaining practically stagnant during the post-GFC decade, hovering around US $16 trillion (World Bank 2023), while US GDP growth remained largely below its precrisis averages with a sluggish 1.6% compared to the almost double 3.1% between 1972 and 2004 (Gordon 2015, 55). Although long-term interest rates remained low during the post-crisis recovery period, productive investment did so, too (Palley 2014; Hein 2016; Tymoigne 2016).

This conundrum ignited a vivid debate among economists. While the supply-side-focused ‘secular stagnation’ hypothesis received much attention throughout the economics mainstream (Eichengreen 2015; Gordon 2015), three heterodox schools of economic thought provided alternative and contradicting interpretations: the Austrian school of economics among its market-liberal audience (Schnabl 2017) deemed market interventions and ensuing price distortions as main culprits, while Marxist (Bonizzi and Powell 2020) and post-Keynesian (Palley 2009, 2015; Stockhammer 2015) accounts rather emphasised demand-side factors such as austere fiscal policy and stagnant real wages, gaining traction within critical research and left-wing policy circles. This paper chimes in this discussion to answer the question why UMP failed to restore sustained economic growth in the post-crisis decade, despite unprecedented balance sheet expansions.

It seeks to add to this debate by extending the scope of analysis to political economy, connecting key insights from its literature on shadow banking and monetary policy (Gabor 2016b; Murau 2017; Gabor and Ban 2016; Wullweber 2021a) to demand-side-oriented economics explanations of the protracted crisis in advanced capitalist countries. In doing so, it also aims to forward methodological pluralism in economic research by drawing on the critical macro-finance approach of ‘institutional super-cycles’ that integrates insights from institutionalist, evolutionary, and post-Keynesian economics with political economy (Dafermos et al. 2023). This approach builds substantially on the Minskyian concept of ‘thwarting mechanisms’ — institutional structures that aim to counteract the inherently destabilising tendencies of capitalism laid out in his financial instability hypothesis (Ferri and Minsky 1992; Minsky 2008; Lavoie 2020). However, the effectiveness of these structures to stabilise the macro-financial system deteriorates over time as a result of the very same tendencies as well as deeper political and ideological conflicts, requiring the emergence of new institutional structures and spawning a secular pattern of super-cycles that comprise several standard business cycles (Palley 2011).

Institutional super-cycles differ substantially from most ahistorical agent-based macroeconomic models of post-Keynesian and evolutionary economics (Calvert Jump and Stockhammer 2023) because they put the historically specific political economy of contingent institutional development to the centre of analysis. Conversely, the latter rather focus on integrating institutions into mechanic models that seek to be universally applicable (Kapeller and Schütz 2014). Thus, the analysis of historically specific thwarting mechanisms can significantly advance our understanding of the protracted crisis in advanced capitalist countries during the past decade by going beyond purely macroeconomic considerations, extending the analytical scope towards ideology, power relations between market and state, and inequality. However, there has been only little empirical elaboration on thwarting mechanisms beyond its conceptualisation so far, which is why Dafermos et al. (2023, 13) call for ‘further research […] on the links between macro-financial stability and thwarting mechanisms’.

This paper seeks to fill this gap in the literature, with its key contribution going beyond Dafermos et al. (2023) being to conceptualise UMP as a new thwarting mechanism that emerged in the wake of the GFC and explain why it ultimately failed to stabilise the macro-financial system in the long run by means of sustained economic growth. Thereby, it goes beyond merely recognising the ‘[k]ey features of the institutional architecture of the [current] supercycle’ of ‘weak and “flexible” labour, high inequality and government retrenchment’ (Dafermos et al. 2023, 13) but attempts to shed light on the specific role that monetary policy itself partly plays in upholding this configuration. In this way, it also adds a new theoretical angle to contributions from political economy on the contradictions of UMP (Wansleben 2023) and ‘central bank capitalism’ (Wullweber 2021b).

Informed by this holistic theoretical approach and empirical evidence provided by descriptive statistics from secondary literature and financial institutions, it suggests three reasons why UMP failed to restore sustained economic growth in the post-crisis decade. First, UMP perpetuates the structural drivers of financial dominance in society by entrenching the role of the shadow banking system within the overall macro-financial system. Second, it remains within the neoliberal macroeconomic policy paradigm and thus contributes to upholding the imperative of fiscal austerity. Third, it nurtured the exacerbation of wealth and income inequality via asset price inflation and thereby contributed to supress aggregate demand.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows: ‘The political economy of institutional super-cycles: thwarting mechanisms’ section outlines the institutional super-cycles approach and operationalises the concept of thwarting mechanisms for political economy analysis. The ‘Unconventional monetary policy as a new thwarting mechanism’ section conceptualises UMP as a new post-GFC thwarting mechanism. The subsequent sections analyse its impact on the macro-financial system alongside three dimensions: ‘The political economy of unconventional monetary policy and financial dominance’, ‘The continuation of the neoliberal monetary-fiscal policy nexus, and the ‘Distributional consequences of unconventional monetary policy’. The ‘Conclusion’ section concludes that these concomitants of UMP paradoxically contributed to weaken aggregate demand and economic growth, failing to restore macro-financial stability and thus the onset of a new institutional super-cycle.

2 The political economy of institutional super-cycles: thwarting mechanisms

The macroeconomic debate on the causes of the GFC and the ensuing sluggish recovery was accompanied by a crisis of the profession of macroeconomics itself (Krugman 2011). Besides criticism from other economic schools of thought, many also called for more theoretical pluralism and interdisciplinary engagement (Dobusch and Kapeller 2012; Sawyer 2020), also within international political economy (Wullweber 2018). Dafermos et al. (2023) provided such an attempt by suggesting a synthesis between institutionalist and evolutionary approaches of post-Keynesian economics on the one hand and international political economy on the other.

They build upon the Minskyian concept of ‘thwarting mechanisms’, a term used to describe ‘customs, institutions, or policy interventions’ that tame the destabilising forces inherent to capitalism and allow for longer periods of relative stability and growth over several business cycles (Ferri and Minsky 1992, 84). Economic and financial crises do occur during these periods, but thwarting mechanisms contain and prevent them from becoming systemic through countercyclical measures. However, their effectiveness deteriorates over time due to profit-seeking innovations, as laid out in Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis (Minsky 2008), and other, more complex socio-political long-term processes. Once sufficiently eroded, thwarting mechanisms are rendered unable to contain a conventional recession inherent in a business cycle, which then develops into a systemic crisis that can only be overcome by the development and implementation of new thwarting mechanisms and thus profound institutional change. The oscillation in macro-financial stability evoked by this process breeds ‘super-cycles’ that work over longer time frames than ‘basic’ business cycles (Palley 2011).

Dafermos et al. (2023, 3) advance this concept by laying more emphasis on institutional change and periodising ‘institutional super-cycles’ into four phases: First, during expansion, effective new thwarting mechanisms have been introduced and allow for stable economic growth and political conditions without recessions. Second, during maturity, erosion of thwarting mechanisms sets in, with the economy still expanding but macro-financial stability already declining. Third, this eventually leads to a crisis that can only be resolved by, fourth, the genesis of new thwarting mechanisms, which is a highly contingent and complex socio-political process that can fail and prolong crisis periods. Based upon this categorisation, they determine two post-war era super-cycles: First, the industrial capitalism super-cycle, and second, the financial globalisation (FG) super-cycle. Furthermore, to shed more light on the role of stabilising institutions, they differentiated between floor and ceiling thwarting mechanisms. Floor mechanisms aim to ensure a minimum level of aggregate demand (e.g., countercyclical fiscal policy, debt-led growth (Stockhammer 2016)), while ceiling mechanisms set an upper boundary to credit expansion and possible concomitant destabilising effects (e.g., curbing pro-cyclical leverage and financial speculation by means of raising interest rates).

However, the development of a new set of thwarting mechanisms can be contradicting, as ‘policy makers need to […] keep a range of key macroeconomic variables within certain bounds’ to prevent instability, but ‘mechanisms introduced to reduce one source of instability may over time create others, potentially as a result of interaction with other thwarting mechanisms’ (Dafermos et al. 2020, 3–4). This may be amplified by the fact that both the selection of targets for such variables as well as the specific architecture of thwarting mechanisms are influenced and shaped by politico-economic power relations and conflicts (Dafermos, et al. 2023, 3). Thus, the deep social forces underlying ideas, ideology, and perception inherent to critical political economy (Wullweber 2018) are the pivotal driver of an institutional super-cycle, and thwarting mechanisms of the focal point were conflicts and struggles, and also, their outcomes culminate. Financial innovation and the evolution of the regulatory-institutional setup are interdependent and co-constituting (Palley 2011, 38).

Palley (2011, 38–39) referred to the twin developments of increased profit-driven risk-taking activities and ‘regulatory relaxation’ as the two key forces of eroding thwarting mechanisms. The former are driven by factors like financial innovation, data hysteresis, memory loss of past crises, and cultural change. Conversely, regulation can be either captured by vested interests, relapse due to reinterpretation of history and discursive shifts, or simply escaped by financial and legal innovation because it facilitates activities outside the realm conceived by regulation in the first place. This necessitates constant updating of thwarting mechanisms and spawns a dynamic cat-and-mouse game between private profit-seeking actors and public regulators. For Palley (2011, 39), ‘good regulation inevitably sows the seeds of its own destruction by providing incentives to innovate’.

While the ideas of regulatory capture, relapse, and escape are useful to political economy analysis of thwarting mechanisms, recent publications from the discipline disagree with the state-market dichotomy underlying this concept. Instead, they emphasise the complexity of state-market hybridity in contemporary finance (Braun 2020; Wullweber 2020b). Institutional super-cycles should rightly be understood as a post-structuralist meta-process (Palley 2011, 43) in which everybody from profit-seeking actor to regulator and economist gets captivated by his or her own zeitgeist without noticing it. Yet, the pivotal point arising out of this realisation is that these processes are contingent and interdependent, that is, the causality neither runs exclusively from government failure to financial instability and crisis nor from financial innovation and regulatory evasion to crisis. For example, states play a crucial role in establishing financial markets (Helleiner 1995) and maintaining or ‘securing’ financial circulation (Boy 2017), while markets have in turn been constitutive of institutional innovation, too (Gabor 2016b; Braun et al. 2020). This conceptual unclarity about the role of state-market relations in the emergence and demise of thwarting mechanisms is owed to the fact that there has hitherto not yet been sufficient empirical analysis of these processes beyond conceptual considerations.

Going beyond this current state of research, I argue that UMP adds a novel ceiling and floor thwarting mechanism to the macro-financial system, namely in its function as a market-maker of last resort (MMLR) (Mehrling 2011), as well as via its long-term asset purchasing programmes (APPs) in the aftermath of the GFC. This marks a departure from its function as a ceiling and a floor thwarting mechanism during the heyday of the FG super-cycle: As a ceiling, inflation targeting aimed to curb excessive credit creation by the banking system and thus forestall the built-up of speculative bubbles. As a floor, central banks’ lender-of–last resort (LOLR) backstopped debt-led growth by preventing liquidity and thus credit to dry up during crises (Dafermos et al. 2023). UMP also emerged as an institutional innovation in response to shadow banking, that is, ‘money market funding of capital market lending’ (Mehrling et al. 2013, 2), financed by collateral-based liquidity creation via repo markets in which tradable securities are posted as collateral to obtain funds. It is a financial innovation that undermined the FG super-cycle’s ceiling thwarting mechanisms and simultaneously played a crucial role for the floor thwarting mechanism of debt-led growth: By facilitating credit growth outside the regulated banking system targeted by monetary policy, it enabled banks to circumvent caps on liquidity creation and leverage via its system of collateral-based liquidity provision (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009; Adrian and Shin 2010; Gabor 2016b) — and finance consumer-debt expansion (Fernandez and Wigger 2016; Caverzasi et al. 2019).

By drawing on this empirical example, this paper argues that economics and political economy research may profit substantially from the concept of thwarting mechanisms, as it provides a crucial hinge between both disciplines: It enables the analysis of the interplay of the regulatory framework (monetary policy), financial innovation (shadow banking), and its impact on the macro-financial system in a sophisticated yet not deterministic or mechanistic manner. Thus, this paper offers a political economy perspective to better understand the role of power, ideas, and ideology in this process, building on a post-Keynesian conceptualisation of money, finance, and economics while at the same time embedding these phenomena into a political and institutional framework that interacts with the dynamics it entails, balancing structure and agency (Wullweber 2014). Crucially, it also sheds more light on the contradictions of thwarting mechanisms beyond their impacts on macroeconomic variables, which has been the main focus of the work of Dafermos et al. (2023), and instead augments analysis to political economy categories such as ideology, state-market relations, and inequality and the role that institutions themselves play in nurturing or perpetuating certain contradictions.

To this end, the spatiotemporal scope of analysis will be confined to the period starting from the GFC 2008 in advanced capitalist countries, in particular zooming in on the cases of the Federal Reserve (Fed) and European Central Bank (ECB), with sporadic referrals to the Bank of England (BoE).

3 Unconventional monetary policy as a new thwarting mechanism

In 2008, the FG super-cycle entered into a systemic crisis due to an erosion of its major thwarting mechanisms (Dafermos et al. 2023). Inflation targeting through policy-rate setting in unsecured interbank money markets and Basel II regulation mainly focusing on minimum capital requirements of commercial banks were unable to put a cap or ceiling on credit and liquidity expansion. Indeed, the shadow banking system facilitated the circumvention of the stipulations of this regulatory framework (Young 2014), posing an example of regulatory escape. Simultaneously, the floor thwarting mechanism of debt-led growth that drove the economic expansion during the preceding decades by increasing leverage and facilitating debt via shadow banking ceased to function (Fernandez and Wigger 2016; Stockhammer and Wildauer 2016), illustrated by the collapse of securitisation of consumer debt and its refinancing in wholesale money markets (Lysandrou and Nesvetailova 2015).

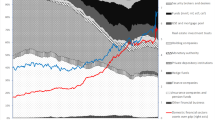

Following this crisis, the FG super-cycle entered into its genesis phase in search of new thwarting mechanisms, spearheaded by central banks’ crisis innovations in what would become known as ‘unconventional monetary policy’ (Bowdler and Radia 2012). Although looking the same at first sight, the immediate asset purchases in the wake of the GFC underlay a different logic than the subsequent long-term purchases that became prominent as quantitative easing (QE). While the short-term aim of the former was to forestall systemic collapse and set policy rates (MMLR), long-term asset purchasing programmes (APPs) intended to reinvigorate the transmission of monetary policy rates and encourage portfolio rebalancing to stimulate economic growth (Gabor 2021). Figure 1 shows the extent of aggregate asset purchases of major central banks from 2008 onwards.

To understand the rationale underlying MMLR, it is crucial to consider the collateral-based character of the shadow banking system. Its emergence was facilitated by the expanding use of repurchase agreements (repos) for liquidity creation in money markets from the 1970s onwards that rendered them new systemic liabilities which de facto fulfil the role of money proper (i.e., reserves) for the overall system, including traditional commercial banks (Gabor and Vestergaard 2016; Murau 2017; Wullweber 2021a). Since this role essentially hinges on market liquidity of underlying collateral assets — preponderantly government securities — permanent central bank intervention and backstops are needed to stabilise the financial system by ensuring repo collateral liquidity (Wullweber 2021b).

During the GFC, central banks acting as a MMLR aimed to ensure liquidity in collateral markets that underlie repo transactions by buying and selling securities according to market needs because private market-makers such as securities dealers withdrew from those markets (Mehrling 2011). However, during a crisis, MMLR mainly amounts to buying up securities to put a ‘lower bound’ under the price of safe assets that serve as collateral in overnight repo markets (Mehrling et al. 2013, 10). During the GFC, the Fed did so by effectively ‘moving the wholesale money market onto its own balance sheet’ (Mehrling 2011, 125). This scenario largely repeated itself during the Covid-19 financial crisis, with the Fed providing credit directly to shadow banks and the overnight repo market being backstopped by repo and reverse repo facilities (Wullweber 2020b), the latter of which provided ‘an important release valve for rapidly rising money market fund (MMF) cash balances amid the surge in demand for safe investment opportunities’ (BIS 2020). The BoE, the ECB, and many other major central banks too acted as MMLR in repo markets during the GFC and its aftermath (BIS 2014). Thus, crisis-driven MMLR augmented LOLR as a key floor thwarting mechanism.Footnote 1

However, there also exists an outside-crisis dimension to MMLR that aims to stabilise repo rates by supporting collateral values and absorbing excess liquidity. Central banks now assume a constant background role in repo markets through which ‘market liquidity is sustained every day because funding liquidity is elastically forthcoming in this way’ (Mehrling 2011, 104). The fact that MMLR is a permanently necessary new feature of UMP was soon acknowledged or at least acted upon by major central banks (Gabor 2016b). In 2013, the Fed established a permanent Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement Facility (ON RRP) in addition to its open market operations (OMOs) through which it provides liquidity through repos by offering collateral against reserves and vice versa (Pozsar 2015). In 2015, the BoE went one step further by officially formalising its MMLR operations, and although the ECB has not done so, its outright monetary transactions ‘are in effect a market-making commitment to collateral market liquidity that supports safe asset status for periphery sovereign bonds and the moneyness of shadow euros [repo liabilities]’ (Gabor and Vestergaard 2018, 24). One additional feature of outside-crisis MMLR is its encompassment of asset-backed securities (ABS) into its collateral framework to stimulate demand for underlying loans in order to revive pre-GFC securitisation (Gabor and Vestergaard 2018). For instance, the ECB became the sole absorber of ABS in the immediate post-GFC period (Gonzalez 2014), encouraging banks to switch from a ‘originate-to-distribute’ to some sort of ‘originate-to-repo’ model (González-Páramo 2010).

Through this constant MMLR backstop, central banks can react to cyclical shifts in liquidity needs, e.g., at quarter and year ends when taxes are levied or regulatory provisions checked, typically causing spikes in OMO and ON RRP usage (BIS 2020; for ECB, see also BIS 2019). Furthermore, they determine the (minimum) level of interest and haircuts on repos and thereby set a certain floor for overnight interest rates in repo markets, pretty much as they do with reserves for commercial banks (Murau 2017). In an inflationary environment, this would accordingly amount to raising repo rates and thus tightening credit conditions in repo markets. Thereby, central banks set a bid-ask spread with signalling function for the entire financial market — market players are allowed to trade freely within a certain bandwidth set by central banks’ MMLR facilities (Wullweber 2020a). Hence, central banks essentially implement short-term policy rate setting in overnight repo markets and thereby also provide a ceiling thwarting mechanism to the macro-financial system.

By contrast, long-term APPs occur out of a different rationale: Both the BoE in 2011 and the ECB in 2015 justified APPs as being necessary to fulfil their mandates via inflation targeting (BIS 2019). These asset purchases are ‘macro-driven’ because they seek to ‘anchor inflationary expectations by reinforcing the signalling role of central banks’ interest rates’ (Gabor 2021, 6), complementing conventional monetary policy in achieving price stability and economic growth. While MMLR operates primarily in money markets, APPs focus on capital markets and involve purchasing securities from institutional investors to affect (lower) long-term asset prices and interest rates (Bowdler and Radia 2012). They aim to push shadow banks — institutional investors, securities dealers, and hedge funds alike — into riskier capital market asset classes. Besides spurring business investment, lowering interest rates on mortgage, auto, and other loans backing ABS eases credit conditions for consumer financing and is seen as an additional boost to demand and inflation (Palley 2015, 26–28). For example, the ECB supported securitisation markets through APPs via its asset-backed securities purchase programme (ABSPP) set up in 2014 (Bindseil 2015). However, ‘[i]n practice, neither investors nor central banks have a clear understanding of how these [transmission] channels work’ (Gabor 2021, 10). Nevertheless, APPs can be considered a major attempt of establishing a floor thwarting mechanism in the post-GFC genesis phase by ways of technocratic puzzling and silent politics (Murau and Giordano 2023).

But APPs came with some unintended side effects. On the money-market side of the shadow banking system, risk-averse investors place their windfall funds in repo markets and thereby increase liquidity in the overall financial system, easing credit conditions further. Consequently, ‘volumes in non-interbank money market segments have remained relatively robust’ since the inception of APPs, while interbank money market trading almost came to a standstill in the wake of abundant excess reserves brought into the system by APPs (BIS 2019, 25–27). Thus, by precipitating an abundance of reserves in the banking system, the new thwarting mechanism of UMP contradictorily undermined the former floor thwarting mechanism of LOLR, consistent with the theoretical propositions about the potentially contradicting contingency of thwarting mechanisms. Table 1 summarises the three dimensions in which UMP acts as a novel thwarting mechanism to the post-GFC macro-financial system in comparison to its pre-GFC configuration.

However, this is not the only contradiction this new monetary policy regime is ridden with. Buying up sovereign and quasi-sovereign bonds reduces the availability of safe assets that serve as high-quality collateral in repo markets and may indeed create a shortage of high-quality collateral (Schlepper et al. 2020). Hence, central banks ‘have to walk a fine line between protecting [repo] convertibility and creating base asset shortages’ (Gabor and Vestergaard 2016, 29). Although they argue that APPs do not cause such shortages because they effectively swap one safe asset for another (government bonds for reserves) (Potter and Smets 2019), this only holds true for commercial banks, while a wide range of actors in the shadow banking system, including securities dealers and institutional investors, are left out (Gabor and Vestergaard 2018). Even if privately crafted pseudo high-quality collateral based upon securitised loans achieves to fill the gap, this would decrease liquidity in the overall financial system due to higher haircuts and repo rates. Hence, safe asset shortages are considered to have a contractionary macroeconomic impact with lower output levels in the productive economy (Caballero et al. 2017, 32–36).

This point illustrates that the contradictions of thwarting mechanisms may well go beyond causing macro-financial instability and changing the corresponding institutional architecture but rather affect the overall political economy and with-it power, class, and state-market relations, as suggested by Palley (2011). Since the very design of UMP is shaped by prevalent power constellation of financial dominance in society (Palley 2014), its potential as a thwarting mechanism in the current genesis phase is curtailed substantially by reflecting the interests of finance. As will be argued hereinafter, central banks’ asset purchases had a negative impact on aggregate demand and thus failed to restore growth and the macro-financial stability needed for a renewed expansion of the macro-financial system and, thus, a new super-cycle.

4 The political economy of unconventional monetary policy and financial dominance

Out of the three reasons why UMP as a thwarting mechanism failed to restore economic growth in the post-crisis decade, the first pertains to the evolution, development, and effectiveness of new thwarting mechanisms. Power relations in society are mediated through regulatory capture, evasion, relapse, and discursive battles that may either bring about ideological shifts or rather perpetuate the status quo.

After a decade of UMP, major contributions by political economists suggested that altogether, the latter benefitted finance capital disproportionately despite overall economic stagnation (Adkins et al. 2020; Wullweber 2021b; Wansleben 2023). This claim can be further substantiated by considering the political economy that shaped the genesis of this particular thwarting mechanism and its interaction with other attempts to establish new thwarting mechanisms, such as stronger financial regulation. Accordingly, this process was subject to a complex amalgamation of private finance interests (capture), institutional path dependencies and macroprudential predicaments (evasion), and discursive battles over ideological tenets and their implications for regulatory and monetary policymaking (relapse). Together, these three factors contributed to shaping the macro-financial regulatory framework of the post-crisis decade, which first saw a range of legislative and regulatory initiatives but was then largely characterised by setbacks and the perpetuation of the status quo (Tooze 2018). This development, in which central banks played a considerable role too, led them to becoming ‘the only game in town’ (El-Erian 2016), much to the detriment of other potential thwarting mechanisms as well as the effectiveness of UMP to fulfil its floor and ceiling function.

The financial sector and in particular the shadow banking system were successful in employing regulatory capture by either influencing policy initiatives to its own advantage or outrightly blocking them (Hacker and Pierson 2011; Culpepper 2015). Examples include reform proposals such as the financial transaction tax put forth by the EU Commission (Liikanen 2012) or the amendment of the Basel II regulatory framework, which was watered down considerably: after years of intense lobbying efforts, institutional investors managed to escape stricter oversight and capital requirements under Basel III that apply to too-big-to-fail systemic banks (Gabor 2018, 412). What is more, Basel III rendered repos even more systemically important because it explicitly allowed for its minimum capital requirements to be met through repo transactions (Wullweber 2020b, 27). Hence, the major central banks of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision did not only leave the shadow banking system unregulated but rather entrenched its role in the macro-financial setup by strengthening it as an alternative vis-á-vis the traditional banking system for increasing leverage — via repo markets that are backstopped by the thwarting mechanism of a public MMLR. This effectively bestowed shadow banks with a ‘regulatory rent’ (Helgadóttir 2016, 925) because they managed to evade the concessions the state demands from commercial banks in exchange for liquidity risk protection via central banks’ LOLR facilities.

It may be tempting to attribute this regulatory forbearance exclusively to regulatory capture, be it due to a high level of unity and self-organisation within the financial sector (Young and Pagliari 2017), the ensuing deployment of lobbying power ‘with strategic intent’ (Culpepper and Reinke 2014, 430), or the technocratic and de-politicised character of monetary and financial regulatory policy that creates low issue salience typically favouring private business interests (Cullpepper 2010). However, this view understates the structural role of institutional path dependencies and macroprudential predicaments arising out of the very regulatory evasion shadow banking posed in the first place (Hardie and Howarth 2013; Ricks 2016; Murau 2017). Accordingly, technocratic elites in central banks had little choice but to react to the altered structure of the financial system and thus follow the path created by private finance — they are ‘driven by functional necessities’ (Murau 2017, 20). During the GFC, they had the ‘choice’ between either supporting the shadow banking system or refusing to do so and accepting the quite foreseeable dire consequences of inaction (Ricks 2016, 2–5). Hence, ‘[e]ndogenous crisis dynamics directed the political interventions in the crisis, which then […] crucially pre-determined post-crisis regulation’ (Murau 2017, 28). Furthermore, the interstate competition brought about by financial globalisation hampers effective regulatory reform and favours a regulatory race to the bottom (Thiemann 2014) — without the need of self-organisation and promotion of vested interests (Culpepper 2015). Hence, regulatory evasion also crucially shaped the genesis of UMP as a novel thwarting mechanism in the post-crisis period.

These arguments evoke the picture of a state-market dichotomy in this process, with financial sector power ‘encroach[ing] on that of national governments’ (Strange 2010, 3). However, a third and more subtle conjuncture that hampered the evolution of monetary policy as an effective thwarting mechanism has indeed been the conflation of private and public interests that is characteristic of the state-market hybridity in finance (Braun 2020; Wullweber 2020a). Governments and their central banks do not merely regulate but also govern through financial markets, thus aligning their interests with those of private market participants and causing political forbearance that facilitates regulatory relapse. Put differently, becoming part of governance structures confers ‘infrastructural power’ (Braun 2020) to those occupying it. In the case of the political battle over the European financial transaction tax, the governments of France and Germany sided with the European Commission in an effort to tax repos because of their destabilising potential (Gabor 2016a). At the same time, their ministries of finance were worried about negative impacts on sovereign bond market liquidity and borrowing costs (Gabor 2016b), supported by the ECB pointing out that regulating the key market in which they operated as MMLR would yield ‘negative implications for the implementation of monetary policy’ (ECB 2013, 109). Little surprisingly, this position saw strong support from private financial sector (Kalaitzake 2017). The upshot of this simultaneous contradiction and conflation of public and private interests was a ‘resounding victory for the ECB-repo alliance’ (Braun 2020, 405) that led to the suspension of the legislative initiative — a drastic example of regulatory relapse.

It also illustrates the failure to establish a new and potentially effective thwarting mechanism (financial transaction tax) because it stood in conflict with another thwarting mechanism (UMP). Central banks themselves played an active role in safeguarding and entrenching the shadow banking system within the macro-financial system due to their bias for market-based governance that also characterises their UMP approach. This is by no means a coincidence but an essential tenet of the neoliberal paradigm in macroeconomic policy making which financial interest groups promoted decisively from the 1970s onwards during the FG super-cycle, shifting the political discourse and zeitgeist towards laissez-faire market-facilitating regulation (Mirowski and Plehwe 2015). Therefore, the benign stance of policymakers towards the financial sector during and after the GFC is likely to be biased by the fact that those on the governing boards of international financial institutions and central banks belong to the same neoliberal epistemic community as their counterparts in private finance (Tsingou 2015). Expertise in shadow banking and its regulatory agenda is highly concentrated at the BIS, FSB, and the IMF, whose epistemic policy community predominantly draws on staff and research from economics departments of US elite universities and opposes strong political interventions in favour of a ‘bland reformism’ (Ban et al. 2016, 1003–1009). Hence, beyond facilitating regulatory relapse, contemporary ideology also favours certain thwarting mechanisms while rendering others politically unfeasible.

Thus, the relative absence of deviating or contesting proposals for thwarting mechanisms within the post-GFC genesis phase can also be seen as a lack of an alternative to the neoliberal paradigm. Although some proclaimed its demise in the direct aftermath of the GFC (Helleiner 2010), significant change did neither materialise in academic economics (Mirowski and Nik-Khah 2013) nor with respect to power relations in society (Scherrer 2014). However, since this was the very paradigm that had already driven the FG super-cycle into crisis, its genesis phase remained crisis-ridden and contradictious, too. The very design and functioning logic of its key novel thwarting mechanism of UMP is wedding macro-financial governance to the core business of the shadow banking system: The production and collateral-based financing of new asset classes (Prates and Farhi 2015). MMLR provides ‘security structures’ to repo markets by ensuring liquidity on a daily basis (Wullweber 2021a), while APPs support the appreciation of collateral values and thus upward liquidity spirals (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009). Hence, central banks now fulfil the role of macro-financial stewards seeking to safeguard overall macroeconomic stability, having become the sine qua non of (financial) market economy, in a modification of neoliberal capitalism that has been termed ‘central bank capitalism’ (Wullweber 2021b; see Table 1).

Most importantly though, keeping shadow banking balance sheets expanded and operational also perpetuates the structural drivers of financial dominance in society (Gabor 2021). As this section has demonstrated, this has implications for the evolution, development, and effectiveness of new thwarting mechanisms due to power relations being mediated through regulatory capture, evasion, relapse, and discursive battles that may either bring about ideological shifts or rather perpetuate the status quo. Beyond this contradiction, it also suggests that this impairs UMP’s efficacy in providing a ceiling and floor function to the macro-financial system. As former Fed President Jerome Powell puts it, central banks prefer to ‘rather clean up after a bubble than try to prevent one’ (Gabor 2016b, 991), thereby encapsulating the structural drivers of financial instability without putting an effective ceiling. Regarding the floor dimension of the UMP thwarting mechanism, two additional contradictions arise, which will be discussed hereinafter.

5 The continuation of the neoliberal monetary-fiscal policy nexus

The second reason why UMP as a thwarting mechanism failed to restore economic growth in the post-crisis decade concerns the interplay of monetary and fiscal policy which is key in modern macroeconomic management of aggregate demand.

The post-GFC period was characterised by economic stagnation in advanced capitalist economies, with a lack of aggregate demand being adduced as a key reason (Bonizzi and Powell 2020; Palley 2009, 2015; Stockhammer 2015). A classical Keynesian counter-cyclical measure to tackle this problem would be to increase government spending via expansionary fiscal policy (Hein 2016). In OECD countries, government expenditure made up 45% of GDP on average annually between 1995 and 2019 (OECD 2021). Principally, fiscal expansion can either be funded through higher taxation or financed by deficit spending. While the former is a highly important issue deserving more academic attention in times of rampant wealth inequality, the nexus between UMP and fiscal policy in times of shadow banking is equally crucial because ‘in a system of credit claims built on a base asset issued by governments, the distinction between fiscal and monetary dominance becomes increasingly blurred’ (Gabor 2016b, 991). This conjuncture suggests that central banks might indeed engage in monetary financing under the disguise of UMP (especially APPs).

From a super-cycle perspective, this would add a potentially powerful floor function to the UMP thwarting mechanism. Considering the extent of government debt being purchased through central banks’ APPs (see Fig. 2) — in 2020, they purchased up to 75% of all public debt being issued on average (IMF 2020, 2) — it is indeed tempting to infer that UMP effectively marks a return to Keynesian ‘fiscal dominance’ (Blommestein and Turner 2012): the monetisation of sovereign debt by central banks that gave fiscal authorities ample leeway during the post-war era when monetary policy was subordinated and relegated to a facilitating role for fiscal policy. In fact, the ‘monetisation of government debt is no longer a taboo’ (Gabor 2021, 3), as a number of institutions that once were strong advocates of fiscal probity such as the OECD now call for a more active fiscal policy stance to combat economic stagnation and ‘warn governments to rethink constraints on public spending’ (Giles 2021). Correspondingly, ECB President Christine Lagarde frankly stated that balance sheet extensions lead to an ‘inevitable strengthening of the interplay between monetary and fiscal policies’ that ‘works both ways’ (Lagarde 2020). This has led to vehement critique and even the allegation of illegal monetary financing on the part of the ECB (Bateman and Klooster 2023), culminating in a judgment by the German Constitutional Court ruling that ECB’s government bond APP (and thus the Bundesbank’s participation in it) violate EU law because the ECB mandate stipulates that it must not interfere with fiscal policy.

Sovereign debt held by central bank, as per-cent of total government debt. Source: BIS 2019, 16

However, the actual picture is more complicated than these critiques insinuate. First of all, the proclaimed separation between monetary and fiscal policy was always rather an ideal image of the neoliberal paradigm than actual policy practice and never absolute (Klooster and Fontan 2020). While it is true that fiscal authorities across advanced capitalist countries found themselves in an increasingly fierce competition for international investors after the turn towards central bank independence freed the latter from its legal obligation to monetise government debt, fiscal authorities also searched for other ways to ensure steady demand and liquidity in government bond markets. By the late 1990s, ministries of finance began to liberalise their bond and repo markets that predominantly draw on government bonds as collateral, based on the blueprint of the US Treasury market (Gabor 2016b). Repo-market growth was further amplified by the fact that treasuries could now not any longer hold tax revenues in a current account at the central bank but instead had to place their excess cash with banks in repo transactions (Gabor 2016b). However, this change in the macro-financial architecture soon necessitated UMP after 2008 — central banks resumed buying government bonds. Thus, akin to Goethe’s sorcerer’s apprentice, the spirits that central banks summoned by withdrawing from government bond markets and letting national treasuries be subject to market discipline turned against them shortly afterwards, forcing them to intervene in markets anew and thus violate the tenets of their neoliberal spiritual fathers.

Nevertheless, central banks upheld the neoliberal paradigm of central bank independence and thus full discretion over their monetary policy, including government bond purchases. For instance, the ECB was eager to emphasise that ‘there is no systematic relationship between government bond issuance and the amount of bonds that we purchase in the secondary market’, and that, therefore, ‘the disciplinary function of markets has not been lost’ (Schnabel 2020). This can also be seen by the fact that almost all major central banks vindicate their APPs with inflation targeting, not supporting fiscal policy (Bateman and Klooster 2023; Gabor 2021). Far from being one among several equally ranking policy goals, it permeates overall monetary policy, with price stability as primary goal, central bank independence as the optimal institutional arrangement, and short-term interest rate setting as operational target — the ‘holy trinity of the inflation targeting paradigm’ (Braun and Downey 2020). Government bond APPs add a fourth dimension to this trinity but do not alter it substantially because they merely extend the operational target to long-term interest rates, while both the primary goal and the preferred institutional arrangement for monetary policy remain unchanged (Gabor 2021).

Therefore, UMP does not mark a radical paradigm shift in comparison to its precursor and neither a return to fiscal dominance nor a monetary financing regime with subordinated central banks (Bateman and Klooster 2023). Instead, it is an intricate continuation of the neoliberal inflation targeting paradigm augmented by the realisation that central banks must engage in macro-prudential asset purchases to stabilise the shadow banking system (MMLR), and that long-term yields play a critical role for the transmission of monetary policy (APPs): the alleged coordination between monetary and fiscal policy ‘is an optical illusion that masks the macro-financial – rather than fiscal – reasons behind the intervention, and that co-exists with central bank independence and inflation-targeting regimes’ (Gabor 2021, 6). Macro-driven APPs aim to lower long-term yields, potentially raise aggregate demand, and bring inflation rates up to target, not finance fiscal deficits of governments (BoE 2015).

Hence, there is considerable reason to doubt the plausibility of fiscal dominance as alleged motivation for APPs. Even if fiscal expansion was a concomitant of UMP that central banks tacitly accepted, this would have been very much within their interest in an almost deflationary environment. However, this cannot be characterised as fiscal dominance in its Keynesian understanding because the persistence of the neoliberal paradigm effectively prevented governments from utilising the fiscal space provided by APPs in the aftermath of the GFC. Instead, they engaged in austerity policies, which central banks — especially the ECB — endorsed vividly at the time (Drache 2014).

The reason why the ECB nevertheless did ‘whatever it takes’ (Draghi 2012) ever since was rather preventing the exacerbation of a safe asset shortage through a fragmentation of collateral eligibility in European repo markets and thus stabilising the shadow banking system and with it the overall macro-financial system. Rising government bond interest rates can trigger a crisis in repo markets that can quickly affect the entire system and backfire on bond markets, as was the case during the Euro-crisis (Gabor and Ban 2016). This was clearly illustrated once more by ECB President Christine Lagarde’s statement amid the beginning Covid-19 pandemic that the ECB ‘is not there to close spreads’ (Reuters 2020) between different Eurozone member bonds. Promptly, Italian bonds yield rose sharply within just 1 day, widening the spread to German bunds to almost 3%, causing outrage from the pandemic-plagued country. Lagarde pulled back the same day and accepted that the ECB is very well there to close spreads by launching a new €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and extending existing APPs by more than €1 trillion in bond purchases the following week (Claeys 2020).

For fiscal policy, this poses a predicament. Governments need to have full (institutionalised) support of their central bank in backing a fiscal expansion lest borrowing costs surge. Even the European Commission, once too an advocate of austerity, now acknowledges that the current sovereign bond market architecture of the EMU substantially limits the ability of member countries to employ counter-cyclical fiscal policy and sees this as ‘a major explanation behind the severe dent in the recovery in the years 2011–2013’ (European Commission 2017, 13). Hence, the ECB contributed to substantially prolonging the post-GFC recovery period (Bateman and Klooster 2023). This constraint to fiscal expansion is crucial because increased costs of debt service are negatively related to wage shares, implying ‘a redistribution of resources from workers to non-wages’ (Canale and Liotti 2021, 1). This suggests a dilemma for policy makers: Increasing government spending can be a powerful tool to raise consumption demand via multiplier effects, but such a move could lead to the opposite outcome under the inflation targeting regime.

Thus, under UMP, fiscal authorities cannot be reassured that fiscal expansions will be supported by central banks, who determinedly clarify this point: The ECB for example opposes any new institutional framework of coordination between monetary and fiscal policy, preferring absolute discretion in asset purchase operations so that treasuries may further be disciplined by government bond markets (Schnabel 2022). Inflation targeting does not provide an explicit and institutionalised coordination framework between both arms of the state and thus perpetuates the neoliberal separation between monetary and fiscal policy (Gabor 2021), with central bank presidents continuing to uphold the importance of ‘the credibility of the fiscal framework’ (Draghi 2017). Hence, deficit government spending as a floor thwarting mechanism remains seriously impeded under the UMP-fiscal policy nexus of central bank capitalism, keeping treasury balance contracted. Albeit central banks are getting increasingly involved in the financial system, they do so in a market-facilitating rather than disciplining manner (Wullweber 2020a) — and do thus not facilitate counter-cyclical fiscal policy to stabilise aggregate demand.

6 Distributional consequences of unconventional monetary policy

The third reason why UMP as a thwarting mechanism failed to restore economic growth in the post-crisis decade also concerns aggregate demand management but with regard to consumption demand — by far the largest component in standard national accounting conventions. Accordingly, the distributional effects of UMP are key to explain its relative ineffectiveness as a floor thwarting mechanism.

The post-crisis period saw an unprecedented inflation of asset prices. Stock market indices such as, e.g. the S&P 500, experienced the most rapid increase in their history, seeing valuations almost quintupling from approximately 1000 points in 2016 to more than 4800 points by 2022. Stock buybacks played an important role in this unprecedented stock market rally, and ‘[v]irtually all companies that undertook buybacks in a given year also raised funds from investors during the same period, often through a mix of equity and debt’ (Aramonte 2020, 51). Particularly, corporate bonds played a key role, the issuance of which rose to record levels during the past decade, amplified by APPs for corporate bonds during the Covid-19 pandemic (IMF 2021; see Fig. 3). These rising corporate debt levels, in turn, reflected in a threefold increase in holdings by MMFs to US $1.5 trillion (Fed 2019; see Fig. 4), similar to institutional investors in the Euro area (ECB 2021).

Global high-yield corporate bond issuance (in billion US$). Source: IMF 2021, 14

Global corporate bond holdings of MMFs (in billion US$). Source: Fed 2019, 37

By keeping shadow bank balance sheets operational and expanding, UMP played an important supportive role in this process. Cohen et al. (2019) show that the ECB’s APPs have encouraged companies to carry out leveraged stock buybacks. The extremely low borrowing costs in capital markets at the time were precisely part of the rationale behind APPs — inducing shadow bank (institutional investor) portfolio rebalancing towards riskier asset classes such as corporate bonds. Indeed, the world’s 700 largest pension funds increased their holdings of alternative assets (e.g., hedge funds) to more than 25% of their US $13 trillion aggregate portfolio value (IMF 2021). However, beyond encouraging the diversion of already existing money stocks (i.e. wealth) for speculative purposes (Stockhammer 2015), the most important channel through which UMP is likely to have contributed to feeding the post-crisis asset price bubble is via the endogenous creation of money and credit for the mere purpose of financial investment (Sgambati 2019). By buying the key-safe asset underpinning repo-markets on a large scale (government bonds), central banks did not only lower overall interest rates alongside the entire yield curve but also drive-up collateral prices. This fuels the pro-cyclicality of collateral-based credit creation in repo markets, as ‘repo liabilities can grow without bank deposits expanding’ (Gabor and Vestergaard 2016, 20). Hence, the shadow banking system facilitates perpetual asset value growth that may be largely disconnected from underlying fundamentals.

This is illustrated by the circumstance that the post-GFC asset price inflation took place against the backdrop of an almost stagnating economy, with ‘speculation-induced asset growth sidelining the role of productive investment […] in the amassing of wealth’ (Foster et al. 2021, 9). This is but a continuation of a long-term trend. Over the past decades, the stock of global financial assets has substantially exceeded that of capital assets (Gadzinski et al. 2018). Hence, some proposed that the financial sector has become ‘an increasingly autonomous realm’ (van der Zwan 2014, 99) vis-á-vis the productive economy. However, ‘when the goal of credit issuance is not the financing of productive activities, but the creation of financial commodities, the job is likely to be highly noxious for the economy’ (Botta et al. 2020, 30). Economic growth in such rent economies tends to be unequally distributed, increasing wealth and income inequality with potentially curbing effects on aggregate demand (Botta et al. 2019). This suggests another impediment to UMP’s floor function that plays out differently for investment demand and consumption demand.

First, UMP’s easy credit conditions perpetuated and further entrenched the imbalance between financial and productive investment that ‘disinclines productive activity on the part of the firms’ (Toporowski 2000, ii). This financialisation of corporations shifted companies’ focus from retaining and productively investing profits towards downsizing productive capacities and distributing profits to shareholders (Lazonick 2014). It also reflects the rising power of shareholders — e.g. asset managers such as BlackRock — over corporations (Braun 2016; Fichtner et al. 2017). Between 2010 and 2019, US firms distributed US $4 trillion in dividends and US $6 trillion in buybacks, accounting for 1.5% of market capitalisation per year (Aramonte 2020, 49). Stock buybacks have also become prominent because remuneration for CEOs is often tied to stock options, thus incentivising buybacks more than long-term fixed capital investment (Lazonick 2014). Consequently, the last 20 years saw net outflows of capital via public equity markets, challenging the conventional wisdom that firms use equity to finance productive investments in the real economy (Fichtner 2020). Hence, such financial(ised) investments do not fully translate into investment demand, employment, and economic growth.

Second, turning to consumer demand, studies have shown that the shadow banking system systematically redistributes wealth from the bottom to the top of the spectrum (Botta et al. 2020): rentier incomes in OECD countries rose persistently as a share of GDP from the 1960s until the 2000s (Jayadev and Epstein 2019), and the increasingly market-based structure of financial intermediation has been a key factor to increasing wealth and income inequality in these countries ever since (Flaherty 2015). The emergence of the shadow banking system itself can be also understood as an outcome of inequality with ‘an increasingly small core of the global population’ who ‘controls an increasingly large share of incomes and wealth’ (Pozsar 2013, 288). Against this backdrop, the post-GFC decade saw scholarly debates whether UMP — in particular APPs — as such has contributed to increasing wealth and income inequality.

While one camp argued in favour of a rather equalising net outcome in the USA and the Eurozone (Bivens 2015; Ampudia et al. 2018), others suggest a zero-sum effect benefiting middle-class debtors and creditors alike, mainly via house borrowers’ lower mortgage payments vis-á-vis pensioners receiving lower interest on their investments (Engen et al. 2015). However, falling house prices in the immediate aftermath of the GFC limited the ability of many to profit from lower interest rates through cheaper refinancing, as risk premia rose due to depreciated collateral (Beraja et al. 2017). On the other hand, some also argued that APPs were ‘modestly dis-equalizing, despite having some positive impacts on employment and mortgage refinancing’ (Montecino and Epstein 2015, 1) because these equalising effects were swamped by the larger dis-equalising effects of asset price inflation. Accordingly, middle- and upper-income groups profited more from mortgage refinancing than the poor, while increases in bond and stock prices predominantly benefited the top quintile. This is because the upper 10% of US citizens own 88% of stock value, with the top 1% still owning an astonishing 56% (Foster et al. 2021).

However, one fundamental critique of most of these studies is that juxtaposing percentual changes of household income and wealth are flattening out or even reversing the actual picture. For the case of the Eurozone, Fontan et al. (2019) point out to the fallacious character of inequality measurement in relative growth terms, as percentages conceal the absolute changes in wealth accumulation (see Fig. 5). Contradicting the study undertaken by Ampudia et al. (2018), they show that the ECB’s APPs have substantially exacerbated inequality, with the top quintile of the wealth distribution gaining more than the entire four other quintiles combined. Hence, instead of being a tide that lifts all boats, UMP seems to rather benefit those already profiting from the status quo while leaving marginalised groups out. Unsurprisingly, the richest 1% of US Americans were able to capture 58% of total economic growth and increase their incomes by 27% vis-á-vis the 4.3% in income growth of the remaining 99% in the period of 2009–2014 (Saez 2020, 3). In conclusion, these findings suggest that these concomitants of UMP contributed weaken rather than strengthen aggregate demand and thus undermine its floor function.

Relative vs. absolute distributional effects of ECB’s asset purchases. Source: Fontan et al. 2019

The structural aggregate demand gap that used to be filled by the floor thwarting mechanism of debt-led growth regimes during the FG super-cycle (Palley 2009; Stockhammer 2016; Tymoigne 2016) is thus left unaddressed by the new thwarting mechanisms of UMP. Despite central banks’ efforts to revive securitisation markets, the issuance of, e.g. privately securitised products in the USA never recovered to its precrisis levels of US $2.5 trillion, standing at US $0.7 billion (Fed 2021). In the Eurozone, the situation has been similar: the European market for securitisation shrunk by 40% from €1.2 billion to €0.7 billion between 2012 and 2021 (TSI 2023). Hence, without an equivalent increase in aggregate demand, these supply-side-focused monetary policy measures equal ‘pushing on a string’ (Claeys 2020, 10).

Adding political economy to the picture shows that financial dominance after the GFC is more pronounced in a world of ‘asset manager capitalism’ (Braun 2016) embedded in and backstopped by ‘central bank capitalism’ (Wullweber 2021b), nurturing regulatory capture, relapse, and escape and thus also permeating the genesis phase of the FG super-cycle. Hence, it is little surprising that the neoliberal paradigm of inflation targeting in central banking persistently inhibits any configuration of UMP to be coordinated with fiscal policy to serve as a floor thwarting mechanism by enabling aggregate demand management via fiscal expansion. However, in absence of other structural shifts in the macroeconomic order, this constitutes the only likely source of growth for any upcoming super-cycle.

7 Conclusion

This paper aimed to answer why UMP failed to restore sustained economic growth in the post-crisis decade despite unprecedented balance sheet expansions by drawing on the evolutionary macro-finance concept of institutional super-cycles and thwarting mechanisms in particular. By linking demand-side economics to political economy and putting the role of historically contingent institutional development to the centre of analysis, it suggests that this theoretical lens can enhance the understanding of the impacts of UMP onto the macro-financial system. It contributes to the literature by extending the analysis of thwarting mechanisms to the current genesis phase of the FG super-cycle and conceptualising UMP as a novel thwarting mechanism, setting a floor and ceiling for the system. MMLR at least theoretically enables central banks to curb destabilising pro-cyclical liquidity spirals inherent to shadow banking by implementing policy rates in repo markets (ceiling) while at the same time putting a lower bound under the price of collateral assets (floor). APPs aim at reviving debt-led growth by encouraging institutional investor portfolio rebalancing towards riskier asset classes and extending policy rate implementation towards the long end of the yield curve government in bond markets (floor). However, the aims of protecting collateral convertibility while buying up collateral assets may prove contradictious.

Yet, this paper argued that the contradictions of the UMP thwarting mechanism go well beyond that. First, UMP perpetuates the structural drivers of financial dominance in society by entrenching the role of the shadow banking system within the overall macro-financial system. This impacts the evolution and effectiveness of new thwarting mechanisms due to power relations being mediated through regulatory capture, evasion, and relapse. Second, UMP remains within the neoliberal macroeconomic policy paradigm and thus contributes to upholding the imperative of fiscal austerity. Inflation targeting does not provide an explicit and institutionalised coordination framework between monetary and fiscal policy and thus keeps treasury balance sheets contracted. Third, UMP nurtured the exacerbation of wealth and income inequality via asset price inflation and thereby contributed to supress aggregate demand. On the one hand, it incentivises financial(ised) investment rather than productive investment while on the other curbing consumption demand due to wealth redistribution from the bottom to the top.

Hence, while UMP may have been an effective initial crisis response that temporally stabilised the financial system, the paper suggests that it failed as a sole thwarting mechanism for the overall macro-financial system because its contradictions tend to perpetuate prior crisis-driving power imbalances and contribute to weaken aggregate demand and economic growth. Thus, this thwarting mechanism is not able to restore macro-financial stability in the long run and needs to be augmented by other changes in the institutional setup to end the persistent crisis of the FG super-cycle and initiate the expansion of a new super-cycle.

Data availability

N/A.

Notes

Albeit not superseding LOLR entirely, as the containment of the US banking crisis in March 2023 showed (Smith et al. 2023).

References

Adkins L, Cooper M, Konings M (2020) The Asset Economy. John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey

Adrian T, Shin HS (2010) Liquidity and Leverage J Fin Intermed 19:418–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2008.12.002

Ampudia M, Georgarakos D, Slacalek J, Tristani O, Vermeulen P, Violante G (2018) Monetary policy and household inequality. ECB Working Paper 2170. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3223542 Accessed 29 June 2021

Aramonte S (2020) Mind the buybacks, beware of the leverage. BIS Quart Rev. https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2009d.htm Accessed 4 July 2023

Ban C, Seabrooke L, Freitas S (2016) Grey matter in shadow banking: international organizations and expert strategies in global financial governance. Rev Int Polit Econ 23:1001–1033. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1235599

Bank of England (2015) The Bank of England’s Sterling Monetary Framework. Bank of England Red Book. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/freedom-of-information/2016/sterling%20monetary%20framework%20june%202015.pdf Accessed 26 April 2023.

Bateman W, van ‘t Klooster J (2023) The dysfunctional taboo: monetary financing at the Bank of England, the Federal Reserve, and the European Central Bank. Rev Int Polit Econ: 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2023.2205656

Beraja M, Fuster A, Hurst E, Vavra J (2017) Regional heterogeneity and monetary policy. NBER Working Paper 23270. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w23270/revisions/w23270.rev0.pdf Accessed 10 October 2023

Bindseil U (2015) The ECB’s perspective on ABS markets. In: ECB (ed) From Monetary Union to Banking Union, on the way to Capital Markets Union: New opportunities for European integration, ECB Legal Conference, 1–2 September, Frankfurt am Main, pp 15–19. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/frommonetaryuniontobankingunion201512.en.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

BIS (2014) Re-thinking the lender of last resort. BIS Papers 79. Available at: https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap79.pdf . Accessed 9 Oct 2023

BIS (2019) Large Central Bank balance sheets and market functioning. Markets Committee Report 11. https://www.bis.org/publ/mktc11.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

BIS (2020) US dollar funding markets during the Covid-19 crisis-the money market fund turmoil. BIS Bulletin 14. https://www.bis.org/publ/bisbull14.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

Bivens J (2015) Gauging the impact of the Fed on inequality during the Great Recession. Brookings Working Paper 12. https://files.epi.org/2015/quantitative-easing-and-inequality-josh-bivens.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2023

Blommestein HJ, Turner P (2012) Interactions between sovereign debt management and monetary policy under fiscal dominance and financial instability. BIS Papers 651. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2081944. Accessed 31 May 2023

Bonizzi B, Powell J (2020) What causes economic crises? And what can we do about them? Greenwich Papers in Political Economy 27331. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:gpe:wpaper:27331

Botta A et al (2019) Inequality and finance in a rent economy. J Econ Behav & Organ 183:998–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.02.013

Botta A, Caverzasi E, Tori D (2020) The macroeconomics of shadow banking. Macroecon Dyn 24:161–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136510051800041X

Bowdler C, Radia A (2012) Unconventional monetary policy: the assessment. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 28:603–621. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grs037

Boy N (2017) Finance-security: where to go?. Fin & Soc 3:208–215. https://financeandsociety.ed.ac.uk/article/view/2580 Accessed 10 October 2023

Braun B (2016) From performativity to political economy: index investing, ETFs and asset manager capitalism. N Pol Econ 21:257–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2016.1094045

Braun B (2020) Central banking and the infrastructural power of finance: the case of ECB support for repo and securitization markets. Socioecon Rev 18:395–418. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy008

Braun B, Downey L (2020) Against amnesia: re-imagining central banking. Counc on Econ Policies (CEP). http://hdl.handle.net/21.11116/0000-0005-A686-8. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

Braun B, Krampf A, Murau S (2020) Financial globalization as positive integration: monetary technocrats and the Eurodollar market in the 1970s. Rev Int Polit Econ: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1740291

Brunnermeier MK, Pedersen LH (2009) Market liquidity and funding liquidity. Rev Fin Stud 22:2201–2238. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn098

Caballero RJ, Farhi E, Gourinchas P-O (2017) The safe assets shortage conundrum. J Econ Perspect 31:29–46. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.3.29

Calvert Jump R, Stockhammer E (2023) Building blocks of a heterodox business cycle theory. J Post Keynes Econ 46:334–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/01603477.2023.2167093

Canale RR, Liotti G (2021) Controversial effects of public debt on wage share: the case of the eurozone. Appl Econ:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1904122

Caverzasi E, Botta A, Capelli C (2019) Shadow banking and the financial side of financialisation. Camb J Econ 43:1029–1051. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bez020

Claeys G (2020) The European Central Bank in the COVID-19 crisis: whatever it takes, within its mandate. Bruegel Policy Contribution 9. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/european-central-bank-covid-19-crisis-whatever-it-takes-within-its-mandate Accessed 10 October 2023

Cohen L, Gómez-Puig M, Sosvilla-Rivero S (2019) Has the ECB’s monetary policy prompted companies to invest, or pay dividends? Appl Econ 51:4920–4938. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1602715

European Commission (2017) Reflection paper on the deepening of the economic and monetary union. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/reflection-paper-emu_en.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2023 Accessed 10 October 2023

Culpepper PD (2010) Quiet Politics and Business Power: Corporate Control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Culpepper PD (2015) Structural power and political science in the post-crisis era. Bus & Polit 17:391–409. https://doi.org/10.1515/bap-2015-0031

Culpepper PD, Reinke R (2014) Structural power and bank bailouts in the United Kingdom and the United States. Polit & Soc 42:427–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329214547342

Dafermos, Y., Gabor, D. and Michell, J. (2020) ‘Institutional supercycles: an evolutionary macro-finance approach’, Rebuilding Macroeconomics Working Paper No. 15 [online]. Available at: https://yannisdafermosdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2020/12/dafermos-et-al-2020-institutional-supercycles.pdf. Accessed 4 Jan 2024

Dafermos Y, Gabor D, and Michell J (2023) Institutional supercycles: an evolutionary macro-finance approach. N Polit Econ 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2022.2161497

Dobusch L, Kapeller J (2012) Heterodox united vs. mainstream city? Sketching a framework for interested pluralism in economics. J Econ Issues 46:1035–1058. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624460410

Drache D (2014) The European Debt Crisis: Incremental Reform, Austerity and Institutional Failure. Soc Sci Res Netw. https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.2374885

Draghi (2012) Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank at the Global Investment Conference in London, 26 July 2012. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120726.en.html

Draghi M (2017) The interaction between monetary policy and financial stability in the euro area. ECB, 24 May, Madrid. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2017/html/ecb.sp170524_1.en.html#footnote.19. Accessed 30 Apr 2021

ECB (2013) Financial Stability Review. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/fsr/financialstabilityreview201311en.pdf?4af555f0d4cf971eb0efb60474bf6fa0. Accessed 24 May 2023

ECB (2021) Financial Stability Review. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/financial-stability/fsr/html/ecb.fsr202105~757f727fe4.en.html#toc39. Accessed 22 June 2021

Eichengreen B (2015) Secular stagnation: the long view. Am Econ Rev 105:66–70. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151104

El-Erian, MA (2016) The Only Game in Town: Central Banks, Instability and Avoiding the Next Collapse. Random House, New York.

Engen E, Laubach T, Reifschneider D (2015) The macroeconomic effects of the Federal Reserve’s unconventional monetary policies. Finance Econ Discuss Ser 5:1–54. https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2015.005

Fed (2019) Financial Stability Report. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-201905.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2023

Fed (2021) Financial Stability Report. https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/financial-stability-report-20210506.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2023

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2023a) Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Assets: Total Assets: Total Assets (Less Eliminations from Consolidation): Wednesday Level [WALCL], retrieved from FRED, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WALCL. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2023b) Bank of Japan, Bank of Japan: Total Assets for Japan [JPNASSETS], retrieved from FRED, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JPNASSETS. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2023c) European Central Bank, Central Bank Assets for Euro Area (11-19 Countries) [ECBASSETSW], retrieved from FRED, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ECBASSETSW. Accessed 10 Oct 2023

Fernandez R, Wigger A (2016) Lehman Brothers in the Dutch offshore financial centre: the role of shadow banking in increasing leverage and facilitating debt. Econ & Soc 45:407–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2016.1264167

Ferri P, Minsky HP (1992) Market processes and thwarting systems. Struct Chang & Econ Dyn 3:79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/0954-349X(92)90027-4

Fichtner J (2020) The rise of institutional investors. In: Mader P, Mertens D, van der Zwan N (eds) The Routledge international handbook of financialization. Routledge, London, pp 265–275

Fichtner J, Heemskerk EM, Garcia-Bernardo J (2017) Hidden power of the Big Three? Passive index funds, re-concentration of corporate ownership, and new financial risk. Bus & Polit 19:298–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/bap.2017.6

Flaherty E (2015) Top incomes under finance-driven capitalism, 1990–2010: power resources and regulatory orders. Socioecon Rev 13:417–447. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwv011

Fontan C, Dietsch P, Claveau F (2019) Les banques centrales et la justice sociale. Éthique publique 21. https://doi.org/10.4000/ethiquepublique.4856

Foster JB, Jonna RJ, Clark B (2021) The Contagion of Capital. Monthly Review 1–19. https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-072-08-2021-01_1

Gabor D (2016a) A step too far? The European financial transactions tax on shadow banking. J Eur Public Policy 23:925–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1070894

Gabor D (2016b) The (impossible) repo trinity: the political economy of repo markets. Rev Int Polit Econ 23:967–1000. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1207699

Gabor D (2018) Goodbye (Chinese) shadow banking, hello market-based finance. Dev Chang 49:394–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12387

Gabor D, Ban C (2016) Banking on bonds: the new links between states and markets. J Comon Mark Stud 54:617–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12309

Gabor D, Vestergaard J (2018) Chasing unicorns: the European single safe asset project. Compet & Chang 22:139–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529418759638

Gabor D, Vestergaard J (2016) Towards a theory of shadow money. INET Working Paper. https://www.ineteconomics.org/research/research-papers/towards-a-theory-of-shadow-money Accessed 10 October 2023

Gabor D (2021) Revolution without revolutionaries: interrogating the return of monetary financing. transformative reponses to the crisis. https://dyrehaugen.github.io/rcap/pdf/Gabor_2021_Revolution.pdf Accessed 10 October 2023

Gadzinski G, Schuller M, Vacchino A (2018) The global capital stock: finding a proxy for the unobservable global market portfolio. J Portf Manag 44:12–23. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.2018.44.7.012

Giles C (2021) OECD warns governments to rethink constraints on public spending. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/economy/oecd-warns-governments-to-rethink-constraints-on-public-spending-1.4449777 Accessed 10 October 2023

Gonzalez F (2014) Transparency in the European loan markets: from words to facts. Z Gesamt Kreditwes 19:32–34. https://www.kreditwesen.de/mimas/system/files/content/articledownloads/2015/09/zf_14_19_954-956.pdf Accessed 21 November 2023

González-Páramo JM (2010) Re-starting securitisation. European Central Bank. 16 June, London. https://www.bis.org/review/r100621f.pdf?sa=U&ei=JsRqU7yxD8jf8AHInIHoAg&ved=0CC4QFjAD&usg=AFQjCNEs2PAj69xF6El5WJ-dyySMTjfsRQ Accessed 10 October 2023