Abstract

This study investigated how schools can contribute to students’ generalized social trust (GST). Positive social experiences with trust and the experience of being part of a fair and predictable social system are important sources of trust. Students’ sense of school membership (SSM) reflects these sources. We investigated the association between three aspects of SSM and GST in 9th grade of Dutch secondary schools (78 schools, 230 classrooms, 5167 students). The diversity of the school population, in terms of track and ethnicity, was included as a moderator. All three aspects of SSM appeared to be positively associated with GST. School ethnic diversity strengthened the association between ‘identification and participation’ and GST but weakened the association between ‘peer acceptance’ and GST. This creates an impetus to support all students to experience a sense of school membership and raises the question how students can profit more from the diversity of the school community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the stubborn refusal to accept misanthropic views of humanity, social trust is a source of civic hope. (Flanagan 2003, p. 170).

Social trust refers to our estimate of the trustworthiness of others. Generalized social trust extends that estimate towards unknown others in general. This type of trust provides an important cornerstone to the functioning of societies. Who we believe is to be trusted relates to prosocial behaviour and cooperation and as such can be considered a key civic disposition (Flanagan et al. 2010). But trust does not only affect the direct relationships people have, societies with higher levels of social trust are characterized by better functioning democratic processes, higher levels of economic growth and a more efficient government. This association can work both ways (Uslaner 2002). Taken altogether this creates an incentive to foster and support such a disposition in all citizens. In this study we will look into the role schools can play in this respect, to better understand the conditions that contribute to social trust.

Schools can be considered practice grounds for citizenship, where students’ civic dispositions are shaped through daily interactions with others (Brodie-McKenzie 2020; Lawy and Biesta 2006; Rinnooy Kan et al. 2021). This implies that what is practiced within the school informs students’ dispositions towards, and in, the larger world. Schools provide a context where students can practice community membership and explore how the social contract works for people like them (Flanagan 2003). Moreover, schools can be considered ‘contact prone environments’, where members of the population are likely to be in relatively close contact with each other and share experiences: an important contextual marker for developing trust (Kokkonen et al. 2015). Schools are also typically the first social environment where young citizens have social experiences beyond their own ingroup of family and peers (Flanagan 2003).

The literature identifies two primary sources of trust: the first concerns positive experiences with trust in the context of social relations, and the second concerns the perception of the extent to which the cultural and social structures one is part of are fair and predictable (Huang et al. 2011). For students, schools provide an environment full of social relations. They also represent the wider formal and informal social structure, with teachers and school leaders acting as ‘proximate authority figures’ (Flanagan 2013). In sum, schools potentially harbour both sources of trust. Flanagan et al. (2010) show that schools can primarily contribute to the development of students’ social trust by offering experiences that align with these sources. Examples are: offering a democratic authority structure, in which students are supported and invited to voice their ideas as full members of the (school) community but also through fostering a climate of school solidarity and connectedness, where students feel a shared responsibility for the functioning of the school. In both these situations, students experience being trusted, the trustworthiness of others and being part of a fair social system. In this study we integrate both routes towards trust by looking at students’ sense of school membership and its association with generalized social trust.

Sense of school membership is a multifaceted indicator of the quality of experienced relationships within the school context (Goodenow 1993; Wehlage 1989). It can be defined as the sense of being supported, accepted by, and connected to peers and teachers, within the school and consist of three elements: relationships with ‘the school’ itself in terms of identification and participation, with peers and with teachers (Ye and Wallace 2014). As such it implies the occurrence of experiences that could support the development of generalized social trust: the first route through positive social experiences in relations with peers and teachers and the second route of being part of fair social system through relations with teachers and as part of the school itself.

However, for generalized social trust to develop it is not simply experiences of trust with others that are relevant. Research indicates that experiences with unalike others are specifically relevant for trust to extend beyond one’s own ingroup (Flanagan and Gallay 2008). In this study we therefor include the diversity of the school’s student population in terms of tracks and ethnic background and investigate if this positively moderates the association between sense of school membership and generalized social trust. To conclude, in this study, our main research questions are: Is sense of school membership associated with students’ generalized social trust? And: (How) does the diversity of the school community influence this association?

Theoretical Framework

Adolescents, Schools and Social Trust

There are different types of social trust – interpersonal social trust, outgroup trust, ingroup trust and generalized social trust. It is especially generalized social trust that provides an important cornerstone for the functioning of societies, as it is not limited to specific groups – it extends to unknown others in general (Dinesen et al. 2020). As such generalized social trust is argued to provide a vital impetus to address large-N collective action dilemmas (Sønderskov 2009). Researchers from a broad array of disciplines, from economics to developmental psychology, have pondered over the question under what conditions generalized social trust develops in individuals. One of the debates within this context is the question if trust is a personality trait that, once developed in early childhood, remains relatively stable (e.g. Uslaner 2002) or a dynamic and developing disposition, achieved through generalizing from past social experiences from different domains such as the family, friends and neighbours (e.g. Glanville and Paxton 2007). Although the sources of generalized social trust are still not completely undisputed (Rothstein 2013; Schilke et al. 2021), it seems that positive social experiences and informal social ties do contribute to it (Paxton and Glanville 2015; Stolle 2001). Adolescence is a crucial period for the development of social trust, as research indicates that it fluctuates a lot less after that period (Abdelzadeh and Lundberg 2017). Moreover, adolescence is rich in formative experiences concerning one’s identity and relations to others (Flanagan and Stout 2010). Consequently, secondary schools hold the potential of positively contributing to the development of social trust as they cater to the right age group. Therefore, the high-school years are crucial when it comes to developing trust. Finally, research indicates that the positive implications of social trust also apply to this age group: youth who trust others are more likely to participate in political volunteerism, community service and voting (Kelly 2009).

However, debate remains around what specific type of interactions where, when and with whom will actually generalize to a sense of trust in unknown others. It has been argued that the context of family and friends is insufficient to fully explain the development of generalized social trust (Flanagan and Stout 2010). Positive social experiences with ingroup members might only contribute to trusting those that share ingroup characteristics (Flanagan et al. 2014). This reasoning provides a second impetus, besides the age of the students, to focus on the school environment for the development of social trust as in general schools provide a more diverse social context than that of adolescents’ close friends and family.

Besides the relevance of positive, trusting, relationships and experiences with others, alike and unalike, the experienced informal and formal functioning of social structures additionally plays an important role when the trustworthiness of generalized others is assessed. The extent to which the system is experienced as fair and predictable is relevant for generalized social trust (Huang et al. 2011). From a psychological point of view these qualities are understood to function as a protective factor. Trusting unknown others is always to a certain extent courageous, there is a level of risk involved as this trust could prove to be unwarranted. The extent to which it is safe to do so is related to one’s perception of the larger social and cultural structures one is a part of. If these formal and informal structures are considered to be fair and predictable this lowers the risk involved in trusting unknown others. This holds true for perceptions of the functioning of social, economic and legal systems and how these affect people ‘like you’ (Zak and Knack 2001; Graafland and Lous 2018). Research indicates that for example the level of objective and subjective corruption by politicians influences the generalized social trust of their constituents (Richey 2010). Additionally, when authorities, as representatives of a social and political system, model trusting behaviour, this might stimulate those who are part of that social system to be trusting themselves. For students, schools represent the social, political and cultural system. In this context teachers can be considered ‘proximate authority figures’, representing authority in a more general sense (Flanagan 2013). Research by Bruch and Soss (2018) illustrates this as students’ experience of their teachers’ fairness is mirrored in students’ dispositions towards the fairness of the political system.

Sense of School Membership and Social Trust

Sense of school membership can be defined as the sense of feeling connected to your school and feeling accepted, included and supported by members of the school community. The concept has been used in research into a broad array of motivational and academic student outcomes (Goodenow 1993; Ye and Wallace 2014). Initially it was used to better understand school dropout (Wehlage 1989), but over the years it has been related to academic (e.g. Adelabu 2007; Sánchez et al. 2005) as well as non-academic outcomes, such a resilience and leadership (e.g. Kapoor and Tomar 2016). The relevance of sense of school membership is mainly understood through its ability to fulfil the primary human need to belong (Baumeister and Leary 1995). A sense of school membership also fulfils important contextual criteria for experiences relevant to the development of generalized social trust, both in terms of social experiences with others as well as experiences with the functioning of the cultural and social system. A sense of school membership implies experiencing relations within the school context where one is accepted, included, and supported (Flanagan and Stout 2010). For example, a case study on immigrant youth shows that specifically their school environment provided opportunities to develop social trust through their experience of school membership. Their school membership was fostered by caring and supportive relationships with their peers but also specifically with their teachers, who considered their bi-cultural background as civic assets and encouraged group work in heterogeneous groups, to underline the added value of differing (Keegan 2017). This illustrates the dual role of the school, not only as an environment where one can experience trusting relations, but also an environment where one can experience being a member of a social institution that not only supports and accepts you, but treats you fairly. Consequently, a sense of school membership alludes to the presence of both sources of trust in the school context; positive individual social relations and the experience of a fair social system.

To get more insight in students’ sense of school membership generally (a part of) the “Sense of School Membership” scale (Goodenow 1993) is used (see for a review: Korpershoek et al. 2020). As sense of school membership is a multidimensional concept it is not surprising that researchers have found that it includes several separate factors (You et al. 2011; Ye and Wallace 2014): (1) identification with and participation in the school community, (2) perception of being accepted by peers within the school and (3) connection to adults within the school community. The first factor ‘identification with and participation in the school community’ refers to feeling connected to and participating in a community or a social system. The second factor of being accepted by peers, relates to the experience of positive social relations within the school context. Finally, the ‘connection to adults’ factor, refers to both the experience of positive social relations and experiencing the fairness of the social system students are part of through teachers as ‘proximate authority figures’. In line with the above, we hypothesize ‘sense of school membership’ is positively associated with generalized social trust. More specifically, we hypothesize that identification with and participation in the school community (a), perception of being accepted by peers (b) and connection to adults within the school community (c) are all positively associated with generalized social trust (Hypotheses 1a, 1b and 1c).

The Role of Diversity within the School Community

While intergroup contact potentially plays an important role when it comes to developing a version of trust that also includes trust towards outgroup members, not all intergroup contact leads to more trust. Intergroup contact can also result in the experience of intergroup threat and conflict. This is illustrated by a broad array of research on the relationship between the diversity of a community and the levels of trust of its members, that shows that there are also instances where more diversity is connected to lower levels of trust (see for a review: Dinesen et al. 2020).

Certain preconditions seem specifically relevant for generalized social trust to materialize in diverse settings. The argument underlying the positive influence of diversity on trust, is that in more diverse communities higher levels of trust towards outgroup members arise from more intergroup contact, along the lines of the contact hypothesis (Allport 1954; Gundelach 2014; Pettigrew 1998). One of the ways to overcome the possible intergroup threat associated with diversity, is through the ‘common ingroup identity model’, which simply put, stipulates that it is possible to recategorize different groups into one more inclusive superordinate group (Gaertner et al. 1993). Such identification with a superordinate group (such as a school community), rather than with a smaller subgroup (such as an ethnic group in a diverse school), promotes more positive attitudes between subgroups within that context (see e.g. Riek et al. 2010).

The positive association between shared membership, diversity and trust is also present in research by Burrmann et al. (2020) that shows that volunteers in more socially diverse associations show higher levels of generalized social trust than volunteers in more homogeneous associations. And, more specifically for adolescents, participating in community service where interactions with members who differ from the participants in terms of socio-economic status as well as ethnic background seems not only to diminish outgroup prejudice but also to increase generalized social trust (Flanagan et al. 2014). Specifically for the context of education a recent study by Österman (2021) showed that educational reforms in Europe that decreased or belated tracking were also (moderately) positively related to increased social trust in students. Although tracking, or ability grouping, refers to the process of grouping students along the lines of their academic performance, there is a strong correlation with socio-econmic status of students, i.e. students with lower socio-economic status are overrepresented in lower or vocational tracks and students with higher socio-economic status are overrepresented in higher or pre-academic tracks (e.g. Batruch et al. 2019). The underlying mechanism of a positive effect of delayed tracking on students’ social trust may thus be that these reforms created more socio-economically diverse classrooms and as such a longer period of contact between students with different backgrounds. When school membership is experienced in a diverse environment, we contend that its association with generalized social trust is strengthened in comparison to experiencing a sense of school membership in a more homogenous environment. Being a member of a school community could serve at the purpose of a common ingroup identity. In a homogenous setting this means identifying with similar others. In a heterogenous setting this implies identification with dissimilar others as well. Consequently, positive relations with ‘former’ outgroup members are invited, which strengthens support for the development of generalized social trust in line with the first source of trust. But a more diverse environment could reinforce the strength of both sources of trust. For the second source of trust the experience with authority within the school is key, as this source refers to being a member of a fair and predictable social system. If school’s authorities, teachers and school leaders, treat people like you fairly in the presence of diverse others this represents a social system in which intergroup threat is minimalized. This is in line with the group-value model, that stipulates that being treated fairly by authority confirms your own group status (Urbanska et al. 2019). In line with what the above described research shows, we include diversity of the school population in terms of tracks as well as ethnic diversity as moderators (Flanagan et al. 2014; Österman 2021). To conclude, we hypothesize that the association between students’ sense of school membership and their generalized social trust will be positively moderated by the presence of different tracks (Hypothesis 2a) and school ethnic diversity (Hypothesis 2b).

Method

Participants

Data comes from the Understanding the Effects of Schools on students’ Citizenship Project, which was conducted in 2016 (see Coopmans et al. 2020). This project in Dutch secondary schools investigates citizenship education and citizenship competences of 9th grade students. In the Dutch school system, this is the third grade of secondary school when students are aged 13–15. In total, 81 schools participated in this study, with on average three classrooms per school. In the Netherlands students generally are grouped in tracks on entering secondary school (11/12 year olds or 7th grade). If different tracks were present within the school they were represented in the sample of classrooms. This resulted in 240 participating classrooms and 5,297 students. Additionally, their mentors, twelve other teachers and one principal were invited to participate in the study. For the current study, only student data was used.

Procedure

Two different routes were used to recruit participating schools. The first route was a random sampling procedure (n = 52). A second route using the research team members’ network was added to increase statistical power (n = 30). One of the schools ceased participation at the initial stage for unknown reasons. Subsequently, three third grade classrooms were randomly selected per school. If applicable, classrooms representing the different educational tracks present within the school were included. Under the supervision of a trained test leader students filled in two questionnaires during two regular classes. In the first questionnaire students were mainly asked about their background and perception of their school’s characteristics. The second questionnaire contained question about their citizenship competences and citizenship education in their school (Ten Dam et al. 2011). For the purpose of this study only questions from the first questionnaire were used. The parents of the students were informed about the study and could deny consent for their children to participate. Students were also informed about the study, confidentiality and the voluntary nature of their participation.

Analysis Sample

For the current study, three schools were excluded from the analyses sample. Two schools shared a location and it was unclear in what school students were enrolled. Furthermore, one of the schools was a school for special needs education (see for the procedure Coopmans et al. 2020). Additionally, two classrooms were excluded as less than five of their students participated in the study (i.e., one and four students), these responses cannot represent classroom level constructs, like classroom diversity. The resulting analysis sample consists of 78 schools, 230 classrooms and 5167 students. Students were on average 14 years old, 51,6% was female. Students were part of classrooms from different educational tracks: 43,5% preparatory secondary vocational education (in Dutch: vmbo), 23,2% general secondary education (in Dutch: havo), 25,7% pre-university education (in Dutch: vwo), mixed general and academic (6,7%), and mixed vocational, general and academic (0,9%) educational track.

Measures

Dependent Variable: Generalized Social Trust

The dependent variable of this study is generalized social trust at the individual level. The measure of social trust is based on a question item included in all four waves of World Values Survey (World Values Survey (n.d.): “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” This measure, or similarly worded questions, are commonly used as a standard measure of generalized trust (cf. Nannestad 2008). In this study students indicated on a scale from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’ to what extent they agreed with the statement “Generally speaking most people can be trusted”. This single item with ordinal answering categories is the dependent variable of this study.

Main Independent Variables: Sense of School Membership

Three aspects of school membership were measured using the validated ‘Psychological Sense of School Membership’ (PSSM) measure of Ye and Wallace (2014), who adapted the original PSSM measure (Goodenow 1993) resulting in three substantive factors and related subscales. Students indicated for 14 items to what extent the statement applied to them on a scale from 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’. Negatively phrased items were reverse coded. The first subscale, Identification and Participation, was measured by six statements forming a reliable scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.724). An example item was:”I really feel part of this school”. The second subscale, Peer acceptance, consisted of five items (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.724). Example item: “It’s hard for people like me to be accepted here” (reversed). The third subscale, teacher connectedness, with three items formed an acceptable scale alpha = 0.656. Example items: “The teachers here respect me” and “Teachers here are not interested in people like me” (reversed). Factor analyses (Principal Component with Varimax Rotation) showed that the three subscales of school membership could be distinguished with factor loadings higher than 0.50, except for the negatively stated items. Nonetheless negatively stated items were left in the scale because they did contribute to the reliability of the scale and because of the theoretical and substantive fit with the scale. A higher score on the scale indicates higher sense of membership.

School Level Variables

Ethnic Diversity

Based on the migration background of the students (see how this was coded below under individual control variables) within each school, the Simpson (1949) ethnic diversity index (also known as the reversed Herfindahl index) was calculated. The resulting index represents the chance that two students picked at random would have the same background, which ranged from 0.02 to 0.84 (mean = 0.33, SD = 0.22).

Track Diversity

Based on educational tracks of the classrooms in this study (see below), schools with only one type of track were coded as being 0, a categorical school (50%). Schools with more than one track, were coded as 1, a mixed school (50%).

Classroom Level Control Variable

Educational track

is included as a classroom level control variable. Students reported whether they attended the (0) vocational track or the (1) general/academic educational track. Because there were only two mixed vocational-academic track classrooms, these were not included in the analyses (coded as missing).

Individual Level Control Variables

Gender

was measured by self-report and coded as 0, male, and 1, female.

Migration background

was computed based on countries of birth of both parents. Following Statistics Netherlands (n.d.), when at least one of the parents was born outside the Netherlands, the student was considered as having a specific migration background (24%). For the analyses, this was dummy-coded as 0, no migration background, and 1, migration background.

Analytical Strategy

Hypotheses were tested by three-level regression models (in Mplus: Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2018) to account for the nested structure of the data (students in classrooms within schools). A three-level model with ordered categorical outcome variable (trust) can be estimated Bayesian in Mplus. All continuous variables (i.e., the sense of school membership scales and school diversity index) were z-standardized before model estimation. The stepwise procedure was followed to build the model. The first model included the individual and classroom level control variables in Model 0. Next, the main effects of the three sense of school membership aspects were added in Model 1. Next, diversity indices (ethnic diversity and track diversity) were added in Model 2. Next random effects were included for the relations between school membership (3 indicators) and social trust. Because the variance of these slopes was significant, interactions were added to the following Models 3 and 4. The first three models had good model fit (Fit Index of approx. 0.50). For the latter models including random slopes, fit indices and explained variance is not available in Mplus. Robustness of the models was determined by similar results when estimating the model with 2000 and 4000 iterations.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for all individual level variables in this study. Regarding the independent variables, the three aspects of sense of school membership, preliminary analyses show that students in general report higher peer acceptance than identification and participation (paired sample t-test: t(5158) = 25.396, p < 0.001), more peer acceptance than teacher connectedness (paired sample t-test: t(5158) = 14.133, p < 0.001), and more identification and participation than teacher connectedness (paired sample t-test: t(5158) = 6.352, p < 0.001). Furthermore, regarding the dependent variable, 20.1 percent of the students disagreed with the statement that in general most people can be trusted, 47.7 percent of the students agreed, and 32.2 percent indicated to be neutral.

Bivariate correlations between all variables are presented in Table 2. These correlations show that the three independent variables, the three sense of school membership subscales, are related, but not higher than 0.60. Which allows including the combination of these variables in one model. Regarding the hypothesized relations, the correlations indicate that, all three aspects of sense of school membership, and also the diversity markers (ethnic diversity and track diversity) are related to generalized trust. These relations will be examined in the main analyses, which takes the nested nature of the data into account and includes possible confounders.

Main Analyses

The main analyses are presented in Table 3. Model 0 included the baseline difference of possible confounders, indicating that girls (B = -0.142, p < 0.001), students with a migration background (B = -0.331, p < 0.001), and students in the vocational track (BTheoretical = 0.166, p < 0.001), reported less generalized trust, than their counterparts. Next, Model 1 introduced the three sense of school membership subscales. The results show that all three aspects of school membership are related to higher generalized trust. This relation remains robust in the following models. Hence, this clearly supports Hypotheses 1 a, b, and c.

Model 1 added the main effects of school diversity, measured by track diversity, whether a school offered multiple tracks (mixed) or not (categorical), and by ethnic diversity. Track diversity was not significantly related to students’ social trust. School ethnic diversity was negatively related to students’ social trust (B = -0.049, p < 0.05).

Cross-level interaction effects were added in the next models, to test whether the relation between sense of school membership (i.e., the three subscales) and students’ generalized trust was moderated by school diversity. Findings of Model 3 show, in contrast to Hypothesis 2a, that the relation between sense of school membership and students’ sense of trust was not moderated by track diversity.

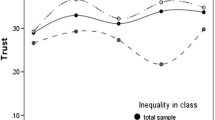

Findings of Model 4 show that the moderation by school ethnic diversity is significant and positive for the association between identification & participation and generalized social trust (B = 0.049, p < 0.05). This means that in schools with a more ethnically diverse student population, students’ identification with and participation at school is more strongly related to students’ generalized trust. This is in line with our hypothesis (2b). In contrast, the moderation was significant and negative for the association between peer acceptance and trust (B = -0.046, p < 0.05). That is, the positive relation between peer acceptance and trust is (still positive but) less strong in schools that are characterized by a more ethnically diverse student body. A similar negative trend was shown for teacher connectedness, but this negative moderation was only marginally significant (B = -0.032, p = 0.053). In sum, these findings do not support Hypothesis 2a on the moderation by track diversity, and partially support Hypothesis 2b on the moderation by school ethnic diversity.

Discussion and Conclusion

Generalized social trust can be considered an important civic disposition that strengthens the social fabric of societies. In this study we looked into the role of schools in sustaining and supporting generalized social trust, to better understand the conditions that contribute to it. More specifically, we looked at how different aspects of students’ sense of school membership are associated with their generalized social trust and how the diversity of their school community affects this association. The current study shows that all three aspects of sense of school membership, (1) identification and participation, (2) peer acceptance, and (3) teacher connectedness, are positively related to students’ generalized social trust, as we hypothesized. School ethnic diversity appeared to affect this association in different ways: it strengthens the relation between identification and generalized social trust, but weakens the relation between peer acceptance and generalized social trust.

We understand schools to be practice grounds for citizenship: to be an environment where students can practice and experience community membership (Flanagan 2013; Rinnooy Kan et al. 2021; Veugelers 2011). The findings of this study illustrate the relevance of that approach – what students experience in terms of belonging, being trusted, included and treated fairly in school feeds into their outlook on the world around them.

Our findings concerning the moderating role of diversity in school were, however, only partially in line with our expectations. The positive association between all three aspects of sense of school membership and generalized social trust was theorized to be strengthened by the diversity of the school in terms of tracks and ethnic background of the students. Our results suggest that ethnic diversity is the most relevant type of diversity here, school’s diversity in terms of track did not affect the relation between sense of school membership and generalized social trust. This might be related to the fact that the presence of different tracks within the school, often still implies separated classrooms along the lines of tracks. Therefore the increase in (positive) outgroup contact could still be minimal in mixed-track schools. Research concerning belated tracking, and mixed classrooms in terms of track, indeed shows a moderate positive effect of these mixed classrooms on generalized social trust (Österman 2021).

Meanwhile, school ethnic diversity moderated the different aspects of sense of school membership in surprisingly different ways. Where it, as hypothesized, did strengthen the association between ‘identification and participation’ and generalized social trust, it weakened the association between peer acceptance and generalized social trust. This last unexpected association might be explained by the fact that in more ethnically diverse contexts, students tend to turn more to their ingroup, along the reasoning of intergroup threat theory (Munniksma et al. 2016). Hence when students report on peer acceptance in school, they may refer to their ingroup peers, particularly in more ethnically diverse schools. Their sense of peer acceptance then would also refer to an acceptance by ingroup members, in turn, affecting their positive outlook towards outgroup members less and as such diminishing the positive association of peer acceptance with generalized social trust.

The unexpected direction of the moderation of ethnic diversity on the association between peer acceptance and generalized social trust also acts as a clear reminder that a diverse school community, even one where individual students experience sense of school membership, is not automatically an integrated and inclusive school community. In terms of integration, research indicates that it is particularly the density of connections within a community that is relevant for generalized social trust (Iacono 2018). The possible retreat into ingroups in more diverse schools also indicates a lower density of connections, which could serve as a further explanation for the negative moderation. In terms of inclusiveness, the so called ‘community diversity debate’ has been a continuing exploration of the functioning of increasingly diverse and complex communities. A key theme within this debate is how to find the right balance between what is shared and what is allowed to remain different (Mannarini and Salvatore 2019; Strike 1999). This tension may play out differently for members of societally marginalized groups, such as those with disabilities, different needs and migration backgrounds, as assimilation towards a shared group norm could contradict their own needs (Black and Burrello 2010).

This is in line with reasoning by Banks and Banks (2019) who, from the perspective of multicultural citizenship theory, assert that students’ attachment to their individual cultural communities should not limit their abilty to be part of a shared (e.g. national) culture. The importance of a dual identity approach, that focusses on what is shared without the expectations of other group identities disappearing is also underlined in the context of the ‘common identity ingroup model’ (Dovidio et al. 2009). One way to preserve identity beyond that of membership to the school community, is through ‘communities of difference’, that place the way they deal with differences at the centre of what is shared (Shields 2000). Research in the workplace confirms that a common ingroup identity is especially effective if it explicitly embraces the value of diversity (Zee et al. 2009). In practice, combining an approach along the lines of multicultural education, for example including knowledge from different (cultural) perspectives, and an egalitarian approach, centered around what students have in common, might be the most effective way to work on this within schools (Banks and Banks 2019; Schwarzenthal et al. 2020). However, both aspects—integration and inclusiveness—ask for more research, especially in terms of how school communities deal with diverse student populations and what best practices can be identified (cf. Rinnooy Kan et al. 2021; Cassidy 2019; Lam et al. 2021).

We identified two possible sources of trust to corroborate for the association between sense of school membership and generalized social trust: positive social experiences around trust (e.g. Glanville and Paxton 2007) as well as membership of a fair and predictable cultural and social systems (e.g. Huang et al. 2011). The three aspects of sense of school membership embody these sources in different ways. The first source of trust is clearly present in both (2) peer acceptance and (3) teacher connectedness, but the second source, of being a member of a fair and predictable system, is less easy to clearly distinguish. It is part of the experience of (3) teacher connectedness and possibly embedded within (1) identification and participation. Additional research is necessary to further explore the role of this source, specifically within the school context. More generally, teachers and school leaders as proximate authority figures play a crucial role in understanding how schools function as practice ground for citizenship, yet research along these lines is currently limited (cf. Bruch and Soss 2018). Research on the more general link between membership to a fair and predictable social system, or experienced procedural fairness, and trust shows that experiences for majority and minority members within the same system differ and that expectations of the fairness of the system towards minority members plays a crucial role in defining those differences (Kongshøj 2018; Urbanska et al. 2019). This provides an impetus to reflect on how authority within the school specifically relates to minority students, as it could influence the experience, and levels of trust, of all students within the school. Furthermore, research indicates that experienced procedural fairness does positively influence minority members’ sense of societal belonging and, in turn, their social trust (Valcke et al. 2020). For future research, a more in depth understanding of experiences with authority in schools, and how they relate and compare to experiences with authority outside of school, will help enrich insight into the civic role of schools and more specifically, will help enrich the understanding of the role schools play in light of students’ generalized social trust.

Our study also has some limitations. Firstly, our cross-sectional data does not allow for causal conclusions, however, research shows support for the influence of social experiences on social trust in contrast to a reverse association (e.g. Glanville and Paxton 2007; Paxton and Glanville 2015). Second, as discussed, context variables on school diversity do not give information on the extent to which the relations between students with different background actually exist, neither on their density or their quality. This is something that could be addressed through social network analysis, which in turn would be especially interesting in combination with qualitative research on best practices for inclusive and integrated school communities. Thirdly, although the single item measure for generalized social trust we used is widely used, research indicates that people might interpret it in different ways (Sturgis and Smith 2010). A more elaborate and nuanced measurement might provide more reliable, and thus comparable, insight in participants generalized social trust (cf. Robbins 2022). Finally, the data we used was collected in 2016 and as such might be somewhat dated: not taking into account recent societal changes. For example, it cannot account for the influence of the COVID19 pandemic that took many students out of school for extended periods of time and might have influenced experienced trust in within school relations (cf. Zorkić et al. 2021). Nevertheless, this influence might also have been temporarily now that schools are generally back to functioning as they were during the time of our data collection.

Research consistently shows the relevance of trusting relationships for the functioning and quality of the school environment (Bryk and Schneider 2002; Tschannen-Moran 2014). This study underlines that their relevance runs far beyond the school’s walls. If we manage to offer students sufficient experiences of trust and being trusted, through the fostering of their sense of membership to the school community, it will support them to trust unknown others. That does not imply encouraging them to naively trust that all others will always have their best interest at heart or undermining the value of their critical capacities. It implies countering the trend of shared mistrust, which hampers societies’ ability to address the big issues we are facing together.

Data Availability

The data used in this study are not yet openly available. For insight in or use of the data used in this study, please contact the corresponding author.

References

Abdelzadeh A, Lundberg E (2017) Solid or flexible? Social trust from early adolescence to young adulthood. Scand Polit Stud 40(2):207–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12080

Adelabu DH (2007) Time perspective and school membership as correlates to academic achievement among African American adolescents. Adolescence 42(167):525–538

Allport G (1954) The nature of prejudice. Basic Books

Banks JA, Banks CAM (eds) (2019) Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives, 10th edn. John Wiley & Sons

Batruch A, Autin F, Bataillard F, Butera F (2019) School selection and the social class divide: How tracking contributes to the reproduction of inequalities. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 45(3):477–490

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Black WR, Burrello LC (2010) Towards the Cultivation of Full Membership in Schools. Values Ethics Educ Adm 9(1):1–8

Brodie-McKenzie A (2020) Empowering students as citizens: Subjectification and civic knowledge in civics and citizenship education. J Appl Youth Stud 3(3):209–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-020-00023-3

Bruch SK, Soss J (2018) Schooling as a formative political experience: Authority relations and the education of citizens. Perspect Polit 16(1):36–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1537592717002195

Bryk A, Schneider B (2002) Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation

Burrmann U, Braun S, Mutz M (2020) In whom do we trust? The level and radius of social trust among sport club members. Int Rev Sociol Sport 55(4):416–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690218811451

Cassidy KJ (2019) Exploring the potential for community where diverse individuals belong. In: Habib S, Ward MR (eds) Identities, youth and belonging. Palgrave Macmillan, pp 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96113-2_9

Coopmans M, Ten Dam G, Dijkstra AB, Van der Veen I (2020) Towards a comprehensive school effectiveness model of citizenship education: An empirical analysis of secondary schools in the Netherlands. Soc Sci 9(9):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9090157

Dinesen PT, Schaeffer M, Sønderskov KM (2020) Ethnic diversity and social trust: A narrative and meta-analytical review. Annu Rev Polit Sci 23:441–465. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-052918-020708

Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, Saguy T (2009) Commonality and the complexity of “we”: Social attitudes and social change. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 13(1):3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868308326751

Flanagan C (2003) Trust, identity, and civic hope. Appl Dev Sci 7(3):165–171. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0703_7

Flanagan C (2013) Teenage citizens: The political theories of the young. Harvard University Press

Flanagan CA, Stout M (2010) Developmental patterns of social trust between early and late adolescence: Age and school climate effects. J Res Adolesc 20(3):748–773. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00658.x

Flanagan C, Stoppa T, Syvertsen AK, Stout M (2010) Schools and social trust. In: Sherrod LR, Torney-Purta J, Flanagan C (eds) Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth. John Wiley & Sons, pp 307–329

Flanagan C, Gill S, Gallay L (2014) Social participation and social trust in adolescence: the importance of heterogeneous encounters. In: Omoto AM (ed) Processes of community change and social action. Psychology Press, pp 149–176

Flanagan C, Gallay L (2008) Adolescent Development of Trust. CIRCLE Working Paper 61. Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE)

Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF, Anastasio PA, Bachman BA, Rust MC (1993) The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 4(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000004

Glanville JL, Paxton P (2007) How do we learn to trust? A confirmatory tetrad analysis of the sources of generalized trust. Soc Psychol Q 70(3):230–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/019027250707000303

Goodenow C (1993) The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: Scale development and educational correlates. Psychol Sch 30(1):79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(199301)30:1<79::aid-pits2310300113>3.0.co;2-x

Graafland J, Lous B (2018) Economic freedom, income inequality and life satisfaction in OECD countries. J Happiness Stud 19(7):2071–2093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9905-7

Gundelach B (2014) In diversity we trust: The positive effect of ethnic diversity on outgroup trust. Polit Behav 36(1):125–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9220-x

Huang J, van den Brink HM, Groot W (2011) College education and social trust: An evidence-based study on the causal mechanisms. Soc Indic Res 104(2):287–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9744-y

Iacono SL (2018) Does community social embeddedness promote generalized trust? An experimental test of the spillover effect. Soc Sci Res 73:126–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.03.001

Kapoor B, Tomar A (2016) Exploring connections between students’ psychological sense of school membership and their resilience, self-efficacy, and leadership skills. Indian J Posit Psychol 7(1):55

Keegan PJ (2017) Belonging, place, and identity: The role of social trust in developing the civic capacities of transnational Dominican youth. High School Journal 100(3):203–222. https://doi.org/10.1353/hsj.2017.0008

Kelly DC (2009) In preparation for adulthood: Exploring civic participation and social trust among young minorities. Youth Soc 40(4):526–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118x08327584

Kokkonen A, Esaiasson P, Gilljam M (2015) Diverse workplaces and interethnic friendship formation—A multilevel comparison across 21 OECD countries. J Ethn Migr Stud 41(2):284–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2014.902300

Kongshøj K (2018) Acculturation and expectations? Investigating differences in generalized trust between non-Western immigrants and ethnic Danes. Nord J Migr Res 8(1):35–46. https://doi.org/10.1515/njmr-2018-0006

Korpershoek H, Canrinus ET, Fokkens-Bruinsma M, de Boer H (2020) The relationships between school belonging and students’ motivational, social-emotional, behavioural, and academic outcomes in secondary education: A meta-analytic review. Res Pap Educ 35(6):641–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1615116

Lam SF, Shum KKM, Chan WWL, Tsoi EWS (2021) Acceptance of outgroup members in schools: Developmental trends and roles of perceived norm of prejudice and teacher support. Br J Educ Psychol 91(2):676–690

Lawy R, Biesta G (2006) Citizenship-as-practice: The educational implications of an inclusive and relational understanding of citizenship. Br J Educ Stud 54(1):34–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00335.x

Mannarini T, Salvatore S (2019) Making sense of ourselves and others: A contribution to the community-diversity debate. Commun Psychol Glob Perspect 5(1):26–37. https://doi.org/10.1285/i24212113v5i1p26

Munniksma A, Scheepers P, Stark TH, Tolsma J (2016) The impact of adolescents’ classroom and neighborhood ethnic diversity on same-and cross-ethnic friendships within classrooms. J Res Adoles 27(1):20–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12248

Nannestad P (2008) What have we learned about generalized trust, if anything? Annu Rev Polit Sci 11:413–436. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135412

Österman M (2021) Can We Trust Education for Fostering Trust? Quasi-experimental Evidence on the Effect of Education and Tracking on Social Trust. Soc Indic Res 154(1):211–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02529-y

Paxton P, Glanville JL (2015) Is trust rigid or malleable? A laboratory experiment. Soc Psychol Q 78(2):194–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272515582177

Pettigrew TF (1998) Intergroup contact theory. Annu Rev Psychol 49(1):65–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

Richey S (2010) The impact of corruption on social trust. Am Politics Res 38(4):676–690. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x09341531

Riek BM, Mania EW, Gaertner SL, McDonald SA, Lamoreaux MJ (2010) Does a common ingroup identity reduce intergroup threat? Group Process Intergroup Relat 13(4):403–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209346701

Rinnooy Kan WF, März V, Volman M, Dijkstra AB (2021) Learning from, through and about differences: A multiple case study on schools as practice grounds for citizenship. Soc Sci 10(6):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10060200

Robbins BG (2022) Measuring generalized trust: Two new approacher. Soc Methods Res 51(1):305–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119852371

Rothstein B (2013) Corruption and social trust: Why the fish rots from the head down. Soc Res 80(4):1009–1032. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2013.0040

Sánchez B, Colón Y, Esparza P (2005) The role of sense of school belonging and gender in the academic adjustment of Latino adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 34(6):619–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8950-4

Schilke O, Reimann M, Cook KS (2021) Trust in social relations. Ann Rev Sociol 47:239–259. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-082120-082850

Schwarzenthal M, Schachner MK, Juang LP, Van De Vijver FJ (2020) Reaping the benefits of cultural diversity: Classroom cultural diversity climate and students’ intercultural competence. Eur J Soc Psychol 50(2):323–346

Shields CM (2000) Learning from difference: Considerations for schools as communities. Curric Inq 30(3):275–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/0362-6784.00166

Simpson EH (1949) Measurement of diversity. Nature 163:688. https://doi.org/10.1038/163688a0

Sønderskov K (2009) Different goods, different effects: Exploring the effects of generalized social trust in large-N collective action. Public Choice 140(1):145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9416-0

Statistics Netherlands (n.d.) Migration background. https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/methods/definitions/migration-background. Accessed 2 Oct 2022

Stolle D (2001) Getting to trust. In: Dekker P, Uslaner EM (eds) Social capital and participation in everyday life. Routledge, New York, pp 118–133

Strike KA (1999) Can schools be communities? The tension between shared values and inclusion. Educ Adm Q 35(1):46–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131619921968464

Sturgis P, Smith P (2010) Assesing the validity of generalized social trust questions: What kind of trust are we measuring? Int J Public Opin Res 22(1):74–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edq003

Ten Dam G, Geijsel F, Reumerman R, Ledoux G (2011) Measuring young people’s citizenship competences. Eur J Educ 46(3):354–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2011.01485.x

Tschannen-Moran M (2014) Trust matters: Leadership for successful schools. John Wiley & Sons

Urbanska K, Pehrson S, Turner RN (2019) Authority fairness for all? Intergroup status and expectations of procedural justice and resource distribution. J Soc Polit Psychol 7(2):766–789. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v7i2.974

Uslaner EM (2002) The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press

Valcke B, Van Hiel A, Onraet E, Dierckx K (2020) Procedural fairness enacted by societal actors increases social trust and social acceptance among ethnic minority members through the promotion of sense of societal belonging. J Appl Soc Psychol 50(10):573–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12696

Van der Zee K, Vos M, Luijters K (2009) Social identity patterns and trust in demographically diverse work teams. Soc Sci Inf 48(2):175–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018409102406

Veugelers W (2011) Theory and practice of citizenship education: The case of policy, science and education in the Netherlands. Rev Educ 209–224

Wehlage GG (1989) Reducing the risk: Schools as communities of support. The Falmer Press

World Values Survey (n.d.) Project homepage, retrievable from: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.com. Accessed 19 Jun 2022

Ye F, Wallace TL (2014) Psychological sense of school membership scale: Method effects associated with negatively worded items. J Psychoeduc Assess 32(3):202–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282913504816

You S, Ritchey KM, Furlong MJ, Shochet I, Boman P (2011) Examination of the latent structure of the psychological sense of school membership scale. J Psychoeduc Assess 29(3):225–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282910379968

Zak PJ, Knack S (2001) Trust and growth. Econ J 111(470):295–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00609

Zorkić TJ, Mićić K, Cerović TK (2021) Lost trust? the experiences of teachers and students during schooling disrupted by the covid-19 pandemic. Cent Educ Policy Stud J 11(Sp. Issue):195–218

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) under Grant 411–12-035.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.F.R.K., A.M. and M.V; methodology, W.F.R.K., A.M. and M.V.; formal analysis, W.F.R.K. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.F.R.K.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and M.V.; supervision, A.M. and M.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research Ethics

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the fact that at our faculty during the period of data collection (February to June 2016) obtaining approval from an ethical review board was not yet common practice. In the Netherlands only in 2018 a general and shared ‘Code of Ethics for Research in the Social and Behavioral Sciences involving Human Participants’ was published and signed by the deans of all Dutch Social Sciences faculties. This code states that participants must give their ‘informed consent’ to take part in research: “Participants, or their legal representatives, must be given ample opportunity to understand the nature, purpose and anticipated consequences of research participation, so that they will be able to give informed consent to the extent to which they are capable of doing so.” (p. 7) Although these rules were not applicable at the time of our study, we made sure our participants, as well as the legal representatives of our student participants, were informed on matters mentioned above. Students’ legal representatives also had the opportunity to withdraw their child from participation (passive consent). Moreover, as the study took place at school during regular classes, and thus while students were under supervision of the school, the schools’ confirmation of participation in our study was additionally considered as consent.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rinnooy Kan, W.F., Munniksma, A. & Volman, M. Diverse Sources of Trust: Sense of School Membership, Generalized Social Trust, and the Role of a Diverse School Population. JAYS 6, 177–195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-023-00105-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-023-00105-y