Abstract

The present study explores how resentment and forgiveness can affect older people and how resentment can be alleviated or intensified over time. The investigation is based on a qualitative methodology, using life history interviews, carried out in two moments. Data were collected from 20 individuals over 65 years old. Data were subject to thematic content analysis. The results point to different negative impacts of resentment on well-being and different positive impacts of forgiveness. Our results suggest that over time a set of variables influence the experience of forgiving. Subsequent studies are needed to investigate these variables and validate intervention plans focused on forgiveness among older population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although constantly present in people’s lives, only in recent decades, with frequency and depth, forgiveness assumed itself as an object of study in psychology (Costa et al., 2021). Different authors point out the importance of forgiveness in the quality of personal, family, and social life (Billingsley & Losin, 2017; Worthington, 2020). Current challenges—namely the increase in life expectancy and the potential impacts of (un)forgiveness in individual well-being—have raised the interest of these topics (Akhtar et al., 2017). Our specific objectives are to explore how resentment and forgiveness condition well-being in a sample of older people and how resentment can be alleviated or intensified over time.

Several studies verify that aging incorporates biological, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions (Derdaele et al., 2019; Drewelies et al., 2019). Like the other stages of development, the most advanced phase of life brings with it specific challenges, among which the retirement, losses, and physical health problems (Toussaint et al., 2015). Most people enjoy good emotional health in this process (Suanet & Huxhold, 2020). However, many face significant problems such as depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, isolation, and insomnia. The prevalence of those challenges continues to increase (Allemand & Olaru, 2021) mainly because the older population is growing. According to the United Nations (United Nations, 2019) there were 703 million older adults in 2019 worldwide. It is estimated that by 2050, the global number of older adults will more than double—more than 1.5 billion people. The growth in the older individuals is expected to extend to all regions of the world between 2019 and 2050 (UN, 2019). In Portugal, for example, around 22% of the population is over 65 and it is expected that in 2050 one in three (33%) people will be over 65 years of age. Currently, in Portugal, more than 50% of primary health care provided for this population is associated with psychological health (FFMS, 2020).

In fact, the quality of aging depends mainly on how people adapt to it, including to the typical vulnerabilities of senescence (McLeod et al., 2021). Successful aging is related to promoting healthy lifestyles, valuing personal characteristics, compensating for losses through the optimization and selection of personal and social resources, and developing self-compassion (Baltes & Smith, 2009). Older adults tend to associate successful aging with health, satisfaction with life, social relationships, autonomy, adaptation to changes, capacity for self-care until death, feeling good about themselves, and being in accordance with their inner values (Hill et al., 2018). In this context, forgiveness has gained particular importance due to its positive correlation with well-being and longevity (Davis et al., 2015).

From the psychological perspective, forgiveness results from a personal commitment to take a compassionate attitude towards the feelings associated with an offense directed at oneself (Freedman & Zarifkar, 2016). It is a process that integrates the dialectic between what one feels and the reflection on that feeling in view of an emotional transformation (Akhtar et al., 2017). Worthington (2020) distinguishes the decision to forgive—as the intention not to react against the offender—and emotional forgiveness—that is, an emotional transformation from resentment, hurt, sadness to forgiveness, compassion, and love.

Forgiveness can include two main steps (Kim & Enright, 2014). The first has to do with taking care of one’s emotional states that may result from an offense. If these are too intense, they may neglect some fundamental needs such as support, respect, and dignity (Meneses & Greenberg, 2019). The second major step of forgiveness is to attend to the offender’s behavior in its context, perspective, circumstance, and needs (Yu et al., 2021).

Studies point to the broad benefits of forgiveness for well-being (Allemand & Olaru, 2021; Worthington, 2020). Psychotherapeutic approaches reveal positive results. Some of them focusing explicitly on promoting forgiveness (e.g., REACH Forgiveness model—Worthington, 2020) and others that indirectly facilitate it (e.g., Emotion Focused Therapy—Meneses & Greenberg, 2019).

There is no consensual definition of forgiveness (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015; Worthington, 2020). But there is consensus on what forgiveness is not in relation to other constructs (Fincham et al., 2006). In fact, forgiving is not excusing the offender and is different from forgetting—the idea that the memory of the offense has disappeared from consciousness. Unlike the notion of reconciliation, which suggests the restoration of a relationship, forgiveness does not necessarily require it (Meneses & Greenberg, 2019). If acceptance implies that the victim changes their point of view regarding the offense, forgiveness does not require this. Forgiveness differs from the idea of denying the damage suffered, and from the absolution typically delegated to a holder of power (Fincham, 2010).

It is unanimous among authors that the experience of forgiving integrates emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components (Billingsley & Losin, 2017; Ermer & Proulx, 2016; Wenzel et al., 2020). The set formed by these components enriches the phenomenon of forgiving that tends to include several stages: awareness of the offense, desire to forgive, cognitive processing, and emotional and behavioral attitude (Worthington, 2020). Thus, forgiveness—as a dynamical process—can be understood as an intrapersonal experience that, in its multiple components and at its different levels—conscious and unconscious—takes place in the context of a social interaction, in which the emotional injury resulting from an offense tends to be properly transformed (Meneses & Greenberg, 2019). According to Pedersen (2014), forgiveness narratives vary around three main domains: internal process versus external action; liberation of self versus liberation for others; long process versus epiphany of the moment.

Resentment is an emotional response that can arise in the face of interpersonal offense. Thus, more or less acute resentment—at the actual time and circumstance of the offense—can be normative (Worthington, 2020). What can become harmful to well-being (physical and mental) is lasting, ruinous, painful resentment (Krause & Hayward, 2015). When the feeling resulting from an offense is not met, a process of silence, detachment, aggression, apathy can be generated, and emotional injury endures. This attitude can contribute to blocking access to fundamental needs and, thus, disabling a more adjusted emotional reaction or preventing transformation (Greenberg & Goldman, 2019).

Dysfunctional psychological processes can occur due to lack of emotional awareness, experiential avoidance, activation of schematic memories of learned maladaptive emotional reactions, creation of rigid narratives, and conflicts between parts of the self and others (Greenberg et al., 2008; Salgado & Cunha, 2018). When this occurs, the resolution of emotional injury can go through forgiveness or the process of letting go (Meneses & Greenberg, 2019). These processes may involve the transformation of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors into compassion, generosity, and love for oneself and others (Ghaemmaghami et al., 2011). Following Greenberg et al. (2008), activating memories and implicit meanings related to the offense can facilitate emotional transformation and perspective change. The intention is to transform maladaptive emotional responses and access more adaptive emotional responses to promote better well-being (Greenberg & Goldman, 2019).

The literature on the possible effects of time on the forgiveness process is very scarce (De Geest & Meganck, 2019). The consensus prevails that the process of forgiving unfolds over time in a dynamic, progressive, interdependent, and complex way (Meneses & Greenberg, 2019; Worthington, 2020). Over time the pain resulting from an offense can be softened and can also be exacerbated, conditioning life satisfaction levels (Randall & Bishop, 2022). So the correlation of time and forgiveness is not necessarily positive or direct (Tao et al., 2021). The interaction of several variables—such as the personality and situation of the person who is offended, the severity of the offense, and the quality of the closeness between the offended and the offender—can reflect different effects (Gold & Davis, 2005). Revenge motivations and avoidance behavior tend to decrease over time (McCullough et al., 2003). The decision to forgive and proper emotional forgiveness tend to imply neuronal processes that are differentiated in mode and time (Billingsley & Losin, 2017).

The meaning of time tends to change over the years and can contribute to the appreciation of forgiveness (Carstensen, 2006; Ermer & Proulx, 2016). Time itself can trigger forgiveness as social pressure (McCullough et al., 2003). So forgiveness is not linear over time (Kaleta & Mróz, 2018). A stressful event—such as an offense—may take longer than expected to recover and can decrease well-being for several years. Beliefs such as time heals by itself and that most people are resilient can complicate the process of resolving emotional injury caused by an offense (Infurna & Luthar, 2016).

There are many reasons that show the importance of forgiveness among the older population (Allemand & Flückiger, 2020; Hantman & Cohen, 2010). First, the competence to forgive changes throughout the life cycle (Akhtar et al., 2017). Older adults tend to be more forgiving than younger ones due to the development of social and forgiveness skills (Allemand & Olaru, 2021). The very meaning of forgiveness can change over time. This change is particularly linked to the perception of future time. Aging tends to increase the value attributed to well-being and relationships (Cheng et al., 2013; Kaleta & Mróz, 2018). Another reason for studying forgiveness and aging has to do with the evidence that this stage of development is particularly willing to retrospection, problem solving, and prioritizing past and present needs (López et al., 2018; Steiner et al., 2011).

Studies find that people who recount their stories tend to be more satisfied with their lives and less associated to depression (Robertson & Swickert, 2018). In the exercise of recounting and looking at their lives, forgiveness emerges as a facilitator of the meaning of past experiences (Allemand & Olaru, 2021). Forgiving gains preponderance at this stage of development (Ermer & Proulx, 2016) in line with evidence that there is a negative correlation between forgiveness and the main proximal indicators of the end of life—in cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems (Toussaint et al., 2015). Considering the positive correlation between forgiveness, problem solving, and emotional regulation strategies (Davis et al., 2015) and the negative correlation between forgiveness, rumination, avoidance, and self-criticism (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., 2010), studying forgiveness at this stage of development becomes particularly relevant.

Despite the acknowledgement of the impact of forgiveness and resentment on people’s (physical and mental) health, only few studies seek to analyse, in an experiential way, how forgiveness and resentment affect older adults (Wenzel et al., 2020). It is important to understand how time can affect the process of forgiving, as well as studying the process of resolving an offense, in order to improve the well-being of this population. The present study sought to explore—in a sample of older adults—how time, resentment, and forgiveness can affect well-being. For this, we depart from three main research questions: RQ1. How is resentment for an interpersonal offense alleviated or intensified over time? RQ2. How does resentment impact well-being? RQ3. What is the impact of forgiveness on well-being?

Method

Research Design

To study the impact of resentment—resulting from an offense—and forgiveness, we carried out an exploratory qualitative study (Catalano & Waugh, 2020). We interpret the participants’ meanings, emotions, and experiences through an inductive analysis. We opted for the life history technique as a data collection tool to capture the phenomenon under study (Amado, 2014). Based on the participants’ narratives, we privileged dimensions that normally escape quantitative approaches, giving special emphasis to what is particular, individual, and unique (Almeida & Brandão, 2020). We used a semi-structured interview, in which ten questions emerge as stimuli to explore our three research questions.

Study Participants

Data was collected from twenty individuals over 65 years of age (in 2022 aged between 66 and 85 years and an average of 71.85). They were mostly female participants (65% females and 35% males) and they were presently all retired from their former jobs. According to Sandelowski (2004), qualitative samples should be large enough to open up new possibilities for understanding the phenomenon under study and small enough to allow for a deep and oriented analysis of the topic in question. Although these studies cannot be generalized to the global population, all of them—with well-conducted methods and good indicators in the results—can be positive for psychotherapy (Shaheen et al., 2019; Vasileiou et al., 2018). We briefly present detailed information on the participants on Table 1.

Procedures

Data Collection

We used life story technique as an instrument for collecting information. This technique invites participants to talk about their experience, provides a better approach to reality, enables the exploration of emotional dynamics, values the participants’ data in an operative way, and enriches the study with levels of depth that would otherwise be difficult to reach (Levitt et al., 2017). Throughout this study, we assumed that the participants were specialists, interpreters, and agents responsible for its development (Fonseca et al., 2012). We used a semi-structured interview so that each participant could explain their history.

The interview guide was validated using a pre-test interview with spoken reflection. Based on literature regarding the topic and the research questions (Sandelowski, 2004), a semi-structured interview was developed around ten main content questions: How have you experienced aging over the years? How does this process happen? Do you want to share a situation in your life where you were unfairly offended? Do you feel that this offense tends/tended to heal or worsen over time? Do you resent any experience in which you were unfairly offended? What kind of impact does resentment have on you? Do you feel that forgiving can alleviate your resentment? Do you remember an experience in which you forgave? What impact does forgiving provide and not forgiving? Any specific experiences that you feel are unforgivable?

After the approval of the Ethics Committee of the University, we contacted several institutions, households, and individuals, to whom we presented the purpose of the study. Twenty participants who met the defined inclusion criteria were selected. We assumed as an exclusion criterion the participants who report a serious offense—specifically incest or sexual abuse. We assume that conducting interviews about these memories could trigger intense vulnerability and suffering in the participants. So we avoid focusing our study on emotionally deep painful processes—due to their importance and severity—at the risk of not being beneficial for the participants (Shvedko et al., 2018; Timulak et al., 2020).

To minimize sampling bias, we randomly choose participants—respecting the inclusion criteria. We sent them a formal request for collaboration, explaining the purpose of the research and the ethical and confidential requirements involved. According to the possibilities of each participant, the interviews were scheduled, which, due to the context of the pandemic, were carried out via telephone. All participants signed an informed consent form. The interviews were recorded in audio format with the permission of the participants—the shortest interview lasted for 45 min and the longest interview lasted for 58 min. After being transcribed, the interviews were returned to the participants, so that each one could validate their responses—about 30 days after the first.

So the second interview looks for a better exploration of the data collected in the first interview and for any rectification—interviewee and interviewer have a copy of the transcript of the first interview. There is no predetermined time interval between each interview (Brandão, 2007). Respective interval must be sufficiently long so that transcriptions of the interviews can be made and the participants can process them internally, and suitably brief so that it is in continuity with the first (Almeida & Brandão, 2020; Braun & Clarke, 2006). Researchers used a logbook to record the information collected during the study.

Data Analysis

The interviews were analyzed using content analysis (Catalano & Waugh, 2020). The corpus of analysis was composed of the transcribed interviews, having the theme as the unit of record. We started by checking whether the transcribed material corresponded to what the participants said. Afterwards, we carried out a first scanned reading. Finally, we proceeded to a deeper reading of the data, from which the system of categories and the coding process emerged (McLeod et al., 2021). A name and an operational definition were assigned to each of the categories. To ensure the quality of the research inferences (following the recommendations of Guba & Lincoln, 1994), that is, to attest to what extent certain explanations are sustainable and must be considered, we met two major criteria: those concerning reliability and those concerning authenticity (Amado, 2014). The constitution of the categories was validated by an expert researcher in psychology. This specialist was also asked to code an interview. As the coding was broadly in agreement, we validated ours. To strengthen the interpretation carried out and the results obtained, we highlighted excerpts extracted from the participants’ speeches.

Results

Our qualitative analysis points to three main following themes: over time a set of variables tends to soften the emotional injury resulting from an offense—“the passage of time can help, but it is not enough” (P4); resentment resulting from an offense is associated in different ways with lower well-being—“when I remember I am shaken and disturbed” (P14); forgiveness has in different forms a positive impact on people’s well-being—“it brings relief, I feel more relieved, I feel happy and peaceful, I manage to fix the pain and sadness” (P1). These three main themes manifest other sub-domains that reinforce the importance of forgiveness in the participants’ experience.

Over Time a Set of Variables Can Contribute to Pain Relief

Of the 20 participants, 19 declare that over time resentment tends to be alleviated. Only one participant mentioned that with time resentment grows—“with the passage of time, it becomes more acute and heavy” (P9). Then, 95% of the participants declare that time helps to soften resentment. These participants express that over time several variables can contribute to the relief of emotional pain:

with the passage of time the offense decreases [...] the age increases and we become more forgotten (P5)

time attenuates a lot, because our mind is occupied with other things and the pain attenuates (P13)

This evidence almost generalized in the participants’ discourse allows us to discover five main variables—categories or sub-themes—that, together with time, can soften resentment: the physical and temporal distance of the situation (“It passed with time and with the physical distance”—P4); other focuses (“time helps because the person has other problems”—P12); learning (“with the passage of time the pain of the offense is healed […] everything becomes broader and more understandable, there are more important things in life”—P15); the change in the offender’s situation and behavior (“I feel compassion for my sister also for the difficulties she has been going through”—P7); and other personal efforts and strategies to deal with the problem (“the passage of time can help, but it must also be resolved with other forces”—P20).

In this dynamic process, we were able to identify four main strategies of participants to overcome their resentment: relativize the problem that happened (“It gets healed over time and, above all, with the way we look at the offense”—P11); openness to faith and transcendence (“When God tells us to see how God sees him, I include this bad behavior”—P8); blame yourself (“even a priest told me that it couldn’t be like that, that I would have to overcome it”—P10; “It makes me feel sad, I could have behaved differently”—P9); emotional avoidance (“when I think about it I don’t feel anything, I can’t hear about it”—P7). In summary, as evidenced in Fig. 1, if practically all participants report that time is associated with the softening of resentment, some strategies adopted in this sense can ease emotional injury, but others can intensify it, namely through internalization processes and emotional avoidance.

How Does Resentment Condition Emotional Well-Being?

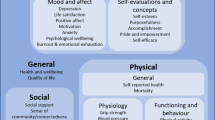

All participants report that resentment has a negative impact on their lives. Their answers point to five main impacts on well-being: physiological, mental, emotional, behavioral, and sense of self (Table 2). According to the speech and feelings of the participants, these five different expressions of resentment manifest themselves in an interdependent way and each incorporates sub-themes that highlight the complexity and interconnection of processes.

From a physiological point of view, all participants reveal, explicitly or implicitly, with greater or lesser intensity, sporadically or continuously, that over time, the resentment tends to be associated with an increase in physiological activation. This increase can be summarized in three main sub-themes: cardiac activation, stress levels, and sleep difficulties. According to the participants’ discourse, this set of variables can result in a feeling of tiredness, tightness, and physical exhaustion.

I felt in my body like approaching a weight [...] at night I had difficulty sleeping (P1)

I feel pain in the chest, tachycardia [...] I become slower, heavier, farther away from myself and others, it takes me to isolation (P9)

We observe that resentment can also have a negative mental impact. We were able to identify in the participants’ speeches main sub-categories of cognitive or mental consequences caused by resentment, namely, in the form of continuous rumination, mental energy wear, loss of focus, and difficulty in solving problems. The participants particularly highlight the mental dimension in their narratives and internal processes. These tend to be marked by elaborate reflexive dynamics, as following examples attested:

there are things I couldn’t forget [...] when it comes to my mind [...] I don’t want to remember, remember, I don’t want [...] not to go back there, don’t slip (P1)

there are moments of explosion when I start thinking about these things (P7)

Another effect of the resentment reported by all respondents is emotional. We found four sets of emotional states of the participants—sadness, anger, deception, indignation—that are assumed, with greater or lesser intensity, as a weight that accompanies them. The emotional dimension, despite being less considered in the verbal speech of the participants, shows to be significantly important in the non-verbal speech and in its intense impact with the other components listed.

I feel sad [...] a kind of annoyance, psychological discomfort, there was no explanation, something that doesn’t come out of me, almost like a wound, sadness, anger (P1)

I felt tension, revolt, I didn’t distance myself from people or situations, but I didn’t act either [...] I was sad (P2)

From our collected data, resentment can also be expressed behaviorally. The behavioral impact of resentment can refer to attitudes towards oneself, towards others or towards the offenders themselves. These behavioral dynamics can lead to physical separation, which depends on variables such as relational complexity and the degree of involvement in it. This kind of resentment impact is linked to isolation, as a social dimension of resentment.

resentment gives me pain, it also gives me distance from my brother in relation to me. I try to get closer and so does he, but there is something that makes it difficult (P3)

it makes me slower, heavier, further removed from myself and others, leads me to isolation (P9)

Regarding the sense of self—understood here as the feeling of what happens, the continuous process of self-organization (Greenberg & Goldman, 2019)—the participants refer to the impact of resentment on the relationship to oneself. We were able to identify in the speech of the participants four main sub-themes: experiences of anguish, negative affect, neglected self, and feelings of inferiority.

It’s always negative. It’s always a way of putting my saddest self, incapacitated, something that prevents me from doing what I want, it can make me lose capacity in relation to all of this. As if it paralyzed me (P4)

the resentment affected me, I felt diminished, I couldn’t do things well, added to the resentment by blaming, I felt sad [...] I felt diminished, erased (P11)

What is the Impact of Forgiveness on People’s Well-Being?

Considering our third research question, we identified five main themes concerning the positive impact of forgiveness on the well-being of our participants: physiological, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and self-transformation (Table 3). These different expressions of the impact revealed in the participants’ discourse have different sub-dimensions and these are interrelated with each other.

At a physiological dimension, in contrast to what was mentioned about resentment, forgiveness seems to have an impact on the level of activation itself. This is presented by the participants in three more significative expressions: tranquility, serenity, calm.

it makes me feel good, because it takes the negative out of me [...] it allows me to be well [...] it’s a tranquilizer, everything’s fine with me, I don’t have a stone biting or massacring me [ ...] forgiveness gives me rest [...] we go from nightmare, nervousness, rebellion, insomnia, to peace, as if it were a tranquilizer (P8)

it makes the stomach feel relieved, even in my head I feel better, relief, I sleep better, I relax (P9)

Another type of impact mentioned by the participants is related to the cognitive dimension. Indeed, among the various expressions associated with this kind of impact, we were able to point out three main categories: reduction of rumination, decrease of negative thoughts, and increase of focus on the here and now.

allows me to focus on my responsibilities (P2)

be more relaxed, stop thinking about the conflict, losing energy in this regard (P4)

Participants report that forgiveness is associated with different emotional states that bring well-being. Among the various emotions reported by the participants, we were able to identify three most representative: relief, peace, and joy. According to the participants’ discourse, these feelings described tend to appear particularly linked to the transformation or overcoming of feelings such as anguish, fear, and sadness caused by resentment in the face of the offense. Participants thus signal that forgiveness:

It allows us to overcome anguish, fear, sadness, suffering, the accumulation of tensions that hurt and spoil everything (P3)

when you are able to truly forgive, it gives a special enjoyment, well-being, serenity. It feels very good (P7)

Another sub-theme supported by the participants’ discourse refers to the fact that forgiveness can have a positive impact on one’s own behavior. Participants talk about three main domains of this type of impact: in who forgives, in who is forgiven, and on the social context itself. According to the participants’ narratives, forgiveness tends to promote peace, reconciliation, and understanding between people and situations. In this sense, it should also be noted that the participants report that forgiving provides more harmonious family and social behaviors.

It allows for the restoration of bonds, a good atmosphere and happiness (P2)

It brings me happiness, I feel better, I walk better, I feel more energy, I feel more connected with other people and with myself (P9)

Finally, a fifth type of forgiveness impact mentioned by the participants concerns the transformation of the self—learning about oneself and one’s relationships in a more compassionate and accomplished way (Baltes & Smith, 2009). Around the dimension of the transformation of the self, we identify three main sub-themes in the responses of the participants: sense of satisfaction and personal openness; improvement of internal narratives; and increased empathy for others.

it allows us to leave ourselves and put ourselves in the other’s shoes (P4)

has great impact. And it all. I am the happiest woman in the world for not gaining negative feelings such as resentment and envy [...] I feel more fulfilled (P5)

Discussion

This study seeks to explore the way in which time, resentment, and forgiveness can affect the well-being of older people. Our qualitative analysis contributes to increasing knowledge about the impact of resentment and forgiveness on the well-being of older population. The thematic analysis identifies two main themes from our first research questions (How is resentment for an offense alleviated or intensified over time?). First, the process of forgiving unfolds over time. Second, although a certain amount of time is needed to deal with the offense, the alleviation of pain does not depend on the simple passing of time—this process seems to be influenced by a set of variables experienced during this period. These participants’ perspectives are corroborated by several authors (Kent et al., 2018; Randall & Bishop, 2022). The factors that influence forgiveness can be located in different spheres: offended person, offender, and relationship between the offended and the offender (Carstensen, 2006).

According to the participants’ discourse, and focusing specifically in the sphere of the offended person, the following dimensions prove to be relevant to alleviating emotional injury over time: temporal and physical distance, emerging of other problems, learning, offender’s attitude, and strategies used to deal with the situation. Some of the strategies mentioned—such as relativization and transcendence—can resolve the emotional injury, while others can lead to its intensification, namely the processes of internalization and avoidance (Cheng et al., 2013; Upenieks, 2021). This ambiguity is evidenced in the speech of the participants, verbal and non-verbal. In face of this internal conflict, it is relevant to mention that offended people tend to decrease their motivations for distance and revenge over time and decide to forgive. But they do not demonstrate the same increase in benevolent and compassionate motivations over time toward offenders (McCullough et al., 2003).

So the psychological processes that increase the will to reestablish relationships with an offender tend to be more complex and time-consuming than the processes that promote evasion and retaliation against an offender (Fincham, 2010). Different patterns of forgiving, more or less contradictory, may coexist over time (Gold & Davis, 2005). The participants’ testimonials allows us to observe that time is more associated with the decision to forgive and the corresponding attitude of avoiding conflicts, than emotional forgiveness—a process of transforming emotions (such as sadness, resentment, anger into empathy, compassion, love)—which occurs, when carried out, over a longer period of time (Worthington, 2020).

With the passage of time, oscillations and ambiguities may prevail, in a more or less intense and implicit or explicit way, in the process of alleviating pain. This process seems to be conditioned by several variables—personal, situational, and interpersonal—which together constitute the meaning and the emotional experience of the offense. In short, it appears that how each person processes this meaning is particularly related to how pain can be alleviated over time. For all reasons, and particularly with a view upon the quality of aging, it is important to value this process. Because if interpersonal conflicts are inevitable and if their impact can be more or less serious, it is the personal capacity to transform them that will determine the possibility or effectiveness of forgiveness (Worthington, 2020).

Based on the experience of our participants, we identified that resentment can have a negative impact on personal well-being in different ways—physiological, mental, behavioral, emotional, and sense of self. Resentment—in its complexity and interconnected dimensions—is not beneficial to physical health and can impact blood pressure, heart pressure, and the immune system (Billingsley & Losin, 2017). It can increase stress and, when intense and continued, can affect digestion, blood circulation, and sexual performance. Resentment can trigger the continued resumption of past memories and trigger depressive, anxious, phobic, and psychosomatic processes (Gold & Davis, 2005). The triggering of these processes and their interrelation can increase difficulties in different contexts—family, network of friends, and work—which are often associated with spirals of shame and resentment (Thompson et al., 2005). Resentment can affect emotions (anger, sadness, frustration, depression, disgust, loneliness, betrayal), cognitions (blaming, rumination, thoughts of forgiveness, confusion, revenge, apprehension), behaviors (withdrawal, isolation), relationships (ending relationships, avoidance) and, therefore, self-sense (Williamson & Gonzales, 2007).

Thus, resentment can remain beyond the offense event, as its meaning can extend to bodily sensations, mental constructions, and feelings with behavioral and self-implications (Akhtar et al., 2017). Despite this evidence, the focus of our participants does not tend to be taking care of the emotional injury, but rather talking about it and avoiding it. This tendency can be understood in the light of some internal conflicts and strategies assumed by those who are offended as described above. We know that feelings that are not processed or attended to can contribute to dynamics of silence, detachment, and aggression—these feelings can be even intensified. At the same time, they can raise the dissatisfaction of core needs, such as support and understanding, which are important at different levels as well as to heal their own resentment (Briere et al., 2016). So, part of the suffering resulting from an offense may result from mechanisms of lack of awareness, denial, activation of memories, and non-adaptive responses, based on rigid and dysfunctional processes (Greenberg, 2015). It seems that the way people deal with resentment is associated with its impact and the way it can be emotionally processed.

Our phenomenological design enables us to identify that forgiveness can promote well-being, namely, physiological, mental, behavioral, emotional, and the sense of self. In the participants’ discourse, these levels are mutually interrelated. A consensus prevails among a wide range of authors regarding the evidence that forgiving is positively associated with physical, emotional, relational, and spiritual benefits (Friedberg et al., 2009; Kent et al., 2018). In line with what was reported by our participants, forgiving tends to lessen anxious and depressive symptoms (Fatfouta et al., 2014). Not being synonymous with reconciliation, disclaiming the offender, eliminating the past or disrespecting moral and societal values (Worthington, 2020), forgiving can bring relief, love, tranquility, understanding, and growing motivation (Rey & Extremera, 2016; Svalina & Webb, 2012). In this sense, forgiveness, in the interconnection of its various positive impacts, tends to promote family and social understanding and to generate societal advancement (Kent et al., 2018). Forgiveness can make possible to overcome the pain of the offense and, at the same time, the emotional transformation in view of a better well-being; and well-being tends to increase when the decision to forgive is part of emotional forgiveness (Tao et al., 2021).

In fact, establishing meaningful, deep, and lasting emotional relationships is among the fundamental psychological needs (Bowlby, 1997). The realization of this universal need is expressed in each individual—throughout their life cycle—differently, also due to their contexts and the ability to integrate their learning. The way individuals—in a more or less secure way—carry out new learnings is positively related to the quality of relationships, the strengthening of autonomy and self-esteem (McCluskey, 2005).

Indeed, the capacity for emotional regulation—to modulate the emotional activation conducive to the integrative behavior of different experiences—promotes the reorganization of the self itself, namely, in situations of interpersonal offense (Greenberg & Goldman, 2019). Different emotion regulation strategies—awareness and understanding of what one feels, acceptance of one’s emotions, ability to manage action tendencies, freedom to act according to personal principles, purposes, and contexts (Greenberg, 2015)—may influence the way individuals deal with forgiveness and may be the basis of better well-being (Ho et al., 2020).

Despite the evidence regarding the benefits of forgiving, our participants reveal that the forgiveness process is not linear—it tends to be cyclical and dynamic, with advances and setbacks. This reality may be based, on the one hand, on the different priorities and strategies assumed by each of the participants—not always congruent—and, on the other, on the very complexity of variables involved in the process of forgiving (Allemand & Flückiger, 2020). The fact that our participants do not explicitly distinguish decision-making from emotional forgiveness may be another reason that adds to the variance in the dynamics of the forgiving process. Participants tend to express a willingness to forgive and, at the same time, reveal difficulties in the process of emotional transformation—in an explicit way and continued over time. Nevertheless, the participants’ discourse corroborates the evidence that the passage of time, new learning, and adjusted strategies—such as the ability to reread their stories—can potentiate the benefits of forgiving (Allemand & Olaru, 2021).

In the dynamics of forgiveness, participants distinguish between intrapersonal and interpersonal dimensions. Paradoxically, our participants reveal that the main focus is to overcome internal suffering and to avoid inappropriate or antisocial actions to the offender. Therefore, even if the resolution of emotional injury can go through forgiveness or the process of letting go (Meneses & Greenberg, 2019), this focus does not always prevail.

Considering the totality of the participants’ narratives in which they report difficulties in the process of forgiving, 29% of these refer to self-conflicts, 26% to processes of rationalization, 21% to vulnerability, 13% to dynamics of lack of responsibility, and finally, 11% of these to avoidance strategies. These various difficulties seem to be interrelated. Our data reveal that time by itself does not determine the easing of emotional injury. So the present investigation opens the door to a specific intervention protocol that can benefit people in their process of forgiving in light of some of the difficulties now revealed. Our study also highlights the importance of decision-making and emotional forgiveness towards a true resolution of the emotional injury caused by an offense. Assuming that aging tends to be related to a growing capacity for introspection and the relativization of situations (López et al., 2018), if these are accompanied by a similar qualification of the processes of learning and emotional transformation, a field of enormous potential for successful aging opens up.

Conclusions and Implications for Future Research

Our qualitative study allows us to have a look at how, over time, a series of variables can ease the pain of resentment and facilitate the process of forgiveness. Our research points out that resentment brings with it a wide range of negative impacts, namely, physiological, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, social, and the sense of self. Our participants attest that the forgiveness—the decision to forgive and emotional forgiveness—generates an important set of benefits in people’s well-being from the physiological, cognitive, emotional, social, behavioral, and transformational point of view of own self. The study allows us to have a perspective on how the meaning given to the offense can be related to how the respective pain is relieved over time. So it is extremely important to value this process. Even the limited number of participants, the approach to their living reality is one of the strengths of this study.

Our study points to the emergence of a set of subjective variables—self-disruption processes, internal conflicts, emotional access difficulties, vulnerabilities, and rationalization cycles—which may influence the understanding and experience of forgiving, justifying further future studies. To extend current knowledge, further research is needed to better understand those variables that can influence the process of forgiving. It also opens up a field of research that seeks to understand strategies, preventive measures, and intervention plans that promote the well-being of older people when faced with the emotional pain resulting from an offense.

Data Availability

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, B.A., upon reasonable request.

References

Akhtar, S., Dolan, A., & Barlow, J. (2017). Understanding the relationship between state forgiveness and psychological wellbeing: A qualitative study. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(2), 450–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0188-9

Allemand, M., & Flückiger, C. (2020). Different routes, same effects: Managing unresolved interpersonal transgressions in old age. GeroPsych, 33, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000237

Allemand, M., & Olaru, G. (2021). Responses to interpersonal transgressions from early adulthood to old age. Psychology and Aging, 36(6), 718–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000610

Almeida, B., & Brandão, C. (2020). Gerindo a transição: estratégias de exploração no processo para ser líder. REVES - Revista Relações Sociais, 3(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.18540/revesvl3iss2pp0049-0064

Amado, J. (2014). Manual de investigação qualitativa em educação. Universidade de Coimbra.

Baltes, P., & Smith, J. (2009). Lifespan psychology: From developmental contextualism to developmental bicultural co-constructivism. Research in Human Development, 1, 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427617rhd0103_1

Billingsley, J., & Losin, E. A. R. (2017). The neural systems of forgiveness: An evolutionary psychological perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 737. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00737

Bowlby, J. (1997). Attachment and loss. Pimlico.

Brandão, A. M. (2007). Entre a vida vivida e a vida contada: a história de vida como material primário de investigação sociológica. RepositóriUM, 3, 83-106. https://hdl.handle.net/1822/9630

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briere, J., Agee, E., & Dietrich, A. (2016). Cumulative trauma and current posttraumatic stress disorder status in general population and inmate samples. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 8(4), 439–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000107

Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 6, 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

Catalano, T., & Waugh, L. R. (2020). Critical discourse analysis, critical discourse studies and beyond. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2021.1918196

Cheng, S.-T., Ip, I. N., & Kwok, T. (2013). Caregiver forgiveness is associated with less burden and potentially harmful behaviors. Aging & Mental Health, 17(8), 930–934. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.791662

Costa, L., Worthington, E. L., CavadasMontanha, C., Couto, A. B., & Cunha, C. (2021). Construct validity of two measures of self-forgiveness in Portugal: A study of self-forgiveness, psychological symptoms, and well-being. Research in Psychotherapy, 24(1), 500. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2021.500

Davis, D. E., Ho, M. Y., Griffin, B. J., Bell, C., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., DeBlaere, C., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Westbrook, C. J. (2015). Forgiving the self and physical and mental health correlates: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000063

De Geest, R. M., & Meganck, R. (2019). How do time limits affect our psychotherapies? A literature review. Psychologica Belgica, 59(1), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.475

Derdaele, E., Toussaint, L., Thauvoye, E., & Dezutter,. (2019). Forgiveness and late life functioning: The mediating role of finding ego-integrity. Aging & Mental Health, 23(2), 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1399346

Drewelies, J., Huxhold, O., & Gerstorf, D. (2019). The role of historical change for adult development and aging: Towards a theoretical framework about the how and the why. Psychology and Aging, 34(8), 1021–1039. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000423

Enright, R. D., & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2015). Forgiveness therapy: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14526-000

Ermer, A. E., & Proulx, C. M. (2016). Unforgiveness, depression, and health in later life: The protective factor of forgivingness. Aging & Mental Health, 20(10), 1021–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1060942

Fatfouta, R., Schröder-Abé, M., & Merkl, A. (2014). Forgiving, fast and slow: Validity of the implicit association test for predicting differential response latencies in a transgression-recall paradigm. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 728. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00728

FFMS. (2020). Retrato de Portugal na Europa: PORDATA. Retrieved from https://www.ffms.pt/sites/default/files/2022-08/Retrato-de-Portugal-na-Europa-2020%20_pordata.pdf

Fincham, F. D. (2010). Forgiveness: Integral to a science of close relationships? In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behavior: The better angels of our nature (pp. 347–365). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12061-018

Fincham, F. D., Hall, J. G., & Beach, S. R. H. (2006). Forgiveness in marriage: Current status and future directions. Family Relations, 55(4), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2005.callf.x-i1

Fonseca, L., Araújo, H. C., & Santos, S. (2012). Sexualities, teenage pregnancy and educational life histories in Portugal: Experiencing sexual citizenship? Gender and Education, 24(6), 647–664. https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/handle/10216/100085

Freedman, S., & Zarifkar, T. (2016). The psychology of interpersonal forgiveness and guidelines for forgiveness therapy: What therapists need to know to help their clients forgive. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000087

Friedberg, J. P., Suchday, S., & Srinivas, V. S. (2009). Relationship between forgiveness and psychological and physiological indices in cardiac patients. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-008-9016-2

Ghaemmaghami, P., Allemand, M., & Martin, M. (2011). Forgiveness in younger, middle-aged and older adults: Age and gender matters. J Adult Dev, 18, 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-011-9127-x

Gold, G. J., & Davis, J. R. (2005). Psychological determinants of forgiveness: An evolutionary perspective. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations, 29(2), 111–134. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23262798

Greenberg, L. S. (2015). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings (2nd ed.). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14692-000

Greenberg, L. S., & Goldman, R. N. (2019). Theory of practice of emotion-focused therapy. In L. S. Greenberg & R. N. Goldman (Eds.), Clinical handbook of emotion-focused therapy (pp. 61–89). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000112-003

Greenberg, L. J., Warwar, S. H., & Malcolm, W. M. (2008). Differential effects of emotion-focused therapy and psychoeducation in facilitating forgiveness and letting go of emotional injuries. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(2), 185–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.185

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1944). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage Publications Inc.

Hantman, S., & Cohen, O. (2010). Forgiveness in late life. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 53(7), 613–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2010.509751

Hill, P. L., Katana, M., & Allemand, M. (2018). Investigating the affective signature of forgivingness across the adult years. Research in Human Development, 15(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2017.1414526

Ho, M.Y., Van Tongeren, D.R., & You, J. (2020). The role of self-regulation in forgiveness: A regulatory model of forgiveness. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 1084. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01084

Infurna, F. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2016). Resilience to major life stressors is not as common as thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11, 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615621271

Ingersoll-Dayton, B., Torges, C., & Krause, N. (2010). Unforgiveness, rumination, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 14(4), 439–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903483136

Kaleta, K., & Mróz, J. (2018). Forgiveness and life satisfaction across different age groups in adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.008

Kent, B. V., Bradshaw, M., & Uecker, J. E. (2018). Forgiveness, attachment to God, and mental health outcomes in older U.S. adults: A longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 40(5), 456–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517706984

Kim, J. J., & Enright, R. D. (2014). A theological and psychological defense of self-forgiveness: Implications for counseling. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 42, 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/00916471140420

Krause, N., & Hayward, R. D. (2015). Aging, forgiveness, and health. In L. L. Toussaint, E. L. Worthington, & D. R. Williams (Eds.), Forgiveness and health (pp. 205–220). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9993-5_14

Levitt, H. M., Motulsky, S. L., Wertz, F. J., Morrow, S. L., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2017). Recommendations for designing and reviewing qualitative research in psychology: Promoting methodological integrity. Qualitative Psychology, 4(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000082

López, A., Sanderman, R., & Schroevers, M. (2018). A close examination of the relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. Mindfulness, 9, 1470–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0891-6

McCluskey, U. (2005). To be met as a person: The dynamics of attachment in professional encounters. Karnac Books.

McCullough, M. E., Fincham, F. D., & Tsang, J. (2003). Forgiveness, forbearance, and time: The temporal unfolding of transgression-related interpersonal motivations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 540–557. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.540

McLeod, J., Stiles, W. B., & Levitt, H. (2021). Qualitative research: Contributions to psychotherapy practice, theory and policy. In M. Barkham, W. Lutz, & L. Castonguay (Eds.), Bergin & Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change: 50th anniversary edition (pp. 351–384). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Meneses, C. W., & Greenberg, L. S. (2019). Forgiveness and letting go in emotion-focused therapy. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000144-000

Pedersen, J. R. (2014). Competing discourses of forgiveness: A dialogic perspective. Communication Studies, 65(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2013.833526

Randall, G. K., & Bishop, A. J. (2022). Forgotten variables and older men in custody: Negative childhood events, forgiveness, and religiosity. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 94(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/00914150211031892

Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2016). Forgiveness and health-related quality of life in older people: Adaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies as mediators. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(12), 2944–2954. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315589393

Robertson, S. M. C., & Swickert, R. J. (2018). The stories we tell: How age, gender, and forgiveness affect the emotional content of autobiographical narratives. Aging & Mental Health, 22(4), 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1269149

Salgado, J., & Cunha, C. (2018). The human experience: A dialogical account of self and feelings. In A. Rosa & J. Valsiner (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Sociocultural Psychology (pp. 503–517). Cambridge University Press. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.24/1631

Sandelowski, M. (2004). Using qualitative research. Qualitative Health Res, 14(10), 1366–1386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304269672

Shaheen, M., Pradhan, S., & Ranajee, R. (2019). Sampling in qualitative research. In M. Gupta, M. Shaheen, & K. Reddy (Eds.), Qualitative Techniques for Workplace Data Analysis (pp. 25–51). IGI Global. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345131737.

Shvedko, A. V., Thompson, J. L., Greig, C. A., & Whittaker, A. C. (2018). Physical activity intervention for loneliness (PAIL) in community-dwelling older adults: Protocol for a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud, 4, 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-020-00587-0

Steiner, M., Allemand, M., & McCullough, M. E. (2011). Age differences in forgivingness: The role of transgression frequency and intensity. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 670–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.09.004

Suanet, B., & Huxhold, O. (2020). Cohort difference in age-related trajectories in network size in old age: Are networks expanding? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 75(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx166

Svalina, S. S., & Webb, J. R. (2012). Forgiveness and health among people in outpatient physical therapy. Disability and rehabilitation, 34(5), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2011.607216

Tao, L., Zhu, T., Min, Y., & Ji, M. (2021). The older, the more forgiving? Characteristics of forgiveness of Chinese older adults. Frontiers in psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.732863

Thompson, L. Y., Snyder, C. R., Hoffman, L., Michael, S. T., Rasmussen, H. N., Billings, L. S., Heinze, L., Neufeld, J. E., Shorey, H. S., Roberts, J. C., & Roberts, D. E. (2005). Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. Journal of Personality, 73(2), 313–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00311.x

Timulak, L., Keogh, D., McElvaney, J., Schmitt, S., Hession, N., Timulakova, K., Jennings, C., & Ward, F. (2020). Emotion-focused therapy as a transdiagnostic treatment for depression, anxiety and related disorders: Protocol for an initial feasibility randomised control trial. HRB open research, 3, 7. https://doi.org/10.12688/hrbopenres.12993.1

Toussaint, L. L., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Williams, D. R. (Eds.). (2015). Forgiveness and health: Scientific evidence and theories relating forgiveness to better health. Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9993-5

United Nations (2019). World population prospects 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/publications/files/wpp2019_highlights.pdf

Upenieks, L. (2021). Changes in religious doubt and physical and mental health in emerging adulthood. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 60(2), 332–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12712

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

Wenzel, M., Woodyatt, L., Okimoto, T. G., & Worthington, E. L. (2020). Dynamics of moral repair: Forgiveness, self-forgiveness, and the restoration of value consensus as interdependent processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4, 607–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220937551

Williamson, I., & Gonzales, M. H. (2007). The subjective experience of forgiveness: Positive construals of the forgiveness experience. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(4), 407–446. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2007.26.4.407

Worthington, E. L., Jr. (2020). An update of the REACH Forgiveness model: Psychoeducation in groups, do-it-yourself formats, couple enrichment, religious congregations, and as an adjunct to psychotherapy. In E. L. Worthington Jr. & N. G. Wade (Eds.), Handbook of forgiveness (pp. 277–287). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351123341-26

Yu, L., Gambaro, M., Song, J. Y., Teslik, M., Song, M., Komoski, M. C., Wollner, B., & Enright, R. D. (2021). Forgiveness therapy in a maximum-security correctional institution: A randomized clinical trial. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(6), 1457–1471. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2583

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants who support the present study for their time and willingness to participate in the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). The authors acknowledge the support of the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under Pluriannual Funding Programme for Research Units 2020-2023 UIDP/00050/2020 and the EmpoweringEFT@EU project (Erasmus+ Project N.º 2020-1-PT01-KA202-078724).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The present study was approved by the University Ethical Committee by its commission designated as the Council of Ethics and Deontology of the University of Maia. The approval number given by the ethical board is 40/2021.

Consent to Participate

The participants gave their informed consent to participate in the present study. All participants signed the informed consent.

Consent for Publication

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that all authors gave their consent to publish the present study and to reproduce the present study in further studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Almeida, B., Cunha, C. Time, Resentment, and Forgiveness: Impact on the Well-Being of Older Adults. Trends in Psychol. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-023-00343-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-023-00343-2