Abstract

Sustainable societies require that a diverse set of risks (e.g. socio-economic, environmental, political and cultural) that intervene with peoples’ wellbeing levels are systematically addressed. Here we focus on life satisfaction and the social cohesion effects driven from the perceptions of others in contemporary societies. We postulate that perceptions of risk as drawn from ‘otherness’ are dependent upon citizens’ evaluations of trust in key societal institutions and their perceptions of civic (socio-economic and cultural) distance. Trust is a risk mitigation factor whereas distance exacerbates perceptions of exposure to various risk parameters. This constitutes a complex policy intervention challenge suggesting that the use of decision-making tools that are able to handle a large set of information is appropriate. To that extent, we propose the use of a hybrid TOPSIS-Entropy multicriteria technique and test our trust and distance risk effects hypotheses using case study data for Greece. After controlling for the socio-demographic and economic profile of respondents, we provide support for the role of trust in institutions and feelings of distance as determinants of life satisfaction. Important policy level implications are derived on the basis of these findings. Improvements in life satisfaction might be seen as policy interventions that aim at improving civil society institutions. Interventions might involve formal and/or informal institutions that affect both objective (e.g. safety/crime) and subjective (e.g. feelings of safety/disorder) quality of life judgements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Life satisfaction is about personal judgements of subjective quality of life. As defined by Diener [1], it is a ‘… cognitive evaluation of one’s life’. The concept of life satisfaction has evolved as a valuable tool for informing policies that aim at improving the well-being of citizens [2,3,4]. Life satisfaction provides an aggregate of people’s experiences and evaluations in a number of individual life domains [2, 5]. As such, life satisfaction is considered as one of the most prominent measures of life standards evaluations providing an inclusive appraisal between reality and peoples’ expectations [6].

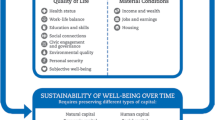

Many factors have been identified as determinants of life satisfaction judgements. Indeed, the cognitive evaluations of one’s life are subject to a wide range of objective and subjective factors identified at the economic, social, psychological, political, institutional and environmental context of individuals [7,8,9,10]. The quest for living environments that will provide increased life satisfaction levels now incorporates all these factors as the accomplishment of sustainability goals in the economic, cultural and political spheres of a society. To that extent, inclusive growth and prosperity, social goods and good governance are meant to be the economic, socio-cultural and political outcomes of sustainability that underlie better living conditions [11]. Communities, as the characteristic social institution of societies, are often assumed to be spheres that ad hoc generate social goods such as a sense of security and identity, social cohesion and stability [12]. However, this aspect of sustainability has been rather overlooked under a three pillar theorisation of the notion that leaves social concerns to be a rather residual output of the economic and political achievements of societies, i.e. under an equivalent perception of the ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’ concepts [11, 13]. Today, smart cities are presented with important social risks (e.g. civil security) to which little attention is paid [14]. The link between Industry 4.0 and Society 5.0 research on the goals and challenges for smart city societies reveals the different domains where such risks might be identified and where interventions are needed [15].

In view of the above, public organisations need to be well-focused on addressing such risks efficiently and thus, knowledge in the field is important. Here we focus on the social sustainability of societies as promoted through strong and interconnected communities. In particular, we analyse the trust and distance (proximity) evaluations of peoples’ social, economic, institutional and political environment as affecting their subjective evaluations of well-being and consequently, the social sustainability and cohesion of their community. We postulate that these two facets of social relations are indicative of either coherent societies in the case where trust dominates or divided societies in the case where distance prevails. Extant knowledge suggests that perceptions of ‘others’ in contemporary multicultural societies (communities) are a critical risk parameter affecting both identity and the sense of belonging, i.e. feelings of friendship, affirmation, recognition etc. [16]. This ‘risk’ therefore, relates to all life domains and functions of individuals. Empirical research does verify the contemporary societies’ struggle to address a number of citizens’ perceived safety challenges, ranging from feelings of insecurity, with regard to one’s job and income, to perceptions of belonging to the community and living environment standards [4, 17,18,19]. Lianos [16] analyses these challenges as the outcome of the wider socioeconomic and political developments of western societies which, he argues, comprise a ‘risk society’ context. Otherness determines peoples’ integration into modern environments and thus perceptions of danger and/or risk might increase socio-economic insecurity and social division [20]. On the other hand, general trust and confidence, collectivism and sociability alleviate individuals’ perceptions of risk, thus positively impacting their subjective well-being evaluations [21, 22].

In that context, we focus here on trust and distance as two key sustainability determinants and propose testable empirical hypotheses for measuring their impact on life satisfaction judgements. We empirically test our hypotheses using multicriteria analysis techniques. A MCDM is dealing with designing computational and mathematical tools for supporting the subjective evaluation of performance criteria. MCDM is a generic term for all methods that exist for helping people make decisions according to their preferences, in cases where there is more than one conflicting criterion. Such techniques allow us to effectively evaluate and rank the factors affecting peoples’ assessments of life satisfaction. For our empirical estimations, we use secondary data drawn from two sources, namely, the 2018 Eurobarometer survey for Greece, which provides detailed micro level data (a total of 1012 individual level observations) and from the Hellenic Police dataset base which provides regional (10 NUTS II regions) crime rates data for 2017.

The study makes a twofold contribution. On the one hand, we apply a more informative theoretical context to the analysis of variations in life satisfaction judgements. Through the use of the notion of distance, we more closely approximate the life satisfaction effects of sociability and peoples’ feelings of closeness to (or distance from) others [23]. On the other hand, at the empirical level, we approach the problem as a multicriteria decision-making problem (MCDM). The proposed hybrid models rely on the use of the Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) method to identify and rank all the crucial drivers of life satisfaction and the entropy method to calculate the weight of all the criteria in TOPSIS computation. The main advantage of the method is that it allows us to fully utilise the inherent information contained into the data avoiding thus the subjective assessments of evaluators, a problem arising often in the implementation of the TOPSIS method. In line with current contributions in the field that deal with relevant issues such as neighbourhood sustainability [24], residential choice [25] and home safety perceptions [26], our empirical results provide valuable insights with regard to the risk effects of trust and distance on life satisfaction judgements, thus enhancing the design of informed policy measures in the field.

2 Background Knowledge and Hypotheses

Life satisfaction is a multidimensional concept, comprised of a number of objective and subjective quality of life domains [27]. Objective measures are relevant comparisons of ‘well-being, health, productivity, intimacy, safety and community and emotional well-being’, whereas subjective measures comprise the importance of these domains as weighted by the individual [27]. The body of research regarding life satisfaction, its determinants and policy relevant advice is continuously growing. Research focuses on a variety of theoretical and empirical issues in light of the increasing need to provide policy level information and insights. At the theoretical level, emphasis is placed upon the development of tools and measures that most accurately depict life satisfaction [3, 4, 8, 9]. For example, Cummins [5, 27] developed a Comprehensive Quality of Life Scale (ComQol) that was proved to be an economic and valid measure of classifying the seven individual life satisfaction domains. Helliwell in [28] focuses on the study of the interrelationship between micro and macro level determinants of life satisfaction, i.e. between individual and national level parameters of well-being. Indicative is the study of Helliwell and Putnam [17], who explore the social context of subjective well-being evaluations and in particular the role of trust and different types of ties.

At the empirical level, research typically controls for the effect that the socio-demographic and economic profile of individuals, e.g. age, gender, marriage, material well-being, etc., exerts upon life satisfaction levels (see indicatively [18, 29,30,31]). Evidence with regard to sign and magnitude of these effects may vary albeit their overall importance is verified. Indicative are the evidence of Myers [21] who have recently undertaken a comparative analysis of subjective well-being levels across 98 countries and tested for the effects of these standard control variables. They identify age (+), gender (+ for female respondents), income rank (−/+) and marital status (−) to be robust predictors of subjective wellbeing levels across countries [32]. Income inequality rates in particular, as a key growth indicator, are increasingly analysed in cross country comparisons of life satisfaction levels (see indicatively [6, 28, 33,34,35]).

In light of the above, our first empirical hypothesis (H1) actually controls for the socio-demographic and economic profile of individuals as encompassing key life satisfaction domains (namely, age, gender, education, marriage, social and economic status etc.). In particular, we test the following hypothesis:

H1: Life satisfaction is affected by the socio-demographic and economic profile of individuals.

Our second hypothesis relates to analysing the role of trust as a determinant of life satisfaction. Trust, whether general or particularised, has been proven to relate to almost all life satisfaction domains such as emotional well-being, sociability and community cohesion and productivity [36, 37]. Helliwell and Putnam analyse in [17] the many different channels and forms of social capital as determinants of subjective well-being. As they argue, trust, family and workplace ties, sociability and civic participation, are directly and indirectly related to individual’s life satisfaction levels [17]. Furthermore, social capital can help citizens express their views and actively participate in community projects that are meant to improve their quality of life and their living environment [38]. In [39], Anheier et al. employ a cross-national perspective to analyse social capital as a ‘predictor of life satisfaction across a broad range of countries that differ in culture, politics, religion and economic development’. They find social capital to be related with life satisfaction through its links with a sense of community that advances community life, caring, membership, socialising, etc. [39]. Kroll [40] performs a cross-national comparison of aggregate social capital and life satisfaction scores for 72 countries. He reports structural (i.e. membership) and cognitive (i.e. generalised trust) social capital to be positively associated with subjective well-being (SWB) at the cross-national level [40]. Similarly, Elgar et al. [41] developed a four-factor measure of social capital in order to explore the links between social capital and self-rated health and life satisfaction. Using a sample of 50 countries, both rich and developing ones, they provide evidence of greater social capital benefits for women, older and more trusting adults [41]. Serag El Din et al. [38] link community quality of life with the way in which community factors, resources and services are experienced by community members and influence their life quality or assist them in their everyday interactions. More recently, Rastegar et al. [9] report that sociability and social interactions can improve peoples’ quality of life in areas of conflicting economic trends, i.e. in areas where economic development is coupled with harsh socio-economic inequalities.

Owing to such evidence, trust is regarded as, perhaps the most important component of social capital and one that can foster economic growth and well-being, health and life satisfaction [8, 42, 43]. In turn, subjective well-being is found to reflect societal progress and the overall civic institutions development of countries [44]. To that extent, we test here for the effect of institutional trust on people’s subjective life satisfaction evaluations. In particular, our second hypothesis is:

H2: Life satisfaction is positively affected by trust in institutions.

Our third hypothesis draws from the research strand that analyses safety (and/or crime) as one of the most important parameters affecting peoples’ wellbeing evaluations. As Moser [45] suggests, the congruity between people and their residential environment is a critical parameter of human well-being and social sustainability as it refers to the relationship between life satisfaction and objective standards of living. Studies of community quality of life have for long focused on issues such as traffic and crime [21, 46]. The research strand that focuses on urban quality of life for example, evolved under the premise that places are an organic whole wherein objective and subjective quality of life domains interact and structure citizens’ satisfaction with life and their choices [20, 47, 48]. Increasing research is devoted to the issue as a number of studies integrate this important aspect in empirical evaluations of quality of life. Węziak-Białowolska [19] reports that, a high percentage of people who are satisfied with safety in their city is positively associated with a high percentage of citizens who are more satisfied with life in a city. Macke et al. [49] study the issue in the case of Curitiba city, in Southern Brazil, and identify four main quality of life (QOL) domains, namely, socio-structural relationships, environmental well-being, material well-being and community integration. Similarly, cross-European evidence of the determinants of urban quality of life suggest that the external environment and public services, and the social and economic characteristics of the neighbourhood complement the socio-demographic determinants of self-reported quality of life in European cities [20].

On the other hand, there is increasing research that focuses on crime and the estimation of the social and economic costs that it bears to societies [50, 51]. Thus, the crime-related quality-of-life losses have also been the focus of many studies. For example, Lynch and Rasmussen [52] analyse house prices variations as a result of crime, while [53] analyses the interrelationship between fear of victimisation and neighbourhood deterioration. Moore [23] reports the impact of fear on happiness and proposes a way to measure the economic value of reducing fear. Crime (and fear-of crime) alters the daily routine of people and constraints social interactions that could otherwise help them build networks of solidarity and cohesiveness [54]. Empirical evidence verifies that victimisation increases the avoidance behaviour of people and their life satisfaction levels [55,56,57]. McCrea et al. [58] analyse satisfaction with urban living and argue that there exists an indirect impact of neighbourhood satisfaction to overall life satisfaction, as neighbourhood satisfaction depends on neighbourhood interaction and perceived crime. Visser et al. [59] analyse fear of crime and feelings of unsafety in 25 European countries and report that both contextual- and individual-level effects are at play albeit in varying forms. Crime is found to affect fear of crime but not feelings of unsafety. Other factors that induce both fear of crime and feelings of unsafety are the lower social protection expenditures, lower social trust and institutional (police) trust levels and perceived ethnic threat. So, the overall costs of crime are multidimensional and appear in both tangible and intangible forms. Tangible costs are perhaps easier to identify and measure as they refer to additional resources that are needed in order for a person and a society to effectively deal with crime. Crime induces changes in a person’s everyday behaviour, e.g. use of one’s own car or a taxi instead of walking or using public transportation, a fact that increases, in turn, the economic burden of crime [3]. On the other hand, intangible costs also arise from losses related to the emotional and physical effects of crime and from changes in the behaviour of the person, his/her view of the society and health-related psychological costs [50, 51]. Thus, the ‘fear of crime’ component is responsible for important quality of life losses as well [50].

Here we use the notion of distance, as manifested in modern social structures, in order to capture the various socio-economic and well-being effects of crime (and fear-of-crime) [16]. In viewing social space as a macro level structure that shapes the judgements, choices and achievements of all people, Lianos [60] suggests that it is social relations that structure societies and the position of individuals in them. In such social terrain, different types of capital (economic, cultural and social) interact in order to determine hierarchy and power, in short the endpoint of a person in the social ladder [59, 61]. We suggest that a person’s socio-economic and cultural distance reflects upon life satisfaction levels and thus it might be a more insightful measure of peoples’ sociability and the structural base of a modern society. In particular, we test the following hypothesis:

H3: Life satisfaction is affected by the socio-economic and cultural distance of individuals from their environment.

In the case of all three hypotheses, we expect to observe mixed results. That is, we expect positive and/or negative effects to appear as a result of peoples’ preferences and evaluations of their living conditions and how they should be.

3 The Hybrid TOPSIS-Entropy Methods

The Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) first introduced by Hwang and Yoon [26]. Since then, it is largely used to deal with the ranking problem of alternatives from the best to worst like the problem presented in this paper. The main advantage of the method is its capability to provide both positive and negative ideal solutions and subsequently to evaluate the alternatives based on indexes called closeness to the positive ideal solution and remoteness from the negative ideal solution. The chosen alternative should have the shortest distance from the ideal solution and the farthest from the negative ideal solution.

The basis of the method is the decision matrix \({Q}_{mn}=\{{Q}_{ij}|i=\mathrm{1,2}, \dots ,m \;;\quad j=\mathrm{1,2},\dots ,n\}\) including ratings of considered alternatives \(i=1, 2,\dots ,m\) in the context of the accepted criteria \(j=1, 2,\dots n\). On the basis of which normalized ratings of particular alternatives are calculated by:

The aim of the normalization is to transform various criteria dimensions into non dimensional ones allowing thus comparisons. In most cases, the criteria are measured in different scales making the comparisons across them difficult.

In order to take into consideration, the difference in importance that the criteria exhibit the normalized decision matrix is calculated by:

where \({w}_{j}\) devotes the weight of the \({j}^{th}\) criterion.

The next step is the determination of the positive ideal and the negative ideal solutions. The goal of this step is to identify the positive ideal alternative (extreme performance on each criterion) and the negative ideal alternative (reverse extreme performance on each crit erion). The se values are calculated as:

where \({J}^{+}\) and \({J}^{-}\) represent the set of benefit and cost criteria respectively.

The separation value is then estimated. The separation value represents the distance of each normalised score of alternatives \(i\) from each of the aforementioned cases (ideal positive and negative points). It is calculated using the following formulas:

Finally, the ranking the coefficient of the alternatives are estimated with respect to \({d}_{i}^{+}\) and \({d}_{i}^{-}\) as:

The set of the alternatives are then ranked by the descending order of the value of \({R}_{i}\).

A significant factor that heavily affects the above mentioned estimation procedure is the determination of the weight for the criteria. The selection of appropriate weights can be based either on the evaluator’s own assessment or on more sophisticated methodologies such as the Delphi method and the Gray correlation degree method and or on other multicriteria techniques such as AHP. The main disadvantage of these is the fact that they rely on the subjective assessments of the decision makers.

In this study and in order to overcome this obstacle the entropy method [60] is employed. The main advantage of the method is that the calculation of the weights is not based on subjective assessments of evaluators but on the inherent information contained in the scores of alternatives for each of the criteria. Therefore, its computational process leads to the extraction of objective weights.

At the empirical level, we test for the validity of H1–H3 by means of proposing a different way in order to account for the effect that different objective and subjective living parameters exert upon citizens’ life satisfaction, utilising the above-mentioned methodology.

In view of that, H1 is meant to control for (a) the demographic profile and the social-economic status of individuals (criterion 1.1), (b) their external environment (objective living conditions and subjective evaluations of them) (criterion 1.2) and (c) their preferences with respect to living conditions (criterion 1.3). H2 is meant to account for institutional trust as the basis of well-functioning modern civil societies. The three trust criteria account for the role of (a) the information society (criterion 2.1), (b) the safety/security institutions (criterion 2.2) and (c) the political institutions (criterion 2.3). Finally, H3 is meant to account for distance as the outcome of individual and aggregate level priorities in the social, economic and cultural sphere of people’s lives. The three distance criteria are (a) social distance (criterion 3.1), (b) economic distance (criterion 3.2) and (c) cultural distance (criterion 3.3).

Finally, we test the sensitivity of our results by estimating our TOPSIS ranking weights for particular sub-groups as derived with respect to key control variables, namely, gender, age class, education level and household composition. Results indicate the presence of different life satisfaction profiles thus supporting the analytical validity of our approach and findings.

4 Data and Variables

We use data from two sources, namely, Eurobarometer data and statistical data from the Hellenic Police. From the Standard Eurobarometer Survey, we use the 2018 dataset for Greece which refers to a sample of 1012 observations [41]. From this dataset, we extract all the information that is needed in order to approximate or calculate the individual level variables. The regional crime levels and type of crime variables (aggregate variables) are drawn from the Hellenic Police official website. These data refer to the crime rate and the percentage of foreign crime for 10 Greek regions (NUTS II level).

Table 1 analytically presents the measurement of all variables included in the analysis as well as some basic descriptive statistics. Figure 1 illustrates the overall crime rates for each of the 10 Greek regions (NUTS II). We use regional crime rates with 1 year lag and for ease of comparison the number of total reported crimes has been normalised on a 0–1 scale. In 2017, the region of Western Makedonia reports the lowest crime rate (0) and the region of Attica the highest (1).

Our dependent variable is an ordinal variable reporting quality of life evaluations in a 4-point Likert-type scale. In this scale, 1 accounts for individuals that have reported being not at all satisfied with their life while 4 denotes individuals that have reported being very satisfied with their life. In general, positive quality of life evaluations (i.e. very or fairly satisfied with life) account for 45.9% of responses and negative evaluations (i.e. not very or not at all satisfied with life) account for 54.1% of responses. Table 1 analytically presents the frequencies for each category of responses.

The independent variables have been divided into three level 1 criteria and nine level 2 sub-criteria referring to individual level characteristics, trust and distance variables. In particular, the three level 1 individual characteristics criteria account for:

-

(1.1) the demographic profile of individuals (I1), namely, age (measured in five categories), gender (dummy variable taking the value of 1 for male respondents), education (measured in five categories), household composition (married couple and children in the family, measured in five categories), social class (self-assessments, measured in five categories) and the economic status of individuals (calculated as the respondents’ economic profile status, i.e. Greek nationality, employed and homeownership, weighted for difficulties in paying bills; recoded into five categories)

-

(1.2) the external environment of individuals (I2), namely, subjective living conditions (calculated as the average of peoples’ assessments of a number of welfare status criteria, including public services, security, solidarity, the welfare state, entrepreneurship, liberalisation and globalisation; recoded into five categories) and objective living conditions (calculated as the normalised regional crime rates in the past year (2017) and weighted by size of the respondent’s community and foreign crime rates; recoded into five categories)

-

(1.3) the peoples’ preferences with respect to their living conditions (I3), namely, attachment (calculated as the average of feelings about immigration from EU, outside the EU and immigrants’ contribution to the economy weighted by the respondents’ attachment to place; recoded into five categories)

The three level 2 criteria with respect to trust account for:

-

(2.1) the role of trust in the information society (T1) (calculated as the weighted average of democratic accountability (my voice counts in my country), knowledge (I understand what is going on) and trust in media variables; recoded into five categories)

-

(2.2) the role of trust in the safety/security institutions (T2) (calculated as the sum of trust in justice/legal system, police and the army; recoded into four categories)

-

(2.3) the role of trust in the political institutions (T3), namely, national and supranational political power actors (calculated as the sum of the respondents’ trust in political parties, national government, national parliament, public administration, regional/local public authorities, European Union; recoded into five categories)

Finally, the three level 3 criteria with respect to distance account for distance or proximity of one’s own priorities (at the social, economic and political values domains) with respect to the priorities that individuals report (assess) as important for the country as a whole (social, economic) and the EU level (political). Values of these criteria are calculated as the distance between country/EU reported priority (0–1) and personal level priority (0–1). The calculated variables take values from −1 to 2 (where −1 = important at the personal level, 0 = non-important at both levels, 1 = important at the country level, 2 = important at both the country/EU and the personal level). After appropriate recoding, we adopt a 0 to 3 scale (where 0 = no importance, 1 = important for person, 2 = important for country/EU, 3 = important for both person and country/EU) and our variables take higher values the more close a person’s own prioritisation is to that of his/her prioritisation for the country/EU. In particular, the three level 3 criteria with respect to distance account for:

-

(3.1) Social distance (D1), average of distance between country reported priority and personal level priority with respect to crime, terrorism, housing, immigration, health and social security, education, environment (recoded into five categories)

-

(3.2) Economic distance (D2), average of distance between country reported priority and personal level priority with respect to economic situation, prices, taxation and unemployment (recoded into five categories)

-

(3.3) Cultural distance (D3), average of distance between EU reported priority and personal level priority with respect to norms/values, namely, rule of law, respect human life, respect human rights, individual freedom, democracy, peace, equality, solidarity, tolerance, religion and culture (recoded into five categories)

5 Results and Discussion

Using the proposed multicriteria technique, we obtain our first categorisation of factors in terms of their importance with respect to life satisfaction (Table 2). In this categorisation, we see that the four most important (with equal importance) factors are place attachment, trust (information society and safety institutions) and cultural distance (rank positions 1–4). Household composition follows as the fifth most important factor. The least important factors are gender, objective living conditions, political institutions, social distance, social status and subjective living conditions. Of moderate importance are the age, education, economic status and economic distance variables. Based on these results, we might argue that when the socio-demographic and economic profile characteristics of individuals are controlled for, preferences about one’s living conditions, trust, distance and household composition are found to be the most important determinants of life satisfaction levels. In the context of the present study, preferences with regard to living conditions account for peoples’ viewpoint towards migration and the role of place attachment. In light of our research aim, these results suggest that life satisfaction increases in magnitude the higher a person’s bonds are to physical and social place.

In order to test for the possible presence of different life satisfaction profiles as suggested by the available knowledge in the field, we have proceeded with a number of alternative ranking estimations with respect to gender, age, education, household composition and social status (Table 3). An interesting finding is that the ranking of some life satisfaction factors changes in the case of all these variables despite that only the household composition variable has been found to be a highly ranked life satisfaction determinant. In particular, the following should be noted.

5.1 With Regard to Gender

Gender is ranked in the last position of life satisfaction determinants. This holds for the benchmark model (Table 2) and for all alternative estimations (Table 3). However, when estimations are based on gender the ranking of life satisfaction determinants changes significantly. A different pattern is observed. When results are obtained with regard to gender then, economic status is found to be the most important life satisfaction determinant (ranked 1st), followed by the household composition variable (ranked 2nd). Positions 3 to 7 (rank 5) are now held by a set of five factors, namely, place attachment, trust (information society and safety institutions) and distance (economic and cultural).

5.2 With Regard to Age

Age is found to be a moderate determinant of life satisfaction. Ranked from the 7th (the highest) to the 10th (the lowest) position, it may be considered a second level, in terms of importance, parameter. However, when age is removed from the analysis the ranking of life satisfaction determinants again changes. Cultural distance is the most important parameter (ranked 1st) followed by place attachment, trust (information society, safety institutions) in the positions 2 to 4 (ranked 3rd) and economic status (ranked 5th). When education, household condition and social class are removed from the ranking then age increases in importance due to its correlation with all these parameters.

5.3 With Regard to Education

The effect of education is found similar to that of age. In that sense, it may be considered a parameter of moderate importance (ranked for the 6th to the 8th position). However, when education is excluded from the ranking criteria, we see a ranking of determinants that is very close to the initial ranking (R1) and to the ranking that is produced in the case of age (R3). Again, cultural distance is the most important parameter (ranked 1st) followed by place attachment, trust (information society, safety institutions) in the positions 2 to 4 (ranked 3rd) and household composition (ranked 5th). Education seems to retain a stronger relationship with age and household condition as it gets its highest ranking when these two factors are excluded from the life satisfaction criteria.

5.4 With Regard to Household Condition

The effect of household condition is also notable (R4). In the absence of this particular criterion, cultural distance and trust in the form of information are found to hold the first two positions while economic status is ranked 3rd and positions 4 and 5 are held by place attachment and trust (safety).

5.5 With Regard to Social Class

Social class also changes the relative importance of the various ranking criteria (R5). It is quite interesting that when removed from the list of criteria we see the household composition variable to rank in the 1st position while the importance of place attachment and trust (information society) is again reported (positions 2 to 3). Cultural distance and economic status are the variables ranked in the 4th and 5th positions, respectively.

Overall, we find that our empirical results provide support to the hypotheses proposed here. Not only does life satisfaction depend upon a number of institutional and societal features such as trust and distance, but also the effect of these parameters is found to be rather strong and one that is verified in the case of alternative model estimations. To that extent, we might argue that important policy insights are provided by the analytical approach proposed here. First, the relevant importance of formal institutions and other informal networks wherein ties are developed and used might be identified. If we are to develop informed policy measures such fields of life satisfaction priorities are most relevant. In addition, we have an approach that can be effectively applied to secondary data and provide valuable results. Third, important insights are provided with regard to Greece for which no relevant studies exist. The determinants of life satisfaction is a least researched issue in the case of Greece despite of its importance for evaluating peoples’ well-being, on the one hand, and the continuous enhancement of the multicultural character of the Greek society in the last decades, on the other. Available knowledge is limited to the studies of Lambropoulou [62] and Zarafonitou [12, 63] which focus on the impact of crime and victimisation in Greece. Lambropoulou [64] examines the effect of policing as a mechanism establishing the sense of security and trust that is needed in order for small firms to expand their activities. Zarafonitou [63] focuses on the continuously changing social environment of Greece and reports citizens’ dissatisfaction with safety/security institutions (e.g. those responsible for designing the country’s penal policy or protecting citizens from the increasing crime rates). In addition, Zarafonitou [12] points to the low victimisation but high fear of crime ‘paradox’, a fact that reveals the many different manifestations of risk as resulting for the interrelationships among multiple individual and contextual factors.

In verifying the importance of individual perceptions of risk on life satisfaction, we provide evidence of how sustainable organisations of the future might succeed in the provision of social goods. Furthermore, applying multicriteria tools in the analysis of social features such as lack of trust and increased distance levels among the members of a society allows for a more integrative approach to the study of societal phenomena. Practical implications for policy makers in the field are important as critical knowledge is provided from a new methodological approach. Future research in the field might focus on the long-term dynamics underlying the phenomena analysed here and the construction of social goods as peoples’ perceptions of them are not static. Shifts in the perception of risks, related to for example crime, disorder and incivilities, might alter the way a person views his/her surroundings [65]. The study of shifting perceptions is relevant for Greece as well. To that extent, the results of the present study might be considered as a valuable basis for future investigations in the field.

6 Conclusion

The challenges that modern societies are faced with have caused increased attention to be placed on the study of a number of diverse socio-economic and cultural factors of modern environments. Life satisfaction is considered to reflect peoples’ subjective evaluations of the risk that various economic, social, political and environmental conditions might exert upon their well-being. Here we focus on institutional trust and distance as determinants of peoples’ assessments of life satisfaction. Bringing together knowledge from different strands of research, we develop a set of empirical hypotheses and test for their analytical validity using appropriate multicriteria techniques. We consider trust and distance as key societal features that reflect institutions and their environment, and we test for their effect of subjective life satisfaction evaluations using case study data for Greece. Our empirical results provide support to the proposed hypotheses. After controlling for the socio-demographic and economic profile of respondents, we provide support for the role of trust in institutions and feelings of distance as determinants of life satisfaction. Important policy level implications are derived on the basis of these findings. Improvements in life satisfaction might be seen as policy interventions that aim at improving civil society institutions. Interventions might involve formal and/or informal institutions that affect both objective (e.g. safety) and subjective (e.g. feelings of safety) quality of life judgements.

In conclusion, we argue that important policy level insights are derived from the proposed analysis. Furthermore, the proposed approach can be a useful tool for analysing this relationship in the case of different countries or groups of countries as well.

Future research can extend the analysis by considering additional criteria to the proposed evaluation framework and using other MCDM methods for more accurate sensitivity analysis. Another research direction in which this study can extend is the consideration of group decision-making during the evaluation of the factors affecting citizens’ life satisfaction. The concept of life satisfaction is wide and therefore the opinion of experts from different areas is needed. Thus, the implementation of a decision support system which will incorporate and other MCDM methods and will allow the decision-makers to compare the results obtained and to collaborate will be of great interest.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

References

Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 95:542–575

Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S (1985) The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 49(1):71–75

Diener E, Inglehart R, Tay L (2013) Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Soc Indic Res 112(3):497–527

Hagerty MR, Cummins R, Ferriss AL, Land K, Michalos AC, Peterson M, Vogel J (2001) Quality of life indexes for national policy: review and agenda for research. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 71(1):58–78

Cummins RA (2005) The domains of life satisfaction: an attempt to order chaos. In: Michalos AC (ed) Citation classics from Social Indicators Research. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 559–584

Graafland J, Lous B (2019) Income inequality, life satisfaction inequality and trust: a cross country panel analysis. J Happiness Stud 20(6):1717–1737

Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N (1999) (eds) Well-being: the foundations of hedonic psychology. New York, Russell Sage Foundation

Michalos AC (2013) Essays on the quality of life vol 19. Springer Science & Business Media

Rastegar M, Hatami H, Mirjafari R (2017) Role of social capital in improving the quality of life and social justice in Mashhad. Iran Sustainable Cities and Society 34:109–113

Unanue W, Gómez ME, Cortez D, Oyanedel JC, Mendiburo-Seguel A (2017) Revisiting the link between job satisfaction and life satisfaction: the role of basic psychological needs. Front Psychol 8:680

Gale F P (2018) The political economy of sustainability. Edward Elgar Publishing

Zarafonitou C (2009) Criminal victimisation in Greece and the fear of crime: a ‘paradox’ for interpretation. Int Rev Vict 16(3):277–300

Ramia I, Voicu M (2020) Life satisfaction and happiness among older Europeans: the role of active ageing. Soc Indic Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02424-6

Siegrist M, Gutscher H, Earle TC (2005) Perception of risk: the influence of general trust, and general confidence. J Risk Res 8(2):145–156

Fathi M, Khakifirooz M, Pardalos P M (eds) (2019) Optimization in large scale problems: Industry 4.0 and Society 5.0 applications vol 152. Springer Nature

Lianos M (ed) (2016) Dangerous others, insecure societies: fear and social division. Routledge

Helliwell JF, Putnam RD (2004) The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions-Royal Society of London series B Biological Sciences 359:1435–1446

Veenhoven R (1995) The cross-national pattern of happiness: test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Soc Indic Res 34(3):33–68

Węziak-Białowolska D (2016) Quality of life in cities–empirical evidence in comparative European perspective. Cities 58:87–96

Morais P, Camanho AS (2011) Evaluation of performance of European cities with the aim to promote quality of life improvements. Omega 39(4):398–409

Myers D (1988) Building knowledge about quality of life for urban planning. J Am Plann Assoc 54(3):347–358

Sujarwoto S, Tampubolon G, Pierewan AC (2018) Individual and contextual factors of happiness and life satisfaction in a low middle income country. Appl Res Qual Life 13:927–945

Moore SC (2006) The value of reducing fear: an analysis using the European Social Survey. Appl Econ 38(1):115–117

Oshio T, Kobayashi M (2010) Income inequality, perceived happiness, and self-rated health: evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Soc Sci Med 70:1358–1366

Liern V, Pérez-Gladish B, Rubiera-Morollón F et al (2021) Residential choice from a multiple criteria sustainable perspective. Ann Oper Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04480-8

Ortega-Momtequín M, Rubiera-Morollón F, Pérez-Gladish B (2021) Ranking residential locations based on neighbourhood sustainability and family profile. Int J Sust Dev World 28(1):49–63

Cummins RA (1997) Assessing quality of life. In: Brown R I (ed) Quality of life for people with disabilities: models, research and practice, 2nd edn., Stanley Thornes Publishers: Cheltenham, UK, pp 116–150

Helliwell JF (2006) Well-being, social capital and public policy: what’s new? Econ J 116:C34–C45

Baumann D, Ruch W, Margelisch K, Gander F, Wagner L (2020) Character strengths and life satisfaction in later life: an analysis of different living conditions. Appl Res Qual Life 15(2):329–347

Ruggeri K, Garcia-Garzon E, Maguire Á, Matz S, Huppert FA (2020) Well-being is more than happiness and life satisfaction: a multidimensional analysis of 21 countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18(1):1–16

Shannon CE (2001) A mathematical theory of communication. ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review 5(1):3–55

Bhuiyan MF, Szulga RS (2017) Extreme bounds of subjective well-being: economic development and micro determinants of life satisfaction. Appl Econ 49(14):1351–1378

Becchetti L, Massari R, Naticchioni P (2013) The drivers of happiness inequality: suggestions for promoting social cohesion. Oxf Econ Pap 66(2):419–442

Purvis B, Mao Y, Robinson D (2019) Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain Sci 14(3):681–695

Vandebroeck D (2018) Toward a European social topography: the contemporary relevance of Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of ‘social space.’ Eur Soc 20(3):357–358

Bjørnskov C, Dreher A, Fischer JAV (2010) Formal institutions and subjective well-being: revisiting the cross-country evidence. Eur J Polit Econ 26:419–430

Park J, Joshanloo M, Scheifinger H (2020) Predictors of life satisfaction in Australia: a study drawing upon annual data from the Gallup World Poll. Aust Psychol 55(4):375–388

Serag El Din H, Shalaby A, Farouh HE, Elariane SA (2013) Principles of urban quality of life for a neighbourhood. HBRC Journal 9(1):86–92

Anheier HK, Stares S, Grenier P (2004) Social capital and life satisfaction. In: Arts W, Halman L (eds) European values at the turn of the millennium, Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands, pp 81–107

Kroll C (2008) Social capital and the happiness of nations. The importance of trust and networks for life satisfaction in a cross-national perspective. Bruxelles/Frankfurt a.M./New York/Oxford, Peter Lang Publishing

Elgar FJ, Davis CG, Wohl MJ, Trites SJ, Zelenski JM, Martin MS (2011) Social capital, health and life satisfaction in 50 countries. Health Place 17(5):1044–1053

Kubiszewski I, Zakariyya N, Costanza R (2018) Objective and subjective indicators of life satisfaction in Australia: how well do people perceive what supports a good life? Ecol Econ 154:361–372

Oishi S, Kesebir S, Diener E (2011) Income inequality and happiness. Psychol Sci 22(9):1095–1100

Hwang CL, Yoon K (1981) Methods for multiple attribute decision making in multiple attribute decision making. Lecture notes in economics and mathematical systems, vol 186. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Moser G (2009) Quality of life and sustainability: toward person–environment congruity. J Environ Psychol 29(3):351–357

Lambiri D, Biagi B, Royuela V (2007) Quality of life in the economic and urban economic literature. Soc Indic Res 84(1):1–25

Das D (2008) Urban quality of life: a case study of Guwahati. Soc Indic Res 88(2):297–310

Lotfi S, Solaimani K (2009) An assessment of urban quality of life by using analytic hierarchy process approach (case study: comparative study of quality of life in the north of Iran). J Soc Sci 5(2):123–133

Macke J, Casagrande RM, Sarate JAR, Silva KA (2018) Smart city and quality of life: citizens’ perception in a Brazilian case study. J Clean Prod 182:717–726

Dolan P, Loomes G, Peasgood T, Tsuchiya A (2005) Estimating the intangible victim costs of crime. Br J Criminol 45:958–976

Dolan P, Peasgood T (2007) Estimating the economic and social costs of the fear of crime. Br J Criminol 47(1):121–132

Lynch AK, Rasmussen DW (2001) Measuring the impact of crime on house prices. Appl Econ 33:1981–1989

Gibbons S (2004) The costs of urban property crime. Econ J 114:441–463

Liska AE, Warner BD (1991) Functions of crime: a paradoxical process. Am J Sociol 96(6):1441–1463

Cohen MA (2008) The effect of crime on life satisfaction. J Leg Stud 37:325–353

Hanslmaier M, Kemme S, Baier D (2016) Victimization, fear of crime and life satisfaction. In: Baier D, Pfeiffer C (eds) Representative studies on victimization: research findings from Germany. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co, KG, pp 253–284

Michalos AC, Zumbo BD (2000) Criminal victimisation and the quality of life. Soc Indic Res 50:245–295

McCrea R, Stimson R, Western J (2005) Testing a moderated model of satisfaction with urban living using data for Brisbane-South East Queensland. Soc Indic Res 72:121–152

Visser M, Scholte M, Scheepers P (2013) Fear of crime and feelings of unsafety in European countries: macro and micro explanations in cross-national perspective. Sociol Q 54(2):278–301

Lianos M (2018) Universal social determination. Eur Soc 20(3):359–374

Bourdieu P (1985) The social space and the genesis of groups. Theory Soc 14(6):723–744

Lambropoulou E (2004) Citizens’ safety, business trust and Greek police. Int Rev Adm Sci 70(1):89–110

Zarafonitou C (2004) Local crime prevention councils and the partnership model in Greece. Safer Communities 3(1):23–28

Lambropoulou E (2005) Crime, criminal justice and criminology in Greece. Eur J Criminol 2(2):211–247

Link NW, Kelly JM, Pitts JR, Waltman-Spreha K, Taylor RB (2017) Reversing broken windows: evidence of lagged, multilevel impacts of risk perceptions on perceptions of incivility. Crime Delinq 63(6):659–682

Funding

Open access funding provided by HEAL-Link Greece.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daskalopoulou, I., Karakitsiou, A. & Malliou, C. A Multicriteria Analysis of Life Satisfaction: Assessing Trust and Distance Effects. Oper. Res. Forum 3, 59 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43069-022-00170-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43069-022-00170-8