Abstract

The study examines the effects of the dark triad traits (i.e., psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism) on positive word-of-mouth (WOM) intention for luxury products, and the moderating role of others’ opinion divergence (i.e., whether or not a consumer’s opinion deviates from that of the reference group). An experiment with 208 respondents tested the research hypotheses, shedding light on the moderating role of others’ opinion divergence in the relationship between each of the three dark triad traits and positive WOM intention. Results showed that psychopathy is positively (negatively) related to positive WOM intention in the presence (absence) of others’ opinion divergence. Moreover, narcissism is positively related to positive WOM intention when others’ opinion divergence is absent. Finally, Machiavellianism is negatively related to positive WOM intention when others’ opinion divergence is present. These results extend current knowledge on the influence of the dark triad traits on positive WOM intention about luxury products, offering insights for segmentation and targeting strategies in the luxury market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the context of luxury purchases, word-of-mouth (WOM) recommendations serve as an essential source of information for consumers (Kim & Ko, 2012; Kowalczyk & Mitchell, 2022), driving more than 60% of individual purchase decisions (Savenier, 2015).

However, not all consumers are equally inclined to share WOM about luxury products, given the potential social costs associated with conspicuous displays of luxury consumption (Cannon & Rucker, 2019). Indeed, a growing trend among luxury consumers involves using subtler cues to communicate their ownership of luxury items, in contrast to overt and conspicuous displays (Eckhardt et al., 2015). Luxury marketers, therefore, face a challenge in identifying consumers who might be willing to engage in WOM.

This study contributes to this domain by examining the role of personality traits as predictors of WOM transmission in a luxury context, with a specific focus on positive WOM. While existing literature provides some insight into how personality traits might predict such WOM, for example, highlighting the influence of high need for status (Yang and Mattila, 2017) and need for uniqueness (Kauppinen-Räisänen et al., 2018), there is an unexplored terrain concerning the potential impact of darker personality traits, such as Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy, collectively known as the dark triad (Jonason & Webster, 2010).

Our study aims to address this gap and investigate how these dark triad traits might influence positive WOM in a luxury context. Despite some research linking narcissism to WOM (e.g., Luarn et al., 2016; Saenger et al., 2013), no studies have examined the collective impact of all three dark triad traits on WOM. Notably, these traits have been associated with externalized luxury consumption, involving the conspicuous display of luxury possessions to gain social status (Guido et al., 2020), suggesting that consumers with dark triad personalities might be particularly inclined to discuss their luxury possessions with others.

At the same time, the dark triad traits are conceptually distinct and operate differently in terms of status-seeking strategies. Narcissism is associated with self-promotion (Sedikides et al., 2007), while psychopathic or Machiavellian personalities may resort to manipulative or aggressive tactics (Rauthmann & Kolar, 2013; Verbeke et al., 2011). The latter strategies are more socially deviant than self-promotion and would typically thrive under more hostile social conditions (Reidy et al., 2007). For instance, such strategies could be activated when a consumer’s opinion diverges from the opinion of others in a group conversation as such situations could create a hostile opinion climate (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018).

Based on the above, this study investigates opinion divergence, i.e., whether a consumer’s opinion aligns or diverges from the reference group’s one, as a moderator in the relationship between dark triad traits and the intention to share positive WOM about luxury products. Indeed, opinion divergence is highly relevant to luxury products as they evoke strong emotions (Kyrousi & Theodoridis, 2019), resulting in a mix of positive and negative opinions within group discussions (Amatulli et al., 2020). This can make luxury consumers hesitate to engage in WOM sharing as they might fear sanctions from others. Therefore, it is imperative for luxury marketers to identify consumers who are willing to share positive WOM even when their opinions differ from the majority.

This article proposes that the three dark traits may differently contribute to explaining consumers’ WOM intention, depending on the presence or absence of opinion divergence. For instance, consumers with psychopathic personalities, known for dominance and aggression-based strategies in their pursuit of status (Lilienfeld et al., 2012), might view opinion divergence as an opportunity to gain status rather than a risk. In contrast, consumers with narcissistic personalities, focused on self-promotion and ego protection, may be more inclined to share positive WOM when their opinions align with the group consensus. Additionally, consumers with Machiavellian personalities, characterized by manipulation and exploitation (Wastell & Booth, 2003), might resist sharing positive WOM when their opinions differ from the group, as a strategy to appear more likable and ingratiating.

Our findings make three contributions to the literature. First, this research is the first to examine the complete set of dark triad traits as possible predictors of positive WOM. Second, this research provides new insights on who might share positive WOM in a group setting involving divergent opinions (Cascio et al., 2015; Ryu & Han, 2009; Schlosser, 2005). Third, this research suggests a more complex status-seeking process underlying positive WOM sharing, which involves consumers’ sensitivity to divergent others’ opinion.

Practically, our work suggests that luxury marketers should view dark triad consumers as potential assets in spreading positive WOM. In particular, narcissistic consumers, with their propensity to engage in luxury-based WOM across contexts, may be valuable advocates. In contrast, psychopathic consumers could play a more distinctive role, being targeted as WOM advocates in situations involving divergent opinions, particularly in the context of online communication characterized by polarization and divergence (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018).

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Dark triad and WOM in the luxury context

The dark triad describes a set of personality traits – i.e., psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism – that in combination “entail a socially malevolent character with behavior tendencies toward self-promotion, emotional coldness, duplicity, and aggressiveness” (Paulhus & Williams, 2002, p. 557). They are often associated with reduced morality (Campbell et al., 2009; Egan et al., 2015), lower empathy (Jonason & Kroll, 2015), and a range of maladaptive behaviors such as drug abuse, criminality, and bullying/harassing (Azizli et al., 2016). Despite such a similarity, research has revealed that these three personality traits are conceptually distinct, each possessing a unique set of characteristics (Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Psychopathy is characterized by lack of emotion, callous social attitudes, remorselessness, and impulsive thrill seeking (Jonason et al., 2015; Paulhus & Williams, 2002). People with this trait lack empathy, have little respect for rules and are remorseless (Hare & Neumann, 2008). Narcissism includes characteristics such as perceived superiority, dominance, extreme vanity, self-absorption, and a sense of entitlement (Raskin & Terry, 1988). People with this trait have an overly enhanced view of the self and take every opportunity to enhance those views, often at the expense of others (Hollebeek et al., 2022; Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Machiavellianism is instead characterized by insincerity, manipulativeness, emotional detachment, and a willingness to exploit others for personal purposes (Wastell & Booth, 2003). People with this trait typically demonstrate strategic planning and suspicion of others, employ various social strategies to deceive and manipulate others for personal gains and exploitative intents (Jonason & Webster, 2010; Moudrý & Thaichon, 2020; Rauthmann, 2011).

In the consumer context, the dark triad has been linked to various dysfunctional consumer behaviors, such as benefiting from illegal actions (Egan et al., 2015), consumer fraud (Harrison et al., 2018), supporting cruel business practices (Karampournioti et al., 2018), or misbehaving at restaurants (Chaouali et al., 2022). We examine whether consumers scoring high on the dark triad instead might play a more functional consumer role by transmitting positive WOM. A literature review of dark triad as predictors of WOM (see Table 1) shows that narcissism is related to WOM communication in a few studies (Kirk et al., 2022; Luarn et al., 2016; Moisescu et al., 2022; Saenger et al., 2013; Taylor, 2020), but the effects of psychopathy and Machiavellianism are still ignored. Kapoor et al. (2021) examined all the three dark traits as predictors of exaggeration in online WOM, which is a more dysfunctional form of WOM, and Hancock et al. (2023) examined the dark traits in relation to negative WOM. Only Blair et al. (2022) examined the dark triad in relation to positive WOM, but combined all three traits in one construct, thus giving no insight into how each dark trait might influence positive WOM distinctly. Hence, there is a need for research on how the distinct dark triad traits might influence positive WOM.

This study suggests that each of the dark triad traits is related to positive WOM in luxury context due to their common relationship with status seeking (Dahling et al., 2009; Glenn et al., 2017; Grapsas et al., 2020). Status seeking involves pursuing relative higher positions in society compared to other people, in order to gain respect, admiration, and power (Glenn et al., 2017). One common approach dark consumers use to gain such positions is through externalized luxury consumption, which essentially consists in buying luxury products to impress others by showing off such purchases (Guido et al., 2020). Luxury purchases indeed signal wealth and prestige, and would grant consumers with admiration and respect from others (Nelissen & Meijers, 2011). Hence, by showing off such a type of purchases to other people, dark consumers’ perceived status would likely increase. In this situation, sharing WOM about luxury purchases would be a useful way for such consumers to inform others about their increased status (Lee et al., 2019; Loureiro et al., 2018). Indeed, Blair et al. (2022) show that dark consumers are more likely to recommend products when the product is hedonic (vs. utilitarian) as this could influence their status and prestige. Therefore, this study assumes that consumers with the dark triad traits will have a higher propensity to transmit luxury-based WOM as this aligns with their status-seeking motive. Formally, we suggest that:

H1

All three dark triad traits are positively related to the intention to share positive WOM.

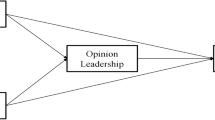

In the next section, we discuss how this effect might be moderated by opinion divergence in group conversations (see conceptual model in Fig. 1).

2.2 Consumer reactions to others’ opinion

Previous consumer research suggests that individuals in a group context would generally behave in ways that conform to social norms or pressure (Ryu & Han, 2009). This would help them achieve certain intangible rewards, in terms of group acceptance and social inclusion (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004), and avoid penalties, in terms of social disapproval, rejection, and ridicule (Miller & Anderson, 1979). The tendency to conform has a strong impact on opinion formation in group discussions, often causing the minority to follow the majority opinion (Glynn et al., 1997). Accordingly, when consumers encounter divergent others’ opinions about a product, they often change their own opinion of the product in accordance with the conversation partners’ (Brannon & Samper, 2018). Consumers’ tendency to conform also affects their WOM behavior. For instance, consumers often revise their recommendations to be consistent with others’ recommendations when they hear that these latter are different from their initial recommendations (Cascio et al., 2015). And, sometimes, consumers’ tendency to conform may result in a lower willingness to talk when others’ opinions are divergent with their own (Ryu & Han, 2009).

The effect of others’ opinion divergence on WOM seems particularly prominent when the divergent opinion of the reference group in a conversational context is negative as opposed to positive (Schlosser, 2005). One possible explanation for this effect is that individuals who receive product information via WOM communications are more likely to attribute negative information to the product being mentioned, whereas they tend to attribute positive information to the communicator’s personal motives (e.g., impression management), which often have little to do with the product’s actual performance (Chen & Lurie, 2013). Therefore, consumers who consider sharing positive, as opposed to negative, opinions about a product would be more sensitive, and thus more inclined to change their initial opinions or resist sharing them at all, if they are aware that potential recipients hold a divergent, negative opinion about the same product. Another possible explanation is that consumers in general perceive individuals holding a critical or negative opinion about a product as more intelligent (Schlosser, 2005). Consequently, consumers confronted with a situation in which most of potential recipients share a divergent, negative opinion about a product would often adjust their positive opinions downward to align with such recipients or avoid voicing their opinions at all (Glynn et al., 1997; Ryu & Han, 2009).

However, in opposition to this general tendency to conform, some consumers might instead be more motivated to talk when their opinion diverges from others’. For instance, consumers with an individualistic self-view (Wien & Olsen, 2014) or with a high need for uniqueness (Dayan, 2020) show higher intention to engage in WOM when they hold a divergent opinion. For these consumers, challenging social norms could serve to differentiate themselves from others, thus enhancing their status (Bellezza et al., 2014). Hence, these consumers might view a situation in which their opinion diverges from others’ opinion as an opportunity to gain status and not a potentially risky situation.

In this research, we argue that consumers with a dark personality may be less inclined to conform to others’ opinion, thus challenging social norms (Azizli et al., 2016; Paulhus & Williams, 2002) and ignoring social risks, such as that of receiving criticisms or that of being stigmatizing as incompetent consumers (Vize et al., 2018), in an attempt to increase their status (Visser et al., 2014). While at first glance this would suggest that all three dark traits could be associated with an increased intention to engage in WOM to share personal product opinions in the presence of others’ opinion divergence, some significant differences might emerge among the different dark consumers’ WOM intentions, depending on their preferred strategy to seek status, as well as the perceived risk of ego threat. In the following sections, we hypothesize how these aspects would affect consumers’ intention to share WOM, when others’ opinion divergence is present rather than absent, for each of the three dark traits.

2.3 Psychopathy and divergent others’ opinion

Psychopaths desire status in the form of a relatively higher position in society compared to other people (Glenn et al., 2017) and try to obtain this by engaging in risky behaviors (Visser et al., 2014), expressing boldness (Persson & Lilienfeld, 2019), or trying to dominate other people (Lilienfeld et al., 2012). Psychopaths tend to be hostile in their dominance over others (Rauthmann & Kolar, 2013), showing almost no empathy for their “victims” (Jonason & Kroll, 2015). Psychopaths would also be more impulsive in their risky behaviors compared to individuals with the other two dark traits, thinking less about the consequences of such behaviors (Jones & Paulhus, 2011). In other words, psychopaths seek status through dominating others using a hostile and aggressive tactics and by engaging in reckless behaviors. This conceptualization suggests that psychopathy could be positively related to communicating a divergent WOM opinion. By challenging the consensus in a group, they get the opportunity to dominate the situation by using hostile tactics such as force or intimidation. They also get to show their boldness by exposing themselves to the risks associated with not conforming to the group.

In addition, individuals with a psychopathic trait are relatively insensitive to others’ criticisms, and are drawn to risk, even though it involves what others would consider punishment (Foster et al., 2009). For instance, they might engage in risky gambling at the detriment of someone else, even if this involves the risk of being punished (Jones, 2014). They are also less likely to care about what others think of them (Glenn et al., 2017). This insensitivity to punishment and what others think about them, combined with having a dominant, aggressive, and risk-seeking approach to status-achievement, might motivate consumers high in psychopathy to share their own opinion about luxury products through WOM especially when this opinion diverges from the one held by others in the conversational group. In contrast, the absence of such opinion divergence would give less opportunity to aggress and dominate other people. Such a situation indeed removes the central foundations in psychopathic consumers’ status pursuit. This should reduce psychopaths’ motivation to share WOM, presumably leading to a negative relationship between psychopathy and intention to share positive WOM about luxury products. This leads to the following hypotheses:

H2a

In the presence of others’ opinion divergence, psychopathy is positively related to intention to share positive WOM.

H2b

In the absence of others’ opinion divergence, psychopathy is negatively related to intention to share positive WOM.

2.4 Narcissism and divergent others’ opinion

Narcissism is the dark trait mostly associated with status-seeking behavior (Grapsas et al., 2020). A central approach that narcissists use to obtain status is to portray themselves as unique (Ohmann and Burgmer, 2016). For instance, they buy exclusive, prestigious, and scarce products to promote a sense of uniqueness (Lee et al., 2013). They are also more likely to take advantage of product customization solutions to create individualized products for themselves (De Bellis et al., 2016). This desire for uniqueness even affects their cognitive processing, leading them to focus predominately on differences when making comparisons among people or objects (Ohman and Burgmer, 2016). Hence, narcissists should presumably be attracted to situations in which they can communicate how they diverge from others. At the same time, narcissists are highly sensitive toward environmental cues that convey hindrances to their status pursuit (Grapsas et al., 2020). Such a hindrance would, for instance, be a situation in which they could sense a risk of being derogated by others, causing an ego threat (Foster et al., 2009). Voicing a divergent opinion in a group context would presumably evoke some form of ego threat, in particular when the others in the group have a negative opinion. Hence, despite the potential chance of achieving status by communicating a positive opinion about luxury products that diverges from the dominant one in the reference group, narcissistic consumers might be cautious about sharing such WOM. Indeed, Park and Kang (2013) showed that narcissism could lead to lower willingness to share WOM when narcissistic consumers fear that it might cause embarrassment or other negative self-presentational consequences. We expect that such fear of ego-threat would be more dominant than the motive to seek status through divergent opinion sharing, resulting in a negative association between narcissism and intention to share positive WOM about luxury products in the presence of others’ opinion divergence.

However, when others’ opinion divergence is absent, the risk of ego-threat should disappear. In that case, we propose that narcissists’ strong drive to self-promote could dominate their behavioral inclinations, leading to a higher intention to share positive WOM about luxury products, which would allow them to bask in the approval they receive from others. Hence, the following hypothesis is offered:

H3a

In the presence of others’ opinion divergence, narcissism is negatively related to intention to share positive WOM.

H3b

In the absence of others’ opinion divergence, narcissism is positively related to intention to share positive WOM.

2.5 Machiavellianism and divergent others’ opinion

Machiavellianism is also associated with status seeking behaviors (Dahling et al., 2009). Yet, compared to narcissists, Machiavellian individuals would not seek status by trying to impress others (Rauthmann, 2011). They are also less aggressive and impulsive than psychopaths (Jones & Paulhus, 2010), and would not seek status by trying to dominate others (Rauthmann, 2012). Instead, Machiavellians would engage in more “sneaky” social manipulation, using social skills such as bluff or charm to obtain status and other personal benefits (Verbeke et al., 2011). This may, for instance, involve looking for situations that allow them to cheat without being caught (Shultz, 1993), or ingratiate themselves with their bosses in order to hide their mediocre performance (Verbeke et al., 2011). They are also more likely to falsely express the same opinions as others to make them more likeable with other people (Hogue et al., 2013). Accordingly, Machiavellian individuals prefer to use indirect influence tactics that are difficult to detect, often applying positive emotional tactics (e.g., friendliness, flattery) to get their will, rather than being straightforward and rational in their attempts to influence others (Grams & Rogers, 1990). These characteristics seem incongruent with explicitly challenging the consensus in a group, such as when sharing a divergent WOM opinion.

In addition, Machiavellian individuals are generally reluctant to exhibit weaknesses, vulnerability, and imperfection to others (Sherry et al., 2006); and, due to their negativistic and cynical beliefs (Rauthmann & Will, 2011), they often expect negative outcomes in social interactions. Therefore, they engage in high levels of protective self-monitoring (Abell & Brewer, 2014) to detect potential threats to their self-interest (Jones & Paulhus, 2009). Accordingly, Machiavellian individuals should presumably be highly attentive to the potential risks associated with sharing a divergent WOM opinion. Machiavellians are also reluctant to take unnecessary risks when the rewards are not sufficient (Fehr et al., 1992). Therefore, we expect they would find it safer to protect themselves from the risk of sharing WOM rather than exploit the situation for potential status rewards. This reasoning translates into the prediction of a negative relationship between Machiavellianism and intention to share positive WOM in the presence of others’ opinion divergence.

In contrast, in the absence of others’ opinion divergence, Machiavellian individuals should be less concerned about negative social outcomes. This should remove some of their reluctance to share their opinions via WOM. Furthermore, since these individuals are less concerned about self-promotion (Rauthmann, 2011), they would not necessarily have a stronger drive than any other type of consumer to give positive WOM. Therefore, in such a situation, Machiavellianism should be unrelated to intention to share WOM. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4a

In the presence of others’ opinion divergence, Machiavellianism is negatively related to intention to share positive WOM.

H4b

In the absence of others’ opinion divergence, Machiavellianism is not related to intention to share positive WOM.

3 Methods

3.1 Design and procedure

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a between-subjects experiment by manipulating others’ opinion divergence and assessing the other constructs involved in the conceptual model displayed in Fig. 1. We developed a structured online questionnaire that was administered, in winter 2020, to a sample of 208 U.S. respondents via Amazon’s MTurk (age range: 19–70, MAge = 36.37, SDAge = 11.23; 47% females). Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two others’ opinion divergence conditions (absent vs. present) and thus asked to read a scenario that varied across these conditions. The scenario asked respondents to imagine that they had just received an offer for their dream job and that, to celebrate the event, they decided to buy a Rolex watch that they had desired for a long time. Rolex watches were chosen as the experimental product stimulus for this the study as it is one of the best-known luxury brands (Zhan & He, 2012) that has already used in experimental studies on luxury consumption (De Angelis et al., 2017). Next, the scenario asked respondents to imagine that, later that day, they logged on to Facebook and scrolled through the news feed, seeing that some of their friends were discussing luxury watches. Participants in others’ opinion divergence absent condition read that their friends held positive opinions about Rolex watches and mentioned positive aspects of these watches. In contrast, those in the others’ opinion divergence present condition read that their friends held negative opinion about Rolex watches and mentioned negative aspects for this product. Next, in both the conditions the scenario asked participants to imagine that, a week later, they went to a party where they met some of their Facebook friends who were engaged in a conversation about Rolex watches. Afterward, participants were asked to indicate their intention to share positive WOM about that luxury product by using four items adapted from Eisingerich et al. (2015) (Table 2). Participants’ responses on these items were assessed on a seven-point rating scale (1 = extremely unlikely, 7 = extremely likely).

Respondents were then asked to complete the dark triad scale by Jonason and Webster (2010), which assessed psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism. The scale consisted of twelve items, four for each dark trait, assessed on a seven-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Finally, a manipulation check item measured on a five-point scale (i.e., “Based on the situation you just read about, how concerned would you be that others at the party would perceive you negatively if you told them about your new Rolex watch?; 1 = not at all concerned, 5 = extremely concerned) assessed the ego threat reactions generated by the different experimental conditions, as our central assumption was that opinion divergence would cause ego threat among consumers. As expected, participants in the others’ opinion divergence present condition indicated higher levers of ego threat (M = 2.64, SD = 1.33) than those in the others’ opinion divergence absent condition (M = 1.88, SD = 1.21; F(1, 206) = 19.02, p < .001).

3.2 Empirical analysis and results

Data were analyzed in two steps. First, we checked our multi-item measures for reliability through a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Then, we conducted a path analysis to investigate the relationships among the relevant constructs. To test our three hypotheses, we implemented a multigroup analysis, which implied spitting our overall sample of respondents in two subgroups based on the assigned condition (absence vs. presence of others’ opinion divergence). Each subgroup comprised 104 participants.

3.2.1 Measures’ reliability check

We checked the reliability of the measures employed in the study to assess the independent and dependent variables using a CFA (Table 1). Taken together, the fit statistics were adequate: χ2(98) = 254.326, p < .001; χ2/d.f. = 2.595; CFI = 0.941; NFI = 0.908; SRMR = 0.063. Convergent validity for the measurement model is ensured since each construct showed satisfactory levels of construct reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). Also, discriminant validity was ensured since AVE indices were higher than 0.50 and, for each construct, the square root of the corresponding AVE was higher than the correlation between the construct and any other construct included in the model (see Table 3; Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

3.2.2 Path analysis

We conducted a path analysis in which psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism served as the independent variables, while intention to share positive WOM was the dependent variable. Taken together, fit statistics were acceptable: χ2(1) = 5.448, p = .020; χ2/d.f. = 5.448; CFI = 0.951; NFI = 0.944; SRMR = 0.058. The results revealed a nonsignificant relationship between psychopathy (standardized structural parameter β = 0.12, p = .10) and Machiavellianism (β = − 0.10, p = .17), on one hand, and intention to share positive WOM, on the other. Instead, there was a significant and positive relationship between narcissism and WOM intention (β = 0.33, p < .001) (see Fig. 2, Panel A). This set of findings partially supported H1.

A multigroup analysis was conducted to test whether the relationships between the three dark triad traits and intention to share positive WOM varied in magnitude or significance as a function of whether others’ opinion divergence was absent or present, as predicted in our hypotheses (see Fig. 2, Panel B, and Panel C). The multigroup analysis compared a constrained model (with invariant parameters across the two subgroups) against the unconstrained model (with parameters free to change across the subgroups). The fit statistics for the constrained model were: χ2(5) = 37.012, p < .001; χ2/d.f. = 7.402; CFI = 0.744; NFI = 0.730; SRMR = 0.120; for the unconstrained model these statistics were: χ2(2) = 6.751, p = .034; χ2/d.f. = 3.376; CFI = 0.962; NFI = 0.951; SRMR = 0.042. The χ2 difference test between the constrained and unconstrained model reached significance (∆χ2(3) = 30.261, p < .001), suggesting that the parameters are not invariant across the two experimental conditions. This information, combined with a CFI that is higher for the unconstrained model than for the constrained model (∆CFI = 0.218 > 0.010; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), led us to conclude that the former model performed better than the latter one and, thus, the relationships between the three dark triad traits and intention to share positive WOM could significantly vary as a function of whether others’ opinion divergence was absent or present.

As predicted in H2a and H2b, psychopathy was negatively related to intention to share positive WOM in the absence of others’ opinion divergence (β = − 0.28, p = .003), and positively related to this intention in the presence of others’ opinion divergence (β = 0.43, p < .001). In line with H3b, narcissism was positively related to intention to share positive WOM in the absence of others’ opinion divergence (β = 0.51, p < .001). However, narcissism was not significantly related to this intention in the presence of others’ opinion divergence (β = 0.18, p = .064), giving no support to H3a. In line with H4a and H4b, Machiavellianism was negatively related to intention to share positive WOM when others’ opinion divergence was present (β = − 0.22, p = .028), whereas it was unrelated to this intention when others’ opinion divergence was absent (β = 0.08, p = .404) (see Fig. 2, Panel B, and Panel C). Table 4 presents the structural coefficients, regarding the relationships between the three dark traits and WOM intention, as estimated within each of the two experimental conditions (absence vs. presence of others’ opinion divergence), along with the respective pairwise comparison test. The obtained z-test values were greater than 1.96 (ps < 0.05), thus confirming our predictions.

4 Discussion

This study examined how the dark triad personality traits relate to consumers’ intention to share positive WOM about luxury products, and how such relationship varies as a function of whether or not the dominant opinion in the conversational group is divergent. Our empirical findings revealed that such personality traits play a determining role and, thus, could be taken into consideration in order to design more effective segmentation and targeting strategies.

Contrary to our initial expectations, the results displayed a nonsignificant relationship between psychopathy and the intention to share positive WOM. This finding suggests that individuals exhibiting psychopathic tendencies may not be significantly inclined to engage in positive WOM behaviors. However, it is worth noticing that, while the relationship was not statistically significant, the positive beta coefficient suggests a potential trend towards a positive association. This implies that further research (e.g., using larger samples) may be required to fully understand the potential influence of psychopathy on positive WOM intentions. Similarly, our results also revealed a nonsignificant relationship between Machiavellianism and the intention to share positive WOM. This finding suggests that individuals characterized by a Machiavellian trait may not be significantly motivated to engage in positive WOM behaviors.

In contrast to psychopathy and Machiavellianism, the analysis uncovered a significant and positive relationship between narcissism and the intention to share positive WOM. This finding suggests that individuals with higher levels of narcissism are more likely to engage in positive WOM behaviors. This set of findings align with previous research that found narcissism to be associated with self-promotion and seeking positive attention from others.

Overall, the differential relationship among the three dark triad traits and WOM intention provide valuable insights into the nuanced nature of their influence on consumer behavior. More specifically, our findings showed that consumers with higher levels of psychopathy are more likely to share WOM in the presence of others’ opinion divergence, whereas they are less likely to engage in WOM when such opinion divergence is absent. Those with higher levels of narcissism are more likely to share WOM only when their own opinion is aligned with that of potential recipients in a given conversational setting. Instead, narcissism is unrelated to WOM intention under the presence of others’ opinion divergence. Finally, consumers with higher levels of Machiavellianism are less likely to share WOM when others’ opinion is divergent, whereas this dark trait is unrelated to WOM intention when others’ opinion divergence is absent.

4.1 Theoretical implications

This research contributes to literature in three primary ways. First, while previous research has focused on narcissism as the sole dark personality trait capable of predicting consumers’ intention to engage in WOM (Saenger et al., 2013; Taylor, 2020), our research is the first to examine how all the three dark triad traits might influence WOM intention. This approach showed that, besides narcissism, also psychopathy and Machiavellianism have a role. In particular, the positive effect that emerged for psychopathy when others’ opinion in the conversational setting was divergent seems relevant in the light of current consumers’ opinion landscape, which is increasingly characterized by polarization and divergence (Neubaum & Krämer, 2018). Psychopathy might indeed play a critical role in those conversational settings in which speaking up would require confronting others, possibly at the risk of being attacked or viewed as less intelligent. Such controversial WOM conversations seem particularly likely to occur for luxury products, as people often hold negative prejudices about these products and thus form negative impressions that generate a negative public opinion about them (Kyrousi & Theodoridis, 2019). In such situations, consumers with higher levels of psychopathy might serve as advocates for luxury products. This finding might also provide some nuance to the personality theory that suggests that psychopathy primarily plays a dysfunctional consumer role (e.g., Egan et al., 2015; Harrison et al., 2018; Karampournioti et al., 2018). Instead, psychopathy could play a positive role for luxury marketers seeking to stimulate WOM in polarized opinion landscapes.

Second, our research extends current knowledge about WOM sharing in a group setting involving divergent opinions (Cascio et al., 2015; Ryu & Han, 2009; Schlosser, 2005). The prevailing logic in social influence is that individuals tend to conform to the dominant opinion in a group conversation (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). Based on this logic, consumers who hold a divergent opinion within the reference group would remain silent to avoid negative social consequences (Glynn et al., 1997). Our results showed that this notion should not be taken for granted as certain consumers – namely, those higher in psychopathy – might prefer speaking up in the presence (as compared to absence) of others’ opinion divergence. This finding contributes to the existing stream of studies (Dayan, 2020; Wien & Olsen, 2014) showing that consumers might be more inclined to share WOM in the presence (vs. absence) of others’ opinion divergence out of their need for uniqueness. Despite the plausibility of such a need for uniqueness account, our results suggest the existence of another explanation, based on psychopathy, for consumers’ increased intention to share positive WOM about luxury products in conservational settings characterized by the presence of others’ opinion divergence.

Third, our research contributes to the research stream on the role of status in sharing WOM about luxury products. Prior studies (Lee et al., 2019; Loureiro et al., 2018) essentially showed that an opportunity to achieve status rewards, in the form of prestige, may drive consumers’ intention to share WOM about luxury products. As all the three dark traits are logically connected with status, one could argue that all these traits might be positively related to WOM. Contrary to this intuition, our results showed that the dark triad traits are differently related to WOM intention, thus suggesting that status pursuit from giving WOM is a more complex process that depends on important individual differences. These individual differences refer to the three dark traits, which reasonably impact the particular strategy consumers adopt to achieve status and their sensitivity to ego threat in different social contexts.

4.2 Practical implications

From a practical point of view, our findings offer useful insights for luxury companies. For example, in situations where public opinion tends to be homogeneous, and thus opinion divergence tends to be absent, luxury companies could pay particular attention to narcissistic consumers by assuring them the best luxury product experiences possible, in order to encourage them to spread positive WOM. Companies could also try to encourage WOM among such consumers by using advertising messages that appeal to the emotion of pride. Such messages should resonate with the narcissists’ status-seeking motive, and as such, trigger these consumers to share luxury-based WOM (Septianto et al., 2021). In contrast, in situations where public opinion is heterogenous, and thus opinion divergence is present, luxury companies should focus on consumers higher in psychopathy by pampering them with positive luxury product experiences in order to get these consumers to serve as brand advocates. Machiavellian consumers are less inclined to share positive WOM when opinion divergence is present and seems insensitive to this opportunity when opinion divergence is absent. Therefore, this consumer segment does not seem of particular relevance to luxury companies interested in promoting WOM among their customers.

4.3 Limitations and future research

Our study has some limitations that open avenues for future research. First, our study used a scenario-based approach in which the participants had to imagine themselves in a hypothetical consumption situation. There is no guarantee that participants’ responses to the scenario would be the same as to an equivalent real-world situation. Therefore, future studies could try to replicate our results in real or realistic consumption situations. Second, our study could be related to social desirability. Since the dark triad traits are related to dysfunctional and norm-breaking behaviors, consumers might be reluctant to identify themselves with such traits. Especially, Machiavellians are motivated to act in socially desirable ways (Jones & Paulhus, 2009), which might make them disposed to lie on self-report measures of personality. To overcome this issue, future studies could adopt peer-ratings of the dark triad instead of self-reports. Third, our manipulation-check measure assessed respondents’ ego threat reaction to the assigned scenario. Although the assessment of this reaction was functional to our theorizing, future research could check whether our manipulation affect respondents’ perception of opinion divergence. Furthermore, in line with prior studies that directly assessed perceived ego threat (e.g., Frey-Cordes et al., 2020), future research could insert this variable in the model to estimate its possible impact on consumers’ WOM intention. Fourth, as our study considered luxury products, future investigations could assess respondents’ income and use it as control variable in the statistical analysis. Fifth, as we only focused on positive WOM, future research should also study how the dark triad might affect negative WOM in a luxury context.

Future studies could also assess whether the relationship between the dark triad traits and WOM activity still holds for non-luxury products, and whether our results hold across different countries and, more generally, across distinct cultural contexts. Finally, future studies could try to explore cause-effect relationships between the dark traits and WOM intention by implementing appropriate experimental techniques that corroborate our findings.

References

Abell, L., & Brewer, G. (2014). Machiavellianism, self-monitoring, self-promotion and relational aggression on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior,36, 258–262.

Amatulli, C., De Angelis, M., Pino, G., & Guido, G. (2020). An investigation of unsustainable luxury: How guilt drives negative word-of-mouth. International Journal of Research in Marketing,37(4), 821–836.

Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., Chin, K., Vernon, P. A., Harris, E., & Veselka, L. (2016). Lies and crimes: Dark triad, misconduct, and high-stakes deception. Personality and Individual Differences,89, 34–39.

Bellezza, S., Gino, F., & Keinan, A. (2014). The red sneakers effect: Inferring status and competence from signals of nonconformity. Journal of Consumer Research,41 No(1), 35–54.

Blair, J. R., Gala, P., & Lunde, M. (2022). Dark triad-consumer behavior relationship: The mediating role of consumer self-confidence and aggressive interpersonal orientation. Journal of Consumer Marketing,39(2), 145–165.

Brannon, D. C., & Samper, A. (2018). Maybe I just got (Un) lucky: One-on-one conversations and the malleability of post-consumption product and service evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research,45(4), 810–832.

Campbell, J., Schermer, J. A., Villani, V. C., Nguyen, B., Vickers, L., & Vernon, P. A. (2009). A behavioral genetic study of the Dark Triad of personality and moral development. Twin Research and Human Genetics,12(2), 132–136.

Cannon, C., & Rucker, D. D. (2019). The dark side of luxury: Social costs of luxury consumption. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,45(5), 767–779.

Cascio, C. N., O’Donnell, M. B., Bayer, J., Tinney, F. J., & Falk, E. B. (2015). Neural correlates of susceptibility to group opinions in online word-of-mouth recommendations. Journal of Marketing Research,52(4), 559–575.

Chaouali, W., Hammami, S. M., Veríssimo, J. M. C., Harris, L. C., El-Manstrly, D., & Woodside, A. G. (2022). Customers who misbehave: Identifying restaurant guests acting out via asymmetric case models. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,66, 102897.

Chen, Z., & Lurie, N. H. (2013). Temporal contiguity and negativity bias in the impact of online word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research,50(4), 463–476.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,9(2), 233–255.

Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology,55, 591–621.

Dahling, J. J., Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The development and validation of a new Machiavellianism scale. Journal of Management,35(2), 219–257.

Dayan, O. (2020). The impact of need for uniqueness on word of mouth. Journal of Global Marketing,33(2), 125–138.

De Angelis, M., Adıgüzel, F., & Amatulli, C. (2017). The role of design similarity in consumers’ evaluation of new green products: An investigation of luxury fashion brands. Journal of Cleaner Production,141, 1515–1527.

De Bellis, E., Sprott, D. E., Herrmann, A., Bierhoff, H. W., & Rohmann, E. (2016). The influence of trait and state narcissism on the uniqueness of mass-customized products. Journal of Retailing,92(2), 162–172.

Eckhardt, G. M., Belk, R. W., & Wilson, J. A. (2015). The rise of inconspicuous consumption. Journal of Marketing Management,31, 7–8.

Egan, V., Hughes, N., & Palmer, E. J. (2015). Moral disengagement, the dark triad, and unethical consumer attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences,76, 123–128.

Eisingerich, A. B., Chun, H. H., Liu, Y., Jia, H. M., & Bell, S. J. (2015). Why recommend a brand face-to-face but not on Facebook? How word-of-mouth on online social sites differs from traditional word-of-mouth. Journal of Consumer Psychology,25(1), 120–128.

Fehr, B., Samsom, D., & Paulhus, D. L. (1992). The construct of Machiavellianism: Twenty years later. In C. D. Spielberger, & J. N. Butcher (Eds.), Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 1.9, pp. 77–116). Erlbaum.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research,18(1), 39–50.

Foster, J. D., Shenesey, J. W., & Goff, J. S. (2009). Why do narcissists take more risks? Testing the roles of perceived risks and benefits of risky behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences,47(8), 885–889.

Frey-Cordes, R., Eilert, M., & Büttgen, M. (2020). Eye for an eye? Frontline service employee reactions to customer incivility. Journal of Services Marketing,34(7), 939–953.

Glenn, A. L., Efferson, L. M., Iyer, R., & Graham, J. (2017). Values, goals, and motivations associated with psychopathy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,36(2), 108–125.

Glynn, C. J., Hayes, A. F., & Shanahan, J. (1997). Perceived support for one’s opinions and willingness to speak out: A meta-analysis of survey studies on the spiral of silence. Public Opinion Quarterly,61(3), 452–463.

Grams, W. C., & Rogers, R. W. (1990). Power and personality: Effects of Machiavellianism, need for approval, and motivation on use of influence tactics. Journal of General Psychology,117(1), 71–82.

Grapsas, S., Brummelman, E., Back, M. D., & Denissen, J. J. (2020). The why and how of narcissism: A process model of narcissistic status pursuit. Perspectives on Psychological Science,15(1), 150–172.

Guido, G., Amatulli, C., Peluso, A. M., De Matteis, C., Piper, L., & Pino, G. (2020). Measuring internalized versus externalized luxury consumption motivations and consumers’ segmentation. Italian Journal of Marketing,1(1), 25–47.

Hancock, T., Waites, S. F., Johnson, C. M., & Stevens, J. L. (2023). How do Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy tendencies influence consumer avoidance and revenge-seeking following a service failure? Journal of Consumer Marketing,40(6), 721–733.

Hare, R. D., & Neumann, C. S. (2008). Psychopathy as a clinical and empirical construct. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology,4, 217–246.

Harrison, A., Summers, J., & Mennecke, B. (2018). The effects of the dark triad on unethical behavior. Journal of Business Ethics,153(1), 53–77.

Hogue, M., Levashina, J., & Hang, H. (2013). Will I fake it? The interplay of gender, Machiavellianism, and self-monitoring on strategies for honesty in job interviews. Journal of Business Ethics,117 No(2), 399–411.

Hollebeek, L. D., Sprott, D. E., Urbonavicius, S., Sigurdsson, V., Clark, M. K., Riisalu, R., & Smith, D. L. G. (2022). Beyond the big five: The effect of machiavellian, narcissistic, and psychopathic personality traits on stakeholder engagement. Psychology & Marketing,39(6), 1230–1243.

Jonason, P. K., & Kroll, C. H. (2015). A multidimensional view of the relationship between empathy and the dark triad. Journal of Individual Differences,36(3), 150–156.

Jonason, P. K., Strosser, G. L., Kroll, C. H., Duineveld, J. J., & Baruffi, S. A. (2015). Valuing myself over others: The Dark Triad traits and moral and social values. Personality and Individual Differences,81, 102–106.

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment,22(2), 420.

Jones, D. N. (2014). Risk in the face of retribution: Psychopathic individuals persist in financial misbehavior among the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences,67, 109–113.

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 93–108). Guilford.

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2010). Different provocations trigger aggression in narcissists and psychopaths. Social Psychological and Personality Science,1(1), 12–18.

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2011). The role of impulsivity in the Dark Triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences,51(5), 679–682.

Kapoor, P. S., Balaji, M. S., Maity, M., & Jain, N. K. (2021). Why consumers exaggerate in online reviews? Moral disengagement and dark personality traits. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,60, 102496.

Karampournioti, E., Hennigs, N., & Wiedmann, K. P. (2018). When pain is pleasure: Identifying consumer psychopaths. Psychology & Marketing,35(4), 268–282.

Kauppinen-Räisänen, H., Björk, P., Lönnström, A., & Jauffret, M. N. (2018). How consumers’ need for uniqueness, self-monitoring, and social identity affect their choices when luxury brands visually shout versus whisper. Journal of Business Research,84, 72–81.

Kim, A. J., & Ko, E. (2012). Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. Journal of Business Research,65(10), 1480–1486.

Kirk, C. P., Peck, J., Hart, C. M., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Just my luck: Narcissistic admiration and rivalry differentially predict word of mouth about promotional games. Journal of Business Research,150, 374–388.

Kowalczyk, C. M., & Mitchell, N. A. (2022). Understanding the antecedents to luxury brand consumer behavior. Journal of Product & Brand Management,31(3), 438–453.

Kyrousi, A. G., & Theodoridis, P. K. (2019). Consumers against luxury brands: Towards a research agenda. In A. Kavoura, E. Kefallonitis, & A. Giovanis (Eds.), Strategic innovative marketing and tourism (pp. 1007–1014). Springer.

Lee, H., Jang, Y., Kim, Y., Choi, H. M., & Ham, S. (2019). Consumers’ prestige-seeking behavior in premium food markets: Application of the theory of the leisure class. International Journal of Hospitality Management,77, 260–269.

Lee, S. Y., Gregg, A. P., & Park, S. H. (2013). The person in the purchase: Narcissistic consumers prefer products that positively distinguish them. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,105(2), 335.

Lilienfeld, S. O., Patrick, C. J., Benning, S. D., Berg, J., Sellbom, M., & Edens, J. F. (2012). The role of fearless dominance in psychopathy: Confusions, controversies, and clarifications. Personal Disorders,3(3), 327–340.

Loureiro, S. M. C., Maximiano, M., & Panchapakesan, P. (2018). Engaging fashion consumers in social media: The case of luxury brands. International Journal of Fashion Design Technology and Education,11(3), 310–321.

Luarn, P., Huang, P., Chiu, Y. P., & Chen, I. J. (2016). Motivations to engage in word-of-mouth behavior on social network sites. Information Development,32(4), 1253–1265.

Miller, C. E., & Anderson, P. D. (1979). Group decision rules and the rejection of deviates. Social Psychology Quarterly,42(4), 354–363.

Moisescu, O. I., Dan, I., & Gică, O. A. (2022). An examination of personality traits as predictors of electronic word-of‐mouth diffusion in social networking sites. Journal of Consumer Behaviour,21(3), 450–467.

Moudrý, D. V., & Thaichon, P. (2020). Enrichment for retail businesses: How female entrepreneurs and masculine traits enhance business success. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services,54, 102068.

Nelissen, R. M., & Meijers, M. H. (2011). Social benefits of luxury brands as costly signals of wealth and status. Evolution and Human Behavior,32(5), 343–355.

Neubaum, G., & Krämer, N. C. (2018). What do we fear? Expected sanctions for expressing minority opinions in offline and online communication. Communication Research,45(2), 139–164.

Ohmann, K., & Burgmer, P. (2016). Nothing compares to me: How narcissism shapes comparative thinking. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 162–170.

Park, S. Y., & Kang, Y. J. (2013). What’s going on in SNS and social commerce? Qualitative approaches to narcissism, impression management, and e-WOM behavior of consumers. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science,23(4), 460–472.

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality,36(6), 556–563.

Persson, B. N., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2019). Social status as one key indicator of successful psychopathy: An initial empirical investigation. Personality and Individual Differences,141, 209–217.

Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,54(5), 890–902.

Rauthmann, J. F. (2011). Acquisitive or protective self-presentation of dark personalities? Associations among the Dark Triad and self-monitoring. Personality and Individual Differences,51(4), 502–508.

Rauthmann, J. F. (2012). The Dark Triad and interpersonal perception: Similarities and differences in the social consequences of narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Social Psychological and Personality Science,3(4), 487–496.

Rauthmann, J. F., & Kolar, G. P. (2013). Positioning the Dark Triad in the interpersonal circumplex: The friendly-dominant narcissist, hostile-submissive machiavellian, and hostile-dominant psychopath? Personality and Individual Differences,54(5), 622–627.

Rauthmann, J. F., & Will, T. (2011). Proposing a multidimensional machiavellianism conceptualization. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal,39(3), 391–403.

Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., Miller, J. D., & Martinez, M. A. (2007). Psychopathy and aggression: Examining the role of psychopathy factors in predicting laboratory aggression under hostile and instrumental conditions. Journal of Research in Personality,41(6), 1244–1251.

Ryu, G., & Han, J. K. (2009). Word-of-mouth transmission in settings with multiple opinions: The impact of other opinions on WOM likelihood and valence. Journal of Consumer Psychology,19(3), 403–415.

Saenger, C., Thomas, V. L., & Johnson, J. W. (2013). Consumption-focused self-expression word of mouth: A new scale and its role in consumer research. Psychology & Marketing,30(11), 959–970.

Savenier, A. S. (2015). “Study: Behavior of Luxury Consumers Around the World Becoming More and More Complex”, FashionMag. https://www.albatrosscx.com/en/behavior-of-luxury-consumers-becoming-more-complex.

Schlosser, A. E. (2005). Posting versus lurking: Communicating in a multiple audience context. Journal of Consumer Research,32(2), 260–265.

Sedikides, C., Gregg, A. P., Cisek, S., & Hart, C. M. (2007). The I that buys: Narcissists as consumers. Journal of Consumer Psychology,17(4), 254–257.

Septianto, F., Seo, Y., & Errmann, A. C. (2021). Distinct effects of pride and gratitude appeals on sustainable luxury brands. Journal of Business Ethics,169(2), 211–224.

Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Klein, C. (2006). Machiavellianism, trait perfectionism, and perfectionistic self-presentation. Personality and Individual Differences,40(4), 829–839.

Shultz, C. J. (1993). Situational and dispositional predictors of performance: A test of the hypothesized machiavellianism structure interaction among sales persons. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,23(6), 478–498.

Taylor, D. G. (2020). Putting the self in selfies: How narcissism, envy and self-promotion motivate sharing of travel photos through social media. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing,37(1), 64–77.

Verbeke, W. J., Rietdijk, W. J., van den Berg, W. E., Dietvorst, R. C., Worm, L., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2011). The making of the machiavellian brain: A structural MRI analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Psychology and Economics,4(4), 205–216.

Visser, B. A., Pozzebon, J. A., & Reina-Tamayo, A. M. (2014). Status-driven risk taking: Another dark personality? Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science,46(4), 485–496.

Vize, C. E., Lynam, D. R., Collison, K. L., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Differences among dark triad components: A meta-analytic investigation. Personality disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment,9(2), 101–111.

Wastell, C., & Booth, A. (2003). Machiavellianism: An alexithymic perspective. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,22(6), 730–744.

Wien, A. H., & Olsen, S. O. (2014). Understanding the relationship between individualism and word of mouth: A self-enhancement explanation. Psychology & Marketing,31(6), 416–425.

Yang, W., & Mattila, A. S. (2017). The impact of status seeking on consumers’ word of mouth and product preference—A comparison between luxury hospitality services and luxury goods. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research,41(1), 3–22.

Zhan, L., & He, Y. (2012). Understanding luxury consumption in China: Consumer perceptions of best-known brands. Journal of Business Research,65(10), 1452–1460.

Funding

Open access funding provided by UiT The Arctic University of Norway (incl University Hospital of North Norway). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wien, A.H., Peluso, A.M., Pichierri, M. et al. Effects of the dark triad on word of mouth in the luxury context: the moderating role of opinion divergence. Ital. J. Mark. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00088-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00088-x