Abstract

Due to the complexity of postmodern markets, firms are developing corporate heritage marketing initiatives to engage in consumer research for emotional ties. Due to its rising relevance in the literature, several aspects of corporate heritage marketing need to be examined in depth, especially within the b2b context. This study explores how corporate heritage marketing supports the initiation phase of the buyer–seller relationship. The originality of this study relies on the fact that, thus far, no studies have discussed the connection between corporate heritage marketing and buyer–seller relationship initiation, a crucial period for the establishment of the business relationship, which in turn has been scarcely investigated in the management literature. The findings suggest that corporate heritage marketing might act as an initiation contributor for the buyer–seller relationship: it facilitates the first contacts between the parties by conveying emotional and rational values that improve seller attractiveness, and the first formal agreement after primary interactions by increasing seller trustworthiness. This study contributes to the corporate heritage marketing and buyer–seller relationship development literature. Relevant managerial implications are also provided, suggesting a simplified model for the SMEs for corporate heritage marketing management along with advice for buyers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

With the increasing complexity of postmodern markets, where the emotional aspects of consumption have become the main research features, firms are mindfully valorising their corporate heritage to fulfil customer and stakeholder research to anchors that offer certainty in a world of uncertainty (Balmer, 2011; Riviezzo et al., 2021). Corporate heritage marketing (CHM) aims to enhance the history of a firm and affirms its uniqueness to create a relational fulcrum with stakeholders and customers. The literature recognises the ability of CHM to communicate firms’ solidity, authenticity, and credibility (Garofano et al., 2020) emotional elements that b2b partners are seeking during the very first stages in buyer–seller relationship initiation (Lynch & De Chernatony, 2004).

The conventional view of organizational buying behaviour as a rational process has been challenged in recent literature, which highlights the importance of emotions in the b2b context (Andersen & Kumar, 2006; Kemp et al., 2018; Pandey & Mookerjee, 2018). In the early phase of buyer–seller relationship initiation, decision makers lack knowledge of the benefits, costs, and future perspective of the emerging relationship; consequently, they seek information to make informed choices (Aarikka-Stenroos et al., 2018; Batonda & Perry, 2003; Dwyer et al., 1987; Valtakoski, 2015; Wilson, 1995). For this purpose, information gathering for nature and scope is relatively broad, and entails both rational and emotional elements. As suggested by Ferguson (2009, p. 214), organizational buyers that claim “to buy only with their heads, they secretly want to buy with their hearts”.

Managing emotions experienced by potential partners could influence the decision-making process, favouring specific behaviours of the counterpart (Kemp et al., 2018). In this sense, CHM could represent the strategic choice of an organisation that aims to take into account emotions to favour buyer–seller relationship initiation.

Surprisingly, few studies have deepened the relation between CHM and buyer–seller relationship initiation so far, even though heritage conveys emotional elements useful for building long-term relationships. The present study thus aims to answer the following research question:

R.Q.: How does corporate heritage marketing support the buyer–seller relationship initiation?

A single longitudinal case study methodology was adopted (Yin, 2009) in which data were analysed using the “RADaR” approach (Watkins, 2017). The case of a small Italian winery has been extensively examined since it results an emblematic case to explore (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Voronov et al., 2013). The main findings highlight that CHM could be an “initiation contributor” to the buyer–seller relationship initiation (Aarikka-Stenroos et al., 2018), because it improves seller attractiveness in the market by conveying both rational and emotional values (trustworthiness, familiarity, serenity, and authenticity) that facilitate the first contact with the buyer. In addition, after primary interactions, the correct management of the CHM mix could increase seller trustworthiness towards buyers, favouring the perception of coherence between the narrated CHM values and seller reality, helping the parties to establish the trust scenario that leads to their first formal agreement. This study contributes to the literature by providing a conceptualisation of how CHM supports buyer–seller relationship initiation before and after primary interactions between the parties. The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: the second section presents the literature background, the third section describes the adopted methodology, section four presents the main findings and section five provides a discussion of the results and the main theoretical and managerial implications. Finally, conclusions, limitations of the study, and possible future research directions are provided.

2 Literature review

2.1 Buyer–seller relationship: challenge of initiation

Business relationships are characterised by simultaneous and multiple dyadic and network interactions (Håkansson & Snehota, 1989). Given the importance of business relationships in the b2b context, researchers have attempted to conceptualise their development. Several models describe business relationship development as a progression of stages that follows a sequential growth process (Dwyer et al., 1987; Ford, 1990; Heide, 1994; Huston & Levinger, 1978; Kanter, 1994; Larson, 1992; Levinger, 1980; Wilson, 1995). These models have been criticised because relationship development is not a linear and inevitable process; instead, it can stop or fail at any point (Batonda & Perry, 2003). An alternative view was then developed, which considers business relationship development a matter of unpredictable states of development (Batonda & Perry, 2003; Ford et al., 1998; Medlin, 2004; Rosson & Ford, 1982). The term “state” describes a condition that occurs among all the other possible conditions (Batonda & Perry, 2003). According to this notion, buyer–seller relationship development as a sequence of linear growth stages is just one of the possible development trajectories (Holmen et al., 2005). Other theories on business relationship development, such as the joining theories (Thorelli, 1986) and the business dancing concept (Wilkinson et al., 2005) contributed to an ongoing dynamic debate. Despite the interest in the topic, the buyer–seller relationship initiation has rarely been explored (Edvardsson et al., 2008; Holmen et al., 2005; Mandják et al., 2015; Valtakoski, 2015).

Identifying the exact moment when a business relationship begins in the b2b market is challenging, being it characterised by continuous flows of dyadic interactions between various actors during different episodes (Edvardsson et al., 2008).

Valtakoski (2015) pointed out that buyer–seller relationship initiation corresponds to the awareness and exploration phase proposed by Dwyer et al. (1987) and the partner selection and purpose definition phases defined by Wilson (1995). According to the “ business relationship emerging flow” by Mandják et al. (2015), buyer–seller relationship initiation covers the period between a starting situation in which potential partners have no previous knowledge of each other, up until the building of a relationship mediated by trust at both individual and organisational levels.

Aarikka-Stenroos et al. (2018) divide the initiation process into a pre-initiation phase, where the actors are in search of business partners, and an initiating phase, where the parties interact to define the exchange and the conditions of the relationship.

Initially, parties that are open to new relations might perceive significant cultural, technological, and social distance among them which can affect the continuation of the relationship (Tunisini, 2020). Perceived uncertainty could lead the buyer–seller relationship initiation to pause, and even end at any point (Edvardsson et al., 2008). Only interactions, trigger events, and third-actors intermediation can break the possible deadlock and build the conditions for the parties to build the relationship (Aarikka-Stenroos et al., 2018). Edvardsson et al. (2008) explain that converter forces (timing of specific activities, trust, offering and competence) foster the transition from one status to another during buyer–seller relationship initiation. Mandják et al. (2015) use the notion of trigger events (such as personal reputation, prior relations, referral at an individual level and network position, attractiveness, goodwill, visibility at an organisational level) to explain how the actors involved proceed in the relationship initiation.

Aarikka-Stenroos et al. (2018) introduced the concept of “initiation contributors”: diverse entities, such as persons, organisations, or things, that act as gate openers and facilitate business relationship initiation. The authors identified three major initiation contributors: contact, artefact, and ritual contributors. As emerged, the main challenge for business actors is to proceed further in the initiation process and be considered a feasible partner by their counterpart. Wilson (1995) identified trust, social bonds, the level of alternatives, mutual goals, performance satisfaction, and power as the most important variables involved in the early phase of business relationship initiation. With reference to trust, Valtakoski (2015) pointed out that sellers cannot directly influence buyers’ trust but can use mitigation strategies to improve their trustworthiness. Managing these aspects is of paramount importance in the b2b context because buyers are also influenced by emotions in their decision-making process (Corsaro & Maggioni, 2021; Hedman & Orrensalo, 2018).

Emotions have a significant influence on buyer–seller relationships, especially in the initial stages (Zehetner et al., 2012). In their description of the organisational buying behaviour,Webster Jr and Wind (1972) describe the influence of task-related and non-task-related variables in purchasing decision. Task-related variables focus on the rational aspects of decision making, while non-task-related variables entail factors such as personal values, emotions, relationships, and political conditions. Emotions can influence both “task-related” and “non-task-related” variables. The “integrative buying behaviour” model (Sheth, 1973) highlights the role of individual’s psyche in the assessment of social, interpersonal, and power dynamics in an industrial buying situation. More recently, Lynch and De Chernatony (2004) pointed out that organisational buyers value the perception of trust, peace of mind, and security when searching for possible partners; sellers must then convey both functional and emotional messages to b2b buyers, as this increases customer attraction and retention (Lynch & De Chernatony, 2007). According to Andersen and Kumar (2006), emotions and personal chemistry can boost or terminate the relationship. The authors suggest that emotions emerge at multiple levels in buyer–seller relationship development and influence the perception of the counterpart’s trustworthiness and, consequently, the subsequent interactions. Emotions influence behavioural intention and decision-making processes, especially in the initial stages of the buyer–seller relationship initiation (Zehetner et al., 2012). Kaufmann et al. (2017) suggest a multiple systems approach that explicates that decision processing modes in purchasing involves both rational and intuitive processes, further differentiating the latter into experience-based and emotional processing modes. Pandey and Mookerjee (2018) developed a customer experience model for the b2b context, highlighting that symbolic, emotional, and cost values might impact buyers’ purchasing intentions. Following the perspective of Kemp et al. (2018), different emotions are present at all stages in the organizational decision-making process, suggesting that some emotions dominate others in relation to the specific decision-making phase (Kemp et al., 2018). The authors identified emotions such as: interest, excitement, hope, expectation, joy, pride, trust, surprise, fear, anxiety, frustration, regret, and shame. In a systematic literature review on the role of emotions in the b2b context, Ribas and De Almeida (2021) identified 41 emotions that were grouped into seven key emotions: joy, pride, empathy, anger, fear, anxiety, and sadness. The two latter academic contributions recognise that emotions lead to action tendencies among buyers; hence, suppliers must strategically manage the emotion buyers experience.

The academic literature has addressed the theme of emotions in the b2b context, focusing on salesperson emotion and its effects on organizational buyers (Bagozzi, 2006), the role of the emotional dimension in brand value (Hutchins & Rodriguez, 2018; Kemp et al., 2020), the importance of emotion during critical incidents (Vidal, 2014), and for the customer attraction and retention (Lynch & De Chernatony, 2007).

Despite the growing interest in this topic, few studies have analysed the role of emotions in b2b interactions and decision-making processes (Andersen & Kumar, 2006; Kemp et al., 2018; Pandey & Mookerjee, 2018), which calls for a research agenda that focuses on explaining how b2b companies are considering emotions in their marketing approach and which strategies are being adopted. Because CHM conveys emotions that could be strategically used to influence buyers’ decision-making processes and because emotions play a primary role during relationship initiation stages, there is academic interest in exploring how CHM supports the buyer–seller relationship initiation process.

2.2 Corporate heritage marketing: a panoramic view of a new marketing management field.

Leading management literature recognises heritage as a strategic resource for communicating the uniqueness of a company and generating a sense of belonging to the firm (Napolitano et al., 2018). Today, managers use history or heritage for several purposes, such as legitimising or delegitimising strategic options (Brunninge, 2009), enhancing organizational identity over time (Zundel et al., 2016), promoting a sense of authenticity to organizational stakeholders (Smith & Simeone, 2017), communicating the firm’s reliability (Rowlinson & Hassard, 1993), trust (Balmer, 2011), gaining organizational legitimacy within institutional fields (Suddaby, 2016), and competitive advantage (Balmer & Burghausen, 2019; Suddaby et al., 2010).

Although heritage can be defined in a number of ways, through material and immaterial configurations, it certainly incorporates social meaning, expressing the identity of a territory, organisation, or social group (Pearce, 1998). Heritage offers the public an anchor that provides certainty in the uncertainty of modern markets (Balmer, 2011; Sarup, 2022), creating a relational fulcrum with customers and stakeholders (Napolitano & Riviezzo, 2019). Heritage, in contrast to history, does not only refer to the past but also to the present and future, because the past is valuable for today and tomorrow’s stakeholders (Urde et al., 2007).

Corporate heritage represents a set of institutional traits of corporate identity that have remained perennial (Balmer, 2013). Identity traits that have endured for a minimum of three generations or at least 50 years can be considered corporate heritage identities (Balmer, 2011); however, heritage identity traits might also be imagined or contrived (Weatherbee & Sears, 2021). Corporate heritage identities involve multiple role identities: different stakeholders with dissimilar senses of heritage identification can interpret heritage in different ways (Balmer, 2013). Indeed, heritage is subjected to change, transformation, and reinterpretation. This concept is related to the relative invariance notion introduced by Balmer (2011) which explains that corporate heritage traits that appear invariant, in reality might have changed to maintain the same meaning. In summary, CHM is a strategic choice of a firm that sees its organisational history as a means to support value creation activities toward both internal and external actors (Misiura, 2006). This is particularly true for family businesses, the survival of which is determined by historical interactions between the family, the company, and its cultural environment (Blombäck & Brunninge, 2013; Spielmann et al., 2021). Indeed, family businesses can refer to their history to unfold corporate heritage marketing practices in several ways (Blombäck & Brunninge, 2013): by exploiting their longevity to communicate stability, by tracking their records as proof of goodwill, by transferring their core values into their economic activities, and by exploiting their history to consolidate corporate identity. Family businesses can also build corporate heritage based on their history, business history, or a combination of both, allowing them to emphasise their heritage through several configurations (Blombäck & Brunninge, 2013).

However, CHM is a strategic and interactive process composed of four main phases: auditing, visioning, managing, and controlling (Riviezzo et al. (2021). The first stage involves the crucial identification of heritage factors: notably, not all the firm’s history becomes heritage. The main heritage themes should be the result of an accurate selection of historical events that must be considered appealing to the various firm’s stakeholders (Riviezzo et al., 2021). The visioning phase encompasses the definition of the narrative objectives and the target audience for CHM activities. More importantly, at this stage, the CHM role is decided within the firm’s overall marketing strategy. The managing stage involves the scrutiny of the evidence of the past put into practice with the active participation of internal and external actors. In this phase, the CHM strategy takes shape by identifying figures responsible for gathering, controlling, preserving, and exploiting heritage assets (Balmer & Burghausen, 2019; Burghausen & Balmer, 2014, 2015). In this stage, the CHM mix is defined based on the strategic choices made previously (Garofano et al., 2020). CHM can be narrated through words and images (e.g., companies’ monographies, social networks), products, and brands, through places (e.g., museums, archives), celebrations, and relationships. Among the CHM mix tools, brand heritage, a dimension of a brand’s identity, plays a prominent role (Urde et al., 2007). The last phase of the CHM process is the controlling phase, which consists of the evaluation of the results and the planning of appropriate corrective actions according to the target objectives.

3 Methodology

3.1 Case study

A qualitative and single longitudinal case study methodology of a small winery, Alpha, has been considered an effective approach to investigate how CHM supports buyer–seller relationship initiation. A case study is an appropriate research methodology when “how” research questions are posed and the researcher has little control over the events examined (Patnaik & Pandey, 2019; Yin, 2009). According to Benbasat et al. (1987), case study research is particularly useful when research and theory are in their early stage as the topic object of this study. Since no previous studies on the research theme have been detected, an exploratory in-depth longitudinal case study analysed through a grounded theory approach has been considered a valuable research methodology for unfolding processes, contextual factors, and hidden interactional patterns of the process related to CHM in buyer–seller relationship initiation (Aaboen et al., 2012; Eisenhardt, 1989; Strauss & Corbin, 1998; Voss, 2010). Hence, this study adopts a processual perspective (Langley, 1999) to discover how events unfold in buyer–seller relationship initiation. Since the unit of analysis is to explore how CHM supports buyers and sellers during relationship initiation, it is necessary to delimit the case study. According to the work of Halinen and Törnroos (2005), the case study has been limited through the focal actor perspective as reported in Fig. 1.

3.2 Research setting and case selection

The wine context is an optimal base to study the unexplored issue; indeed, wine is produced in the present to be consumed in the future, and wineries are usually dependent on the identity of their heritage. Moreover, history and heritage are relevant constructs for building legitimacy and authenticity in the wine field (Beverland, 2005; Pizzichini et al., 2022; Voronov et al., 2013). Nonetheless, several recent studies have reported that wineries emphasise heritage elements related to family history and/or place-related characteristics (Kladou et al., 2020; Spielmann et al., 2021; Weatherbee & Sears, 2021). In addition, small wineries rely on strategic partnerships to overcome their structural issues outside and within the supply chain (Temperini et al., 2022); hence, they are keen to develop buyer–seller relationships. Once the small winery was considered an optimal case study to investigate, criteria to select the small winery through theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) were established as follows:

-

The small winery is in its third generation or has been in the market for over 50 years, following the third corporate heritage criterion introduced by Balmer (2013);

-

The small winery must recognise that its CHM plays a prominent role in its overall marketing strategy;

-

Geographical proximity to the small winery and a good relationship with the small winery’s CEO to grant preferential access to data and documents were considered additional rationales (Yin, 2009).

The small winery Alpha was selected for the case study because it matches all of the above-mentioned criteria. The winery carries out marketing activities to valorise its longevity, family history, and core values. As declared by Alpha’s CEO:

To succeed in the wine context, you should have a recognised brand or be present in specific guides or awards. I still do not have a well-known brand, and I refuse to participate in guides and awards as I do not think that is right to pay to participate or even win prizes. So, since the beginning I decided to bet everything on the history of my family and company to enhance my value.

To provide insight, a brief description of Alpha’s commitment to its heritage is provided in Fig. 2.

3.3 Data collection

Primary data were obtained through a series of semi-structured interviews with the CEO of Alpha, two different restaurant CEOs in a business relationship with Alpha (Kvale, 2012), and through direct observations and participation at the meeting of the entrepreneur’s association in which Alpha is involved. During this meeting, I had the opportunity to interview some b2b participants and listen to Alpha’s presentation to prospect buyers. To triangulate the findings, additional data were gathered through semi-structured interviews with three wine market experts, two sommelier representatives and one CEO of a digital service provider specialized in Food&Wine sector (Patton, 2014). Data collection was considered complete when multiple sources of evidence converged on the same findings, which is an optimal indicator of theoretical saturation (Yin, 2009).

An overview of the interviews carried out is provided in Table 1.

3.4 Data analysis

Data were analysed using the “RADaR” technique (Watkins, 2017). This technique is a user-friendly way of organising, reducing, and analysing data to obtain findings from qualitative research. This is considered a rigorous data analysis method because of the systematic strategies employed during each step of the analysis. The “RADaR” technique is particularly suitable for managing a small number of interviews (less than 15 individual interviews) and for research projects that adopt a grounded theory approach. The data analysis process was articulated in five steps, and coding was performed manually using Microsoft Excel as follows. First, I formatted all data transcripts in a similar manner, then I transferred the data into an all-inclusive table, in which the columns provided information about participants’ responses, codes, notes, and themes. Hence, this table includes large segments of text taken from the transcripts. Next, I reviewed the table to make notes about the commonalities in the participants’ responses to each question. Thirdly, I proceeded to reduce the content of the all-inclusive table in a more concise “table 2” concentrating only on the content that was of primary interest to answer the research question. To do so, I was aware of the need to maintain a chain of evidence from the case study question to the findings. Hence, I removed data that did not help to answer the research question. This process led me to move from open to focused codes. To facilitate the process, I have made notes on my decisions. In Step 4, I decided which codes to maintain until the end of the analysis. Then, I proceeded to reduce the content of “table 2” in a more concise “table 3”. Hence, the focused codes became themes. In step 5, I used the remaining quotes in “table 3” to support the findings of the present study. Finally, in this phase, a draft of the findings was provided to Alpha’s CEO and the two restaurant owners to ensure the validity of the findings. In Fig. 3, there is a partial exemplification of the data analysis process I have followed.

4 Findings

In the interest of clarity, the following findings are organised by themes.

4.1 Theme 1: authenticity, unicity, and attractiveness before primary interactions

Alpha’s CEO is aware that the wine market has increased in complexity in recent years. To succeed in this context, she decided to bet everything on the heritage of her family which is totally linked to the firm. Alpha’s heritage has been valorised by several means such as products, external communication, site visits, logos, and so on.

I am building Alpha’s brand through the history of my family and company, showing everyone the steps, we took to grow. [Alpha’s CEO]

CHM is regarded as a useful marketing strategy also to attract b2b buyers. Indeed, CHM activities allow the small winery to present itself with contents that are not specifically linked with selling aims, leading into the b2b audience a sincere interest in listening to the small winery’s corporate heritage.

…The company's heritage allows me to present myself with less commercial content […]. I sense from the people listening to our corporate’s heritage their desire to be part of it. [Alpha’s CEO]

Nonetheless, during the interviews, the two sommeliers specifically stated that wineries are usually characterised by cultural and historical aspects that are not secondary; these elements must be enhanced to attract potential partners. This was particularly evident during a meeting in the entrepreneur’s association in which Alpha usually takes part. On that occasion, the CEO had the opportunity to promote a new sparkling wine, prepared using the ancestral method. During her presentation in front of several possible b2b partners, she talked about her family’s heritage and described the history of the ancestral method, starting from its casual discovery. The narration was full of historical references and the audience was pleased. The presentation ended with a historical phrase, a way to communicate that is constantly used on Alpha’s social media. This narration aroused the interest of the owner of the restaurant Beta, who contacted the CEO after the presentation.

I met Vini Valmusone for the first time in this association of entrepreneurs. On that day, the CEO of Vini Valmusone had the opportunity to present the company and one of its new products, a sparkling wine produced with the ancestral method, an ancient and natural method. During her presentation, Alpha’s CEO made clear reference to her company heritage, which is a good story, it struck me […]. Her company heritage leaves me with the ideas of solidity, authenticity, and attachment to traditions. [Owner of restaurant Beta]

The notion of “solidity” suggests a need for buyers to count rational elements in supplier selection. CHM can communicate solidity enhancing the history of the company, tracking and exposing the firm’s records. In this regard, Alpha’s CEO stated that the company’s heritage evokes authenticity and interest, making the firm more attractive.

… therefore, before there is any contact, corporate heritage allows me to present my company as authentic and solid. This makes my company attractive. [Alpha’s CEO]

Notably, Alpha’s CEO recounted an event that underscores the importance of Alpha’s corporate heritage in attracting b2b partners.

I was very interested in selling my wines to a famous wine bar. My insurer knew the owner’s wife, so he agreed to introduce her to my firm. She was willing to try my production. Hence, the insurer gave me her phone number. I tried to call her many times, but she always had a ready excuse, so it was impossible for me to make an appointment and illustrate my firm’s heritage. Me and my insurer were both inside an entrepreneur association that usually met on Thursday mornings to network. During these meetings, entrepreneurs had the opportunity to present their company through rotation. When it was my turn, my insurer had the good idea of inviting the owner’s wife. Hence, in this meeting, I had the opportunity to narrate to her our corporate heritage and iconic products such as the one we created to honour our great-great-grandfather. She fell in love with our history and decided to make an appointment a few days after the presentation. The result was a fantastic conversation with the owner of this wine bar that is still nowadays one of my clients [Alpha’s CEO]

As emerged from the episode, and according to the thoughts of the owner of the restaurant Omega, before any interaction between the parts, CHM increases the attractiveness of the small winery attracting the interest of potential buyers.

At first, before actual contact, I have to say that it attracted me a lot and prompted me to learn more about the winery [Owner of restaurant Omega]

4.2 Theme 2: CHM conveys empathy, serenity, common roots, and familiarity before the primary interactions

The small winery CHM activities also convey emotional elements. Goodwill, serenity, familiarity, and roots were the main values that the interviewees attributed to CHM.

Above all, her company history conveys to me serenity, familiarity, and human relationships; when she told her story, I imagined her personally bottling her wine. This for me is important and attractive, this is what prompted me to contact her then. [Owner of restaurant Beta]

Alpha’s CEO played attention to promoting the goodwill and the roots of her company because she is aware that these aspects facilitate the opportunity to interact with buyers.

Our corporate heritage enhances the goodwill towards us in the social context […]. Thanks to my family business heritage, I communicate our roots: if someone identifies her or himself with this history, it is more likely that he or she will contact me. [Alpha’s CEO]

In line with restaurant owners, these emotional elements act as initial parameters to evaluate the seller and people behind the business.

For me, corporate’s heritage becomes a means of judging the person and determining whether I like that person. [Owner of restaurant Beta]

Alpha’s heritage reminds me of the history of our restaurant. I recognise myself in that history; we have common roots. Alpha’s history conveys to me love for what it does and trust. [Owner of restaurant Omega]

The owner of restaurant Omega points out that common roots are a means to push the buyer to reconsider its business and human journey; this emotional trip allows to confront the companies’ history involving elements that evoke love for production and trustworthiness towards the seller. This is in line with the concept of “familiarity”, which is expressed by the owner of the restaurant Beta. These emotional aspects increase the small winery’s attractiveness and the willingness of the buyers to make contact with the small winery for the first time.

4.3 Theme 3: perceived coherence between CHM communication and small winery reality prompts buyers’ trust

During primary interactions, the actors are involved in getting to know each other, understanding the counterpart’s needs, and establishing reciprocal trust that will probably lead to the first business agreement and, consequently, the end of the buyer–seller relationship initiation phase. In this context, a correct management of the CHM mix allows buyers to test the trustworthiness of the small winery. As explained by restaurant owners, when they perceive coherence between corporate heritage marketing communications and the small winery reality, this prompts buyers to trust the seller and start the business relationship.

If I perceive the story told in the products and the way the company presents itself, this prompts me to trust the company and start a business relationship. [Owner of restaurant Omega]

In choosing the wine, I am not alone; I involve my restaurant staff. To choose the wines of the company I took to 4–5 bottles as samples. On a subconscious level, I realised that in presenting these bottles to my staff, I shared that the products came from a serious company that has been involved in the production and marketing of wine since the 1950s. Hence, the company heritage told by the CEO impressed me so much that it pushed me to introduce this produce in that manner. When we tasted the wines, we were satisfied, so this coherence between a quality story and product value was the final step for me that allowed this company to gain my trust and become my supplier. [Owner of restaurant Beta]

Corporate heritage values must be conveyed by small wineries in their products, and in all aspects related to the winery site, buyers need to feel that corporate heritage is a leading element of small winery production. Alpha’s CEO is aware of these elements and communicates corporate heritage in product packaging, websites, social media, and during visits to winery sites through pictures, photos, and salespeople.

I then gain trust when my partners verify that the story I have told them, is not just an end in itself; they will find it in the products and during visits to the vineyard and cellar [Alpha’s CEO]

5 Discussion

5.1 Discussion of results

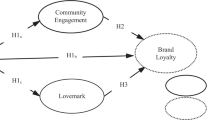

Drawing upon the findings, Fig. 4 conceptualises how CHM supports buyer–seller relationship initiation. As pointed out in the management literature, the starting point of the buyer–seller relationship initiation is a situation in which the actors do not know each other, and no primary interactions have been verified. Both the actors are in search of business partners and as suggested by Dwyer et al. (1987), they are involved in “positioning” and “posturing” activities to attract the counterpart. This is a difficult phase, especially for the seller that has to make itself preferred by the buyer over its competitors. In doing so, the seller attempts to transmit rational and emotional elements to the buyer. As emerged from the findings, CHM has the potential to convey both rational and emotional aspects that buyers are searching for during the initial stages of a buyer–seller relationship, leading the actors to have primary interactions. Indeed, CHM can transmit rational element tracking records and communicate a long-standing history in the market, which simultaneously enhances the solidity of the firm and its authenticity and uniqueness. At the same time, CHM conveys emotional elements sharing common roots that evoke a sense of familiarity, empathy, and serenity that allows buyers to recognise themselves in the seller's corporate heritage, increasing the seller's trustworthiness. Owing to the adoption of CHM activities, the seller is capable of transmitting both rational and emotional elements to the buyer, thereby increasing its attractiveness and facilitating the first interaction between the parts. After primary interaction occurs, the parts are involved in the establishment of the first exchange and in demarcating the conditions that define the emerging business relationship. In this phase, the construction of a trust scenario is crucial to let the actors sign the first agreement that enshrines the end of the buyer–seller relationship initiation. In this delicate situation, the perceived coherence between the values narrated through CHM activities and the seller's reality leads the buyer to perceive trust in the seller, thus facilitating the achievement of the first agreement. In doing so, it is essential for the seller to carefully manage its CHM mix to provide coherence between what is transmitted through CHM activities and its firm's reality at every possible touchpoint with potential buyers.

5.2 Theoretical implications

Before interactions between buyer and seller, CHM conveys both rational and emotional elements, increasing seller attractiveness towards buyers facilitating the first interaction between the parts. As described in the findings, CHM communicates seller solidity, which refers to the ability of the firm to perdure in the market, this element meets rational aspects that buyers are searching for during buying decision-making (Webster Jr & Wind, 1972). CHM conveys solidity through tracking records and exposing firm’s longevity confirming the findings of Blombäck and Brunninge (2013). CHM improves seller’s trustworthiness, influencing buyers’ cognitive and affective trust (Valtakoski, 2015). Specifically, CHM increases both cognitive trust, by using rational elements to highlight seller’s stability, continuity, and expertise, and affective trust by communicating the seller’s local roots and enhancing the seller’s brand heritage identity. Nonetheless, as affirmed by Balmer (2011), trust between corporate heritage firms and customers depends on a dynamic equilibrium between authenticity and affinity, elements that CHM is capable of transmitting in the b2b context. Indeed, as emerged, CHM conveys authenticity, familiarity, roots, and goodwill towards buyers, increasing the seller’s trustworthiness. Moreover, CHM is capable of providing emotional elements such as serenity, interest, and empathy which are researched by buyers especially during the buyer–seller relationship initiation period (Kemp et al., 2018; Lynch & De Chernatony, 2004). In particular, CHM conveying interest, empathy, and reassuring factors leads in buyers action tendency towards an urge to deepen seller knowledge and, consequently, the first interaction between the actors (Kemp et al., 2018). Hence, in relation to the prior literature, the present study argues that CHM is a strategic choice that sellers can use to convey and manage both rational and emotional values towards buyers leading in them specific action tendencies.

Once the first interactions have occurred, the perceived coherence between corporate heritage marketing and supplier’s reality concur to increase buyer’s trust, facilitating the first agreement between the parties. The correct management of the CHM mix is considered an additional seller mitigation strategy that aims to improve the seller’s trustworthiness (Mandják et al., 2015; Valtakoski, 2015). Consequently, it is possible to affirm that CHM acts as a “converter force” that helps the buyer–seller relationship initiation process to proceed from one status to another in line with Edvardsson et al. (2008). Indeed, CHM improves trust which is described as a converter force (Edvardsson et al., 2008). Similarly, following the perspective of the “business relationship emerging flow” of Mandják et al. (2015), CHM is a trigger to start mutual interaction process and develop trust between the actors at both organizational and individual level because it improves the seller’s attractiveness and goodwill in the social context. As a result, according to the contributions of Aarikka-Stenroos et al. (2018), CHM acts as an “initiator contributors” triggering and advancing the buyer–seller relationship initiation process. It is now quite evident that CHM influences buyer–seller relationship initiation, but its major role is played before interactions have occurred. Indeed, CHM allows the seller to become more attractive to buyers, especially before any contact between the parts has been verified, which is the main topic of major studies on b2b relationship development (Aarikka-Stenroos et al., 2018; Batonda & Perry, 2003; Dwyer et al., 1987; Wilson, 1995). In the very first moment of buyer–seller relationship initiation, the two actors coexist in proximity but do not know each other (Mandják et al., 2015). In this phase, for the seller, it is important to increase its attractiveness to be considered by the buyers as a potential and feasible partner (Dwyer et al., 1987). Therefore, in this context, CHM plays a major role in pushing parts to the first interaction. Meanwhile, after the first interactions have occurred, the parts are involved in defining the exchange and building the condition of the emerging relationship; in this scenario, CHM only partially concurs to build the trust scenario that facilitates the first formal agreement between the actors (Aarikka-Stenroos et al., 2018). To summarise, in relation to previous studies on this topic, the present study adds the following:

-

CHM is a converter force (Edvardsson et al., 2008), a trigger (Mandják et al., 2015) and an initiation contributor (Aarikka-Stenroos et al., 2018) to the buyer–seller relationship initiation.

-

CHM is a strategic choice for a firm to create and convey rational and emotional values towards buyers leading into them specific action tendencies (Kemp et al., 2018).

-

Before the interaction between the actors, the CHM improves sellers’ attractiveness, facilitating the first contact between the parts.

-

CHM transmits interest, empathy, and serenity which are the emotional aspects that buyers search for during the very first moment of buyer–seller relationship initiation (Kemp et al., 2018; Lynch & De Chernatony, 2004).

-

CHM improves seller trustworthiness, influencing both cognitive and affective trust before the interaction between parts during buyer–seller relationship initiation (Mandják et al., 2015; Valtakoski, 2015).

-

After interactions, CHM concurs to build the trust scenario that facilitates the first formal agreement between the parts through the correct management of the CHM mix to provide evidence of the coherence between CHM activities and seller realities.

-

In the buyer–seller relationship initiation process, CHM plays a major role before primary interactions between the actors.

5.3 Managerial implications

This case study has several practical implications. If properly managed, corporate heritage marketing could be a trigger for buyer–seller relationship initiation. Exploiting a firm and/or family heritage requires a specific process and cannot be reduced to an episodic marketing initiative. As described by Riviezzo et al. (2021), the correct management of heritage implies a specific process that is not simple to apply for SMEs, especially for small wineries. Hence, hereafter is suggested an incremental approach to CHM management for SMEs. First, small firms should identify the role of the CHM within their marketing activities. SMEs should then select heritage elements that they want to share, and that could emphasise a firm’s authenticity, solidity, roots, and could be appealing for possible partners and firm stakeholders. Small firms must properly manage the CHM mix to influence affective and cognitive trust and favour the perception of coherence between their realities and the transmitted CHM values: to this purpose, small firms should develop appropriate corporate heritage stewardship and a predisposition in the firm’s site spaces dedicated to enhancing the firm and/or family heritage. Attention should also be paid to packaging, websites, and social media communication. This study thus proposes a sort of simplified CHM process for SMEs, suggesting that sellers should carefully consider how to create and manage emotions during the relationship initiation period, to lead in potential buyers specific action tendencies; emotional values might indeed impact buyers more than rational elements, especially in the very first stages of relationship initiation. In this context, buyers should carefully verify what is communicated through seller CHM initiatives, because heritage traits can be imagined or contrived. Hence, buyers should test whether the firm’s heritage is seller value or just a commercial initiative.

6 Conclusion, limitation, and future research

This study develops an initial understanding of how CHM supports buyer–seller relationship initiation. A longitudinal case study of a small Italian winery was performed. As the unit of analysis involves buyer–seller relationship initiation, the case study has been delimited from the focal actor perspective. To guide the data analysis, the “RADaR” approach was chosen, and triangulation of the data was performed to validate the findings. The findings support the value-added contributions of this study, as summarised below. To answer the research question, how does corporate heritage marketing support the buyer–seller relationship initiation?, the present study demonstrates that CHM could be an initiation contributor to buyer–seller relationship initiation: it could lead to the first interactions between the parts, and then it is one of the triggers that lead to the first formal agreement. Specifically, CHM improves seller attractiveness in the market before contact between the parts has been verified by conveying emotional (affinity, serenity, trust) and rational elements that buyers are searching for during the very first moment of relationship initiation.

After primary interactions, the correct management of the corporate heritage marketing mix is a useful mitigation strategy that contributes to the seller’s trustworthiness when buyers notice coherence between CHM initiatives and the firm’s site and production. Moreover, thanks to CHM initiatives, buyers can identify feasible partners perceiving reassuring emotional factors during their partner choices. Practical implications of the study are also provided; to be precise, a simplified model designed for SMEs for the management of CHM is suggested along with advice for buyers.

Some limitations of this study must be acknowledged, the most important being its qualitative and explorative nature. The study is limited by the examined context and the relatively small number of interviews done considering the complexity of the phenomenon researched. Further research should consider multiple case study methodology to employ in different contexts and design quantitative methodologies to discover more on the role of CHM in promoting buyer–seller relationship initiation. In conclusion, corporate heritage marketing has gained consensus in management literature and in a real context; hence, this research deserves attention because it guides firms to exploit this strategic resource in an innovative way in relationship initiation contexts.

References

Aaboen, L., Dubois, A., & Lind, F. (2012). Capturing processes in longitudinal multiple case studies. Industrial Marketing Management, 41(2), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.01.009

Aarikka-Stenroos, L., Aaboen, L., Cova, B., & Rolfsen, A. (2018). Building B2B relationships via initiation contributors: Three cases from the Norwegian-South Korean international project business. Industrial Marketing Management, 68, 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.09.027

Andersen, P. H., & Kumar, R. (2006). Emotions, trust and relationship development in business relationships: A conceptual model for buyer–seller dyads. Industrial Marketing Management, 35(4), 522–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.10.010

Bagozzi, R. P. (2006). The role of social and self-conscious emotions in the regulation of business-to-business relationships in salesperson-customer interactions. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620610708948

Balmer, J. M. (2011). Corporate heritage identities, corporate heritage brands and the multiple heritage identities of the British Monarchy. European Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111151817

Balmer, J. M. (2013). Corporate heritage, corporate heritage marketing, and total corporate heritage communications: What are they? What of them? Corporate Communications: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-05-2013-0031

Balmer, J. M., & Burghausen, M. (2019). Marketing, the past and corporate heritage. Marketing Theory, 19(2), 217–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593118790636

Batonda, G., & Perry, C. (2003). Approaches to relationship development processes in inter-firm networks. European Journal of Marketing, 37(10), 1457–1484. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560310487194

Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D. K., & Mead, M. (1987). The case research strategy in studies of information systems. MIS Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.2307/248684

Beverland, M. B. (2005). Crafting brand authenticity: The case of luxury wines. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1003–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00530.x

Blombäck, A., & Brunninge, O. (2013). The dual opening to brand heritage in family businesses. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 18(3), 327–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-01-2012-0010

Brunninge, O. (2009). Using history in organizations: How managers make purposeful reference to history in strategy processes. Journal of Organizational Change Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810910933889

Burghausen, M., & Balmer, J. M. (2014). Repertoires of the corporate past: Explanation and framework. Introducing an Integrated and Dynamic Perspective. Corporate Communications: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-05-2013-0032

Burghausen, M., & Balmer, J. M. (2015). Corporate heritage identity stewardship: A corporate marketing perspective. European Journal of Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2013-0169

Corsaro, D., & Maggioni, I. (2021). Managing the sales transformation process in B2B: Between human and digital. Italian Journal of Marketing, 2021(1), 25–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00025-w

Carolina, R.A. De Almeida L. (2021), The role of emotions in B2B context: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the European marketing academy, 50th, (93404).

Dwyer, F. R., Schurr, P. H., & Oh, S. (1987). Developing buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298705100202

Edvardsson, B., Holmlund, M., & Strandvik, T. (2008). Initiation of business relationships in service-dominant settings. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(3), 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2007.07.009

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

Ferguson, R. (2009). The consumer inside: At its heart, all marketing speaks to human beings. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 26(3), 214–218. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760910954145

Ford, D. (1990). The development of buyer-seller relationships in industrial markets. Understanding business markets (pp. 42–57). London: Academic Press.

Ford, D., Gadde, L.-E., Håkansson, H., Lundgren, A., Shenota, I., Turnbull, P., & Wilson, D. (1998). Managing business relationships.

Garofano, A., Riviezzo, A., & Napolitano, M. R. (2020). Una storia, tanti modi di raccontarla. Una nuova proposta di definizione dell’heritage marketing mix/One story, so many ways to narrate it. A new proposal for the definition of the heritage marketing mix. IL CAPITALE CULTURALE. Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage, 10, 125–146. https://doi.org/10.13138/2039-2362/2460

Håkansson, H., & Snehota, I. (1989). No business is an island: The network concept of business strategy. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 5(3), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/0956-5221(89)90026-2

Halinen, A., & Törnroos, J. -Å. (2005). Using case methods in the study of contemporary business networks. Journal of Business Research, 58(9), 1285–1297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.02.001

Hedman, I., & Orrensalo, T. P. L. (2018). Brand image as a facilitator of relationship initiation. In Developing insights on branding in the B2B context. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78756-275-220181006

Heide, J. B. (1994). Interorganizational governance in marketing channels. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800106

Holmen, E., Roos, K., Kallevåg, M., Von Raesfeld, A., de Boer, L., & Pedersen, A.-C. (2005). How do relationships begin. In Proceedings of the 21st international marketing and purchasing (IMP) conference.

Huston, T. L., & Levinger, G. (1978). Interpersonal attraction and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.29.020178.000555

Hutchins, J., & Rodriguez, D. X. (2018). The soft side of branding: Leveraging emotional intelligence. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-02-2017-0053

Kanter, R. M. (1994). Collaborative advantage. Harvard Business Review, 72(4), 96–108.

Kaufmann, L., Wagner, C. M., & Carter, C. R. (2017). Individual modes and patterns of rational and intuitive decision-making by purchasing managers. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 23(2), 82–93.

Kemp, E., Briggs, E., & Anaza, N. A. (2020). The emotional side of organizational decision-making: Examining the influence of messaging in fostering positive outcomes for the brand. European Journal of Marketing, 54(7), 1609–1640. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2018-0653

Kemp, E. A., Borders, A. L., Anaza, N. A., & Johnston, W. J. (2018). The heart in organizational buying: Marketers’ understanding of emotions and decision-making of buyers. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-06-2017-0129

Kladou, S., Psimouli, M., & Kapareliotis, I. (2020). The role of brand architecture and brand heritage for family-owned wineries: The case of Crete, Greece. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 41(3), 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2020.10032631

Kvale, S. (2012). Doing interviews. Sage.

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.2307/259349

Larson, A. (1992). Network dyads in entrepreneurial settings: A study of the governance of exchange relationships. Administrative Science Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393534

Levinger, G. (1980). Toward the analysis of close relationships. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16(6), 510–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(80)90056-6

Lynch, J., & De Chernatony, L. (2004). The power of emotion: Brand communication in business-to-business markets. Journal of Brand Management, 11(5), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540185

Lynch, J., & De Chernatony, L. (2007). Winning hearts and minds: Business-to-business branding and the role of the salesperson. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(1–2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725707X178594

Mandják, T., Szalkai, Z., Neumann-Bódi, E., Magyar, M., & Simon, J. (2015). Emerging relationships: How are they born? Industrial Marketing Management, 49, 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.031

Medlin, C. J. (2004). Interaction in business relationships: A time perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2003.10.008

Misiura, S. (2006). Heritage marketing. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080455501

Napolitano, M. R., & Riviezzo, A. (2019). Stakeholder engagement e marketing: Una sfida da cogliere o già vinta? Micro & Macro Marketing, 28(3), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1431/95036

Napolitano, M. R., Riviezzo, A., & Garofano, A. (2018). Heritage Marketing. Come aprire lo scrigno e trovare un tesoro, Napoli: Editoriale Scientifica. https://iris.unisannio.it/handle/20.500.12070/14232?mode=full

Pandey, S. K., & Mookerjee, A. (2018). Assessing the role of emotions in B2B decision making: An exploratory study. Journal of Indian Business Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIBR-10-2017-0171

Patnaik, S., & Pandey, S. C. (2019). Case study research. In Methodological issues in management research: Advances, challenges, and the way ahead. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78973-973-220191011

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage publications. ISBN-10 (9781412972123)

Pearce, S. M. (1998). The construction of heritage: The domestic context and its implications. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 4(2), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527259808722224

Pizzichini, L., Andersson, T. D., & Gregori, G. L. (2022). Seafood festivals for local development in Italy and Sweden. British Food Journal, 124(2), 613–633. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-04-2021-0397

Riviezzo, A., Garofano, A., & Napolitano, M. R. (2021). Corporate heritage marketing: Using the past as a strategic asset. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003167259

Rosson, P. J., & Ford, I. D. (1982). Manufacturer-overseas distributor relations and export performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 13(2), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490550

Rowlinson, M., & Hassard, J. (1993). The invention of corporate culture: A history of the histories of Cadbury. Human Relations, 46(3), 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600301

Sarup, M. (2022). Identity, culture and the postmodern world. Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474472272

Sheth, J. N. (1973). A model of industrial buyer behavior. Journal of Marketing, 37(4), 50–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297303700408

Smith, A., & Simeone, D. (2017). Learning to use the past: The development of a rhetorical history strategy by the London headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Management and Organizational History, 12(4), 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2017.1394199

Spielmann, N., Cruz, A. D., Tyler, B. B., & Beukel, K. (2021). Place as a nexus for corporate heritage identity: An international study of family-owned wineries. Journal of Business Research, 129, 826–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.05.024

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1999-02001-000

Suddaby, R. (2016). Toward a historical consciousness: Following the historic turn in management thought. Management, 19(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/10.3917/mana.191.0046

Suddaby, R., Foster, W. M., & Trank, C. Q. (2010). Rhetorical history as a source of competitive advantage. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0742-3322(2010)0000027009

Temperini, V., Sabatini, A., & Fraboni, P. F. L. (2022). Covid-19 and small wineries: New challenges in distribution channel management. Piccola Impresa/small Business. https://doi.org/10.14596/pisb.2893

Thorelli, H. B. (1986). Networks: Between markets and hierarchies. Strategic Management Journal, 7(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250070105

Tunisini, A. (2020). Marketing B2B: Capire e gestire le reti e le relazioni tra imprese. Hoepli Editore.

Urde, M., Greyser, S. A., & Balmer, J. M. (2007). Corporate brands with a heritage. Journal of Brand Management, 15(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550106

Valtakoski, A. (2015). Initiation of buyer–seller relationships: The impact of intangibility, trust and mitigation strategies. Industrial Marketing Management, 44, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.10.015

Vidal, D. (2014). Eye for an eye: Examining retaliation in business-to-business relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 48(1/2), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2011-0173

Voronov, M., De Clercq, D., & Hinings, C. (2013). Conformity and distinctiveness in a global institutional framework: The legitimation of O ntario fine wine. Journal of Management Studies, 50(4), 607–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12012

Voss, C. (2010). Case research in operations management. In Researching operations management (pp. 176–209). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203886816

Watkins, D. C. (2017). Rapid and rigorous qualitative data analysis: The “RADaR” technique for applied research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917712131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917712131

Weatherbee, T., & Sears, D. (2021). (En) act your age! Marketing and the marketization of history in young SMEs. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-10-2020-0051

Webster, F. E., Jr., & Wind, Y. (1972). A general model for understanding organizational buying behavior. Journal of Marketing, 36(2), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297203600204

Wilkinson, I., Young, L., & Freytag, P. V. (2005). Business mating: Who chooses and who gets chosen? Industrial Marketing Management, 34(7), 669–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2005.06.003

Wilson, D. T. (1995). An integrated model of buyer-seller relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 335–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207039502300414

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v14i1.73

Zehetner, A., Engelhardt-Nowitzki, C., Hengstberger, B., & Kraigher-Krainer, J. (2012). Emotions in organisational buying behaviour: A qualitative empirical investigation in Austria. Modelling value: Selected papers of the 1st international conference on value chain management

Zundel, M., Holt, R., & Popp, A. (2016). Using history in the creation of organizational identity. Management and Organizational History, 11(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2015.1124042

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università Politecnica delle Marche within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fraboni, P.F.L. Corporate heritage marketing to support the buyer–seller relationship initiation: the case of a small winery. Ital. J. Mark. 2023, 521–543 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00079-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00079-y