Abstract

Perceptions of negative events related to service disruptions, negative consumer associations with other brand users, or business activities not in line with consumer ethical standards can lead consumers to abandon and change a brand. Focusing on a low-cost airline company, the study analyses how negative events can affect brand loyalty by considering the mediating effect of consumers’ psychological characteristics in terms of difficulty in choosing between alternatives (choice difficulty) and tendency to switch brands (brand switcher). The paper tests two hypotheses by administering a structured questionnaire to a sample of 260 tourists and shows that: (1) brand switcher negatively mediates the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty; (2) choice difficulty positively mediates the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty. The findings carry theoretical and managerial implications and confirms the value of communication strategies in increasing brand loyalty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Travel is a key component of the tourism industry (Currie & Falconer, 2014) able to influence tourists’ overall experience and satisfaction with the destination (Thompson & Schofield, 2007). In the airline sector, numerous research studies have shown that quality of pre-flight, in-flight, and post-flight services significantly influence customer satisfaction and, consequently, brand loyalty (Jiang & Zhang, 2016; Curry & Gao, 2012; Han & Hwang, 2017). Indeed, brand loyalty—reflecting the degree of customer brand attachment (Aaker, 1991)—is considered a strategic resource to develop a competitive advantage (Iordanova, 2017; Khan et al., 2021). Customers retention remains strategically essential for improved profitability in a scenario where virtually all organizations compete on the basis of quality service (Caruana, 2002; Mileti et al., 2011). Consequently, service-based companies, such as airlines, must provide excellent services to survive in increasingly competitive global markets. However, even though service quality is seen as a competitive and differentiating advantage, in recent years there has been a trend in several sectors to use price as the main strategic weapon. The pursuit of cost advantage is behind the success of low-cost airlines, as certain service elements are reduced or eliminated in order to pass savings on to the customer, with prices significantly lower than those of established companies —such as national airlines —thanks in part to deregulation resulting from globalization and technological innovations (Curry & Gao, 2012). Low-priced companies are favored by the fact that consumers are more disenchanted with brands and more informed thanks to the Internet (Curry & Gao, 2012).

Customer loyalty is an essential factor in a company’s success and, consequently, in improving profitability. However, there are negative events that can undermine this resource by pushing consumers to change brands. A negative event occurs when an individual experiences an unexpected problem or conflict associated with a brand, such as a service failure, product damage, negative publicity, brand transgressions or any other negative incident that occurs between a customer and a brand (Khamitov et al., 2020). According to Zarantonello et al. (2016), there are three types of negative events: (i) experiences of dissatisfaction with reference to the brand; (ii) consumers’ negative associations with other brand-users; (iii) business activities that do not align with consumer ethical standards, including sufficient sustainability performance. For airline companies the occurrence of one (or more) negative events during a person’s trip could reduce their satisfaction and decrease their brand loyalty (Kartsan, 2022). Although there is a large literature that has focused on the relationship between negative events and loyalty (e.g., Chang et al., 2013; Choi & Cai, 2010; Nikbin et al., 2016), little research has considered the mediating/moderating role of consumers’ psychological characteristics. For example, Li (2015) used perceived sense of betrayal and brand attachment as moderators; Zhang et al. (2015) demonstrated the mediating importance of perceived quality and brand reputation; Jalonen & Jussila (2016) explored the moderating role of perceived usefulness of negative information. To the authors’ knowledge, no research related to the low-cost flight industry has investigated two phenomena, already studied in other fields, related to consumer personality: (1) the choice difficulty (Lu et al., 2016; Park et al., 2013), and (2) the brand switcher (Al-Kwifi & Ahmed, 2015; Lei et al., 2017). The two phenomena—a confusion resulting from consumers’ difficulty in choosing products which reflects consumers’ uncertainty in making decisions (Anderson, 2003) and an habitual behaviour related to personality traits whereby an individual likes to try a range of products and may express loyalty to multiple brands within a product and service category (Quoquab et al., 2014)—are a somehow neglected area (Ranjbarian et al., 2016; Shiu, 2017) despite being very present in the tourism industry (Lu et al., 2016). In the low-cost flight sector, which is character emphasise d by reduced comfort levels and weakly differentiated services (Chou et al., 2023), the existence of brand switcher consumers tends to accentuate competitive pressure on companies. Similarly, the lowly characterization of services quality increases the difficulty of choice (Agarwal & Chatterjee, 2003), preventing consumers from making a fully informed decision, partly because of poorly differentiated prices and fares.

To fill this gap, the purpose of this study is to understand whether and how—with reference to the travel experience with low-cost airlines—1) brand switcher and 2) choice difficulty, influence the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty. To test the two hypotheses, a regression analysis was conducted on 260 respondents. The results confirmed the research hypotheses, offering important theoretical and managerial implications for the low-cost travel industry and, more indirectly, for tourist destinations.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1 Effects of negative events on brand switcher and brand loyalty

The marketing literature has extensively examined brand loyalty – defined as a stable commitment to repurchasing or re-sponsoring a selected product/service (Oliver, 1999). The topic has been studied according to both a behavioural approach (i.e., in terms of repeat purchases) and an attitudinal approach (i.e., in terms of preferences that incorporate the dispositional or psychological commitment of the consumer) (Aaker, 1991; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Oliver, 1999; Piper et al., 2022). The negative events can threaten brands’ legitimacy and destroy their reputation, by weakening consumer confidence (Coombs, 2007) which is an antecedent of brand loyalty. On this point, Votolato and Unnava (2006) classified trust-destroying negative events into two categories: competency and morality. The former involves management issues such as the firm being unable to fully meet the needs of the target audience. The second relates to the company’s inability to meet quality standards due to the lack of social responsibility or the violation of social norms. Notably, the latter type tends to elicit a stronger perception of betrayal and increases consumers’ propensity to boycott a brand or destination (Su et al., 2022). Indeed, consumer dissatisfaction with a product or a service is usually driven by a bad former brand experience (Bryson et al., 2013). Some scholars have linked this variable to product/service failures (Hegner et al., 2017; Kucuk, 2019; Zarantonello et al., 2018) and the consequent complaint (Bryson et al., 2013; Kucuk, 2018; Romani et al., 2015). Beyond bad experiences, brand hate can also be driven by functional or symbolic incongruity, as well as ideological incompatibility with the brand (Islam et al., 2019).

According to Sirgy et al. (1991), functional congruity can be defined as the match between a person’s beliefs about a product’s utilitarian (performance-related) attributes and said person’s referent attributes. Translated to the context of travel services, functional congruence reflects the match between tourists’ needs and the quality of the tourist service (Sirgy & Su, 2000). Oftentimes, the functional congruence of products or services is a significant factor in consumers’ purchase intentions and repeat purchases (Flanagin et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2015). By the same token, the functional incongruence between consumers’ needs/expectations and product/service quality leads to dissatisfaction, which can encourage negative emotions that then affect repeat purchases and brand loyalty. Meanwhile, symbolic incongruence is linked to a lacking alignment between self-image and brand image (Sirgy, 1991), which arises from the brand’s associations with negatively perceived persons (or groups), as well as negatively charged values, such as a lack of authenticity (Hegner et al., 2017). Both functional and symbolic congruence fall under self-congruity theory, which argues that people buy to not only to satisfy their basic needs, but also to consume a product’s symbolic meaning (Hosany & Martin, 2012). Notably, scholars have found that functional congruence positively impacts brand loyalty and customer loyalty (Claiborne & Sirgy, 2015). Since symbolic and functional incongruence are the main causes of brand hate (Islam et al., 2019), we expect them to have exert a negative impact on brand loyalty.

The last adverse event that triggers negative emotions is the ideological incompatibility with the brand, which results from commercial policies that consumers do not accept (Hegner et al., 2017). That is, consumers could see corporate behaviour as ideologically unacceptable based on legal, moral, or social norms. For example, the brand could engage in moral misconduct, deceptive communication, or inconsistent values, any of which might generate negative emotions that entail brand hate (Kucuk, 2010, 2018; Romani et al., 2015). One recent study found that consumers do not easily forget socially irresponsible behaviours, which can damage future prospects (Zarantonello et al., 2018). Compared to a functional inconsistency caused by a product/service failure, ideological/identity misalignment persists longer in consumers’ memories (Kucuk, 2019, 2021). In the context of travel, the ideological incompatibility of a brand, combined with negative events related to mass tourism (such as excessive tourism and environmental pollution) could galvanise a tourist boycott of a destination (Shaheer et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020).

For all these reasons, some scholars have posited the notion of anti-loyalty (Rindell et al., 2014) by linking it to negative events. In particular, some scholars have found that the most loyal consumers become the worst haters if they feel betrayed by the company (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008; Grégoire et al., 2009). But the intensity of the betrayal is influenced by the psychological profile of the consumer which is connected to the concept of brand switcher (Jacoby, 1971).

As conceptualised by Al-Kwifi and Ahmed (2015) and Wathne et al. (2001), brand switching refers to the interruption of a pre-existing relationship with one brand to create a new one with another brand. Brand switching is usually linked to the utility motivations or to the activation of a psychological process (Lei et al., 2017). In the first case, a new product/service is perceived as having greater advantages/utility than the historical product/service (Lam et al., 2010). Usually, consumers justify this brand change by expressing dissatisfaction with a negative experience with a product or service (Lei et al., 2017; Pancarelli & Forlani, 2018; Saeed & Azmi 2019). In the second case, the brand change triggers a process that provides psychological benefits to the consumer (Lei et al., 2017). This second perspective is based on social identity theory, which encompasses the socio-psychological factors behind why consumers switch brands (Lam et al., 2010). In this sense, brand switching is the way a person called a brand switcher expresses himself. A brand switcher is therefore a person who enjoys trying a range of products (Hung et al., 2011) and who can express loyalty to multiple brands within a product and service category (Jacoby, 1971). This implies that such people will make repeated purchases from several brands in a set (Quoquab et al., 2014). So psychological motivation changes the concept of brand switching because it transforms an occasional behaviour into a habitual behaviour linked to personality traits. Consequently, the psychological profile of a brand switcher negatively mediates the effect of negative events on brand loyalty, since such individuals, accustomed to changing brands, will have an extra motivation to reduce repeat purchases of that brand in the choice set. Therefore, we propose that:

H1. Brand switcher negatively mediates the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty.

2.2 Effects of negative events on choice difficulty and brand loyalty

Negative events could lead to uncertainty about one’s preferences, which is a primary source of difficulty in consumers’ decision-making (for further discussion, see Anderson 2003; Bettman et al., 1991; Olson, 2013). This sense of confusion creates a mental state of distress that hinders consumers’ ability to correctly process information and complicates the decision-making process (Walsh et al., 2007). In particular, Betman et al. (1991) suggested that consumers find it difficult to choose a product or service when the attributes are unclear or there are many alternatives. Consumers may also experience uncertainty when the sources of information contradict each other (West & Broniarczyk, 1998), which increases the complexity of the task and contributes to the choice difficulty. This issue of choice difficulty is more salient in the service sector, and particularly for tourist services (Lu et al., 2016). Consumers who decide to purchase travel services experience and perceive high levels of financial and emotional risk that stem from confusion (Buhalis & Law, 2008; Park et al., 2013; Turnbull et al., 2000).

Some scholars have classified consumer confusion into three dimensions: similarity, overload, and ambiguity confusion (Turnbull et al., 2000; Walsh et al., 2007; Walsh & Mitchell, 2008). Similarity refers to the choice difficulty resulting from the perceived physical similarity of goods and services (Walsh et al., 2007). Overload refers to the confusion derived from having an excess of information or available choices. The ambiguity confusion refers to the handling of unclear, misleading, ambiguous, or contradictory information relating to products/services (Leek & Kun, 2006; Walsh et al., 2007; Wang & Shukla, 2013). This last dimension especially galvanises brand accusations and generates disbelief towards products and companies. Remedying this problem requires that consumers gather more information, which may require more time, effort, and money. This effort translates into a decrease in satisfaction that can lead consumers to change brands (Walsh & Mitchell, 2008). However, recent studies have shown that consumer confusion levels can also have a positive impact on brand loyalty (Kurtulmus & Atalay, 2020). This may be because brand loyalty requires fewer comparisons between products (Hillman, 1994) and thus simplifies the process of choosing between alternatives by mitigating uncertainty. In particular, considering a certain set of alternatives or information overload, personality traits shape a different choice difficulty. This consideration is linked to a study by Lam (2007) which highlights the existence of a significant relationship between brand loyalty and the avoidance of uncertainty. Therefore:

H2. Choice difficulty positively mediates the relation between negative events and brand loyalty.

Since in many studies the nationality of tourists could be a discriminating variable (e.g., Brida et al., 2012; Piper et al., 2022), it was considered as a control variable in this study. However, no syllogisms were identified to suggest that the model should be specified based on nationality.

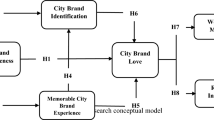

Therefore, on the basis of the previous hypotheses, it is possible to propose a conceptual model (Fig. 1).

3 Research methodology

To verify the hypotheses, we conducted a quantitative study involving the brand of a low-cost airline. A structured questionnaire was administered to a sample of Italians respondents, balanced in terms of age and gender (Sudman, 1980). Data were collected by trained interviewers for five weeks (every day from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.), between June and July, in typical tourist destinations of southern Italy. The interviewers intercepted potential respondents and asked them if they were tourists and if they would like to participate in the data collection. Participants were also asked to confirm whether they had used the company’s services at least once for domestic or international flights. Participants who had never used the company’s services were excluded from the collection. Those who answered positively were given the questionnaire. In accordance with the preferences of the respondents, the questionnaire was distributed in either a paper format or an electronic format through a link to the online platform Google Form which they could access with their mobile phone, tablet, or PC at home, in English or Italian (following the iterative approach proposed by Douglas & Craig 2007; all items were translated from English into Italian). In order to minimise bias, interviewers assured participants that their anonymity would be protected, that there were no right or wrong answers, and that their answers would only be used for scientific purposes (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

3.1 Questionnaire

Initially, the questionnaire briefly explained the purpose of the data collection. In section one, the questionnaire asked participants to indicate which of the negative events they encountered during their experience with the brand (Zarantonello et al., 2016). The sum of these dichotomous variables constituted the independent variable (which could thus assume values from 0 to 3). To avoid cognitive syllogisms and heuristics, the constructs were inserted in reverse order with respect to the framework (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Afterwards, we collected socio-demographic data (i.e., age, gender, level of education, annual income, and nationality). The survey then presented the measurement scales: (i) an 8-item scale measuring brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001); (ii) a 3-item scale measuring brand switching (Hung et al., 2011); and (iii) a 3-item scale measuring choice difficulty (Mariadoss et al., 2010). All items were rated using 7-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The questionnaire included an attention filter question (“If you read this question, answer 5”) in order to screen out inattentive respondents (Oppenheimer et al., 2009).

3.2 Sample

The analysis was conducted on a heterogeneous sample of 260 respondents. Twenty-seven participants were removed for failing the attention check or providing an incomplete questionnaire. The final sample of 233 people was 48.4% male, aged between 17 and 68 years old (M = 31.11, SD = 10.87), and belonging to different classes of annual income (Table 1). The sample was evenly distributed in terms of educational level (51.2% had at least a university degree) and nationality (48.1% Italians and 51.9% foreigners).

3.3 Data analysis

Before performing the regression analysis, we attempted to verify the multivariate normality assumption by conducting the Mardia test for multivariate asymmetry and kurtosis (Cain et al., 2017; DeCarlo, 1997; Mardia, 1970). Subsequently, to evaluate the threat of Common Method Variance (CMV), we used the Common Latent Factor (CLF) technique. We estimated a measurement model in which indicators were allowed to load on their theoretical construct and a common factor. The common variance was estimated as the square of the common factor of each path before standardization. Then, we performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to check the multi-item measures for reliability.

Following common protocol in the literature, we averaged the responses to the items for brand loyalty, brand switching and choice difficulty (Diamantopoulos et al., 2012). Finally, we conducted a path analysis that considered choice difficulty and brand switcher as mediators (from negative events to brand loyalty). Moreover, we performed a multi-group analysis to identify differences in the model based on nationality (Italians coded with ‘1’ and foreigners coded with ‘2’).

4 Results

4.1 Data validity and measures’ reliability check

The preliminary analysis of the data returned a Mardia’s multivariate skewness of b = 0.81, p = 0.099 and Mardia’s multivariate kurtosis of b = 328.21, p = 0.173. These results did not confirm the multi-normality of the data (Cain et al., 2017). Therefore, given the sample size, we followed the suggestions of Preacher et al. (2007) and performed bootstrapping (k = 5,000) to obtain multivariate normality. CLF returned a variance of 16.2%, lower than the threshold of 50% set by the common heuristic (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). This result suggests that there is no significant CMV bias in our data.

Since the Cronbach’s α coefficient for all scales was higher than 0.70, we can claim adequate internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994): Brand loyalty α = 0.81; choice difficulty α = 0.77; brand switcher α = 0.84. The fit statistics were also adequate: χ2/d.f. = 3.198, p < 0.001; GFI = 0.863; CFI = 0.924; NFI = 0.894; SRMR = 0.0445. As shown in Table 2, for each scale, the Construct Reliability coefficients (CR) and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indices were higher than the recommended levels of 0.70 and 0.50, respectively. Moreover, all CR were higher than the AVE. The diagonal of Table 2 indicates the square root of the AVE for each scale; these coefficients are higher than the corresponding correlation coefficients with other constructs considered in the model. Thus, the analysis suggests that the measurement model features robust discriminant and convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 1998).

4.2 Mediation analysis

The path analysis demonstrated that negative events are positively related to both choice difficulty (β = 0.139, p = 0.032) and brand switcher (β = 0.219, p < 0.001). While brand switcher had a negative effect on brand loyalty (β = − 0.181, p = 0.05), confirming H1, choice difficulty had a positive effect on brand loyalty (β = 0.150, p = 0.020), confirming H2 (Fig. 2). Finally, the direct effect between negative events and brand loyalty was not significant (β = − 0.094, p = 0.154).

We conducted a multi-group analysis to test whether the relationships between variables varied as a function of nationality. Thus, we compared a constrained model (with invariant parameters across the subgroups, Italians vs. foreigners) against the unconstrained model (with parameters free to change across the subgroups). The χ2 difference test between the constrained and unconstrained model did not reach significance (∆χ2 = 4.895, ∆d.f. = 4, p = 0.298), suggesting that the models are invariant across the two subgroups. This information, combined with ∆CFI = 0.001 < 0.010 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), led us to conclude that the relationships between variables do not vary as a function of respondents’ nationality.

5 Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether negative events in the low-cost airline sector influence loyalty to the transport carrier brand.

It has been also considered two consumer psychological characteristics: the tendency to switch brands (brand switcher) and the difficulty in choosing between alternatives (choice difficulty). Additionally, the analysis encompassed three types of negative events: (i) experiences of dissatisfaction with reference to the brand; (ii) Consumers’ negative associations with other brand-users; (iii) business activities that do not align with consumer ethical standards, including sufficient sustainability performance (Zarantonello et al., 2016).

Generally, we expected that unsatisfactory travel experiences will harm tourists’ trust in the brand. Indeed, our results confirmed that adverse events related to an airline company have a negative impact on the carrier’s brand loyalty, which aligns with the literature (see Coombs 2007; Su et al., 2022; Votolato & Unnava, 2006). Furthermore, we expected that the occurrence of negative events increases tourists’ likelihood of brand switching (Lei et al., 2017) and choice difficulty (Anderson, 2003; Olson, 2013). These factors would thus create interesting consequences for the marketing policies of the low-cost airline company.

In support of H1, we found that the relationship between the negative event and brand loyalty is negatively mediated by brand switcher. Indeed, customers with a more pronounced propensity to switch suppliers tended to change brands more readily in the case of negative events—an apparent show of diminishing brand loyalty. In other words, the habitual behaviour of changing brands within a set of choices, deriving from motivations linked to a consumer’s psychological process, negatively accentuates the impact of a negative event on brand loyalty. Therefore, the negative event reduces brand loyalty more consistently when the consumer has a psychological profile of brand switcher.

However, the results also showed—in support of H2—that a negative event involving a transport brand leads tourists to a state of uncertainty and confusion that can bolster brand loyalty as a way to reduce risk. In other words, the visitor may choose a trusted brand to avoid potentially conflicting information (Kurtulmus & Atalay, 2020; Walsh et al., 2007). In short, our study’s core contribution is confirming that the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty is negatively mediated by brand switching, but positively mediated by choice difficulty. This confirm, in particular, that brand loyalty reduces the need to compare products, and can thus be used to resolve ambiguous or contradictory information.

Finally, the model applied in the study showed that nationality has no influence on tourist behaviour or the perception of negative events with respect to brand loyalty. In other words, the emotional and irrational factors are inherent to visitors and not culturally determined.

6 Theoretical and managerial implications

Findings contain several theoretical, managerial, and policy implications. From a theoretical perspective, this study contributes to the debate on identifying the profile of the brand switcher – a person who expresses multi-brand loyalty within a category of products and services – for the airline travel sector and who can, because of a negative event, help decrease brand loyalty. This finding adds explanation to the theory that the most loyal consumers become the worst haters when they feel betrayed by the company (Grégoire & Fisher, 2008; Grégoire et al., 2009) and in particular when they have a psychological profile of brand switcher.

Furthermore, understanding the determinants of brand loyalty, such as choice difficulty, is essential to improving customer relationships, obtaining positive word-of-mouth, and increasing revenues (Baumann et al., 2017; Bock et al., 2016). In particular, our results demonstrating that choice difficulty positively reduces the impact of the negative event on brand loyalty, reinforce the theory according to which there is a positive relationship between brand loyalty and uncertainty avoidance (Lam, 2007). In other words, a choice difficulty could generate a negative effect on the loyalty of those consumers who, being generally uncertain in their choices, try to simplify the purchasing process by opting for the usual brand which is less compared with the others. Also in this case, the uncertainty in the choice can be influenced by psychological factors of the consumer which shape the choice difficulty differently.

From a managerial perspective, our results suggest that airline companies can avoid the deleterious effects of negative events on brand loyalty by investing in better customer segmentation (Almeida-Santana & Moreno-Gil, 2018; Chen et al., 2017). Properly profiling customers based on their tendency to avoid difficult choices or switch brands would help marketers better define their loyalty plans. However, companies should invest in differentiation strategies, aiming for a unique image and communicating higher quality (e.g., quick resolution of adverse problems, kindness, all-inclusive, punctuality, transparent pricing) also with the intention of moving out of the category focused only on low cost, in order to attract and retain tourists. Marketers might invest in more intensive communication campaigns in order to increase brand recall among consumers who have to make a decision when the set of choices is complex or overloaded with alternatives.

Finally, from a broader point of view, the ability of low-cost airlines to deal constructively with negative events can be a resource for the destination area and its promotion policies, both in terms of perceived quality, image of local infrastructure serving tourists and problem-solving capabilities. Joint loyalty programs between airlines and tourist destinations might create synergies and more brand loyalty by discouraging switching. Airlines that can mitigate the consequences of negative events can produce real competitive advantages for both them and the destinations they serve. This is because in the travel industry, people’s loyalty to a destination depends on their evaluation of said place, which is a complex interaction between place attributes and the traveller’s experience prior to arrival (e.g., with the mode of travel) (De Nisco et al., 2015; Weaver et al., 2007). In fact, some studies show that loyalty in the travel sector generally reflects service effectiveness in both the tourism industry (Han & Hyun, 2018; Hwang et al., 2019) and the airline industry (Akamavi et al., 2015; Hapsari et al., 2017).

7 Limitations and future research

The study features some limitations that may represent valuable avenues for future research. First, we want to emphasie that we considered negative events stemming from endogenous elements or behaviours attributable to the brand; however, there are other events caused by exogenous elements or circumstances that could also impact brand (or destination) loyalty. For example, today’s consumers have seen their choices rapidly destabilised by pandemics, conflicts, and a whirlwind competitive environment (Iyengar & Lepper, 2000) –all of which have elevated the levels of financial, emotional, and environmental risk (Buhalis & Law, 2008; Turnbull et al., 2000). In such situations, companies may find competitive advantage in supporting economic, social, or environmental stability, as these factors can impact vital aspects of their business – like reputation and brand loyalty – as well as tourism more generally (Arslan, 2020).

Second, we used brand loyalty as a dependent variable and a low-cost airline as a focal brand. Because this firm relies on low-cost transportation, it is possible that ticket price is an underlying driver of our results.

Therefore, future studies could assess this factor by including other carriers and controlling ticket costs as a covariate variable. In addition, it might be interesting to test the presented model against different types of negative events. In this vein, scholars could integrate Attribution Theory, which has been regularly used to study customers’ different reactions to failures (Folkes, 1984; Folkes & Kotsos, 1986).

Furthermore, future research could investigate the effects of negative events on tourists’ experiences during travel to a destination and try to mitigate the impact of events on brand and destination loyalty by considering destination loyalty as a dependent variable.

Future research could also verify how the destination’s characteristics can impact consumer choices (Di Vittorio et al., 2020) by mitigating the effect of negative events during the trip. Relatedly, scholars could determine the degree to which past positive experiences and satisfaction can also ameliorate said effects (Guido, 2014).

Finally, to generalise the results, in this study, the sample used for the analyses is balanced in terms of gender, age, and educational qualification. However, this could be a limitation that future research will overcome by focusing on the demographic characteristics of tourists in specific destinations.

8 Conclusions

This study deepens the analysis of negative events involving brands of low-cost companies with consequent risk of reduction of brand loyalty. However, this study shows that some psychological variables could dampen this negative effect. Choice difficulty (reflecting a distressed mental state that is typical of a confused consumer) can mediate the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty. In such situations, confused consumers simplify their choices by preferring trusted brands, even in the case of negative events.

Additionally, a brand switcher - someone who often jumps among various brands - negatively mediates the relationship between negative events and brand loyalty. That is, consumers who habitually change brands within a product category, in the presence of negative events in reference to a brand, are induced to definitively exclude it from the set of chosen brands.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: Free Press.

Agarwal, M. K., & Chatterjee, S. (2003). Complexity, uniqueness, and similarity in between-bundle choice. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 12, 358–376.

Akamavi, R. K., Mohamed, E., Pellmann, K., & Xu, Y. (2015). Key determinants of passenger loyalty in the low-cost airline business. Tourism Management, 46, 528–545.

Al-Kwifi, O., & Ahmed, Z. U. (2015). An intellectual journey into the historical evolution of marketing research in brand switching behaviour - past, present, and future. Journal of Management History, 21(2), 172–193.

Almeida-Santana, A., & Moreno-Gil, S. (2018). Understanding tourism loyalty: Horizontal vs. destination loyalty. Tourism Management, 65, 245–255.

Anderson, C. J. (2003). The psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 139–167.

Arslan, I. K. (2020). The importance of creating customer loyalty in achieving sustainable competitive advantage. Eurasian Journal of Business Management, 8, 11–20.

Baumann, C., Hoadley, S., Hamin, H., & Nugraha, A. (2017). Competitiveness Vis-à-Vis service quality as drivers of customer loyalty mediated by perceptions of regulation and stability in steady and volatile markets. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 36, 62–74.

Bettman, J., Johnson, E. J., & Payne, J. W. (1991). Consumer decision making. In Robertson T.S., & Kassarjian H.H. (Eds.), Handbook of Consumer emphasise r Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 50–84.

Bock, D. E., Mangus, S. M., & Folse, J. A. G. (2016). The road to customer loyalty paved with service customization. Journal of Business Research, 69(10), 3923–3932.

Brida, J. G., Meleddu, M., & Pulina, M. (2012). Factors influencing the intention to revisit a cultural attraction: The case study of the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rovereto. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 13, 167–174.

Bryson, D., Atwal, G., & Hultén, P. (2013). Towards the conceptualization of the antecedents of extreme negative affect towards luxury brands. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 16, 393–405.

Buhalis, D., & Law, R. (2008). Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the internet-the state of eTourism research. Tourism Management, 29(4), 609–623.

Cain, M. K., Zhang, Z., & Yuan, K. H. (2017). Univariate and multivariate skewness and kurtosis for measuring nonnormality: Prevalence, influence, and estimation. Behaviour Research Methods, 49(5), 1716–1735.

Caruana, A. (2002). Service loyalty: The effects of service quality and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8), 811–828.

Chang, A., Hsieh, S. H., & Tseng, T. H. (2013). Online brand community response to negative brand events: The role of group eWOM. Internet Research, 23(4), 486–506.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93.

Chen, S. C., Raab, C., & Tanford, S. (2017). Segmenting customers by participation: An innovative path to service excellence. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(5), 1468–1485.

Choi, S. H., & Cai, L. A. (2010). Tourist attribution and the moderating role of loyalty. Tourism Analysis, 15(6), 729–734.

Chou, S., Chen, C. W., & Wong, M. (2023). When social media meets low-cost airlines: Will customer engagement increase customer loyalty?. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 100945.

Claiborne, C., & Sirgy, M. J. (2015). Self-image congruence as a model of consumer attitude formation and behaviour: a conceptual review and guide for future research. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 1990 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference.

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organisation reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176.

Currie, C., & Falconer, P. (2014). Maintaining sustainable island destinations in Scotland: The role of the transport–tourism relationship. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 3(3), 162–172.

Curry, N., & Gao, Y. (2012). Low-cost airlines—A new customer relationship? An analysis of service quality, service satisfaction, and customer loyalty in a low-cost setting. Services Marketing Quarterly, 33(2), 104–118.

De Nisco, A., Mainolfi, G., Marino, V., & Napolitano, M. R. (2015). Tourism satisfaction effect on general country image, destination image, and post-visit intentions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 21(4), 305–317.

DeCarlo, L. T. (1997). On the meaning and use of kurtosis. Psychological Methods, 2(3), 292–307.

Di Vittorio, A., de Cosmo, M. L., Iaffaldano, N., & Piper, L. (2020). Identity processes in marketing: Relationship between image and personality of tourist destination, destination self-congruity and behavioural responses. Mercati e CompetitivitÃ, 2, 13–40.

Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449.

Douglas, S. P., & Craig, C. S. (2007). Collaborative and iterative translation: An Alternative Approach to Back Translation. Journal of International Marketing, 15(1), 30–43.

Flanagin, A. J., Metzger, M. J., Pure, R., Markov, A., & Hartsell, E. (2014). Mitigating risk in ecommerce transactions: Perceptions of information credibility and the role of user-generated ratings in product quality and purchase intention. Electronic Commerce Research, 14(1), 1–23.

Folkes, S. (1984). Consumer reactions to product failure: An attributional approach. Journal of Consumer Research, 10(4), 398–409.

Folkes, S., & Kotsos, B. (1986). Buyers’ and sellers’ explanations for product failure: Who done it? Journal of Marketing, 50(2), 74–80.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Grégoire, Y., & Fisher, R. (2008). Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(2), 247–261.

Grégoire, Y., Tripp, T. M., & Legoux, R. (2009). When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. Journal of Marketing, 73, 18–32.

Guido, G. (2014). Customer satisfaction. In C. L. Cooper (Ed.), Wiley Encyclopedia of Management (pp. 139–147). New Jersey: Wiley.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Han, H., & Hwang, J. (2017). In-flight physical surroundings: Quality, satisfaction, and traveller loyalty in the emerging low-cost flight market. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(13), 1336–1354.

Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2018). Role of motivations for luxury cruise traveling, satisfaction, and involvement in building traveler loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 70, 75–84.

Hapsari, R., Clemes, M. D., & Dean, D. (2017). The impact of service quality, customer engagement and selected marketing constructs on airline passenger loyalty. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 9(1), 21–40.

Hegner, S. M., Fetscherin, M., & Delzen, M. (2017). Determinants and outcomes of brand hate. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 26(1), 13–25.

Hillman, G. P. (1994). Making self-assessment successful. The TQM Magazine, 6(3), 29–30.

Hosany, S., & Martin, D. (2012). Self-image congruence in consumer behaviour. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 685–691.

Hung, K., Li, S. Y., & Tse, D. K. (2011). Interpersonal trust and platform credibility in a chinese multibrand online community. Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 99–112.

Hwang, E., Baloglu, S., & Tanford, S. (2019). Building loyalty through reward programs: The influence of perceptions of fairness and brand attachment. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 19–28.

Iordanova, E. (2017). Tourism destination image as an antecedent of destination loyalty: The case of Linz, Austria. European Journal of Tourism Research, 16, 214–232.

Islam, T., Attiq, S., Hameed, Z., Khokhar, M., & Sheikh, Z. (2019). The impact of self-congruity (symbolic and functional) on the brand hate. British Food Journal, 121(1), 71–88.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing? Journal of Personal Social Psychology, 79(6), 995–1006.

Jacoby, J. (1971). A model of multi-brand loyalty. Journal of Advertising Research, 11(3), 25–31.

Jalonen, H., & Jussila, J. (2016, September). Developing a conceptual model for the relationship between social media behavior, negative consumer emotions and brand disloyalty. In Conference on e-Business, e-Services and e-Society, 34–145. Springer, Cham.

Jiang, H., & Zhang, Y. (2016). An investigation of service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty in China’s airline market. Journal of air transport management, 57, 80–88.

Kartsan, P. (2022). Transport communication and organization of transport services in the tourism sector. Transportation Research Procedia, 61, 180–184.

Khamitov, M., Grégoire, Y., & Suri, A. (2020). A systematic review of brand transgression, service failure recovery and product-harm crisis: Integration and guiding insights. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(3), 519–542.

Khan, M. A., Yasir, M., & Khan, M. A. (2021). Factors affecting customer loyalty in the services sector. Journal of Tourism and Services, 22(12), 184–197.

Kucuk, S. U. (2010). Negative double jeopardy revisited: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Brand Management, 18(2), 150–158.

Kucuk, S. U. (2018). Macro-level antecedents of consumer brand hate. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 35(5), 555–564.

Kucuk, S. U. (2019). Brand hate: Navigating consumer negativity in the digital world. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

Kucuk, S. U. (2021). Developing a theory of brand hate: Where are we now? Strategic Change, 30, 29–33.

Kurtulmus, F. B., & Atalay, K. D. (2020). The effects of consumer confusion on hotel brand loyalty: An application of linguistic nonlinear regression model in the hospitality sector. Soft Computing, 24, 4269–4281.

Lam, D. (2007). Cultural influence on proneness to brand loyalty. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 19(3), 7–21.

Lam, S., Ahearne, M., Hu, Y., & Schillewaert, N. (2010). Resistance to brand switching when a radically new brand is introduced: A social identity theory perspective. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 28–146.

Leek, S., & Kun, D. (2006). Consumer confusion in the chinese personal computer market. Journal of Product Brand Managing, 15(3), 184–193.

Lei, S., Yuwei, J., Zhansheng, C., & Dewall, C. (2017). Social exclusion and consumer switching behaviour: A control restoration mechanism. Journal of Consumer Research, 44(1), 99–117.

Li, Y. (2015). The severity of negative events in enterprises affects consumers’ brand attitude. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43(9), 1533–1546.

Lu, A. C., Gursoy, C., Dogan, I., & Rong, C. (2016). Antecedents and outcomes of consumers’ confusion in the online tourism domain. Annal of Tourism Research, 57(6), 76–93.

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika, 57(3), 519–530.

Mariadoss, B. J., Echambadi, R., Arnold, M. J., & Bindroo, V. (2010). An examination of the effects of perceived difficulty of manufacturing the extension product on brand extension attitudes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(6), 704–719.

Mileti, A., Frasca, C., & Guido, G. (2011). La relazione tra comportamento di spesa e abbandono dei clienti nel mercato delle carte di credito. Economia dei Servizi, 6(1), 47–60.

Nikbin, D., Hyun, S. S., Iranmanesh, M., Maghsoudi, A., & Jeong, C. (2016). Airline travelers’ causal attribution of service failure and its impact on trust and loyalty formation: The moderating role of corporate social responsibility. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(4), 355–374.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. New York: (third ed.) McGraw–Hill.

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44.

Olson, E. L. (2013). It’s not easy being green: The effects of attribute tradeoffs on green product preference and choice. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 171–184.

Oppenheimer, D. M., Meyvis, T., & Davidenko, N. (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(4), 867–872.

Park, M., Jung, K. M., & Park, D. H. (2013). Optimal post-warranty maintenance policy with repair time threshold for minimal repair. Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 111(2), 147–153.

Pencarelli, T., & Forlani, F. (2018). The experience logic as a new perspective for marketing management. Springer.

Piper, L., Prete, M. I., Palmi, P., & Guido, G. (2022). Loyal or not? Determinants of heritage destination satisfaction and loyalty. A study of Lecce, Italy. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(5), 593–608.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Nathan, J. Y., Lee, & Podsakoff, P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioural Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Quoquab, F., Mohd. Yasin, N., & Abu Dardak, R. (2014). A qualitative inquiry of multi-brand loyalty: Some propositions and implications for mobile phone service providers. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 26(2), 250–271.

Ranjbarian, B., Abdollahi, S. M., & Ghorbani, H. (2016). Potential antecedents and consequences of online confusion in tourism industry. Proceedings of the 10th International conference on IEEE, Isfahan.

Rindell, A., Strandvik, T., & Wilén, K. (2014). Ethical consumers’ brand avoidance. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 23, 114–120.

Romani, S., Grappi, S., Zarantonello, Z., & Bagozzi, R. (2015). The revenge of the consumer! How brand moral violations lead to consumer anti-brand activism? Journal of Brand Management, 22(8), 658–672.

Saeed, M., & Azmi, I. (2019). The nexus between customer equity and brand switching behaviour of millennial muslim consumers. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 8(1), 62–80.

Shaheer, I., Insch, A., & Carr, N. (2018). Tourism destination boycotts. Are they becoming a standard practise? Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 129–132.

Shiu, J. Y. (2017). Investigating consumer confusion in the retailing context: The causes and outcomes. Total Quality Management Business Excellence, 28(7–8), 746–764.

Sirgy, M. J., & Su, C. (2000). Destination image, self-congruity, and travel behaviour: Toward an integrative model. Journal of Travel Research, 38(4), 340–352.

Sirgy, M. J., Johar, J., Samli, A. C., & Claiborne, C. B. (1991). Self-congruity versus functional congruity: Predictors of consumer behaviour. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 19(4), 363–375.

Su, L., Jia, B., & Huang, Y. (2022). How do destination negative events trigger tourists’ perceived betrayal and boycott? The moderating role of relationship quality. Tourism Management, 92, 104536.

Sudman, S. (1980). Improving the quality of shopping center sampling. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 423–431.

Thompson, K., & Schofield, P. (2007). An investigation of the relationship between public transport performance and destination satisfaction. Journal of transport geography, 15(2), 136–144.

Turnbull, P. W., Leek, S., & Ying, G. (2000). Customer confusion: The mobile phone market. Journal of Marketing Management, 16, 143–163.

Votolato, N., & Unnava, H. (2006). Spillover of negative information on brand alliances. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(2), 196–202.

Walsh, G., & Mitchell, W. V. (2008). The effect of consumer confusion proneness on word of mouth, trust, and customer satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 44(06), 838–859.

Walsh, G., Hennig-Thurau, T., & Mitchell, V. W. (2007). Consumer confusion proneness: Scale development, validation, and application. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(7–8), 697–721.

Wang, Q., & Shukla, P. (2013). Linking sources of consumer confusion to decision satisfaction: The role of choice goals. Journal of Psychology and Marketing, 30(4), 295–304.

Wathne, K., Biong, H., & Heide, J. (2001). Choice of supplier in embedded markets: Relationship and marketing program effects. Journal of Marketing, 652, 54–66.

Weaver, D. (2007). Toward sustainable mass tourism: Paradigm shift or paradigm nudge? Tourism Recreation Research, 3(3), 65–69.

West, P., & Broniarczyk, S. (1998). Integrating multiple opinions: The role of aspiration level on consumer response to critic consensus. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 38–51.

Wu, J. H., Wu, C. W., Lee, C. T., & Lee, H. J. (2015). Green purchase intentions: An exploratory study of the taiwanese electric motorcycle market. Journal of Business Research, 68(4), 829–833.

Yu, Q., Mcmanus, R., Yen, D., & Li, X. (2020). Tourism boycotts and animosity: A study of seven events. Annals of Tourism Research, 80.

Zarantonello, L., Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2016). Brand hate. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 25(1), 11–25.

Zarantonello, L., Romani, S., Grappi, S., & Fetscherin, M. (2018). Trajectories of brand hate. Journal of Brand Management, 25(6), 549–560.

Zhang, T. C., Kandampully, J., & Bilgihan, A. (2015). Motivations for customer engagement in Online Co-Innovation Communities (OCCs): A conceptual framework. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 6(3), 311–328.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Cosmo, L.M., Piper, L., Mileti, A. et al. The influence of negative travel-related experience on tourist’s brand loyalty. Ital. J. Mark. 2023, 351–368 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00075-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-023-00075-2