Abstract

In this paper, we analyze more than 16 million Twitter messages related to the 2022 war in Ukraine to examine the effects of multiple exposure to messages conveying intense anxiety or positivity on Twitter user behavior. We first analyzed a data-set covering a 3-month pre-war period to derive baseline anxiety and positivity levels. Subsequently, we compared the anxiety and positivity levels during the first 3 months after the war started in relation to the baseline. Our analysis indicates that the initial multi-exposure to intense anxiety is subsequently associated with a weaker expression of positivity as compared to users who initially have predominantly been exposed to positive messages. Moreover, anxiety-exposed users exhibit anxiety levels higher than their baseline in the post-exposure phase (i.e. during the second and third month of the war). In contrast, positivity-exposed users consistently show higher intensity of positivity and do not cross their baseline level of anxiety in the post-exposure phase. The low levels of positivity after an initial exposure to intense anxiety point to potentially disruptive mid-term effects of anxiety-conveying messages. Moreover, our results also point to the undoing effects that positive messages had in the early stages of the war.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emotional messages conveyed via social media can lead to massive-scale emotional contagion (see, e.g., [29]) and may also shape people’s judgement and perceptions of reality [7, 15]. For example, jealousy is known to lead to undesirable actions, such as obsessively monitoring communication or whereabouts of another or even act violently [44]. Prior research has also shown that not only a direct exposure to an emotion may lead to a certain type of behavior, but also a perception of how one would hypothetically feel in a particular situation. Along these lines, the perception of a hypothetical feeling has already been shown to be beneficial in making decisions regarding financial choices, body weight regulation, and better time management [23].

In recent years, significant parts of society have also been expressing their emotions on online social networks [51]. In this context, Twitter is a popular platform for instant information sharing, expressing opinion, as well as organizing various actions and social movements (see, e.g., [20, 46, 50]).

Thus far, researchers found no evidence that people communicate less emotionally or less personally via online social networks than in a face-to-face setting [12]. For example, Kramer et al. [29] showed that emotional content produced and consumed on social media affects the emotional state of users exposed to such messages. Thus, emotions communicated in social media posts can be contagious and may predict the diffusion rates of messages over online social networks (see, e.g., [8, 27, 29, 33]). However, to the best of our knowledge, previous studies did not systematically investigate changes in the behavior of social media users who have been repeatedly exposed to emotional content over a time span of several months. Our research thus contributes to a better understanding of how multi-exposure to emotional content, especially during acts of violence, influences user activity and information sharing on large social media platforms, such as Twitter.

For the purposes of this paper, we analyze the effects of multi-exposure to two types of emotions, each deliberately chosen as a representative for the positive and negative emotional valence respectivelyFootnote 1 – namely anxiety and positivity as identified by Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count tool (LIWC). For our case study, we focus on the events following the early stage of the 2022 war in Ukraine. In particular, we explore whether the initial exposure to anxiety and positivity has a subsequent impact on the emotional tone of Twitter users and whether it leads to an observable change in their messaging behavior. We define an exposure that happens during the first month of the war as the initial exposure. The repeated exposure (of the same users) to anxiety or positivity during the second and third months of the war then constitute multiple exposures. Moreover, we consider the 3 months before the war started our baseline phase, the first month of the war is the initial exposure phase, while the second and third month are the post-exposure phase (i.e. the phase where the repeated/multi-exposures happen).

This paper is an extension and follow-up of the analysis reported in [34]. In our previous paper, we focused on the emergence of temporal edges in the messaging network resulting from messages of death anxiety, emotional pain, as well as positivity, as a response to terror attacks. In contrast, this paper significantly extends the preliminary work by addressing the effects of exposure to intense anxiety and positivity on human social media behavior in the first three months of the war in Ukraine.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. “Related Work” we summarize related studies. Our research method is outlined in Sect. “Research Procedure”. Section “Results” presents the main findings which are subsequently discussed, along with the limitations to our paper, in Sect. “Discussion”. We conclude the paper and outline future research directions in Sect. “Conclusion”.

Related Work

There is a wide range of studies on the effects of emotions in a social media context. In this section, we will focus our summary of related work to the studies that report on emotions experienced during acts of violence (Section “Emotional Responses to Acts of Violence”) and those that report on the effects of emotions on human behavior in online social media (Section “Effects of Emotions on Human Behavior on Online Social Media”).

Emotional Responses to Acts of Violence

Prior research has shown that strong emotions triggered by human-made acts of violence (such as war and terrorist attacks), have a significant impact on human perceptions, decisions making process, and memories [5, 15]. In their study on the emotional impact of the 9/11 attack, [5] demonstrated that negative emotions can be re-triggered just by looking at a photograph of a terror attack, even 12 months after the attack happened. Such re-triggered negative emotions were also shown to have predictable effects on human behavior. For instance, anger was highly associated with support for military action (as a response to the terror attack), while fear predicted avoidant behaviors.

When individuals affected by a traumatic event are unable to talk about their experience but instead only think about it, they face a high risk to develop psychological and other health issues [39]. Supporting this argument, [40] found that talking about a trauma builds a positive emotional atmosphere (including the feelings of hope, trust, solidarity) and may strengthen post-traumatic mental/emotional growth. The positive effects of social sharing of emotions in times of terror were also demonstrated in [41]. The authors found that sharing of emotions related to the 2014 terrorist attack in Madrid predicted superior social integration and perceptions of hope, solidarity, and contentment of those affected.

The public generally responds to crises in a negative tone. For example, [21] found that terrorist attacks evoked anger, fear, and sadness, while [26] found a significant increase in negative tweets following the 2014 Isla Vista campus shooting, the 2015 Northern Arizona University shooting, and the 2015 Umpqua Community College Shooting.

The effects of the 2015 Paris terrorist attack on collective emotions have been studied in [18]. The study showed that negative emotions remained at an intense level for more than a week since the attack occurred. In addition, [41] argued that acts of violence lead to a heightened anxiety and depression for several months following a traumatic event. Along these lines, [28] reported on an increase in depressive symptoms spanning four weeks after the 9/11 attack, while [22] reported on a corresponding increase following the Israel-Lebanon war.

In their study on the reactions to the Persian Gulf War, [39] identified a “silent" dimension of coping with a trauma. Those affected by the event do not only actively talk about it but also heavily think about the event. In this sense, [39] found that people talk about the event for two weeks before they enter a stage where they think about the event without talking about it. This latter stage lasts relatively longer than the former (approx. 6 weeks) and in this stage, people tend to exhibit behavioral and emotional difficulties, including hostility and distress.

However, some studies also investigated the role of pro-social behavior and messages of compassion and encouragement. In fact, according to [16], positive emotions generally co-exist alongside negative emotions during acts of violence. Along these lines of studies, [10] explored the role of compassion communicated by the stakeholders during organizational crises and found that it fosters credibility and trust. Moreover, [13] found that people tend to exhibit solidarity and commitment during painful experiences. Among other forms of pro-social behavior, commemoration has been shown to inspire pride, gratitude, and admiration for those who sacrifice their lives for the sake of the nation [2, 48]. In addition, [18] indicates that those who highly participated in a collective sharing of emotions related to the 2015 Paris attack, exhibited pro-social behavior in the months that followed.

Effects of Emotions on Human Behavior on Online Social Media

Even a very brief exposure to emotional content has been shown to trigger emotional engagement in affected users [9]. Multiple studies also show the contagious nature of emotions that are communicated via online social networks (see, e.g., [11, 29, 31, 49]) and showed that emotions spread rapidly and have a potential to be adopted by large online communities. Furthermore, even very common events may produce measurable effects. For example, [11] found that users who experience rainfall will be influenced by the weather conditions while posting their status messages. As a result, a gloomy mood was also observed in their friends’ status messages who did not experience this particular weather condition. Lu and Hong [36] found an emergence of wide-spread negative emotions (such as anger, resentment and pain) in online social networks related to COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to the potential of emotions to spread and get adopted among social media users, another line of studies focused on the role of emotions in message propagation. One of such studies is presented in [4], where the authors studied tweets that have been sent following the 2013 terrorist event in Woolwich, London. The study indicates that positive tweets spread for a longer time period on Twitter as compared to negative tweets. The study further found that emotional intensity plays a considerable role, e.g. antagonistic tweets (such as messages that convey high-tension and racism) die out more quickly than those with low levels of tension. Conversely, tweets conveying a positive tone are propagated further and longer via retweeting, indicating that users are more inclined to spread positive messages in times of crisis (see also [30]). In contrast, [19] found that in some events negative messages spread for a longer time period than positive ones.

Researchers also argued that negative emotions cause stronger and faster emotional and behavioral responses than neutral or positive emotions [3]. For example, negative emotions were associated with a boosted user activity in online forums [6], while [32] found that the direct exchange of angry messages among users is characteristic for a frequent message-sending behavior. In addition, [38] examined how the exposure to strongly negative news stories on Twitter impacts user behavior and found that affected users felt more angry and searched further information about the stories more willingly as compared to those who were exposed to weakly negative stories only.

Research Procedure

Our hypotheses are based on related studies which provide cues on human behavior after exposure to emotionally negative online content. We particularly focus our attention to the effects of multi-exposure, where a user is repeatedly exposed to negative content in contrast to being exposed only once. One related study is provided by Wang et al. [47], who examined the effects of multi-exposure to misinformation on human behavior. While the effect of misinformation is not in focus of our study, we acknowledge the concept of multi-exposure. In this context, [47] observed behavioral changes, such as a boosted URL sharing behavior as well as a change in the use of emotional messages including words related to conflict and swearing.

Considering the concept of multi-exposure, our hypotheses are defined as follows:

- \(H_1\)::

-

Users, who are multi-exposed to highly emotional personal reports of the war in Ukraine, will adopt the emotional tone of the tweets they were exposed to. As a rationale behind this hypothesis, we refer to the findings of Garcia and Rime [18] who analyzed the collective adoption of emotions following the 2015 Paris terror attack. Their study indicates that negative emotions related to the terror event remained intense in the short-term aftermath of the attack.

- \(H_2\)::

-

Multiple exposures to a specific emotion will amplify the subsequent emotional tone of the exposed users. Previous studies on the effects of negative emotions on human behavior showed that negative emotions lead to a higher emotional and behavioral response than positive emotions [6]. Similarly, [38] pointed to the activation effect of negative emotions. In particular, strongly negative stories on Twitter led to angrier expressions by the exposed users, while [33] found characteristic patterns related to the way people exchange emotions in their direct communication. Along these lines, anger was shown to boost the exchange of more anger.

- \(H_3\)::

-

Users exposed to a high intensity of anxiety will increase their activity on Twitter. After studying Twitter responses related to the 2018 false Hawaii missile alert, [25] found that anxiety is a particularly interesting emotion as it tends to linger even in the aftermath of a traumatic event and the feeling is immune to message corrections. Several studies have reported on a link between the exposure to anxiety-related messages and increasingly anxious responses. For example, Stevens et al. [45] found that individuals who have been exposed to anxiety-conveying Covid-19 news articles also responded increasingly anxious themselves. Similar findings were reported in [35], who found that anxiety related to Covid-19 news encouraged panic hoarding behavior and a heightened expression of anger and frustration on Twitter.

To examine the effects of multiple exposure to personal messages conveying anxiety, we applied the the following research procedure: (1) data extraction, (2) data pre-processing, (3) user sampling, (4) baseline construction, and (5) data analysis, as outlined in the subsequent sections.

Data Extraction

We used Twitter’s public API with academic research access to obtain the tweets related to the war in Ukraine. In particular, we monitored Twitter search terms (including hashtags and keywords) related to the event. The list was iteratively updated as the first month of the war progressed. Our full list of search terms is shown in Table 1. In total, we extracted 193,948,858 tweets in English language.

Data Pre-Processing

Since a tweet may contain more than one search term, we checked the data-set for duplicate entries. Upon the removal of duplicates, the data-set counted 189,854,201 tweets.

Next, we processed the data-set using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count tool (LIWC) to detect the presence and intensity of positivity and anxiety. Moreover, we also detected the presence of personal pronouns to identify personal messages.

User Sampling Procedure

The procedure we followed for user sampling is shown in Fig. 1. To select a sample of Twitter users for our study, we used tweets that include personal pronouns and are included in the 97th percentile (i.e. the top 3 percent) of the anxiety scores in our data-set. The reason for such a filtering procedure was to avoid any instances of false positives (in terms of emotion scores) and to keep the size of the pool of users manageable. Next, we filtered the messages to include only those that have been retweeted or quotedFootnote 2 as evidence for a direct exposure to anxiety-filled messages. As a result of this message-filtering procedure, we identified users who retweeted or quoted messages that convey personal and anxiety-filled reports about the war.

This procedure resulted in 381,533 users who have been exposed to messages conveying high levels of anxiety. Since in this paper we are especially interested in the effects of multiple exposure, we included only those users who were exposed to multiple messages conveying anxiety (based on the 98th percentile, see also Fig. 1).

In order to select the comparison group, we searched for users who are exposed to personal messages conveying high levels of positivity. For the sampling procedure, we followed the same procedure as described above (see also Fig. 1).

Examples of personal tweets conveying high levels of anxiety and positivity are presented in Table 2.

The sampling procedure resulted in three subsamples of users: (1) those who are exclusively multi-exposed to high anxiety (2955), (2) those who are exclusively multi-exposed to high positivity (4597), and (3) those who are multi-exposed to high anxiety as well as high positivity (4386 users) (hereafter referred to as mixed exposure).

To keep the subsequent data extraction manageable, we randomly sampled 10% of each subset of users for the following timelineFootnote 3 extraction. The number of users and the tweets extracted from their corresponding timelines is presented in Table 3. The corresponding timelines have been extracted for the time period from November 25th, 2021 to May 25th, 2022 (see also “Baseline construction”). It is worth noting that not all users were still active on Twitter during the timeline extraction phase (i.e. some users have been banned or suspended their account in the meantime).

In Table 3, we report on the targeted number of users in each subsample as well as the actual number of timelines that could be obtained from Twitter. In total, we collected 19,500,218 timeline-related tweets. To ensure that our findings are not subject to the potential influence of social bot accounts, we used Botometer [52] to detect bots in our pool of users. We classified those accounts as bots, whose Botometer score was at least 0.85. After the removal of potential bot accounts and their corresponding tweets, the data-set counted 16,224,399 tweets that went into our data analysis.

Baseline Construction

To detect effects of the exposure to war-related messages of high anxiety and high positivity, we considered a period spanning over the 3 months before the start of the war (25th November 2021 to 23th February 2022) as our baseline period. Subsequently, we compared the indicators (anxiety and positivity levels, retweeting and tweeting activity) with those during the first month of the war (exposure period) (24th February to 25th March 2022), the second month of the war (26th March to 25th April), and the third month of the war (26th April to 25th May) (see also Fig. 2).

To analyze the adoption of the emotional tone that Twitter users were exposed to, we first made sure that highly active users do not disproportionally influence our results. We thus averaged anxiety and positivity scores per user on a daily basis. Since we are interested in a collective expression of emotions, we then computed a mean weekday score for all users for each emotion. This allowed us to address weekly oscillations. Finally, to make the results comparable among user subgroups (anxiety, positivity, and mixed exposure), we log-transformed the anxiety and positivity values. The corresponding procedure can be summarized as follows: \(log(\mu (\mu (E_{ud})_{wd})\), with E representing the emotion being observed, \(u \in \{user_1, user_2,..., user_n\}\), \(d \in \{day_1, day_2,..., day_n\}\), and \(wd \in \{Monday, Tuesday,..., Sunday\}\). This procedure was conducted for all four temporal segments (see Fig. 2) and allowed us to compare the emotional tone before the war, as well as gradually over the first 3 months of the war.

Results

Adoption of the Emotional Tone of the Tweet the Users Were Exposed To

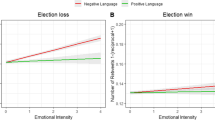

We found that the temporal evolution of emotion intensities highly differs, depending on the emotions a user was exposed to during the first month of the war. We observe a high surge of anxiety during the first month of the war in users who are multi-exposed to messages that convey anxiety (see Figs. 3, 4).

However, there are noticeable differences among those exposed to anxiety and those exposed to positive messages. For one, in the second month of the war, anxiety-levels in the group of anxiety-exposed users are close to the baseline while the anxiety levels increase above the baseline during the third month of the war. In contrast, the group of positivity-exposed users exhibit a comparatively lower level of anxiety in the post-exposure months. However, both groups of users show lower positivity levels in relation to their baseline. Positivity increases slowly throughout the second and third month of the war (the post-exposure phase). However, only for those exposed to positivity does the level of positivity climb back to its baseline level.

When analyzing the mixed-exposure users, it seems that positivity has a diminishing influence on the levels of anxiety. This group of users experiences only a slight increase in anxiety during the first month of the war, while the anxiety levels remain below the baseline in the post-exposure months. On the other hand, the positivity levels in the group of mixed-exposure users remain well beyond their baseline level and are are comparable to those who have been multi-exposed to anxiety.

We used Welch’s two sample t-test to examine whether the differences among the groups of users in the months following the exposure are statistically significant. For this purpose, we define the following null hypothesis:

- H\(_0\)::

-

There are no statistically significant differences in the expression of anxiety among the groups of users during the second and third month of the war.

The results of the t-test (see Table 4) show significant differences among those exposed to anxiety (including the mixed-exposure users) and those who are predominantly exposed to messages conveying high levels of positivity. These differences are significant in both post-exposure periods (second and third month of the war), whereby those exposed to anxiety (including the group of mixed-exposure users) consistently display higher levels of anxiety.

We repeated the same procedure to examine the expression of positive emotions. The corresponding null hypothesis reads:

- H\(_0\)::

-

There are no statistically significant differences in the expression of positive emotions among the groups of users during the second and third month of the war.

The results of the t-test (see Table 4) show a higher intensity of positive emotions in the group of positivity-exposed users as compared to those exposed to anxiety (including the group of mixed-exposure users). These differences are statistically significant in both post-exposure periods (second and third month of the war).

Amplification of the Emotional Tone Through Multiple Exposures

We conducted a two-sample Welch’s t-test to find statistically significant results in terms of pre-war as well as war-time anxiety and positivity levels. For this purpose, we define the following null hypothesis:

- H\(_0\)::

-

There is no difference in the intensity of an emotion in the pre-war phase and the second and third months of the war.

The results of the respective t-test did not show any evidence for the amplification of the emotional tone in users being exposed to anxiety or positivity during the post-exposure periods (second and third month of the war). The only statistically significant increase in anxiety was found for the anxiety-exposed users during the first month of the war as compared to the baseline level of anxiety. This increased level of anxiety, however, did not persist in the second and third month of the war.

User Activity Level After Exposure

Finally, we examined whether the activity levels of users exposed to anxiety and positivity have changed in the second and third month of the war. The results are summarized in Table 5.

In contrast to our initial hypothesis, the exposure to positive messages is associated with an increase in tweet frequency (here we refer to the frequency of posting original messages) and retweeting activity as compared to the baseline. This is especially evident for the mixed-exposure users where the baseline tweeting level of 9.69 increased to 11.8 and 10.7 in the second and third month of the war, while their retweet activity increased from 107.0 in the pre-war phase to 143.0 and 125.0, respectively.

Those exposed to positive messages also displayed a higher retweeting rate and a rather short-lived increase in their frequency of tweeting original content (only during the second month of the war) (see Table 5).

Exposure to anxiety was neither associated with an increase in tweeting nor retweeting frequency in the second and third month of the war. In contrast, the tweeting frequency for original content slightly but consistently dropped below the baseline, while the retweeting activity was either at the baseline level or below.

Discussion

Our study indicates that anxiety plays a considerable role regarding the mid-term mood of Twitter users exposed to reports about the 2022 war in Ukraine. We showed that in the presence of anxiety-filled messages, the time to reach the pre-war baseline levels of positivity is comparably longer than for those predominantly exposed to positive messages. This might point to the mid- and long-term effects of high arousal negative emotions (such as anxiety) on the well-being of Twitter users. Though we make no assumptions about the causality of our findings, it is reasonable to assume that a multi-exposure to high levels of anxiety in times of war sets the negative tone in users exposed to it. High initial anxiety should, however, come as no surprise. As pointed out in related studies, anxiety is frequently associated with events when death is imminent or expected (see, e.g., [1, 33, 43]).

Our analysis indicates that the levels of anxiety were not intense or long-lasting in the months that followed for neither group of users. However, the low levels of positivity pointed to the potential disruptive mid-term effects of anxiety-filled messages. Our analysis did not only show that the exposure to positive messages is associated with lower levels of anxiety in the following months but also that this group of users is able to approach their pre-war baseline level of positivity already in the second month of the war.

Along these lines, prior research has pointed to the undoing effects of positivity during acts of violence. One of such studies presented in [53] showed that positive emotions have a direct, significant, and negative effect on (death) anxiety. Furthermore, [17] demonstrated that positive emotions help people exercise resilience against depression, while reducing their attention to negative emotions (see also [30]). As such, they do not only serve as distractions but play a significant role in one’s coping with stress and anxiety. In fact, [17] argues that positive emotions are crucial ingredients in superior coping and play a positive role in one’s resilience [37]. Moreover, prior studies have shown that positive emotions do not only help people return faster to their baseline levels of cardiovascular activity, but also broaden their modes of thinking (e.g., resulting in higher creativity [24] or openness for new information [14]).

Finally, it is worthwhile mentioning that the war studied in this paper is still ongoing at the time of writing and the final effects of anxiety- and positivity-filled messages will only be visible months after the war had ended.

Limitations

Although we used Twitter’s public API with academic access level, the sheer volume of tweets generated in our extraction period demanded that our data extraction spanned over multiple days to fetch the tweets that have been generated in a single day of the war. Due to this time lag, we cannot exclude the possibility that some tweets were removed from Twitter by their authors or even Twitter itself before we were able to extract them (e.g., due to misinformation or violent language).

Moreover, in order to detect the presence and the intensity of anxiety and positive emotions in tweets, we used the LIWC tool. We cannot rule out the possibility that LIWC misclassified some tweets. As the automated detection of emotions in written texts, especially short and sparse texts such as tweets, is a difficult task, there might be sarcastic tweets in our data-set that we could not automatically detect and that might impact our results.

We sampled the users exposed to anxiety and positivity by first identifying tweets associated to high emotion scores (97\(^{th}\) percentile, i.e. the top three percent). From this set of tweets we then identified users with high exposure scores (98\(^{th}\) percentile, i.e. the top two percent). In this procedure, we deliberately did not remove any outliers because they can be considered as legitimate observations in our data-set and thus potentially bring interesting findings. However, we removed bot accounts to eliminate a potential bias that might have resulted from bot activity. While we manually inspected some of the accounts marked as bots by Botometer, we still cannot be sure if we removed all bots nor can we rule out the possibility that Botometer misclassified some regular accounts as bots.

Finally, as mentioned above, we observed the effects of anxiety in the early stages of the war. Our results are thus subject to the choice of the time-window selected for this study. An analysis of a longer time-window could bring forth additional insights into the effect of the exposure to anxiety on Twitter users. Finally, the full effects of the observed emotions on social media users will only be visible after the war has ended.

Conclusion

In this paper, we analyzed the effects of multi-exposure to messages conveying high levels of anxiety or positivity related to the 2022 war in Ukraine. To this end, we extracted and analyzed a data-set including over 16 million Twitter messages. Our data-set spans over a six-month period and allows us to derive pre-war baseline anxiety and positivity levels (3 months before the start of the war). We subsequently compared the anxiety and positivity levels within the first 3 months of the war to the baseline.

Our analysis indicates that anxiety is high during the first month of the war (the initial exposure phase) and is especially intense for those users who are multi-exposed to anxiety conveying messages (during the second and third months of the war). The same group of users exhibited a weaker expression of positivity which constantly remained below their baseline level. This is in contrast to users who initially have been exposed to a high level of positive messages.

Moreover, the increased levels of anxiety persisted during the first month of the war and re-emerged above the baseline level during the third month of the war. In contrast, positivity-exposed users consistently showed a higher intensity of positivity, compared to those initially exposed to anxiety, and did not cross their baseline level of anxiety in the post-exposure phase (second and third month of the war).

We also demonstrated that the initial exposure to positivity was associated with increased tweeting and retweeting activities, as compared to anxiety-exposed users who showed a decrease in their Twitter activity.

This study opens up further questions that we plan to explore in our future work. Thus far, we examined the effects of anxiety on human behavior as opposed to positivity. The question still remains whether high-arousal negative emotions would have similar effects on social media users when compared to low-arousal negative emotions such as sadness. Moreover, it is worthwhile noting that although we identified the undoing effects associated with the exposure to positive messages, we still cannot draw conclusions regarding general effects of positivity during other fear-driven events. Finally, this paper especially focused on users who have been highly exposed to emotional messages. It would be interesting to investigate whether the level of exposure has an impact on user behavior on Twitter. We plan to further investigate these questions in our future work.

Data availability

Research data is available upon request.

Notes

According to Russell’s circumplex model of emotions, affective valence describes emotions as neutral (e.g., surprise), positive (e.g., joy) or negative (e.g., anger) [42].

The ’referenced type’ attribute of Twitter messages includes values such as ’retweeted’ or ’quoted’.

On Twitter, a user timeline includes original tweets, retweets, replies, and quoted tweets posted by the respective user.

References

Abdel-Khalek AM. A general factor of death distress in seven clinical and non-clinical groups. Death Stud. 2004;28(9):889–98.

Bastian B, Jolanda J, Ferris L. Pain as social glue: Shared pain increases cooperation. Psychol Sci. 2014;25(11):2079–85.

Baumeister RF, Bratslavsky E, Finkenauer C, et al. Bad is stronger than good. Rev Gen Psychol. 2001;5(4):323–70.

Burnap P, Williams M, Sloan L. Tweeting the terror: modelling the social media reaction to the Woolwich terrorist attack. Soc Netw Anal Min. 2014;4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-014-0206-4.

Cheung-Blunden V, Blunden B. The emotional construal of war: Anger, fear, and other negative emotions. Peace Conflict: J Peace Psychol. 2008;14(2):123–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10781910802017289.

Chmiel A, Sobkowicz P, Sienkiewicz J, et al. Negative emotions boost user activity at bbc forum. Physica A. 2011;390(16):2936–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2011.03.040.

Chua A, Chen X. Rumor retransmission on Twitter: message characteristics, user characteristics and retransmission outcomes. J Digit Inf Manag. 2020;18(1):21–32.

Chuai Y, Zhao J. Anger can make fake news viral online. Front Phys. 2022;10(970):174.

Codispoti M, Mazzetti M, Bradley MM. Unmasking emotion: exposure duration and emotional engagement. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(4):731–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00804.x.

Coombs WT. Information and compassion in crisis responses: a test of their effects. J Public Relat Res. 1999;11(2):125–42. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1102_02.

Coviello L, Sohn Y, Kramer ADI, et al. Detecting emotional contagion in massive social networks. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090315.

Derks D, Fischer AH, Bos AE. The role of emotion in computer-mediated communication: A review. Comput Hum Behav. 2008;24(3):766–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.04.004, instructional Support for Enhancing Students’ Information Problem Solving Ability.

Durkheim E. The elementary forms of religious life. In: Social Theory Re-Wired. Routledge, 2016; p 52–67.

Estrada CA, Isen AM, Young MJ. Positive affect facilitates integration of information and decreases anchoring in reasoning among physicians. Org Behav Hum Decis Process. 1997;72(1):117–35.

Feigenson NR. Emotions, risk perceptions and blaming in 9/11 cases. Brooklyn Law Rev. 2003;68(4):959–1001.

Folkman S, Moskowitz J. Positive affect and the other side of coping. Am Psychol. 2000;55(6):647–54. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.55.6.647. (PMID: 10892207).

Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, et al. What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;84(2):365–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365.

Garcia D, Rime B. Collective emotions and social resilience in the digital traces after a terrorist attack. Psychol Sci. 2019;30(4):617–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619831964.

Garg P, Garg H, Ranga V. Sentiment analysis of the Uri terror attack using Twitter. In: 2017 International conference on computing, communication and automation (ICCCA), IEEE, 2017; pp 17–20.

Gleason B. #occupy wall street: Exploring informal learning about a social movement on twitter. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(7):966–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479372.

Harb G, Ebeling R, Becker K. Exploring deep learning for the analysis of emotional reactions to terrorist events on twitter. Journal of Information and Data Management. 2019;10(2):97–115. https://doi.org/10.5753/jidm.2019.2039.

Hobfoll SE, Lomranz J, Eyal N, et al. Pulse of a nation: Depressive mood reactions of Israelis to the Israel-Lebanon war. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56(6):1002–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.56.6.1002.

Hollis V, Konrad A, Whittaker S. Change of heart: Emotion tracking to promote behavior change. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, CHI ’15, 2015; p 2643-2652, https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702196.

Isen AM, Daubman KA, Nowicki GP. Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(6):1122.

Jones NM, Silver RC. This is not a drill: Anxiety on Twitter following the 2018 Hawaii false missile alert. Am Psychol. 2020;5(5):683–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000495.

Jones NM, Wojcik SP, Sweeting J, et al. Tweeting negative emotion: An investigation of Twitter data in the aftermath of violence on college campuses. Psychol Methods. 2016;21(4):526–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000099.

Kanavos A, Perikos I, Vikatos P, et al. Modeling retweet diffusion using emotional content. In: IFIP International conference on artificial intelligence applications and innovations, Springer, 2014; pp 101–110

Knudsen H, Roman P, Johnson J, et al. A changed America? The effects of september 11th on depressive symptoms and alcohol consumption. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(3):260–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650504600304.

Kramer ADI, Guillory JE, Hancock JT. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(24):8788–90. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320040111.

Kušen E, Strembeck M, Conti M. Emotional Valence Shifts and User Behavior on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, 2019; pp 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02592-2_4.

Kušen E, Strembeck M. An Analysis of Emotion-Exchange Motifs in Multiplex Networks During Emergency Events. Applied Network Science. 2019;4(8):1–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41109-019-0115-6.

Kušen E, Strembeck M. Building blocks of communication networks in times of crises: Emotion-exchange motifs. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;123(106):883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106883.

Kušen E, Strembeck M. Emotional Communication During Crisis Events: Mining Structural OSN Patterns. IEEE Internet Comput. 2021;25(02):58–65. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2020.3033205.

Kušen. E, Strembeck. M. Dynamics of personal responses to terror attacks: A temporal network analysis perspective. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk - COMPLEXIS,, INSTICC. SciTePress, 2022; pp 36–46, https://doi.org/10.5220/0011078100003197.

Leung J, Chung J, Tisdale C, et al. Anxiety and panic buying behaviour during covid-19 pandemic–a qualitative analysis of toilet paper hoarding contents on Twitter. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18, 2021; (1127). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031127.

Lu D, Hong D. Emotional contagion: Research on the influencing factors of social media users’ negative emotional communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.931835.

Milioni M, Alessandri G, Eisenberg N, et al. The role of positivity as predictor of ego-resiliency from adolescence to young adulthood. Personality Individ Differ. 2016;101:306–11.

Park C. Applying “negativity bias’’ to Twitter: Negative news on Twitter, emotions, and political learning. Journal of Information Technology & Politics. 2015;12(4):342–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2015.1100225.

Pennebaker JW, Harber KD. A social stage model of collective coping: The loma prieta earthquake and the persian gulf war. J Soc Issues. 1993;49(4):125–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1993.tb01184.x.

Páez D, Basabe N, Ubillos S, et al. Social sharing, participation in demonstrations, emotional climate, and coping with collective violence after the March 11th Madrid bombings. J Soc Issues. 2007;63(2):323–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00511.x.

Rimé B, Páez D, Basabe N, et al. Social sharing of emotion, post-traumatic growth, : Follow-up of spanish citizen’s response to the collective trauma of march 11th terrorist attacks in madrid. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2010;40(6):1029–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.700.

Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(6):1161–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0077714.

Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. A terror management theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of self-esteem and cultural worldviews. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1991;24:93–159.

Stearns P. Jealousy. In: Ramachandran V (ed) Encyclopedia of Human Behavior (Second Edition), second edition edn. Academic Press, San Diego, 2012; p 479–486, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375000-6.00213-5.

Stevens HR, Oh YJ, Taylor LD. Desensitization to fear-inducing covid-19 health news on twitter: Observational study. JMIR Infodemiology 1(1):e26,876, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2196/26876.

Tonkin E, Pfeiffer HD, Tourte G. Twitter, information sharing and the london riots? Bull Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2012;38(2):49–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/bult.2012.1720380212.

Wang Y, Han R, Lehman T. Do Twitter users change their behavior after exposure to misinformation? An in-depth analysis. Social Network Analysis and Mining 12(167), 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-022-00992-8.

Watkins H, Bastian B. Lest we forget: The effect of war commemorations on regret, positive moral emotions, and support for war. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2019;10(8):1084–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619829067.

Xiong X, Zhou G, Huang Y. Dynamic evolution of collective emotions in social networks: a case study of Sina Weibo. Sci China Inf Sci. 2013;56:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11432-013-4892-8.

Xiong Y, Cho M, Boatwright B. Hashtag activism and message frames among social movement organizations: Semantic network analysis and thematic analysis of twitter during the #metoo movement. Public Relations Review. 2019;45(1):10–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.014.

Xu QA, Chang V, Jayne C. A systematic review of social media-based sentiment analysis: Emerging trends and challenges. Decision Analytics Journal. 2022;3(100):073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dajour.2022.100073.

Yang K, Ferrara E, Menczer F. Botometer 101: social bot practicum for computational social scientists. J Comput Soc Sc. 2022;5:1511–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42001-022-00177-5.

Yildirim M, Guler A. Positivity explains how covid-19 perceived risk increases death distress and reduces happiness. Personality Individ Differ. 2021;168(110):347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110347.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the topical collection “Emerging Technologies and Services for post-COViD-19” guest edited by Victor Chang, Gary Wills, Flavia Delicato and Mitra Arami.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kušen, E., Strembeck, M. The Effects of Multiple Exposure to Highly Emotional Social Media Content During the Early Stages of the 2022 War in Ukraine. SN COMPUT. SCI. 4, 663 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-02080-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-02080-w