Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the frequency of countries represented in the TOP20 long-distance elite runners ranking during 1997–2020, taking into account the countries’ Human Development Index (HDI), and to verify if the Matthew effect can be observed regarding countries’ representativeness in the raking alongside the years.

Methods

The sample comprised 1852 professional runner athletes, ranked in the Senior World TOP20 half-marathon (403 female and 487 male) and marathon (480 female and 482 male) races, between the years 1997–2020. Information about the countries’ HDI was included, and categorized as “low HDI”, “medium HDI”, “high HDI”, and “very-high HDI”. Athletes were categorized according to their ranking positions (1st–3rd; 4th–10th; > 10th), and the number of athletes per country/year was summed and categorized as “total number of athletes 1997–2000”; “total number of athletes 2001–2010”; and “total number of athletes 2011–2020”. The Chi-square test and Spearman correlation were used to verify potential associations and relationships between variables.

Results

Most of the athletes were from countries with medium HDI, followed by low HDI and very-high HDI. Chi-square test results showed significant differences among females (χ2 = 15.52; P = 0.017) and males (χ2 = 9.03; P = 0.014), in half-marathon and marathon, respectively. No significant association was verified between HDI and the total number of athletes, but the association was found for the number of athletes alongside the years (1997–2000 to 2001–2010: r = 0.60; P < 0.001; 2001–2010 to –2011–2020: r = 0.29; P < 0.001).

Conclusion

Most of the athletes were from countries with medium HDI, followed by those with low HDI and very-high HDI. The Matthew effect was observed, but a generalization of the results should not be done.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Human Development Index (HDI) is an international index used to provide additional information beyond the economic information provided by the Gross Domestic Product [37]. The HDI is defined as a general measure of human development in a given population, determined by socioeconomic status, life expectancy (i.e., health), per capita income (i.e., income), and formal education access (i.e., education) [37]. Similarly, HDI, developed by the United Nations Development Programme (UNEP), has been cited as one of the most powerful variables that play a relevant role, along with cultural factors, in promoting a favourable environment for sporting development [10].

From an ecological perspective, the interplay of subject-environment has been highlighted as an essential key to human development through several domains (e.g., cognitive, behavioural, social, motor) [8, 35]. Since athlete development is a non-linear process [19], different variables act together for its expressions, such as personal characteristics, motivational aspects, social/economic facilities, and cultural factors. So, support from different levels is required [19], meaning that the role of individual factors (i.e., anthropometric, physiological, technical-tactical, psychological) [20, 39], economic characteristics and training structure [13], and context-specific characteristics are relevant to sports participation and performance [3, 11, 28, 32].

Studying Brazilian swimming athletes, Gomes-Sentone et al. [16] reported that HDI, income, and education level were important social indicators for sports performance, and similar results were reported by Costa et al. [10] among soccer players. On the other hand, Santos et al. [30], studying junior, elite professionals, and masters athletes presented in the Athletics World Rankings (i.e., 100 m and 10,000 m running distances), found that countries with very high HDI were the most represented in the 100 m ranking, while countries with moderate/low HDI were the most represented in the 10,000 m ranking. Previous studies highlighted that environmental characteristics are also important predictors of sports participation [5].

In summary, the published studies highlighted those environmental characteristics were relevant in both the development and maintenance of athletic performance [11, 18, 25]. Thus, considering the context-specific characteristics between countries, it is possible to postulate that these differences can be associated with between-countries performance differences, which can lead one country to be more competitive than the others, achieving higher international performance and recognition [6, 33]. Furthermore, this scenario can lead these countries to receive more financial sports investments through their government and/or stakeholders/sponsors, allowing them to increase their visibility and success at the international level, due to better conditions for sports development and support for elite athletes.

This fact may illustrate the concept of the “Matthew effect” [1], which highlights that initial advantage tends to beget further advantage and disadvantage further disadvantage. Over time, these differences tend to create widening gaps between those who have more and those who have less [1]. The “Matthew effect” has been studied in a wide variety of contexts and institutional settings, such as sociology, education, biology, and economics [14, 22, 27]. In the context of sport, it is possible to observe this occurrence in the Brazilian setting, where differences between its regions tend to favour those with more favourable socioeconomic indicators [10, 16, 29]. These regions, which receive higher amounts of economic investments [26], tend to invest more in sports and talent development programs in a higher number of sports clubs, and competition events, which contributes to these regions, usually concentrating the highest number of high-elite athletes at a national level [34]. Furthermore, athletes identified as talented tend to move to these regions or are recruited by development programs and sports clubs from these regions, with the purpose to have success in the practice/modality [2].

For example, in endurance running, it was reported that socioeconomic variables (i.e., sports investment and gross domestic product) and competition venue were associated with countries’ likelihood of having athletes in the top 10 rankings, in the European continent [33]. Furthermore, in the Brazilian context, a relationship between population size and the State’s Gross Domestic Product with the number of athletes in the national ranking was observed [33]. Moreover, at an international level, information about the success of the African endurance runners has been extensively studied [17], but information regarding the relationship between countries’ HDI and the success in this modality is still not conclusive.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate the frequency of countries represented in the TOP20 long-distance elite runner rankings from 1997 to 2020 whilst taking into account countries' HDI. We also aimed to verify if the “Matthew effect” can be observed regarding countries' representativeness in the ranking over 23 years, i.e., if having a high number of athletes in the ranking in the first years is associated with a high number of athletes in the following years. We hypothesized that the number of athletes in the first decade would be associated with the number of athletes in the last decade and that countries' HDI would be negatively associated with the number of athletes each country has in the ranking of the modality.

Methods

Study design and data source

The study used a cross-sectional design. All data were collected in November 2020 from the official results section of the Tilastopaja website (www.tilastopaja.eu/). All available results from the world's best half-marathon and marathon marks in official outdoor events, between 1997 and 2020, were compiled for both male and female sexes. Available information included: the athlete’s name, date of birth, sex, race time, citizenship, date of the competition, and venue. Athletes’ age was computed using the date of birth and the date of the competition.

For the present study, the sample included 1852 professional runners (883 female and 969 male), aged 18–41 years, who were ranked in the Senior World TOP20 half-marathon (403 female and 487 male) and marathon races (480 female and 482 male), for the years 1997–2020. To categorize athletes according to their performance, they were split, based on their ranking position, into three groups (“1st–3rd”; “4th–10th”; “ > 10th”), based on previous studies [24].

HDI data source

Further, information regarding the countries HDI was collected from the HDI Global 2014 (https://www.br.undp.org/content/brazil/pt/home/idh0/rankings/idh-global.html). Based on the United Nations Development Program (36), HDI was categorized as “low” (< 0.550), “medium” (≥ 0.550 and ≤ 0.699), “high” (≥ 0.700 and ≤ 0.799), and “very high” (≥ 0.800).

Determination of the “Matthew effect”

To identify the existence of the “Matthew effect”, information about the number of athletes ranked in the TOP20 per country was considered. Previous studies have shown a decrease in participation and presence in the ranking for European athletes, in comparison to African athletes in the last years [24]. However, taking into account the temporal interval available to be used in the present study and the number of athletes by country, we decided to cluster it into three different time intervals (“1997–2000”; “2001–2010”; 2011–2020”).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean (standard deviation), and frequencies (%). The normality was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi-square test, followed by the Tukey test for multiple pairwise comparisons was performed in WinPepi to verify the association between athletes ranking position (1st–3rd; 4th–10th; > 10th) and countries’ HDI classification (low HDI; medium HDI; high HDI; very-high HDI), considering race distance for both sexes. Spearman correlation (r) was used to estimate the relationship between countries’ HDI and the total number of athletes per country across the year intervals and also consider the full range of years. The magnitude of the correlation was determined by the scale proposed by Batterham and Hopkins [4] as follows: r < 0.1, trivial; r = 0.1– < 0.3, small; r = 0.3– < 0.5, moderate; r = 0.5– < 0.7, strong; r = 0.7– < 0.9, very strong; r = 0.9 to < 1.0 almost perfect; and r = 1.0, perfect. Bootstrap results were performed based on 1000 bootstrap samples. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26®, was used, adopting a significance level of 95%.

Results

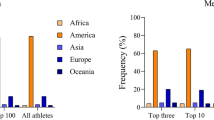

The athletes’ mean age was 27.5 (4.5) and 25.6 (3.6) years for women and men half-marathoners, and 28.4 (4.1) and 28.0 (4.0) years for marathoners of both sexes (women and men, respectively). The sample distribution, according to HDI, was: 50.1% (n = 927) from medium HDI countries, 24.8% (n = 459) from low HDI countries, 22.2% (n = 412) from very-high HDI, and 2.9% (n = 54) from high HDI countries. Figure 1 presents the athletes’ distribution per race distance, according to countries HDI. The majority of athletes were from countries with medium HDI, except female marathoners, where most of them were from very-high HDI (36%) and low HDI (30.4%).

Table 1 presents the chi-square results. For the “1st–3rd” category, in both distances and for both sexes, the highest frequency was observed for countries classified as medium HDI, and this frequency was significantly higher compared to other countries classification. In general, countries with medium HDI were higher represented in the ranking, except for groups “4th–10th” and “ > 10th” among female marathoners, where the highest representativeness was observed for countries with a very high HDI.

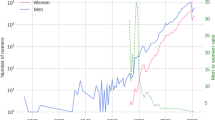

Table 2 and Fig. 2 show the Spearman correlation results for the association between countries’ HDI and the total number of athletes in the ranking across the years (intervals). Non-significant associations were observed between HDI and the total number of athletes, regardless of the year interval. A positive, moderate and significant association was found between the number of athletes in 1997–2000 and the number of athletes in 2001–2010 (r = 0.600; P < 0.001), as well as a trivial correlation between the number of athletes in 2001–2010 and the number of athletes in 2011–2020 (r = 0.29; P < 0.001).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the frequency of countries represented in the TOP20 long-distance elite runners ranking during 1997–2020, taking into account countries' HDI, and to verify if the “Matthew effect” can be observed regarding countries’ representativeness in the ranking alongside the years. The main findings reveal that most of the endurance athletes were from countries with medium and/or low HDI in the last 20 years; (ii) most female marathoners were from countries with a very high HDI, followed by a low HDI, and (iii) a noncorrelation between HDI and number of athletes were showed, but a positive and significant association was verified for the number of athletes in different years.

Although most of the female athletes came from Kenya and Ethiopia, countries such as Japan, Romania, China, Russia, Germany, Great Britain, and Italy represent, together, approximately 28% of the ranking, which can explain the results found. It seems to have a consensus, in the available literature, regarding the role of economic and social factors in sports participation and high-level sports performance [7, 25]. At an international level, a previous study highlighted the role of the States in the Olympic success, of which 50% of this success can be associated with countries' HDI, population size, and political regime [6]. Similar results were observed by Thuany et al. [33], studying Brazilian elite endurance athletes, where the authors reported that population size and GDP were related to states' representativeness (determined by the number of athletes) in the national ranking of the modality. At the European level, economic proxy (i.e., sports investment) and place of competition (i.e., housing running events) seem to increase the chances of a runner being ranked among the 10 best athletes in endurance running [33].

A previous study, conducted by Santos et al. [30], identified a positive correlation between countries' HDI and the number of athletes in the IAAF (World Athletic) ranking from 2006 to 2016; however, in the present study, no significant association between HDI and the number of athletes in the ranking was observed. Disagreement between these results can be related to differences in sample characteristics (i.e., sex and competitive level) and years considered (2006–2016 vs. 1997–2020 in the present study). In addition, results from the present study can be related to the fact that most of the athletes in the TOP20 ranking, during the last 20 years, are from African countries, especially Kenya (47%, if considering the whole temporal range, and 50.8% if considering the last 10 years) and Ethiopia (22.4%, if considering the whole temporal range, and 38.2% when considering the last 10 years). Both countries do not have a large population size, nor even a high HDI, since they are ranked in the 143rd and 173rd positions, respectively (http://hdr.undp.org/).

However, available data indicated that in 2015, about 2.98% of the Kenyan adult population were unemployed, and about 37.1% of the population lived below the poverty line (https://data.worldbank.org/country/kenya). However, a different economic scenario was described by Onywera et al. [23], whose results showed that about 40% of the Kenyan population were unemployed, and at least 50% lived below the poverty line. These socioeconomic data do not reflect the country’s representativeness at an international level in endurance running sports, since most of the best athletes come from these countries classified as having low HDI, such as Kenya and Ethiopia [21]. Given the significant poverty conditions experienced by Kenyans, sports participation could be motivated by the possibility of economic empowerment [23]. However, another potential fact is that running is a relevant aspect of Kenyan life, being part of the country’s sporting culture [15].

These results reinforce the idea that sports performance is “country-specific” [12], and although Kenya is not a wealthy country, it is still one of the nations with the best endurance-running athletes. The hegemony of a country in a given sport is not a recent phenomenon (e.g., Sprinters—Jamaica; Soccer—Brazil; Basketball—EUA; Hockey—Canada), and the country’s success is associated with cultural and environmental characteristics (e.g., athletes development programs, number of competitions, number of clubs, sports investment), or even with the athletes perspective of social ascension trough the sport [23].

The “Matthew effect” was indirectly tested, and the study hypothesis was supported, showing a direct relationship between the numbers of athletes, across the year’s intervals. The results demonstrated that a high number of athletes in the ranking in the first decade was positively associated with the number of athletes in the second and third decades. Since 1968 (Mexico City Olympic Games), Kenya and Ethiopia have dominated the long-distance running events in Track and Field [21, 38]. The hegemony of African athletes among the best runners worldwide was associated with a plethora of factors, especially the genetic characteristics, environmental factors (i.e., altitude), morphological and physiological indicators [9, 23, 31], in addition to the motivational characteristics. Since participation in sport can potentially lead to better living conditions for athletes (in part due to possible economic empowerment, better access to facilities and care), this fact can contribute to a higher number of youth becoming interested in track and field as a potential career in these countries [15].

Increasing the number of potential athletes to achieve the elite status and, as a consequence, keeping these countries in the highest position in the ranking of the modality, i.e., the higher the number of athletes internationally ranked, the higher the sport practice increases in the country, and the higher the chances of the country keep its position in the ranking. It is interesting to note that, in this case, the “Matthew effect” is observed not because of higher economic conditions in a country, but instead having athletes well-ranked can be a positive stimulus for youth to take part in the modality, keeping and/or maintain the country position in the international athletic success.

There were some limitations in the current study. First, we considered only the TOP20 athletes around the world, which indicated that differences could be identified if other athlete’s categories were considered, or even through the use of a different ranking classification and/or distance (i.e., middle-running) and temporal range (i.e., before 1997). Second, to identify the “Matthew effect”, we only considered the last 20 years, and could be of relevance to investigate a longer period. Thirdly, the lack of time between the HDI (2014) and the sum of athletes in different years could be associated with an absence of significant association.

Conclusion

Half of the elite endurance athletes ranked in the TOP20 between 1997 and 2020, are from countries with a medium HDI, followed by a low HDI and a very high HDI. Instead of any significant association being observed between countries' HDI and athletes ranking positions, an illustration of the Matthew effect was observed, since a positive and significant relationship in the number of ranked athletes over the years was observed, where those countries with the highest number of athletes in the first decade were most represented in the subsequent decade. However, these results do not allow the generalization, and future studies should consider investigating a longer time interval, comprising years before 1997, and the relationship with other socioeconomic factors.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acar S. Matthew, Pygmalion, and Founder Effects. In: Mark Runco, Pritzker S, editors. Encyclopedia of Creativity. 2nd ed. New York: Academic Press; 2011. p. 1384.

Agergaard S, Ryba TV. Migration and Career Transitions in professional sports: transnational Athletic careers in a psychological and sociological perspective. Sociol Sport J. 2014;31:228–47.

Baker J, Schorer J, Cobley S, Schimmer G, Wattie N. Circumstantial development and athletic excellence: the role of date of birth and birthplace. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;9(6):329–39.

Batterham A, Hopkins W. Making meaningful inferences about magnitudes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2006;1(1):50–7.

Beenackers M, Kamphuis C, Burdorf A, Mackenbach J, Van Lenthe F. Sports participation, perceived neighborhood safety, and individual cognitions: how do they interact? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(76):1–76.

Bohme MTS, Bastos FC. Esporte de alto rendimento: fatores críticos de sucesso—gestão—identificação de talentos. 1st ed. São Paulo: Phorte; 2016. p. 360.

Breuer C, Hallmann K, Wicker P. Determinants of sport participation in different sports. Manag. 2013;16(4):269–86.

Bronfenbrenner U. Bioecologia do desenvolvimento humano: tornando os seres humanos mais humanos. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2011. p. 310.

Casado A, Hanley B, Ruiz-Perez LM. Deliberate practice in training differentiates the best Kenyan and Spanish long-distance runners. Eur J Sport Sci. 2019;20(7):1–9.

Costa IT, Cardoso FSL, Garganta J. O Índice de Desenvolvimento Humano e a data de nascimento podem condicionar a ascensão de jogadores de Futebol ao alto nível de rendimento? Motriz. 2013;19(1):34–45.

Cote J, Macdonald DJ, Baker J, Abernethy B. When, “where” is more important than “when”: birthplace and birthdate effects on the achievement of sporting expertise. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(10):1065–73.

De Bosscher V, Truyens J. Comparing apples with oranges in international elite sport studies: Is it possible? In: Harald D, Soderman S, editors. Handbook of Research on Sport and Business. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar; 2013. p. 94–111.

De Bosscher V, Shibli S, Westerbeek H, van Bottenburg M. Successful elite sport policies: An international comparison of the Sports Policy factors Leading to International Sporting Success (SPLISS 20) in 15 nations. United Kingdom: Meyer & Meyer Sports Ltd.; 2015. p. 402.

Dzakpasu S, Joseph K, Kramer M, Allen A. The Matthew effect: infant mortality in Canada and internationally. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1):E5.

Epstein Genética D, do Esporte A. Como a Biologia Determina a Alta Performance Esportiva. 1st ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2014. p. 306.

Gomes-Sentone R, Lopez-Gi JF, Caetano CI, Cavichioll FR. Relationship between human development index and the sport results of Brazilian swimming athletes. JHSE. 2019;14(5):S2009–18.

Hamilton B. East African running dominance: what is behind it? Br J Sports Med. 2000;34(5):391–4.

Henriksen K, Stambulova N, Roessler KK. Successful talent development in track and field: considering the role of environment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010;20(Suppl 2):122–32.

Hristovski R, Balague N, Daskalovski B, Zivkovic V, LenceAleksovska-Velickovska NM. Linear and nonlinear complex systems approach tosports. Explanatory differences and applications. Pesh. 2012;1(1):25–31.

Joyner MJ, Coyle EF. Endurance exercise performance: the physiology of champions. J Physiol. 2008;586(1):35–44.

Larsen H, Sheel A. The Kenyan runners. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25(Suppl 4):110–8.

Morgan PL, Farkas G, Hibel J. Matthew effects for whom? Learn Disabil Q. 2008;31(4):187–98.

Onywera V, Scott RA, Boit MK, Pitsiladis YP. Demographic characteristics of elite Kenyan endurance runners. J Sports Sci. 2006;24(4):415–22.

Perez AJ, Marques A, Gomes KB. Performance analysis of both sex marathon runners ranked by IAAF. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum. 2018;20(2):182–9.

Rees T, Hardy L, Gullich A, Abernethy B, Cote J, Woodman T, Montgomery H, Laing S, Warr C. The great british medalists project: a review of current knowledge on the development of the world’s best sporting talent. Sports Med. 2016;46(8):1041–58.

Reverdito RS, Galatti LR, Lima LA, Nicolau PS, Scaglia AJ, Paes RR. The “Programa Segundo Tempo” in Brazilian municipalities: outcome indicators in macrosystem. J Phys Educ. 2016;27(1): e2754.

Rigney D. The Matthew effect: how advantage begets further advantage. New York: Columbia University Press; 2010.

Rossing NN, Stentoft D, Flattum A, Côté J, Karbing DS. Influence of population size, density, and proximity to talent clubs on the likelihood of becoming elite youth athlete. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(3):1304–13.

Santana ABN, Oliveira MA, Guerra RLF, Martins PA. Desigualdades socioeconômicas na percepção do ambiente de mobilidade ativa. Rev Bras Ativ Fís Saúde. 2015;20(3):297–308.

Santos PA, Sousa CV, Aguiar SS, Knechtle B, Nikolaidis PT, Sales MM, Rosa TDS, de Deus LA, Campbell CSG, de Sousa HG, Barbosa LD, Simões HG. Human development index and the frequency of nations in Athletics World Rankings. Sport Sci Health. 2019;15(2):393–8.

Tawa N, Louw Q. Biomechanical factors associated with running economy and performance of elite Kenyan distance runners: a systematic review. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22(1):1–10.

Teoldo I, Cardoso F. Talent map: how demographic rate, human development index and birthdate can be decisive for the identification and development of soccer players in Brazil. Sci Med Footb. 2021;5(4):293–300.

Thuany M, Pereira S, Hill L, Santos JC, Rosemann T, Knecthle B, Gomes TN. Where are the best european road runners and what are the country variables related to it? Sustainability. 2021;13(14):7781.

Tozetto AVB, Rosa RS, Mendes FG, Galatti LR, Souza ER, Collet C, Moura BMD, Silva WRD. Local de nascimento e data de nascimento de medalhistas olímpicos brasileiros. Rev Bras Cineantropom Desempenho Hum. 2017;19(3):364.

Vella SA, Cliff DP, Okely AD. Socio-ecological predictors of participation and dropout in organised sports during childhood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11(62):1.

United Nations Development Programme (PNUD). Human Development Report 2020: Reader's Guide: PNUD. 2020. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2020-readers-guide.

United Nations Development Programme (PNUD). O que é o IDH: PNUD. 2021. https://www.br.undp.org/content/brazil/pt/home/idh0/conceitos/o-que-e-o-idh.html.

Wilber R, Pitsiladis Y. Kenyan and Ethiopian distance runners: what makes them so good? Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2012;7(2):92–102.

Yan X, Papadimitriou I, Lidor R, Eynon N. Nature versus nurture in determining athletic ability. Med Sport Sci. 2016;61:15–28.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by MT and TNG. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MT and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Non-aplicable.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thuany, M., Knechtle, B., Kipchumba, K. et al. The Matthew Effect in Running: An Analysis of Elite Endurance Athletes Over 23 Years. J. of SCI. IN SPORT AND EXERCISE 5, 236–243 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-022-00176-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-022-00176-y