Abstract

High-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GS) play an essential role in the end-use quality of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). We developed a targeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method in parallel reaction monitoring (LC–MS/MS-PRM) to detect and differentiate wheat HMW-GS in German wheat cultivars with known (37 cultivars) and unknown (58 cultivars) composition. The newly developed method is suitable to unambiguously identify Ax1, Ax2*, Bx6, Bx14, Dx2, Dx5, Dy10, Dy12, as well as any absence of Ax, but cannot distinguish Bx7 and Bx17 and identify the variant of By due to high sequence identity to Dy and within By. The method is further suited to clearly conclude, if the sample is a mixture of at least two cultivars or consists of only one cultivar. In comparison to gel-based methods (SDS-PAGE), UV-detection after LC (RP-HPLC–UV) and MS of intact proteins (MALDI-TOF–MS), LC–MS/MS has a high resolution, is less biased by interpretation and provides more insights on molecular level. The used procedure can be applied to expand the LC–MS/MS-PRM method for more HMW-GS or even to other wheat proteins, e.g., low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (LMW-GS), in future. This study describes the first MS-based method on peptide level for the differentiation of wheat HMW-GS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The storage proteins of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) are divided into monomeric gliadins and polymeric glutenins. Both protein fractions form the gluten network through intermolecular disulfide bonds during baking and the presence and composition is therefore essential for baking quality (reviewed by Wieser et al. (2023)). The number of cysteines within the gluten proteins determines the ability to form disulfide bonds and both low- (LMW-GS) and high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GS) play a central role, as they contain a relatively high number of cysteines, which are available for disulfide bond formation. The latest gluten network model assumes that the HMW-GS build a backbone (head to tail bonds), to which LMW-GS are linearly bonded (Wieser et al. 2023). Based on this model, the content of HMW-GS is crucial for the size and rheological properties of the gluten network.

The HMW-GS are encoded at the Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1 loci and each locus consists of two genes which encode either the x-type (1Ax, 1Bx and 1Dx) with higher molecular weight or the y-type (1Ay, 1By and 1Dy) with lower molecular weight. The genes 1Bx, 1Dx and 1Dy are constantly expressed and at least three HMW-GS are present in wheat. The genes 1Ax and 1By are not always expressed and 1Ay is silenced in wheat leading to three, four or five HMW-GS in total (Payne et al. 1981). Payne et al. named the HMW-GS according to their electrophoretic mobility in 1981 (Payne et al. 1981) and this nomenclature is still used. Three variations (NULL, Ax1, Ax2*) are known for 1Ax, five variations for 1Bx (Bx6, Bx7, Bx13, Bx14 and Bx17), six variations for 1By (By8, By9, By15, By16, By18 and By19), four variations for 1Dx (Dx2, Dx3, Dx4 and Dx5) and two variations for 1Dy (Dy10 and Dy12) in European wheat. Some variations occur only in predestinated combinations (e.g., Dx2 + Dy12, Dx5 + Dy10, Bx14 + By15, Bx17 + By18). The frequency of different variations varies enormously (e.g., Dx2 + Dy12: 55% vs. Dx3 + Dy12: 2% and Bx7 + By9: 27% vs. Bx13 + By16: 0.5%) (Payne et al. 1981). Which HMW-GS composition is present also determines the baking quality. The combinations Dx5 + Dy10 or Bx7 + By8 are associated with better baking quality than the combinations Dx2 + Dy12 or Bx6 + By8 (Payne et al. 1987).

The classical method of choice for the identification of the HMW-GS composition in wheat is the sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), which is continuously used in the very recent studies (Dai et al. 2020; Geisslitz et al. 2020; Khalid and Hameed 2019). The technique has been further developed to lab-on-a-chip capillary electrophoresis that is suitable for large breeding programs (Shin et al. 2020). Alternatively, HMW-GS are analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (Lee et al. 2024; Ravel et al. 2020; Yao et al. 2022), which allows for the genetic analysis of wheat varieties to provide insights into the presence of different alleles, or by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (Dong et al. 2009; Jang et al. 2021; Lee et al. 2021), which allows the separation and analysis of proteins based on their hydrophobicity and also gives more quantitative insights compared to SDS-PAGE. Third, mass spectrometry (MS) like matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) enables the analysis of intact HMW-GS (Jang et al. 2021; Muccilli et al. 2011; Visioli et al. 2016), for a precise measurement of molecular weight of HMW-GS, which is more accurate than the estimation by SDS-PAGE. This method also enables the detection of post-translational modifications, offering deeper insights into the protein structure.

The rapid development of proteomics-based methods in the last years gives completely new insights into the proteome of plants and this technique has been applied to wheat accordingly to answer various questions (reviewed by e.g., Halder et al. (2022) and Lu et al. (2023)). Compared to the aforementioned methods, in which proteins are analyzed as intact proteins, proteins are digested to peptides, which are then analyzed by liquid-chromatography tandem MS (LC–MS/MS). This can be done either targeted (only specific peptides are measured by e.g., parallel reaction monitoring, PRM) or untargeted in e.g., data dependent acquisition (DDA) modus (the most abundant peptides are measured). In regard to wheat HMW-GS, these techniques have been applied to identify variations in the amino acid sequence of different Triticum species (Geisslitz et al. 2020; Muccilli et al. 2011), to correlate the baking quality with the HMW-GS combination (Aghagholizadeh et al. 2017) and to detect and quantitate HMW-GS (Martínez-Esteso et al. 2016; Schalk et al. 2018).

To ensure a reliable characterization of HMW-GS by LC–MS/MS a lot of prerequisites have to be fulfilled: The proteins have to be extracted from flour (Hurkman & Tanaka 2007), the most suitable enzyme for digestion has to be chosen (Colgrave et al. 2017) and a correct and complete database for protein identification is required (Vensel et al. 2011). Sample preparation including extraction and enzymatic digestion is already well established for HMW-GS, but the evaluation of the MS raw data and the correct identification is confronted with issues. This is because the HMW-GS are encoded on tightly linked genes, show a very high sequence identity, a high number of overlapping repetitive units and amino acid sequence regions that have no cleavage sites for enzymes. As consequence, evaluation software (here: MaxQuant) groups different variations of HMW-GS into one protein group and no differentiation is possible anymore (Geisslitz et al. 2020).

The aim of the study was the development of a targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM method to differentiate 14 HMW-GS in common wheat and to apply the new method to cultivars, of which the HMW-GS combination was not known according to literature and the German catalog for wheat description. To achieve this goal, one UniProtKB accession number had to be allocated for each HMW-GS and within these accessions, unique peptides for each HMW-GS had to be identified. Since the identification of HMW-GS by SDS-PAGE requires manual evaluation and the interpretation is often subjective and prone to errors due to insufficient separation or overlapping protein bands. This can lead to biased or inaccurate identification of HMW-GS. Thus, the new method should help to identify HMW-GS independently without any scope for interpretation.

Materials and methods

Wheat flour samples

In total, 37 common wheat samples with known HMW-GS composition and 58 ones with unknown composition that were grown and harvested in different years and locations were used. The kernels were milled with different mills and most of them were white flour, but there were wholemeal flours as well. The flours were stored for several weeks, but not longer than for three years in closed bottles at 22 °C. More information about the wheat flour samples can be found in Online Resource 1. The cultivars Dekan, Julius, Orcas, Oxal, Sonett and Tommi were used for in-gel digestion (Table 1).

Isolation of HMW-GS

The isolation of HMW-GS was performed as described elsewhere (Geisslitz et al. 2020). In brief, flour (100 mg) was extracted two times with a 50/50 (v/v) mixture of propan-1-ol and water containing 1% dithiothreitol (DTT) (w/v) at 60 °C for 30 min. After centrifugation (25 min, 22 °C, 3750 g), the volume of the combined supernatants was adjusted to be 2 mL with the extraction solution. Propan-1-ol (0.5 mL) was added to obtain a propan-1-ol concentration of 60%. After incubation (22 °C, 30 min) and centrifugation (25 min, 22 °C, 3750 g), the residue containing the HMW-GS was directly used either for SDS-PAGE or for total digestion.

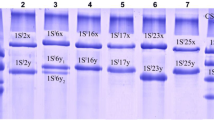

SDS-PAGE and in-gel digestions for untargeted nanoLC–MS/MS

A previously optimized SDS-PAGE system was used to separate the HMW-GS before in-gel digestion (Geisslitz et al. 2020). The isolated HMW-GS were incubated with sample buffer overnight under reducing conditions using DTT (50 mmol/L) at 22 °C. The solutions were heated for 10 min at 60 °C and 12 µL were loaded into the wells of a Novex 6% Tris–glycine Gel, WedgeWell format (1.0 mm, 10-well, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The proteins were separated using a tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane (Tris)-glycine buffer (25 mmol/L Tris, 192 mmol/L glycine, pH 8.3) at 225 V and 125 mA. After gel electrophoresis, the proteins were fixed in trichloroacetic acid (12%), stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (3 mmol/L) and destained with mixtures of methanol, water and acetic acid.

In-gel digestion was performed as described elsewhere (Geisslitz et al. 2020). In brief, bands were cut out with a scalpel and transferred into tubes (Table 1). Bands were again destained twice with destaining solution containing ammonium bicarbonate (25 mmol/L) in water/acetonitrile (50/50, v/v). Reduction was carried out with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (0.05 mol/L) and alkylation with chloroacetamide (CAA) (0.5 mol/L). The bands were again washed two times with destaining solution and afterward the bands were dried with acetonitrile. Proteins were digested with a mixture of trypsin and chymotrypsin (enzyme–substrate ratio: 1:10). After digestion overnight, the solutions were transferred to a new tube and the peptides were extracted from the gel slice first with formic acid (1%, v/v) and second with a mixture of water/acetonitrile/formic acid (49/50/1, v/v/v). The combined solution was concentrated in a rotational vacuum concentrator (Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Osterode, Germany) and stored at − 20 °C prior to analysis.

Total digestion of isolated HMW-GS for targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM

The digestion of isolated HMW-GS was performed as described elsewhere (Geisslitz et al. 2020). In brief, the residue containing the isolated HMW-GS was dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of propan-1-ol and Tris buffer (0.5 mol/L, pH 8.5). Reduction was performed using TCEP and alkylation using CAA. After concentration in a rotational vacuum concentrator, the proteins were digested with a mixture of trypsin and chymotrypsin overnight (enzyme–substrate ratio: 1:20). The digestion was stopped with trifluoroacetic acid and the peptides were purified by solid-phase extraction (Supelco Discovery®, DSC-18, 100 mg volume). The peptides were eluted with water/acetonitrile/formic acid (49.9/50/0.1, v/v/v) and concentrated in a rotational vacuum concentrator and stored at − 20 °C prior to analysis.

Untargeted nanoLC–MS/MS analysis of in-gel digestions

The in-gel digestions were analyzed by nanoLC–MS/MS as described in Geisslitz et al. (2020).

Targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM analysis

A Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC system (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was coupled to a Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The digests were dissolved in 100 µL water containing acetontrile (2%) and formic acid (0.1%) and separated by an Acquity UPLC® column (HSS T3, 1.8 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The injection volume was 10 µL, the flow rate was 0.2 mL/min, solvent A was water (0.1% formic acid), solvent B was acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid), the gradient was 0–1 min 5–8% B, 1–14 min 8–18% B, 15–18 min 18–25% B, 18–23 min 25–40% B, 23–25 min 40–80% B, 25–27 min 80% B, 27–28 min 80–5% B, 28–35 min 5% B and the column temperature was 55 °C. The eluate from the analytical column was sprayed via a ESI source (ThermoFisher Scientific) into the MS at a source voltage of 3.5 kV, at a capillary temperature of 290 °C and S‐lens level of 50 (sheath gas flow rate: 40, aux gas flow rate: 10, sweep gas flow rate 1, aux gas heater temperature: 100 °C). The Q Exactive Plus was set to PRM modus with a resolution of 17,500, injection time of 50 ms, an automatic gain control of 2e4, an isolation width of 1.6 m/z and a normalized collision energy of 18, 23 and 27 for fragmentation. A maximum of 120 precursors were scanned per method.

Identification of 14 HMW-GS for targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM

The nanoLC–MS/MS raw data of the in-gel digestions were evaluated by MaxQuant (version 2.0.3.0) (Cox and Mann 2008) using a UniProtKB database with the taxonomy “4565” (Triticum aestivum) downloaded on 8 June 2023, which contained 147,541 entries. In general, the default settings were enabled. Carbamidomethylation at cysteines was set as fixed modification, oxidation at methionine and acetyl at protein N-terminus as variable modification, chymotrypsin and trypsin as hydrolytic enzymes and match between runs were chosen.

The output file “proteinGroups.txt” of the MaxQuant search was imported in Microsoft Excel 2016 and those entries containing the keywords “high”, “HMW” and/or “glutenin” were marked (Online Resource 2). Each of these accessions was searched in UniProtKB and the information provided there was added in the Excel sheet as variation name (e.g., “Dy12”). If no information was available, “HMW” was added. Entries containing less than 200 amino acids were labeled as “fragment”. Subsequently, the entries labeled as “fragment” were deleted.

In the second step, the in-gel digestions were evaluated with PEAKS®XPro (version 10.6, Bioinformatics Solutions Inc., Waterloo, ON, Canada). As database, the reduced database from the MaxQuant search containing 96 proteins was used and each cut band was evaluated separately. The default settings were enabled for data refinement, DeNovo and database search. Carbamidomethylation at cysteines was set as fixed modification and chymotrypsin and trypsin as hydrolytic enzymes. The results were filtered on false discovery rate of 1% on peptide level.

Selection of marker peptides for targeted LC–MS/MS

For the selection of marker peptides, Skyline (version 23.1.0.268) (MacLean et al. 2010) was used. The peptide settings were: Enzyme: Cleaving after F, W, Y, L, R, K, but not if P is present; max. missed cleavages: 3; min. peptide length: 8; max. peptide length: 54; exclude N-terminal AAs: 0; modifications: Carbamidomethyl (C). The transition settings were: Precursor and product ion mass: Monoisotopic; precursor charges: 2, 3, 4, 5; ion charges: 1; ion types: y, b; product ion selection: From ion 3 to last ion; min. m/z: 50; max. m/z: 1500. The amino acid sequences of the 14 main HMW-GS (Online Resource 3) were added to Skyline and the peptides meeting following criteria were chosen for the first PRM screening: (1) Identified unique peptides from a second PEAKS search with the raw data of the in-gel digests, but as one big sample set, and as database only the 14 main proteins. (2) Unique peptides according to Skyline without a missed cleavage. (3) Peptides that were unique within By (By8, By9, By15 and By18), but not to Ax, Dx and Dy and peptides from Bx17 that were unique to all others, but not to Bx7 (Online Resource 4).

For the first screening, a pooled sample containing Event, Lear, Sonett, Tabasco, Mulan and Ambition (Table 1), which covered all HMW-GS, was analyzed by targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM. The PRM first screening results were imported into Skyline and peptides were deleted that showed no overlapping MS2 fragments from at least five fragment traces. The remaining peptides were confirmed by LC–MS/MS-PRM with a lower number of precursors per method (maximal 50) scanning the pooled sample. Peptides with ambiguous fragments were again deleted.

As next step, the six samples were measured individually by targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM. Peptides that were not present in the sample that should contain the respective HMW-GS or peptides that were present in all samples were deleted.

As last step, maximal three peptides for each HMW-GS were chosen for the final method based on a low number of missed cleavages (ideally no missed cleavages), high intensity and a high number of overlapping fragments from the same peptide.

Creation of the final targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM method

Only one precursor per peptide was chosen that showed the most overlapping fragments and had the highest intensity. A timed PRM method was created with a scanning time of at least ± 2 min around the peak maximum. In the final Skyline document maximal the ten most intensive fragments were kept and the others deleted. All samples were analyzed with the final method containing 31 peptides (Online Resource 5).

Application and validation of the final method

The LC–MS/MS-PRM raw data were imported into Skyline and synchronized integration was enabled. The integration was manually adjusted, so that the retention times were the same for one peptide in all samples, respectively. The Skyline window “Peak Areas – Replicate Comparison” was set to “Normalized to Total” and the proportional fragment distribution was used to set positive or negative identification. The mean was calculated over the fragments that contained the respective HMW-GS (Online Resource 6). Only fragments with a proportion higher than 5% were considered for identification. The respective HMW-GS was present, if the fragment proportion of more than the half of fragments with higher value than 5% varied only maximal ± 10% from the mean. With this identification criterion it was possible to group the samples with known composition into “correct identification” (the respective HMW-GS should be present and was detected), “false negative identification” (it should be present, but was not detected), “correct absence” (it should be not present and was not detected) and “false positive identification” (it should be not present, but it was detected), and the unknown samples into “presence of” and “absence of” the respective peptide.

Sequence alignment and peptide searches

Two proteins were aligned with the “Align” tool within UniProtKB using the Clustal Omega program to obtain the sequence identity (Sievers & Higgins 2018). More than three proteins were aligned with Tcoffee and the average distance was calculated with BLOSUM62 (Notredame et al. 2000) using the JalView application (version 2.11.4.1) (Waterhouse et al. 2009). Peptides were searched with the “Peptide search” tool within UniProtKB (Chen et al. 2013).

Results

A schematic overview of the steps for the creation of the targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM method is shown in Fig. 1.

Creation of an HMW-GS database

The MaxQuant search of the in-gel digestions revealed 95 protein groups including 12 contaminants (Online Resource 2) in the 18 cut bands (Table 1). Within the remaining 83 wheat protein groups, 35 protein groups contained the keywords “high”, “HMW” and/or “glutenin”. In some protein groups only one protein was present, but the largest protein group contained 14 proteins, which had a sequence identity of more than 85%. In total, 136 individual proteins were identified of which 40 proteins were fragment sequences and deleted, because they did not reflect a complete sequence of HMW-GS. The remaining 96 proteins corresponded to 33 protein groups and covered the HMW-GS Ax1, Ax2, Dx2, Dx5, Bx6, Bx7, By8, By9, Bx14, By15, Bx17, By18, By20, Bx23, Dy10 and Dy12. No entry corresponded to the HMW-GS Dx3 and a UniProtKB search revealed no entry for Dx3 in T. aestivum (8th December 2023).

Because MaxQuant summarized the proteins in protein groups due to a very high similarity, it was proven again as before (Geisslitz et al. 2020) that MaxQuant was not the best software tool to identify and characterize individual wheat HMW-GS, but PEAKS was more suited. However, other software tools were not tested and might be also well suited.

Identification of the main proteins for targeted analysis

As second step, the in-gel digestions were evaluated using PEAKS searching against the small database with 96 proteins. Due to the insufficient separation of some bands (Table 1), not all cut bands contained only one HMW-GS, but some also two HMW-GS (e.g., the first band from Tommi: Ax1 and Dx2). To identify the main HMW-GS accession, the identified protein had to have not only a high sequence coverage, but additionally a high −10lgP value (probability of correct identification) and a correct variation name based on the available information in the UniProtKB database. With exception of Dx3, one UniProtKB accession was chosen for each HMW-GS (Table 2) and details on how the HMW-GS were identified, can be found in Online Resource 3.

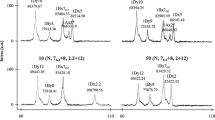

An average distance tree based on multiple sequence alignment of the 14 HMW-GS showed (Fig. 2) that there were five main groups with high sequence identity and the five groups were according to the chromosome (Ax, Bx, By, Dx and Dy), what confirmed that a correct accession was chosen for each HMW-GS. High identity was found for Ax1 and Ax2*, Dx2 and Dx5, Bx7 and Bx14, By8 and By15, By9 and By18, Dy10 and Dy12, respectively.

Identification of unique peptides within the 14 main HMW-GS

No unique peptides were identified for Bx7, By8 and By9 by PEAKS (Table 2). Between two and 22 unique peptides were identified for the other HMW-GS. Because the number of potential marker peptides was very low for some HMW-GS (e.g., two for By18 and three for Bx17), not only the identified unique peptides were considered, but also peptides without missed cleavages that were assigned as unique by Skyline. However, this procedure only increased the number of unique peptides for Ax1, Ax2*, Dx2, Dx5, Bx6, Bx14, By15, Dy10 and Dy12, but not for Bx7, By8, By9, Bx17 and By18. Because Bx7 and Bx17 possess a sequence identity of 100% (Bx17 has 42 amino acids more than Bx7), peptides without missed cleavages that were unique versus all other HMW-GS, but not within Bx7 and Bx17, were added as well, what increased the number of peptides for Bx7 to seven and for Bx17 to ten (Table 2). The same was true for By9 and By18, which have a sequence identity of 99.9% (one exchange and By18 has 15 amino acids more than By9). The number of unique peptides without missed cleavages that were unique versus all other HMW-GS, but not within By9 and By18, was increased to ten for By9 and to twelve for By18. As By8 is quite similar to Dy10 (93.4% sequence identity) and Dy12 (94.8% sequence identity), peptides were added that were unique within the group of By, but not to other HMW-GS especially to Dy10 and Dy12, what increased the number of peptides for By8 to twelve and subsequently for Dy10 and Dy12 to 32 and 26, respectively. In total, 215 differing peptides were screened in the first screening.

In the pooled sample containing all HMW-GS, 83 differing peptides were confirmed (Online Resource 4). The reduction from 215 to 83 peptides is on the one hand due to the analysis of differing samples: For the selection of the 215 peptides, identified unique peptides from the in-gel digests and theoretical unique peptides without missed cleavages were scanned. Some of the identified unique peptides had a maximum number of three missed cleavages, what might be not repeatable in the total digests. However, peptides without missed cleavage might be detectable in the total digests, even though they were not identified in the in-gel digests. This means that in the total digests indeed other peptides might be present, but for the final method, robust and repeatable peptides should be selected. On the other hand, the identification algorithm within PEAKS might be not correct for all peptides, leading to false positive identifications, which was excluded by the PRM experiments.

The three identified unique peptides for Bx17 had at least two missed cleavages. It was not possible to confirm these peptides by PRM (Online Resource 4) and thus, Bx7 and Bx17 were not distinguishable with the final method. Even though the identified unique peptides for By18 had either no missed cleavage or only one missed cleavage, they were not detectable by PRM and thus, they were not repeatable and suitable. Therefore, By9 and By18 were not distinguishable as well. All peptides for By8 were also present in Dy12 and they cannot be assigned as unique and By8 was not identifiable, if Dy12 is present as well. Nevertheless, the peptides were kept, because it might be possible that if By8 is present in combination with Dy10, the peptides can be used to identify By8.

As only a pooled sample was previously analyzed by PRM, the individual samples were scanned on the remaining 83 peptides in the next step. With the exception of By15 (only two), at least three potential marker peptides were left per HMW-GS (Online Resource 4) and in total 56 differing peptides. As last step, the number of marker peptides was reduced (maximal three per HMW-GS) leading to 31 peptides in the final method (Online Resource 5).

Refinement of the final method

In the final method, the most peptides were measured as 2 + (17 peptides) and 3 + (12 peptides) and only two peptides as 4 + (Online Resource 5). Only for three peptides, less than ten fragments were detectable. The peptides were detectable with relatively evenly distributed y- and b-fragments with the exception of one peptide, as only y-fragments had the highest intensities.

The final method was applied to 37 samples with known and to 58 samples with unknown HMW-GS composition. First, it was checked, if the selected marker peptides were suitable for the detection of the individual HMW-GS.

Identification and detection of Ax

Two peptides were analyzed for Ax1 and Ax2*, respectively. Eleven cultivars contained Ax1, three cultivars Ax2*, one cultivar (Miras) both Ax1 and Ax2* and in 22 cultivars Ax was not expressed within the 37 samples with known HMW-GS composition. The fragments of the first peptide of Ax1 (P1) were mostly absent in cultivars having either Ax2* or no expression of Ax (Online Resource 6). On the other hand, most of the fragments of the second Ax1 peptide (P2) were present in these cultivars, but with exception of two cultivars (Genius and Tobak), the fragments were distributed completely different as in the cultivars having Ax1. In general, P1 seemed to be the more reliable peptide for the identification of Ax1. Similar was observed for the peptides of Ax2*. The fragments of the two peptides of Ax2* (P3 and P4) were mostly absent in cultivars having no Ax2* or had the wrong distribution. In general, both peptides seemed to be reliable for the identification of Ax2*.

Of the eleven cultivars containing Ax1, ten cultivars were unambiguously identified as Ax1, because both peptides of Ax1 and no peptides of Ax2* were present in these cultivars (Fig. 3A). In the remaining cultivar (Akteur), only one peptide of Ax1, but no peptide of Ax2* was identified, so that the tendency was the presence of Ax1. However, two cultivars (Genius and Tobak), in which Ax was actually not expressed, showed the same behavior as Akteur: One peptide of Ax1 (P2) was identified false positive. All other cultivars with no expression of Ax, contained no peptide of Ax1 and Ax2*. In only two (Event and Sonett) of the three cultivars having Ax2* both peptides of Ax2*, but not the peptides of Ax1, were identified. The absence of the Ax2* peptides in Konsul might be because the sample was not the cultivar Konsul, but another cultivar (see also the results of Bx). It was proven that Miras contained both Ax1 and Ax2*, because all four peptides were detected. The selected peptides for Ax1 and Ax2* worked well for the identification of Ax1 and Ax2* with the limitation that if only one of the two Ax1 peptides was present, it was ambiguous if Ax1 is indeed present or not.

Identification of Ax1 (P1, P2) and Ax2* (P3, P4) in samples with A known and (B) unknown HMW-GS composition. Gray box indicates identification. A Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS should be present. * Miras contains both Ax1 and Ax2*. B Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS was supposed to be present. The box with “?” indicates that it was not possible to state, if Ax1 was present or Ax was not expressed (n)

In 16 of the 58 samples with unknown HMW-GS composition, the two peptides of Ax1 (P1 and P2) were identified and thus, Ax1 was present (Fig. 3B). In three cultivars, both peptides of Ax2* (P3 and P4) were identified. For eleven cultivars, it was not possible to confirm the presence or absence of Ax1, because P2 was identified, but P1 not. There was no expression of Ax in almost half of the samples (28 cultivars), as P1, P2, P3 and P4 were not detectable. The identified HMW-GS composition of the samples with unknown combination is summarized in Online Resource 7.

Identification and detection of Dx and Dy

The expression of Dx and Dy is fixed prescribed, as Dx5 is always in combination with Dy10, and Dy12 can be in combination with Dx2 or Dx3. The combination of Dx2 and Dy12 was described to be present in 17 cultivars, that of Dx3 and Dy12 in four cultivars and that of Dx5 and Dy10 in 16 cultivars within the samples with known composition. Three peptides were analyzed for Dx2, Dx5 and Dy10, respectively, and two peptides for Dy12, no peptides (and no protein sequence) were available for Dx3. The fragments of the three peptides of Dx2 (P5, P6, P7) were present in the four cultivars having Dx3 (Ambition, Konsul, Oxal and Ritmo) with the correct distribution (Online Resource 6). As already stated, the final method was not able to distinguish Dx2 and Dx3.

On the other hand, the fragments were absent or showed the incorrect distribution in all cultivars with Dx5. The only exception was Format (Dx5), in which two peptides of Dx2 (P5 and P7) had the correct distribution. The results of Dx2 were in agreement with the findings of Dy12. The fragments of the peptides of Dy12 (P30 and P31) were absent or had the wrong distribution in cultivars that contained Dy10 with the exception that Bussard and Format (both Dy10) had the correct distribution for P30 and P31. Overall, P6, P30 and P31 seemed to be suited to identify Dx2 and Dy12.

The fragments of the three peptides for Dx5 (P8, P9, P10) were mostly present in all cultivars, but only the cultivars Ambition (P8, P10), Julius (P8, P9, P10) and Vuka (P8, P9, P10) that actually contain Dx2, had the correct distribution. The same was true for the three peptides for Dy10 (P27, P28, P29). Again, the three cultivars Ambition, Julius and Vuka showed the correct distribution of these three peptides.

Combining the findings of Dx2, Dx5, Dy10 and Dy12, the identification of these HMW-GS worked quite well, with some interesting findings (Fig. 4A): (i) The cultivar Vuka should contain Dx2 and Dy12, but the method showed clearly that this sample had Dx5 and Dy10. The most probable reason is that this sample was not the cultivar Vuka, but another cultivar. (ii) All eleven peptides were detected in the cultivar Julius and, furthermore, nine of eleven in Ambition, eight of eleven in Bussard and ten of eleven in Format. The intensities of the peptides that should be actually not present, were very low (maximal 10% compared to cultivars that contained the respective HMW-GS), so that the most probably reason might be that the flour was a mixture of more than one cultivar due to contamination during sowing or harvest. (iii) In Ares, one peptide of Dx2, in Akteur, one peptide of Dx5, and in JB Asano, one peptide of Dy10 was missing, respectively. This might be an issue of concentration, because the most abundant fragments were present, but the low abundant not, so that the distribution was not correct for these peptides. Taken together, the identification of Dx and Dy worked well and the peptides were suitable to detect Dx2, Dx5, Dy10 and Dy12.

Identification of Dx2 (P5, P6, P7), Dy12 (P30, P31), Dx5 (P8, P9, P10) and Dy10 (P27, P28, P29) in samples with A known and B unknown HMW-GS composition. Gray box indicates identification. A Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS should be present. * These cultivars contain Dx3 and Dy12. B Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS was supposed to be present. The box with “?” indicates that it was not possible to state the combination

In 45 of the 58 samples with unknown distribution, the combination Dx2 and Dy12 was identified (Fig. 4B), with the limitation that it could also be Dx3. Only two of the three peptides for Dx2 were identified in one cultivar (Niederbayerischer Braun). Additionally, in this cultivar and in a second one (Noerdlinger Roter) one peptide of Dy10 (P27) was identified and in the latter one also one peptide of Dx5 (P8). Furthermore, in seven cultivars, the second peptide of Dy10 (P28) was identified as well, but no other peptides of Dx5 and Dy10. However, the most probable was that these nine cultivars contain Dx2 and Dy12. In five cultivars, only the peptides of Dx5 and Dy10 were identified and thus, this combination was present. In one cultivar (Roter Saechsischer Landweizen), all peptides of Dx5, Dy10 and Dy12 were identified, but no peptides of Dx2 and thus, the combination of Dx5 and Dy10 was the most probable one. Again, five cultivars contained all eleven peptides and one cultivar (Ackermanns Bayernkönig) eight and one cultivar (Merlin) ten of the eleven peptides and it was not possible to assign a HMW-GS combination.

Identification and detection of Bx

Three peptides were analyzed each for Bx6, Bx7/Bx17 and Bx14. As already explained, it was not possible to distinguish between Bx7 and Bx17 with the final method. Eight cultivars are described to contain Bx6, 23 cultivars Bx7, one cultivar Bx6 and/or Bx7 (Format), two cultivars Bx7*, one cultivar Bx14 (Sonett) and two cultivars Bx17 within the 37 samples with known HMW-GS composition.

The fragments of the three peptides of Bx6 (P11, P12 and P13) were either absent or showed the incorrect distribution in cultivars having Bx7, Bx17 or Bx14 with one exception as Bussard had the correct distribution of P12 (Online Resource 6). Thus, especially, P11 and P13 were suitable to identify Bx6.

The fragments of the three peptides of Bx7 and Bx17 (P14, P15 and P16) showed the correct distribution in Konsul und Ritmo, even though both cultivars contain Bx6. None of the three peptides were better or worse suited for the identification of Bx7 and Bx17.

Only a few fragments of the three peptides for Bx14 (P23, P24 and P25) were detectable in samples that do not contain Bx14 and the distribution varied completely from that of Sonett. Even though only this one cultivar with Bx14 was analyzed, all three peptides were suitable to identify Bx14 unambiguously.

Six of the eight cultivars containing Bx6 were unambiguously identified, because only the peptides of Bx6 were detectable, but not those of Bx7/Bx17 and Bx14 (Fig. 5A). In Ritmo and Konsul having actually Bx6, not only the Bx6 peptides, but also the peptides of Bx7/B17 were detected. The reason for this might be again the presence of a mixture of cultivars. In Format, only the peptides of Bx7, but not of Bx6 were identified, so that this flour of Format did not contain both, but only Bx7. Only in Bussard that should contain only Bx7, one peptide of Bx6 was additionally identified, but with very low intensity. In addition to the fact that also Dy12 peptides were present (Fig. 4A) in Bussard, this is also an indication that this sample is contaminated with another cultivar(s). In all other cultivars containing Bx7 or Bx17, only these peptides were identified and no difference between cultivars with Bx7 or Bx7* was present. With only some limitations (Konsul and Ritmo), the identification of Bx6, Bx7/Bx17 and Bx14 worked unambiguously and very well.

Identification of Bx6 (P11, P12, P13), Bx7/Bx17 (P14, P15, P16) and Bx14 (P23, P24, P25) in samples with A known and B unknown HMW-GS composition. Gray box indicates identification. A Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS should be present. *Format contain both Bx6 and/or Bx7. + Caribo and Cubus contain Bx7*. B Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS was supposed to be present. Bx13 was predicted, but there was no evidence. The box with “?” indicates that it was not possible to state the combination

In 15 of the 58 samples with unknown distribution, Bx6 was identified and all three peptides were identified (Fig. 5B). In three cultivars, only two of the three peptides (P11 and P12) and in eight cultivars only one peptide (P12) was identified, but no peptides of Bx7/Bx17. Only with this information, the most probable was that Bx6 was present, but this was not for sure (see the results of By). In 26 cultivars, Bx7 or Bx17 were unambiguously identified, as the three peptides of Bx7/Bx17 were present. Only one cultivar (KWS Sharki) contained Bx14, as the three peptides for Bx14 were identified. In five samples, the composition was not identifiable, because in two of them (Hadmerslebener Qualitas and Pilot) all peptides of Bx6 and Bx7/Bx17 were present, and in the other three cultivars at least one Bx6 peptide was identified.

Identification and detection of By

The assignment of By was confronted with the biggest issues. The three peptides of By9 and By18 were present in both HMW-GS and thus, they were not distinguishable. The three peptides of By8 were also present in the sequence of Dy12. The only peptide of By15 was at least unique for By15. Thirteen cultivars contained By8 (of that ten in combination with Dy12 and three with Dy10), 13 cultivars By9, four cultivars By(9), one cultivar (Sonett) By15, two cultivars By18 and in four cultivars By was not expressed (of that three in combination with Dy12) within the 37 samples with known HMW-GS composition. The fragments of the peptides for By8 (P17, P18 and P19) were present in some samples that didn’t contain By8 and/or Dy12, but only P17 and P18 had the correct distribution in Bussard. The fragments of the three peptides of By9/By18 (P20, P21 and P22) were present in most samples and a lot of samples that didn’t contain By9/By18 showed also the correct distribution. The fragments of the peptide for By15 (P26) were present in almost all samples, but they had a completely differing composition compared to Sonett.

The peptides P17, P18 and P19 that are present in By8 and Dy12 were identified in all samples containing Dy12 (Fig. 6A) with two exceptions: i) They were not present in Vuka, but it was already shown that this sample contained Dx5 and Dy10; ii) one peptide (P19) was not present in Lear. Additionally, in Format (P17, P18 and P19) and Bussard (P17 and P18), the peptides were also identified, even though they contained Dy10. This is in agreement with the findings of the other two peptides of Dy12 (P30 and P31), which were present in Bussard and Format (Fig. 4A). The cultivars Dekan and Jubilar that had By8, showed no presence of the By8 peptides. To conclude, P17, P18 and P19 were not suitable to detect By8 in the sample set, but only Dy12.

Identification of By8/Dy12 (P17, P18, P19), By9/By18 (P20, P21, P22) and By15 (P26) in samples with A known and B unknown HMW-GS composition. Gray box indicates identification. A Boxes at the right side indicate, which HMW-GS should be present for By and Dy. B Boxes at the right indicate, which Bx was supposed to be present (Fig. 5B). The box with “?” indicates that it was not possible to state the combination. The box with “Bx6/Bx7/?” indicates that cultivars with various Bx were summarized

The peptide of By15 (P26) was only present in Sonett, but one peptide (P22) of By9/By18 was also present in Sonett. However, it was for sure, that if the peptides of Bx14 (P23, P24 and P25) and the peptide of By15 (P26) were present, the sample contain the combination Bx14 and By15.

At least one of the peptides for By9 and By18 (P20, P21 and P22) was present in all samples with some exceptions: (i) The peptides were absent in the four cultivars, in which By was not expressed; (ii) the cultivar JB Asano contained them not, even though By9 should be present. Thus, it was not possible to conclude that if none of the peptides of By was present (as it is for Cubus) By is nor expressed. Taken together, it was only possible to identify By15 confidentially, but the other variations of By including no By expression not.

Nevertheless, the presence of the peptides P17-P22 and P26 in the samples with unknown HMW-GS combination should be discussed (Fig. 6B). With exception of five cultivars, in all cultivars at least two peptides of By8/Dy12 (P17, P18 and P19) were detected and the ones having none of the peptides also did not contain Dy12 peptides (P30 and P31) (Fig. 4B). Some similarities and relations were identifiable in the sample set with unknown HMW-GS composition, but it was not possible to assign the By variety. For example, if all peptides of By8/Dy12 (P17, P18 and P19) and By9/By18 (P20, P21 and P22) were present, Bx7 was suspected to be present or no assignment was possible. If only P22 was missing, but P17-P21 were present, Bx6 was suspected to be present or no assignment was possible. Instead, if P20 and P22 was missing, Bx6 or Bx7 was suspected to be present. To conclude in agreement with the sample set with known composition, no statement about By8, By9 and By18 was possible.

In four cultivars, the peptide of By15 (P26) was identified, but only in KWS Sharki, the peptides of Bx14 were identified as well, so that only this cultivar had the combination Bx14 and By15. Interestingly, the other three cultivars (Heges Basalt, Nordost Sandomir and Strengs Marschall) with P26 contained only two of three peptides of Bx6 (P11 and P12), but P13 not (Fig. 5B). This phenomenon was not observed in the cultivars with known presence of Bx6 (Fig. 4A). The most probable reason for this might be that these three cultivars had an HMW-GS combination that was not present in the sample set with known HMW-GS composition what might be also true for the eight cultivars that contained only one peptide of Bx6 (P12), but no other Bx peptides. A UniProtKB peptide search revealed that P12 is also present and cleaved in three UniProtKB accessions labeled with the variation name Bx13 (B8ZX17, A5HMG1 and H9B854) and thus, the nine cultivars could also contain Bx13. However, the frequency of Bx13 is quite low (< 1%) in cultivars worldwide (Grausgruber-Gröger et al. 1997; Igrejas et al. 1999; Nakamura 2000), while the frequency of Bx13 in our sample set would be very high (~ 9%). According to the initial catalog of HMW-GS by Payne and Lawrence (1983), Bx13 is in combination with By16 or By19. A peptide search revealed that only one peptide of By9/By18 (P21) is also present and cleaved in an accession labeled as By16 (A5HMG2) and this peptide is only present in one (Elixer) of the nine cultivars. The nine cultivars with suspected Bx13 contained either only one or two peptides of By9/By18 or even none so that no further statements were possible.

Discussion

The quality and completeness of the protein database is one of the most important prerequisites to develop a targeted LC–MS/MS method for the identification and quantitation of proteins. Since the genome of wheat cultivar Chinese Spring has been sequenced (The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC), 2018), the database is more accurate. However, there are different variations and combinations of HMW-GS and only one cultivar is not sufficient to display the complexity of HMW-GS. It is well known that HMW-GS do not show only three, four or five spots in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, but on average eight spots per HMW-GS (Dupont et al. 2011) that vary both in isoelectric point and molecular weight. These variations might be due to post-translational modifications (PTM) and/or amino acid exchanges, insertions and deletions (reviewed by Cunsolo et al. (2004)). There is currently no consensus in literature whether PTM exist at HMW-GS. It is usually assumed that HMW-GS have no PTM, such as glycosylation, but a new study from 2020 showed that HMW-GS can be modified (Bacala et al. 2020). The improvement of proteomic techniques contributes to new knowledge, but available literature on HMW-GS was often published more than ten years ago. It was shown that there is one less amino acid in a Dx2 compared to the amino acid sequence present in UniProtKB (Lagrain et al. 2014). With regard to our study, we can only speculate at this point why, for example, only one of the two Ax1 marker peptides was detected in some cultivars (e.g., PTM, amino acid variation). Further DDA analyses and de novo sequencing could explain this phenomenon in future.

Compared to other studies, often the same UniProtKB accession was identified. For example, the accession P10388 was used for the identification of Dx5 in four studies from 2008 to 2017 (Aghagholizadeh et al. 2017; Lagrain et al. 2012; Qian et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012). Furthermore, some accessions were used that differed very slightly and had a very high sequence identity, e.g., Q03872 for Ax1 (only one exchange to A0A059UHD1) or Q41553 for Ax2* (only two exchanges to A0A060MZP1) (Lagrain et al. 2012; Qian et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012). Instead, also accessions were used that differed more in the amino acid sequence compared to the ones used in the current study. For example, Q6UKZ5 was used for Bx14 (Wang et al. 2012) that has a sequence identity of only 96.6% to A0A3G4ZJR3 and several exchanges, deletions and insertions. Q0Q5D8 was identified for By8 (Lagrain et al. 2012) that has a low sequence identity of 94.7% to A0A1G4P1V2 and several exchanges, deletions and insertions. This varying identification might be the reason that the new method is not able to identify By8. Q0Q5D8 was identified in the first MaxQuant search (Online Resource 2), but it was in a protein group with By9 and By18. In the subsequent PEAKS search, Q0Q5D8 was not identified anymore (Online Resource 3). This shows that not only the database is crucial for method development, but also the evaluation software. Further optimizations (e.g., analysis of more cultivars, repeated PRM screenings) are required to expand the current LC–MS/MS-PRM method for the identification of By8, By9 and By18.

In the next step, the marker peptides have to fulfill further requirements. For reproducibility, the peptides should be fully cleaved and thus, the correct enzyme must be chosen. For example, trypsin leads only to eight peptides with an amino acid number between eight and 30 in Dx5 (P10388), but the combination of trypsin and chymotrypsin to a lot of peptides with less than eight amino acids and at the same time several peptides with more than 30 amino acids. Especially the motif “YYPTS” occurs frequently in the sequence and it is often not cleaved (Online Resource 4), even though there should be a cleavage after the first tyrosine (Y). This might be, because the cleavage is sterically hindered, even though the proline (P) is only very close but not adjacent. For the current method, it was not possible to select only peptides without missed cleavage, because the peptides without missed cleavage were not detectable or not unique.

Compared to other studies, only a low number of peptides were identified both in the current study and in literature and even a lower number overlapped for the marker peptides. Aghagholizadeh et al. (2017) identified only two overlapping peptides, Qian et al. (2008) only three, Martínez-Esteso et al. (2016) only one and Schalk et al. (2018) none. Only the two chosen peptides P4 (Dx2) and P5 (Dx5) were identified in only one study, respectively (Martínez-Esteso et al. 2016; Qian et al. 2008). One reason for this is that in these studies, either trypsin or chymotrypsin was used instead of the enzyme mixture leading to different cleavage sites. Furthermore, the aim in most publications was not the development of a targeted LC–MS/MS method to differentiate HMW-GS, but the peptides should not represent one single HMW-GS, but ideally the entirety of HMW-GS (Martínez-Esteso et al. 2016; Schalk et al. 2018).

The frequency of the respective Ax, Bx, Dx and Dy is summarized in Table 3. The frequency of Ax1 (33%), Ax2* (7%) and no expression of Ax (60%) was almost the same in the cultivars with known and unknown composition. Instead, the composition of Dx5 and Dy10 was underrepresented in the sample set with unknown composition (12%) compared to the samples with known composition (43%). The frequencies of these HMW-GS combinations varied greatly in samples worldwide. For example, the frequency of Ax1/Ax2*/NULL was evenly in Portuguese cultivars (29%/34%/37%) (Igrejas et al. 1999) and Chinese cultivars (43%/32%/25%) (Gao et al. 2018) or biased in another set of Chinese cultivars (5%/14%/81%) (Nakamura 2000). In Portuguese cultivars, Dy10 (65%) is more frequent than Dy12 (Igrejas et al. 1999), but in Chinese ones Dy12 (more than 75%) (Gao et al. 2018; Nakamura 2000). The underrepresentation of Dx5 and Dy10 in samples with unknown composition might be due to breeding. Dx5 and Dy10 are associated with better baking quality (Payne et al. 1987). One of the aims of breeding was to improve baking quality, so it is clear, why there is more Dx5 and Dy10 in the sample set with known composition (modern cultivars), whereas old cultivars (first registered before 1950) (Pronin et al. 2020) and landraces (Jahn et al. 2024) have a higher proportion of Dx2 and Dy12 or the composition is unknown. Similar observation was made in Chinese old varieties and landraces (Dai et al. 2020).

LC–MS/MS analysis of HMW-GS has advantages and disadvantages compared to SDS-PAGE, RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF. Sample preparation is more time-consuming compared to the other methods, because the HMW-GS need to be extracted and digested as well. Furthermore, the required equipment (LC and MS) is significantly more expensive compared to SDS-PAGE and specific expertise is required for data analysis. Nevertheless, MS-based techniques allow far more insights on molecular level compared to SDS-PAGE and RP-HPLC, especially if the DDA modus is used. Even quantitative statements are possible, which is not possible by SDS-PAGE. Two disadvantages of SDS-PAGE are that a perfect resolution and separation of all HMW-GS is not always achieved and the evaluation is performed manually. This is where the newly developed LC–MS/MS method demonstrates the advantages. If the marker peptide is present, it can be concluded that the respective HMW-GS is present with high probability. Even though the newly developed targeted LC–MS/MS-PRM method does not cover all HMW-GS, this is the first MS-based method on peptide level for the differentiation of HMW-GS. Improvements and optimization of the method requires the advancement of the wheat protein database.

Conclusion

The final LC–MS/MS-PRM method can be used to unambiguously identify Ax1, Ax2*, Bx6, Bx14, Dx2, Dx5, Dy10, Dy12, as well as no expression of Ax, but cannot distinguish Bx7 and Bx17 and identify the variation of By due to high sequence identity to Dy and within By. The correct identification of By requires more accurate information within the protein database, because only four HMW-GS proteins (P10388: Dx5; P10387: Dy10; P08489: probably Dx2; P08488: Dy12) are reviewed proteins within the UniProtKB database and none for By. In comparison to other well-established methods such as SDS-PAGE, RP-HPLC and MALDI-TOF–MS, LC–MS/MS has a very high resolution, is less biased by interpretation and provides more insights on molecular level, especially, if the peptides are not only analyzed by LC–MS/MS-PRM, but also by untargeted LC–MS/MS. The described procedure can be applied to expand the LC–MS/MS-PRM method for more HMW-GS or even to other wheat proteins, e.g., LMW-GS, in future and can be developed further to quantitate HMW-GS either label-free or with heavy isotopic labeled standards. Last, we showed that the characterization and detection of HMW-GS is still confronted with issues not only due to the incomplete protein database, but the identification results also depend on the evaluation software, which has to be taken into account, when analyzing wheat proteins and especially HMW-GS.

Data availability

Mass spectrometry data and evaluations of the untargeted LC–MS/MS experiments have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with following dataset identifier: PXD058934. Mass spectrometry data of the LC–MS/MS-PRM experiments are publicly available on Panorama Public (https://panoramaweb.org/FoMOPy.url).

References

Aghagholizadeh R, Kadivar M, Nazari M, Mousavi F, Azizi MH, Zahedi M et al (2017) Characterization of wheat gluten subunits by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry and their relationship to technological quality of wheat. J Cereal Sci 76:229–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2017.06.016

Bacala R, Fu BX, Perreault H, Hatcher DW (2020) Quantitative LC-MS proteoform profiling of intact wheat glutenin subunits. J Cereal Sci 94:102963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2020.102963

Chen C, Li Z, Huang H, Suzek BE, Wu CH (2013) A fast peptide match service for UniProt Knowledgebase. Bioinformatics 29(21):2808–2809. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt484

Colgrave ML, Byrne K, Howitt CA (2017) Food for thought: selecting the right enzyme for the digestion of gluten. Food Chem 234:389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.05.008

Cox J, Mann M (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol 26(12):1367–1372. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.1511

Cunsolo V, Foti S, Saletti R (2004) Mass spectrometry in the characterization of cereal seed proteins. Eur J Mass Spectrom 10(3):359–370. https://doi.org/10.1255/ejms.609

Dai S, Xu D, Yan Y, Wen Z, Zhang J, Chen H et al (2020) Characterization of high- and low-molecular-weight glutenin subunits from Chinese Xinjiang wheat landraces and historical varieties. J Food Sci Technol 57(10):3823–3835. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-020-04414-5

Dong K, Hao C, Wang A, Cai M, Yan Y (2009) Characterization of HMW glutenin subunits in bread and tetraploid wheats by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Cereal Res Commun 37(1):65–73. https://doi.org/10.1556/crc.37.2009.1.8

Dupont FM, Vensel WH, Tanaka CK, Hurkman WJ, Altenbach SB (2011) Deciphering the complexities of the wheat flour proteome using quantitative two-dimensional electrophoresis, three proteases and tandem mass spectrometry. Proteome Sci 9:10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-5956-9-10

Gao Z, Tian G, Wang Y, Li Y, Cao Q, Han M et al (2018) Allelic variation of high molecular weight glutenin subunits of bread wheat in Hebei province of China. J Genetics 97(4):905–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12041-018-0985-x

Geisslitz S, America AHP, Scherf KA (2020) Mass spectrometry of in-gel digests reveals differences in amino acid sequences of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits in spelt and emmer compared to common wheat. Anal Bioanal Chem 412:1277–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-019-02341-9

Grausgruber-Gröger S, Oberforster M, Werteker M, Grausgruber H, Lelley T (1997) HMW glutenin subunit composition and bread making quality of Austrian grown wheats. Cereal Res Commun 25:955–962. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03543902

Halder T, Choudhary M, Liu H, Chen Y, Yan G, Siddique KHM (2022) Wheat proteomics for abiotic stress tolerance and root system architecture: current status and future prospects. Proteomes 10(2):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes10020017

Hurkman WJ, Tanaka CK (2007) Extraction of wheat endosperm proteins for proteome analysis. J Chromatogr B 849(1):344–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.11.047

Igrejas G, Guedes-Pinto H, Carnide V, Branlard G (1999) The high and low molecular weight glutenin subunits and ω-gliadin composition of bread and durum wheats commonly grown in Portugal. Plant Breed 118(4):297–302. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1439-0523.1999.00378.x

Jahn N, Konradl U, Fleissner K, Geisslitz S, Scherf KA (2024) Protein composition and bread volume of German common wheat landraces grown under organic conditions. Cur Res Food Sci 9:100871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crfs.2024.100871

Jang Y-R, Kim S, Sim J-R, Lee S-B, Lim S-H, Kang C-S et al (2021) High-throughput analysis of high-molecular weight glutenin subunits in 665 wheat genotypes using an optimized MALDI-TOF–MS method. Biotech 11(2):92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-020-02637-z

Khalid A, Hameed A (2019) Characterization of Pakistani wheat germplasm for high and low molecular weight glutenin subunits using SDS-PAGE. Cereal Res Commun 47(2):345–355. https://doi.org/10.1556/0806.47.2019.13

Lagrain B, Rombouts I, Delcour JA, Koehler P (2014) The primary structure of wheat glutenin subunit 1Dx2 revealed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Cereal Sci 60(1):131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2014.01.024

Lagrain B, Rombouts I, Wieser H, Delcour JA, Koehler P (2012) A reassessment of the electrophoretic mobility of high molecular weight glutenin subunits of wheat. J Cereal Sci 56(3):726–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcs.2012.08.003

Lee MH, Kim K-M, Kang C-S, Yoon M, Jang K-C, Choi C (2024) Development of PCR-based markers for identification of wheat HMW glutenin Glu-1Bx and Glu-1By alleles. BMC Plant Biol 24(1):395. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-05100-w

Lee S-B, Yang Y-J, Lim S-H, Gu YQ, Lee J-Y (2021) A rapid, reliable RP-UPLC method for large-scale analysis of wheat HMW-GS alleles. Molecules 26(20):6174. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26206174

Lu Y, Ji H, Chen Y, Li Z, Timira V (2023) A systematic review on the recent advances of wheat allergen detection by mass spectrometry: future prospects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 63(33):12324–12340. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2022.2101091

MacLean B, Tomazela DM, Shulman N, Chambers M, Finney GL, Frewen B et al (2010) Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 26(7):966–968. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054

Martínez-Esteso MJ, Nørgaard J, Brohée M, Haraszi R, Maquet A, O’Connor G (2016) Defining the wheat gluten peptide fingerprint via a discovery and targeted proteomics approach. J Proteomics 147:156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2016.03.015

Muccilli V, Lo Bianco M, Cunsolo V, Saletti R, Gallo G, Foti S (2011) High molecular weight glutenin subunits in some durum wheat cultivars investigated by means of mass spectrometric techniques. J Agric Food Chem 59(22):12226–12237. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf203139s

Nakamura H (2000) Allelic variation at high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit Loci, Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1. Jpn Chin Hexaploid Wheats Euphytica 112(2):187–193. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1003888116674

Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J (2000) T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 302(1):205–217. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042

Payne PI, Holt LM, Law CN (1981) Structural and genetical studies on the high-molecular-weight subunits of wheat glutenin. Theor Appl Genet 60(4):229–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02342544

Payne PI, Lawrence GJ (1983) Catalogue of alleles for the complex gene loci, Glu-A1, Glu-B1, and Glu-D1 which code for high-molecular-weight subunits of glutenin in hexaploid wheat. Cereal Res Commun 11(1):29–35. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf990151p

Payne PI, Nightingale MA, Krattiger AF, Holt LM (1987) The relationship between HMW glutenin subunit composition and the bread-making quality of British-grown wheat varieties. J Sci Food Agric 40(1):51–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2740400108

Pronin D, Börner A, Weber H, Scherf KA (2020) Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) breeding from 1891 to 2010 contributed to increasing yield and glutenin contents but decreasing protein and gliadin contents. J Agri Food Chem 68(46):13247–13256. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.0c02815

Qian Y, Preston K, Krokhin O, Mellish J, Ens W (2008) Characterization of wheat gluten proteins by HPLC and MALDI TOF mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 19(10):1542–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasms.2008.06.008

Ravel C, Faye A, Ben-Sadoun S, Ranoux M, Dardevet M, Dupuits C et al (2020) SNP markers for early identification of high molecular weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GSs) in bread wheat. Theor Appl Genet 133(3):751–770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03505-y

Schalk K, Koehler P, Scherf KA (2018) Targeted liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry to quantitate wheat gluten using well-defined reference proteins. PLoS ONE 13(2):e0192804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192804

Shin D, Cha J-K, Lee S-M, Kabange NR, Lee J-H (2020) Rapid and easy high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit identification system by Lab-on-a-Chip in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plants 9(11):1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111517

Sievers F, Higgins DG (2018) Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci 27:135–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3290

The International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium (IWGSC) (2018) Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science 361(6403):eaar7191. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar7191

Vensel WH, Dupont FM, Sloane S, Altenbach SB (2011) Effect of cleavage enzyme, search algorithm and decoy database on mass spectrometric identification of wheat gluten proteins. Phytochemistry 72(10):1154–1161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.002

Visioli G, Comastri A, Imperiale D, Paredi G, Faccini A, Marmiroli N (2016) Gel-based and gel-free analytical methods for the detection of HMW-GS and LMW-GS in wheat flour. Food Anal Methods 9(2):469–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12161-015-0218-3

Wang K, An XL, Pan LP, Dong K, Gao LY, Wang SL et al (2012) Molecular characterization of HMW-GS 1Dx3t and 1Dx4t genes from Aegilops tauschii and their potential value for wheat quality improvement. Hereditas 149(1):41–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5223.2011.02215.x

Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ (2009) Jalview Version 2 - a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25(9):1189–1191. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033

Wieser H, Koehler P, Scherf KA (2023) Chemistry of wheat gluten proteins: qualitative composition. Cereal Chem 100(1):23–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/cche.10572

Yao C, Zhang C, Bi C, Zhou S, Dong F, Liu Y et al (2022) Establishment and application of multiplex PCR systems based on molecular markers for HMW-GSs in wheat. Agriculture 12(4):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12040556

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hong-Dao Truong (KIT) and Bert Schipper (WUR) for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This IGF Project of the FEI was supported within the program for promoting the Industrial Collective Research (IGF) of the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), based on a resolution of the German Parliament. Project 01IF21944N. Sabrina Geisslitz received funding of the Karlsruhe House of Young Scientists (KHYS) via the Research Travel Grant to conduct a research stay at Wageningen Research and University. Open Access enabled by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Communicated by Ankica Kondic-Spika.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Geisslitz, S., America, A.H.P. Differentiation of wheat high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits by targeted LC–MS/MS. CEREAL RESEARCH COMMUNICATIONS 53, 2517–2533 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42976-025-00676-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42976-025-00676-x