Abstract

The purpose of this study is to empirically validate the Family Cultural Wealth Survey (FCWS) by centering Black families with young children by (1) understanding the factor structure of the FCWS; (2) examining differences by income, family structure, and parental education; and (3) exploring the validity of the tool by examining its association with parental experiences of racial discrimination and parent and child well-being. 117 socioeconomically diverse Black families with young children with an average age of 36 years were surveyed: 46% were 200% below the federal poverty level (FPL) and 21% above the 400% FPL, 47% had a B.A. degree or higher, and 75% were in two-parent households. Exploratory factor analyses, correlation, and regression analyses were conducted. Results revealed and confirmed five factors: knowledge and access to resources, supportive network and optimism for challenges, culturally sustaining traditions and practices, spiritual promoting practices, and diverse communication and connection channels. While some differences were found based on income and parental education, there were no differences by family structure. Validation analyses indicated that family cultural wealth was associated with parental experiences of discrimination and parent emotional distress but not child behavioral problems. These findings suggest that the FCWS has adequate psychometrics, making it a potential tool for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers as they ensure that programs and strategies leverage the assets of racially marginalized families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies and reports often point to the educational, health, wealth, and social disparities experienced by Black families compared to White families, primarily due to structural racism that creates systemic inequities that hinder development and functioning (Graham, 2018; Iruka et al., 2021). Rightfully so, attention has focused on inequities that position one based on socially engineered constructs such as race, gender, and class, among many things. However, there is a need for a holistic examination of how families and communities are functioning under oppressive and dehumanizing conditions. That is, there is a need to ascertain the practices and strategies that Black families activate to cope with these inequitable experiences. Unfortunately, very few survey instruments have been developed to measure how cultural assets support families’ lives and functioning, especially families with young children, during a critical development period (NASEM, 2019). Historically and currently, quantitative methods have been used to uphold systemic inequities, but they lack the ability to create a complete understanding of lived experiences like qualitative methods (Sablan, 2018). Yet, it is critical to decolonize these methodologies to use quantitative methods and statistics in equity-centered research with a strengths-based lens. This study aims to empirically validate a family cultural wealth survey with a socioeconomically diverse Black sample by conducting exploratory factor analysis and examining whether there are differences by socio-demographics within Black families with young children.

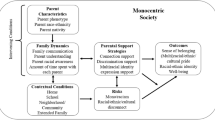

Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in the work of critical race scholars such as Dr. Robert Hill and his 1972 book entitled The Strengths of Black Families and Yosso’s (2005) model of community cultural wealth. In his work, Hill (1972) seeks to move away from and beyond the predominant and deficit perspective of weakness and pathology of Black families, as was done by the Moynihan Report in 1965. Instead, Hill (1972) uplifts the resilience and assets of Black families seeking to survive and thrive when examined through a context of White supremacy, dehumanization, and oppression. Hill (1972) identifies five strengths of Black families: strong kinship bonds, strong work orientation, adaptability of family roles, high achievement orientation, and religious orientation.

The study of Black families through a strengths-based perspective has continued through many scholars since the mid-to-late twentieth century until presently, from Clark (1983), McAdoo (2007), McLoyd (1990), Littlejohn-Blake and Darling (1993), and many others, to, more recently, Hill and colleagues (2023). These Black scholars continue to emphasize the countless strengths, visible and invisible, of Black families, whether in structures considered to be traditional families or non-traditional families, such as blended families or older couples. In their elevation of foundational research from Black scholars, Hill and colleagues (2023) call attention to several areas of family study from family dynamics (e.g., extended family support) and racial socialization and identity to risk and resilience (e.g., religiosity, optimism, resistance) that align with the cultural assets of Black families.

Further extending this cultural asset framework and applying the lens of critical race theory, Yosso (2005) sought to move beyond the White, middle-class traditional idea of assets as only based on the accumulation of economic and material resources (e.g., savings, real estate, business ownership, stocks) but rather “Centering the research lens on the experiences of People of Color in critical historical context reveals accumulated assets and resources in the histories and lives of Communities of Color” (p. 77). Through this reconceptualization of asset and capital that unpacks the social and psychological skills of communities of color, Yosso identified six forms of capital: (1) aspirational: the ability to maintain hopes and dreams even in the face of barriers; (2) linguistic: the skills attained through various experiences to communicate in more than one language or style; (3) familial: the cultural knowledge nurtured among kin and extended families, living or transitioned, that hold the history, memory, and cultural intuition (e.g., consciousness); (4) social: the networks of people who provide instrumental and social support to help one navigate through society’s formal and informal institutions and expectations; (5) navigational: the skills of maneuvering through institutions and spaces not made for racially and ethnically minoritized people (e.g., Black, Latine, Indigenous); and (6) resistant: the knowledge and skills that challenges inequality and its subjugation to inhumane and brutal treatment and limited opportunities.

Given these asset-based frameworks, this study provides an opportunity to examine the strengths of families of color, especially Black families, as they navigate adversities, including multiple forms of racism that have a detrimental impact on child and family development over the life course (Gee et al., 2019; Iruka et al., 2022b). As called on by Hill and colleagues (2023), the research on Black families must be “more holistic,” considering theoretical foundations, methodology, conceptualization, and measurement (p. 172). Uncovering these cultural assets could reveal a critical strategy and approach to more effectively support Black children and their families’ economic, health, and social well-being.

Family Cultural Assets Presence in Black Lives

The underlying framework of Yosso’s community cultural wealth is based on the notion that communities of color, who have endured histories of oppression, dehumanization, and contemporary inequities and barriers, find ways to survive and thrive. Thus, it is expected that Black families are likely to develop these cultural assets. While current research has pointed to some indication that certain cultural assets may be more salient for some groups than others, there is no empirical evidence. For example, given the role of the church in social activism and the fight for civil rights for Black people (Barnes, 2005), it is expected that spirituality may be activated more often for Black families than White families. Extant research has shown racial differences in Black adults’ centrality of church and spirituality in their lives compared to White and Asian adults (Pew Research Center, n.d.).

Similarly, home language plays a critical part in families’ connection to their culture and heritage, with some scholars estimating that nearly 80% of African Americans in the USA have spoken African American English (AAE) at some point in their lives (Joiner, 1981). AAE is a major dialect of American English. Dialects are derived from a primary language, spoken by specific groups and communities in specific regions, and present in every country in the world. It is expected that language capital may be more salient as a tool to address social and economic exclusion and discrimination and community connection, though this may differ based on country of origin and generational status (Cano et al., 2021).

Current Evidence Linking Cultural Assets to Children and Families’ Well-being

Structural barriers, namely, racism, can keep marginalized families from easily maneuvering through systems that have unwritten rules and require prior connections to be successful (NASEM, 2023). Though barriers exist, minoritized families remain optimistic and hold on to hope for a more equitable future (Graham, 2018). A recent report found that poor Black Americans are more optimistic than poor White Americans, even given the systemic oppression and racism experienced (Graham, 2018). Research consistently highlights that some communities that are often excluded from systems, such as healthcare, have developed ways to cultivate health-relevant cultural resources or cultural health capital to navigate the existing healthcare system and maintain the health of the community members (Madden, 2015). For example, Josiah Willock et al. (2015) used a learning circle approach to train community health workers (CHWs) in heart health education due to the disproportionality of heart disease mortality experienced by Black women. They found this training to increase the knowledge, practices, and reach of CHWs.

Likewise, spiritual capital is often used as a social or psychological instrument to navigate barriers and challenges among racially and ethnically minoritized groups. Spirituality is often used as an umbrella term to encompass those either aligned with a more structured religion or drawn to a loosely defined connection to a higher power (Park et al., 2019). In the Pew Research Center Religious Landscape Study, they found that Black adults (75%) are more likely to report religion being “very important” to their life compared to 59% of Latine, 36% of Asian, and 49% of White adults (Pew Research Center, n.d.). Similarly, Black adults were more likely to attend a religious service than Latine (39%), White (24%), and Asian (26%) adults. Considering the role that churches and religious leaders played in activism, including the civil rights movement, spiritual capital can also serve as a tool for activism and resistance (Pattillo-McCoy, 1998), as well as a place for social, emotional, and instrumental support. In a Gallup study of 1863 interviews with pastors and church leaders, Barnes (2005) found that gospel music and prayers, cultural symbols, were positively linked to community action (e.g., food pantry, prison/jail ministry, youth programs, social issue advocacy). Thus, the church or other spiritual settings can be multipurpose, providing a place for worship, connection, community building, political activism, and resource sharing in many communities (Brewer & Williams, 2019; Taylor et al., 2000).

Culture is fostered through rich and varied communication within groups. For example, many minoritized groups create ways to communicate with each other, which may include languages such as Spanish, French, or AAE. AAE demonstrates the vibrant and ever-changing language used by many in the Black and African Diaspora (Jones, 2015; Smitherman, 2021). In addition to verbal communication, various minoritized groups have unique nonverbal forms of communication taught within groups, including but not limited to body language, tone of voice, and gestures (Cooke, 1972; Denton et al., 2020). These diverse communication styles also historically served as strategies to protect Black families from being harmed, tortured, and, at worst, lynched by enslavers. Most families have oral traditions that they have passed down to them from earlier generations, and many also create new traditions that are unique to their family (Holmes, 2019).

A strong support network is also vital for both parent and child well-being (Armstrong et al., 2005; McConnell et al., 2011). Social support is linked to decreased stress and improved psychological well-being (Black et al., 2005; Michael et al., 2008). A strong support network has been shown to reduce parental stress, which benefits their children’s outcomes (Parkes et al., 2015; Raikes and Thompson, 2005). In the USA, poverty and financial well-being are dynamic factors impacting the health and functioning of parents and children (Duncan et al., 2011; Hamad & Rehkopf, 2016). Studies have found that poverty impacts parental mental health and parenting behaviors (Duncan et al., 2011). In addition, a study found that wealth impacts academic and behavioral development throughout various stages of childhood (Miller et al., 2021). Therefore, financial support effects not only the short-term health and well-being of parents and children but also has potential long-lasting impacts throughout life.

Additionally, as technology continues to become ingrained in our lives, social media has been a place for people to grow and maintain connections. When parents welcome children into their lives, they may experience shifts in their relationships with others (Bost et al., 2002; Toombs et al., 2018). During the transition to parenthood, some adults experience higher levels of isolation and loneliness (Nowland et al., 2021), while other new parents have been found to develop new relationships or grow within their existing friendships (Curry et al., 2016). Various studies have explored how social media can facilitate connection and a support network for parents of young children (Baker & Yang, 2018). For example, Baker and Yang (2018) found in their survey of new mothers in the postpartum setting of an academic medical center that while new moms’ primary source of support was their partners, other social media sources were also noted: 43% used blogs to communicate with other mothers, 99% used the internet for answers to parenting questions, and 89% used social media sites for questions and advice related to pregnancy and/or their role as a parent. Furthermore, over 80% of new moms considered social media friends a form of social support.

Current Study

While these studies provide evidence of the diverse types and ways that families and communities activate their cultural assets to address barriers and inequities, many of the studies are primarily qualitative, including case studies and ethnographic work. While these qualitative methods are critical to provide insights into how these cultural assets are activated, interrelated, and dynamic, they do not provide a tool to systematically capture family cultural assets across many people. The lack of a valid tool potentially limits how programs and policies can improve to leverage and integrate the strengths of families rather than see them through a lens of neediness and pathology.

This study seeks to add to the growing literature on cultural assets. This study aimed to test the factor structure of the Family Cultural Wealth Survey (FCWS) in Black families with young children by (1) exploring how many factors are present in the survey through exploratory factor analysis (EFA); (2) examining differences by income, family structure, and parental education; and (3) exploring associations between the FCWS factors and experiences with discrimination and parental and child well-being.

Method

Procedures

Data for the current study were drawn from the Rapid Assessment of Pandemic Impact on Development–Early Childhood (RAPID-EC) project. RAPID-EC is a national study that uses ongoing weekly to monthly surveys to assess the influence of the pandemic on households with young children (0–5 years old). All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Stanford University.

Participants were recruited through community organization email listservs, Facebook Ads, and panel services. Interested families first completed an online survey to determine their eligibility. Eligible families then provided online consent to participate in the study. They completed a baseline survey that included core modules such as demographics, employment and financial strain, health and well-being, and childcare accessibility. After finishing the baseline survey, families were enrolled into a participant pool and invited by email to complete follow-up surveys, including baseline core modules and special topics. Each family received $5 as an incentive for every survey they completed. As part of the RAPID-EC data collection from June to September 2022, the FCWS was included.

Study Participants

One hundred and seventeen Black families with young children completed the FCWS. Forty-six percent of respondents were below 200% Federal Poverty Level (FPL),Footnote 1 which equates to about $62,400 for a family of four in 2024, 33% were between 200 and 400% FPL (or between $62,400 and $124,800 for a family of four in 2024), and 21% were above 400% FPL. Most respondents were female (95%), aged 18 to 63 years old (mean = 35.75 years, SD = 5.91). Among these 117 Black households, slightly less than half (47.01%, n = 55) of parents indicated having an education level at or above a Bachelor’s degree. One in four (24.14%, n = 28) of these families were single-parent households.

Measures

Family Cultural Wealth Survey (FCWS; Iruka et al., 2022a, 2022b). FCWS items were generated based on the literature on family and community cultural strengths that attended to these areas of cultural capital: aspirational, linguistic, familial, social, navigational, resistant, perseverant, and spiritual (see Table 1). Twenty-four items were generated and examined by a five-member research team consisting of Black, White, and Latine scholars with backgrounds in psychology, child development, social work, and public policy, who were already partnering on research and translation of factors that support Black families and young children’s early learning and development. Four leaders from community-based organizations focused on birth equity, community development and revitalization, and education equity who collaborated with the first author on a national initiative on Black families then reviewed the items, resulting in a few items’ wording being slightly revised.

The FCWS is a 24-item survey with a 5-point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater perceived activation of cultural wealth. The 24 items ask about aspirational capital (one item), three items on linguistic capital (e.g., “engage in different ways of communication with child”), two items on familial capital (e.g., “have family and cultural traditions and events”), six items on social capital (e.g., “have family, friends, and networks of people when need emotional, financial, and emergency support, and parental advice”), seven items on navigational capital (e.g., “knowledge to access resources on job training or employment, education, housing, housing”), two items on resistant capital (e.g., “engage in social media advocacy that support child and community”), one item on perseverant capital (e.g., “handle obstacles/challenges that get in the way of life, work, parenting”), and two items on spiritual capital (e.g., “rely on spiritual guidance to help with challenges/difficulties”).

Parental Experiences of Discrimination. This 12-item caregiver/parent-rated report was adapted from Williams et al.’s (2008) Major Experiences of Discrimination Scale. This scale was chosen because it was one of the most widely used measures of self-reported discrimination. It has been shown to have high internal consistency and significant correlations with perceived everyday discrimination (Williams et al., 2008). The Major Experiences of Discrimination Scale assessed parents’ experiences of unfair treatment in employment, education, housing, and interactions with police. In addition to including the stem “because of your race or ethnicity,” we also adapted the measure to include new items focused on being denied service, medical service, or being called a derogatory name or slur. Respondents respond to the items using a 2-point Likert scale (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Psychometric analyses indicate that compared to White, Asian, and Latine respondents, Black respondents were more likely to endorse the items and that items were moderately correlated, ranging from 0.14 to 0.47. Analyses for this paper were based on a total number of discriminatory items reported by parents. In the current sample, this scale had high internal consistency (α = 0.86).

Parent and Child Well-being. Measures of parent and child well-being were chosen in the large RAPID-EC study context, which was initially designed in response to the pandemic emergency to rapidly obtain information from families with young children using brief and frequent online surveys. Given the nature of the RAPID-EC study, shortened or trimmed measures were used in parent and child well-being assessments to reduce survey length and avoid participants’ fatigue. More details about these measures are provided in other RAPID-EC papers (e.g., Ibekwe-Okafor et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022; Zalewski et al., 2023).

Parent well-being was based on caregivers’ reports on whether they experienced any emotional distress from depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness symptoms, which were measured via the Patient Health Questionnaire 2-item Scale (PHQ-2; Löwe et al., 2005), the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 2-item Scale (GAD-2; Kroenke et al., 2007), a one-item measure on stress (Elo et al., 2003), and a one-item loneliness measure from the NIH Toolbox item bank version 2.0 (Gershon et al., 2013). Responses to PHQ-2 and GAD-2 both ranged from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), and mean scores of the two items in each scale were calculated as depression and anxiety symptom scores. For the stress item, responses ranged from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). For the loneliness item, responses ranged from 0 (never) to 4 (always). These four symptoms were moderately to strongly correlated with each other (r ranged from 0.47 to 0.79, p < 0.001) and had high internal consistency (α = 0.87) in the current sample. Emotional distress composite score was calculated as the average of the four symptoms’ scores, which were first transformed to a range of 0–100.

Child well-being was based on items asking parents about whether their children showed behavioral problems regarding their fussiness or defiance and fear or anxiety using two symptoms selected from the Child Behavioral Checklist (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001); parents were asked to “select the answer which best fits [their] child’s behavior in the last week: fussy or defiant,” and “too fearful or anxious.” These two items were used to obtain a proxy assessment of child externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and they were chosen because they applied appropriately to children under 6 years old. Possible responses included 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat/ sometimes true), and 2 (often/very true). These two items were moderately correlated (r = 48, p < 0.001) and had acceptable internal consistency (Spearman-Brown reliability = 0.65). Mean scores of these two items were calculated and transformed to a range of 0–100 to represent children’s overall behavioral problems.

Data Analyses

We first examined bivariate correlations (Pearson’s r) between the FCWS items among our Black participants. Next, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to explore the nature of the dimensions of the latent variable (cultural wealth) and how the scale relates to the dimensions. An EFA determines how many dimensions of a phenomenon are represented by scale items (Knekta, Runyon, & Eddy, 2019). Additionally, with an EFA, questions are allowed to load on every factor and be freely estimated. The FCWS items were treated as ordinal data in EFA, and the extraction method choice used was weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) considering the ordinal variable nature. To determine the number of factors within the measure, we relied on a combination of multiple approaches, including (1) the rule of eigenvalues greater than one, (2) comparing model fit indices of different factor solutions, (3) parallel analysis (Zwick & Velicer, 1982), and (4) Very Simple Structure (VSS) criterion (Revelle & Rocklin, 1979). When the suggestions from these approaches do not agree with each other, we extracted all potential solutions and compared their theoretical appropriateness to decide on the final number of factors. The rotational method of Promax oblique rotation was used because it is less restrictive as it allows factors to be correlated and is generally used in scale development (Costello & Osborne, 2005).

After the EFA, the mean score of each factor was calculated by taking the average of comprising items. Independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine the mean-level differences of identified factors by household income levels (below or at/above 200% FPL), family structure (dual vs. non-dual parent households), and parent education levels (below vs. at/above a bachelor’s degree). Correlation analyses of these mean factor scores with other relevant variables, including parents’ experiences of racism/discrimination, parents’ emotional distress, and children’s behavioral problems, were conducted as well. Among all the analyses described above, EFA was conducted in Mplus version 8.3, and all the other analyses were conducted in RStudio.

Results

Preliminary Results

Mean scores were calculated for each item (see Fig. 1). Descriptive statistics showed that across the sample, families were likely to endorse items focused on linguistic capital (e.g., encourage child to express themselves [M = 4.50], engage in different ways of communication [M = 4.22]) and having knowledge to access resources in job training and employment assistance (M = 4.11) and educational assistance (M = 4.10). Parents were less likely to agree that they participate in church/faith-based events (M = 2.95), have a support network for financial support (M = 3.29), and engage in advocacy that supports children and the community (M = 3.41).

Bivariate Correlations

Next, item-level bivariate correlations were conducted among the sample of Black parents (see Fig. 2). Results indicated that items for each type of capital were moderately correlated. For example, the two spiritual items were highly correlated (r = 0.68), the correlation for items on network support for emotional support, financial support, emergency help, and parental advice ranged from 0.55 to 0.71, and items measuring parents’ knowledge and confidence to access resources for job training or employment assistance, education assistance, housing parenting services, mental health services, child care support, and safety net programs (WIC, SNAP, Medicaid) ranged from 0.39 to 0.67.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Selecting the Number of Factors. An ordinal exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to determine if the FCWS items were indicated by more than one factor. We used the WLSMV estimator and Promax oblique rotation to extract factors, and solutions of one to eight factors were extracted for comparison. A combination of multiple approaches, including eigenvalues, model fit indices, parallel analysis, and the VSS criterion, were used to determine the optimal number of factors. First, the scree plot (Fig. 3) suggested a six-factor solution where the eigenvalues stayed above one. Second, model fit comparisons of different factor solutions (Table 2) showed significant fit improvement, as indicated by better-fit indices and significant chi-square difference tests, up until the seven-factor solution. Third, the parallel analysis suggested a five-factor solution. Lastly, analysis of the VSS criterion indicated a five-factor solution, where the VSS complexity 2 achieved a maximum value of 0.63. Given these results, we compared the factor loadings of the five- and six-factor solutions. As the six-factor solution showed signs of overextraction, we decided the five-factor solution to be the most parsimonious and final model.

Five-Factor EFA Solution Among Black Participants. Table 3 presents the factors and associated Cronbach’s alpha for the sample loadings of the five-factor solution in EFA. The first factor contains questions about having knowledge and confidence to access various resources and includes seven questions (CW 13–19) with all items having high factor loadings (λ > 0.60). The Cronbach’s alpha for the first factor is 0.86, indicating very good internal consistency within this factor. The second factor pertains to “supportive network and optimism for challenges” and includes seven questions, with high factor loadings for six items (λ > 0.60; CW 7–10, CW 21–22) and acceptable loading for one item (λ = 0.44, CW 1). The Cronbach’s alpha for the second factor is 0.85, indicating good internal consistency within this factor. The third factor pertains to “culturally sustaining traditions and practices” and contains five questions, with high factor loadings for four items (λ > 0.70; CW 2, 4–6) and acceptable loading for one item (λ = 0.47, CW 20). The Cronbach’s alpha for the third factor is 0.76, indicating acceptable internal consistency within this factor. The fourth factor pertains to religious and “spiritual promoting practices” and contains two questions (CW 23–24) with very high factor loadings (λ > 0.80). The Cronbach’s alpha for the fourth factor is 0.81, indicating good internal consistency within this factor. The fifth factor discusses “diverse communication and connection channels” and contains three questions (CW 3, 11, 12), with two questions (CW11, 12) having high factor loadings (λ > 0.70). However, question 3 had poor loadings on all five factors; despite its highest loading on the fifth factor, it was still suboptimal (λ = 0.23). The Cronbach’s alpha for the fifth factor is 0.51, indicating poor internal consistency within this factor. However, when item CW3 was dropped, Cronbach’s alpha improved to an acceptable level (α = 0.71).

Table 4 presents the correlation coefficients of the five latent factors as confirmed in EFA. Accordingly, factors were strongly correlated among factor 1 (having knowledge and access to resources), factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges), and factor 3 (culturally sustaining traditions and practices), r > 0.50, p < 0.001. Factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges) and Factor 5 (diverse communication and connection channels) were also strongly correlated with each other, r = 0.53, p < 0.001. Moderate levels of correlations were found between factor 4 (spiritual promoting practices) and factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges; r = 0.31, p < 0.01), between factor 4 (spiritual promoting practices) and factor 3 (culturally sustaining traditions and practices; r = 0.37, p < 0.001), and between factor 5 (diverse communication and connection channels) and factor 1 (having knowledge and access to resources; r = 0.41, p < 0.001). In addition, a weak but significant correlation was found between factor 4 (spiritual promoting practices) and factor 5 (diverse communication and connection channels), r = 0.28, p < 0.05. Factors 1 (having knowledge and access to resources) and 4 (spiritual promoting practices) were not significantly correlated with each other, r = 0.15, p = 0.13.

Mean FCWS Factor Scores and Socio-demographic Comparisons

The mean factor scores were calculated by taking the average of items loaded onto each of these five factors, as identified in the EFA. The mean scores for each of the six factors within the sample are as follows: factor 3 (culturally sustaining traditions and practices; mean = 4.00, SD = 0.71), factor 1 (having knowledge and access to resources; mean = 3.91, SD = 0.75), factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges; mean = 3.79, SD = 0.80), factor 5 (diverse communication and connection channels; mean = 3.72, SD = 0.80), and factor 4 (spiritual promoting practices; mean = 3.26, SD = 1.28).

Table 5 presents the mean-level comparisons of these five factors by household income, parent education, and family structure among Black participants. Accordingly, Black families with middle-to-higher income levels (at or above 200% FPL) reported significantly higher levels in factor 1 (having knowledge and access to resources; t [114] = 2.66, p < 0.01) and factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges; t [115] = 3.94, p < 0.001) than households of lower income levels below 200% FPL. Parents with a bachelor’s degree or higher indicated significantly higher levels in factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges; t [115] = 2.56, p < 0.05) but significantly lower levels in factor 5 (diverse communication and connection channels; t [115] = -2.39, p < 0.05), compared to parents with lower educational attainment. These factors mean scores did not significantly vary by family structure.

Association Between FCWS and Parents’ Experiences of Discrimination and Parent and Child Well-being

Correlation analyses indicated an association between factors mean scores of the FCWS and parents’ experiences of discrimination, ranging from − 0.27 to 0.09 (see Table 6). Specifically, factor 2: supportive network and optimism for challenges (r = − 0.27, p < 0.001) was negatively associated with parental experiences with discrimination, suggesting that the more parents report having a supportive network and optimism when facing challenges, the less likely they reported experiencing discrimination. In addition, FCWS factor 1 (having knowledge and access to resources; r = − 0.29, p < 0.01), factor 2 (supportive network and optimism for challenges; r = -0.43, p < 0.001), and factor 3 (culturally sustaining traditions and practices; r = − 0.21, p < 0.01) were associated with Black parents’ lower levels of emotional distress, indicating the more knowledge and access to resources, supportive networks, and engagement in cultural practices and traditions were associated with parents report of less loneliness, stress, and depression. However, no factor was directly and significantly associated with parent-reported behavioral outcomes among their young children.

Discussion

Overall, we aimed to understand the factor structure of the Family Cultural Wealth Survey (FCWS) by investigating the number of factors present in the survey using an EFA with a socioeconomically diverse sample of Black families with young children. In addition to examining whether the factors varied by family characteristics, we examined the tool’s validity by exploring its association with parental experiences of racial discrimination and parent and child well-being. The findings support a five-factor solution for the FCWS with Black families. The results of the EFA show that the Family Cultural Wealth Survey provides a reliable and valid way to assess aspirational, familial, navigational, perseverant, and spiritual capital could have reliability and validity, consistent with previous studies on assessing community cultural wealth (e.g., Sablan, 2018). Findings from this study demonstrate how Black families uniquely activate cultural wealth. A five-factor structure proved to be the best fit for Black participants. The retained factors include knowledge and access to resources, supportive network and optimism for challenges, culturally sustaining traditions and practices, spiritual promoting practices, and diverse communication and connection channels.

Cultural Wealth Factors Placed in Sociocultural Context

The emerging factors align with Black families’ sociocultural history and contexts. The findings indicate that Black families have the “know-how” to access various resources. Given the history of Black people being excluded from accessing and using wealth-promoting programs such as the G.I. Bill and housing and business loans, it is not surprising that Black families will likely have the knowledge to access various economic and social resources. For instance, studies show that Black families are more likely to receive child care subsidies (e.g., Ullrich et al., 2019), housing support (e.g., Solari et al., 2021), and WIC (e.g., Liu & Liu, 2016) compared to White families. However, significant concerns exist about the quality of these services and supports. Given the challenge noted by low-income families about administrative burden in accessing services (Herd & Moynihan, 2023; Johnson & Kroll), it is not surprising that middle-to-higher income Black families were likely to report having the knowledge and being able to access resources. Furthermore, studies indicate that higher-income Black families are likely to have more networks compared to low-income Black families and, thus, are more likely to tap into more information and resources; however, their advantages were not always as large as expected (Parks-Yancy et al., 2009; Thomas, 2015). Prior studies and the current study indicate that even with a higher level of education (i.e., have a bachelor’s degree or higher), almost half of Black families were living in low-income, underscoring that more education does not confer the same economic benefits (Hamilton & Darity, 2017; Meschede et al., 2017).

Similarly, the finding that items focused on persevering in the face of challenges loaded with having support networks for Black families indicates the interrelated nature of aspirational and social capital. Considering the pernicious impact of racism and discrimination in the lives of Black families, historically and contemporarily, it is not surprising the importance of networks being instrumental in being able to cope with various challenges. There is a long history of relying on networks to manage vicarious racism in the Black community. In their three-process model of Critical Consciousness of Anti-Black Racism, Mosley et al. (2021) found through their nonconfidential interviews with 12 Black Lives Matter activists that social networks were critical in fighting against anti-Black racism. Social networks ensured “… ‘many hands, light work’… “many hands… lightened [activists’] load and resourced their activism work” (Mosley et al., 2021, p. 11). In this study, higher income and educated Black parents were likely to report more supportive networks and optimism compared to lower income and less formally educated Black parents. This finding is not surprising, given that higher-income and educated Black parents may have more economic stability and networks than those from lower-income households, giving them a stronger sense of comfort.

Black families were likely to activate particular cultural wealth, especially in culturally sustaining traditions and practices and spiritual promoting practices. In their examination of art participation, DiMaggio and Ostower (1990) found that even after controlling for social class, Black people were more likely to attend jazz concerts and enjoy “soul, blues, or rhythm-and-blues music, the other historically Afro-American musical forms” (DiMaggio & Ostower, 1990, p. 758). Similarly, an urban institute study on cultural participation also found that Black people overwhelmingly engaged in cultural events to learn about or celebrate their cultural heritage compared to Hispanics and Whites (49% vs. 29% and 10%, respectively) (Ostrower, 2005). Likewise, the factor on spiritual promoting practices confirms the importance of this cultural wealth for Black families, confirming the extant literature that Black families are more likely to engage in informal and organized religion than White families (e.g., Chatters et al., 2009). Pew Research Center also found that “most Black Americans identify as Christian, and many are highly religious by traditional measures of belief…the vast majority of whom say they believe in God or a higher power (97%)” (Mohamed et al., 2021, p.1). Skarupski and colleagues (2013) found that while Black Americans were likely to have lower life satisfaction compared to other racial groups, spiritual experiences were found to increase life satisfaction for Black families.

The factor on diverse communication and connection channels is consistent with the history of Black communities’ use of culturally grounded communication, such as flexible use of language (e.g., AAE) and diverse communication channels to advocate for change and justice (e.g., Black Twitter) (Gilyard & Banks, 2018). In their paper about “emerging digital racial literacies and their relationship to a long history of anti-Black information warfare” in reviewing Twitter (now known as X) and other platforms, Lockett (2021) connects language and social media. Specifically stating, “Similar to offline, race must be made visible online through various acts of language. Demonstrating blackness relies on both Black English (BE), or African American Vernacular English (AAVE), and a myriad of speech acts that constitute BE. This insider knowledge empowers r/BlackPeopleTwitter and online Black feminists to detect fake accounts and posts that spread disinformation campaigns” (p. 200). This shows how linguistic, resistant, and social capital plays out in Black people’s approach to telling the truth about their lived experiences and how racism and bias operate seamlessly in society, showcasing their multiple intelligences and cultures, and use of different channels to find and share collective justice, humor, and joy.

In this study, Black parents with less than a B.A. degree were likely to use diverse communication styles and communication. This finding is consistent with scholars who find that children in low-income households are more likely to speak AAE than their higher-income peers (Washington & Craig, 1998). Furthermore, work by Rahman (2008) finds that Black middle-class individuals are conflicted in their use of AAE and its impact on their access to opportunities while being concerned about maintaining their racial identity. “Still, while all of the participants value and appreciate BSE [Black Standard English],Footnote 2 they sometimes express a concern that freely employing features of AAE in mainstream environments, such as the broader university community, may serve to reinforce negative beliefs” (Rahman, 2008, p. 170).

Regarding social media, Pew research finds that Black families and less educated individuals are less likely to use social media or networking sites compared to White and more educated individuals (Perrin, 2015). However, in this study, less educated families were likely to report using more social channels than more educated families, which may indicate Black families living in low-income families are likely to see social media as a way to expand their access and connections (Mundt et al., 2018). Future studies are needed to examine how and why socioeconomically diverse Black families use social networking sites.

Concurrent Validation Linking Family Cultural Wealth and Experiences of Discrimination and Parent and Child Well-being

Validation analyses also indicate that family cultural wealth was associated with parental experiences of discrimination, as well as their own emotional distress. Having a supportive network and optimism during adversities were associated with lower reports of racial discrimination. While this study does not allow us to tease out directionality, it does provide validity of the FCWS measure by being able to distinguish the nuanced relationships between the different forms of cultural wealth and racialized experiences. As noted earlier, studies indicate that Black families, for example, often call on higher power and remain hopeful when experiencing racism as a form of coping (Holder et al., 2015). Similarly, supportive networks have also been linked as a strategy racial minorities activate to cope with living in oppressive contexts (Hudson et al., 2016; Volpe et al., 2021). While preliminary analyses indicated that the relationship between having supportive networks and optimism in the face of challenges and experiences with discrimination were salient for Black families, there is a need for a larger sample collected over time to understand the direct and the interrelationships of these variables over time.

Family cultural wealth was also negatively linked to parental emotional well-being but not parent-reported child behavior. While we do not know the directionality, some studies indicate that family cultural wealth, including their familial, social, and cultural connections, buffer them from mental health challenges. For instance, studies have found that access to supportive networks and cultural ties are linked to adult well-being and reduction in emotional distress (Hovey & Magaña, 2002; Segrin & Passalacqua, 2010; Siedlecki et al., 2014). It could also be that those with more adaptive emotional capacities are likely to activate their cultural wealth, including cultivating supportive networks, having more resources to have an optimistic mindset, and engaging in cultural traditions and events (Branje et al., 2004).

There was no indication that Black families’ cultural wealth was associated with parent-reported child behavior, specifically internalizing and externalizing problems. The lack of findings on children’s problem behavior may indicate several things. First, Black parents are less likely to report their children as having problem behaviors in light of a racialized context that often views Black children as problematic and aggressive, not deserving of safety, care, and love (Olson et al., 2018; Zimmerman et al., 1995). Second, it could be a measurement error as only two items were used to measure complex constructs of externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. Most studies use a robust measure such as the Child Behavior Check List (Achenbach, 1991; Konold et al., 2003). A focus on prosocial competencies may matter more for Black children. Finally, the FCWS items may be more salient for adult well-being than child well-being, calling for future studies examining whether cultural wealth is linked to child outcomes through parental well-being.

Limitations. While this study has many strengths, one must consider its limitations. A limitation of this study was the small sample size, which limits the generalizability and may make it difficult to detect small effects. Thus, caution must be taken when interpreting these findings. Further, there is heterogeneity within those who identify as Black Americans based on income, education, and family structure. Future analysis, which gathers information about distinct groups within the Black diaspora (e.g., Afro-Caribbean, Afro-Latino, Black immigrants) and geographic locations (e.g., rural vs urban, region of country), may provide a deeper understanding of cultural wealth within Black diasporic groups across varied contexts. The diverse communication and connection channels factor had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.51, which is below the acceptable level, so caution should be taken in interpreting findings associated with this factor. Finally, much of this study is based on parental reports (i.e., shared source variance), requiring future studies to gather data through a multi-method with multi-informants, including attending to more robust measures of child outcomes.

Conclusion

Even with these limitations, this study has many strengths. The FCWS is the first measure to examine family cultural wealth within socioeconomically diverse Black families. Many studies focused on community cultural wealth have focused on one aspect or used qualitative approaches (e.g., case studies, interviews). The five factors present within the FCWS provide a tool for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to consider using as they ensure their programs and strategies leverage Black families’ assets. The associations between family cultural wealth and parental experiences with discrimination and parental well-being provide strong evidence that this survey has adequate psychometrics, making this survey a potential new tool to capture the strengths and assets of Black families with young children. This study also adds to the evidence of the resilience and resistance of Black families to thrive through activating their cultural assets even while impacted by inequitable access to economic, social, and educational opportunities.

More research is needed to better understand the mechanism linking family cultural wealth and parental and child well-being above and beyond socio-demographic factors, such as family income and education. While the central goal of this measure was to fully center the Black families with young children whose perspectives and lived experiences have historically and contemporarily not been used to develop research tools, future studies can use this tool to examine whether the identified factors are salient and equivalent across other racial and ethnic groups.

Notes

Federal poverty levels indicate the minimum amount of annual income that an individual/family needs to pay for essentials, such as housing, utilities, clothing, food, and transportation.

Black Standard English (BSE) “…conforms to the grammatical norms of SE [Standard English] while containing features that enhance African American ethnicity and identity, carries equal prestige in the mainstream and in the African American community” (Rahman, 2008, p. 144).

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and the 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry.

Achenbach, T., & Rescorla, L. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families.

Armstrong, M. I., Birnie-Lefcovitch, S., & Ungar, M. T. (2005). Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(2), 269–281.

Baker, B., & Yang, I. (2018). Social media as social support in pregnancy and the postpartum. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 17, 31–34.

Barnes, S. (2005). Black church culture and community action. Social Forces, 84, 967–994.

Black, A. R., Cook, J. L., Murry, V. M., & Cutrona, C. E. (2005). Ties that bind: Implications of social support for rural, partnered African American women’s health functioning. Women’s Health Issues, 15(5), 216–223.

Bost, K. K., Cox, M. J., Burchinal, M. R., & Payne, C. (2002). Structural and supportive changes in couples’ family and friendship networks across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 517–531.

Branje, S. J. T., van Lieshout, C. F. M., & van Aken, M. A. G. (2004). Relations between big five personality characteristics and perceived support in adolescents’ families. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 615–628.

Brewer, L. C., & Williams, D. R. (2019). We’ve come this far by faith: The role of the Black church in public health. American Journal of Public Health, 109(3), 385.

Cano, M., Perez Portillo, A. G., Figuereo, V., Rahman, A., Reyes-Martínez, J., Rosales, R., Ángel Cano, M., Salas-Wright, C. P., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2021). Experiences of ethnic discrimination among US Hispanics: Intersections of language, heritage, and discrimination setting. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 84, 233–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2021.08.006

Chatters, L. M., Taylor, R. J., Bullard, K. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2009). Race and ethnic differences in religious involvement: African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Non-Hispanic Whites. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 32(7), 1143–1163. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870802334531

Clark, R. (1983). Family life and school achievement: Why poor black children succeed or fail. University of Chicago Press.

Cooke, B. (1972). Nonverbal communication among Afro-Americans: An initial classification. In T. Kochman (Ed.), Rappin’ and stylin’ out: Communication in urban Black America (pp. 32–64). University of Illinois Press.

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 10(1), 7.

Curry, K. A., Jean-Marie, G., & Adams, C. M. (2016). Social networks and parent motivational beliefs: Evidence from an urban school district. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(5), 841–877.

Denton, M., Borrego, M., & Boklage, A. (2020). Community cultural wealth in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics education: A systematic review. Journal of English Education, 109, 556–580. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20322

DiMaggio, P., & Ostrower, F. (1990). Participation in the Arts by Black and White Americans. Social Forces, 68(3), 753–778. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579352

Duncan, G., Magnuson, K., Kalil, A., & Ziol-Guest, K. (2011). The importance of early childhood poverty. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9867-9

Elo, A.-L., Leppänen, A., & Jahkola, A. (2003). Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29(6), 444–451. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40967322.

Gee, G. C., Hing, A., Mohammed, S., Tabor, D. C., & Williams, D. R. (2019). Racism and the life course: Taking time seriously. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S1), S43–S47. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2018.304766

Gershon, R. C., Wagster, M. V., Hendrie, H. C., Fox, N. A., Cook, K. F., & Nowinski, C. J. (2013). NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology, 80(11 Supplement 3), S2–S6. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e5f

Gilyard, K., & Banks, A. (2018). On African-American rhetoric. Routledge.

Graham, C. (2018). Why are Black poor Americans more optimistic than White ones? Brookings Institution.

Hamad, R., & Rehkopf, D. (2016). Poverty and child development: A longitudinal study of the impact of the earned income tax credit. American Journal of Epidemiology, 183(9), 775–784. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv317

Hamilton, D. & Darity, W.A. (2017). The political economy of education, financial literacy, and the racial wealth gap. Review, 99(1) 59–76. https://doi.org/10.20955/r.2017.59-76

Herd, P., & Moynihan, D. (2023). Fewer burdens but greater inequality? Reevaluating the safety net through the lens of administrative burden. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 706(1), 94–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162231198976

Hill, R. (1972). The strengths of Black families. Emerson Hall.

Hill, N. E., Pinderhughes, E. E., Hughes, D. L., Johnson, D., Murry, V. M., & Smith, E. P. (2023). African American family life: Rediscovering our foundation works. Research in Human Development, 20(3–4), 158–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427609.2024.2310453

Holder, A. M. B., Jackson, M. A., & Ponterotto, J. G. (2015). Racial microaggression experiences and coping strategies of Black women in corporate leadership. Qualitative Psychology, 2(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000024

Holmes, H. (2019). Material affinities: ‘Doing’ family through the practices of passing on. Sociology, 53(1), 174–191.

Hovey, J. D., & Magaña, C. G. (2002). Cognitive, affective, and physiological expressions of anxiety symptomatology among Mexican migrant farmworkers: Predictors and generational differences. Community Mental Health Journal, 38(3), 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015215723786

Hudson, D. L., Eaton, J., Lewis, P., Grant, P., Sewell, W., & Gilbert, K. (2016). “Racism?!? Just look at our neighborhoods”: Views on racial discrimination and coping among African American men in Saint Louis. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 24(2), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060826516641103

Ibekwe-Okafor, N., Sims, J., Liu, S., Curenton-Jolly, S., Iruka, I., Escayg, K. A., & Fisher, P. (2023). Examining the relationship between discrimination, access to material resources, and black children’s behavioral functioning during COVID-19. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 62, 335–346.

Iruka, I. U., Durden, T. R., Gardner-Neblett, N., Ibekwe-Okafor, N., Sansbury, A., & Telfer, N. A. (2021). Attending to the adversity of racism against young Black children. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/23727322211029313

Iruka, I. U., Forte, A., Curenton, S., & Sims, J. (2022a). Family cultural wealth survey. [Unpublished Measure] University of North Carolina at Chapel.

Iruka, I. U., Gardner-Neblett, N., Telfer, N. A., Ibekwe-Okafor, N., Curenton, S. M., Sims, J., Sansbury, A. B., & Neblett, E. W. (2022b). Effects of racism on child development: Advancing antiracist developmental science. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 4(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121020-031339

Joiner, B. L. (1981). Lurking variables: Some examples. The American Statistician, 35(4), 227–233.

Jones, T. (2015). Toward a description of African American Vernacular English dialect regions using “Black Twitter.” American Speech, 90(4), 403–440.

Josiah Willock, R., Mayberry, R. M., Yan, F., & Daniels, P. (2015). Peer training of community health workers to improve heart health among African American women. Health Promotion Practice, 16(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839914535775

Knetka, E., Runyon, C., & Eddy, S. (2019). One size doesn’t fit all: Using factor analysis to gather validity evidence when using surveys in your research. CBE Life Sciences Education. 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-04-0064

Konold, T. R., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2003). Measuring problem behaviors in young children. Behavioral Disorders, 28(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/019874290302800202

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325.

Littlejohn-Blake, S. M., & Darling, C. A. (1993). Understanding the strengths of African American families. Journal of Black Studies, 23(4), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193479302300402

Liu, S., Zalewski, M., Lengua, L., Gunnar, M. R., Giuliani, N., & Fisher, P. A. (2022). Material hardship level and unpredictability in relation to US households’ family interactions and emotional well-being: Insights from the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Science & Medicine, 307, 115173.

Liu, C. H., & Liu, H. H. (2016). Concerns and structural barriers associated with WIC participation among WIC-eligible women. Public Health Nursing, 33(5), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12259

Lockett, A. L., Ruiz, I. D., Chase Sanchez, J., & Carter, C. (2021). Race, Rhetoric, and Research Methods. The WAC Clearinghouse; University Press of Colorado. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2021.1206

Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., & Gräfe, K. (2005). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171.

Madden, E. (2015). Cultural health capital on the margins: Cultural resources for navigating healthcare in communities with limited access. Social Science & Medicine, 133, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.006

McAdoo, H. P. (Ed.). (2007). Black families. Sage.

McConnell, D., Breitkreuz, R., & Savage, A. (2011). From financial hardship to child difficulties: Main and moderating effects of perceived social support. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(5), 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01185.x

McLoyd, V. C. (1990). The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development, 61(2), 311–346. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131096McLoyd

Meschede, T. T., Taylor, J., Mann, A., & Shapiro, T. (2017). Family achievements? : How a college degree accumulates wealth for Whites and not for Blacks. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 99(1), 121–37.

Michael, Y. L., Farquhar, S. A., Wiggins, N., & Green, M. K. (2008). Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(3), 281–289.

Miller, P., Podvysotska, T., Betancur, L., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2021). Wealth and child development: Differences in associations by family income and developmental stage. Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 7(3), 154–174. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2021.7.3.07

Mohamed, B., Cox, K., Diaman, J., & Gecewicz (2021). Religious beliefs among Black Americans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/02/16/religious-beliefs-among-black-americans/. Accessed 10 June 2023.

Mosley, D. V., Hargons, C. N., Meiller, C., Angyal, B., Wheeler, P., Davis, C., & Stevens-Watkins, D. (2021). Critical consciousness of anti-Black racism: A practical model to prevent and resist racial trauma. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000430

Mundt, M., Ross, K., & Burnett, C. M. (2018). Scaling social movements through social media: The case of Black lives matter. Social Media + Society, 4(4), 2056305118807911. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118807911

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine (NASEM). (2023). Closing the opportunity gap for young children. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26743

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine (NASEM). (2019). Vibrant and healthy kids: Aligning science, practice, and policy to advance health equity. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25466

Nowland, R., Thomson, G., McNally, L., Smith, T., & Whittaker, K. (2021). Experiencing loneliness in parenthood: A scoping review. Perspectives in Public Health, 141(4), 214–225.

Olson, S. L., Davis-Kean, P., Chen, M., Lansford, J. E., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & Dodge, K. A. (2018). Mapping the growth of heterogeneous forms of externalizing problem behavior between early childhood and adolescence: A comparison of parent and teacher ratings. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(5), 935–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0407-9

Ostrower, F. (2005). The diversity of cultural participation: Findings from a national survey. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/51736/311251-The-Diversity-of-Cultural-Participation.PDF. Accessed 5 Jan 2022.

Park, J., Dizon, J., & Malcolm, M. (2019). Spiritual capital in communities of color: Religion and spirituality as sources of community cultural wealth. The Urban Review, 52, 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00515-4

Parkes, A., Sweeting, H., & Wight, D. (2015). Parenting stress and parent support among mothers with high and low education. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(6), 907–918. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000129

Parks-Yancy, R., DiTomaso, N., & Post, C. (2009). How does tie strength affect access to social capital resources for the careers of working and middle class African-Americans? Critical Sociology, 35(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920509103983

Pattillo-McCoy, M. (1998). Church culture as a strategy of action in the Black community. American Sociological Review, 63(6), 767–784.

Perrin, A. (2015). Social Media Usage. Pew Research Center, 125, 52–68.

Pew Research Center (n.d.). Religious landscape study: Racial and ethnic composition. https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/religious-landscape-study/racial-and-ethnic-composition/. Accessed 10 June 2023.

Rahman, J. (2008). Middle-class African Americans: Reactions and attitudes toward African American English. American Speech, 83(2), 141–176. https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-2008-009

Raikes, H. A., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(3), 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20044

Revelle, W., & Rocklin, T. (1979). Very simple structure: An alternative procedure for estimating the optimal number of interpretable factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 14(4), 403–414.

Sablan, J. (2018). Can you really measure that? Combining critical race theory and quantitative methods. American Educational Research Journal, 56(1), 178–203. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218798325

Segrin, C., & Passalacqua, S. A. (2010). Functions of loneliness, social support, health behaviors, and stress in association with poor health. Health Communication, 25, 312–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410231003773334

Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., & Jeswani, S. (2014). The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research, 117, 561–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0361-

Skarupski, K. A., Fitchett, G., Evans, D. A., & Mendes de Leon, C. F. (2013). Race differences in the association of spiritual experiences and life satisfaction in older age. Aging & Mental Health, 17(7), 888–895. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.793285

Smitherman, G. (2021). Word from the mother: Language and African Americans. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003212423

Solari, C. D., Walton, D., & Khadduri, J. (2021). How well do housing vouchers work for Black families experiencing homelessness?: Evidence from the Family Options Study. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 693(1), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716221996678

Taylor, R. J., Ellison, C. G., Chatters, L. M., Levin, J. S., & Lincoln, K. D. (2000). Mental health services in faith communities: The role of clergy in black churches. Social Work, 45(1), 73–87.

Thomas, C. S. (2015). A new look at the Black middle class: Research trends and challenges. Sociological Focus, 48(3), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2015.1039439

Toombs, A. L., Morrissey, K., Simpson, E., Gray, C. M., Vines, J., & Balaam, M. (2018). Supporting the complex social lives of new parents. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13). https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173994

Ullrich, R., Schmit, S., & Cosse, R. (2019). Inequitable access to child care subsidies. CLASP. https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/04/2019_inequitableaccess.pdf. Accessed 23 Oct 2020.

Volpe, V. V., Katsiaficas, D., & Neal, A. J. (2021). “Easier said than done”: A qualitative investigation of Black emerging adults coping with multilevel racism. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(3), 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000446

Washington, J. A., & Craig, H. K. (1998). Socioeconomic status and gender influences on children’s dialectal variations. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 41(3), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1044/jslhr.4103.618

Williams, D. R., González, H. M., Williams, S., Mohammed, S. A., Moomal, H., & Stein, D. J. (2008). Perceived discrimination, race and health in South Africa: Findings from the South Africa stress and health study. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 441–452.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.

Zalewski, M., Liu, S., Gunnar, M., Lengua, L. J., & Fisher, P. A. (2023). Mental-health trajectories of US parents with young children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A universal introduction of risk. Clinical Psychological Science, 11(1), 183–196.

Zimmerman, R. S., Khoury, E. L., Vega, W. A., Gil, A. G., & Warheit, G. J. (1995). Teacher and parent perceptions of behavior problems among a sample of African American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(2), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02506935

Zwick, W. R., & Velicer, W. F. (1982). Factors influencing four rules for determining the number of components to retain. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 17(2), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr1702_5

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Phil Fisher and the RAPID-EC team at Stanford University. We also thank Dr. John Sideris for his guidance regarding measurement development. We want to thank the families that have participated in the RAPID-EC survey.

Funding

The research reported here was supported by funding from the Imaginable Futures, the Pritzker Children’s Initiative, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Iheoma U. Iruka: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft, funding acquisition. Alexandria Forte: conceptualization, writing—original draft. Sihong Liu: formal analysis, writing—original draft. Jacqueline Sims: writing—original draft. Stephanie Curenton: writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the funders or the RAPID-EC team.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Key Findings

This study validated the Family Cultural Wealth Survey (FCWS) by (1) understanding the factor structure of the FCWS; (2) examining differences by income, family structure, and parental education; and (3) exploring the validity of the tool by examining its association with parental experiences of racial discrimination and parent and child well-being. Based on data collected from 117 socioeconomically diverse Black families with young children, results revealed and confirmed five factors: knowledge and access to resources, supportive network and optimism for challenges, culturally sustaining traditions and practices, spiritual promoting practices, and diverse communication and connection channels. While some differences were found based on income and parental education, analyses indicated that family cultural wealth was associated with parental experiences of discrimination and their emotional well-being, providing adequate psychometrics as a valid tool for measuring the cultural assets of Black families with young children.

Public Relevance

The Family Cultural Wealth Survey is a valid measure that assesses the cultural wealth of Black families with young children, providing a tool to help professionals uncover the cultural assets to more effectively support their economic, health, and social well-being.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iruka, I.U., Forte, A.B., Liu, S. et al. Initial Validation of the Family Cultural Wealth Survey: Relation with Racial Discrimination and Well-being for Black Families. ADV RES SCI (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-024-00139-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-024-00139-y