Abstract

While Ethiopia has six species of stingless bees, indigenous knowledge of them has not been well documented. In southwestern Ethiopia, we documented the Sheka community’s knowledge of stingless bees. We used the snowball sampling technique to locate 60 experienced honey collectors, conducted semi-structured interviews, and complemented interviews with field observations during honey collection trips with interviewees. Given the scarcity of aboveground nesting stingless bees, honey collectors only collected honey from stingless bees nesting belowground. The average age of the honey collectors was 43 years, but there was much variation in both age and the number of years of experience, indicating that the tradition is handed down between generations. To find the underground nests in the field, honey collectors used several methods, including directly observing nest entrances and worker bee movement, attaching a thread to the worker bee, and listening for the humming sound of the bee’s natural enemy (wasp). Wild nests were always harvested destructively. A single farmer kept ground-nesting stingless bee colonies at his backyard using uniquely tailored wooden hives. Collected honey was used for home consumption, disease treatment, and the generation of income. Our findings illustrate the Sheka community’s deep indigenous knowledge of ground-nesting stingless bees. To facilitate the establishment of stingless bee beekeeping (meliponiculture) in the study area, we may build upon this indigenous knowledge by field research on the biology of stingless bees, taxonomic studies to assess the diversity and identity of ground-nesting stingless bees, and engineering studies to develop beekeeping practices. Together, this may allow for better income for local farmers and avoid the risk of overexploitation of wild stingless bee nests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stingless bees (Apidae: Meliponini) are mostly found in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world, and there are more than twenty species in Africa (Eardley 2004; Michener 2007; Eardley and Kwapong 2013). Like honeybees of the genus Apis, all stingless bees in Africa are eusocial and live with many individuals in a single nest (Eardley 2004). Stingless bees are ecologically, economically and culturally important (Heard 1999; Slaa et al. 2006; Rao et al. 2016; Quezada-Euan et al. 2018). For example, stingless bees contribute to the pollination of crops and wild plants (Roubik 1995; Heard 1999; Slaa et al. 2006; Nkoba et al. 2014). Their honey is used in the treatment of several diseases (Kumar et al. 2012; Rao et al. 2016) and can be sold for cash (Kumar et al. 2012; Quezada-Euan et al. 2018). Meliponiculture, which is beekeeping with stingless bees, takes place across the world but is most advanced, and has the longest history, in the Neotropics (Cortopassi-Laurino et al. 2006; Quezada-Euan et al. 2018).

In Africa, the honey of stingless bees is mostly gathered by destructive harvesting of wild colonies (Eardley 2004; Cortopassi-Laurino et al. 2006). But there are exceptions, for example, in Tanzania and Angola, where some communities use hollow logs or clay pots as hives (Cortopassi-Laurino et al. 2006). Furthermore, there is meliponiculture in Kenya, for example in communities near Kakamega forest and Mwingi (Macharia et al. 2007). There has also been a keen interest to develop meliponiculture in Ghana, Botswana and South Africa (Cortopassi-Laurino et al. 2006; Kwapong et al. 2010). Meliponiculture can replace the destructive harvesting of stingless bee nests, provide food and medicine in the form of honey, provide cash when selling the honey at the market, and contribute to the pollination of crops and wild plants (Eardley 2004). Despite this, the knowledge of the taxonomic and genetic diversity of stingless bees in Africa is relatively low, with many species still to be discovered and described (Eardley 2004; Ndungu et al. 2018).

Only six species of stingless bees are known from Ethiopia, namely Meliponula beccarii (Gribodo, 1879), Liotrigona bottegoi (Magretti, 1895), L. baleensis sp. nov., Hypotrigona gribodoi (Magretti, 1884), H. ruspolii (Magretti, 1898) and Plebeina armata (Magretti, 1895) (Fichtl and Adi 1994; Pauly and Hora 2013). While there is a long tradition of honey collection from wild stingless bees by different communities, meliponiculture is unknown in Ethiopia. The Sheka zone is one of the country’s areas with the highest forest cover, and the area may have potential for stingless bee honey production. However, while honeybees are commonly kept in purpose-made hollow logs placed in large trees, the local community is known to collect honey from stingless bee colonies only from the wild (Shenkute et al. 2012).

Despite the potential for production of honey from stingless bees, the value of stingless bees and their products for the community is not recognized by the government and is not included in the agricultural extension system. Moreover, we lack documented information associated with indigenous knowledge of honey production practices and its use, even though stingless bee honey collection is considered as an important activity in the culture of the Sheka community (Shenkute et al. 2012). Studying the indigenous knowledge of stingless bees may be a first important step towards domestication and establishment of meliponiculture, which could provide pollination for crops and wild plants, honey as food and medicine, and cash income (Eardley 2004; Nkoba et al. 2016). Moreover, it would halt the destruction of wild stingless bee nests. In order to fill this knowledge gap and contribute to the effort to introduce meliponiculture, we documented indigenous knowledge of stingless bees and use of their products by the people in the Anderacha and Masha districts of the Sheka zone, southwestern Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Study area

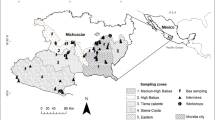

The study was conducted in the Sheka zone, located in southwestern Ethiopia (Fig. 1). Sheka is divided into three woredas (henceforth ‘districts’): Masha, Anderacha and Yeki (7°24′–7°52′ N, 35°13′–35°35′ E). The altitudinal range of the area falls between 900 and 2700 m a.s.l. with an annual rainfall of between 1800 and 2200 mm. The 2175 km2 area consists of natural forest (47%) conserved by the community, while the remaining land is under cultivation or used for livestock, which are the main economic activities in Sheka. The districts produce food crops such as enset (Ensete ventricosum), maize (Zea mays), teff (Eragrostis teff), faba beans (Vicia faba), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and wheat (Triticum spp.). Furthermore, coffee is grown as a cash crop. The community also earns money from the sale of honeybee and stingless bee honey and spices that it collects from the natural forest. The main natural vegetation that stingless bees forage upon are Schefflera abyssinica, Syzygium guineense, Apodytes dimidiata, Vernonia amygdalina, Dombeya torrida, Ekebergia capensis, Ilex mitis, Maesa lanceolata, Olea welwitschii, Croton macrostachyus and Guizotia scabra. For this study, Masha and Anderacha districts were selected based on their accessibility and potential for stingless bee honey collection by the community.

Study design and methods

A cross-sectional design was used to document the indigenous knowledge of stingless bees and their products from the Sheka community. The study was conducted from November 2017 to April 2018 in the Masha and Anderacha districts (Fig. 1). From each district, three kebeles (the smallest administrative units, henceforth ‘villages’) were selected based on prior information obtained from elderly inhabitants on the potential of the area for stingless bee honey production. Within each village, informal discussions with elders and local administrators were held to identify those people knowledgeable about stingless bee honey production. Using the snowball sampling method, which is a non-probability sampling technique where current interviewees recruit further interviewees from among their acquaintances (Bailey 1994), ten stingless bee collectors were selected from each village (n = 60 in total). Thereafter, the purpose of the study was clarified and interview consent was received from the 60 honey collectors.

To complement the semi-structured interviews, we conducted field observations to describe in detail, and validate, the information obtained from individual honey collectors. For this, we joined local honey collectors in their search for and harvesting of wild stingless bee nests in each of the three villages. During our survey, we found 18 wild stingless bee nests. We noted and recorded all activities, such as searching for wild nests, digging out nests from the ground, and harvesting products from the nests. One local honey collector kept stingless bees in wooden hives, and we recorded this practice in detail.

Statistical analysis

To characterize distributions, we presented means, standard deviations and ranges. We tested for differences in means among districts using t-tests, the relationship between two continuous variables using Pearson product-moment correlations, and the relationship between the use of each nest location method and age using logistic regression. All analyses were conducted in R v. 3.6.3 using the base package, and graphs were plotted using the package ggplot2 (Wickham 2016, R Core Team 2020).

Results

Socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents

From the 60 honey collectors, 58 were male and 2 were female (Table 1). The majority were literate and married (Table 1). The common occupation among respondents was farmer and mead brewer, with a few being government employees or students (Table 1). Honey collection from stingless bees was done by those with and without livestock, and those that own or do not own land (Table 1). The average age of the honey collectors was 43 years, but the ages varied widely from 18 to 73 years (Fig. 2a). The respondents had collected stingless bee honey for an average of 14 years, but the number of years varied widely from 2 to 52 years (Fig. 2b). The average age at which the honey collectors started to collect honey was 29, with ages ranging from 10 to 62 years (Fig. 2c). There were no differences among the districts in the age of the honey collectors, years of experience with honey collection, and age at which the honey collectors started (t58 = 0.57 and P = 0.57, t58 = 1.66 and P = 0.10, t58 = 1.24 and P = 0.22, respectively). The respondents said that they obtained their knowledge of stingless bees and use of their products from their parents and neighbours and that honey of ground-nesting stingless bees had been collected by their ancestors for centuries.

Age and experience of 60 local honey collectors in Sheka zone, southwestern Ethiopia. Shown are histograms of a) age of honey collectors, b) number of years of experience with honey collection, and c) age at which the honey collectors started collecting honey. The dashed vertical lines represent the means

Description of types of stingless bees and their habitats

The respondents distinguished between stingless bees that nested below- or aboveground. The stingless bees nesting below- and aboveground are referred to as shaweti and bobbao, respectively, in the local language Shekinnono. The aboveground nesting stingless bees build their nests mainly in hollow tree trunks, other cavities, under the roof of dwellings and in empty log hives. The ground-nesting stingless bees build their nests in the soil, with only the nest entrance visible (Fig. 3a and b). Respondents said they did not collect honey from aboveground nesting stingless bees because these bees are mainly found in remote and inaccessible areas at lower elevations. Hence, our study focused only on the ground-nesting stingless bees. The respondents stated that the ground-nesting stingless bees were abundant and that they frequently collected their honey. All honey collectors recognized two types of ground-nesting stingless bees, black and red types, with the black type characterized by a larger body size, higher number of nest inhabitants, and higher productivity than the red. Moreover, they differentiated the two types of bee based on the nest entrance: The black type had a wider entrance, which protruded further from the ground, than that of the red type (Fig. 3a and b).

Overview of the harvesting process of wild ground-nesting stingless bee honey. Panels a and b show the nest entrances of the red and black stingless bee type, respectively, c shows the digging up of the underground nest using a spade, d shows an excavated nest, e shows the cleaned nest with the brood surrounded by honey jars, and f shows the extraction of honey from the nest, with the metal collection plate in the background

The nests of ground-nesting stingless bees can be found in intact forest and on grazing and farming land. However, the respondents stated that most of the nests were found far away from residential areas, and nests were only rarely found near residences.

Methods for locating wild stingless bee nests

The honey collectors in the surveyed districts shared four methods to locate the nests of the ground-nesting stingless bees. Twenty-three respondents reported that when they were walking through the intact forest, disturbed forest, and other areas to search for wild stingless bee nests, they looked for nest holes on the ground. Twenty respondents stated that they looked for the presence of stingless bees, and when they observed the bees, they conducted a dedicated search within the vicinity. When observing any bee activity in such areas, they also silently squatted down on the ground and looked for forager stingless bees returning to or leaving nests. Fifteen respondents reported that they caught stingless bee foragers on the flowers of several plant species and tied a coloured thread, which is most often red, around their petiole (i.e., narrow waist). After tying the thread, they squatted down on the ground, released the foraging bee, observed the flight direction of the bee, and then followed the bee in the direction of its nest. Seven respondents reported that when they searched for the nests during the harvesting season, they used the nest smell to locate the nest. The honey has a strong smell that can be detected from a distance and helps in deciding on the search area and where to locate the nest. In addition to the aforementioned methods, which were equally common in both districts, seven respondents from the Anderacha district used the stingless bee enemy (a wasp) as an indicator to locate the nests. They located the nests by listening for the humming sound that the wasp makes at the stingless bee nest entrance. The use of the different nest location methods was not related to the age of the honey collector (all P > 0.43).

There was a consensus among the respondents that one can search for wild stingless bee nests from 8:00 to 11:30 and 13:30 to 17:30 but that the most effective times are in the morning from 8:30 to 10:30 and in the afternoon from 14:00 to 16:30. When asked why they did not search for nests in the middle of the day, several respondents mentioned that stingless bees prefer cool weather conditions for foraging and do not exit the nest during the hottest time of the day.

The majority of respondents (n = 44) stated March to April as the harvesting period for stingless bee honey, 16 respondents indicated November to January, and 9 respondents gave both periods. All respondents described that when they found stingless bee nests outside of the honey-harvesting season, they placed their own unique symbol around the nest, and then left the nest until the start of the harvesting season. They placed the nest markers in great secret, to avoid other people spotting the markings and harvesting the nest’s honey. As markers, they used small sticks (n = 24 respondents) or stones (n = 16 respondents) or remembered the location by already existing objects like trees or large stones (n = 20 respondents), which would allow finding the nest back during the honey-harvesting season. The marking methods did not differ among the districts (χ2 = 0.00, df = 2, P = 1.00).

Harvesting of honey from wild nests

Honey is a non-timber forest product that is highly appreciated by the local communities in the study area. Although the respondents recognized several types of products within the bee’s nest (honey, pollen, propolis and cerumen), they mainly collected the honey, and only 15 respondents stated that they collected propolis.

To harvest honey from wild stingless bee nests, the respondents used different local materials, such as a spade, machete (gejera) and/or knife, a metal collection plate, and small plastic or glass bottles. To safeguard the nest entrance, the honey collectors started by placing an indicator at the nest entrance and cleaning the ground surface up to 35 cm from the nest entrance. They then dug around the nest until they reached the bottom of the nest, which is generally 35 to 40 cm deep (Fig. 3cd). The entire nest is then pulled out and placed on a broad leaf of enset (E. ventricosum) or on a flat piece of plastic. Soil and other materials are then removed from the exterior of the nest (Fig. 3e). Lastly, the nest is opened from above, and the brood areas are pulled out to separate them from the honey pots (Fig. 3f).

The majority of the respondents (69%) strained the honey using E. ventricosum fibres, locally known as qacha. After separating the brood area from the honey pots, they placed the fibres on top of the metal plate and squeezed the honey pots with their contents above it. The fibrous material is used to retain any impurities and allows passing through of the pure liquid honey. The other respondents (31%) pierced a hole in each individual honey pot, so that the pure honey flowed directly to the metal plate (honey container). However, they noted that if a nest was constructed between the roots of a tree or shrub, the nest could suddenly crush and become difficult to pull out of the ground. In such a scenario, they would cut the nest, crush all of its contents together, and squeeze out the storage pots. They would then strain the impure honey later using qacha. The respondents did not give any attention to the broods, and during harvesting the whole nest was destroyed, resulting in the bees absconding. In all study areas, honey was stored in a plastic or glass bottle. However, respondents stated that the small plastic bottles are hard to clean and are, therefore, less hygienic.

The average number of wild stingless bee nests harvested per respondent per year was 9.6 ± 8.7 (mean ± SD) and was higher in Masha district (12.4 ± 10.7) than in Anderacha district (6.77 ± 4.78; Fig. 4a; t58 = 2.61 and P = 0.01). The average amount of honey harvested per nest was similar in Masha (2.4 L ± 1.2) and Anderacha districts (2.2 L ± 1.1; Fig. 4b; t58 = 0.73 and P = 0.47). The number of colonies harvested only weakly increased with age of the respondent (r = 0.25, P = 0.05), whereas experience was strongly and positively correlated with the number of colonies harvested (r = 0.49, P < 0.001). According to the respondents, honey yield of wild colonies can differ based on nest age, and when a nest is older than one year, it can produce up to 5 L.

The amount of wild stingless bee nests and honey harvested by 60 honey collectors in the Sheka zone, southwestern Ethiopia. Shown are density plots for a) the number of nests harvested and b) the average amount of honey harvested per nest by the honey collectors from Masha (n = 30 honey collectors) and Anderacha districts (n = 30)

Local meliponiculture

All but one of the respondents collected honey from wild stingless bee nests. According to these respondents, domesticating and managing colonies of ground-nesting bees using hives is difficult, and they believe the reason is that the colonies obtained heat from the soil underground and were thus not adapted to hives placed aboveground.

However, one out of the 60 respondents practiced meliponiculture, thereby illustrating that it is possible to establish meliponiculture. The respondent lived in Anderacha district and kept colonies of ground-nesting stingless bees in his backyard using square wooden hives (Fig. 5). Each hive was prepared in a traditional manner from wooden boards joined by nails, with each side measuring 36 × 36 cm. Each hive had a single small hole at the fixed upper wooden board, which served as the hive entrance (Fig. 5a). The bottom board of the hive was designed to open for the purpose of honey harvesting (Fig. 5b). To support the nest, each hive had four thin wires attached to the upper board and suspended towards the inner part of the hive. Two small sticks that crossed each other, and were joined by a nail, were attached to the wires, so the sticks could hold the nest. The respondent described that after he prepared a wooden hive, he would collect a wild ground-nesting stingless bee nest, place it on the supportive sticks and attach it using the wires to the upper board, so that the nest was hanging inside the hive (Fig. 5c and d). Thus, the nest did not have contact with the sides of the hive. This was mainly to avoid any difficulty during honey harvesting, when the hive was opened from its bottom board. The honey harvesting method was nondestructive, and only honey was harvested. The pure honey was harvested by using a purposively prepared sharp stick to penetrate each pot and let the honey flow out. According to the respondent, he was able to harvest honey from the colonies in the wooden hives twice a year and opened the hives only during honey harvesting time. During the study, we observed many hives without colonies and the respondent told that 21 out of the 26 colonies had absconded for unknown reasons.

Wooden hive for ground-nesting stingless bees. Panel a shows the wooden hive from the upper side, with the red arrow pointing towards the hive entrance (hole) in the upper board. Panel b shows the bottom board of the hive, which can be opened for the purpose of honey collection. The blue arrow points towards the metal strip used to close the board. Panels c and d show how the stingless bee nest is placed inside the hive. The nest is placed on two crossed, supportive wooden sticks, which are attached to the inner surface of the upper board using wire

The use of products from stingless bees

The reasons for honey collection were quite similar throughout the study area. The stingless bee honey was mainly used for home consumption. According to the respondents, honey was consumed either immediately after being extracted or after storage, when it was eaten either pure or mixed with water or local drinks known as borde and tella (Lee et al. 2015). The honey was valued as a food supplement and also used for the treatment of different types of diseases like tuberculosis, coughing, malaria, constipation, asthma, tonsillitis and oral thrush. Propolis was used to seal or repair cracked clay pots, plastic containers and other domestic appliances.

Because of its medicinal and nutritional value, the price of stingless bee honey is triple that of honey from honey bees and sells for 150–200 Ethiopian Birr (ETB) as compared to 60–78 ETB.

Threats to stingless bees

The respondents did not observe signs of brood diseases or diseased bees, suggesting that stingless bees are largely disease-free in the study area or that diseases go unnoticed. However, they indicated that stingless bees are attacked by several natural enemies, which included honey badgers (21.2%), moles (19.8%), wasps (14.6%), termites (14.3%), ants (13.8%), foxes (13.1%) and snakes (3.2%). When asked what other factors they see as a threat to stingless bee colonies, the respondents mentioned deforestation, forest and soil degradation, and pesticides.

Limitations to the adoption of local meliponiculture

The respondents pointed out several obstacles that were limiting the development of meliponiculture. These included the fact that stingless bees were not yet domesticated and no extension services and training were provided. Thus, there was an absence of technology for and knowledge of stingless bee beekeeping and their honey harvesting, processing, handling and other management practices. Another reason was that stingless bees often produce only small amounts of honey.

Discussion

Using semi-structured interviews and detailed field observations, we characterized the traditional knowledge of stingless bees in Sheka zone, southwestern Ethiopia. We found deep indigenous knowledge of honey harvesting and bee product usage from wild, underground stingless bee nests, which is a part of a cultural tradition that has been passed on orally from one generation to the next. Honey collectors used several methods to find the wild stingless bee nests, i.e. directly observing nest entrances and bee movement, attaching a thread to the worker bee, and listening for the humming sound of a wasp, the bee’s natural enemy. The wild nests were always harvested destructively. A single respondent maintained stingless bee nests in wooden hives in his backyard, indicating the potential for meliponiculture.

Socioeconomic status of honey collectors

Our findings indicate that the participation of women in stingless bee’s honey collecting activities in the study areas is low, with only two out of 60 honey collectors being female. The major reason may be that nest hunting is generally considered the work of men, just like the placement of hollow wooden logs for the honeybee Apis mellifera into large trees (Abebe 2011; Kinati et al. 2012; Shenkute et al. 2012). Hunting usually involves searching for wild bees in forests far from residential areas, and roaming through forests alone is culturally considered as taboo for females. Hence, women participation may increase with the adoption of meliponiculture. Honey was collected mostly by married persons (85%), which the respondents attributed to the medicinal value of stingless bee honey for children. The honey collectors had a diverse economic background: Honey was collected by both economically productive and economically dependent age groups (the latter defined in Ethiopia as ages below 15 and over 65), literate and illiterate persons, farmers and local mead brewers, as well as students and government employees, those with and without livestock, and those with and without land. Overall, this indicates there is no restriction of honey collection to specific subgroups within the local community.

The honey collection experience of the respondents ranged from 2 to 52 years. The short experience, and low age, of some of the honey collectors indicate that honey collection is a living tradition within the study area that is handed on from older to younger generations. Of particular note is the fact that honey collectors started with harvesting stingless bee nests at a wide range of ages, indicating that both younger and older people can acquire the necessary skills and/or start the practice of honey collection.

Stingless bee diversity

As repeatedly pointed out, the diversity and distribution of stingless bees in Africa is poorly known (Eardley 2004; Eardley and Kwapong 2013; Pauly and Hora 2013; Ndungu et al. 2018). Within Ethiopia, only six species of stingless bees have been reported, which is most likely an underestimation (Pauly and Hora 2013). From the species recorded in Ethiopia, only Meliponula beccarii is known to build its nests underground (Pauly and Hora 2013). This lack of knowledge of the taxonomic identity and biology of stingless bees hampers progress (Eardley and Kwapong 2013; Ndungu et al. 2018). We need future research that characterizes the diversity and distribution of stingless bee species within the study area, Ethiopia and Africa. Such insights are also important for conservation. For example, Nkoba et al. (2017) found that habitat degradation reduced stingless bee diversity in a tropical rainforest in Kenya. The respondents identified honey badgers, moles, wasps, termites and ants as the major natural enemies, which matches the findings from Shenkute et al. (2012), who reported that ground-nesting stingless bee colonies in Sheka, Kaffa and Bench Maji zones were affected by honey badgers, ants and moles.

The road towards meliponiculture

As stated by Eardley (2004), meliponiculture in Africa is relatively uncommon, and the meliponine honey harvest is mostly destructive. This conforms with described cultural practices in Sheka: The local communities had a diverse and deep indigenous knowledge of local wild stingless bee nest identification, harvesting and use of its products, and this practice has long been an integral part of the communities’ culture. Despite this, only a single respondent practiced beekeeping with stingless bees. It is notable that many of the colonies had absconded, which may relate to the difficulty to maintain ground-nesting stingless bee species. While several scientists have attempted to maintain ground-nesting stingless bees in hives, none of these attempts have been unambiguously successful. It is generally regarded to be more difficult to maintain subterranean nests in hives than aerial nests (De Portugal-Araujo 1963; Armor 1994; Cortopassi-Laurino et al. 2006; Nkoba et al. 2016; Nkoba 2020). For example, De Portugal-Araujo (1963) remarked that both species of ground-nesting stingless bees that he studied in Angola could be maintained in artificial hives, but that it is difficult because they lack adaptation to the oscillations in temperature and suffered from increased attack by natural enemies. More recently, Nkoba et al. (2016) tested a vertically compartmented hive design for three Kenyan species of stingless bees, one of which nested underground, and found that hive acceptance was lower and postharvest colony loss was higher in the ground-nesting species. It would be worthwhile to further explore the potential for meliponiculture of ground-nesting stingless bees. For this we need to complement the valuable indigenous knowledge of ground-nesting stingless bees with studies on the ecology and behaviour of stingless bees in the field, surveys that characterize the taxonomic diversity of stingless bees, and engineering studies that develop the technology necessary for improved beekeeping. With such improved knowledge at hand, we can harness the agricultural extension services to promote and spread knowledge of meliponiculture.

References

Abebe W (2011) Identification and documentation of indigenous knowledge of beekeeping practices in selected districts of Ethiopia. J Agric Ext Rural Dev 3:82–87

Armor, M. 1994. Stingless bees in Angola. http://www.beesfordevelopment.org/documents/s/stingless-bees-in-angola/.

Bailey K (1994) Methods of social research. The Free Press, New York, USA

Cortopassi-Laurino M, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Roubik DW, Dollin A, Heard T, Aguilar I, Venturieri GC, Eardley C, Nogueira-Neto P (2006) Global meliponiculture: challenges and opportunities. Apidologie 37:275–292

De Portugal-Araujo V (1963) Subterranean nests of two African stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J N Y Entomol Soc 71:130–141

Eardley CD (2004) Taxonomic revision of the African stingless bees (Apoidea : Apidae : Apinae : Meliponini). Afr Plant Prot 10:63–96

Eardley C, Kwapong P (2013) Taxonomy as a tool for conservation of African stingless bees and their honey. In: Vit P, Pedro SRM, Roubik D (eds) Pot-Honey: A legacy of stingless bees. Springer, New York, New York, NY, pp 261–268

Fichtl R, Adi A (1994) Honeybee flora of Ethiopia. Margraf Verlag, Weikersheim, Germany

Heard TA (1999) The role of stingless bees in crop pollination. Annu Rev Entomol 44:183–206

Kinati C, Tolemariam T, Debele K Tolosa T (2012) Opportunities and challenges of honey production in Gomma district of Jimma zone, South-west Ethiopia

Kumar MS, Singh AJAR, Alagumuthu G (2012) Traditional beekeeping of stingless bee (Trigona sp) by Kani tribes of Western Ghats, Tamil Nadu, India. Indian J Tradit Know 11:342–345

Kwapong P, Aidoo K, Combey R, Karikari A (2010) Stingless bees: Importance, management and utilisation: A training manual for stingless bee keeping. Unimax MacMillan, Ghana

Lee M, Regu M, Seleshe S (2015) Uniqueness of Ethiopian traditional alcoholic beverage of plant origin, tella. J Ethn Foods 2:110–114

Macharia J, Raina S, Muli E (2007) Stingless bees in Kenya. Bees for Development Journal 83:9

Michener CD (2007) The bees of the world. 2nd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Ndungu NN, Nkoba K, Sole CL, Pirk CW, Abdullahi AY, Raina SK, Masiga DK (2018) Resolving taxonomic ambiguity and cryptic speciation of Hypotrigona species through morphometrics and DNA barcoding. J Apic Res 57:354–363

Nkoba K (2020) Contribution de l’ICIPE à la promotion de la méliponiculture en Afrique. Mayazine 38:28–30

Nkoba K, Raina SK, van Langevelde F (2017) Impact of habitat degradation on species diversity and nest abundance of five African stingless bee species in a tropical rainforest of Kenya. Int J Trop Insect Sci 37:189–197

Nkoba K, Raina SK, Muli E, Mueke J (2014) Enhancement of fruit quality in Capsicum annum through pollination by Hypotrigona gribodoi in Kakamega, Western Kenya. Entomol Sci 17:106–110

Nkoba K, Raina S, Langevelde F (2016) A vertical compartmented hive design for reducing post-harvest colony losses in three afrotropical stingless bee species (Apidae: meliponinae). Int J Dev Res 06:9026–9034

Pauly A, Hora ZA (2013) Apini and Meliponini from Ethiopia (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Apidae: Apinae). Belgian J Entomol 16:1–35

Quezada-Euan JJ, Parra G, Maues M, Roubik D, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL (2018) The economic and cultural values of stingless bees (Hymenoptera: Meliponini) among ethnic groups of tropical America. Sociobiology 65:534

Core R, Team. (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Rao PV, Krishnan KT, Salleh N, Gan SH (2016) Biological and therapeutic effects of honey produced by honey bees and stingless bees: a comparative review. Rev Bras Farmacogn 26:657–664

Roubik DW (1995) Pollination of cultivated plants in the tropics: Stingless bee colonies for pollination. FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin 118:198

Shenkute AG, Getachew Y, Assefa D, Adgaba N, Ganga G, Abebe W (2012) Honey production systems (Apis mellifera L.) in Kaffa, Sheka and Bench-Maji zones of Ethiopia. J Agric Ext Rural Dev 4:528–541

Slaa EJ, Chaves LAS, Malagodi-Braga KS, Hofstede FE (2006) Stingless bees in applied pollination: practice and perspectives. Apidologie 37:293–315

Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the ground-nesting stingless bee honey collectors of Sheka community for participating in this study and for sharing their knowledge of stingless bees and their products, the local and regional administrations for providing the permits to conduct this study, the Southern Agricultural Research Institute in Hawassa for financially supporting this study, and Anna Barr for editing the manuscript for grammar.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Stockholm University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kidane, A.A., Tegegne, F.M. & Tack, A.J.M. Indigenous knowledge of ground-nesting stingless bees in southwestern Ethiopia. Int J Trop Insect Sci 41, 2617–2626 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42690-021-00442-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42690-021-00442-6