Abstract

Australia’s Indigenous children are 12 times more likely than non-Indigenous children to be in out-of-home care, a rate that has been increasing. Since 2009, government policies have committed to keeping children safe in families through support, early intervention, and Indigenous self-determination. Action has not matched policy. Quantitative and qualitative survey data from third parties (n = 29 Indigenous and n = 358 non-Indigenous) are analysed with a view to understanding expectations and visions for reform. Third parties expressed distrust and resistance toward child protection authorities. Indigenous third parties more so. Achieving reform objectives depends on child protection authorities initiating relational repair with third parties through addressing ritualism, implementing policy and investing in genuine partnering. Indigenous third parties, in addition, identified institutional racism and cultural disrespect as obstacles to reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In step with other Anglophone countries, Australia has adopted a public health framework to guide child protection reform (Council of Australian Governments, 2009; Lonne et al., 2008). This article focuses on the reform journey in Australia since the late 1990s, particularly as it has addressed the concerns of Indigenous Australians who have sought self-determination on child protection matters. Actioning self-determination has been a low government priority since the reform agenda was launched in 2009. This article revisits the voices of Indigenous third parties expressed at the beginning of the reform journey in 2010. The knowledge and opportunities for partnering that they shared, along with the obstacles they so astutely and presciently identified, provide a base for reflection for the whole child protection community.

Implementing both the public health and self-determination agendas successfully requires child protection authorities to share power with other agencies, communities, families and children. Lack of mutual trust is a major obstacle to sharing power for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities of practice. This article argues that, partly for historical reasons, child protection authorities must take the first step in building relationships of trust through proving their trustworthiness. These steps involve acknowledging discrimination and oppression, engaging in power sharing and offering the right kind of support.

The article has 7 parts. In Part 2, signal events in recent history are described revealing reform intentions and outcomes, particularly as they have affected Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Next, the difficulties that child protection authorities have had and continue to have in establishing effective partnerships with families and third parties (those working alongside child protection) are discussed. Part 4 discusses why relational repair is needed. Motivational posturing theory is introduced to uncover bases of trust and distrust in authorities. Part 5 draws upon a survey of third parties at the commencement of the nationally led reform agenda to evidence relational breakdown with child protection authorities, more so for Indigenous third parties. Part 6 restricts the survey focus to qualitative responses from Indigenous third parties. Their voices, rebuffed more often than actioned, provide a vision for change and a deeper understanding of the reasons for mistrust. Part 7 presents the argument that trust building and reform depend on child protection authorities taking the first step to address their colonial baggage and overcome their institutional insecurities.

Signal Historical Events of Reform Intentions and Outcomes

Awareness Raising

In 1997, the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission released the Bringing Them Home Report, setting out Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait IslanderFootnote 1 people’s experiences of the forced removal of children from their families between 1910 and the 1970s. Children were taken by the police on sight and placed in institutions, foster homes or adopted by non-Indigenous families as part of a government policy of assimilation and, in effect, cultural genocide. Around 1000 people gave evidence of the suffering of Stolen Generations through systemic racism, exploitation, denigration, psychological, physical and sexual abuse (Australian Human Rights Commission, 1997).

Awareness of institutional harms to both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous children was imprinted on the national consciousness with the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse conducted from 2013 to 2017. While Volume 11 of the 17-volume report addressed historical sexual abuse in residential homes, Volume 12 addressed contemporary child abuse in out-of-home care (Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, 2017).

Apologies

These reports marked a national awakening of the harms experienced by children and communities when children were removed forcibly from family, culture and place, an unquestioned policy adopted by governments until this century (Swain & Hillel, 2010). Both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous Australians have received public apologies from the federal government for past policies of child removal.Footnote 2

In 2008, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd gave a formal apology to Aboriginal ‘Stolen Generations’ on behalf of the Australian Parliament. The apology not only recognised past harms but ‘embrace[d] the possibility of new solutions to enduring problems where old approaches have failed.’Footnote 3 The intent was to change the trajectory of disproportionate child removals from Aboriginal families, recognise intergenerational trauma, and acknowledge the importance of connection to country and culture for healing and thriving.

Next, in 2009, Prime Minister Rudd and Opposition Leader Malcolm Turnbull issued a national apology for the abuse and cruelty experienced by ‘The Forgotten Australians’, who as children had been placed in orphanages or children’s homes or foster care.Footnote 4 The Forgotten Australians included child migrants brought to Australia on pretence of a better life to increase the population and labour force.

The third was the ‘National Apology for Forced Adoptions’ in 2013 delivered by then Prime Minister Julia Gillard to people affected by coercive and deceptive removal policies and practices.Footnote 5 All three apologies recognised the intergenerational trauma associated with child removals for Aboriginal and non-Indigenous families. Promises were made to learn lessons from the past. Policies with good intent were developed. But in practice, promises were broken.Footnote 6

National Frameworks for Protecting Australia’s Children

Two long-term action plans accompanied acceptance by state and federal governments of the harms of child removal. The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 (Council of Australian Governments, 2009) and the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2021–2031 (Department of Social Services, 2021) were developed under the auspices of the Federal Government and in collaboration with Australia’s six state and two territory governments with jurisdictional responsibility for child protection.

These frameworks advocate a public health approach with early intervention for struggling families, greater emphasis on collaborative evidence-based practice across professions and agencies, and coordinated data collection on child protection activities across jurisdictions. Consultation with families and preservation of family and cultural connections featured prominently in both plans, with specific reference to Aboriginal children. Both Frameworks reaffirmed the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Placement Principle, prioritising the preservation of children’s connection to family, community, culture and country (Arney et al., 2015).

While progress has been made on data collections and ‘wrap-around’ coordinated services, collaborative practice that respects the voice of advocacy groups, families and children is far from being mainstreamed across jurisdictions (Davis, 2019; Hamilton et al., 2022; Morley et al., 2022; Ross et al., 2017).Footnote 7 The five elements of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Placement Principle—prevention, partnership, participation, placement and connection—have been poorly implemented (Davis, 2019; Department of Social Services, 2020, 2021; SNAICC, 2022). This is particularly egregious given that the first version of the principle was articulated through the efforts of a grassroots community movement in the 1970s (Arney et al., 2015).

Outcomes

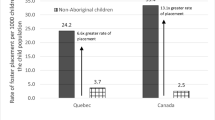

The most compelling evidence that reforms have not filtered through to change child protection practices on the ground lies in the data. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s most recent report underlined the reach of child protection with 1 in 32 children under the age of 18 in contact with the child protection system and 1 in 124 children assessed as being maltreated (or at risk) (AIHW 2023). The reasons recorded for substantiated maltreatment were emotional abuse (57%), neglect (21%), physical abuse (14%), and sexual abuse (9%). Indigenous children were 7 times more likely than non-Indigenous children to be subject to substantiation of maltreatment, 11 times more likely to be on care and protection orders where the government has assumed some responsibility for their care, and 12 times more likely to be in out-of-home care.Footnote 8

In recent years, statistics have worsened for Aboriginal children compared with their peers in relation to removal from families, removal of infants, adoption to non-Indigenous families, long-term care arrangements without re-unification goals, and experiences of physical, sexual and emotional abuse in out-of-home care (SNAICC, 2022). Between 2018 and 2022, the care and protection rate and the out-of-home care rate have increased for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, while rates for non-Indigenous children have remained relatively stable. In 2022, over a third of Indigenous children in out-of-home care were placed outside family and kin, the least preferred option under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Placement Principle.Footnote 9

The second Framework for Protecting Australia’s children (2021–2030) includes a special Action Plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders with a commitment to self-determination.Footnote 10 Aboriginal peak bodies have expressed an intent to operate in a more relational, holistic and supportive way with Indigenous families (SNAICC, 2022). How this will be resourced (beyond special pilot projects) and what form the relationship will take between Aboriginal self-determination champions and child protection authorities remain unclear. Recent public rejection of constitutional recognition for Aboriginal peoples may slow the process.

In October 2023, the Australian public voted resoundingly against a referendum proposal to give constitutional recognition to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in the form of a Voice to Parliament.Footnote 11 The purpose of the Voice to Parliament was to advise on policies that affect Aboriginal peoples and was part of the Aboriginal Reconciliation proposal, the Uluru Statement of the Heart.Footnote 12 Other components of the Reconciliation proposal are developing a post-conflict Treaty (MakarrataFootnote 13) and Truth Telling. Dispossession of country, cultural genocide and frontier wars are unfinished conversations among Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The Uluru statement lent weight to implementing self-determination in child protection as flagged in the second National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children. The risk that the failed Voice referendum poses is that governments will be timid to advance self-determination that is properly resourced and mainstreamed in the child protection system.

Relational Care: Not a Natural Fit for Child Protection Authorities

Child protection authorities worldwide have long been criticised for systematically failing to engage with families in ways that establish constructive working partnerships (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2020; Burford & Pennell, 1998; Dettlaff et al., 2020; Lonne et al., 2013; Merritt, 2020; Morris & Featherstone, 2010; Munro, 2011). An extensive body of research documents how families who come to the attention of child protection are ‘walking on eggshells’ (Buckley et al., 2011). Parents are fearful of having children removed and are often left in the dark over what will happen next, when it will happen, and how they should make sense of and prepare for interactions with the authorities (Harris, 2011, 2012; Harris & Gosnell, 2012; Lonne et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2017). Relational care requires flipping these negative relationships into respectful relationships, working ‘with’ families not ‘on’ families, and being responsive to their needs.

Part of the problem is that child protection authorities are not open, learning organisations: They are state-centred, siloed, bureaucratised and risk-averse, struggling to process heavy caseloads and complex cases, and reliant on assessment and decision-making protocols that are oppressive (Dettlaff et al., 2020; Keddell, 2019; Lonne et al., 2013; Merkel-Holguin et al., 2022; Morley et al., 2022; Parton, 2014; Yang & Ortega, 2016).

The other part of the problem is that the culture of child protection is imbued with moral judgement and legitimates domination (MacAlister, 2022; Marsh et al., 2015). Parents report feeling blamed and stigmatised as bad parents and being punished for their failings (Ivec et al., 2012; Mason et al., 2020); in the words of some, being treated as ‘less than human’ (Smithson & Gibson, 2017). For this reason, an institutional shift from a forensic, investigative approach to a public health approach may not necessarily encompass a relational approach—genuine partnering of child protection authorities with children, families and their support networks. A public health approach with its emphasis on early intervention, prevention and recovery requires better coordination across services and expertise and gives child protection authorities an incentive to be less siloed and opaque than in the past. But prevention and recovery also rely on inclusion of children, families and their informal support networks (Burford & Pennell, 1998; Lalayants & Merkel-Holguin, 2023). Yet they remain at the periphery of child protection decision-making (Hamilton et al., 2022). Power sharing and trust building with families and third-party agencies, central to relational care, are not necessarily guaranteed in the public health approach (although it is recommended and expected!). Impediments to relational care in child protection are going to be harder to shift through a public health approach because they have deep institutional roots of colonial baggage, control and power, and stigma.

Child Removal—A Sticky Colonial Institution

The obduracy of child protection authorities cannot be divorced from their history. Swain and Hillel (2010) have provided broad ranging accounts of the deep-rooted colonial practice of removing children from families judged to be unsuitable or dangerous or culturally unacceptable: a cultural narrative that prevails to this day as a well-trodden, morally justifiable path (Broadhurst & Mason, 2013; Chase & Ullrich, 2022; Krugman and Korbin, 2023). Institutional path dependency has kept alive the link of child removal to protection of the child, despite evidence to the contrary.

A Siloed and Powerful Institution

Child protection authorities have been criticised for lacking transparency around their decision-making (Davis, 2019). Processes fail to embody procedural justice, particularly around accountability, impartiality and decision review (Davis, 2019; Harris, 2011; Harris & Gosnell, 2012; Ivec et al., 2012; Krumer-Nevo, 2020). They also fall short on relational care ethics around listening and communicating honestly and openly with families and support workers (Burford et al., 2019; Dettlaff et al., 2020; Featherstone et al., 2018; Lonne et al., 2008). Case management practices have been criticised as oppressive, stigmatising, unreasonable and unfair (Braithwaite, 2021a; Maslin and Hamilton, 2020; Merkel-Holguin et al., 2022).

Most damning are accounts of how child protection authorities are too remote and ritualistic to meet their mission of acting in the best interest of the child (Davis, 2019). They may even open pathways to further abuse, exploitation and criminal activity (Maslin and Hamilton, 2020; Purtell et al., 2021). The Australian Centre for Child Protection (2020) has reviewed child protection case files and shown the unsuitability of many interventions: Interventions do not match needs.

Courtesy Stigma

The stigma attached to parents involved with child protection spreads to the third parties associated with them, by virtue of the support they offer to families deemed ‘undesirable’ or ‘bad’ (Hamilton et al., 2020a, b). Those who support families complain of courtesy stigma and the dismissive treatment they experience at the hands of child protection authorities (Braithwaite & Ivec, 2022; Hamilton et al., 2020a, b; Krumer-Nevo, 2020; Marsh et al., 2015; Maslin and Hamilton, 2020). Complaints range from not being informed about processes and decisions to deliberate exclusion from decision-making, having their knowledge dismissed as irrelevant, being accused of bias and of caring less about children than their parents.

Time for Relational Repair, Reading Motivational Postures

Third Parties’ Mistrust of Child Protection

Child protection authorities tend not to have the trust of third parties who provide regular support for families (Braithwaite & Ivec, 2022; Hamilton et al., 2020a, b). Yet child protection authorities rely on these third parties not only for service delivery but also for monitoring care for children. The effectiveness of this working relationship is limited when child protection authorities are seen to lack trustworthiness (Chase & Ullrich, 2022; Coates, 2017; Holland, 2014; Humphreys et al., 2018). Maslin and Hamilton (2020), for instance, report that third parties ‘take liberties’ (p. 346) with their mandatory reporting obligations when they see injustice and lack of care in the actions of authorities. Taking liberties is just a slice of the resistance that third-party advocacy groups are displaying in a surprisingly open and organised fashion.

Resistance to Child Protection Authorities

Stigmatisation and unreasonable and unfair treatment of parents and their support networks have given rise to a social movement to challenge openly the dominant child protection narrative about ‘undesirable’ families. Among the most vocal are Indigenous advocacy groups. The 2023 Kempe International Virtual Conference showcased an array of initiatives driven largely by families who had experienced the child protection system and who were working with and supported by human rights and social justice advocates and legal services.Footnote 14 Providing support and sharing knowledge among families dealing with child protection is one objective; the other is challenging the system and changing the narrative.

A common theme among advocacy groups is the prevalence of child protection authorities being judgmental of parents who were not coping, in particular, applying the ‘bad mother’ label instead of recognising need and helping out (Broadhurst & Mason, 2013; Davis, 2019; MacAlister, 2022; Ross et al., 2017). For Indigenous advocacy groups who have witnessed higher rates of child removal and intergenerational trauma, the schism is particularly deep. Maleeka Jihad, Executive Director of the MJCF Coalition, explains it this way:

We say so many times, it takes a village, it takes a village, and then as soon as the village shows up, we say absolutely not, you are not a safe village … The ideology is the apple does not fall too far from the tree! … Anytime we try to implement the village of collective cultures … - if it does take a village, why are we not respecting that village?Footnote 15

Prejudice and unconscious bias are without question grievances of families regardless of ethnicity, particularly those who are poor, unemployed, single parents, with disabilities or mental health conditions (Lonne et al., 2013; McConnell & Llewellyn, 2005). But for Indigenous communities, there is also a cultural divide. Maleeka Jihad explains:

Having people with lived experience humanizes the clients. … We don’t refer to our clients as clients… This was working with the Navajo nation - We refer to them as relatives, this is our auntie, this is our uncle, this is our sister, this is our brother, and when you see the clients as your relatives, when you see them as family, you do treat them differently. I do refer to my Elders in the work that I do as my Elders and they get that same respect no matter what they are going through …Footnote 16

Building Trust

Child protection authorities need to better understand what they can do to bridge the cultural gap not only with Indigenous groups, but also non-Indigenous groups. Authorities need to earn the trust of others if meaningful and sustained cooperation is to occur in the sector.

It is a mistake to think that the distrust problem can be handled through ring-fencing child protection authorities when the overarching goal is a safer and better family life for children. Children who have experienced the child protection system are disadvantaged in terms of education, health, housing, and financial support (Australian Centre for Child Protection, 2020; Malvaso et al., 2022; Smales et al., 2020). They are more likely to cross-over into the criminal justice system, a problem particularly acute for Aboriginal youth (Cashmore, 2011; Sentencing Advisory Council, Victoria, 2019). Child protection is an institutional octopus that can have far-reaching impact on the lives of children and families.

Understanding Trustworthiness Through Motivational Postures

Trust defines a relationship where third parties believe that child protection authorities are meeting agreed expectations for protecting children. Broadly, in order to be trusted, they need to (a) accomplish their mission competently and lawfully, (b) be consistent in the principles that guide their practice and be accountable for what they do, (c) have open and timely communication channels, and (d) show understanding of and responsiveness to the needs of those whose lives they affect (Braithwaite, 1998, 2021b).

Third parties’ trust in child protection has been low (Braithwaite & Ivec, 2022; Hamilton & Braithwaite, 2014). But conceptually, trust can be built through active engagement (Braithwaite, 2021b). Trust is a dynamic concept and can fluctuate up and down as expectations are met and not met. An important distinction is whether third parties buy into fluctuating trust—in which case trust can be regained through conversations that clear the air after trust breaches (which are normal), or whether third parties have turned their back on child protection authorities and abandoned hope of a trust relationship (Braithwaite, 2009, b). This distinction is relevant in contexts where promises have been broken repeatedly. A theoretical approach that accommodates analysis of these two sides of trust is motivational posturing theory (Braithwaite, 2009).

Motivational Posturing Theory

Authorities use their power to make demands on our time and energies: They threaten our freedom. Three selves are implicated in this power relationship that are core to our social identity—a moral self (doing the right thing), a justice self (doing what is fair) and an achievement self (doing what is worthwhile). The extent of threat to these selves shapes our response to authority, that is, how close we want to be to them. Motivational postures are the responses or signals we send to authorities to indicate the psychological distance we wish to place between us and them (Braithwaite, 2009).Footnote 17 We do this along two dimensions, one representing acceptance or satisfaction, the other representing willingness to defer to authority.

Of the five motivational postures identified to date,Footnote 18 the posture that best captures trust is capitulation, meaning we will do what an authority asks of us because we are satisfied that the authority knows what is best. When we have doubts and when an authority offends our justice self, we signal dissatisfaction and our trust lowers as we assume a second posture of resistance. Importantly, while posturing resistance, we hold out hope that our protest is not in vain and that the authority will listen to concerns, do the ‘right thing’ and restore our confidence.

The remaining three motivational postures have more to do with deference to authority than satisfaction and trust. The posture of commitment respects the moral authority of an institution. Commitment is associated with being a good professional and aligning one’s moral self with the mission of an authority.

In contrast, the postures of disengagement and gameplaying challenge an authority’s legitimacy and signal willingness to defy an authority’s direction. Disengagement signals withdrawal and an intention to ignore the authority. Gameplaying signals a form of engagement that is about having wins against the authority through knowing the rules and using the law to circumvent an authority’s control. Disengagement and gameplaying are dismissive postures in so far as their intent is to sideline the authority as they pursue goals to satisfy their achievement self. Those signalling disengagement or gameplaying consider their goals more worthy, sometimes even more moral than those of the authority.

Trust Building Pathways Revealed Through Postures

Motivational postures provide a nuanced way of understanding trust building. If a third party shares with the authority the mission of commitment to ensure children are safe and cared for, child protection decisions that trigger poor alignment with one’s moral self could be resolved through evidence-based dialogue about what is right and what is best. Sharing contextual knowledge may be important. Child protection authorities need to be open to criticism and having their worldview challenged if they are to proceed down the path of relational repair and earned trustworthiness. Even if differences remain, having an appreciation of the other’s moral compass is beneficial for both parties if they are to continue to have dealings with each other.

If a third party is disturbed by misalignment between her justice self and the child protection authority’s processes, the third party is likely to signal resistance rather than capitulation. Trust building then demands dialogue around why decisions and actions do not seem fair. The processes need to change to prevent reoccurrence. In this way, a trust relationship can be revived with resistance giving way to capitulation.

If a third party believes that child protection authorities are undermining the achievement of important goals, the signals that are likely to be sent to child protection authorities will be disengagement and gameplaying. Because these postures challenge child protection legitimacy, resolution and trust building may require legal reform, power sharing, or even the institution’s abolition.

Research Questions

The next section uses survey data collected from third parties to answer five questions:

Do Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties express different levels of trust in child protection authorities?

Do Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties express commitment and moral alignment with child protection authorities and do they do so to different degrees?

Do Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties express resistance or capitulation to child protection authorities? Are they engaged in fair decision processes? Are there group differences?

Do Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties express disengagement and gameplaying (dismissive defiance) with child protection authorities, do they feel thwarted in achieving outcomes, and do they do so to different degrees?

The survey was conducted in the latter half of 2010 as the sector was coming to terms with implementing the reforms of the 2009–2020 Framework. These data provide insight into third-party willingness to play their part in the reform process. Previous publications (Braithwaite & Ivec, 2021, 2022) concluded that third-party participants overwhelmingly were supportive of the Framework, but considered child protection authorities ill-equipped to lead change. In this paper, we delve into the views of Indigenous third parties, first through a comparative quantitative analysis and then through an in-depth analysis of Indigenous third parties’ criticisms of the child protection system and vision for change. Post the failed Voice referendum, it is timely to return to Indigenous voices telling of their experiences and what reform needs to deliver to Indigenous communities.

National Survey on Perceptions of How Child Protection Authorities Work

Sample and Design

The survey ran from February to August 2010. It comprised 209 close-ended questions, mainly about ways that child protection systems operated, but also with a demographic module for purposes of sample description. An additional 8 questions allowed for free text responses. Descriptive statistics for the full quantitative survey are available on-line (Ivec et al., 2011).

The web-based survey was completed by 427 participants. The survey was distributed to third parties across Australia, that is, to those who worked alongside or engaged with statutory child protection authorities on a paid or unpaid basis, either inside or outside government. Contact was made through professional and community email networks that the researchers were able to access either directly or indirectly through colleagues. The goal of the survey was to capture as much diversity as possible geographically and occupationally and to do so outside formal workplaces that might inhibit willingness to respond openly. As the project gained momentum, snowballing was encouraged, with survey contacts invited to widen the web by forwarding details to those in other relevant networks.

In order to ensure the sample comprised individuals who had had recent and substantive experience with child protection authorities, six screening questions on the nature of contact with child protection authorities in the past two years were applied to the original data set. The data for analysis were restricted to those who had either intensive or modest contact over a number of cases in the past two years or intensive or modest contact over one case or issue in the past two years. This meant 40 cases were excluded on grounds of having only distant contact or little contact with child protection authorities over the past two years. A final sample of 387 participants was used for the analyses below.

Among the 387 were 29 participants who identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. 25 of the 29 had made extensive use of the open-ended questions in the survey, as well as completing the quantitative survey components. The depth of thought in their qualitative responses was the genesis of this paper.

A breakdown of the sample on social-demographic characteristics is provided in Appendix 1.

Quantitative Measures and Analysis

Details of the measures for this analysis are provided in Appendix 2, including items and psychometric statistics.Footnote 19 Multi-item scales were constructed to measure:

-

a)

Trust (sample item: Child protection authorities can be relied on to do what they say they will do).

-

b)

Commitment posture (sample item: I am committed to ensuring that children and families access the support they need to prevent harm and promote safety).

-

c)

Capitulation posture (sample item: The child protection system may not be perfect, but it works well enough for most of us).

-

d)

Resistance posture (sample item: Child protection authorities are more concerned about making their own job easier than making things easier for others).

-

e)

Disengagement posture (sample item: If I find out that I am not doing what child protection authorities want, I’m not going to lose any sleep over it).

-

f)

Gameplaying posture (sample item: I will tick the boxes to please a child protection authority and make the paperwork look good, but I will not do anything else to help them).

-

g)

Reform implementation (sample item: Child protection is using out-of-home care as the last resort).

-

h)

Collective efficacy (sample item: Third parties can help both child protection workers and families bridge their differences).

-

i)

Engagement with families and third parties (sample items for engagement: How well do child protection authorities engage with families? How well do child protection authorities engage with NGOs and other services they deal with?)

-

j)

Ritualism (sample item: Child protection workers mechanically follow processes and ignore outcomes).

Independent t-tests were calculated to compare Aboriginal and non-Indigenous groups on the trust scale, the motivational postures scales, and the scales to measure likely misalignments of child protection authorities with the moral, justice and achievement sensibilities of third parties.Footnote 20

Quantitative Findings

Do Aboriginal and Non-Indigenous Third Parties Express Different Levels of Trust in Child Protection Authorities?

From Table 1, Aboriginal third parties had a significantly more negative view than non-Indigenous third parties on child protection trustworthiness (M = 2.32 compared with M = 2.70). Of note is that on a five-point scale where 1 is low trust and 5 is high trust; the mean score for both groups was below the midpoint of 3. Both groups placed child protection authorities on the low end of the trust continuum.

Do Aboriginal and Non-Indigenous Third Parties Express Different Levels of Commitment and Moral Alignment with Child Protection Authorities?

From Table 1, the posture of commitment to doing child protection work to protect children was very strong in both groups with no significant difference between them. On a five-point rating scale where 5 is the highest possible score, the means were 4.62 for the Aboriginal group and 4.56 for the non-Indigenous group.

Consistent with strong commitment to protect children was confidence that third parties could make a difference through supporting families, particularly in their dealings with child protection. The mean collective efficacy for the Aboriginal groups was 3.79 and 3.59 for the non-Indigenous group. The difference was not significant.

While morally aligned with the mission of keeping children safe and being confident in their support roles, both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous groups rated child protection poorly on their performance in implementing agreed upon reforms associated with child removals, family reunification, evidence-based practice and interventions. From Table 1, Aboriginal third parties were significantly more critical with a lower mean of 3.22 on a 1 to 7 rating scale compared with 3.73 for the non-Indigenous group. This is not a surprising finding given higher levels of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care.

The most important contribution of these findings is the nuance they bring to conversations for relational repair and consensus for reforms toward relational care. Even though the first trust analysis revealed low trust between third parties and child protection authorities, this second analysis reveals valuable common purpose for co-designing implementation of the reforms and working through differences. Strong commitment to the mission of child protection authorities to keep children safe and thriving provides common ground for conversation. Shared criticisms expressed by Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties around mission performance—even though this was significantly stronger for Aboriginal groups around child removal and family re-unification—provide direction for collaborative problem-solving with child protection authorities. Importantly, non-Indigenous third parties experienced child protection authority in similar ways to Aboriginal third parties. Non-Indigenous and Aboriginal third parties shared common ground for pushing for reform.

Do Aboriginal and Non-Indigenous Third Parties Express Different Levels of Resistance and Capitulation to Child Protection Authorities and Do They Vary in Their Perceptions of Fair, Engaged Decision Processes?

Resistance means in Table 1 are above the midpoint of the 1 to 5 Likert rating scale for Aboriginal (M = 3.71) and non-Indigenous third parties (M = 3.10). Resistance was significantly greater for the Aboriginal group.

From Table 1, both groups scored below the midpoint of the 1 to 5 scale on capitulation (M = 2.75 for the Aboriginal group compared with M = 2.92 for the non-Indigenous group). The means were not significantly different.

Through comparing means in Table 1, the posture of resistance is stronger than the posture of capitulation in both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous groups. A posture of resistance is democratically healthy—it is the litmus test for government that something is not working as it should for the majority of the population. Low capitulation means that both the Aboriginal and non-Indigenous groups are signalling that they disagree with the authority’s views of what is best. When capitulation (thinking government knows best) is at levels below resistance, we gain insight into why Australia has had over 40 government inquiries into child protection systems (Lonne et al., 2013).

Child protection authorities were perceived as performing poorly on engagement, with Aboriginal third parties being significantly more negative in their evaluation than non-Indigenous third parties (on a 1 to 7 rating scale, M = 2.64 for the Aboriginal group compared with M = 3.10 for the non-Indigenous group). The message was that child protection authorities did not listen to families or third parties, used coercive measures without enough consultation, and made decisions without appropriate understanding of the situation.

High resistance, low capitulation and poor engagement point to a relational problem between third parties and child protection authorities that needs repair. Dissatisfaction is particularly acute among Aboriginal third parties.

Do Aboriginal and Non-Indigenous Third Parties Express Different Levels of Disengagement and Gameplaying (Dismissive Defiance) with Child Protection Authorities and Do They Feel Thwarted in Achieving Their Goals?

From Table 1, the mean scores for disengagement for both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties are low and not significantly different (on a five-point scale, M = 2.62 for the Aboriginal group compared with M = 2.44 for the non-Indigenous group).

Similarly, the posture of gameplaying is low for both groups (on a 1 to 5 rating scale, M = 2.36 for the Aboriginal group compared with M = 1.97 for the non-Indigenous group). There was a significant difference on gameplaying with non-Indigenous third parties significantly less likely to game play with child protection authorities.

These findings should be interpreted against the backdrop of strong commitment and collective efficacy in advancing the reform process. Disengagement and gameplaying involve dismissive defiance, that is, stepping outside the system of control. But third parties were committed to reform and in this way were tied into the system to varying degrees.

The tendency for Aboriginal third parties to entertain gameplaying is of interest. This may simply reflect the contractual arrangements that bind non-Indigenous third parties more tightly to child protection authorities and government service delivery more generally. Alternatively, Aboriginal third parties may be expressing a modicum of dismissive defiance.

Consistent with this interpretation is reported frustration with the system for failing to execute a plan to achieve desirable outcomes. From Table 1, both Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties scored above the midpoint of 3 on the 1 to 5 rating scale on child protection’s ritualism (M = 3.44 for the Aboriginal group compared with M = 3.10 for the non-Indigenous group). In other words, third parties agreed that child protection authorities functioned in a ritualistic manner, following rules and protocols, at times coercively, all the while failing to consider outcomes and losing sight of the main goal of keeping children safe. The Aboriginal group observed significantly higher levels of ritualism than the non-Indigenous group.

Summary of Quantitative Findings

Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties shared frustration at the obstacles child protection authorities placed in their path by ignoring Framework principles, clinging to ritualistic ways of operating, and failing to engage appropriately. Low trust and high resistance to the authorities characterised both groups. But their commitment to having a child protection system was high as was commitment to their roles.

In spite of their similarities, differences emerged in the strength of Aboriginal third parties’ disapproval. Aboriginal third parties felt injustice more keenly and were more critical of child protection’s persistent ritualism and mission failure around engagement and reform implementation.

Consistent with this disapproval, Aboriginal third parties expressed greater resistance, lower trust and were more open to gameplaying. The potentially ungovernable state of dismissive defiance, however, was tempered it would seem by strong commitment to children and families and confidence in their capacity to do their job well.

The free text responses provided by 25 of the 29 Aboriginal third parties who took part in the survey provide a better understanding of the grounds for shared resistance, a modicum of gameplaying along with overarching commitment to a reformed child protection system. The voices of all 25 participants are not recorded below, but the voices that are presented were representative of the group, unless otherwise indicated.Footnote 21

Qualitative Survey Responses from Aboriginal Third Parties

The views of 25 of the 29 Aboriginal third parties who took part in the survey provide evidence of a conception of self-determination in child protection that has been thoughtfully developed over more than a decade, that is without doubt based on negative experience, but that is driven by a spirit of partnership not segregation.

All but one of the respondents spoke of institutional racism in the child protection system. The descriptions varied:

our families with children are instantly ‘labelled’ as possibly potentials … staff are very quick to judge how a family is coping by their dress standards, language, smell and how they are presenting at the time (hospital acute care health worker).

more often than not, child protection workers devalue the indigenous family and community structure (foster carer and coordinator).

Child protection authorities’ lack of respect for and dismissiveness of the commitment of Aboriginal third parties was also a common theme:

Notifications have been made and possible removal without consultation with Aboriginal workers or the family to identify alternative relative care options (hospital acute care health worker).

The Aboriginal Family Decision Making program … works well if the [child protection] worker is willing to trust advice from Indigenous workers involved and not discredit them by assuming they are not professional and will collude with the family (program manager).

Along with feelings of racism and disrespect was clear-sightedness about what needed to be done to improve the child protection system. Knowing what should be done likely fuelled third party’s resistance, maybe even gameplaying. One support worker provided a list of necessary services, another looked to Elders as role models:

1. Specific services dedicated to support and advocate the needs of parents and families, and to ensure that actions taken by [child protection] workers are based on evidence rather than assumption/in crisis. 2. An external body that governs the actions of [child protection] workers. 3. Compulsory use of Family Group Conferencing. 4. Learn from past errors resulting in the ‘Stolen Generations’ and the ‘Forgotten Australians and ensure these mistakes aren’t repeated. Currently they are being [repeated]!!

In most Aboriginal families, it’s the Nannys that are on-call care-workers 24 hours for their grandchildren, with often very little support, no transport, and quite often overcrowding overnight arrangements. The 24 Hours Aboriginal Nanny care has limited funding and is based on the Aboriginal Value System of Caring for Country. The benefits that an Aboriginal Nanny receives are much Love, Joy, Laughter, Companionship, Humour and a student to pass on knowledge of Language, Culture and Stories. The Aboriginal Nanny is a true hero (family support worker, currently training to be a child focus educator in an Aboriginal service).

The program manager, quoted above, provided this story of ritualistic practices by child protection workers that undermined the achievements of her staff and community and led to legal decisions that endangered the child. The case involved a 12-year-old boy who was physically abused by his step-father and almost lost sight in one eye:

There was an extensive history of abuse and substance abuse in the family. … a child and his younger sibling had not been collected from school. … The school had been told by the [child protection] worker involved that even though the mother was stating (in a very drunken manner) to keep the ‘f…. kids’, this did not constitute grounds for a notification. We picked the children up and put them in our Family Group Home for the night for their care and protection, against the [child protection authority] telling us to take them home. We were then ordered to take the children to the child protection office (6 pm) and let them take them home …[The child protection authority] completely disregarded our community knowledge, the knowledge of the school workers and made a decision based on this being OK or normal for Indigenous families. Within two weeks the stepfather had caused the injuries to the eye mentioned above. When the case went to court the Magistrate accepted that the Tongan culture of the stepfather was to severely beat children when they ‘misbehaved’ and left the children in the care of the family.

The qualitative data provided by Aboriginal third parties revealed awareness of the need for a well-functioning interface between child protection and the legal system and not separation from the system:

I’ve been involved in many cases where due to safety issues, the child must go into care (either relative or foster), but with legal representation the Department will adhere to regular visits/help with transport etc.etc. … Without legal representation, the child will basically go into care and vanish … The use of lawyers in legal aid/Aboriginal legal services DOES keep system much more accountable (therapist).

Improvements could be obtained if the entire system was overhauled … the legal system needs to be better able to work in the best interests of the child rather than scoring points and winning cases against other legal practitioners; Magistrates need to be better trained to take the best interests of the child into consideration rather than a very narrow ‘keep the family together at all costs’ mentality; courts need to be able to take on board community knowledge to build a better picture of the situation rather than simply relying on which solicitor presents the best case… families need to be better educated about their responsibilities as parents/carers and early intervention programs that have ‘teeth’ put into place as soon as an issue involving the care of a child is noticed (program manager).

Aboriginal third parties were not in conflict with the moral purpose of child protection authorities, only with the formal system’s ritualism and failure to engage appropriately:

I would like to say that the majority of child protection workers would like the opportunity to work proactively in more preventative programs but the [child protection] agencies still operate on a [reactive] model which obviously doesn’t and can’t work. If it did work notifications would be declining instead of sky rocketing. Give the workers the opportunity to use judgement and provide them with alternatives to removal (community health worker).

One police officer was critical of child protection workers’ lack of confidence with policy that was designed to benefit Aboriginal children:

Perhaps understandably, Community Services has a guilt-driven approach to developing policy and practice for Aboriginal child protection. For good reason, policy encourages cultural sensitivity and relationship building with communities. Unfortunately, in some practical senses, it is too cautious about causing offence or attracting criticism of being paternalistic. Policy and practice avoid intervention in some types of cases where the protection of the child certainly justifies more intrusive intervention (police investigator).

The experiences of racism, disrespect, harmful outcomes for children, ritualism and ignorance in the child protection and legal systems as well as commitment to empirically supported practices to keep children safe underpin arguments for self-determination. Self-determination was explicitly the objective of the following survey respondent:

Government authorities are not the only decision makers in this country. Other sectors can be responsible for making decisions for children and young people. I firmly believe this would work well as well as being financially clever….. For me the solution rests with our own people and we should be enabled to continue to build our workforce throughout the country instead of being dictated to by government—there have been no tangible nor decent outcomes for our children in the past generations, yet still we are consistently mocked and ridiculed and must forever bow to the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon in this country (advocate and foster care coordinator).

Discussion

This article takes a long view of how third parties, particularly Aboriginal third parties, framed their expectations as Australia’s national reform program got underway in 2009. The dominant zeitgeist for surveys intended to inform policy is to measure public opinion at a particular point in time to gauge the popularity of a policy, a government, or a leader, often with the intention of developing a campaign strategy to increase support. The purpose of this study is different. It seeks to shed light on how third parties positioned themselves vis-à-vis child protection authorities as governments made commitments that they could not keep, at least not in the decade that was to follow.

This article argues that relational repair is needed because promises were broken and because Aboriginal third parties, in particular, have not seen ‘care’ in the way policy is implemented. A promotional campaign will not repair the damage described in this article. Government authorities need to understand the ways in which they have disappointed affected communities over a longer time span. This article recognises a history of poor child protection outcomes that is continuing, particularly for Aboriginal children, and turns the clock back to criticisms and expectations expressed by Aboriginal third parties at the time of the launch of the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children. The intention is to identify deep disappointments and institutional obstacles to change. This is where relational repair must start. What is done in the future depends on revisiting the past and rejecting unhelpful institutional dependencies that hinder reform.

What Does the Data Tell Us?

The quantitative data revealed similarities in the experiences of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties. But differences also emerged that substantiated greater offence and frustration for Aboriginal third parties. The qualitative data from Aboriginal third parties shed light on the depth and breadth of the offence they felt, their frustration at failure to implement evidence-based practice, and their determination to find a way of helping their communities. Offence was felt at the level of the moral self. Child protection was not doing the right thing, and yet made the decisions that affected children and families. Offence was also taken at the level of the justice self. The knowledge and expertise of third parties were discounted, and efforts were not made to consult or include them in decisions or engage with them or families in a positive way. The achievement self that was driving third parties to meaningfully contribute through their work was thwarted by a powerful authority that had lost sight of the needs of children, families, and communities.

Policies have been in place for Aboriginal self-determination in child protection for more than a decade, but implementation can best be described as timid and patchy, at worst, ignored. As participants in this survey foresaw, there are major obstacles to power sharing: institutional racism that can be traced back to child protection being a colonial institution, detached, and bureaucratic and ritualistic procedures that deny child protection a human face, that entrench poor engagement with families and third parties, and that shield child protection authorities from reforming their processes in consultation with others. This article provides insights into how reform might be progressed through ‘Birdiya with Birdiya’ or ‘boss with boss’ (Hamilton et al., 2022) conversations that recognise these obstacles and negotiate a path forward. Before discussing implications, limitations of the study need to be considered.

Limitations

The degree to which third-party participants in this survey are representative of the population of third parties in Australia is unknown. Seeking diversity of voices was prioritised over systematically sampling of occupational groups, for example those supporting families dealing with domestic violence or substance misuse (see, for example Coates, 2017; Humphreys et al., 2018).

Writing this article was prompted by the failed Voice referendum and the voices of Aboriginal third parties from the 2010 survey. When the survey was undertaken, there was no expectation that 25 of 29 Aboriginal third parties would contribute their thinking so frankly and generously on the future of child protection in Aboriginal communities. In retrospect, their qualitative responses were prescient, thoughtful and well-considered and worthy of reflection in 2024. Without doubt, further systematic investigation is warranted of the shared and differing visions of Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties for child protection reform post the referendum. Future work would cast light on whether the more threatening postures of gameplaying and disengagement have crowded out the more relationally responsive posture of resistance over the elapsed time.Footnote 22 In the circumstances, it is unlikely that these defiant postures have faded away completely. At the same time, knowledge that Aboriginal and non-Indigenous third parties shared criticisms of child protection authorities is important in planning future work: They were not divided and they were united in their commitment to a well-functioning child protection system.

Implications

Institutional racism and colonial supremacy have created disquiet in the aftermath of the failed referendum on Voice. The findings of this article contribute to how we might constructively engage with our collective unease. In one sense, the findings are liberating. The quotes from Aboriginal third parties on child protection and the courts being ‘guilt-driven’ or too cautious in intervening with Aboriginal families when a child is unsafe are informative. Scholars debate the question of when institutional racism is in play or when it is the case that parents’ struggles to survive flow into inadequate care for children (Cénat et al., 2021). The voices of Aboriginal third parties in this study had no difficulty entertaining both realities: They confronted institutional racism routinely, but that did not mean they were unable to recognise and call out unacceptable parenting. Ironically, this was a problem faced more acutely by the colonisers in the qualitative data. Case conversations between mainstream child protection workers and Aboriginal third parties may well educate and liberate decision-making for the better.

Conversations seem such simple things to have over matters of importance. But so often, time constraints result in open conversations being supplanted by formal meetings with overly structured plans and templates for problem definition and analysis. Conversations on matters of substance may be avoided by child protection authorities because they are uncontrollable, unpredictable and time-consuming, even dangerous.

The message from this research is that conversations with third parties over their differences need not be as dangerous as authorities may think. Aboriginal practices of yarning come to mind as a conversational style that should be comfortable for child protection authorities and appreciated by families, their support networks and Elders (Hamilton et al., 2022, 2020a, b). The findings that commitment, collective efficacy and resistance were high while dismissive defiance (disengagement and gameplaying) was low indicate that third parties, like child protection authorities, want a system that works for children and families and are willing to engage constructively in reforming the system. This appeared to be the case before the referendum. There is no evidence that this commitment has changed after the referendum, although child protection authorities will likely need to make some effort to connect with Aboriginal good will.

The findings of this study, when set alongside current data on child protection outcomes, highlight the benefits (as opposed to the risks) of child protection authorities empowering third parties, communities of support and families to play a much greater role in developing plans to keep children safe and thriving (Melton & McLeigh, 2020). Creating space for community-led interventions does not mean adopting an abolitionist stance toward child protection authorities. Authorities have other important work to do. They have a role in monitoring the plans that are being developed for children and ensuring the voice of the child is heard. Developing practices that place the voice of children at the centre of deliberations is relatively new territory (McCafferty & Garcia, 2023). Child protection authorities can strategically lead the process of empowering children and disseminating stories of local success across jurisdictions.

Child protection authorities’ other essential service is working collaboratively with police when children are victims of crime. A responsive regulatory approach to child protection, as proposed by Harris (2011) and Hamilton et al. (2022), recognises the responsibility of child protection authorities to be present when community capacity for providing care breaks down. A skilled practitioner hopefully can restore the care circle around a child and strengthen the community network doing the protective work. But the state retains responsibility for care of children who find themselves unsafe and alone.

The most difficult conversations, however, are not around the role of the state, as the high commitment posture scores show. Difficult conversations undoubtedly will be around institutional racism and colonial supremacy, given the outcome of the referendum. The findings presented in this article support approaching these issues through broader reconciliation conversations: The voices of Aboriginal third parties revealed awareness of broader aspirations for social reform. Five dimensions of reconciliation for Australia have been identified as race relations, equality and equity, institutional integrity, unity and historical acceptance.Footnote 23 Self-determination on Aboriginal child protection is part of the reconciliation agenda. That does not mean, however, that child protection authorities should not take the initiative to pave the way for reform through four practicable, reasonable and safe actions. Action 1 is Listening to Families, Elders and Third Parties. Action 2 is Relational Integrity, demonstrating care, turning up on country, and speaking honestly and respectfully. Action 3 is Asking ‘How Can We Help?’ Action 4 is Making Help Happen. These four actions address child protection’s documented weaknesses, echo major reviews in the field (for example Munro, 2011), and cover a lot of the behaviours required for relational repair and building trust—fair, dependable, honest, concerned, and responsive to expectations and goals (Borum, 2010)—in readiness for self-determination. Non-Indigenous third parties would welcome such initiative as well.

Ritualism, rulishness, and siloed decision-making that support the ‘go-to’ policy of child removal are likely to be challenging for child protection authorities because they reflect path dependencies that have been generations in the making. But Aboriginal self-determination, if respected as an alternative way of doing child protection work, creates a barrier against the intrusiveness of past colonial practices. We do well to recall the survey respondent who considered that the system made child protection workers operate contrary to how they preferred to operate. The literature tends to support this view (Krumer-Nevo, 2020; Lonne et al., 2013; Marsh et al., 2015; Stahlschmidt et al., 2022). Through supporting and learning new child protection practices from Aboriginal third parties, the beliefs underpinning the edifice of child protection may be challenged sufficiently to make way for a relational care ethic to take hold to benefit everyone. The ‘Birdiya with Birdiya’ or ‘boss with boss’ approach (Hamilton et al., 2022) maps out an interactive and productive interface between child protection authorities and Aboriginal organisations. Both need time with each other and space for reflection to develop a new paradigm that allows two different types of cultural institutions to meet and collaborate to keep children safe and thriving.

Data Availability

Data can be made available on request to senior author.

Notes

Aboriginal will be used henceforth to refer to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Between 1997 and1999, state governments and the federal government responded with acknowledgment and apology on the release of the bringing them Home Report: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/projects/bringing-them-home-apologies-state-and-territory-parliaments-2008

Recommendation 7.111 of the Forgotten Australians Report was that all states and Churches and agencies that had not already issued an acknowledgment and apology should do so. Some state governments and providers of institutional care have apologised to the Forgotten Australians and some have offered redress schemes.

All states have offered apologies to women and children affected by forced adoptions: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/FlagPost/2013/March/National_Forced_Adoptions_Apology

For example, see special projects in Victoria https://www.cfecfw.asn.au/voice-of-parents/ and South Australia, https://www.childprotection.sa.gov.au/news/dcp-news2/families-to-be-formally-heard

Commonwealth of Australia (2023) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Action Plan 2023–2026 under Safe and Supported: The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2021–2031, p.10.

See Lorena Allam for a discussion of the rejection experienced by Aboriginal Australians the day after the referendum failed. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/commentisfree/2023/oct/14/rejecting-the-voice-shows-australia-is-still-in-denial-its-history-of-forgetting-a-festering-wrong

‘Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.’ From the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the First Nations National Constitution Convention 2017.

This conference brought together an almost 2000 strong community of practice from around the world, October 2–5, 2023. Panels that inspired this paper included Family Rights Group UK (Chair: Angela Frazer-Wicks), Parent Advocacy from a Social Justice Lens (Chair: Jessica Cocks) and Relational Health and Family Group Conference (Chair: Paul Nixon).

Parent Advocacy from a Social Justice Lens (Chair: Jessica Cocks), session at Kempe International Conference, 32.36 min into recording.

Parent Advocacy from a Social Justice Lens (Chair: Jessica Cocks), session at Kempe International Conference, 17.26 min into recording.

We first learn to posture with our mothers and carers. They come into play whenever power is exercised over us.

Motivational postures have been used in contexts as varied as prisons, hospitals, nursing homes, taxation, regulating environmental use, policing and peacebuilding.

Although the groups were of different size (29 in the Aboriginal group compared with 355 in the non-Indigenous group), the variances were not statistically different, thus making independent t-tests appropriate. A sample size of 30 is normally preferred so that there are enough cases to generate a normally distributed sampling distribution. To ensure that the sample of 29 was not producing misleading statistical results, confirmation of the results was obtained using Mann–Whitney U tests as a non-parametric test of difference between independent groups with reference to continuous, non-normally distributed variables. The scale means (and the t-tests for those means) are reported here because of their interpretive benefits.

The complete qualitative data set is available upon request.

References

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) (2023). Child Protection Australia 2021–22. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2021-22/contents/about

Arney, F., Iannos, M., Chong, A., McDougall, S., & Parkinson, S. (2015). Enhancing the implementation of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Placement Principle: Policy and practice considerations (CFCA Paper No. 34). Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia information exchange. https://aifs.gov.au/resources/policy-and-practice-papers/enhancing-implementation-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander. Accessed 8 May 2024

Australian Centre for Child Protection (2020). Response to the Parliament of New South Wales Committee on Children and Young People inquiry into child protection and social services system, Submission 50. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/committees/inquiries/Pages/inquiry-details.aspx?pk=2620#tab-submissions

Australian Human Rights Commission. (1997). Bringing them home : Report of the national inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/projects/bringing-them-home-report-1997. Accessed 8 May 2024

Borum, R. (2010). The science of interpersonal trust, Mental Health Law and Policy Faculty Publications, 574. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/mhlp_facpub/574

Braithwaite, V. (1998). Communal and exchange trust norms: Their value base and relevance to institutional trust. In V. Braithwaite & M. Levi (Eds.), Trust and governance (pp. 46–74). Russell Sage Foundation.

Braithwaite, V. (2009). Defiance in taxation and governance: Resisting and dismissing authority in a democracy. Edward Elgar.

Braithwaite, V. (2021a). Institutional oppression that silences child protection reform. International Journal on Child Maltreatment, 4(1), 49–71.

Braithwaite, V. (2021b). Understanding and managing trust norms. International Journal for Court Administration, 12(3), 2.

Braithwaite, V., & Ivec, M. (2022). Policing child protection: Motivational postures of contesting third parties. Asian Journal of Criminology, 17, 425–448.

Braithwaite, V. & Ivec, M. (2021). National framework for protecting Australia’s children: Fixing problems with collective hope? Regulation and Social Capital Working Paper 2, School of Regulation and Global Governance (RegNet), Australian National University. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4202707

Broadhurst, K., & Mason, C. (2013). Maternal outcasts: Raising the profile of women who are vulnerable to successive, compulsory removals of their children–a plea for preventative action. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 35(3), 291–304.

Buckley, H., Carr, N., & Whelan, S. (2011). ‘Like walking on eggshells’: Service user views and expectations of the child protection system. Child and Family Social Work, 16(1), 101–110.

Burford, G., Braithwaite, J., & Braithwaite, V. (2019). Restorative and responsive human services. Routledge.

Burford, G., & Pennell, J. (1998). Family group decision making project: Outcome report, Vol. I. St. John's, Newfoundland: Memorial University.

Cashmore, J. (2011). The link between child maltreatment and adolescent offending: Systems neglect of adolescents. Family Matters, 89, 31–41. https://aifs.gov.au/research/family-matters/no-89/link-between-child-maltreatment-and-adolescent-offending. Accessed 8 May 2024

Cénat, J., McIntee, S., Mukunzi, J., & Noorishad, P. (2021). Overrepresentation of Black children in the child welfare system: A systematic review to understand and better act. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105714.

Chase, Y. E., & Ullrich, J. S. (2022). A connectedness framework: Breaking the cycle of child removal for black and indigenous children. International Journal on Child Maltreatment, 5, 181–195.

Coates, D. (2017). Working with families with parental mental health and/or drug and alcohol issues where there are child protection concerns: Inter-agency collaboration. Child and Family Social Work, 22, 1–10.

Council of Australian Governments. (2009). Protecting children is everyone’s business : National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020 : An initiative of the Council of Australian Governments. Canberra, A.C.T : Dept. of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Accessed 11 November 2022, https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/pac_annual_rpt_0.pdf

Davis, M. (2019). Family is culture, independent review into Aboriginal out-of-home- care in NSW. Sydney, New South Wales: Department of Family and Community Services.

Department of Social Services. (2020). Evaluation of the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020. Canberra: Australian Government. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/11_2020/evaluation-national-framework-pwc-report-12-july-2020-updated-oct-2020.pdf

Department of Social Services. (2021). Safe and supported: the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2021–2031. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Accessed 15 July 2023, https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/families-and-children/programs-services/protecting-australias-children

Dettlaff, A. J., Weber, K., Pendelton, M., Boyd, R., Bettencourt, B., & Burton, L. (2020). It is not a broken system, it is a system that needs to be broken: The upEND movement to abolish the child welfare system. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(5), 500–517.

Featherstone, B., Gupta, A., Morris, K., & White, S. (2018). Protecting children: A social model. Policy Press.

Hamilton, S., Cleland, D., & Braithwaite, V. (2020a). ‘Why can’t we help protect children too?’ Stigma by association among community workers in child protection and its consequences. Community Development Journal, 55(3), 452–472.

Hamilton, S. L., Maslen, S., Best, D., Freeman, J., O’Donnell, M., Reibel, T., Mutch, R., & Watkins, R. (2020b). Putting ‘justice’ in recovery capital: Yarning about hopes and futures with young people in detention. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 9(2), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i2.1256

Hamilton, S., Maslen, S., Farrant, B., Ilich, N., & Michie, C. (2022). ‘We don’t want you to come in and make a decision for us’: Traversing cultural authority and responsive regulation in Australian child protection systems. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 57(2), 236–251.

Hamilton, S. & Braithwaite, V. (2014). Complex lives, complex needs, complex service systems, Regulatory Institutions Network Occasional Paper 21, Australian National University. Accessed 11 November, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/155691/1/Occasional_Paper21_Hamilton%26Braithwaite.pdf

Harris, N. (2011). Does responsive regulation offer an alternative? Questioning the role of formalistic assessment in child protection investigations. British Journal of Social Work, 41(7), 1383–1403.

Harris, N. (2012). Assessment: When does it help and when does it hinder? Parents’ experiences of the assessment process. Child and Family Social Work, 17(2), 180–191.

Harris, N., & Gosnell, L. (2012). From the perspective of parents: Interviews following a child protection investigation. Regulatory Institutions Network Occasional Paper 21. Canberra: Australian National University. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/155688/1/FromthePerspectiveofParents.pdf

Holland, S. (2014). Trust in the community: Understanding the relationship between formal, semi-formal and informal child safeguarding in a local neighbourhood. British Journal of Social Work, 44(2), 384–400.

Humphreys, C., Healey, L., Kirkwood, D., & Nicholson, D. (2018). Children living with domestic violence: A differential response through multi-agency collaboration. Australian Social Work, 71(2), 162–174.

Ivec, M., Braithwaite, V., & Harris, N. (2012). “Resetting the relationship” in Indigenous child protection: Public hope and private reality. Law & Policy, 34(1), 80–103.

Ivec, M., Braithwaite, V. & Reinhart, M. (2011). A national survey on perceptions of how child protection authorities work 2010: The perspective of third parties – Preliminary findings. Regulatory Institutions Network Occasional Paper 16, Australian National University. Accessed 11 November 2023, https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/155686

Keddell, E. (2019). Algorithmic justice in child protection: Statistical fairness, social Justice and the implications for practice. Social Sciences, 8, 281. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8100281

Krugman, R. D., & Korbin, J. E. (2023). Lessons for child protection moving forward: How to keep from rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. International Journal on Child Maltreatment, 6, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-023-00148-x

Krumer-Nevo, M. (2020). Radical hope: Poverty-aware practice for social work. Policy Press.

Lalayants, M., & Merkel-Holguin, L. (2023). Adapting private family time in child protective services decision-making processes. Child & Family Social Work, 28, 723–733.

Lonne, R., Parton, N., Thomson, J., & Harries, M. (2008). Reforming child protection. Routledge.

Lonne, B., Harries, M., & Lantz, S. (2013). Workforce development: A pathway to reforming child protection systems in Australia. British Journal of Social Work, 43(8), 1630–1648.

MacAlister, J. (2022). The independent review of children’s social care final report. U.K. Government. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-final-report. Accessed 8 May 2024

Malvaso, C., Montgomerie, A., Pilkington, R. M., Baker, E., & Lynch, J. W. (2022). Examining the intersection of child protection and public housing: Development, health and justice outcomes using linked administrative data. British Medical Journal Open, 12, e057284. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057284

Marsh, C. A., Browne, J., Taylor, J., & Davis, D. (2015). Guilty until proven innocent? – The assumption of care of a baby at birth. Women and Birth, 28, 65–70.

Maslin, S., & Hamilton, S. (2020). ‘Can you sleep tonight knowing that child is going to be safe?’: Australian community organisation risk work in child protection practice. Health, Risk and Society, 22(5–6), 346–361.

Mason, C., Taggart, D., & Broadhurst, K. (2020). Parental non-engagement within child protection services—How can understandings of complex trauma and epistemic trust help? Societies, 10(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc10040093

McCafferty, P., & Garcia, E. (2023). Children’s participation in child welfare: A systematic review of systematic reviews. The British Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad167

McConnell, D., & Llewellyn, G. (2005). Social inequality, “the deviant parent” and child protection practice. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 40(4), 553–566.

Melton, G. B., & McLeigh, J. D. (2020). The nature, logic, and significance of strong communities for children. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice, 3, 125–161.

Merkel-Holguin, L., Drury, I., Gibley-Reed, C., Lara, A., Jihad, M., Grint, K., & Marlowe, K. (2022). Structures of oppression in the U.S. child welfare system: Reflections on administrative barriers to equity. Societies, 12, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010026

Merritt, D. H. (2020). How do families experience and interact with CPS? Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 692, 203–226.

Morley, C., Clarke, J., Leggatt-Cook, C., & Shkalla, D. (2022). Can a paradigm shift from risk management to critical reflection improve child-inclusive practice? Societies, 12, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc12010001