Abstract

Most children in foster care have poor health outcomes and high health care utilization. Health complexity influences health care utilization as well foster care placement. Health care utilization studies among children in foster care have not accounted for health complexity status and foster placement. A 7-year retrospective study linked Colorado child welfare and Medicaid administrative data for 30,164 Medicaid-enrolled children, up to 23 years old, who differed by initial foster care entry, to examine primary care and behavioral health (BH) utilization patterns from 2014 to 2021. Children entering care were matched with replacement to non-foster peers by age, sex, Medicaid enrollment patterns, managed care status, family income, and health complexity. We calculated weighted monthly average percentages of children with primary care and BH utilization by foster care entry, health complexity, sex, and age over 25 months relative to the month of foster care entry for the foster cohort or the reference month for non-foster peers. Children in the foster cohort had lower primary care but higher BH utilization relative to non-foster peers prior to the reference month. Primary care and BH use increased among children in foster care during and 12 months after the reference month, unlike matched comparisons. Primary care and BH utilization increased by health complexity but differed by foster care status and time. Foster care entry and health complexity produced distinct patterns of primary care and BH utilization. Given higher utilization among children in foster care, future investigation should explore health care quality and delivery factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

Despite efforts to prevent child abuse and neglect and reduce out-of-home placement through family preservation services, each year approximately 400,000 children are in foster care in the USA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2022a). Foster care is common; more than 6% of US children enter foster care prior to their 18th birthday (Wildeman & Emanuel, 2014). Although meant to be temporary, nearly two-thirds of children remain in foster care for 12 months or longer (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2021). While most children enter foster care due to abuse or neglect, substantial percentages of foster care entries are for reasons unrelated to maltreatment including parental incarceration or death and child physical and mental health problems that exceed parental capacities (Christian & Schwarz, 2011; Drake et al., 2021; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2021).

Children in foster care have greater physical and mental health needs and worse health outcomes compared to children in the general population (“non-foster peers”) (Chaiyachati et al., 2020; Lansford et al., 2021; Reilly, 2003; Stein et al., 2013; Szilagyi et al., 2015; Turney & Wildeman, 2016). Among children in foster care, up to 80% have a physical (Halfon et al., 1995) or a mental health condition (Engler et al., 2020) , and 50% to 70% have a chronic health condition (Lynch et al., 2021; Ringeisen et al., 2008). Health care use and health care costs are higher for children in foster care (Becker et al., 2006; Bennett et al., 2019; Florence et al., 2013). Greater health care use may reflect health need; the prevalence of special health care needs among the foster population is double the rate among non-foster peers (Bilaver et al., 2020; Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative; Sepulveda et al., 2020).

These health disparities can be exacerbated when appropriate, high-quality health services are insufficient or delayed (Edwards et al., 2021; Felitti et al., 1998; Keefe et al., 2020; Rubin et al., 2007; Sedlak et al., 2010; Silver J et al., 1999; Simms et al., 2000; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1995). Through recent federal legislative acts and health care reforms, health care and child welfare systems have greater accountability to ensure children in foster care access and receive high-quality health care services (Adoption & Safe Families Act, 1997; Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act, 2008; The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010; Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act, 2011; Bipartisan Budget Act of, 2018). Nearly all US children who enter foster care are eligible for Medicaid coverage (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2022), though state child welfare agencies have the critical responsibility to ensure children in foster care receive initial and ongoing health care including physical, developmental, and mental health services (Social Security Title IV-B, 2015). Unfortunately, there are frequent gaps in delivering health services to children in foster care: nationally, one-third lacked at least one required health screening in a federal review (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, 2015) , and only one-quarter of those with an emotional or a behavioral problem received mental health services within a year (Burns et al., 2004). Comprehensive health care guidelines for children in foster care can assist states’ efforts by outlining enhanced care frequency and necessary medical, developmental, and mental health assessments (Szilagyi et al., 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & Child Welfare League of America, 1988). These recommendations, however, have not been adopted widely in the USA; less than half of child welfare agencies provide comprehensive health evaluations for children entering foster care (Leslie et al., 2003).

Methodological Focus

Recognizing that gaps exist in health care service delivery to children in foster care, methodologically sound studies investigating health care utilization patterns for children in foster care can identify potential solutions and clarify subgroups that experience additional barriers to health care delivery. The influences of placement type and stability (Beal et al., 2022; Rubin et al., 2007) as well as racial and ethnic inequities in health care and child welfare (Fluke et al., 2011; Horwitz et al., 2012; Lane et al., 2002; Maloney et al., 2017; Palusci & Botash, 2021; Wood et al., 2010) are well described in the literature. However, descriptions of varying health care utilization for children in foster care which adjust for health complexity are limited for this population. Incorporating health complexity into research aimed at understanding health care utilization would address an important question: does higher health care use reflects greater health care needs among children in foster care or do patterns originate from health care encounters related to foster care entry (Beal et al., 2022; Lynch et al., 2021)? In this pursuit, methods must include accurate and detailed data sources that unite both health care information and child welfare systems involvement; such sources are valuable but limited. Given the health disparities among children in foster care and the positive health outcomes associated with access to primary care and BH services, understanding utilization trends for these health services according to health complexity may be advantageous for the foster care population (Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary Care, 1996; Mersky et al., 2020; Shi, 2012; Starfield et al., 2005).

In addition to incorporating methods adjusting for health complexity, research should evaluate health care utilization longitudinally both before and after foster care entry. To date, research investigating trends in primary care and BH use among children who will, but have yet to, enter foster care is lacking, and results may differ from non-foster peers by temporal relation to the foster care entry event. Relative to non-foster peers, most research suggests that children in foster care receive more primary care and BH services (Bennett et al., 2019; Florence et al., 2013; Landers et al., 2013; Landers & Zhou, 2004; Rosenbach et al., 1999) . Recent findings, in contrast, report fewer primary care services received among children in foster care compared to non-foster peers (Keefe et al., 2020; Lynch et al., 2021). Prior to care entry, though, little is known about primary care (Friedlaender et al., 2005; Karatekin et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019) and BH use (Leslie et al., 2005) and available data presents mixed results. The contrasting findings may result from prior research focusing on distinct populations by age and by the timing of analysis relative to foster care entry. Within existing literature, for example, two studies examined health care use among children aged 5 years or younger before entry to care (Friedlaender et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019), a third examined use among children, until age 21 years old, following foster care entry (Karatekin et al., 2018) while a fourth, specific to BH use, targeted use for children age 2 to 14 years old over 23 months of child welfare involvement, including foster care entry (Leslie et al., 2005).

As noted above, children who are in foster care have a higher prevalence of chronic and mental health conditions compared to non-foster peers (Ringeisen et al., 2008; Sepulveda et al., 2020) but very little is known regarding primary care utilization trends by foster care and health status over time. Furthermore, researchers’ frequent reliance solely on Medicaid claims data to pinpoint the time of entry into care may contribute to contradictory results as healthcare data is not designed to identify the timing of children’s entry into foster care (Raghavan et al., 2017; Rubin et al., 2005), which is critical to ascertain differences in pre- and post-entry utilization. Therefore, integrated data sources between health care and child welfare systems should be pursued so that both health complexity and trends over time may be studied to generate findings of interest to research, practice, and policy stakeholders and, most importantly, improve health outcomes (Boyd & Scribano, 2021; Jonson-Reid & Drake, 2016; Palinkas et al., 2014).

Current Study

To craft and implement policies and practices that address health disparities and improve health outcomes among children in foster care, health care and child welfare systems need to understand how health complexity and foster care entry impact health care use. The current study addresses prior methodological limitations by examining health care utilization longitudinally according to the initial foster placement and segmenting by health complexity to leverage available information to inform health care and child welfare service design and delivery approaches to match the health needs for children in foster care. A growing body of research demonstrates such investigation is possible through information sharing between health care and child welfare systems (Greiner et al., 2019; Sariaslan et al., 2021). To inform research, policy, and practice for this vulnerable population, accurate and detailed data linkage between health care and child welfare systems would enable longitudinal, population-based health research between children within and outside of foster care to clarify current uncertainty whether health care needs drive increased utilization.

To address these knowledge gaps, we linked 7 years of child welfare and Medicaid administrative data to describe trends in primary care and BH care among a sample of Medicaid-enrolled children by initial foster care entry status overall and by sex, age, and health complexity characteristics. We designed our study to address this need by posing two research questions. First, does primary care utilization differ among Medicaid-enrolled children by initial foster care entry status? Second, does behavioral health utilization differ among Medicaid-enrolled children by initial foster care entry status? For each question, if differences in use were present, we sought to understand how any divergence varied by time before and after foster care entry, by age and sex and by health complexity. It was hypothesized that children who experienced initial entry to foster care would have lower use of primary care and BH services prior to placement and higher utilization of these services following foster care entry based on existing literature (Center for Mental Health Services & Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2013; Johnson et al., 2013; Landers & Zhou, 2004; Rosenbach et al., 1999) . Additionally, it was expected that health complexity status would alter primary care and BH utilization patterns (Bennett et al., 2019). Specifically, utilization patterns were anticipated to increase as health complexity stratification increased from children without chronic or BH conditions to those with concurrent chronic and BH complexity.

Methods

Study Design

This is a population-based, longitudinal observational study of Colorado children/youth enrolled in Medicaid and placed in out-of-home (OOH) care. Primary care and BH utilization among these children/youth are compared to a matched set of Medicaid-enrolled non-foster peers over a 25-month period: 12 months before and 12 months after the month of initial foster care entry for children/youth in OOH care or a reference month for non-foster peers. While existing studies examine primary care and BH use during the 12 months prior to (Friedlaender et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2019) or the 12 months following foster care entry (Burns et al., 2004; Karatekin et al., 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2015), the 25-month analysis is advantageous to describe longitudinal utilization trends relative to foster care entry.

Target Population

The target population for the study is all Medicaid-enrolled children/youth in Colorado with a first entry into extended out-of-home care between January 2014 and March 2021. We defined the first entry into foster care as the child’s first episode of out-of-home (OOH) services that included no breaks in service longer than 2 weeks. The first OOH service span in the episode must be 14 days or longer to count as the beginning of an episode; service gaps shorter than 3 days between two spans are disregarded, and, instead, the two adjacent spans are combined into one service span. Furthermore, if the first 2-week OOH service span was related to involvement in the juvenile justice system (Division of Youth Services in Colorado instead of Division of Child Welfare), the span was not considered the beginning of an OOH episode. Our target is children who are in OOH care for a relatively longer time (2 weeks or more) and who thus may access medical care while in OOH care. For the children/youth in the study, we only analyzed healthcare utilization related to the first entry into OOH care. We examined utilization in the 12 months preceding and following the first entry into care. We excluded a child’s utilization which was related to any second or subsequent entry into care. Finally, we excluded children/youth for whom an initial entry into care was identified prior to January 2014. Medicaid-enrolled matched peers not in OOH care were selected as comparisons for the target population. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt as process improvement research.

Data Sources/Structure

Medicaid Data

An extract of Colorado’s Medicaid program administrative data was obtained from the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing (HCPF) for all children/youth in Colorado under 24 years of age for the years 2014 to 2021. The extract included fee-for-service (FFS) claims and capitated BH encounters.

Child Welfare Administrative Data

An extract of all OOH services provided by child protective service agencies in Colorado from 2014 to 2021 was obtained from the Colorado Department of Human Services (CDHS) Comprehensive Child Welfare Information System. The extract contained information on the type, date, and duration of each service span. The State Identification Module ID was used to link all children represented in the service file with the Medicaid file to determine which child welfare-involved children were also Medicaid-enrolled. For child welfare-involved children, service spans were limited to those related to OOH care and such OOH spans were ordered by date for each child to determine the first entry into extended OOH care. This resulted in 23,121 children with a first entry during the study period, representing our study population. Children not in out-of-home care but Medicaid-enrolled were candidates to be matched comparisons for the children/youth in care (described below).

Measures

Age and Gender (Matching Criterion)

Age is coded as numeric—child’s age in years at the time of first entry into care or, for matched children, the mid-point month of their 25-month Medicaid coverage span. Gender is coded as male/female; the available data does not capture information for non-binary youth or for any additional gender identifications.

Medicaid Coverage Enrollment (Matching Criterion)

Medicaid enrollment for each child was coded as a binary yes/no indicator for each month of data in the file. For each child in care, we used the yes/no indicators for the 12 months preceding entry into care, the month of entry, and the 12 months following entry. The monthly yes/no indicators were combined into a 25-digit string of binary indicators to characterize the coverage pattern surrounding a child’s entry into care. Potential comparison children also had a similarly coded binary string describing their enrollment pattern and were selected for the analytic sample only if they displayed a same-month, 25-digit string match for a child in care.

Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment (Matching Criterion)

Medicaid managed care enrollment for each child was determined for the child’s 25-month study period. A managed care enrollment indicator was coded as binary, with a value of “yes” indicating the child was enrolled in one of the two physical health managed care plans in at least 1 month during their 25-month study period and “no” indicating the child was never enrolled in a managed care plan. We matched using this criterion to adjust for the fact that physical health managed care encounter claims were not available in the Medicaid administrative data files.

Household Income (Matching Criterion)

Household income for each child was extracted from the Medicaid administrative data for the month immediately preceding the entry or reference month and was coded relative to the US Federal Poverty Level (FPL) according to the number of family members for the individual child: < 40% of FPL, 40–100%, 101–133%, ≥ 134% of FPL, or income unknown.

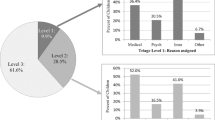

Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (Matching Criterion)

We measured health complexity for study children with the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm, version 3.0 (PMCA) (Simon et al., 2018) through all FFS claims and capitated BH encounter data available prior to the foster care entry or reference month. We chose the PMCA due to prior validation, public availability, use of Medicaid administrative data, and inclusion of physical and behavioral health conditions in the complexity stratifications (Reuland et al., 2021; Simon et al., 2014, 2017). The PMCA categorizes children into one of three mutually exclusive categories: no chronic health disease; noncomplex chronic disease; or complex chronic disease (Simon et al., 2018). Compared to another complexity stratification approach, the PMCA’s stronger sensitivity is advantageous (Neff et al., 2015). For matching, we combined physical non-complex and complex chronic disease stratification and thus matched by (1) no chronic condition or (2) chronic condition.

Behavioral Health Condition (Matching Criterion)

The PMCA was also used to identify BH conditions. As was the case with physical health complexities, both FFS claims and capitated BH encounters were used to identify study children with no chronic BH condition, noncomplex, chronic BH condition, or complex, chronic BH condition. Similarly, for matching, we combined non-complex and complex chronic BH condition categories and thus matched by (1) no chronic condition or (2) chronic condition.

Primary Care and Behavioral Health Utilization (Outcome)

We identified primary care visits using FFS claims, provider type, and CPT codes including outpatient (99,202–99,215), well-child (99,381–99,385 and 99,391–99,395), and preventative counseling (99,401–99,412) visits. See Appendix A for complete detail. BH utilization combined FFS claims and capitated encounters. FFS BH claims were identified through CPT codes; we used CPT codes 90,791, 90,792, 90,832, 90,834, 90,837, 90,846, and 90,847 for behavioral health services delivered outside of primary care settings. All capitated BH encounters were included in the analysis to measure BH utilization.

Medicaid Utilization (Outcome)

The utilization of primary care and/or BH services is measured by the percentage of enrolled children in a month who have a claim for a primary care or BH visit. Utilization results are presented in tables for the combined 12 months preceding entry into care (or preceding the reference month for comparisons), for the month of entry or reference, and for the 12 months following entry or reference. Month-by-month utilization is presented graphically for selected groups of children/youth.

Analysis

Matching Methodology

To address possible confounding of several variables (type/amount of Medicaid coverage, socioeconomic status, medical complexity) with service utilization outcomes, we compared these outcomes of interest between study children and youth (i.e., Medicaid-enrolled and in care) with a matched cohort not in care. Each study child was matched with one comparison child. The matching methodology was “with replacement,” meaning that more than one child or youth in care could be matched to the same comparison child. After the selection of a comparison pool based on age and gender, there were almost 10,000 possible comparison children available per study child and from which matches could be selected.

Matching proceeded iteratively to build an analytic sample of children for whom a suitable match could be found. First, study children (i.e., with the first entry into care during the study period) were matched to compare children by age and gender. Second, this group was evaluated to ensure that each study child could be matched to a child with a comparable 25-month Medicaid coverage eligibility period (i.e., the 25 months surrounding the out-of-home child’s placement). Each child in care was matched to a comparison child with the same 25-digit binary string corresponding to the same 25 calendar months; for the matched comparison child, the 13th month of 25 was designated as the reference month. Third, children were matched on enrollment in Medicaid-managed care (yes/no). Fourth, the analytic sample was limited to children who could be matched to a child of a comparable household income. Finally, study children were matched to a child of comparable medical complexity based on PMCA score and presence/absence of a behavioral health condition. Children/youth for whom a PMCA classification could not be calculated (due to lack of a claims history) were excluded, as were 16 additional children in care for whom there was an unresolvable data anomaly related to the BH indicator. After this multi-step exact matching process was complete, 15,082 of the 23,121 children in the foster cohort could be exactly matched to a non-foster peer, with the largest group unmatched simply due to lack of the claim history required to calculate the PMCA (there were 8039 unmatched children in care, of which 4219—52%—were not matched due to lack of claims history). Because matching was performed with replacement and a non-foster peer comparison could match to more than one child in care, the number of unique non-foster peer children in the analytic sample is less than 15,082 at 12,457.

Descriptive Methods

We present detailed descriptive percentages for primary care and BH utilization. Percentages are calculated as the number of children with a visit/claim for the month divided by the number of enrolled children for the month. For both the foster and non-foster cohorts, the percentage of children with primary care or behavioral healthcare utilization are reported as weighted averages for the 12 months before the reference month, the reference month itself, and the 12 months after the reference month. Results are presented for both children/youth in care and for comparisons (Tables 2, 3, and 4) including: (1) the combined 12 months preceding entry into care (or preceding the reference month), (2) the month of entry or reference month, and (3) the 12 months following entry or reference month. Descriptive results are segmented by age, gender, physical health complexity, and behavioral health condition.

Graphical Methods

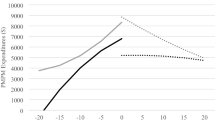

We present graphical results by month for selected groups of children (Fig. 1a–d and Fig. 2a–d), contrasting children/youth in care with comparisons. These graphs highlight differences in monthly utilization patterns between groups and relative to the date of entry into care which may be hidden by the before and after comparisons presented in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

a Percentage of children without chronic physical or behavioral health condition who had a primary care encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care. b Percentage of children without chronic physical but with a behavioral health condition who had a primary care encounter by month and by Foster Care Status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care. c Percentage of children with chronic physical but without behavioral health condition who had a primary care encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care. d Percentage of children with chronic physical and behavioral health condition who had a primary care encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care

a Percentage of children without chronic physical or behavioral health condition who had a behavioral health encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care. b Percentage of children without chronic physical but with behavioral health condition who had a behavioral health encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care. c Percentage of children with chronic physical but without behavioral health condition who had a behavioral health encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care. d Percentage of children with chronic physical and behavioral health condition who had a behavioral health encounter by month and by foster care status. Note: 0 = month of entry into care or reference month for children not in care

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

Youth (N = 30,164 with duplication; N = 27,539 unduplicated) had 165,129 primary care and 86,075 BH encounters over the study period. The demographic and health characteristics of children included in the sample are described in Table 1. Children in our sample had a mean age of 7.5 years (standard deviation, SD, 5.6 years), and most were male (53.8%). The percentage of youth in each age category is equivalent between the foster and non-foster cohorts. Young children, aged 2 years old or less, were the largest age category (29.7%) of the sample, followed by those aged 11 to 15 years old (22.9%), 6 to 10 years old (21.6%), 3 to 5 years old (17.1%), and 16 years old or greater (8.8%). Most children did not have a chronic physical health condition (75.5%) or a BH condition (78.7%) at the month of entry or reference month. Among both cohorts, almost all children lived in impoverished or low-income households; overall, 95.7% of children were from homes with income below or equal to 133% of the federal poverty level, and 72.5% of the sample were from households with income below 40% of the FPL.

Health Care Utilization by Foster Status and Time

Primary Care Utilization by Foster Status and Time

We examined utilization by calculating monthly weighted average percentages of children in the foster and peer cohorts who received primary care services over 25 months (Table 2). During the 12 months prior to the reference month (i.e., month/year of entry for foster youth and same/matched month/year for non-foster youth), a lower percentage of the foster cohort received primary care services (18.0%) than non-foster peers (22.7%). Primary care use peaked for the foster care cohorts during the reference month: 42.7% of children/youth within the foster cohort received a primary care service while only 24.1% of peers did so. Among the foster cohort, primary care utilization during the reference month more than doubled the percentage who used primary care in the preceding 12 months, and it exceeded utilization among the peer cohort by 18.6 percentage points. In the 12 months after the reference month, primary care use decreased relative to the reference month for both cohorts, but with children in foster care have continued higher monthly primary care use (29.9% of foster youth and 20.2% of peers). Examining trends in the 12 months before and after the reference month, primary care utilization increased among the foster cohort by 11.9 percentage points and remained relatively flat among peers.

Behavioral Health Utilization by Foster Status and Time

BH utilization differed among our sample (Table 2). During the 12 months prior to the reference month, a greater percentage of the foster cohort received BH services (9.9%) relative to non-foster peers (4.9%). BH use increased for the foster care cohort during the reference month: 18.2% of children within the foster cohort used BH while only 4.6% of non-foster peers did so. Among the foster cohort, BH utilization during the reference month almost doubled compared to the utilization percentage in the preceding 12 months (18.2% versus 9.9%) and exceeded peer cohort use by 13.6 percentage points. In the 12 months after the reference month, BH use continued to increase relative to the reference month for foster youth (up 10.3 percentage points) with the utilization rate among children in foster care seven times the rate of non-foster peers (28.5% of foster youth and 4.4% of peers). Over 25 months, BH utilization steadily increased in the foster cohort, unlike children in the non-foster peer cohort.

Health Care Utilization by Foster Care Status, Time, and Health Complexity

Primary Care Utilization by Foster Care Status, Time, and Health Complexity

Distinct primary care utilization patterns emerged when introducing health complexity to our analyses. Overall, the monthly percentage of children who received primary care services rose as health complexity increased (Fig. 1a–d); however, utilization differed by foster care status and time among children of the same health complexity status. Lower percentages of children in the foster care cohort used primary care services, despite equivalent health complexities to non-foster peers, in the 12 months prior to the reference month. Use of primary care increased for children in the foster cohort, during the reference month and subsequent 12 months, relative to matched non-foster peers for three of the four health complexity stratifications. Among children with concurrent chronic and BH conditions, a greater percentage of children who entered foster care used primary care services, initially, but utilization differences between the foster and non-foster peer cohorts ceased by the fifth month after the reference month.

Behavioral Health Utilization by Foster Care Status, Time, and Health Complexity

Children in the foster care cohort had higher BH utilization regardless of time or health complexity (Fig. 2a–d). In the 12 months prior to the reference month, the percentage of those in the foster care cohort who used BH services was double the utilization percentage for non-foster peers across all health complexity stratifications. During this time, BH utilization rose for the foster cohort, unlike non-foster peers, as the reference month approached. Utilization patterns differed by the presence of a BH condition; among children with a BH condition in our sample, approximately 40% of children in foster care used BH services. BH utilization differences between the foster care and non-foster cohorts increased during the reference month and remained higher for foster children during the subsequent 12 months. Among children without a BH condition, BH utilization for children in foster care was four to five times higher than non-foster peers. BH utilization increased two to four-fold for children in foster care with a BH condition compared to matched non-foster peers.

Health Care Utilization by Foster Care Status, Time, Health Complexity, Age, and Sex

Primary Care Utilization by Foster Care Status, Time, Health Complexity, Age, and Sex

We examined levels of primary care utilization by health complexity, age, and sex subgroups and by foster care status (Table 3). Generally, a lower percentage of children in the foster care cohort received primary care services in the 12 months before the reference month regardless of health status, age, or sex (36 of 40 comparisons between the “12 months prior” columns of Table 3). Among females, greater percentages of non-foster peers received primary care during the 12 months before the reference month in all but three subgroups: (1) females, aged > 16 years old, without chronic or BH conditions (foster 14.8% versus peers 13.5%); (2) females, aged > 16 years old with chronic but without BH conditions (foster 22.5% versus peers 22.3%); and (3) females, aged 3 to 5 years old, without chronic but with BH conditions (foster 21.2% versus peers 19.3%). Utilization differences were less than two percentage points for each subgroup. Among males, during the 12 months before the reference month, higher percentages of non-foster peers than children in care received primary care services except among males, 2 years or younger, with both chronic and BH conditions (foster 61.0% versus peers 51.9%).

Among those in foster care, the percentage with primary care utilization increased during the reference month and exceeded all peer percentages regardless of health complexity, age, or sex (40 of 40 comparisons between the “Reference month” columns of Table 3). The range of percentage point differences between foster and peer utilization varied substantially; for females, it ranged from 1.8 to 90 points; for males, it ranged from 5.1 to 44.3 points. Increased utilization continued in the 12 months after the reference month (i.e., entry into care) among the foster cohort compared to non-foster peers, except for three subgroups with concurrent chronic and BH status: (1) females aged 2 years or younger (foster 48.3% and peers 71.8%); and males, either aged 2) 11 to 15 years old (foster 27.7% and peers 28.2%); or 3) ≥ 16 years old (foster 24.3% and peers 25.6%).

Behavioral Health Utilization by Foster Status, Time, Health Complexity, Age, and Sex

Generally, higher percentages of children in the foster care cohort received BH services in the 12 months before the reference month regardless of health classification, age, or sex (38 of 40 comparisons between the “12 months prior” columns of Table 4). The two outlier subgroups, children aged 2 years or younger and with no chronic physical condition and a BH condition, had utilization differences which were less than one percentage point for males (foster males 0.7% versus peer males 1.4%;), and the foster female subgroup was not populated. For the 38 subgroups in which the foster care cohort BH utilization exceeded that of non-foster peers, the utilization differed by 0.2 to 29.9 percentage points above-matched peers.

During the reference month, the percentage of children in the foster cohort using BH services increased in comparison to the 12 months prior for all foster subgroups. Compared to non-foster peers, higher percentages of children in foster care used BH services for 36 of 40 subgroups with differences ranging from 0.2 to 43.8 percentage points. Of the four subgroups with greater utilization among non-foster peers, differences were minimal. Two subgroups had no children in either cohort, another had equal utilization regardless of foster care status and the fourth differed by only 0.4 percentage points.

In the 12 months following the reference month, BH utilization among the foster cohort continued to rise for all but nine subgroups (31 of 40 subgroup comparisons). The exceptions were often older youth (ages 11 years and older) with a behavioral health condition. BH utilization was higher within each foster care cohort subgroup relative to matched non-foster peers and ranged between 3.8 and 47.6 percentage points. BH utilization differences were similar regardless of sex: females in care ranged between 3.6 and 41.3 percentage points higher than non-foster females while males in care ranged between 3.8 and 47.6 percentage points versus non-foster males. The greatest utilization difference occurred among children without a behavioral health condition who differed by foster care status; children in foster received BH services at levels up to 37 percentage points higher than matched non-foster peers in the 12 months after the reference month.

Discussion

This study of more than 27,000 Medicaid-enrolled children advances previous research by providing longitudinal data regarding FFS primary care and capitated BH service use trends among a large cohort of children entering foster care, by examining associations of child sex, age, and health complexity with use patterns and, through linking child welfare and Medicaid administrative data, by comparing utilization trends to matched non-foster, Medicaid-enrolled peers. We found distinct primary care and BH utilization patterns among children with initial foster care entry compared to those of age-, sex-, income- and health complexity-matched peers without foster care experience. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine longitudinal utilization trends by health complexity among children in foster care using rigorously linked data sources.

We designed our study to answer two questions: (1) does primary care utilization differ between Medicaid-enrolled children by initial foster care entry status and (2) does BH utilization differ between Medicaid-enrolled children by initial foster care entry status? The answer to both is unequivocally “yes.” Relative to primary care utilization among non-foster peers, the foster cohort used less before and more after foster care entry, consistent with our hypothesis. BH utilization differed, as well, but not as anticipated; higher percentages of children in the foster cohort used BH services both before and after foster care entry. Noting utilization differences, we analyzed trends by time before and after foster care entry and by health complexity. We found higher, sustained use of BH services, for all, and of primary care services, for most, children upon or after entry to foster care, which surpassed non-foster peers matched by sex, age, and health status.

Specific to primary care utilization patterns for children in foster care, results extend current literature using methods which provide more detailed information about longitudinal utilization trends centered on initial placement and comparing this use to that of matched non-foster peers. Previous results regarding primary care use are somewhat mixed, and results may depend on the sample of children included and the data collection period emphasis on either before or after entry to care but not both. Friedlaender et al. (2005) found more frequent primary care visits in the preceding 12 months among children with diagnosed maltreatment. Another found more outpatient visits for victims for sexual abuse (Wang et al., 2019). Both focused on younger children, preventing a more comprehensive assessment of the full population. A third study by Karatekin et al. (2018) found no difference in outpatient and preventative visits. Among adolescents, another study found no difference in health care use by foster care status (Schneiderman et al., 2016). However, two recent studies found lower primary care use among children in care when compared to non-foster peers (Bennett et al., 2019; Lynch et al., 2021). Fewer studies examine trends in health care use before and after foster care entry. A prior statewide analysis found 5% lower primary care use for all children entering foster care when comparing the 12 months before and after placement (Johnson et al., 2013). Our results found a ten-percentage point increase in primary care utilization for children in foster care in the 12 months after foster care entry, overall. Unlike prior results, our findings accounted for child health complexity, age, and sex to provide greater detail to primary care trends. Our findings among children with concurrent chronic and BH conditions suggest health complexity influences primary care use as foster and non-foster peer utilization closely aligns beginning 5 months after the reference month. Yet, differences in primary care utilization in the initial months after entering foster care for children in foster cohort with concurrent chronic and BH conditions and 12-month post-foster care entry trends among the other three health complexity stratifications infer health complexity is not the only influence on primary care use (Greiner et al., 2015; Patton et al., 2019). Future studies should examine utilization by race and ethnicity.

Literature, to date, asserts child welfare as a gateway to behavioral health services (Leslie et al., 2005) and our findings demonstrate a similar and immediate increase in BH service use among children entering foster care. Our findings in the 12 months after foster entry (as shown in Table 2) are slightly lower than the 30 to 36% reported previously (Center for Mental Health Services & Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2013; Harman et al., 2000; Horwitz et al., 2012) but nearly seven times greater than use among non-foster peers. However, our results suggest that while child welfare is a gateway for some children other youths have pre-existing BH services prior to initial foster placement. In our sample, nearly 10% of children in the foster cohort received BH services prior to entry, double the utilization of non-foster peers, indicating escalated utilization prior to child welfare custody. These findings are at least double the utilization rate Leslie et al. (2005) described and may be influenced by the approximately 20% of children who enter foster care due to behavioral problems and parental inability to cope (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2021). Short-term behavioral health services have been available through primary care settings since July 2018 in Colorado and may influence BH utilization results. Future work with high-quality, integrated health care and child welfare data should examine the role of BH service type and foster entry reasons among this subgroup of youth.

Through examining BH utilization trends according to sex, age, and health status which included BH conditions, however, our results provided a more nuanced assessment of children who received BH services not only upon but also prior to foster care entry. BH utilization had little variation by sex in our analysis. Previous studies identify child age as a significant predictor for receipt of BH services (Leslie et al., 2005; Raghavan et al., 2010). Our analysis revealed use of BH utilization increased as age increased regardless of sex or health status among the foster cohort. Among our sample, up to one-half of adolescents in foster care, aged 12 years or greater, used BH services after foster care entry, a rate three times greater than use among US adolescents overall (Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Among younger children aged 5 years old or younger, those in the foster cohort used BH services at rates up to 20 times higher than non-foster peers. Although foster placement is a traumatic event for all children who enter care, higher BH use among young children in foster care may be prioritized for BH services by caregivers, health care providers, child welfare professionals, or court officials (Baker et al., 2017; Garland & Besinger, 1997; Pullmann et al., 2018). For both those with and without a BH condition in the foster cohort, we found BH utilization increased immediately upon foster entry, in contrast to prior national studies (Leslie et al., 2004, 2005). Among children who entered foster care without a BH designation prior to foster entry, we found the percentages of children who received BH services increased up to 15-fold with or following foster care placement from the percentage that used these services in the 12 months before placement. BH use increased among those children entering foster care known to have a BH condition to a lesser degree in the month of or 12 months following care entry, but surpassed use in the 12 months prior to the month of entry for all subgroups. Additional research describing the use of validated BH screening tools by health care and child welfare, the reasons for entering foster care, and the types of services delivered are needed to understand if increased BH utilization is in response to child factors such as previously unrecognized or emerging need resulting from foster care entry or driven by other factors.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of the study include the integration of Medicaid and child welfare administrative data to allow accurate information for health care use and timing of foster care entry, longitudinal population-based assessment, and determination of health complexity status. There are several limitations to this study. First, the study analyzed Medicaid and child welfare data from a single Western state in the USA and may not be generalizable to other settings. Increasingly, states have introduced Medicaid Managed Care (MMC) options specific to children in foster care to improve care coordination and health care service delivery. A recent analysis of a state-level transition from FFS to a MMC delivery model specific to children in foster care found greater access to primary care and increased completion of preventative health visits with MMC implementation (Bright et al., 2018). Comprehensive MMC claims data were not available to the study team; however, this study seeks to understand longitudinal health care utilization trends among children initially entering foster care and non-foster peers. Second, we identified all children with initial foster care placement using statewide child welfare administrative data; however, a portion of children who entered foster care was excluded from the analysis because they could not be matched to a non-foster peer. The greatest proportion of children in foster care excluded from the analysis lacked adequate medical and behavioral health claims for PMCA stratification (missing PMCA). Children with missing PMCA stratification may represent a distinct subpopulation with distinct primary care and BH use trends from the children included in our sample and future research should explore this group in greater detail. Next, our analysis defined health status at the reference month; most children included in the analysis did not have chronic or behavioral health conditions. Children in foster care have concentrated chronic and behavioral health conditions; lower primary care use prior in the 12 months prior to first foster care entry may contribute to unrecognized chronic health conditions among children in foster care, therefore leading to misclassification bias in our study. The research focused on the influence of foster care entry on healthy complexity stratification is needed. Finally, our analysis did not include race and ethnicity when reporting longitudinal trends in primary care and BH utilization, due to such data being missing for more than 40% of state Medicaid claims for the years of analysis (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2022) .

Conclusions

Our study advances understanding of differences by foster care entry status and child health status on primary care and BH utilization and it highlights opportunities to improve the delivery of these health care services for this population. Specifically, this study identifies for the first time, differences in longitudinal utilization trends in primary care and BH services by child chronic physical and BH health complexity. Children who enter foster care differ from non-foster peers by time and by child age, sex, and health status. Furthermore, our findings are notable for identifying that while foster care entry, overall, accelerates primary care and BH service delivery, health complexity is not the exclusive source for increased health care use. Knowledge of chronic and BH health condition histories and health care use trends may improve health care and child welfare system efforts not only to ensure children entering foster care receive timely and need-based primary and BH services but also to assess the quality of health care and health care delivery models that facilitate positive child outcomes but require health care and child welfare systems shift to more collaborative data partnerships. Current and developing program and practice innovations (Stockman et al., 2021, May 24, 2021; Greiner et al., 2019; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services., 2022a) are promising and, if successful, valuable to future work.

Data Availability

The raw/processed data required to reproduce the above findings cannot be shared at this time due to legal/ ethical reasons.

Change history

01 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-023-00181-w

05 September 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-023-00177-6

References

Adoption and Safe Families Act. P.L. 105–89, (1997).

Baker, A. J. L., Schneiderman, M., & Licandro, V. (2017). Mental health referrals and treatment in a sample of youth in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 78, 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.020

Beal, S. J., Ammerman, R. T., Mara, C. A., Nause, K., & Greiner, M. V. (2022). Patterns of healthcare utilization with placement changes for youth in foster care. Child Abuse and Neglect, 128, 105592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105592

Becker, M., Jordan, N., & Larsen, R. (2006). Behavioral health service use and costs among children in foster care. Child Welfare, 85(3), 633–647.

Bennett, C. E., Wood, J. N., & Scribano, P. V. (2019). Healthcare utilization for children in foster care. Academic Pediatrics, 20(3), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.10.004

Bilaver, L. A., Havlicek, J., & Davis, M. M. (2020). Prevalence of special health care needs among foster youth in a nationally representative survey. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(7), 727–729. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0298

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. P.L. 115–123, (2018).

Boyd, R., & Scribano, P. (2021). Improving foster care outcomes via cross-sector data and interoperability JAMA. Pediatrics, 176(1), e214321. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4321

Bright, M. A., Kleinman, L., Vogel, B., & Shenkman, E. (2018). Visits to primary care and emergency department reliance for foster youth: Impact of Medicaid managed care. Academic Pediatrics, 18(4), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.10.005

Burns, B. J., Phillips, S. D., Wagner, H. R., Barth, R. P., Kolko, D. J., Campbell, Y., & Landsverk, J. (2004). Mental health need and access to mental health services by youths involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(8), 960–970. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000127590.95585.65

Center for Mental Health Services and Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2013). Diagnoses and health care utilization of children who are in foster care and covered by Medicaid. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma13-4804.pdf. Accessed 15 March 2021.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022). DQ ATLAS. Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/dq-atlas/landing/topics/single/map?topic=g3m16&tafVersionId=24. Accessed 5 Dec 2021.

Chaiyachati, B. H., Wood, J. N., Mitra, N., & Chaiyachati, K. H. (2020). All-cause mortality among children in the US foster care system, 2003–2016. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 896–898. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0715

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. (2022). Data query. 2016–2017 National Survey of Children’s Health. Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB). Retrieved from https://www.childhealthdata.org. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Child and Family Services Improvement and Innovation Act. P.L. 112–134 (2011). https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/2883. Accessed 24 Jan 2022.

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2022). Health-care coverage for children and youth in foster care—and after. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/health_care_foster.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2022.

Christian, C. W., & Schwarz, D. F. (2011). Child maltreatment and the transition to adult-based medical and mental health care. Pediatrics, 127(1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2297

Drake, B., Fluke, J. D., Kim, H., Orsi, R., & Stubblefield, J. L. (2021). What proportion of foster care children do not have child protective services reports? A Preliminary Look. Child Maltreatment, 27(4), 596–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211033855

Edwards, F., Wakefield, S., Healy, K., & Wildeman, C. (2021). Contact with child protective services is pervasive but unequally distributed by race and ethnicity in large US counties. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(30), e2106272118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2106272118

Engler, A. D., Sarpong, K. O., Van Horne, B. S., Greeley, C. S., & Keefe, R. J. (2020). A systematic review of mental health disorders of children in foster care. Trauma Violence and Abuse, 23(1), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020941197

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Florence, C., Brown, D. S., Fang, X., & Thompson, H. F. (2013). Health care costs associated with child maltreatment: Impact on Medicaid. Pediatrics, 132(2), 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2212

Fluke, J., Jones Harden, B., Jenkins, M., & Ruehrdanz, A. (2011). Disparities and disproportionality in child welfare: Analysis of the research. Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/15376/Casey_Disparities_ChildWelfare.pdf?sequence=5. Accessed 31 May 2022.

Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act. P.L. 110–351. (2008).

Friedlaender, E. Y., Rubin, D. M., Alpern, E. R., Mandell, D. S., Christian, C. W., & Alessandrini, E. A. (2005). Patterns of health care use that may identify young children who are at risk for maltreatment. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1303–1308. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1988

Garland, A., & Besinger, B. (1997). Racial/ethnic differences in court referred pathways to mental health services for children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 19(8), 651–666.

Greiner, M. V., Ross, J., Brown, C. M., Beal, S. J., & Sherman, S. N. (2015). Foster caregivers’ perspectives on the medical challenges of children placed in their care: Implications for pediatricians caring for children in foster care. Clinical Pediatrics, 54(9), 853–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922814563925

Greiner, M. V., Beal, S. J., Dexheimer, J. W., Divekar, P., Patel, V., & Hall, E. S. (2019). Improving information sharing for youth in foster care. Pediatrics, 144(2), e20190580. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0580

Halfon, N., Mendonca, A., & Berkowitz, G. (1995). Health status of children in foster care: The experience of the center for the vulnerable child. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 149(4), 386–392. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170160040006

Harman, J. S., Childs, G. E., & Kelleher, K. J. (2000). Mental health care utilization and expenditures by children in foster care. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 154(11), 1114–1117. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.154.11.1114

Horwitz, S. M., Hurlburt, M. S., Goldhaber-Fiebert, J. D., Heneghan, A. M., Zhang, J., Rolls-Reutz, J., Fisher, E., Landsverk, J., & Stein, R. E. (2012). Mental health services use by children investigated by child welfare agencies. Pediatrics, 130(5), 861–869. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1330

Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Primary Care. (1996). Donaldson, M. S., Yordy, K. D., Lohr, K. N., & Vanselow, N. A. (Eds.). Primary care: America’s health in a new era. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Johnson, C., Silver, P., & Wulczyn, F. (2013). Raising the bar for health and mental health service for children in foster care: Developing a model of managed care. New York, NY: Council on Family and Child Caring Agencies and NYS Helath Foundation. https://www.cofcca.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/FosterCareManagedCare-FinalReport.pdf. Accessed 10 Aug 2022.

Jonson-Reid, M., & Drake, B. (2016). Child well-being: Where is it in our data systems? Journal of Public Child Welfare, 10(4), 457–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2016.1155524

Karatekin, C., Almy, B., Mason, S. M., Borowsky, I., & Barnes, A. (2018). Health-care utilization patterns of maltreated youth. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(6), 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsy004

Keefe, R. J., Van Horne, B. S., Cain, C. M., Budolfson, K., Thompson, R., & Greeley, C. S. (2020). A comparison study of primary care utilization and mental health disorder diagnoses among children in and out of foster care on Medicaid. Clinical Pediatrics, 59(3), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819898182

Landers, G. M., Snyder, A., & Zhou, M. (2013). Comparing preventive visits of children in foster care with other children in Medicaid. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 24(2), 802–812. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2013.0066

Landers, G. M., & Zhou, M. (2004). Comparing the health status and health care utilization of children in Georgia’s foster care system to other Georgia Medicaid children. Georgia Health Policy Center. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1079&context=ghpc_articles. Accessed 27 May 2022.

Lane, W. G., Rubin, D. M., Monteith, R., & Christian, C. W. (2002). Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(13), 1603–1609. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.13.1603

Lansford, J. E., Godwin, J., McMahon, R. J., Crowley, M., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., Coie, J. D., & Dodge, K. A. (2021). Early physical abuse and adult outcomes. Pediatrics, 147(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0873

Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M. S., Landsverk, J., Rolls, J. A., Wood, P. A., & Kelleher, K. J. (2003). Comprehensive assessments for children entering foster care: A national perspective. Pediatrics, 112(1 Pt 1), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.1.134

Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M. S., Landsverk, J., Barth, R., & Slymen, D. J. (2004). Outpatient mental health services for children in foster care: A national perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28(6), 699–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.004

Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M. S., James, S., Landsverk, J., Slymen, D. J., & Zhang, J. (2005). Relationship between entry into child welfare and mental health service use. Psychiatric Services, 56(8), 981–987. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.8.981

Lynch, F. L., Hoopes, M. J., Hatch, B. A., Dunne, M., Larson, A. E., O’Neill, A., & Pears, K. C. (2021). Understanding health need and services received by youth in foster care in community safety-net health centers in Oregon. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 32(2), 783–798. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2021.0105

Maloney, T., Jiang, N., Putnam-Hornstein, E., Dalton, E., & Vaithianathan, R. (2017). Black-white differences in child maltreatment reports and foster care placements: A statistical decomposition using linked administrative data. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(3), 414–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2242-3

Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J., Janczewski, C. E., Lee, C. P., McGaughey, G., & McNeil, C. B. (2020). Translating and implementing evidence-based mental health services in child welfare. Adminstration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(5), 693–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-020-01011-8

Neff, J. M., Clifton, H., Popalisky, J., & Zhou, C. (2015). Stratification of children by medical complexity. Academic Pediatrics, 15(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.007

Palinkas, L. A., Fuentes, D., Finno, M., Garcia, A. R., Holloway, I. W., & Chamberlain, P. (2014). Inter-organizational collaboration in the implementation of evidence-based practices among public agencies serving abused and neglected youth. Adminstration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0437-5

Palusci, V. J., & Botash, A. S. (2021). Race and bias in child maltreatment diagnosis and reporting. Pediatrics, 148(1), e2020049625. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-049625

Patton, D. A., Liu, Q., Adelson, J. D., & Lucenko, B. A. (2019). Assessing the social determinants of health care costs for Medicaid-enrolled adolescents in Washington State using administrative data. Health Services Research, 54(1), 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13052

Pullmann, M. D., Jacobson, J., Parker, E., Cevasco, M., Uomoto, J. A., Putnam, B. J., Benshoof, T., & Kerns, S. E. U. (2018). Tracing the pathway from mental health screening to services for children and youth in foster care. Child and Youth Services Review, 89, 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.038

Raghavan, R., Inoue, M., Ettner, S. L., Hamilton, B. H., & Landsverk, J. (2010). A preliminary analysis of the receipt of mental health services consistent with national standards among children in the child welfare system. American Journal of Public Health, 100(4), 742–749. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.151472

Raghavan, R., Brown, D. S., & Allaire, B. T. (2017). Can medicaid claims validly ascertain foster care status? Child Maltreatment, 22(3), 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517712261

Reilly, T. (2003). Transition from care: Status and outcomes of youth who age out of foster care. Child Welfare, 82(6), 727–746.

Reuland, C. P., Collins, J., Chiang, L., Stewart, V., Cochran, A. C., Coon, C. W., Shinde, D., & Hargunani, D. (2021). Oregon’s approach to leveraging system-level data to guide a social determinants of health-informed approach to children’s healthcare. BMJ Innovations, 7(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000452

Ringeisen, H., Casanueva, C., Urato, M., & Cross, T. (2008). Special health care needs among children in the child welfare system. Pediatrics, 122(1), e232-241. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-3778

Rosenbach, M., Lewis, K., & Quinn, B. (1999). Health conditions, utilization, and expenditures of children in foster care. Washington DC: Office of the Assitant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/health-conditions-utilization-expenditures-children-foster-care. Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

Rubin, D. M., Pati, S., Luan, X., & Alessandrini, E. A. (2005). A sampling bias in identifying children in foster care using Medicaid data. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 5(3), 185–190. https://doi.org/10.1367/A04-120R.1

Rubin, D. M., O’Reilly, A. L., Luan, X., & Localio, A. R. (2007). The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics, 119(2), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-1995

Sariaslan, A., Kääriälä, A., Pitkänen, J., Remes, H., Aaltonen, M., Hiilamo, H., Martikainen, P., & Fazel, S. (2021). Long-term health and social outcomes in children and adolescents placed in out-of-home care. JAMA Pediatrics. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4324

Schneiderman, J. U., Negriff, S., & Trickett, P. K. (2016). Self-report of health problems and health care use among maltreated and comparison adolescents. Child and Youth Services Review, 61, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.001

Sedlak, A. J., Mettenburg, J., Basena, M., Peta, I., McPherson, K., & Greene, A. (2010). Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS–4): Report to congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/abuse_neglect/natl_incid/index.html. Accessed 7 Sept 2021.

Sepulveda, K., Rosenberg, R., Sun, S., & Wilkins, S. (2020). Children and youth with special health care needs in foster care. https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CYSHCN_ChildTrends_Dec20-2.pdf. Accessed 8 Dec 2020.

Shi, L. (2012). The impact of primary care: A focused review. Scientifica, 2012, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.6064/2012/432892

Silver, J., DiLorenzo, P., Zukoski, M., Ross, P. E., Amster, B. J., & Schlegel, D. (1999). Starting young: Improving the health and developmental outcomes of infants and toddlers in the child welfare system. Child Welfare, 78(1), 148–165.

Simms, M. D., Dubowitz, H., & Szilagyi, M. A. (2000). Health care needs of children in the foster care system. Pediatrics, 106(4 Suppl), 909–918.

Simon, T. D., Cawthon, M. L., Stanford, S., Popalisky, J., Lyons, D., Woodcox, P., Hood, M., Chen, A. Y., & Mangione-Smith, R. (2014). Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: A new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics, 133(6), e1647-1654. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3875

Simon, T. D., Cawthon, M. L., Popalisky, J., & Mangione-Smith, R. (2017). Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 2.0. Hospital Pediatrics, 7(7), 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0173

Simon, T. D., Haaland, W., Hawley, K., Lambka, K., & Mangione-Smith, R. (2018). Development and validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 3.0. Academic Pediatrics, 18(5), 577–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2018.02.010

Social Security Title IV-B, Stephanie Tubbs Jones Child Welfare Services Program § 622. (2015). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2015-title42/html/USCODE-2015-title42-chap7-subchapIV-partB-subpart1-sec622.htm. Accessed 15 Sept 2021.

Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

Stein, R. E., Hurlburt, M. S., Heneghan, A. M., Zhang, J., Rolls-Reutz, J., Silver, E. J., Fisher, E., Landsverk, J., & Horwitz, S. M. (2013). Chronic conditions among children investigated by child welfare: A national sample. Pediatrics, 131(3), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1774

Stockman, D., Jones Gaston, R., Coyner, L., Putnam, B., Donlin, K., Lucenko, B., Zickafoose, J., & Armistead, L. (2021, May 24). Establishing and using bidirectional data sharing[centers for medicare and medicaid services Medicaid & CHIP health care quality improvement, webinar]. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/quality-of-care/downloads/foster-care-est-usin-bider-data-shar-webinar.pdf. Accessed 5 Dec 2021.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf. Accessed 26 Apr 2022.

Szilagyi, M. A., Rosen, D. S., Rubin, D., Zlotnik, S., Council On Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care, & Committee On Adolescence, & Council On Early Childhood. (2015). Health care issues for children and adolescents in foster care and kinship care. Pediatrics, 136(4), e1142-1166. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2656

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. P.L. 111–148, (2010).

Turney, K., & Wildeman, C. (2016). Mental and physical health of children in foster care. Pediatrics, 138(5). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1118

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration of Children and Families. (2022b, January 20). Toolkit: Data Sharing for Child Welfare Agencies and Medicaid. Washington, DC: Retrieved 1/27/22 from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/data-sharing-and-medicaid-toolkit.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2022.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. (2015). Not all children in foster care who were enrolled in Medicaid received required health screenings. Washington, DC. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-07-13-00460.pdf

U.S. Department of Justice, & Child Welfare League of America. (1988). Standards for health care services for children in out-of-home care, NCJ #135686.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2021). The AFCARS Report #28. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/afcarsreport28.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2021.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2022a). Child maltreatment 2020. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/data-research/child-maltreatment. Accessed 25 May 2022.

U.S. General Accounting Office. (1995). Foster care: Health needs of many young children are unknown and unmet. Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/assets/hehs-95-114.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2022.

Wang, L. Y., Wu, C. Y., Chang, Y. H., & Lu, T. H. (2019). Health care utilization pattern prior to maltreatment among children under five years of age in Taiwan. Child Abuse and Neglect, 98, 104202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104202

Wildeman, C., & Emanuel, N. (2014). Cumulative risks of foster care placement by age 18 for U.S. children, 2000–2011. PLoS One, 9(3), e92785. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0092785

Wood, J. N., Hall, M., Schilling, S., Keren, R., Mitra, N., & Rubin, D. M. (2010). Disparities in the evaluation and diagnosis of abuse among infants with traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics, 126(3), 408–414. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0031

Acknowledgements

We thank the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing and the Colorado Department of Human Services for their time and effort to the project.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse & Neglect. The research leading to these results received funding from the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing through a non-grant agreement with the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Kaferly conceptualized and designed the study, provided detailed oversight of data analysis, interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Drs. Orsi and Alishahi co-conceptualized and designed the study, provided detailed oversight of data analysis, interpreted the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Mr. Hosokawa and Mr. Sevick prepared the data and conducted the data analyses; Mrs. Mathieu critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. Gritz conceptualized and designed the study and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Additional Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) Codes for Primary Care

Immunization: 90378, 90460, 90461, 90471, 90472, 90473, 90474, 90632, 90633, 90636, 90645, 90647, 90648, 90649, 90650, 90654, 90655, 90656, 90657, 90658, 90660, 90661, 90669, 90670, 90672, 90680, 90681, 90686, 90688, 90696, 90698, 90700, 90702, 90703, 90704, 90705, 90707, 90708, 90710, 90713, 90714, 90715, 90716, 90718, 90721, 90723, 90732, 90733, 90734, 90736, 90740, 90743, 90744, 90746, 90747, S0195, 90651, 90706

Laboratory services: 36415,36416, 82951, 82952, 87086, G0432, S3620, 80055, 80061, 81007, 82270, 82274, 82465, 82728, 82947, 82948, 82950, 83020, 83036, 84030, 84153, 84478, 85013, 85014, 85018, 85660, 86580, 86592, 86593, 86631, 86632, 86689, 86701, 86702, 86703, 86782, 86803, 86804, 86901, 87081, 87088, 87110, 87164, 87166, 87205, 87270, 87285, 87320, 87340, 87341, 87350, 87380, 87390, 87391, 87490, 87491, 87520, 87521, 87522, 87590, 87591, 87592, 87801, 87810, 87850

Obstetrics and women’s health: 59400, 59425, 59426, 59510, 59610, 59618, 90384, 90385, 90386, 77052, 77055, 77057, G0124, G0143, G0144, G0145, G0147, G0148, G0202, P3000, P3001, Q0091, Q0111, 99381, 99382, 99383, 99384, 99385, 99386, 99387, 99391, 99392, 99393, 99394, 99395, 99396, 99397

Preventative care, screening and counseling: 92551, 92552, 92553, 92558, 92585, 92586, 92587, 92588, 96110, 99173, 99174, G0101, G0102, 99420, 99429, 99398; 99355, 99050

Dental care: D0120, D0140, D0145, D0150, D0190, D1110, D1120, D1206, D1208,

Counseling/screening: G0442, G0443, G0444, G0445, G0446, G0447

Procedures: 69210, 96372, 77080

Care at a nursing facility or home: 99304, 99305, 99306, 99307, 99308, 99309, 99310, 99315, 99316, 99318, 99324, 99325, 99326, 99327, 99328, 99334, 99335, 99336, 99337, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350

Home health/hospice supervision: G0181, G9006, G0182

Professional communication, case or chronic care management: 99446, 99447, 99448, 99449, 99367, 9936899487, 99489, 99490, G9012, T1017, S0257, 99374, 99375, 99377, 99378, 99379, 99380

Program intake assessment: T1023

Medical nutrition therapy: 97802, 97803, 97804

Anticoagulation management: 99363, 99364

Time-based coding: 99497

Behavioral health in primary care: 96127,

Family psychotherapy: 90847, 90887

Group psychotherapy: 90853

Alcohol and drug abuse treatment services/rehabilitative services: H0001, H0002, H0031, H0034, H0039, H0049, H1010, H1011, H0023

In home MH and substance use treatment: H0004

Behavioral health prevention education: H0025

Health and behavior assessments, transitional care and telehealth: 96150, 96151, 96152, 96153, 96154, 96155, 98967, 98968, 98969, 99441, 99442, 99443, 99444, 98966, 99495, 99496

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaferly, J., Orsi, R., Alishahi, M. et al. Primary Care and Behavioral Health Services Use Differ Among Medicaid-Enrolled Children by Initial Foster Care Entry Status. Int. Journal on Child Malt. 6, 255–285 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-022-00142-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-022-00142-9