Abstract

We report a case of a large thrombus entrapped in a patent foramen ovale after bariatric surgery and pulmonary embolism. The 60-year-old female patient was admitted to hospital as an emergency after syncope. She suffered from metabolic syndrome with obesity (height: 180 cm, weight: 170 kg, BMI: 49.4 kg/m2) and an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type 2. She had had bariatric surgery (implantation of a gastric balloon) 4 weeks prior to hospitalization. A transthoracic echocardiography was performed which indicated a large entrapped thrombus in the patent foramen ovale with extensions of approximately 10 cm in both the right and the left heart. Surgical embolectomy was performed to remove the circa 20-cm-long thrombus.At the time of surgery, only 2 cm of the transit thrombus remained in the right atrium. Thus, during the time between diagnosis and emergency surgery, the thrombus had gradually migrated 8 cm. Pulmonary embolectomy and closure of the patent foramen ovale were performed during the same procedure. The patient recovered completely without any complications and was discharged 11 postoperatively. This case demonstrates the importance of urgent medical decision-making with transit thrombi — time is running out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A transit thrombus in a patent foramen ovale is very rare and a critical location for an embolus that is associated with a significantly high mortality rate. Characteristically, the thrombus is entrapped in a patent foramen ovale (PFO) and is partly localized in the right and in the left atrium. A high pressure in the right atrium forces the PFO to open and the embolus to pass into the systemic circulation. This may lead to paradoxical embolism with a mortality rate of up to 66% [1].

Clinical Summary

We report a case of a large thrombus entrapped in the PFO after bariatric surgery and pulmonary embolism.

A 60-year-old obese female was admitted to an affiliated hospital as an emergency after a syncope. She had bariatric surgery 4 weeks prior, when she underwent an endoscopic implantation of a gastric balloon. Postoperatively and at home, she complained of recurrent nausea with vomiting and a weight loss of 40 kg. She had been bedridden since the ballon implantation, probably due to hypervolämia, and received no anticoagulation. She reported a painful swelling of the left lower leg a few days prior to admission. One day before admission, she developed an increasing dyspnea. On the day of admission, she collapsed and was unconscious for several seconds.

On admission, the patient was awake, orientated, and hemodynamically stable with a blood pressure of 150/100 mmHg, a heart rate of 95 bpm, and an O2 saturation of 94% under treatment with 4 l of oxygen. She had metabolic syndrome with obesity (height: 180 cm, weight: 170 kg, BMI: 49.4 kg/m2) and an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus type 2. The electrocardiogram showed a heart rate of 97/min, a SIQIII type, and a right bundle branch block. Laboratory results showed D-dimer of 16.58 mg/l (< 0.5), LDH of 306 IU/l, natrium of 132 mmol/l, creatinine of 1.11 mg/dl blood glucose level (563 mg/dl), and HbA1c of 11.9%. Point of care blood gas analysis showed pO2 of 62.5 mmHg, pCO2 of 37.2 mmHg, and pH of 7.416.

An intracranial hemorrhage after syncope could be ruled out with a cranial computed tomography scan.

To further diagnose the underlying cause of her shortness of breath, a transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed. The left ventricular function was mildly impaired. A massive dilatation of the right ventricle (41 cm2) was observed. The RV function was impaired (TAPSE 11 mm) and estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure was 57 mmHg.

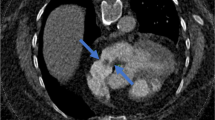

On closer inspection, a floating structure entrapped in a patent foramen ovale (PFO) was detected (Fig. 1, Supplementary material 123). Approximately 10 cm of the structure was seen in both the right and left atrium passing through the tricuspid and mitral valves and flowing into the ventricle. It was most likely a large entrapped thrombus.

Given the particular combination of high pulmonary artery pressure, dyspnea, and thrombus-in-transit, a preoperative chest computerized-tomography-pulmonary-angiogram was performed. It showed a massive central pulmonary embolism with dissemination into all segmental arteries (Figure 1, Supplementary material 4) and a dilated right heart with the entrapped thrombus. The patient was transferred to our heart center. The laboratory results showed no predisposing factors for thrombosis, AT III 107% (84–125), APC resistance 2.0 (2–5), protein C 111% (65–150), and protein S 70% (70–130). We consider the cause of the thrombosis due to the bedrest and the dehydration.

Upon initial echocardiography at our institution, a further transit of the thrombus could be demonstrated; the fraction of the thrombus in the right heart was smaller than the one in the left heart.

The decision for an immediate surgical embolectomy of this entrapped thrombus was made.

Intraoperatively after incision of the right atrium, we found an approximately 20-cm-long thrombus, trapped in the PFO. The thrombus could be carefully extracted in toto out of the left heart cavities (Fig. 1, bottom).

After transverse incision of the pulmonary several additional thrombi could be removed from both central pulmonary arteries. These thrombi appeared partially older.

At the time of surgery, only about 2 cm of the huge transit thrombus was still located in the right atrium. The thrombus had migrated gradually approximately 8 cm between the time of diagnosis and the emergency surgery.

The patient recovered completely without any neurological deficits or other symptoms of peripheral embolism. Despite difficult mobilization due to her obesity, she could be discharged 11 days after surgery.

The risk of venous thromboembolism is significantly increased after a case of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism [2]. Therefore, we used anticoagulation therapy postoperatively and full-dose warfarin after discharge from hospital.

Discussion

An entrapped thrombus in a patent foramen ovale is a very rare finding associated with a high mortality rate [1]. In the neonatal circulation, the foramen ovale is open, so that oxygenated blood can flow directly into the systemic circulation. After birth and ventilation, the resistance of the lung circulation falls, the left atrial pressure rises, and the foramen typically closes permanently.

In about 27% of people, it remains open, and, in a situation of high atrial pressure, blood and thrombi can enter the systemic circulation through the foramen ovale and lead to cryptogenic embolic stroke [3]. A high right atrial pressure may be due to recurrent embolism causing pulmonary hypertension. This may lead to a reopening of a foramen ovale and paradoxical embolism causing strokes or acute limb ischemia [4].

In our case, we could see the thrombus clearly on TTE and on computed tomography, but a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is the superior imaging modality for detecting atrial pathology [2].

In the case of a thrombus-in-transit, a treatment plan needs to be determined on a case-by-case basis. Therapeutic options were anticoagulation therapy with heparin and lifelong warfarin, thrombolysis, or surgical embolectomy [4]. Although surgical thromboembolectomies are associated with fewer complications of recurrent embolic events, there is a risk of intra- and postoperative mortality and morbidity.

Anticoagulant treatment is a good alternative to surgery, particularly for patients with comorbidities (e.g., increased age, stroke, cancer) who are at high surgical risk and for patients with a small PFO, while thrombolysis carries the highest mortality of all.

In a thrombus as big as reported here, anticoagulation therapy bears a high risk of either fragmentation or complete embolization causing a stroke or peripheral emboli [4].

Moreover, in our case, a shift of the entrapped thrombus into the left atrium had been detected. Since the pulmonary artery pressure was high, time was running out to prevent the thrombus from entering the systemic circulation and causing neurological events.

Currently, there are no established guidelines for treatment of the combination of pulmonary embolism with thrombus-in-transit. Studies show an advantage of surgical over medical treatment due to a significantly reduced risk of further systemic embolism and mortality, considering age and comorbidity [5]. Another advantage is the opportunity of treating pulmonary embolism and the entrapped thrombus within the same operation.

In our case, the thrombus-in-transit could be removed completely without fragmentation. We were also able to extract several large thrombus segments from both main pulmonary arteries (Trendelenburg’s operation) and perform a surgical closure of the patent foramen ovale.

This is an extreme case of a large thrombus-in-transit with imminent paradoxical embolism through the patent foramen ovale.

Gradual migration of the thrombus demonstrates the importance of rapid decision-making and treatment for such patients. There is no strict medical consensus about the best treatment, but in our case, the embolectomy appeared to be the best approach, considering the imminent right heart failure and the patients’ shifting thrombus.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Laverde-Sabogal CE, Torres-González JV. Impending paradoxical embolism, patent foramen ovale and pregnancy. Case Rep Colomb J Anesthesiol. 2018;46(1):79–83.

Bartlett MA, Mauck KF, Daniels PR. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;17(11):461–77.

Miranda B, Fonseca AC, Ferro JM. Patent foramen ovale and stroke. J Neurol. 2018;265(8):1943–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-8865-0.

Othman M, Briasoulis A, Afonso L. Thrombolysis for Right Atrial Thrombus-in-Transit in a Patient With Massive Pulmonary Embolism. Am J Ther. 2016;23(3):e930–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000000083.

Ellensen VS, Saeed S, Geisner T. Haaverstad R. Management of thromboembolism-in-transit with pulmonary embolism. Echo Res Pract 2017;4(4):K47-K51. Retrieved Feb 22, 2022 from https://erp.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/echo/4/4/K47.xml

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

The patient has consented to participate.

Consent for Publication

The patient has consented to the publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Medicine

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (MP4 2.34 MB)

Supplementary file2 (MP4 2.45 MB)

Supplementary file3 (MP4 2.42 MB)

Supplementary file4 (MP4 14.1 MB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kronberg, K., Schwarz, A.K., Faist, D. et al. Transit Thrombus in a Patent Foramen Ovale — Time Is Running Out: a Case Report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 88 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01426-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01426-y