Abstract

University and college students present specific health issues with vulnerabilities related to mental health and sexual health, risk-taking behaviors, and delayed access to primary care. A new student outpatient clinic was created in September 2016 at Geneva University Hospitals to respond to the health needs of this population. We present here the clinical management framework developed for a primary care consultation with students. A 3-step approach (ABC) was designed by expert consensus using different sources. A post-consultation satisfaction survey was conducted among students attending the clinic. The approach proposed 3 steps comprising general information, social evaluation, and preventive care. The importance of offering modern means of communication (online appointments, email exchanges with clinicians) was emphasized by experts. The question of cultural identity and connectedness was also addressed, especially for international students or those coming from a different Swiss region. In November 2018, a survey conducted among 128 patients out of 449 consultations showed that 94.5% agreed or totally agreed to recommend the consultation to fellow students, and 89% considered that care providers adequately addressed their specific student-related issues. A specific approach is needed in primary care for university/college students requiring particular competences across several domains. Our findings suggest that our approach is effective to cover the main health challenges faced by students. A comparison of the outcomes of this novel 3-step primary care consultation approach with non-structured approaches should be evaluated in future studies, including clinician’s satisfaction, elements of patient’s participation to governance, and medico-economic aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines young people as those aged between 10 and 24 years old divided into the following subgroups: adolescence from 10 to 19 years and youth between 15 and 24 years, although there is some debate on the actual definition of adolescence [1, 2].

Adolescence and young adulthood represent a key period, not only for physical changes but also for social development, media and peer engagement, as well as the acquisition of patterns of health and health risks [3].

While the end of childhood is marked by the menarche or spermarche, the transition to adulthood is characterized by parenthood and/or financial independence. The duration between these two periods is currently increasing, especially in high-income countries, and is increasingly the result of extended education, changes in social norms around marriage and parenthood, and the availability of effective contraception, particularly in industrial societies [4]. Due to the variability in this transition period, young adults represent a diverse population that includes students, young workers, unemployed, and marginalized young people.

Although young adults are often considered to be healthier than older adults, they present specific social and medical issues, which may impact on their immediate or future health and well-being. In a global context, just over one-half of adolescents grow up in multi-burden countries, characterized by high levels of all types of adolescent health problems, including HIV, other infectious diseases, undernutrition, poor sexual and reproductive health, injury and violence, and non-communicable diseases. The latter include mental and substance use disorders and are becoming the dominant health problem of this age group [5]. In addition, young adults also demonstrate high levels of suicides, car accidents, accidental drowning, accidental poisoning by and exposure to noxious substances, as well as assaults and falls.

The health-related behaviors of university students are a concern, especially regarding physical activity, an unbalanced diet, and alcohol and tobacco use, associated with low mental well-being. Of note, eating disorders are prevalent in the student population, and physicians should search for current or former eating disorders during adolescent as they can persist afterwards [6]. Transition to a new life, the university environment and systems, financial difficulties, academic pressure, and lack of health promotion are further issues that may negatively impact their health [7].

Although mental disorders, suicidal thoughts, and health-compromising behaviors are common among university students, most students experiencing these problems remain untreated [8]. In addition, students often have relatively limited financial means and may thus be reluctant to seek health care if it is not free of charge.

Global student mobility is also a fast-growing phenomenon. International students comprise an increasingly large proportion of those in higher education. They often experience additional level of stress due to acculturation issues, and this group needs to benefit from specific care [9]. They are often found to be at increased risk of several adverse health outcomes while also being less likely to seek help for mental health and related problems; this is particularly true for male students [10].

In Switzerland, approximately 20% of patients aged between 15 and 29 years old report having a chronic condition [11].

Of note, the current prevalence of anxiety, depression, and ADHD symptoms in young Swiss adults seems higher than many international estimates [12].

The PRISM-Ado study, exploring why young people consult a family doctor in the French-speaking region of Switzerland, reported that general and unspecific reasons for encounter were the most common in boys (44 %) and girls (42 %), followed by respiratory, musculoskeletal, dermatological, and psychological reasons. Psychological reasons were more frequent in girls attending urban practices, and musculoskeletal and dermatological reasons were more frequent in rural areas [13]. Regarding substance use, in a cohort of 4778 young Swiss men, 30.9% reported cannabis use at age 21, 9.5% initiated use between age 21 and 25 years, and around 10% had ceased by age 25 [14].

To our knowledge, there is no national survey available in Switzerland describing the health or burden of disease among Swiss university students, including access to health care, and whether it differs at university and also between domestic and international students.

Therefore, we consider that there is a need for accessible, targeted, culturally sensitive health promotion early intervention programs and dedicated outpatient clinics for students (local or international), as well as the further development of research in this field.

Health care models for university students in Switzerland rely mostly on first-line primary care nurses who then refer patients to their family doctor or an outpatient clinic, if needed. However, we were unable to identify an established network of nurses, general practitioners, gynecologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists experienced in young adult medicine and organized around the specific health needs of students. Although no data are available, we observed that most students do not have a family doctor for various reasons: (i) foreigners initially are not knowledgeable of the Swiss medical system and wait for a medical issue to occur before seeing a doctor, (ii) extra-regional students may have a family doctor but located far from their new place of study and accommodation, or (iii) some may have not seen a doctor since their last pediatric check-up at age 16.

In the French-speaking region of Switzerland, students seeking such a multidisciplinary approach can attend the adolescent medicine clinics attached to two major university hospitals, but we believe that the specific needs of this population call for a more focused approach.

The Geneva region has around 18,000 university-level students present at multiple campus sites. Currently, the University of Geneva offers a medico-social unit coordinating preventive actions for the student community, adjusted curricular and test conditions for those with specific medical conditions, and access to psychologists. In a 2013 longitudinal survey at Geneva University, 10% of the 1693 participating students declared they needed help to solve a health issue or to talk about it [15]. In addition, 14% decided against seeing a health care professional in the last 12 months for financial reasons. Of note, 41.4% of respondents were foreigners, and 53% of students held a part time job in addition to their studies.

In 2017, there were approximately 17,000 consultations at the Division of Primary Care Medicine of Geneva University Hospitals concerning patients aged 18 to 30 years old. Approximately one-half attended ambulatory emergency care, representing 30.2% of all patients in that sector. According to our emergency room records, the five main diagnoses presented by this age group in emergency care were trauma, skin conditions, superficial wounds, abdominal pain, and arthralgia/myalgia/neuralgias.

Through our experience in the primary care division, we identified students’ health needs and behaviors (emergency use, lack of knowledge of the health system, lack of access to health services, cultural barriers, and young adults’ specific barriers).

To address these needs, we developed a multidisciplinary consultation in partnership with key stakeholders at the hospital, university, and in the community. The proposed services included adolescent health, addiction medicine, psychiatry, violence prevention, sexual and reproductive health, dental health, nutrition, and social evaluations.

Methods

The study describes the development of an accessible clinical management framework for students at Geneva University Hospitals and the guidelines established to improve quality of care for this population. The general internal medicine clinic dedicated to students was housed within our primary care department and financed by our institution. The team included a head physician specialized in adolescent and young adult medicine, a dedicated receptionist, two medical residents, and other senior physicians in internal medicine. The consultation’s head physician was in charge of the training offered to clinicians and reception staff to improve youth-friendly practice and service delivery. He regularly benefited from case-study discussion with other adolescent and young adult medicine specialists and the local network of youth services.

Fees levied for the consultation were according to the Swiss “TARMED” system for outpatient services which consists of an encoding system in which a medical consultation is split into a series of codes, with each code corresponding to a number of points. Each point has a different value depending on the Swiss region. The cost of a consultation was approximately 180 Swiss francs (US$ 197) for 45 min with a clinician and was eligible for reimbursement, depending on the patient’s insurance franchise. This is the same rate applied by primary care specialist in the same region.

Improving Access to Primary Care for Students

The published literature suggests that the emerging use of digital clinical communication (e.g., video consultation, web messaging, or emails) may improve the involvement of families and caregivers in the health management of young people [16]. An online appointment website, widely advertised and accessible through the university system, with possibilities to contact physicians by emails, was first developed with positive feedbacks by students. We therefore advised care givers to ask for student’s preferred means of communication to ensure an appropriate follow-up after the first consultation.

As health care professionals and patients in Geneva are culturally diverse, cultural awareness was also a challenge in the creation of this consultation. The head physician was also trained in that regard by a transcultural consultant. Almost one-half of our patients came from a foreign country, and therefore, it was important to assess their sense of connection when asking about family support, peers, social networks, and pillars of resilience. Of note, health care professionals at Geneva University Hospitals are very sensitive to transcultural approaches as Geneva is a city with many international organizations and clinical transcultural consultations have already been created in several specialties, such as obstetrics.

To effectively address the health needs of young adults, we identified the need to offer information on their rights as patients and how to efficiently use primary care services. Indeed, it was often the first time that the patient had consulted without parents or exposed to a new and different model of consultation. Particular attention was given to explain usual procedures and the reason for them. For instance, the clinical examination was needed to be commented upon and was considered an opportunity to raise questions (about body image, scarification and tattoos, or physical sensations, e.g., palpitations and hygiene).

The ABC of Primary Care for Students: a 3-step Structured Approach

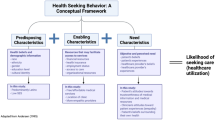

To guide the primary care physician, we developed a 3-step approach to be used by any general practitioner/family doctor encountering a student in their consultation (Fig. 1).

One of the main inspirations of this approach was the HEADSS (home, education, activities/employment, drugs, suicidality, sex) psychosocial assessment framework (adapted from Goldenring and Cohen, 1988) cited in the World Health Organization documents and used by internationally recognized adolescent health institutions. HEADSS forms the basis of the adolescent health framework within our institution and has been taught at the pre- and postgraduate level for more than a decade within our medical faculty. All medical and nursing staff trained in Geneva have at least a basic knowledge of the use of the HEADSS when communicating with adolescents [17].

Our “ABC” approach was constructed using different sources involving literature reviews, pre-established guidelines, and through a consensus of 14 professionals and experts from the interdisciplinary network presented previously. It was then approved by the clinical strategies committee of the Division of Primary Care at Geneva University Hospitals.

A pre-requisite of any consultation is to be responsive to the student’s main request (e.g., chronic fatigue) and then to explore his/her knowledge of health insurance system (including premiums, deductible expenses) in order to inform and anticipate the financial implications of health care. At our consultation, the aims of any first contact with a young adult are to identify and answer the patients’ main reason for consulting, address sensitive topics, detect the patient’s hidden agenda, and seize the opportunity to talk about prevention for issues such as immunization, risk-taking situations, sports, and driving.

Tables 1, 2, and 3 show different domains that the clinician should explore and propose specific questions to help the clinician. Some of the domains presented in the tables are developed further.

General Information (Table 1)

We advise to welcome the patient in a youth-friendly environment with a non-judgmental attitude, explaining that further questions are asked in order to understand her/his health in a better way. Information about confidentiality should also be emphasized.

The first step is to elicit a wide spectrum of general information (reason for consultation, medical history, allergies, and treatment) before exploring the specific issue brought by the patient.

The primary care physician should search for frequent or possibly serious conditions during adolescence such as asthma, scoliosis, and sexually transmitted diseases. For example, a negative chicken pox history could be an opportunity to propose a specific immunization to avoid risks related to this disease during adulthood (pneumonia, risks during pregnancy). Additionally, it seems that some students participate in clinical trials for financial reasons; therefore, exposure to X-ray or trial medications should be searched for.

Social Evaluation (Table 2)

The second step is to evaluate the patient’s social context. We propose exploring the following items: academic background and trajectory, social network, health care access and providers around the patient, financial resources, gender identity, and sexual orientation.

The Swiss health care system is one of the most expensive in the world with one of the highest out-of-pocket payments by patient [18]. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the patient’s economic situation and his/her access to health care and understanding of the modalities of reimbursement, especially if the student is from a foreign country. For example, the question “Did you have difficulties paying your household bills during the last 12 months?” is a highly effective screening question to identify patients at risk of foregoing health care [ 19].

A sense of belonging to a lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer (LGBTIQ+) identity in adolescents and young adults has been associated with a decrease in health-related quality of life and higher levels of mental health issues (e.g., depression, anxiety, suicides) [ 20]. While understanding gender diversity and sexual orientation among students might be challenging for health care professionals, a guide written by the American Psychological Association can help understand key concepts and terms [21].Improving physicians’ recognition of their own heteronormative value system and addressing structural heterosexual hegemony will help to make health care settings more inclusive [22].

Preventive Care (Table 3)

The last step is to propose targeted preventive care. We propose 10 items: immunization status, nutrition, oral health and ophthalmology, risk-taking evaluation, substance use or abuse, addictions without substance, exposure/perpetration of acts of violence, mental health, and sexual and reproductive health.

Among substance use, it is important to explore possible binge drinking (defined in Table 3), excessive use of energy drinks and alcohol-mixed energy drinks, also frequently used among high school adolescents [23]. Interventions about these behaviors should be proposed to promote awareness about possible related risks. The NIDA Quick Screen might be useful in order to screen for drug use in general medical settings [24]. Using self-prescribed medications is also a relevant issue as they can be used against anxiety, for weight loss, or to enhance performance (e.g., methylphenidate), sometimes with a potential impact on driving [25].

Behaviors related to health range across a broad spectrum and screening should include heterogeneous domains. For example, online activities may be explored in order to screen for Internet or online game addiction [26]. However, this is an area where clear definitions of risk levels are still lacking [27].

Sexual and contraceptive behaviors are also changing as well and need to be addressed during the consultation [ 28]. Polycystic ovary syndrome has to be searched for given its important impact on quality of life and the opportunities for improvement by appropriate management [29].

The Adolescent Binge Eating Scale questionnaire is a potential screening tool to identify adolescents with obesity at high risk of binge eating disorders and to guide referral to a specialist to clarify the diagnosis and provide adequate care [30]. It is important to consider the quality of diet (possibility of fast-food habits) to search for food intolerance and possible food supplements taken by students.

Results

Evaluation of the 3-Step ABC Approach

We implemented this 3-step strategy at the consultation for students of the Geneva University Hospitals’ Primary Care Division. The consultation, available in French and English, was launched in September 2016 with an online access for appointments. By November 2018, six residents in general internal medicine were trained, and two were being trained through participation at the consultation with the post hoc supervision of each case by the head physician.

We conducted a post-consultation satisfaction survey, data being anonymized, among 128 patients (response rate=28.5%). Overall, 94.5% recommended the consultation to fellow students, 95.3% intended to continue follow-up at the consultation, and 89% felt that care providers adequately addressed their specific student-related issues. Of note, 93% of them obtained the desired information from their physician and 94.5% reported that the doctor had explained each aspect of the consultation.

In the free comments section, students stated that they appreciated the time taken for a first consultation (45 min on average, which could be longer than an average time of consultation in general practice in a different country) and that the questions asked about their health and lifestyle were relevant. Negative comments ranged from suggestions to improve the waiting room to a better coordination between the online appointment system and our institutional system due to a lack of synchronization between the two platforms.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our approach is the first one to develop a structured clinical framework specifically for student-patients in Switzerland, although it has only been clinically used in French and English. Therefore, it needs to be translated into all the Swiss national languages (i.e., German and Italian) to test the program and provide access to it for other students in the Swiss Confederation. Furthermore, while the approach has been used in a university hospital outpatient clinic, it would benefit from testing for relevance in other primary care settings (private offices, medical centers, etc.) and by other health professionals (e.g., nurse practitioners). Some elements of this approach might also benefit a wider population of young adults.

This type of service benefits from continuity with existing adolescent health clinics in Geneva as the head physician was also a senior physician at Geneva University Hospitals adolescent health clinic (treating young people aged between 12 and 25 years), thus facilitating the link between specialists in this field. Our consultation was in complementarity since many students are aged over 25 years. The other adolescent health clinic in the French-speaking region of Switzerland is in Lausanne (60 km away) and accepts patients between the ages of 12 and 20 years. To our knowledge, apart from our consultation, there are no dedicated services for students elsewhere in Switzerland.

In France, students benefit from a one-time preventive medicine consultation during the first 3 years of university, but modalities vary regarding this process (telephone consultations, self-administered questionnaires, 10-min consultations). On North American campuses, dedicated health clinics can be found with physicians, nurses, counselors, and physiotherapists. Given the needs of the student population and their vulnerability, especially related to mental and sexual health, it is essential that such services be offered to every student if needed, including equity of access irrespective of sex, ethnic, or socioeconomic status. Importantly, international students and those from other regions of the country should be targeted through communication tools to heighten their awareness of this type of health services.

The complexity of the approach relies on the economic feasibility: adolescent and young adult medicine consultations exploring several dimensions of health can last between 45 and 60 min. They are often performed by a senior physician with specific training, thus generating a cost for the institution that can be higher than the fee of the actual consultation. In order to be sustainable, these kinds of services require a public financial support or the integration of costs into a departmental or institutional budget.

Further evaluation should include medico-economic studies, clinician satisfaction surveys, and pedagogical evaluations. Patient participation in the governance of this new type of health services would also bring useful developments regarding the concept of health democracy.

Conclusion

A specific approach is needed in primary care for university students and requires specific knowledge and skills in several domains. Through the 3-step structured approach, we intend to cover the main health issues encountered by students and improve their health management. More evidence is needed to support management decisions in many domains related to this age group. Outcomes related to this approach should be compared in the future to non-structured approaches of student primary care in order to add much-needed evidence to improve health care in this particular population.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Definition of adolescence. Geneva: WHO. 2021. https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health/#tab=tab_1. Accessed 9th February 2021.

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2:223–8.

Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, et al. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2012;379:1641–52.

Patton GC, Olsson CA, Skirbekk V, Saffery R, Wlodek ME, Azzopardi PS, et al. Adolescence and the next generation. Nature. 2018;554:458–66.

Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387:2423–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1.

Murray HB, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, Herzoq DB, Franko DL, Eddy KT. Will I get fat? 22-year weight trajectories of individuals with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50:739–47.

Aceijas C, Waldhäusl S, Lambert N, Cassar S, Bello-Corassa R. Determinants of health-related lifestyles among university students. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137:227–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913916666875.

Ebert DD, Mortier P, Kaehlke F, Bruffaerts R, Baumeister H, Auerbach RP, et al. Barriers of mental health treatment utilization among first-year college students: first cross-national results from the WHO World Mental Health International College Student Initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2019;28:e1782. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1782.

Ogunsanya ME, Bamgbade BA, Thach AV, Sudhapalli P, Rascati KL. Determinants of health-related quality of life in international graduate students. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10(4):413–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2017.12.005.

Skromanis S, Cooling N, Rodgers B, Purton T, Fan F, Bridgman H, et al. Health and well-being of international university students, and comparison with domestic students, in Tasmania, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061147.

Eurostat, 2013. Young people (aged 16-29) suffering from a long-standing illness or health problem by sex. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Being_young_in_Europe_today_-_health. Accessed 28 Sept 2018.

Werlen L, Puhan MA, Landolt MA, Mohler-Kuo M. Mind the treatment gap: the prevalence of common mental disorder symptoms, risky substance use and service utilization among young Swiss adults. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1470. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09577-6.

Meynard A, Broers B, Lefebvre D, Narring F, Haller DM. Reasons for encounter in young people consulting a family doctor in the French speaking part of Switzerland: a cross sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:159. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0375-x.

Deligianni ML, Studer J, Daeppen JB, Gmel G, Bertholet N. Longitudinal associations between life satisfaction and cannabis use initiation, cessation, and disorder symptom severity in a cohort of young Swiss men. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16081372.

Geneva Students Life Observatory. Données de l’observatoire de la vie étudiante à Genève. University of Geneva, 2021. https://www.unige.ch/dife/observatoire. Accessed 9th February 2021.

Armoiry X, Sturt J, Phelps EE, Walker CL, Court R, Taggart F, et al. Digital clinical communication for families and caregivers of children or young people with short- or long-term conditions: rapid review. Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e5.

Parisi V, De Stadelhofen LM, Péchère B, Steimer S, De Watteville A, Haller DM, et al. Apport du guide d’entretien HEADSSS dans l’apprentissage de la démarche diagnostique avec un adolescent : Perspectives d’étudiants lors de cours à option interprofessionnels [Using the HEADSSS guide to teach students diagnostic skills in adolescent health Views from students participating in interprofessional courses]. In French Rev Med Suisse. 2017;13:996–1000.

De Pietro C, Camenzind P, Sturny I, Crivelli L, Edwards-Garavoglia S, Spranger A, et al. Switzerland : health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2015;17:1–288.

Bodenmann P, Favrat B, Wolff H, Guessous I, Panese F, Herzig L, et al. Screening primary-care patients forgoing health care for economic reasons. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94006. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094006.

Gordon AR, Krieger N, Okechukwu CA, Haneuse S, Samnaliev M, Charlton BM, et al. Decrements in health-related quality of life associated with gender nonconformity among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:2129–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1545-1.

American Psychological Association. Key terms and concepts in understanding gender diversity and sexual orientation among students. Informational Guide 2015. https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/programs/safe-supportive/lgbt/key-terms.pdf. Accessed 9th February 2021.

Law M, Mathai A, Veinot P, Webster F, Mylopoulos M. Exploring lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) people’s experiences with disclosure of sexual identity to primary care physicians: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0389-4.

Scalese M, Denoth F, Siciliano V, Bastiani L, Cotichini R, Cutilli A, et al. Energy drink and alcohol mixed energy drink use among high school adolescents: association with risk taking behavior, social characteristics. Addict Behav. 2017;72:93–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.03.016.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse website. The NIDA Quick Screen. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/resource-guide-screening-drug-use-in-general-medical-settings/nida-quick-screen. Accessed 9 February 2021.

Jeffers AJ, Benotsch EG, Green BA, Bannerman D, Darby M, Kelley T, et al. Health anxiety and the non-medical use of prescription drugs in young adults: a cross-sectional study. Addict Behav. 2015;50:74–7.

Lima ML, Marques S, Muiños G, Camilo C. All you need is Facebook friends? Associations between online and face-to-face friendships and health Front Psychol. 2017;8:68.

Berchtold A, Akre C, Barrense-Dias Y, Zimmermann G, Suris JC. Daily internet time: towards an evidence-based recommendation? Eur J Pub Health. 2018;28:647–51.

Holway G, Hernandez S. Oral sex and condom use in a US sample of adolescents and young adults. Adolesc Health. 2017;62:402–10.

Kaczmarek C, Haller DM, Yaron M. Health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:551–7.

Chamay-Weber C, Combesure C, Lanza L, Carrard I, Haller DM. Screening obese adolescents for binge eating disorder in primary care : the Adolescent Binge Eating Scale. J Pediatr. 2017;185:68–72.

Acknowledgements

We would like to warmly thank all the professionals who participate in the development of our consultation and its network including Professor Barbara Broers and Drs. Anne Meynard, Thierry Favrod-Coune, Logos Curtis, Cédric Devillé, Sophia Achab, Emmanuel Escard, Michal Yaron, Isabelle Navarria-Forney, Jean-Pierre Carrel, and Natacha Abbet and Ms. Lorenza Bettoli Musy, Jezabel Caliri, and Sandy Moreno. We particularly thank Anne Guillaume and Rosemary Sudan for their help in the final reading of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.P, M.D., Y.J., F.N., JM.G., and I.G. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results, and to the writing of the manuscript. B.C, DS.C., DM.H., and T.F. provided critical feedback and helped shape the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Data for the survey was anonymized. This study was considered as falling outside of the scope of the Swiss legislation regulating research on human subjects, so that the need for local ethics committee approval was waived.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Note of Transparency

The 2019 SGAIM (Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine) conference included a communication by the authors on this article topic, based on earlier work.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Medicine

Supplementary Information

Additional File 1.

Orman Internet Stress Scale self-questionnaire. Questionnaire assessing internet addiction. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional File 2.

Lie Bet questionnaire. Screening for pathological gamblers. (DOCX 13 kb)

Additional File 3.

ADRS self-questionnaire. Adolescent Depression Rating Scale. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional File 4.

SCOFF questionnaire. Screening tool for eating disorders. (DOCX 13 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pernin, T., Dominicé Dao, M., Cheval, B. et al. The ABC of Primary Care for University Students: a 3-Step Structured Approach at Geneva University Hospitals. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 3, 1870–1880 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00926-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00926-z