Abstract

The purpose of this study was to use meta-analysis to assess the rates of bullying victimization in the United States (US) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using a systematic search of academic databases and a previous meta-analysis database, we collected studies published between 1995 and 2023. Included studies used US-based data and reported on bullying involvement rates among children/adolescents across at least two data points (years), where 1 year had to be from 2020 to 2023. Data were extracted by type of bullying, gender, race, grade level, as well as numerous study-level features. Analyses included random effects meta-analyses, meta-regressions, and moderator analysis. Findings across the 79 studies and 19,033 effect sizes indicate that reported rates of traditional bullying victimization were significantly lower during the COVID pandemic years of 2020 to 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic years (23% vs 19%). This pattern was reflected across gender, grade, and most racial/ethnic groups examined. Overall, rates of cyberbullying victimization remained similar pre-pandemic vs during COVID (16% vs 17%). However, for boys, American Indian/Alaska Native youth, Asian, multi-racial, and White youth rates of cyberbullying victimization were significantly higher during COVID compared to the pre-pandemic period, while rates were significantly lower for transgender/non-binary youth during COVID (39% vs 25%). In addition, we conducted a moderator analysis and used meta-analysis to calculate pooled rates by year. Findings inform the current state of bullying involvement in the US and have implications for school-based bullying prevention practices and policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the United States (US), approximately 20% of youth experience bullying victimization regularly, while fewer than 10% perpetrate it (Lebrun-Harris et al., 2019, 2020). Bullying is defined as the deliberate harm of an individual repeatedly, with intent, and where a real or perceived power imbalance exists between the victim(s) and the perpetrator(s) (Gladden et al., 2014). Bullying can be relational, including behaviors such as rumor spreading or social exclusion. It can be verbal, consisting of behaviors such as name-calling, threatening, or teasing, and it can be physical, which could include kicking, hitting, or pushing. Bullying can take place in-person, referred to here as traditional bullying, or online, in the form of cyberbullying, which is verbal or relational bullying in a virtual space, such as texting, social media apps, or email (Gladden et al., 2014).

Rates of bullying involvement vary considerably by type, age, and gender (Kennedy, 2021). In general, rates of traditional bullying victimization leveled out in the 2010s, with no significant upward or downward trend, while rates of reported cyberbullying victimization have continued to climb (Kennedy, 2021). However, in 2020, the world changed — a virus, colloquially called COVID-19, started to spread, and the world shut down. As a result, schools closed, and many switched to remote learning (Zviedrite et al., 2021). This meant that students no longer attended school and only interacted with each other over the Internet. Fewer in-person interactions led to the inevitable question, “What does this mean for bullying?” The current meta-analysis answers this question by examining trends in bullying involvement both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

Research on the Impact of COVID-19 on Traditional and Cyberbullying

The few studies that have examined bullying rates during the COVID-19 pandemic (Barlett et al., 2021; Patchin & Hinduja, 2023; Schilling & Wang, 2023; Vaillancourt et al., 2021) found that traditional bullying victimization declined when students were no longer in school (Repo et al., 2022; Vaillancourt et al., 2021). In particular, there was a concern about rising rates of cyberbullying due to increased time online and fewer in-person interactions (Kahn, 2020; Kee et al., 2022). Though minimal research has examined this effect for youth (a few studies have examined it in adults), studies from the US (Patchin & Hinduja, 2023) and Norway (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022) confirmed this finding. However, a study of Korean adolescents found a decrease in cyberbullying during the pandemic (Shin & Choi, 2021). This inconsistency is likely due to differences in the pandemic years studied and/or the geographic location of the study. The studies that found a decrease during the pandemic compared 2019 to 2020 (Shin & Choi, 2021), while the studies that found an increase compared 2019 to 2021 (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022; Patchin & Hinduja, 2023). By 2021, while far from over, most youth had returned to in-person school and were interacting with peers regularly again. This is important as cyberbullying is largely understood as an extension of in-person bullying rather than its own distinct experience (Kowalski et al., 2023; Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015).

In addition, there are likely cultural differences in how different geographical locations responded to the pandemic, particularly regarding cyberbullying. In a meta-analysis, Huang and colleagues (2023) examined the impact of COVID-19 on cyberbullying globally. They found a decrease in cyberbullying overall and cyberbullying perpetration, yet hypothesized that cultural factors, such as “Confucian responsibility thinking”, which refers to the strong social responsibility to care and have concern for others and the state (Wang et al., 2022), might be a positive coping strategy that could lessen the impact of the pandemic on individuals from Eastern cultures. In contrast, they speculated that individual consciousness, which is more typical in Western cultures, might encourage or bolster bullying behaviors. This indicates a need to examine the effects of the pandemic more closely within specific geographic locations, where cultural variations might be lessened.

How Meta-Analysis Can Be Used to Better Understand Bullying Trends

In addition to Huang and colleagues’ (2023) global meta-analysis, one systematic review has been published that examined bullying before and during the pandemic (Vaillancourt et al., 2023). Vaillancourt and colleagues (2023) found considerable variation across studies. They attributed this to methodological differences, such as the use of cross-sectional research and the wide range of geographic locations. This kind of heterogeneity is common across the bullying literature. Meta-analysis can be used to combat heterogeneity across bullying studies. First, longitudinal or repeated measures cross-sectional design articles can be selected, thus allowing for the consideration of both between-study and within-study differences, for example, including articles that collected data on rates of bullying both before and during the pandemic. Second, to reduce certain types of heterogeneity and increase practical and policy implications, meta-analysis can focus one geographic region, such as the US. Rates of bullying and experiences of bullying tend to vary from location to location, especially between places where there are pronounced cultural or sociodemographic differences (Bradshaw et al., 2017). This is also demonstrated in the literature on bullying prevention programs, where programs developed in countries with lower racial and socioeconomic diversity are less effective at reducing bullying in more diverse countries (Evans et al., 2014; Kennedy, 2020a, b). Third, to reduce the effects of publication bias, a meta-analysis can include studies from reports, dissertations, and other non-peer-reviewed high-quality sources. This allows for the inclusion of other forms of literature and datasets that might not be included in the published academic literature. Fourth and finally, meta-analysis can account for study-level differences in the form of moderators, which can be utilized in subgroup analyses or in meta-regression models. Moderator analyses can help us better understand how study-level features, such as the time frame of the bullying question (e.g., In the past 30 days or in the past 12 months…), impact the reported rates of bullying. This is important as the time frame, the bullying question, and whether a definition is provided often vary from study to study (Kennedy, 2021; Vaillancourt et al., 2023).

Current Study

While the limited research on bullying before and during the COVID-19 pandemic is inconsistent, it is possible to use meta-analysis to help clarify these inconsistent findings. The current review uses meta-analysis to examine trends in rates of traditional and cyberbullying victimization in the US before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, we use meta-regression to examine traditional and cyberbullying victimization in the pre-COVID years compared to the COVID years (2020–2022). Second, given rates of bullying victimization tend to vary by gender, age (Kennedy, 2021; Pontes et al., 2018), and race (Pontes et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2020), we explore trends by grade, race, and gender. Third, we use meta-analysis to pool rates by year to see what the actual trends look like — to examine how pooled rates might vary for each pandemic year. Fourth and finally, given differences in study-level features, we conducted a moderator analysis meta-regression to assess the impact of various study-level features.

Methods

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to examine trends in bullying involvement before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In order to do this, we conducted a systematic search of three academic databases (Masterfile Premier, ERIC, and PsycINFO) using three search term combinations: (1) (bully* OR cyberbully*) AND (trend* OR time trend OR time); (2) (peer victim* OR peer perp) AND (trend* OR time trend OR time); (3) (school victim* OR school perp*) AND (trend* OR time trend OR time). This systematic search and meta-analysis was an extension of a previous systematic search (Kennedy, 2021) that examined bullying trends in studies published from the mid-1990s through early 2017. For this study, we extended the original systematic search to include articles published from January 2017 to May 2023. In addition to the systematic search, we checked (via websites and online data portals) for updated versions of all studies that used repeated measures cross-sectional data (e.g., Youth Risk Behavior Survey) in the original meta-analysis. This meta-analysis protocol is registered in Prospero (CRD42022366906).

Inclusion Criteria

There were five primary inclusion criteria. First, data must have been collected in the US. Second, studies must have used quantitative research methods. Third, studies must have at least two data points (event rate) that represent different years, and one of those years must be 2020 or later. This means that all studies must be repeated measures cross-sectional or longitudinal data that have data points from both the pre-pandemic period and the pandemic period. Fourth, the participants must be school-aged — approximately age 18 and under. Fifth, we excluded studies that focused on clinical or treatment populations and those with samples that focused exclusively on youth with non-traditional development, such as autism or a developmental delay.

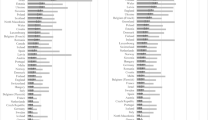

Article Selection Process

Three reviewers completed both abstract and full-text reviews in Rayyan QCI (Author 1, Author 2, and a research assistant). Reviewers maintained high agreement and discussed disagreements not resolved upon re-review by the first author. After the systematic search and review of studies from the original meta-analysis, we had a final analytic sample of 78 studies (see Fig. 1 for a flowchart outlining each step of the review process and reasons for exclusion at the full-text and data extraction phases). We used the 9-question Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist (JBIC) (Munn et al., 2020) criteria for prevalence studies to assess study quality. We scored all the studies and found that all were of good quality. The checklist included questions about the sampling frame, the sampling method, the sample size, the study setting, the assessment of the condition (i.e., how bullying was assessed), the statistical analysis, and the response rate. It was scored as “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, and “not applicable.” We had three studies score “unclear” on providing adequate detail of the study setting; otherwise, all studies scored “yes” on the criteria included.

Data Extraction and Coding

Using a modified (to include transgender/non-binary and race) coding scheme originally developed by Author 1, three reviewers participated in the data extraction process. Author 1 extracted and coded all the data: the 15 studies from the new systematic search, the 12 studies from other sources (new YRBS locations), and the 64 studies from the previous meta-analysis, to include updated years and data on race and gender. Author 2 and a research assistant coded the studies (n, 15) from the systematic search. Disagreements were reviewed by Author 1 and as a group, if necessary. For intra-rater reliability, Author 1 recoded all studies a second time (n = 79), and for inter-rater reliability, Author 2 recoded a systematic random selection of studies (from the whole sample).

Primary Effect Size

Crude prevalence estimates of traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying victimization (and by gender, race, and grade) were extracted from each study for each year of data collection, as well as the sample size. We extracted multiple effect sizes for each study, ranging from 21 effect sizes (Patchin & Hinduja, 2023) to 891 effect sizes for the Minnesota Student Survey (Minnesota Department of Education, 2022).

We assessed two forms of bullying victimization: traditional bullying victimization, which refers to in-person forms of bullying captured in a general question about bullying, and cyberbullying victimization, which refers to bullying that takes place in an electronic space. These were coded as yes/no. Studies assessed responses to bullying questions as “yes” or “1 or more times” within a given period.

Gender was coded as boy, girl, boy and girl, and transgender/non-binary. Race/ethnicity was coded into nine categories: race-all, which represents all racial/ethnic groups; American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN); Asian; Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/Asian (NH/PI/A); non-Hispanic Black; Hispanic; non-Hispanic White; multi-racial; and other. We made every attempt to maintain the categories that were represented in the included studies, which is why Asian is both its own category and is grouped with NH/PI/A. However, we had a very small representation of both “other” and Middle Eastern/North African, so we collapsed this category, which was ultimately excluded from our analysis due to size. It is important to note that for gender and race, the boy and girl category and the race-all category are not aggregates of the individual gender and race categories, respectively. Instead, some studies reported rates disaggregated by race and gender, while others did not — so while some of the data in the boy and girl and race-all categories are aggregates of the individual categories, some are not — meaning the findings are unique. For grade, we have two broad groups that roughly represent US middle school (5th grade to 8th grade) and US high school (9th grade to 12th grade). Bullying involvement, gender, and race were all self-reported measures.

In addition, we extracted data on multiple study-level moderators, most notably, COVID, a variable that divides the year of data collection into before 2020 (< 2020) and after 2020 (2020-2022). Others included the following: whether the word “bully” was included in the survey question (yes/no), the time frame of the bullying question (past 30 days, past 12 months), the frequency of the reported bullying (1+ times, 2+ times), whether a definition of bullying was provided (yes/no), if the definition addressed power dynamics (yes/no), if the definition addressed repetition (yes/no), the type of article (peer-review, dissertation, report), the modality of the survey (self-report, teacher report, peer nomination), and the study region in the US based on census groupings (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, National) (US Census Bureau, 2023).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata 18 (StataCorp, 2023). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) software (Borenstein et al., 2022) was used to convert event rates into logit event rates and calculate the weights and variance. Weights were determined using the inverse variance method (Borenstein et al., 2009), which helps account for variance both within and between studies. All included studies used repeated measures cross-sectional data, so there was no concern about dependency of effect sizes. We used fully random effects meta-regressions and meta-analyses with restricted maximum likelihood estimators (REML) and the Q-statistic, I2, and tau2 statistics to assess for heterogeneity. Fully random effects models were selected because we expected variation both within and between studies.

The primary purpose of this meta-regression was to assess rates of traditional and cyberbullying victimization (across gender, race, and grade) before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, we conducted random effects meta-regressions with COVID as the only independent variable for both traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying victimization using the boy and girl gender category and the race-all race category.Footnote 1 Second, we conducted the same analysis for traditional bullying victimization and cyberbullying victimization by gender, race, and grade. Third, we conducted pooled (by year) subgroup random effects meta-analyses to explore the pooled rates by individual year. This allowed us to discern rate variability from year to year. We also examined pooled effect sizes by year for gender, grade, and race. Finally, given the high amounts of heterogeneity in our sample and differences across study-level methodologies that are common in the bullying literature (Kennedy, 2021; Vaillancourt et al., 2023), we conducted a moderator analysis examining the impact of study-level features on our findings from step 1 (overall traditional bullying victimization and overall cyberbullying victimization). To do this, we conducted a series of four stepwise models for each type of victimization. The first model included COVID and sampling; model two included COVID and the time frame of the bullying question; the third model included COVID and the region where the data was collected, and the fourth model contained all four moderators. We were limited to these four study-level moderators due to a lack of variation across studies for the other extracted study-level variables (e.g., use of the word bully, if a definition was provided). Meta-regression requires a minimum of 10 effect sizes per covariate (Borenstein et al., 2009). We used Egger tests to assess for publication bias.

Results

This review included 79 studies with 19,088 effect sizes; within those effect sizes, sample sizes ranged from 26 participants to 206,941 participants, with a mean (SD) of 1957 (6810) participants (sample size ranges per study is available in the table of studies available in the Supplement).

Main Meta-regressions

We conducted random effects meta-regressions with COVID (pre-2020 vs 2020–2023) as the independent variable for traditional and cyberbullying victimization (displayed in Table 1). We found that traditional bullying victimization was significantly lower during COVID than it was before COVID (p < 0.001). Specifically, the calculated pooled reported rate of traditional bullying victimization was 23% pre-pandemic and 19% reported during the pandemic. We found no significant difference between the COVID period and the pre-COVID period for cyberbullying victimization. Next, we examined the effects of gender, grade, and race on cyberbullying victimization and traditional bullying victimization.

Cyberbullying Victimization Subgroup Analysis

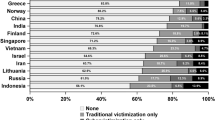

Findings for this analysis are displayed in Table 1 and graphically in bar charts in Fig. 2. While we did not find differences in rates of reported cyberbullying victimization when looking at youth overall, significant differences did emerge when we examined rates by race and gender.

For cyberbullying victimization, we found that cyberbullying victimization was slightly elevated (though statistically significant) for boys during the COVID period (12%) compared to the pre-COVID period (11%, p < .05). We also found elevated rates during COVID compared to pre-COVID for youth who identified as American Indian/Alaska Native (24% vs 21%, p < .01), Asian (15% vs 14%, p < .05), multi-racial (21% vs 19%, p < .05), and White (19% vs 18%, p < .05). In contrast, youth who identified as either transgender or non-binary reported lower rates of cyberbullying victimization during COVID than pre-COVID (25% vs 39%, p < .05).

Traditional Bullying Victimization

Findings for this analysis are displayed in Table 1, and rates are displayed graphically in Fig. 2. In contrast to cyberbullying victimization, we found that traditional bullying victimization was significantly lower during the COVID pandemic, and this was also reflected in our gender, grade, and race analyses. We found significantly lower rates of traditional bullying victimization during the COVID period compared to the pre-COVID period for girls (23% vs 26%, p < .01), boys (16% vs 20%, p < .001), and transgender/non-binary youth (41% vs 58%, p < .01). These effects were also consistent across grade, with rates dropping from 39 to 33% (p < .01) for 5th to 8th graders and from 18 to 14% (p < .001) for 9th to 12th graders in the pre-COVID compared to COVID period. Lower rates during the COVID period compared to pre-COVID were also present for five of the seven racial/ethnic groups we examined, except American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/Asian youth, where we found no significant difference. These analyses suggest that rates for traditional bullying victimization were consistently lower during pooled rates from 2020 to 2022 compared to the pooled rates from the preceding years across gender, grade, and race.

Moderator Analysis

We included a moderator analysis for four of the study-level variables: the sampling method (random vs non-random), the timeframe of the bullying question (past 30 days vs past year/12 months), the region of the data collection, and COVID (years through 2019 vs 2020–2022). For the moderator analysis (displayed in Table 2), we conducted a series of four stepwise meta-regressions for cyberbullying victimization and for traditional bullying victimization. For both types of victimization, the inclusion of the additional three moderators in the model did not change the effect of the COVID variable, even in the full model. While the inclusion of the additional three moderators did not substantially impact the COVID variable, there were some statistically significant effects on reported rates of bullying victimization.

Sampling

When studies used random sampling methods (compared to non-random), participants had 19% lower odds of reporting cyberbullying victimization (logit, − .21; 95% CI − .31, − .10; p < .001). The sampling method did not have a significant effect on the rates of traditional bullying victimization.

Time Frame

For cyberbullying victimization, the time frame was not significant when included with only the COVID variable (Model 2), but it was in the full model where both sampling and region are being held constant (Model 4). In the full model, participants in studies that had a time frame of the past 30 days had 44% lower odds (logit, − .42; 95% CI − .60, − .23) than those that had a time frame of the past 12 months. For traditional bullying victimization, the time frame had the opposite effect, where studies whose participants were given the past 30 days time frame had 3.7 times higher odds of reporting traditional bullying victimization compared to those with a past 12-month time frame (logit, 1.31; 95% CI .90, 1.72; p < .001). While time frame met the minimum number of effect sizes needed to be included in the moderator analysis, it is important to note that only three studies (out of 78) used the past 30 days time frame.

Region

For cyberbullying victimization, youth in studies that were conducted in the Midwest (logit, .21; 95% CI .12, 0.31; p < .001) and the Northeast (logit, .21; 95% CI .11, .13; p < .001) had 23% higher odds of reporting cyberbullying victimization compared to youth from studies conducted in the West. This effect remained similar in the full model. Participants in studies conducted at the national level also had higher odds of reporting cyberbullying victimization than those in the West, though this was only significant in Model 4 (and we only had two studies with nationally representative samples). For traditional bullying victimization, participants from studies conducted in the Northeast had 23% higher odds of reporting victimization compared to those in the West (logit, 0.21; 95% CI 0.05, 0.37; p < .05); this remained in the full model. Also significant in the full model was the South, with studies conducted in the South yielding 14% higher odds of reporting traditional bullying victimization compared to studies conducted in the West (logit, 0.13; 95% CI 0.00, 0.27; p < .05).

Pooled Subgroup Analysis by Year

Given variability in the previous literature based on which COVID year they used in their analysis (e.g., 2020 vs 2021) (Huang et al., 2023; Patchin & Hinduja, 2023; Shin & Choi, 2021), we conducted pooled subgroup analyses by year using random effects meta-analysis. Results from this analysis are displayed in Tables 3 and 4. Pooled subgroup analyses revealed a substantial drop in cyberbullying (9% in 2020 and down from 16% in 2019) and traditional bullying victimization in 2020 (10% down from 23% in 2019), with rates rising again in 2021 (17% for cyberbullying and 18% for traditional bullying) and 2022. That said, we only have two studies that collected data in 2020, so they need to be interpreted with extreme caution. Nonetheless, the pooled results suggest a drop in both types of bullying in 2020, with a return to more “normal” rates in 2021 and 2022. A similar pattern is evident across grade, gender, and race.

Publication Bias

The Egger test for small study effects revealed some evidence of publication bias. To account for large amounts of expected heterogeneity by time point, grade, gender, and race, we included them as moderators in the Egger tests. In addition, we included our moderators from the moderator analysis, as they also had a significant effect on reported rates. We found evidence of publication bias for traditional bullying victimization (beta1, − .30; se, .04; p < .001) and cyberbullying victimization (beta1, − .36; se, .04; p < .001). Given the nature of this meta-analysis (an expectation of variation in rates within and between studies due to year-to-year variation) and the use of logit event rates as our effect sizes, we interpreted this finding with reservations. Egger tests have been known to give inflated positive tests for studies that use log odds or odds ratios as their effect size (Lin et al., 2018). To actively reduce the risk of publication bias, we included reports, unpublished dissertations, and peer-reviewed articles when conducting our systematic search.

Discussion

This meta-analysis included 79 studies and almost 19,088 effect sizes across two types of bullying victimization and various identity characteristics. We found that overall, rates of cyberbullying victimization were similar in the pre-COVID period (16%) compared to the COVID period (17%). However, when looking at different identity characteristics, we found that cyberbullying was slightly elevated during the COVID period for boys, American Indian/Alaska Native youth, Asian youth, multi-racial youth, and White youth, while rates were lower for transgender/non-binary youth. In contrast, for traditional bullying victimization, we found that overall rates of bullying were lower during the COVID years; specifically, the pooled rate in the pre-COVID years was 23% compared to 19% in the COVID years. While this is not a dramatic difference, it was statistically significant, and any reduction in bullying victimization is important to consider and understand. Consistent with the overall findings, rates were lower in the COVID period for all identity characteristics we examined, except for two: Native American and Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Asian (which were not statistically significant). This indicates that there was a substantial shift in reported rates of traditional bullying victimization in the years 2020 to 2022 compared to the preceding years.

While our findings suggest a generally consistent pattern in the COVID years, previous research on bullying during COVID has been largely mixed (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022; Patchin & Hinduja, 2023; Shin & Choi, 2021). We attempted to address some of the factors contributing to these mixed findings by focusing on one geographic location (US), assessing the impact of several study-level variables (moderator analysis), and examining the year-to-year variation in rates of bullying, particularly during the COVID period (2020–2022) (pooled subgroup analysis), as this appeared to be a large contributor to the mixed results in the previous research.

We have three main takeaways from this study. First, while our findings suggest a drop in bullying victimization in 2020, rates rose again in 2021 and 2022, suggesting that bullying victimization remains a pressing public health issue. These findings are largely consistent with studies that have examined the impact of the pandemic on youth bullying and have included years or data points beyond 2020 (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022; Patchin & Hinduja, 2023; Schilling & Wang, 2023). While this is likely largely explained by students resuming school in late 2020/early 2021, it is important to note that research suggests that the students returning to school (and schools) are not the same as they were pre-pandemic. Studies report increases in social anxiety and depression (Garthe et al., 2023; Hawes et al., 2022) — which notably are associated with an increased vulnerability to involvement in bullying (Turner et al., 2010). At the school level, students may have experienced disruptions in formative socialization experiences, as well as friend and protective social groups, which could change how they interact and connect with peers. Furthermore, the pandemic increased disparities in academic achievement (Darmody et al., 2021), which could lead to reductions in self-esteem and self-worth, which is associated with bullying involvement (Kennedy et al., 2023). Finally, many students likely lost people in their social networks, which could lead to bereavement (Fitzgerald et al., 2021), as well as gaps in supervision. Overall, with rates of bullying resuming to somewhat normal levels during the latter years of the pandemic, given the impact of the pandemic on youth, it might be time to re-evaluate our approach to school-based bullying prevention to account for differences in students, schools, and their vulnerability to mental health struggles.

Second, we found mixed shifts in cyberbullying victimization, with overall rates largely unchanged when comparing pre-COVID to the COVID years, but with differences emerging for specific identity characteristics, which is consistent with some of the previous literature (Forsberg & Thorvaldsen, 2022; Patchin & Hinduja, 2023; Schilling & Wang, 2023; Shin & Choi, 2021). The elevated rates during COVID-19 for several racial/ethnic minority groups are worth noting, particularly given recent shifts in US culture that condone racism, hate speech, and violence, especially in online spaces (Keum & Miller, 2018). Furthermore, during COVID, there was an increase in this behavior, especially targeted toward Asian and Asian-American individuals (Costello et al., 2021; Gover et al., 2020; He et al., 2021).

The distinct trend for cyberbullying compared to traditional bullying is also important, as cyberbullying is largely considered to be an extension of traditional bullying for children and adolescents (Kowalski et al., 2023; Waasdorp & Bradshaw, 2015). If cyberbullying remains stable or even increases for some groups, while traditional bullying victimization is lower, this could suggest a split in certain types of cyberbullying or in how people interpret online interactions. One could argue there is a difference in cyberbullying relationships on different online platforms, particularly ones where individuals regularly interact with people they do not know “in real life”, such as Reddit, video games chats, Twitter, and TikTok, compared to ones where individuals regularly interact with “real life” friends, such as Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat. It is important for future research on cyberbullying to begin to differentiate how cyberbullying relationships might vary across different online spaces and how that relates to traditional bullying victimization and its overlap with cyberbullying.

Third, there was a lot of heterogeneity across and within included studies. This is an ongoing issue for bullying research, as studies are designed differently with different bullying questions and especially different time frames for self-reported bullying victimization (Kennedy, 2021; Vaillancourt et al., 2023). While our moderator analysis indicated that these factors did not impact our main findings (specifically COVID vs pre-COVID rates), they did show that these study-level factors do impact the rates collected by individual studies. Future bullying research needs to work toward developing more consistency in measures across studies. Furthermore, more qualitative research is needed to assess how youth involved in bullying are conceptualizing and interpreting bullying experiences, the definition of bullying, and the impact of bullying prevention. For example, what do they think about bullying across various social media platforms, or how do they think COVID-19 impacted bullying victimization?

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, a large percentage (91%) of the included studies are part of the YRBS System. While the different YRBS locations of this data were collected separately by different research teams, each location followed the same data collection process and used the same survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2013). Relatedly, most of the included studies are reports rather than peer-reviewed literature. While this could introduce bias, the reports used datasets frequently used in peer-reviewed literature (Davis et al., 2006; Eisenberg et al., 2020; Kreski et al., 2022; Pontes et al., 2018) and were considered high quality in our JBIC quality assessment (Munn et al., 2020). Second, we included race/ethnicity and were limited to the groups the original studies reported. We attempted to maintain the original studies’ groupings and acknowledge that these categories are self-reported groups that might differ based on various factors.

Third, we had a lot of heterogeneity in our data; we did our best to conduct subgroup and moderator analyses to try and parse out some of this heterogeneity. That said, since we examined bullying rates over time, we expected to have high amounts of heterogeneity both within studies and between studies. Fourth, given the pandemic’s disruption across multiple domains, there may have been differences in the administration and response rates of the data points collected during the pandemic period, which could have impacted the reported rates during that period. For example, the National YRBS had a slightly lower response rate in 2021 (57%) compared to the two previous data collection points (60%) (Benbenishty et al., 2018; Mpofu, 2023; Pontes et al., 2018). The stability of these rates should be explored in future research. Similarly, given how disruptive COVID was on schooling, very few studies collected data in 2020. In this review, we only had two studies (California Healthy Kids and Oregon Student Health Survey) that collected data in 2020 (compared to 77 in 2019 and 2021), which means that in the pooled analysis by year (Tables 3 and 4), the rates for 2020 need to be interpreted with caution, as two is lower than the commonly cited minimum of four for each subgroup in a subgroup meta-analysis (Fu et al., 2008). Still, other researchers argue that only two studies are needed to conduct a meta-analysis (Valentine et al., 2010). Either way, we felt it prudent to include those data points, as even though there is limited data from 2020, it is still valuable and important in assessing trends through COVID. Nonetheless, more trend research needs to be done to determine what will happen with bullying rates as youth impacted by the pandemic continue through school.

Implications and Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that when youth are not interacting with in person on a regular basis, as they do in school, rates of bullying and even cyberbullying go down. While social isolation is not a realistic or desirable way to prevent bullying and cyberbullying victimization, it does indicate that bullying victimization is not inevitable and that it is possible to reduce its occurrence. When considering the findings of this study and other research that has observed marked differences in youth following the pandemic, it is likely time for schools to re-evaluate bullying prevention plans. The students who returned to in-person school following the 2020 year of remote schooling are not the same students enrolled in school before. They have increased symptoms of depression and social anxiety and have experienced profound loss (Fitzgerald et al., 2021). This difference has been documented in other areas; students are underperforming in academics compared to pre-pandemic (Betthäuser et al., 2023). Shifts in bullying are not isolated to youth; several studies have examined bullying, specifically cyberbullying, among adults pre- and during pandemic and have found that cyberbullying is rising in that population (Barlett et al., 2021; Kee et al., 2022). This could highlight ways the pandemic has changed people and social interactions or could indicate broader cultural changes in the US and the rest of the world. In the US, there has been a rise in gun violence in schools and colleges (Matthews, 2023) and an increase in the acceptability of hate speech, racism, and violence, particularly online (Keum & Miller, 2018). Ultimately, parents, social workers, and pediatricians need to be informed about potential shifts in bullying and the risks associated with victimization, such as depression, anxiety, and self-harm (Eyuboglu et al., 2021; Kennedy et al., 2023), and how these may have been compounded by the effects of the pandemic.

Data Availability

Data and code are available upon request.

Notes

As mentioned in the methods, the boy and girl and race-all are not aggregates of the individual race and gender categories. These are distinct samples (with some overlap — thus why we did not combine them, to avoid dependency of samples).

References for studies included in the review are available in the Supplement.

References

References for studies included in the review are available in the Supplement.

Barlett, C. P., Simmers, M. M., Roth, B., & Gentile, D. (2021). Comparing cyberbullying prevalence and process before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal of Social Psychology, 161(4), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2021.1918619

Benbenishty, R., Siegel, A., & Astor, R. A. (2018). School-related experiences of adolescents in foster care: A comparison with their high-school peers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(3), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000242

Betthäuser, B. A., Bach-Mortensen, A. M., & Engzell, P. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature Human Behaviour, 7(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Wiley. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=pdQnEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&ots=WEWpASbLK_&sig=CUj5cuC8RChQ1VQxYxo_Gv_tDqo#v=onepage&q&f=false

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2022). Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 4 [Computer software]. Biostat.

Bradshaw, J., Crous, G., Rees, G., & Turner, N. (2017). Comparing children’s experiences of schools-based bullying across countries. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.060

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system—2013 (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 62). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6201.pdf

Costello, M., Cheng, L., Luo, F., Hu, H., Liao, S., Vishwamitra, N., Li, M., & Okpala, E. (2021). COVID-19: A pandemic of anti-Asian cyberhate. Journal of Hate Studies, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.33972/jhs.198

Darmody, M., Smyth, E., & Russell, H. (2021). Impacts of the COVID-19 control measures on widening educational inequalities. Young, 29(4), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/11033088211027412

Davis, A. M., Kreutzer, R., Lipsett, M., King, G., & Shaikh, N. (2006). Asthma prevalence in Hispanic and Asian American ethnic subgroups: Results from the California Healthy Kids Survey. Pediatrics, 118(2), e363–e370. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2687

Eisenberg, M. E., Erickson, D. J., Gower, A. L., Kne, L., Watson, R. J., Corliss, H. L., & Saewyc, E. M. (2020). Supportive community resources are associated with lower risk of substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning adolescents in Minnesota. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(4), 836–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01100-4

Evans, C. B. R., Fraser, M. W., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(5), 532–544. psyh. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004

Eyuboglu, M., Eyuboglu, D., Pala, S. C., Oktar, D., Demirtas, Z., Arslantas, D., & Unsal, A. (2021). Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying: Prevalence, the effect on mental health problems and self-harm behavior. Psychiatry Research, 297, 113730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113730

Fitzgerald, D. A., Nunn, K., & Isaacs, D. (2021). What we have learnt about trauma, loss and grief for children in response to COVID-19. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 39, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2021.05.009

Forsberg, J. T., & Thorvaldsen, S. (2022). The severe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on bullying victimization, mental health indicators and quality of life. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27274-9

Fu, R., Gartlehner, G., Grant, M., Shamliyan, T., Sedrakyan, A., Wilt, T. J., Griffith, L., Oremus, M., Raina, P., Ismaila, A., Santaguida, P., Lau, J., & Trikalinos, T. A. (2008). Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the effective health care program. In Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK49407/

Garthe, R. C., Kim, S., Welsh, M., Wegmann, K., & Klingenberg, J. (2023). Cyber-victimization and mental health concerns among middle school students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(4), 840–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01737-2

Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youths: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements (1; p. 116). Centers for Disease Control.

Gover, A. R., Harper, S. B., & Langton, L. (2020). Anti-Asian hate crime during the COVID-19 pandemic: Exploring the reproduction of inequality. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(4), 647–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09545-1

Hawes, M. T., Szenczy, A. K., Klein, D. N., Hajcak, G., & Nelson, B. D. (2022). Increases in depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Medicine, 52(14), 3222–3230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720005358

He, B., Ziems, C., Soni, S., Ramakrishnan, N., Yang, D., & Kumar, S. (2021). Racism is a virus: Anti-asian hate and counterspeech in social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining, 90–94. https://doi.org/10.1145/3487351.3488324

Huang, N., Zhang, S., Mu, Y., Yu, Y., Riem, M. M. E., & Guo, J. (2023). Does the COVID-19 pandemic increase or decrease the global cyberbullying behaviors? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15248380231171185. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231171185

Kahn, G. (2020, October 1). Screen time is up—and so is cyberbullying. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/science-and-technology/2020/10/screen-time-use-is-up-and-so-is-cyberbullying

Kee, D. M. H., Al-Anesi, M. A. L., & Al-Anesi, S. A. L. (2022). Cyberbullying on social media under the influence of COVID-19. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 41(6), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22175

Kennedy, R. S. (2020a). A meta-analysis of the outcomes of bullying prevention programs on subtypes of traditional bullying victimization: Verbal, relational, and physical. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 55, 101485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101485

Kennedy, R. S. (2020b). Gender differences in outcomes of bullying prevention programs: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105506

Kennedy, R. S. (2021). Bullying trends in the United States: A meta-regression. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 914–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019888555

Kennedy, R. S., Panlilio, C. C., Mullins, C. A., Alvarado, C., Font, S. A., Haag, A.-C., & Noll, J. G. (2023). Does multidimensional self-concept mediate the relationship of childhood sexual abuse and bullying victimization on deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation among adolescent girls? Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00947-8

Keum, B. T., & Miller, M. J. (2018). Racism on the internet: Conceptualization and recommendations for research. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 782–791. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000201

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., & Feinn, R. S. (2023). Is cyberbullying an extension of traditional bullying or a unique phenomenon? A longitudinal investigation among college students. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 5(3), 227–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00154-6

Kreski, N. T., Chen, Q., Olfson, M., Cerdá, M., Martins, S. S., Mauro, P. M., Hasin, D. S., & Keyes, K. M. (2022). National trends and disparities in bullying and suicidal behavior across demographic subgroups of US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2022.04.011

Lebrun-Harris, L., Sherman, L., Limber, S., Miller, B., & Edgerton, E. (2019). Bullying victimization and perpetration among U.S. children and adolescents: 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1170-9

Lebrun-Harris, L. A., Sherman, L. J., & Miller, B. (2020). State-level prevalence of bullying victimization among children and adolescents, National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016–2017. Public Health Reports, 135(3), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920912713

Lin, L., Chu, H., Murad, M. H., Hong, C., Qu, Z., Cole, S. R., & Chen, Y. (2018). Empirical comparison of publication bias tests in meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(8), 1260–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4425-7

Matthews, A. (2023, September 22). School shootings in the US: Fast facts. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/22/us/school-shootings-fast-facts-dg/index.html

Minnesota Department of Education. (2022). Minnesota student survey reports 2013–2022. https://public.education.mn.gov/MDEAnalytics/DataTopic.jsp?TOPICID=242

Mpofu, J. J. (2023). Overview and methods for the youth risk behavior surveillance system—United States, 2021. MMWR Supplements, 72. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7201a1

Munn, Z., Moola, Lisy, K., Riitano, D., & Tufanaru, C. (2020). Systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI.

Patchin, J. W., & Hinduja, S. (2023). Cyberbullying among Asian American youth before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of School Health, 93(1), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.13249

Pontes, N. M. H., Ayres, C. G., Lewandowski, C., & Pontes, M. C. F. (2018). Trends in bullying victimization by gender among U.S. high school students. Research in Nursing & Health, 41(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.21868

Repo, J., Herkama, S., & Salmivalli, C. (2022). Bullying interrupted: Victimized students in remote schooling during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Bullying Prevention. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-022-00146-6

Schilling, R. A., & Wang, W. (2023). Cyberbullying victimization and the COVID-19 pandemic: A routine activity perspective. Journal of School Violence, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2023.2248869

Shin, S. Y., & Choi, Y.-J. (2021). Comparison of cyberbullying before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10085. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910085

StataCorp. (2023). Stata Statistical Software: Release 18 [Computer software]. StataCorp LLC.

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., & Ormrod, R. (2010). Child mental health problems as risk factors for victimization. Child Maltreatment, 15(2), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509349450

US Census Bureau. (2023). Census regions and divisions of the United States. https://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf

Vaillancourt, T., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Farrell, A. H., Landon, S., & Pepler, D. (2021). School bullying before and during COVID-19: Results from a population-based randomized design. Aggressive Behavior, 47(5), 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21986

Vaillancourt, T., Farrell, A. H., Brittain, H., Krygsman, A., Vitoroulis, I., & Pepler, D. (2023). Bullying before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Opinion in Psychology, 53, 101689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101689

Valentine, J. C., Pigott, T. D., & Rothstein, H. R. (2010). How many studies do you need?: A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 35(2), 215–247. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998609346961

Waasdorp, T. E., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(5), 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.12.002

Wang, Q., Luo, X., Tu, R., Xiao, T., & Hu, W. (2022). COVID-19 information overload and cyber aggression during the pandemic lockdown: The mediating role of depression/anxiety and the moderating role of Confucian responsibility thinking. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031540

Xu, M., Macrynikola, N., Waseem, M., & Miranda, R. (2020). Racial and ethnic differences in bullying: Review and implications for intervention. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 50, 101340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.101340

Zviedrite, N., Hodis, J. D., Jahan, F., Gao, H., & Uzicanin, A. (2021). COVID-19-associated school closures and related efforts to sustain education and subsidized meal programs, United States, February 18–June 30, 2020. PLoS ONE, 16(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248925

Acknowledgements

We thank Alyson Lawrence for her contribution to article selection and data extraction. We also want to thank Dr. Anne Broussard and Dr. David Finkelhor for reading the manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Carolinas Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RSK was responsible for study conception and design, article selection, article review, data extraction, data analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation (writing and revision). KD contributed to article selection and review, data extraction, and manuscript preparation (revision).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This is an observational study of previously published literature, so no ethical approval was needed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kennedy, R.S., Dendy, K. Traditional Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Analysis. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00255-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00255-4