Abstract

The aim of the current study was to examine risk and protective factors related to bullying in sport. Adopting the methodological approach outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1):19–32, 2005), 37 articles met the inclusion criteria. A consistent definition of bullying could not be identified in the publications examined, and several articles (n = 8) did not explicitly define bullying. The most frequent risk factor identified was an individual’s social background (n = 9). Negative influence of coaches (n = 5), level of competition (n = 5), lack of supportive club culture (n = 5) and issues in locker rooms (n = 4) were among the most commonly cited risk factors for bullying in sport settings. Preventative policies were cited as the most common method to reduce the incidence of bullying (n = 13). Contextually tailored intervention programmes (n = 5) were also noted as a key protective factor, particularly for marginalised groups, including athletes with disabilities or members of the LGBTQ+ community. The need for sport-specific bullying prevention education was highlighted by 10 of the articles reviewed. In summary, the current review accentuates the range of risk and protective factors associated with sport participation. Furthermore, the need for educational training programmes to support coaches in addressing and preventing bullying within sport settings is emphasised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Bullying is a complex and multi-layered issue that crosses from childhood to adulthood and is a continuing challenge in education, workplace and recreation settings (Fisher & Dzikus, 2017). Although there remains considerable debate regarding the definition of the concept, Olweus’ (1993) definition has retained some support (Jewett et al., 2020). Olweus (1993, p. 8) defines bullying as an ‘intentional, negative action which inflicts injury and discomfort on another’. According to Olweus (1993), bullying is characterised by an imbalance of power between victim and perpetrator as well as by repeated bullying behaviours. The phenomenon of bullying in education and workplace settings has received extensive scholarly attention (Campbell & Bauman, 2018; Jimerson et al., 2009; Zapf et al., 2020). However, research on bullying outside school and workplace settings is relatively scarce (Evans et al., 2016). One such context is sport settings, and researchers have suggested bullying in such contexts may present its own unique features (Kerr et al., 2016). Kerr et al. (2016) suggest that bullying can occur due to teasing behaviours carried out for ‘entertainment purposes’, which may not carry a clear intent to harm, such as ‘banter’ or ‘locker room talk’. Recent high-profile cases of bullying in elite sport (see CNN, 2022, 2023) have demonstrated that, even at an elite level, sporting organisations are not prepared to cope with issues such as marginalisation and exclusion that may be considered both precursors and sources of bullying. Indeed, bullying on sports teams may have particular implications for participants, given the importance of interconnectedness and interdependence of team members for a sense of cohesion and performance outcomes (Kleinert et al., 2012). Bullying research and the widespread adoption of practical approaches are scarce (Newman et al., 2022). Fekkes et al. (2005) reported that almost one-third of bullying experiences occur beyond school and workplace settings, indicating a need to broaden the scope of research and consider bullying in recreation and sport contexts.

Sports, particularly team sports, often involve competition and aggressive interaction and some research has highlighted higher levels of bullying within the team sport context (MacPherson, 2018; Marracho et al., 2021; Vveinhardt & Fominiene, 2020). At times, in the heat of competition, it can be challenging for participants to distinguish between deliberately hurtful actions and those inherent to the competitive nature of the game (Nery et al., 2019). As a consequence, bullying in terms of hurtful behaviours, both physical and verbal, can end up becoming an accepted and expected norm that is intrinsic to particular sports, and such behaviour is often informed by coaches (Vveinhardt et al., 2019). Furthermore, the source of bullying behaviour is not always restricted to participants in an opposing team. Emerging evidence indicates that the source is often from participants on the same team or even a coach (Evans et al., 2016). As such, coaches in particular play a crucial role in reducing or addressing bullying. Sport coaches are not only expected to support sport development, but also to provide a fun, positive and safe team environment while also actively fostering personal (life skill) development (Čujko et al., 2020; Gilbert & Trudel, 2004). Nonetheless, despite the growing awareness of bullying in sport and recreation settings, there remains limited programmes for coaches aimed at heightening sensitivity about bullying, preventing and identifying bullying situations and intervening effectively (Shannon, 2013; Stefaniuk & Bridel, 2018).

The prevalence of bullying appears to differ significantly across countries (Modecki et al., 2014), and estimates regarding its prevalence vary greatly depending on the context and the measurement tool used to gather the data (Evans et al., 2016). For instance, data from the USA indicate that about one out of every four school children has experienced bullying (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). In a European context, Craig et al. (2009) reported differences in prevalence ranged from lows of 8.6% and 4.8% in Sweden to highs of 45.2% and 35.8% in Lithuania, among boys and girls, respectively. However, the assessment of this phenomenon among participants in different contexts and countries, using measurement tools that lack validity and reliability, emphasises the need for caution when making such comparisons (Vveinhardt et al., 2019). As noted by Bachand (2017), many researchers have used one-item measures of bullying, which may be insufficient given the intricacy of bullying-related behaviours. Despite concerns regarding the accuracy of tools to measure prevalence, it is abundantly clear that bullying is commonplace in sporting contexts, with a range of adverse health and psychosocial consequences going far beyond the context within which the sport occurs (Shannon, 2013). Via a sample of 1440 Lithuanian sport participants between 16 and 29 years old, the prevalence of bullying within different types of sports was measured by Vveinhardt and Fominiene (2020) in individual sports (9.8%), combat sports (8.5%) and team sports (7.3%). In their analysis, athletes experienced most bullying actions in combat sports (20%) while almost half less in team sports (10.8%) as well as in individual sports (10.1%). Notwithstanding challenges with measurement and contextual factors, the disparity in rates between countries indicates that contrasting cultural and social norms, and varying approaches in the implementation of bullying-related policies or programmes, may significantly influence the prevalence of bullying behaviour (Fisher & Dzikus, 2017). For instance, higher conformity to hegemonic masculinity norms may enhance the perceived acceptability of bullying (Steinfeldt et al., 2012).

Little attention has been given to the social, environmental and situational factors in sport contexts that may influence bullying behaviour (Vveinhardt et al., 2019). Therefore, risk factors or protective factors associated with both the perpetrator and victim are not well established. Some authors, such as Shannon (2013), reported that the culture of a sport organisation, as exemplified through the values, attitudes, beliefs and practices of administrators and staff, might serve as an important buffer to bullying. Other studies likewise highlight the potential role of contextual factors or individual relationships (e.g. Evans et al., 2016; Newman et al., 2022). Beyond these first attempts, however, there still remains a need to more systematically identify risk and protective factors, which in turn can directly help tailor and inform the development of awareness or education programmes targeted at sport coaches.

As such, the following scoping review aimed to examine how bullying is defined and measured in sport-related literature and to establish commonalities in both risk and protective factors associated with bullying. This could serve to inform sporting organisations to foster more inclusive environments and limit the negative consequences of bullying. In addition, a specific focus of this review was to examine the role coaches play in preventing or facilitating bullying.

Methods

The following scoping review took place against the backdrop of the BEFORE project. A four-partner, pan-European action, this project aims to review current policies and practices to develop educational training programmes to support coaches in addressing and preventing bullying within sport settings, funded by Erasmus+ (2021-1-IE01-KA220-VET-000034749). To effectively grasp current understandings and experiences around bullying in sport, and develop evidence-based educational programmes, a scoping review was undertaken to map out crucial information related to the subject. Indeed, scoping reviews can be valuable in identifying evidence around a given topic, documenting trends and clarifying concepts (Munn et al., 2018).

For the following, we adopt the methodological approach outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), which is a widely accepted approach for scoping reviews and has been adopted by numerous reviews in the areas of bullying and sport-related social issues more generally (e.g. Clarke et al., 2021; Quinlan et al., 2014). Our scoping review began in March 2022 and took approximately 11 months. The review followed six steps, namely, (1) identifying the research questions; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. A sixth step, consultation with relevant stakeholders, was also implemented to add rigour and validate findings. In the following sub-sections, we document each of these steps individually.

Identification of the Research Questions

In line with the educational objectives of the BEFORE project, the authors and project members developed a set of research questions to guide our search strategy. Following recommendations, we ensured that our questions were not so narrow as to limit the analytical process and broad enough to capture all relevant literature. As such, in accordance with the aims of our project, we developed three research questions to direct our review: (1) how is bullying defined in sport-related literature; (2) what risk or protective factors are identified concerning bullying and (3) what role do coaches play in preventing or facilitating bullying?

Determination of Relevant Studies

A search strategy was developed and reviewed by the authors and all project members, including during the project launch meeting in March 2022. As a result, we selected several multi-disciplinary and thematically relevant databases to conduct our search and agreed on relevant search terms and related inclusion criteria.

A final search string was chosen (TS = (“sport*” AND “bully*”)) to balance the extent and relevance of results as well as overall feasibility. Given the more niche nature of the topic, we opted for a simple combination of two broad search terms to obtain a wide range of potentially relevant results. Furthermore, as part of our research question concerned specifically the definition of bullying, we opted to exclude potentially connected terminology such as peer victimisation or harassment. As such, only the two mentioned terms have been included to ensure a feasible number of articles were retrieved from our search for review. Numerous databases, including the Web of Science Core Collection, KCI-Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE®, Russian Science Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, SportDISCUS, Sociology Source Ultimate and PsyIndex, were used. Via in-built online filters, searches were limited to peer-reviewed journal publications published in English between 2000 and 2022. All searches were conducted on April 12, 2022. Tables 1 and 2 present the search strategy and inclusion criteria, respectively.

Study Selection

Covidence software was used to manage and streamline the process of abstract and full-text screening. Covidence allows researchers to upload search results, automatically scans for duplicates and coordinates multi-user screening of articles, thus facilitating our work as a multi-national, decentralised research team. Two project members reviewed each abstract and subsequent full text independently. A unanimous decision was required for texts to progress to full-text screening and, later, to full-text inclusion. In situations of conflicting decisions, the authorship group met to discuss and resolve those conflicts. Two key factors drove full-text inclusion.

Firstly, texts were required to make explicit reference to the term bullying. Related concepts, such as violence, maltreatment or abuse, were excluded. Though admittedly connected, including these concepts would have inflated the review and included behaviours and perspectives that, arguably, go beyond what is typically associated with bullying. Secondly, only texts concerning the prevalence, experience or prevention of bullying in the club, community or extracurricular sport context were included. Though we recognise that bullying and sport frequently occur within educational contexts, most coaches targeted by the BEFORE project work within community or club contexts. Those contexts likely face different dynamics than formal educational settings (Kerr et al., 2016), and it was necessary for the project that those contexts be adequately and fully reflected in our results.

Charting the Data

The next stage of the process involved charting and data extraction from the included studies. Each project partner was responsible for charting a segment of the included studies, and the authorship group reviewed the final data table. We used Google Sheets and charted bibliographic, methodological and bullying-specific information for the included studies. Regarding bibliographic and methodological information, we collated titles, author(s), year, journal name, country of study, study design, sample descriptions, data collection methods and theories employed. As it relates to bullying, we documented the definition employed within the article, the setting in which the bullying took place, the bullying relationship (i.e. athlete-athlete, coach-athlete) and the risk and protective factors documented in the study.

Collating and Reporting Results

Both frequency analysis and deductive coding were used to collate and report the results. The variables extracted for the frequency analysis included publication year, data origin (country), journal, methodology, study population and sport. Deductive coding allowed us to identify and summarise the relationships and protective and risk factors highlighted by the texts. Based on the coding results, we then conducted a frequency analysis to document the occurrence of these relationships and factors.

Consultation

Though consultation is presented here as the final step, consultation took place throughout this research. The entire project consortium, which includes an anti-bullying NGO, a pan-European organisation and two universities, was engaged in the review’s design, implementation and analysis. Multiple members from each project partner contributed to designing, reviewing and implementing the proposed search strategy and inclusion criteria. Following the collation and writing of the results, these partners reviewed the extracted data and critically appraised the overall analysis in this text.

Findings

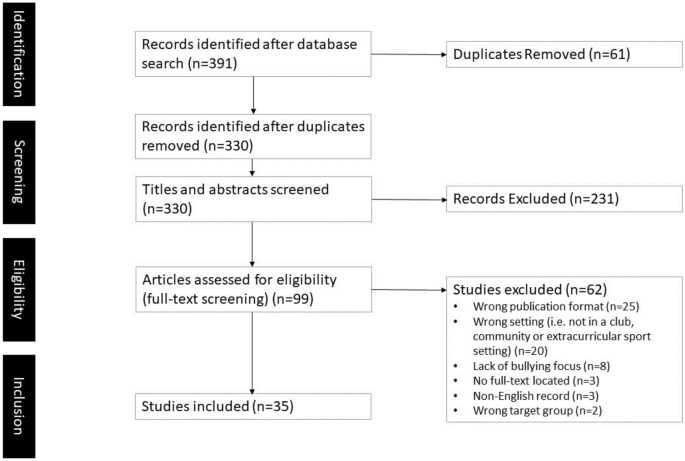

In total, 391 studies were identified, 61 duplicates were removed, and 330 studies were screened. After screening, 231 studies were excluded, with 99 studies being assessed for eligibility. Of these 99, 62 studies were excluded for the reasons noted in Fig. 1, including wrong publication format (n = 25), wrong setting (n = 20) and lack of bullying focus (n = 8). After our inclusion criteria were applied, 37 articles examining bullying in sport met all criteria for inclusion in this study. An overview of the retained articles is provided in Table 3.

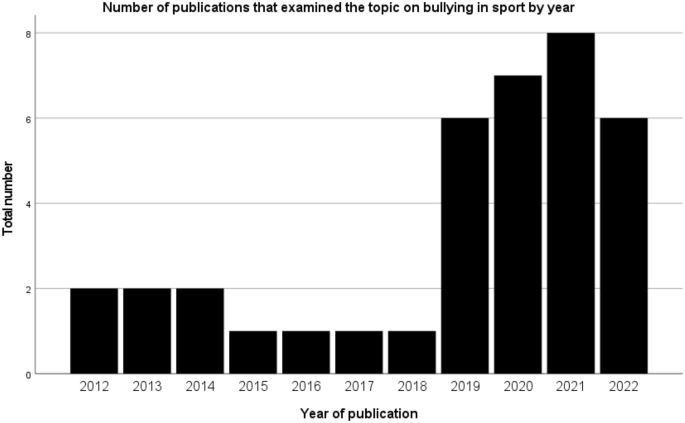

Publication Year

Though our search parameters extended back to 2000, no texts were included before 2012. As evidenced in Fig. 2, articles on bullying in sports have increased since 2019, with 26 out of 37 publications published from 2019 to 2022.

Journals

In total, 31 different journals were included in the scoping review. Three publications were included in the journals Frontiers in Psychology, and a further two publications each were included in the journals Motricidade, International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology and Journal of Human Sport & Exercise as well as the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Research Locations

Research data comes mostly (n = 35) from countries in the so-called West or ‘Global North’, characterised as Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand. The other two studies come from Iran and Japan. Lithuania appears more frequently than the other Western countries (n = 8), followed by the USA (n = 6), Canada, Portugal, Spain and the UK (n = 4).

In terms of the different sports analysed, most studies focused on multiple sports (n = 21), including team sports (football/soccer, basketball, rugby) as well as individual sports (swimming, acrobatics, gymnastics or badminton). A total of 11 articles analysed one particular sport, with football/soccer being the most frequent (n = 6).

Definition of Bullying in Sport

A consistent definition of bullying could not be identified in the publications examined. Several journal articles (n = 8) did not explicitly define bullying. Most articles used definitions of bullying which included the terms ‘repeated/repeatedly’ (n = 11) or ‘intentional’ (n = 8). Three main parameters of bullying were identified by Vveinhardt et al. (2019) as bullying is repeated over time, involves an imbalance of power and may be verbal, physical, social or psychological. Concerning the different types of bullying, three journal articles differentiated between physical, verbal, social or cyberbullying. Different relationships between the perpetrator and the victim were identified in terms of bullying in sport. The selected journal articles differentiated between peer-to-peer bullying of athletes (n = 17), as well as coach-athlete (n = 9) or coach-coach bullying relationships (n = 1), with athlete-to-athlete bullying being the most common type of bullying relationship reported. Most papers analysed more than one specific relationship of bullying in their analysis, including athlete-athlete as well as the relationship between athletes and coaches (n = 12). A total of eight articles did not define the bullying relationship at all.

Risk Factors

Multiple risk factors of bullying can be identified in the articles. In general, sports participation increased the likelihood of being bullied for those on the margins. Five out of 37 papers underlined that participation in sports, team sports, interscholastic sports and contact sports increases the risk of being bullied. The most frequent risk factor identified was individual social backgrounds and how others interact with diverse individuals (n = 9). Thus, different identities related to gender, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity or health may lead to more bullying. For example, Ohlert et al. (2020) reported that gender differences were only evident for sexual violence, with female athletes showing higher prevalence estimates than male athletes, while Vveinhardt and Fominiene (2019) reported that male athletes are more aggressive physically, verbally or nonverbally than women.

A total of five articles identified the lack of a supportive culture as another risk factor of bullying, meaning that a lack of support for the individual athlete or/and a culture creating fear, discrimination, silence or conformity within the sport setting increases the risk of bullying (Baiocco et al., 2018; Jewett et al., 2020; Shannon, 2013).

Lack of supervision was identified as another risk factor in four studies. These sorts of risks relate to places or moments within the sporting context where a lack of supervision or structure is seen as creating opportunities for bullying (e.g. unstructured time, changing rooms). Locker rooms were identified by several studies (n = 4) as the most conflict-prone place. Due to the intimate atmosphere and the absence of adult surveillance, locker rooms can foster a climate of fear and competition (Nikolaou & Crispin, 2022).

In the sport and bullying context, five papers found that the negative influence of coaches present a risk of bullying, as coaches have a high influence on the individual athlete as well as the negative, sometimes even toxic, atmosphere in the sport setting (e.g. Driessens, 2015; Rios et al., 2022; Vveinhardt et al., 2017; Vveinhardt & Fominiene, 2019; Weuve et al., 2014). However, some authors argued that the role of team managers and coaches is not yet fully understood as it relates to bullying prevention (Newman et al., 2022; Vveinhardt et al., 2019). In addition to coaches, external influences such as parents or family members were described as another risk. As Yabe et al. (2021, p. 191) state, ‘it is necessary that parents are aware of their roles in youth sport to make appropriate mutual communication between parents and coaches, which could lead to a more comfortable atmosphere for young athletes’. Table 4 provides a frequency count overview of the most commonly reported risk factors identified during the review.

Protective Factors

Overall, 27 out of 37 articles reported on protective factors in their studies. Protective measures or policies within the sport or club setting are the most common factor in preventing bullying (n = 13). Studies with contextually tailored intervention programmes reduced the likelihood of experiencing bullying victimisation and created more positive sport experiences for all participants (Driessens, 2015; Haegele et al., 2020; Newman et al., 2022; Storr et al., 2022). The papers showed that especially marginalised groups, e.g. athletes with disabilities (Haegele et al., 2020) or members of the LGBT+ community (Baiocco et al., 2018), benefit from these types of programmes.

Besides programmes targeting the athletes, the need for educational programmes (e.g. coach development workshops and educational programmes for teachers and parents) has been identified by multiple papers (n = 10). The education of coaches, parents and stakeholders is one key factor in addressing and preventing bullying (Mattey et al., 2014; Newman et al., 2022). According to Mattey et al. (2014), educational workshops can increase awareness of the effects of bullying and help athletes, coaches and other stakeholders to create safe, bullying-free environments. Furthermore, some papers (n = 5) underlined that access to extracurricular or sports activities helps develop participants’ confidence and skills and, subsequently, reduces the risk of disruptive behaviour (Haegele et al., 2020; Storr et al., 2022).

In addition, building up internal skills or characteristics of individuals such as resilience or emotional competence have been identified to foster anti-bullying behaviour (Baiocco et al., 2018; Storr et al., 2022; Weuve et al., 2014). Table 5 provides a frequency count overview of the most prominent protective factors identified during the review.

Discussion, Limitations and Implications

Through a scoping review of 37 articles, we have aimed to expose the current status of research regarding bullying in sport. In particular, we have sought to highlight the understanding of bullying within the existing research, as well as document the relationships, risks and protective factors related to bullying in sport. Before discussing the implications of our findings, it is worth pausing on some of the limitations associated with our work. Firstly, though not a limitation per se, it is crucial to remember that our review focuses exclusively on sport in the club, community, recreational and extracurricular settings. We do not focus on bullying in the context of formal physical education, though we suspect this is a further area of worthwhile inquiry. Secondly, our review focused only on peer-reviewed, English-language journal articles. These restrictions limit the potential results, and a multi-lingual and multi-format review may have yielded different outcomes. Having said that, we can nonetheless establish a few clear trends and potential future directions based on the results presented here.

Conceptually, the body of literature presented here does not use one specific definition of bullying, with numerous studies even taking the term somewhat for granted and failing to provide any form of working definition. This ambiguity around a standard definition is perhaps unsurprising given the ‘ongoing definitional issues of the word bullying’ (Hellström et al., 2021, p. 4). When the term is defined, however, there is a fairly clear trend towards understanding bullying as something both repeated and intentional, and that can take the form of verbal, physical or emotionally abusive behaviour. Seismic developments in information and communication technology have resulted in the forms and platforms of bullying inevitably changing (Hellström et al., 2021). Indeed, while discrimination has always been a problem in sport, the growth of social media has exacerbated the issue (Kearns et al., 2023) and is an area in need of further research based on the studies examined in the current review.

Likewise, there is great variety in the risk and protective factors associated with bullying in the retained papers. Most strikingly, the characteristics of the sporting context seem to play a determining role as it relates to the risk of bullying. For one, the type of sport is relevant. Team sports seem to have a higher prevalence of bullying than combat or individual sports. According to the study by Marracho et al. (2021), the prevalence of bullying (victims, bullies and bystanders) was 26.7% in team sports, 19.1% in individual sports and 23.1% in combat sports, with no significant differences between different sports concerning the prevalence of bullying behaviours. Other studies included here echo these findings, though further meta-analysis would be needed to establish deeper insights concerning prevalence statistics (Marracho et al., 2021; Vveinhardt & Fominiene, 2020). Relatedly, higher levels of competition, especially at elite sport levels, can be identified as another sport-specific risk factor. The unique power of competition as a distinct risk factor in sport settings was highlighted here in only two studies (Marracho et al., 2021; Shannon, 2013), though literature concerning abuse or harassment in sport also confirms this as a risk factor (e.g. Bjørnseth & Szabó, 2018). The pressure to win, as well as the competitive environment in team or individual sport settings, increases the likelihood of bullying behaviours.

Regardless of the type of sport or competition level, it is also clear that the environment plays a crucial role in the prevalence of bullying. Bullying thrives in situations of power imbalances, and these imbalances are often made worse through environments that reinforce various forms of discrimination. Gender, disability and ethnicity have all been identified as risk factors, though we use this term carefully as we do not mean to imply that these differences are the causes of bullying. Rather, the real risk comes from attitudes and environments that enable and condone discriminatory behaviours and bullying. For instance, some authors identify toxic masculinity in team sports such as football/soccer or volleyball as a risk factor (Mattey et al., 2014). Conversely, some articles highlight that participating in sport can increase personal confidence, especially for people with disabilities, while increasing access to sports may be a lower-cost alternative to many bullying intervention programmes, with the added benefit of increases in health and wellness, human capital and peer network effects already associated with sports participation and physical activity (Nikolaou & Crispin, 2022).

This shows that the sporting context and environment do not emerge independently but are primarily shaped by the individuals organising and delivering sporting activities. This is reflected in the fact that the role of coaches is listed as both a protective and risk factor. For instance, Baiocco et al. (2018) underline that the role of coaches can have a positive influence on preventing bullying. Coaches may provide a positive and supportive environment, partially protecting athletes from the psychological effects of unsupportive, bullying environments.

Given the crucial role of coaches in creating a supportive environment and reducing the risk of bullying, it is essential to consider the kind of resources and education coaches need to fulfil this vital role. Sport psychologists Smith and Smoll (2012) created guidelines to support coaches, including clear examples and real stories to promote leadership behaviour and life skills development as well as coach-parent relationships, aiming to prevent bullying behaviours. In their recent study, Ríos and Ventura (2022) highlight that prevention strategies related to promoting a positive climate among athletes are the most important factor to tackle bullying. As coaches themselves had little knowledge on bullying in general, more specific training is relevant. As toxic and discriminatory attitudes often reinforce bullying behaviours, coaches must be equipped with the tools to understand and tackle discrimination at its roots. To that end, this implies systemically integrating anti-bullying education within coach development curricula, as well as ensuring that coaches obtain adequate training and support to implement safe sport guidelines and principles (see Moustakas et al., 2023). Any such education should also be responsive to the experiences and realities of coaches as it relates to bullying, as the role of coaches in this area is not yet fully understood (Newman et al., 2022; Vveinhardt et al., 2017). In particular, understanding how coaches may experience, witness and deal with bullying are valuable areas for future exploration. Elsewhere, it is also crucial for any anti-bullying curriculum to consider and develop synergies with educational approaches in other related areas. The goal here is not to overload coaches with new, burdensome training requirements but to help them promote a safe, fun, inclusive sporting environment. As such, anti-bullying education should closely align with and complement educational materials related to areas such as intercultural education (e.g. Moustakas et al., 2022) or anti-discrimination (e.g. Kavoura et al., 2016).

Overall, this is the key message from our findings. Coaches are central to mediating many of the risks present within the sporting context, including establishing an inclusive atmosphere, supervising risk-prone areas and dealing with bullying cases as they arrive. Yet it is also clear that sport coaches do not receive nearly enough training and support to fulfil this crucial role, and future work must urgently address this need by developing relevant curricula and enacting the necessary support structures.

References

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Bachand, C. R. (2017). Bullying in sports: The definition depends on who you ask. The Sport Journal, 9, 1–14.

Baiocco, R., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Lucidi, F., & Ioverno, S. (2018). Sports as a risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a sample of gay and heterosexual men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 22(4), 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2018.1489325

Bjørnseth, I., & Szabó, A. (2018). Sexual violence against children in sports and exercise: A systematic literature review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(4), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2018.1477222

Campbell, M., & Bauman, S. (2018). Reducing cyberbullying in schools: International evidence-based best practices: Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

Clarke, F., Jones, A., & Smith, L. (2021). Building peace through sports projects: A scoping review. Sustainability, 13(4), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042129

CNN. (2022). Victim of adolescent bullying by Boston Bruins signee denies he gave player his support. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2022/11/10/sport/boston-bruins-bullying-scandal-spt-intl/index.html

CNN. (2023). Northwestern fires head baseball coach amid allegations of ‘bullying and abusive behavior,’ per report. Retrieved from https://edition.cnn.com/2023/07/14/sport/jim-foster-fired-northwestern-baseball-spt-intl/index.html

Craig, W. M., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S. M., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B. G., Molcho, M., De Mato, M. G., Overpeck, M. D., Due, P., & Pickett, W. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54(S2), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-009-5413-9

Čujko, A., Jeričević, M., Lara-Bercial, S. (2020). Guidelines regarding the minimum requirements in skills and competences for coaches. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/69405

Driessens, C. M. (2015). Extracurricular activity participation moderates impact of family and school factors on adolescents’ disruptive behavioural problems. BMC Public Health, 15, 1110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2464-0

Evans, B., Adler, A., MacDonald, D., & Côté, J. (2016). Bullying victimisation and perpetration among adolescent sport teammates. Pediatric Exercise Science, 28(2), 296–303.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2005). Bullying: Who does what, when and where? Involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Education Research, 20(1), 81–91.

Fisher, L. A., & Dzikus, L. (2017). Bullying in sport and performance psychology. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.169

Gilbert, W. D., & Trudel, P. (2004). Role of the coach: How model youth team sport coaches frame their roles. The Sport Psychologist, 18(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.18.1.21

Haegele, J. A., Aigner, C., & Healy, S. (2020). Extracurricular activities and bullying among children and adolescents with disabilities. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02866-6

Haegele, J. A., Wilson, P. B., Zhu, X., & Kirk, T. N. (2019). The meaning of youth physical activity experiences among individuals with psoriasis: A retrospective inquiry. European Physical Education Review, 25(2), 374–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X17740143

Hellström, L., Thornberg, R., & Espelage, D. L. (2021). Definitions of bullying. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Bullying: A Comprehensive and International Review of Research and Intervention, 1, 2–21.

Jewett, R., Kerr, G., MacPherson, E., & Stirling, A. (2020). Experiences of bullying victimisation in female interuniversity athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(6), 818–832.

Jimerson, S. R., Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (2009). Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective. New York: Routledge.

Kavoura, A., Kokkonen, M., & Siljamäki, M. (2016). Tackling discrimination in grassroots sport: A handbook for teachers and coaches. Acahia: Regional Center of Vocational Training and Lifelong Learning.

Kearns, C., Sinclair, G., Black, J., Doidge, M., Fletcher, T., Kilvington, D., Liston, K., Lynn, T., & Rosati, P. (2023). A scoping review of research on online hate and sport. Communication & Sport, 11(2), 402–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221132728

Kerr, G., Jewett, R., MacPherson, E., & Stirling, A. (2016). Student–athletes’ experiences of bullying on intercollegiate teams. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 10(2), 132–149.

Kleinert, J., Ohlert, J., Carron, B., Eys, M., Feltz, D., Harwood, C., . . . & Sulprizio, M. (2012). Group dynamics in sports: An overview and recommendations on diagnostic and intervention. The Sport Psychologist, 26(3), 412–434.

MacPherson, E. (2018). Peer-to-peer bullying in sport. Journal of Exercise, Movement, and Sport (SCAPPS refereed abstracts repository), 50(1), 145–145.

Marracho, P., Pereira, A. M. A., Nery, M. V. G., Rosado, A. F. B., & Coelho, E. M. R. T. C. (2021). Is young athletes’ bullying behaviour different in team, combat or individual sports? Motricidade, 17, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.6063/motricidade.21129

Mattey, E., McCloughan, L., & Hanrahan, S. (2014). Anti-vilification programs in adolescent sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 5(3), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2014.925528

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., & Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 602–611.

Moustakas, L., Papageorgiou, E., & Petry, K. (2022). Developing intercultural sport educators in Europe. In K. Petry & J. de Jong (Eds.), Education in sport and physical activity (pp. 206–215). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003002666-22

Moustakas, L., Kalina, L., & Petry, K. (2023). The development and validation of a child safeguarding in sport self-assessment tool for the Council of Europe. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice, 6(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-022-00131-y

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Bullying at school and electronic bullying. Condition of education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved date from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/a10

Nery, M., Neto, C., Rosado, A., & Smith, P. K. (2019). Bullying in youth sport training: A nationwide exploratory and descriptive research in Portugal. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 16(4), 447–463.

Newman, J. A., Eccles, S., Rumbold, J. L., & Rhind, D. J. (2022). When it is no longer a bit of banter: Coaches’ perspectives of bullying in professional soccer. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(6), 1576–1593.

Nikolaou, D., & Crispin, L. M. (2022). Estimating the effects of sports and physical exercise on bullying. Contemporary Econonomic Policy, 40, 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12560

Ohlert, J., Vertommen, T., Rulofs, B., Rau, T., & Allroggen, M. (2020). Elite athletes’ experiences of interpersonal violence in organised sport in Germany, the Netherlands, and Belgium. European Journal of Sport Science, 21(4), 604–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1781266

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell.

Quinlan, E., Robertson, S., Miller, N., & Robertson-Boersma, D. (2014). Interventions to reduce bullying in health care organisations: A scoping review. Health Services Management Research, 27(1–2), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951484814547236

Rios, X., Ventur, C., & Mateu, P. (2022). “I gave up football and I had no intention of ever going back”: Retrospective experiences of victims of bullying in youth sport. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.819981

Ríos, X., & Ventura, C. (2022). Bullying in youth sport: Knowledge and prevention strategies of coaches. Apunts Educación Física y Deportes, 148, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.5672/apunts.2014-0983.es.(2022/2).148.07

Shannon, C. S. (2013). Bullying in recreation and sport settings: Exploring risk factors, prevention efforts, and intervention strategies. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 31(1). https://js.sagamorepub.com/index.php/jpra/article/view/2711

Smith, R. & Smoll, F. (2012). Sport psychology for youth coaches: Developing champions in sports and life. Washington, D.C.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Stefaniuk, L., & Bridel, W. (2018). Anti-bullying policies in Canadian sport: An absent presence. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 36(2), 160–176. https://doi.org/10.18666/JPRA-2018-V36-I2-8439

Steinfeldt, J. A., Vaughan, E. L., LaFollette, J. R., & Steinfeldt, M. C. (2012). Bullying among adolescent football players: Role of masculinity and moral atmosphere. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 13(4), 340–353.

Storr, R., Nicholas, L., Robinson, K., & Davies, C. (2022). ‘Game to play?’: Barriers and facilitators to sexuality and gender diverse young people’s participation in sport and physical activity. Sport, Education and Society, 27(5), 604–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2021.1897561

Vveinhardt J, Komskiene, D, & Romero, Z. (2017). Bullying and harassment prevention in youth basketball teams. Transformations in Business & Economics, 16(1), 232–251.

Vveinhardt, J., & Fominiene, V. B. (2019). Gender and age variables of bullying in organised sport: Is bullying “grown out of.” Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2020.154.03

Vveinhardt, J., & Fominiene, V. B. (2020). Prevalence of bullying and harassment in youth sport: The case of different types of sport and participant role. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2022.172.04

Vveinhardt, J., Fominiene, V. B., & Andriukaitiene, R. (2019). “Omerta” in organised sport: Bullying and harassment as determinants of threats of social sustainability at the individual level. Sustainability, 11(9), 2474.

Weuve, C., Pitney, W. A., Martin, M., & Mazerolle, S. M. (2014). Experiences with workplace bullying among athletic trainers in the collegiate setting. J Athl Train, 49(5), 696–705. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.16. Epub 2014 Aug 6. PMID: 25098660; PMCID: PMC4208875.

Yabe, Y., Hagiwara, Y., Sekiguchi, T., Momma, H., Tsuchiya, M., Kanazawa, K., Yoshida, S., Itoi, E., & Nagatomi, R. (2021). Characteristics of parents who feel a lack of communication with coaches of youth sports. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 253(3), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.253.191. Released on J-STAGE March 13, 2021, Online ISSN 1349-3329, Print ISSN 0040-8727.

Zapf, D., Escartín, J., Scheppa-Lahyani, M., Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., & Vartia, M. (2020). Empirical findings on prevalence and risk groups of bullying in the workplace. In S. Einarsen, H. Hoel, D. Zapf, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Workplace bullying: Development in theory, research and practice. CRC Press, Taylor and Francis: New York. ISBN: 9781138615991.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FH Kufstein Tirol - University of Applied Sciences. The research leading to these results received funding from the European Commission’s Erasmus+ programme Grant Agreement No. 2021-1-IE01-KA220-VET-000034749.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LK: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing and editing, visualisation. BTO: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing and editing, visualisation. SO: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—reviewing and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. LM: conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—reviewing and editing, visualisation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalina, L., O’Keeffe, B.T., O’Reilly, S. et al. Risk and Protective Factors for Bullying in Sport: A Scoping Review. Int Journal of Bullying Prevention (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00242-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-024-00242-9